Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Dynamic Equation Landau-Lifshitz- Gilbert (LLG)

3. Materials and Methods

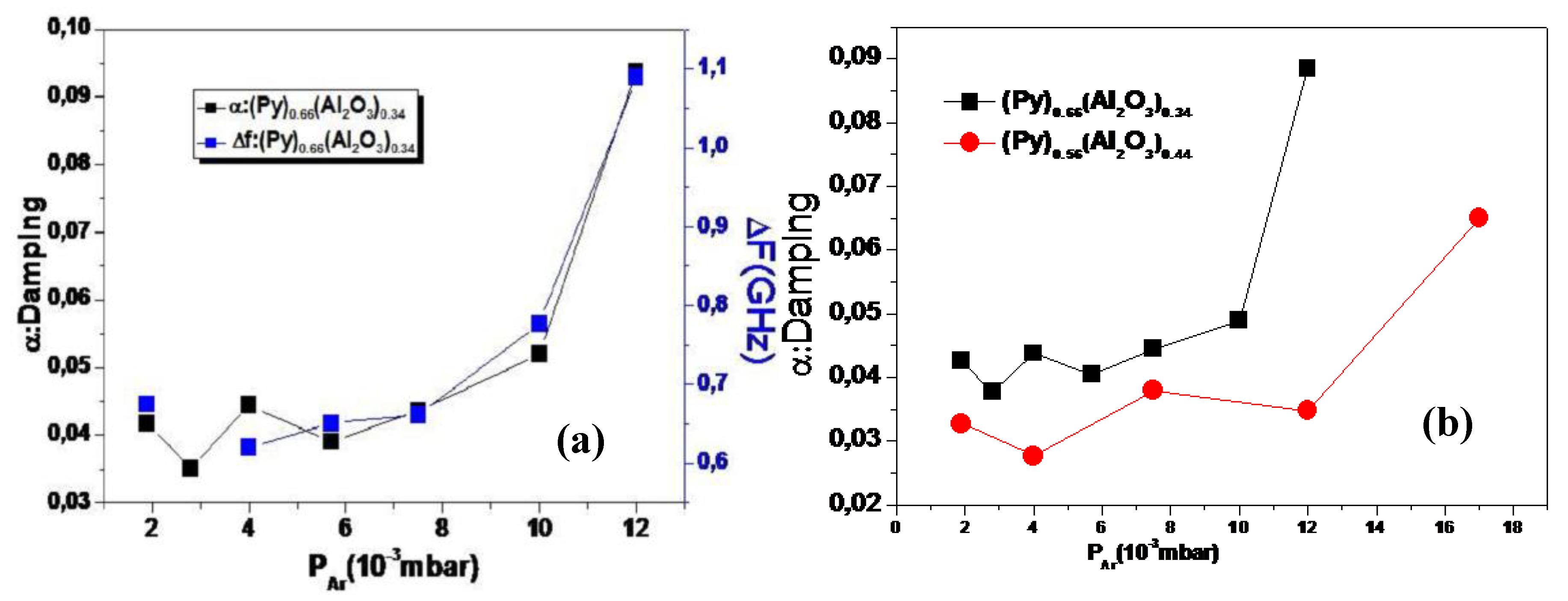

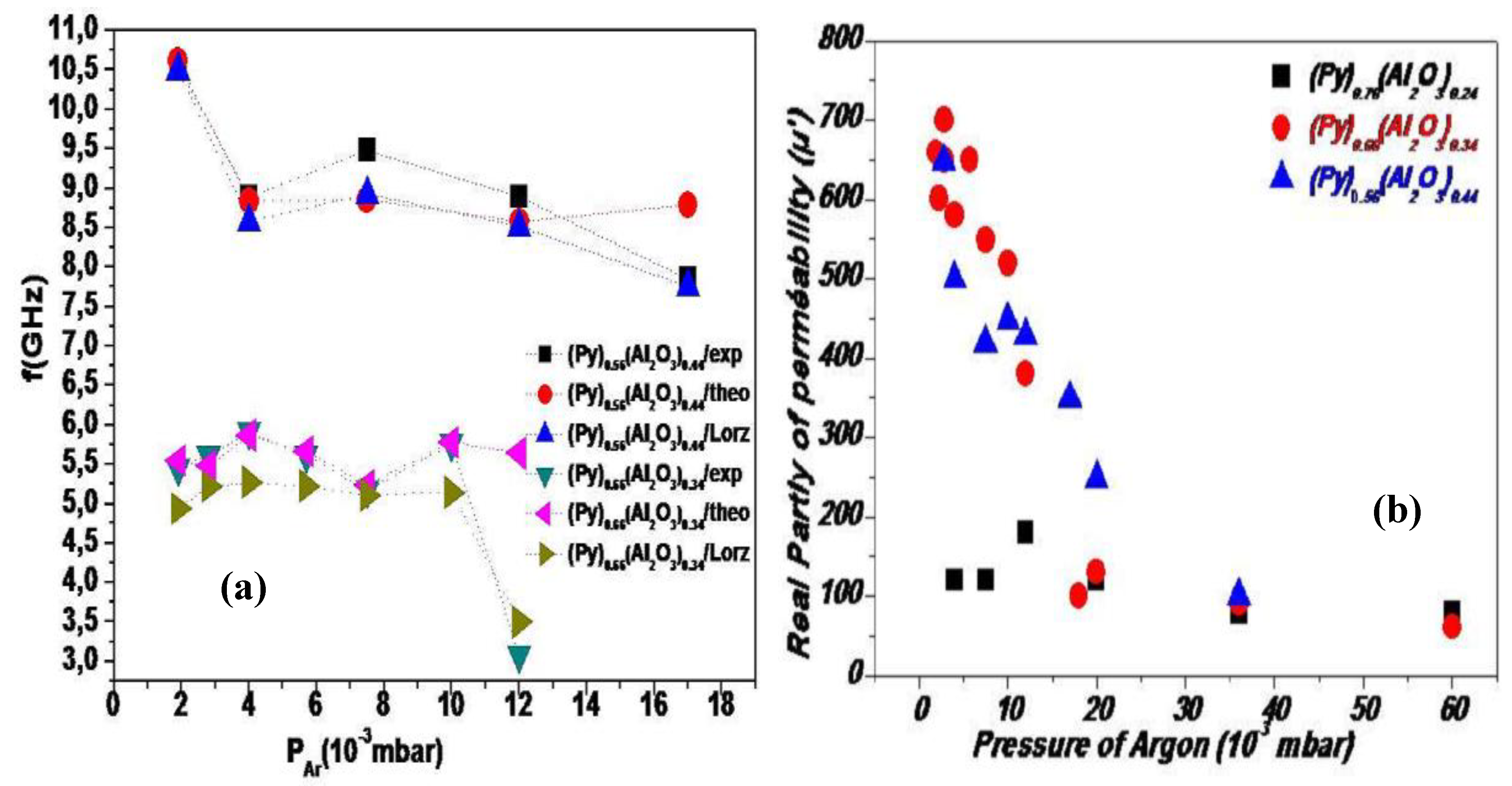

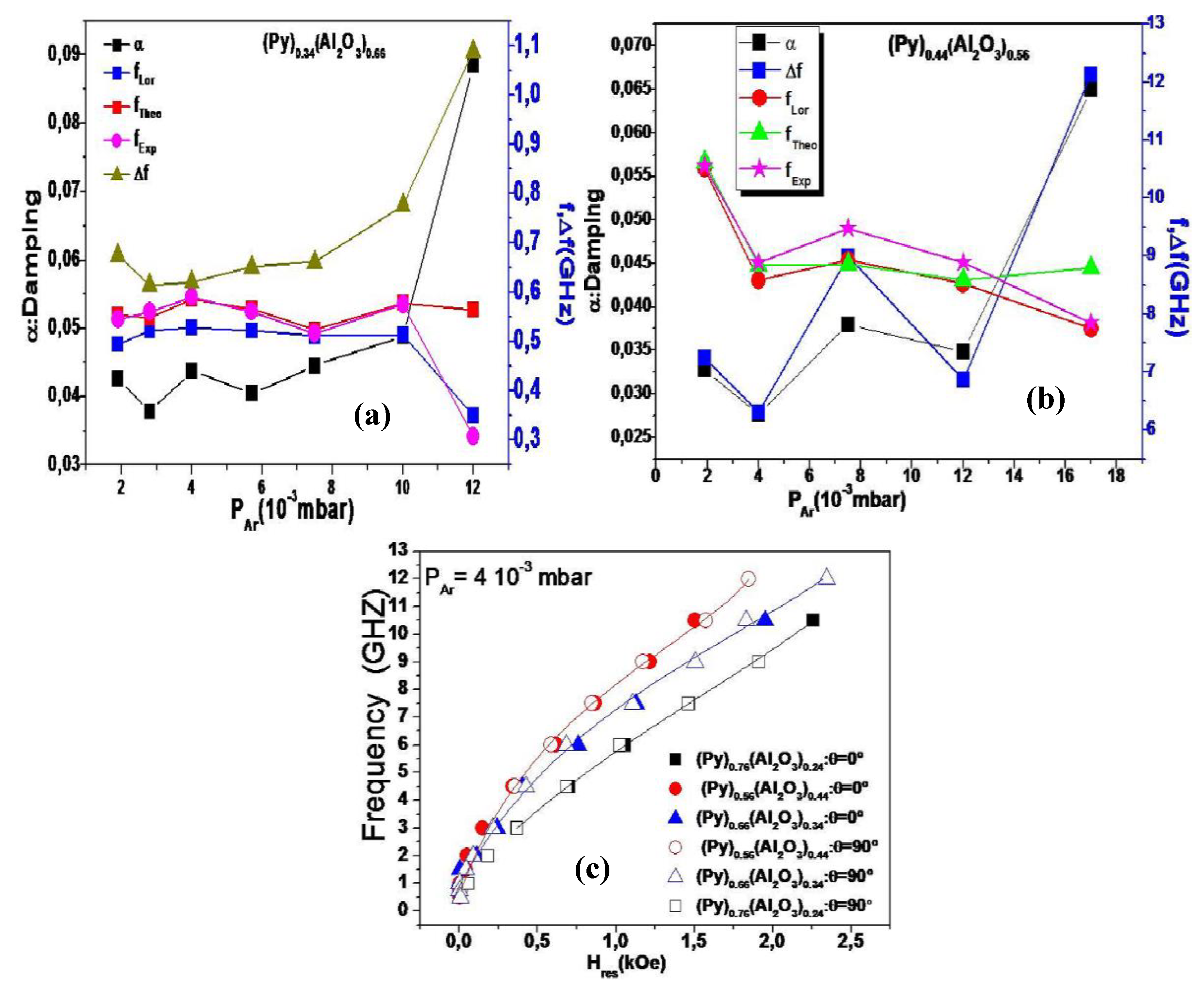

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Declaration of Competing Interest

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayakawa, Y.; Makino, A.; Fujimori, H.; Inoue, A. High Resistive Nanocrystalline Fe-M-O (M=Hf, Zr, Rare-Earth Metals) Soft Magnetic Films for High-Frequency Applications (Invited). J Appl Phys 1997, 81, 3747–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, S.; Masumoto, T. High Frequency Magnetic Properties and GMR Effect of Nano-Granular Magnetic Thin Films. Scr Mater 2001, 44, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsepelev, V.S.; Starodubtsev, Y.N. Nanocrystalline Soft Magnetic Iron-Based Materials from Liquid State to Ready Product. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Magnetic Properties, Microwave Characteristics, and Thermal Stability of the FeCoAlN Films. J Mater Eng Perform 2010, 19, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Ge, S.; Zhou, X.; Zuo, H. Grain Size Dependence of Coercivity in Magnetic Metal-Insulator Nanogranular Films with Uniaxial Magnetic Anisotropy. J Appl Phys 2010, 107, 073902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Hung, L.T.; Ong, C.K. FeCoHfN Thin Films Fabricated by Co-Sputtering with High Resonance Frequency. J Alloys Compd 2011, 509, 4010–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.H.; Chen, R.R.; Song, T.T.; Gao, Y.L.; Zhai, Q.J. Magnetic Characterization of Dual Phase FeZrB Soft Magnetic Alloy. J Magn Magn Mater 2011, 323, 3285–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Ge, S.; Zhang, B.; Zuo, H.; Zhou, X. Fabrication and Magnetism of Fe65Co35-MgF2 Granular Films for High Frequency Application. J Appl Phys 2008, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.; Lifshitz, E. On the Theory of the Dispersion of Magnetic Permeability in Ferromagnetic Bodies. Phys. Z. Sowjetunion 1935, 8, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Niekiel, F.; Fichtner, S.; Kirchhof, C.; Meyners, D.; Quandt, E.; Wagner, B.; Lofink, F. Frequency Tunable Resonant Magnetoelectric Sensors for the Detection of Weak Magnetic Field. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2020, 30, 075009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Gu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Gao, Y. Design and Optimization of a BAW Magnetic Sensor Based on Magnetoelectric Coupling. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahun, E.; Tanné, G.; Quéffélec, P.; Lefloc’h, M.; Adenot, A. -L.; Acher, O. Application of Ferromagnetic Composite in Different Planar Tunable Microwave Devices. Microw Opt Technol Lett 2001, 30, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Cui, S.; Bie, Z.; Song, K.; Zhu, C.; Matveevich, M.I. Modern Advances in Magnetic Materials of Wireless Power Transfer Systems: A Review and New Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maemura, M.; Kurpat, T.; Kimura, K.; Suzuki, T.; Hashimoto, T. Improvement of the Power Transfer Efficiency of a Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer System via Spatially Distributed Soft Magnetic Materials. In Proceedings of the 2022 Wireless Power Week (WPW); July 2022; pp. 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Acher, O.; Vermeulen, J.L.; Lucas, A.; Baclet, Ph.; Kazandjoglou, J.; Peuzin, J.C. Direct Measurement of Permeability up to 3 GHz of Co-Based Alloys under Tensile Stress. J Appl Phys 1993, 73, 6162–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, W.R. LXXIX. On the Electro-Chemical Polarity of Gases. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1852, 4, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledieu, M.; Schoenstein, F.; Le Gallou, J.-H.; Valls, O.; Queste, S.; Duverger, F.; Acher, O. Microwave Permeability Spectra of Ferromagnetic Thin Films over a Wide Range of Temperatures. J Appl Phys 2003, 93, 7202–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, T.L. Classics in Magnetics A Phenomenological Theory of Damping in Ferromagnetic Materials. IEEE Trans Magn 2004, 40, 3443–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahun, E.; Tanné, G.; Quéffélec, P.; Lefloc’h, M.; Adenot, A. -L.; Acher, O. Application of Ferromagnetic Composite in Different Planar Tunable Microwave Devices. Microw Opt Technol Lett 2001, 30, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanr, B.K.; Camley, R.E.; Celinski, Z. Exchange Bias of NiO/NiFe: Linewidth Broadening and Anomalous Spin-Wave Damping. J Appl Phys 2003, 93, 7723–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenato, D.; Pogossian, S.P.; Dekadjevi, D.T.; Youssef, J. Ben Study of Dynamic Properties and Magnetic Anisotropies of NiFe/MnPt in the Critical Thickness Range. J Phys D Appl Phys 2007, 40, 3306–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Yao, D.; Yamaguchi, M.; Yang, X.; Zuo, H.; Ishii, T.; Zhou, D.; Li, F. Microstructure and Magnetism of FeCo–SiO 2 Nano-Granular Films for High Frequency Application. J Phys D Appl Phys 2007, 40, 3660–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Tan, C.Y.; Liu, H.J.; Ong, C.K. Broadband Complex Permeability Characterization of Magnetic Thin Films Using Shorted Microstrip Transmission-Line Perturbation. Review of Scientific Instruments 2005, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Chai, G.; Ong, C.K. Temperature-Dependent Dynamic Magnetization of FeCoHf Thin Films Fabricated by Oblique Deposition. J Appl Phys 2012, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Anomalous Temperature Dependence of Magnetic Anisotropy in Gradient-Composition Sputterred Thin Films. Advanced Materials 2013, 25, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Observation of Magnetic Anisotropy Increment with Temperature in Composition-Graded FeCoZr Thin Films. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Chapon, P.; Acher, O.; Ong, C.K. Large Magneto-Elastic Anisotropy Enhancement with Temperature in Composition-Graded FeCoTa Thin Films. J Appl Phys 2013, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Gradient-Composition Sputtering: An Approach to Fabricate Magnetic Thin Films With Magnetic Anisotropy Increased With Temperature. IEEE Trans Magn 2014, 50, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipgen, L.; Fulara, H.; Raju, M.; Chaudhary, S. In-Plane Magnetic Anisotropy and Coercive Field Dependence upon Thickness of CoFeB. J Magn Magn Mater 2012, 324, 3118–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.-Y.; Yang, M.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, G.; Wang, S.-G.; Wang, K.-Y. Tuning the Magnetic Anisotropy of CoFeB Grown on Flexible Substrates. Chinese Physics B 2015, 24, 077501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, J.; Sort, J.; Hoffmann, A.; García-Martín, J.M.; Dieny, B.; Miranda, R.; Nogués, J. Origin of the Asymmetric Magnetization Reversal Behavior in Exchange-Biased Systems: Competing Anisotropies. Phys Rev Lett 2005, 95, 057204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Du, S.; Wang, F.; Adam, R.; Li, Q.; Ma, X.; Guo, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Influence of Surface Pinning in the Domain on the Magnetization Dynamics in Permalloy Striped Domain Films. J Alloys Compd 2021, 869, 159327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, Y.; Viala, B. NiMn, IrMn, and NiO Exchange Coupled CoFe Multilayers for Microwave Applications. IEEE Trans Magn 2006, 42, 3332–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xue, D.; Sui, W. Broadband Microwave Absorption in [NiFe/FeMn]n Exchange-Coupled Multilayer Films. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 2527–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Xu, F.; Ma, Y.; Ong, C.K. Permalloy–FeMn Exchange-Biased Multilayers Grown on Flexible Substrates for Microwave Applications. J Magn Magn Mater 2009, 321, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 36. Mallegol, S. 36. Mallegol, S. Caractérisation et Application de Matériaux Composites Nanostructures à La Réalisation de Dispositifs Hyperfréquences Non Réciproques, Université de Bretagne occidentale-Brest, 2003.

- Hung, L.T.; Phuoc, N.N.; Wang, X.-C.; Ong, C.K. Temperature Dependence Dynamical Permeability Characterization of Magnetic Thin Film Using Near-Field Microwave Microscopy. Review of Scientific Instruments 2011, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Xu, F.; Ong, C.K. Tuning Magnetization Dynamic Properties of Fe–SiO2 Multilayers by Oblique Deposition. J Appl Phys 2009, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantschler, J.O.; Alexander, C. Ripple Field Effect on High-Frequency Measurements of FeTiN Films. J Appl Phys 2003, 93, 6665–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olamit, J.; Liu, K. Rotational Hysteresis of the Exchange Anisotropy Direction in Co∕FeMn Thin Films. J Appl Phys 2007, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.Y.; Song, C.; Fan, B.; Zeng, F.; Pan, F. The Role of Rotatable Anisotropy in the Asymmetric Magnetization Reversal of Exchange Biased NiO/Ni Bilayers. J Appl Phys 2009, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Influence of Ferromagnetic Thickness on Dynamic Anisotropy in Exchange-Biased MnIr/FeCo Multilayered Thin Films. Physica B Condens Matter 2011, 406, 3514–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.; Mattheis, R.; Elefant, D. Dynamic Magnetic Anisotropy at the Onset of Exchange Bias: The $\mathrm{Ni}\mathrm{Fe}∕\mathrm{Ir}\mathrm{Mn}$ Ferromagnet/Antiferromagnet System. Phys Rev B 2004, 70, 94420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, R.D.; Lee, C.G.; Bonevich, J.E.; Chen, P.J.; Miller, W.; Egelhoff Jr., W. F. Strong Anisotropy in Thin Magnetic Films Deposited on Obliquely Sputtered Ta Underlayers. J Appl Phys 2000, 88, 3561–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, K.; Stiles, M.D.; Seib, J.; Steiauf, D.; Fähnle, M. Anisotropic Damping of the Magnetization Dynamics in Ni, Co, and Fe. Phys Rev B 2010, 81, 174414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.Z.; Zhu, J.-G.; Yu, W.; Bain, J.A. Micromagnetic Simulation of Effect of Stress-Induced Anisotropy in Soft Magnetic Thin Films. J Appl Phys 2004, 95, 6864–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeichuk, T.; Olekšáková, D.; Maciaszek, R.; Matysiak, W.; Kollár, P. Exploring the Impact of Different Milling Parameters of Fe/SiO2 Composites on Their Structural and Magnetic Properties. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, J. Ben; Vukadinovic, N.; Billet, D.; Labrune, M. Thickness-Dependent Magnetic Excitations in Permalloy Films with Nonuniform Magnetization. Phys Rev B 2004, 69, 174402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, Kh.; Lindner, J.; Barsukov, I.; Meckenstock, R.; Farle, M.; von Hörsten, U.; Wende, H.; Keune, W.; Rocker, J.; Kalarickal, S.S.; et al. Spin Dynamics in Ferromagnets: Gilbert Damping and Two-Magnon Scattering. Phys Rev B 2007, 76, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserkovnyak, Y.; Brataas, A.; Bauer, G.E.W. Enhanced Gilbert Damping in Thin Ferromagnetic Films. Phys Rev Lett 2002, 88, 117601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrits, Th.; Schneider, M.L.; Silva, T.J. Enhanced Ferromagnetic Damping in Permalloy∕Cu Bilayers. J Appl Phys 2006, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, R.; Schneider, M.L.; Silva, T.J.; Nibarger, J.P. Dependence of Magnetization Dynamics on Magnetostriction in NiFe Alloys. J Appl Phys 2005, 98, 123904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counil, G.; Kim, J.-V.; Devolder, T.; Chappert, C.; Shigeto, K.; Otani, Y. Spin Wave Contributions to the High-Frequency Magnetic Response of Thin Films Obtained with Inductive Methods. J Appl Phys 2004, 95, 5646–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K.; Wende, H.; Kuch, W.; Baberschke, K.; Nagy, K.; Jánossy, A. Two-Magnon Scattering and Viscous Gilbert Damping in Ultrathin Ferromagnets. Phys Rev B 2006, 73, 144424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanr, B.K.; Camley, R.E.; Celinski, Z. Extrinsic Contribution to Gilbert Damping in Sputtered NiFe Films by Ferromagnetic Resonance. J Magn Magn Mater 2005, 286, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.L.; Arias, R. The Damping of Spin Motions in Ultrathin Films: Is the Landau–Lifschitz–Gilbert Phenomenology Applicable? Physica B Condens Matter 2006, 384, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalarickal, S.S.; Krivosik, P.; Das, J.; Kim, K.S.; Patton, C.E. Microwave Damping in Polycrystalline Fe-Ti-N Films: Physical Mechanisms and Correlations with Composition and Structure. Phys Rev B 2008, 77, 054427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K.; Wende, H.; Kuch, W.; Baberschke, K.; Nagy, K.; Jánossy, A. Two-Magnon Scattering and Viscous Gilbert Damping in Ultrathin Ferromagnets. Phys Rev B 2006, 73, 144424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalarickal, S.S.; Krivosik, P.; Das, J.; Kim, K.S.; Patton, C.E. Microwave Damping in Polycrystalline Fe-Ti-N Films: Physical Mechanisms and Correlations with Composition and Structure. Phys Rev B 2008, 77, 054427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaping Zuo; Shihui Ge; Zhenkun Wang; Yuhua Xiao; Dongsheng Yao Soft Magnetic Properties and High-Frequency Characteristics in FeCoSi/Native-Oxide Multilayer Films. IEEE Trans Magn 2008, 44, 3111–3114. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jin, L.; Wen, T.; Liao, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, Z. Effects of Substrate Annealing on Uniaxial Magnetic Anisotropy and Ferromagnetic Resonance Frequency of Ni80Fe20 Films Deposited on Self-Organized Periodically Rippled Sapphire Substrates. Vacuum 2021, 186, 110047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, K.; Manivel Raja, M.; Sridhara Rao, D. V.; Kamat, S. V. Effect of Sputtering Pressure and Power on Composition, Surface Roughness, Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of as-Deposited Co2FeSi Thin Films. Thin Solid Films 2014, 558, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Zhang, W.L.; Xie, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.X.; Jiang, H.C. Effect of Sputtering Pressure on Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of Amorphous FeCoSiB Films. J Non Cryst Solids 2013, 365, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, T.; Wei, X.; Yan, B. Effect of the Sputtering Power on the Structure, Morphology and Magnetic Properties of Fe Films. Metals (Basel) 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.A.I.; Chmielus, M.; Han, S.; Baker, S.P. Effect of Sputter Pressure on Microstructure and Properties of β-Ta Thin Films. Acta Mater 2020, 183, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C. On the Theory of Ferromagnetic Resonance Absorption. Physical Review 1948, 73, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, R.D.; Twisselmann, D.J.; Kunz, A. Localized Ferromagnetic Resonance in Inhomogeneous Thin Films. Phys Rev Lett 2003, 90, 227601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei Zou; Yu, W. ; Bain, J.A. Influence of Stress and Texture on Soft Magnetic Properties of Thin Films. IEEE Trans Magn 2002, 38, 3501–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C. Interpretation of Anomalous Larmor Frequencies in Ferromagnetic Resonance Experiment. Physical Review 1947, 71, 270–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Lou, J.; Sun, N.X.; Vittoria, C.; Harris, V.G. Giant Magnetoelectric Coupling and E-Field Tunability in a Laminated Ni2MnGa/Lead-Magnesium-Niobate-Lead Titanate Multiferroic Heterostructure. Appl Phys Lett 2008, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Reed, D.; Pettiford, C.; Liu, M.; Han, P.; Dong, S.; Sun, N.X. Giant Microwave Tunability in FeGaB/Lead Magnesium Niobate-Lead Titanate Multiferroic Composites. Appl Phys Lett 2008, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xue, Q.; Duh, J.-G.; Du, H.; Xu, J.; Wan, Y.; Li, Q.; Lü, Y. Driving Ferromagnetic Resonance Frequency of FeCoB/PZN-PT Multiferroic Heterostructures to Ku-Band via Two-Step Climbing: Composition Gradient Sputtering and Magnetoelectric Coupling. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xue, Q.; Du, H.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Shi, Z.; Gao, X.; Liu, M.; Nan, T.; Hu, Z.; et al. Large E-Field Tunability of Magnetic Anisotropy and Ferromagnetic Resonance Frequency of Co-Sputtered Fe50Co50-B Film. J Appl Phys 2015, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Electric Field Modulation of Ultra-High Resonance Frequency in Obliquely Deposited [Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3]0.68-[PbTiO3]0.32(011)/FeCoZr Heterostructure for Reconfigurable Magnetoelectric Microwave Devices. Appl Phys Lett. [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, N.N.; Ong, C.K. Electric Field Control of Microwave Characteristics in Composition-Graded FeCoTa Film Grown onto [Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3]0.68-[PbTiO3]0.32(011) Crystal. Appl Phys Lett. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H. Magnetic Properties of Thin Ferromagnetic Films in Relation to Their Structure. Thin Solid Films 1979, 58, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, C.L.; Berkowitz, A.E.; Smith, D.J.; McCartney, M.R. Correlation of Coercivity and Microstructure of Thin CoFe Films. J Appl Phys 2000, 88, 2058–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-L.; Wang, L.-S.; Luo, Q.; Xu, L.; Yuan, B.-B.; Peng, D.-L. Preparation and High-Frequency Soft Magnetic Property of FeCo-Based Thin Films. Rare Metals 2016, 35, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xie, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, C.; Feng, H.; Cao, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Tuning the Ferromagnetic Resonance Frequency of Soft Magnetic Film by Patterned Permalloy Micro-Stripes with Stripe-Domain. J Magn Magn Mater 2018, 457, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ren, J.; Li, J.; Huang, Y. Measurement and Analysis of Magnetic Properties of Permalloy for Magnetic Shielding Devices under Different Temperature Environments. Materials 2023, 16, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).