Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

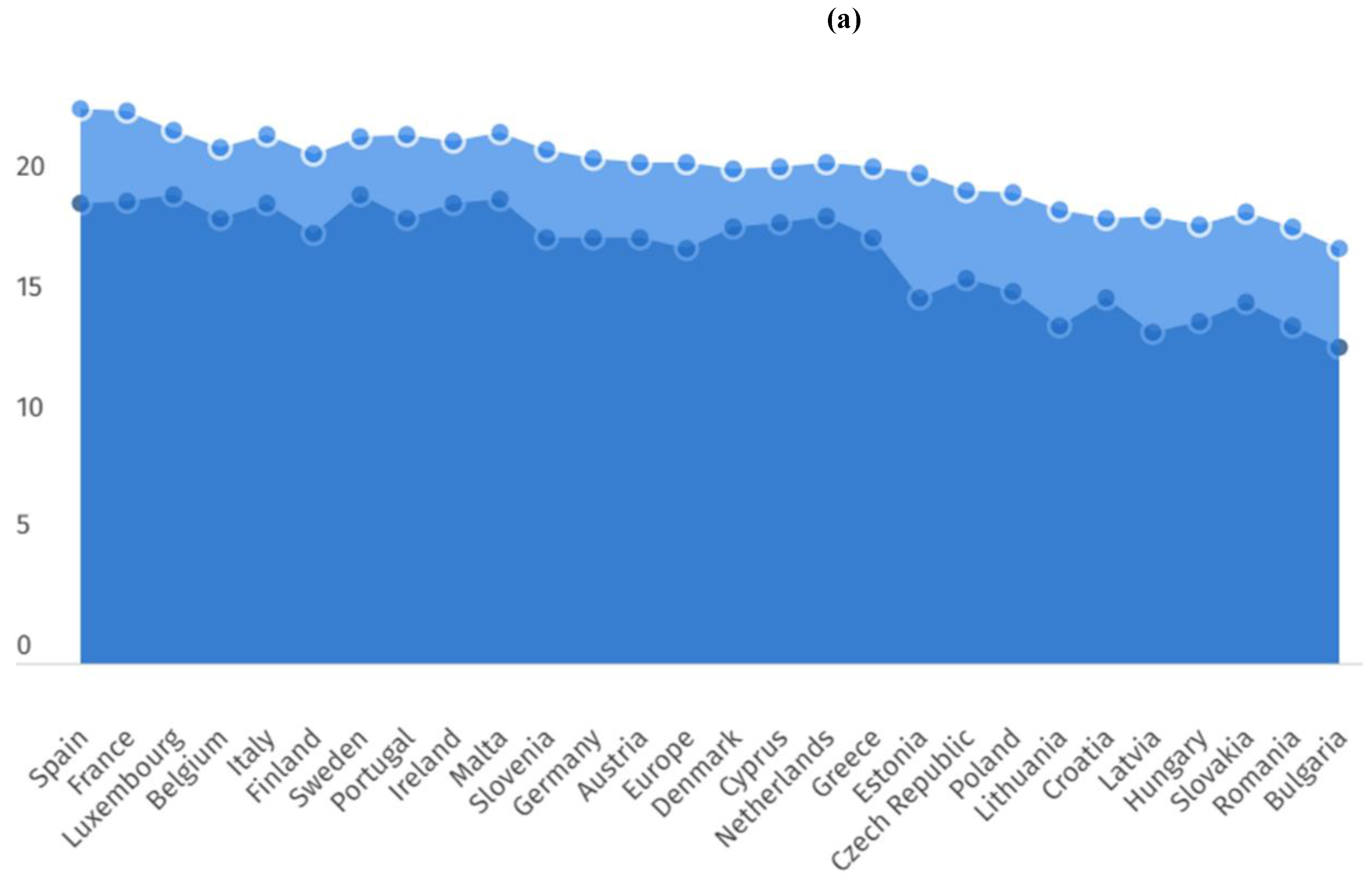

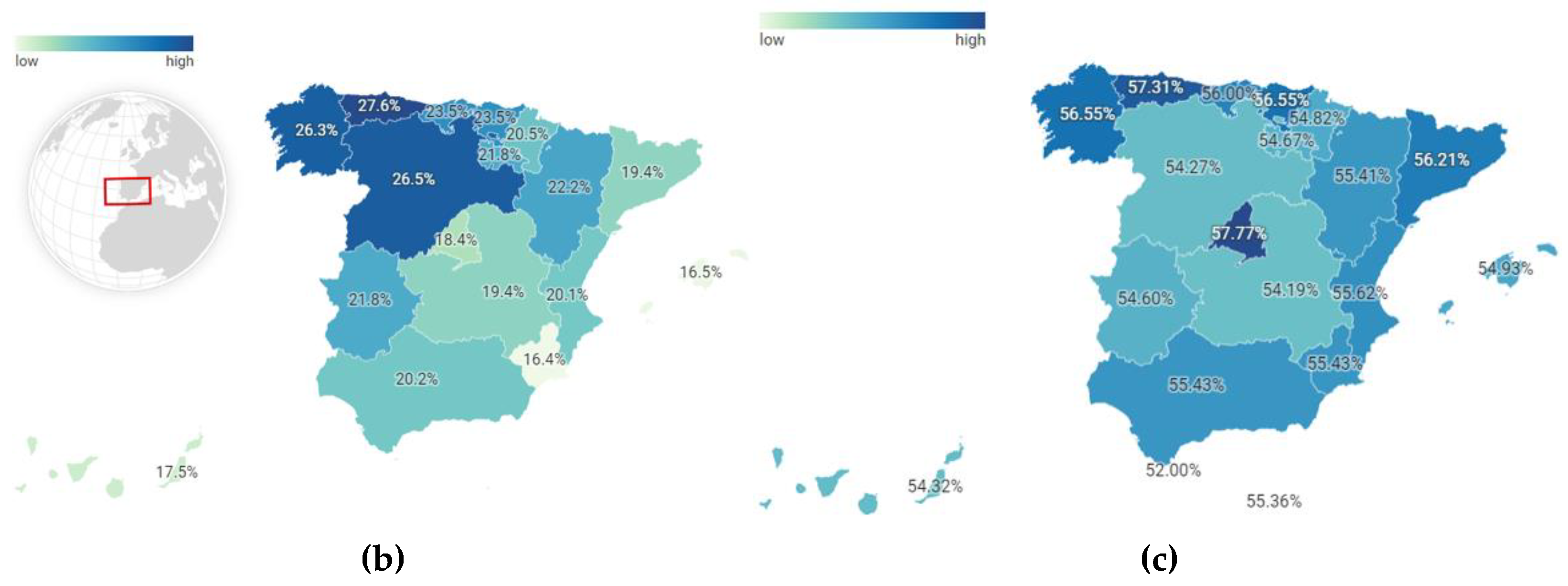

3. Health in Older Adults

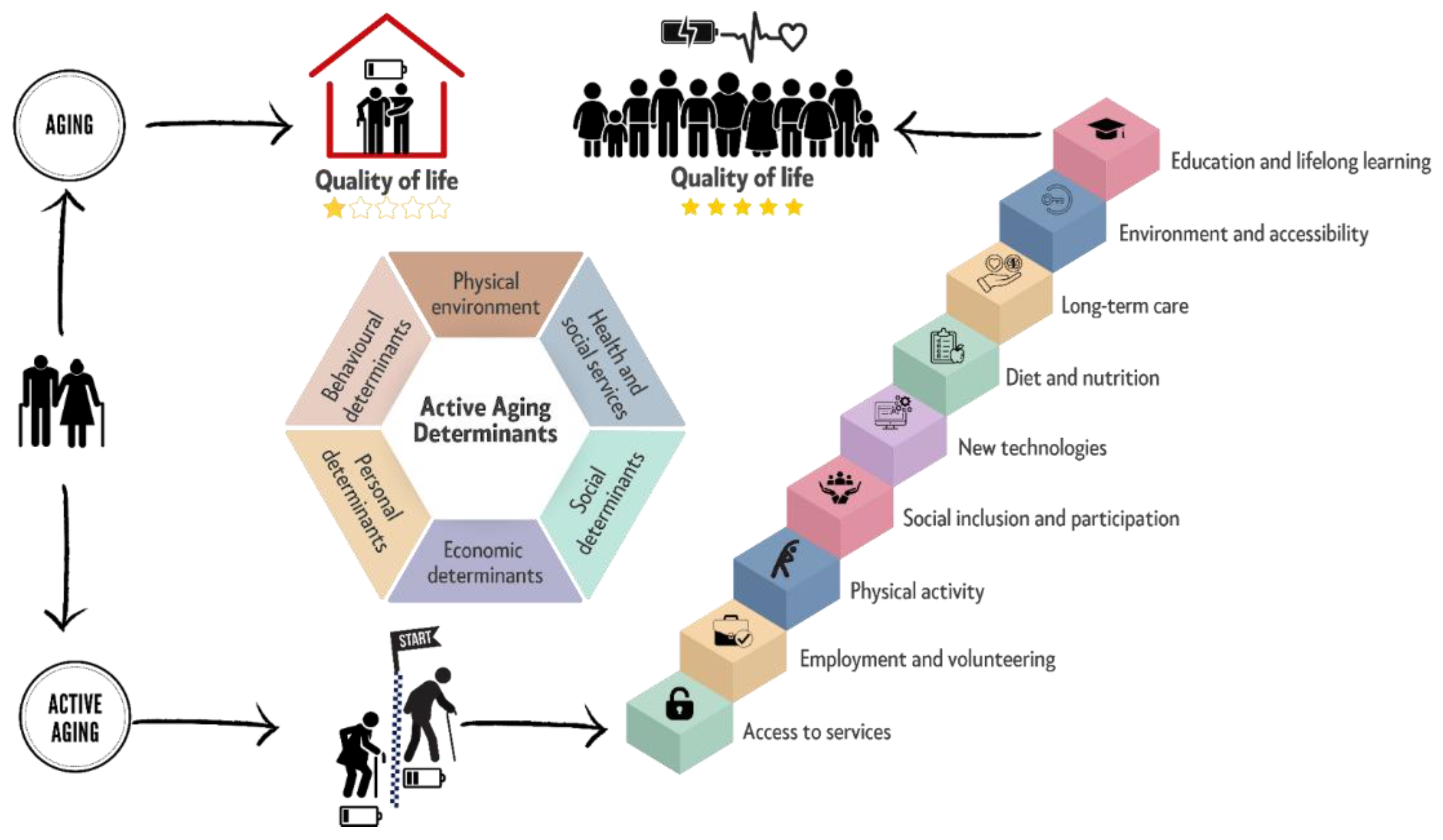

4. Healthy Ageing: Active and Social

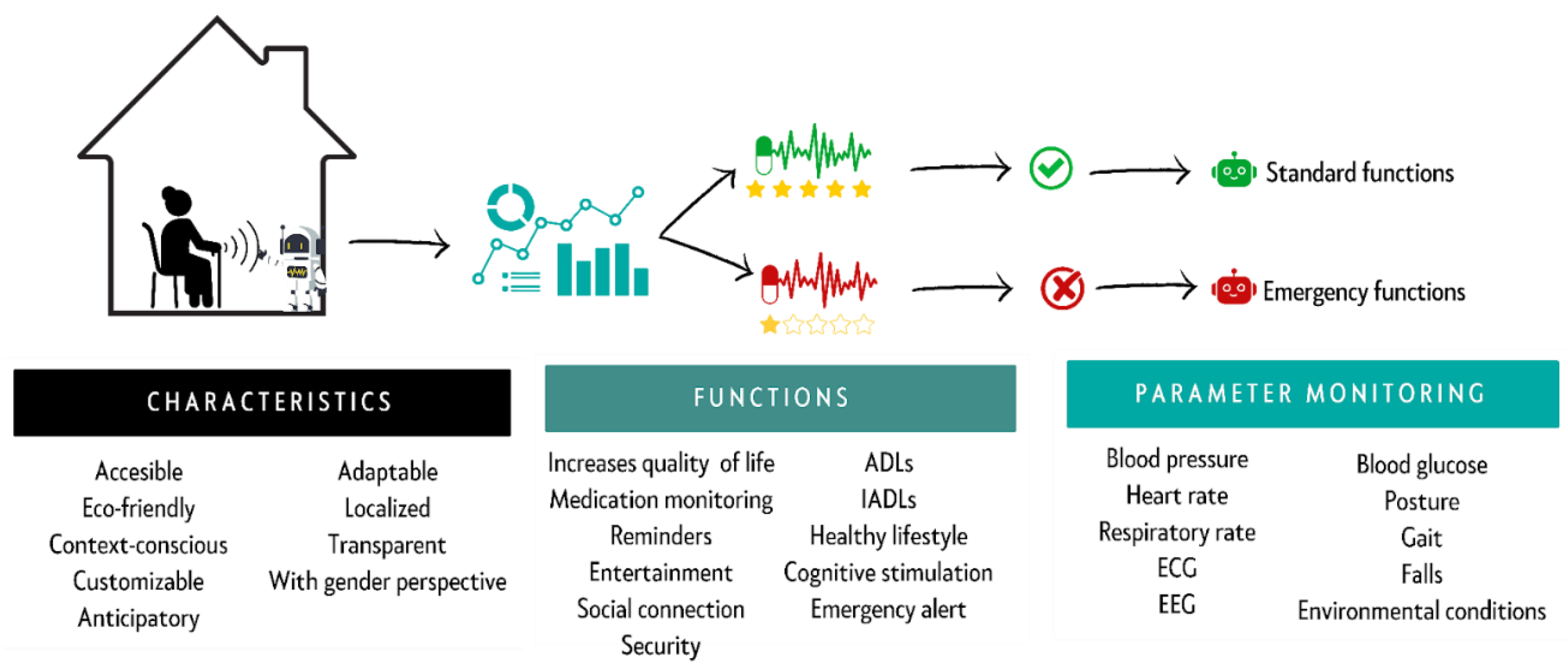

5. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): A New Opportunity to Assist Older Adults

6. Conclusions: ICTs as Allies of Well-Being

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Shaqi, R.; Mourshed, M.; Rezgui, Y. Progress in ambient assisted systems for independent living by the elderly. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzo, R.R.; Khanal, P.; Shrestha, S.; Mohan, D.; Myint, P.K.; Su, T.T. Determinants of active aging and quality of life among older adults: systematic review. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1193789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.P.; Latorre, J.M.; Gatz, M. Spain: Promoting the Welfare of Older Adults in the Context of Population Aging. Gerontol. 2014, 54, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.-Y.; Song, M.; Timakum, T.; Ryu, S.-R.; Lee, H. The landscape of smart aging: Topics, applications, and agenda. Data Knowl. Eng. 2018, 115, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, R. Preventing and managing chronic diseases. BMJ 2019, 364, l459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemoun Ph, Ader I, Planat-Benard V, Dray C, Fazilleau N, Monsarrat P, et al. A gerophysiology perspective on healthy ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2022 Jan 1;73:101537.

- Kotwal, A.A.; Cenzer, I.S.; Waite, L.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Perissinotto, C.M.; Boscardin, W.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Dale, W.; Smith, A.K. The epidemiology of social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the last years of life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 3081–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, I.C. The Elderly in a Period of Transition: Health, Personality, and Social Aspects of Adaptation. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2007, 1114, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronikowski, A.M.; Meisel, R.P.; Biga, P.R.; Walters, J.R.; Mank, J.E.; Larschan, E.; Wilkinson, G.S.; Valenzuela, N.; Conard, A.M.; de Magalhães, J.P.; et al. Sex-specific aging in animals: Perspective and future directions. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, Z.; Ahmad, W.I.W.; Hamjah, S.H.; Astina, I.K. The Impact of Population Ageing: A Review. Iran. J. Public Heal. 2021, 50, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

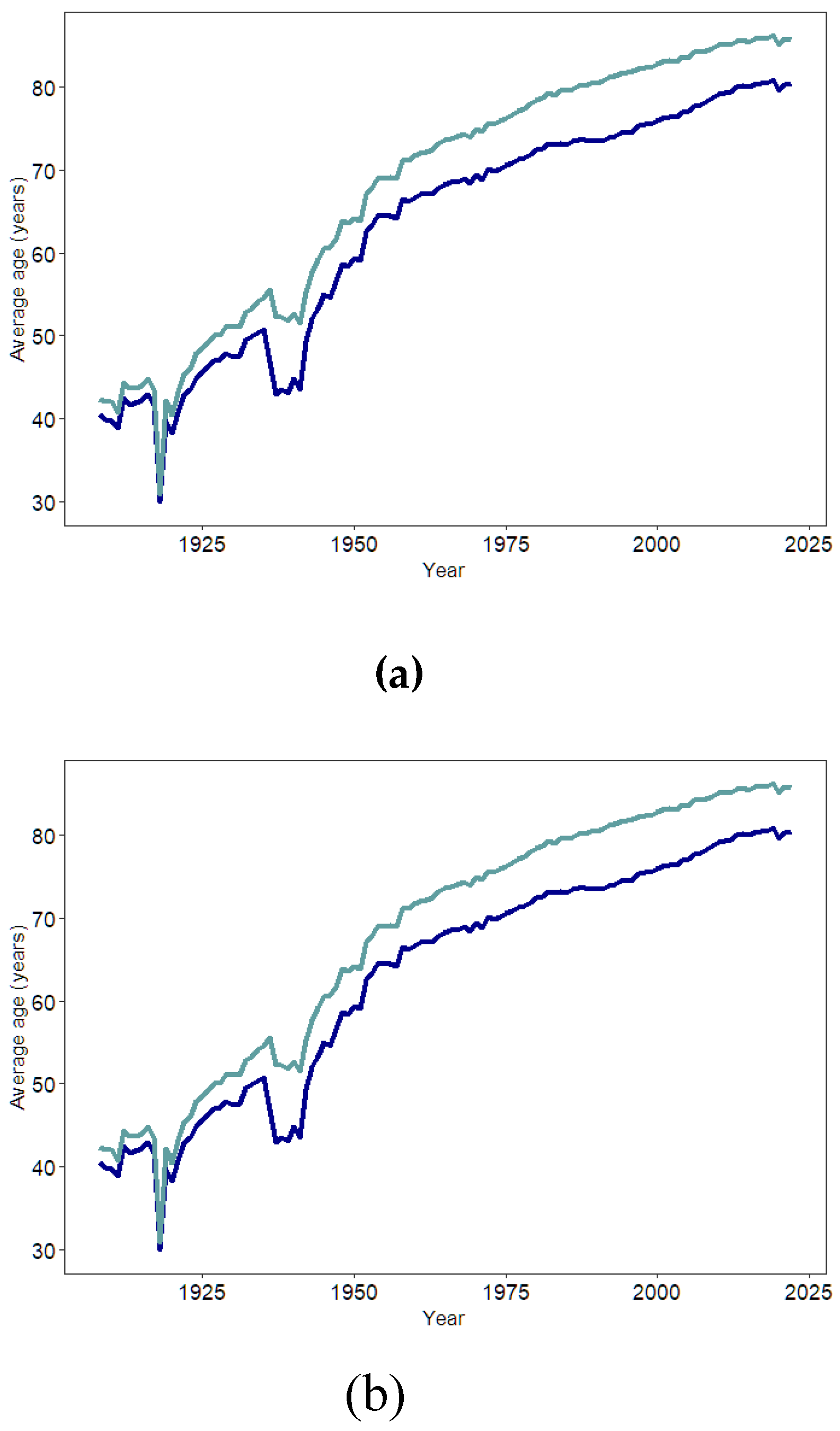

- Atance, D.; Claramunt, M.M.; Varea, X.; Aburto, J.M. Convergence and divergence in mortality: A global study from 1990 to 2030. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0295842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World report on ageing and health [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Evolución de la esperanza de vida al nacimiento. Brecha de género. España [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?blobcol=urldata&blobheader=Unknown+format&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3B+filename%3DD1T1.xlsx&blobkey=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobwhere=61%2F25%2FD1T1%2C0.xlsx&ssbinary=true.

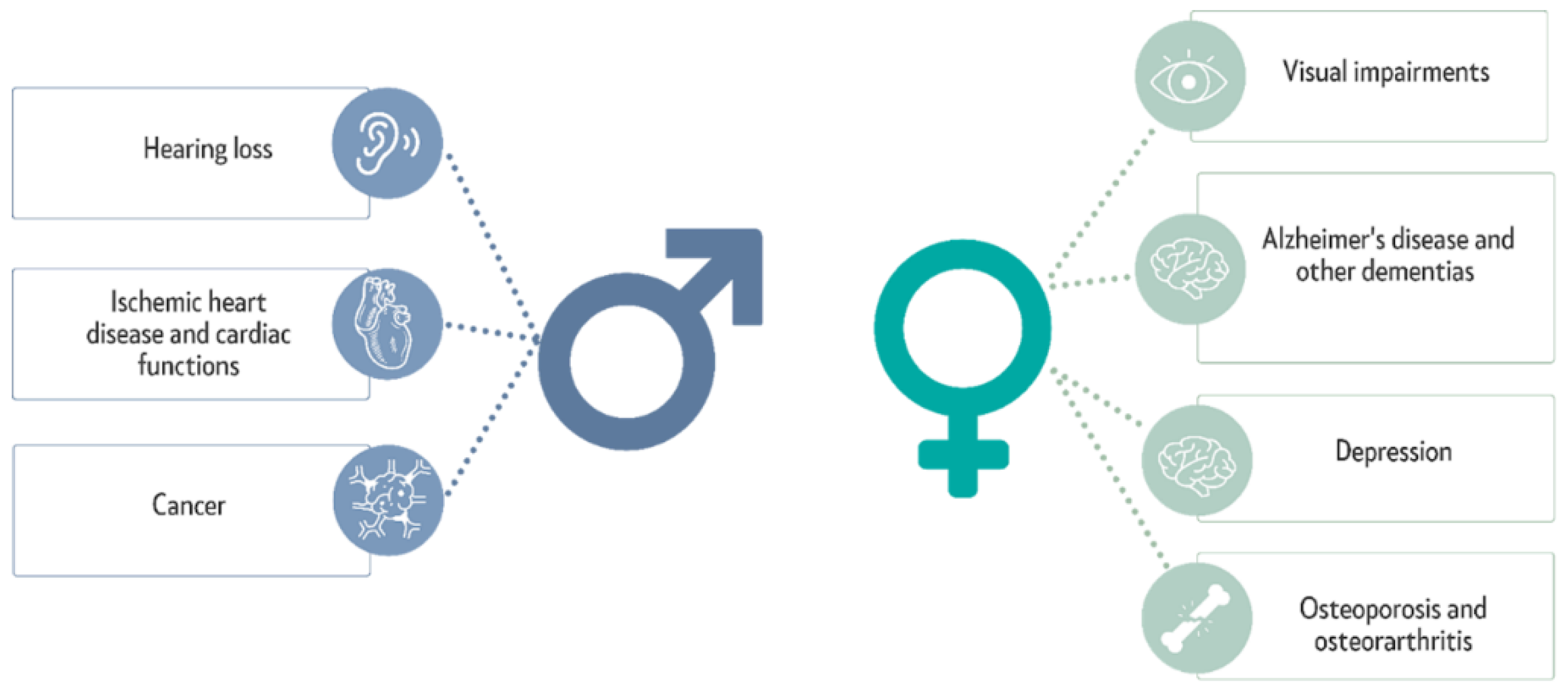

- Pérez Díaz J, Ramiro Fariñas D, Aceituno Nieto P, Escudero Martínez J, Bueno López C, Castillo Belmonte AB, et al. Un perfil de las personas mayores en España, 2023 Indicadores estadísticos básicos. [Internet]. Madrid; 2023. Available from: https://envejecimientoenred.csic.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/enred-indicadoresbasicos2023.pdf.

- Sunzi, K.; Li, Y.; Lei, C.; Zhou, X. How do the older adults in nursing homes live with dignity? A protocol for a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägg, S.; Jylhävä, J.; Biostatistics; Institutet, K.; Sweden Sex differences in biological aging with a focus on human studies. eLife 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Damaske S, Frech A. Women’s Work Pathways Across the Life Course. Demography. 2016 Apr;53(2):365–91.

- Esperanza de vida a los 65 años en la UE. Brecha de género. Serie 2021-2022. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t00/mujeres_hombres/tablas_1/l0/&file=d01008.px.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Proporción de personas mayores de cierta edad por comunidad autónoma [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t00/mujeres_hombres/tablas_2/&file=d2g5.px.

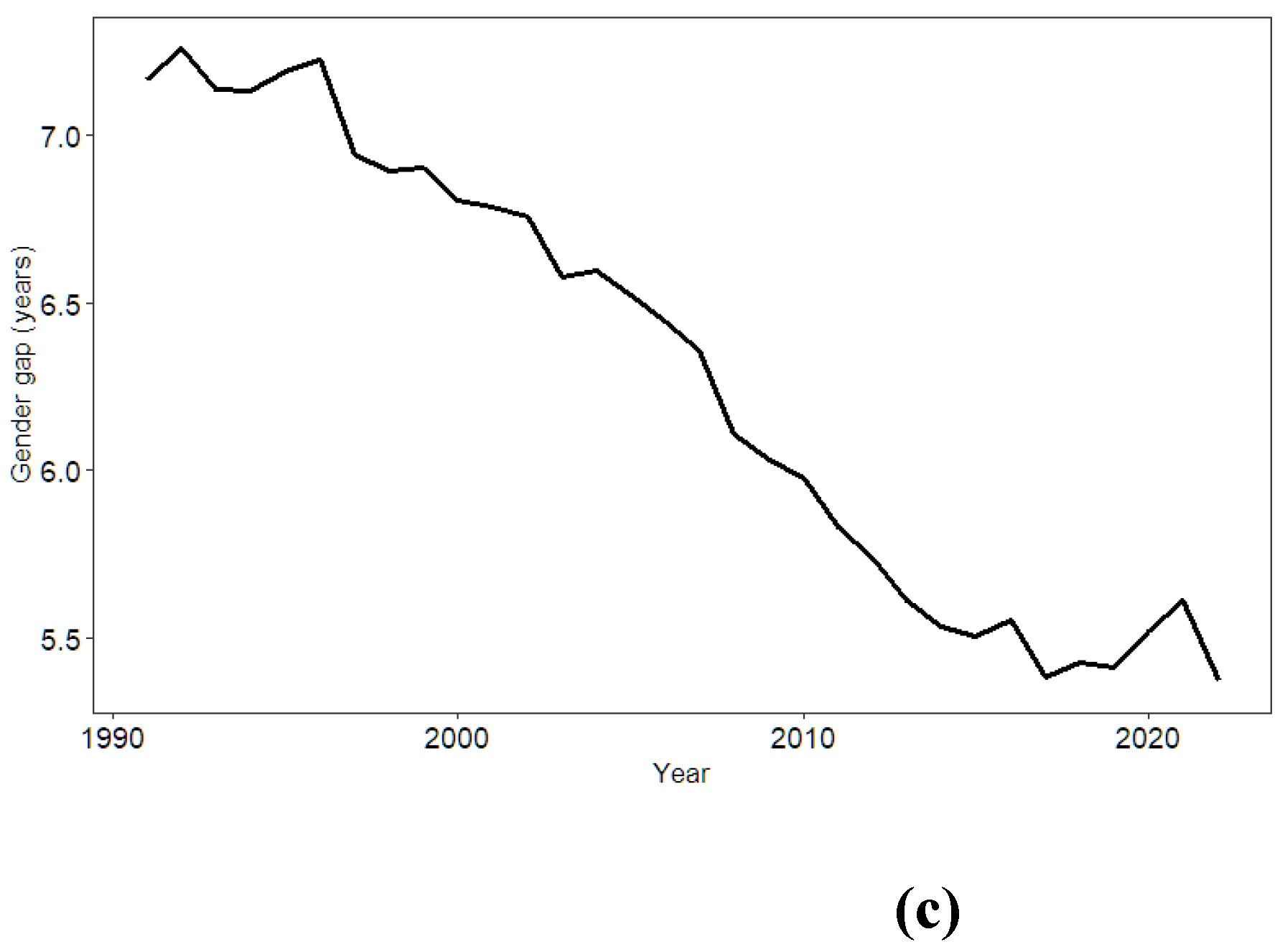

- Sampathkumar, N.K.; Bravo, J.I.; Chen, Y.; Danthi, P.S.; Donahue, E.K.; Lai, R.W.; Lu, R.; Randall, L.T.; Vinson, N.; Benayoun, B.A. Widespread sex dimorphism in aging and age-related diseases. Hum. Genet. 2019, 139, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasienska, G. Costs of reproduction and ageing in the human female. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa NF da S, Lima MG, Cesar CLG, Barros MB de A. Active aging: prevalence and gender and age differences in a population-based study. Cad Saúde Pública. 2018 Nov 23;34:e00173317.

- Langmann, E.; Weßel, M. Leaving no one behind: successful ageing at the intersection of ageism and ableism. Philos. Ethic- Humanit. Med. 2023, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in Older Persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 23;172(14):1078–83.

- Byhoff, E.; Tripodis, Y.; Freund, K.M.; Garg, A. Gender Differences in Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health in Aging Adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 2310–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raparelli, V.; Norris, C.M.; Bender, U.; Herrero, M.T.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Kublickiene, K.; El Emam, K.; Pilote, L. Identification and inclusion of gender factors in retrospective cohort studies: the GOING-FWD framework. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2021, 6, e005413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadiri, C.P.; Gisinger, T.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Kublickiene, K.; Herrero, M.T.; Norris, C.M.; Raparelli, V.; Pilote, L. Additional file 1 of Determinants of perceived health and unmet healthcare needs in universal healthcare systems with high gender equality. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active ageing: A policy framework. Madrid: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Instituto de la Mujer y Para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. Mujeres Mayores [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/AreaSalud/Publicaciones/docs/GuiasSalud/Salud_IX.pdf Reference class.

- Ryan, C.P.; Lee, N.R.; Carba, D.B.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Lin, D.T.S.; Atashzay, P.; Belsky, D.W.; Kobor, M.S.; Kuzawa, C.W. Pregnancy is linked to faster epigenetic aging in young women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor L. Women live longer than men but have more illness throughout life, global study finds. BMJ. 2024 May 2;385:q999.

- Melzer, D.; Pilling, L.C.; Ferrucci, L. The genetics of human ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 21, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.M.; Boelaert, K. The Endocrinology of Ageing: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2014, 61, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönninghoff, A.; Fuchs, K.; Wu, J.; Albert, J.; Mayer, S. The Effect of a Future-Self Avatar Mobile Health Intervention (FutureMe) on Physical Activity and Food Purchases: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e32487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Sawad, A.; Narayan, B.; Alnefaie, A.; Maqbool, A.; Mckie, I.; Smith, J.; Yuksel, B.; Puthal, D.; Prasad, M.; Kocaballi, A.B. A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions. Sensors 2022, 22, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Vellani, S.; Yeung, L.; Chishtie, J.; Commisso, E.; Ploeg, J.; Andrew, M.K.; Ayala, A.P.; Gray, M.; Morgan, D.; et al. Identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.P.; O’connor, M.; Vafaei, A. Women suffer but men die: survey data exploring whether this self-reported health paradox is real or an artefact of gender stereotypes. BMC Public Heal. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmel, S. Health and Well-Being in Late Life: Gender Differences Worldwide. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short SE, Yang YC, Jenkins TM. Sex, Gender, Genetics, and Health. Am J Public Health. 2013 Oct;103(Suppl 1):S93–101.

- Nair, S.; Sawant, N.; Thippeswamy, H.; Desai, G. Gender Issues in the Care of Elderly: A Narrative Review. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, S48–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Teh, D.B.L.; Kennedy, B.K.; Huang, Z. Unraveling female reproductive senescence to enhance healthy longevity. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encuesta Europea de Salud en España [Internet]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística; 2020. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/EncuestaEuropea/EESE2020_inf_evol_princip_result2.pdf.

- Balistreri, C.R. New frontiers in ageing and longevity: Sex and gender medicine. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 214, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergaard, D.; Moseley, P.; Sørup, F.K.H.; Baldi, P.; Brunak, S. Population-wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun TY, Hardin J, Nieva HR, Natarajan K, Cheng R fong, Ryan P, et al. Large-scale characterization of gender differences in diagnosis prevalence and time to diagnosis. medRxiv. 2023 Oct 16;2023.10.12.23296976.

- Gogovor, A.; Zomahoun, H.T.V.; Ekanmian, G.; Adisso, .L.; Tardif, A.D.; Khadhraoui, L.; Rheault, N.; Moher, D.; Légaré, F. Sex and gender considerations in reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 62. [CrossRef]

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998 May;28(3):551–8.

- Baraković, S.; Husić, J.B.; van Hoof, J.; Krejcar, O.; Maresova, P.; Akhtar, Z.; Melero, F.J. Quality of Life Framework for Personalised Ageing: A Systematic Review of ICT Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-L.; Liu, H.-T. Effect of a multi-disciplinary active aging intervention among community elders. Medicine 2021, 100, e28314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmell, A.L.; Jeste, D.; Depp, C. Strategies for Successful Aging: A Research Update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 476–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barha, C.K.; Falck, R.S.; Skou, S.T.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Personalising exercise recommendations for healthy cognition and mobility in aging: time to address sex and gender (Part 1). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 55, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne S, Doyal L. Older women, work and health.

- Akhter-Khan, S.C. Providing Care Is Self-Care: Towards Valuing Older People’s Care Provision in Global Economies. Gerontol. 2020, 61, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Shankar, A.; Demakakos, P.; Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qianqian D, Ni G, Qin H, Guicheng C, Jingyue X, L L, et al. Why do older adults living alone in cities cease seeking assistance? A qualitative study in China. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2022 Jun 29 [cited 2024 Jun 19];22(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35768784/.

- Newmyer, L.; Verdery, A.M.; Wang, H.; Margolis, R. Population Aging, Demographic Metabolism, and the Rising Tide of Late Middle Age to Older Adult Loneliness Around the World. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 829–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.D.; Uchino, B.N.; Wethington, E. Loneliness and Health in Older Adults: A Mini-Review and Synthesis. Gerontology 2015, 62, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, B.; Khalili-Mahani, N.; Murphy, C.; Sawchuk, K.; Phillips, N.; Li, K.Z.H.; Hebblethwaite, S. The association between information and communication technologies, loneliness and social connectedness: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi S, Spann A, Borilovic J, de Witte L, Hawley M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: a scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. 2019 Jul 22;19(1):195.

- Shah, S.G.S.; Nogueras, D.; van Woerden, H.C.; Kiparoglou, V. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Digital Technology Interventions to Reduce Loneliness in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

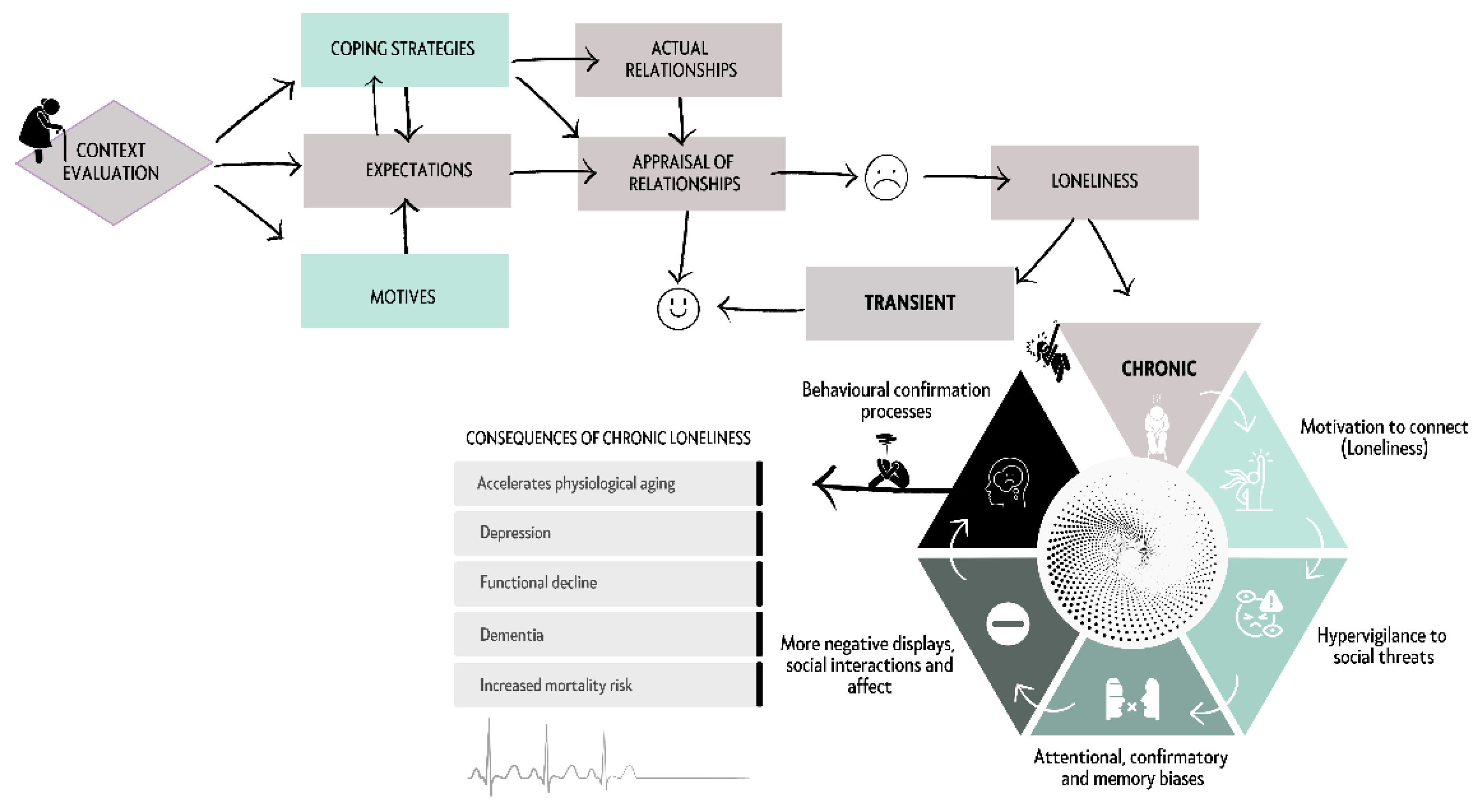

- Akhter-Khan, S.C.; Prina, M.; Wong, G.H.-Y.; Mayston, R.; Li, L. Understanding and Addressing Older Adults’ Loneliness: The Social Relationship Expectations Framework. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 18, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, D.; Kholghi, M.; Sandhu, M.; Lu, W.; Packer, K.; Higgins, L.; Silvera-Tawil, D. Sensor-Based Assessment of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: A Survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.H. Gender Differences in Correlates of Loneliness among Community-Dwelling Older Koreans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquet, C.; Whitehead, J.; Shah, R.; Adams, A.M.; Dooley, D.; Spreng, R.N.; Aunio, A.-L.; Dubé, L. Social Prescription Interventions Addressing Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Meta-Review Integrating On-the-Ground Resources. J. Med Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson SG, Dundis SP. Understanding and motivating health care employees: integrating Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, training and technology. J Nurs Manag. 2003;11(5):315–20.

- Chan, D.Y.L.; Lee, S.W.H.; Teh, P.-L. Factors influencing technology use among low-income older adults: A systematic review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; Villalba-Mora, E.; Pérez-Rodríguez, R.; Ferre, X.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Unobtrusive Sensors for the Assessment of Older Adult’s Frailty: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brath, H.; Kalia, S.; Li, J.M.; Lawson, A.; Rochon, P.A. Designing nursing homes with older women in mind. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 3657–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-W.; Choi, Y.-L.; Jeong, S.-H.; Han, J. A Care Robot with Ethical Sensing System for Older Adults at Home. Sensors 2022, 22, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, J.; Moreira, J.; Santos, R.; Kontio, E.; Pinheiro, A.R.; Sousa, A.S.P. Health-Related Telemonitoring Parameters/Signals of Older Adults: An Umbrella Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavasour, G.; Giggins, O.M.; Doyle, J.; Kelly, D. How wearable sensors have been utilised to evaluate frailty in older adults: a systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabilitation 2021, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, S.; Sufian, A.; Barman, D.; Dutta, P.; Dong, M.; Leo, M. In-Home Older Adults’ Activity Pattern Monitoring Using Depth Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surianarayanan, C.; Lawrence, J.J.; Chelliah, P.R.; Prakash, E.; Hewage, C. Convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience towards the Diagnosis of Neurological Disorders—A Scoping Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowland R, Necka EA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and Social Internet Use: Pathways to Reconnection in a Digital World? Perspect Psychol Sci J Assoc Psychol Sci. 2018 Jan;13(1):70–87.

- Martinengo, L.; Jabir, A.I.; Goh, W.W.T.; Lo, N.Y.W.; Ho, M.-H.R.; Kowatsch, T.; Atun, R.; Michie, S.; Car, L.T. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review of Their Behavior Change Techniques and Underpinning Theory. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, G.; Zaccaria, D.; Rolandi, E.; Guaita, A. The Effect of Information and Communication Technology and Social Networking Site Use on Older People’s Well-Being in Relation to Loneliness: Review of Experimental Studies. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, C. Active subjects of passive monitoring: responses to a passive monitoring system in low-income independent living. Ageing Soc. 2015, 37, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coco, K.; Kangasniemi, M.; Rantanen, T. Care Personnel's Attitudes and Fears Toward Care Robots in Elderly Care: A Comparison of Data from the Care Personnel in Finland and Japan. J. Nurs. Sch. 2018, 50, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, N.L.A.; Leow, Y.; Klainin-Yobas, P.; Itoh, S.; Wu, V.X. The effectiveness of a therapeutic robot, ‘Paro’, on behavioural and psychological symptoms, medication use, total sleep time and sociability in older adults with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 145, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh JH, Yi YJ, Shin CJ, Park C, Kang S, Kim J, et al. [Effects of Silver-Care-Robot Program on Cognitive Function, Depression, and Activities of Daily Living for Institutionalized Elderly People]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2015 Jun;45(3):388–96.

- Pino, M.; Boulay, M.; Jouen, F.; Rigaud, A.-S. “Are we ready for robots that care for us?” Attitudes and opinions of older adults toward socially assistive robots. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Patten R, Keller AV, Maye JE, Jeste DV, Depp C, Riek LD, et al. Home-Based Cognitively Assistive Robots: Maximizing Cognitive Functioning and Maintaining Independence in Older Adults Without Dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2020 Jul 13;15:1129–39.

- Cirillo, D.; Catuara-Solarz, S.; Morey, C.; Guney, E.; Subirats, L.; Mellino, S.; Gigante, A.; Valencia, A.; Rementeria, M.J.; Chadha, A.S.; et al. Sex and gender differences and biases in artificial intelligence for biomedicine and healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher A, Nåden D, Karterud D. Robots in elder care: Some ethical questions. Nurs Ethics. 2016 Jun;23(4):369–71.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).