1. Introduction

Scarlet fever is a popular widespread infection commonly referred as sandpaper rash and is caused by

Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria. This bacterium is further categorized in group A which is known as Group A Strep (GAS), a gram-positive coccus [

1]. Scarlet fever is a rash that occurs in school-age children between the age of 5 to 15 years old as it is easily transmitted in the classrooms and nurseries [

2]. In adults and other aged children also, there are chances of risk of infection about 5 to 15% [

3]. This fever along with rash becomes more dangerous when it caused by GAS agent showing severe complications and therefore immediate prevention is needed [

4]. It is treated by antibiotics such as peniciliin but some people are allergic to this so cephalosporin, clindamycin, or erythromycin are given to those [

5]. Scarlet fever can cause even death among children if it is not treated at an early stage. Antibiotics are currently the primary treatment option for S. pyogenes infections, even in non-severe cases. However, the reliance on antibiotics underscores the need for safer alternative treatments to mitigate potential adverse effects [

6]. S. pyogenes, a gram-positive coccus, possesses a genome of 1.88 Mbp with a GC content of approximately 38.6% [

7]. This genome includes prophage-like elements or prophages that play a crucial role in the infection mechanism, contributing to factors such as adhesin, superantigen genes, and exotoxins. While S. pyogenes can infect pets, humans are the primary source of transmission, leading to its classification as a human-adapted pathogen [

8].

The virulence proteins that play a critical role in the development of scarlet fever include M protein, C5a peptidase protein, and Streptolysin O (SLO) [

9]. Among these, the M protein stands out as a key virulence factor of S. pyogenes, first identified by Rebecca Lancefield in 1928 [

10]. The M protein initiates the attachment of bacteria to mucosal cells and immunoglobulins therefore enhancing its resistance to phagocytosis [

11]. It is a fibrillar molecule characterized by an alpha-helix coil structure. The N and C terminal regions are arranged such that the C-terminal end is anchored to the cell wall, while the N-terminal end extends away from the cell. C5a peptidase is also called as ScpA, which is a peptidase cell-bound to the cell wall by sortase A which helps in the activation of complement factor C5a that stimulate polymorphonuclear leukocytes at the infection site [

12]. The C5a peptidase protein significantly enhances the pathogen's virulence by inactivating C5a, a crucial component of the host's immune system responsible for recruiting phagocytic cells to the infection site. By neutralizing this immune response, S. pyogenes can evade detection and destruction. Another essential virulence factor is Streptolysin O (SLO), a cytotoxin that creates pores in the membranes of host cells, causing cell lysis and tissue damage. This not only aids in the dissemination of the bacteria but also contributes to the hallmark symptoms of scarlet fever. Collectively, these virulence proteins enable S. pyogenes to effectively colonize the host, evade the immune system, and manifest the symptoms associated with scarlet fever. Streptolysin O (SLO) is an oxygen-labile cytotoxin that facilitates pore formation in the process of infection [

13]. This 69kDa protein undergoes cleavage at its N-terminal end by a cysteine proteinase, a crucial step for the translocation of the streptococcal product NAD-glycohydrolase (nga) into host cells [

14]. The membrane domain of SLO is essential for pore formation and acts as a glycan receptor during the binding process. Additionally, Streptolysin O induces the influx of intracellular Ca2+ into host cells, contributing to the pathogenesis of fever [

15].

Presently, there are no vaccine against scarlet fever and this disease is treated with only antibiotics. Vaccine has found to be an effective approach in individuals who are showing resistance to antibiotics. Thus, computational approaches are alternative strategy to the traditional vaccine methodology and have gained momentum in the last few years [

16,

17]. Here, in our study mRNA vaccines approach has been designed targeting the major three virulence proteins involved in the mechanism of causing scarlet rash fever. Here, these proteins M protein , C5a peptidase and Streptolysin O were analyzed with this this versatile mRNA vaccines approach that will induce strong immune response [

18]. To increase the efficiency of translation, codon optimization of the conserved sequence of the targeted proteins were performed. The identification of T-cell and B-cell epitopes were predicted from the sequences of protein and generation and validation of three dimensional structure were constructed [

19,

20]. To validate the strong binding interaction of protein and epitopes, molecular docking were performed and stability of the complex was analyzed through trajectory analysis [

21,

22]. Thus, this research provides a framework for future direction research to design a novel vaccine that could be validated for wet lab analyses in producing a therapeutic striking vaccine against scarlet fever.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of Protein Sequences

The protein sequences of the three key virulence proteins involved in the pathogenesis of scarlet fever were obtained from the NCBI database. Specifically, the C5a peptidase protein with accession number VHB64440.1, the M protein with accession number WYZ30148.1, and the Streptolysin O protein with accession number BAD77794.2. To evaluate their potential as vaccine candidates, the antigenic properties of these proteins were assessed using the Vaxijen tool [

23]. This tool allows us to predict the antigenicity of each protein, providing valuable insights into their ability to induce an immune response. By identifying and analyzing these antigenic properties, we aimed to determine the suitability of these proteins for inclusion in our mRNA vaccine design. This assessment is critical for ensuring that the selected proteins can effectively stimulate the immune system, forming the foundation for a promising therapeutic approach against scarlet fever.

2.2. Codon Optimization and Minimum Energy Calculation

Each protein sequence of the three virulence proteins—C5a peptidase, M protein, and Streptolysin O- was codon-optimized for expression in Homo sapiens. This optimization was aimed at enhancing the expression efficiency of the mRNA vaccine in human cells. The process involved determining the GC content and codon adaptation index (CAI) using the Java Codon Adaptation Tool (JCat) server [

24]. These metrics are crucial as they ensure the optimized sequences are compatible with the host's translational machinery, reflecting effective translation in human cells. After codon optimization, the translated sequences were further analyzed for stability and efficiency. The minimal free energy (MFE) and the energy of the thermodynamic ensemble were calculated using the RNAfold server [

25]. These parameters are essential for predicting the mRNA's secondary structure and stability, which are critical for efficient translation and protein production. By optimizing codon usage and evaluating mRNA stability, we aimed to maximize the expression and immunogenicity of the vaccine candidates. This comprehensive approach ensures that the selected proteins are not only highly antigenic but also efficiently produced within the host, paving the way for a robust and effective mRNA vaccine against scarlet fever.

2.3. Prediction of Secondary Structure

The three-dimensional structures of the proteins—C5a peptidase, M protein, and Streptolysin O- were constructed using the trRosetta tool, which employs deep learning to generate high-quality models based on evolutionary and co-evolutionary data. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of these models, we validated their quality using the ERRAT server [

26]. ERRAT provides a detailed analysis of non-bonded interactions within the protein structures, identifying potential errors and confirming the overall quality of the models. For further validation, we utilized the Ramachandran Plot server, which assesses the dihedral angles of amino acid residues in the proteins. By plotting these angles, we can evaluate the stereochemical quality of the structures. The positions of the residues in the plot reveal the favorability of the protein conformations. The overall scores from both ERRAT and the Ramachandran Plot server will be documented for each protein, ensuring a comprehensive validation of the model quality. This multi-step validation process confirms the accuracy and reliability of the predicted structures, which is crucial for their use in subsequent applications, such as vaccine development. By combining trRosetta's advanced modeling capabilities with rigorous validation through ERRAT and Ramachandran Plot analysis, we ensure the production of high-quality protein structures. These validated models form a strong foundation for our mRNA vaccine design and set the stage for future research and therapeutic interventions against scarlet fever.

2.4. Identification of Linear B-Cell Epitopes

Numerous linear B-cell epitopes were calculated using the ElliPro tool available on the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) server [

26]. The IEDB server offers multiple prediction methods and visually represents the positions of B-cell epitopes within a consensus protein sequence. ElliPro identifies and scores epitopes based on their protrusion index, providing a comprehensive graphical representation of their spatial positions. To further refine our predictions, we also utilized the BepiPred epitope prediction method, which combines a hidden Markov model with a propensity scale method to accurately predict the locations of linear B-cell epitopes. This dual approach ensures a robust identification of potential epitopes. By leveraging these advanced tools, we identified and validated potential B-cell epitopes, crucial for designing an effective mRNA vaccine. The integration of ElliPro's structural analysis with BepiPred's sequence-based predictions enhances our understanding of epitope positions, ensuring that the selected epitopes are likely to elicit a strong immune response. This comprehensive epitope prediction and validation process is critical for developing an effective vaccine strategy, as it ensures that the identified epitopes are both accurate and immunogenic. By employing these sophisticated tools, we can confidently proceed with the design of a robust mRNA vaccine against scarlet fever, paving the way for future research and potential therapeutic applications.

2.5. Physiochemical Properties Prediction

The physicochemical properties of the selected epitopes were extensively analyzed using the ProtParam tool. This analysis is crucial for understanding the structural and functional attributes of the epitopes, which directly impact their stability, solubility, and interaction with the immune system. A higher aliphatic index indicates that the epitope is likely to be more thermostable, suggesting it can retain its structure and functionality even at elevated temperatures. A better understanding of the estimated half-life helps predict how long the epitope will remain effective in these systems, which is critical for its role in inducing a robust immune response. Theoretical pI (Isoelectric Point) indicates the pH at which the epitope has no net electric charge. This information is essential for predicting the epitope's solubility across different pH levels and is useful for optimizing its purification and formulation processes. Molecular weight of the epitope helps determine its size, which is important for various experimental applications such as protein assays, mass spectrometry, and other analytical techniques. GRAVY is calculated by averaging the hydropathy values of all amino acids in the epitope sequence.

2.6. Molecular Docking Interaction

The ClusPro tool was employed for molecular docking to analyze interactions between the selected epitopes and their corresponding MHC-I alleles. This tool generates ten top docked complex conformations based on the lowest binding affinities. It calculates scores considering electrostatic-favored energy, hydrophobic-favored energy, and overall balanced binding energy in kcal/mol. ClusPro enables the docking of receptors and epitopes to determine the most favorable complex structure based on their protein-peptide interactions. The complex with the lowest binding energy is selected for further analysis. This optimal complex can be downloaded, and its structure, including the ligand and protein interactions, can be visualized using Discovery Studio visualizer.

2.7. Normal Mode Analysis (NMA)

The stability of residues and atomic displacement within the docked complex are crucial factors for evaluating the potential efficacy of the epitope. To assess the stability of the complex structure over time, molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using the iMODS server. The simulations were conducted using the iMODS server, focusing on interactions between the candidate vaccine proteins and human immune receptors.The iMODS server was selected for this analysis due to its capability to perform normal mode analysis (NMA), which investigates the structural dynamics of the docking complex and determines molecular motion. iMODS is known for its convenience, customizability, and user-friendly interface. It requires the docked PDB file as input and generates several key metrics, including complex deformability, B-factors, eigenvalues, variance, covariance maps, and an elastic network. This comprehensive analysis provides insights into the dynamic stability of the complex, helping to validate the reliability of the predicted interactions and ensuring the structural integrity of the potential vaccine candidates.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Antigenic Property of Consensus Sequences

The protein sequences for C5a peptidase, M protein, and Streptolysin O were retrieved from the NCBI database. The accession numbers for these proteins are as follows: C5a peptidase with accession number VHB64440.1, M protein with accession number QUG56382.1, and Streptolysin O with accession number BAD77794.2 (see

Table 1). Subsequently, the antigenic properties of all three proteins were evaluated. Each protein was assessed for its potential to elicit an immune response, and all were found to be antigenic, with scores exceeding 0.51. Specifically, the antigenic scores for C5a peptidase (VH1) was 0.5680, M protein (WY2) was 0.7237 and Streptolysin O (BA3) was 0.6405. These scores indicate that the selected proteins have significant potential to stimulate an immune response, making them favorable candidates for further development in vaccine design.

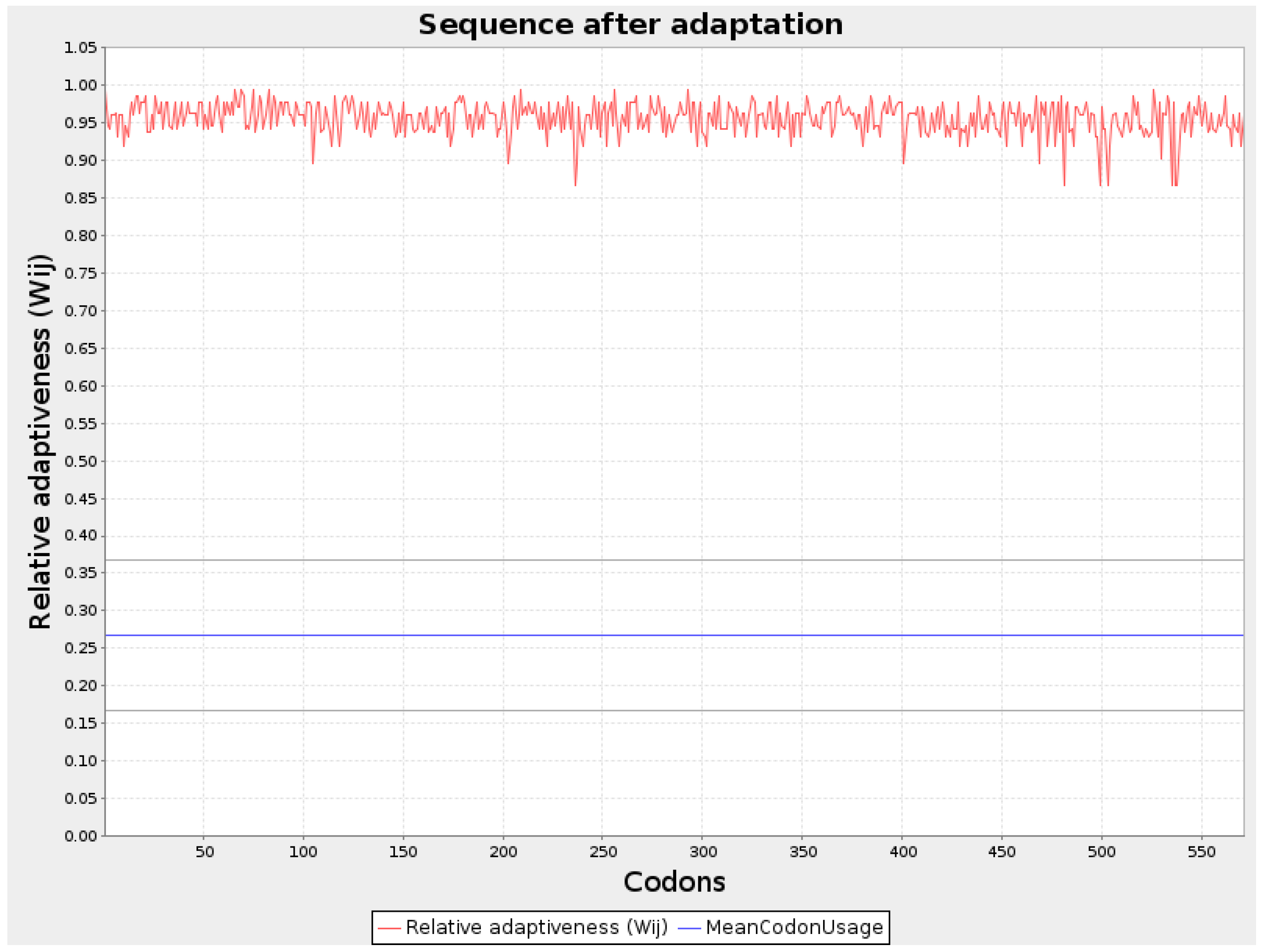

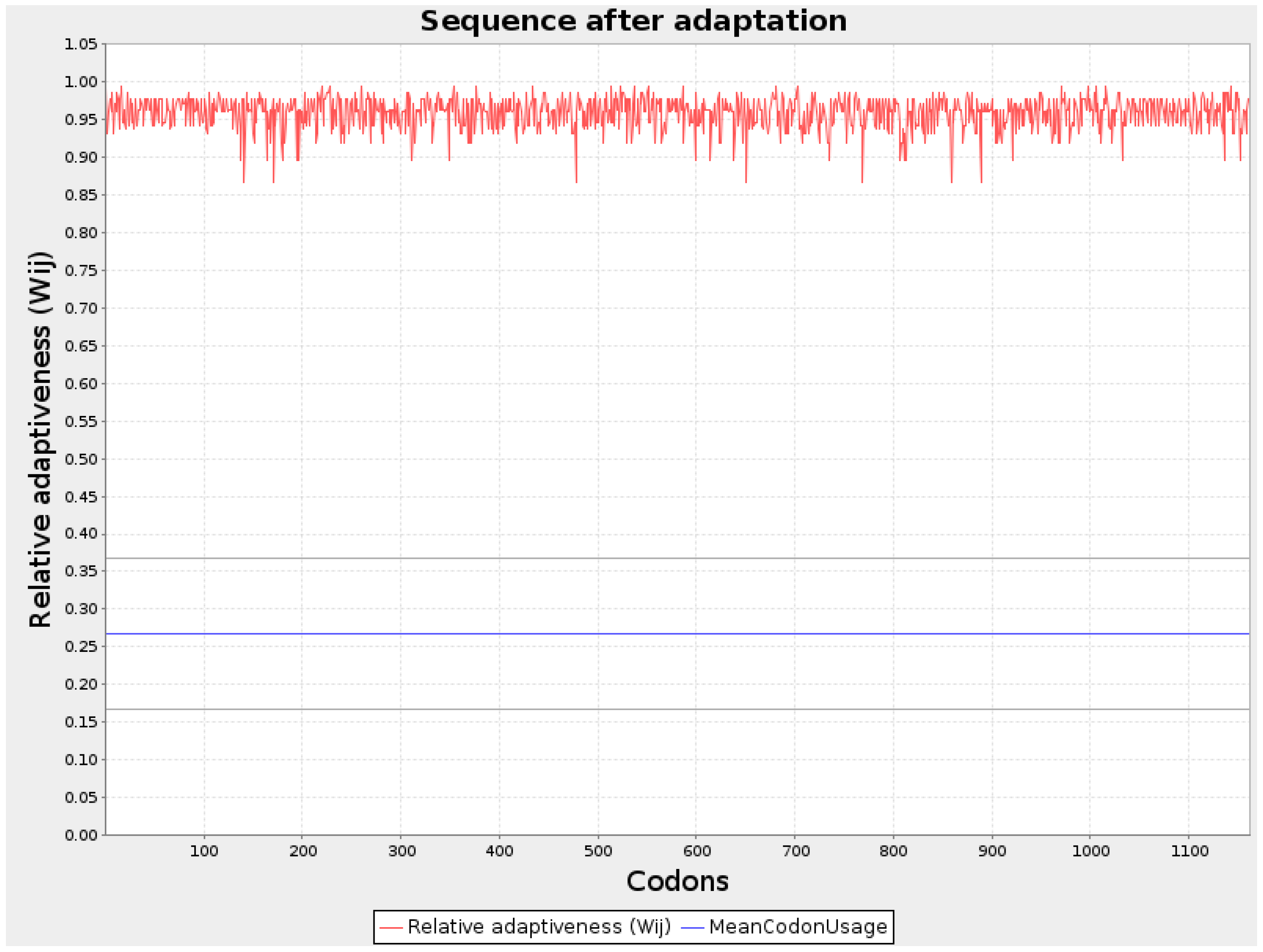

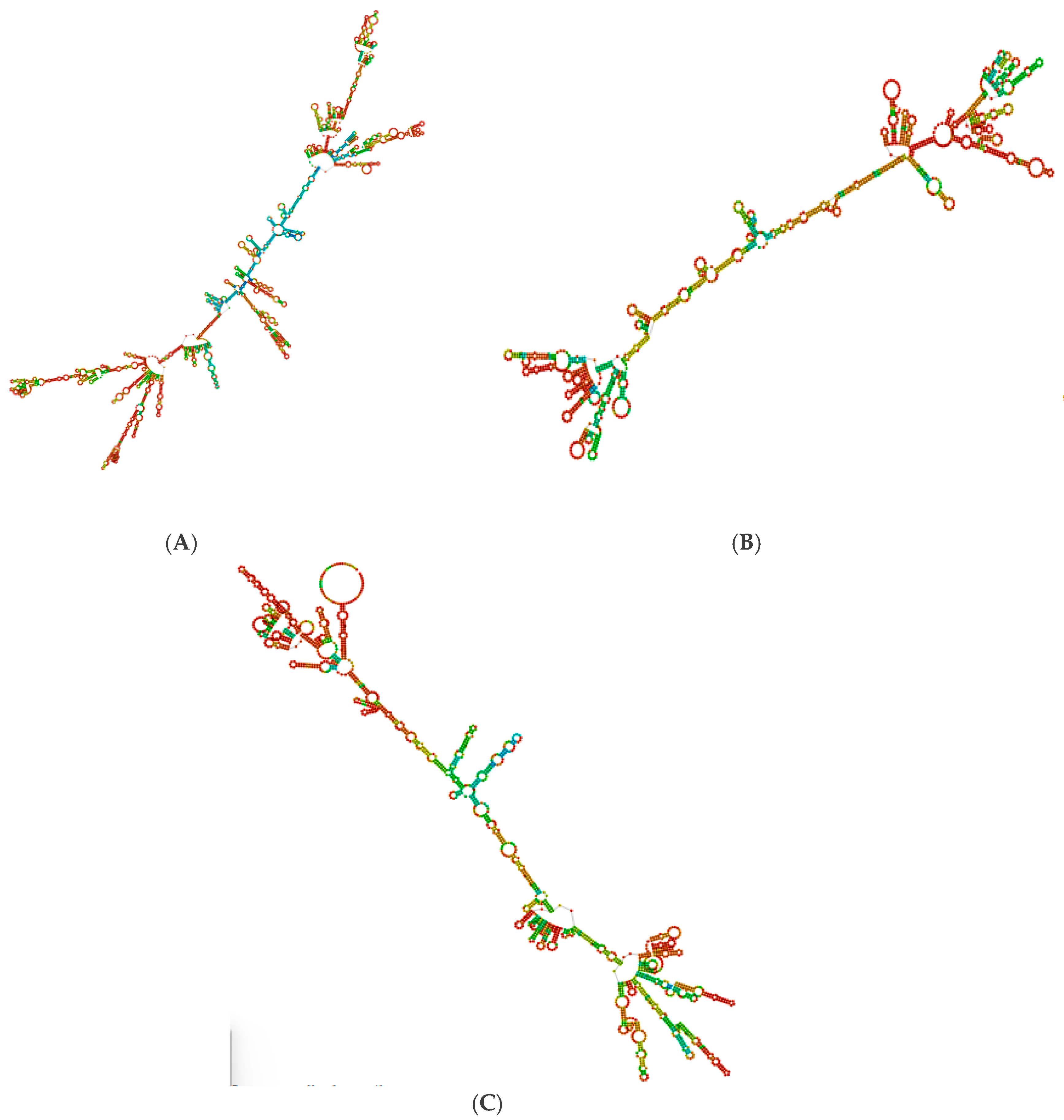

3.2. Codon Optimization and Minimum Energy Calculation

Codon optimization for all three protein sequences was performed using the JCat server, and the values were noted. The GC content (%) for each optimized sequence was as follows: VH1 protein had 66.0%, WY2 had 67.57%, and BA3 had 61.58%. The codon adaptation index (CAI) of the optimized mRNA sequences for VH1, WY2, and BA3 were 0.95, 0.96, and 0.95, respectively. A CAI value above 0.8 indicates that these proteins are well-suited for expression in human cells, making them strong candidates for vaccine development. The thermodynamic stability of the optimized sequences was further analyzed using the RNAfold server, which provided the energy of the thermodynamic ensemble and the minimum free energy (MFE) of the optimal secondary structures. The MFE values for VH1 protein was-1266.20 kcal/mol, for WY2 protein it was obtained as -573.50 kcal/mol and for BA3 protein it was obtained as -543.80 kcal/mol These values, depicted in

Table 2, indicate the stability of the mRNA structures, with lower MFE values suggesting more stable configurations. Graphical representations of the improved nucleotide sequences of the optimized mRNAs are shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The secondary structures of each optimized protein sequence were constructed and are illustrated in

Figure 4. This comprehensive analysis underscores the suitability of the VH1, WY2, and BA3 proteins for further development in vaccine design, supported by their favorable codon optimization metrics and stable secondary structures.

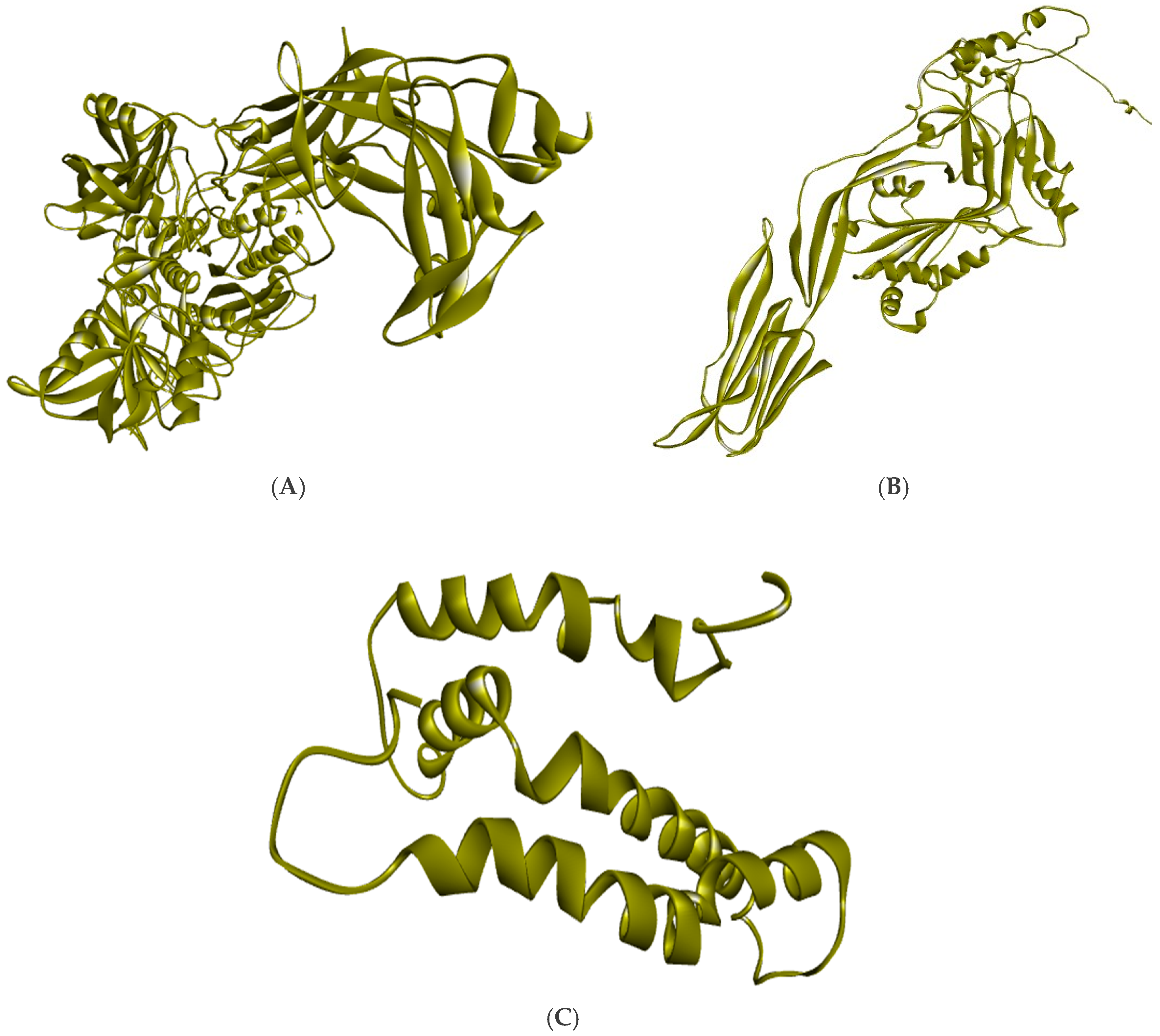

3.3. Generation of Three-Dimensional Structure

Three-dimensional structures provide crucial insights into the functional aspects of proteins. Therefore, the three-dimensional structures of the three proteins- VH1, BA3, and WY2 were constructed using the trRosetta tool and visualized (

Figure 5). The best model for each protein was selected based on the TM score, which indicates the accuracy of the predicted structure. For VH1, the TM score obtained was 0.849, for BA3 score was 0.857 and for WY2 it was 0.867. Further, the quality of these models was further validated using the ERRAT server. The overall quality scores of the BA3 was 90.46%, WY2 was 91.67% and VH1 was 90.86%. These scores indicate high reliability and accuracy, as all models achieved a quality score above 90%. This validation confirms the structural integrity of the models, making them suitable for further functional and interaction studies.

3.4. Identification of Linear B Cell Epitopes

The linear B-cell epitopes for the three consensus protein sequences were identified using the ABCPred tool. This tool utilizes various prediction algorithms and selects epitopes based on their antigenic scores, with a threshold set above 0.35. As we can see in

Table 3, B cell epitopes such as GQAPQAGTKPNQNKAP, AGKASDSQTPDAKPGN and LGHQHAHNEYQAKLAE for WY2 protein, similarly epitopes KVVANGTYTYRVRYTP and SGAKEQHTDFDVIVDN for VH1 protein and epitopes VVLGGDAAEHNKVVTK, TEEINDKIYSLNYNEL and EWWRKVIDERDVKLSK for BA3 protein were selected. The antigenic potential of the selected epitopes was evaluated using the VaxiJen tool. Each epitope achieved a VaxiJen score above 0.5, indicating a strong capability to elicit an immune response. In addition to antigenicity, the toxicity and allergenicity profiles of all identified epitopes were assessed, and they were found to be non-toxic and non-allergenic, thereby confirming their safety for vaccine development. This thorough analysis highlights the robustness of our epitope selection process. By integrating multiple computational tools, we ensured that the identified epitopes are not only highly antigenic but also safe. The high VaxiJen scores, combined with the non-toxic and non-allergenic profiles, make these epitopes excellent candidates for inclusion in an mRNA vaccine. This multi-faceted validation process confirms the immunogenic potential of these epitopes and supports their use in developing a safe and effective vaccine against scarlet fever.

3.5. Prediction of MHC Class I T Cell Epitopes Using Next Generation IEDB Tool

The characterization of T-cell epitopes binding to MHC-I alleles for all three proteins was conducted using the Next Generation IEDB tool. T cells play a crucial role in inducing an effective immune response against antigens. Using the IEDB MHC-class I tool, the protein sequences of each protein were analyzed with an HLA reference set. Based on parameters such as allergenicity, conservation, and antigenicity, scores were generated. The best epitopes with the highest scores were selected for each protein such as EANSKLAAL, NTTNRHYSL, and ATAGVAAVV for WY2 protein, epitopes LTDKTKARY and LQKQYETQY for VH1 protein and epitopes EINDKIYSL, RTYPAALQL, and SQIEAALNV for BA3 protein. These epitopes were further evaluated for their antigenicity, toxicity, and allergenicity. All selected epitopes demonstrated good VaxiJen scores above 0.5, were non-toxic, and non-allergenic (see

Table 4). This rigorous selection process ensures that the identified epitopes are not only effective in eliciting an immune response but also safe for use in vaccine development.

3.6. Prediction of MHC Class-II Alleles

The prediction of T-cell epitopes binding to MHC class II alleles was performed using the IEDB tool with the NetMHC II pan 4.1 algorithm. Sequences were analyzed to select epitopes of 15 amino acids in length. The following epitopes were identified:For WY2 protein- epitope QQYYGNKSNGYKGDW binding to HLA-DRB3*02:02 allele, for VH1 protein- epitope GKPYAAISPNGDGNR binding to HLA-DRB1*04:05 allele and for BA3 protein- epitope TSTEYTSGKINLSHQ binding to HLA-DQB1*03:01 allele. These epitopes were further scrutinized for their antigenicity, toxicity, and allergenicity. All selected epitopes were found to be non-toxic, non-allergenic, and highly immunogenic (see

Table 5). This comprehensive evaluation ensures that the chosen epitopes are effective and safe for use in further vaccine development studies.

3.7. Binding Pattern Analysis

Molecular docking analysis was conducted using the ClusPro tool to investigate the binding interactions between the shortlisted epitopes and their corresponding HLA alleles. ClusPro performs docking by generating multiple conformations and selecting the best ones based on their binding energies. The tool identifies the top 10 docked complexes with the lowest binding energies, and from these, the complexes with the lowest balanced binding energies were selected for further stability analyses. In this study, two epitopes demonstrated the lowest binding energies and were chosen for detailed analysis (see

Table 6). Epitope NTTNRHYSL exhibited a binding energy of -818.5 kcal/mol with the HLA-B08:01 allele, while epitope RTYPAALQL showed a binding energy of -776.5 kcal/mol in complex with the HLA-A32:01 allele. These epitopes were selected due to their favorable binding interactions, indicating strong and stable complexes.

The selected epitopes and their corresponding docked complexes were further visualized to understand their binding conformations and interactions (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). This detailed molecular docking analysis confirms the strong binding affinities of the chosen epitopes to their respective HLA alleles, making them promising candidates for vaccine development. By focusing on the epitopes with the lowest binding energies, this approach ensures that the selected epitopes have a high potential for eliciting a robust immune response. This thorough selection and validation process underscores the potential effectiveness and stability of these epitopes in vaccine design.

3.8. Physiochemical Properties of the Selected Epitopes

We used the ProtParam server to assess the physicochemical properties of the top epitopes. This analysis included parameters such as theoretical isoelectric point (pI), extinction coefficient, aliphatic index, molecular weight, amino acid count, and the Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY).

Table 7 presents the findings: the molecular weight of the epitope NTTNRHYSL was calculated to be 1105.18 Da, while the molecular weight of RTYPAALQL was 1032.21 Da. The estimated half-life for both epitopes in mammalian cells was approximately 1 hour, indicating the duration they are expected to remain stable and functional within these cells. Analyzing these physicochemical parameters provides crucial insights into the properties of the epitopes, helping to ensure that they are stable, soluble, and capable of effectively eliciting an immune response. This thorough assessment supports the development of a robust mRNA vaccine by confirming that the selected epitopes possess the necessary characteristics for successful vaccine performance and efficacy against scarlet fever.

3.9. Simulation Study

Simulation studies were conducted using the iMODS server to evaluate the stability of the protein-epitope-HLA allele complexes. The iMODS server employs Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) to investigate the dynamic behavior and deformability of these complexes under various conditions. Normal Mode Analysis provides crucial information about the flexibility and movement of the complex, offering insights into how it might react to different forces and interactions. This analysis helps in understanding the range of motions the complex can undergo while maintaining its functional integrity. Deformability analysis, on the other hand, examines how the complex deforms under applied stress, which is vital for assessing its stability and overall robustness.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 display the results of these simulations.

Figure 8 illustrates the findings from the normal mode analysis, highlighting the main modes of flexibility and movement of the complex.

Figure 9 presents the deformability analysis, indicating areas of the structure that are more or less susceptible to deformation.

These analyses provide valuable insights into the stability and robustness of the protein-epitope-HLA allele complexes. By understanding the dynamic behavior and deformability, we can better assess the reliability of these complexes for vaccine development. This thorough simulation study reinforces the reliability and potential effectiveness of the vaccine candidates, ensuring they remain stable and functional in practical applications.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the potential of C5a peptidase (VH1), M protein (WY2), and Streptolysin O (BA3) as candidates for the development of a vaccine against scarlet fever. These protein sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database and subjected to various computational analyses to assess their suitability for vaccine design. One of the key factors in determining the vaccine potential of these proteins is their antigenicity. The antigenic potential of VH1, WY2, and BA3 was evaluated using antigenic prediction tools, revealing that all three proteins had antigenic scores above 0.51. These scores suggest that the proteins have the potential to elicit an immune response, making them strong candidates for vaccine development. The ability of these proteins to trigger immune responses is crucial for their consideration as vaccine targets. In addition to antigenicity, codon optimization was performed to enhance the expression of these proteins in human cells. The optimization results showed favourable GC content for all three proteins: VH1 (66.0%), WY2 (67.57%), and BA3 (61.58%), which are within the ideal range for efficient expression. This aspect is critical for large-scale production of the proteins, a vital step in vaccine development. The thermodynamic stability of the mRNA sequences was also assessed to ensure that the optimized proteins would have stable secondary structures when expressed. Minimum free energy (MFE) values obtained indicated that all three proteins exhibited stable mRNA structures, with lower MFE values suggesting more stable configurations. The stability of the mRNA is important for ensuring that the protein will be properly expressed and function effectively within human cells.

Further structural characterization indicated high prediction accuracy, which was further validated using the ERRAT server. These models showed excellent quality (all above 90%), confirming the structural integrity of the proteins and their potential for functional studies. B-cell epitopes, essential for initiating an antibody-mediated immune response, were identified using the ABCPred tool. All selected epitopes demonstrated antigenic scores above 0.5 and were found to be non-toxic and non-allergenic, making them suitable for inclusion in a vaccine [28]. For example, epitopes such as GQAPQAGTKPNQNKAP (WY2) and KVVANGTYTYRVRYTP (VH1) were identified as potent candidates. These findings highlight the robustness of the epitope selection process, ensuring that the identified regions are both antigenic and safe for vaccine development. T-cell epitopes, which are crucial for inducing cellular immunity, were also predicted for both MHC-I and MHC-II alleles. For MHC-I, epitopes such as NTTNRHYSL (WY2) and RTYPAALQL (BA3) were selected due to their high antigenicity, and for MHC-II, epitopes like QQYYGNKSNGYKGDW (WY2) were identified. These epitopes were further analyzed for toxicity and allergenicity and were found to be non-toxic and non-allergenic, reinforcing their potential as safe vaccine candidates. Molecular docking analysis using showed that epitopes NTTNRHYSL and RTYPAALQL had strong binding affinities. These findings suggest that these epitopes form stable complexes with their HLA alleles, which is essential for eliciting a robust immune response. The strong binding affinities further support the potential of these epitopes in vaccine development. Physicochemical properties of the epitopes were assessed to ensure their stability and functionality in a biological system. Both the predicted epitopes were found to have appropriate molecular weights and stability profiles, indicating that they would be suitable for inclusion in a vaccine [29–31]. Additionally, the predicted half-lives of approximately one hour in mammalian cells suggest that these epitopes will remain stable long enough to provoke an immune response. Finally, the stability of the protein-epitope-HLA complexes was evaluated through simulation studies using the iMODS server. Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) and deformability analysis provided insights into the flexibility and structural robustness of the complexes, ensuring their stability under various conditions. These simulations confirmed that the complexes maintain functional integrity, which is essential for their role in inducing an effective immune response. The comprehensive analysis of VH1, WY2, and BA3 demonstrated that these proteins possess the necessary attributes for successful vaccine development. Their antigenic potential, codon optimization for efficient expression, stable secondary structures, and promising epitope profiles all support their use in developing a safe and effective vaccine against scarlet fever. The detailed computational approach used in this study highlights the potential of these proteins and their epitopes as strong candidates for future vaccine development.

5. Conclusions

The development of mRNA-based vaccines offers significant advantages, including accelerated production, cost reduction, and enhanced immune responses. Based on our immunoinformatics analysis, our designed mRNA vaccine demonstrates the potential to effectively elicit an immune response against scarlet fever. Our study identifies two promising peptides, NTTNRHYSL and RTYPAALQL, which are predicted to induce immunity against the disease. These peptides were selected through rigorous in silico analyses, underscoring the value of computational approaches in designing effective mRNA vaccines for scarlet fever and potentially other infectious diseases. Despite the promising results, computational methods have limitations, such as reliance on available datasets and predictive models. Therefore, it is crucial to validate these findings through in vitro and in vivo experiments. By conducting these bioassays, we can confirm the efficacy and safety of the selected peptides, ensuring their suitability for vaccine development.

This thorough evaluation process, which combines advanced computational tools with rigorous safety assessments, confirms that the chosen epitopes are both effective and safe. The successful identification and validation of these epitopes provide a strong foundation for developing a robust mRNA vaccine against scarlet fever. These findings set the stage for future experimental studies and therapeutic applications, aiming to mitigate the impact of scarlet fever through innovative vaccine strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, software, validation, and formal analysis, investigation, F.K and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, F.K. and S.R.; visualization and supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Rama University, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh (India) for providing necessary facilities to conduct this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hubner, J.; Jansson, A. Scarlet fever. MMW Fortschr Med. 2012, 154, 57–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lamden, K.H. An outbreak of scarlet fever in a primary school. Arch Dis Child. 2011, 96, 394–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, M.R. Pharyngitis and Scarlet Fever. In Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]; Ferretti, J.J., Stevens, D.L., Fischetti, V.A., Eds.; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, M. Impact of meteorological factors on scarlet fever in Jiangsu province, China. Public Health. 2018, 161, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.F.; Cowling, B.J.; Lau, E.H.Y. Epidemiology of Reemerging Scarlet Fever, Hong Kong, 2005-2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017, 23, 1707–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, J. Acute bacterial skin infections in pediatric medicine: current issues in presentation and treatment. Paediatr Drugs 2003, 5 (Suppl. 1), 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chalker, V.; Jironkin, A.; Coelho, J.; Al-Shahib, A.; Platt, S.; Kapatai, G.; Daniel, R.; Dhami, C.; Laranjeira, M.; Chambers, T.; et al. Genome analysis following a national increase in Scarlet Fever in England 2014. BMC Genomics. 2017, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapetis, J.R.; Steer, A.C.; Mulholland, E.K.; Weber, M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2005, 5, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmcke, S.; Shannon, O.; Mörgelin, M.; Herwald, H. Streptococcal M proteins and their role as virulence determinants. Clin Chim Acta. 2010, 411, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancefield, R.C. The antigenic complex of Streptococcus hemolyticus. I Demonstration of a type-specific substance in extracts of Streptococcus hemolyticus. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1928, 47, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, M.T.; Scott, A.; Cherevach, I.; et al. Complete genome of acute rheumatic fever-associated serotype M5 Streptococcus pyogenes strain Manfredo. J Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernie-King, B.A.; Seilly, D.J.; Willers, C.; Würzner, R.; Davies, A.; Lachmann, P.J. Streptococcal inhibitor of complement (SIC) inhibits the membrane attack complex by preventing uptake of C567 onto cell membranes. Immunology 2001, 103, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, J.; Franchi, L.; Muñoz-Planillo, R.; Park, J.H.; Reimer, T.; Núñez, G. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome by Streptococcus pyogenes requires streptolysin O and NF-kappa B activation but proceeds independently of TLR signaling and P2X7 receptor. Journal of Immunology 2009, 183, 5823–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozola, C.C.; Caparon, M.G. Dual modes of membrane binding direct pore formation by Streptolysin O. Molecular Microbiology 2015, 97, 1036–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, L.K.; Håkansson, A.P.; Cortés, G.; Wessels, M.R. Streptolysin O inhibits clathrin-dependent internalization of group A Streptococcus. MBio 2011, 2, e00332–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fariya, K.; Ajay, K. An integrative docking and simulation-based approach towards the development of epitope-based vaccine against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinform 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fariya, K.; Vivek, S.; Ajay, K. Epitope based peptide prediction from proteome of enterotoxigenic E. coli. Int J Pept Res Ther 2018, 24, 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Cleary, P.P. Complete nucleotide sequence of the streptococcal C5a peptidase gene of Streptococcus pyogenes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 1990, 265, 3161–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariya, K.; Vivek, S.; Ajay, K. Computational identification and characterization of potential T-cell epitope for the utility of vac cine design against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Int J Pept Res Ther 2019, 25, 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bano, N.; Kumar, A. Immunoinformatics study to explore dengue (DENV-1) proteome to design multi-epitope vaccine construct by using CD4+ epitopes. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2023, 21, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabin, D.; Kumar, A. T-cell epitope-based vaccine prediction against Aspergillus fumigatus: a harmful causative agent of aspergillosis. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2022, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, I.; Naneva, L.; Doytchinova, I.; Bangov, I. AllergenFP: allergenicity prediction by descriptor fingerprints. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinform 2007, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, A.; Hiller, K.; Scheer, M.; Münch, R.; Nörtemann, B.; Hempel, D.C.; Jahn, D. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W526–W531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Martin, J.A.; Clote, P.; Dotu, I. RNAiFold: a web server for RNA inverse folding and molecular design. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, W465–W470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colovos, C.; Yeates, T.O. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 1511–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, R.; Mahajan, S.; Overton, J.A.; Dhanda, S.K.; Martini, S.; Cantrell, J.R.; Wheeler, D.K.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D339–D343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajay Castro, S.; Dorfmueller, H.C. Update on the development of Group A Streptococcus vaccines. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Krammer, F. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases — advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2024, 23, 838–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Khan, F.; Kumar, A. Exploring Highly Antigenic Protein of Campylobacter jejuni for Designing Epitope Based Vaccine: Immunoinformatics Approach. Int J Pept Res Ther 2019, 25, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Kumar, A. Vaccine Design and Immunoinformatics. In Advances in Bioinformatics; Singh, V., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, Fariya Khan, Mohsin Vahid Khan, Ajay Kumar and Salman Akhtar Recent Advances in the Development of Alpha-Glucosidase and Alpha-Amylase Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Management: Insights from In silico to In vitro Studies. 2024, 24, 12, 782- 795.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of BA3 protein.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of BA3 protein.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of WY2 protein.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of WY2 protein.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of VH1 protein.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of Codon optimization of VH1 protein.

Figure 4.

Secondary structure of optimized protein sequences (A) VH1 protein (B) WY2 protein (C) BA3.

Figure 4.

Secondary structure of optimized protein sequences (A) VH1 protein (B) WY2 protein (C) BA3.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional structure of (A) VH1 protein (B) BA3 protein (C) WY2.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional structure of (A) VH1 protein (B) BA3 protein (C) WY2.

Figure 6.

Visualization of Docked complex of NTTNRHYSL with their corresponding HLA-B*08:01 (A) Pictorial view of interaction of epitope (B) Epitope and receptor interaction showing the residues with strong hydrogen bond.

Figure 6.

Visualization of Docked complex of NTTNRHYSL with their corresponding HLA-B*08:01 (A) Pictorial view of interaction of epitope (B) Epitope and receptor interaction showing the residues with strong hydrogen bond.

Figure 7.

Visualization of Docked complex of RTYPAALQL with their corresponding HLA-A*32:01 (A) Pictorial view of interaction of epitope (B) Epitope and receptor interaction showing the residues with strong hydrogen bond.

Figure 7.

Visualization of Docked complex of RTYPAALQL with their corresponding HLA-A*32:01 (A) Pictorial view of interaction of epitope (B) Epitope and receptor interaction showing the residues with strong hydrogen bond.

Figure 8.

Normal mode analysis (NMA) of NTTNRHYSL docked complex by iMODs. server (A) Cartoon visualization; (B) main-chain deformability; (C) the eigenvalue (D) Variance (E) co variance map; (F) elastic network of model.

Figure 8.

Normal mode analysis (NMA) of NTTNRHYSL docked complex by iMODs. server (A) Cartoon visualization; (B) main-chain deformability; (C) the eigenvalue (D) Variance (E) co variance map; (F) elastic network of model.

Figure 9.

Normal mode analysis (NMA) of RTYPAALQL docked complex by iMODs. server (A) Cartoon visualization; (B) main-chain deformability; (C) the eigenvalue (D) Variance (E) co variance map; (F) elastic network of model.

Figure 9.

Normal mode analysis (NMA) of RTYPAALQL docked complex by iMODs. server (A) Cartoon visualization; (B) main-chain deformability; (C) the eigenvalue (D) Variance (E) co variance map; (F) elastic network of model.

Table 1.

Details of the proteins used in the design of the vaccine.

Table 1.

Details of the proteins used in the design of the vaccine.

| Protein code |

Protein |

Accession number |

VaxiJen score |

| VH1 |

C5a peptidase |

VHB64440.1 |

0.5680 |

| WY2 |

M protein |

QUG56382.1 |

0.7237 |

| BA3 |

Streptolysin O |

BAD77794.2 |

0.6405 |

Table 2.

Codon Optimization and minimum free energy calculation.

Table 2.

Codon Optimization and minimum free energy calculation.

| Parameters |

VH1 |

WY2 |

BA3 |

| Codon adaptation index (CAI) |

0.95 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

| GC content (%) |

66.0 |

67.57 |

61.58 |

| Minimum free energy (MFE) of optimal secondary structure |

-1266.20 kcal/mol |

-573.50 kcal/mol |

-543.80 kcal/mol |

| Free energy of centroid secondary structure |

-1035.53 kcal/mol |

-454.33 kcal/mol |

-444.99 kcal/mol |

| Energy of thermodynamic ensemble |

-1308.82 kcal/mol. |

-590.06 kcal/mol |

-568.58 kcal/mol |

Table 3.

Physiochemical properties of identified Linear B cell epitopes through ABCPred tool.

Table 3.

Physiochemical properties of identified Linear B cell epitopes through ABCPred tool.

| Proteins |

Epitopes |

Antigenicity |

Allergenecity |

Toxicity |

| WY2 |

GQAPQAGTKPNQNKAP |

0.9310 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| AGKASDSQTPDAKPGN |

1.8356 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| LGHQHAHNEYQAKLAE |

0.8217 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| VH1 |

KVVANGTYTYRVRYTP |

0.9039 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| SGAKEQHTDFDVIVDN |

1.1516 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| BA3 |

VVLGGDAAEHNKVVTK |

0.7168 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| TEEINDKIYSLNYNEL |

0.6260 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| EWWRKVIDERDVKLSK |

0.8261 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

Table 4.

Identification of MHC-I T cell epitopes through Next generation IEDB tool.

Table 4.

Identification of MHC-I T cell epitopes through Next generation IEDB tool.

| Protein |

Epitopes |

Alleles |

Vaxijen score |

Allergenecity |

Toxicity |

| WY2 |

EANSKLAAL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

0.8333 |

Non-Allergen |

Non-toxic |

| NTTNRHYSL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

0.7449 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| ATAGVAAVV |

HLA-A*68:02 |

0.8382 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| VH1 |

LTDKTKARY |

HLA-A*01:01 |

0.5844 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| LQKQYETQY |

HLA-B*15:01 |

0.5753 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| BA3 |

EINDKIYSL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

0.5911 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| RTYPAALQL |

HLA-A*32:01 |

0.7161 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| SQIEAALNV |

HLA-A*02:06 |

0.7757 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

Table 5.

Identification of MHC-II alleles using IEDB tool.

Table 5.

Identification of MHC-II alleles using IEDB tool.

| Protein |

Epitopes |

Alleles |

Vaxijen score |

Allergenecity |

Toxicity |

| WY2 |

QQYYGNKSNGYKGDW |

HLA-DRB3*02:02 |

0.8556 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| VH1 |

GKPYAAISPNGDGNR |

HLA-DRB1*04:05 |

1.1708 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

| BA3 |

TSTEYTSGKINLSHQ |

HLA-DQB1*03:01 |

0.9395 |

Non-allergen |

Non-toxic |

Table 6.

Binding energy prediction of the selected MHC-I T cell epitopes through Cluspro tool.

Table 6.

Binding energy prediction of the selected MHC-I T cell epitopes through Cluspro tool.

| Epitopes |

Alleles |

Electrostatic-favored energy (kcal/mol) |

Hydrophobic-favored energy (kcal/mol) |

Binding Energy(kcal/mol) |

| EANSKLAAL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

-557.0 |

-654.9 |

-543.0 kcal/mol |

| NTTNRHYSL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

-863.9 |

-956.3 |

-818.5 kcal/mol |

| ATAGVAAVV |

HLA-A*68:02 |

-581.3 |

-758.8 |

-580.6 kcal/mol |

| LTDKTKARY |

HLA-A*01:01 |

-735.0 |

-885.9 |

-613.5 kcal/mol |

| LQKQYETQY |

HLA-B*15:01 |

-697.6 |

-850.0 |

-689.6 kcal/mol |

| EINDKIYSL |

HLA-B*08:01 |

-637.3 |

-790.4 |

-632.3 kcal/mol |

| RTYPAALQL |

HLA-A*32:01 |

-817.9 |

-925.7 |

-776.5 kcal/mol |

| SQIEAALNV |

HLA-A*02:06 |

-564.9 |

-810.0 |

-575.3 kcal/mol |

Table 7.

Physiochemical characteristics of the selected top two epitopes.

Table 7.

Physiochemical characteristics of the selected top two epitopes.

| Parameter |

NTTNRHYSL |

RTYPAALQL |

| Molecular weight |

1105.18 |

1032.21 |

| Theoretical pI |

8.75 |

8.75 |

| Estimated half-life |

1.4 hours (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro).

3 min (yeast, in vivo).

>10 hours (Escherichia coli, in vivo). |

1 hours (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro).

2 min (yeast, in vivo).

2 min (Escherichia coli, in vivo). |

| Aliphatic index: |

43.33 |

108.89 |

| Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) |

-1.600 |

-0.044 |

| Total number of atoms |

150 |

150 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).