Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Pianists | Physicists |

|---|---|

| Focus on the sensory elements and expressiveness of the performance. | Focus on the physical/mechanical principles of sound generation. |

| Explain that the sound differs by "touch" and "expression." | Explain the difference in sound according to the force, speed, and physical qualities. |

1.1. History of Piano Timbre

1.2. The Principle of Piano Sound

1.3. Piano Timbre Analysis from a Physical Point of View

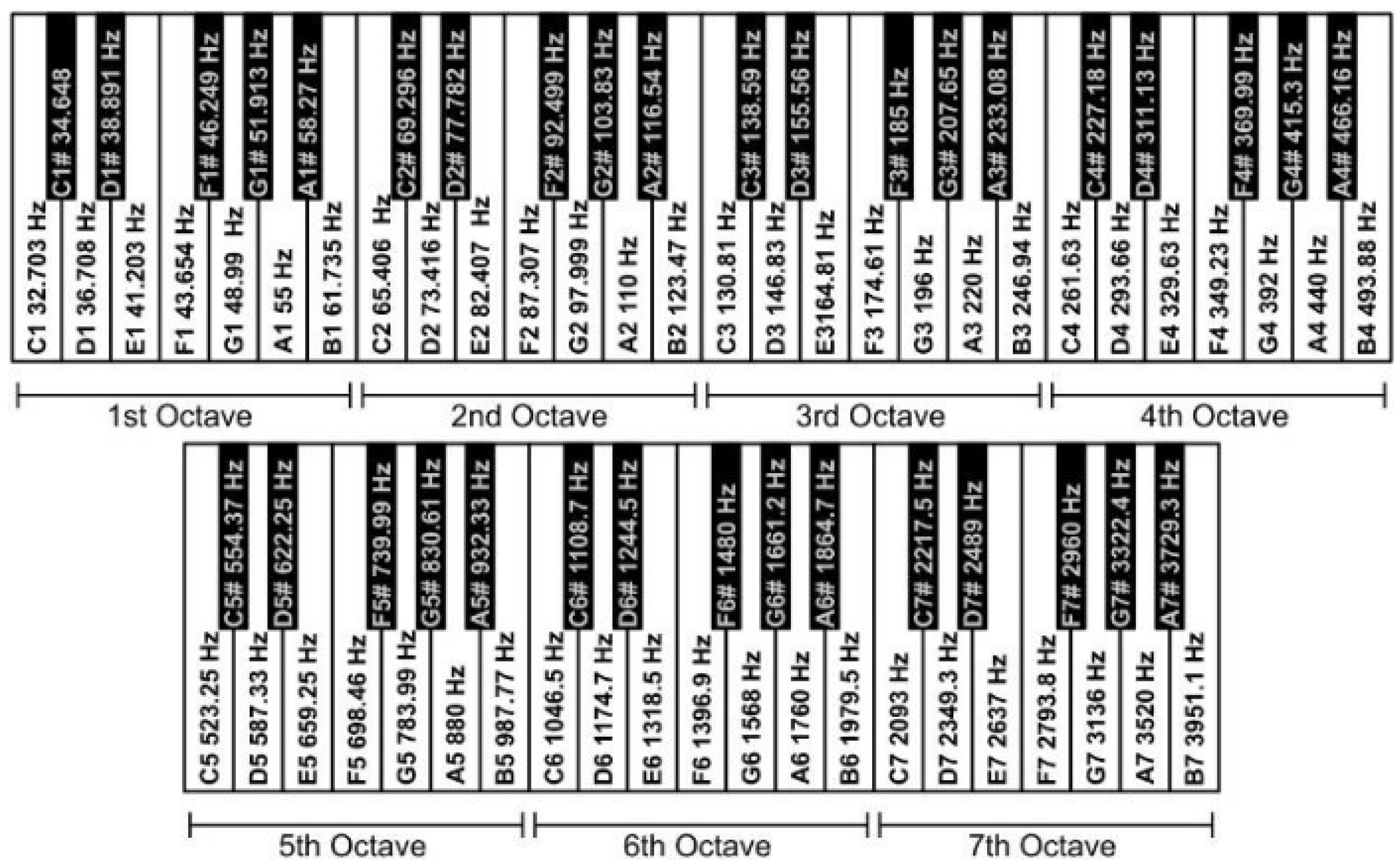

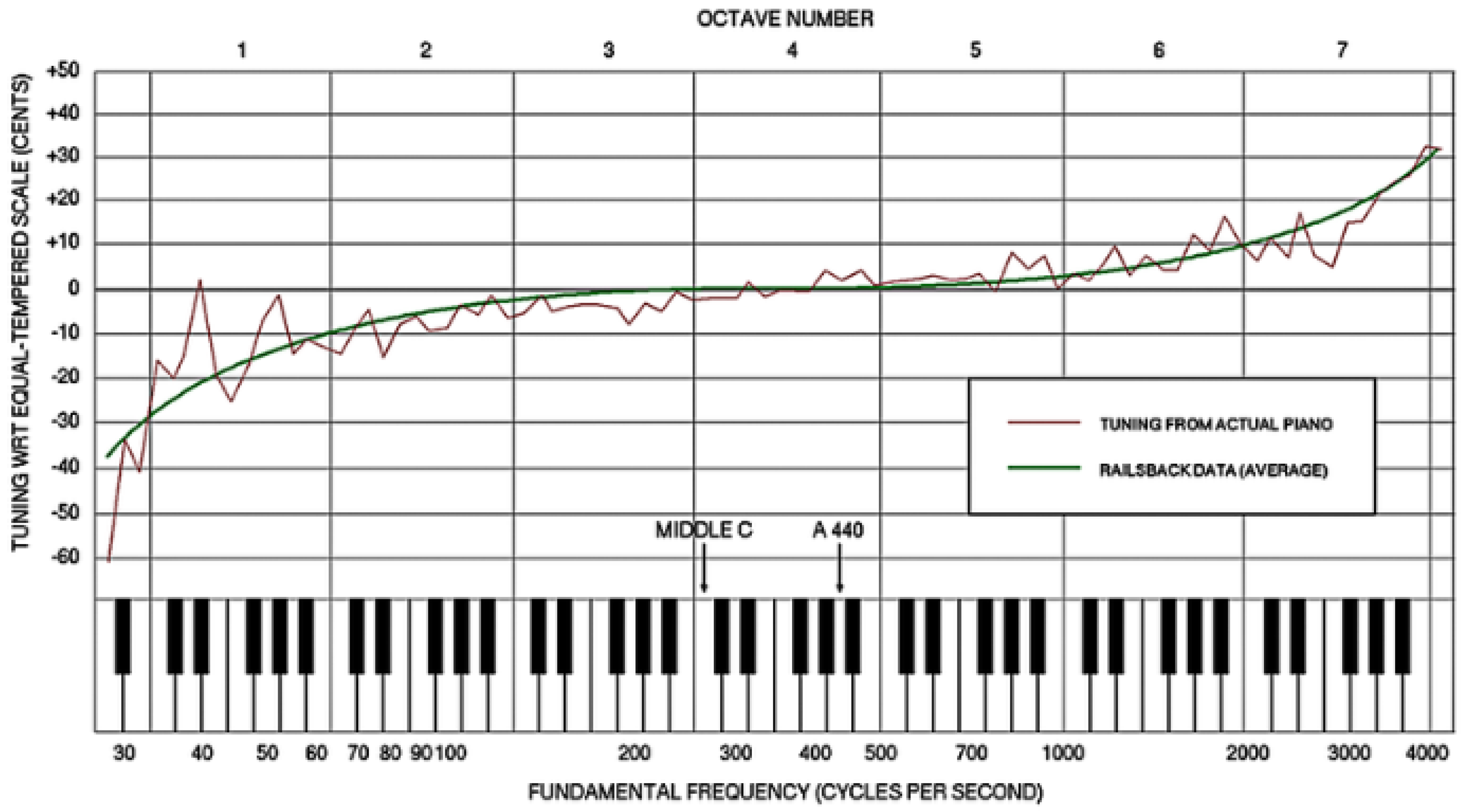

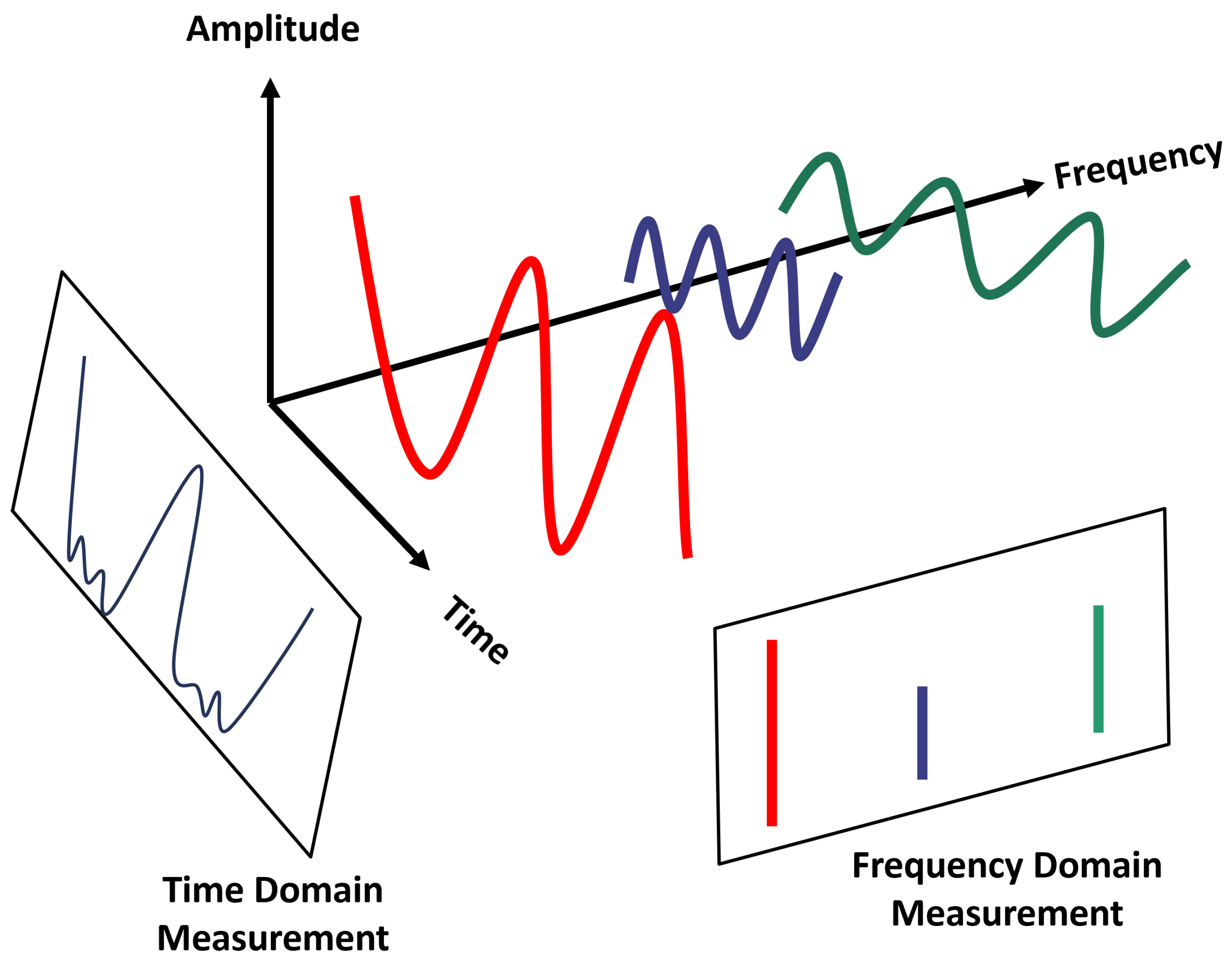

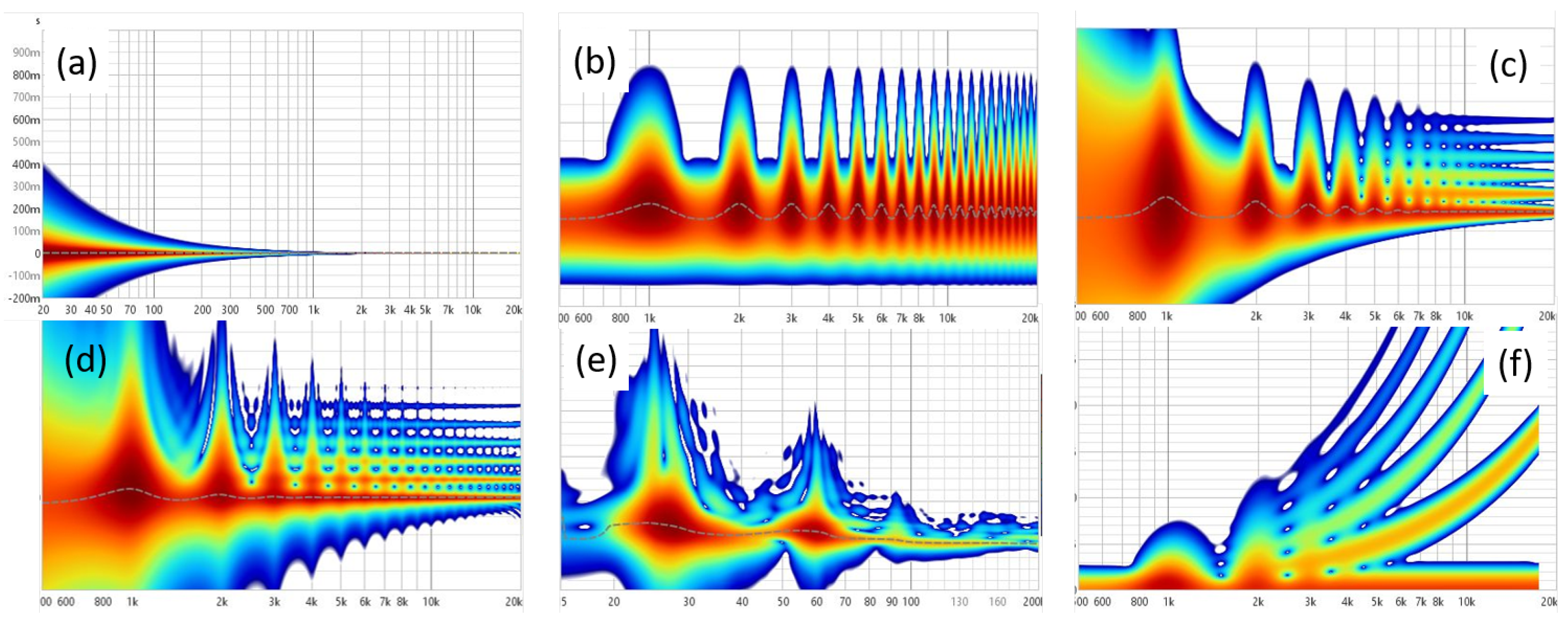

1.3.1. Frequency

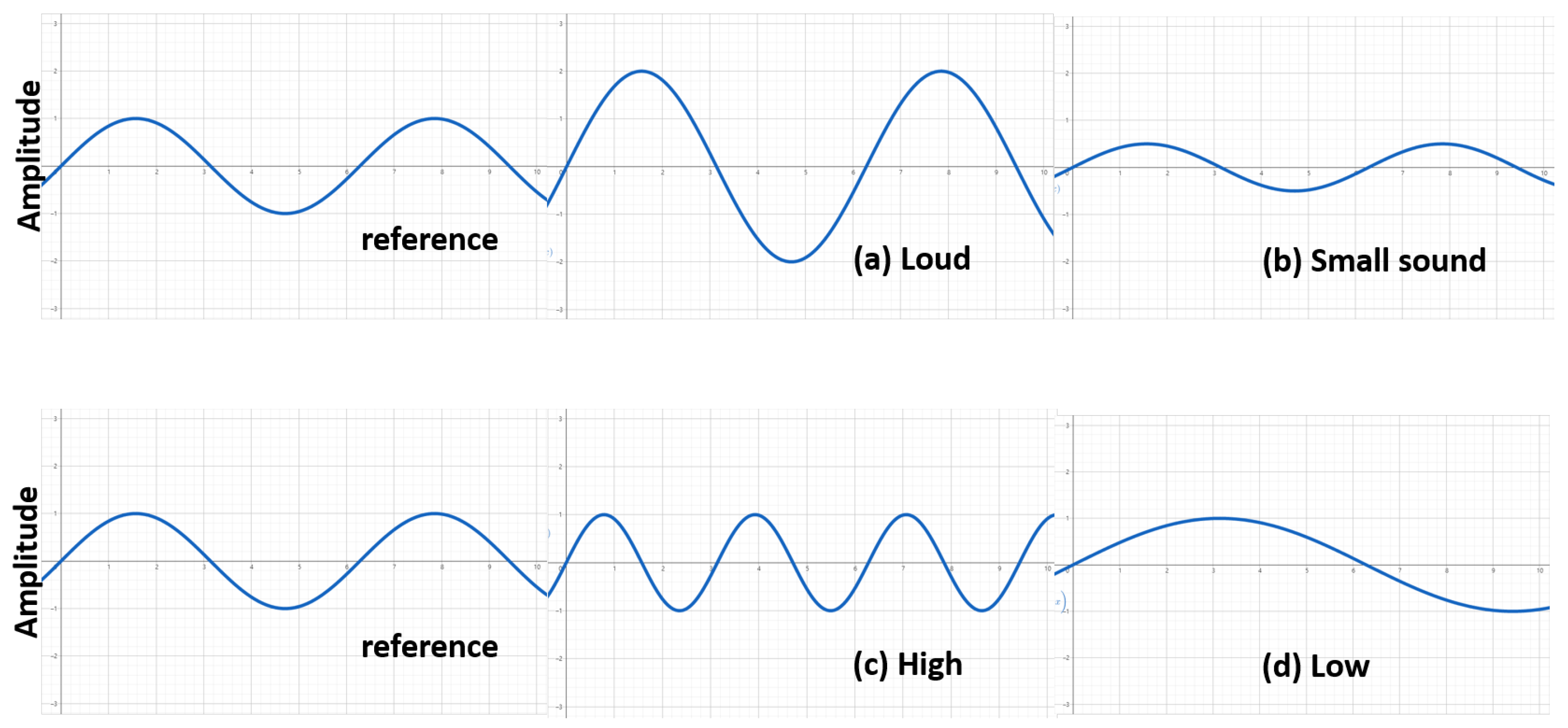

1.3.2. Amplitude

1.3.3. Time Domain

1.3.4. Resonance

2. Methods

2.1. Wave Function for Physical Analysis

| Wavelet Transform | STFT | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency resolution | High at low frequency, low at high frequency | Fixed frequency resolution |

| Time resolution | High at high frequency, low at low frequency | Fixed time resolution |

| Short event analysis | More effective | Relatively less effective |

| Calculation amount | Efficient | relatively computationally efficient |

| Application | Abnormal Signal Analysis, Compression, Noise Elimination | Rhythm, Spectrogram-Based Analysis |

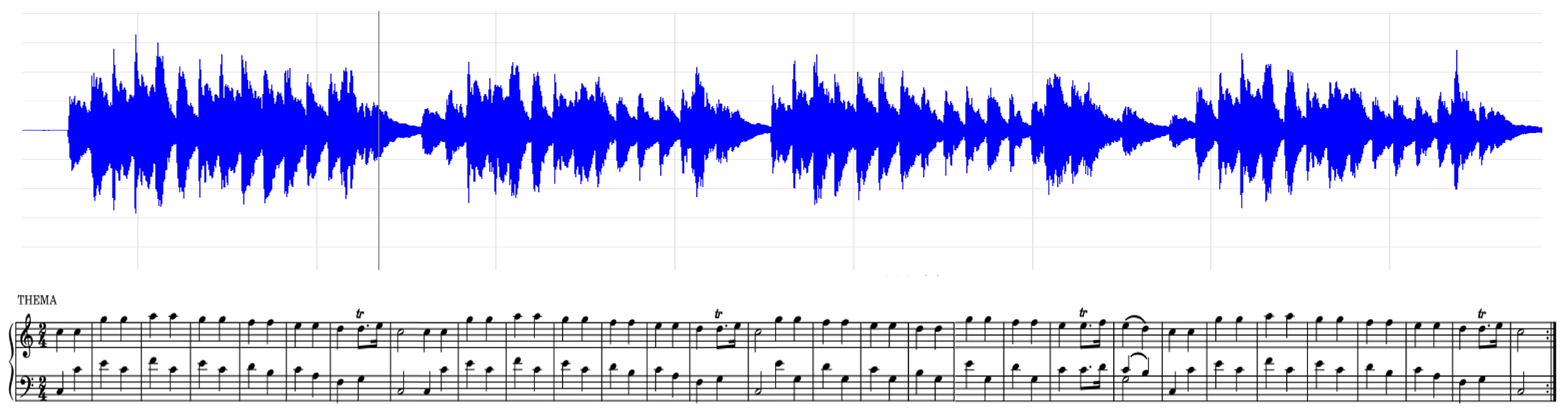

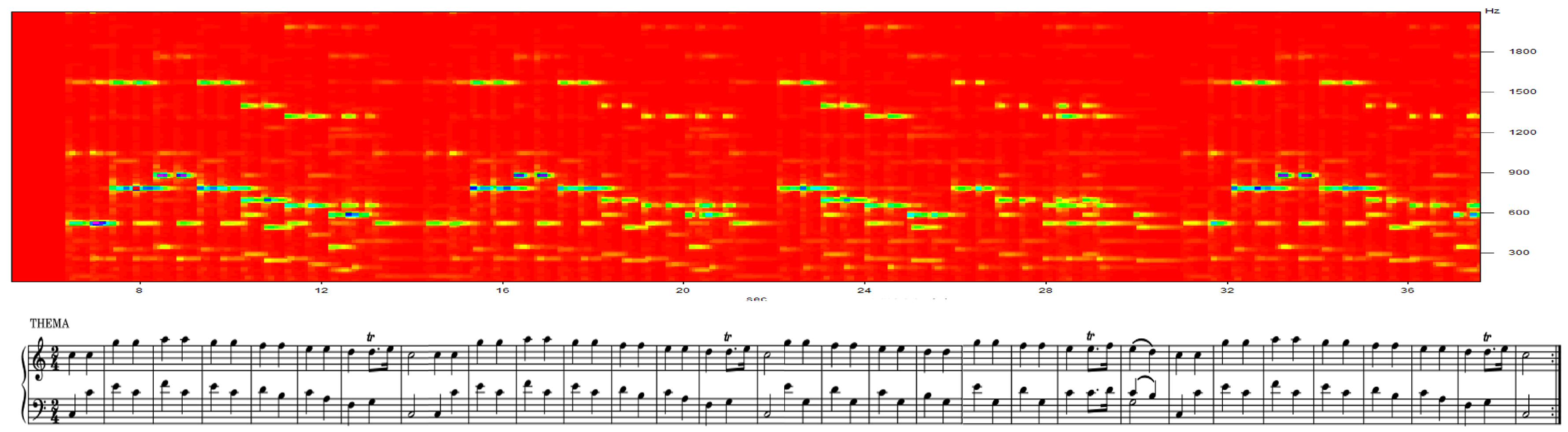

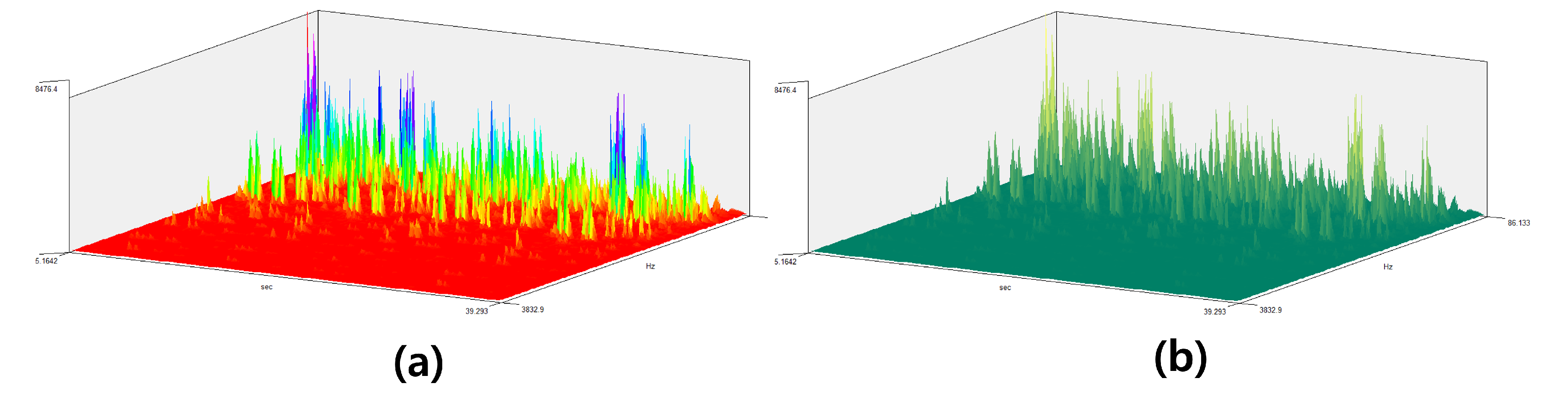

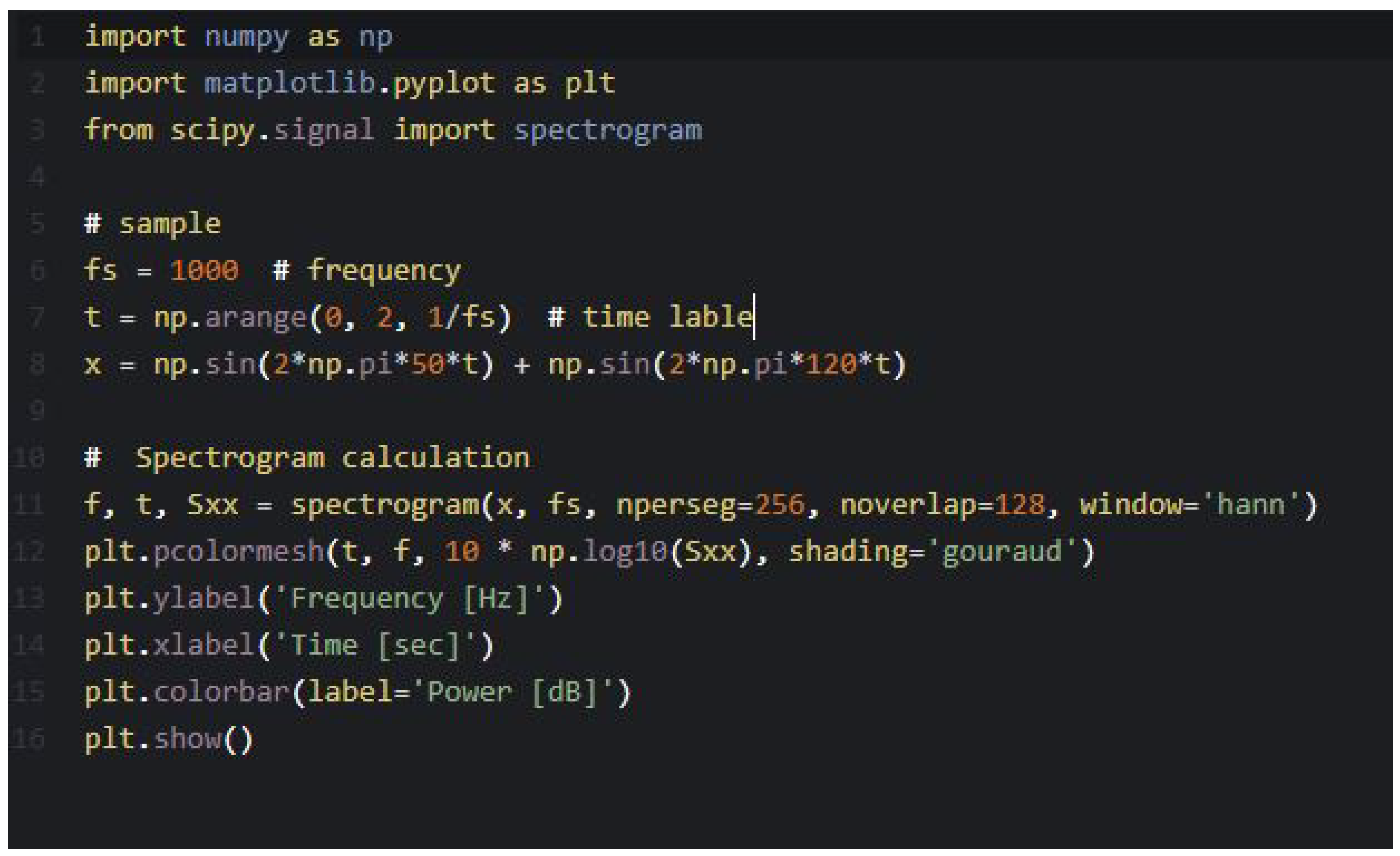

2.2. Spectrogram Analysis

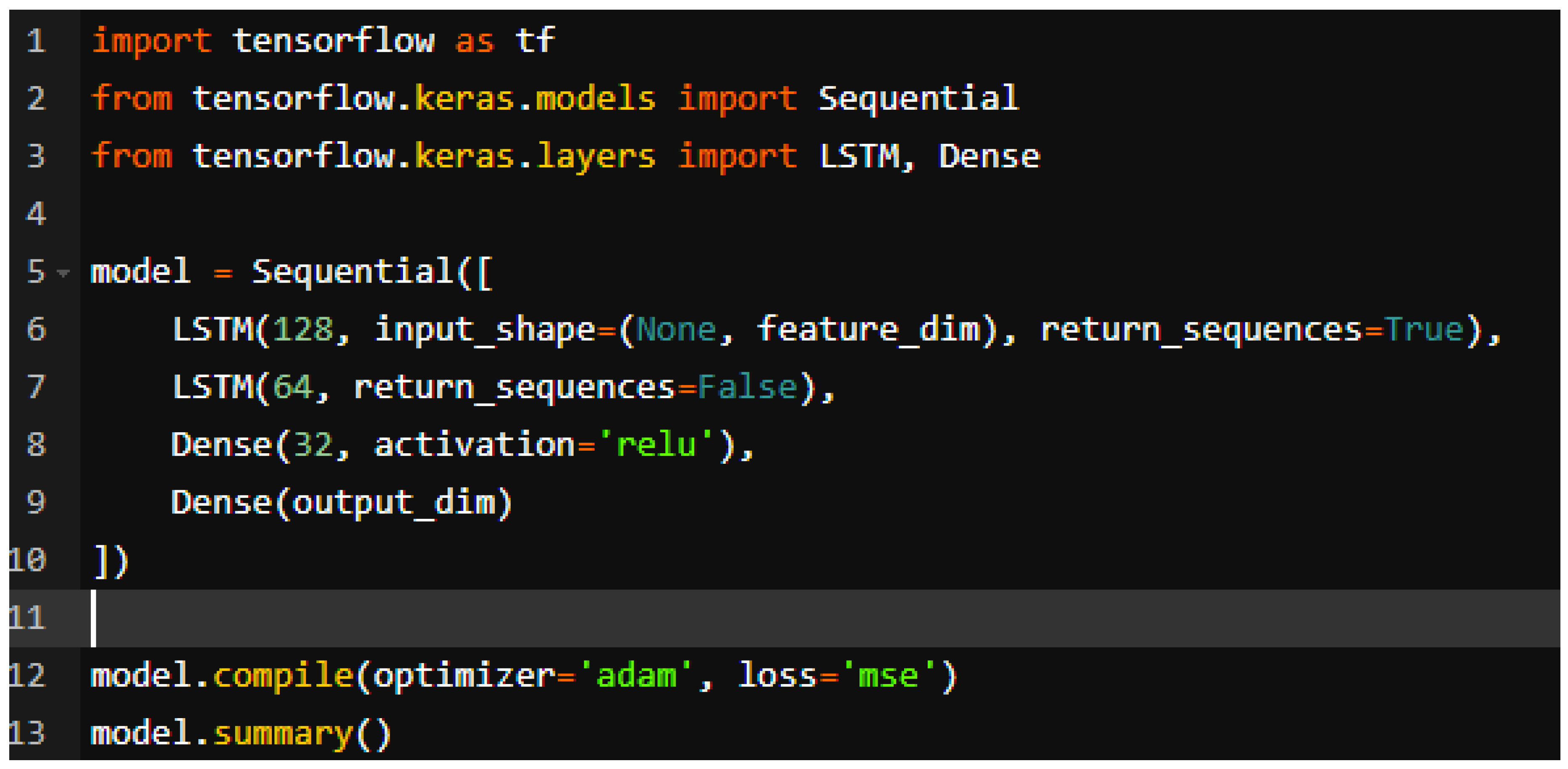

2.3. Deep Learning Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Future Work

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Bank, B.; Avanzini, F.; Borin, G.; De Poli, G.; Fontana, F.; Rocchesso, D. Physically informed signal processing methods for piano sound synthesis: a research overview. EURASIP journal on advances in signal processing 2003, 2003, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, B.; Sujbert, L. Generation of longitudinal vibrations in piano strings: From physics to sound synthesis. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2005, 117, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackham, E.D. The physics of the piano. Scientific american 1965, 213, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, N.J. Physics of the Piano; Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Kochevitsky, G. The art of piano playing: A scientific approach; Alfred Music, 1995.

- Kulcsár, D.; Fiala, P. A compact physics-based model of the piano. Proceedingd of DAGA 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhala, J.; et al. Physics-Based Parametric Synthesis of Inharmonic Piano Tones; Helsinki University of Technology, 2007.

- Simionato, R.; Fasciani, S.; Holm, S. Physics-informed differentiable method for piano modeling. Frontiers in Signal Processing 2024, 3, 1276748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulov, A. Physical modelling of the piano string scale. Applied Acoustics 2008, 69, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H. Physical Modeling of Piano Sound. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.03481 2024.

- Wagner, E. History of the Piano Etude. The American Music Teacher 1959, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, A. A HISTORY OF CLASS PIANO INSTRUCTION. Music Journal 1960, 18, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, M.; Robles-Linares, J.A. A Brief History of Piano Mechanics. In Proceedings of the Advances in Italian Mechanism Science: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of IFToMM Italy 3. Springer, 2021, pp. 11–19.

- Newman, W.S. A Capsule History of the Piano. The American Music Teacher 1963, 12, 14. [Google Scholar]

- HG. History of the Piano, 1948.

- Russo, M.; Robles-Linares, J.A. A Brief History of Piano Action Mechanisms. Advances in Historical Studies 2020, 9, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomes, S. The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces; Yale University Press, 2021.

- Story, B.H. An overview of the physiology, physics and modeling of the sound source for vowels. Acoustical Science and Technology 2002, 23, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, C.J.; Erickson, G.L. A study of tertiary physics students’ conceptualizations of sound. International Journal of Science Education 1989, 11, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet-Clark, H.C. Songs and the physics of sound production. Cricket behavior and neurobiology 1989, pp. 227–261.

- Josephs, J.J.; Slifkin, L. The physics of musical sound. Physics Today 1967, 20, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sataloff, J.; Sataloff, J. The Physics of Sound. 2. Hearing Loss 2005, p. 2.

- Daschewski, M.; Boehm, R.; Prager, J.; Kreutzbruck, M.; Harrer, A. Physics of thermo-acoustic sound generation. Journal of applied Physics 2013, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, E.G.; Bray, C.W. The nature of acoustic response: The relation between sound frequency and frequency of impulses in the auditory nerve. Journal of experimental psychology 1930, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinger, D.K. Feature-Map Methods for Extracting Sound Frequency Modulation. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the Twenty-Fifth Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems & Computers. IEEE Computer Society, 1991, pp. 795–796.

- Wood, J.C.; Buda, A.J.; Barry, D.T. Time-frequency transforms: a new approach to first heart sound frequency dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 1992, 39, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawk, B. Sound: Resonance as rhetorical. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 2018, 48, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flax, L.; Dragonette, L.; Überall, H. Theory of elastic resonance excitation by sound scattering. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1978, 63, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracewell, R.N. The fourier transform. Scientific American 1989, 260, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.G. Fourier acoustics: sound radiation and nearfield acoustical holography; Academic press, 1999.

- Yoganathan, A.P.; Gupta, R.; Udwadia, F.E.; Wayen Miller, J.; Corcoran, W.H.; Sarma, R.; Johnson, J.L.; Bing, R.J. Use of the fast Fourier transform for frequency analysis of the first heart sound in normal man. Medical and biological engineering 1976, 14, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikx, M.; Waxler, R.; Forssén, J. The extended Fourier pseudospectral time-domain method for atmospheric sound propagation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2010, 128, 1632–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohyama, M. Waveform Analysis of Sound; Springer, 2015.

- Westervelt, P.J. Scattering of sound by sound. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1957, 29, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean III, L.W. Interactions between sound waves. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1962, 34, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, T. Sound Analysis using STFT spectroscopy. Bachelor Thesis, University of Bremen 2011, pp. 1–47.

- Lee, J.Y. Sound and vibration signal analysis using improved short-time fourier representation. International Journal of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering 2013, 7, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).