Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the most prevalent cause of global mortality, highlight-ing the importance of understanding their molecular bases. Recently, small non-coding RNAs (miR-NAS) were shown to affect messenger RNA (mRNA) stability, either by inhibiting translation or by causing degradation through base pairing with mRNAs, being negative regulators of protein transla-tion. Moreover, miRNAs modulate many signaling pathways and cellular processes, including cell-to-cell communication. In the cardiovascular system, miRNAs control functions in cardiomyo-cytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. Because miRNA expression was detected in the blood of patients with various cardiovascular diseases, they are considered attractive candidates for noninvasive biomarkers. This study reviews the literature on the role played by miRNAs in CVDs. The findings suggest that miRNA regulation may offer new perspectives for therapeutic interventions in heart diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

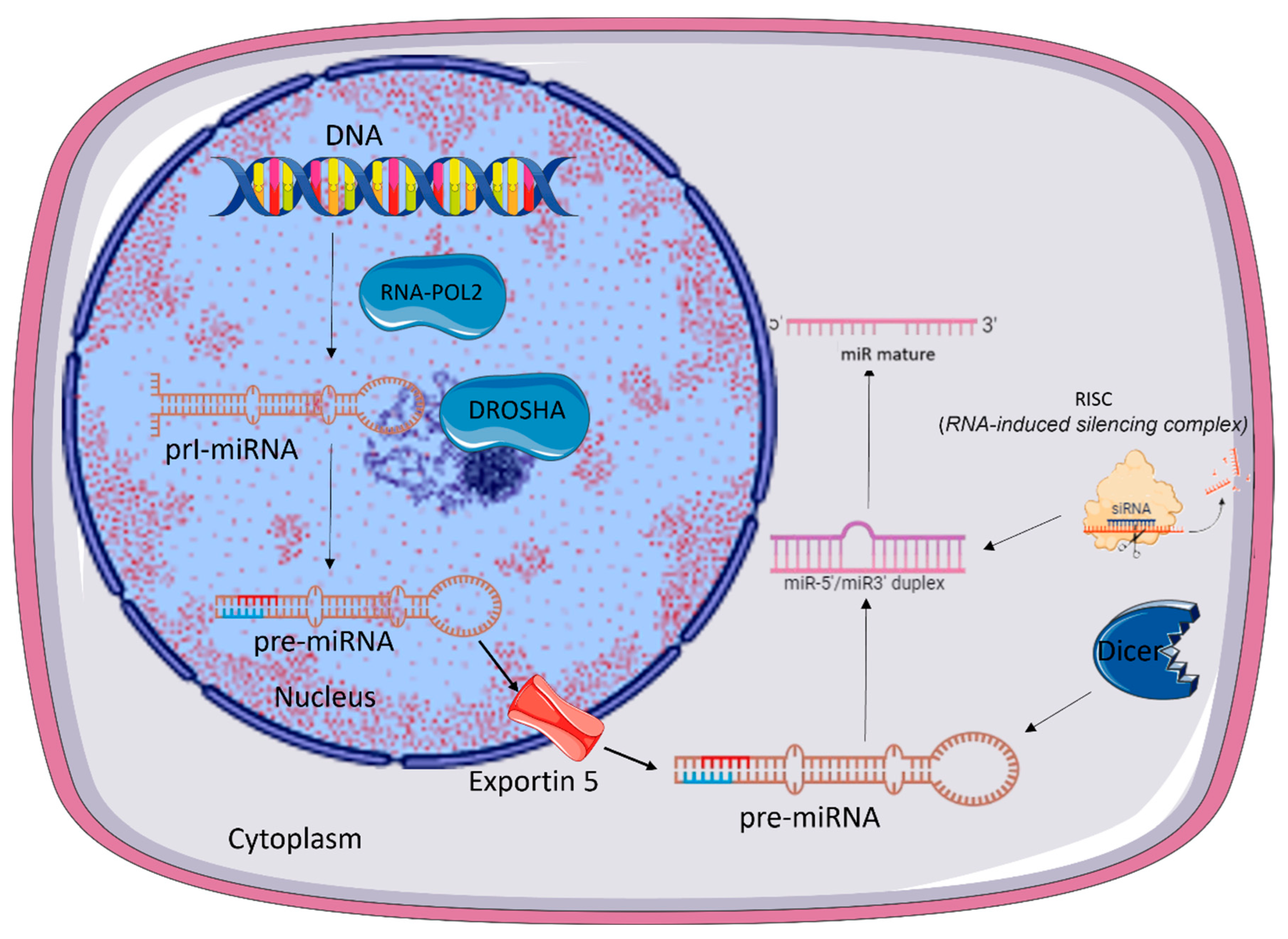

2. microRNA Biogenesis

3. MicroRNAs and Intercellular Communication

4. miRNAs in Cardiac Diseases

5. miRNA and Other Diseases

6. Methodological approaches

7. The clinical potential of miRNAs: diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic implications

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. A Heart-Healthy and Stroke-Free World: Using Data to Inform Global Action. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82 (25), 2343-2349.

- Kalayinia, S.; Arjmand, F.; Maleki, M.; Malakootian, M.; Singh, C.P. MicroRNAs: roles in cardiovascular development and disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2021, 50:107296. [CrossRef]

- Feeney, A.; Nilsson, E.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenetics and transgenerational inheritance in domesticated farm animals. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 5(1):48. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.F.P.; Planello, A.C.; Andia, D.C.; Pardo, A.P. de S. Metilação de DNA e Câncer. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2010, 56, 493-499.

- Kiefer, J.C. Epigenetics in development. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists, 2007; 236(4), 1144-1156.

- Morris, J.R. Genes, genetics, and epigenetics: a correspondence. Science, 2001, 293(5532), 1103-1105. [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.M.; Condorelli, G. Epigenetic modifications and noncoding RNAs in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Nat. Ver. Cardiol. 2015,12 (8), 488-497.

- Sen, G.L.; Blau, H.M. A brief history of RNAi: the silence of the genes. FASEB. J. 2016, 20:1293–1299. [CrossRef]

- Setten, R.L.; Rossi, J.J.; Han, S.P. The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2019, 18:421–446. [CrossRef]

- Quiat, D.; Olson, E.N. MicroRNAs in cardiovascular disease: from pathogenesis to prevention and treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 2013,123 (1),11-18. [CrossRef]

- Thum, T. Noncoding RNAs and myocardial fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014, 11(11), 655-663. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, A. dbDEMC 2.0: updated database of differentially expressed miRNAs in human cancers. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2017 45, 812-D818. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.X.; Rothenberg, M.E. MicroRNA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141 (4), 1202-1207.

- Mori, M.A.; Ludwig R.G.; Garcia-Martin R.; Brandão B.B.; Kahn C.R. Extracellular miRNAs: From Biomarkers to Mediators of Physiology and Disease. Cell. Metab. 2019, 30 (4), 656-673. [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, J.D.; Wei, Y.; Khavari, P.A. The functions and unique features of long intergenic non-coding RNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018,19 (3),143-157. [CrossRef]

- Ulitsky, I. Interactions between short and long noncoding RNAs. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592 (17), 2874-2883. [CrossRef]

- Gebert, L.F.R., MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2019, 20 (1), 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Tran, N. miRNA interplay: mechanisms and consequences in cancer. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021,14 (4). [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.X.; Rothenberg, M.E. MicroRNA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141 (4), 1202-1207.

- Citron, F.; Armenia, J.; Franchin, G. An Integrated Approach Identifies Mediators of Local Recurrence in Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23 (14): 3769-3780.

- Yoon, A.J.; Wang, S.; Kutler, D.I.; et al. MicroRNA-based risk scoring system to identify early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma patients at high-risk for cancer-specific mortality. Head Neck. 2020, 42(8),1699-1712.

- Wojciechowska, A.; Braniewska, A.; Kozar-Kamińska, K. MicroRNA in cardiovascular biology and disease. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26 (5), 865-874.

- Zernecke, A.; Bidzhekov, K.; Noels, H.; et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2(100), ra81.

- Hata, A. Functions of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology and disease. Annu. Ver. Physiol. 2013, 75, 69-93.

- Condorelli, G.; Latronico, M.V.; Cavarretta, E. microRNAs in cardiovascular diseases: current knowledge and the road ahead. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63(21), 2177-2187.

- Bronze-da-Rocha, E. MicroRNAs expression profiles in cardiovascular diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 985408.

- Klimczak, D.; Pączek, L.; Jażdżewski, K.; Kuch, M. MicroRNAs: powerful regulators and potential diagnostic tools in cardiovascular disease. Kardiol. Pol. 2015, 73 (1), 1-6.

- Anglicheau, D.; Muthukumar, T.; Suthanthiran, M. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with big effects. Transplantation 2010, 90 (2),105-112.

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Yalcin, A.; Meyer J.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12 (9), 735-739.

- Ludwig, N.; Leidinger, P.; Becker K.; et al. Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44 (8), 3865-3877. [CrossRef]

- Nalbant, E.; Akkaya-Ulum, Y.Z. Exploring regulatory mechanisms on miRNAs and their implications in inflammation-related diseases. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24 (1), 142.

- Ha, M.; Kim.; V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 15:509–524. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Tsai, Y.M.; Lien, C.T.; Kuo, P.L.; Hung, A.J. The Roles of MicroRNA in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (7), 1611. [CrossRef]

- Valinezhad, O.A; Safaralizadeh, R.; Kazemzadeh-Bavili, M. Mechanisms of miRNA-mediated gene regulation from common downregulation to mRNA- specific upregulation. Int. J. Genomics. 2014, 2014:970607.

- Liu, B.; Shyr, Y.; Cai, J.; Liu, Q. Interplay between miRNAs and host genes and their role in cancer. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 2018, 18:255–266.

- Matsumoto. J; Stewart, T.; Banks, W.A.; Zhang, J. The Transport Mechanism of Extracellular Vesicles at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23(40), 6206-6214. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.; Caudy, A.A.; Hammond, S.M.; Hannon, G.J. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 2001, 409 (6818), 363-366.

- Song, J.J.; Liu, J.; Tolia, N.H.; et al. The crystal structure of the Argonaute2 PAZ domain reveals an RNA binding motif in RNAi effector complexes. Na.t Struct. Biol. 2003, 10 (12), 1026-1032.

- Schwarz, D.S.; Hutvágner, G.; Du, T.; Xu, Z.; Aronin, N; Zamore, P.D. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell 2003, 115 (2), 199-208.

- Wu, K.L.; Tsai, Y.M.; Lien, C.T.; Kuo, P.L.; Hung, A.J. The Roles of MicroRNA in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (7), 1611.

- Khvorova. A.; Reynolds. A.; Jayasena. S.D. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003, 115 209–16.

- Ha. M.; Kim. V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 15 509–24.

- O'Brien. J.; Hayder. H.; Zayed. Y. Peng. C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 3 9:402.

- Isik, M.; Korswagen, H.C.; Berezikov, E. Expression patterns of intronic microRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Silence 2010, 1 (1), 5.

- Westholm, J.O.; Lai, E.C. Mirtrons: microRNA biogenesis via splicing. Biochimie 2011, 93 (11), 1897-1904.

- Ramalingam, P.; Palanichamy, J.K.; Singh, A.; et al. Biogenesis of intronic miRNAs located in clusters by independent transcription and alternative splicing. RNA. 2014, 20 (1), 76-87.

- Yang. J.S.; Maurin. T.; Robine. N.; Rasmussen. K.D.; Jeffrey. K.L.; Chandwani. R. Conserved vertebrate mir-451 provides a platform for Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010, 107 15163–8.

- Cheloufi. S.; Dos Santos. C.O.; Chong. M.M.W.; Hannon. G.J. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 2010, 465 584–9.

- Weber, J.A.; Baxter, D.H.; Zhang, S.; et al. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem. 2010, 56(11), 1733-1741.

- Arroyo, J.D.; Chevillet, J.R.; Kroh, E.M.; et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011, 108 (12), 5003-5008. [CrossRef]

- Weickmann, J.L.; Glitz, D.G. Human ribonucleases. Quantitation of pancreatic-like enzymes in serum, urine, and organ preparations. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257 (15), 8705-8710.

- Théry, C. Exosomes: secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2011, 3: 15.

- Théry, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Amigorena, S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat. Ver. Immunol. 2002, 2 (8), 569-579.

- Tsui. N.B.; Ng E.K.; Lo. Y.M.; Stability of endogenous and added RNA in blood specimens, serum, and plasma. Clin. Chem. 2002.

- 55. Wang. K.; Zhang. S.; Marzolf. B.; Troisch. P.; Brightman. A.; Hu. Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009, 106 4402–7. [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand. M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9 (6), 654-659.

- Morello, M.; Minciacchi, V.R.; de Candia, P.; et al. Large oncosomes mediate intercellular transfer of functional microRNA. Cell Cycle. 2013, 12 (22), 3526-3536.

- Castaño. C.; Kalko. S.; Novials. A.; Parrizas. M. Obesity-associated exosomal miRNAs modulate glucose and lipid metabolism in mice. PNAS. 2018, 15 12158-12163.

- Guay, C.; Kruit, J.K.; Rome, S.; et al. Lymphocyte-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Promote Pancreatic β Cell Death and May Contribute to Type 1 Diabetes Development. Cell Metab. 2019, 29 (2), 348-361.e6.

- Can, U.; Buyukinan, M.; Yerlikaya, F.H. The investigation of circulating microRNAs associated with lipid metabolism in childhood obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2016, 11 (3), 228-234.

- Jones, A.; Danielson, K.M.; Benton, M.C.; et al. miRNA Signatures of Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017, 25 (10), 1734-1744.

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Ver. Neurol. 2018, 14 (3), 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Liu, L.; Ma, F.; et al. Elucidation of Exosome Migration across the Blood-Brain Barrier Model In Vitro. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2016, 9 (4), 509-529. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qian, H.; Xue, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H. MicroRNA-152 regulates insulin secretion and pancreatic β cell proliferation by targeting PI3Kα. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18 (4), 4113-4121.

- Martins-Marques, T.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Leybaert, L.; Girao, H. Intercellular Communication in the Heart: Therapeutic Opportunities for Cardiac Ischemia. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27 (3), 248-262.

- Ribeiro-Rodrigues, T.M.; Laundos, T.L.; Pereira-Carvalho, R; et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiomyocytes subjected to ischemia promote cardiac angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113 (11), 1338-1350.

- Bao. M.; H., Feng. X.; Zhang. Y. W.; Lou. X. Y.; Cheng. Y. U.; Zhou. H. H. Let-7 in cardiovascular diseases, heart development and cardiovascular differentiation from stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14(11), 23086-23102.

- Fichtlscherer, S.; De Rosa, S.; Fox, H.; et al. Circulating microRNAs in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ. Res. 2010, 107: 677-684.

- Small, E. M.; Frost, R. J.; Olson, E. N. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010, 121:1022-1032. [CrossRef]

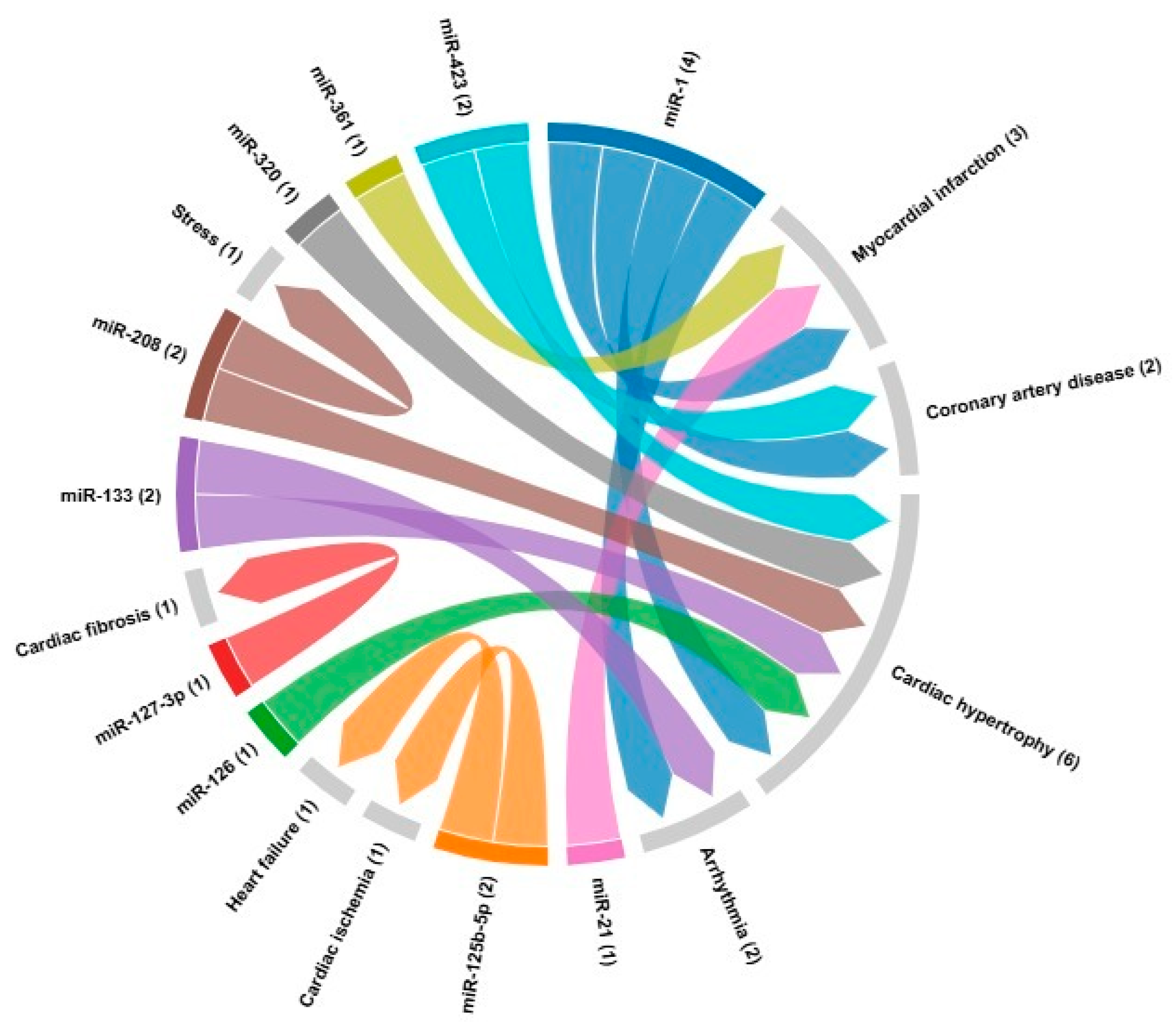

- Mauri, M.; Elli, T.; Caviglia, G.; Uboldi, G.; Azzi, M. RAWGraphs: A Visualisation Platform to Create Open Outputs. In Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI. 2017, p. 28:1–28:5.

- Lee. R.C.; Feinbaum. R.L.; Ambros. V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993, 75 843–854.

- Reinhart. B.J.; Slack. F.J.; Basson. M.; Pasquinelli. A.E.; Bettinger. J.C.; Rougvie. A.E.; Horvitz. H.R.; Ruvkun. G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegan s. Nature. 2000, 403 901–906.

- Ding. Z.; Wang. X.; Schnackenberg. L.; Khaidakov. M.; Liu. S.; Singla. S.; Dai. Y.; Mehta. J.L. Regulation of autophagy and apoptosis in response to ox-LDL in vascular smooth muscle cells, and the modulatory effects of the microRNA hsa-let-7g. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013.

- Chen. Z.; Lai. T.C.; Jan. Y.H.; Lin. F.M.; Wang. W.C.; Xiao. H.; Wang. Y.T.; Sun. W.; Cui. X.; Li. Y.S. Hypoxia-responsive miRNAs target argonaute 1 to promote angiogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013 123 1057–1067.

- Mamoru. S.; Yoshitaka. M.; Yuji. T.; Tsuyoshi. T.; Motoyuki. N. A cellular microRNA, let-7i, is a novel biomarker for clinical outcome in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17 923–929.

- Rao. P.K.; Toyama. T.; Chiang. H.R.; Gupta. S.; Bauer. M.; Medvid. R.; Reinhardt. F.; Liao. R.; Krieger. M.; Jaenisch. R. Loss of cardiac microRNA-mediated regulation leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2009, 105 585–594.

- Ji. R.; Cheng. Y.; Yue. J.; Yang. J.; Liu. X.; Chen. H.; Dean. D.B.; Zhang. C. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of microRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ. Res. 2007, 100 1579–1588.

- Topkara, V.K.; Mann, D.L. Role of microRNAs in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Drug Ther 2011, 25, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Rao. P.K.; Toyama. T.; Chiang. H.R.; Gupta. S.; Bauer. M.; Medvid. R.; Reinhardt. F.; Liao. R.; Krieger. M.; Jaenisch. R. Loss of cardiac microRNA-mediated regulation leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2009, 105 585–594.

- Jayawardena. E.; Medzikovic. L.; Ruffenach. G. Role of miRNA-1 and miRNA-21 in acute myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and their potential as therapeutic strategy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 1512.

- Yu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. An integrated hypothesis for miR-126 in vascular disease. Medical research archives, 2020, 8(5), 2133.

- Gonzalez-Lopez. P.; Alvarez-Villarreal. M.; Ruiz-Simon. R. Role of miR-15a-5p and miR-199a-3p in the inflammatory path- way regulated by NF-jB in experimental and human atherosclerosis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023 13 1363.

- Surina, S.; Fontanella, R.A.; Scisciola, L.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G.; Barbieri, M.; miR-21 in Human Cardiomyopathies [published correction appears in Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022 25 9:913429.

- Ramanujam, D.; Schön, A.P.; Beck, C. et al. MicroRNA-21-dependent macrophage-to-fibroblast signaling determines thecardiac response to pressure overload. Circulation, 2021, 143: 1513-1525.

- Krichevsky. A. M.; Gabriely. G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13 39-53.

- Li, N.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Q. MiR-133: a suppressor of cardiac remodeling? Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2018, 9, 903.

- Çakmak. H. A.; Demir. M. MicroRNA and cardiovascular diseases. Balkan medical journal, 2020, 37(2), 60.

- Li. J.; Li. L.; Li. X.; Wu. S. Long noncoding RNA LINC00339 aggravates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting MiR-484. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2018. 503(4), 3038-3043.

- Wang. K., Liu. C. Y., Zhang. X. J., Feng. C., Zhou. L. Y., Zhao. Y.; Li. P. F. miR-361-regulated prohibitin inhibits mitochondrial fission and apoptosis and protects heart from ischemia injury. Cell death and differentiation, 2015, 22(6), 1058–1068.

- Bayoumi. A. S.; Park, K. M.; Wang. Y.; Teoh. J. P.; Aonuma. T.; Tang. Y.; Kim. I. M. A carvedilol-responsive microRNA, miR-125b-5p protects the heart from acute myocardial infarction by repressing pro-apoptotic bak1 and klf13 in cardiomyocytes. JMCC. 2018, 114 72-82.

- Zhou. Q.; Liu. Z.; Bei. Y.; Zhang. Z.; L. Xiao. J. P4751 Suppression of miR-127-3p prevents cardiac fibrosis. Eur. Heart J., 2018. 39, 563-P4751.

- Zhao. X.; Wang. Y.; Sun. X. The functions of microRNA-208 in the heart. Diabetes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 160:108004.

- Callis. T. E.; Pandya. K.; Seok. H. Y.; Tang. R. H.; Tatsuguchi. M.; Huang. Z. P.; Chen. J. F.; Deng. Z.; Gunn. B.; Shumate. J.; Willis. M. S.; Selzman. C. H.; Wang. D. Z. MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2009, 119(9), 2772–2786.

- Ho, P.T.B.; Clark, I.M.; Le, L.T.T. MicroRNA-Based Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (13), 7167.

- Correia de Sousa. M.; Gjorgjieva. M.; Dolicka. D.; Sobolewski. C.; Foti. M. Deciphering miRNAs' Action through miRNA Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20(24), 6249.

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Jia, B.; et al. Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs [published correction appears in Nature. 2018 Aug, 560 (7719):E33.

- Zagrean, A.M.; Hermann, D.M.; Opris, I.; Zagrean, L.; Popa-Wagner, A. Multicellular Crosstalk Between Exosomes and the Neurovascular Unit After Cerebral Ischemia. Therapeutic Implications. Fron.t Neurosci. 2018, 12:811.

- Huang, S.; Ge, X.; Yu, J.; et al. Increased miR-124-3p in microglial exosomes following traumatic brain injury inhibits neuronal inflammation and contributes to neurite outgrowth via their transfer into neurons [published correction appears in FASEB J. 2018 Apr, 32 (4):2315.

- Chen, P.S.; Su, J.L.; Cha, S.T.; et al. miR-107 promotes tumor progression by targeting the let-7 microRNA in mice and humans [published correction appears in J Clin Invest. 2017 Mar 1, 127 (3), 1116. doi: 10.1172/JCI92099]. .J Clin. Invest. 2011, 121 (9), 3442-3455.

- Forrest, A.R.; Kanamori-Katayama, M.; Tomaru, Y.; et al. Induction of microRNAs, mir-155, mir-222, mir-424 and mir-503, promotes monocytic differentiation through combinatorial regulation. Leukemia. 2010, 24 (2), 460-466. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Tran, N. MicroRNAs Regulating MicroRNAs in Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2018, 4 (7), 465-468.

- Levine, G.N. Psychological Stress and Heart Disease: Fact or Folklore? Am. J. Med. 2022, 135 (6), 688-696.

- Ortolani, D.; Oyama, L. M.; Ferrari, E. M.; Melo, L. L., Spadari-Bratfisch, R. C. Effects of comfort food on food intake, anxiety-like behavior and the stress response in rats. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 103(5), 487-492.

- Ortolani, D.; Garcia, M.C.; Melo-Thomas, L.; Spadari-Bratfisch, R.C. Stress-induced endocrine response and anxiety: the effects of comfort food in rats. Stress. 2014, 17(3):211-218.

- Spadari-Bratfisch, R. C.; dos Santos, I. N. Adrenoceptors and adaptive mechanisms in the heart during stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2008 1148, 377–383.

- Moura, A. L. D.; Hyslop, S.; Grassi-Kassisse, D. M.; Spadari, R. C. Functional β2-adrenoceptors in rat left atria: effect of foot-shock stress. CJPP, 2017, 95(9), 999-1008.

- Cordeiro, M.A.; Rodrigues, L.S.; Ortolani, D.; de Carvalho, A.E.T.; Spadari, R.C. Persistent Effects of Subchronic Stress on Components of Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in the Heart. J. Clin. Exp. Cardiolog. 2020, 11:676.

- Moura, A.L.; Brum, P.C.; de Carvalho, A.E.T.S.; Spadari, R.C. Effect of stress on the chronotropic and inotropic responses to β-adrenergic agonists in isolated atria of KOβ2 mice. Life Science. 2023, 322: 121644.

- Rodrigues, L.S.M.; Cordeiro, M.A.; de Carvalho, A.E.T.S.; Caceres, M.V.; Spadari, R.C.; Stress induced cardiac dysfunction in rats, unpublished.

- de Carvalho, A.E.T.S.; Cordeiro, M.A.; Rodrigues, L.S.; Ortolani, D.; Spadari, R.C. Stress-induced differential gene expression in cardiac tissue. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11: 9129.

- Johnson. A.M.F.; Olefsky. J.M. The origins and drivers of insulin resistance. Cell. 2013, 152: 673–684.

- Baker. M. MicroRNA profiling: separating signal from noise. Nat. Methods. 2010, 7: 687–692.

- van Rooij, E. The art of microRNA research. Circ. Res. 2011, 108: 219-234.

- Creemers, E. E.; Tijsen, A. J.; Pinto, Y. M. Circulating microRNAs: novel biomarkers and extracellularcommunicators in cardiovascular disease? Circ. Res. 2012, 110: 483-495.

- Dzikiewicz-Krawczyk, A. MicroRNA polymorphisms as markers of risk, prognosis and treatment response in hematological malignancies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2015, 93: 1-17.

- Etheridge A, Lee I, Hood L, Galas D, Wang K. Extracellular microRNA: A new source of biomarkers. Mutat. Res. 2011, 717: 85–90.

- Park, N. J.; Zhou, H.; Elashoff, D.; Henson, B. S.; Kastratovic, D.A.; Abemayor, E.; et al. Salivary microRNA: Discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15: 5473–5477.

- Michael, A.; Bajracharya, S. D.; Yuen, P. S.; Zhou, H.; Star, R. A.; Illei, G. G.; et al. Exosomes from human saliva as a source of microRNA biomarkers. Oral Dis. 2010, 16: 34–38.

- Small, E. M.; Frost, R. J.; Olson, E. N. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010, 121:1022-1032.

- Corsten, M. F.; Dennert, R.; Jochems, S.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA-208b and MicroRNA-499 reflect myocardial damage in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2010, 3: 499-506.

- Gomes da Silva, A. M.; Silbiger, V. N. miRNAs as biomarkers of atrial fibrillation. Biomarkers 2014, 19: 631-636.trial fibrillation. Biomarkers 2014, 19: 631-636.

- Kalayinia. S.; Arjmand. F.; Maleki. M.; Malakootian. M.; Singh. C. P. MicroRNAs: roles in cardiovascular development and disease. Cardiovascular pathology: the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology, 2021, 50, 107296.

| microRNA | Cardiovascular disease | Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | Myocardial infarction Coronary artery disease Cardiac hypertrophy Arrhythmia |

GJA1, KCNJ2, HAND2, IRX5, HSP70, HSP60, HDAC4, CDK9, KCNE1, RASGAP, RHEB, NPTB, biomarker | [24,121] |

| miR-21 | Myocardial infarction | Biomarker | [24] |

| miR-133 | ArrhythmiasCardiac hypertrophy | GJA1, KCNJ2, AKT/mTOR | [20,82] |

| miR-361 | Myocardial infarction | PHB1 | [85] |

| miR-125b-5p | Cardiac ischemia Heart failure |

Biomarker, bak1 and klf13 | [86] |

| miR-127-3p | Cardiac fibrosis | TGF-β, Ang II | [87] |

| miR-208 | Cardiac fibrosis Cardiac hypertrophy Stress |

THRAP-1, Mef2, SOX6, βMHC, αMHC | [88] |

| miR-320 | Cardiac hypertrophy | Biomarker | [24] |

| miR-423 | Coronary artery disease Cardiac hypertrophy |

Biomarker | [24] |

| miR-126 | Cardiac hypertrophy | Biomarker | [24] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).