Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

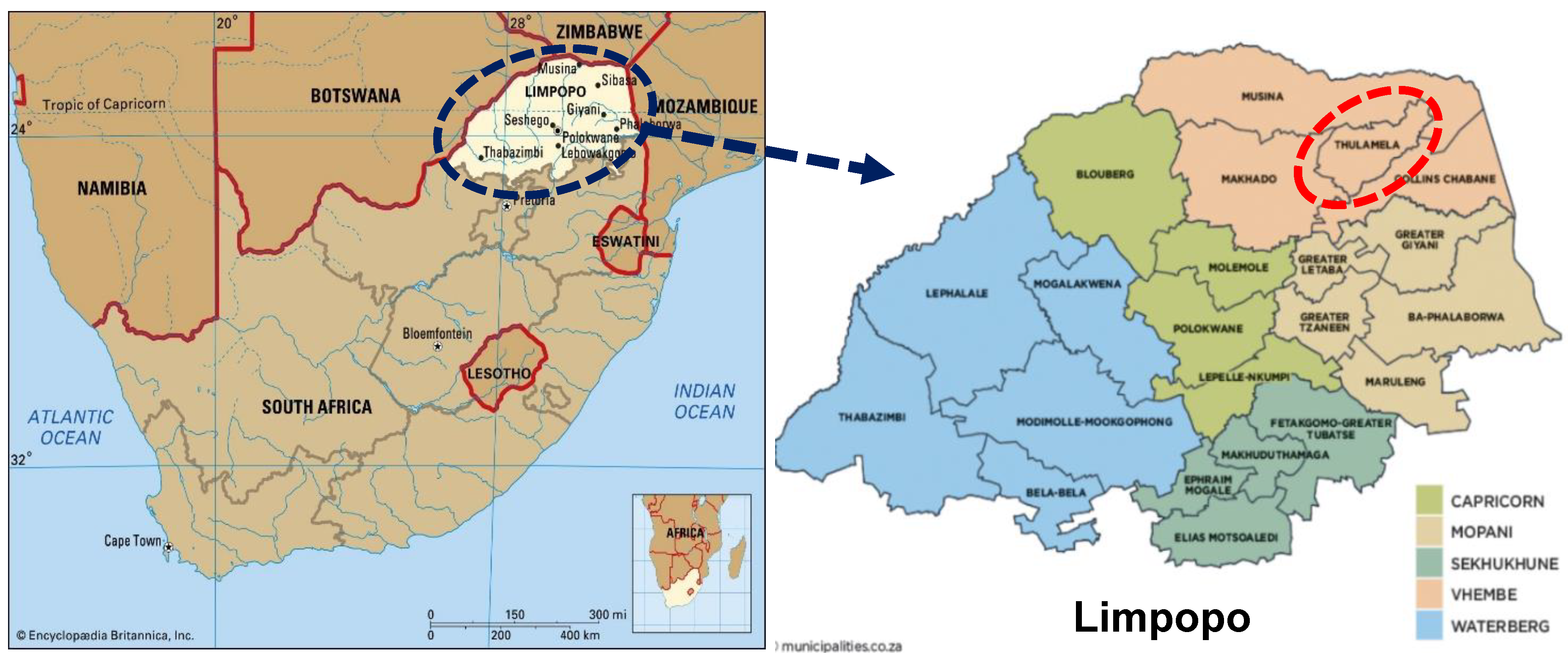

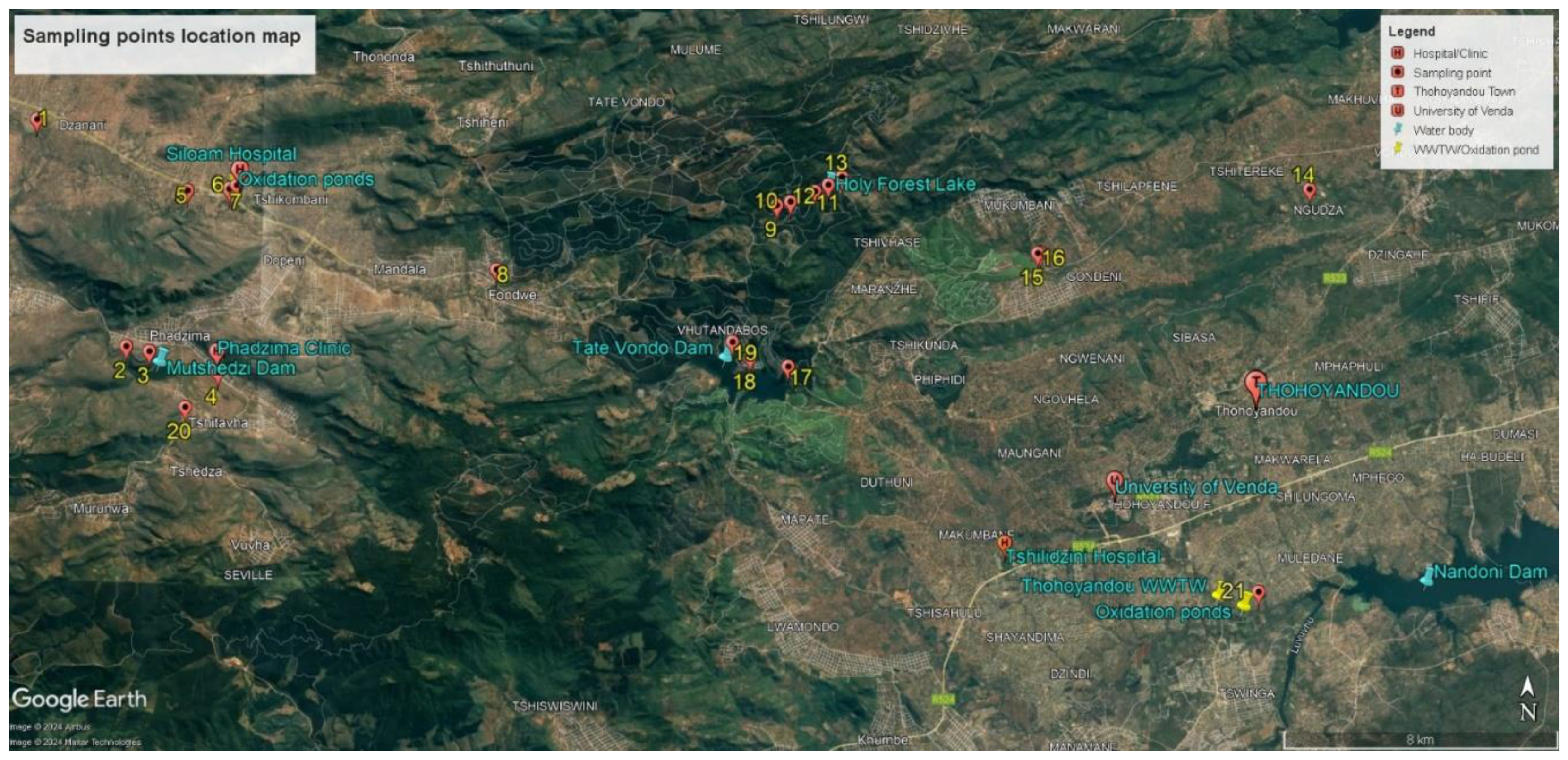

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Sites

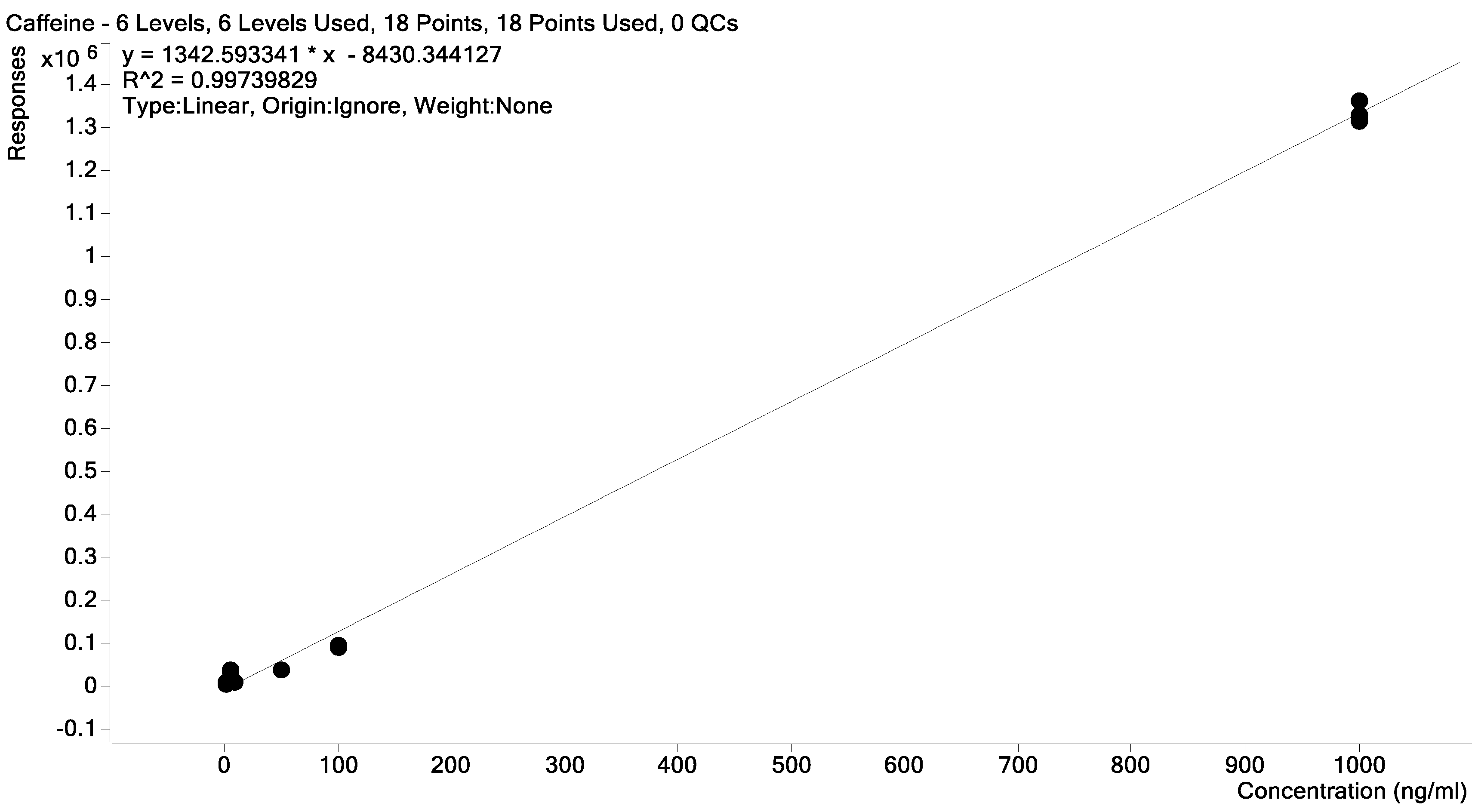

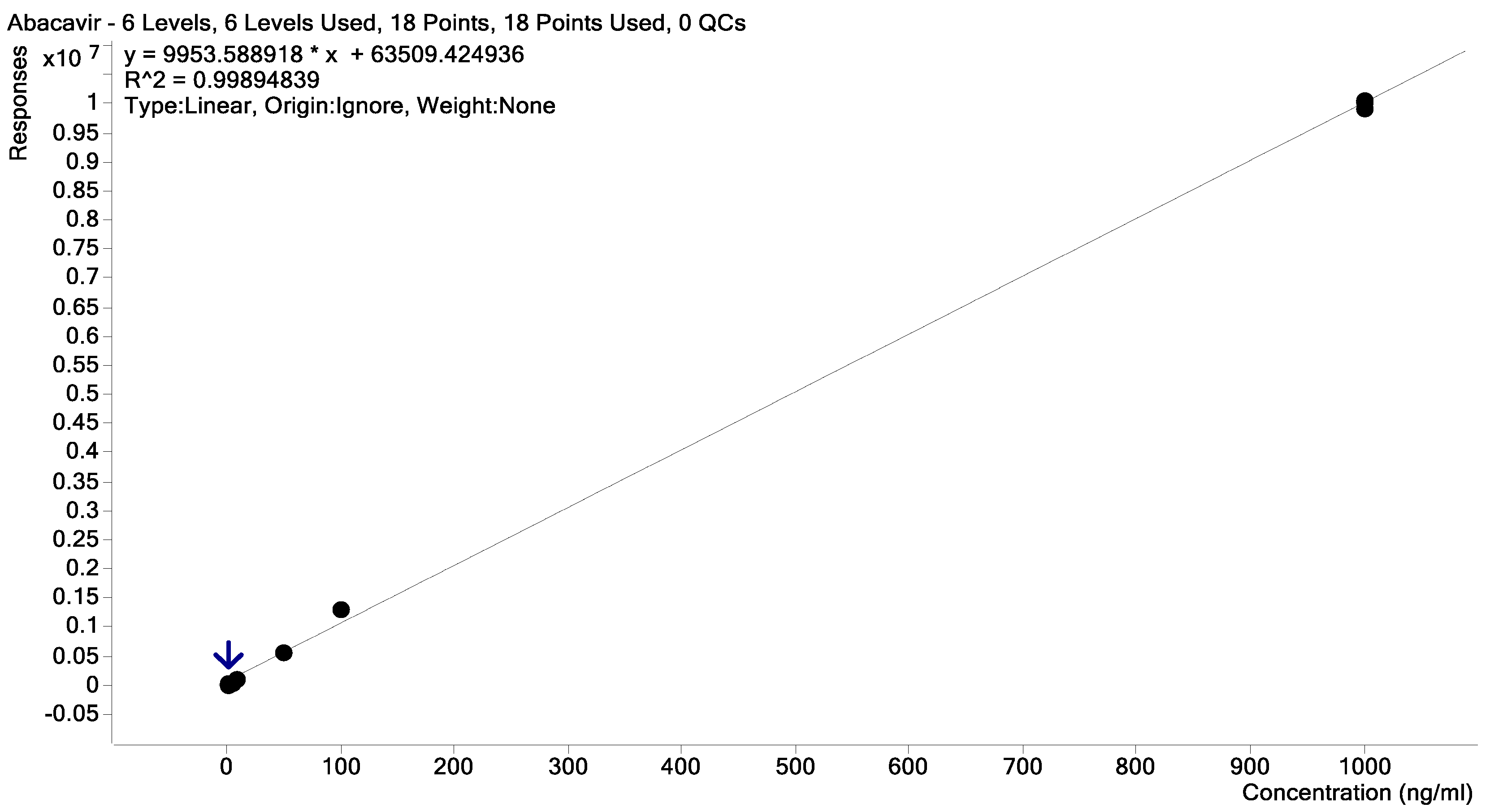

2.2. Samples Collection, Extraction, and Quantification

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Compound name |

|---|

| 1. Lamivudine |

| 2. Method pyrazinamide |

| 3. Chlorothiazide |

| 4. Theophylline |

| 5. Chloroquine phosphate |

| 6. Azathioprine |

| 7. Methotrexate |

| 8. Amoxicillin |

| 9. Metoprolol |

| 10. Tartrate |

| 11. Methocarbamol |

| 12. Methylparaben (Methyl parahydroxybenzoate) |

| 13. Erythromycin |

| 14. Prednisone |

| 15. Benzylpenicillin |

| 16. Fluoxetine |

| 17. Hydrochloride |

| 18. Ketoprofen |

| 19. Valsartan |

| 20. Cholecalciferol |

| 21. Taurine |

| 22. Zalcitabine |

| 23. Emtricitabine |

| 24. Famotidine |

| 25. Abacavir |

| 26. Cyclosporin A |

| 27. Cefotaxime |

| 28. Oseltamivir |

| 29. Chloramphenicol |

| 30. Diphenhydramine |

| 31. Hydrochloride |

| 32. Chlorhexidine |

| 33. Prednisolone |

| 34. Clarithromycin |

| 35. Cloxacillin |

| 36. Naproxen |

| 37. Diclofenac sodium salt |

| 38. Lovastatin |

| 39. Metformin |

| 40. Hydrochloride |

| 41. Tenofovir |

| 42. Ethionamide |

| 43. Hydrochlorothiazide |

| 44. Lidocaine |

| 45. Doxycycline hyclate |

| 46. Lamotrigine |

| 47. Guaifenesin |

| 48. Azithromycin |

| 49. Labetalol |

| 50. Hydrochloride |

| 51. Dextromethorphan hydrobromide monohydrate |

| 52. Indinavir |

| 53. Lansoprazole |

| 54. Ketoconazole |

| 55. Clotrimazole |

| 56. Praziquantel |

| 57. Gemfibrozil |

| 58. Isoniazid |

| 59. Metronidazole |

| 60. Cimetidine |

| 61. Ranitidine |

| 62. Hydrochloride |

| 63. Didanosine |

| 64. Stavudine |

| 65. Trimethoprim |

| 66. Ofloxacin |

| 67. Metoclopramide |

| 68. Hydrochloride |

| 69. Chlorpheniramine maleate |

| 70. Omeprazole |

| 71. Nevirapine |

| 72. Enalapril |

| 73. Maleate |

| 74. Carvedilol |

| 75. Tetracycline |

| 76. Hydrochloride |

| 77. Loperamide |

| 78. Rifampicin |

| 79. Lopinavir |

| 80. Gentamicin |

| 81. Ethambutol |

| 82. Acyclovir |

| 83. Acetaminophen |

| 84. Gabapentin |

| 85. Zidovudine |

| 86. Aspartame |

| 87. Fluconazole |

| 88. Sulfamethoxazole |

| 89. Clindamycin |

| 90. Hydrocortisone |

| 91. Carbamazepine |

| 92. Loratadine |

| 93. Chlorpropamide |

| 94. Flucloxacillin |

| 95. Indomethacin |

| 96. Atorvastatin |

| 97. Ritonavir |

| 98. Efavirenz |

| 99. Caffeine |

References

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) Statistical Release P0302: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2022. Department: Statistics South Africa 2022; https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022022.pdf (accessed September 30, 2024).

- UNAIDS (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) UNAIDS Data 2022. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/2022_unaids_data (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs PROFILE: VHEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 2; 2020; https://www.cogta.gov.za/ddm/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/vhembeoctober-2020.pdf.

- Simbayi, L.C.; Zuma, K.; Zungu, N.; et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2017. Available online: https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/13760 (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Venter, W.D.F.; Kaiser, B.; Pillay, Y.; Conradie, F.; Gomez, G.B.; Clayden, P.; Matsolo, M.; Amole, C.; Rutter, L.; Abdullah, F.; et al. Cutting the Cost of South African Antiretroviral Therapy Using Newer, Safer Drugs. South African Medical Journal 2016, 107, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. World Health Organization 2021, 592.

- Agunbiade, F.O.; Moodley, B. Pharmaceuticals as Emerging Organic Contaminants in Umgeni River Water System, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Environ Monit Assess 2014, 186, 7273–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matongo, S.; Birungi, G.; Moodley, B.; Ndungu, P. Pharmaceutical Residues in Water and Sediment of Msunduzi River, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Chemosphere 2015, 134, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matongo, S.; Birungi, G.; Moodley, B.; Ndungu, P. Occurrence of Selected Pharmaceuticals in Water and Sediment of Umgeni River, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22, 10298–10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, C.; Mashiane, M.; Dlamini, M.; Okonkwo, O. Quantification of Selected Antiretroviral Drugs in a Wastewater Treatment Works in South Africa Using GC-TOFMS. J. Chromatogr. Sep. Tech. 2015, 6, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.P.; Duvenage, C.S.J.; Rohwer, E. The Occurrence of Anti-Retroviral Compounds Used for HIV Treatment in South African Surface Water. Environ Pollut 2015, 199, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vumazonke, S.; Khamanga, S.M.; Ngqwala, N.P. Detection of Pharmaceutical Residues in Surface Waters of the Eastern Cape Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 4067 2020, 17, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Holton, E.; Fidal, J.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Carstens, A.; Brocker, L.; Kjeldsen, T.R.; Wolfaardt, G.M. Occurrence of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the Eerste River, South Africa: Towards the Optimisation of an Urban Water Profiling Approach for Public- and Ecological Health Risk Characterisation. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 859, 160254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, L.; Barnhoorn, I.E.J.; Wagenaar, G.M. The Potential Effects of Efavirenz on Oreochromis Mossambicus after Acute Exposure. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2017, 56, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations The Future Is Now: Science for Achieving Sustainable Development (GSDR 2019) | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/future-now-science-achieving-sustainable-development-gsdr-2019-24576 (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Wood, T.P.; Basson, A.E.; Duvenage, C.; Rohwer, E.R. The Chlorination Behaviour and Environmental Fate of the Antiretroviral Drug Nevirapine in South African Surface Water. Water Res 2016, 104, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Petrie, B.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Wolfaardt, G.M. The Fate of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs), Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants (EDCs), Metabolites and Illicit Drugs in a WWTW and Environmental Waters. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Vogt, T.; Gerber, E.; Vogt, B.; Bouwman, H.; Pieters, R. HIV-Antiretrovirals in River Water from Gauteng, South Africa: Mixed Messages of Wastewater Inflows as Source. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 806, 150346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O.; Popoola, O.E.; Msagati, T.A.M. Assessment of Trace Metals Contamination of Surface Water and Sediment: A Case Study of Mvudi River, South Africa. Sustainability 2016, Vol. 8, Page 135 2016, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibamureke, U.M.C.; Barnhoorn, I.E.J.; Wagenaar, G.M. Health Assessment of Freshwater Fish Species from Albasini Dam, Outside a DDT-Sprayed Area in Limpopo Province, South Africa: A Preliminary Study. Afr J Aquat Sci 2016, 41, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshoka, M.F.; van Zijl, M.C.; Aneck-Hahn, N.H.; Barnhoorn, I.E.J. Endocrine-Disrupting Activity of the Fungicide Mancozeb Used in the Vhembe District of South Africa. Afr J Aquat Sci 2021, 46, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.P.; Du Preez, C.; Steenkamp, A.; Duvenage, C.; Rohwer, E.R. Database-Driven Screening of South African Surface Water and the Targeted Detection of Pharmaceuticals Using Liquid Chromatography - High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environmental Pollution 2017, 230, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimayi, C.; Chimuka, L.; Gravell, A.; Fones, G.R.; Mills, G.A. Use of the Chemcatcher® Passive Sampler and Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry to Screen for Emerging Pollutants in Rivers in Gauteng Province of South Africa. Environ Monit Assess 2019, 191, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madikizela, L.M.; Ncube, S.; Chimuka, L. Analysis, Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceuticals in African Water Resources: A Current Status. J Environ Manage 2020, 253, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) Water and Sanitation on Growing Economy in Limpopo | South African Government. Available online: https://www.gov.za/news/media-statements/water-and-sanitation-growing-economy-limpopo-14-mar-2022 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O.; Popoola, O.E.; Msagati, T.A.M. Evaluation of Contaminants Removal by Waste Stabilization Ponds: A Case Study of Siloam WSPs in Vhembe District, South Africa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibamureke, U.M.C.; Wagenaar, G.M. Histopathological Changes in Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters, 1852) Ovaries after a Chronic Exposure to a Mixture of the HIV Drug Nevirapine and the Antibiotics Sulfamethoxazole and Trimethoprim. Chemosphere 2021, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibamureke, U.M.C.; Barnhoorn, I.E.J.; Wagenaar, G.M. Nevirapine in African Surface Waters Induces Liver Histopathology in Oreochromis Mossambicus: A Laboratory Exposure Study. Afr J Aquat Sci 2019, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouché, P.; Vlok, W.; Roos, J.; Luus-Powell, W.; Jooste, A. Establishing the Fishery Potential of Lake Nandoni in the Luvuvhu River, Limpopo Province Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION; 2013.

- Traoré, A.N.; Mulaudzi, K.; Chari, G.J.E.; Foord, S.H.; Mudau, L.S.; Barnard, T.G.; Potgieter, N. The Impact of Human Activities on Microbial Quality of Rivers in the Vhembe District, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Wolfaardt, G.M.; van Wyk, J.H. Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) as Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants (EDCs) in South African Surface Waters. Water SA 2017, 43, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowlaser, S.; Barnhoorn, I.; Wagenaar, I. Developmental Abnormalities and Growth Patterns in Juvenile Oreochromis Mossambicus Chronically Exposed to Efavirenz. Emerg Contam 2022, 8, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization) HIV Treatment and Care: WHO HIV Policy Adoption and Implementation Status in Countries: Factsheet. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326035 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Jeannot, R.; Sabik, H.; Sauvard, E.; Dagnac, T.; Dohrendorf, K. Determination of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds in Environmental Samples Using Gas and Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2002, 974, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Thurman, E.M. Analysis of 100 Pharmaceuticals and Their Degradates in Water Samples by Liquid Chromatography/Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2012, 1259, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia Britannica Limpopo | Wildlife, Parks & Nature Reserves | Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Limpopo (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- The Local Government Handbook: South Africa Municipalities of South Africa: Limpopo Municipalities. Available online: https://municipalities.co.za/provinces/view/5/limpopo (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Styszko, K.; Proctor, K.; Castrignanò, E.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Occurrence of Pharmaceutical Residues, Personal Care Products, Lifestyle Chemicals, Illicit Drugs and Metabolites in Wastewater and Receiving Surface Waters of Krakow Agglomeration in South Poland. Sci Total Environ 2021, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiani, B.; Zhu, L.; Musch, B.L.; Briceno, S.; Andel, R.; Sadeq, N.; Ansari, A.Z.; Fiani, B.; Zhu, L.; Musch, B.L.; et al. The Neurophysiology of Caffeine as a Central Nervous System Stimulant and the Resultant Effects on Cognitive Function. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Silva, T.G.; Montagner, C.C.; Martinez, C.B.R. Evaluation of Caffeine Effects on Biochemical and Genotoxic Biomarkers in the Neotropical Freshwater Teleost Prochilodus Lineatus. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2018, 58, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.T.; Greenway, S.L.; Farris, J.L.; Guerra, B. Assessing Caffeine as an Emerging Environmental Concern Using Conventional Approaches. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2008, 54, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, J.A.; Quadra, G.R.; Almeida, R.M.; Soranço, L.; Lobo, H.; Rocha, V.N.; Bialetzki, A.; Reis, J.L.; Roland, F.; Barros, N. Sublethal Effects of Environmental Concentrations of Caffeine on a Neotropical Freshwater Fish. Ecotoxicology 2022, 31, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojemaye, C.Y.; Pampanin, D.M.; Sydnes, M.O.; Green, L.; Petrik, L. The Burden of Emerging Contaminants upon an Atlantic Ocean Marine Protected Reserve Adjacent to Camps Bay, Cape Town, South Africa. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.R.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Freitas, R. Caffeine as a Contaminant of Concern: A Review on Concentrations and Impacts in Marine Coastal Systems. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lai, R.W.S.; Galban-Malag, C.; Adell, A.D.; Mondon, J.; Metian, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical Pollution of the World’s Rivers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosekiemang, T.T.; Stander, M.A.; de Villiers, A. Simultaneous Quantification of Commonly Prescribed Antiretroviral Drugs and Their Selected Metabolites in Aqueous Environmental Samples by Direct Injection and Solid Phase Extraction Liquid Chromatography - Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, A.O.; Forbes, P.B.C. Antiretroviral Drugs in African Surface Waters: Prevalence, Analysis, and Potential Remediation. Environ Toxicol Chem 2022, 41, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooding, M.; Rohwer, E.R.; Naudé, Y. Determination of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Antiretroviral Compounds in Surface Water: A Disposable Sorptive Sampler with Comprehensive Gas Chromatography – Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry and Large Volume Injection with Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2017, 1496, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.M.M.; Godinho, A.L.A.; Martins, I.L.; Justino, G.C.; Beland, F.A.; Marques, M.M. Amino Acid Adduct Formation by the Nevirapine Metabolite, 12-Hydroxynevirapine--a Possible Factor in Nevirapine Toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol 2010, 23, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Liu, C.E.; Lee, Y.C.; Yang, C.J.; Tsai, M.S.; Cheng, S.H.; Lin, S.P.; Lin, D.Y.; Wang, N.C.; et al. Multicenter Study of Skin Rashes and Hepatotoxicity in Antiretroviral-Naïve HIVpositive Patients Receiving Non-Nucleoside Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitor plus Nucleoside Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors in Taiwan. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, M.S.; Thomas, D.L.; Mehta, S.H.; Chaisson, R.E.; Moore, R.D. Hepatotoxicity Associated with Nevirapine or Efavirenz-Containing Antiretroviral Therapy: Role of Hepatitis C and B Infections. Hepatology 2002, 35, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, A.; Mira, J.A.; Pineda, J.A. Liver Toxicity Induced by Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 59, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, T.A.; Worku, A.; Kebede, Y.; Alemu, K.; Kasim, A.; Shkedy, Z. Choice of Initial Antiretroviral Drugs and Treatment Outcomes among HIV-Infected Patients in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Syst Rev 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, S.; Madikizela, L.M.; Chimuka, L.; Nindi, M.M. Environmental Fate and Ecotoxicological Effects of Antiretrovirals: A Current Global Status and Future Perspectives. Water Res 2018, 145, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, C.; Dlamini, M.; Okonkwo, O.J. The Impact of a Wastewater Treatment Works in Southern Gauteng, South Africa on Efavirenz and Nevirapine Discharges into the Aquatic Environment. Emerg Contam 2017, 3, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abafe, O.A.; Späth, J.; Fick, J.; Jansson, S.; Buckley, C.; Stark, A.; Pietruschka, B.; Martincigh, B.S. LC-MS/MS Determination of Antiretroviral Drugs in Influents and Effluents from Wastewater Treatment Plants in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Chemosphere 2018, 200, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Krzyszczak, A.; Boguszewska-Czubara, A.; Opielak, G.; Jośko, I.; Hojamberdiev, M. Revealing the Toxicity of Lopinavir- and Ritonavir-Containing Water and Wastewater Treated by Photo-Induced Processes to Danio Rerio and Allivibrio Fischeri. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 824, 153967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, A.M.; Shapiro, N.I.; Wild, J.; Brown, S.M.; Cwik, B.J.; Hart, K.W.; Jones, A.E.; Pulia, M.S.; Self, W.H.; Smith, C.; et al. Lopinavir/Ritonavir for Treatment of Non-Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 128, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, J.R.; Dejam, A.; Voell, J.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Sklar, P.A.; Kovacs, J.A.; Cannon, R.O.; Masur, H.; Gladwin, M.T. Lopinavir-Ritonavir: Effects on Endothelial Cell Function in Healthy Subjects. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2006, 193, 1516–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istampoulouoglou, I.; Zimmermanns, B.; Grandinetti, T.; Marzolini, C.; Harings-Kaim, A.; Koechlin-Lemke, S.; Scholz, I.; Bassetti, S.; Leuppi-Taegtmeyer, A.B. Cardiovascular Adverse Effects of Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 Patients: Cases from a Single Pharmacovigilance Centre. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebele, A.J.; Abou-Elwafa Abdallah, M.; Harrad, S. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in the Freshwater Aquatic Environment. Emerg Contam 2017, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madikizela, L.M. A Journey of 10 Years in Analytical Method Development and Environmental Monitoring of Pharmaceuticals in South African Waters. South African Journal of Chemistry 2023, 77, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong Vo, H.N.; Le, G.K.; Hong Nguyen, T.M.; Bui, X.T.; Nguyen, K.H.; Rene, E.R.; Vo, T.D.H.; Thanh Cao, N.D.; Mohan, R. Acetaminophen Micropollutant: Historical and Current Occurrences, Toxicity, Removal Strategies and Transformation Pathways in Different Environments. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwalana, A.E.; Musvuugwa, T.; Sikwila, S.T.; Sefadi, J.S.; Whata, A.; Nindi, M.M.; Chaukura, N. The Screening of Emerging Micropollutants in Wastewater in Sol Plaatje Municipality, Northern Cape, South Africa. Environmental Pollution 2022, 314, 120275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.; Dobreniecki, S.; Ford, E.; et al. Acetaminophen. Scoping Document: Recommendation for Anticipated Data and Human Health Risk Assessments for Registration Review; 2023; https://downloads.regulations.gov/EPA-HQ-OPP-2022-0816-0004/content.pdf.

- Madikizela, L.M.; Nuapia, Y.B.; Chimuka, L.; Ncube, S.; Etale, A. Target and Suspect Screening of Pharmaceuticals and Their Transformation Products in the Klip River, South Africa, Using Ultra-High–Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Environ Toxicol Chem 2022, 41, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, O.; Dabrowski, J.M.; Montaseri, H.; Nsibande, S.A.; Petersen, F.; Forbes, P.B.C. DEVELOPMENT OF NOVEL FLUORESCENT SENSORS FOR THE SCREENING OF EMERGING CHEMICAL POLLUTANTS IN WATER Report to the Water Research Commission. Water Research Commission 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) Acetaminophen in Drinking Water. Available online: www.health.state.mn.us/eh (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Rimayi, C.; Odusanya, D.; Weiss, J.M.; de Boer, J.; Chimuka, L. Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the Hartbeespoort Dam Catchment and the UMngeni River Estuary 2016 Pollution Incident, South Africa. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 627, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Geißen, S.U.; Gal, C. Carbamazepine and Diclofenac: Removal in Wastewater Treatment Plants and Occurrence in Water Bodies. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K’oreje, K.O.; Okoth, M.; Van Langenhove, H.; Demeestere, K. Occurrence and Treatment of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the African Aquatic Environment: Literature Review and a Look Ahead. J Environ Manage 2020, 254, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, T.G.; Dube, S.; Nindi, M.M. Removal of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and Carbamazepine from Wastewater Using Water-Soluble Protein Extracted from Moringa Stenopetala Seeds. J Environ Chem Eng 2018, 6, 3095–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanderud, S.; Myking, O.L.; Strandjord, R.E. The Influence Of Carbamazepine On Thyroid Hormones And Thyroxine Binding Globulin In Hypothyroid Patients Substituted With Thyroxine. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1981, 15, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanderud, S.; Strandjord, R.E. Hypothyroidism Induced by Anti-epileptic Therapy. Acta Neurol Scand 1980, 61, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugegoda, D.; Kibria, G. Effects of Environmental Chemicals on Fish Thyroid Function: Implications for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Australia. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2017, 244, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraz, S.; Lee, A.H.; Pollard, S.; Srinivasan, K.; Vermani, A.; David, E.; Wilson, J.Y. Paternal Exposure to Carbamazepine Impacts Zebrafish Offspring Reproduction over Multiple Generations. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 12734–12743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, P.; Escher, B.I.; Baduel, C.; Virta, M.P.; Lai, F.Y. Antimicrobial Transformation Products in the Aquatic Environment: Global Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Risks, and Potential of Antibiotic Resistance. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 9474–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health; Prevention, C. for D.C.; (OARAC), H.M.A. of the I.D.S. of A.P. on G. for the P. and T. of O.I. in A. and A. with H.A.W.G. of the O. of A.R.A.C. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2024.

- Kwon, B.; Kho, Y.; Kim, P.G.; Ji, K. Thyroid Endocrine Disruption in Male Zebrafish Following Exposure to Binary Mixture of Bisphenol AF and Sulfamethoxazole. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 48, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, T.V.; Rocha, M.J.; Cruzeiro, C.; Galante, M.H.; Monteiro, R.A.F.; Rocha, E. The Toxicity Potential of Pharmaceuticals Found in the Douro River Estuary (Portugal): Assessing Impacts on Gonadal Maturation with a Histopathological and Stereological Study of Zebrafish Ovary and Testis after Sub-Acute Exposures. Aquatic Toxicology 2011, 105, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.B.; Bistas, K.G.; Patel, P.; Le, J.K. Clindamycin. In xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference; StatPearls Publishing, 2024; pp. 1–4 ISBN 9780080552323.

- EU Commission Proposal Amending Water Directives - European Commission; 2022; European Commission, Official Journal of the European Communities 0344.

| Sites | Location | Coordinates | Elevation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nzhelele River after Mutshedzi River joint | 22°53ˈ10.59” S; 30°08ˈ13.90” E | 746 m |

| 2 | In the river below Mutshedzi Dam | 22°56ˈ43.30” S | 846 m |

| 3 | Mutshedzi Dam | 22°56ˈ47.30” S; 30°10ˈ14.00” E | 865 m |

| 4 | Tshiluvhadi River | 22°57ˈ18.59” S; 30°11ˈ56.26” E | 923 m |

| 5 | Nzhelele River below Shiloam Hospital oxidation ponds | 22°54ˈ15.86” S; 30°10ˈ50.53” E | 787 m |

| 6 | Next to Shiloam Hospital, receiving water from the hospital | 22°54ˈ09.21” S; 30°11ˈ40.17” E | 801 m |

| 7 | Below point 8 (stream below the oxidation ponds) | 22°54ˈ14.48’’S; 30°11ˈ32.65” E | 796 m |

| 8 | Upstream Nzhelele River at Fondwe near villages | 22°55ˈ23.17” S; 30°16ˈ08.56” E | 848 m |

| 9 | Holy Forest Lake 1 (HFL1) inflow | 22°54ˈ17.06” S; 30°20ˈ54.62” E | 1084 m |

| 10 | HFL1 | 22°54ˈ12.62” S; 30°21ˈ08.36” E | 1083 m |

| 11 | HFL1 | 22°54ˈ02.65” S; 30°21ˈ33.14” E | 1082 m |

| 12 | Before overflow HFL1 | 22°53ˈ56.05” S; 30°21ˈ47.29” E | 1085 m |

| 13 | Below the overflow HFL1 | 22°53ˈ48.50” S; 30°22ˈ00.82” E | 1081 m |

| 14 | Tshinane River inflow stream below old oxidation ponds | 22°53ˈ49.92” S; 30°29ˈ58.11” E | 585 m |

| 15 | The small stream next to the tea plantation flowing into Tshinane River | 22°54ˈ57.04” S; 30°25ˈ21.97” E | 681 m |

| 16 | Tshinane River before no 19 flows in | 22°54ˈ56.41” S; 30°25ˈ23.58” E | 676 m |

| 17 | Before the outflow of the Tate Vondo Dam | 22°56ˈ49.55” S; 30°21ˈ09.67” E | 870 m |

| 18 | Along the TateVondo Dam shores | 22°56ˈ41.48” S; 30°20ˈ29.79” E | 871 m |

| 19 | Closer to the inflow of the TateVondo Dam | 22°56ˈ26.78” S; 30°20ˈ11.44” E | 871 m |

| 20 | In the Tshikhwikhwikhwi River | 22°57ˈ39.25” S; 30°10ˈ51.63” E | 885 m |

| 21 | Below the Thohoyandou WWTW and oxidation ponds in the Mvudi River | 23°00ˈ11” S; 30°29ˈ14” E | 517 m |

| SITES | Caffeine | Nevirapine | Lopinavir | Acetaminophen | Fluconazole | Sulfamethoxazole | Clindamycin | Carbamazepine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n.d | 109 | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 2 | 181 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 3 | 584 | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 4 | 110 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 5 | >1000 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 6 | n.d | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 7 | n.d | 166 | 42 | n.d | >1000 | n.q | n.d | 21 |

| 8 | 94 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 9 | >1000 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 10 | >1000 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 11 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 12 | >1000 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 13 | >1000 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 14 | 159 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 15 | >1000 | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 16 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.q |

| 17 | 479 | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 18 | 217 | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 19 | n.d | n.q | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d |

| 20 | 690 | n.q | n.d | 292 | n.d | n.d | n.q | n.d |

| 21 | 975 | 7 | n.d | 427 | n.d | n.d | n.q | n.q |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).