1. Introduction

Soil health directly influences the productivity of crops, cycling of nutrients and water holding capacity [

1]. Rapid increase in human population and the increasing demand for food require improvement in soil health for agricultural production [

2]. Currently, the application of chemical fertilizers, unsustainable land management and farming practices are considered as some of the major leading causes of soil infertility which potentially causes reduction in water holding capacity and decrease in organic matter in soil [

3]. Biochar from lignocellulosic biomass has gained attention over the years as a key solution for enhancing soil health [

4]. Biochar is a carbon rich material made from biomass through thermochemical conversion methods [

5,

6].

Biochar applied to soil is capable of separating soil particles thereby preventing soil compaction, improving soil water holding capacity, and reducing drought and water stress [

7,

8]. Moreover, biochar enhances the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of soil by providing a high surface area with functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl which attract and hold onto nutrient cations like calcium, potassium and magnesium [

9,

10].

Research involving biochar for soil health has mainly focused on biomass pyrolysis biochar [

11,

12]. However, biomass pyrolysis is unlikely to be commercialized on a large scale due to the low yield of the main product, i.e., the pyrolysis bio-oil [

13]. Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) has emerged as the most promising biomass liquefaction method over pyrolysis due to the utilization of wet biomass feedstocks, moderate temperature and minimum loss of carbon and energy to gaseous products [

14].

However, little prior work is found in literature for the valorization of HTL byproduct, hydrochar, for soil health. Since HTL hydrochar is different in chemical makeup from pyrolysis biochar (hydrocarbon vs. mainly carbon), some key properties pertaining to its potential to enhance soil health remain unknown to us. However, we hypothesized that, the HTL hydrochar owns three important physiochemical properties similar to pyrolysis biochar that allows it to enhance soil health such as porosity, functional groups capable of performing cation exchange and low biodegradability. In this study, we characterize physical and chemical properties of the HTL hydrochar, determine its biodegradation rate in the soil and quantify the effect of application rates on the water holding capacity and water retention ability of the soil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The solvents, ethylene glycol (EG) and 2-ethyl hexanol (EH), diammonium phosphate, potassium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid were purchased from Fisher-Scientific and used as received. Corn stover was obtained from the Diary Farm of South Dakota State University, USA. The dried corn stover was ground into powder by a hammer mill (M150, Winona Attrition Mill Co. MN 55987) equipped with a 1 mm screen. The corn stover powder has a moisture content of 4.67% as determined by drying at 105 °C to a constant weight. The sandy loam soil used was sampled from the surface of Sanderson’s Gardens in Brookings, SD, USA.

2.2. Hydrothermal Liquefaction Experiments

The HTL experiments were performed using a 1-L Parr instruments Series 4600 pressure vessel with an I.D. and depth of 4ʺ × 5.4ʺ. A molten salt bath was used for heating. After the addition of solvents (255.0 g EH, 158.4 g of EG, 65 g water), corn stover 34.00 g was added and a magnetic oval stir bar (19 × 62 mm), the reactor was sealed and heated in the bath. The air in the reactor was removed by releasing vapor of about of about 5 mL solvent mixture (mostly water) after the reactor reached about 150 °C. The reaction temperature was then ramped to 280 °C at a rate of 5 °C/ min and kept at the temperature for 1 h. The reactor was cooled with tap water and another batch of corn stover was added. The same procedure was repeated to continue the liquefaction until a total of 8 batches of 34 g of corn stover were added. After the addition of the last batch, the reaction was run for 14 h. The reaction mixture was filtered and the solid was washed with 100 mL of chloroform and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C for 5 h. The mass of the dried solid residue (hydrochar) which is insoluble in water and organic solvents was recorded. The washing, after removing chloroform by vacuum rotary evaporation, was combined with the organic portion of the reaction mixture filtrate. The combined mixture was distilled under vacuum (15 mbar) and at a final temperature of 220 °C for 10 minutes to recover organic solvents and obtain the heavy biocrude (HBC) as the distillation residue.

2.3. Ash Content in the Hydrochar and Treatment of the Hydrochar for FT-IR

The ash content in the hydrochar was determined by calcining 200 mg of the hydrochar at 700 °C in air for 2 h. After cooling in a glovebox, the mass of ash was determined to be 82.1%.

To minimize the effect of the ash content in the hydrochar on FT-IR analysis of the organic content of the hydrochar, the hydrochar was treated using 4N HCl and 10% hydrofluoric acid. Briefly, 200 mg of the hydrochar was weighed and transferred into a beaker. 4N HCl (3 mL) was added to dissolve carbonates. After 1 h of treatment, the mixture was filtered and the solid was washed using deionized water. Subsequently, the resulting solid was further treated with approximately 10% HF (3 mL) in a beaker for 70 minutes to dissolve silicates in the hydrochar in a plastic beaker. The contents in the beaker were filtered and washed with DI water. The solid was dried under vacuum with heating until the mass became constant.

2.3. BET, FT-IR and SEM

Micrometrics Tristar II 3020 was used to determine the specific surface area of the hydrochar based on nitrogen adsorption and the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. The hydrochar was degassed under vacuum at 105 °C prior to analysis for a minimum of 1 hr. and 20 mins. In the relative pressure range (p/po) of 0.00 to 0.25, the specific surface area of the hydrochar was quantified with the BET adsorption method (use of BET equation ISO 9277). A PerkinElmer FTIR spectrometer was used to determine the infrared spectra. A sample of hydrochar sample was prepared in 200 mg of KBr and pressed into a pellet.

Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) Images were taken with an S-4700 scanning electron microscope. The hydrochar was deposited on a sample holder attached with a carbon conducting tape. The sample was coated with gold using a CRC-I150 sputtering.

2.4. Water Holding Capacity (WHC)

To determine the water holding capacity of the hydrochar in accordance with D425 standard [

15], an experiment with four treatments which includes a control (soil only) and a varying weight of hydrochar (1, 3 and 5 wt.% based on the mass of soil) were conducted. The design of the experiment consisted of sieving a dry soil sample (˂ 26 mesh). In this study, a blend of the hydrochar at different percent weight and 200 g of the dry soil was placed in a PVC tube of D = 4.5 cm with a nylon fabric at the bottom. The package tube was weighed. After thorough mixing, the samples were slowly drenched with 200 mL of water from the top of the tube. The tube was weighed when there was no water seeping out. All experiments were done in triplicates. Data was collected and the WHC was determined using the following equation

Water holding capacity (%) = [(Weight of water absorbed) / weight of soil hydrochar mixture] × 100.

2.5. Water Retention

Water retention refers to the ability of soil to retain water against the force of gravity and evaporation [

16]. To determine the water retention of the hydrochar, an experiment with four treatments which includes a control (soil only) and a varying weight of hydrochar (1, 3 and 5% wt.) was conducted. The design of the experiment consisted of sieving a dry soil sample (< 26 mesh). In this study, a blend of hydrochar and 100 g of dry soil was placed in a glass beaker. The initial mass of the mixture was recorded as (M

0). An appropriate amount of tap water (100 mL) was added into the beaker to make the soil saturated, and then the beakers were kept under ambient temperature. The weight of the wet mixture was recorded daily as M

1. All experiments were done in triplicates. Data was collected and the water retention capacity of the mixture was determined using the following equation

Water retention (%) = [(M1 − M0) / 100 g of dry soil)] × 100.

2.6. Biodegradability Experiments

HTL hydrochar biodegradation experiment: In this experiment, CO2 released from the hydrochar was monitored as an indicator of biodegradation. The Soil pH was determined on a 5:1 (distilled water:soil) slurry using a glass combination electrode calibrated with standard buffers. Soil moisture was determined overnight in accordance with D2974 standard. Elemental analysis of the soil was performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc., Norcross, GA 30071, United states to determine the percent composition of Carbon (C) and Nitrogen (N) in the soil. The biodegradability test was conducted in quadruplicate in a 1-gallon plastic buckets sealed with gamma seal screw-on airtight lid. About 200 g of soil was placed in the bottom of the bucket. A solution of 1 g of diammonium phosphate in 67.18 mL of deionized water was added to amend the soil with nitrogen to give a C:N of between 10:1 (by weight) and bring the moisture level to 80% of WHC. The weight of the bucket and the lid together with the amended soil was recorded. About 6 g of hydrochar was added and mixed thoroughly with the soil. A 100-mL beaker with 20 mL of 0.5 N basic solution (KOH) and a 100-mL beaker with 50 mL of deionized water were placed in the bucket to absorb CO2 generated and maintain the moisture level. The bucket was sealed and placed in the lab at a constant temperature of 21 °C. The CO2 generated in each bucket was later determined by acid-base titration after an initial recommended period of 2 weeks and a subsequent period of one month thereafter.

HTL heavy biocrude (HBC) biodegradation experiment: In this experiment, mass loss was monitored as an indicator of biodegradation. This requires the easy separation of the heavy biocrude from the matrix. To achieve this objective, the heavy biocrude was melt-coated onto pellets of a soluble salt (ammonium sulfate) to increase the size of particle (for easy separation) and the surface area for more interaction with the matrix. Potting mix was used as the matrix to facilitate separation as soil can stick to the surface of the pellets and affect mass determination. A cheese cloth made of cellulose fibers was used to wrap a mixture of 2.46 g potting mix and 2.00 g coated pellets, and seven samples (wrapped mixture) were prepared and buried in potting mix in a 2-gallon pot. The potting mix was kept wet by regular watering. Samples were removed from the pot at different time intervals. The pellets in the samples were carefully separated manually from the potting mix using a tweezer. The pellets were soaked in water and crushed to release all the salt. The HBC coating was collected by filtration and dried at 80 °C in an oven. The mass of dried HBC was recorded. The original mass of the coating was calculated from the weight% of the coating in the pellets.

2.7. Data Analysis

The report of all indices represents the mean value of triplicate samples. Excel was used to analyze data and generate figures.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Specific Surface Area, FTIR and SEM Characterization of Hydrochar

The specific surface area of hydrochar is critical for its effectiveness in improving soil health as it directly plays a key role in the interaction between the hydrochar particles and the soil matrix. These interactions affect key functions such as water holding and retention, microbial activity and nutrient adsorption. The specific surface area of the MA2 hydrochar is presented in

Table 1 together with the literature results of corn stover pyrolysis biochars for comparison. The BET surface area was found to be 27.61 m

2/g, better than those reported from the work of Lee et al., 2010 as shown in the table below [

17].

Table 1.

Comparison of BET specific surface area of HTL and fast pyrolysis corn stover.

Table 1.

Comparison of BET specific surface area of HTL and fast pyrolysis corn stover.

| This work (HTL at 280 °C) |

Fast pyrolysis (450 °C) [17] |

| 27.61 m2/g |

12-26 m2/g |

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of the hydrochar before and after acid treatment.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of the hydrochar before and after acid treatment.

The FT-IR spectra of the hydrochar before and after acid treatment are shown in

Figure 1. The spectrum of the untreated hydrochar showed characteristic band similar to that of soil [

18]. It makes sense since the untreated hydrochar is 82.1% ash, which is likely to be the dirt from the field. To obtain the FT-IR spectrum of the organic portion of the hydrochar, the pristine hydrochar was treated using 4N HCl and 10% hydrofluoric acid. The acid treatment removed 75% of the mass, which is 91% of the ash content. The FT-IR spectrum shows a much-pronounced C-H peak at 2925 cm

-1. Dominant peaks are O-H, C-H, C-O and aromatic ring stretching and Ar-H bending peaks. The peak at 1693 cm

-1 Indicates the presence of carboxylic acid, though in a smaller abundance compared to alcoholic groups. The IR spectrum and the fact that the hydrochar is not soluble in any organic solvent suggest that the hydrochar is crosslinked decomposition product of the lignin in corn stover. Indeed, it resembles the IR spectrum of lignin in some regions, particularly the region of 3700-2700 cm

-1 [

19]. On the other hand, the FT-IR spectrum of the hydrochar looks very different from those reported for biochars produced from cornstover pyrolysis for soil amendment as reported by Lee et., 2010 [

17]. The biochar does not show a significant presence of hydrocarbon as expected. However, it also has a lower abundance in both OH and COOH. The higher surface area and richer polar groups make the hydrochar potentially better at enhancing the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of soil.

Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) Images were obtained with magnifications of 5,000 and 20,000 and are shown in

Figure 2. The hydrochar particles are highly irregular in shape with size ranging from 15 to 40 µm. Under the magnification of 20K, the particles exhibit as irregular stacks of foliates with thickness on the order of 100 nm. No pores are seen in the foliates, so the specific surface area can be attributed to the surface of nanometer-thick sheets.

3.2. Water Holding Capacity

Water holding capacity (WHC) of soil is a critical factor for plant growth as it is the ability of a certain soil texture to physically hold water against the force of gravity. Soil structure, texture and available organic matter significantly contribute to WHC. Conservational agricultural practices which include crop diversification, mulch cover and minimal soil disturbance are some practices that improve WHC through the alteration of pore size distribution and increasing soil organic carbon [

20].

Managing and understanding WHC is crucial for the regulation of irrigational practices thereby ensuring sustainable crop production [

21]. The results obtained from this study indicate how hydrochar can increase WHC of the soil. The results support the hypothesis that hydrochar significantly improves the water holding capacity of sandy loam soils. The average WHC and relative enhancement in WHC of the hydrochar are shown in

Figure 3 for the control and three hydrochar loadings.

Figure 2.

SEM images of the hydrochar with different magnifications: 5,000 (a) and 20,000 (b).

Figure 2.

SEM images of the hydrochar with different magnifications: 5,000 (a) and 20,000 (b).

Figure 3.

Comparison of average water holding capacities of hydrochar-amended, control soil samples and relative enhancement in WHC. Average standard deviations were used to draw the error bars.

Figure 3.

Comparison of average water holding capacities of hydrochar-amended, control soil samples and relative enhancement in WHC. Average standard deviations were used to draw the error bars.

The hydrochar-amended soil showed an improvement in the WHC compared to the control. The control had a WHC of 48.1% and this was increased to 49.6, 52.0 and 54.9% respectively when the soil was treated with 1, 3 and 5 wt.% of hydrochar. The relative increases are 3.2, 8.2 and 14.3%. The relative increase in water holding capacity of the amended soil is plotted in

Figure 3b. The enhancement in WHC is found to increase linearly with hydrochar loading, showing a great potential for substantial enhancement by increasing hydrochar loading. The enhancement can be attributed to the ability of the hydrochar to isolate soil particles and create pores at the interface of hydrochar particles and soil particles. The same functions have been confirmed in various studies showing that the amendment of soil with hydrochar (produced from orange peel via hydrothermal carbonization) and biochars (produced from pyrolysis) enhances soil moisture by altering the pore size distribution of the soil [

22,

23].

Moreover, it is found that the HTL hydrochar outperforms those found for pyrolysis biochar by Peake et al., 2014 [

24] on treating eight different types of soil with the addition of 0–2.5 wt.% of biochar. Since the ash content in our hydrochar is 82.1%, the true biochar loading of 5 wt.% is only 0.90 wt.%. Linear scaling of the relative enhancement in WHC of 14.3% for 0.90 wt.% of true hydrochar loading would result in a relative enhancement in WHC of 39.7% for 2.5 wt.% true hydrochar loading, which outperforms the biochar on seven out of the eight soil samples at 2.5 wt.% biochar loading.

3.3. Water Retention

Water retention is an important soil property which directly relates to the soil texture, organic matter content and density [

25]. In agricultural topsoil, the composition is approximately 25% water, 25% air, 45% minerals and 5% other materials. The water content can range significantly from 1 to 90% which is influenced by the soil’s retention and drainage characteristics [

26]. In recent years, there has been extensive research on how biochar affects soil water retention in agricultural soils. Some studies have found out that adding biochar alters the soil water retention compared to soils without biochar, while others have observed no change in the soil water retention upon biochar addition [

27].

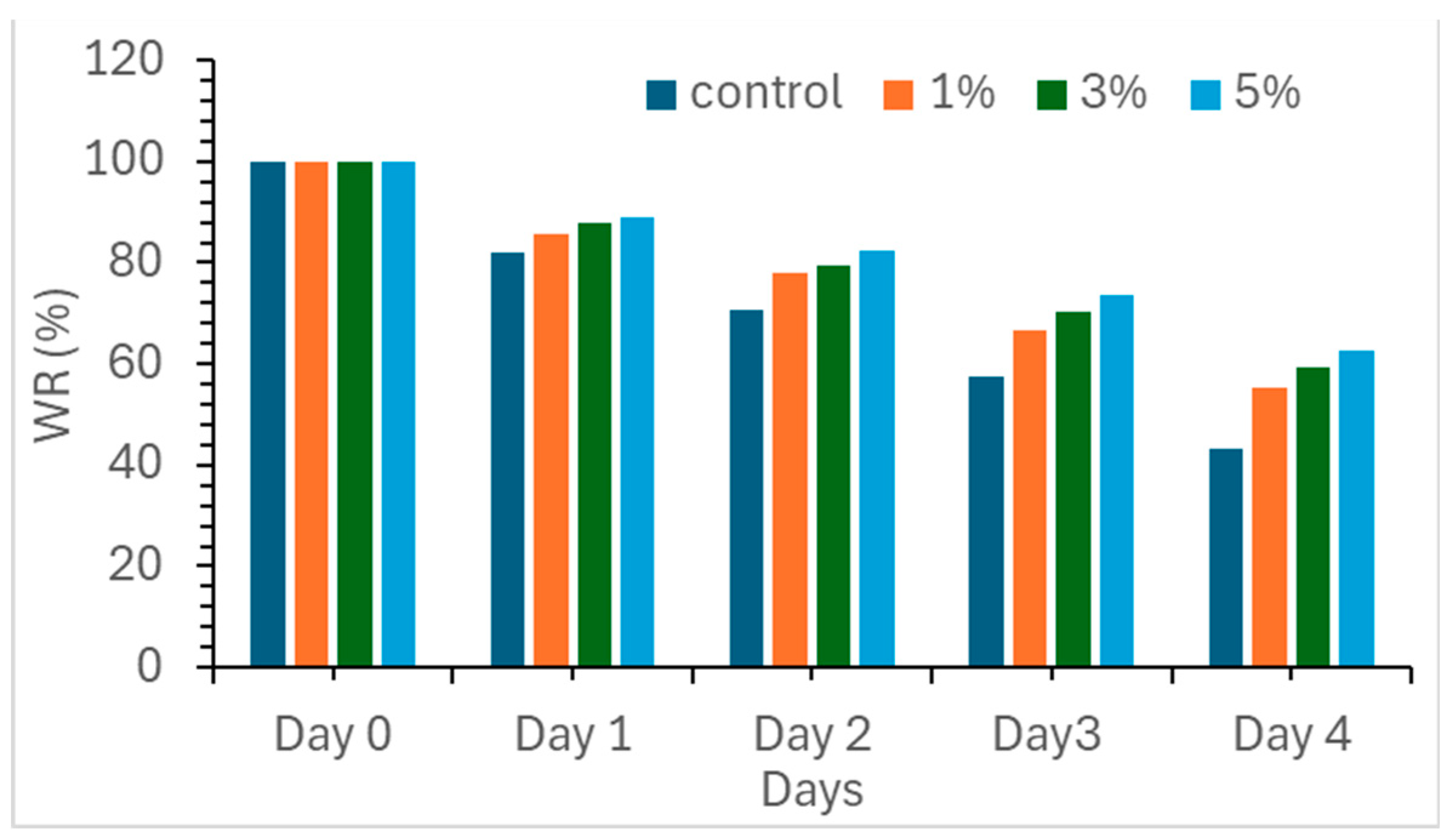

Figure 4.

Water retention of hydrochar amended soil and control soil.

Figure 4.

Water retention of hydrochar amended soil and control soil.

The effect of HTL hydrochar on soil water retention is rarely studied. In this study, water retention in soil samples amended with different amounts of biochar was recorded daily for four days. From day 0 to day 4, water retention changes from 100% to 43.3, 55.2, 59.2 and 62.5%, for the control, and soil samples loaded with 1, 3 and 5 wt.% of hydrochar, respectively. Clearly, water retention improves with the loading of hydrochar. The enhancement can be attributed to the ability of the hydrochar to enhance the soil's porosity, reduce soil compactness and hence reduce water transportation rate, resulting in a slower water evaporation rate [

28]. This observation is consistent with the findings of multiple studies that demonstrate the positive impact of hydrochar (produced by hydrothermal carbonization) and biochar (obtained from carbonization in simple kilns at T between 400 and 600 °C for 48h) on soil moisture retention [

29,

30].

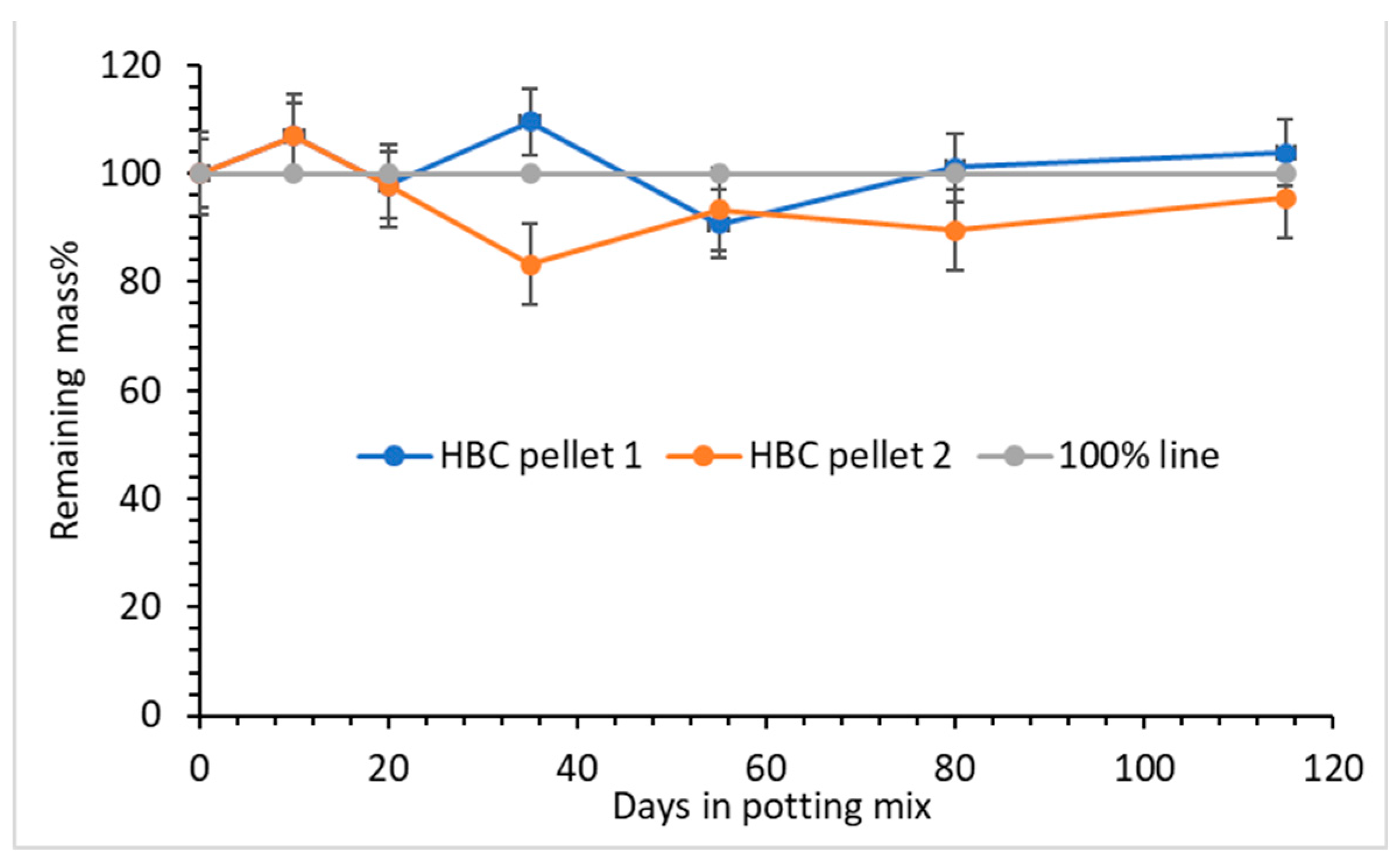

3.4. Biodegradibility of the Hydrochar and Heavy Biocrude (HBC)

Biodegradation of the hydrochar was conducted by mixing the hydrochar powder into wet soil (C/H/N = 3.00/0.50/0.21, pH 6.46 and a moisture level of 43.65) and monitoring the CO

2 emission over a long period of time. No significant CO

2 emission has been detected over 80 days. This result makes sense since HTL hydrochar is insoluble, crosslinked, and, as a result of crosslinking, is expected to more resistant to biodegradation [

31] than HBC. No biodegradation or mass loss has been observed for HBC over 115 days in a different test (described in

Section 2.6) in which the HBC (in the form of coating on salt pellets) was buried in wet potting mix (

Figure 5). In sharp contrast, at the end of the test, the cellulose-fiber cheese cloth, used to wrap the mixture of potting mix and the coated pellets, nearly disappeared totally due to biodegradation.

6. Conclusion

Climate change has become an imminent threat globally. The valorization of biomass, the most abundant source of renewable material, is crucial to sustainable agricultural practices and realization of carbon neutrality. Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) has emerged as the most promising biomass liquefaction method. Valorization of HTL byproduct, hydrochar, will contribute to the sustainability of future biomass thermochemical refinery. This research aims to explore the potential of HTL hydrochar for soil amendment. It is also found that the hydrochar possesses three physicochemical properties that allows it to enhance soil health, including a moderate specific surface area (27.61 m2/g), rich functional groups, nanometer-thick foliate morphology, and low biodegradability. The hydrochar-amended soil showed a linear increase in water holding with respect to the hydrochar loading, and water retention ability of the amended soil is also significantly improved over the non-amended soil.

The results obtained from this study out-perform pyrolysis biochar in enhancing water holding capacity. It is found that the hydrochar is richer in polar functional groups than biochar, making it a potentially better soil amendment in enhancing the exchange capacity (CEC) of soil for nutrient cations like calcium, potassium and magnesium. Additionally, the biodegradability studies demonstrated that both the hydrochar and the heavy biocrude do not biodegrade in soil or potting mix during the testing period of up to 115 days, thus creating a new way of carbon sequestration and addition of organic matter to soil. The demonstration of the potential of HTL hydrochar for amending soil will spark further research on its influences on plant growth, microbial activity and nutrient utilization.

Author Contributions

C.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, resources, administration, investigation, data collection and curation, formal analysis, writing― review and editing; A.R.I.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation, formal analysis, writing― original draft and editing.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

A.R.I. was supported as GTA during the project period by the Department of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Physics, South Dakota State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. Tahat, M.; M. Alananbeh, K.; A. Othman, Y.; I. Leskovar, D. Soil health and sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Sauer, T.J.; Prueger, J.H. Managing soils to achieve greater water use efficiency: a review. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telo da Gama, J. The role of soils in sustainability, climate change, and ecosystem services: Challenges and opportunities. Ecologies 2023, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, A.; Sinha, R.; Azzi, E.S.; Sundberg, C.; Enell, A. The Role of biochar systems in the circular economy: Biomass waste valorization and soil remediation. In The Circular Economy-Recent Advances in Sustainable Waste Management; IntechOpen, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Quicker, P. Properties of biochar. Fuel 2018, 217, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.J. Thermochemical conversion of biomass: Potential future prospects. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, M.; Clothier, B.; Bound, S.; Oliver, G.; Close, D. Does biochar influence soil physical properties and soil water availability? Plant Soil 2014, 376, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Timms, W.; Mahmud, M.P. Optimising water holding capacity and hydrophobicity of biochar for soil amendment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkharabsheh, H.M.; Seleiman, M.F.; Battaglia, M.L.; Shami, A.; Jalal, R.S.; Alhammad, B.A.; Almutairi, K.F.; Al-Saif, A.M. Biochar and its broad impacts in soil quality and fertility, nutrient leaching and crop productivity: A review. Agron. 2021, 11, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.; Zwart, K.; Shackley, S.; Ruysschaert, G. The role of biochar in agricultural soils. In Biochar in European Soils and Agriculture; Routledge, 2016; pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Long, A.; Fossum, B.; Kaiser, M. Effects of pyrolysis temperature and feedstock type on biochar characteristics pertinent to soil carbon and soil health: A meta-analysis. Soil Use Manage. 2023, 39, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhane, J.W.; Bhange, V.P.; Patil, P.D.; Bankar, S.T.; Kumar, S. Recent trends in biochar production methods and its application as a soil health conditioner: a review. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isahak, W.N.R.W.; Hisham, M.W.; Yarmo, M.A.; Hin, T.-y.Y. A review on bio-oil production from biomass by using pyrolysis method. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5910–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbeik, H.; Panahi, H.K.S.; Dehhaghi, M.; Guillemin, G.J.; Fallahi, A.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Amiri, H.; Rehan, M.; Raikwar, D.; Latine, H. Biomass to biofuels using hydrothermal liquefaction: A comprehensive review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM. Standard Test Method for Determining Anaerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials Under High-Solids Anaerobic-Digestion Conditions. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Lu, W. Density and salinity effects on the water retention capacity of unsaturated clayey dispersive soil. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 3285–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kidder, M.; Evans, B.R.; Paik, S.; Buchanan Iii, A.; Garten, C.T.; Brown, R.C. Characterization of biochars produced from cornstovers for soil amendment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7970–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Xu, H.; Ma, F.; Zhang, T.; Nan, X. Effects of dairy manure biochar on adsorption of sulfate onto light sierozem and its mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 5218–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandanwar, R.; Chaudhari, A.; Ekhe, J. Nitrobenzene oxidation for isolation of value added products from industrial waste lignin. J. Chem. Biol. Phys. Sci 2016, 6, 501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.; Hunter, M.C.; Kammerer, M.; Kane, D.A.; Jordan, N.R.; Mortensen, D.A.; Smith, R.G.; Snapp, S.; Davis, A.S. Soil water holding capacity mitigates downside risk and volatility in US rainfed maize: time to invest in soil organic matter? PloS ONE 2016, 11, e0160974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, A.M.; Jat, H.S.; Choudhary, M.; Abdelaty, E.F.; Sharma, P.C.; Jat, M.L. Conservation agriculture effects on soil water holding capacity and water-saving varied with management practices and agroecological conditions: A Review. Agron. 2021, 11, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalderis, D.; Papameletiou, G.; Kayan, B. Assessment of orange peel hydrochar as a soil amendment: impact on clay soil physical properties and potential phytotoxicity. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3471–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Mahmud, M.P.; Nguyen, M.D.; Timms, W. Evaluating fundamental biochar properties in relation to water holding capacity. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, L.R.; Reid, B.J.; Tang, X. Quantifying the influence of biochar on the physical and hydrological properties of dissimilar soils. Geoderma 2014, 235, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagea, I.S.; Berti, A.; Čermak, P.; Diels, J.; Elsen, A.; Kusá, H.; Piccoli, I.; Poesen, J.; Stoate, C.; Tits, M. Soil water retention as affected by management induced changes of soil organic carbon: analysis of long-term experiments in Europe. Land 2021, 10, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halászová, K.; Lackóová, L.; Panagopoulos, T. Long-term evaluation of surface topographic and topsoil grain composition changes in an agricultural landscape. Front. Environ. Sci 2024, 12, 1445068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Dodla, S.; Wang, J.J.; Pavuluri, K.; Darapuneni, M.; Dattamudi, S.; Maharjan, B.; Kharel, G. Biochar impacts on soil water dynamics: knowns, unknowns, and research directions. Biochar 2024, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, O.; Zhang, R. Effects of biochars derived from different feedstocks and pyrolysis temperatures on soil physical and hydraulic properties. J. Soils Sediments 2013, 13, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Peters, A.; Trinks, S.; Schonsky, H.; Facklam, M.; Wessolek, G. Impact of biochar and hydrochar addition on water retention and water repellency of sandy soil. Geoderma 2013, 202, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.; Lehmann, J.; Rondon, M.; Goodale, C. Fate of soil-applied black carbon: downward migration, leaching and soil respiration. Global Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.-T.; Kim, D.; Park, J.-S.; Yen, T.F. Studies of crosslinked biopolymer structure for environmental tools in terms of the rate of weight swelling ratio, viscosity, and biodegradability: part A. Environ Earth Sci. 2013, 70, 2405–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).