Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anamnesis and Diagnosis

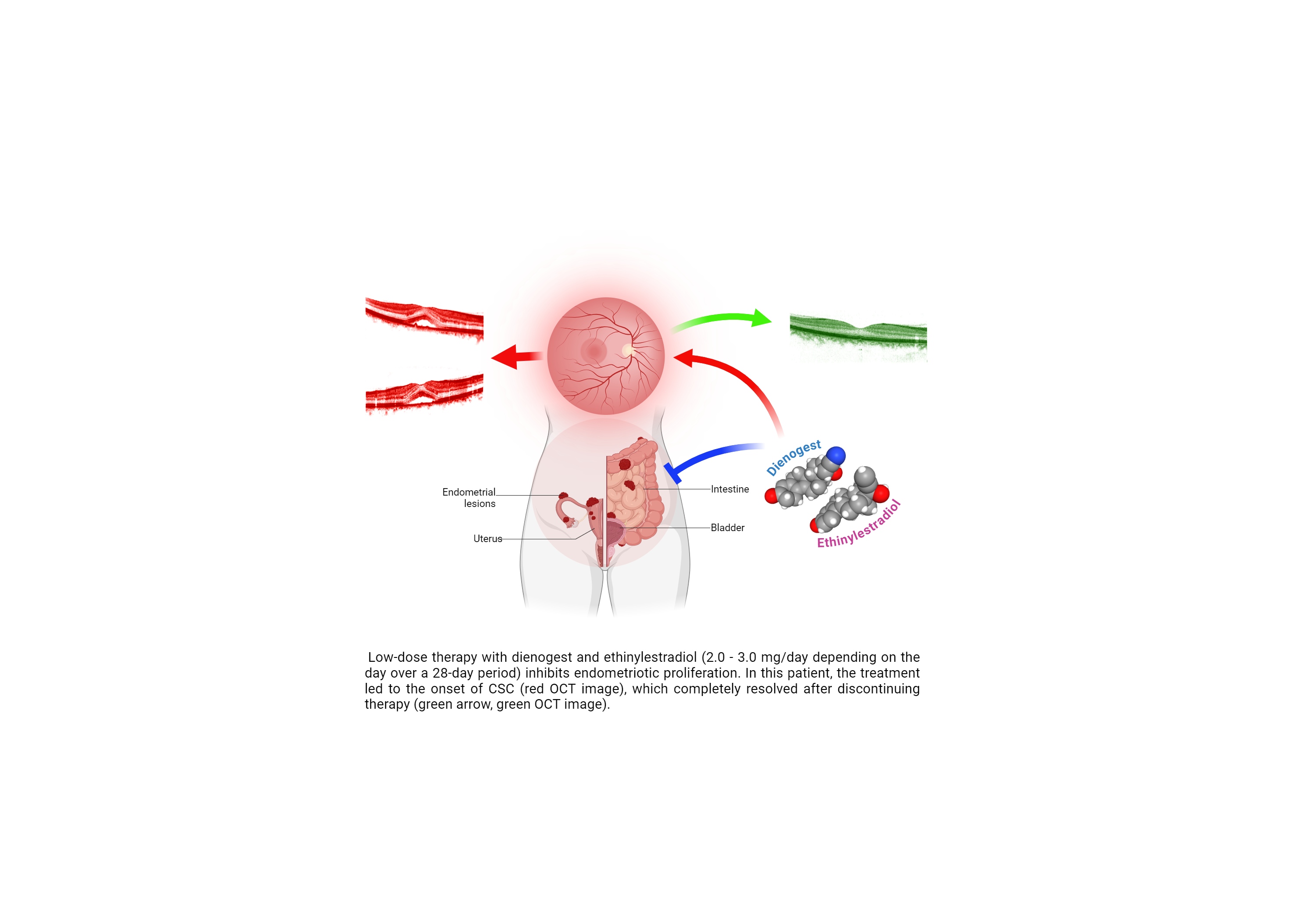

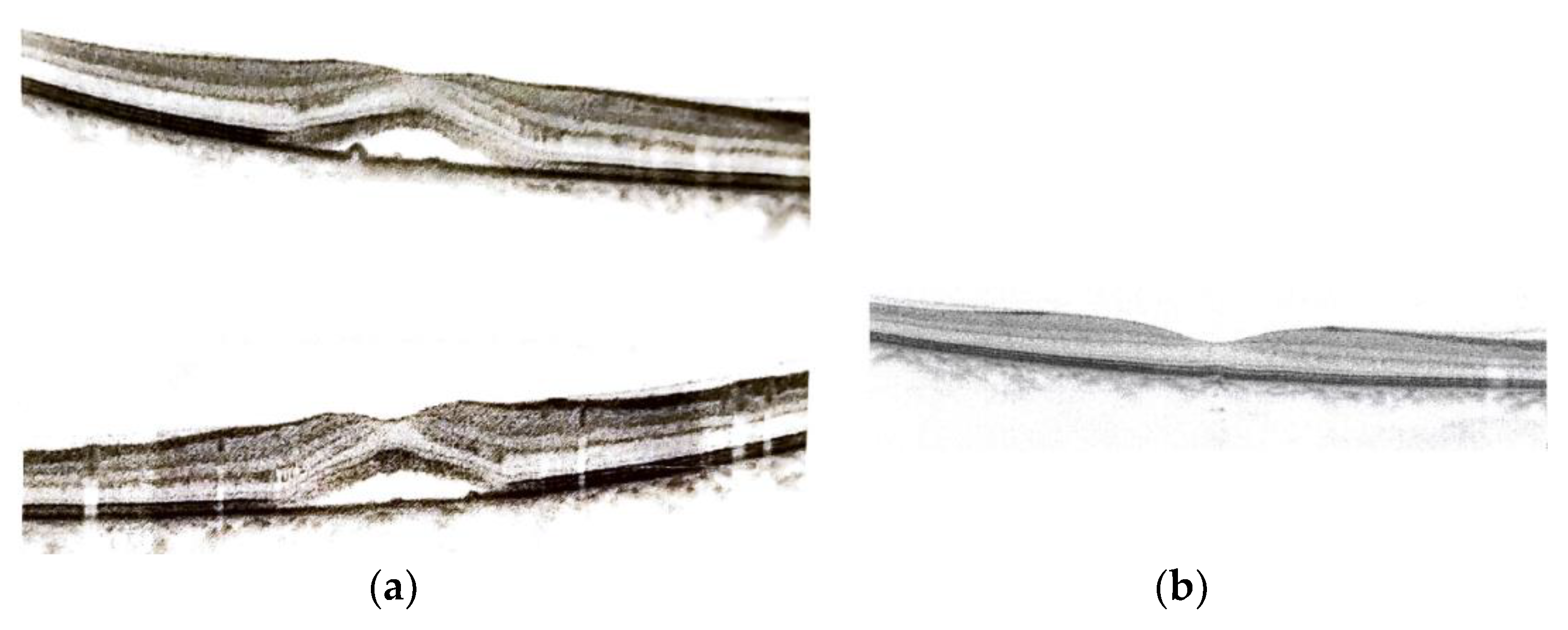

2.2. Pharmacological Treatment and Instrumental Exams

2.3. Clinical Biochemistry

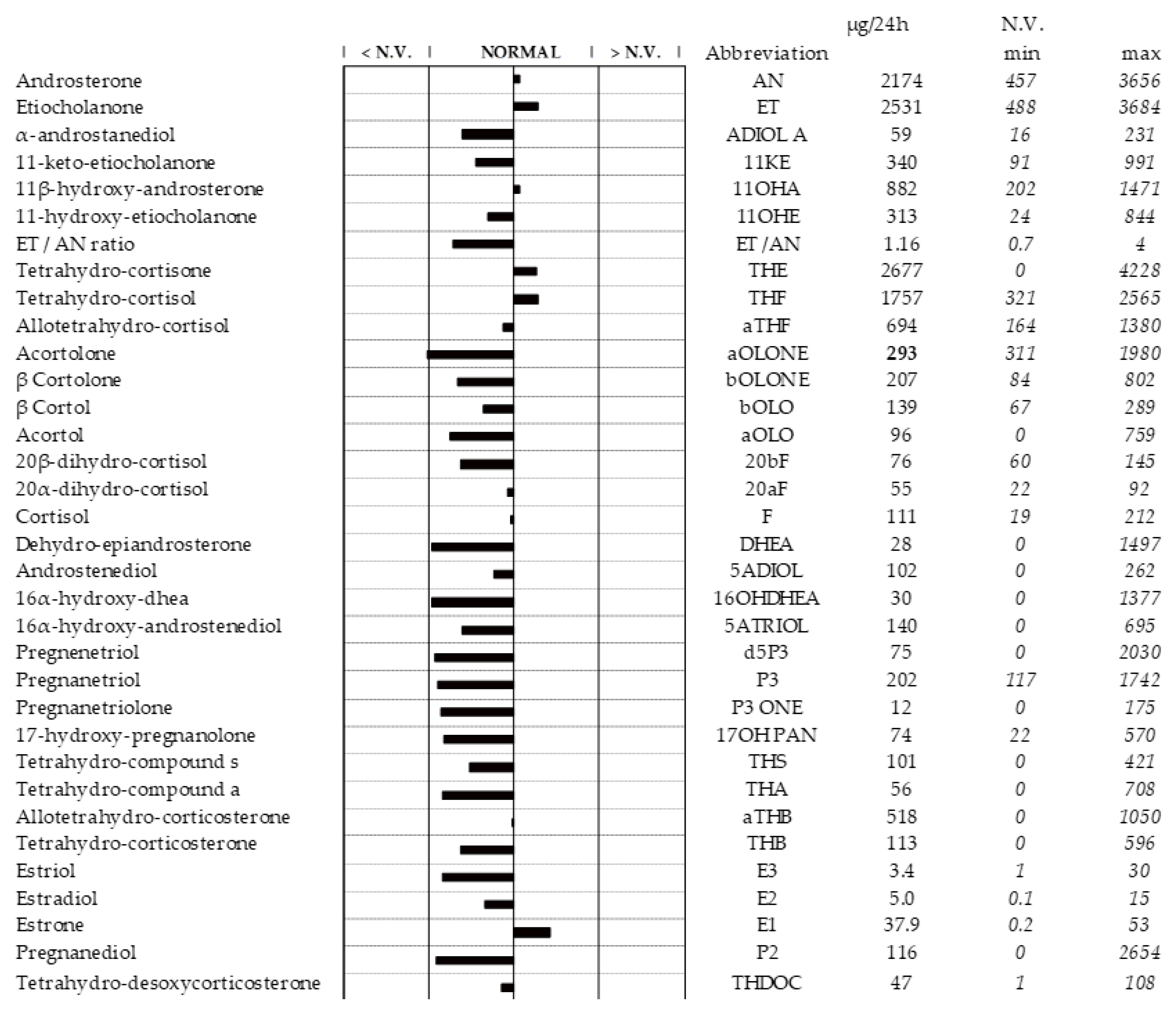

3. Results

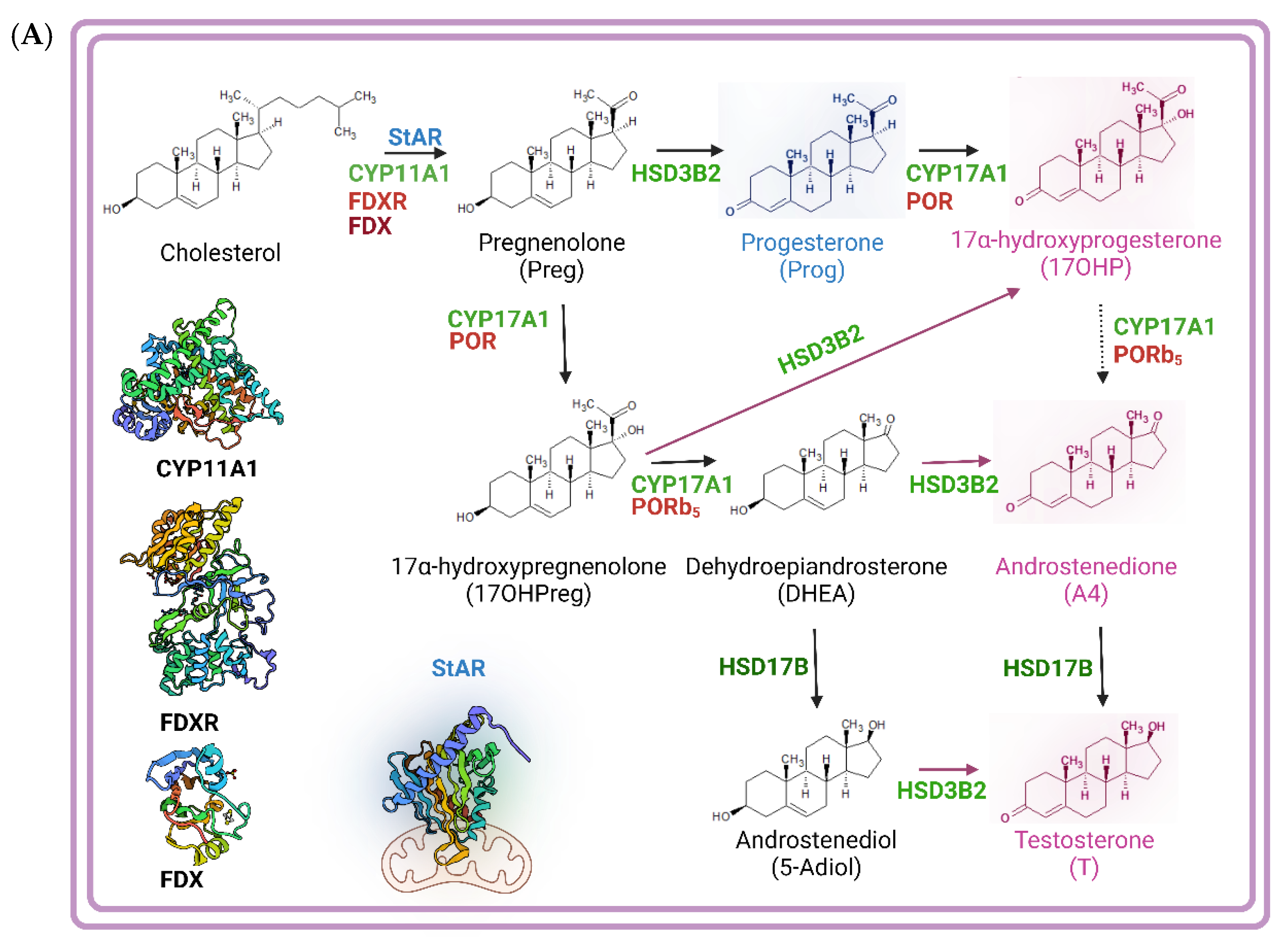

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell 2021, 184, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Vigano, P. Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgioti, C.; Preza, O.; Panourgias, E.; Chatoupis, K.; Antoniou, A.; Nikolaidou, M.E.; Moulopoulos, L.A. MR imaging of endometriosis: Spectrum of disease. Diagn Interv Imaging 2017, 98, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechsner, S.; Weichbrodt, M.; Riedlinger, W.F.; Bartley, J.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Schneider, A.; Kohler, C. Estrogen and progestogen receptor positive endometriotic lesions and disseminated cells in pelvic sentinel lymph nodes of patients with deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod 2008, 23, 2202–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourial, S.; Tempest, N.; Hapangama, D.K. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med 2014, 2014, 179515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamceva, J.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisenblat, V.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Farquhar, C.; Johnson, N.; Hull, M.L. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 2, CD009591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasar, P.; Ozcan, P.; Terry, K.L. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 2017, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.J.; Steege, J.F. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol 1996, 87, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkatout, I.; Mettler, L.; Beteta, C.; Hedderich, J.; Jonat, W.; Schollmeyer, T.; Salmassi, A. Combined surgical and hormone therapy for endometriosis is the most effective treatment: prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013, 20, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Clemenza, S.; Rossi, M.; Petraglia, F. Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzewuska, A.M.; Zybowska, M.; Sajkiewicz, I.; Spiechowicz, I.; Zak, K.; Abramiuk, M.; Kulak, K.; Tarkowski, R. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists-A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment? J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, V.; Kim, J.J.; Benbrook, D.M.; Dwivedi, A.; Rai, R. Therapeutic options for management of endometrial hyperplasia. J Gynecol Oncol 1015, 27, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavone, M.E.; Bulun, S.E. Aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2012, 98, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, A.E. Dienogest in long-term treatment of endometriosis. Int J Womens Health 2011, 3, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasagawa, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Nagaoka, T.; Tokado, H.; Imada, K.; Mizuguchi, K. Dienogest, a selective progestin, reduces plasma estradiol level through induction of apoptosis of granulosa cells in the ovarian dominant follicle without follicle-stimulating hormone suppression in monkeys. J Endocrinol Invest 2008, 31, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, A.; Sato, T.; Ohta, Y.; Buchanan, D.L.; Iguchi, T. Effect of diethylstilbestrol on cell proliferation and expression of epidermal growth factor in the developing female rat reproductive tract. J Endocrinol 2001, 170, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuki, Y.; Takano, Y.; Futamura, Y.; Shibutani, Y.; Aoki, D.; Udagawa, Y.; Nozawa, S. Effects of dienogest, a synthetic steroid, on experimental endometriosis in rats. Eur J Endocrinol 1998, 138, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsumi, H.; Kitawaki, J.; Tanaka, K.; Hosoda, T.; Honjo, H. Lack of stimulatory effect of dienogest on the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 by endothelial cell as compared with other synthetic progestins. Maturitas 2002, 42, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, S.; Harada, T.; Mitsunari, M.; Taniguchi, F.; Iwabe, T.; Terakawa, N. Progesterone and progestational compounds attenuate tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced interleukin-8 production via nuclear factor kappa B inactivation in endometriotic stromal cells. Fertil Steril 2005, 83, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraglia, F.; Hornung, D.; Seitz, C.; Faustmann, T.; Gerlinger, C.; Luisi, S.; Lazzeri, L.; Strowitzki, T. Reduced pelvic pain in women with endometriosis: efficacy of long-term dienogest treatment. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011, 285, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momoeda, M.; Harada, T.; Terakawa, N.; Aso, T.; Fukunaga, M.; Hagino, H.; Taketani, Y. Long-term use of dienogest for the treatment of endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2009, 35, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Shackleton, O.J. Pozo, J. Marcos, GC/MS in Recent Years Has Defined the Normal and Clinically Disordered Steroidome: Will It Soon Be Surpassed by LC/Tandem MS in This Role?, Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2 (2018) 974–996. [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, Lina et al. “Human steroid biosynthesis, metabolism and excretion are differentially reflected by serum and urine steroid metabolomes: A comprehensive review.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology vol. 194 (2019): 105439. [CrossRef]

- V. Rousson, D. Ackermann, B. Ponte, M. Pruijm, I. Guessous, C.H. D’Uscio, G. Ehret, G. Escher, A. Pechère-Bertschi, M. Groessl, P.-Y. Martin, M. Burnier, B. Dick, M. Bochud, B. Vogt, N.A. Dhayat, Sex- and age-specific reference intervals for diagnostic ratios reflecting relative activity of steroidogenic enzymes and pathways in adults, PLOS ONE. 16 (2021) e0253975. [CrossRef]

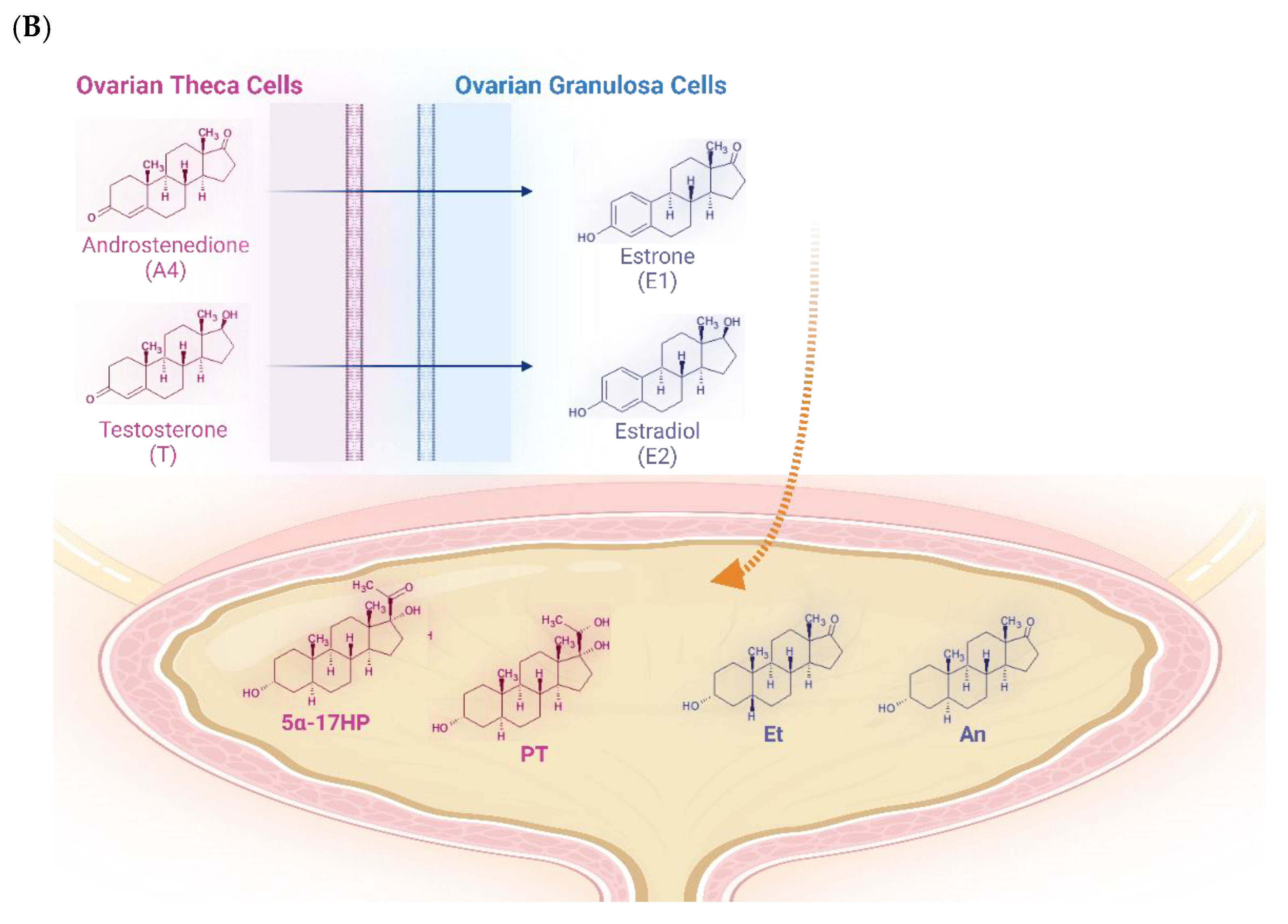

- Wickenheisser, Jessica K et al. “Human ovarian theca cells in culture.” Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM vol. 17,2 (2006): 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Clark, B J et al. “The purification, cloning, and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR).” The Journal of biological chemistry vol. 269,45 (1994): 28314-22.

- N. Strushkevich, F. Mackenzie, T. Cherkesova, I. Grabovec, S. Usanov, H.-W. Park, Structural basis for pregnenolone biosynthesis by the mitochondrial monooxygenase system, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (2011) 10139–10143. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Breen, D.L. Villeneuve, M. Breen, G.T. Ankley, R.B. Conolly, Mechanistic Computational Model of Ovarian Steroidogenesis to Predict Biochemical Responses to Endocrine Active Compounds, Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 35 (2007) 970–981. [CrossRef]

- Hall, P F. “Cytochromes P-450 and the regulation of steroid synthesis.” Steroids vol. 48,3-4 (1986): 131-96. [CrossRef]

- Dhayat, Nasser A et al. “Urinary steroid profiling in women hints at a diagnostic signature of the polycystic ovary syndrome: A pilot study considering neglected steroid metabolites.” PloS one vol. 13,10 e0203903. 11 Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W.L. Miller, R.J. Auchus, The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders, Endocrine Reviews. 32 (2011) 81–151. [CrossRef]

- Murielle Bochud, Belen Ponte, Menno Pruijm, Daniel Ackermann, Idris Guessous, Georg Ehret, Geneviève Escher, Michael Groessl, Sandrine Estoppey Younes, Claudia H d’Uscio, Michel Burnier, Pierre-Yves Martin, Antoinette Pechère-Bertschi, Bruno Vogt, Nasser A Dhayat, Urinary Sex Steroid and Glucocorticoid Hormones Are Associated With Muscle Mass and Strength in Healthy Adults, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 104, Issue 6, June 2019, Pages 2195–2215. [CrossRef]

- Cedric H.L. Shackleton,Mass spectrometry in the diagnosis of steroid-related disorders and in hypertension research, The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Volume 45, Issues 1–3,1993,Pages 127-140,ISSN 0960-0760. [CrossRef]

- Islam MS, Afrin S, Jones SI, Segars J. Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators-Mechanisms and Therapeutic Utility. Endocr Rev. 2020 Oct 1;41(5):bnaa012. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ciloglu, E.; Unal, F.; Dogan, N.C. The relationship between the central serous chorioretinopathy, choroidal thickness, and serum hormone levels. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018, 256, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, S.A.; Edwards, D.P. Mechanism of action of progesterone antagonists. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002, 227, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitruk-Ware, R. New progestogens: a review of their effects in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Drugs Aging 2004, 21, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. S., Weinreb, R. N., Yannuzzi, L., & Jampol, L. M. Mifepristone treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 27 (2007), 119–122. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Jared S MD*†; Jampol, Lee M MD*. Oral mifepristone for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 31(9):p 1928-1936, October 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Robin-Jagerschmidt, J.-M. Wurtz, B. Guillot, D. Gofflo, B. Benhamou, A. Vergezac, C. Ossart, D. Moras, D. Philibert, Residues in the Ligand Binding Domain That Confer Progestin or Glucocorticoid Specificity and Modulate the Receptor Transactivation Capacity, Molecular Endocrinology. 14 (2000) 1028–1037. [CrossRef]

- F. Cadepond, Phd, A. Ulmann, Md, Phd, E.-E. Baulieu, Md, Phd, RU486 (MIFEPRISTONE): Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Uses, Annual Review of Medicine. 48 (1997) 129–156. [CrossRef]

| Day number | Estradiol valerate [mg] | Dienogest [mg] |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 3.0 | 0.0 |

| 3-7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 8-17 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 18-24 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 25-26 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 27-28 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Enzymes and pathways | Ratios | Value | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD17B) | 0.917 | 0.366 – 2.580 | |

| Alternative androgen backdoor pathway vs. classic pathway | 0.859 | 0.400 – 2.100 | |

| 5α-reductase deficiency | 1.164 | 0.470 – 2.400 | |

| 17,20-lyase Δ5-pathway deficiency | 3.480 | 0.028 – 1.880 | |

| 1.980 | 0.166 – 5.510 | ||

| 1.440 | 0.0229 – 1.870 | ||

| 0.670 | 0.0097 – 0.555 | ||

| P450c17 global Δ4 vs. Δ5-pathway | 15.21 | 0.147 -6.20 | |

| 8.65 | 1.08 – 20.4 | ||

| 0.025 | 0.0376 – 1.140 |

| Analyte or ratio | N | Reference interval |

|---|---|---|

| E1 | 36 | 2.00 – 15.00 |

| 36 | 0.20 – 3.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).