Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

- -

- completeness: ascertaining the availability of a witness to the trueness of a statement

- -

- soundness: where a falsifier fails to prove the content of a statement or computation

- -

- zero- knowledge: the verifier only confirms the truism of a statement and nothing else.

- -

- scalability: the computing power of algorithms must be constantly increased to function at a high level after it has been dispensed.

- -

- restriction: all data is lost when the prover or creator of a transaction loses their personal information

- -

- demand more computing power: there are 2000 possible calculations per ZKP transaction, and they require individual and specified number of processing time - unavailability of standards, unified language, and systems to enable developers to leverage the full potential of ZKP.

3. Statement of Problem

4. Justification of Study

5. Aim of the Study

6. Objectives of the Study

- -

- To explore how zero-knowledge proofs can enhance voting transparency in the Catalyst voting process

- -

- To investigate how ZKPs can protect voter privacy and prevent vote disclosure and manipulation

- -

- To develop a scalable solution that can be integrated into the Catalyst voting process

- -

- To identify ZKP-based protocols that are most suitable for the catalyst voting process

- -

- To assess how to design a decentralised and secure voting system that utilises ZKPs for enhanced transparency and voter privacy.

7. Research Hypotheses

8. Literature Review

8.1. Theoretical Review

8.2. Blockchain-Based Voting Systems and Zero Knowledge Proof

8.3. Empirical Evidence

9. Methodology

- A multivocal literature review: this was first used to review available literature on the challenges of the transparency and privacy dilemma of blockchain technology, and to comprehensively analyse the operational frameworks and applications of various zero-knowledge proof protocols to determine their potential application in the catalyst voting process. This method is relevant because aside being exploratory and expository, it enabled the researchers to understand nuances and conversations around embedding ZKP in blockchain ecosystems for voting, which also aligns the objectives of this study to the roadmap, hence enhancing the precision and accuracy of the research findings.

- The study also utilised a survey questionnaire sent out to 100 people in the Cardano blockchain ecosystem, to investigate the opinions of the potential users of the application of ZKP-based blockchain ecosystem in the Catalyst voting system. The participants of the survey were members of the Cardano community, who are very familiar with the Catalyst voting process, understand the challenges of the traditional voting system, and seek an innovation that can enhance the transparency of voting, maintain privacy of specific information in the process and improve the efficiency of the voting system.

- ▪

-

An architectural mock-up of the ZKP-based voting integrity system. This system conceptualised the voting protocol using ZKP which ensures that a user’s voting eligibility is validated without disclosing sensitive information, such as the number of ADA tokens held. It maintains voter privacy and prevents undue influence from larger ADA holders. The design aims to enhance transparency within the voting process while protecting individual privacy and preventing vote manipulation. To achieve this, an interview was carried out with the community members and four suggestions for protocol changes were made. These suggestions are categorised into two:

- -

- voting methodology change including one-on-one voting system and ZKP-scaled/tiered voting

- -

- process change including the replacement of the traditional snapshot process (prior to Fund 12, requiring 500 ADA and a fixed snapshot date) with instant voting, and real-time tallying, validation and release of results.

- →

- A Real time one-on-one Validation voting system where each user votes individually with their validated voting power. Here, the Voter Identification Module uses ZKP to confirm eligibility before allowing the vote. This is achieved by ensuring that each voter’s wallet contains the specific amount of ADA tokens required to vote in a particular session. For instance, say the eligibility criteria to vote a proposal is the voting threshold of 500 tokens, the Voters Identification Module confirms that eligible voters hold up to that number of tokens, without revealing the total amount of tokens they have in their wallet, then for each voting session conducted by voter it records the voting at that instance, eliminating the need for snapshots and the manipulation that goes on in there. That way, each vote is counted fairly without external influence. This voting system also facilitates better decisionmaking in a decentralised platform, fostering a more nuanced understanding of voter preferences while ensuring that the best proposals are selected for funding and development.

- →

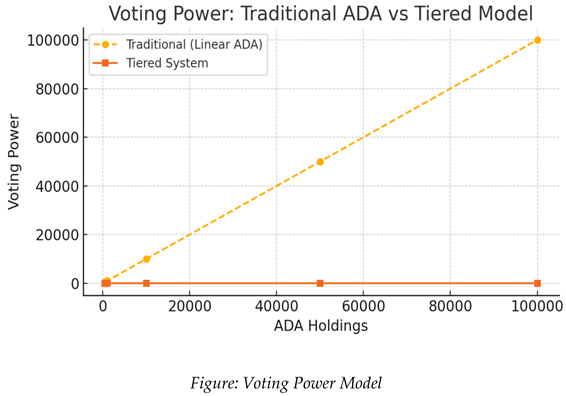

- A ZKP-scaled/tiered voting system whereby users are assigned a range of votes based on their holdings, validated through ZKP. The system assesses the user’s range and allocates votes accordingly while maintaining confidentiality. It balances power among users, by allowing people with more range to maintain their voting power, at the same time preventing them from influencing the voting outcome.

- ➢

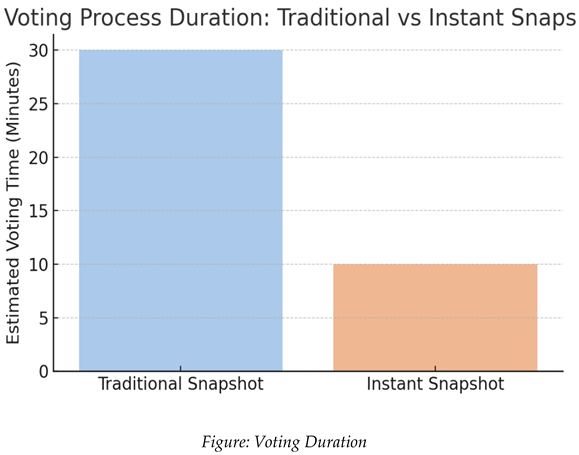

- Replacement of the traditional snapshot process (prior to Fund 12, requiring 500 ADA and a fixed snapshot date) with instant voting, allowing users to vote anytime during the open voting window, with ZKP validating their voting power dynamically. Each vote is verified through ZKP at the time of casting, preventing pre-knowledge of voting power and vote buying. This process leverages Cardano’s eUTxO model, where ZKP ensures real-time eligibility with a proof generation time T prove= k · n ·log(n) + c, where n is the number of constraints (e.g., 1,000 per vote), k is a constant (e.g., 10), and c is overhead (e.g., 2 seconds). This reduces latency to T verify<1 s, eliminating the need for a fixed snapshot and enabling flexible participation.

- ➢

- Real-time validation and tallying, whereby, in the event of the conclusion of the voting, votes are tallied as they are cast, using ZKP to ensure accurate and secure verification. This system synchronises with either the one-on-one voting or ZKP-scaled/tiered voting systems to tally the votes, followed by results being updated almost immediately. This provides transparency and instant feedback to voters, fostering trust in the electoral process.

- ★

- Cryptographic complexity which can be encountered due to the difficulty in applying or implementing the ZKP-based voting integrity assurance which relies heavily on advanced cryptographic models and techniques requiring correctness and security to meet the goal of privacy and ensure that the entire voting system is safe from attacks.

- ★

- The platform may be difficult to scale because it is tasked to operate when millions of voters are involved as the system generates and verifies zero-knowledge proofs per user via computation.

- ★

- Ballot anonymity involves the balance of the computational dilemma of maintaining both confidentiality of voters and at the same time verifying their identity.

- ★

- Ensuring that usability and accessibility of the platform is simplified, because building a system that is easy for users to operate and does not discriminate against eligible voters to bridge voters inequality gap, is practically difficult.

- ★

- Others include ensuring trust and transparency; being able to cooperate with other voting infrastructures including voter registration databases and vote counting processes; allowing independent verification and auditing of both the integrity of the electoral process and election results respectively; resilient to attacks such as denial-of-service attacks, network interruptions, and guesses to manipulate data; ensuring legal and regulatory compliance to international standards of authority across jurisdictions; and convincing the voters and relevant stakeholders to adopt this system even with the possibility of a resistance to change.

10. Results and Findings

10.1. Introduction

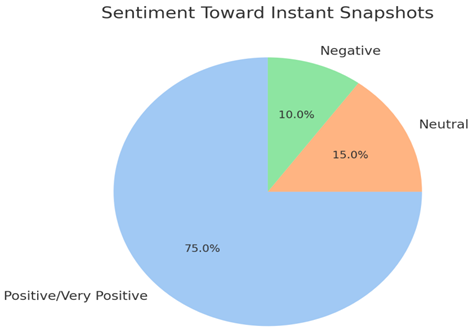

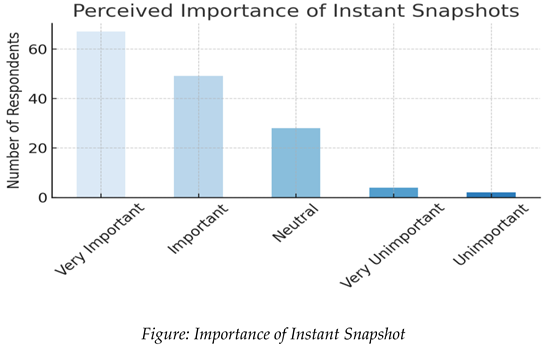

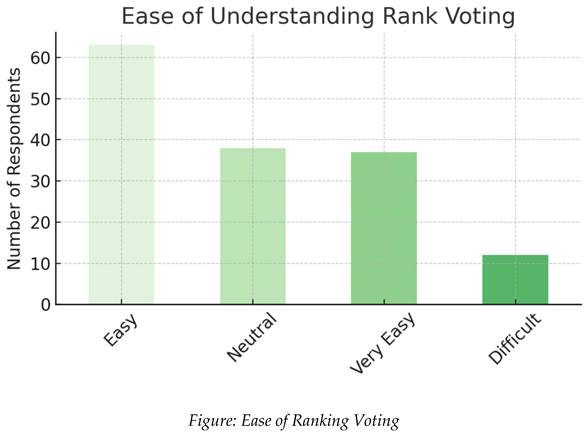

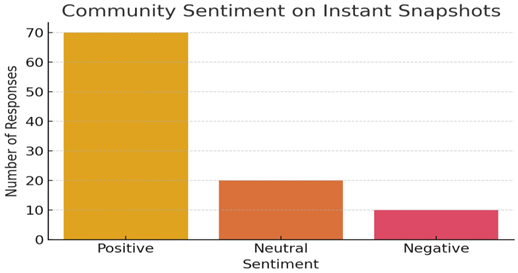

10.2. Analysis of Responses on Instant Snapshots and ZKP Validation

10.2.1. User Feedback on Instant Snapshots:

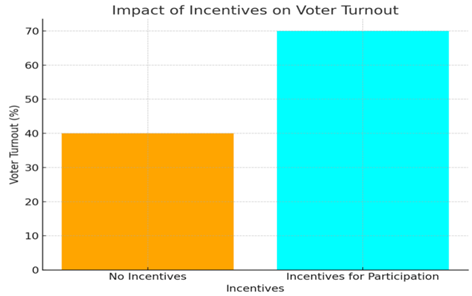

10.2.2. Likelihood of Participation:

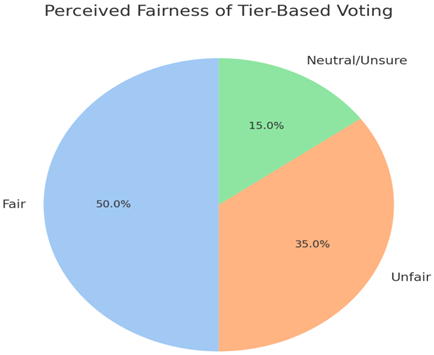

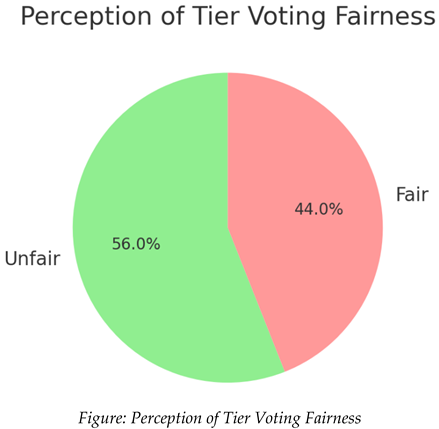

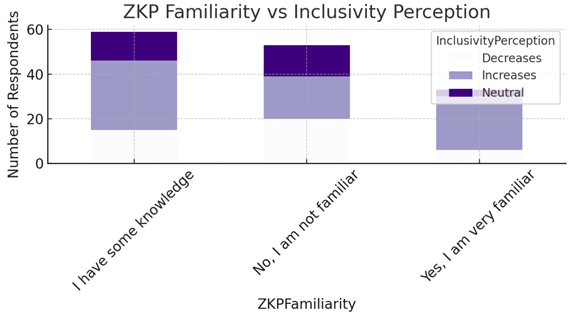

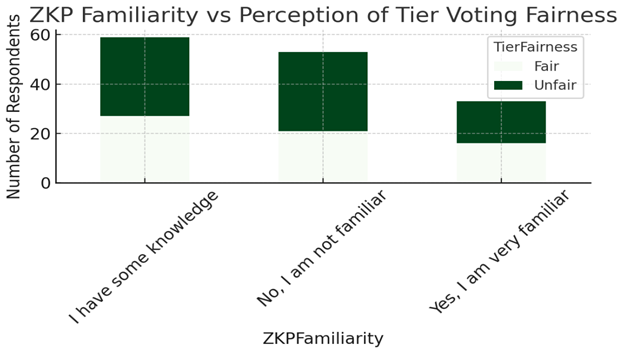

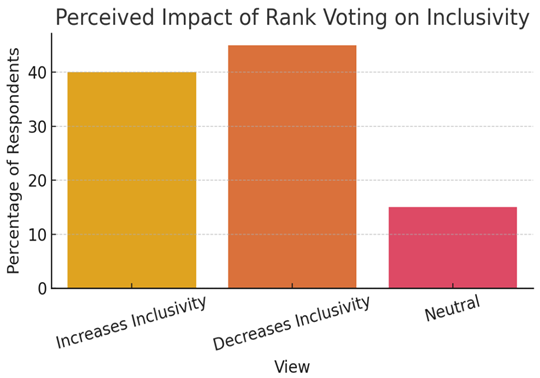

10.3. Analysis of ZKP-Scaled/Tiered Voting

10.3.1. Proportional Voting Based on ADA Holdings:

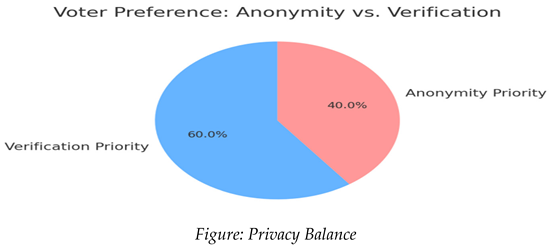

10.3.2. ZKP-Based Instant Voting and Personalized Validation:

10.4. Catalyst 1% Parameter and ZKP-Scaled/Tiered Voting

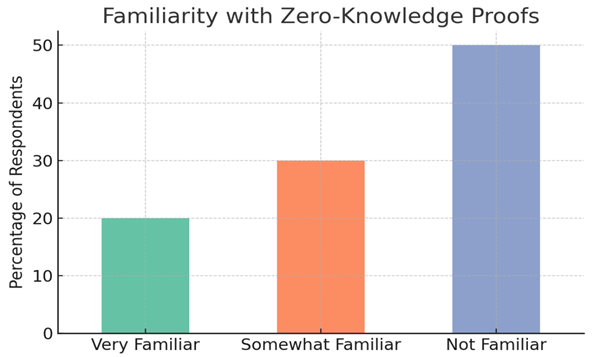

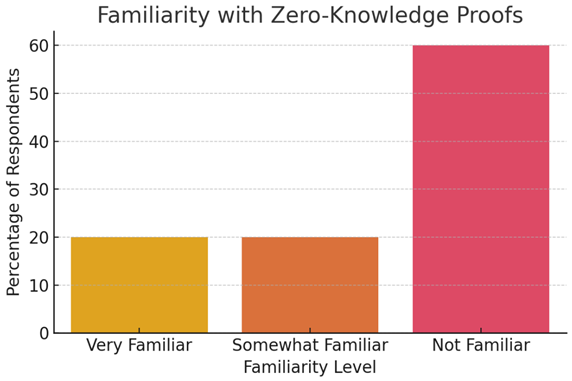

| Level | Respondents (%) |

| Very Familiar | 20% |

| Somewhat familiar | 30% |

| Not familiar | 50% |

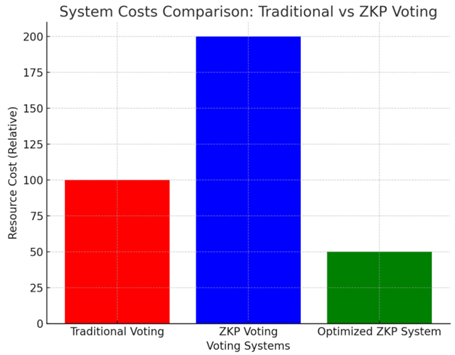

| Metric | Traditional Snapshot | ZKP-Based Snapshot |

| Snapshot Timing | Periodic (delayed) | Real-time (instant) |

| Voter Trust Rating | Medium (varied) | High (70–75%) |

| Fraud/Manipulation Risk | Higher | Lower (ZKP audit trail) |

| Result Availability | Delayed (post-tally) | Instant (live tally) |

| Factor | Rank Voting (Tiered) | 1:1 Equality (Flat) |

| Inclusivity (Perceived) | Divided (45% say reduced) | High (equal voice) |

| Decentralization | Conditional on tiers | High, but risks vote dilution |

| Stakeholder Influence | Proportional to ADA | Uniform regardless of holdings |

| Privacy Balance | Supports ZKP verification tiers | Easier to implement anonymously |

- Sentiment on Instant Snapshots

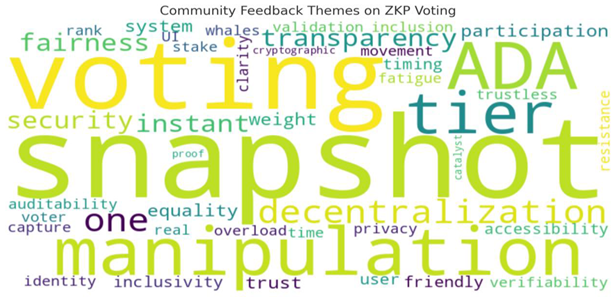

10.5. Additional Findings

11. Discussion

12. Summary, Recommendations and Conclusion

12.1. Implications of Enhancing Voting Transparency in the Catalyst Voting Process

12.2. Operational and Feasibility Frameworks of the ZKP-Based Voting Platform

12.3. Designing a Decentralised and Secure Voting Platform

12.4. Recommendations

12.5. Conclusions

References

- Aleo — revolutionizing blockchain with Zero-Knowledge Proofs. Available at: https://medium.com/@ur4ix/aleo-revolutionizing-blockchainWith-zero-knowledge-proofs-ec307abe088a.

- Chi, P.W., Lu, Y.H. and Guan, A., 2023. A privacy-preserving zero knowledge proof for blockchain. IEEE Access.

- Feng, T., Yang, P., Liu, C., Fang, J. and Ma, R., 2022. Blockchain data privacy protection and sharing scheme based on zero-knowledge proof. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022, pp.1-11.

- Han, M., Yin, Z., Cheng, P., Zhang, X. and Ma, S., 2020. Zero-knowledge identity authentication for internet of vehicles: Improvement and application. Plos one, 15(9), p.e0239043.

- Hasan, J., 2019. Overview and applications of zero knowledge proof (ZKP). International Journal of Computer Science and Network, 8(5), pp.2277-5420. 2277.

- Hryniuk, O., 2023. How is Marlowe different from Plutus. Available online at: https://www.essentialcardano.io/faq/how-is-marlowe-differentfrom-plutus.

- King, S., 2023. Marlowe: Simplifying Financial Smart Contracts on Cardano’s Blockchain. Available online: https://forum.cardano.org/t/marlowe-simplifying-financial-smart-contracts-on-cardanos-blockchain/124320. 1243.

- Li, W., Guo, H., Nejad, M. and Shen, C.C., 2020. Privacy-preserving traffic management: A blockchain and zero-knowledge proof inspired approach. IEEE access, 8, pp.181733-181743.

- Methmal, J., 2023. Zero Knowledge Proofs: A Comprehensive Review of Applications, Protocols, and Future Directions in Cybersecurity. [CrossRef]

- Panja, S. and Roy, B.K., 2018. A secure end-to-end verifiable e-voting system using zero knowledge based blockchain. Cryptology ePrint Archive.

- Partala, J., Nguyen, T.H. and Pirttikangas, S., 2020. Non-interactive zero-knowledge for blockchain: A survey. IEEE Access, 8, pp.227945227961.

- Prasad, S., Tiwari, N., Chawla, M. and Tomar, D.S., 2024. ZeroKnowledge Proofs in Blockchain-Enabled Supply Chain Management. In Sustainable Security Practices Using Blockchain, Quantum and PostQuantum Technologies for Real Time Applications (pp. 47-70). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Principato, M., Babel, M., Guggenberger, T., Kropp, J. and Mertel, S., 2023. Towards Solving the Blockchain Trilemma: An Exploration of Zero-Knowledge Proofs.

- Pruden, A., 2021. The future of zero-knowledge with Aleo. Available at: https://aleo.org/post/the-future-of-zero-knowledge-with-aleo/.

- Sanjaya, M.D., 2021. A Blockchain Based Approach for Secure E-Voting System (Doctoral dissertation).

- Sedlmeir, J., Völter, F. and Strüker, J., 2021. The next stage of green electricity labeling: using zero-knowledge proofs for blockchain-based certificates of origin and use. ACM SIGENERGY Energy Informatics Review, 1(1), pp.20-31.

- Twenhoven, T., 2023. Trust, But Verify: Potentials for Zero Knowledge Proofs in Supply Chain Management. Zoom Research Seminar / 5th Floor EE Lecture 2. Available online at: https://www.klu.org/event/trustbut-verify-potentials-for-zero-knowledge-proofs-in-supply-chain-management.

- Tyagi, S. and Kathuria, M., 2022, May. Role of Zero-Knowledge Proof in Blockchain Security. In 2022 International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COM-IT-CON) (Vol. 1, pp. 738-743). IEEE.

- VanticaTrading, 2023. What is Midnight, Cardano’s Privacy Sidechain? Available online at: https://www.vanticatrading.com/post/what-ismidnight-cardano-s-privacy-sidechain.

- Xu, X., 2024. Zero-knowledge proofs in education: a pathway to disability inclusion and equitable learning opportunities. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), p.7.

- Yang, X. and Li, W., 2020. A zero-knowledge-proof-based digital identity management scheme in blockchain. Computers & Security, 99, p.102050.

- Zero-knowledge Proofs: An Intuitive Explanation. Available online at: https://minaprotocol.com/blog/zero-knowledge-proofs-an-intuitiveexplanation#::text=The%20purpose%20of%20zero%2Dknowledge,without%20giving%20them%20the%20solution.

- Zhou, L., Diro, A., Saini, A., Kaisar, S. and Hiep, P.C., 2024. Leveraging zero knowledge proofs for blockchain-based identity sharing: A survey of advancements, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 80, p.103678.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).