1. Introduction

Faced with depleting global resources, Taiwan, which is surrounded by seas, needs to efficiently utilize resources. In particular, water resources, ecosystems, and air pollution are significant issues [

1,

2]. Modern society has become a plastic-focused culture, with the use of plastics far surpassing that of other materials, such as ceramics, metals, and glass [

3]. Commonly employed plastics in daily life include polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and bioplastic polylactic acid (PLA) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. If household waste plastics could be used as fine aggregate replacements in cement products [

10,

11,

12,

13] or incorporated as fibre materials [

14,

15,

16], this would significantly reduce the dependence on natural resources and thereby decrease their consumption. However, current research on incorporating household waste plastics into cement products primarily focuses on the inclusion of expanded polystyrene (EPS) [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

In recent years, technological products have continued to advance, and TVs, as part of daily life, are being updated continuously with technology. Many outdated TVs are being eliminated and becoming domestic waste. How to dispose of domestic waste has become challenging for various countries. There are many TVs that can be broken down at environmental protection stations. During the process of dismantling television waste, particularly the back covers of cathode ray tube (CRT) televisions, large quantities of high-bromine polystyrene (PS) plastic are produced. As the number of CRT televisions being dismantled increases annually, the amount of recovered brominated PS plastic also increases. However, the brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in these plastics are difficult to degrade in the environment and possess bio accumulative properties, posing potential environmental hazards [

22].

In addition, the external parts of the TV are made of HDPS plastic products, which can be utilized after melt spinning but increase carbon emissions. These materials can be reused before melting to reduce carbon emissions [

23,

24,

25]. The continuous development of TV technology has led to the disposal of outdated TVs in many countries. Civil engineering materials have been oriented to green renewable resources and sustainable development [

26,

27,

28]. If domestic plastic waste can be added to cement mortar or replace fine aggregates, the use of natural sand can be reduced effectively, and thus, the consumption of natural resources can be reduced. In recent years, the number of discarded TV sets has increased significantly. According to

Table 1, due to the rapid changes in science and technology in the past ten years, discarded electronic equipment has become one of the fastest-growing special wastes worldwide [

29]. Larger and thinner TV sets have become the main products, and old sets are replaced with new sets, resulting in a large amount of recyclable waste (mainly from factories and residences) [

30]. The demand for TVs has increased significantly in recent years, from 1,181 tons in 2013 to 30,560 tons in 2022. TVs are divided into internal electronic parts and external TV shells [

31]. The TV shells can be processed into recycled plastic pellets by granulation plants and used as recycled plastic materials to implement resource recycling. Previous studies have indicated that adding materials with different physical properties to traditional blends has advantages [

32,

33].

However, these materials must be economically feasible and align with comfort and sustainability criteria [

34,

35,

36]. Some researchers have attempted to incorporate such TPSW materials into concrete specimens to replace coarse aggregates [

37,

38] or partially replace fine aggregates to produce cement mortar, analysing its compressive properties and establishing stress‒strain models [

39]. Nonetheless, prior research results are not comprehensive and lack a thorough analysis of the engineering properties and feasibility of using waste PS television housing as a fine aggregate replacement in cement products. This study used TPSW as a fine aggregate to investigate the fresh properties, engineering properties, and durability of cement mortar made from TPSW with different variables. Their relationships were further established to discuss the influence of different factors (W/C, substitution amount, and age) on the engineering properties of cement mortar.

3. Results and Analysis

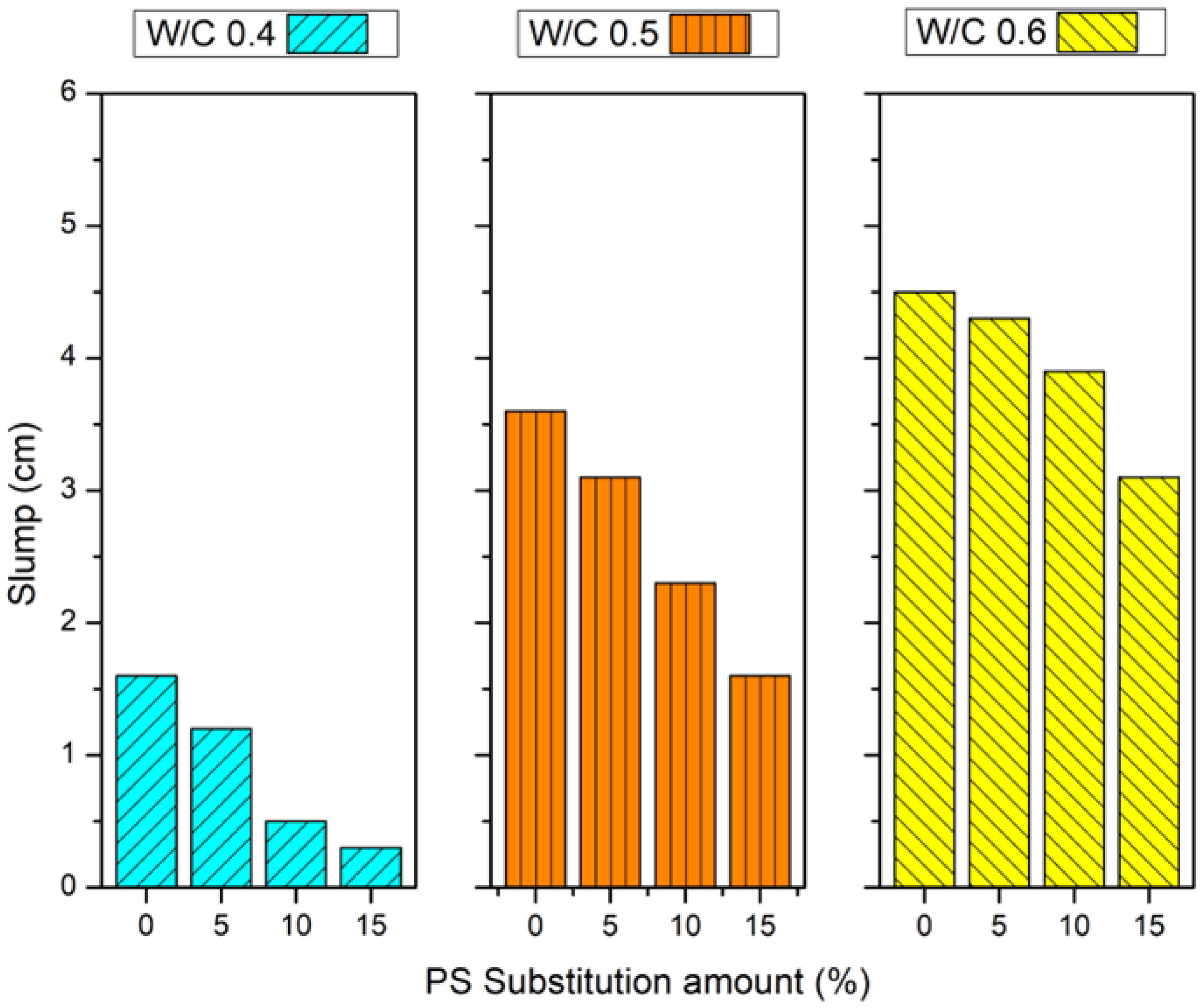

3.1. Slump

Figure 2 shows the slump of the cement mortar made by replacing sand with TPSW and that the slump of the control group (0%) is 81.3% lower than that of the 15% TPSW group when the W/C is 0.4. When the W/C increases from 0.4 to 0.5, the slump of the control group is 55% lower than that of the 15% experimental group. When the W/C increases from 0.5 to 0.6, that of the control group is 31% lower than that of the 15% experimental group. When the W/C increases, the slump tends to increase because the increase in water content reduces the cohesion of the paste and increases the slump, and the overall workability and fluidity of the cement mortar increase. Overall, the slump decreases as the amount of TPSW added increases. When the W/C increases, the overall slump increases as the water content increases, so the W/C has a greater impact on the slump than does the substitution amount.

As shown in

Figure 2, the slump decreases significantly as the proportion of TPSW materials replacing sand increases. When the water-cement ratio is 0.4, the slump decreases by 25%, 68.8%, and 81.3% for substitution amounts of 5%, 10%, and 15%, respectively. For a water-cement ratio of 0.5, the slump decreases by 13.9%, 36.1%, and 55.6%, respectively. At a water-cement ratio of 0.6, the slump decreases by 4.4%, 13.3%, and 31.1% for the same substitution levels. These findings are consistent with other studies [

38], and the reduction in slump can be attributed to the flaky shape of TPSW material, which does not perform as well as coarse aggregate. While increasing the substitution amount reduces the slump, the research results indicate that the water-cement ratio has a greater impact on slump than the substitution amount.

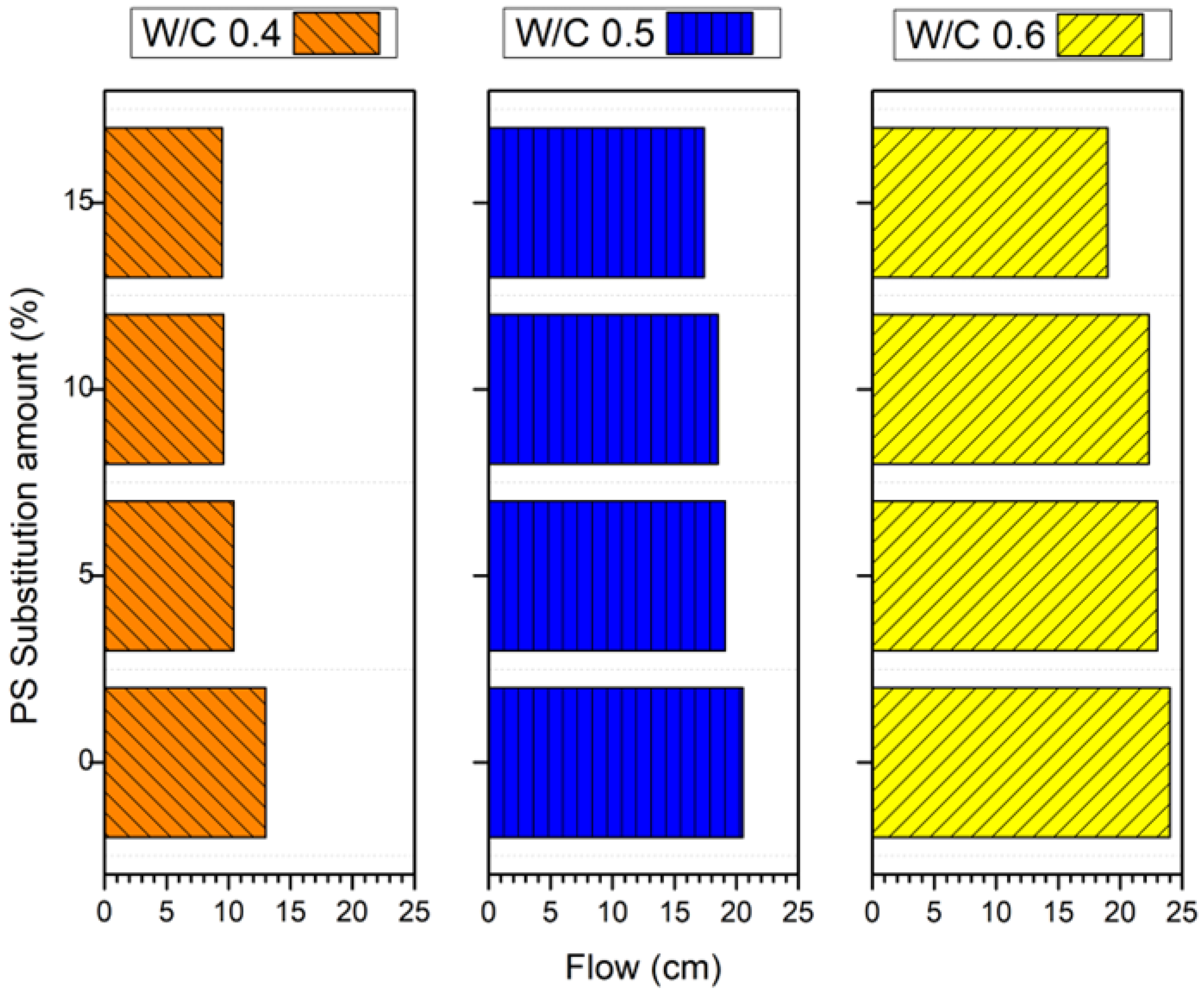

3.2. Slump Flow

Figure 3 shows a comparison of the slump flow of three W/C cement mortars with partial sand replaced by TPSW. The replacement of TPSW for partial sand is fixed at 5% when the W/C is 0.4, the slump flow is 10.4 cm, and when the W/C increases from 0.4 to 0.5, the slump flow is 19.1 cm. When the W/C increases from 0.5 to 0.6, the slump flow is 23 cm. Research shows that the slump flow decreases as the waste PS substitution amount increases and the overall workability decreases. When the W/C increases, the slump flow of the paste increases with increasing water content. The W/C had a greater impact on the slump flow than did the substitution amount.

As shown in

Figure 3, the slump flow decreases as the proportion of waste PS materials replacing sand increases. When the water-cement ratio is 0.4, the slump flow decreases from 13 cm to 9.5 cm; at a water-cement ratio of 0.5, it decreases from 20.5 cm to 17.4 cm; and at a water-cement ratio of 0.6, it drops from 24 cm to 19 cm. The rough texture of the waste PS materials reduces the slump flow, leading to decreased workability. However, as the water-cement ratio increases, the slump flow improves due to the higher water content. Overall, the water-cement ratio has a greater effect on slump flow than the substitution amount.

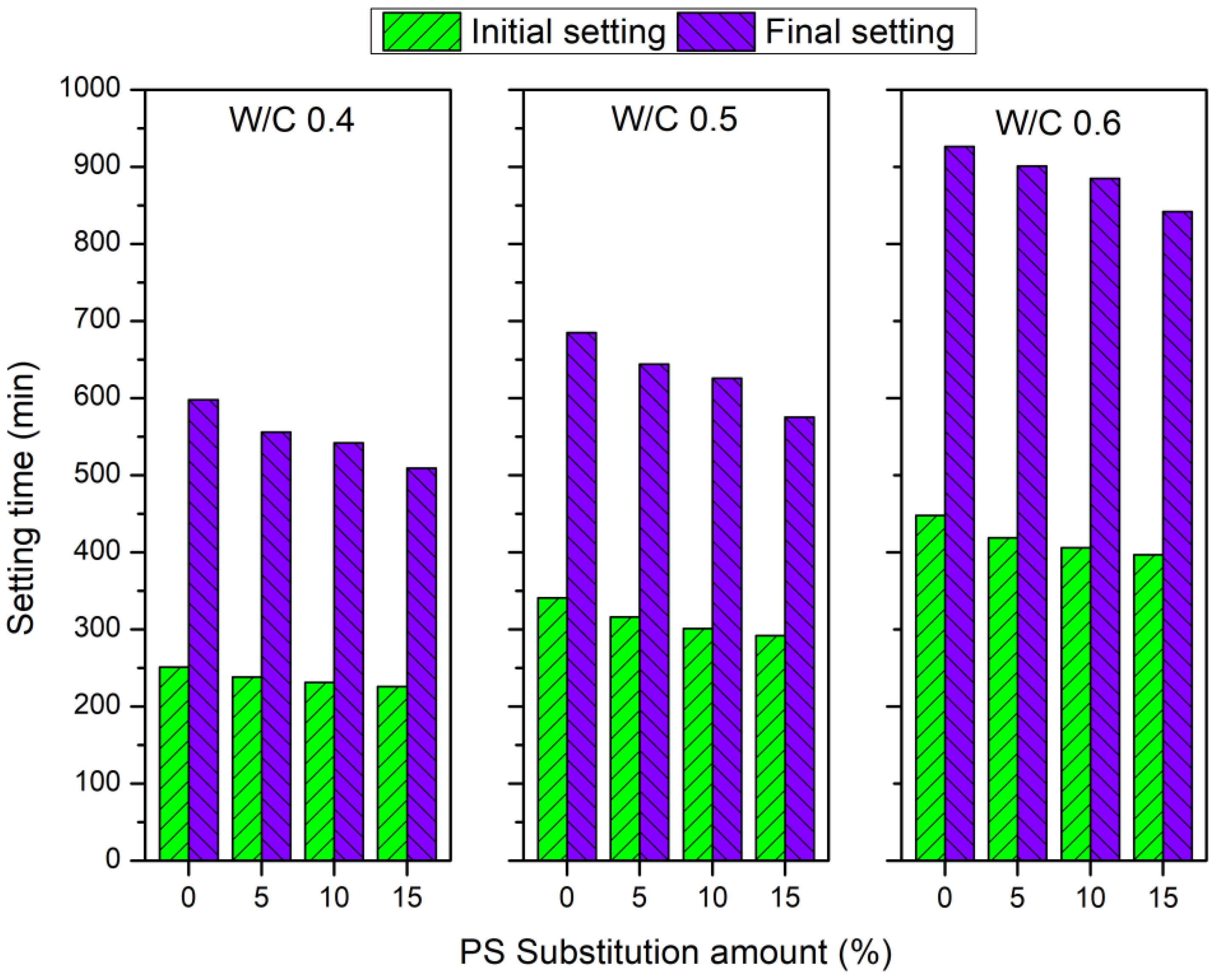

3.3. Setting Time

Figure 4 shows the cement mortar with different TPSW substitution amounts (0%, 5%, 10%, and 15%) and W/C ratios (0.4, 0.5 and 0.6). In the 0% control group, the W/C ratios were 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6, and the initial setting times were 251 min, 341 min, and 448 min, respectively; the final setting times were 598 min, 685 min, and 926 min, respectively. In the 5% TPSW substitution group, the W/C ratios were 0.4, 0.5 and 0.6, and the initial setting times were 238 min, 316 min, and 419 min, respectively; the final setting times were 556 min, 644 min, and 901 min, respectively. In the 10% TPSW substitution group, the W/C ratios were 0.4, 0.5 and 0.6, and the initial setting times were 231 min, 301 min, and 406 min, respectively; the final setting times were 542 min, 626 min, and 885 min, respectively. In the 15% waste PS substitution group, the W/C ratios were 0.4, 0.5 and 0.6, and the initial setting times were 226 min, 292 min and 397 min, respectively; the final setting times were 509 min, 575 min and 842 min, respectively. An increase in the overall water content leads to partial secretion of the cement paste, while the hydration heat reaction slows, prolonging the setting time.

The research results also indicate that as the water-cement ratio increases, the setting time increases correspondingly. This occurs because the higher water-cement ratio leads to increased overall water content, which causes the cement slurry to bleed. As a result, the rate of the hydration reaction slows down, thus prolonging the setting time.

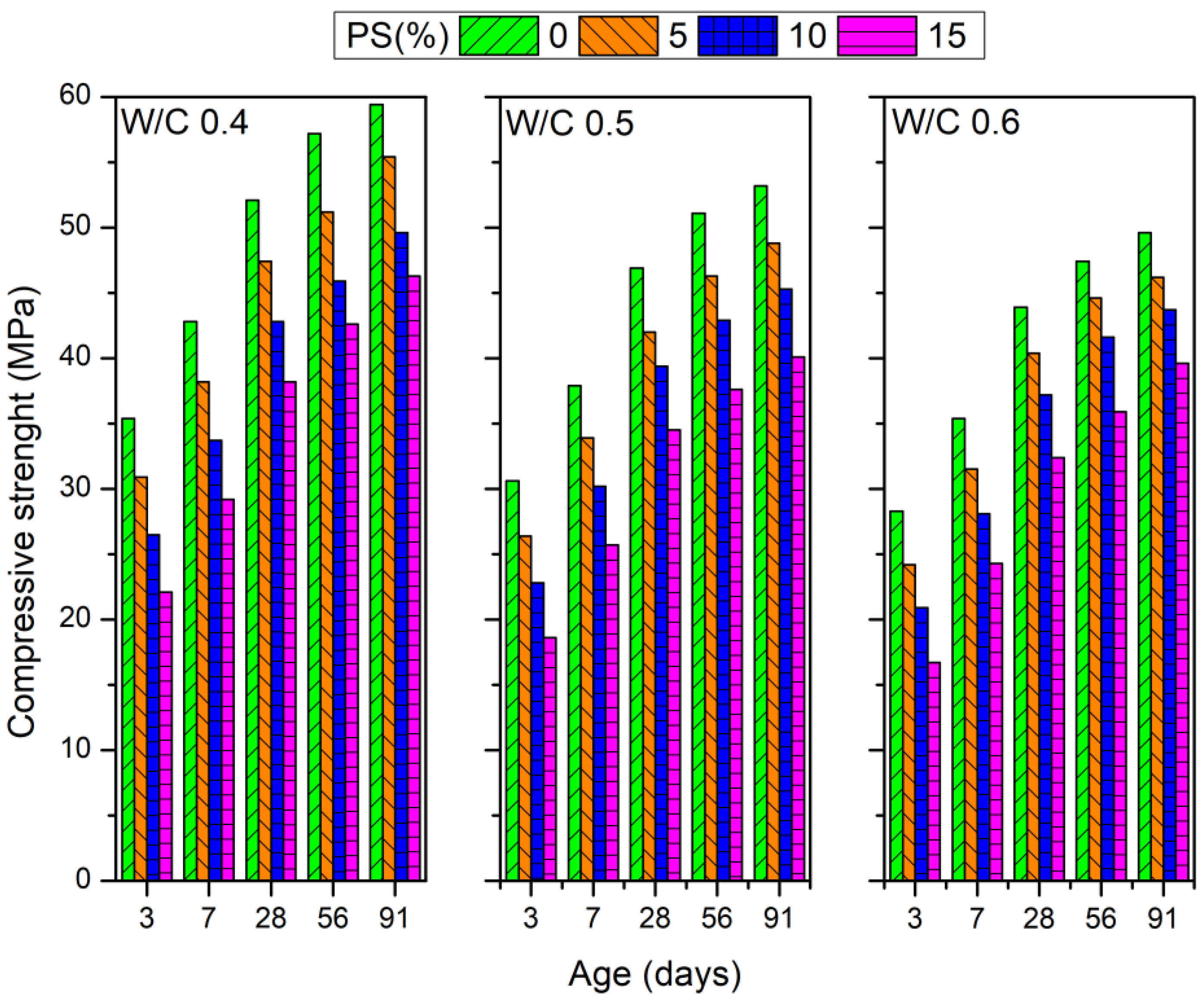

3.4. Compressive Strength

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and

Figure 5 show the impact of different W/C ratios on the development of the compressive strength of cement mortar made by replacing part of the sand with TPSW. The compressive strength decreases as the amount of TPSW increases. When the TPSW substitution amount is fixed at 5% and at a curing age of 28 days when the W/C is 0.4, the compressive strength is 47.5 MPa. When the W/C increases from 0.4 to 0.5, the compressive strength is 42 MPa (-12%). When the W/C increases from 0.5 to 0.6, the compressive strength is 40.4 MPa, which is 15% lower than the W/C of 0.4. If the analysis is based on the substitution amount when the W/C is fixed at 0.5 and at the age of 28 days, the compressive strength of the 0% control group is 46.9 MPa, the compressive strength of the 5% substitution group is 42 MPa (-10%), the compressive strength of the 10% substitution group is 39.4 MPa (-16%), and the compressive strength of the 15% substitution group is 34.5 MPa (-26%). When the water-cement ratio is low, the cementation is stronger and there are fewer pores, leading to an increase in compressive strength. Conversely, an increase in the water-cement ratio results in weaker cementation and more pores, causing a decrease in compressive strength. The results demonstrate that as the water-cement ratio increases, the compressive strength exhibits a consistent downward trend.

When the W/C is fixed at 0.5 and at the age of 91 days, the compressive strength of the control group is 53.2 MPa, the compressive strength of the 5% TPSW substitution group is 48.8 MPa (-8.3%), the compressive strength of the 10% TPSW substitution group is 45.3 MPa (-14.8%), and the compressive strength of the 15% waste PS substitution group is 40.1 MPa (-24.6%). The findings show that as waste PS has lower water absorption than natural sand, there are more water molecules in the specimen, forming many pores and reducing the compressive strength; when the W/C is 0.5 and at the age of 91 days, the strength decreases by 8.3% when the substitution amount is 5%. When the substitution amount exceeds 10%, the strength decreases by more than 10%. It can be inferred that a W/C of 0.5 and a TPSW substitution amount of 5% are most effective in removing waste to attain the goal of waste recycling.

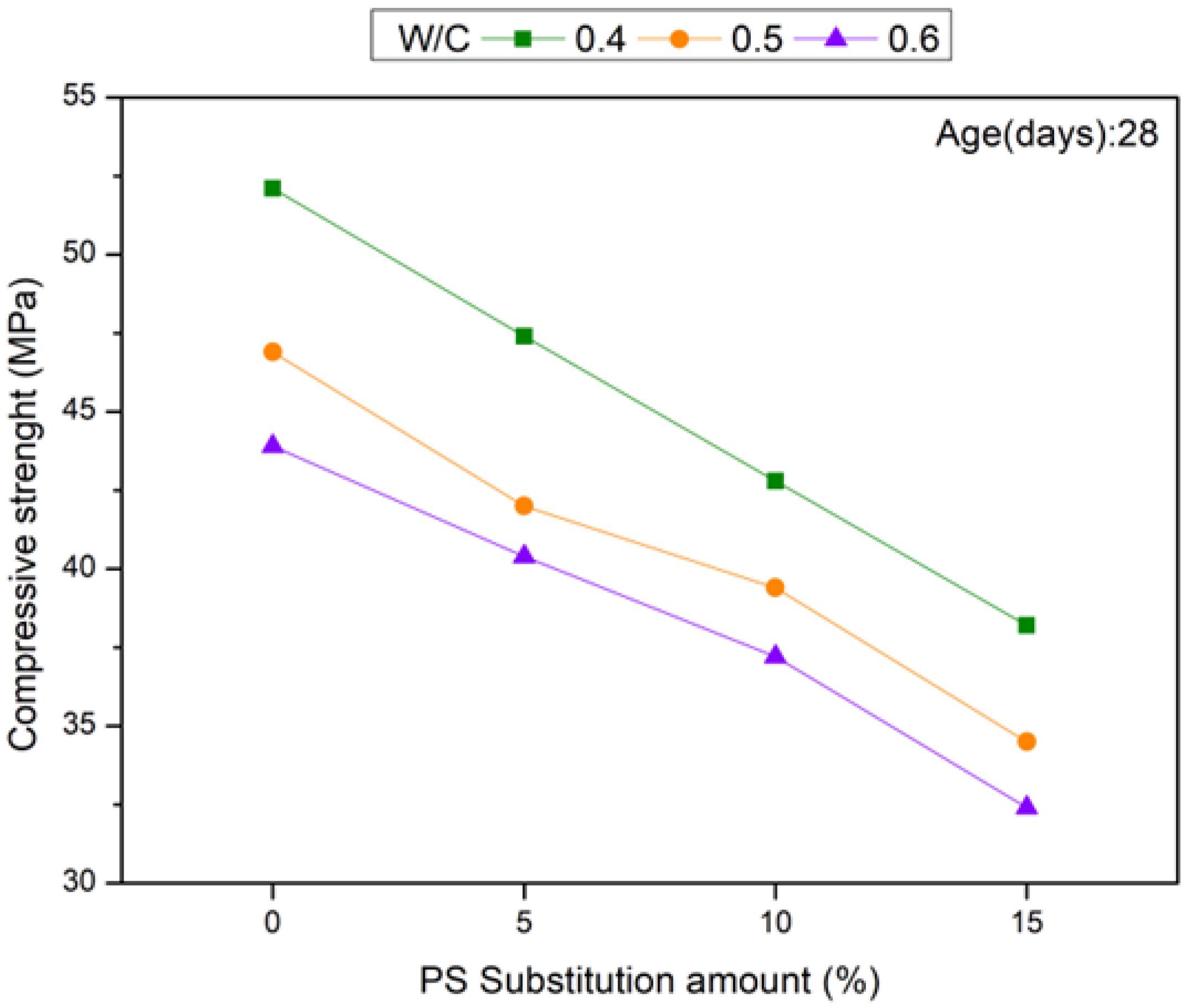

Since the water absorption rate of TPSW material is lower than that of natural sand and gravel, there are more water molecules in the mix, leading to the formation of additional pores, which in turn reduces the compressive strength. As shown in the

Figure 6, under different water-cement ratios (W/C), the compressive strength decreases linearly as the proportion of TPSW increases. The slopes of these three curves are nearly identical, indicating that the reduction in compressive strength is independent of the W/C ratio, which is consistent with previous research findings [

38].

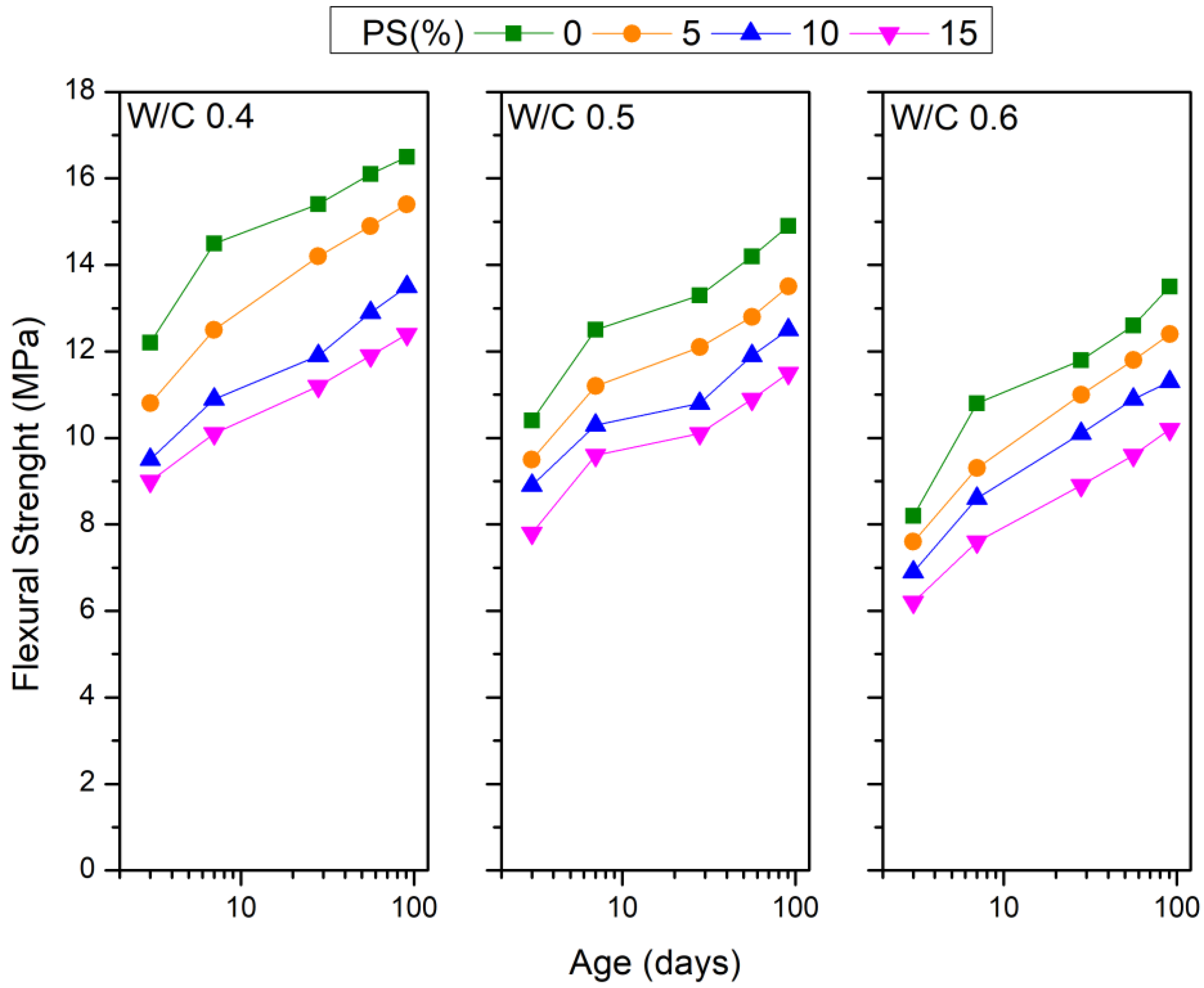

3.5. Flexural Strength

As shown in

Figure 7, when the W/C is 0.4, the flexural strength is 14.2 MPa. When the W/C increases to 0.5, the flexural strength is 12.1 MPa (-15%). When the W/C increases to 0.6, the flexural strength is 11 MPa, which is 9% lower than the W/C of 0.5. When the replacement of TPSW for partial sand is fixed at 5% and at the age of 91 days, when the W/C is 0.4, the flexural strength is 15.4 MPa. When the W/C increases to 0.5, the flexural strength is 13.5 MPa, which is 12.3% lower than the W/C of 0.4. When the W/C increases to 0.6, the flexural strength is 12.4 MPa, which is 8.1% lower than the W/C of 0.5. During the mixing process, as the cement and water are hydrated, the cement paste fills the aggregate pores and cementation occurs. When the W/C is low, the cementation is better, there are fewer pores, and the flexural strength increases.

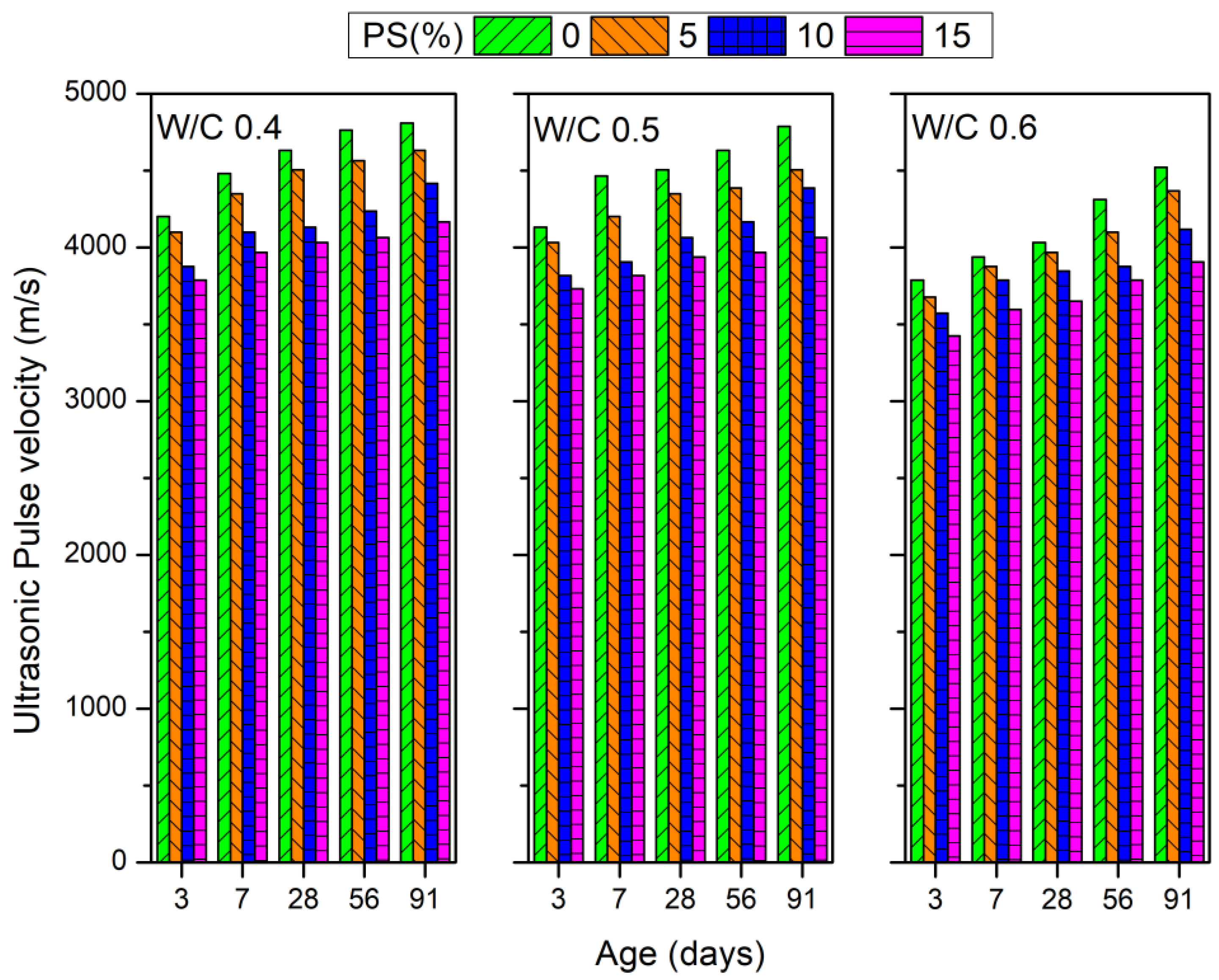

3.6. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity

The effect of adding TPSW to concrete was evaluated using ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), as shown in

Figure 8. With a fixed water-cement ratio of 0.4, the ultrasonic velocity of cement mortar ranged from 3788 m/s to 4630 m/s for substitution amounts between 0% and 15%, measured over 3 to 28 days. At a water-cement ratio of 0.5, the velocity ranged from 3937 m/s to 4505 m/s, and at 0.6, it ranged from 3788 m/s to 4032 m/s. The results show that as the water-cement ratio decreases and the curing age increases, the UPV gradually rises. However, as the substitution amount of TPSW increases, the UPV decreases, reflecting the impact on the mortar’s density.

Despite the decrease, within the studied substitution range, the UPV at 28 days reached 3650 m/s, indicating that the specimens retained good density and strength. As the TPSW content increases, more internal pores form, leading to the reduction in UPV. In summary, lower water-cement ratios and longer curing periods result in higher UPV values, while increased TPSW content tends to lower the UPV due to reduced material density.

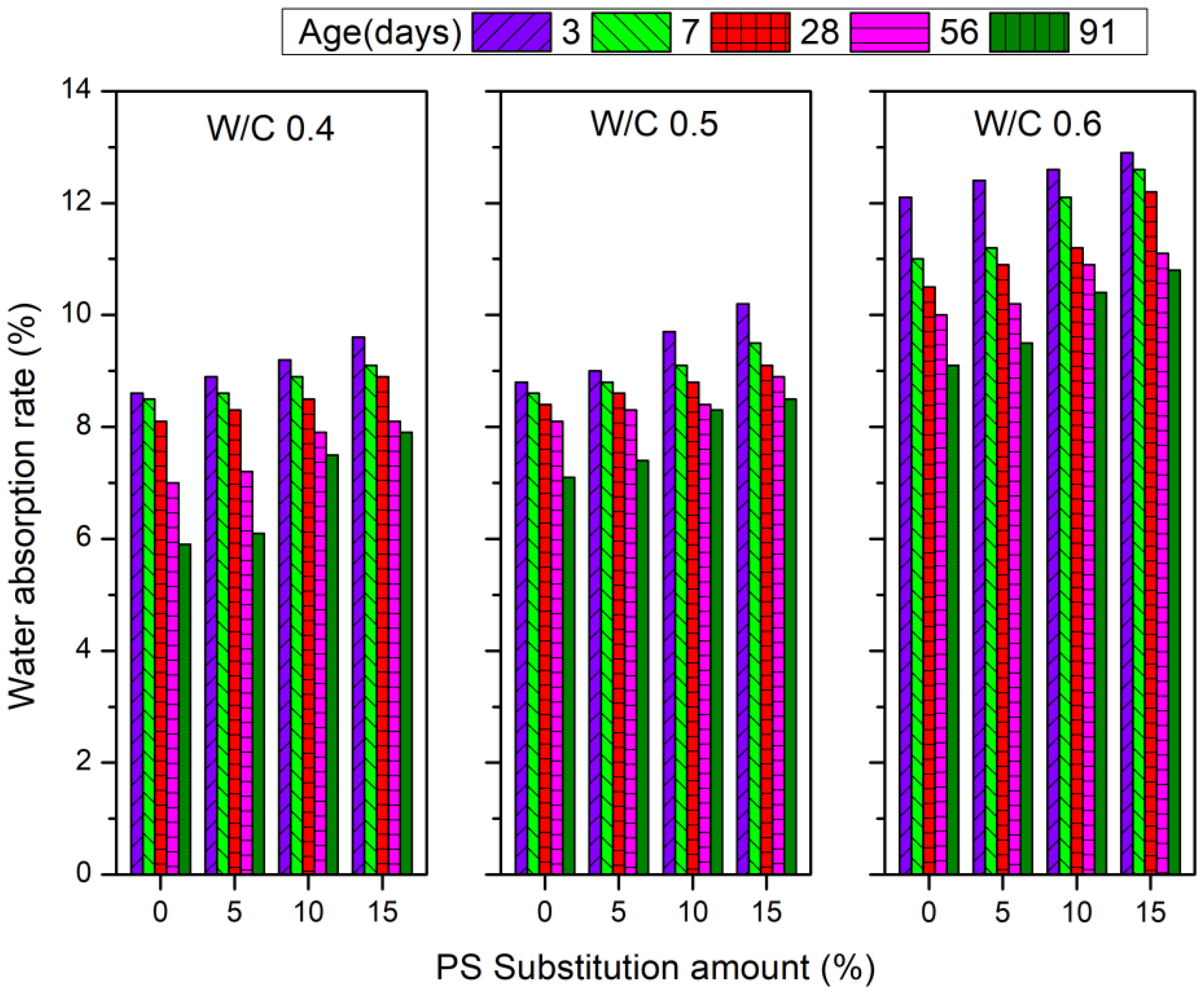

3.7. Water Absorption Rate

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the water absorption of a W/C of 0.5 at different ages (3, 7, 28, 56, and 91 days), and the water absorption decreases as the age increases. As the early hydration is not complete, the specimen is full of pores and is not sufficiently dense. The hydration of the specimen is relatively complete at a curing age of 28 days, and the pores are reduced so that the water absorption decreases. As the substitution amount increases from 0% to 15%, because the TPSW is less water-absorbent than natural sand, there are more water molecules in the specimen and more pores are formed, so the water absorption rate increases.

As the W/C and the amount of TPSW substitution increase, the specimens have more pores, and the number of internal pores increases. At late ages, the water absorption clearly decreases. Water absorption has a relative relationship with ultrasound and strength. The higher the ultrasonic pulse velocity is, the denser the specimen, the lower the water absorption, and the greater the strength.

A higher water absorption rate negatively impacts a material’s durability in humid environments, as excessive absorption can damage its internal structure. This, in turn, affects the material’s load-bearing capacity and shortens its service life. High water absorption may lead to increased pore formation and internal cracking, compromising the material’s overall performance and stability over time.

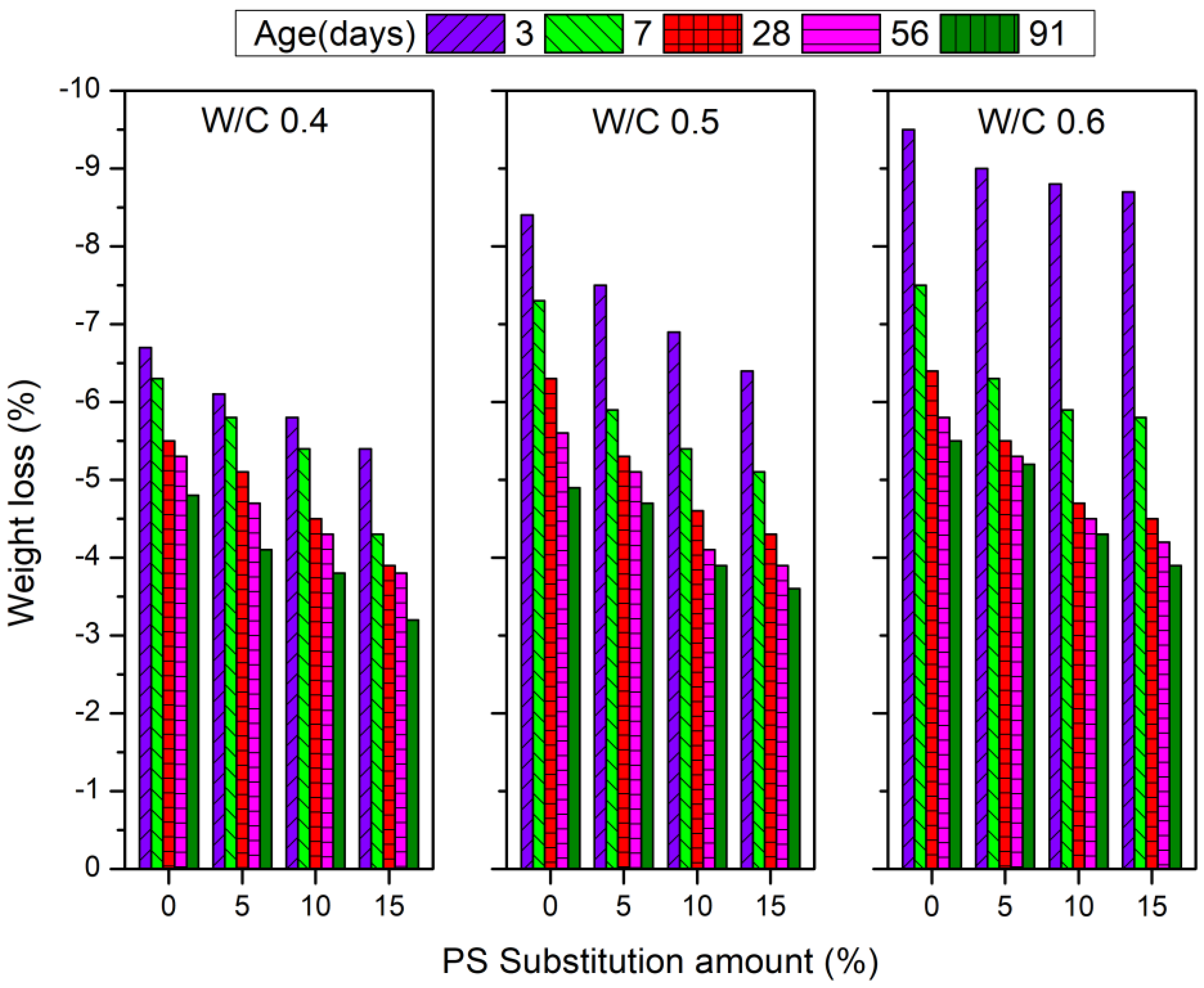

3.8. Resistance to Sulfate Attack

As shown in

Figure 10, when the W/C is fixed at 0.5 and 3 days, the weight loss rates of the cement mortar with substitution amounts of 0%, 5%, 10% and 15% are -8.4%, -7.5%, -6.9% and -6.4, respectively, and the difference between the control group and the substitution amount of 15% is 23.8%. When the age increases from 3 days to 28 days, the losses of the substitution amount (0%, 5%, 10%, and 15%) are -6.3%, -5.3%, -4.6% and -4.3, respectively, the difference between the control group and the substitution amount of 15% is 31.7%, the age is changed from 28 days to 91 days, the loss rates of the substitution amounts of 0%, 5%, 10% and 15% are -4.9%, -4.7%, -3.9% and -3.6%, respectively, and the difference between the control group and the substitution amount of 15% is 26.5%. This finding shows that the W/C has a greater influence than the substitution amount. As the W/C increases, the weight loss increases. When the substitution amount increases, as TPSW has greater sulfate resistance than natural sand, the weight loss tends to decrease. The weight loss is greater at early ages, and the hydration is relatively complete at late ages, so the weight loss of the specimen decreases.

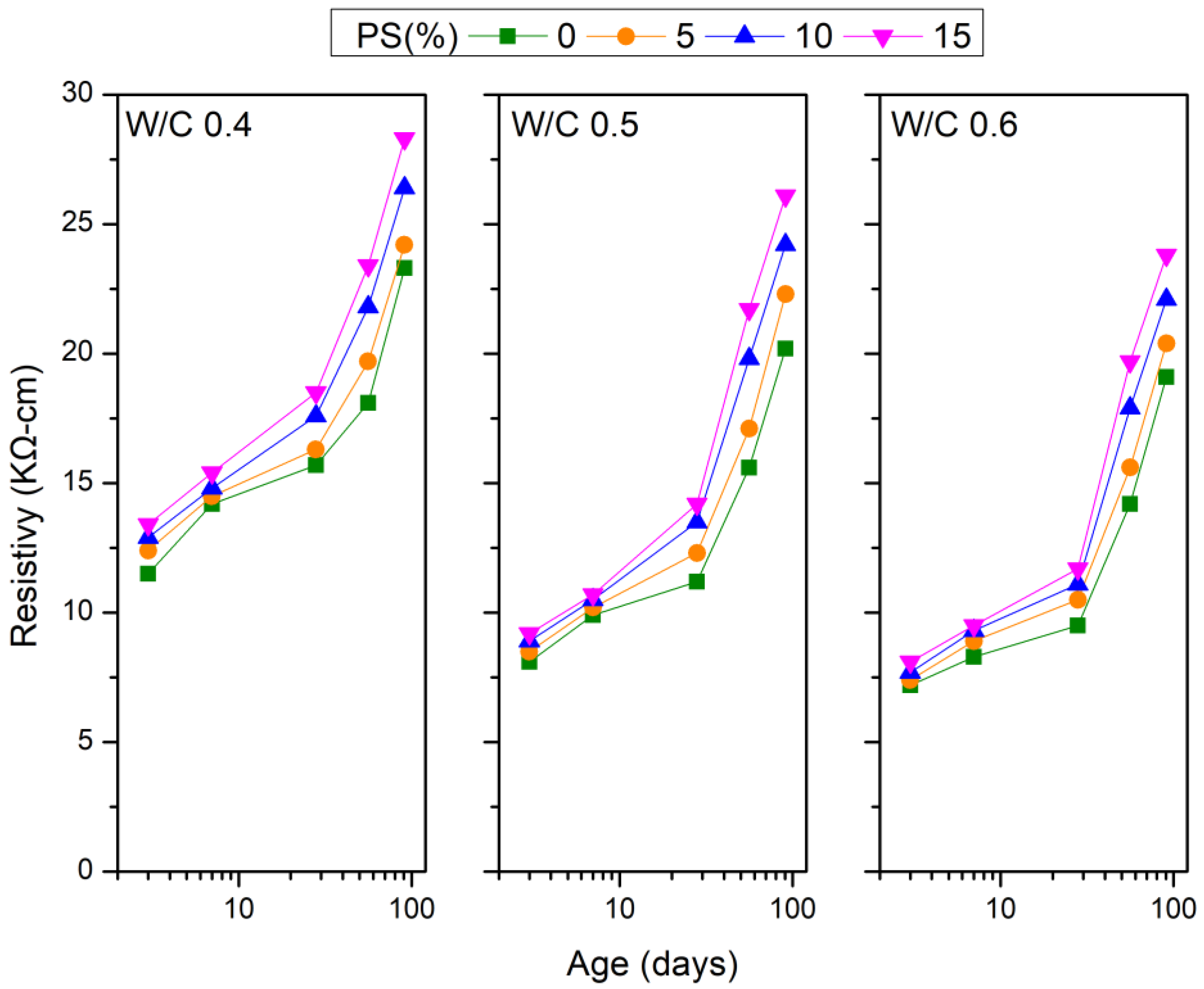

3.9. Surface Resistivity

As shown in

Figure 11, the cement mortar is made by replacing sand with TPSW, and at the age of 28 days, the resistivity of the control group with a W/C of 0.4 is 15.7 kΩ-cm. When W/C increases to 0.5, the resistivity is 11.2 kΩ-cm, which is 28.7% lower than that when W/C is 0.4. When W/C increases from 0.5 to 0.6, the resistivity is 9.5 kΩ-cm, which is 15.2% lower than that when W/C is 0.5; and the substitution amount increases from 0% to 15% when W/C is 0.4, and the resistivity is 28.3 kΩ-cm. When W/C increases to 0.5, the resistivity is 26.1 kΩ-cm, which is 7.8% lower than that when W/C is 0.4. When W/C increases from 0.5 to 0.6, the resistivity is 23.8 kΩ-cm, which is 8.8% lower than that when W/C is 0.5.

When the W/C increases, the resistivity decreases, the resistivity of TPSW is greater than that of natural sand, the resistivity increases with the substitution amount and age, and the durability of concrete is improved significantly.

Figure 1.

Experiment materials.

Figure 1.

Experiment materials.

Figure 2.

Slump of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 2.

Slump of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 3.

Slump flow of cement mortar with TPSW and different W/C ratios.

Figure 3.

Slump flow of cement mortar with TPSW and different W/C ratios.

Figure 4.

Setting time of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 4.

Setting time of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 5.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 5.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 6.

Compressive strength of cement mortar at 28-day with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 6.

Compressive strength of cement mortar at 28-day with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 7.

Flexural strength of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 7.

Flexural strength of cement mortar with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Figure 8.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 8.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 9.

Water absorption of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 9.

Water absorption of cement mortar with TPSW at different ages.

Figure 10.

Sulfate resistance of cement mortar with different TPSW and W/C ratios.

Figure 10.

Sulfate resistance of cement mortar with different TPSW and W/C ratios.

Figure 11.

Resistivity of TPSW cement mortar with different W/C ratios at different ages.

Figure 11.

Resistivity of TPSW cement mortar with different W/C ratios at different ages.

Table 1.

Resource Recovery Net, Resource Circulation Administration, Ministry of Environment - Recovery Volume Statistics.

Table 1.

Resource Recovery Net, Resource Circulation Administration, Ministry of Environment - Recovery Volume Statistics.

| |

|

|

|

|

(Unit;kg). |

| Year |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| Waste TV |

1,181,004 |

1,118,701 |

1,099,031 |

1,021,742 |

26,219,398 |

| Year |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Waste TV |

24,411,871 |

22,601,103 |

28,280,353 |

29,026,482 |

30,560,227 |

Table 2.

Physical and chemical properties of cement.

Table 2.

Physical and chemical properties of cement.

| Physical properties |

| Specific gravity |

3.15 |

| Fineness(cm2/g) |

3450 |

| Chemical contents (%) |

| SiO2

|

19.6 |

| Al2O3

|

4.4 |

| Fe2O3

|

3.1 |

| CaO |

62.5 |

| MgO |

4.9 |

| SO3

|

2.2 |

| TiO2

|

0.5 |

| P2O5

|

0.11 |

| f-CaO |

0.7 |

Table 3.

Physical properties of natural sand and TPSW.

Table 3.

Physical properties of natural sand and TPSW.

| Physical properties |

Sand |

TPSW |

| Specific gravity |

2.65 |

1.17 |

| Fineness modulus |

3.09 |

3.04 |

| Water absorption rate (%) |

1.9 |

0.1 |

Table 4.

Cement mortar proportions with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

Table 4.

Cement mortar proportions with different W/C ratios and TPSW.

| |

|

|

|

|

(Unit:g/cm3) |

| W/C |

RM(%) |

TPSW |

Sand |

Cement |

Water |

| 0.4 |

0 |

0 |

1567 |

570 |

228 |

| 5 |

78 |

1488 |

| 10 |

157 |

1410 |

| 15 |

235 |

1332 |

| 0.5 |

0 |

0 |

1482 |

539 |

270 |

| 5 |

74 |

1408 |

| 10 |

148 |

1334 |

| 15 |

222 |

1260 |

| 0.6 |

0 |

0 |

1407 |

511 |

307 |

| 5 |

70 |

1336 |

| 10 |

141 |

1266 |

| 15 |

211 |

1196 |

Table 5.

Test items and specifications.

Table 5.

Test items and specifications.

| No. |

Item |

Specification |

Purpose |

| 1 |

Slump |

ASTM C109 |

Determine the consistency of the freshly mixed cement mortar, determine the workability |

| 2 |

Slump flow |

ASTMC 1437 |

Determine the standard fluidity value in cement mortar |

| 3 |

Setting Time |

ASTM C403 |

Understand the properties of cement and reference for concrete construction |

| 4 |

Compressive Strength |

ASTM C109 |

As a reference for the mechanical strength of the specimen. |

| 5 |

Flexural Strength |

ASTM C348 |

Determine the bonding strength of cement mortar |

| 6 |

Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity |

ASTM C597 |

Understand the internal conditions of the specimen |

| 7 |

Water absorption rate |

ASTM C1585 |

Understand the internal porosity of the specimen |

| 8 |

Resistant to Sulfate Attack |

ASTM C10125 |

Work out the weight loss of cement mortar |

| 9 |

Resistivity |

ASTM C1202 |

Understand the internal density of the specimen |

Table 6.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.4 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

Table 6.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.4 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

| |

|

Unit: MPa |

| W/C |

RM(%) |

Age(days) |

| TPSW |

3 |

7 |

28 |

56 |

91 |

| 0.4 |

0 |

35.4 |

42.8 |

52.1 |

57.2 |

59.4 |

| 5 |

30.9 |

38.2 |

47.4 |

51.2 |

55.4 |

| 10 |

26.5 |

33.7 |

42.8 |

45.9 |

49.6 |

| 15 |

22.1 |

29.2 |

38.2 |

42.6 |

46.3 |

Table 7.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.5 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

Table 7.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.5 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

| |

|

Unit: MPa |

| W/C |

RM(%) |

Age(days) |

| TPSW |

3 |

7 |

28 |

56 |

91 |

| 0.5 |

0 |

30.6 |

37.9 |

46.9 |

51.1 |

53.2 |

| 5 |

26.4 |

33.9 |

42.0 |

46.3 |

48.8 |

| 10 |

22.8 |

30.2 |

39.4 |

39.4 |

45.3 |

| 15 |

18.6 |

25.7 |

34.5 |

34.5 |

40.1 |

Table 8.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.6 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

Table 8.

Compressive strength of cement mortar with W/C=0.6 and different substitution amounts of TPSW at various ages.

| |

|

Unit: MPa |

| W/C |

RM(%) |

Age(days) |

| TPSW |

3 |

7 |

28 |

56 |

91 |

| 0.6 |

0 |

28.3 |

35.4 |

43.9 |

47.4 |

49.6 |

| 5 |

24.2 |

31.5 |

40.4 |

44.6 |

46.2 |

| 10 |

20.9 |

28.1 |

37.2 |

41.6 |

43.7 |

| 15 |

16.7 |

24.3 |

32.4 |

35.9 |

39.3 |