Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. KRAS Mutations Drive Progressive Neoplastic Differentiation of the Pancreas

a. KRAS Is Pivotal in Cancer Progression

b. KRAS Plays an Important Role in PDAC

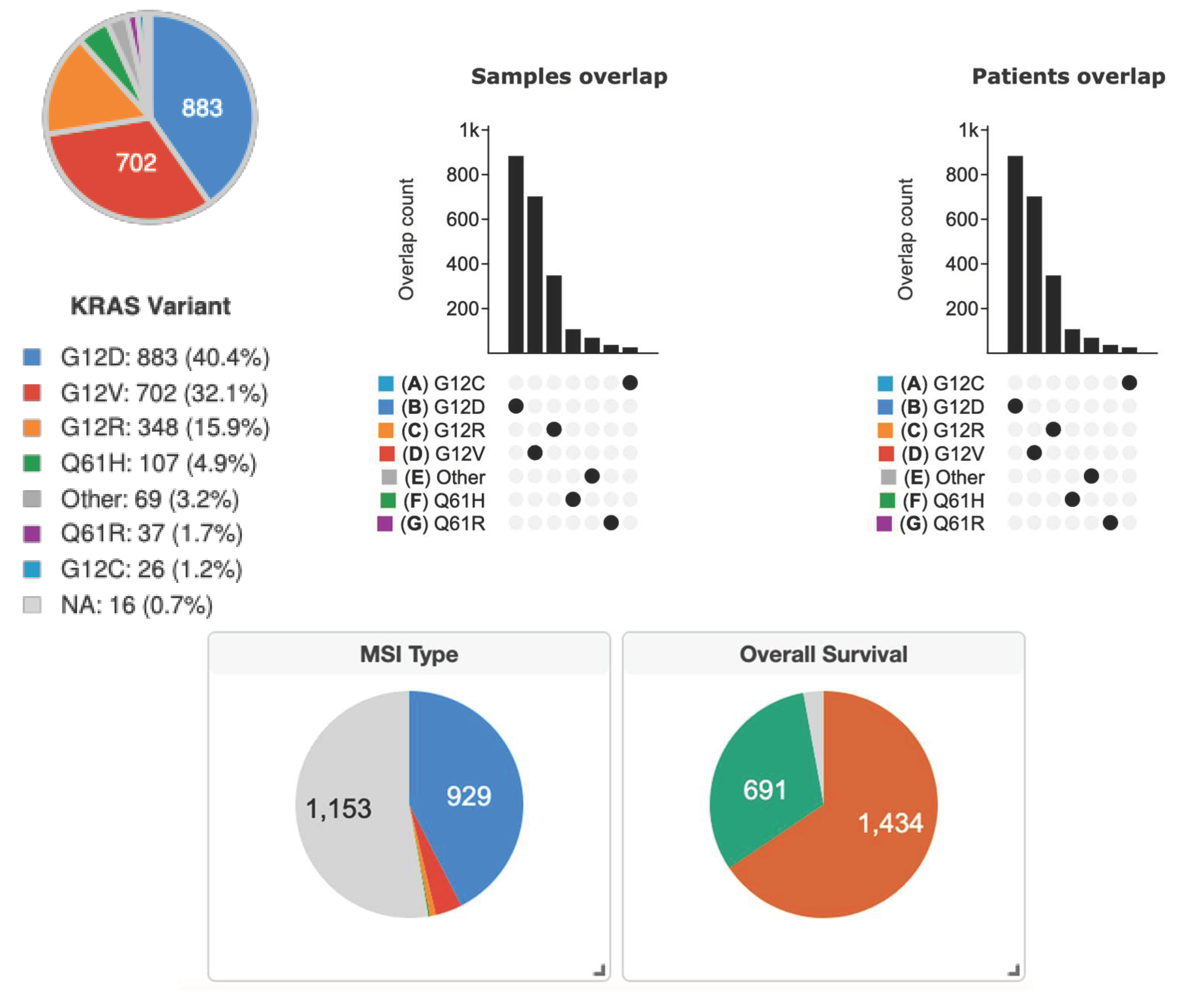

c. The Distribution of KRAS Mutations in PDAC

3. The KRASG12D Mutation in Solid-Organ Tumors Including Pancreatic Cancer

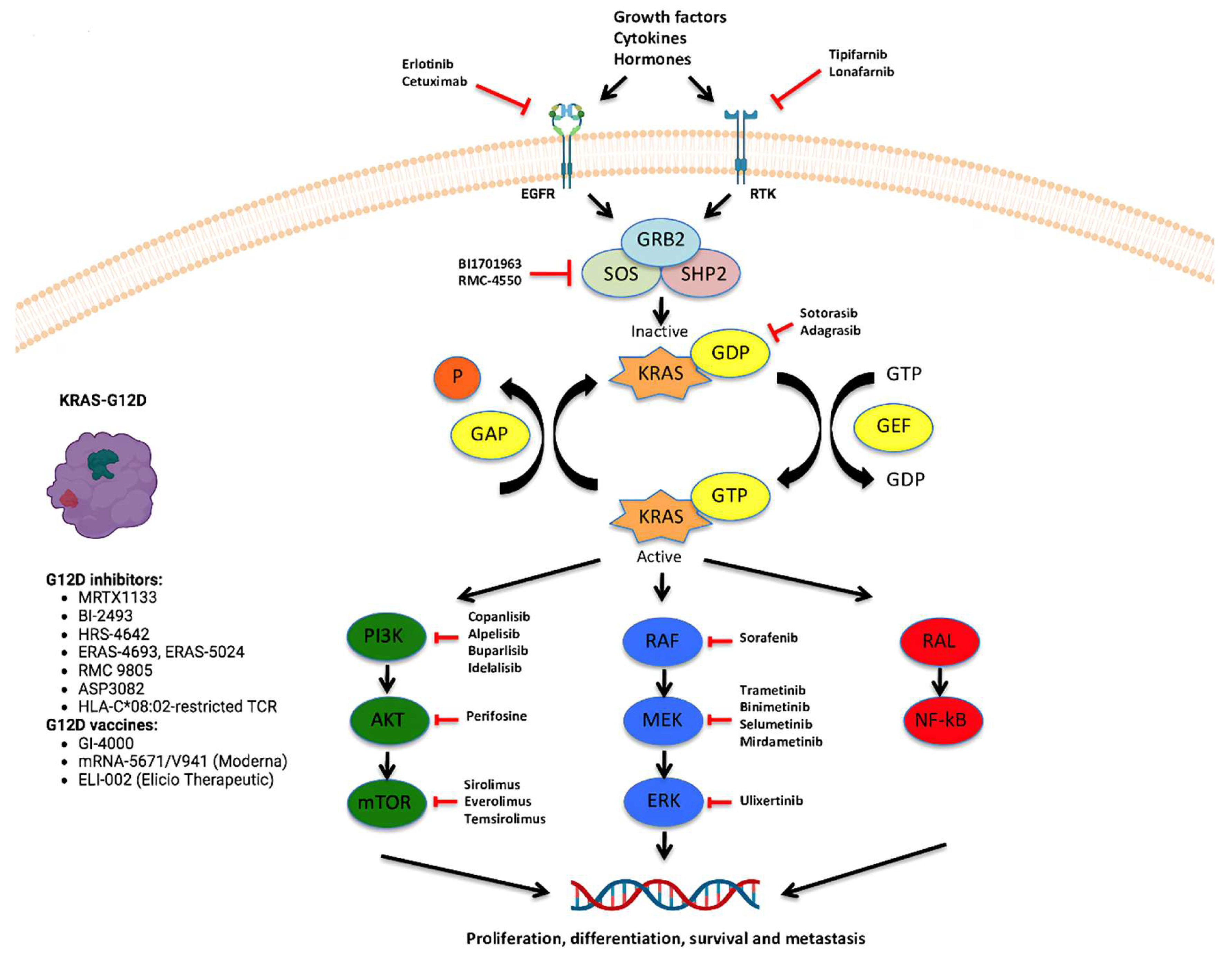

4. Latest Anti-KRASG12D Therapies

5. The Role of an Immune-Permissive Tumor Microenvironment

6. Ongoing Clinical Developments

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 2913-2921. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73, 17-48. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Parsons, D.W.; Lin, J.C.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Jimeno, A.; et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 2008, 321, 1801-1806. [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Hood, F.E.; Hartley, J.L. The Frequency of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 2969-2974. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, K.L.; Mancias, J.D.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Der, C.J. KRAS: feeding pancreatic cancer proliferation. Trends Biochem Sci 2014, 39, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Ostrem, J.M.; Peters, U.; Sos, M.L.; Wells, J.A.; Shokat, K.M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature 2013, 503, 548-551. [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.S.; Fakih, M.G.; Strickler, J.H.; Desai, J.; Durm, G.A.; Shapiro, G.I.; Falchook, G.S.; Price, T.J.; Sacher, A.; Denlinger, C.S.; et al. KRAS(G12C) Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1207-1217. [CrossRef]

- Skoulidis, F.; Li, B.T.; Dy, G.K.; Price, T.J.; Falchook, G.S.; Wolf, J.; Italiano, A.; Schuler, M.; Borghaei, H.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 2371-2381. [CrossRef]

- McGregor, L.M.; Jenkins, M.L.; Kerwin, C.; Burke, J.E.; Shokat, K.M. Expanding the Scope of Electrophiles Capable of Targeting K-Ras Oncogenes. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3178-3183. [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.B.; Fischer, J.P.; Baer, B.R.; Blake, J.F.; Bouhana, K.; Briere, D.M.; Brown, K.D.; Burgess, L.E.; Burns, A.C.; Burkard, M.R.; et al. Identification of the Clinical Development Candidate MRTX849, a Covalent KRASG12C Inhibitor for the Treatment of Cancer. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 63, 6679-6693. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Allen, S.; Blake, J.F.; Bowcut, V.; Briere, D.M.; Calinisan, A.; Dahlke, J.R.; Fell, J.B.; Fischer, J.P.; Gunn, R.J.; et al. Identification of MRTX1133, a Noncovalent, Potent, and Selective KRAS(G12D) Inhibitor. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 3123-3133. [CrossRef]

- Hallin, J.; Bowcut, V.; Calinisan, A.; Briere, D.M.; Hargis, L.; Engstrom, L.D.; Laguer, J.; Medwid, J.; Vanderpool, D.; Lifset, E.; et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a potent and selective non-covalent KRASG12D inhibitor. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2171-2182. [CrossRef]

- Neesse, A.; Michl, P.; Frese, K.K.; Feig, C.; Cook, N.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Lolkema, M.P.; Buchholz, M.; Olive, K.P.; Gress, T.M.; et al. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2011, 60, 861-868. [CrossRef]

- Feig, C.; Gopinathan, A.; Neesse, A.; Chan, D.S.; Cook, N.; Tuveson, D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 4266-4276. [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Ying, H.; Wang, X.; Hua, S.; Ligorio, M.; Perera, R.M.; Ferrone, C.R.; Mullarky, E.; Shyh-Chang, N.; et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 2013, 496, 101-105. [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Hua, S.; Chu, G.C.; Fletcher-Sananikone, E.; Locasale, J.W.; Son, J.; Zhang, H.; Coloff, J.L.; et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 2012, 149, 656-670. [CrossRef]

- Hezel, A.F.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Stanger, B.Z.; Bardeesy, N.; Depinho, R.A. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 1218-1249. [CrossRef]

- Valsangkar, N.P.; Ingkakul, T.; Correa-Gallego, C.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Masia, R.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Fernández-del Castillo, C.; Warshaw, A.L.; Liss, A.S.; Thayer, S.P. Survival in ampullary cancer: potential role of different KRAS mutations. Surgery 2015, 157, 260-268. [CrossRef]

- Pylayeva-Gupta, Y.; Grabocka, E.; Bar-Sagi, D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 761-774. [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Rago, C.; Cheong, I.; Pagliarini, R.; Angenendt, P.; Rajagopalan, H.; Schmidt, K.; Willson, J.K.; Markowitz, S.; Zhou, S.; et al. Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science 2009, 325, 1555-1559. [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, D.; Metallo, C.M.; Gameiro, P.A.; Hiller, K.; Danna, L.S.; Balestrieri, C.; Alberghina, L.; Stephanopoulos, G.; Chiaradonna, F. Oncogenic K-Ras decouples glucose and glutamine metabolism to support cancer cell growth. Mol Syst Biol 2011, 7, 523. [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Ying, H.; Wang, X.; Hua, S.; Ligorio, M.; Perera, R.M.; Ferrone, C.R.; Mullarky, E.; Shyh-Chang, N.; et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 2013, 496, 101-105. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Matthaei, H.; Wu, J.; Hong, S.M.; Yu, J.; Borges, M.; Hruban, R.H.; Maitra, A.; Kinzler, K.; Vogelstein, B.; et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 730-733.e739. [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Qia, C.; Erkan, M.; Kleeff, J.; Michalski, C.W. Overview on how oncogenic Kras promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis by inducing low intracellular ROS levels. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 246. [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, G.M.; Karreth, F.A.; Humpton, T.J.; Gopinathan, A.; Wei, C.; Frese, K.; Mangal, D.; Yu, K.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Calhoun, E.S.; et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106-109. [CrossRef]

- Matés, J.M.; Segura, J.A.; Alonso, F.J.; Márquez, J. Oxidative stress in apoptosis and cancer: an update. Arch Toxicol 2012, 86, 1649-1665. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, F.; Hamanaka, R.; Wheaton, W.W.; Weinberg, S.; Joseph, J.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 8788-8793. [CrossRef]

- Matés, J.M.; Segura, J.A.; Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Lobo, C.; Alonso, L.; Alonso, F.J.; Márquez, J. Glutamine homeostasis and mitochondrial dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 2051-2061. [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; White, E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010, 330, 1344-1348. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Klionsky, D.J. The regulation of autophagy - unanswered questions. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 161-170. [CrossRef]

- Hippert, M.M.; O’Toole, P.S.; Thorburn, A. Autophagy in cancer: good, bad, or both? Cancer Res 2006, 66, 9349-9351. [CrossRef]

- Kimmelman, A.C. The dynamic nature of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 1999-2010. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Mitsunaga, S.; Yamazaki, M.; Hasebe, T.; Ishii, G.; Kojima, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Ueno, T.; Esumi, H.; Ochiai, A. Autophagy is activated in pancreatic cancer cells and correlates with poor patient outcome. Cancer Sci 2008, 99, 1813-1819. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Contino, G.; Liesa, M.; Sahin, E.; Ying, H.; Bause, A.; Li, Y.; Stommel, J.M.; Dell’antonio, G.; et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 717-729. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Mathew, R.; Fan, J.; Strohecker, A.M.; Karsli-Uzunbas, G.; Kamphorst, J.J.; Chen, G.; Lemons, J.M.; Karantza, V.; et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 460-470. [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, O.; Bourdeau, V.; Roux, A.; Deschênes-Simard, X.; Ferbeyre, G. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to oncogene-induced senescence. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 4495-4507. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.D.; Lapi, E.; Sullivan, A.; Jia, W.; He, Y.W.; Ratnayaka, I.; Zhong, S.; Goldin, R.D.; Goemans, C.G.; et al. Autophagic activity dictates the cellular response to oncogenic RAS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 13325-13330. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Narita, M.; Ferreira, M.; Kirschner, K.; Sadaie, M.; Darot, J.F.; Tavaré, S.; Arakawa, S.; Shimizu, S.; Watt, F.M.; et al. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 798-803. [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, M.; Sheridan, C.; Brumatti, G.; Martin, S.J. Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell 2011, 42, 23-35. [CrossRef]

- Bournet, B.; Muscari, F.; Buscail, C.; Assenat, E.; Barthet, M.; Hammel, P.; Selves, J.; Guimbaud, R.; Cordelier, P.; Buscail, L. KRAS G12D Mutation Subtype Is A Prognostic Factor for Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016, 7, e157. [CrossRef]

- Boeck, S.; Jung, A.; Laubender, R.P.; Neumann, J.; Egg, R.; Goritschan, C.; Ormanns, S.; Haas, M.; Modest, D.P.; Kirchner, T.; et al. KRAS mutation status is not predictive for objective response to anti-EGFR treatment with erlotinib in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol 2013, 48, 544-548. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, H.; Qiu, G. Clinical Effect of Driver Mutations of KRAS, CDKN2A/P16, TP53, and SMAD4 in Pancreatic Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2020, 24, 777-788. [CrossRef]

- Ogura, T.; Yamao, K.; Hara, K.; Mizuno, N.; Hijioka, S.; Imaoka, H.; Sawaki, A.; Niwa, Y.; Tajika, M.; Kondo, S.; et al. Prognostic value of K-ras mutation status and subtypes in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration specimens from patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol 2013, 48, 640-646. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.R.; Rubinson, D.A.; Nowak, J.A.; Morales-Oyarvide, V.; Dunne, R.F.; Kozak, M.M.; Welch, M.W.; Brais, L.K.; Da Silva, A.; Li, T.; et al. Association of Alterations in Main Driver Genes With Outcomes of Patients With Resected Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, e173420. [CrossRef]

- Rachakonda, P.S.; Bauer, A.S.; Xie, H.; Campa, D.; Rizzato, C.; Canzian, F.; Beghelli, S.; Greenhalf, W.; Costello, E.; Schanne, M.; et al. Somatic mutations in exocrine pancreatic tumors: association with patient survival. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60870. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Kim, S.C.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Song, K.B.; Park, K.M.; Lee, Y.J. Genetic alterations of K-ras, p53, c-erbB-2, and DPC4 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their correlation with patient survival. Pancreas 2013, 42, 216-222. [CrossRef]

- Kawesha, A.; Ghaneh, P.; Andrén-Sandberg, A.; Ograed, D.; Skar, R.; Dawiskiba, S.; Evans, J.D.; Campbell, F.; Lemoine, N.; Neoptolemos, J.P. K-ras oncogene subtype mutations are associated with survival but not expression of p53, p16(INK4A), p21(WAF-1), cyclin D1, erbB-2 and erbB-3 in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2000, 89, 469-474. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liao, X.; Tsai, H.I. KRAS mutation: The booster of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma transformation and progression. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1147676. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.; Yousef, M.; Chowdhury, S.; Abdilleh, K.; Knafl, M.; Edelkamp, P.; Alfaro-Munoz, K.; Chacko, R.; Peterson, J.; Smaglo, B.G.; et al. Impact of KRAS mutations and co-mutations on clinical outcomes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Biankin, A.V.; Waddell, N.; Kassahn, K.S.; Gingras, M.C.; Muthuswamy, L.B.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.K.; Wilson, P.J.; Patch, A.M.; Wu, J.; et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 2012, 491, 399-405. [CrossRef]

- Neuzillet, C.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; de Mestier, L.; Cros, J.; Faivre, S.; Raymond, E. MEK in cancer and cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther 2014, 141, 160-171. [CrossRef]

- Buscail, L.; Bournet, B.; Cordelier, P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 153-168. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Kitago, M.; Matsuda, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Imai, S.; Shinoda, M.; Yagi, H.; Abe, Y.; Hibi, T.; et al. KRAS mutations in cell-free DNA from preoperative and postoperative sera as a pancreatic cancer marker: a retrospective study. Br J Cancer 2018, 118, 662-669. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J. KRAS mutation in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol 2021, 48, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Lewis, P.D.; Mattos, C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 2457-2467. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; García, E.; Diaz, D.C.; Ruiz-Garcia, E.; Miyagui Adame, S.; Zilli Hernandez, S.; Lopez, M.; Carbajal, B.; Calderillo Ruiz, G. Real-world impact on overall survival of oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with colorectal cancer in Mexico. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 61-61. [CrossRef]

- Philip, P.A.; Azar, I.; Xiu, J.; Hall, M.J.; Hendifar, A.E.; Lou, E.; Hwang, J.J.; Gong, J.; Feldman, R.; Ellis, M.; et al. Molecular Characterization of KRAS Wild-type Tumors in Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2022, 28, 2704-2714. [CrossRef]

- Nusrat, F.; Khanna, A.; Jain, A.; Jiang, W.; Lavu, H.; Yeo, C.J.; Bowne, W.; Nevler, A. The Clinical Implications of KRAS Mutations and Variant Allele Frequencies in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2103. [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Petricoin, E.F.; Maitra, A.; Rajapakse, V.; King, C.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Ross, S.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Hitt, B.A.; et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 437-450. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.J.; Bardeesy, N.; Sinha, M.; Lopez, L.; Tuveson, D.A.; Horner, J.; Redston, M.S.; DePinho, R.A. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 3112-3126. [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Wang, L.; Multani, A.S.; Combs, C.; Deramaudt, T.B.; Hruban, R.H.; Rustgi, A.K.; Chang, S.; Tuveson, D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 469-483. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Vickers, S.M.; Adsay, N.V.; Jhala, N.C.; Kim, H.G.; Schoeb, T.R.; Grizzle, W.E.; Klug, C.A. Inactivation of Smad4 accelerates Kras(G12D)-mediated pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 8121-8130. [CrossRef]

- Bardeesy, N.; Aguirre, A.J.; Chu, G.C.; Cheng, K.H.; Lopez, L.V.; Hezel, A.F.; Feng, B.; Brennan, C.; Weissleder, R.; Mahmood, U.; et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 5947-5952. [CrossRef]

- Grabocka, E.; Pylayeva-Gupta, Y.; Jones, M.J.; Lubkov, V.; Yemanaberhan, E.; Taylor, L.; Jeng, H.H.; Bar-Sagi, D. Wild-type H- and N-Ras promote mutant K-Ras-driven tumorigenesis by modulating the DNA damage response. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 243-256. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Ancrile, B.B.; Kashatus, D.F.; Counter, C.M. Tumour maintenance is mediated by eNOS. Nature 2008, 452, 646-649. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.A.; Bednar, F.; Zhang, Y.; Brisset, J.C.; Galbán, S.; Galbán, C.J.; Rakshit, S.; Flannagan, K.S.; Adsay, N.V.; Pasca di Magliano, M. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 639-653. [CrossRef]

- Heid, I.; Lubeseder-Martellato, C.; Sipos, B.; Mazur, P.K.; Lesina, M.; Schmid, R.M.; Siveke, J.T. Early requirement of Rac1 in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 719-730, 730.e711-717. [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.Y.; Jubb, A.M.; Koch, J.N.; Jaffer, Z.M.; Stepanova, D.; Campbell, D.A.; Duron, S.G.; O’Farrell, M.; Cai, K.Q.; Klein-Szanto, A.J.; et al. p21-Activated kinase 1 is required for efficient tumor formation and progression in a Ras-mediated skin cancer model. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 5966-5975. [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.M.; Der, C.J. KRAS: The Critical Driver and Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Castellano, E.; Sheridan, C.; Thin, M.Z.; Nye, E.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Diefenbacher, M.E.; Moore, C.; Kumar, M.S.; Murillo, M.M.; Grönroos, E.; et al. Requirement for interaction of PI3-kinase p110α with RAS in lung tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 617-630. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ramjaun, A.R.; Haiko, P.; Wang, Y.; Warne, P.H.; Nicke, B.; Nye, E.; Stamp, G.; Alitalo, K.; Downward, J. Binding of ras to phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110alpha is required for ras-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Cell 2007, 129, 957-968. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, R.B.; Francoz, S.; Santamaría, D.; Cañamero, M.; Dubus, P.; Charron, J.; Baccarini, M.; Barbacid, M. c-Raf, but not B-Raf, is essential for development of K-Ras oncogene-driven non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 652-663. [CrossRef]

- Karreth, F.A.; Frese, K.K.; DeNicola, G.M.; Baccarini, M.; Tuveson, D.A. C-Raf is required for the initiation of lung cancer by K-Ras(G12D). Cancer Discov 2011, 1, 128-136. [CrossRef]

- Barbacid, M. ras oncogenes: their role in neoplasia. Eur J Clin Invest 1990, 20, 225-235. [CrossRef]

- Zarbl, H.; Sukumar, S.; Arthur, A.V.; Martin-Zanca, D.; Barbacid, M. Direct mutagenesis of Ha-ras-1 oncogenes by N-nitroso-N-methylurea during initiation of mammary carcinogenesis in rats. Nature 1985, 315, 382-385. [CrossRef]

- Törmänen, V.T.; Pfeifer, G.P. Mapping of UV photoproducts within ras proto-oncogenes in UV-irradiated cells: correlation with mutations in human skin cancer. Oncogene 1992, 7, 1729-1736.

- Seo, K.Y.; Jelinsky, S.A.; Loechler, E.L. Factors that influence the mutagenic patterns of DNA adducts from chemical carcinogens. Mutat Res 2000, 463, 215-246. [CrossRef]

- Le Calvez, F.; Mukeria, A.; Hunt, J.D.; Kelm, O.; Hung, R.J.; Tanière, P.; Brennan, P.; Boffetta, P.; Zaridze, D.G.; Hainaut, P. TP53 and KRAS mutation load and types in lung cancers in relation to tobacco smoke: distinct patterns in never, former, and current smokers. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 5076-5083. [CrossRef]

- Capella, G.; Cronauer-Mitra, S.; Pienado, M.A.; Perucho, M. Frequency and spectrum of mutations at codons 12 and 13 of the c-K-ras gene in human tumors. Environ Health Perspect 1991, 93, 125-131. [CrossRef]

- Porta, M.; Crous-Bou, M.; Wark, P.A.; Vineis, P.; Real, F.X.; Malats, N.; Kampman, E. Cigarette smoking and K-ras mutations in pancreas, lung and colorectal adenocarcinomas: etiopathogenic similarities, differences and paradoxes. Mutat Res 2009, 682, 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.S. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 733-744. [CrossRef]

- De Roock, W.; Jonker, D.J.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Tu, D.; Siena, S.; Lamba, S.; Arena, S.; Frattini, M.; Piessevaux, H.; et al. Association of KRAS p.G13D mutation with outcome in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Jama 2010, 304, 1812-1820. [CrossRef]

- Sipos, J.A.; Mazzaferri, E.L. Thyroid cancer epidemiology and prognostic variables. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010, 22, 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Feng, Z.; Tang, M.S. Preferential carcinogen-DNA adduct formation at codons 12 and 14 in the human K-ras gene and their possible mechanisms. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 10012-10023. [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Reimers, J.M.; Schmidt, K.H.; Reschke, D.K. Hypermutable bases in the p53 cancer gene are at vulnerable positions in DNA secondary structures. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 5641-5644.

- Gougopoulou, D.M.; Kiaris, H.; Ergazaki, M.; Anagnostopoulos, N.I.; Grigoraki, V.; Spandidos, D.A. Mutations and expression of the ras family genes in leukemias. Stem Cells 1996, 14, 725-729. [CrossRef]

- Denissenko, M.F.; Pao, A.; Pfeifer, G.P.; Tang, M. Slow repair of bulky DNA adducts along the nontranscribed strand of the human p53 gene may explain the strand bias of transversion mutations in cancers. Oncogene 1998, 16, 1241-1247. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Allen, S.; Blake, J.F.; Bowcut, V.; Briere, D.M.; Calinisan, A.; Dahlke, J.R.; Fell, J.B.; Fischer, J.P.; Gunn, R.J.; et al. Identification of MRTX1133, a Noncovalent, Potent, and Selective KRASG12D Inhibitor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 3123-3133. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Herdeis, L.; Rudolph, D.; Zhao, Y.; Böttcher, J.; Vides, A.; Ayala-Santos, C.I.; Pourfarjam, Y.; Cuevas-Navarro, A.; Xue, J.Y.; et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature 2023, 619, 160-166. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Gómez, A.A.; Drosten, M. HRS-4642: The next piece of the puzzle to keep KRAS in check. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1157-1159. [CrossRef]

- Brooun, A.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Lam, R.; Cheng, H.; Shoemaker, R.; Daly, J.; Olaharski, A. The pharmacologic and toxicologic characterization of the potent and selective KRAS G12D inhibitors ERAS-4693 and ERAS-5024. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2023, 474, 116601. [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.E.; Jiang, J.; Burnett, G.L.; Liu, Y.; Weller, C.E.; Wang, Z.; McDowell, L.; Steele, S.L.; Chin, S.; Chou, K.J.; et al. Abstract 3596: RM-036, a first-in-class, orally-bioavailable, Tri-Complex covalent KRASG12D(ON) inhibitor, drives profound anti-tumor activity in KRASG12D mutant tumor models. Cancer Research 2022, 82, 3596-3596. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Menard, M.; Weller, C.; Wang, Z.; Burnett, L.; Aronchik, I.; Steele, S.; Flagella, M.; Zhao, R.; Evans, J.W.W.; et al. Abstract 526: RMC-9805, a first-in-class, mutant-selective, covalent and oral KRASG12D(ON) inhibitor that induces apoptosis and drives tumor regression in preclinical models of KRASG12D cancers. Cancer Research 2023, 83, 526-526. [CrossRef]

- KRAS G12D degrader ASP3082. NIH Website.

- Nagashima, T.; Inamura, K.; Nishizono, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Tanaka, H.; Yoshinari, T.; Yamanaka, Y. ASP3082, a First-in-class novel KRAS G12D degrader, exhibits remarkable anti-tumor activity in KRAS G12D mutated cancer models. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 174, S30. [CrossRef]

- autologous KRAS G12D-specific HLA-C*08:02-restricted TCR gene engineered T lymphocytes NT-112. NIH Website.

- Leidner, R.; Sanjuan Silva, N.; Huang, H.; Sprott, D.; Zheng, C.; Shih, Y.P.; Leung, A.; Payne, R.; Sutcliffe, K.; Cramer, J.; et al. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 2112-2119. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tubb, V.; Mojadidi, M.; Meade, K.; Kong, X.; Kroon, P.; Sareen, A.; Stringer, B.; Krijgsman, O.; Claasen, Y.; et al. Non-clinical evaluation of NT-112, an autologous T cell product engineered to express an HLA-C*08:02-restricted TCR targeting KRAS G12D and resistant to TGF-b inhibition. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e14533-e14533. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.A.; Grimont, A.; Park, J.; Meng, Y.; Sisso, W.J.; Seier, K.; Jang, G.H.; Walch, H.; Aveson, V.G.; Falvo, D.J.; et al. Distinct clinical outcomes and biological features of specific <em>KRAS</em> mutants in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1614-1629. [CrossRef]

- McAndrews, K.M.; Mahadevan, K.K.; Li, B.; Sockwell, A.M.; Morse, S.J.; Kelly, P.J.; Kirtley, M.L.; Conner, M.R.; Patel, S.I.; Khumbar, S.V.; et al. Abstract B092: CDK8 and CXCL2 remodel the tumor microenvironment to contribute to KRASG12D small molecule inhibition resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research 2024, 84, B092-B092. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, W.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Mao, R.; Huang, C.; et al. LBA33 A first-in-human phase I study of a novel KRAS G12D inhibitor HRS-4642 in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring KRAS G12D mutation. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S1273. [CrossRef]

- Tolcher, A.W.; Park, W.; Wang, J.S.; Spira, A.I.; Janne, P.A.; Lee, H.-J.; Gill, S.; LoRusso, P.; Herzberg, B.; Goldman, J.W.; et al. Trial in progress: A phase 1, first-in-human, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation and dose-expansion study of ASP3082 in patients with previously treated advanced solid tumors and KRAS G12D mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, TPS764-TPS764. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Sei, S.; Shoemaker, R.H.; Lubet, R.A.; Wang, Y.; You, M. Immunoprevention of KRAS-driven lung adenocarcinoma by a multipeptide vaccine. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 82689-82699. [CrossRef]

- Chaft, J.E.; Litvak, A.; Arcila, M.E.; Patel, P.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Krug, L.M.; Rusch, V.; Mattson, A.; Coeshott, C.; Park, B.; et al. Phase II study of the GI-4000 KRAS vaccine after curative therapy in patients with stage I-III lung adenocarcinoma harboring a KRAS G12C, G12D, or G12V mutation. Clin Lung Cancer 2014, 15, 405-410. [CrossRef]

- mRNA-derived KRAS-targeted vaccine V941. NIH Website.

- Sutanto, F.; Konstantinidou, M.; Dömling, A. Covalent inhibitors: a rational approach to drug discovery. RSC Med Chem 2020, 11, 876-884. [CrossRef]

- Kingwell, K. A non-covalent inhibitor with pan-KRAS potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 622. [CrossRef]

- Dilly, J.; Hoffman, M.T.; Abbassi, L.; Li, Z.; Paradiso, F.; Parent, B.D.; Hennessey, C.J.; Jordan, A.C.; Morgado, M.; Dasgupta, S.; et al. Mechanisms of resistance to oncogenic KRAS inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov 2024, 7, 1137-1357. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, A.K.; Piazza, G.A.; Keeton, A.B.; Leite, C.A. The path to the clinic: a comprehensive review on direct KRAS(G12C) inhibitors. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 27. [CrossRef]

- Batrash, F.; Kutmah, M.; Zhang, J. The current landscape of using direct inhibitors to target KRAS(G12C)-mutated NSCLC. Exp Hematol Oncol 2023, 12, 93. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.B.; Corcoran, R.B. Therapeutic strategies to target RAS-mutant cancers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15, 709-720. [CrossRef]

| Trial Identifier | Investigation Plan | Viral Vaccine/ Drug |

Clinical Setting | Primary Endpoint | Phase | Trial Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06385925 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | TSN1611 | First line | DLT | I/II | Recruiting |

| NCT06385678 | Non-randomized, single group assignment, open label | HRS-4642; adebrelimab; SHR-A1921; chemotherapy: pemetrexed, cisplatin, carboplatin |

First line | DLT, RP2D, ORR | Ib/II | Recruiting |

| NCT06500676 | Single group assignment, open label | GFH375 | First line | DLT, ORR | I/II | Recruiting |

| NCT05737706 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | MRTX1133 | Second or later line | DLT, ORR, DOR, PFS, OS | I/II | Recruiting |

| NCT06478251 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | NW-301 TCR-T, NW-301D TCR-T | First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06403735 | Non-randomized, single group assignment, open label | QLC1101 | First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT03745326 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | Drug: cyclophosphamide Drug: fludarabine Drug: aldesleukin Biological: anti-KRAS G12D mTCR peripheral blood lymphocytes |

First line | DLT; PR+CR | I/II | Recruiting |

| NCT06218914 | Sequential assignment, open label | NT-112 | First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT05533463 | Non-randomized, single group assignment | HRS-4642 | First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06364696 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | ASP4396 | First or later line | DLT, ORR, DOR, DCR, PFS, OS | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06040541 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | RMC-9805 RMC-6236 |

Second line | AEs, DLT | I/Ib | Recruiting |

| NCT05382559 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | ASP3082; cetuximab; chemotherapies |

First line | AEs, DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06546150 | Single assignment, open label | RE002 T cell | First line | AEs | I | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT05254184 | Single assignment, open label | Mutant KRAS-targeted long peptide vaccine | First line | AEs | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06484790 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | NW-301V; NW-301D |

First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06484556 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | NW-301V; NW-301D |

First line | DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06487377 | Single assignment, 3+3 dose escalation, open label | IX001 TCR-T | First or Later line | AEs, DLT | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06428500 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | QTX3046 | First or Later line | TEAEs, DLTs | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06520488 | Single group assignment, open label | HRS-4642 | First or Later line | MTD | Ib/II | Not-Yet Recruiting |

| NCT06227377 | Non-randomized, single group assignment, open label | QTX3034 | First line | DLT, TEAEs | I | Recruiting |

| NCT05726864 | Randomized, sequential assignment, open label | ELI-002 7P | First or Later line | AEs | Ia, Ib, II | Recruiting |

| NCT05786924 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | BDTX-4933 | First line | MTD | I | Recruiting |

| NCT06447662 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | PF-07934040 | First or later line | AEs, DLT | I/IIa and IIb | Recruiting |

| NCT06179160 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | INCB161734; cetuximab; retifanlimab | First line | DLTs, TEAEs | I | Recruiting |

| NCT05846516 | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open label | VSV-GP154; ATP150; ATP152; ezabenlimab |

First line | DLT, DFS |

Ib | Recruiting |

| NCT05983159 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | Alpelisib; mirdametinib |

First line | VM-PSOM | II | Not-Yet Recruiting |

| NCT06208124 | Treatment, single group assignment, open label | IMM-6-415 | First or later lines | DLT | I/IIa | Recruiting |

| NCT05585320 | Non-randomized, parallel assignment, open label | IMM-1-104 monotherapy (treatment group A); IMM-1-104 + modified gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (treatment group B); IMM-1-104 + modified FOLFIRINOX (treatment group C) |

First line or later line | AEs, DLTs, RP2D, OS |

I/IIa | Recruiting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).