Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB): A Central Player in the Development of Neuroinflammation and Neurodegenerative Conditions

3. Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2): A Novel Approach to Address Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders

4. Impact of the NLR (Nucleotide-binding Domain and Leucine-rich Repeat Containing) Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) Inflammasome on Neuroinflammation: Exploring a Promising Therapeutic Target for Neuroinflammation

5. JAK/STAT: An Evergreen and Unconventional Pathway in Neuroinflammation and Neurological Dysfunctions

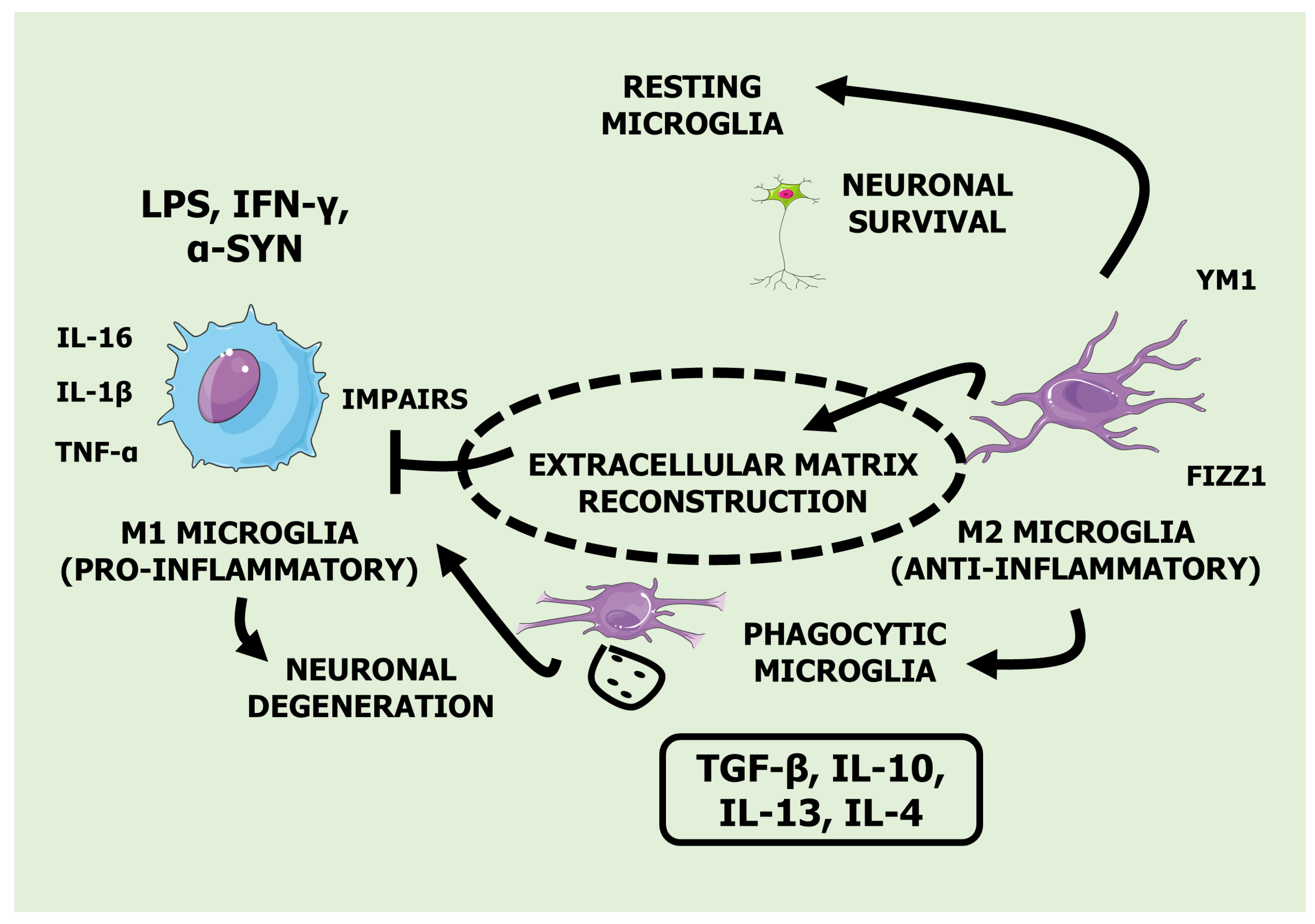

6. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation: Charting the Path Forward Alzheimer's Disease, Parkinson's Disease, and Multiple Sclerosis

7. Exploring Medicinal Plants in Neuroinflammation: Comprehensive Insights on Effects, Dosage, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davinelli, S.; Maes, M.; Corbi, G.; Zarrelli, A.; Willcox, D.C.; Scapagnini, G. Dietary phytochemicals and neuro-inflammaging: from mechanistic insights to translational challenges. Immun Ageing 2016, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Xiao, Q.; Fan, H.J.; Xu, L.; Qin, S.C.; Yang, L.X.; Jin, X.M.; Xiao, B.G.; Zhang, B.; Ma, C.G.; et al. Wuzi Yanzong Pill relieves MPTP-induced motor dysfunction and neuron loss by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation. Metab Brain Dis 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. A Decade of Dedication: Pioneering Perspectives on Neurological Diseases and Mental Illnesses. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Revolutionizing our understanding of Parkinson's disease: Dr. Heinz Reichmann's pioneering research and future research direction. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rink, C.; Khanna, S. Significance of brain tissue oxygenation and the arachidonic acid cascade in stroke. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011, 14, 1889–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozumi, T.; Preziosa, P.; Meani, A.; Albergoni, M.; Margoni, M.; Pagani, E.; Filippi, M.; Rocca, M.A. Influence of cardiorespiratory fitness and MRI measures of neuroinflammation on hippocampal volume in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Solleiro-Villavicencio, H.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Effect of Chronic Oxidative Stress on Neuroinflammatory Response Mediated by CD4(+)T Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2018, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direito, R.; Barbalho, S.M.; Figueira, M.E.; Minniti, G.; de Carvalho, G.M.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; de Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R.; de Góes Corrêa, N.; Rodrigues, V.D.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; et al. Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals and Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, II; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Moretti, R.C., Jr.; Torres Pomini, K.; Laurindo, L.F.; Sloan, K.P.; Sloan, L.A.; Castro, M.V.M.; Baldi, E., Jr.; Ferraz, B.F.R.; de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, E.; et al. Glycolipid Metabolic Disorders, Metainflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling Pathways. Biology 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girotto, O.S.; Furlan, O.O.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Goulart, R.A.; Baldi Junior, E.; Barbalho-Lamas, C.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Barbalho, S.M. Effects of apples (Malus domestica) and their derivatives on metabolic conditions related to inflammation and oxidative stress and an overview of by-products use in food processing. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2024, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; Dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira Rossi, J.L.; Barbalho, S.M.; Reverete de Araujo, R.; Bechara, M.D.; Sloan, K.P.; Sloan, L.A.J.D.m.r.; reviews. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: Going beyond traditional risk factors. 2022, 38, e3502.

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabisiak, T.; Patel, M. Crosstalk between neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in epilepsy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 976953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Lopez, A.; Torres-Paniagua, A.M.; Acero, G.; Díaz, G.; Gevorkian, G. Increased TSPO expression, pyroglutamate-modified amyloid beta (AβN3(pE)) accumulation and transient clustering of microglia in the thalamus of Tg-SwDI mice. J Neuroimmunol 2023, 382, 578150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Carvalho, G.M.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Figueira, M.E.; Direito, R.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Buglio, D.S.; Barbalho, S.M. Curcumin-Based Nanomedicines in the Treatment of Inflammatory and Immunomodulated Diseases: An Evidence-Based Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S.; Giménez-Llort, L.; Chen, C.; Hepsomali, P.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L. Innovation at the Intersection: Emerging Translational Research in Neurology and Psychiatry. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Chen, C. Editorial: Towards a mechanistic understanding of depression, anxiety, and their comorbidity: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2023, 17, 1268156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopper, A.T.; Campbell, B.M.; Kao, H.; Pintchovski, S.A.; Staal, R.G.W. Chapter Four - Recent Developments in Targeting Neuroinflammation in Disease. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry, Desai, M.C., Ed.; Academic Press: 2012; Volume 47, pp. 37-53.

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Luo, N.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, F.; Pan, Z.; Li, X.; Jian, W.; Yang, X.; Xue, Q.; et al. An Fgr kinase inhibitor attenuates sepsis-associated encephalopathy by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation via the SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bássoli, R.; Audi, D.; Ramalho, B.; Audi, M.; Quesada, K.; Barbalho, S.J.J.o.H.M. The Effects of Curcumin on Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. 2023, 42, 100771.

- Barbalho, S.M.; Direito, R.; Laurindo, L.F.; Marton, L.T.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Tofano, R.J.; Carvalho, A.C.; Flato, U.A.P.; Capelluppi Tofano, V.A.J.A. Ginkgo biloba in the aging process: A narrative review. 2022, 11, 525.

- de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Dos Santos, A.R.d.O.; Miola, V.F.B.; Campos, L.M.G.; Spilla, C.S.G.; Barbalho, S.M.J.E.g. Panax ginseng and aging related disorders: A systematic review. 2022, 161, 111731.

- Rangaraju, S.; Dammer, E.B.; Raza, S.A.; Rathakrishnan, P.; Xiao, H.; Gao, T.; Duong, D.M.; Pennington, M.W.; Lah, J.J.; Seyfried, N.T.; et al. Identification and therapeutic modulation of a pro-inflammatory subset of disease-associated-microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank-Stein, N.; Mass, E. Macrophage and monocyte subsets in response to ischemic stroke. Eur J Immunol 2023, e2250233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Ma, Q.; Ye, L.; Piao, G. The Traditional Medicine and Modern Medicine from Natural Products. Molecules 2016, 21, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of Nutritional Science 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. The Role of Dietary Phytochemicals: Evidence from Epidemiological Studies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglio, D.S.; Marton, L.T.; Laurindo, L.F.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Rubira, C.J.; Barbalho, S.M. The Role of Resveratrol in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Med Food 2022, 25, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Bueno Ottoboni, A.M.M.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Guiguer, E.L.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Flato, U.A.P.J.C.r.i.f.s.; nutrition. Grape juice or wine: which is the best option? 2020, 60, 3876-3889.

- Barbalho, S.M.; Bueno Ottoboni, A.M.M.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Guiguer, E.L.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Flato, U.A.P.J.C.r.i.f.s.

- Sen, T.; Samanta, S.K. Medicinal plants, human health and biodiversity: a broad review. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 2015, 147, 59–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs and Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, G.L.O.; Santos, L.; Osman, N.; Lamas, C.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; Guissoni, L.M.; Lima, E.P.; Goulart, R.A.; Catharin, V.; et al. Ginkgo biloba: A Leaf of Hope in the Fight against Alzheimer's Dementia: Clinical Trial Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, S.E.B.; Tyler, L.D.K. Pathways to healing: Plants with therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases. IBRO Neurosci Rep 2023, 14, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, K. Regulation of neuroinflammation by herbal medicine and its implications for neurodegenerative diseases. A focus on traditional medicines and flavonoids. Neurosignals 2005, 14, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janpaijit, S.; Sillapachaiyaporn, C.; Theerasri, A.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; Sukprasansap, M.; Tencomnao, T. Cleistocalyx nervosum var. paniala Berry Seed Protects against TNF-α-Stimulated Neuroinflammation by Inducing HO-1 and Suppressing NF-κB Mechanism in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janpaijit, S.; Lertpatipanpong, P.; Sillapachaiyaporn, C.; Baek, S.J.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; Tencomnao, T.; Sukprasansap, M. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of Cleistocalyx nervosum var. paniala berry-seed extract in BV-2 microglial cells via inhibition of MAPKs/NF-κB signaling pathway. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Yoon, D.; Kim, G.S.; Lee, D.Y. The ethanolic extract of Curcuma longa grown in Korea exhibits anti-neuroinflammatory effects by activating of nuclear transcription factor erythroid-2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 signaling pathway. BMC complementary medicine and therapies 2022, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, C.S.; Lim, J.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.P.; Yang, S.A. The protective effect of fermented Curcuma longa L. on memory dysfunction in oxidative stress-induced C6 gliomal cells, proinflammatory-activated BV2 microglial cells, and scopolamine-induced amnesia model in mice. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2017, 17, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgonetti, V.; Benatti, C.; Governa, P.; Isoldi, G.; Pellati, F.; Alboni, S.; Tascedda, F.; Montopoli, M.; Galeotti, N.; Manetti, F.; et al. Non-psychotropic Cannabis sativa L. phytocomplex modulates microglial inflammatory response through CB2 receptors-, endocannabinoids-, and NF-κB-mediated signaling. Phytotherapy research : PTR 2022, 36, 2246–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Jakaria, M.; Yu, Y.J.; Ahn, J.Y.; Kim, I.S.; Choi, D.K. Dioscorea nipponica Makino Rhizome Extract and Its Active Compound Dioscin Protect against Neuroinflammation and Scopolamine-Induced Memory Deficits. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.Y.; Zhou, Y.L.; He, D.H.; Liu, W.; Fan, X.Z.; Wang, Q.; Pan, H.F.; Cheng, Y.X.; Liu, Y.Q. Centipeda minima extract exerts antineuroinflammatory effects via the inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathway. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2020, 67, 153164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.H.; Li, W.; Go, Y.; Oh, Y.C. Atractylodis Rhizoma Alba Attenuates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia upon LPS Stimulation by Inducing HO-1 Activity and Inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.H.; Ma, S.X.; Ko, Y.H.; Seo, J.Y.; Lee, B.R.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, C.G. Vaccinium bracteatum Thunb. Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Activity by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Biomolecules & therapeutics 2016, 24, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H.; Ma, S.X.; Hong, S.I.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, C.G. Lonicera japonica THUNB. Extract Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Inflammatory Responses by Suppressing NF-κB Signaling in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Journal of medicinal food 2015, 18, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, H.W.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Seong, S.J.; Jin, M.L.; Ryu, E.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.J. Bambusae Caulis in Taeniam modulates neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory effects in hippocampal and microglial cells via HO-1- and Nrf-2-mediated pathways. International journal of molecular medicine 2012, 30, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.W.; Yoon, C.H.; Park, K.M.; Han, H.S.; Park, Y.K. Hexane fraction of Zingiberis Rhizoma Crudus extract inhibits the production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells via the NF-kappaB pathway. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2009, 47, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallstig, E.; McCabe, B.D.; Schneider, B.L. The Links between ALS and NF-kappaB. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Lenardo, M.J.; Baltimore, D. 30 Years of NF-kappaB: A Blossoming of Relevance to Human Pathobiology. Cell 2017, 168, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinatizadeh, M.R.; Schock, B.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Zarandi, P.K.; Jalali, S.A.; Miri, S.R. The Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes Dis 2021, 8, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.E.; Walker, A.K.; Weickert, C.S. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia: the role of nuclear factor kappa B. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, E.; Motolani, A.; Campos, L.; Lu, T. The Pivotal Role of NF-kB in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.; Vargas, J.; Hoffmann, A. Signaling via the NFkappaB system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2016, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Bueno Ottoboni, A.M.M.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Guiguer, E.L.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Flato, U.A.P.J.C.r.i.f.s.

- Sul, O.J.; Ra, S.W. Quercetin Prevents LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation by Modulating NOX2/ROS/NF-kB in Lung Epithelial Cells. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.S.; Rai, S.N.; Birla, H.; Zahra, W.; Rathore, A.S.; Singh, S.P. NF-kappaB-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease and Potential Therapeutic Effect of Polyphenols. Neurotox Res 2020, 37, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, G.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; He, X. Quercetin inhibits TNF-alpha induced HUVECs apoptosis and inflammation via downregulating NF-kB and AP-1 signaling pathway in vitro. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e22241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nennig, S.E.; Schank, J.R. The Role of NFkB in Drug Addiction: Beyond Inflammation. Alcohol Alcohol 2017, 52, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. Targeting NF-kappaB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.C. The non-canonical NF-kappaB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, R.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Yang, C.M. NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways in Neurological Inflammation: A Mini Review. Front Mol Neurosci 2015, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusso, M.; Lunardi, V.; Franceschini, D.; Pagetta, A.; Lo, R.; Stifani, S.; Frigo, A.C.; Giusti, P.; Moro, S. Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin attenuate microglia inflammatory response via TLR4/NF-kB pathway. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabab, T.; Khanabdali, R.; Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Kadir, H.A.; Mohan, G. Neuroinflammation pathways: a general review. Int J Neurosci 2017, 127, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.K.; Saijo, K.; Winner, B.; Marchetto, M.C.; Gage, F.H. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell 2010, 140, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Rund, L.A.; Vailati-Riboni, M.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Johnson, R.W. Copper-Binding Peptides Attenuate Microglia Inflammation through Suppression of NF-kB Pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res 2021, 65, e2100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Rustamov, N.; Roh, Y.S. The Roles of NFR2-Regulated Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Quality Control in Chronic Liver Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seen, S. Chronic liver disease and oxidative stress - a narrative review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 15, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, F. Chemical Basis of Reactive Oxygen Species Reactivity and Involvement in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A, N.K.; Sharma, R.P.; Colangelo, A.M.; Ignatenko, A.; Martorana, F.; Jennen, D.; Briede, J.J.; Brady, N.; Barberis, M.; Mondeel, T.; et al. ROS networks: designs, aging, Parkinson's disease and precision therapies. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2020, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenetti, L.; Manzoli, R.; Rubin, M.; Cozza, G.; Moro, E. Monitoring Nrf2/ARE Pathway Activity with a New Zebrafish Reporter System. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Patil, J.; D'Angelo, B.; Weber, S.G.; Mallard, C. NRF2-regulation in brain health and disease: implication of cerebral inflammation. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Xia, M. Cell-Based Assays to Identify Modulators of Nrf2/ARE Pathway. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2474, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivandzade, F.; Prasad, S.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. NRF2 and NF-қB interplay in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders: Molecular mechanisms and possible therapeutic approaches. Redox Biol 2019, 21, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dordoe, C.; Wang, X.; Lin, P.; Wang, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Fang, Y.; Liang, F.; Ye, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Non-mitogenic fibroblast growth factor 1 protects against ischemic stroke by regulating microglia/macrophage polarization through Nrf2 and NF-kappaB pathways. Neuropharmacology 2022, 212, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; An, C.; Gao, Y.; Leak, R.K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F. Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol 2013, 100, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Duan, H.; Li, R.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: An important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J Adv Res 2021, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, Z. The Nrf2 Pathway in Liver Diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 826204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells 2011, 16, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayalan Naidu, S.; Muramatsu, A.; Saito, R.; Asami, S.; Honda, T.; Hosoya, T.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Suzuki, T.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. C151 in KEAP1 is the main cysteine sensor for the cyanoenone class of NRF2 activators, irrespective of molecular size or shape. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fao, L.; Mota, S.I.; Rego, A.C. Shaping the Nrf2-ARE-related pathways in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Ageing Res Rev 2019, 54, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced endothelial injuries. J Endocrinol 2015, 225, R83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Maio, M.C.; Minniti, G.; de Goes Correa, N.; Barbalho, S.M.; Quesada, K.; Guiguer, E.L.; Sloan, K.P.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araujo, A.C.; et al. Effects of Medicinal Plants and Phytochemicals in Nrf2 Pathways during Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Related Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.L., K.; Geng, M.; Gao, P.; Wu, X.; Hai, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Hayes, JD.; Wang, XJ.; Tang, X. RXRα inhibits the NRF2-ARE signaling pathway through a direct interaction with the Neh7 domain of NRF2. Cancer Research 2013, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.H.; Liu, J. Relationship between oxidative stress and nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 signaling in diabetic cardiomyopathy (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Gupta, D. Crosstalk of toll-like receptors signaling and Nrf2 pathway for regulation of inflammation. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 108, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, P.; Cucullo, L. Pathobiology of tobacco smoking and neurovascular disorders: untied strings and alternative products. Fluids Barriers CNS 2015, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumaoglu, A.; Agkaya, A.O.; Ozkul, Z. Effect of the Lipid Peroxidation Product 4-Hydroxynonenal on Neuroinflammation in Microglial Cells: Protective Role of Quercetin and Monochloropivaloylquercetin. Turk J Pharm Sci 2019, 16, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, B.I.; Ucar, G.; Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. Pharmacological Protection against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Regulating the Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; He, W.B.; Chen, C.; Luo, P.; Liu, D.D.; Ai, Q.D.; Gong, H.F.; Wang, Z.Z.; et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against ischemic/reperfusion-induced neuronal injury through miR-144/Nrf2/ARE pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2019, 40, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrozova, N.; Ulrichova, J.; Galandakova, A. Models for the study of skin wound healing. The role of Nrf2 and NF-kappaB. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2017, 161, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; He, X. Molecular basis of electrophilic and oxidative defense: promises and perils of Nrf2. Pharmacol Rev 2012, 64, 1055–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Liu, P.; Luo, G.; Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chen, H.; Wu, T.; Tillotson, J.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. p97 Negatively Regulates NRF2 by Extracting Ubiquitylated NRF2 from the KEAP1-CUL3 E3 Complex. Mol Cell Biol 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanen, E.; Kuosmanen, S.M.; Leinonen, H.; Levonen, A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: Mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol 2013, 1, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Mimura, J.; Yamamoto, M. Discovery of the negative regulator of Nrf2, Keap1: a historical overview. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010, 13, 1665–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Du, H.; Shi, Y.; Xiu, M.; Liu, Y.; He, J. Natural products targeting Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 164, 114950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Fu, M.D.; Liu, K.; Duan, X.C. Therapeutic effect of Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway-related drugs on age-related eye diseases through anti-oxidative stress. Int J Ophthalmol 2021, 14, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Botchway, B.O.A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Ellagic acid activates the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway in improving Parkinson's disease: A review. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 156, 113848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Inoue, J.; Iso, T.; Wells, G.; Moore, T.W.; Mizushima, T.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kasai, T.; Kamei, T.; et al. Molecular basis for the disruption of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction via Hinge & Latch mechanism. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulasov, A.V.; Rosenkranz, A.A.; Georgiev, G.P.; Sobolev, A.S. Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling: Towards specific regulation. Life Sci 2022, 291, 120111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, Y.; Kobayashi, M. Conservation of the Keap1-Nrf2 System: An Evolutionary Journey through Stressful Space and Time. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Pi, J.; Zhang, Q. Signal amplification in the KEAP1-NRF2-ARE antioxidant response pathway. Redox Biol 2022, 54, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pi, J.; Zhang, Q. Mathematical modeling reveals quantitative properties of KEAP1-NRF2 signaling. Redox Biol 2021, 47, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Long, D. Nrf2 and Ferroptosis: A New Research Direction for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cores, Á.; Piquero, M.; Villacampa, M.; León, R.; Menéndez, J.C. NRF2 Regulation Processes as a Source of Potential Drug Targets against Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Johnson, J.A. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1842, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.J.; Lv, C.H.; Chen, Z.; Shi, M.; Zeng, C.X.; Hou, D.X.; Qin, S. The Regulatory Effect of Phytochemicals on Chronic Diseases by Targeting Nrf2-ARE Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, R.; Maccallini, C.; Bellezza, I. Activators of Nrf2 to Counteract Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentho, E.; Weis, S. DAMPs and Innate Immune Training. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 699563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Wang, X. Nuclear Alarmin Cytokines in Inflammation. J Immunol Res 2020, 2020, 7206451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oronsky, B.; Caroen, S.; Reid, T. What Exactly Is Inflammation (and What Is It Not?). Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernyak, B.V.; Lyamzaev, K.G. Innate Immunity and Phenoptosis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2022, 87, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Zou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, Q. Mechanism of inflammasomes in cancer and targeted therapies. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1133013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Callaway, J.B.; Ting, J.P. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med 2015, 21, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, D.; Vande Walle, L.; Lamkanfi, M. Therapeutic modulation of inflammasome pathways. Immunol Rev 2020, 297, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hauenstein, A.V. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Mechanism of action, role in disease and therapies. Mol Aspects Med 2020, 76, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, P. Activation and Pharmacological Regulation of Inflammasomes. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, J.A.; Mathur, A.; Ngo, C.; Man, S.M. Cytosolic Recognition of Microbes and Pathogens: Inflammasomes in Action. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2018, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Shi, X.; Jin, H.; Hu, W. The roles of inflammasomes in cancer. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1195572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Fu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, W. The contrasting roles of inflammasomes in cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2018, 8, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christgen, S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Inflammasomes and the fine line between defense and disease. Curr Opin Immunol 2020, 62, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelut-Carneiro, N.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Inflammasomes. Curr Biol 2020, 30, R689–r694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Chai, J. Assembly and Architecture of NLR Resistosomes and Inflammasomes. Annu Rev Biophys 2023, 52, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fan, J.; Billiar, T.R.; Scott, M.J. Inflammasome and autophagy regulation - a two-way street. Mol Med 2017, 23, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Qin, T.; Yue, Y.; Qian, W.; Li, L. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 4063562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Song, C.; Gao, C.; He, Y.; Shang, Y. Negative regulator NLRC3: Its potential role and regulatory mechanism in immune response and immune-related diseases. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1012459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olona, A.; Leishman, S.; Anand, P.K. The NLRP3 inflammasome: regulation by metabolic signals. Trends Immunol 2022, 43, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, C.; Vong, C.T.; Tao, H.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Rhein regulates redox-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in intestinal inflammation through macrophage-activated crosstalk. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 1978–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, A. The NLRP3-Inflammasome in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duez, H.; Pourcet, B. Nuclear Receptors in the Control of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 630536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, P.I.; Lee, B.; Hoyle, C.; Yu, S.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Lowe, M.; Brough, D. The NLRP3-inflammasome as a sensor of organelle dysfunction. J Cell Biol 2020, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Therapeutic regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases. Arch Pharm Res 2021, 44, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.; Kanneganti, T.D. Inflammasome activation and assembly at a glance. J Cell Sci 2017, 130, 3955–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulte, D.; Rigamonti, C.; Romano, A.; Mortellaro, A. Inflammasomes: Mechanisms of Action and Involvement in Human Diseases. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Wu, H. Structural Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Assembly and Activation. Annu Rev Immunol 2023, 41, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Li, T. Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome by Phosphorylation. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zheng, C.; Xu, J.; Ma, S.; Jia, H.; Yan, M.; An, F.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, J.; Bian, H. Race between virus and inflammasomes: inhibition or escape, intervention and therapy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1173505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.L.; Biggs, K.E.; Rankin, B.E.; Havrda, M.C. NLRP3 inflammasome in neurodegenerative disease. Transl Res 2023, 252, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Silwal, P.; Sasakawa, C.; Jo, E.K. An update on the regulatory mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, G.; Xiao, X.; Bai, Z. The mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its pharmacological inhibitors. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1109938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasizzo, M.; Kopitar-Jerala, N. Interplay Between NLRP3 Inflammasome and Autophagy. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 591803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, C.; Antonioli, L.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Blandizzi, C.; Fornai, M. Canonical and Non-Canonical Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome at the Crossroad between Immune Tolerance and Intestinal Inflammation. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, W. NLRP3 Inflammasome-A Key Player in Antiviral Responses. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, G.; Buscetta, M.; Cimino, M.; Dino, P.; Bucchieri, F.; Cipollina, C. Cellular Models and Assays to Study NLRP3 Inflammasome Biology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Mei, X. Role of NLRP3 Inflammasomes in Neuroinflammation Diseases. Eur Neurol 2020, 83, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.Q.; Le, W. NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation and Related Mitochondrial Impairment in Parkinson's Disease. Neurosci Bull 2023, 39, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X. Interaction between autophagy and the NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 1018848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soraci, L.; Gambuzza, M.E.; Biscetti, L.; Laganà, P.; Lo Russo, C.; Buda, A.; Barresi, G.; Corsonello, A.; Lattanzio, F.; Lorello, G.; et al. Toll-like receptors and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pathways in Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J Neurol 2023, 270, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Ng, W.L.; Goh, S.Y.; Gulam, M.Y.; Wang, L.F.; Tan, E.K.; Ahn, M.; Chao, Y.X. Targeting the inflammasome in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 957705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barczuk, J.; Siwecka, N.; Lusa, W.; Rozpedek-Kaminska, W.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Targeting NLRP3-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severini, C.; Barbato, C.; Di Certo, M.G.; Gabanella, F.; Petrella, C.; Di Stadio, A.; de Vincentiis, M.; Polimeni, A.; Ralli, M.; Greco, A. Alzheimer's Disease: New Concepts on the Role of Autoimmunity and NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Pathogenesis of the Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol 2021, 19, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L. The Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Alzheimer's Disease and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 845185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wei, S.; Deng, J.; Feng, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, M. A novel strategy for bioactive natural products targeting NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1077222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Cai, X.; Jin, K.; Wang, Q. Editorial: The NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and its related mitochondrial impairment in neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 1118281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Guan, R.; Zou, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J. NLRP3 deficiency protects against hypobaric hypoxia induced neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 255, 114828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhao, T.; Liu, M.; Cao, D.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xia, M.; Wang, X.; Zheng, T.; Liu, C.; et al. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome in Translational Treatment of Nervous System Diseases: An Update. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 707696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-deGuise, C.; Serra-Ruiz, X.; Lastiri, E.; Borruel, N. JAK inhibitors: A new dawn for oral therapies in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1089099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Alexander, M.; Gadina, M.; O'Shea, J.J.; Meylan, F.; Schwartz, D.M. JAK-STAT signaling in human disease: From genetic syndromes to clinical inhibition. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 148, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rah, B.; Rather, R.A.; Bhat, G.R.; Baba, A.B.; Mushtaq, I.; Farooq, M.; Yousuf, T.; Dar, S.B.; Parveen, S.; Hassan, R.; et al. JAK/STAT Signaling: Molecular Targets, Therapeutic Opportunities, and Limitations of Targeted Inhibitions in Solid Malignancies. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 821344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Jiang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Hong, F.; Hao, D. Regulation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in spinal cord injury: an updated review. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1276445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Low, J.T.; Silke, J.; O'Reilly, L.A. Digesting the Role of JAK-STAT and Cytokine Signaling in Oral and Gastric Cancers. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 835997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, G.A.; Williams, J.J.L.; Nasim, M.T.; Palmer, T.M. Targeting SOCS Proteins to Control JAK-STAT Signalling in Disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2019, 40, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.; Bakay, M.; Hakonarson, H. SOCS-JAK-STAT inhibitors and SOCS mimetics as treatment options for autoimmune uveitis, psoriasis, lupus, and autoimmune encephalitis. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1271102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Gibson, S.A.; Benveniste, E.N.; Qin, H. Opportunities for Translation from the Bench: Therapeutic Intervention of the JAK/STAT Pathway in Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Crit Rev Immunol 2015, 35, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.Y.; Li, C.J.; Yong, S.B. Emerging trends in clinical research on Janus kinase inhibitors for atopic dermatitis treatment. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 124, 111029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agashe, R.P.; Lippman, S.M.; Kurzrock, R. JAK: Not Just Another Kinase. Mol Cancer Ther 2022, 21, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, P.; Milara, J.; Roger, I.; Cortijo, J. Role of JAK/STAT in Interstitial Lung Diseases; Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, R.L.; Wang, Y.; Cheon, H.; Kanno, Y.; Gadina, M.; Sartorelli, V.; Horvath, C.M.; Darnell, J.E., Jr.; Stark, G.R.; O'Shea, J.J. The JAK-STAT pathway at 30: Much learned, much more to do. Cell 2022, 185, 3857–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somade, O.T.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Ajiboye, B.O.; Osukoya, O.A. Syringic acid demonstrates an anti-inflammatory effect via modulation of the NF-κB-iNOS-COX-2 and JAK-STAT signaling pathways in methyl cellosolve-induced hepato-testicular inflammation in rats. Biochem Biophys Rep 2023, 34, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J. The role of JAK/STAT signaling pathway in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury and the therapeutic effect of traditional Chinese medicine: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e35890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigdevall, L.; Michiels, C.; Stewardson, C.; Dumoutier, L. JAK/STAT: Why choose a classical or an alternative pathway when you can have both? J Cell Mol Med 2022, 26, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaawy, H.E.; Ryan, B.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Pine, S.R. JAK/STAT of all trades: linking inflammation with cancer development, tumor progression and therapy resistance. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarapultsev, A.; Gusev, E.; Komelkova, M.; Utepova, I.; Luo, S.; Hu, D. JAK-STAT signaling in inflammation and stress-related diseases: implications for therapeutic interventions. Mol Biomed 2023, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, K.; Medina, J.; Orrego-Cardozo, M.; Restrepo de Mejía, F.; Elcoroaristizabal, X.; Naranjo Galvis, C.A. Inflammatory gene expression profiling in peripheral blood from patients with Alzheimer's disease reveals key pathways and hub genes with potential diagnostic utility: a preliminary study. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Singh, M.K.; Shyam, H.; Mishra, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Kushwaha, J. Role of JAK/STAT in the Neuroinflammation and its Association with Neurological Disorders. Ann Neurosci 2021, 28, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.L.; Zhou, M.; Chin, E.W.M.; Amarnath, G.; Cheah, C.H.; Ng, K.P.; Kandiah, N.; Goh, E.L.K.; Chiam, K.H. Alzheimer's Disease Blood Biomarkers Associated With Neuroinflammation as Therapeutic Targets for Early Personalized Intervention. Front Digit Health 2022, 4, 875895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.R.; Desai, R.J.; Navakkode, S.; Wong, L.W.; Anerillas, C.; Loeffler, T.; Schilcher, I.; Mahesri, M.; Chin, K.; Horton, D.B.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine lowers Alzheimer's disease and related dementias risk and rescues molecular phenotypes related to Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusek, M.; Smith, J.; El-Khatib, K.; Aikins, K.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Pluta, R. The Role of the JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease: New Potential Treatment Target. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Ribe, E.; Thei, L.; Furlong, L.; Mayer, M.A.; Quan, J.; Richardson, J.C.; Cavanagh, J.; Consortium, N.; Lovestone, S. Genetic and Real-World Clinical Data, Combined with Empirical Validation, Nominate Jak-Stat Signaling as a Target for Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutic Development. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porro, C.; Cianciulli, A.; Trotta, T.; Lofrumento, D.D.; Panaro, M.A. Curcumin Regulates Anti-Inflammatory Responses by JAK/STAT/SOCS Signaling Pathway in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Biology (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Gibson, S.A.; Buckley, J.A.; Qin, H.; Benveniste, E.N. Role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in regulation of innate immunity in neuroinflammatory diseases. Clin Immunol 2018, 189, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Buckley, J.A.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Fox, T.H., 3rd; Meares, G.P.; Yu, H.; Yan, Z.; Harms, A.S.; Li, Y.; et al. Inhibition of the JAK/STAT Pathway Protects Against α-Synuclein-Induced Neuroinflammation and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 5144–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gu, X.; Mao, Y.; Peng, B. The origin and repopulation of microglia. Developmental neurobiology 2022, 82, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, S.C.; Bollinger, J.L.; Wohleb, E.S. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. Journal of neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M.; Jung, S.; Priller, J. Microglia biology: one century of evolving concepts. Cell 2019, 179, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Castillo, A.I.; Sepúlveda, M.R.; Marín-Teva, J.L.; Cuadros, M.A.; Martín-Oliva, D.; González-Rey, E.; Delgado, M.; Neubrand, V.E. Switching roles: beneficial effects of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells on microglia and their implication in neurodegenerative diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Itriago, A.; Radford, R.A.; Aramideh, J.A.; Maurel, C.; Scherer, N.M.; Don, E.K.; Lee, A.; Chung, R.S.; Graeber, M.B.; Morsch, M. Microglia morphophysiological diversity and its implications for the CNS. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 997786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullotta, G.S.; Costantino, G.; Sortino, M.A.; Spampinato, S.F. Microglia and the blood–brain barrier: An external player in acute and chronic neuroinflammatory conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.; Yeo, I.-J.; Hong, J.-T.; Eo, S.-K.; Lee, D.; Kim, K. Side-Chain Immune Oxysterols Induce Neuroinflammation by Activating Microglia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Che, J.; Zhang, J. Emerging non-proinflammatory roles of microglia in healthy and diseased brains. Brain Research Bulletin 2023, 199, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Z.; Yan, H.; Tang, B.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Meng, Q. Microglia-containing human brain organoids for the study of brain development and pathology. Molecular Psychiatry 2023, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annual review of immunology 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsudaira, T.; Prinz, M. Life and death of microglia: Mechanisms governing microglial states and fates. Immunology Letters 2022, 245, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright-Jin, E.C.; Gutmann, D.H. Microglia as dynamic cellular mediators of brain function. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2019, 25, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Martins, S.; Ferreira, P.A.; Cardoso, A.M.; Guedes, J.R.; Peça, J.; Cardoso, A.L. The old guard: Age-related changes in microglia and their consequences. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2021, 197, 111512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Onaizi, M.; Al-Khalifah, A.; Qasem, D.; ElAli, A. Role of microglia in modulating adult neurogenesis in health and neurodegeneration. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, G.; Marrocco, F.; Limatola, C. Microglial cells: sensors for neuronal activity and microbiota-derived molecules. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 1011129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Mao, Y.; Peng, B. Novel microglia-based therapeutic approaches to neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroscience bulletin 2023, 39, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Taso, O.; Wang, R.; Bayram, S.; Graham, A.C.; Garcia-Reitboeck, P.; Mallach, A.; Andrews, W.D.; Piers, T.M.; Botia, J.A. Trem2 promotes anti-inflammatory responses in microglia and is suppressed under pro-inflammatory conditions. Human molecular genetics 2020, 29, 3224–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Arrifano, G.P.; Lopes-Araújo, A.; Santos-Sacramento, L.; Takeda, P.Y.; Anthony, D.C.; Malva, J.O.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E. What do microglia really do in healthy adult brain? Cells 2019, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Var, S.R.; Strell, P.; Johnson, S.T.; Roman, A.; Vasilakos, Z.; Low, W.C. Transplanting microglia for treating CNS injuries and neurological diseases and disorders, and prospects for generating exogenic microglia. Cell transplantation 2023, 32, 09636897231171001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Ruiz, M.A.; Guerrero-Vargas, N.N.; Lagunes-Cruz, A.; González-González, S.; García-Aviles, J.E.; Hurtado-Alvarado, G.; Mendez-Hernández, R.; Chavarría-Krauser, A.; Morin, J.P.; Arriaga-Avila, V. Circadian modulation of microglial physiological processes and immune responses. Glia 2023, 71, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.L.; Nissen, J.C. The Pathological Activation of Microglia Is Modulated by Sexually Dimorphic Pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Translational neurodegeneration 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianciulli, A.; Calvello, R.; Ruggiero, M.; Panaro, M.A. Inflammaging and brain: Curcumin and its beneficial potential as regulator of microglia activation. Molecules 2022, 27, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, S.F.; Elbadry, A.M.; Elbokhomy, A.S.; Salama, G.A.; Salama, R.M. The dual face of microglia (M1/M2) as a potential target in the protective effect of nutraceuticals against neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Aging 2023, 4, 1231706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C.; Valle, M.S.; Russo, A.; Malaguarnera, L. The interplay between ghrelin and microglia in neuroinflammation: implications for obesity and neurodegenerative diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 13432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tong, F.; Li, H.; Bin, Y.; Ding, P.; Peng, L.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X. Maturation, morphology, and function: the decisive role of intestinal flora on microglia: a review. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 2023, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.Y.; McNeely, T.L.; Baker, D.J. Untangling senescent and damage-associated microglia in the aging and diseased brain. The FEBS journal 2023, 290, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierre, A.D.; Wu, L.J. How microglia sense and regulate neuronal activity. Glia 2021, 69, 1637–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristovska, I.; Robert, M.; Combet, K.; Honnorat, J.; Comte, J.; Pascual, O. Sleep decreases neuronal activity control of microglial dynamics in mice. Nature communications 2022, 13, 6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, A.; Kato, D.; Wake, H. Microglial process dynamics depend on astrocyte and synaptic activity. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science 2023, 85, 772. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, K.; Lee, S.J.; Mook-Jung, I. White matter-associated microglia: New players in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 75, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Bougea, A.; Hatzimanolis, A.; Scarmeas, N.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Unraveling the Potential Underlying Mechanisms of Mild Behavioral Impairment: Focusing on Amyloid and Tau Pathology. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, O.; Ji, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Gao, W. New insights in drug development for Alzheimer's disease based on microglia function. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 140, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varo, R.; Mejias-Ortega, M.; Fernandez-Valenzuela, J.J.; Nuñez-Diaz, C.; Caceres-Palomo, L.; Vegas-Gomez, L.; Sanchez-Mejias, E.; Trujillo-Estrada, L.; Garcia-Leon, J.A.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; et al. Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer's Disease: An Integrative Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendimu, M.Y.; Hooks, S.B. Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, R.; Tsuda, M. The Functions and Phenotypes of Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.-H.; Zhang, L.-J.; Wang, S.-Y.; Deng, Y.-D.; Zhou, H.-S.; Chen, D.-Q.; Zhang, L.-C. The role of microglia in Alzheimer's disease and progress of treatment. Ibrain 2022, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Dong, Y.; Ma, J.; Pan, R.; Liao, Y.; Kong, X.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Chen, P.; Wang, L.; et al. Microglial Calhm2 regulates neuroinflammation and contributes to Alzheimer's disease pathology. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewcock, J.W.; Schlepckow, K.; Di Paolo, G.; Tahirovic, S.; Monroe, K.M.; Haass, C. Emerging Microglia Biology Defines Novel Therapeutic Approaches for Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron 2020, 108, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvaso, A.; Gatti, A.; Negro, G.; Calatozzolo, C.; Medici, V.; Poloni, T.E. Microglial Senescence and Activation in Healthy Aging and Alzheimer's Disease: Systematic Review and Neuropathological Scoring. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Li, X. Different phenotypes of microglia in animal models of Alzheimer disease. Immun Ageing 2022, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L.; Hashimoto, M.; Wei, J. Microglial response to aging and neuroinflammation in the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 2024, 19, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Victor, M.B.; Park, Y.P.; Xiong, X.; Scannail, A.N.; Leary, N.; Prosper, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Luna, X.; Boix, C.A.; et al. Human microglial state dynamics in Alzheimer's disease progression. Cell 2023, 186, 4386–4403.e4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapser, J.D.; Spangenberg, E.E.; Barahona, R.A.; Arreola, M.A.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Green, K.N. Microglia facilitate loss of perineuronal nets in the Alzheimer's disease brain. EBioMedicine 2020, 58, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizkar, S.; Arzberger, T.; Brendel, M.; Kleinberger, G.; Deussing, M.; Focke, C.; Nuscher, B.; Xiong, M.; Ghasemigharagoz, A.; Katzmarski, N.; et al. Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyaeva, L.; Ratti, G.; Teirilä, L.; Fudo, S.; Rankka, U.; Pelkonen, A.; Korhonen, P.; Leskinen, K.; Keskitalo, S.; Salokas, K.; et al. Reduced binding of apoE4 to complement factor H promotes amyloid-β oligomerization and neuroinflammation. EMBO Rep 2023, 24, e56467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilandt, W.J.; Ngu, H.; Gogineni, A.; Lalehzadeh, G.; Lee, S.H.; Srinivasan, K.; Imperio, J.; Wu, T.; Weber, M.; Kruse, A.J.; et al. Trem2 Deletion Reduces Late-Stage Amyloid Plaque Accumulation, Elevates the Aβ42:Aβ40 Ratio, and Exacerbates Axonal Dystrophy and Dendritic Spine Loss in the PS2APP Alzheimer's Mouse Model. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 1956–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sudan, R.; Peng, V.; Zhou, Y.; Du, S.; Yuede, C.M.; Lei, T.; Hou, J.; Cai, Z.; Cella, M.; et al. TREM2 drives microglia response to amyloid-β via SYK-dependent and -independent pathways. Cell 2022, 185, 4153–4169.e4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, J.; Madden, B.J.; Charlesworth, C.M.; Martens, Y.A.; Liu, C.C.; Knight, J.; Ikezu, T.C.; Kurti, A.; et al. Trem2 H157Y increases soluble TREM2 production and reduces amyloid pathology. Mol Neurodegener 2023, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Manchanda, P.; Paouri, E.; Bisht, K.; Sharma, K.; Wijewardhane, P.R.; Randolph, C.E.; Clark, M.G.; Fine, J.; Thayer, E.A.; et al. Amyloid β Induces Lipid Droplet-Mediated Microglial Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, C.M.; Pham, K.; Machalinski, A.H.; Porter, H.L.; Blankenship, H.E.; Tooley, K.; Stout, M.B.; Rice, H.C.; Sharpe, A.L.; Beckstead, M.J.; et al. Microglial MHC-I induction with aging and Alzheimer's is conserved in mouse models and humans. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, R.; Ferreira, E.; Knowles, S.; Fux, C.; Rodin, A.; Winslow, W.; Oddo, S. Lifelong choline supplementation ameliorates Alzheimer's disease pathology and associated cognitive deficits by attenuating microglia activation. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, E.K.J.; Boer, G.J. Parkinson's Disease: A Tale of Many Players. Med Princ Pract 2023, 32, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, K.-M.; Roussaki, I.; Demestichas, K. Internet of Things Technologies and Machine Learning Methods for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis, Monitoring and Management: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, H.N.; Esteves, A.R.; Empadinhas, N.; Cardoso, S.M. Parkinson's Disease: A Multisystem Disorder. Neurosci Bull 2023, 39, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.; MacAskill, M.; Pascoe, M.; Anderson, T.; Heron, C.L. Dimensions of apathy in Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav 2023, 13, e2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C.; Jost, W.H. Pain in Parkinson's Disease: Pathophysiology, Classification and Treatment. J Integr Neurosci 2023, 22, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, D.M.; Brown, P. Moving, fast and slow: behavioural insights into bradykinesia in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2023, 146, 3576–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioli, M.; Cattaneo, Z.; Rusconi, M.L.; Blandini, F.; Tettamanti, M. Action and emotion perception in Parkinson's disease: A neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin 2022, 35, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, M.F.; Bologna, M. The pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease tremor. J Neurol Sci 2022, 435, 120196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrichs, E.; Alves, G.; Benjaminsen, E.; Johansen, K.K.; Tysnes, O.B. Treatment of motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2023, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.K.; Tanner, C.M.; Brundin, P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med 2020, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, A.R.; Reynolds, R.H.; O'Callaghan, B.; García-Ruiz, S.; Gil-Martínez, A.L.; Botía, J.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Ryten, M. The non-specific lethal complex regulates genes and pathways genetically linked to Parkinson's disease. Brain 2023, 146, 4974–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Marmolejo-Garza, A.; de Pádua, V.P.; Eggen, B.; Boddeke, E.; Dolga, A.M. Microglia alterations in neurodegenerative diseases and their modeling with human induced pluripotent stem cell and other platforms. Prog Neurobiol 2020, 190, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Joers, V.; Tansey, M.G.; McKernan, D.P.; Dowd, E. Microglial Phenotypes and Their Relationship to the Cannabinoid System: Therapeutic Implications for Parkinson's Disease. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harry, G.J. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Events-An Initiator or a Significant Other? Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofaris, G.K. Initiation and progression of α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson's disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 79, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toni, M. Special Issue "Neurobiology of Protein Synuclein". Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badanjak, K.; Fixemer, S.; Smajić, S.; Skupin, A.; Grünewald, A. The Contribution of Microglia to Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basellini, M.J.; Kothuis, J.M.; Comincini, A.; Pezzoli, G.; Cappelletti, G.; Mazzetti, S. Pathological Pathways and Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson's Disease: A View from the Periphery. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2023, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Rey, N.L.; Tyson, T.; Esquibel, C.; Meyerdirk, L.; Schulz, E.; Pierce, S.; Burmeister, A.R.; Madaj, Z.; Steiner, J.A.; et al. Microglia affect α-synuclein cell-to-cell transfer in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurodegener 2019, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, T.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Hong, J.; Hashimoto, M.; Wei, J. The reciprocal interactions between microglia and T cells in Parkinson’s disease: a double-edged sword. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Zheng, R.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, Z.H.; Xue, N.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, B.R.; Pu, J.L. Parkin regulates microglial NLRP3 and represses neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, X.; Xie, F.; Zhang, J.; Gu, R.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, J. Deletion of Calhm2 alleviates MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease pathology by inhibiting EFHD2-STAT3 signaling in microglia. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1809–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basurco, L.; Abellanas, M.A.; Ayerra, L.; Conde, E.; Vinueza-Gavilanes, R.; Luquin, E.; Vales, A.; Vilas, A.; Martin-Uriz, P.S.; Tamayo, I.; et al. Microglia and astrocyte activation is region-dependent in the α-synuclein mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Glia 2023, 71, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hamade, M.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Axtell, R.; Giri, S.; Mao-Draayer, Y. Current and Future Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charabati, M.; Wheeler, M.A.; Weiner, H.L.; Quintana, F.J. Multiple sclerosis: Neuroimmune crosstalk and therapeutic targeting. Cell 2023, 186, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mey, G.M.; Mahajan, K.R.; DeSilva, T.M. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. WIREs Mech Dis 2023, 15, e1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correale, J.; Ysrraelit, M.C. Multiple Sclerosis and Aging: The Dynamics of Demyelination and Remyelination. ASN Neuro 2022, 14, 17590914221118502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellen, O.; Ye, S.; Nheu, D.; Dass, M.; Pagnin, M.; Ozturk, E.; Theotokis, P.; Grigoriadis, N.; Petratos, S. The Heterogeneous Multiple Sclerosis Lesion: How Can We Assess and Modify a Degenerating Lesion? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, V.W. Microglia in multiple sclerosis: Protectors turn destroyers. Neuron 2022, 110, 3534–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Dai, C.; Zhou, X.; Barnes, J.A.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Shingu, T.; Heimberger, A.B.; Chen, Y.; et al. Qki is an essential regulator of microglial phagocytosis in demyelination. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Sun, M.; Wu, N.; Liu, B.; Yi, X.; Ge, R.; Fan, X. Microglia in the context of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1157287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Fang, X.; Liu, W.; Sun, R.; Zhou, J.; Pu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Sun, D.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, P.; et al. Microglia Regulate Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity via MiR-126a-5p/MMP9 Axis during Inflammatory Demyelination. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022, 9, e2105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plants | Models | Interventions | Mechanisms | Clinical Implications | Limitations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleistocalyx nervosum var. paniala (Ferulic acid, aurentiacin, brassitin, ellagic acid, alpinetin and resveratrol) |

TNF-α-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 5, 10 or 25 μg/mL CNSE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ COX-2 activation, ↓ iNOS function, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression, ↓ p38MAPK and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation, ↓ NF-κB activation, ↓ p65 and IκB phosphorylation, ↑ HO-1 induction (in vitro) | Potential for new anti-inflammatory agents targeting neurodegenerative diseases. Could pave the way for natural, multi-targeted treatments. | Findings are promising but confined to cellular models; lacking animal studies and in-depth safety profiles. | [38] |

| LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100 μg/mL CNSE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO production, ↓ iNOS mRNA expression, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression, ↓ MAPK phosphorylation, ↓ p-JNK, p-ERK 1/2 and p-p38 levels, ↓ NF-κB activation (in vitro) | Could contribute to the development of targeted anti-inflammatory therapies with fewer side effects. | Effects are robust in vitro but lack corroboration in animal models and human trials. | [39] | |

| Curcuma longa (Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 150 or 200 μg/mL CLE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO production, ↓ PGE2 production, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression, ↓ NF-κB activation, ↓ IκB-α phosphorylation and degradation, ↓ p65 nuclear translocation, ↓ MAPK (p38, ERK, and JNK) phosphorylation, ↑ HO-1 expression, ↑ Nrf2 nuclear translocation (in vitro) | Could enhance treatments for neuroinflammation and oxidative stress-related disorders, offering a natural alternative to synthetic drugs. | Effective dosing varies widely, and there is limited evidence of efficacy in diverse populations or clinical settings. | [40] |

| LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro and scopolamine-induced male ICR mice in vivo | 1, 10, 50 or 50 μg/mL FCL incubated for 24 h in vitro and 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg FCL in vivo | ↓ NO production, ↓ PGE2 production, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↑ AP-1 inhibition, ↓ NF-κB activation, ↓ p-MAPKs, ↑ AChE inhibition (in vitro) and ↑ pCREB and BDNF expression (in vivo) | May offer new avenues for treating cognitive deficits and memory impairments associated with neurodegenerative conditions. | Discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo findings highlight a need for more consistent research methodologies. | [41] | |

|

Cannabis sativa (Cannabidiol, cannabigerol, cannabidiolic acid, tetrahydrocannabinol, β-caryophyllen, caryophyllene-oxide, α-Humulene and apigenin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 1 μg/mL CSE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β production, ↑ AEA and 2-AG expression, ↓ JNK and p38 activation, ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation, ↓ ROS production (in vitro) | Could be a cornerstone for novel treatments targeting neuroinflammation and chronic pain, with potential applications in psychiatric and neurological disorders. | Clinical evidence is sparse, and variability in cannabis strains and compounds makes standardization difficult. | [42] |

| Dioscorea nipponica (Dioscin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro and scopolamine-induced male C57BL mice in vivo | 10, 20, 50 or 100 μg/mL dioscin incubated for 24 h in vitro and 60 mg/kg dioscin in vivo | ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↓ NO and PGE2 production, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression, ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation, ↓ IκB phosphorylation, ↓ p65 nuclear translocation (in vitro) and ↑ BDNF and pCREB expression (in vivo) | May support treatments aimed at improving cognitive functions and mood disorders by targeting neuroinflammatory pathways. | More extensive studies are required to confirm efficacy, dosage safety, and long-term impacts. | [43] |

|

Centipeda minima (Chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, rutin, isochlorogenic acid A, isochlorogenic acid B, isochlorogenic acid C and 6-O-angeloylplenolin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro and LPS-stimulated male C57BL/6J mice in vivo | 2, 4 or 6 μg/mL ECM incubated for 24 h in vitro and 100, 200 mg/kg ECM in vivo | ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation, ↓ IκB phosphorylation, ↓ COX-2 and iNOS expression, ↓ NO and PGE2 production, ↓ NOX proteins (in vitro) and ↓ NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β production, ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation, ↓ iNOS, COX-2 and NOX2 and NOX4 expression (in vivo) | Potential to develop comprehensive anti-inflammatory therapies targeting multiple pathways involved in neuroinflammation. | Variability in phytochemical compositions can complicate standardization and reproducibility. | [44] |

|

Atractylodis Rhizoma Alba (Atractylenolide I, atractylenolide III, and atractylodin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 10, 50, or 100 μg/mL ARAE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO production, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↑ HO-1 mRNA expression, ↓ NF-κB activity, ↓ MAPK, p38, ERK and JNK activation (in vitro) | May contribute to integrative approaches for treating neuroinflammation and related conditions. | Lack of long-term studies and clinical trials limits understanding of potential side effects and interactions. | [45] |

|

Vaccinium bracteatum (Quercetin, chrysin, apigenin, kaempferol, and lutelin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 1, 2,5, 5, 10 or 20 µg/ml VBME incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO and PGE2 production, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↓ NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels, ↓ ROS production (in vitro) | May inspire new anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatments with fewer side effects. | Variability in results across different studies and cell models necessitates further investigation. | [46] |

|

Lonicera japonica (Chlorogenic acid,chlorogenic acid,caffeic acid,cryptochlorogenic acid,artichoke,isochlorogenic acid A,isochlorogenic acid B,isochlorogenic acid C,rutin,hibisin and loganin) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 0.5, 5, 2.5, 5 or 10 µg/mL LJ incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO and PGE2 production, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 mRNA expression, ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1 and MMP-9 production, ↓ ROS levels, ↓ p38 MAPKs, ERK 1/2, JNK and PI3K/Akt phosphorylation, ↓ JAK1/STAT1/3 phosphorylation, ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation (in vitro) | Could lead to new treatments targeting both neuroinflammation and related oxidative stress. | Complex composition requires more research to determine the most effective components and dosages. | [47] |

|

Bambusae caulis ( (-)-7'-epi-lyoniresinol 4,9'-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (7), (-)-lyoniresinol 4,9'-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (8) and bambulignan A) |

LPS-stimulatred BV-2 cells and glutamate-stimulated hippocampal HT22 cells in vitro | 10, 20, 40, 60 or 80 μg/ml BCE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 levels, ↓ iNOS and COX-2 expression, ↓ ROS production, ↑ HO-1 mRNA expression, ↑ Nrf2 nuclear translocation (in vitro) | Potential for advancing treatments against neuroinflammation and oxidative damage through modulation of key inflammatory and oxidative pathways. | Additional studies required to delineate specific active components and refine therapeutic protocols. | [48] |

| Zingiberis Rhizoma (Gingerols and shogaol) |

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells in vitro | 1, 5 or 10 μg/ml GHE incubated for 24 h in vitro | ↓ NO and PGE2 production, ↓ COX-2 mRNA expression, ↓ TNF-α and IL-1β production, ↓ MAPK molecules, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK phosphorylation, ↓ NF-κB nuclear translocation (in vitro) | Promising candidate for developing interventions targeting neuroinflammatory processes and related molecular pathways. | Further research is essential to optimize dosing strategies and elucidate mechanistic details. | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).