1. Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is predominantly diagnosed in women, accounting for approximately 75% of cases (Sanchious, 2024). This significant gender difference has been criticized from a feminist perspective, which argues that the diagnosis of BPD may be influenced by gender stereotypes that pathologize behaviors socially attributed to women, such as intense emotionality and instability in relationships (Dodd, 2015; Rheude, 2022) both in society and among diagnosing professionals. These characteristics, commonly associated with BPD, reinforce perceptions that women are "overly emotional" or "unstable", whereas similar traits in men are often interpreted differently or even normalized (Dodd, 2015; Oredsson, 2023).

Another key aspect of the BPD diagnosis that reinforces gender bias is the criterion related to inappropriate anger. This criterion is problematic not only due to its formulation, which offers little guidance to distinguish between "appropriate" and "inappropriate" anger, but also because its interpretation may depend on deeply rooted gender stereotypes—not only in those experiencing anger but also in professionals interpreting symptoms as "appropriate" or "inappropriate." Psychological research suggests that this criterion can be understood and applied in various ways, none of which are mandatory or exclusive. This ambiguity, combined with the working conditions in clinical settings, increases the risk of professionals relying on stereotypes to assess anger (Oredsson, 2023). Specifically, empirical studies on public administration and management point to the widespread influence of gender stereotypes, where anger is traditionally associated with men, while women expressing anger are often perceived as emotionally unstable or out of control (Oredsson, 2023). This reinforces gender bias in diagnoses like BPD, where anger may be interpreted differently depending on the person's gender in therapeutic processes.

Moreover, women who express anger are often seen as deviating from prescribed gender roles, and their anger is thus more frequently labeled as "inappropriate" (Oredsson, 2023). In psychiatry, this could result in women being diagnosed with BPD more frequently due to the tendency to interpret their anger as pathological. This systematic bias reinforces the pathologization of female emotion and the unequal interpretation of the same symptoms in men and women (Oredsson, 2023).

In the 1980s, feminist protests against the DSM highlighted how certain psychiatric diagnoses included in the manual were sexist and pathologized feminine behaviors reflecting broader social issues rather than individual disorders. Diagnoses like Masochistic Personality Disorder or Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder reflected a patriarchal perspective that ignored the effects of gender socialization on women's mental health. This critique remains central to the current debate on BPD, a diagnosis disproportionately applied to women and reinforcing gender stereotypes about excessive emotionality (Dodd, 2015). Feminists argued that many DSM diagnoses contribute to the pathologization of feminine behavior, presenting emotional problems as inherent to women's nature.

This is particularly evident in the interpretation of BPD symptoms, where traits like emotional instability or impulsivity are pathologized in women, while violent or aggressive male behaviors tend to be viewed as social or criminal issues rather than mental disorders. This approach underscores the need to review tools like the BSL-23, whose items on self-harm or impulsivity may perpetuate a gender-biased perspective that disproportionately pathologizes women (Dodd, 2015). Feminist critiques also emphasize how the DSM differently interprets male and female behaviors: while male violence may be seen as a "normal" response to stress, sadness or anger in women is frequently labeled as pathological. This highlights the importance of considering sociocultural influences on female behavior and questioning how scales like the BSL-23 may reinforce biased narratives around BPD (Dodd, 2015).

Finally, some feminists proposed alternative diagnoses that reflect the impact of male violence on women's mental health, such as Battered Woman Syndrome (Dodd, 2015). This proposal sheds light on how social problems and power dynamics influence mental health—an approach that can also be applied to BPD. Thus, BPD should not be considered solely an individual problem but a reflection of socialization and patriarchal structures that affect women in our society (Dodd, 2015).

In the psychiatric literature, a broad analysis of the symptoms of BPD has been carried out, highlighting the importance of grouping the symptoms into key dimensions that facilitate the clinical understanding and treatment of this disorder, as we as professionals are currently faced with a wide spectrum of symptoms. In the work of Clarkin et al. (2007), the symptoms of BPD are grouped into three major dimensions: affective dysregulation, interpersonal difficulties and impulsivity, which constitute the core of the disorder. However, from a feminist perspective, it is essential to question how these symptoms may have been pathologized differently in women, fueling gender stereotypes and perpetuating a biased view of female mental health.

Difficulties in emotional regulation are a central feature of individuals with BPD. These difficulties are associated with temperaments such as high neuroticism and low extraversion, both commonly observed in patients with this disorder. The inability to adequately manage negative emotions may lead to increased impulsivity and self-destructive behaviors. This finding is particularly relevant when considering how gender stereotypes and covert social victimization can exacerbate these emotional difficulties in women and others socialized under restrictive gender expectations. Socialization based on emotional control and submission may heighten emotional reactivity, reinforcing patterns of affective instability associated with BPD (Peláez, 2024).

Additionally, it has been found that individuals with BPD exhibit a reduced attentional bias towards positive stimuli, meaning they tend to focus less on stimuli that could generate positive emotional responses. This reduction in positive attentional bias is closely related to difficulties in regulating emotions, a central aspect of BPD. The lack of attention to positive stimuli can worsen emotional instability, as individuals with BPD do not benefit from stimuli that, in others, would help stabilize their emotional state. This mechanism is further affected in contexts of covert social victimization and gender stereotypes, where individuals with BPD, especially women, are exposed to environments that reinforce emotional negativity and increase negative emotional reactivity (Wenk, 2024).

In recent years, various data suggest that women experience specific health problems that may stem from structural inequalities between men and women (Homan, 2019; Lorente Acosta, 2007; Vives-Cases et al., 2007). Studies in the health field have identified a link between the internalization of certain gender stereotypes and poorer health outcomes for women (Anastasiadou, et. al, 2013; Aparicio-García et. al, 2018; Aparicio-García et. al, 2019; Casado et. al, 2018). Covert social violence has been identified as a form of victimization with widespread impact, affecting both psychological health and women's perceptions of their societal roles (Ellsberg et al., 2015; Temmerman, 2015). Despite its relevance, academic research highlights a lack of attention to these forms of violence in traditional studies, hindering prevention and visibility efforts. This article seeks to connect this perspective with BPD diagnosis, exploring how these experiences of covert violence impact symptom severity and emphasizing the need to address the influence of patriarchal structures on mental health.

Adopting a mixed-methods approach, this study incorporates a qualitative perspective to delve deeply into the experiences and perceptions of women diagnosed with BPD, positioning them as active subjects in knowledge construction. This approach aims to transcend the limits of traditional academia, bringing research closer to the real experiences of those facing these issues in their lives. From a feminist perspective, it is crucial to give voice to affected women, not merely as passive participants in a study but as protagonists who can contribute a richer and more complex understanding of how gender structures and covert violence impact their mental health. This work seeks to rescue these narratives and make their experiences visible, contributing to more inclusive science.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participant sample consisted of a total of 99 individuals. The mean age was 29.64 years (SD = 7.96) with a median age of 28 years (MAD = 7.41). Most participants were cisgender women (88.89%), single (31.31%), heterosexual (30.1%), had completed secondary education (48.48%), employed (33.33%), reported a financial situation as comfortable (52.23%), and two additional disorders (43.43%). Further details are available in

Table 1.

2.2. Measures

Sociodemographic measures. Participants answered a set of questions regarding age, gender, perception of being considered a racialized person, nationality, civil status, educational level achieved, employment status, economic status, sexual orientation, and the number of additional psychological disorders (besides BPD).

Borderline Symptom List-23. This instrument was developed to assess the severity of BPD (Bohus et al., 2009). For this study, the brief Spanish validation was employed (Soler et al., 2013). This psychometric tool comprises 23 items (e.g., “The criticism had a devastating effect on me”). Items are scored on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all; 4 = Very strong). The latent structure is composed of a single factor. The Spanish validation reported excellent reliability (α = .94). In the present study, similar internal consistency was found (α = .94; ω = .96).

Inventory of Covert Social Violence Against Women (IVISEM). This scale was used to measure different dimensions of gender mandates that women assume as something normalized and that, in some way, subject them to the male figure, resulting in a form of socially accepted victimization. The questionnaire was developed originally in Spanish by Vinagre-González et al. (2020). It comprises 35 items comprising seven subscales and one second-order factor. The subscales are as follows: Maternity (e.g., Mothers have a special bond with their children that fathers do not have), Romantic love and partner (e.g., The ideal is to find a partner to be happy with forever), Care (e.g., When children need to be taken to the doctor, mothers understand and follow the instructions better than fathers), Career projection (e.g., If a choice must be made between the woman and the man to care for the children, it is more convenient for the woman to give up part of her professional life), Attitudes and submission (e.g., Men are usually the ones who make important financial decisions), Biology and abilities (e.g., In general, women have worse spatial abilities. For example, they are worse at reading maps), Neosexism (e.g., In reality, feminists only seek equality, not the superiority of women over men). The validation reported a good fit for the heptafactorial model and excellent internal consistency for the general factor (α = .93; ω = .95). In the present study, internal consistency ranged from acceptable to excellent across subscales: Maternity (α = .59; ω = .70); Romantic love and partner (α = .85; ω = .90); Care (α = .82; ω = .88); Career projection (α = .75; ω = .87); Attitudes and submission (α = .83; ω = .89); Biology and abilities (α = .76; ω = .86); Neosexism (α = .88; ω = .92). Finally, the general scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = .94; ω = .96).

Experiences with Gender, stigma, and diagnosis survey. Participants completed a custom-designed survey to assess their experiences related to the intersection of gender, stigma, and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). The survey included items that explore perceived misinterpretation of symptoms based on gender, experiences of stigma and discrimination, gender-based modifications in treatment, exposure to violence (e.g., physical and sexual abuse), social pressures related to traditional gender roles, and the impact of the BPD diagnosis on their emotional well-being and personal achievements.

Qualitative measures. To explore participants subjective experiences with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and the influence of gender stereotypes, an open-ended questionnaire was designed. The qualitative section aimed to gather in-depth insights into the following themes: Diagnostic Journey: participants were asked about their experiences with the diagnosis of BPD, including who provided the diagnosis, how their symptoms were interpreted, and whether these interpretations were influenced by gender. Stigma and Discrimination: questions explored experiences of stigma, such as being blamed for emotional difficulties due to gender stereotypes, and instances of discrimination related to their diagnosis or gender. Trauma and Gender Expectations: participants were asked about their history of trauma and whether societal expectations of gender roles impacted their emotional well-being and interpersonal relationships. Emotional Intensity and Gender Bias: participants reflected on how gender stereotypes influenced the interpretation and management of intense emotions or anger by mental health professionals. Violence and Structural Norms: questions addressed the role of societal norms in shaping participants' interpersonal and emotional experiences, as well as their interactions in medical and therapeutic contexts. An example question was: "Do you think gender stereotypes have influenced how your intense emotions or episodes of anger are interpreted?"

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Data analysis of quantitative research

First, to describe the sample, frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical sociodemographic variables, as well as the mean, median, standard deviation and median absolute deviation were computed for age. Second, to describe the sample’s questionnaire scores, several estimates were calculated. Specifically, mean, standard deviation, median, median absolute deviation, minimum, maximum, skewness and kurtosis were computed for all items on the BSL and IVISEM scales, as well as for the total score of the BSL scale and the scores of all IVISEM subscales.

Third, internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω for each dimension of the BSL and IVISEM scales. Given the ordinal nature of the items (i.e., Likert-type scales), polychoric correlation matrices were employed to compute these reliability coefficients, as they are more appropriate than Pearson correlation matrices for ordinal data (Kiwanuka et al., 2022).

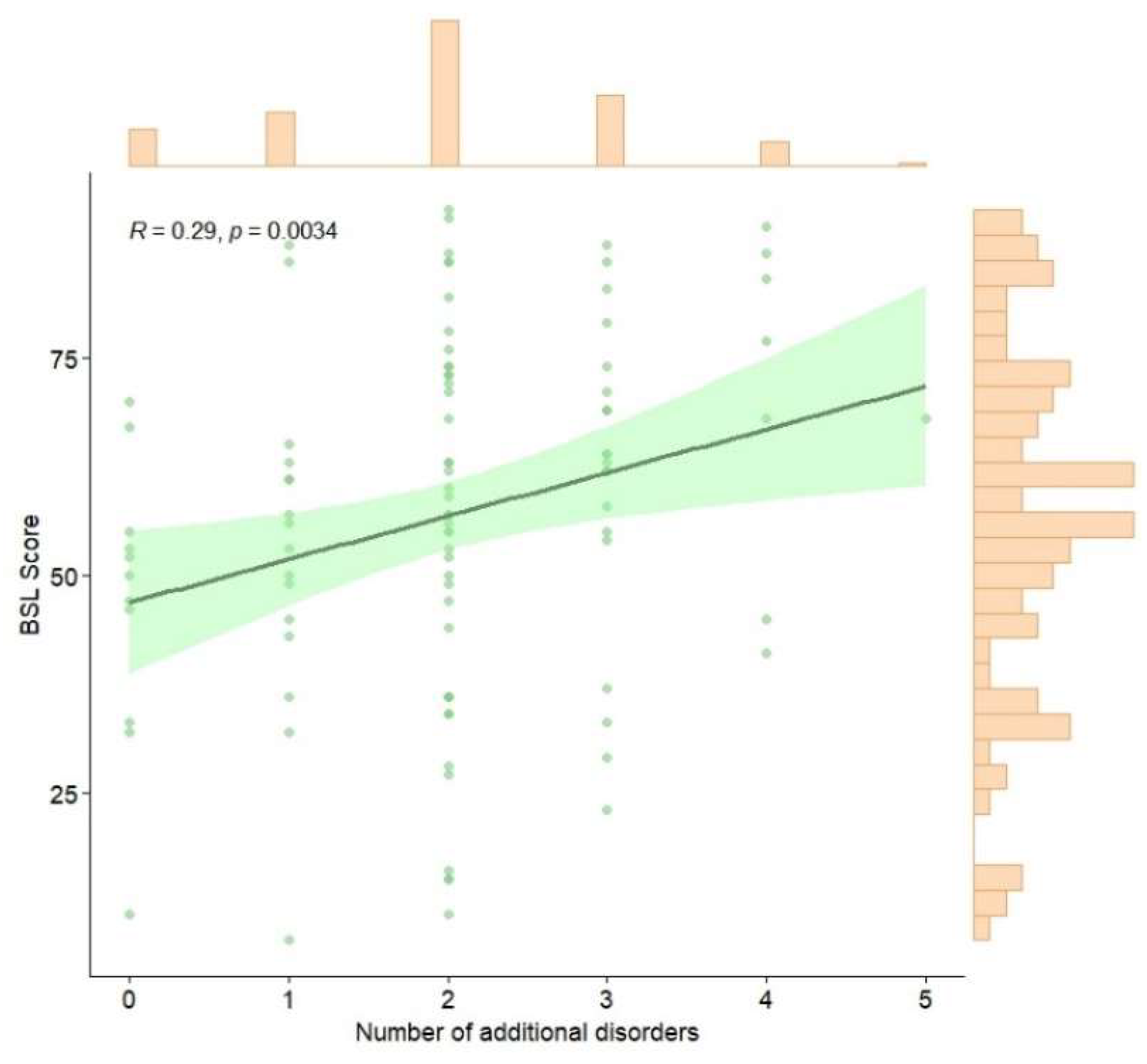

Fourth, the association between the total score on the BSL and the number of self-reported disorders (excluding BPD) was explored using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, given the non-normal distribution of the variables (De Winter et al., 2016).

2.4.2. Data analysis of qualitative data

The qualitative data collected through open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis guidelines. The process began with a thorough review of the responses to familiarize researchers with the content, followed by systematic coding using NVivo 15 software to identify key ideas and patterns relevant to the study's objectives. Codes were then grouped into broader themes, such as 'Stigmatization and Structural Violence,' 'Emotional Intensity and Gender Expectations,' 'Guilt and Gender Roles,' 'Impact of Diagnosis on Identity,' 'Intersections between Violence and Gender,' and 'Perceptions of Therapeutic Relationships'. Which were reviewed and refined to ensure consistency and coherence. Final themes were defined and supported by excerpts from participants responses, and the qualitative findings were integrated with the quantitative results to provide a comprehensive understanding of the role of gender stereotypes and covert social violence in shaping participants’ experiences.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative research

The descriptive statistics for the items from the BSL scale, along with the total score, are presented in

Table 2. For Item 13 (“I suffered from shame”), the mean score is 2.69 (SD = 1.31). Item 17 (“I felt vulnerable”) shows a higher mean score of 3.14 (SD = 1.08). For Item 23 (“I felt worthless”), the mean score is 2.63 (SD = 1.50). The total score on the BSL scale has a mean of 56.81 (SD = 20.31), with scores ranging from 8 to 92.

The descriptive statistics for selected items from the IVISEM scale are presented below in

Table 3. Item 10 (“A woman takes better care of children and the elderly because she has a greater capacity for self-denial and sacrifice”) has a mean of 2.29 (SD = 1.48). Item 13 (“Women have more anxiety problems due to hormonal changes”) shows a higher mean (M = 3.05, SD = 1.38). Item 19 (“Women are usually more submissive than men”) has a mean of 2.23 (SD = 1.43). Item 26 (“It is normal for a girl to command more respect than a boy and to show more prudence in sexual behavior”) presents a mean of 2.67 (SD = 1.44). Item 33 (“It is more important for a woman to show prudence than for a man”) shows the lowest mean, at 1.72 (SD = 1.16). Lastly, Item 34 (“Women are more sensitive than men”) has a mean of 2.74 (SD = 1.49).

The IVISEM scale comprises several subscales, each designed to assess a distinct dimension. The Maternity subscale has a mean score of 13.32 (SD = 3.97). For the Romantic Love and Partner subscale, the mean is 11.14 (SD = 4.40). The Care subscale shows a mean score of 11.69 (SD = 5.01). The Career Projection subscale has a mean of 10.33 (SD = 4.15). The Submission Attitudes subscale presents a mean of 11.17 (SD = 4.81). The Biology and Abilities subscale has a mean score of 13.36 (SD = 4.70). The Neosexism subscale shows a lower mean score of 8.53 (SD = 4.48), with a range of 5 to 22. Finally, the Total Score across all subscales has a mean of 79.55 (SD = 23.68), with scores ranging from 41 to 142.

Among the subscales, Biology and Abilities and Maternity subscales show the highest mean scores. In contrast, the Neosexism subscale has the lowest mean score.

As figure 1 shows, the Spearman correlation coefficient between the total score on the BSL scale and the number of self-reported disorders is .29, indicating a significant and positive relationship (p < .0034).

Additional data collected through the Experiences with Gender, Stigma, and Diagnosis Survey provided further insights into participants experiences with BPD and its intersection with gender. A total of 72.7% of participants reported receiving a BPD diagnosis between 2019 and 2024, with 60.8% stating that their symptoms had been misinterpreted due to gender. Additionally, 24.3% experienced gender-based changes or adjustments in their treatment, and 57.1% reported stigma-related experiences. Gender-specific blame for emotionality was reported by 62.2% of participants.

Regarding experiences of violence and social pressure, 64.6% reported physical abuse by a partner or family member, 64.6% experienced sexual abuse, and 59.6% reported intimate partner violence or domestic violence. Furthermore, 84.8% reported experiencing pressure to conform to beauty standards, while 74.7% highlighted societal pressure to adhere to traditional gender expectations.

In therapeutic contexts, 44.9% of participants reported differences in treatment based on gender. Additionally, 61.6% indicated that their BPD diagnosis had been used to invalidate their experiences, 51.5% felt it was used to minimize their achievements or decisions, and 62.9% noted stereotypes in the interpretation of intense emotions or anger. Lastly, 27.6% encountered professionals with gender-based biases.

3.1. Qualitative research

The qualitative analysis identified key thematic categories derived from participants responses, which are presented in

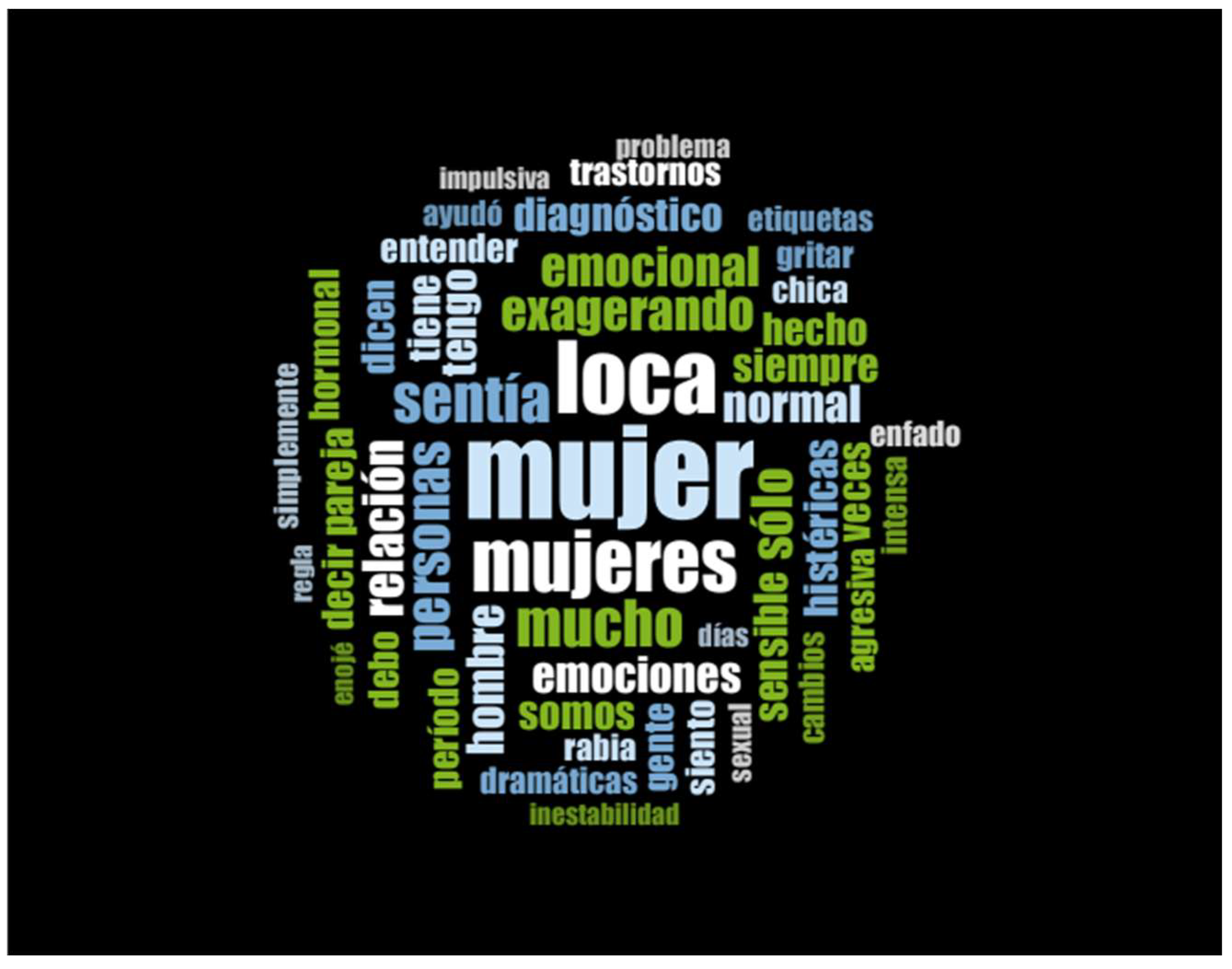

Table 4. These categories were constructed based on the most frequent keywords and their respective counts and weighted percentages. The results provide a detailed representation of the linguistic patterns and thematic structures captured in the data, highlighting the centrality of gendered experiences, emotional expression, and diagnostic processes in the participants' narratives. The table offers a systematic summary of these findings, organized by thematic category and supported by the frequency and proportion of key terms identified in the analysis. A visual representation of the most frequently used keywords identified in the qualitative analysis is provided in

Appendix Figure A1, illustrating the prominence of terms related to gender, emotions, and diagnostic experiences.

The qualitative analysis identified key thematic patterns reflecting participants' experiences with BPD and its intersections with gender norms and societal expectations.

Symptoms and experiences associated with BPD.

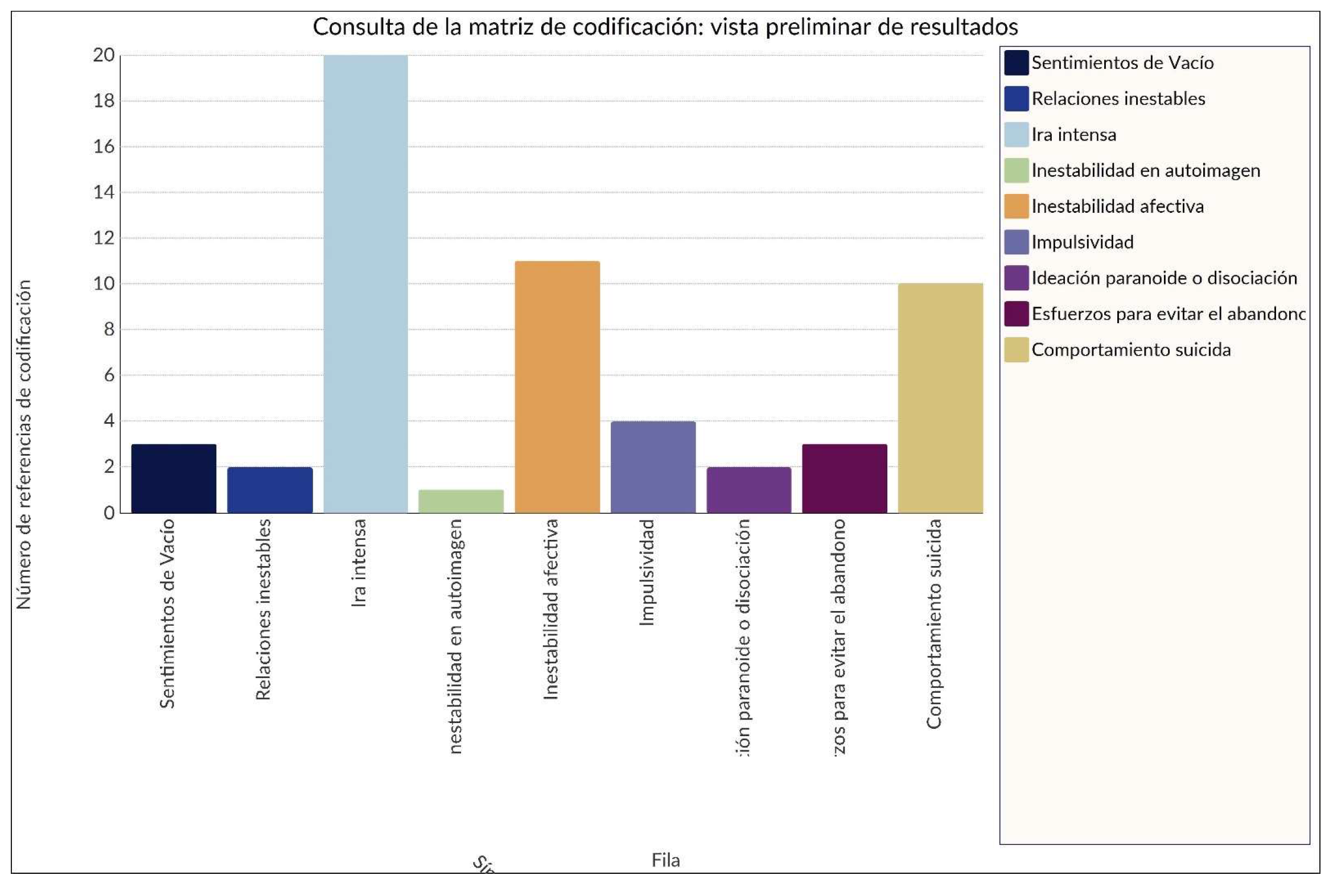

Figure A2 presents the coding distribution of primary BPD symptoms. Intense anger (19 references) and suicidal behavior (12 references) emerged as the most frequently coded symptoms, followed by emotional instability and impulsivity. These results highlight the centrality of emotional dysregulation and self-harm in participants’ narratives.

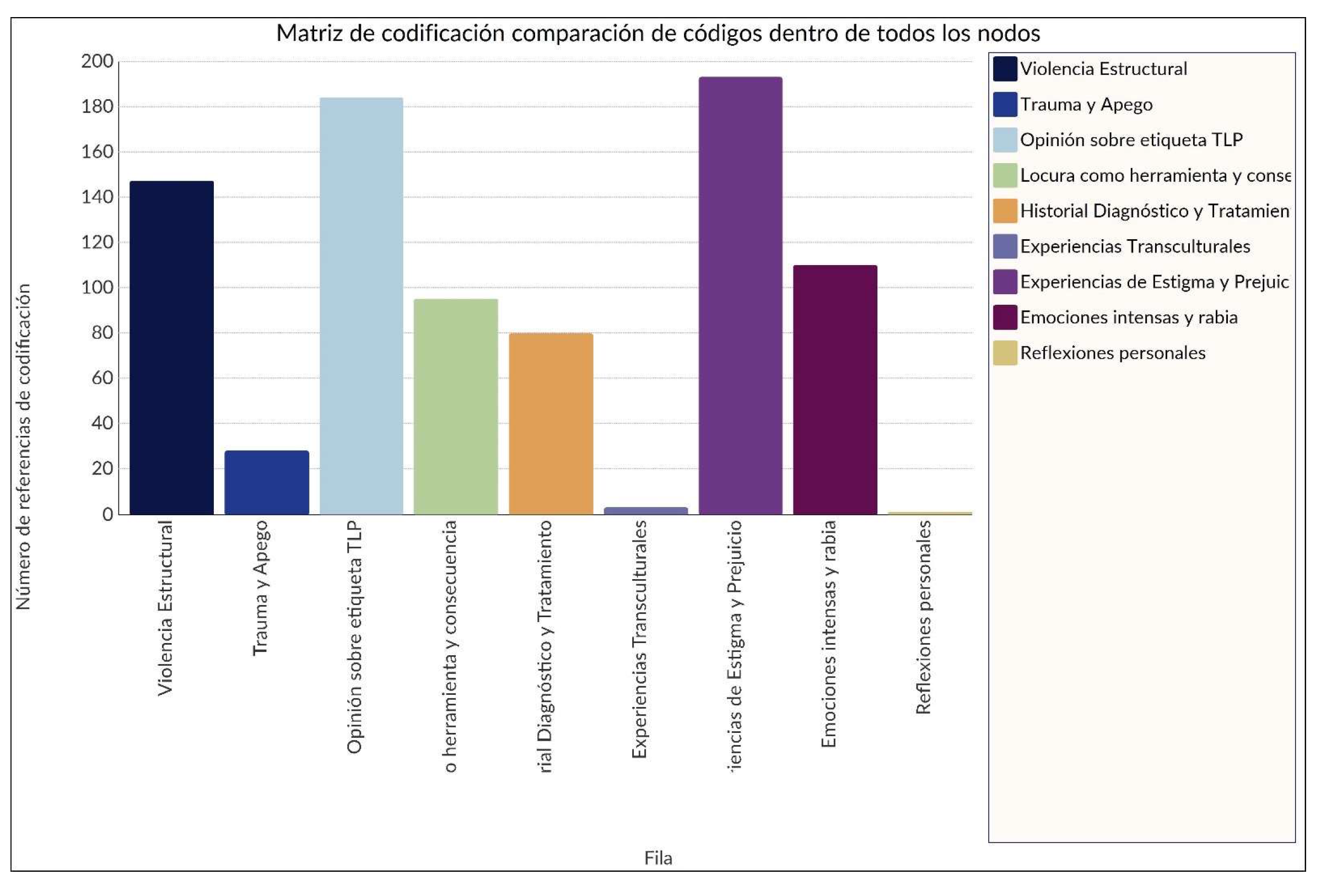

General thematic categories. The distribution of references across general thematic categories is shown in

Figure A3. Experiences of stigma and prejudice (192 references), Opinions on the BPD label (181 references), and Structural violence (145 references) were the most prominent themes, underscoring the pervasive influence of societal and systemic factors in shaping participants' experiences.

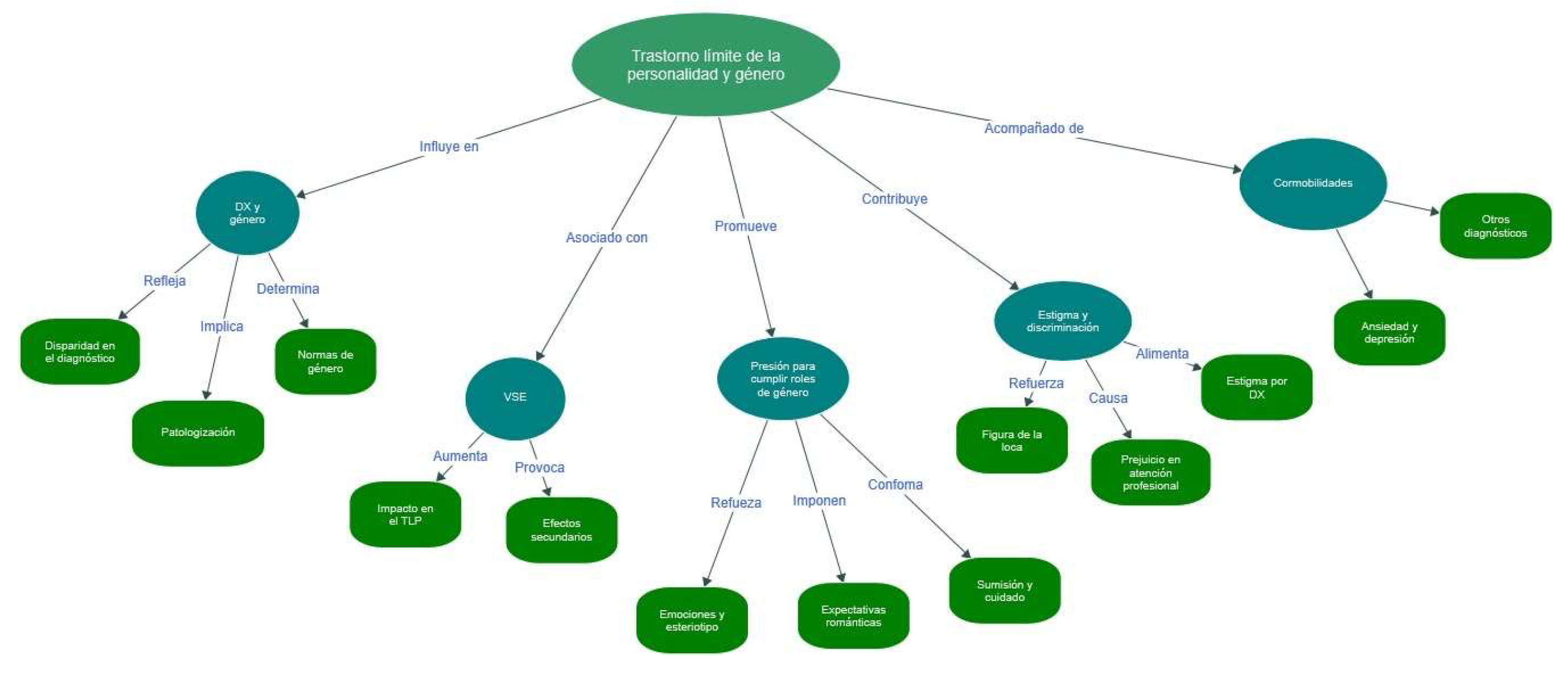

Gender and BPD relationships.

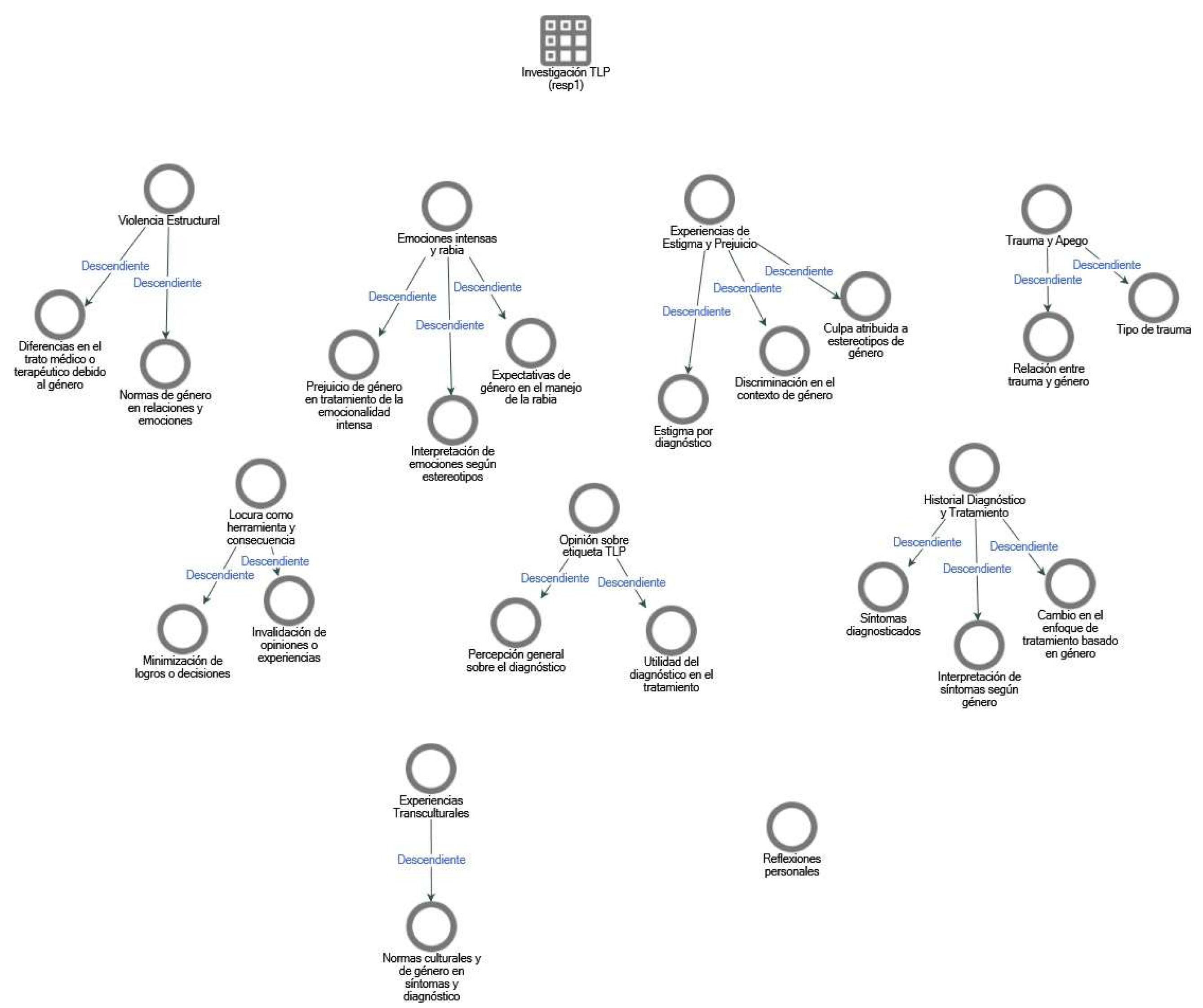

Figure A4 and

Figure A5 illustrate the conceptual relationships between gender norms and BPD experiences. Participants frequently reported instances of pathologization and invalidation tied to gendered stereotypes, with the construct of the “crazy woman” emerging as a recurrent theme. These visualizations provide insight into how gender expectations influence both the interpretation of symptoms and therapeutic approaches.

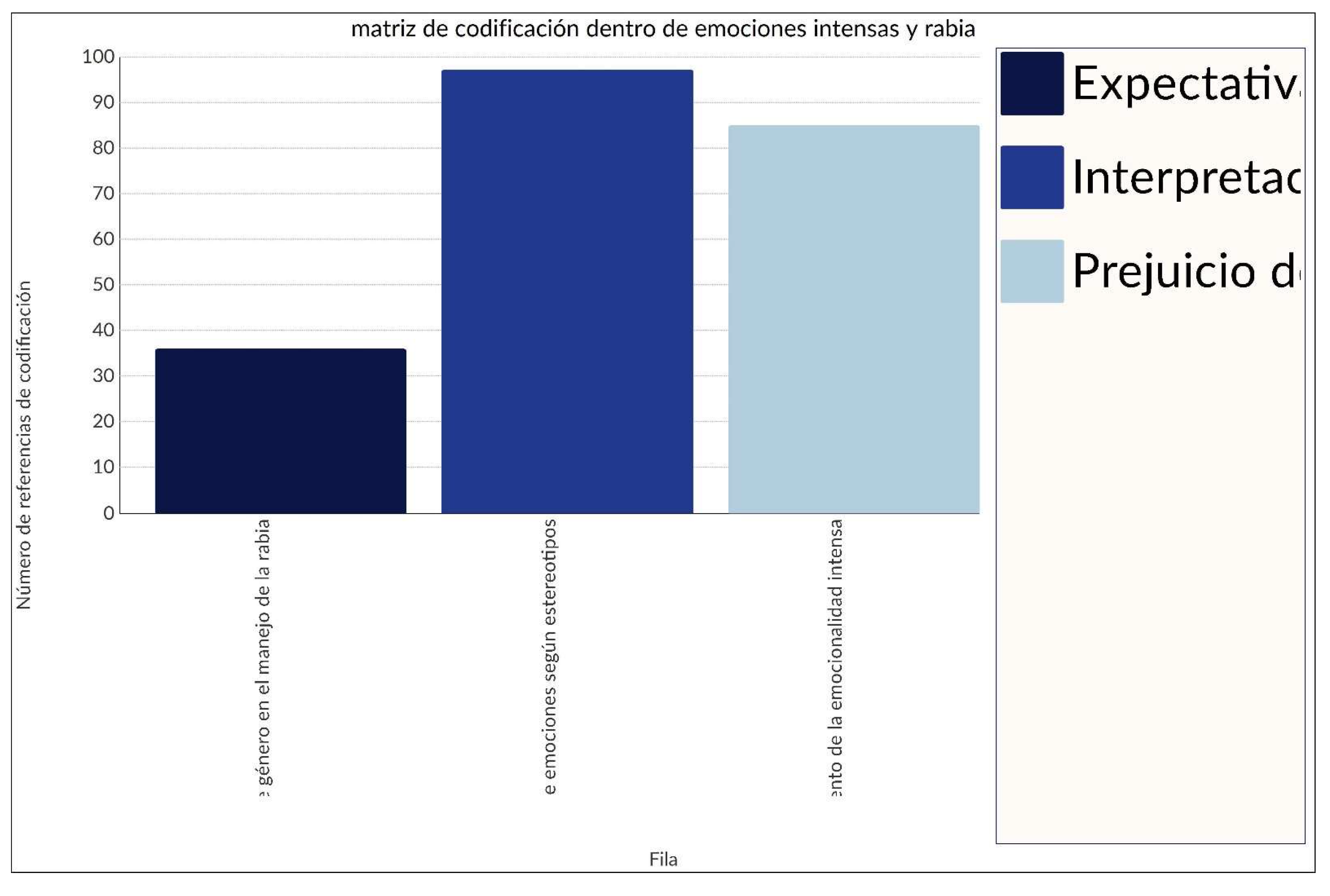

Intense emotions and anger.

Figure A6 focuses on coding related to intense emotions and anger. Subthemes included interpretation of emotions through stereotypes (98 references), gender bias in managing emotionality (90 references), and expectations of gender in anger management (40 references). These results suggest a gendered lens in clinical settings that disproportionately pathologizes emotional intensity in women.

4. Discussion

The descriptive results from the BSL-23 show that items related to intense emotions, such as shame and vulnerability, have high scores, indicating a high emotional intensity in the participants. The total mean suggests moderate severity of BPD symptoms, but with significant variability in the expression of these symptoms, highlighting the importance of personalized therapeutic approaches that address both intense emotions and self-esteem, beyond the labels. This finding aligns with the critique presented by Dodd (2015), who emphasizes how intense emotions, commonly associated with women, are pathologized within the BPD diagnosis.

Although the results do not allow for a firm conclusion due to the sample size, there is a preliminary correlation between higher scores on the BSL-23 and the presence of comorbidities such as anxiety and depression. This suggests that social and structural factors could play a role in exacerbating mental disorders, as reflected in the BSL-23 scores, where higher severity levels are associated with greater psychological distress and functional impairment. This correlation aligns with the observations of Vives-Cases et al. (2007), who highlighted how internalizing gender stereotypes can contribute to worse health outcomes for women.

In the IVISEM scale, items related to motherhood and biological abilities show high scores, suggesting that participants internalize traditional gender expectations. In contrast, items related to neosexism show lower scores, indicating a general rejection of more modern ideas about gender inequality. These findings underline how gender stereotypes impact the emotional and psychological experience of participants, especially regarding the BPD diagnosis, supporting the idea that gender stereotypes contribute to the pathological interpretation of emotions in women diagnosed with BPD (Dodd, 2015).

Qualitative data show that participants experience a pathologization of their identity through gender stereotypes, especially the label of "crazy" or "hysterical." The intense emotionality of women is frequently misinterpreted and seen as a symptom of BPD due to gender stereotypes. This finding reinforces the idea that women are more likely to be diagnosed with BPD when their emotions are seen as overwhelming or uncontrollable, as pointed out in previous works (Dodd, 2015).

A high percentage of participants reported experiencing physical and sexual violence, as well as social pressure to conform to beauty standards and traditional gender expectations. These social and structural factors are crucial, as they contribute to the exacerbation of BPD symptoms and should be considered in therapeutic interventions. Covert social violence has been identified as a factor of victimization with significant impact on mental health, particularly for women (Ellsberg et al., 2015).

In therapeutic contexts, participants reported differences in treatment based on gender, with frequent invalidations of their experiences due to their BPD diagnosis. This underscores the importance of a balanced and gender-sensitive approach in treatment to avoid biases and ensure that women’s experiences are considered fairly, without invalidation or minimization of their achievements through socially constructed labels like "crazy," "intense," or "hysterical." This finding supports feminist critiques of how the BPD diagnosis can be used to delegate responsibility for emotions to women, contributing to the pathologization of their emotional experiences (Dodd, 2015).

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size of 99 participants limits the statistical power of the analysis, which could affect the ability to generalize the results to a broader population that would not occur with a larger sample. Furthermore, the non-random sampling method (incidental sampling) introduces a selection bias, which limits the representativeness of the sample and therefore the generalizability of the findings. Another aspect to consider in qualitative information is that we are working with self-reported human experiences, which may be subject to memory or social desirability biases, particularly in the context of experiences of violence and stigmatization. Lastly, although a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches was included, qualitative data is subjective and may not reflect the totality of the experiences of participants and of people with BPD, the questions may not have been appropriate for the main objective of the study. Future studies could address the limitations mentioned above by increasing the sample size and using random sampling methods to improve the representativeness of the sample and the external validity of the results. In addition, it would be useful to include a more diverse sample, mainly in terms of gender, since this would allow us to draw relevant conclusions regarding how gender affects the experience of people with BPD as well as other demographic characteristics, in order to explore how gender experiences and BPD vary in different social and cultural contexts.

It is also recommended to continue using mixed methods, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the subjective experiences of individuals diagnosed with BPD. In particular, future research should delve deeper into the impact of covert social violence and how gender stereotypes continue to influence the diagnoses and treatments of BPD.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown how Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) symptoms, measured with the BSL-23, and experiences related to covert social violence (measured through the IVISEM scale) are intrinsically connected to the emotional experiences of the participants. The results of the BSL-23 showed high scores on items related to intense emotions such as shame and vulnerability, suggesting that participants experience significant emotional responses, particularly in relation to BPD symptoms. This emotional intensity reflects not only the symptoms of BPD but also the repercussions of the structural violence that women are exposed to, such as covert social violence. Additionally, terms such as "hormonal," "period," or "menstruation" appeared in the responses of the participants, which return to the biological paradigm of explaining female emotionality. This interpretation of women's emotionality from the biology of emotionality "that I'm dramatic, that I'm on my period, that someone hasn't given me good sex to be like this" reinforces the idea that their "intense" emotional reactions are considered something natural, related to their biology, instead of also looking for answers to the social and structural conditions that women face.

The results of this study highlight the need for psychological approaches that not only address the symptoms of BPD, but also the effects of covert social violence and structural violence on women's emotional health, in order to observe the consequences on women of these, in order to achieve a more effective intervention that does not retraumatize them and accompanies them. The high scores on the BSL-23 and the IVISEM suggest that interventions should consider both the intense emotions associated with BPD and the social factors that contribute to women’s emotional experiences. Interventions should understand these intense emotional responses within the context of social pressures and structural violence, avoiding the pathologization of these emotions as an individual disorder.

An important limitation in this study is the lack of male representation, particularly cis men, which prevents gender comparisons and highlights how BPD is still considered a predominantly female disorder. The absence of cis men in the sample suggests that BPD is a disorder "for and by" women. The lack of gender diversity in the sample highlights the need to rethink diagnostic tools and psychological interventions. Where are the men with BPD? Are they being diagnosed appropriately? Do all the women who have responded have BPD? What is happening with the professionals who are diagnosing? Why have more than 70% of the diagnoses been in the last 6 years?

The qualitative results of the study highlight the experience of women, outside the framework of a questionnaire designed by professionals. They speak of how women diagnosed with BPD experience the pathologization of their identity through gender stereotypes, particularly with regard to their emotionality. Terms like "crazy" and "intense" were repeatedly mentioned in the qualitative responses, reflecting how women's intense emotions are misinterpreted as pathological symptoms of BPD. The frequent invalidation of their emotions and viewing these as out of control highlights how gender stereotypes, such as that of the emotionally overwhelmed woman, contribute to the stigmatization of women's emotional experiences.

Qualitative data also underscore the impact of structural violence on women diagnosed with BPD. Many participants reported having been victims of physical and sexual violence, reinforcing the idea that BPD should not be seen solely as an individual disorder, but as a condition influenced by social and structural factors. The social pressure to conform to beauty standards and traditional gender roles were also recurring themes, suggesting that these external factors contribute to the exacerbation of BPD symptoms.

It is crucial to conduct a feminist critique of the BSL-23 items, particularly those measuring impulsivity, self-harm, and intense emotions. The way these items are formulated and evaluated could perpetuate the pathologization of female emotionality without adequately considering the social and structural context influencing these responses.

BPD symptoms, especially those associated with overwhelming emotion, should be reevaluated in light of gender pressures and the social expectations imposed on women, rather than being interpreted merely as signs of emotional dysfunction.

Given that the results of this sample reflect significant exposure to structural and social violence, there is a need to rethink clinical practice and the "diagnostic culture." Instead of continuing the stigmatization through labels like "disease" or "pathology," we should consider discussing these life conditions in terms that acknowledge their roots in experiences of violence and oppression, moving away from stigma and addressing mental health from a more inclusive and comprehensive perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.. and E.V.; methodology, V.C., A.P., and E.V..; software, V.C., A.P. and E.V.; validation, E.V., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, V.C., E.V., .; investigation, E.V., M.A..; resources, E.V..; data curation, V.C. and E.V..; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, E.V..; visualization, E.V..; supervision, M.A..; project administration, M.A. and E.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Instagram accounts of individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) who have altruistically supported the dissemination of this study. Their collaboration has been essential in reaching a larger sample of participants and enhancing the inclusive approach of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Figure A1.

Word cloud of most frequent keywords

Figure A1.

Word cloud of most frequent keywords

Figure A2.

Coding matrix view of results of self-reported symptoms by participants

Figure A2.

Coding matrix view of results of self-reported symptoms by participants

Figure A3.

Coding matrix comparison of codes within nodes

Figure A3.

Coding matrix comparison of codes within nodes

Figure A4.

Concept map through the results obtained

Figure A4.

Concept map through the results obtained

Figure A5.

Nodes and subnodes

Figure A5.

Nodes and subnodes

Figure A6.

Coding matrix for "Intense emotions and anger"

Figure A6.

Coding matrix for "Intense emotions and anger"

References

- Acosta, L. Violencia de género, educación y socialización: Acciones y reacciones [Gender violence, education and socialization: Actions and reactions. Revista de Educación 2007, 342, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadou, D.; Aparicio, M.; Sepúlveda, A.R.; Sánchez-Beleña, F. Conformidad con roles femeninos y conductas alimentarias inadecuadas en estudiantes de danza [Conformity to the feminine norms and inadequate eating behaviors in female dance students]. Revista de psicopatología y psicología clínica 2014, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, Marta E. , Fernández-Castilla, B., Giménez-Páez, M. A., Piris-Cava, E., & Fernández-Quijano, I. Influence of feminine gender norms in symptoms of anxiety in the Spanish context. Ansiedad y Estrés 2018, 24, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García Marta, E.v.e.l.i.a.; Alvarado-Izquierdo, J.M. Is there a “conformity to feminine norms” construct? A bifactor analysis of two short versions of conformity to feminine norms inventory. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.) 2019, 38, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohus, M.; Kleindienst, N.; Limberger, M.F.; Stieglitz, R.-D.; Domsalla, M.; Chapman, A.L.; Steil, R.; Philipsen, A.; Wolf, M. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology 2009, 42, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado Mejía, R. , & García-Carpintero Muñoz, M. A. (2018). Género y Salud.

- Clarkin, J.F.; Levy, K.N.; Lenzenweger, M.F.; Kernberg, O.F. F. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2007, 164, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J. “The name game”: Feminist protests of the DSM and diagnostic labels in the 1980s. History of Psychology 2015, 18, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellsberg, M.; Arango, D.J.; Morton, M.; Gennari, F.; Kiplesund, S.; Contreras, M.; Watts, C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? The Lancet 2015, 385, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, P. Structural sexism and health in the United States: A new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. American Sociological Review 2019, 84, 486–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, F.; Kopra, J.; Sak-Dankosky, N.; Nanyonga, R.C.; Kvist, T. Polychoric correlation with ordinal data in nursing research. Nursing Research 2022, 71, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oredsson, A.F. Women ‘out of order’: inappropriate anger and gender bias in the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychosocial Studies 2023, 16, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, T.; López-Carrilero, R.; Espinosa, V.; Balsells, S.; Ochoa, S.; Osma, J. Efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of comorbid emotional disorders in patients with ultra high risk for psychosis: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, 367, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheude, C.; Nikendei, C.; Stopyra, M.A.; Bendszus, M.; Krämer, B.; Gruber, O.; Friederich, H.-C.; Simon, J.J. J. Two sides of the same coin? What neural processing of emotion and rewards can tell us about complex post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 2025, 368, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchious, S.N.; Zimmerman, M.; Khoo, S. Recognizing borderline personality disorder in men: Gender differences in BPD symptom presentation. Journal of Personality Disorders 2024, 38, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmerman, M. Research priorities to address violence against women and girls. The Lancet 2015, 385, e38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vives-Cases, C.; Alvarez-Dardet, C.; Carrasco-Portiño, M.; Torrubiano-Domínguez, J. ; Torrubiano-Domínguez, J. Gaceta sanitaria 2007, 21, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, T.; Günther, A.-C.; Webelhorst, C.; Kersting, A.; Bodenschatz, C.M.; Suslow, T. Reduced positive attentional bias in patients with borderline personality disorder compared with non-patients: results from a free-viewing eye-tracking study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 2024, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.; Gosling, J.C.; Potter, S.D. D. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychological methods 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).