Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

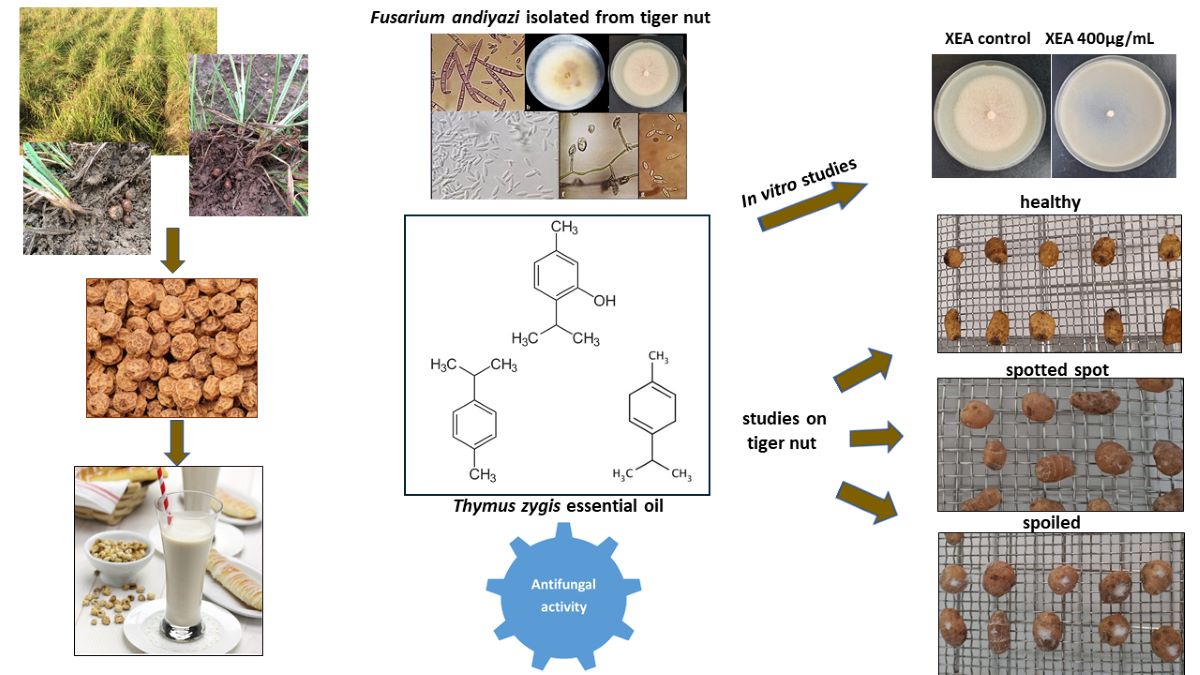

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Composition of the Thymus zygis EO

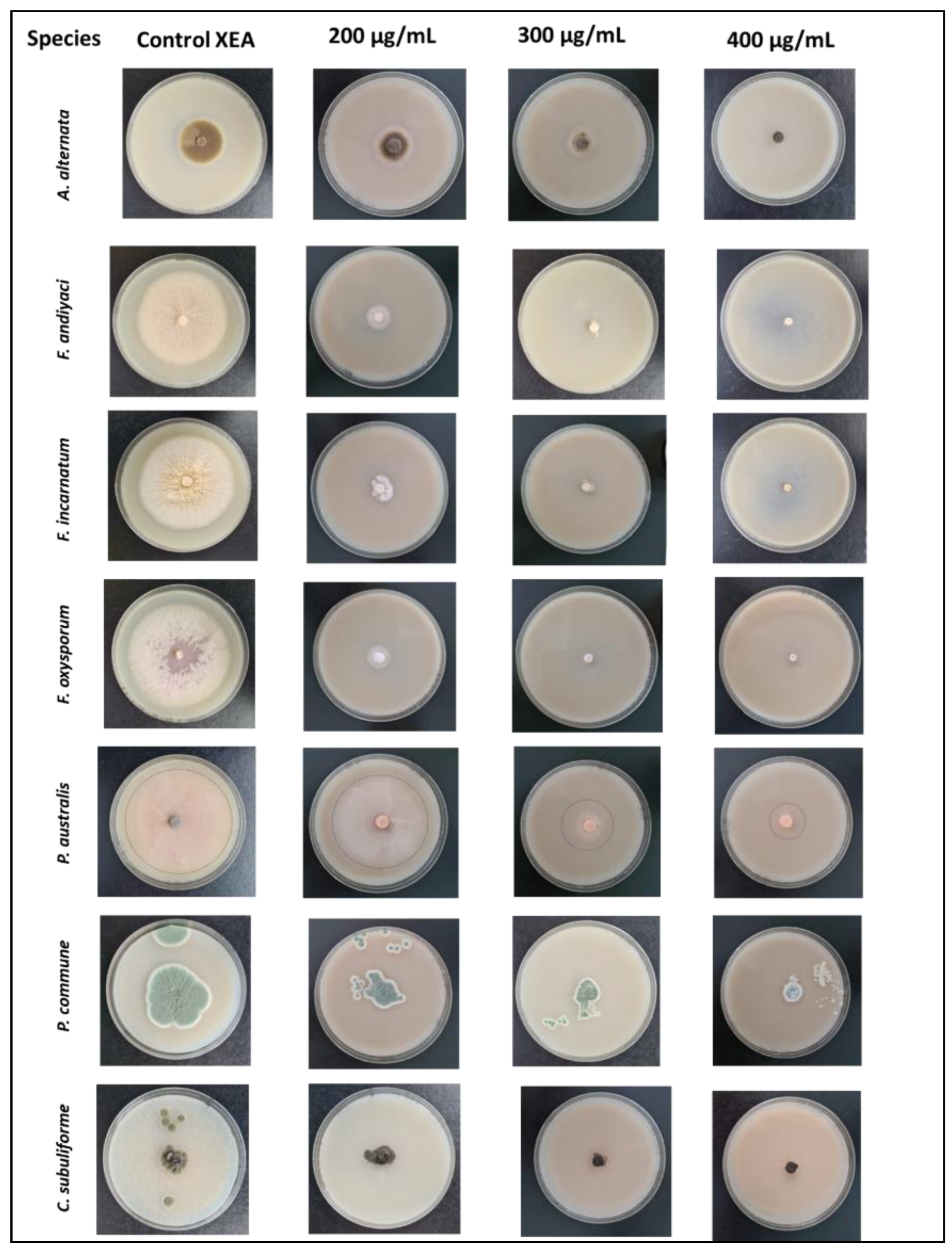

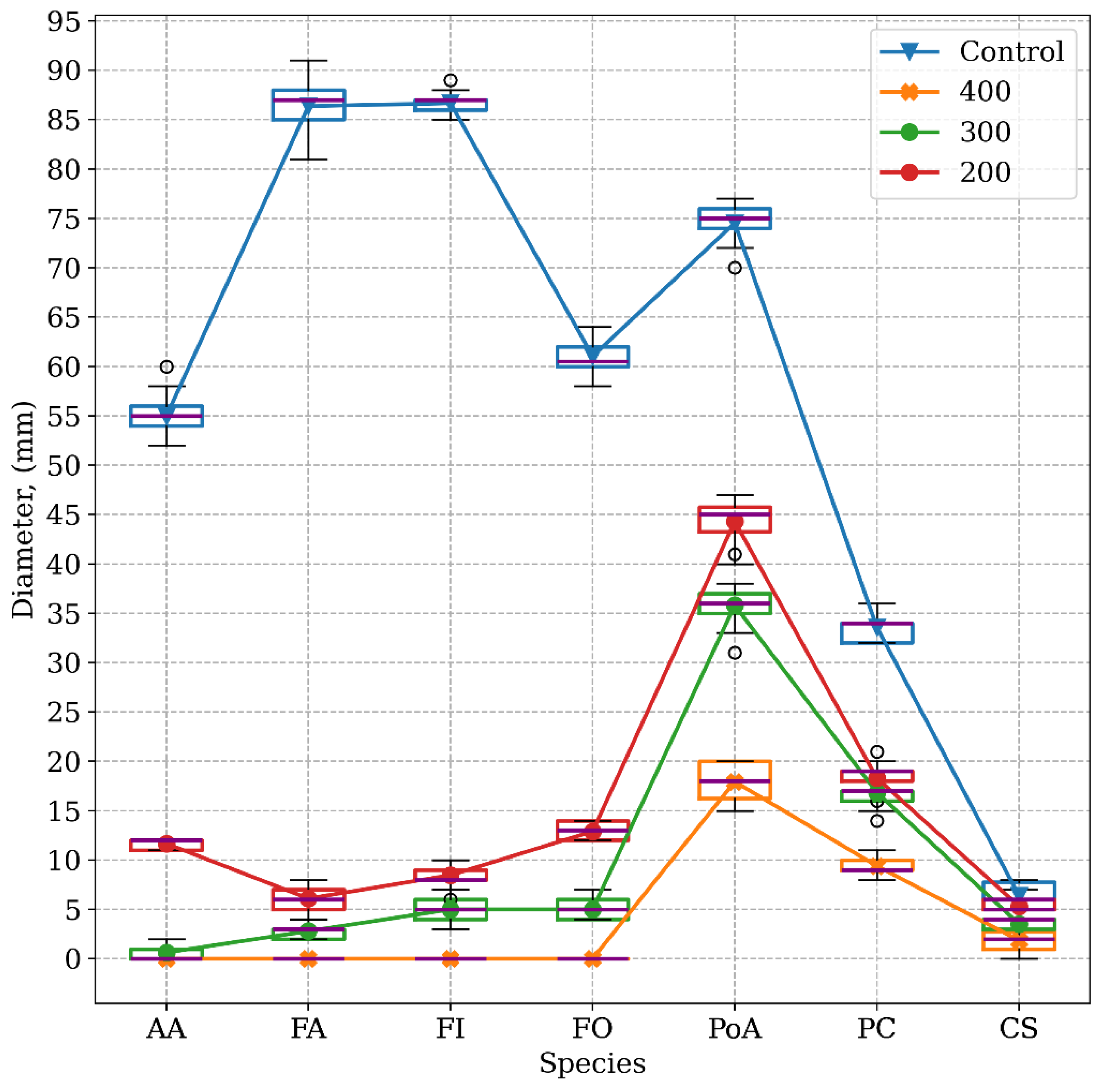

2.2. In vitro Studies. Determining the Antifungal Potential of the Thymus zygis EO. MGI (%) (Mycelial Growth Inhibition)

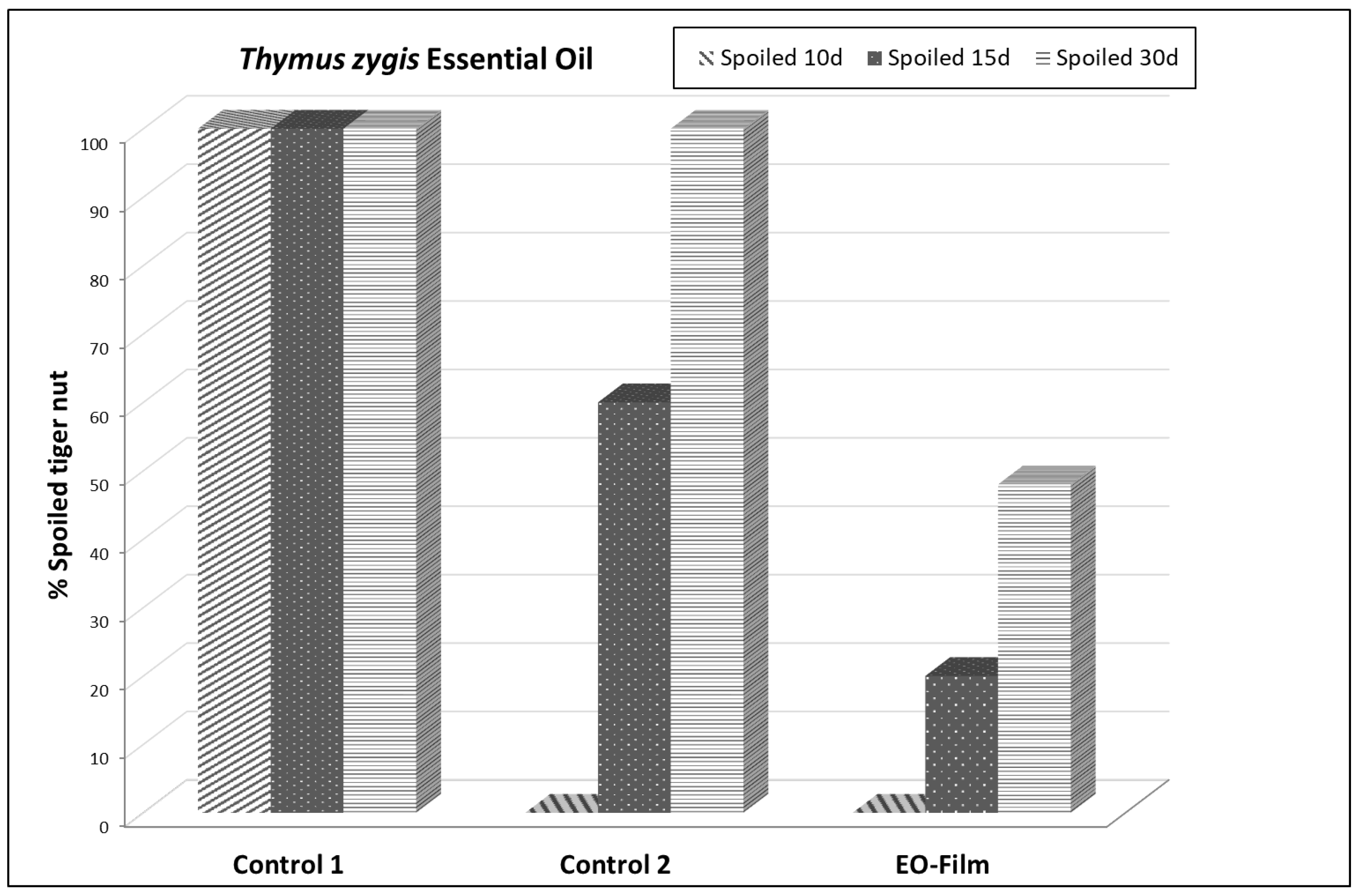

3.2. In Vivo Study of the Antifungal Effect of the Thymus zygis EO Against Fusarium andiyazi on Tiger nuts. EO on Tiger Nut Storage

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal Species

4.2. Fungal Strain Identification

4.3. Essential Oil (EO)

4.4. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis of EOs

4.5. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of the T. zygis EO

2.6. Fungitoxicity of the T. zygis EO in an In Vivo Assay

2.6.1. Fungal Suspensions (FI) and Fungal Biofilm Preparation (FIFi)

2.6.2. T. zygis EO Biofilm (EOFi)

2.6.3. Biofilm Application of the T. zygis EO on (tiger nut) Tubers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:330001-2 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Castroviejo, S. Cyperus L. In Flora Ibérica. Plantas vasculares de la Península Ibérica e Islas Baleares. Castroviejo, S., Luceño, M., Galán, A., Jiménez Mejías, P., Cabezas, F.; Medina, L., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico - CSIC, Madrid, 2007; Volume XVIII, pp. 8–27.

- Serrallach, J. Die wurzelknolle von Cyperus esculentus L. Ph. D. Tesis, University Frankfur am Main, 1927.

- Follak, S.; Belz, R.; Bohren, C.; De Castro, O.; Del Guacchio, E.; Pascual-Seva, N.; Schwarz, M.; Verloove, F.; Essl, F. Biological flora of Central Europe: Cyperus esculentus L. Perspect. Pl. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 23, 33-51. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2016.09.003.

- Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Wei, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Z. Cyperus (Cyperus esculentus L.): A Review of Its Compositions, Medical Efficacy, Antibacterial Activity and Allelopathic Potentials. Plants 2022, 11, 1127. [CrossRef]

- Zuloaga, F.O.; Morrone, O.; Belgrano, M.J. Catálogo de las Plantas Vasculares del Cono Sur (Argentina, Sur de Brasil, Chile, Paraguay y Uruguay); (Eds.), Marticorena, C.; Marchesi, E. (Assoc. Eds); Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, 2008; 3486 pp. ISBN 978-1-930723-70-2.

- Boeckeler, J. Die Cyperaceen des königlichen Herbariums zu Berlin. Linnaea 1870, 36, 287−291.

- Clarke, C.B. On the Indian species of Cyperus. J. Linn. Soc., Bot. 1884, 21, 178−181. [CrossRef]

- Britton, N.L. The sedges of Jamaica (Cyperaceae). Bull. Dept. Agric. Jamaica 1907, 5, Suppl. 1, 1−19.

- Kükenthal, G. Cyperaceae – Scirpoideae – Cypereae. In Das Pflanzenreich. Regni vegetabilis conspectus. Engler, A., Diels, L., Eds., Verlag Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig, 1936; Volume 4 (20), 101.

- Tayyar, R.I., Nguyen, J.H.T., Holt, J.S. Genetic and morphological analysis of two novel nutsedge biotypes from California. Weed Science 2003, 51, 731-739. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Characteristics and Research Progress of Cyperus esculentus L. North. Hortic. 2017, 17, 192–201.

- Tucker, G.C.; Simpson, D.A. Cyperus Linnaeus. In Flora of China; Wu, Z.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Science Press, Beijing, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, 2010; Volume 23, pp. 219−241.

- Guo, T.; Wan, C.; Huang, F.; Wei, C.; Hu, Z. Research Progress on main nutritional components and physiological functions of tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.). Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2021, 43, 1174–1180.

- Consejo Regulador Denominación de Origen Chufa de Valencia. Available online: https://chufadevalencia.org/la-chufa/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Montaño Mata, N.J.; Jiménez García, J. Sintomatología y control de la necrosis foliar de la chufa (Cyperus esculentus L.). Revista Científica UDO Agrícola 2012, 3, 627-638.

- Pascual-Seva, N.; San Bautista, A.; López-Galarza, S.; Maroto, J.V.; Pascual, B. ‘Alboraia’ and ‘Bonrepos’: The First Registered Chufa (Cyperus esculentus L. var. sativus Boeck.) Cultivars. HortScience 2013, 48 (3), 386–389. [CrossRef]

- Hollowell, J.E.; Shew, B.B. Yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.) as a host of Sclerotinia minor. Plant Dis. 2001, 85 (5), 562-562. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.C. Manual of rust in the United State and Canada. Purdue Rest. Foundation, Lafayette, Indiana, 1934; 189 pp.

- Morales-Payan, J.P.; Charudattan, R.; Stall, W.M. Fungi for biological control of weedy Cyperaceae, with emphasis on purple and yellow nutsedges (Cyperus rotundus and C. esculentus). Outlooks Pest Manag. 2005, 14 (4), 148-155. [CrossRef]

- Blaney, C.L.; Van Dyke, C.G. Cercospora caricis from Cyperus esculentus (yellow nutsedge): morphology and cercosporin production. Mycologia 1988, 80, 418–421. [CrossRef]

- García-Jiménez, J.; Busto, J.; Armengol, J.; Martínez Ferrer, G.; Sales, R.; García Morató, M. La podredumbre negra o “alquitranat”: un grave problema de la chufa en Valencia. Agrícola Vergel 1997, 183, 144-148.

- García-Jiménez, J.; Busto, J.; Vicent, A.; Sales, R.; Armengol, J. A tuber rot of Cyperus esculentus caused by Rosellinia necatrix. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 1281. [CrossRef]

- Galipienso Torregrosa, L.; Rubio, L.; Guinot Moreno, F.J.J.; Sanz López, C. Identificación de un virus como el causante de una nueva enfermedad que afecta al cultivo de chufa en Valencia. Phytoma 2022, 344, 50-53. [CrossRef]

- Marsal, J.I.; Cerda, J. J.; Penella, C.; Calatayud, A. Mejora de la sanidad y calidad de la chufa en valencia: Situación actual. Agrícola Vergel: Fruticultura, Horticultura, Floricultura 2017, 402, 205-210. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11939/5877.

- Verdeguer, M.; Roselló, J.; Castell, V.; Llorens, J.A.; Santamarina, M.P. Cherry tomato and persimmon kaki conservation with a natural and biodegradable film. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 2, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Allagui, M.B.; Moumni, M.; Romanazzi, G. Antifungal activity of thirty essential oils to control pathogenic fungi of postharvest decay. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; He, D.; Olaniran, A.O.; Mokoena, M.P.; Xu, J.; Shi, J. Occurrence, toxicity, production and detection of Fusarium mycotoxin: a review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2019, 1, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.I.; Akinola, S.A.; Mwanza, M. Fusarium mycotoxins, their metabolites (free, emerging, and masked), food safety concerns, and health impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18 (22), 11741. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, K.M.; Badeaa, R.I. Effect of oil extracted from some medicinal plants on different mycotoxigenic fungi. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 1669–1675. [CrossRef]

- Roselló J.; Llorens-Molina J.A.; Larran S.; Sempere-Ferre F.; Santamarina M.P. Biofilm containing the Thymus serpyllum essential oil for rice and cherry tomato conservation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1362569. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Sendra, E., Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. In vitro antioxidant and antifungal properties of essential oils obtained from aromatic herbs endemic to the southeast of Spain. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1218–1225. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of essential components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4 th ed.; Allured Publishing Corporation, Carol Stream: Illinois, 2007, 804 pp.

- Sempere-Ferre, F.; Asamar, J.; Castell, V.; Roselló J.; Santamarina, M.P. Evaluating the antifungal potential of botanical compounds to control Botryotinia fuckeliana and Rhizoctonia solani. Molecules 2021, 26, (9), 2472. [CrossRef]

- Sapper, M.; Wilcaso, P.; Santamarina M.P.; Roselló, J.; Chiralt, A. Antifungal and functional properties of starch-gellan films containing thyme (Thymus zygis) essential oil. Food Control 2018, 92, 505-515. [CrossRef]

- Sapper, M.; Palou, L.; Pérez-Gago, M.B.; Chiralt, A. Antifungal starch–gellan edible coatings with Thyme essential oil for the postharvest preservation of apple and persimmon. Coatings 2019, 9, 333. [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; Fungal barcoding consortium; Fungal Barcoding Consortium Author List. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, (16), 6241-6246. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Santamarina, S.; Llorens-Molina, J.C.; Sempere-Ferre, F.; Santamarina, C.; Roselló, J.; Santamarina, M.P. Chemical composition of essential oils of three Mentha species and their antifungal activity against selected phytopathogenic and post-harvest fungi. All Life 2022, 15, 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, C.C. de; Camara, T.R.; Mariano, R. de L.R.; Willadino, L.; Marcelino Junior, C.; Ulisses, C. Antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Lippia gracilis Schauer. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2006, 49, 527–535. [CrossRef]

| RT | LRI lit. | Peak Area (%) Mean ±SD |

Identification Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 39.74±0.19 | |||

| α-thujene | 930 | 930 | 0.01±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| α-pinene | 937 | 939 | 0.38±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| Camphene | 951 | 954 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| trans-pinane | 971 | 975 | 0.01±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| 3-p-menthene | 985 | 987 | 0.12±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Myrcene | 992 | 990 | 0.46±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| α-terpinene | 1018 | 1017 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| p-cymene | 1024 | 1024 | 35.16±0.16 | MS, LRI |

| γ−terpinene | 1061 | 1059 | 3.53±0.02 | MS, LRI |

| Terpinolene | 1088 | 1088 | 0.01±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| p-cymenene | 1089 | 1091 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 59.73±0.34 | |||

| 1,8-cineole | 1033 | 1031 | 0.79±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| cis-linalool oxide | 1074 | 1072 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| trans-linalool oxide | 1086 | 1086 | 0.01±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| 6,7-epoxymyrcene | 1094 | 1092 | 0.01±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| Linalool | 1101 | 1096 | 2.21±0.03 | MS, LRI |

| α-fenchol | 1112 | 1116 | 0.01±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Isoborneol | 1156 | 1160 | 0.25±0.03 | MS, LRI |

| Borneol | 1166 | 1169 | 1.12±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| terpinen-4-ol | 1177 | 1177 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Isocitral | 1179 | 1180 | 0.05±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| Isomenthol | 1180 | 1182 | 0.01±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| α-terpineol | 1189 | 1188 | 0.18±0.02 | MS, LRI |

| γ-terpineol | 1201 | 1199 | 0.16±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| carvacrol methyl ether | 1245 | 1244 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Thymol | 1295 | 1290 | 51.34±0.21 | MS, LRI |

| Carvacrol | 1305 | 1299 | 3.53±0.01 | MS, LRI |

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 0.15±0.00 | |||

| β-caryophyllene | 1417 | 1419 | 0.13±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| α-humulene | 1451 | 1454 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 0.33±0.00 | |||

| caryophyllene oxide | 1578 | 1583 | 0.31±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| humulene epoxide II | 1603 | 1608 | 0.02±0.00 | MS, LRI |

| Total identified | 99.95±0.53 | |||

| Concentration (µg/mL) | AA | FA | FI | FO | PoA | PC | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (XEA) | 54.97 | 86.50 | 86.67 | 61.03 | 74.53 | 33.60 | 6.40 |

| 200 | 11.67 | 6.10 | 8.47 | 12.90 | 44.30 | 18.30 | 5.33 |

| 300 | 0.63 | 2.80 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 35.80 | 16.83 | 3.53 |

| 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17.93 | 9.40 | 1.87 |

| Concentration (µg/mL) | AA | FA | FI | FO | PoA | PC | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 78.77 | 92.95 | 90.23 | 78.86 | 40.56 | 45.54 | 16.72 |

| 300 | 98.85 | 96.76 | 94.23 | 91.81 | 51.97 | 49.91 | 44.84 |

| 300 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75,94 | 72,02 | 70.78 |

| Efficacy on tiger nut (%) | |||||||||

| 10 days | 15 days | 30 days | |||||||

| Treatment | healthy | spotted spot | spoiled | healthy | spotted spot | spoiled | |||

| Control 1 | 0c* | 0c | 100a | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Control 2 | 68b | 32a | 0b | 0b | 40a | 60a | - | 0b | 100a |

| EO-Film | 96a | 4b | 0b | 64a | 20b | 20b | 40a | 12a | 48b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).