Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Malaria remains a persistent challenge in global health, disproportionately affecting populations in endemic regions (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa). Despite decades of international collaborative efforts, this parasitic disease continues to claim hundreds of thousands of lives each year, with young children and pregnant women enduring the heaviest burden of malaria. The introduction of pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines (RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M), represents an important milestone in malaria control efforts with promising results from the erythrocytic vaccine RH5.1/Matrix-M in recent clinical trials. However, the approval of these vaccines is accompanied by significant challenges such as the limited efficacy, the complexity of multi-dose regimens, and numerous barriers to widespread implementation in resource-limited settings. This concise review provides an overview of the historical development and current status of malaria vaccines, tracking their milestones from initial scientific breakthroughs to the deployment of first-generation vaccines. The review also examines the complex challenges to broad malaria vaccination coverage, including logistical barriers, healthcare infrastructure effect, financial limitations, malaria vaccine hesitancy, among other obstacles in malaria-endemic regions. Additionally, we explore promising developments in malaria vaccination, such as next-generation candidates (e.g., mRNA-based vaccines), that hold the potential to offer improved efficacy, longer-lasting protection, and greater scalability. Finally, we emphasize the critical need to integrate malaria vaccination efforts with established malaria control interventions (e.g., insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control strategies, and anti-malarial drugs). Based on this review, we concluded that achieving sustained control of malaria morbidity and mortality will require strong global collaboration, sufficient funding, and continuous efforts to address inequities in access and delivery of malaria control measures including the malaria vaccines.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

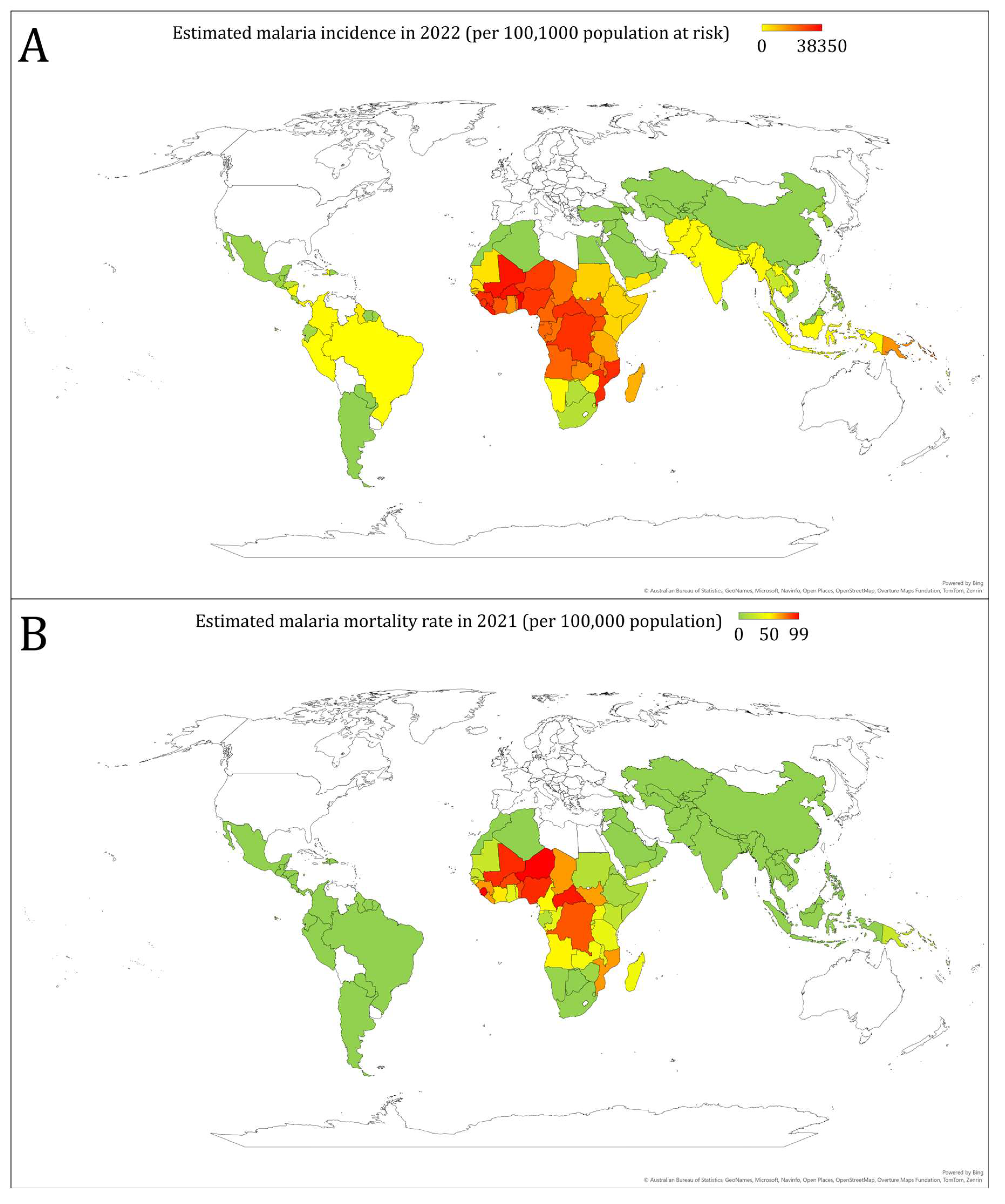

3. Overview of Malaria Burden Worldwide

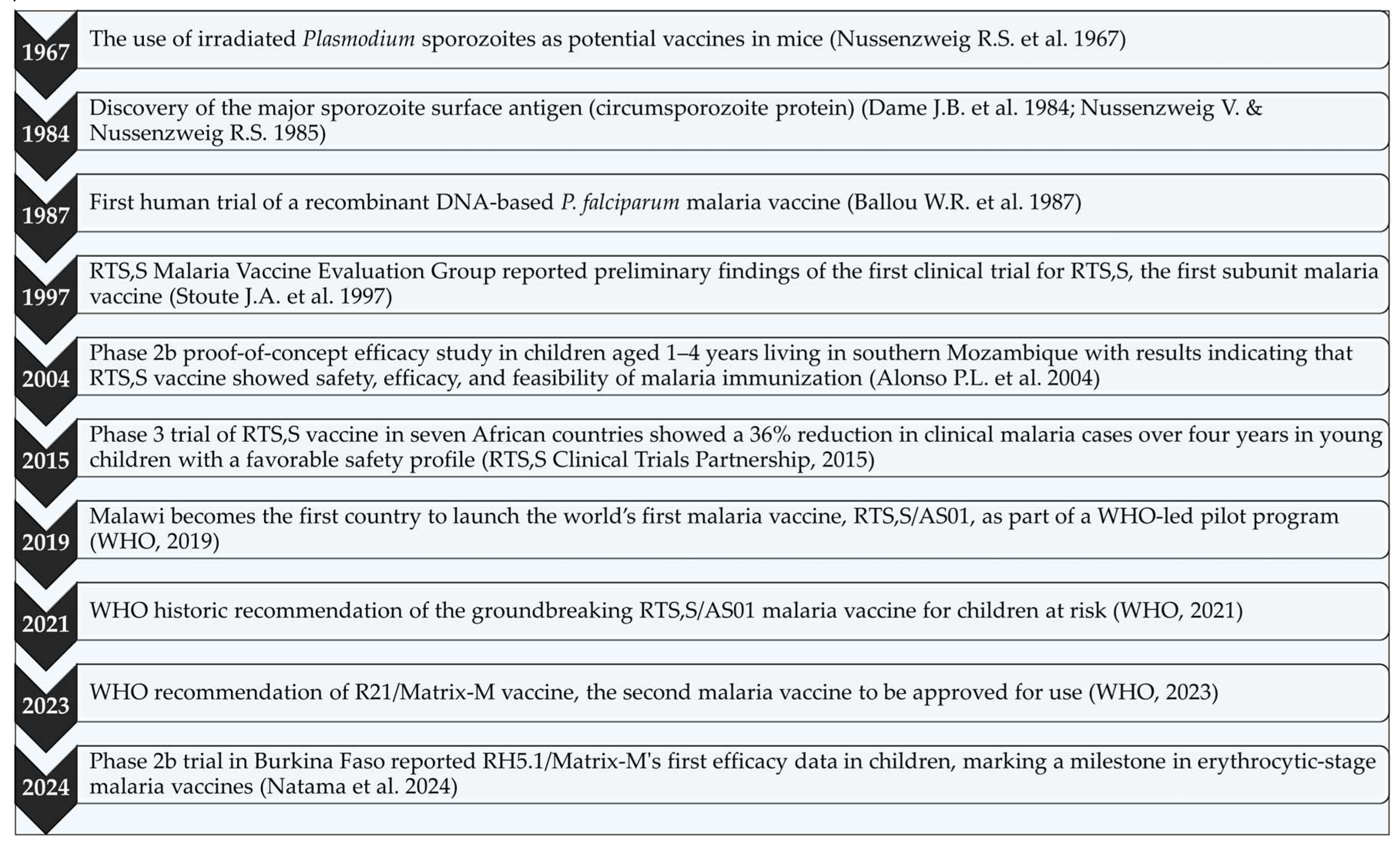

4. Historical Development of Malaria Vaccines

5. Vaccine Efficacy and Safety of RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M Malaria Vaccines

6. Challenges in Malaria Vaccination Implementation

6.1. Vaccine Hesitancy as a Barrier to Successful Malaria Vaccine Implementation

7. Future Directions

7.1. Next-Generation Vaccine Candidates

7.2. Integration with other Malaria Control Measures

7.3. Global Collaboration and Funding

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Adverse event |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ChAd63 | Chimpanzee adenovirus 63 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CSP | Circumsporozoite protein |

| DRC | the Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| DTP3 | Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis |

| HBsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| ME-TRAP | Multiple epitope–thrombospondin-related adhesion protein |

| MVA | modified Vaccinia Ankara |

| P. | Plasmodium |

| RDT | Rapid diagnostic test |

| RH5 | Reticulocyte-binding protein homolog 5 |

| SMC | Seasonal malaria chemoprevention |

| SSA | sub-Saharan Africa |

| TBV | Transmission-blocking vaccine |

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

References

- Makam, P.; Matsa, R. "Big Three" Infectious Diseases: Tuberculosis, Malaria and HIV/AIDS. Curr Top Med Chem 2021, 21, 2779–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Ortblad, K.F.; Guinovart, C.; Lim, S.S.; Wolock, T.M.; Roberts, D.A.; Dansereau, E.A.; Graetz, N.; Barber, R.M.; Brown, J.C.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 1005–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.A.; Burrows, J.N.; Manyando, C.; van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Wells, T.N.C. Malaria. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3, 17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, S.N.; Deshmukh, R.; Trivedi, V. Severe malaria: Biology, clinical manifestation, pathogenesis and consequences. J Vector Borne Dis 2020, 57, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talapko, J.; Škrlec, I.; Alebić, T.; Jukić, M.; Včev, A. Malaria: The Past and the Present. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, K.; Barik, T.K.; Reddy, B.P.; Sharma, P.; Dash, A.P. Malaria vector control: from past to future. Parasitol Res 2011, 108, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schalkwyk, D.A. History of Antimalarial Agents. In eLS; 2015; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wongsrichanalai, C.; Barcus, M.J.; Muth, S.; Sutamihardja, A.; Wernsdorfer, W.H. A Review of Malaria Diagnostic Tools: Microscopy and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2007, 77, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, G.M.; Melo, G.; Nobrega De Sousa, T.; Pucca, M.B. Editorial: Challenges for diagnosis, treatment, and elimination of malaria. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2024, 5, 1394693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Modrek, S.; Gosling, R.D.; Feachem, R.G. Malaria eradication: is it possible? Is it worth it? Should we do it? Lancet Glob Health 2013, 1, e2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, R.; Kissoon, S.; Lakan, V.; Kheswa, N. Rolling back malaria in Africa - challenges and opportunities to winning the elimination battle. S Afr Med J 2019, 109, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, H.J.; Tajudeen, Y.A.; Oladunjoye, I.O.; Yusuff, S.I.; Yusuf, R.O.; Oluwaseyi, E.M.; AbdulBasit, M.O.; Adebisi, Y.A.; El-Sherbini, M.S. Increasing challenges of malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa: Priorities for public health research and policymakers. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 81, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2023; World Health Organization, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfo, J.O.; Amoadu, M.; Kordorwu, P.Y.; Adams, A.K.; Gyan, T.B.; Osman, A.G.; Asiedu, I.; Ansah, E.W. Malaria amongst children under five in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of prevalence, risk factors and preventive interventions. Eur J Med Res 2023, 28, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schantz-Dunn, J.; Nour, N.M. Malaria and pregnancy: a global health perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009, 2, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C.; Karstaedt, A.; Frean, J.; Thomas, J.; Govender, N.; Prentice, E.; Dini, L.; Galpin, J.; Crewe-Brown, H. Increased prevalence of severe malaria in HIV-infected adults in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, M.; Duffy, P.E. Malaria during Pregnancy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jing, W.; Kang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. Trends of the global, regional and national incidence of malaria in 204 countries from 1990 to 2019 and implications for malaria prevention. J Travel Med 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; May, J.; May, M.; Nagy, G.J. Climate change and malaria: some recent trends of malaria incidence rates and average annual temperature in selected sub-Saharan African countries from 2000 to 2018. Malaria Journal 2023, 22, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Moamly, A.A. How can we get malaria control back on track? Bmj 2024, 385, q1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippolito, M.M.; Moser, K.A.; Kabuya, J.B.; Cunningham, C.; Juliano, J.J. Antimalarial Drug Resistance and Implications for the WHO Global Technical Strategy. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2021, 8, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, N.J. Antimalarial drug resistance. J Clin Invest 2004, 113, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, A.; Fola, A.A.; Tasew, G. Emergence of Plasmodium falciparum strains with artemisinin partial resistance in East Africa and the Horn of Africa: is there a need to panic? Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liu, T.; Yu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Antimalarial Mechanisms and Resistance Status of Artemisinin and Its Derivatives. Trop Med Infect Dis 2024, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyant, P.; Corbel, V.; Guérin, P.J.; Lautissier, A.; Nosten, F.; Boyer, S.; Coosemans, M.; Dondorp, A.M.; Sinou, V.; Yeung, S.; et al. Past and new challenges for malaria control and elimination: the role of operational research for innovation in designing interventions. Malaria Journal 2015, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Malaney, P. The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature 2002, 415, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, A.T.; Mallange, G.; Kühl, M.-J.; Okell, L. Cost of treating severe malaria in children in Africa: a systematic literature review. Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F. Social implications of malaria and their relationships with poverty. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012, 4, e2012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, M.V.; Noronha, K.; Diniz, B.P.C.; Guedes, G.; Carvalho, L.R.; Silva, V.A.; Calazans, J.A.; Santos, A.S.; Silva, D.N.; Castro, M.C. The economic burden of malaria: a systematic review. Malaria Journal 2022, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafula, S.T.; Habermann, T.; Franke, M.A.; May, J.; Puradiredja, D.I.; Lorenz, E.; Brinkel, J. What are the pathways between poverty and malaria in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review of mediation studies. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2023, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, P.F.; Elanga-Ndille, E.; Tchouakui, M.; Sandeu, M.M.; Tagne, D.; Wondji, C.; Ndo, C. Impact of insecticide resistance on malaria vector competence: a literature review. Malaria Journal 2023, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkya, T.E.; Akhouayri, I.; Poupardin, R.; Batengana, B.; Mosha, F.; Magesa, S.; Kisinza, W.; David, J.-P. Insecticide resistance mechanisms associated with different environments in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae: a case study in Tanzania. Malaria Journal 2014, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H. Combating Malaria with Vaccines: Insights from the One Health Framework. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 2024, 69, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M.; Okumu, F.; Moonen, B. The fight against malaria: Diminishing gains and growing challenges. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabn3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Moamly, A.A.; El-Sweify, M.A. Malaria vaccines: the 60-year journey of hope and final success—lessons learned and future prospects. Tropical Medicine and Health 2023, 51, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, V.S.; Good, M.F.; Hill, A.V. Malaria vaccine developments. Lancet 2004, 363, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizifa, T.A.; Kabaghe, A.N.; McCann, R.S.; van den Berg, H.; Van Vugt, M.; Phiri, K.S. Prevention Efforts for Malaria. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 2018, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constenla, D. Assessing the economic benefits of vaccines based on the health investment life course framework: a review of a broader approach to evaluate malaria vaccination. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauboin, C.J.; Van Bellinghen, L.A.; Van De Velde, N.; Van Vlaenderen, I. Potential public health impact of RTS,S malaria candidate vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa: a modelling study. Malar J 2015, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, P.D.; Pierce, S.K.; Miller, L.H. Advances and challenges in malaria vaccine development. J Clin Invest 2010, 120, 4168–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, V.; Karanis, P. Malaria vaccines: looking back and lessons learnt. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011, 1, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, V.; Karanis, G.; Karanis, P. Malaria vaccine development and how external forces shape it: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014, 11, 6791–6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, P.E.; Sahu, T.; Akue, A.; Milman, N.; Anderson, C. Pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines: identifying the targets. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012, 11, 1261–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Pan, H.; Gu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Ran, N.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, F. Prospects for Malaria Vaccines: Pre-Erythrocytic Stages, Blood Stages, and Transmission-Blocking Stages. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019, 9751471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richie, T.L.; Billingsley, P.F.; Sim, B.K.; James, E.R.; Chakravarty, S.; Epstein, J.E.; Lyke, K.E.; Mordmüller, B.; Alonso, P.; Duffy, P.E.; et al. Progress with Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite (PfSPZ)-based malaria vaccines. Vaccine 2015, 33, 7452–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougan, T.; Ito, K.; Palacpac, N.M.; Egwang, T.G.; Horii, T. Immunogenicity and protection from malaria infection in BK-SE36 vaccinated volunteers in Uganda is not influenced by HLA-DRB1 alleles. Parasitol Int 2016, 65, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varo, R.; Chaccour, C.; Bassat, Q. Update on malaria. Med Clin (Barc) 2020, 155, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurens, M.B. RTS,S/AS01 vaccine (Mosquirix™): an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques-da-Silva, C.; Peissig, K.; Kurup, S.P. Pre-Erythrocytic Vaccines against Malaria. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, F.; Tam, J.P.; Hollingdale, M.R.; Cochrane, A.H.; Quakyi, I.; Nussenzweig, R.S.; Nussenzweig, V. Rationale for development of a synthetic vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Science 1985, 228, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Egbewande, O.M. The RTS,S malaria vaccine: Journey from conception to recommendation. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2022, 4, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine (Mosquirix®): a profile of its use. Drugs & Therapy Perspectives 2022, 38, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Mukaka, M.; Jittamala, P.; Poovorawan, K.; Pongsuwan, P.; Stockdale, L.; Provstgaard-Morys, S.; Chotivanich, K.; Tarning, J.; Hoglund, R.M.; et al. A randomised trial of malaria vaccine R21/Matrix-M™ with and without antimalarial drugs in Thai adults. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Sikirullahi, S.; Aboje, J.E.; Ojabo, R.E. A perspective on Oxford's R21/Matrix-M™ malaria vaccine and the future of global eradication efforts. Malar J 2024, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine: Evidence to recommendations framework, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/r21-matrix-m-malaria-vaccine--evidence-to-recommendations-framework--2023 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Moorthy, V.; Hamel, M.J.; Smith, P.G. Malaria vaccines for children: and now there are two. Lancet 2024, 403, 504–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumani, M.E.; Voyiatzaki, C.; Efstathiou, A. Malaria Vaccines: From the Past towards the mRNA Vaccine Era. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarazzo, L.; Bettencourt, P.J.G. mRNA vaccines: a new opportunity for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1172691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkens, Y. Malaria & mRNA Vaccines: A Possible Salvation from One of the Most Relevant Infectious Diseases of the Global South. Acta Parasitologica 2023, 68, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Tang, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, C. Recent Advances in the Molecular Design and Delivery Technology of mRNA for Vaccination Against Infectious Diseases. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 896958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, B.; Dicko, A.; Sagara, I.; Zongo, I.; Tinto, H.; Cairns, M.; Kuepfer, I.; Milligan, P.; Ouedraogo, J.B.; Doumbo, O.; et al. Seasonal vaccination against malaria: a potential use for an imperfect malaria vaccine. Malar J 2017, 16, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubillos, I.; Ayestaran, A.; Nhabomba, A.J.; Dosoo, D.; Vidal, M.; Jiménez, A.; Jairoce, C.; Sanz, H.; Aguilar, R.; Williams, N.A.; et al. Baseline exposure, antibody subclass, and hepatitis B response differentially affect malaria protective immunity following RTS,S/AS01E vaccination in African children. BMC Med 2018, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicko, A.; Ouedraogo, J.-B.; Zongo, I.; Sagara, I.; Cairns, M.; Yerbanga, R.S.; Issiaka, D.; Zoungrana, C.; Sidibe, Y.; Tapily, A.; et al. Seasonal vaccination with RTS,S/AS01<sub>E</sub> vaccine with or without seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children up to the age of 5 years in Burkina Faso and Mali: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandramohan, D.; Zongo, I.; Sagara, I.; Cairns, M.; Yerbanga, R.S.; Diarra, M.; Nikièma, F.; Tapily, A.; Sompougdou, F.; Issiaka, D.; et al. Seasonal Malaria Vaccination with or without Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, V.A.; Gueye, A.; Ndiaye, M.; Edwards, N.J.; Wright, D.; Anagnostou, N.A.; Syll, M.; Ndaw, A.; Abiola, A.; Bliss, C.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Prime-Boost Vaccination with ChAd63 and MVA Encoding ME-TRAP against Plasmodium falciparum Infection in Adults in Senegal. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, H.; Payne, R.O.; Taylor, I.; Miura, K.; Long, C.A.; Elias, S.C.; Zaric, M.; Minassian, A.M.; Silk, S.E.; Li, L.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of ChAd63/MVA Pfs25-IMX313 in a Phase I First-in-Human Trial. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 694759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaric, M.; Marini, A.; Nielsen, C.M.; Gupta, G.; Mekhaiel, D.; Pham, T.P.; Elias, S.C.; Taylor, I.J.; de Graaf, H.; Payne, R.O.; et al. Poor CD4(+) T Cell Immunogenicity Limits Humoral Immunity to P. falciparum Transmission-Blocking Candidate Pfs25 in Humans. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 732667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, S.M.I.; Amarasekara, S.; Wickremasinghe, R.; Fernando, D.; Udagama, P. Prevention of re-establishment of malaria: historical perspective and future prospects. Malaria Journal 2020, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Docile, H.J.; Fisher, D.; Pronyuk, K.; Zhao, L. Current Status of Malaria Control and Elimination in Africa: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, Progress and Challenges. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 2024, 14, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibulskis, R.E.; Alonso, P.; Aponte, J.; Aregawi, M.; Barrette, A.; Bergeron, L.; Fergus, C.A.; Knox, T.; Lynch, M.; Patouillard, E.; et al. Malaria: Global progress 2000 – 2015 and future challenges. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2016, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parija, S.C. The persistent challenges of malaria. Trop Parasitol 2021, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, S.I.; Smith, D.L.; Snow, R.W. Measuring malaria endemicity from intense to interrupted transmission. Lancet Infect Dis 2008, 8, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Lucas, T.C.D.; Nguyen, M.; Nandi, A.K.; Bisanzio, D.; Battle, K.E.; Cameron, E.; Twohig, K.A.; Pfeffer, D.A.; Rozier, J.A.; et al. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000-17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet 2019, 394, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battle, K.E.; Lucas, T.C.D.; Nguyen, M.; Howes, R.E.; Nandi, A.K.; Twohig, K.A.; Pfeffer, D.A.; Cameron, E.; Rao, P.C.; Casey, D.; et al. Mapping the global endemicity and clinical burden of Plasmodium vivax, 2000-17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet 2019, 394, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO malaria terminology, 2021 update. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038400 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Autino, B.; Noris, A.; Russo, R.; Castelli, F. Epidemiology of malaria in endemic areas. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012, 4, e2012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Malaria - Key facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Mbishi, J.V.; Chombo, S.; Luoga, P.; Omary, H.J.; Paulo, H.A.; Andrew, J.; Addo, I.Y. Malaria in under-five children: prevalence and multi-factor analysis of high-risk African countries. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory: Malaria burden data: cases and deaths. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/malaria-cases-deaths (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Hill, A.V. Vaccines against malaria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011, 366, 2806–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.L.; Vekemans, J.; Richie, T.L.; Duffy, P.E. The march toward malaria vaccines. Vaccine 2015, 33 Suppl 4, D13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S. Plasmodium-a brief introduction to the parasites causing human malaria and their basic biology. J Physiol Anthropol 2021, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richie, T. High road, low road? Choices and challenges on the pathway to a malaria vaccine. Parasitology 2006, 133 Suppl, S113–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussenzweig, R.S.; Vanderberg, J.; Most, H.; Orton, C. Protective immunity produced by the injection of x-irradiated sporozoites of plasmodium berghei. Nature 1967, 216, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dame, J.B.; Williams, J.L.; McCutchan, T.F.; Weber, J.L.; Wirtz, R.A.; Hockmeyer, W.T.; Maloy, W.L.; Haynes, J.D.; Schneider, I.; Roberts, D.; et al. Structure of the gene encoding the immunodominant surface antigen on the sporozoite of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science 1984, 225, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussenzweig, V.; Nussenzweig, R.S. Circumsporozoite proteins of malaria parasites. Cell 1985, 42, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussenzweig, R.S.; Nussenzweig, V. Development of sporozoite vaccines. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1984, 307, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, W.R.; Hoffman, S.L.; Sherwood, J.A.; Hollingdale, M.R.; Neva, F.A.; Hockmeyer, W.T.; Gordon, D.M.; Schneider, I.; Wirtz, R.A.; Young, J.F.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a recombinant DNA Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite vaccine. Lancet 1987, 1, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoute, J.A.; Slaoui, M.; Heppner, D.G.; Momin, P.; Kester, K.E.; Desmons, P.; Wellde, B.T.; Garçon, N.; Krzych, U.; Marchand, M. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. RTS,S Malaria Vaccine Evaluation Group. N Engl J Med 1997, 336, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.L.; Sacarlal, J.; Aponte, J.J.; Leach, A.; Macete, E.; Milman, J.; Mandomando, I.; Spiessens, B.; Guinovart, C.; Espasa, M.; et al. Efficacy of the RTS,S/AS02A vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum infection and disease in young African children: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTS, S.C.T.P. Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Malaria vaccine pilot launched in Malawi. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-04-2019-malaria-vaccine-pilot-launched-in-malawi (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Natama, H.M.; Salkeld, J.; Somé, A.; Soremekun, S.; Diallo, S.; Traoré, O.; Rouamba, T.; Ouédraogo, F.; Ouédraogo, E.; Daboné, K.C.S.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the blood-stage malaria vaccine RH5.1/Matrix-M in Burkina Faso: interim results of a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2b trial in children. Lancet Infect Dis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderberg, J.P. Reflections on early malaria vaccine studies, the first successful human malaria vaccination, and beyond. Vaccine 2009, 27, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richie, T.L.; Saul, A. Progress and challenges for malaria vaccines. Nature 2002, 415, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.F.; Hockmeyer, W.T.; Gross, M.; Ballou, W.R.; Wirtz, R.A.; Trosper, J.H.; Beaudoin, R.L.; Hollingdale, M.R.; Miller, L.H.; Diggs, C.L.; et al. Expression of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite proteins in Escherichia coli for potential use in a human malaria vaccine. Science 1985, 228, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Franky, J.; Cuy-Chaparro, L.; Camargo, A.; Reyes, C.; Gómez, M.; Salamanca, D.R.; Patarroyo, M.A.; Patarroyo, M.E. Plasmodium falciparum pre-erythrocytic stage vaccine development. Malar J 2020, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppi, A.; Natarajan, R.; Pradel, G.; Bennett, B.L.; James, E.R.; Roggero, M.A.; Corradin, G.; Persson, C.; Tewari, R.; Sinnis, P. The malaria circumsporozoite protein has two functional domains, each with distinct roles as sporozoites journey from mosquito to mammalian host. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, J.J.; Aponte, J.J.; Skinner, J.; Nakajima, R.; Molina, D.M.; Liang, L.; Sacarlal, J.; Alonso, P.L.; Crompton, P.D.; Felgner, P.L.; et al. RTS,S vaccination is associated with serologic evidence of decreased exposure to Plasmodium falciparum liver- and blood-stage parasites. Mol Cell Proteomics 2015, 14, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradin, G.; Céspedes, N.; Verdini, A.; Kajava, A.V.; Arévalo-Herrera, M.; Herrera, S. Chapter 5 - Malaria Vaccine Development Using Synthetic Peptides as a Technical Platform. In Advances in Immunology, Melief, C.J.M., Ed.; Academic Press: 2012; Volume 114, pp. 107–149. [CrossRef]

- Roman, F.; Burny, W.; Ceregido, M.A.; Laupèze, B.; Temmerman, S.T.; Warter, L.; Coccia, M. Adjuvant system AS01: from mode of action to effective vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2024, 23, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Full Evidence Report on the RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/mvip/full-evidence-report-on-the-rtss-as01-malaria-vaccine-for-sage-mpag- (accessed on day month year).

- World Health Organization. RTS,S malaria vaccine reaches more than 650 000 children in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi through groundbreaking pilot programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-04-2021-rts-s-malaria-vaccine-reaches-more-than-650-000-children-in-ghana-kenya-and-malawi-through-groundbreaking-pilot-programme (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Björkman, A.; Benn, C.S.; Aaby, P.; Schapira, A. RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine—proven safe and effective? The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, e318–e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnis, P.; Fidock, D.A. The RTS,S vaccine—a chance to regain the upper hand against malaria? Cell 2022, 185, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Sikirullahi, S.; Aboje, J.E.; Ojabo, R.E. A perspective on Oxford’s R21/Matrix-M™ malaria vaccine and the future of global eradication efforts. Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datoo, M.S.; Natama, M.H.; Somé, A.; Traoré, O.; Rouamba, T.; Bellamy, D.; Yameogo, P.; Valia, D.; Tegneri, M.; Ouedraogo, F.; et al. Efficacy of a low-dose candidate malaria vaccine, R21 in adjuvant Matrix-M, with seasonal administration to children in Burkina Faso: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datoo, M.S.; Dicko, A.; Tinto, H.; Ouédraogo, J.B.; Hamaluba, M.; Olotu, A.; Beaumont, E.; Ramos Lopez, F.; Natama, H.M.; Weston, S.; et al. Safety and efficacy of malaria vaccine candidate R21/Matrix-M in African children: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datoo, M.S.; Natama, H.M.; Somé, A.; Bellamy, D.; Traoré, O.; Rouamba, T.; Tahita, M.C.; Ido, N.F.A.; Yameogo, P.; Valia, D.; et al. Efficacy and immunogenicity of R21/Matrix-M vaccine against clinical malaria after 2 years' follow-up in children in Burkina Faso: a phase 1/2b randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. WHO recommends second vaccine for malaria prevention in children. BMJ 2023, 383, p2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genton, B. R21/Matrix-M™ malaria vaccine: a new tool to achieve WHO's goal to eliminate malaria in 30 countries by 2030? J Travel Med 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacpac, N.M.Q.; Horii, T. RH5.1/Matrix-M: highlighting blood-stage malaria vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silk, S.E.; Kalinga, W.F.; Salkeld, J.; Mtaka, I.M.; Ahmed, S.; Milando, F.; Diouf, A.; Bundi, C.K.; Balige, N.; Hassan, O.; et al. Blood-stage malaria vaccine candidate RH5.1/Matrix-M in healthy Tanzanian adults and children; an open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human, single-centre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L.D.W.; Pulido, D.; Barrett, J.R.; Davies, H.; Quinkert, D.; Lias, A.M.; Silk, S.E.; Pattinson, D.J.; Diouf, A.; Williams, B.G.; et al. Preclinical development of a stabilized RH5 virus-like particle vaccine that induces improved antimalarial antibodies. Cell Rep Med 2024, 5, 101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.D.; Williams, A.R.; Illingworth, J.J.; Kamuyu, G.; Biswas, S.; Goodman, A.L.; Wyllie, D.H.; Crosnier, C.; Miura, K.; Wright, G.J.; et al. The blood-stage malaria antigen PfRH5 is susceptible to vaccine-inducible cross-strain neutralizing antibody. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragotte, R.J.; Higgins, M.K.; Draper, S.J. The RH5-CyRPA-Ripr Complex as a Malaria Vaccine Target. Trends Parasitol 2020, 36, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenson, A.J.; Laurens, M.B. A new landscape for malaria vaccine development. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanoi, B.N.; Maina, M.; Likhovole, C.; Kobia, F.M.; Gitaka, J. Malaria vaccine approaches leveraging technologies optimized in the COVID-19 era. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2022, 3, 988665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewer, K.J.; Sierra-Davidson, K.; Salman, A.M.; Illingworth, J.J.; Draper, S.J.; Biswas, S.; Hill, A.V.S. Progress with viral vectored malaria vaccines: A multi-stage approach involving “unnatural immunity”. Vaccine 2015, 33, 7444–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Sandoval, A.; Harty, J.T.; Todryk, S.M. Viral vector vaccines make memory T cells against malaria. Immunology 2007, 121, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milicic, A.; Rollier, C.S.; Tang, C.K.; Longley, R.; Hill, A.V.S.; Reyes-Sandoval, A. Adjuvanting a viral vectored vaccine against pre-erythrocytic malaria. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.; Weissman, D.; Whitehead, K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaria, P.V.; Roth, N.; Schwendt, K.; Muratova, O.V.; Alani, N.; Lambert, L.E.; Barnafo, E.K.; Rowe, C.G.; Zaidi, I.U.; Rausch, K.M.; et al. mRNA vaccines expressing malaria transmission-blocking antigens Pfs25 and Pfs230D1 induce a functional immune response. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoni, M. mRNA vaccine against malaria effective in preclinical model. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurens, M.B. Novel malaria vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021, 17, 4549–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-obeidee, M.; Al-obeidee, E. A new era in malaria prevention: a comparative look at RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M vaccines. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2024, 100, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogieuhi, I.J.; Ajekiigbe, V.O.; Kolo-Manma, K.; Akingbola, A.; Odeniyi, T.A.; Soyemi, T.S.; Ayomide, J.H.; Thiyagarajan, B.; Awolola, B.D. A narrative review of the RTS S AS01 malaria vaccine and its implementation in Africa to reduce the global malaria burden. Discover Public Health 2024, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, M.R.; Okine, R.; Tweneboah, P.O.; Baafi, J.V.; Afriyie, N.A.; Teviu, E.A.A.; Nyuzaghl, J.A.-I.; Dzotsi, E.K.; Ohene, S.-A.; Grobusch, M.P. The impact of the RTS,S malaria vaccine on uncomplicated malaria: evidence from the phase IV study districts, Upper East Region, Ghana, 2020–2022. Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penny, M.A.; Galactionova, K.; Tarantino, M.; Tanner, M.; Smith, T.A. The public health impact of malaria vaccine RTS,S in malaria endemic Africa: country-specific predictions using 18 month follow-up Phase III data and simulation models. BMC Med 2015, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.T.; Verity, R.; Griffin, J.T.; Asante, K.P.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Greenwood, B.; Drakeley, C.; Gesase, S.; Lusingu, J.; Ansong, D.; et al. Immunogenicity of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine and implications for duration of vaccine efficacy: secondary analysis of data from a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2015, 15, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, A.M.; Ansong, D.; Kariuki, S.K.; Adjei, S.; Bollaerts, A.; Ockenhouse, C.; Westercamp, N.; Lee, C.K.; Schuerman, L.; Bii, D.K.; et al. Efficacy of RTS,S/AS01(E) malaria vaccine administered according to different full, fractional, and delayed third or early fourth dose regimens in children aged 5-17 months in Ghana and Kenya: an open-label, phase 2b, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.; Vidal, M.; Jairoce, C.; Aguilar, R.; Ubillos, I.; Cuamba, I.; Nhabomba, A.J.; Williams, N.A.; Díez-Padrisa, N.; Cavanagh, D.; et al. Antibody responses to the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine and Plasmodium falciparum antigens after a booster dose within the phase 3 trial in Mozambique. npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neafsey, D.E.; Juraska, M.; Bedford, T.; Benkeser, D.; Valim, C.; Griggs, A.; Lievens, M.; Abdulla, S.; Adjei, S.; Agbenyega, T.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Protective Efficacy of the RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 2025–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yihunie, W.; Kebede, B.; Tegegne, B.A.; Getachew, M.; Abebe, D.; Aschale, Y.; Belew, H.; Bahiru, B. Systematic Review of Safety of RTS,S with AS01 and AS02 Adjuvant Systems Using Data from Randomized Controlled Trials in Infants, Children, and Adults. Clin Pharmacol 2023, 15, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chutiyami, M.; Saravanakumar, P.; Bello, U.M.; Salihu, D.; Adeleye, K.; Kolo, M.A.; Dawa, K.K.; Hamina, D.; Bhandari, P.; Sulaiman, S.K.; et al. Malaria vaccine efficacy, safety, and community perception in Africa: a scoping review of recent empirical studies. Infection 2024, 52, 2007–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Mendoza, Y.; Garric, E.; Leach, A.; Lievens, M.; Ofori-Anyinam, O.; Pirçon, J.Y.; Stegmann, J.U.; Vandoolaeghe, P.; Otieno, L.; Otieno, W.; et al. Safety profile of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in infants and children: additional data from a phase III randomized controlled trial in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, K.P.; Ansong, D.; Kaali, S.; Adjei, S.; Lievens, M.; Nana Badu, L.; Agyapong Darko, P.; Boakye Yiadom Buabeng, P.; Boahen, O.; Maria Rettig, T.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine co-administered with measles, rubella and yellow fever vaccines in Ghanaian children: A phase IIIb, multi-center, non-inferiority, randomized, open, controlled trial. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3411–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. Ghana approves Oxford's malaria vaccine for children aged 5 to 36 months. Bmj 2023, 381, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammershaimb, E.A.; Berry, A.A. Pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines: RTS,S, R21, and beyond. Expert Rev Vaccines 2024, 23, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmit, N.; Topazian, H.M.; Natama, H.M.; Bellamy, D.; Traoré, O.; Somé, M.A.; Rouamba, T.; Tahita, M.C.; Bonko, M.D.A.; Sourabié, A.; et al. The public health impact and cost-effectiveness of the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.K.; Baker, P.; Ngo, K.N. Cost-effectiveness analysis of vaccinating children in Malawi with RTS,S vaccines in comparison with long-lasting insecticide-treated nets. Malar J 2014, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thellier, M.; Gemegah, A.A.J.; Tantaoui, I. Global Fight against Malaria: Goals and Achievements 1900-2022. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matola, Y.; Chumbi, G.; Moyo, C.S.; Bwanali, A.; Lubanga, A.F. Beyond RTS,S malaria vaccine piloting to adoption and historic introduction in sub-Saharan Africa: a new hope in the fight against the vector-borne disease. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2024, 5, 1387078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, J.G.; Kurtovic, L.; Dobaño, C.; Opi, D.H.; Chan, J.A.; Feng, G.; Good, M.F.; Reiling, L.; Boyle, M.J. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okesanya, O.J.; Atewologun, F.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Adigun, O.A.; Oso, T.A.; Manirambona, E.; Olabode, N.O.; Eshun, G.; Agboola, A.O.; Okon, I.I. Bridging the gap to malaria vaccination in Africa: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2024, 2, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Bange, T.; Hoyt, J.; Kariuki, S.; Jalloh, M.F.; Webster, J.; Okello, G. Integration of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine into the Essential Programme on Immunisation in western Kenya: a qualitative longitudinal study from the health system perspective. Lancet Glob Health 2024, 12, e672–e684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.; Gyan, T.; Agbokey, F.; Webster, J.; Greenwood, B.; Asante, K.P. Challenges and lessons learned during the planning and early implementation of the RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine in three regions of Ghana: a qualitative study. Malaria Journal 2022, 21, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimo, F. Malaria vaccination: hurdles to reach high-risk children. BMC Med 2024, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, M.R.; Amponsa-Achiano, K.; Okine, R.; Tweneboah, P.O.; Sally, E.T.; Dadzie, J.F.; Osei-Sarpong, F.; Adjabeng, M.J.; Bawa, J.T.; Bonsu, G.; et al. Post introduction evaluation of the malaria vaccine implementation programme in Ghana, 2021. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortpied, J.; Collignon, S.; Moniotte, N.; Renaud, F.; Bayat, B.; Lemoine, D. The thermostability of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine can be increased by co-lyophilizing RTS,S and AS01. Malaria Journal 2020, 19, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeshina, O.O.; Nyame, S.; Milner, J.; Milojevic, A.; Asante, K.P. Barriers and facilitators to nationwide implementation of the malaria vaccine in Ghana. Health Policy Plan 2023, 38, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwenkeu, S.F.; Jalloh, M.F.; Walldorf, J.A.; Zoma, R.L.; Tarbangdo, F.; Fall, S.; Hien, S.; Combassere, R.; Ky, C.; Kambou, L.; et al. Health workers' perceptions and challenges in implementing meningococcal serogroup a conjugate vaccine in the routine childhood immunization schedule in Burkina Faso. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawade, D.B.; Wada, O.Z.; Ezeagu, C.N.; Aderinto, N.; Balogun, M.A.; Asaolu, F.T.; David-Olawade, A.C. Malaria vaccination in Africa: A mini-review of challenges and opportunities. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e38565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tackling malaria in countries hardest hit by the disease: ministerial conference report, Yaoundé, Cameroon, 6 March 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240100459 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Adamu, A.A.; Jalo, R.I.; Ndwandwe, D.; Wiysonge, C.S. Assessing the Implementation Determinants of Pilot Malaria Vaccination Programs in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi through a Complexity Lens: A Rapid Review Using a Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarocostas, J. Gavi unveils malaria vaccine plans. Lancet 2023, 401, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumu, F.; Gyapong, M.; Casamitjana, N.; Castro, M.C.; Itoe, M.A.; Okonofua, F.; Tanner, M. What Africa can do to accelerate and sustain progress against malaria. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, S.K.; Musa, M.S.; Tsiga-Ahmed, F.I.; Dayyab, F.M.; Sulaiman, A.K.; Bako, A.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of caregiver acceptance of malaria vaccine for under-five children in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). PLoS One 2022, 17, e0278224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, T.O.; Ajibola, O.A.; Oluwole, O.E.; Adeyinka, K.O.; Dada, S.O.; Okoro, O.N. Looking Beyond the Malaria Vaccine Approval to Acceptance and Adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2022, 3, 857844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigongo, E.; Kabunga, A.; Opollo, M.S.; Tumwesigye, R.; Musinguzi, M.; Akello, A.R.; Nabaziwa, J.; Hardido, T.G.; Puleh, S.S. Community readiness and acceptance for the implementation of a novel malaria vaccine among at-risk children in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review protocol. Malar J 2024, 23, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Nadeem, A.; Bilal, W.; Ansar, F.; Saleem, S.; Khan, Q.A.; Tango, T.; Farkouh, C.; Belay, N.F.; Verma, R.; et al. Acceptance, availability, and feasibility of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine: A review. Immun Inflamm Dis 2023, 11, e899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, V.; Mohammed, A.; Kusi-Amponsah, A.; Armah, J.; Lomotey, A.Y.; Budu, H.I.; Atta Poku, C.; Kyei-Dompim, J.; Dwumfour, C. Caregivers' perception and acceptance of malaria vaccine for Children. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0288686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojakaa, D.I.; Jarvis, J.D.; Matilu, M.I.; Thiam, S. Acceptance of a malaria vaccine by caregivers of sick children in Kenya. Malar J 2014, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyalundja, A.D.; Bugeme, P.M.; Guillaume, A.S.; Ntaboba, A.B.; Hatu'm, V.U.; Tamuzi, J.L.; Ndwandwe, D.; Iwu-Jaja, C.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Katoto, P. Socio-Demographic Factors Influencing Malaria Vaccine Acceptance for Under-Five Children in a Malaria-Endemic Region: A Community-Based Study in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtenga, S.; Kimweri, A.; Romore, I.; Ali, A.; Exavery, A.; Sicuri, E.; Tanner, M.; Abdulla, S.; Lusingu, J.; Kafuruki, S. Stakeholders' opinions and questions regarding the anticipated malaria vaccine in Tanzania. Malar J 2016, 15, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.A.; Afrin, S.; Bonna, A.S.; Rozars, M.F.K.; Nabi, M.H.; Hawlader, M.D.H. Knowledge and acceptance of malaria vaccine among parents of under-five children of malaria endemic areas in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Health Expect 2023, 26, 2630–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, F.; Azzam, A.; Rauf, M.S.; Ajmal, Z.; Asad Ullah, G.; Rauf, S.; Akram, R.; Ghauri, F.K.; Chudhary, F.; Iftikhar, H.; et al. Global Analysis of RTS, S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine Acceptance Rates and Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e60678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- editorial - ClinicalMedicine. Malaria: (still) a global health priority. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutiyami, M. Recent Trends in Malaria Vaccine Research Globally: A Bibliometric Analysis From 2005 to 2022. J Parasitol Res 2024, 2024, 8201097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Flores-Garcia, Y.; Long, C.A.; Zavala, F. Vaccines and monoclonal antibodies: new tools for malaria control. Clin Microbiol Rev 2024, 37, e0007123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.; Flores-Garcia, Y.; Mayer, B.T.; MacGill, R.S.; Borate, B.; Salgado-Jimenez, B.; Gerber, M.W.; Mathis-Torres, S.; Shapiro, S.; King, C.R.; et al. Establishing RTS,S/AS01 as a benchmark for comparison to next-generation malaria vaccines in a mouse model. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, S.J.; Sack, B.K.; King, C.R.; Nielsen, C.M.; Rayner, J.C.; Higgins, M.K.; Long, C.A.; Seder, R.A. Malaria Vaccines: Recent Advances and New Horizons. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, I.; Shakri, A.R.; Chitnis, C.E. Development of vaccines for Plasmodium vivax malaria. Vaccine 2015, 33, 7489–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.N.; Commons, R.J.; Battle, K.E.; Thriemer, K.; Mendis, K. Plasmodium vivax in the Era of the Shrinking P. falciparum Map. Trends Parasitol 2020, 36, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Daily, J.P. Update on pathogenesis, management, and control of Plasmodium vivax. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2022, 35, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Veiga, G.T.S.; Moriggi, M.R.; Vettorazzi, J.F.; Müller-Santos, M.; Albrecht, L. Plasmodium vivax vaccine: What is the best way to go? Front Immunol 2022, 13, 910236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtamu, K.; Petros, B.; Yan, G. Plasmodium vivax: the potential obstacles it presents to malaria elimination and eradication. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines 2022, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajudeen, Y.A.; Oladipo, H.J.; Yusuff, S.I.; Abimbola, S.O.; Abdulkadir, M.; Oladunjoye, I.O.; Omotosho, A.O.; Egbewande, O.M.; Shittu, H.D.; Yusuf, R.O.; et al. A landscape review of malaria vaccine candidates in the pipeline. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines 2024, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.N.; Tolia, N. Structural vaccinology of malaria transmission-blocking vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2021, 20, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, C.T.H.; Cao, Y.; Clark, L.C.; Tripathi, A.K.; Zavala, F.; Dwivedi, G.; Knox, J.; Alameh, M.G.; Lin, P.J.C.; Tam, Y.K.; et al. mRNA-LNP expressing PfCSP and Pfs25 vaccine candidates targeting infection and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amimo, F. Leveraging malaria vaccines and mRNA technology to tackle the global inequity in pharmaceutical research and production towards disease elimination. Malar J 2024, 23, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musoke, D.; Atusingwize, E.; Namata, C.; Ndejjo, R.; Wanyenze, R.K.; Kamya, M.R. Integrated malaria prevention in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Malaria Journal 2023, 22, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Seidlein, L.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Jittamala, P.; Pongsuwan, P.; Chotivanich, K.; Tarning, J.; Hoglund, R.M.; Winterberg, M.; Mukaka, M.; Peerawaranun, P.; et al. Combining antimalarial drugs and vaccine for malaria elimination campaigns: a randomized safety and immunogenicity trial of RTS,S/AS01 administered with dihydroartemisinin, piperaquine, and primaquine in healthy Thai adult volunteers. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, P.E.; Gorres, J.P.; Healy, S.A.; Fried, M. Malaria vaccines: a new era of prevention and control. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sanz, M.; Berzosa, P.; Norman, F.F. Updates on Malaria Epidemiology and Prevention Strategies. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tine, R.; Herrera, S.; Badji, M.A.; Daniels, K.; Ndiaye, P.; Smith Gueye, C.; Tairou, F.; Slutsker, L.; Hwang, J.; Ansah, E.; et al. Defining operational research priorities to improve malaria control and elimination in sub-Saharan Africa: results from a country-driven research prioritization setting process. Malar J 2023, 22, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Malaria Programme operational strategy 2024-2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090149 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Ward, C.L.; Shaw, D.; Anane-Sarpong, E.; Sankoh, O.; Tanner, M.; Elger, B. The Ethics of Health Care Delivery in a Pediatric Malaria Vaccine Trial: The Perspectives of Stakeholders From Ghana and Tanzania. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2018, 13, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, C.; McKee, M.; Howard, N. The role of global health partnerships in vaccine equity: A scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health 2024, 4, e0002834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osoro, C.B.; Ochodo, E.; Kwambai, T.K.; Otieno, J.A.; Were, L.; Sagam, C.K.; Owino, E.J.; Kariuki, S.; Ter Kuile, F.O.; Hill, J. Policy uptake and implementation of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in sub-Saharan African countries: status 2 years following the WHO recommendation. BMJ Glob Health 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, C.E.; Schellenberg, D.; Vekemans, J.; Asturias, E.J.; Bejon, P.; Collins, K.A.; Crabb, B.S.; Herrera, S.; Laufer, M.; Rabinovich, N.R.; et al. Building momentum for malaria vaccine research and development: key considerations. Malaria Journal 2020, 19, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B. New tools for malaria control - using them wisely. J Infect 2017, 74 Suppl 1, S23–s26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangdi, K.; Banwell, C.; Gatton, M.L.; Kelly, G.C.; Namgay, R.; Clements, A.C. Malaria burden and costs of intensified control in Bhutan, 2006-14: an observational study and situation analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016, 4, e336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healer, J.; Cowman, A.F.; Kaslow, D.C.; Birkett, A.J. Vaccines to Accelerate Malaria Elimination and Eventual Eradication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, V.; Wangdi, K. Editorial: World Malaria Day 2023 - ending malaria transmission: reaching the last mile to zero malaria. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1433213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, A.; Mboussou, F.; Impouma, B.; Cabore, J.; Moeti, M.R. Introduction and rollout of malaria vaccines in Cameroon and Burkina Faso: early lessons learned. Lancet Glob Health 2024, 12, e740–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).