1. Introduction

The fungal sinusitis involving the sinonasal cavities can be classified broadly into invasive and non-invasive types. To diagnose the fungal sinusitis as invasive, it is important to establish the presence of fungal hyphae in deeper mucosa or submucosa or involving neurovascular bundle or cortical bone or in systemic circulation [

1]. The invasive type is again divided into three types, namely, i) acute invasive fungal sinusitis, ii) chronic invasive fungal sinusitis and iii) chronic granulomatous variants. Unlike the acute fulminant and chronic invasive type which is seen in immunosuppressed patients, the chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis (CGIFS) is seen in immunocompetent individuals [

2].

CGIFS is characterized by a granulomatous reaction which can lead to significant proptosis and craniofacial deformity if not detected earlier. CGIFS presents with non-specific symptoms such as headache, swelling in the maxillary area/infra orbital area, ocular symptoms such as pain around the eye, proptosis or swelling in extra conal region of eye ball. Because of these non-specific varied clinical presentations, delay in diagnosis is common [

3]. The disease can sometimes progress to focally expansive lesions resulting in pressure symptoms. The diagnosis is made with the help of histopathological and microbiological examination [

4]. Preoperatively imaging may show the characteristics features of fungal sinusitis such as hypo dense areas within a hyper dense sinus filling lesion, called as double density sign, or bone erosions, which may lead to involvement of pre maxillary soft tissues or extension of sinus pathology into pterygopalatine fossa. The differential diagnosis includes malignancy and other soft tissue tumors of maxilla [

5]. Management of CGIFS is still a topic of debate as no proper guidelines are available. Surgical debridement and systemic antifungals are the core stone modalities in the management of CGIFS [

6]. Here we report a case of a patient who presented with facial swelling.

2. Case Presentation

A 31 year old male, from a rural village with no known comorbidities, presented to the otorhinolaryngology outpatient department with complaints of right side cheek swelling of 18 months duration. He noticed gradual increase in size of the swelling over the past 6 months. Initially he consulted a nearby hospital and was treated for chronic rhino sinusitis. As the facial swelling gradually increased in spite of treatment he visited our hospital. On thorough history taking, he informed that the swelling was not associated with any pain, loosening of tooth, weight loss, bleeding through nose, nasal obstruction, visual disturbances, swelling in the neck or ear symptoms.

On clinical evaluation the swelling was soft to firm consistency of approximately 3*3cm, non-tender lying approximately 1 cm inferior to infraorbital margin, with ill-defined borders and without any signs of inflammation. Skin over the swelling was pinchable and no intra oral extension was seen. Normal sensations over the trigeminal nerve region bilaterally. On ophthalmology evaluation visual acuity was normal, no spontaneous or evoked nystagmus noted, and there was no restriction of extra ocular movements bilaterally.

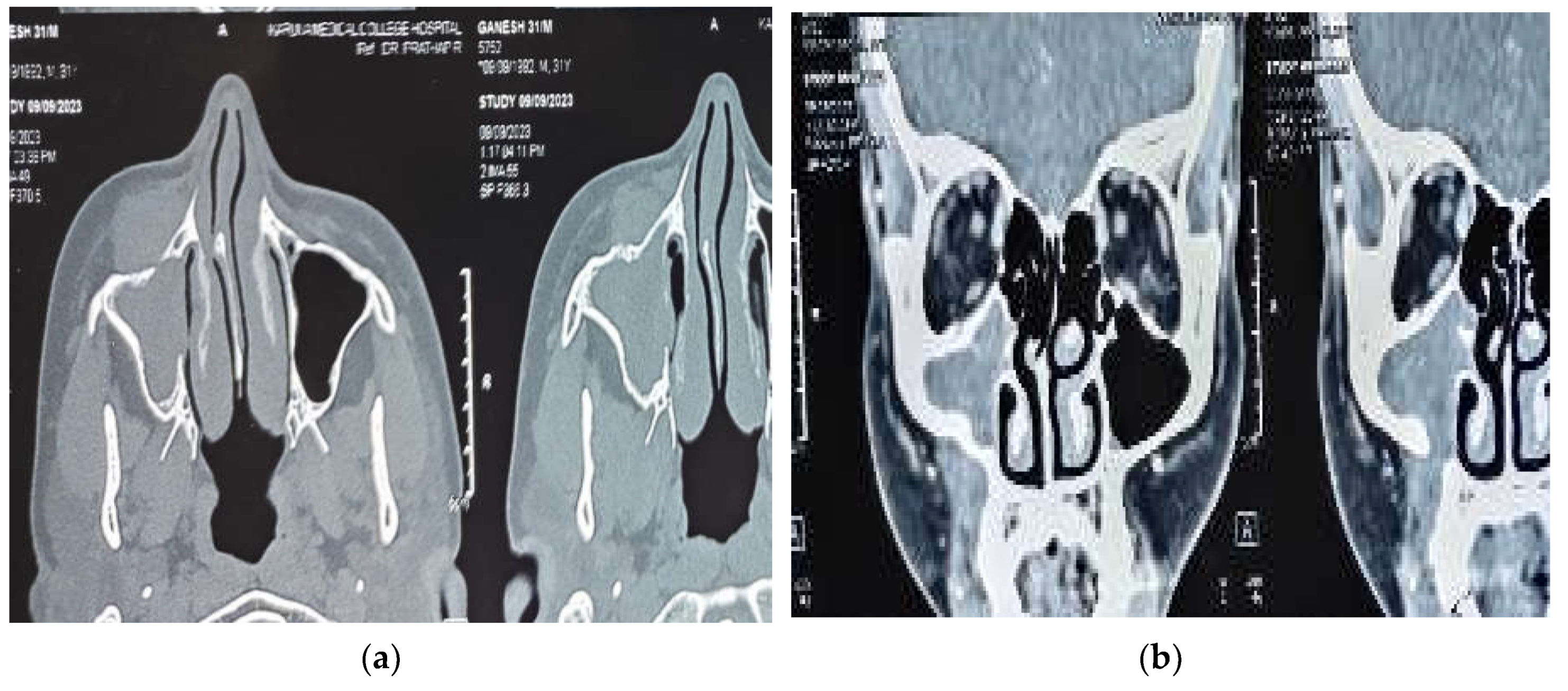

A diagnostic nasal endoscopy was performed and it showed deviation of the anterior nasal septum to right with a bony spur not touching the lateral wall. Non contrast computerized tomography of the nose and paranasal sinuses revealed partial opacification of the right maxillary sinus with partial erosion of the anterior maxillary wall. The lesion was found to be extending through a defect into the soft tissue over the premaxilla area without involving the subcutaneous fat planes. Post intravenous contrast administration, the lesion showed mild enhancement with bony scalloping and erosion of the right maxillary sinus and part of alveolar process of maxilla (

Figure 1 (a) and 1 (b) ). As there was no involvement of orbit or intracranial extension a magnetic resonance imaging was not advised.

The patient was counseled regarding the possible nature of the condition and also regarding the need of undergoing surgical procedure to reach a proper diagnosis. The case was presented in the institutional tumor board meeting and a consensus was reached regarding the treatment plan. An open medial maxillectomy was performed with complete removal of the tumor (

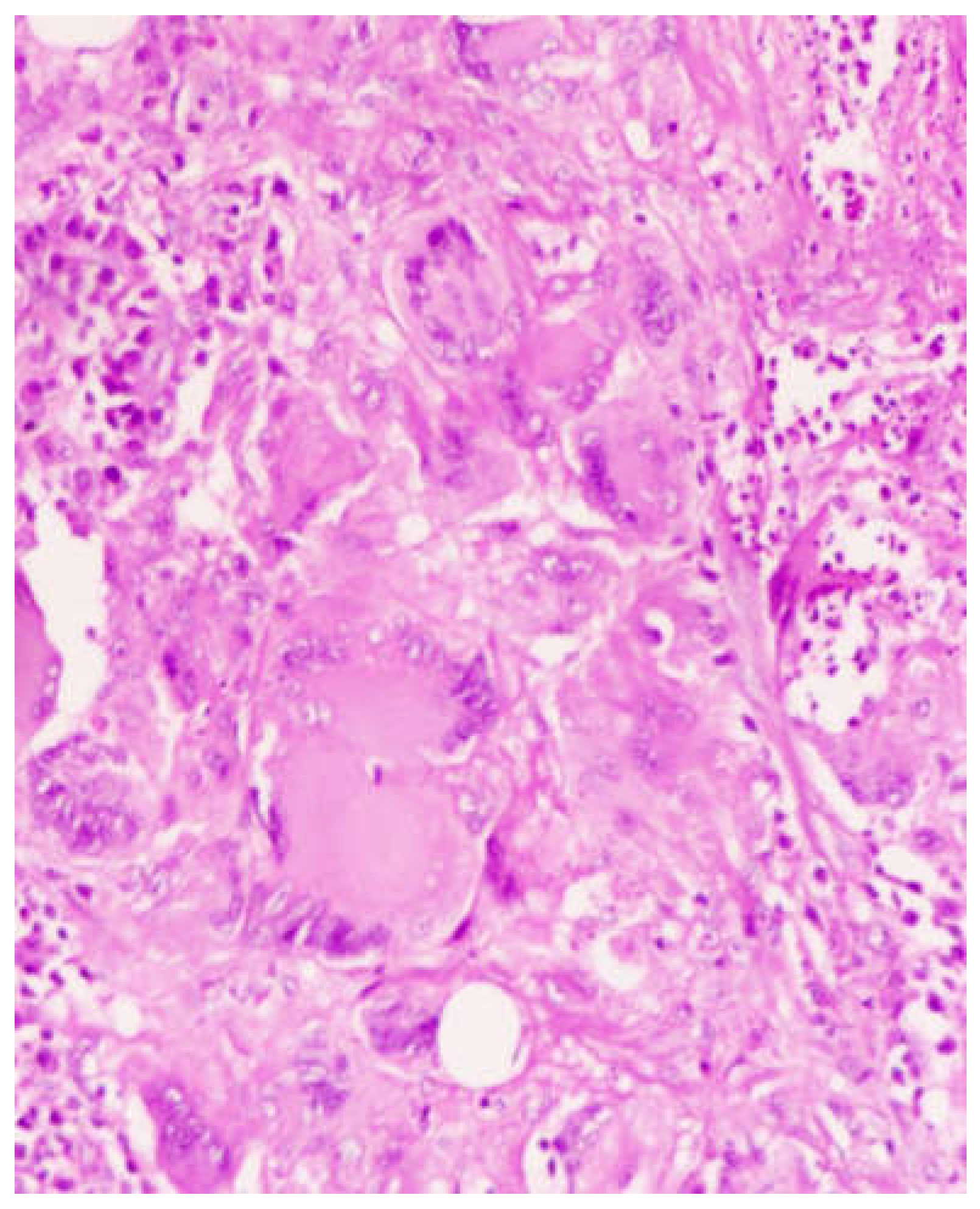

Figure 2). The histopathological examination showed numerous multinucleated giant cells in the background of chronic inflammation with signs of non caseating granulomatous changes (

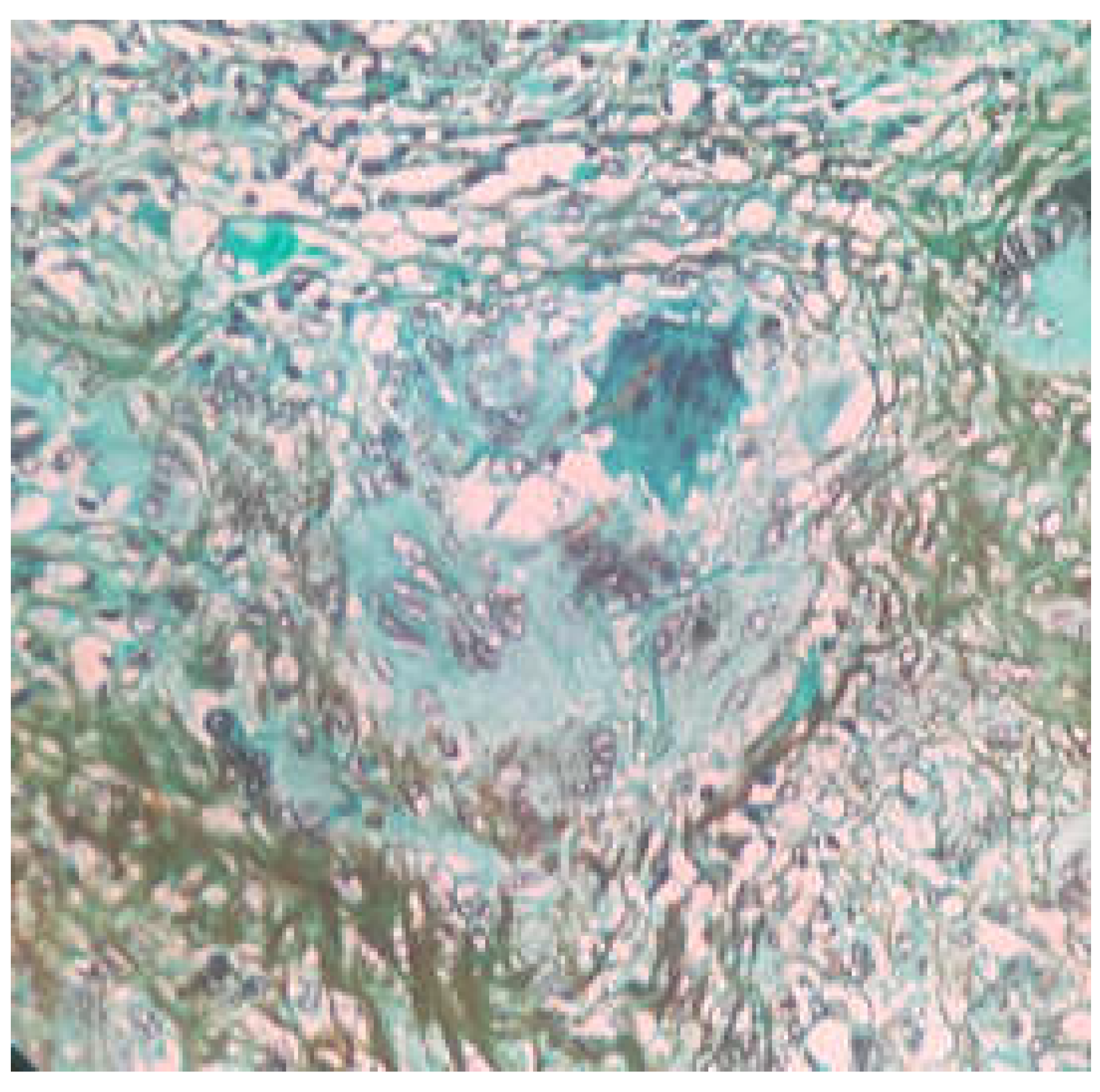

Figure 3). On Grocott’s Methanamine Silver staining (GMS staining) dark brown colored septate fungal hyphae was seen (

Figure 4). On fungal culture with malt extract agar as culture media, the presence of aspergillus flavus was confirmed. Cartridge based nucleic acid amplification tests for mycobacteria species showed a negative result. With the histopathological and microbiological evidences a diagnosis of CGIFS was made and the patient was put on voriconazole 200mg twice daily for 12 weeks under liver function monitoring fort nightly. Patient showed no signs of recurrence till three months of follow up.

3. Discussion

According to the various works by DeShazo et al, the fungal sinusitis can be classified into invasive and non-invasive with the former is again sub classified as acute fulminant, chronic and chronic granulomatous [

1,

7,

8]. When the duration of the disease is less than 4 weeks it is termed as acute and for duration of more than 4 weeks it is defined as chronic form [

9]. The invasiveness of the disease is strictly defined in terms of histopathological presence of fungal hyphae in sinonasal mucosa not limited to surface mucosa, submucosa or tissues beyond submucosa which includes neurovascular structures, bone, muscles, and orbit [

10].

The chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis also known as indolent fungal sinusitis and primary nasal granuloma is distinct from the other two types of invasive types. CGIFS is seen usually in immunocompetent individuals with a peculiar geographic distribution. The condition is more commonly reported in dry, humid tropical countries. Majority of reported cases are from Sudan, Western Asia, Pakistan and India. This can be attributed to the wide presence of aspergillus fungal species [

11].

The pathogenesis of CGIFS is different from chronic invasive fungal sinusitis (CIFS). The underlying immune mechanism associated with invasive fungal sinusitis is not well understood. Th-17 T cells which are a part of innate immune mechanisms against fungal pathogens are found to be more in CGIFS individuals. This increased Th 17 cell population may lead to an unchecked Th 1 response, which further results in chemo attraction of cells involved in chronic inflammation. This cascade ends with a cycle of chronic tissue inflammation with failure to effectively remove the fungal pathogen. Thus, in tissue specimen CIFS shows a similar picture that of chronic inflammation with abscess like reaction in the back ground of low grade mixed inflammatory cells. This nonspecific histopathology picture often fails the pathologist and the surgeon to alert the possibility of fungal etiology leading to delay in diagnosis and subsequent proper management [

12]. Most common differential diagnosis at this point are malignancy, an extensive Para sellar tumor, common granulomatous conditions which include tuberculosis, syphilis, rhinoscleroma and granulomatosis with polyangitis ( previously known as wegner’s granulomatosis) A strong suspicion of fungal pathology should be raised in clinical history of immunocompromised status with histological examination showing chronic inflammation changes with non caseating granulomas [

13].

The majority of the documented cases of CGIFS belong to the younger age group. In a case series of 10 cases reported by Asoegwu et al in Nigeria, the average age was 33.9 years [

14]. Similar age group was also seen in a series of 7 cases from Saudi Arabia [

15]. Other reported cases in the last 15 years are a 40 year old male in Nigeria and a 64 year old Type II Diabetes mellitus patient with SARS Cov 2 infection [

16]. The most common presenting symptom is proptosis followed by nasal mass, cheek swelling and CRS not responding to conventional treatments. The disease is locally aggressive with involvement of orbit, intracranial extension, or pterygopalatine fossa [

14,

15,

16]. Our case, a 31 year old male presented with a long standing cheek swelling, not responded to CRS management.

Radiological imaging gives hints which points towards the possibility of fungal etiology. Computed tomography is essential in identifying bone changes whereas MRI may give much more detailed information about soft tissue extensions. This is particularly of important in cases where orbit, sellar or intracranial extension is suspected. CT findings supporting the CFRS diagnosis are disease limited to few sinuses, bone erosion rather than necrosis or sequestrum formation and heterogeneous sinus mucosal thickening [

17]. Because of this bone erosion causing property disease extension to adjacent regions is not uncommon. 7 out of 10 patients of Asoegwu et al had orbital extension, with 5 patients having intracranial and one patient with pterygopalatine fossa extension [

14]. Similar aggressive nature of the disease was noted by Alarifi et al, where 5 out of 7 patients had orbital involvement, and two patients with intracranial extension [

15]. The SARS Cov 2 co-existed case reported by Gonzalez et al also had extension into orbit as intraconal abscess [

16]. However our patient had a localized involvement with minimal erosion of anterior maxillary wall and pre antral tissue infiltration without orbital involvement. This may be due to previous repeated treatments taken by the patient from outside where the underlying inflammation process is of less intensity. The bone erosion could be attributed to long standing pressure changes as no lytic or periosteitis changes where seen.

The treatment primarily focuses on removal or debulking the source of inflammation/infection [

18]. The open approach has an added advantage in extensive disease. Whenever possible, endoscopic resection or debulking is preferred considering post-operative morbidity associated with open approaches. In the present case report, during the pre-operative counselling, we explained about the need of shifting to an open approach in case of a failed endoscopic approach and patient requested to perform open medial maxillectomy without attempting an endoscopic approach. Intraoperatively the anterior wall of maxilla was eroded with the lesion involving the pre antral soft tissue. The orbital floor and posterior wall of maxilla found intact. Endoscopic approach was the preferred treatment choice wherever possible in the studies by Alarifi et al and Asoegwu et al [

14,

15].

Once the histopathological diagnosis is suspicious of fungal granulomatosis, it is essential to provide evidence of fungal elements. A preliminary diagnosis of fungus etiology can be obtained either by KOH mount or calcoflour staining [

19]. These tests are not useful in cases where fungal elements are sparse. In such a scenario either GMS stain or fungal culture helps in establishing the diagnosis of invasive mycosis. The GMS staining or culture has an added advantage of differentiating viable and non-viable fungi elements [

20]. This is of treatment importance as allergic fungal noninvasive variant is primarily because of non-viable fungi elements evoking an allergic response and treatment is corticosteroids in AFRS. At the same time use of steroid formulations can aggravate the disease in invasive fungal diseases.

The most common organism causing CGIFS is aspergillus especially Aspergillus flavus and other organisms include Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus Niger and candida species [

14,

15,

16,

21]. Once tissue diagnosis of invasive fungal sinusitis is reached, systemic anti-fungal therapy is recommended. The duration of therapy has not been clearly suggested or defined anywhere but literature evidence shows antifungal therapy of at least 3 months is required to prevent progression and recurrence [

22]. The choice of antifungal agent to be used is depends on patient factors and organism isolated. The various agents used in invasive type of fungal diseases are intravenous amphotericin B, Liposomal amphotericin B, the azole group comprising of itraconazole, voriconazole and posaconazole. Other newer agents such as Micafungin, anidulfungin also have shown response to aspergillosis. According to Patterson et al and Walsh et al, whenever the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis is made, the preferred drug of choice should be voriconazole [

23,

24]. In our patient as the disease was localized and less evidence of invasive nature we opted for oral voriconazole for a period of three months. The duration of therapy can be continued till clinical resolution of the symptoms or till a negative fungal culture is obtained. Such long term treatment has the risks of hepatic or kidney damage as most of the antifungals are either hepatotoxic or nephrotoxic.

Lack of a proper treatment algorithm makes the clinicians in managing this condition. A classification system proposed by Rupah et al incorporating clinical and radiological parameters is found to be helpful in formulating a treatment plan. They categorized the disease into three stages. Stage 1 where disease is confined to nasal cavity and paranasal sinus and can be resected completely by endoscopic approach alone. Extension to orbit, palate or oral cavity is defined as stage 2 and a combined open and endoscopic approach is needed for complete clearance. Stage 3 is when disease spreads to intracranially either intradural or extradural, pterygopalatine fossa, cavernous sinus or periorbital tissues. In stage 3 more destructive procedures such as craniotomy, craniofacial resection or midfacial degloving is needed [

25].

Although rare, CGIFS progressing to or co existing with other fungal variants also should be considered. Alarifi et al reported a case of CGIFS on post-operative treatment becoming a case of AFRS [

15]. This may be due to inadequate surgical clearance initiating allergic reaction around a focus of non-viable fungal element.

4. Conclusions

Differentiating fungal granulomatosis from other granulomatosis conditions is of paramount of importance in providing disease specific management. Granulomatosis with chronic inflammatory finding in an immunocompetent patient should raise the suspicion of CGIFS and a fungal culture or stain has to be advised. The management includes complete resection whenever possible followed by long term systemic antifungal therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization SK and VA.; methodology SK,VA and SA ,data curation, SK VA,SA and RJ, writing—original draft preparation, SK,VA and RJ ; writing—review and editing, SA and PR.; supervision, PR;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and as per the Institutional Ethical Committee rules, case reports has been waived off committee Approval for publications. According to Institution Human Ethical Committee for publishing case reports patient consent should be obtained in the language known to the patient

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- DeShazo, R.D.; O’Brien, M.; Chapin, K.; Sato-Aguilar, M.; Gardner, L.; Swain, R.E. A new classification and criteria for invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery 1997, 123, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahethi, R.; Talmor, G.; Choudhary, H.; Lemdani, M.; Singh, P.; Patel, R.; et al. Chronic invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis and Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: A systemic review of symptomatology and Outcomes. American Journal of Otolaryngology 2024, 45, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaji-Kanayama, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Yasuda, M.; Sakiyama, E.; Shimura, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; et al. Chronic Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis with Atypical Clinical Presentation in an Immunocompromised Patient. Infect Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3225–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jang, H.U.; Jung, Y.Y.; Kim, J.S. Granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis extending into the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital floor: A case report. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2012, 1, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, H.T.; Kaplan, E.; Çoraplı, M. Acute and chronic invasive fungal sinusitis and imaging features: A review. J Surg Med. 2021, 5, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Yoon, T.M.; Lee, J.K.; Joo, Y.E.; Park, K.H.; Lim, S.C. Invasive fungal sinusitis of the sphenoid sinus. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 7, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, R.D.; Swain, R.E. Diagnostic criteria for allergic fungal sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995, 96, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, R.D.; O’Brien, M.; Chapin, K. Criteria for diagnosis of sinus mycetoma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997, 99, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J. Definitios of fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000, 33, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, R.D. Syndromes of invasive fungal sinusitis. Med Mycol. 2009, 47 (suppl 1), 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, A.A.; Enani, M.; Mahasin, Z.; Al-Omran, K. Chronic invasive aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses in immunocompetent hosts from Saudi Arabia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, W.; Doffinger, R.; Shelton, F.; et al. A novel insight into the immunologic basis of chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2016, 7, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montone, K.T. Pathology of fungal rhinosinusitis: a review. Head and Neck Pathology 2016, 10, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asoegwu, C.N.; Oladele, R.O.; Kanu, O.O.; Nwawolo, C.C. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in Nigeria: challenges of management. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020, 6, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, I.; Alsaleh, S.; Alqaryan, S.; et al. Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: A Case Series and Literature Review. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2021, 100 (Suppl. 5), 720S–727S. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño-Gonzalez, J.L.; Santos-Santillana, K.M.; Maldonado-Chapa, F.; Morales-Del Angel, J.A.; Gomez-Castillo, P.; Cortes-Ponce, J.R. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021, 72, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Rasheed Rasheed, A.; Awan, M.R.; Hameed, A. Aspergillus Infection of Paranasal Sinuses. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2010, 5, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halderman, A.; Shrestha, R.; Sindwani, R. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis: an evolving approach to management. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, B.; Walsh, T.J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Stevens, D.A.; Edwards, J.E.; Calandra, T.; et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Adhya, A.K. Grocott Methenamine Silver Positivity in Neutrophils. J Cytol. 2019, 36, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Chakrabarti, A. Epidemiology and medical mycology of fungal rhinosinusitis. Otorhinolaryngol Clin Int J. 2009, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, V.; Peter, J.; Michael, J.S.; Thomas, M.; Irodi, A.; Rajshekhar, V. Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in Patients With Immunocompetence: A Review. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

- Patterson, T.F.; Thompson, G.R.; Denning, D.W.; Fishman, J.A.; Hadley, S.; Herbrecht, R.; et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016, 63, e1–e60. 63.

- Walsh, T.J.; Anaissie, E.J.; Denning, D.W.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupa, V.; Maheswaran, S.; Ebenezer, J.; Mathews, S.S. Current therapeutic protocols for chronic granulomatous fungal sinusitis. Rhinology. 2015, 53, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).