Submitted:

26 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical data and sample collection

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

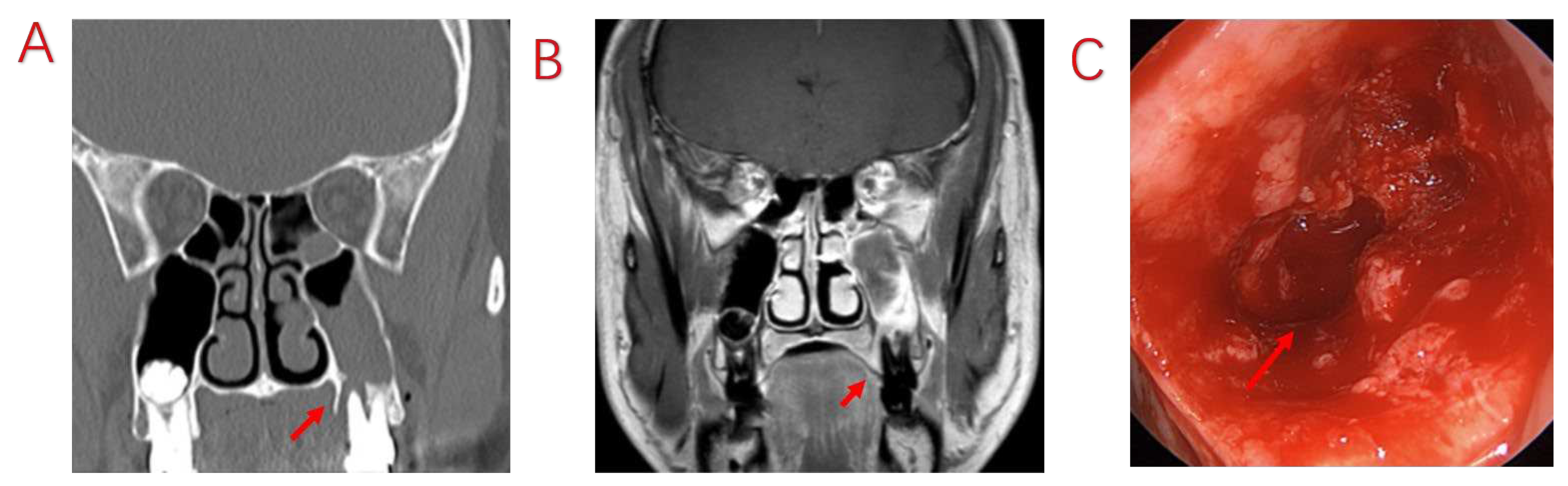

2.3. Diagnostic criteria for odontogenic lesions

- Apical periodontitis (AP): Vitality of dental pulp (-); CAL (-); PPD (≤3 mm); and radiological bone loss (-)[18].

- Periodontitis (PE): Vitality of dental pulp (+); interdental CAL detectable at ≥2 nonadjacent teeth; buccal or oral CAL ≥3 mm with pocketing ≥3 mm detectable at ≥2 teeth, although the observed CAL cannot be ascribed to non-PE-related causes, such as 1) gingival recession of traumatic origin, 2) dental caries extending in the cervical area of the tooth, 3) CAL on the distal aspect of a second molar associated with malposition or extraction of a third molar, 4) endodontic lesion draining through the marginal periodontium, and 5) vertical root fracture[17].

- Temporary oroantral communications: Oral maxillary sinus communication after tooth extraction, mucosal healing of the oral fistula, and bone loss at the base of the maxillary sinus[19].

- Permanent oroantral fistulas: Oral maxillary sinus communication after tooth extraction, unhealed intraoral fistula, and oral and maxillary sinus communication[19].

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ODS patients

3.2. Review of surgical data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nurchis M C, Pascucci D, Lopez M A, et al. Epidemiology of odontogenic sinusitis: an old, underestimated disease, even today. A narrative literature review. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2020, 34, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Allevi F, Fadda G L, Rosso C, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2021, 35, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens W J, Lund V J, Hopkins C, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58, 1–464. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K L, Nichols B G, Poetker D M, et al. Odontogenic sinusitis: a case series studying diagnosis and management. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2015, 5, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig J R, Poetker D M, Aksoy U, et al. Diagnosing odontogenic sinusitis: An international multidisciplinary consensus statement. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2021, 11, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld R M, Piccirillo J F, Chandrasekhar S S, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015, 152, S1–S39. [Google Scholar]

- Nair A K, Jose M, Sreela L S, et al. Prevalence and pattern of proximity of maxillary posterior teeth to maxillary sinus with mucosal thickening: A cone beam computed tomography based retrospective study. Ann Afr Med 2023, 22, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penarrocha-Oltra S, Soto-Penaloza D, Bagan-Debon L, et al. Association between maxillary sinus pathology and odontogenic lesions in patients evaluated by cone beam computed tomography. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2020, 25, e34–e48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, He Z, Tian H. Association between periodontal status and degree of maxillary sinus mucosal thickening: a retrospective CBCT study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 392. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy U, Orhan K. Association between odontogenic conditions and maxillary sinus mucosal thickening: a retrospective CBCT study. Clin Oral Investig 2019, 23, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhar R, Alkhames H M, Ahmed M A, et al. CBCT Evaluation of Periapical Pathologies in Maxillary Posterior Teeth and Their Relationship with Maxillary Sinus Mucosal Thickening. Healthcare 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Alghofaily M, Alsufyani N, Althumairy R I, et al. Odontogenic Factors Associated with Maxillary Sinus Schneiderian Membrane Thickness and their Relationship to Chronic Sinonasal Symptoms: An Ambispective Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Turfe Z, Ahmad A, Peterson E I, et al. Odontogenic sinusitis is a common cause of unilateral sinus disease with maxillary sinus opacification. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2019, 9, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal V K, Ahmad A, Turfe Z, et al. Predicting Odontogenic Sinusitis in Unilateral Sinus Disease: A Prospective, Multivariate Analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2021, 35, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaltis A J, Li G, Vaezeafshar R, et al. Modification of the Lund-Kennedy endoscopic scoring system improves its reliability and correlation with patient-reported outcome measures. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun P, Guo Z, Guo D, et al. The Microbiota Profile Analysis of Combined Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions Using 16S rRNA Next-Generation Sequencing. J Immunol Res 2021, 2021, 2490064. [Google Scholar]

- Papapanou P N, Sanz M, Buduneli N, et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, L. [Problem solving in endodontic diseases: V. Correlation of clinical diagnosis, prognosis and histopathologic signs of apical periodontitis (I)]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010, 45, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bilginaylar, K. The Use of Platelet-Rich Fibrin for Immediate Closure of Acute Oroantral Communications: An Alternative Approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018, 76, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Zheng M, Zhao Y, et al. Bacterial diversity and community characteristics of the sinus and dental regions in adults with odontogenic sinusitis. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Craig J, R. Odontogenic sinusitis: A state-of-the-art review. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2022, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino L, Pierri M, Iafrati F, et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis from Classical Complications and Its Treatment: Our Experience. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Shanti R M, Alawi F, Lee S M, et al. Multidisciplinary approaches to odontogenic lesions. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020, 28, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig J R, Tataryn R W, Aghaloo T L, et al. Management of odontogenic sinusitis: multidisciplinary consensus statement. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2020, 10, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas A, Weiss C, Ebeling M, et al. Factors Influencing Recurrence after Surgical Treatment of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis: An Analysis from the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Point of View. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera D, Retamal-Valdes B, Alonso B, et al. Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. J Periodontol 2018, 89, S85–S102. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Symptomatic Patients with ODS (n=103) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 45.87±12.79 |

| Male sex (n, %) | 63 (61.2%) |

| Disease duration (mean±SD, months) | 9.87±10.57 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |

| Foul nasal odor | 84 (81.6%) |

| Nasal obstruction | 60 (58.3%) |

| Nasal discharge (anterior/posterior nasal drip) | 87 (84.5%) |

| Facial pain/pressure | 63 (61.2%) |

| Reduction or loss of smell | 14 (13.6%) |

| Sinuses involved (n, %) | |

| Maxillary sinus | 103 (100.0%) |

| Ethmoid sinus | 80 (77.7%) |

| Frontal sinus | 41 (39.8%) |

| Sphenoid sinus | 7 (6.8%) |

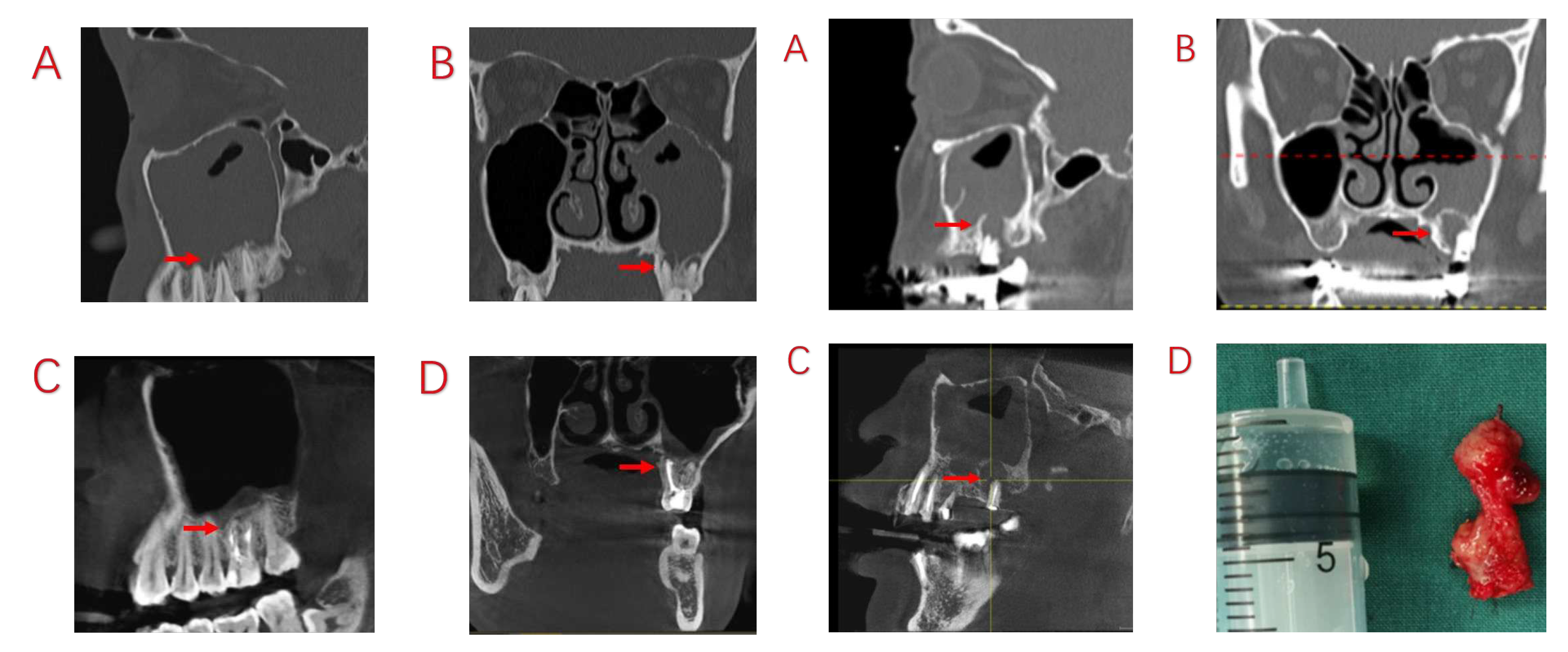

| Odontogenic causes (n, %) | |

| AP | 33 (32.0%) |

| EPL | 51 (49.5%) |

| PE | 9 (8.7%) |

| Oroantral communications and fistulas (temporary) | 5 (4.8%) |

| Oroantral communications and fistulas (persistent) | 4 (3.9%) |

| Postoperative dental implants | 1 (1.0%) |

| Variables | AP (n=33) | EPL (n=51) | PE (n=9) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 40.00±12.16 | 48.92±12.08 | 50.78±6.82 | 0.002 a |

| Male sex (n, %) | 14 (42.4%) | 36 (70.6%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.036 b |

| Course of disease (mean±SD, months) | 10.42±11.35 | 10.23±11.14 | 11.11±9.21 | 0.975 a |

| Symptoms (n, %) | ||||

| Foul nasal odor | 27 (81.8%) | 40 (78.4%) | 9 (100.0%) | 0.304 b |

| Nasal obstruction | 20 (60.6%) | 30 (58.8%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0.905 b |

| nasal drip | 28 (84.8%) | 46 (90.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | 0.427 c |

| Facial pain/pressure | 21 (63.6%) | 30 (58.8%) | 7 (77.8%) | 0.547 b |

| Reduction or loss of smell | 5 (15.2%) | 8 (15.7%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1.000 c |

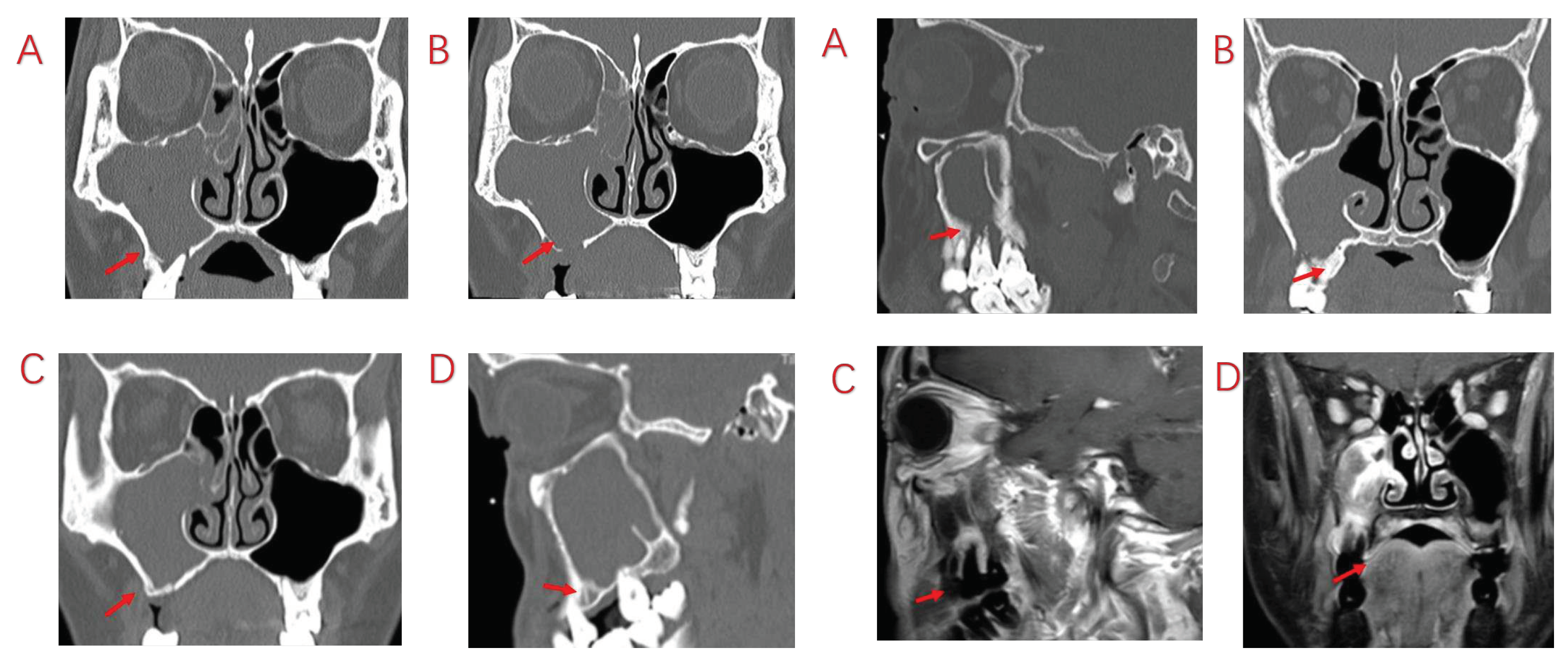

| Involving sinuses (n, %) | ||||

| Maxillary sinus | 33 (100.0%) | 51 (100.0%) | 9 (100.0%) | - |

| Ethmoid sinus | 30 (90.9%) | 37 (72.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.037 b |

| Frontal sinus | 17 (51.5%) | 19 (37.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.077 b |

| Sphenoid sinus | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (5.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.678 c |

| Bone penetration of MSF | 15 (45.5%) | 44 (86.3%) | 5 (55.6%) | <0.001b |

| Symptoms and Nasal Endoscope Finding (n=103) | Pre-Operation | Post-Operation | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Foul nasal odor | 84 (81.6%) | 0(0%) | <0.001 |

| Nasal obstruction | 60 (58.3%) | 3(2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Nasal discharge | 87 (84.5%) | 6(5.8%) | <0.001 |

| Facial pain/pressure | 63 (61.2%) | 0(0%) | <0.001 |

| Nasal endoscopy finding | |||

| Edema | |||

| 0: absent | 11 (10.7%) | 86 (83.5%) | <0.001 |

| 1: mild | 43 (41.7%) | 12 (11.6%) | <0.001 |

| 2: severe | 49 (47.6%) | 5 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Polyps | |||

| 0: no polyps | 69 (67.0%) | 103 (100%) | <0.001 |

| 1: polyps in middle meatus only | 19 (18.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| 2: beyond middle meatus | 15 (14.6%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Discharge | |||

| 0: no discharge | 9 (8.7%) | 92 (89.3%) | <0.001 |

| 1: clear, thin discharge | 5 (4.9%) | 8 (7.8%) | 0.39 |

| 2: thick, purulent discharge | 89 (86.4%) | 3 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).