1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the global economy, energy demand continues to soar. The over-reliance on and consumption of traditional fossil fuels not only accelerates the depletion of resources but also brings about serious environmental issues. Faced with the increasingly severe energy crisis and environmental pollution, the development of clean, sustainable energy technology has become a global focus. Hydrogen energy, as a clean, efficient, and renewable energy carrier, is of great significance for promoting the transformation of energy structures and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Methane, as the main component of natural gas, is a rich hydrocarbon resource. Catalytic methane decomposition for hydrogen production (CMD) is considered a promising hydrogen production process due to its simple process, easy separation of products, and no COx production. However, the C-H bond in methane molecules is very stable and difficult to activate and decompose. Therefore, developing efficient catalysts to promote the catalytic decomposition reaction of methane is key to the commercial application of this technology.Nickel-based catalysts have been widely used in the dehydrogenation or hydrogenation reactions of hydrocarbons due to their low cost, environmental friendliness, and superior catalytic performance. However, pure nickel catalysts are prone to sintering and coking at high temperatures, leading to a rapid decline in catalytic activity, which limits their industrial application in methane catalytic decomposition. To address this issue, researchers have improved the performance of catalysts by controlling preparation methods, optimizing reaction processes, and adding metal dopants, aiming to synthesize low-cost, high-activity methane decomposition catalysts for hydrogen production.

Vanadium, as an important metal element, has multiple oxidation states and good catalytic activity. The introduction of vanadium can not only improve the conductivity and electron transfer capability of the catalyst, enrich the number of active sites, but also enhance the catalytic performance by changing the crystal structure of the catalyst. In addition, doping vanadium can affect the interaction between the metal and the support, thereby suppressing the agglomeration and sintering of metal particles during the reaction process, and improving the thermal stability and service life of the catalyst.This study used commercial nano titanium dioxide (TiO2) as a carrier to prepare Ni/TiO2 catalysts by the impregnation method and systematically studied the effects of calcination temperature, metal loading, and reaction temperature on the performance of methane catalytic decomposition. At the same time, by introducing vanadium carbide (VC) as a dopant into the Ni/TiO2 catalyst, a one-step method was used to prepare Ni-VC/TiO2 composite catalysts, and the effects of VC content and reaction temperature on the catalyst structure and methane decomposition performance were investigated. In addition, using titanium tetraethoxide (TEOS) as a titanium source, mesoporous nano titanium dioxide particles (MSN) with high specific surface area and large pore volume were synthesized by the template method, and metal Ni was loaded to further study the effects of metal loading and reaction temperature on the performance of the catalyst.

The findings of this study provide important theoretical basis and technical support for the design and preparation of methane catalytic decomposition catalysts for hydrogen production, which has significant scientific significance and application value for promoting the commercial development of hydrogen energy.

Experimental Section

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

A certain amount of nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O) is dissolved in 25 milliliters of water. Then, a certain amount of vanadium carbide (VC) and 2 grams of nanometer titanium dioxide (TiO2) are weighed and slowly added to the above solution. At room temperature, the solution is stirred for 24 hours using a magnetic stirrer for impregnation. Afterward, the prepared solution is placed in a rotary evaporator to evaporate the solvent, and then the resulting solution is transferred to an oven for drying. The dried sample is ground into a powder and collected. These uniformly mixed powder samples are transferred to a ceramic boat and placed in the temperature-controlled area of a carbonization furnace. Through this process, we ultimately obtained a catalyst named nNi-xVC/TiO2, where n and x represent the mass percentage of nickel atoms and vanadium carbide to titanium dioxide before mixing, respectively.

2.2. Characterization Methods

A physical adsorption apparatus model JW-BK200A is used to perform adsorption-desorption experiments at a nitrogen environment of 77 K to evaluate the structural characteristics of the samples. Before the adsorption experiment, the samples are pretreated under vacuum at 300 °C for 3 hours to remove adsorbed gases and moisture from the samples. Then, the specific surface area and pore size distribution of the samples are calculated using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method and the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method, respectively. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples are obtained using a D/MAX-2400 X-ray diffractometer under Cu Kα radiation conditions of 30 kV and 30 mA. Hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) analysis of the catalyst is conducted using a PCA-1200 chemical adsorption analyzer. Finally, the morphology and structure of the samples after the methane catalytic cracking reaction are analyzed using a Quanta450 scanning electron microscope (SEM) and a JEM-2000EX transmission electron microscope (TEM) from FEI Company, USA.

2.3. Methane Catalytic Cracking Experiment

The methane catalytic cracking experiment was carried out in an atmospheric pressure fixed-bed reactor with a diameter of 8 millimeters. First, 0.2 grams of catalyst were placed in the temperature-controlled zone of the reactor. The reactor was heated to the set reaction temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere (40 mL/min), and then the gas was switched to a mixture of 10 mL/min methane and 40 mL/min nitrogen. After the reaction was stabilized for 5−10 minutes, the products were collected and analyzed for their composition online using a GC7890II gas chromatograph. The performance of the catalyst was evaluated based on the methane conversion rate and the carbon yield, with the calculation formulas as follows:

Methane Conversion Rate:

CCH4=(FCH4,in−FCH4,out)/FCH4,in×100%

Carbon Yield:

Carbon yield (gC/gNi) = Mass of coke deposited/ Mass of metal in the catalyst × 100%

2. Study on the Catalytic Cracking Behavior of Methane Over Ni-VC/TiO2 Catalyst

3.1. The Impact of VC Content on the Catalyst Structure and Methane Cracking

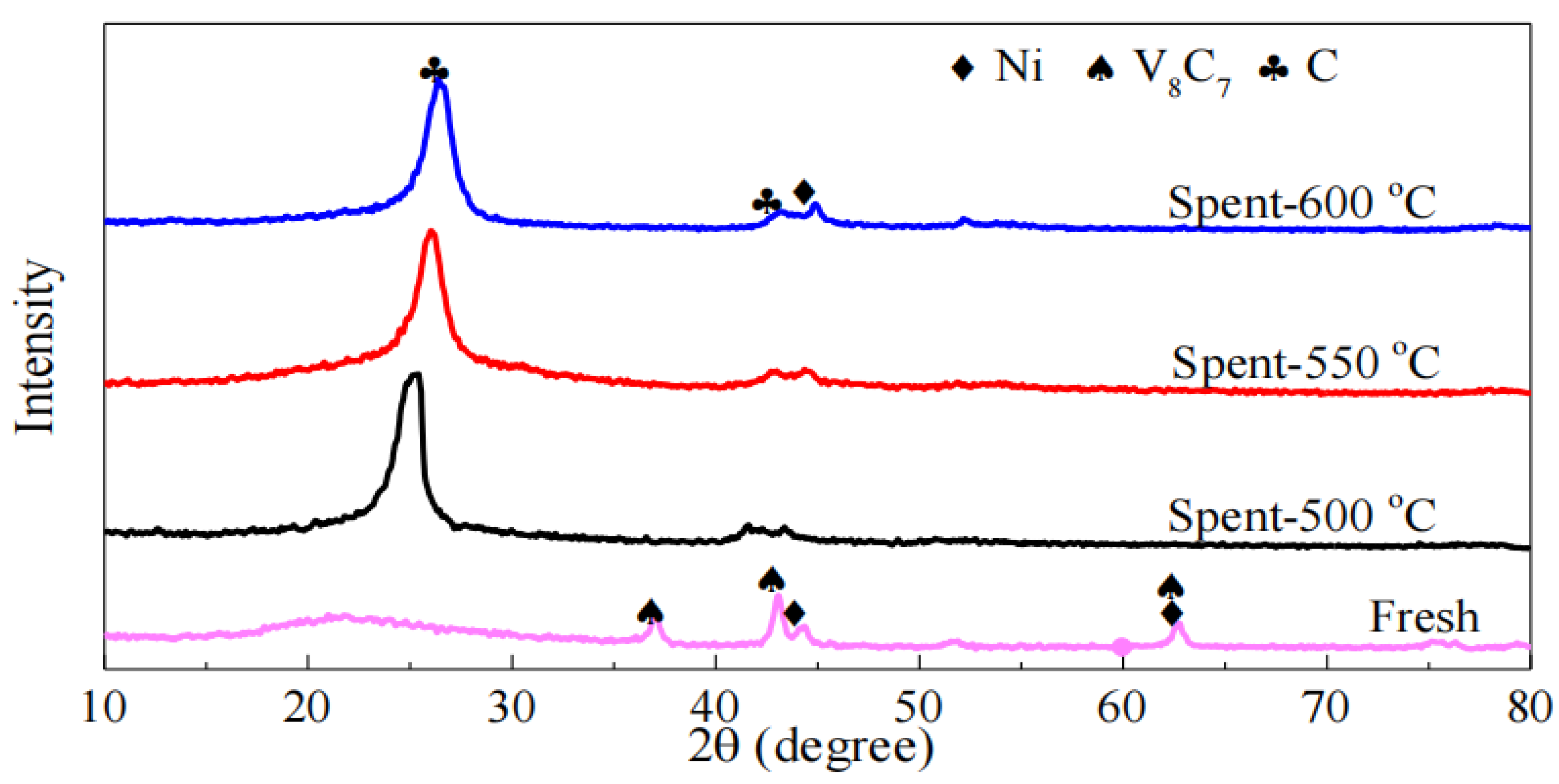

Performance In the catalytic process of methane cracking for hydrogen production, the efficiency of the catalyst is significantly affected by the crystallite size of the metal particles; the larger the crystallite size, the faster the deactivation rate of the catalyst. Using the Scherrer equation, the average size of nickel (Ni) particles before and after the reaction for 10Ni-xVC/TiO2 catalysts with different loadings of vanadium carbide (VC) was calculated, and the relevant results are listed in

Table 1. It was observed that with the increase in VC content, the size of Ni particles in the catalyst increased both before and after the reaction. This phenomenon may be due to the spatial constraints of the carrier leading to a reduction in the dispersion of the crystallites.

Additionally, in the process of catalytic methane cracking for hydrogen production, the optimal metal particle size for nickel-based catalysts is 23nm, which coincides with the nickel particle size of the 10Ni-5VC/TiO2 catalyst in this study. Compared with the catalyst in its initial state, the Ni/TiO2 catalyst only saw a 0.1nm increase in nickel crystallite size after 200 minutes of reaction. However, within a reaction time of 450 minutes, the nickel crystallite size of the 10Ni-5VC/TiO2 catalyst only slightly increased from 23.5nm to 24.1nm, showing the smallest crystallite growth in vanadium-containing catalysts. This indicates that an appropriate amount of VC doping can alter the interaction between the metal and the support, affecting the agglomeration mechanism of nickel crystallites, thereby effectively inhibiting the growth of nickel microcrystals.

Table 2 presents the structural characteristics of catalysts with different VC contents. The data from the table show that as the VC content increases, the specific surface area and pore volume of the 10Ni-xVC/TiO2 (x=1, 3, 5, 10) series of catalysts are significantly reduced. Compared with the 10Ni/TiO2 catalyst without VC doping, the addition of VC resulted in a decrease in the specific surface area of the prepared catalyst, but an increase in pore volume and pore size. The reasons for this phenomenon may include: on one hand, the loading of the metal active components on the surface of the carrier or the blockage within the pores, leading to a reduction in surface area; on the other hand, the reduction reaction between nickel oxides and vanadium carbide may have disrupted the skeleton structure of the carrier material, causing small particles to aggregate and form a porous structure with larger pore volume and pore size.

3.3. Catalysts Regeneration

Based on the previous findings, under the reaction conditions of 550°C, 30Ni-VC/TiO2 exhibited relatively good reactivity and stability. The lower reaction temperature is beneficial for the growth of filamentous carbon, which can yield higher rates of hydrogen production and filamentous carbon recovery. However, during the reaction process, the carbon formed covers the active centers, leading to catalyst deactivation. To explore the regeneration capability of the post-reaction catalyst, the 30Ni-VC/TiO2 was chosen as the subject for regeneration studies. The regeneration steps are as follows:

Using CO2 as an activating agent, CO2 is introduced into a fixed-bed reactor at atmospheric pressure and 600°C. The composition of the regenerated gas is monitored online by gas chromatography until no CO is produced. The CO2 valve is then closed, and the reactor is purged with nitrogen until the temperature drops to 550°C. The methane valve is then opened to conduct the methane cracking experiment again. The regeneration cycles are repeated until the catalyst is completely deactivated.

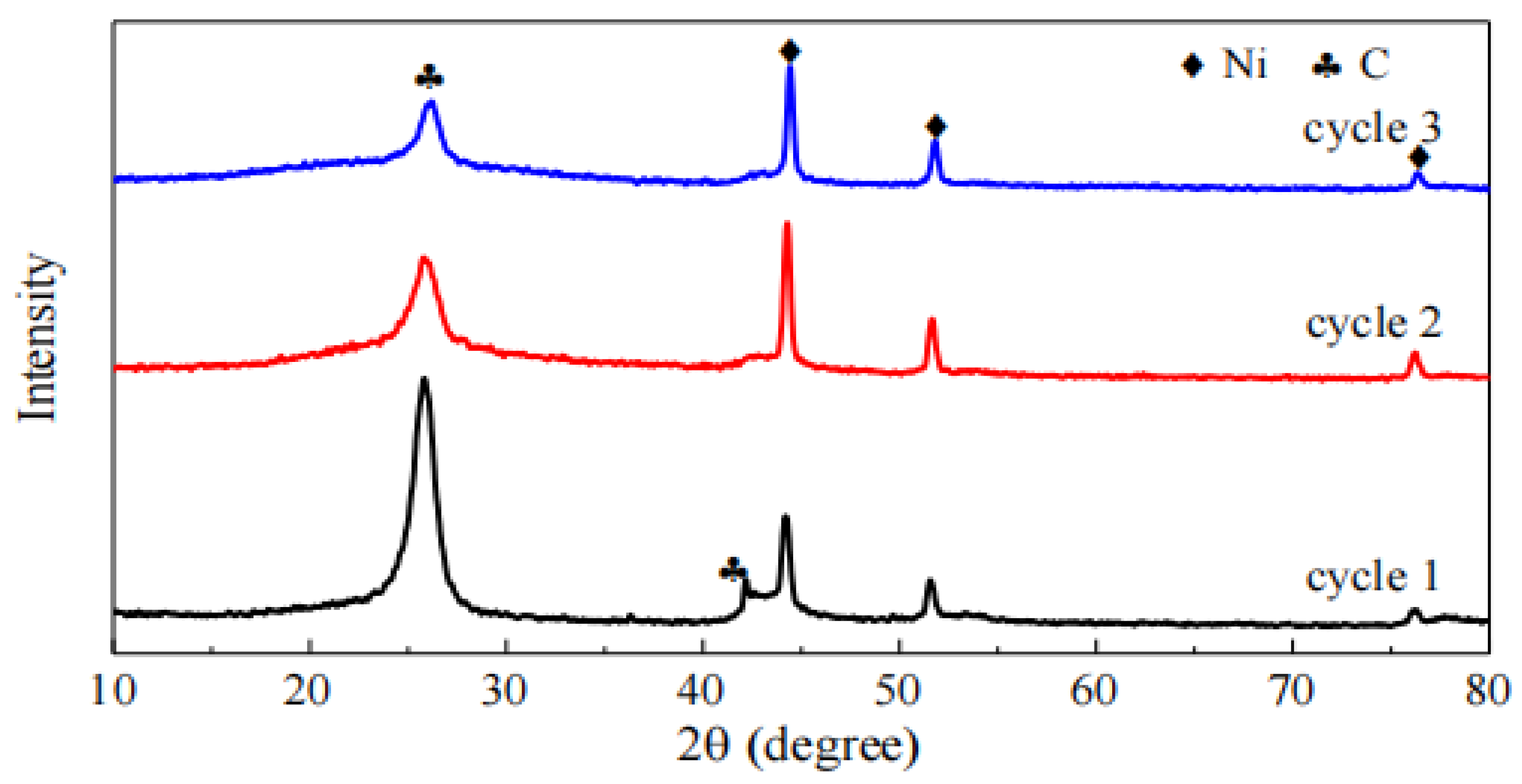

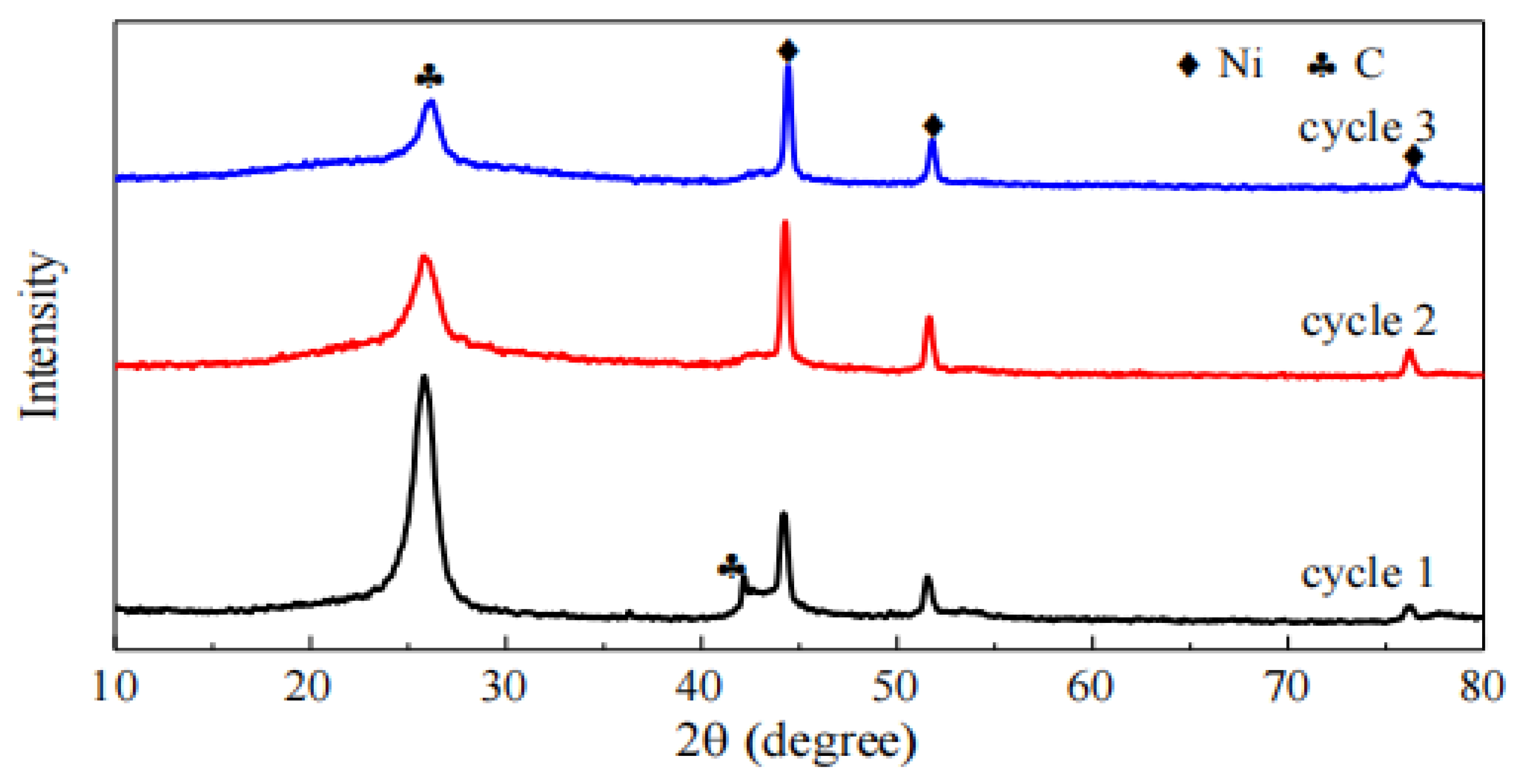

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of the 30Ni/TiO2 catalyst after different cycles of regeneration reactions. The diffraction peaks at 2θ of 26.4° and 43.5° are attributed to the C(002) and C(101) crystal planes, respectively, confirming the formation of coke during the methane cracking reaction. Comparisons reveal that the intensity of the Ni diffraction peaks increases after different cycles of reactions, indicating an enlargement of Ni crystallites. For the carbon diffraction peaks, their intensity gradually decreases, which is consistent with the results of the methane catalytic cracking experiments. Using the Scherrer equation, the average particle sizes of nickel in the catalyst after three cycles were calculated to be 20.0 nm, 22.3 nm, and 23.1 nm, respectively. This increase in Ni crystallite size may be one of the reasons for the reduced reactivity.

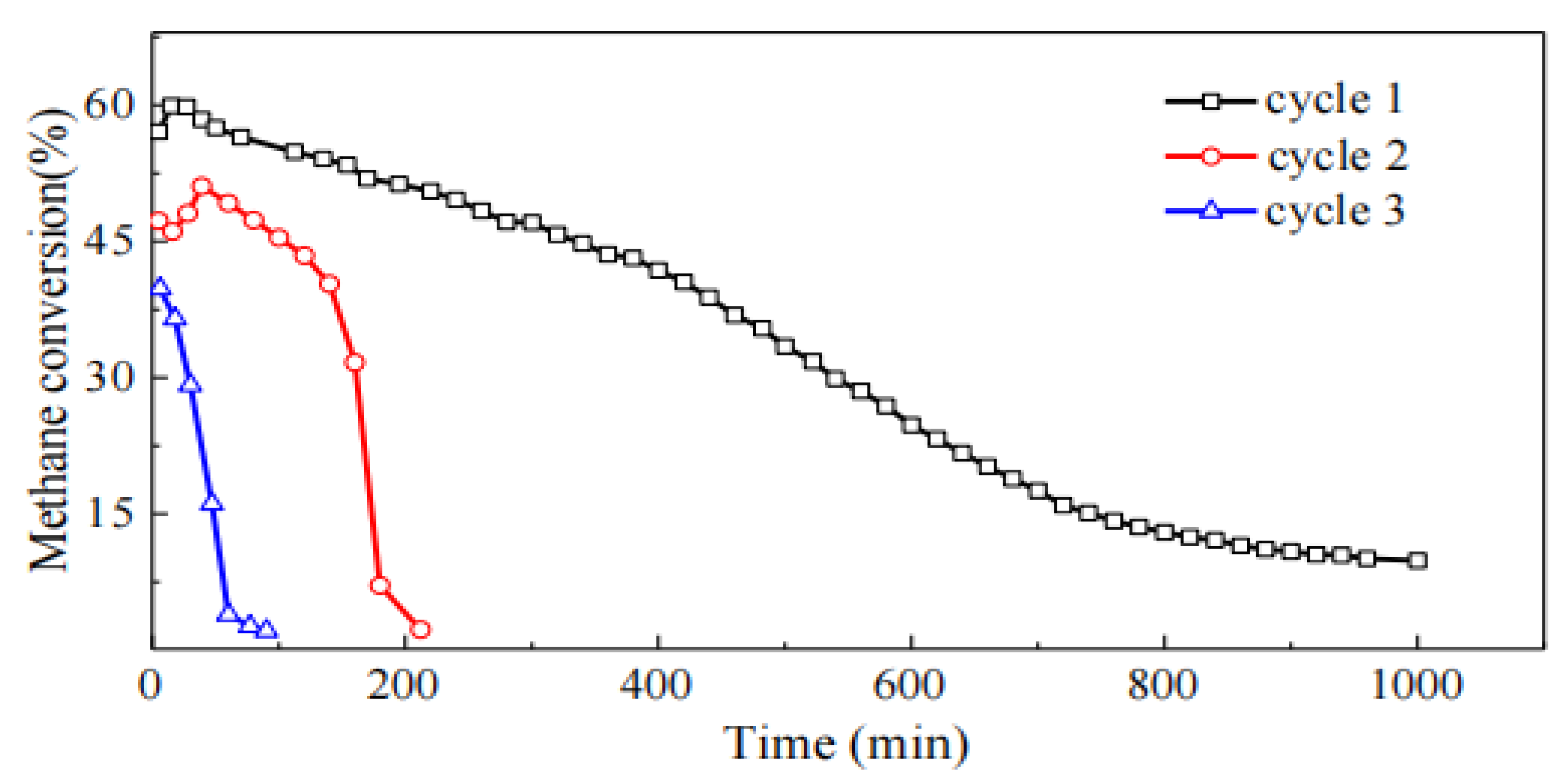

As can be seen from

Figure 5, although the regeneration process can restore the reactivity of the catalyst, with the increase in the number of cracking cycles, the methane conversion rate and reaction stability of the catalyst show a clear trend of decline. This may be attributed to the regeneration experiment conducted on the catalyst at 600°C, which causes sintering of the Ni particles, leading to changes in the catalyst's structure and performance.

Using SEM for surface morphology analysis of the post-reaction catalyst, it was observed that after three regeneration cycles, the catalyst surface was covered with interwoven filamentous carbon. The formation of this filamentous carbon can maintain the catalyst's activity over a longer period, preventing the active centers from being completely covered. However, with the increase in the number of cracking-regeneration cycles, the amount of filamentous carbon formed decreases, becoming shorter and thinner, and there is a significant agglomeration phenomenon. This may be related to the sintering and grain growth of Ni particles during the regeneration process. Additionally, after three regeneration cycles, a large amount of amorphous carbon appeared on the surface of the catalyst, which may be one of the reasons for the decline in catalyst activity.

4. Conclusions

To enhance the activity and durability of the Ni/TiO2 catalyst, this study employed a one-step method to prepare a composite catalyst by mixing the metal active components with vanadium carbide impregnation, thereby avoiding an additional reduction step and simplifying the preparation process. This study also prepared a series of 10Ni-xVC/TiO2 catalysts with different VC doping amounts and studied the impact of reaction temperature on catalyst performance and the efficiency of catalytic methane cracking. The main findings are as follows:

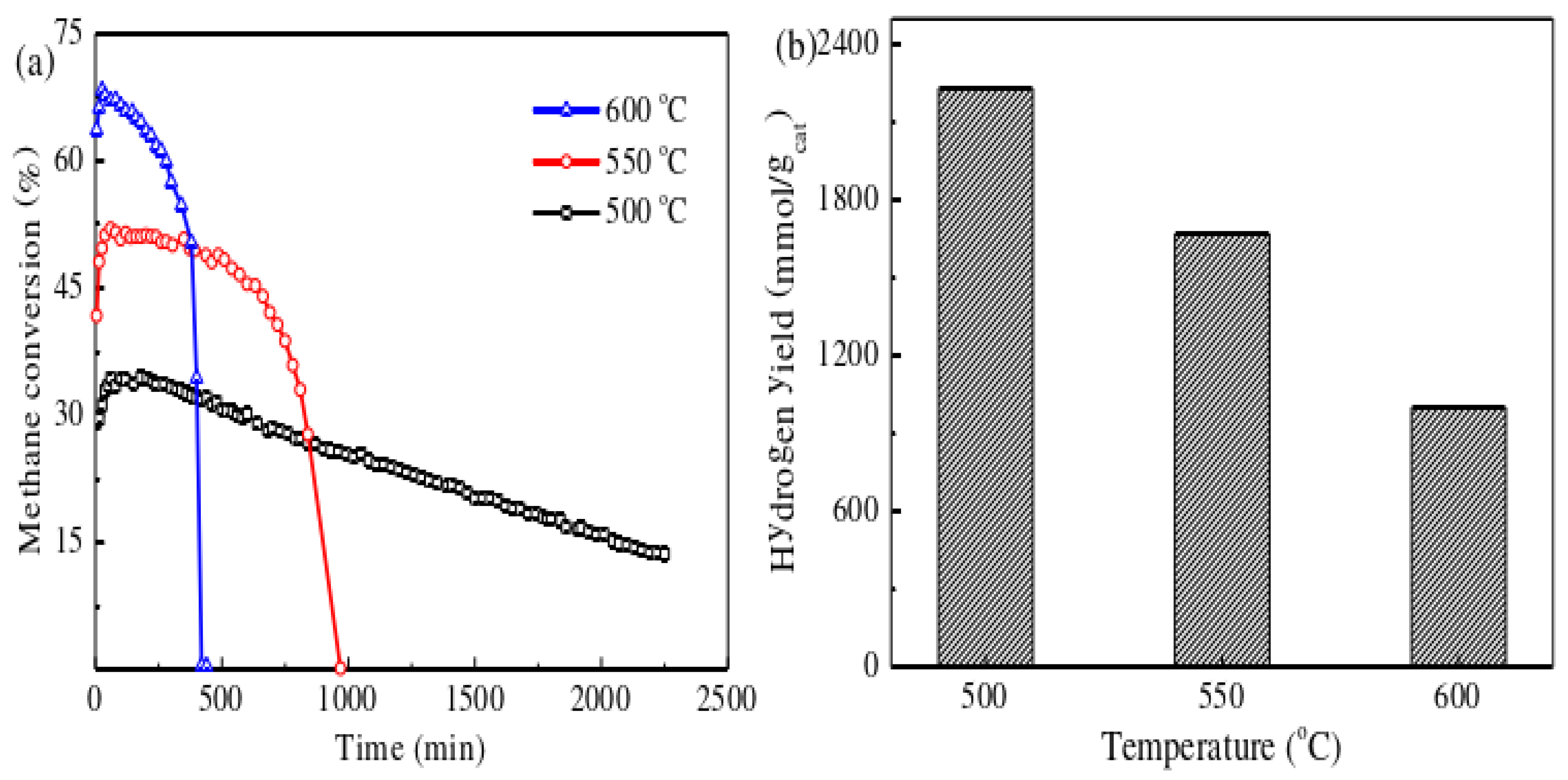

The metal-loaded catalyst was prepared by a one-step method using the traditional impregnation technique, by mixing vanadium carbide with metal precursors. This Ni-VC/TiO2 catalyst has a cylindrical pore structure with a mesostructure, and the pore size is mainly concentrated between 20 and 40 nm. The addition of vanadium carbide significantly improved the performance of the Ni/TiO2 catalyst. The activity of the catalyst first increased and then decreased with the increase of VC content. In particular, the 10Ni-5VC/TiO2 catalyst maintained a methane conversion rate of about 14.2% after 2300 minutes of reaction at 500°C. The addition of VC effectively slowed down the growth of Ni microcrystals during the catalytic methane cracking process. The 10Ni-5VC/TiO2 catalyst had a particle size of 23.7nm before the reaction, which is very close to the optimal particle size of Ni particles (23nm) in the catalytic methane cracking experiment. After 450 minutes of reaction, the size of the Ni crystallites only increased to 24.0nm, showing the smallest growth rate. The reaction temperature has a significant impact on the activity and stability of the catalyst. Lower temperatures help to improve the stability of methane cracking, which may be due to the formation of longer and thicker filamentous carbon on the surface of the catalyst after the reaction. High temperatures, on the other hand, accelerate the deactivation of the catalyst. Raman spectroscopy analysis showed that the reaction temperature significantly affected the graphitization degree of the carbon fibers, and the graphitization degree of the carbon produced by methane cracking increased with the rise in temperature.

The post-reaction Ni-VC/TiO2 catalyst was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and a transmission electron microscope (TEM). The analysis showed that the coke produced by the Ni-VC/TiO2 catalyst mainly presented as "octopus-like" filamentous carbon. These filamentous carbons can serve as carriers for the growth of metal particles in the initial stage. As the filamentous carbon grows, they help to disperse metal particles, thereby improving catalytic performance. However, at high temperatures, the type of carbon produced by methane cracking changed, leading to a decrease in reaction stability. Using CO2 as an activator, a cracking-regeneration cycle experiment was conducted on the post-reaction catalyst in a fixed-bed reactor under atmospheric pressure. The experimental results showed that with the increase in the number of regeneration cycles, the methane conversion rate and reaction stability significantly decreased, mainly due to the growth of Ni crystallites after regeneration and the formation of a large amount of amorphous coke on the surface of the catalyst.

References

- Meiliefiana, M.; Nakayashiki, T.; Yamamoto, E.; et al. One-Step Solvothermal Synthesis of Ni Nanoparticle Catalysts Embedded in ZrO2 Porous Spheres to Suppress Carbon Deposition in Low-Temperature Dry Reforming of Methane [J]. Nanoscale Research Letters, 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velev, O.D.; Jede, T.A.; Lobo, R.F.; et al. Porous silica via colloidal crystallization [J]. Nature, 1997, 389, 447–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Nickel catalysts supported on ordered mesoporous SiC materials for CO2 reforming of methane [J]. Catalysis Today, 2018, 317, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shen, K.; Huang, L.; et al. Facile Route for Synthesizing Ordered Mesoporous Ni–Ce–Al Oxide Materials and Their Catalytic Performance for Methane Dry Reforming to Hydrogen and Syngas [J]. ACS Catalysis, 2013, 3, 1638–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Hossain, S.; Ahmed, M.H.; et al. A Review on Optical Applications, Prospects, and Challenges of Rare-Earth Oxides [J]. ACS Applied Electronic Materials, 2021, 3, 3715–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.S.; Patil, A.V.; Dighavkar, C.G.; et al. Synthesis techniques and applications of rare earth metal oxides semiconductors: A review [J]. Chemical Physics Letters, 2022, 796, 139555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, Z.; Larisa, E.; Rina, S.; et al. Preparation and Mechanical Characteristics of Multicomponent Ceramic Solid Solutions of Rare Earth Metal Oxides Synthesized by the SCS Method [J]. Ceramics, 2023, 6, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.K.; Rubel, M.H.K.; Akbar, M.A.; et al. A review on recent applications and future prospects of rare earth oxides in corrosion and thermal barrier coatings, catalysts, tribological, and environmental sectors [J]. Ceramics International, 2022, 48, 32588–32612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui-jie, L.I.; Ju-ping, Z.; Jian, S.H.I.; et al. Regulation of metal-support interface of Ni/CeO2 catalyst and the performance of low temperature chemical looping dry reforming of methane [J]. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology, 2022, 50, 1458–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Loisel, E.; Cullen, D.A.; et al. On the enhanced sulfur and coking tolerance of NiCo-rare earth oxide catalysts for the dry reforming of methane [J]. Journal of Catalysis, 2020, 393, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Ni/La2O3 Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane: Insights into the Factors Improving the Catalytic Performance [J]. ChemCatChem, 2019, 11, 2887–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blal, M.; Belasri, A.; Benatillah, A.; et al. Assessment of solar and wind energy as motive for potential hydrogen production of Algeria country; development a methodology for uses hydrogen-based fuel cells [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2018, 43, 9192–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoguang, S.; Jia, C.; Yanxing, C.; et al. New Design and Construction of Hierarchical Porous Ni/SiO2 Catalyst with Anti-sintering and Carbon Deposition Ability for Dry Reforming of Methane [J]. ChemistrySelect, 2022, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, S.; et al. A Review of Carbon-Supported Nonprecious Metals as Energy-Related Electrocatalysts [J]. Small Methods, 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.; Blanco, E.; Botana, K.J.; et al. Preparation of some rare earth oxide supported rhodium catalysts: Study of the supports [J]. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 1987, 17, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jung, I.-H. Critical evaluation of thermodynamic properties of rare earth sesquioxides (RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu, Sc and Y) [J]. Calphad, 2017, 58, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthiumporn, K.; Kawi, S. Promotional effect of alkaline earth over Ni-La2O3 catalyst for CO2 reforming of CH4: Role of surface oxygen species on H2 production and carbon suppression [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2011, 36, 14435–14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatesh, A.S. Promotional effect of Gd over Ni/ Y2O3 catalyst used in dry reforming of CH4 for H2 production [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2017, 42, 18805–18816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, M.B.; Setiabudi, H.D.; Trinh Duy, N.; et al. Insight into the influence of rare-earth promoter (CeO2, La2O3, Y2O3, and Sm2O3) addition toward methane dry reforming over Co/mesoporous alumina catalysts [J]. Chemical Engineering Science, 2020, 228, 115967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Highly Carbon-Resistant Y Doped NiO-ZrOm Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane [J]. Catalysts, 2019, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Zeng, L.; et al. On the role of Ce in CO2 adsorption and activation over lanthanum species [J]. Chemical Science, 2018, 9, 3426–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Engineering metal-oxide interface by depositing ZrO2 overcoating on Ni/Al2O3 for dry reforming of methane [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2022, 436, 135195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.A.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Plasma-assisted dry reforming of methane over Mo2CNi/Al2O3 catalysts: Effects of beta-Mo2C promoter [J]. Applied Catalysis B-Environmental, 2022, 301, 120779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, D. Properties of Ni/Y2O3 and its catalytic performance in methane conversion to syngas [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2011, 36, 14447–14454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnisa, F.; Sagar, V.T.; Djinovic, P.; et al. Ni-containing CeO2 rods for dry reforming of methane: Activity tests and a multiscale lattice Boltzmann model analysis in two model geometries [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 413, 127498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cai, W.; Provendier, H.; et al. Hydrogen production from ethanol steam reforming over Ir/CeO2 catalysts: Enhanced stability by PrOx promotion [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2011, 36, 13566–13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilawar Sharma, N.; Singh, J.; Vijay, A.; et al. Investigations of anharmonic effects via phonon mode variations in nanocrystalline Dy2O3, Gd2O3 and Y2O3 [J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2017, 48, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Xia, L.; Li, S.; et al. Superior 3DOM Y2Zr2O7 supports for Ni to fabricate highly active and selective catalysts for CO2 methanation [J]. Fuel, 2021, 293, 120460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Fang, X.; Xu, X.; et al. The promotional effects of plasma treating on Ni/Y2Ti2O7 for steam reforming of methane (SRM): Elucidating the NiO-support interaction and the states of the surface oxygen anions [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2020, 45, 4556–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.S.; Cunha, F.; Barrozo, P. Raman spectroscopy of the Al-doping induced structural phase transition in LaCrO3 perovskite [J]. Solid State Communications, 2021, 114346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triyono, D.; Hanifah, U.; Laysandra, H. Structural and optical properties of Mg-substituted LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by a sol-gel method [J]. Results in Physics, 2020, 16, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xie, F.; Wang, L.; et al. Efficient dry reforming of methane with carbon dioxide reaction on Ni@Y2O3 nanofibers anti-carbon deposition catalyst prepared by electrospinning-hydrothermal method [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2020, 45, 31494–31506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Luo, D.; Xiao, P.; et al. High yield hydrogen production from low CO selectivity ethanol steam reforming over modified Ni/Y2O3 catalysts at low temperature for fuel cell application [J]. Journal of Power Sources, 2008, 184, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Xia, L.; Peng, L.; et al. Ln2Zr2O7 compounds (Ln = La, Pr, Sm, Y) with varied rare earth A sites for low temperature oxidative coupling of methane [J]. Chinese Chemical Letters, 2019, 30, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereñiguez, R.; Gonzalez-delaCruz, V.M.; Caballero, A.; et al. LaNiO3 as a precursor of Ni/La2O3 for CO2 reforming of CH4: Effect of the presence of an amorphous NiO phase [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2012, 123–124, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, G.; Kooser, K.; Urpelainen, S.; et al. Near ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron - and impedance spectroscopy study of NiO-Ce0. 9Gd0.1O2-δ anode reduction using a novel dualchamber spectroelectrochemical cell [J]. Journal of Power Sources, 2018, 378, 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Oemar, U.; Hidajat, K.; Kawi, S. High catalytic stability of Pd-Ni/Y2O3 formed by interfacial Cl for oxy-CO2 reforming of CH4 [J]. Catalysis Today, 2017, 281, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, R.K.; Shukla, A.; Yadav, A.; et al. Effect of metal-support interaction on activity and stability of Ni-CeO2 catalyst for partial oxidation of methane [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2016, 191, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, R.K.; Yadav, A.; Agrawal, A.; et al. Synthesis of highly coke resistant Ni nanoparticles supported MgO/ZnO catalyst for reforming of methane with carbon dioxide [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2016, 202, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Effects of the surface adsorbed oxygen species tuned by rare-earth metal doping on dry reforming of methane over Ni/ZrO2 catalyst [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2019, 264, 118522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Yuqiao, Miao, et al. Oxidative coupling of methane over Y2O3 and Sr–Y2O3 nanorods [J]. Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis, 2021, 134, 711–725.

- Zeng, R.; Jin, G.; He, D.; et al. Oxygen vacancy promoted CO2 activation over acidic-treated LaCoO3 for dry reforming of propane [J]. Materials Today Sustainability, 2022, 19, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hu, S.; Fang, Y.; et al. Oxygen Vacancy Promoted O2 Activation over Perovskite Oxide for Low-Temperature CO Oxidation [J]. ACS Catalysis, 2019, 11, 9757–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; He, S.; Li, L.; et al. Morphology-directed synthesis of Co3O4 nanotubes based on modified Kirkendall effect and its application in CH4 combustion [J]. Chemical Communications, 2012, 48, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xi, R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Promoting the surface active sites of defect BaSnO3 perovskite with BaBr2 for the oxidative coupling of methane [J]. Catalysis Today, 2020, 374, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.Q.; Wan, H.L. In situ confocal microprobe Ramanspectroscopy study of CeO2/BaF2 catalyst for theoxidative coupling of methane [J]. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions, 1997, 93, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ghani, N.A.; Azapour, A.; Syed Muhammad, A.F. a. , et al. Dry reforming of methane for hydrogen production over NiCo catalysts: Effect of NbZr promoters [J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2018, 44, 20881–20888. [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Garcia, A.; Louvier-Hernandez, J.F.; Almendarez-Camarillo, A.; et al. Participation of surface bicarbonate, formate and methoxy species in the carbon dioxide methanation catalyzed by ZrO2-supported Ni [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2017, 29, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ying, M.; Yu, J.; et al. NixAl1O2-δ mesoporous catalysts for dry reforming of methane: The special role of NiAl2O4 spinel phase and its reaction mechanism [J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2021, 291, 120047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).