1. Introduction

The steel production process is one of the key elements of the modern metallurgical industry. Steel is the main structural material used in a variety of areas, from construction and mechanical engineering to electronics and household appliances. The quality of steel is determined by its chemical composition, structure and properties, which in turn depend on many factors, including the technological parameters of its production. One of the most important stages in steel production is the deoxidation process, aimed at removing dissolved oxygen from liquid steel and preventing the formation of undesirable non-metallic inclusions, such as oxides, which can significantly impair its mechanical properties [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The deoxidation process is traditionally carried out using ferroalloys such as ferrosilicon (FeSi), ferromanganese (FeMn), as well as aluminum (Al) and other elements with a high affinity for oxygen. These elements react with the oxygen dissolved in the steel, forming oxides that either rise to the surface as slag or remain in the metal as small inclusions [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Traditional deoxidizers such as ferrosilicon and ferromanganese remain the main materials for deoxidation in industry. Ferrosilicon is widely used due to its high efficiency and availability. However, its use may be accompanied by the formation of undesirable phases such as carbides and silicates, which may lead to a decrease in ductility and an increase in brittleness of steel. Ferromanganese, another widely used deoxidizer, also has a high affinity for oxygen and sulfur, but its use is associated with the possibility of forming manganese oxides, which can worsen the structure and properties of steel. Aluminum is a highly effective deoxidizer, but its use is limited by its tendency to form large non-metallic inclusions, which can serve as sources of brittleness in steel. However, traditional deoxidizers do not always provide a uniform distribution of inclusions, which can negatively affect the mechanical properties of steel, especially in the production of high-quality steel grades that require a minimum content of non-metallic inclusions and a homogeneous structure [

21,

22,

23].

One of the promising areas in the field of steel deoxidation is the use of complex alloys, which are alloys of several elements with a high affinity for oxygen. An example of such alloys are complex systems containing iron, silicon, manganese and aluminum (e.g., Fe-Si-Mn-Al). Complex alloys can offer significant advantages over traditional deoxidation methods due to the synergistic interaction of the elements that make up their composition. This interaction allows for a more uniform distribution of inclusions in steel, improved mechanical properties, and reduced production costs due to the use of cheaper raw materials and reduced energy consumption [

24,

25,

26,

27].

In recent years, complex alloys have attracted increasing attention from researchers and industrial specialists. This is due to the need to improve the quality of steel and improve its properties for modern industrial applications, including the automotive, aerospace and energy sectors. Modern requirements for steels include high strength, ductility, corrosion resistance, and the ability to be used in extreme conditions, which requires minimizing the content of non-metallic inclusions and a homogeneous structure.

Despite the obvious advantages of using complex alloys in steel deoxidation, there are still many unresolved issues and challenges. A more detailed study of the phase composition, morphology and behavior of inclusions in steel deoxidized with such alloys, as well as their effect on the final mechanical properties of steel, is required. It is important to understand how exactly the elements in the complex alloy interact, how they affect the deoxidation process and the formation of the steel structure. In addition, experimental studies are required to determine the optimal conditions and chemical compositions of such alloys and their use in various technological processes [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of traditional deoxidizers and complex alloys on the structure and properties of steel. The study is aimed at conducting a comparative analysis of the structure of steel deoxidized with different types of alloys, as well as identifying the phase composition and morphological features of steels after deoxidation. Additionally, the mechanical properties of steel (such as strength, ductility) will be assessed, which will allow us to determine the effect of each type of deoxidizer on the distribution of inclusions in steel.

The following tasks will be considered within the framework of this work:

1. Obtaining semi-industrial and synthetic complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys;

2. Carrying out metallographic analysis of steel samples deoxidized using traditional and complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys (semi-industrial and synthetic);

3. Studying the morphology of inclusions in steel and assessing their distribution using electron microscopy methods;

4. Assessing the mechanical properties of steel deoxidized with different types of ferroalloys and comparing them;

5. Analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of using complex ferroalloys compared to traditional methods of steel deoxidation.

It is expected that this research will contribute to the development of new steel deoxidation methods and offer more efficient and cost-effective solutions for the metallurgical industry. The results obtained can be used to improve steel production technology, which will lead to lower costs, higher quality of the final product and wider application of steel in high-tech industries.

This study is aimed at solving both fundamental and applied problems related to the development of new materials and technologies required to improve the properties of steel and optimize production processes. Given the importance of steel for modern industry and the growing demands on its quality, the results of the work can be useful for both the scientific community and for industry representatives involved in the production and processing of steel.

Thus, the use of complex alloys is a promising direction in the development of modern steel deoxidation technologies. Research in this area can lead to a significant improvement in the properties of steel, an increase in its service life and an expansion of its application areas, which is especially important in the context of global competition and increasing demands on the quality of materials. This study will examine the effect of various types of complex alloys on the structure and properties of steel, which will allow us to propose new approaches to the production of this important material.

2. Materials and Methods

The Fe-Si-Mn-Al complex alloy was obtained in a two-electrode ore-thermal electric furnace with a conductive hearth, where one of the electrodes is integrated into the hearth using a coked hearth mass [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

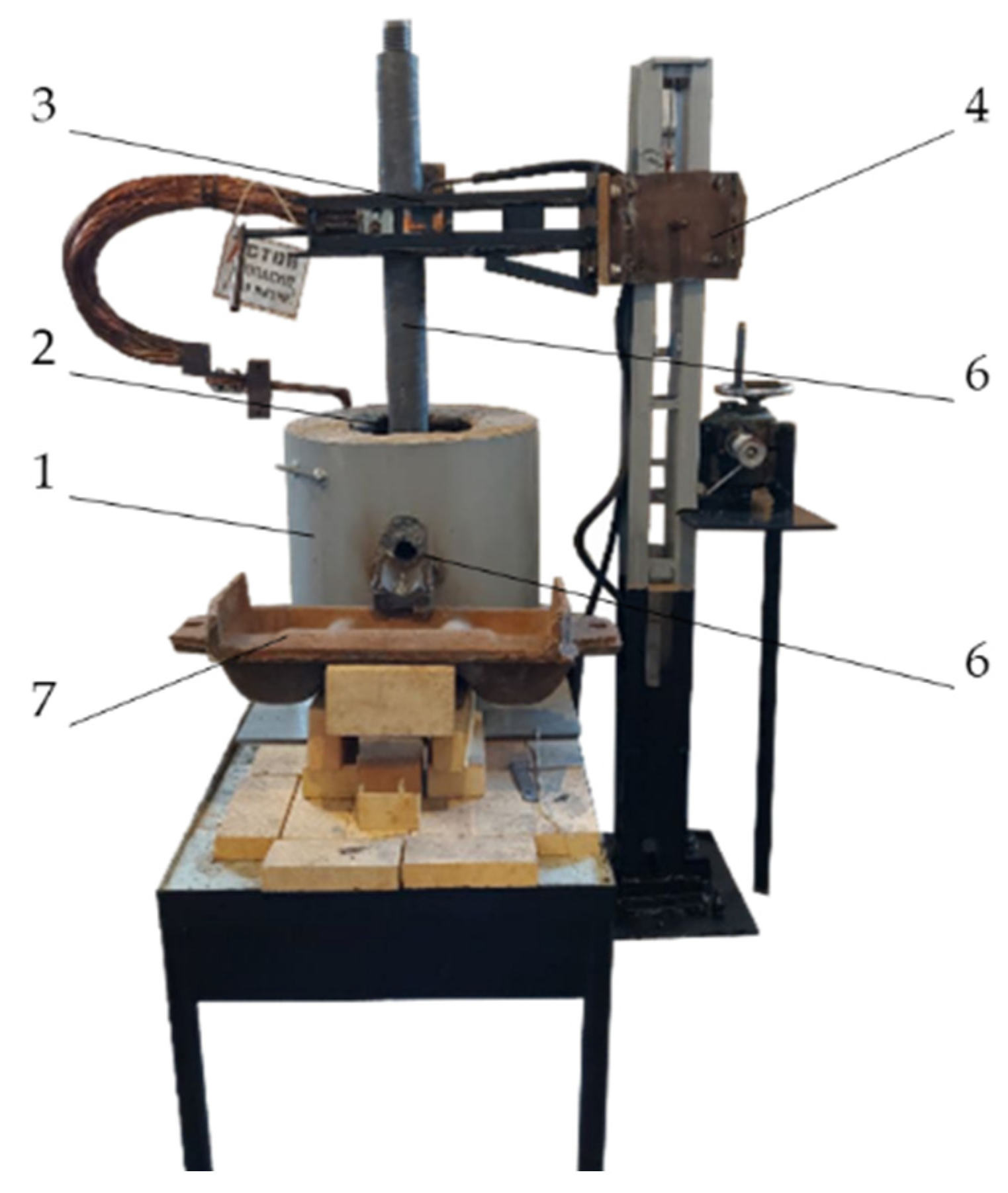

36]. The experimental setup of the laboratory furnace is shown in

Figure 1 [

37,

38]. The feedstock materials used were high-ash coal from the Saryadyr deposit, substandard manganese-containing ore from the Bogach deposit, and quartzite, which was added to adjust the chemical composition of the mixture and bind excess carbon. The technical and chemical characteristics of the materials used are given in

Table 1 [

39,

40].

As stated above, in order to study the efficiency of steel deoxidation, in addition to the semi-industrial samples of complex alloys, five types of synthetic complex alloys were manufactured. The alloy compositions were varied by using the starting materials presented in

Table 2 in different mass ratios. These synthetic alloys were obtained in order to study their physicochemical properties, deoxidation characteristics and influence on the quality of the metal. Particular attention was paid to optimizing the content of the main components (Fe, Si, Mn, Al) [

41,

42,

43].

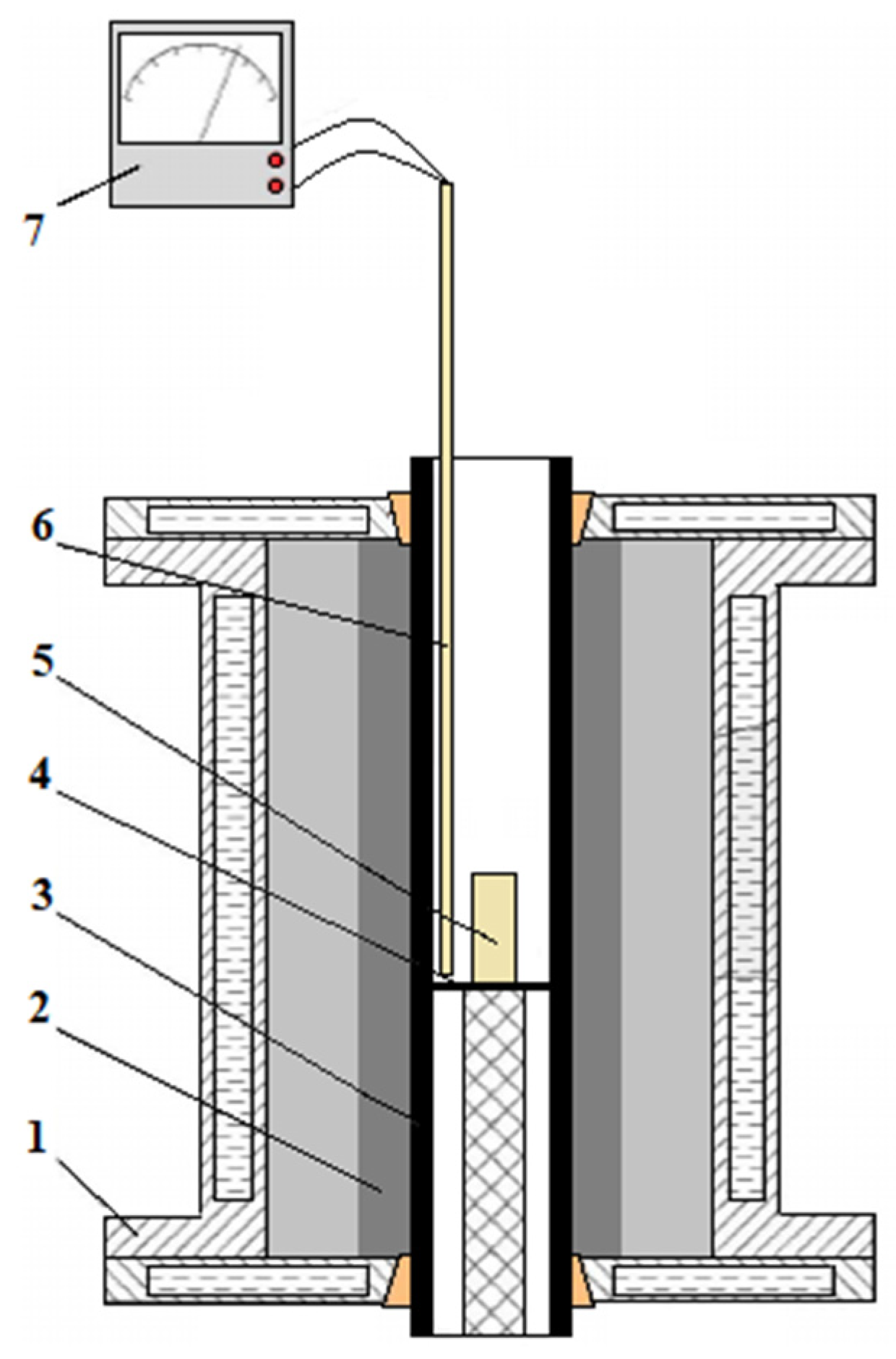

Experiments on obtaining pilot samples of the complex deoxidizer by the fusion method and deoxidation of steel were carried out in the Tamman furnace [

44,

45]. The Tamman resistance furnace is a research facility designed to study metallurgical processes at high temperatures. The Tamman furnace consists of a transformer, a housing and a graphite heater of the furnace. The cylindrical housing of the furnace is fixed on the transformer terminals (busbars) (

Figure 2). The heater is a graphite tube fixed between two copper brass contacts at the top and bottom. The furnace casings are made with water cooling. The temperature in the furnace is regulated smoothly, using a thyristor voltage regulator. The temperature was measured using an electronic recorder “Thermodat” tungsten-rhenium thermocouple VR-5/20, the hot junction of which in a corundum cover was brought into the working space of the furnace between the graphite tube and the crucible.

The obtained semi-industrial and synthetic complex alloys were used for deoxidation of St3 steel, and the results of their application were carefully analyzed. The studies included an analysis of the microstructure of St3 steel, performed in accordance with the requirements of GOST 1778-70 [

46]. For this purpose, samples suitable for metallographic analysis were prepared, which covered the study of the microstructure and chemical composition of the material. The composition of non-metallic inclusions was determined by the energy-dispersive analysis (EDX) method on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in the metal science and flaw detection laboratory of the Analytical Control Center of JSC Qarmet.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provides the ability to analyze the microstructure of a material in detail, including the determination of morphology and phase distribution. The interaction of the electron beam with the sample surface allows for high-resolution images to be obtained, as well as information on the topography and structure of the material under study. The use of this method in combination with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) provides a deep understanding of the elemental composition of non-metallic inclusions such as oxides, sulfides, and carbides. Thus, SEM in combination with EDX serves as a powerful tool for studying the microstructure of steel, the influence of inclusions on its properties, and the subsequent improvement of production technology [

47,

48].

The preparation of steel samples for optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) included several stages carried out in strict accordance with established standards, such as GOST 1778-70 (preparation of metal samples for microstructural analysis) and GOST 5640-2020 (Metallographic method for assessing the microstructure of flat rolled steel) [

46,

49].

The main stages of preparation were as follows:

Sampling: Samples were cut from steel specimens using a water-cooled saw to minimize thermal impact on the material and avoid structural changes. Sample sizes met GOST requirements and were adapted for further preparation.

Grinding: To remove oxide film and unevenness, the surface of the samples was subjected to rough grinding using sandpaper with successively smaller grain (from P240 to P1200). Grinding was performed using water for cooling, which prevented local heating and deformation.

Polishing: After grinding, the samples were polished using diamond paste with grain sizes of 3 and 1 µm to obtain a mirror surface, which ensured optimal quality for observing microstructures under an optical microscope. Polishing was carried out on a polishing machine using special napkins impregnated with a suspension of diamond powder.

Etching: To reveal microstructural elements, the steel was etched using a 4% solution of nitric acid in ethanol (Nitral reagent), which allowed grain boundaries and phases to be clearly identified. The etching time was controlled depending on the required contrast level [

47,

48].

SEM Analysis: Sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy involved applying a conductive layer of gold or carbon to the sample surface to improve conductivity and prevent charge accumulation during examination. The conductive layer was applied using magnetron sputtering in a vacuum chamber.

These preparation stages made it possible to ensure the high quality of surfaces necessary to obtain reliable data when studying the microstructural and phase characteristics of steel samples using both optical microscopy and SEM analysis.

3. Results

Laboratory tests for obtaining semi-industrial complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys were conditionally divided into 3 periods: heating up the electric furnace and bringing the electric furnace to operating mode and smelting the complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloy with two chemical compositions from the presented charge materials in

Table 1. The results of the obtained complex alloys are presented in

Table 3 (positions 1 and 2). [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Thus, the conducted experimental tests indicate the fundamental possibility of smelting complex alloys based on Fe-Si-Mn-Al using high-ash coal from the Saryadyr deposit and substandard manganese-containing ore from the Bogach deposit. The charge on the furnace throat did not sinter and its processing was carried out without difficulties. Opening the taphole by the end of the period was much easier. The output of the complex alloy melt was active. [

41,

42,

43].

The Tamman furnace smelting process for producing a synthetic complex alloy involves heating the charge to a temperature at which the components melt and interact to form the target alloy. The charge materials used were various components, as shown in

Table 2, and each was loaded in specified mass fractions optimized to achieve the desired properties of the synthetic Fe-Si-Mn-Al complex alloy.

After melting, the melt was left in the furnace for slow cooling and crystallization, which minimized internal stresses in the alloy and provided the required structure suitable for effective use in the steel deoxidation process.

As a result of the experiments conducted to obtain synthetic complex alloys, their chemical composition was analyzed. Data on the content of the main elements in samples of Fe-Si-Mn-Al complex alloys are given in

Table 3 (positions 3 and 7). These data demonstrate variations in the concentration of elements, which allows us to evaluate the efficiency of the alloying process and the compliance of the obtained samples with the specified chemical characteristics.

Deoxidation of steel was carried out by complex alloys Fe-Si-Mn-Al obtained using substandard manganese-containing ore and high-ash coal, as well as synthetic complex alloys obtained by remelting standard deoxidizers such as FeSi, FeSiMn, Mnmet and Al. Standard deoxidizers were also used for comparative analysis (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

Table 4 presents the results of microstructural and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) of nine studied samples of deoxidized steels (

Figure 3). The table contains data on the microstructure, content of non-metallic inclusions and hardness of various steel samples, performed in accordance with the requirements of GOST 9013-59.

The analysis showed differences in the types of microstructures, types of non-metallic inclusions and hardness values. The samples demonstrated both homogeneous and zonally heterogeneous structures (ferrite-pearlite, bainitic, martensitic), as well as differences in porosity. Among the non-metallic inclusions, oxides, sulfides, nitrides and carbides of various elements were found, including complex compounds. The hardness of the samples varied in the range from 25.50 to 46.50 HRc, which indicates a significant effect of the composition and microstructure on the mechanical properties of steel.

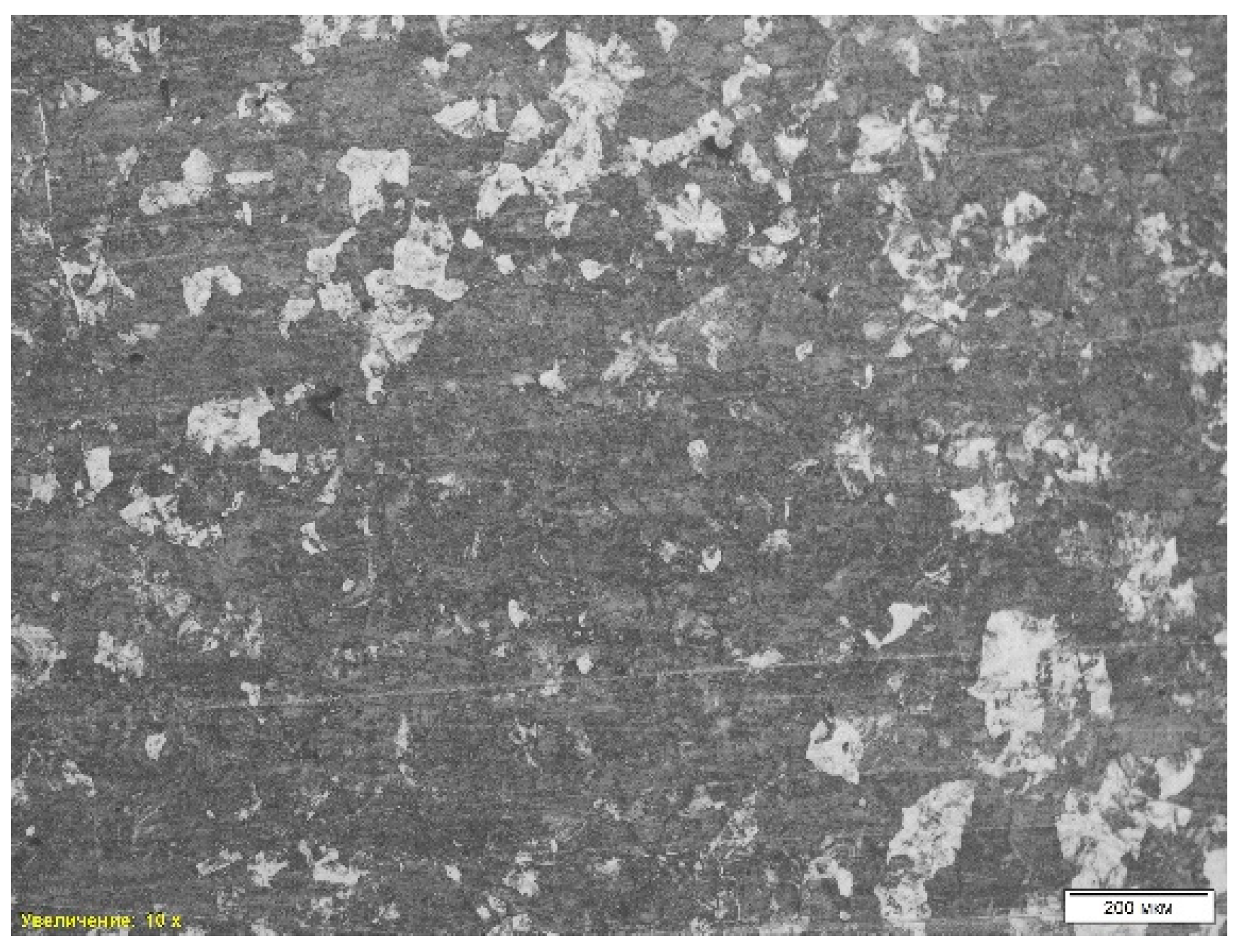

The first microstructural analysis was performed on a sample obtained without deoxidation using optical microscopy with a magnification of 10 times. The analysis showed that the structure of the material is represented by a combination of ferrite and pearlite (

Table 4, position 1). Also, a pronounced dendritic structure is observed in the microstructure, which indicates the nature of the material crystallization process. Dendritic formations indicate rapid cooling of the liquid metal, which leads to the formation of a branching structure characteristic of casting conditions.

Another feature of the microstructure is porosity, which appears as dark areas without clear boundaries. The pores were formed as a result of gas formation or shrinkage during cooling and solidification, which reduces the strength characteristics of the material and can cause stress concentration in local areas. Thus, the microstructure of the sample “St 1” is a ferrite-pearlite mixture with a dendritic structure and porosity, which confirms its casting origin and high cooling rates (

Figure 4).

In addition to the microstructural analysis, a scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was performed on the St 1 steel sample. During the analysis of non-metallic inclusions, manganese sulfides were detected, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce the strength characteristics of the material. The average hardness of the sample was 25.50 HRc. The chemical composition was analyzed using energy dispersive spectral analysis (EDS) at several points of the sample. The main results of the analysis show that the sample consists of non-metallic inclusions and oxide phases.

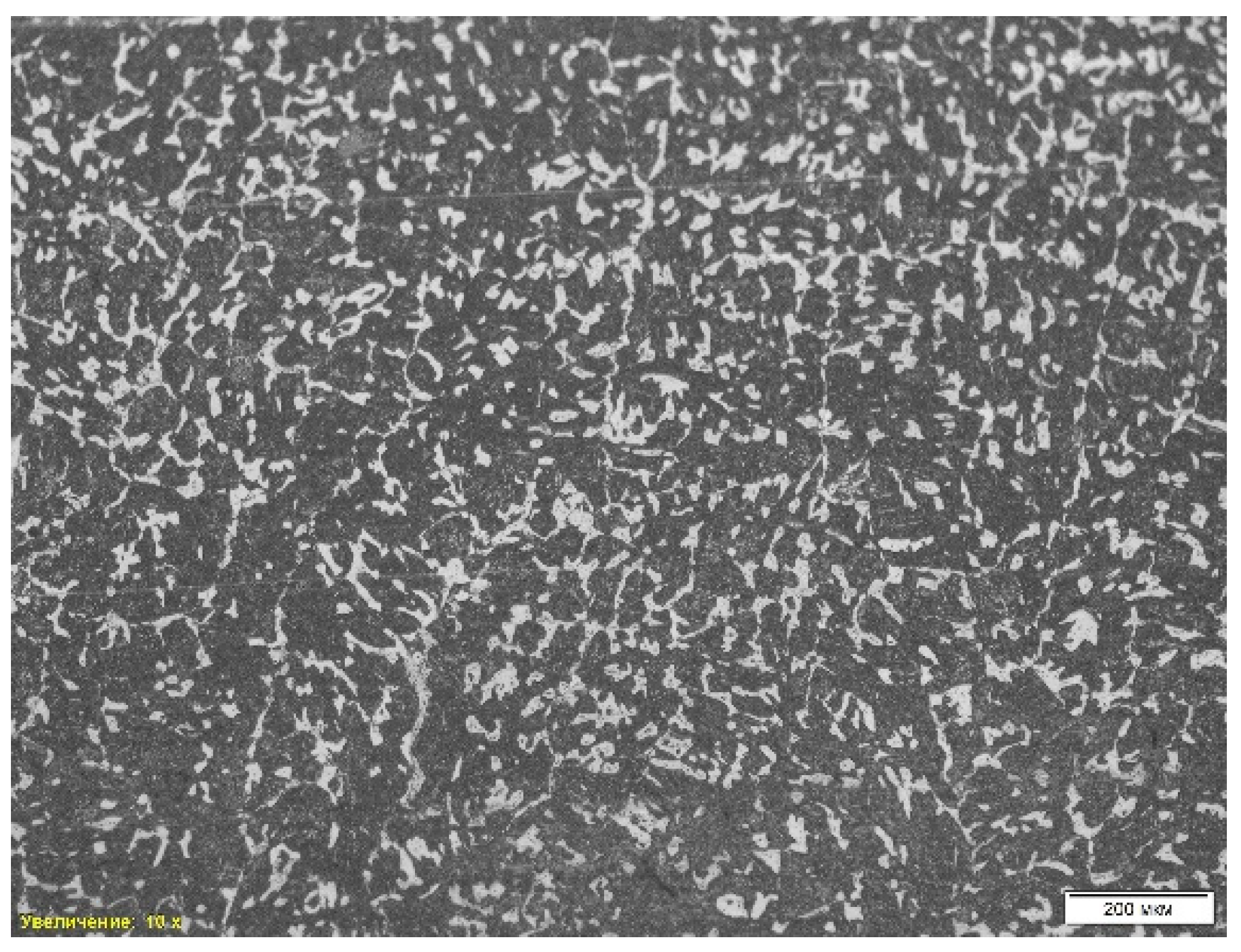

Figure 5 shows the microstructure of the steel sample “St 2-1”. The analysis revealed a combination of ferrite and pearlite, where the dark areas correspond to pearlite, and the light areas represent ferrite (

Table 2, position 2). A pronounced dendritic structure is observed, formed during rapid cooling of the liquid metal, which indicates the casting nature of the material. The dendritic structure contributes to the heterogeneity of mechanical properties, since cooling is uneven, forming zones of different strength. Also noted is porosity resulting from shrinkage during solidification, which reduces the strength and ductility of the alloy.

A scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was also performed on the St 2-1 steel sample. Non-metallic inclusions such as iron oxides, titanium carbide, manganese sulfide and corundum were found, which can negatively affect the mechanical properties of steel, reducing its ductility and strength. The average hardness of the sample was 32.50 HRc. The chemical composition was analyzed using energy-dispersive spectral analysis (EDS), and the presence of a significant amount of manganese sulfides and oxide phases was revealed.

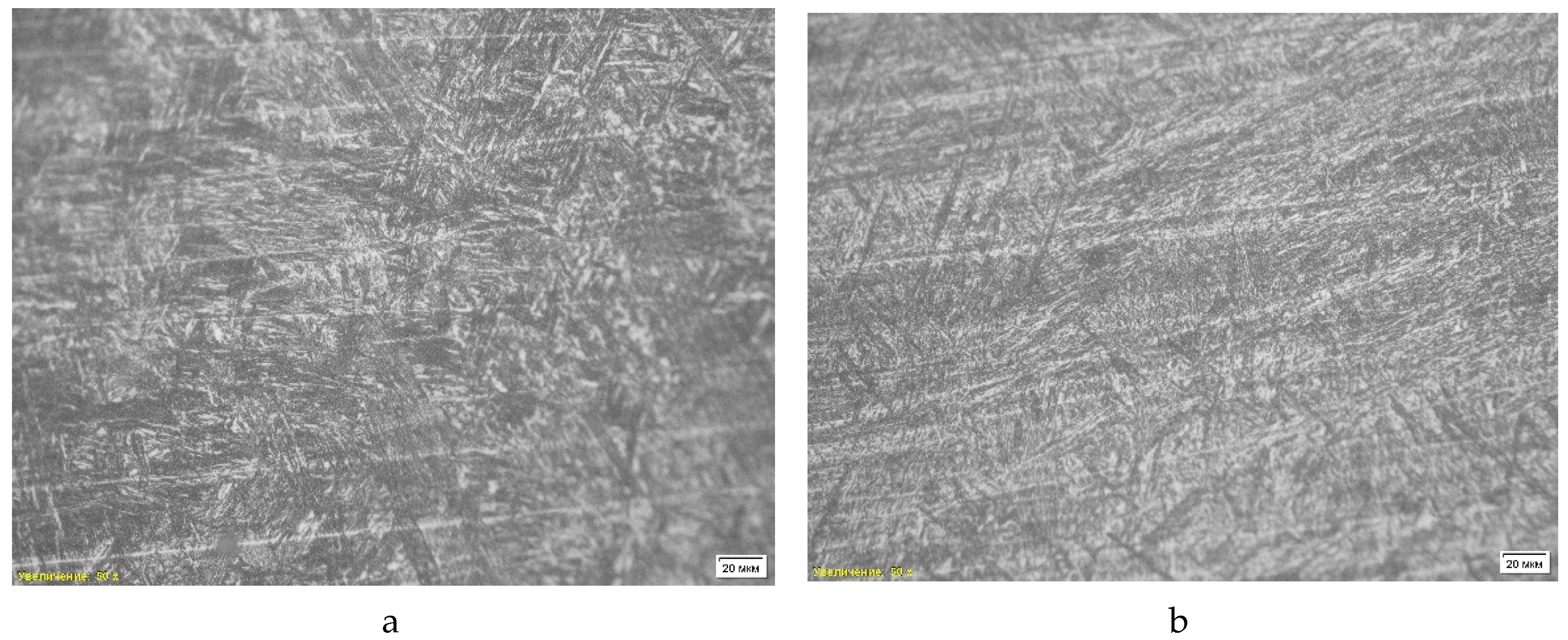

The microstructure of the third sample (

Figure 6) is of the bainitic type. The image with a 10x magnification shows a uniform distribution of bainitic regions, indicating an intermediate structure between ferrite and martensite, obtained as a result of isothermal quenching. A 50x magnification allows us to highlight the fine lamellar structure characteristic of lower bainite formed at relatively low temperatures. This structure shows a high degree of dispersion and the presence of many oriented plates, which ensures high strength of the material while maintaining plasticity, making it suitable for operating conditions with impact loads.

In addition to the microstructural analysis, a scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was performed on the sample of grade “St2-2”. The study revealed non-metallic inclusions such as titanium nitrides and aluminum phases, which can affect the mechanical properties of the material. The average hardness was 37.00 HRc.

The fourth sample (

Figure 7) is characterized by a ferrite-pearlite structure with a dendritic structure, which is the result of rapid cooling and the casting process. The dendritic structure is formed during the crystallization of the metal from the liquid phase, which creates characteristic branching formations. Central porosity, which occurs during shrinkage and gas formation, is also detected. This porosity is concentrated mainly in the central part of the sample and can cause a decrease in strength characteristics and the occurrence of defects under mechanical loading.

During the analysis of non-metallic inclusions, titanium nitrides, aluminum oxides and manganese sulfides were detected, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce the strength characteristics of the material. The average hardness of the sample was 33.75 HRc. The chemical composition was analyzed using energy dispersive spectral analysis (EDS) at several points of the sample. The main results of the analysis show that the sample consists of non-metallic inclusions and oxide phases.

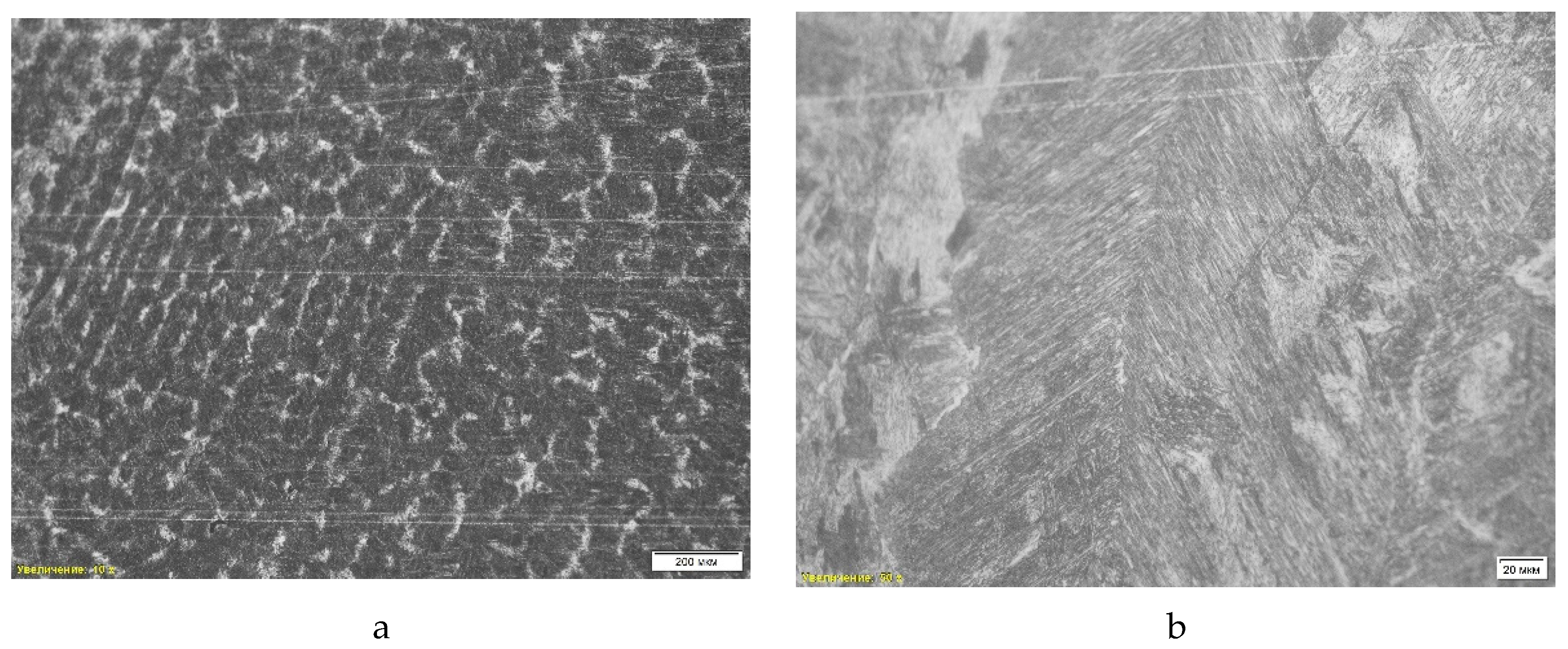

The fifth sample (

Figure 8) is characterized by zonal heterogeneity, including bainitic structure and dendritic formations. The image with a magnification of 50 times shows the lamellar structure of bainite obtained as a result of isothermal quenching, which helps to improve the strength characteristics. The image with a magnification of 10 times shows the dendritic structure, which indicates the process of crystallization from the liquid phase at high cooling rates. There is also central porosity, which reduces the strength of the material and can cause cracks.

In addition to the microstructural analysis, a scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was also carried out for the sample of grade “St3-1” steel. During the analysis of non-metallic inclusions, manganese sulfides, aluminum nitrides and iron oxides were found, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce the strength characteristics of the material. The average hardness of the sample was 46.50 HRc.

The sixth sample (

Figure 9) has a bainitic structure with central porosity. This structure is due to specific cooling conditions and isothermal quenching, which allows achieving high strength characteristics while maintaining some plasticity. The central porosity observed in the sample is formed during shrinkage and can negatively affect the durability of the material, reducing its resistance to mechanical loads.

In addition to the microstructural analysis, a scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was performed for the sample of grade “St3-2”. During the analysis of non-metallic inclusions, corundum, manganese sulfides and complex carbides (niobium, titanium, molybdenum) were found, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce the strength characteristics of the material. The average hardness of the sample was 40.25 HRc.

The seventh sample (

Figure 10) is represented by a pearlitic structure with a shrinkage cavity in the center. The pearlitic structure, consisting of alternating ferrite and cementite plates, provides balanced mechanical properties such as strength and ductility. The presence of a shrinkage cavity formed during solidification reduces the overall strength of the sample and makes it more vulnerable to cracking.

In addition to the microstructural analysis, a SEM analysis was conducted for the sample of grade “St3-3” steel. During the analysis of non-metallic inclusions, manganese sulfides, complex inclusions (manganese sulfide, corundum) and nitrides (aluminum, titanium) were detected, which can reduce the strength characteristics of the material. The average hardness of the sample was 40.20 HRc.

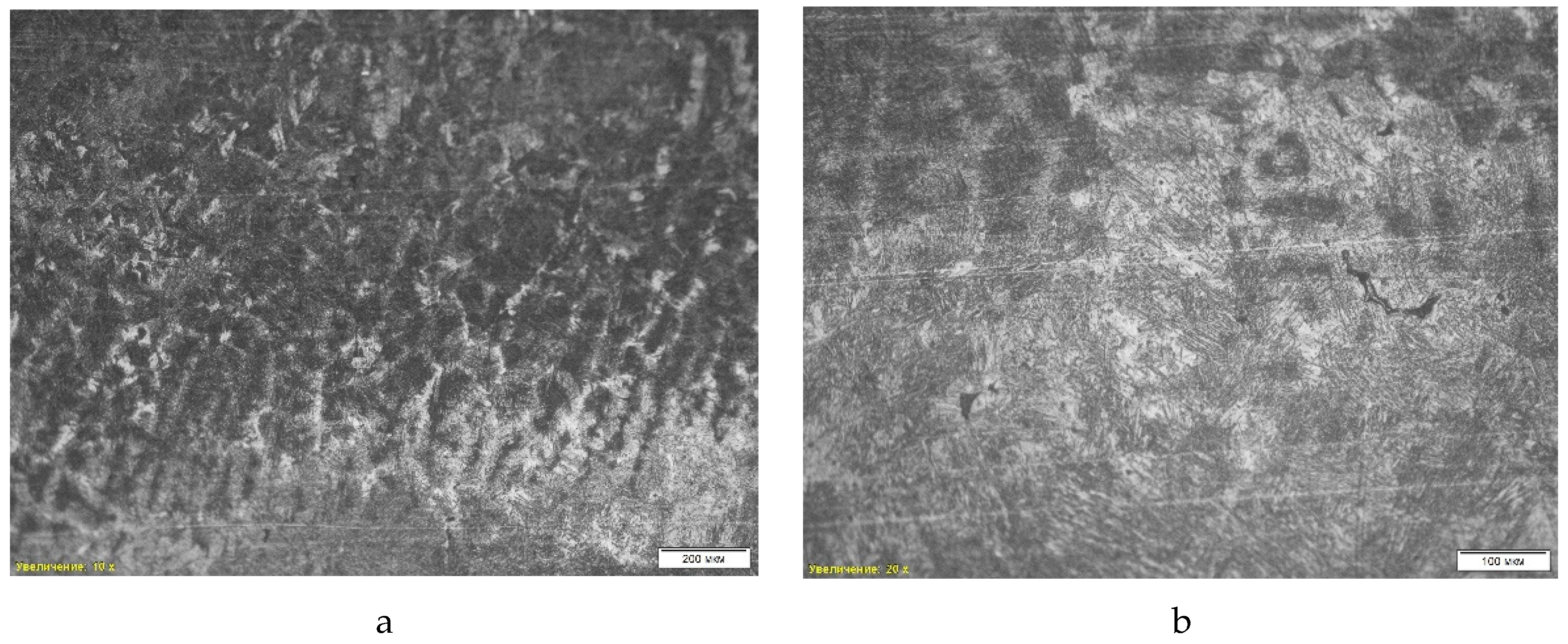

The eighth sample (

Figure 11) includes martensite and a dendritic structure. Martensite is characterized by high hardness and the presence of lamellar structures that form during rapid cooling from the austenite phase. As a result, the material acquires high strength, but becomes less plastic. The dendritic structure formed during crystallization from the liquid phase is also present, indicating the casting origin of the material and causing its structural heterogeneity.

SEM analysis was performed for a sample of steel grade “St3-4”. The analysis revealed manganese sulphides, complex corundum (aluminum, calcium), and complex inclusions (corundum, titanium nitride, manganese sulphide), which can negatively affect the mechanical properties of steel, reducing its ductility. The average hardness of the sample was 33.50 HRc.

The ninth sample (

Figure 12) has a martensitic structure and central porosity. Martensitic regions are characterized by a lamellar structure, which is formed during rapid cooling of the material from the austenitic phase, which provides high hardness but reduces plasticity. Central porosity formed during the solidification process negatively affects the strength characteristics and increases the risk of defects.

A scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis was performed on a sample of grade “St3-5” steel. Complex inclusions such as manganese sulfides, corundum (aluminum, calcium), and titanium carbide were found, which can negatively affect mechanical properties, reducing strength and increasing susceptibility to brittle fracture. The average hardness of the sample was 37.00 HRc.

The results of the study of the type of non-metallic inclusions in steel samples show their significant influence on the formation of the microstructure and mechanical properties of steel. Depending on the complex deoxidizers used, different types of non-metallic inclusions are observed in different samples, which affects such parameters as porosity, hardness and overall quality of the material.

4. Discussion

The results of the study of the microstructure of steel samples show that the variety of deoxidizers used has a significant effect on the final microstructure and, consequently, on the mechanical properties of steel. Depending on the composition and deoxidation process, ferrite-pearlite, bainitic and martensitic microstructures were formed, each of which has its own characteristics and properties.

In samples with a ferrite-pearlite structure, such as St0 and St1 (with traditional deoxidizers), rounded grains and non-uniform structure were observed. Such a microstructure is usually associated with lower values of hardness and strength, which is confirmed by the results of hardness tests (e.g., 25.50 HRc for St0). Rounded ferrite grains and a significant number of pearlite areas contribute to increased ductility, but reduce the overall mechanical strength.

The results of the study presented in [

50] confirm the significant influence of deoxidizers on the microstructure and mechanical properties of steel. The study highlights the correlation between the type of deoxidizer and the resulting microstructure, varying from ferritic-pearlite to bainitic and martensitic structures. The observed changes in grain morphology and inclusion distribution highlight the importance of optimizing the deoxidation process to achieve the desired combination of strength and ductility. In addition, the results highlight the role of cooling rate and alloy composition in determining the final microstructural characteristics, which is consistent with our observations on the effect of complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys on the mechanical properties of steel. [

51,

52,

53]

The bainitic microstructure, characteristic of samples 2-2 and 3-1, exhibits significantly higher hardness, reaching 46.50 HRc. This structure is formed at moderately rapid cooling rates and is characterized by higher strength due to the thin plate-like elements of bainite, which increase the resistance to deformation. However, the presence of bainitic structure can also reduce ductility, especially in the presence of significant amounts of non-metallic inclusions, such as titanium nitrides and complex silicates.

The martensitic structure observed in samples 3-4 and 3-5 is characterized by high hardness and brittleness. For example, sample 3-4 has a hardness of 33.50 HRc with a dendritic structure and low porosity. Martensite is formed during rapid cooling and provides maximum hardness, making this structure suitable for applications requiring high wear resistance. However, brittleness remains a significant drawback, requiring additional alloying or heat treatment to improve ductility.

In addition, the non-uniform structures with dendritic structure observed in some samples (e.g., 3-1 and 3-3) indicate complex crystallization conditions and possible deficiencies in the cooling process. Dendritic structure leads to the formation of central porosity and can contribute to the deterioration of mechanical properties, especially in the presence of large non-metallic inclusions.

The analysis of steel deoxidation practices in CIS metallurgical plants [source] highlights the advantages of using complex alloys over traditional deoxidizers. While conventional deoxidation methods involving ferrosilicon, ferromanganese, and aluminum often result in the formation of high-melting oxides like Al₂O₃ and SiO₂, complex alloys containing elements such as silicon, manganese, aluminum, and calcium allow for the immediate formation of more favorable non-metallic inclusions at the first stage of deoxidation. These inclusions are easier to assimilate by slag, reducing their overall quantity in the steel and improving its mechanical properties. Furthermore, the integration of surface-active elements like calcium and barium enhances the modification of non-metallic inclusions, contributing to increased strength and ductility. These findings demonstrate the potential of complex alloys to address key challenges in steel deoxidation, such as inclusion modification and cost-effectiveness [].

Thus, it can be concluded that the microstructure of steel samples obtained as a result of deoxidation and cooling plays a key role in the formation of their mechanical properties. Optimization of crystallization conditions and control of the deoxidation process can significantly improve the microstructure and, therefore, ensure balanced strength and ductility of steel.

Conclusions

As a result of the conducted study, both semi-industrial and synthetic complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys were used. Semi-industrial alloys contained manganese (Mn) in the amount of 20.30-48.80%, silicon (Si) in the amount of 27.09-37.79% and aluminum (Al) in the amount of 7.93-12.85%. These alloys provided stable results in terms of improving the microstructure and mechanical properties of steel. Synthetic alloys had a manganese (Mn) content in the range of 33.97-48.06%, silicon (Si) in the range of 29.15-35.70% and aluminum (Al) in the range of 7.93-11.67%. Synthetic alloys made it possible to study in more detail the effect of individual components on the phase composition and inclusion distribution. They also showed high efficiency in reducing the content of non-metallic inclusions such as manganese sulphides and iron oxides, which improved ductility and reduced the risk of defect formation.

The study also analyzed the effects of using different temperature conditions and cooling rates on the formation of the steel microstructure. It was found that a moderately high cooling rate promotes the formation of a bainitic microstructure, which provides high hardness and strength, reaching 46.50 HRc. Slow cooling, on the contrary, leads to the formation of a ferrite-pearlite microstructure, which is characterized by lower hardness (25.50 HRc), but provides better ductility of steel.

Additionally, the morphology and distribution of non-metallic inclusions were studied. Samples obtained using complex alloys had a more uniform distribution of inclusions, such as aluminum oxides and titanium nitrides, which contributed to improved mechanical properties. Samples with a martensitic microstructure obtained by rapid cooling showed high hardness (up to 46.20 HRc), but were more brittle due to the presence of large non-metallic inclusions, such as manganese sulfides and carbides.

The obtained data indicate that the use of different types of deoxidizers significantly affects the microstructure and mechanical properties of steel. The use of complex Fe-Si-Mn-Al alloys allows achieving a more uniform distribution of non-metallic inclusions and improving the mechanical properties of steel compared to traditional deoxidizers.

The highest hardness (46.50 HRc) was demonstrated by samples with a bainitic structure obtained using complex alloys. These samples were also characterized by minimal porosity and the presence of finely dispersed non-metallic inclusions, such as corundum and titanium nitrides. In turn, samples with a ferrite-pearlite microstructure treated with traditional deoxidizers had the lowest hardness values (25.50 HRc) and a more pronounced heterogeneity of the structure, which reduced their strength characteristics.

The study focused on non-metallic inclusions such as oxides, sulfides and nitrides, which play a key role in the formation of the steel microstructure. Samples deoxidized using complex alloys demonstrated a more uniform distribution of non-metallic inclusions, which contributed to improved mechanical properties. In particular, inclusions of corundum and titanium nitrides found in bainitic and martensitic structures ensured high hardness and strength of the material.

The martensitic structure formed in some samples provided high hardness (up to 46.20 HRc), but had a significant drawback in the form of low plasticity and high brittleness. The dendritic structure and central porosity observed in some samples had a negative effect on mechanical properties and increased the risk of defects during operation.

Thus, optimization of the composition and conditions of application of complex deoxidizers, as well as microstructure control, can contribute to improving the mechanical properties of steel, reducing its brittleness and increasing its service life. The results obtained can be used to develop new effective methods of steel deoxidation, which is especially important for use in high-tech industries requiring materials with high strength and plastic characteristics.

Supplementary Materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Google Drive repository: Research results

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Zh., A.N., O.Z. and B.K.; methodology, T.Zh., A.N.,; validation, T.Zh., A.N. and O.Z.; formal analysis, T.Zh., B.K., Ye.K., A.M. and T.T.; investigation, T.Zh. G.U., Ye.K. and D.R; resources, T.Zh., B.K. and T.T; data curation, T.Zh., T.T., A.Y. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Zh., A.N., A.Y. and G.U.; writing—review and editing, T.Zh., O.Z., G.U. and A.M.; visualization, T.Zh., D.R. and A.M.; supervision, T.Zh.; project administration, Z.Zh.; funding acquisition, T.Zh. and T.T.

Funding

This research was funded by «Qarmet» JSC as part of the co-financing of the funded project: «This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP13268863)».

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Povolotsky, D. Ya. Steel Deoxidation. Moscow: Metallurgy, 1972, 208 p.

- Oiks, G. N. Steel Production (Fundamentals of Theory and Technology). Moscow, 1974.

- Roshchin, V., Roshchin, A. Electrometallurgy and Steel Metallurgy. Litres, 2022. 576 p.

- Umezawa, O.; Nakamoto, M.; Osawa, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kumai, S. Microstructural Refinement of Hyper-Eutectic Al–Si–Fe–Mn Cast Alloys to Produce a Recyclable Wrought Material. Materials Transactions 2005, 46(12), 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleugabulov, S. M.; Nurumgaliev, A. K.; Koishina, G. M.; Aitkenov, N. B. Steel Production from Metal-Bearing Waste. Steel in Translation 2019, 49, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Sarkar, D. Iron-and Steel-Making Process. Introduction to Refractories for Iron-and Steelmaking 2020, 99-145. [CrossRef]

- Dzhulukhidze, A.; Kekelidze, M.; Smolyakov, V.; Ioffe, I.; Khitrik, A.; Volikovsky, O.; Razumov, A. The Use of AMS Alloy as a Precipitation Deoxidizer for Steel X18N19T. In the collection: Production and Application of Manganese Ferroalloys, Tbilisi, 1968, pp. 177-181.

- Medvedev, G. V.; Volkov, S. S.; Lappo, S. I., et al. The Possibility of Producing AMS Alloy from Low-Grade Raw Materials and Its Use in Metallurgy. Steel, 1970, No. 7, pp. 616-618.

- Druinsky, M. I.; Zhuchkov, V. I. Production of Complex Ferroalloys from Mineral Raw Materials of Kazakhstan. Alma-Ata: Nauka, 1988, 208 p.

- Medvedev, G. V.; Takenov, T. D. AMS Alloy. Alma-Ata: Nauka, 1979, 140 p.

- Goan-An-Min; Mchedliashvili, V. A.; Samarin, A. M. The Process of Steel Deoxidation with Complex Alloys of Silicon, Manganese, and Aluminum. Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Technical Sciences, Metallurgy and Fuel, 1962, No. 4, pp. 31-39.

- Kazachkov, I. P., et al. Complex Steel Deoxidizer. Bulletin of the Central Research Institute of Information and Techno-Economic Studies in Ferrous Metallurgy, 1966, No. 17, pp. 17-21.

- Mikiashvili, Sh. M. On the Optimal Composition of the AMS-Type Deoxidizing Alloy. Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the Georgian SSR, 1960, 25(1), pp. 56-58.

- Basson, J. Handbook of Ferroalloys Theory and Technology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Cai, X.; Jiang, H.; Ma, H.; Bao, Y. Steel Research International 2024, 95(1), 2300367. [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Wang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Z. Processes 2024, 12(4), 767. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bao, Y. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials 2024, 31(6), 1249-1262. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, K., Mandal, G. K., & Bandyopadhyay, D. (2015). Theoretical investigation on deoxidation of liquid steel for Fe–Al–Si–O system. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals, 68, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Bakin, I. V.; Ryabchikov, I. V.; Mizin, V. G.; Romashko, A. O.; Usmanov, R. G. On Joint Deoxidation and Refining of Steel with Complex Alloys. Steel in Translation 2023, 53(10), 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, X. A Brief Review of Inclusions in Al Deoxidized Steel. In Slag-Steel Reaction and Control of Inclusions in Al Deoxidized Special Steel. Springer, Singapore, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, G. V.; Lappo, S. I.; Buketov, E. A., et al. Pilot-Scale Experimental Smelting of AMS (Aluminum-Manganese-Silicon) Alloy Using Dzhezdinsky and Karazhal Manganese Ores and Ekibastuz Coal. Transactions of the Chemical-Metallurgical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR, 1969, Vol. 10, pp. 144-151.

- Mukhambetgaliyev, E. K.; Roshchin, V. E.; Baisanov, S. O. Analytical Expressions of the Fe–Si–Al–Mn Metallic System and the Phase Composition of Aluminosilicomanganese. Proceedings of Higher Educational Institutions. Ferrous Metallurgy, 2018, Vol. 7, No. 61, pp. 564-571.

- Tolymbekov, M. Z.; Akhmetov, A. B.; Baisanov, S. O.; Ogurtsov, E. A.; Zhiembaeva, D. M. Steel in Translation 2019, 39(5), 416-419. [CrossRef]

- Nurumgaliyev, A.; Zayakin, O.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Kelamanov, B.; Mukhambetgaliyev, Y. Metallurgist 2023, 67(7-8), 1178-1186. [CrossRef]

- Nurumgaliyev, A.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Shevko, V.; Mukhambetgaliyev, Y.; Kelamanov, B.; Kuatbay, Y.; Badikova, A.; Yerekeyeva, G.; Volokitina, I. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), 7456. [CrossRef]

- Mukhambetgaliyev, Y., Zhuniskaliyev, T., & Baisanov, S. (2021). Research of electrical resistance and beginning softening temperature of high-ash coals for melting of complex Alloy. Metalurgija, 60(3-4), 332-334.

- Zhuniskaliyev, T. Development of Theoretical Foundations and Improvement of the Technology of Production of Complex Alloy of the Fe-Si-Mn-Al Group Using High-Ash Coal and Manganese Ores of Kazakhstan. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Kazakh National Research Technical University named after K.I. Satbayev, 2020.

- Zhuniskaliyev, T., Nurumgaliyev, A., Chekimbayev, A., Kelamanov, B., Kuatbay, Y., Mukhambetgaliyev, Y., … & Abdirashit, A. (2024). Experimental Investigation of the Influence of Phase Compounds on the Friability of Fe-Si-Mn-Al Complex Alloy. Metals, 14(9), 1091.

- Zhuniskaliyev, T., Nurumgaliyev, A., Zayakin, O., Mukhambetgaliyev, Y., Kuatbay, Y., & Mukhambetkaliyev, A. (2020). Investigation and comparison of the softening temperature of manganese ores used for the production of complex ligatures based on Fe-Si-Mn-Al. Metalurgija, 59(4), 521-524.

- Baisanov, S. O. (2017). Production of Complex Ferroalloys Using High-Ash Coals. In Physicochemical Fundamentals of Metallurgical Processes. pp. 20-20.

- Nurumgaliyev, A., Zayakin, O., Zhuniskaliyev, T., Kelamanov, B., & Mukhambetgaliyev, Y. (2023). Smelting of Fe–Si–Mn–Al Complex Alloy Using High-Ash Coal. Metallurgist, 67(7), 1178-1186.

- Nurumgaliyev, A., Zhuniskaliyev, T., Shevko, V., Mukhambetgaliyev, Y., Kelamanov, B., Kuatbay, Y., … & Volokitina, I. (2024). Modeling and development of technology for smelting a complex alloy (ligature) Fe-Si-Mn-Al from manganese-containing briquettes and high-ash coals. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 7456.

- Mukhambetgaliyev, Y. (2022). Research of electrical resistance and temperature of the beginning of softening of charge mixtures for smelting a complex alloy. Metalurgija, 61(3-4), 781-784.

- Mukhambetgaliev, E. K., Esenzhulov, A. B., & Roshchin, V. E. (2018). Alloy production from high-silica manganese ore and high-ash Kazakhstan coal. Steel in Translation, 48, 547-552.

- Mukhambetgaliev, E. K., Roshchin, V. E., & Baisanov, S. O. (2018). Analytical expressions for Fe–Si–Al–Mn metal system and phase composition of alumosilicomanganese. hgbeqŠh “, 61(7), 570.

- Mukhambetgaliev, E. K., Esenzhulov, A. B., & Roshchin, V. E. (2018). PRODUCTION OF COMPLEX ALLOY FROM HIGH-SILICON MANGANESE ORE AND HIGH-ASH COALS OF KAZAKHSTAN. hgbeqŠh “, 61(9), 700.

- Man’ko, V. A.; Emlin, B. I.; Druinsky, M. I. Restoration Processes in the Production of Ferroalloys 1977, 219-222.

- Man’ko, V. A.; et al. Technical Progress of Electrometallurgy of Manganese and Silicon Ferroalloys 1975, 85-88.

-

Coal and Oil Shale Basins and Deposits of Kazakhstan: A Reference Guide. Almaty, 2019, 161 p.

-

Manganese Deposits of Kazakhstan: A Reference Guide // Edited by A. A. Abdulin et al. Almaty: RGP PVC “Information and Analytical Center for Geology and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan,” 1999.

- Alarifi, I. M. Synthetic Engineering Materials and Nanotechnology. Elsevier, 2021.

- Zinovieva, O.; Romanova, V.; Dymnich, E.; Zinoviev, A.; Balokhonov, R. A Review of Computational Approaches to the Microstructure-Informed Mechanical Modelling of Metals Produced by Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2023, 16(19), 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchette, J. A Quick and Reliable Fusion Method for Silicon and Ferrosilicon. Adv. X-Ray Anal. 2002, 45, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Cabric, B.; Danilovic, N.; Janicijevic, A. Testing of Simultaneous Crystallization in a Laboratory Furnace. American Laboratory, 2011, 43(7), pp. 18-19.

- Lovygin, B. A.; Mustaev, G. F.; Balakhnin, I. G. Programmed Automatic Temperature Control in a Tamman Furnace. Refractories 1969, 10(1), 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 1778-70 (ISO 4967-79) Steel. Metallographic Methods for the Determination of Nonmetallic Inclusions.

- Goldstein, J. I.; et al. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis. New York: Springer, 2017.

- Bramfitt, B. L.; Benscoter, A. O. Metallographer’s Guide: Practices and Procedures for Irons and Steels. ASM International, 2001.

- GOST 5640-2020 Steel. Metallographic Method for Assessing the Microstructure of Flat Steel Rolled Products.

- Holappa, L.; Nurmi, S. Thermodynamic Constraints and Prospects for Intensified Steel Deoxidation. Steel Research International 2024, 2400556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamanyuk, S. B.; Zyuban, N. A.; Rutskiy, D. V.; Babin, G. V.; Kirilichev, M. V. Study of the Effect of Steel Deoxidation Regime on the Formation and Distribution of Sulfide Inclusions and Mechanical Properties. Proceedings of Volgograd State Technical University, 2019, (2), pp. 81-88.

- Serov, G. V.; Komissarov, A. A.; Tikhonov, S. M.; et al. Effect of Deoxidation on Low-Alloy Steel Nonmetallic Inclusion Composition. Refract Ind Ceram 2019, 59, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorovich, K. V.; Garber, A. K. Analysis of the Complex Deoxidation of Carbon Steel Melts. Russ. Metall. 2011, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).