Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

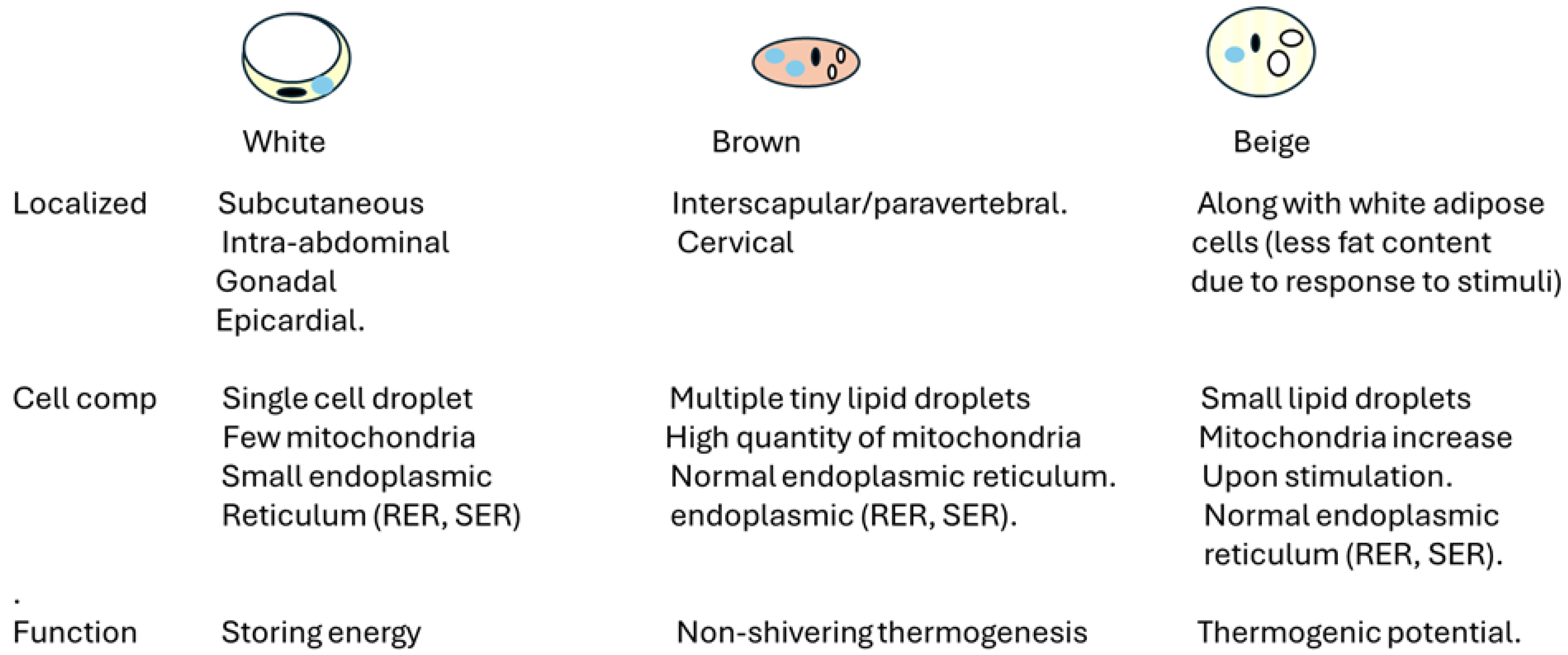

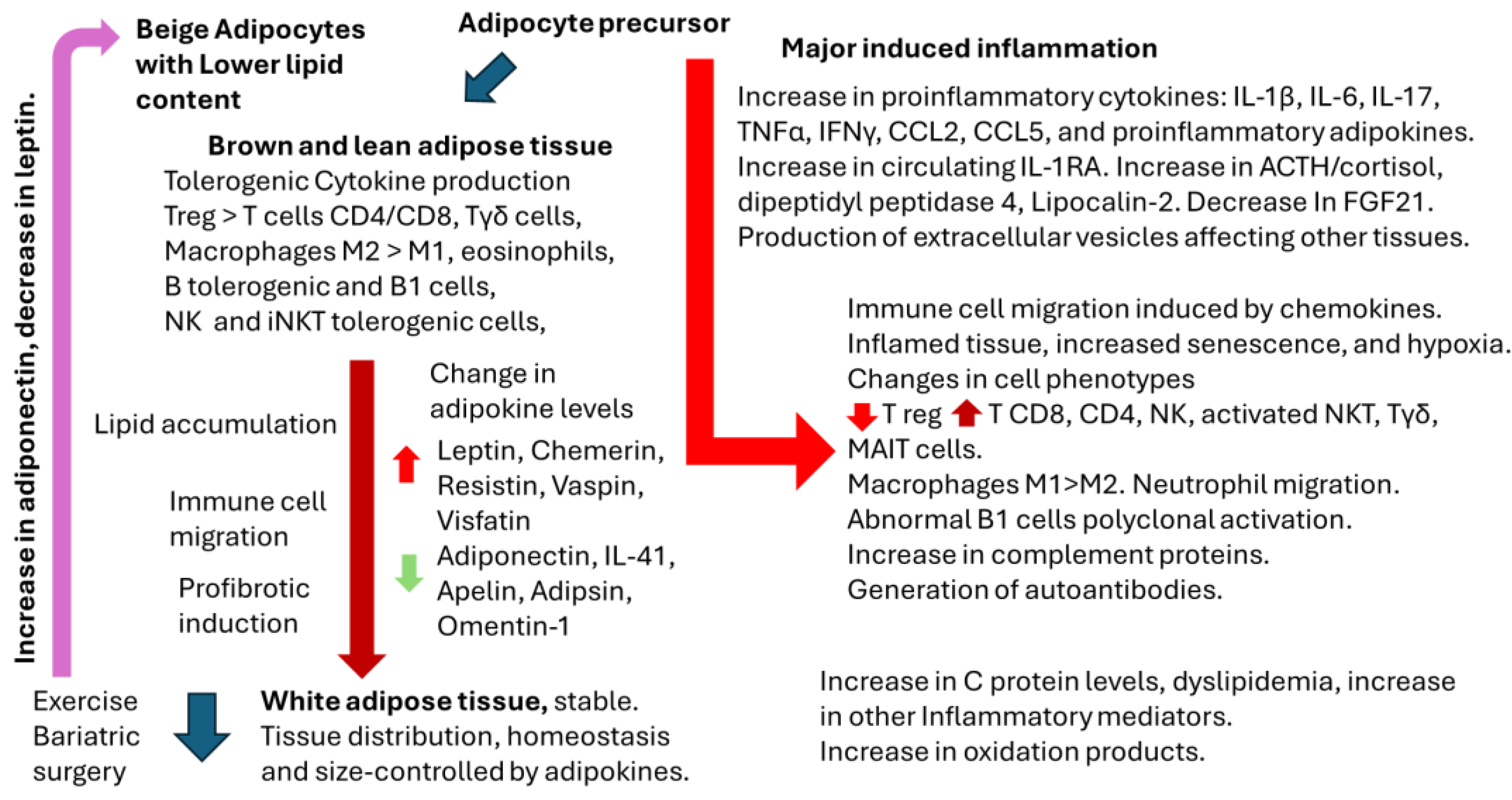

2. Overview of Adipose Tissue Physiology and Physiopathology

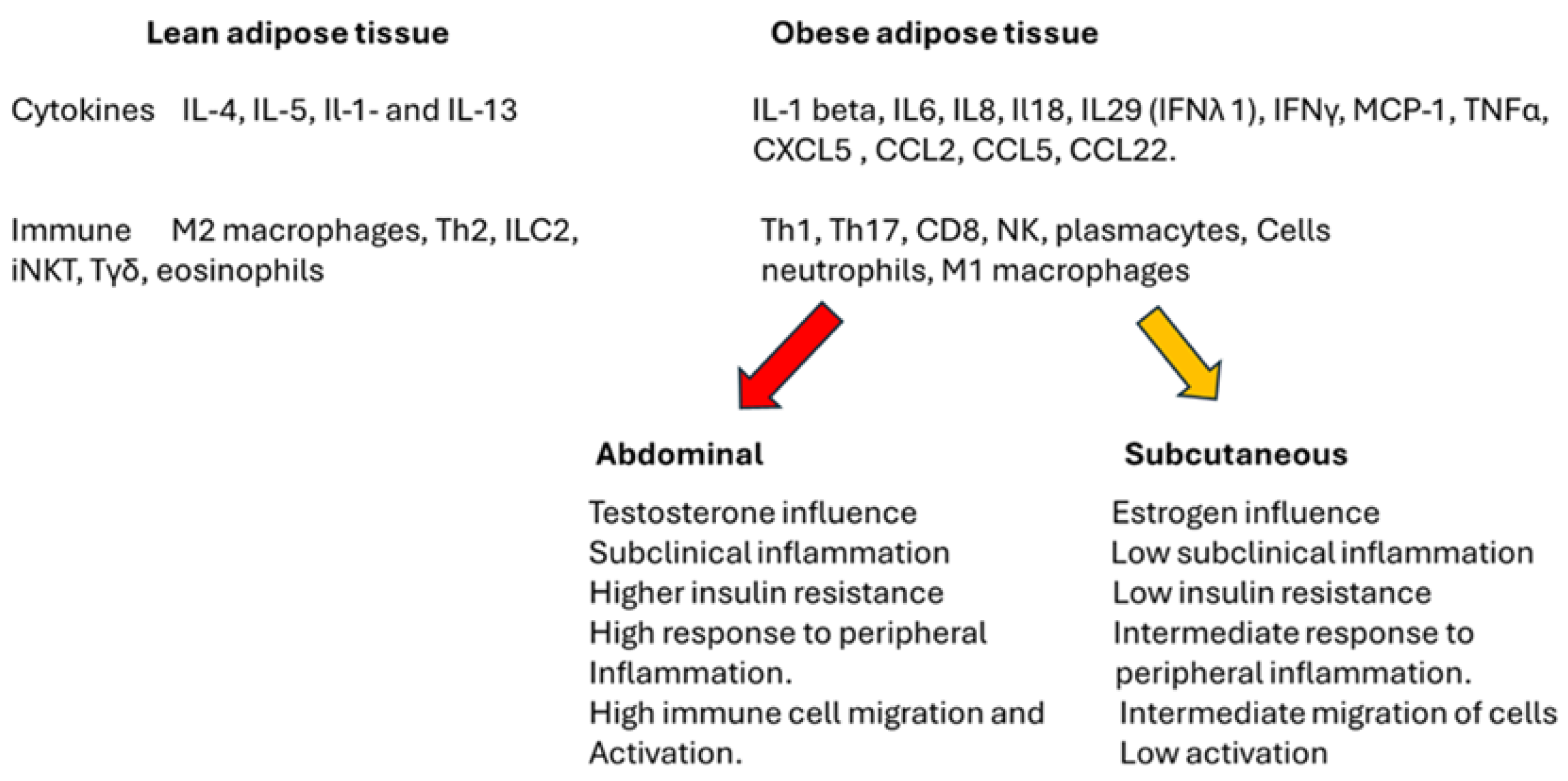

2.1. Adipose Tissue, Gender, and Immune Response

2.2. Adipocytes as Antigen-Presenting Cells

2.3. Adipocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

3. Obesity and Infectious Diseases

4. Impact of Obesity on Vaccination

4.1. Inactivated or Subunit Vaccines

4.2. Live-attenuated vaccines

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/basics/explaining-how-vaccines-work.html. Assessed December 8, 2024.

- Petrakis, D.; Margină, D.; Tsarouhas, K.; Tekos, F.; Stan, M.; Nikitovic, D.; et al. Obesity - a risk factor for increased COVID-19 prevalence, severity, and lethality. Mol Med Rep. 2020 Jul;22(1):9-19. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Pisaturo, M.; Zollo, V.; Martini, S.; Maggi, P.; Numis, F.G., et al. Obesity as a Risk Factor of Severe Outcome of COVID-19: A Pair-Matched 1:2 Case-Control Study. J Clin Med. 2023 Jun 15;12(12):4055. [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.C.; Geerling, E.; Pinto, A.K. Impact of Obesity on Vaccination to SARS-CoV-2. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 20; 13:898810. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, C.; Retnakumar, S.V.; Bayry, J. Obesity negatively impacts maintenance of antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Jul 18;4(7):101117. [CrossRef]

- van der Klaauw, A. A.; Horner, E. C.; Pereyra-Gerber, P.; Agrawal, U.; Foster, W. S.; et al. Accelerated waning of the humoral response to COVID-19 vaccines in obesity. Nature Med, 2023; 29(5), 1146–1154. [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, M.; Keeshan, A.; Gravel, C.A.; Langlois, M.A, Cooper CL. Obesity does not influence SARS-CoV-2 humoral vaccine immunogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2024 Nov 18;9(1):226. [CrossRef]

- Zwick, R.K.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F,; Horsley, V.; Plikus, M.V. Anatomical, Physiological, and Functional Diversity of Adipose Tissue. Cell Metab. 2018 Jan 9;27(1):68-83. [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, C.E.; Spalding, K.L. White adipocyte dysfunction and obesity-associated pathologies in humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024; 25, 270–289. [CrossRef]

- Richard, A.J.; White, U.; Elks, C.M, et al. Adipose Tissue: Physiology to Metabolic Dysfunction. [Updated 2020 Apr 4]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555602/.

- Gavin, K.M.; Bessesen D.H. Sex Differences in Adipose Tissue Function. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020 Jun;49(2):215-228. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liu, M. Adiponectin: friend or foe in obesity and inflammation. Medical Review 2022, 2(4), 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Aiello, G.; Mansilla Di Martino, E.; Campaci, D.; Muthanna, F.M.S.; Lombardo, M. The Role of Adipose Tissue and Nutrition in the Regulation of Adiponectin. Nutrients. 2024 Jul 26;16(15):2436. [CrossRef]

- Dare, A.; Chen, S. Y. Adipsin in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Vascular pharmacology, 2024; 154, 107270. [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Huang, H.; Zhu, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xia, Z. Adipokines and their potential impacts on susceptibility to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetes. Lipids health dis, 2024; 23(1), 372. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Masri, B.; Daviaud, D.; Gesta, S.; Guigné, C.; Mazzucotelli, A.; et al. Apelin, a newly identified adipokine up-regulated by insulin and obesity. Endocrinology, 2005; 146(4), 1764–1771. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L; Lu, X.; Danser, A.H.J.; Verdonk. K. The Role of Chemerin in Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease: A Literature Review of Its Physiology and Pathology from a Nutritional Perspective. Nutrients. 2023 Jun 25;15(13):2878. [CrossRef]

- Münzberg, H.; Heymsfield, S. B.; Berthoud, H. R.; Morrison, C. D. History and future of leptin: Discovery, regulation and signaling. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 2024; 161, 156026. [CrossRef]

- Perakakis, N.; Mantzoros, C. S. Evidence from clinical studies of leptin: current and future clinical applications in humans. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 2024; 161, 156053. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Zheng, M.; Shen, H. Meteorin-like/Metrnl, a novel secreted protein implicated in inflammation, immunology, and metabolism: A comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies. Front Immunol, 2023; 14, 1098570. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; He, M.; Peng, Y.; Xia, X. Homotherapy for heteropathy: Interleukin-41 and its biological functions. Immunology 2024, 173(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sena, C.M. Omentin: A Key Player in Glucose Homeostasis, Atheroprotection, and Anti-Inflammatory Potential for Cardiovascular Health in Obesity and Diabetes. Biomedicines. 2024 Jan 26;12(2):284. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Kant, S.; Pandey, S.; Ehtesham, N. Z. Resistin in metabolism, inflammation, and disease. The FEBS journal, 2020; 287(15), 3141–3149. [CrossRef]

- Radzik-Zając, J.; Wytrychowski, K.; Wiśniewski, A.; Barg, W. The role of the novel adipokines vaspin and omentin in chronic inflammatory diseases. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;29(1):48-52. [CrossRef]

- Dimova, R.; Tankova, T. The role of vaspin in the development of metabolic and glucose tolerance disorders and atherosclerosis. BioMed research international, 2015, 823481. [CrossRef]

- Adeghate, E. Visfatin: structure, function and relation to diabetes mellitus and other dysfunctions. Current Med Chem, 2008; 15(18), 1851–1862. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, Y. CCL2-CCR2 signaling axis in obesity and metabolic diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2024 Apr;239(4):e31192. [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. C.; Lu, C. H.; Chien, H. C.; Tian, Y. F.; Hsieh, P. S. Adipose Tissue-Derived CCL5 Enhances Local Pro-Inflammatory Monocytic MDSCs Accumulation and Inflammation via CCR5 Receptor in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Inter J Mol Sci, 2022; 23(22), 14226. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hu, R.; Park, J.; Xiong, S.; Wang, Z.; Qian, Y.; et al. Macrophage-derived chemokine CCL22 establishes local LN-mediated adaptive thermogenesis and energy expenditure. Science Advances, 2024; 10(26), eadn5229. [CrossRef]

- Wueest, S.; Konrad, D. The role of adipocyte-specific IL-6-type cytokine signaling in FFA and leptin release. Adipocyte. 2018;7(3):226-228. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Chiu, C.J.; Hsing, C.H.; Hsu Y.H. Interferon Family Cytokines in Obesity and Insulin Sensitivity. Cells. 2022 Dec 14;11(24):4041. [CrossRef]

- Sewter, C. P.; Digby, J. E.; Blows, F.; Prins, J.; O'Rahilly, S. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor-alpha release from human adipose tissue in vitro. J Endocrinol, 1999; 163(1), 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. Reappraisal of Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Obesity. Adv Exper Med Biol, 2024; 1460, 297–327. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Momen Maragheh, S.; Aghazadeh, A.; Mehrjuyan, S. R.; Hussen, B. M.; Abdoli Shadbad, M.; Dastmalchi, N.; Safaralizadeh, R. Interleukin-1 in obesity-related low-grade inflammation: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. International Immunopharmacol, 2021; 96, 107765. [CrossRef]

- Hofwimmer, K.; de Paula Souza, J.; Subramanian, N. et al. IL-1β promotes adipogenesis by directly targeting adipocyte precursors. Nat Commun 2024; 15, 7957. [CrossRef]

- Juge-Aubry, C. E.; Somm, E.; Giusti, V.; Pernin, A.; Chicheportiche, R.; Verdumo, C.; et al. Adipose tissue is a major source of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: upregulation in obesity and inflammation. Diabetes, 2003; 52(5), 1104–1110. [CrossRef]

- Frühbeck, G; Catalán, V.; Ramírez, B.; Valentí, V.; Becerril, S.; et al. Serum Levels of IL-1 RA Increase with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes in Relation to Adipose Tissue Dysfunction and are Reduced After Bariatric Surgery in Parallel to Adiposity. J Inflamm Res. 2022 Feb 24;15:1331-1345. [CrossRef]

- Barchetta, I.; Cimini, F.A.; Dule, S.; Cavallo, M.G. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP4) as A Novel Adipokine: Role in Metabolism and Fat Homeostasis. Biomedicines. 2022 Sep 16;10(9):2306. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Ramos, D.; Mehta, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C. A. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 and Browning of White Adipose Tissue. Frontiers in physiology, 2019; 10, 37. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Cortez, Y. A.; Barragán-Bonilla, M. I.; Mendoza-Bello, J. M.; González-Calixto, C.; Flores-Alfaro, E.; Espinoza-Rojo, M. Interplay of retinol binding protein 4 with obesity and associated chronic alterations. Molecular Medic rep, 2022; 26(1), 244. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Leroith, D.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Chen, X. The Role of Lipocalin 2 in the Regulation of Inflammation in Adipocytes and Macrophages, Molecular Endocrinology, 2008; 22, (6), 1416–1426. [CrossRef]

- Moschen, A. R.; Adolph, T. E.; Gerner, R. R.; Wieser, V.; Tilg, H. Lipocalin-2: a master mediator of intestinal and metabolic inflammation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017; 28, 388–397.

- Lee, M. J. Transforming growth factor beta superfamily regulation of adipose tissue biology in obesity. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease, 2018; 1864(4 Pt A), 1160–1171. [CrossRef]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Verde, L.; Vetrani, C.; Barrea, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. Obesity: a gender-view. J Endocrinol Invest. 2024 Feb;47(2):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Tramunt, B.; Smati, S.; Grandgeorge, N.; Lenfant, F.; Arnal, J.F.; Montagner, A, et al. Sex differences in metabolic regulation and diabetes susceptibility. Diabetologia. 2020;63(3):453–461. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Fuentes, T.; Delgado-Guerra, S.; Guadalupe-Grau, A.; Olmedillas, H.; Santana, A.; Ponce-Gonzalez, J. G.; Dorado, C.; Calbet, J. A. Gender dimorphism in skeletal muscle leptin receptors, serum leptin and insulin sensitivity. PloS one, 2008; 3(10), e3466. [CrossRef]

- Rak, A.; Mellouk, N.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Adiponectin and resistin: potential metabolic signals affecting hypothalamo-pituitary gonadal axis in females and males of different species. Reproduction (Cambridge, England), 2017; 153(6), R215–R226. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rebordelo, E.; Cunarro, J.; Perez-Sieira, S.; Seoane, L.M.; Diéguez, C.; Nogueiras, R.; Tovar, S. Regulation of Chemerin and CMKLR1 Expression by Nutritional Status, Postnatal Development, and Gender. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Sep 25;19(10):2905. [CrossRef]

- Kautzky-Willer, A.; Leutner, M.; Harreiter, J. Sex differences in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2023; 66(6), 986–1002. [CrossRef]

- Koceva, A.; Herman, R.; Janez, A.; Rakusa, M.; Jensterle, M. Sex- and Gender-Related Differences in Obesity: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7342. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Chen, L.; Song, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Association between systemic immune-inflammatory index and systemic inflammatory response index with body mass index in children and adolescents: a population-based study based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-2020. Front Endocrinol 2024, 15, 1426404. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Iwasaki, A. Sex differences in postacute infection syndromes. Science Translational Medicine, 2024; 16(773), eado2102. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Ning, Z.; Huang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Tan, X.; Pan, Y.; et al. Analysis of sex-biased gene expression in a Eurasian admixed population. Briefings in bioinformatics, 2024; 25(5), bbae451. [CrossRef]

- Persons, P. A.; Williams, L.; Fields, H.; Mishra, S.; Mehta, R. Weight gain during midlife: Does race/ethnicity influence risk? Maturitas, 2024; 185, 108013. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016; 16:626–38. 6: 16. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, N.M.; Chen, H.C.; Lechner, M.G.; Su M.A. Sex differences in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022 40: 75-94. [CrossRef]

- Popotas, A.; Casimir, G. J.; Corazza, F.; Lefèvre, N. Sex-related immunity: could Toll-like receptors be the answer in acute inflammatory response? Frontiers in immunology, 2024; 15, 1379754. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Sha, S.; Huang, J. Peng, J.; et al. (). Tlr9 deficiency in B cells leads to obesity by promoting inflammation and gut dysbiosis. Nature comm, 2024; 15(1), 4232. [CrossRef]

- Hamerman, J. A.; Barton, G. M. The path ahead for understanding Toll-like receptor-driven systemic autoimmunity. Current opinion in immunology, 2024; 91, 102482. [CrossRef]

- Layug, P. J.; Vats, H.; Kannan, K.; Arsenio, J. Sex differences in CD8+ T cell responses during adaptive immunity. WIREs mechanisms of disease, 2024; 16(5), e1645. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, K.S.; Jiwrajka, N.; Lovell, C.D.; Toothacre, N.E.; Anguera, M.C. The conneXion between sex and immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024 Jul;24(7):487-502. [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Nov 29;23(23):14982. [CrossRef]

- Trim, W.V.; Lynch, L. Immune and non-immune functions of adipose tissue leukocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 22, 371–386 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yang, X.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, J.; Qian, S.; Tang, Q.; He, R.; Li, X. Large adipocytes function as antigen-presenting cells to activate CD4(+) T cells via upregulating MHCII in obesity. International journal of obesity 2016; (2005), 40(1), 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.C.; Damen, M.S.M.A.; Alarcon, P.C.; Sanchez-Gurmaches, J.; Divanovic, S. Inflammation and Immunity: From an Adipocyte's Perspective. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019 Aug;39(8):459-471. [CrossRef]

- Castoldi, A.; Sanin, D. E.; van Teijlingen Bakker, N.; Aguiar, C. F.; de Brito Monteiro, L.; et al. Metabolic and functional remodeling of colonic macrophages in response to high-fat diet-induced obesity. iScience, 2023; 26(10), 107719. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jia, X.; Meng, G.; et al. Obesity Reshapes Visceral Fat-Derived MHC I Associated-Immunopeptidomes and Generates Antigenic Peptides to Drive CD8+ T Cell Responses. iScience, 2020; 23(4), 100977. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Iizuka, M.; Majima, M.; Ohwa, C.; Hattori, A.; Van Kaer, L.; Iwabuchi, K. Adipose invariant NKT cells interact with CD1d-expressing macrophages to regulate obesity-related inflammation. Immunology, 2022; 165(4), 414–427. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Iwabuchi, K. Contribution of NKT cells and CD1d-expressing cells in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Frontiers in immunology, 2024; 15, 1365843. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.J.; Murphy, K.E.; Fernandez, M.L. Impact of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome on Immunity. Adv Nutr. 2016 Jan 15;7(1):66-75. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021 Mar 1;320(3):C375-C391. [CrossRef]

- Valentine, Y.; Nikolajczyk, B. S. T cells in obesity-associated inflammation: The devil is in the details. Immunological reviews, 2024; 324(1), 25–41. [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lund, PK. Role of intestinal inflammation as an early event in obesity and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul;14(4):328-33. [CrossRef]

- Brotfain, E.; Hadad, N.; Shapira, Y.; Avinoah, E.; Zlotnik, A.; Raichel, L.; Levy, R. Neutrophil functions in morbidly obese subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015 Jul;181(1):156-63. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Casado, G.; Jimenez-Gonzalez, A.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; González-Mesa, E.; Murri, M.; Ortega-Gomez, A. Neutrophils as indicators of obesity-associated inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2024 Nov 29:e13868. [CrossRef]

- Shantaram, D.; Hoyd, R.; Blaszczak, A. M.; Antwi, L.; Jalilvand, A.; Wright, V. P.; et al. Obesity-associated microbiomes instigate visceral adipose tissue inflammation by recruitment of distinct neutrophils. Nature Comm 2024, 15(1), 5434. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chakarov, S. Eosinophils in obesity and obesity-associated disorders. Discov Immunol. 2023 Nov 14;2(1):kyad022. [CrossRef]

- Divoux, A.; Moutel, S.; Poitou, C.; Lacasa, D.; Veyrie. N.; Aissat, A.; Arock, M.; Guerre-Millo, M.; Clément, K. Mast cells in human adipose tissue: link with morbid obesity, inflammatory status, and diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Sep;97(9): E1677-85. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Skrede, S.; Haugstøyl, M.; López, M.; Fernø, J. Peripheral and central macrophages in obesity. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2023; 14, 1232171. [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, C.; Piette, J.; Legrand-Poels, S. Unravelling metabolic factors impacting iNKT cell biology in obesity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024 Oct; 228:116436. [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Abe, S.; Kato, R.; Ikuta, K. Insights into the heterogeneity of iNKT cells: tissue-resident and circulating subsets shaped by local microenvironmental cues. Front Immunol. 2024 Feb 19;15:1349184. [CrossRef]

- Canter, R.J.; Judge, S.J.; Collins, C.P.; Yoon, D.J.; Murphy, W.J. Suppressive effects of obesity on NK cells: is it time to incorporate obesity as a clinical variable for NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy regimens? J Immunother Cancer. 2024 Mar 13;12(3):e008443. [CrossRef]

- De Barra, C.; O'Shea, D.; Hogan, A. E. NK cells vs. obesity: A tale of dysfunction & redemption. Clinical immunology 2023, 255, 109744. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E.L.; Shchukina, I.; Asher, J.L.; Sidorov, S.; Artyomov, M.N.; Dixit, V.D. Ketogenesis activates metabolically protective γδ T cells in visceral adipose tissue. Nat Metab. 2020 Jan;2(1):50-61. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Romero, M.; Blomberg, B.B. Similarities in B Cell Defects between Aging and Obesity. J Immunol. 2024 Nov 15;213(10):1407-1413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Litchfield, B.; Wu, H. Adipose tissue lymphocytes and obesity. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2024 Jan;4(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Meher, A.K.; McNamara, C.A. B-1 lymphocytes in adipose tissue as innate modulators of inflammation linked to cardiometabolic disease. Immunol Rev. 2024 Jul;324(1):95-103. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Nikolajczyk, B. S. Tissue Immune Cells Fuel Obesity-Associated Inflammation in Adipose Tissue and Beyond. Frontiers in immunology, 2019; 10, 1587. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.; Liu, L. F.; Lamendola, C.; Shen, L.; Morton, J.; Rivas, H.; et al. T-cell profile in adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in humans. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 2014; 34(12), 2637–2643. [CrossRef]

- Zi, C.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; He, L. The role of Th17 cells in endocrine organs: Involvement of the gut, adipose tissue, liver and bone. Front in Immunol , 2023; 13, 1104943. [CrossRef]

- Kochumon, S.; Hasan, A.; Al-Rashed, F.; Sindhu, S.; Thomas, R.; Jacob, T.; et al. Increased Adipose Tissue Expression of IL-23 Associates with Inflammatory Markers in People with High LDL Cholesterol. Cells, 2022; 11(19), 3072. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrini, E.; Cella, M.; McCartney, S.A.; Fuchs, A.; Abumrad, N.A.; et al. Association between specific adipose tissue CD4+ T-cell populations and insulin resistance in obese individuals. Gastroenterology. 2013 Aug;145(2):366-74.e1-3. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. The roles of T cells in obese adipose tissue inflammation. Adipocyte, 2021; 10(1), 435–445. [CrossRef]

- Delacher, M.; Schmidleithner, L.; Simon, M.; Stüve, P.; Sanderink, L.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; et al. The effector program of human CD8 T cells supports tissue remodeling. J Exp Med, 2024; 221(2), e20230488. [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, I.; Pingris, K.; Poitou, C.; Bessoles, S.; Venteclef, N.; Kiaf, B.; et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cell alterations in obese and type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest, 2015; 125(4), 1752–1762. [CrossRef]

- Kedia-Mehta, N.; Hogan, A. E. MAITabolism2 - the emerging understanding of MAIT cell metabolism and their role in metabolic disease. Front Immunol 2022; 13, 1108071. [CrossRef]

- Sage, P. T.; Sharpe, A. H. T follicular regulatory cells in the regulation of B cell responses. Trends in immunology, 2015; 36(7), 410–418. [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, A. D.; Ma, F.; Wong, Y. Y.; Sun, R.; Pellegrini, M.; O'Sullivan, T. E. Single-cell sequencing of human white adipose tissue identifies new cell states in health and obesity. Nature immunology, 2021; 22(5), 639–653. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Vazquez, T.; Blomberg, B. B. Obesity induces pro-inflammatory B cells and impairs B cell function in old mice. Mechanisms of ageing and development, 2017; 162, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Park, M. J.; Kwok, S. K.; Lee, S. H.; Kim, E. K.; Park, S. H.; Cho, M. L. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce expansion of interleukin-10-producing regulatory B cells and ameliorate autoimmunity in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell transplantation, 2015; 24(11), 2367–2377. [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Q.; Li, B.; Xin, H.; et al. Novel perspectives on autophagy-oxidative stress-inflammation axis in the orchestration of adipogenesis. Front Endocrinol, 2024, 15, 1404697. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, N.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Xu, C. The differentiation courses of the Tfh cells: a new perspective on autoimmune disease pathogenesis and treatment. Bioscience reports, 2024; 44(1), BSR20231723. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chua, S. Jr. Leptin Function and Regulation. Compr Physiol. 2017 Dec 12;8(1):351-369. 3: 12;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, K.; MacIver, N. J. The Role of the Adipokine Leptin in Immune Cell Function in Health and Disease. Front Immunol 2021, 11, 622468. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liang, K.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; et al. The metabolic hormone leptin promotes the function of TFH cells and supports vaccine responses. Nat Commun. 2021 May 24;12(1):3073. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sohn, J.H.; Han, S.M.; Park, Y.J.; Huh, J.Y.; Choe, S.S.; Kim, J.B. Adipocytes Are the Control Tower That Manages Adipose Tissue Immunity by Regulating Lipid Metabolism. Front Immunol. 2021 Jan 28; 11:598566. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.R.; Beck, M.A.; Alwarawrah, Y.; MacIver NJ. Emerging mechanisms of obesity-associated immune dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2024; 20, 136–148. [CrossRef]

- Soták, M.; Clark, M.; Suur, B.E.; Börgeson, E. Inflammation and resolution in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2025; 21, 45–61. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. The pathophysiology of visceral adipose tissues in cardiometabolic diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024 Apr;222:116116. [CrossRef]

- McTavish, P.V.; Mutch, D.M.. Omega-3 fatty acid regulation of lipoprotein lipase and FAT/CD36 and its impact on white adipose tissue lipid uptake. Lipids Health Dis. 2024 Nov 20;23(1):386. [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.B.; Figueiredo, N.; Kattah, F.M.; Oliveira, E.S.; Horst, M.A.; Dâmaso, A.R.; et al. Serum Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Patterns in Severe Obesity: A Preliminary Investigation in Women. Biomedicines. 2024 Oct 3;12(10):2248. [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Gluscevic, M.; Baker, D.J.; Laberge, R.M.; Marquess, D.; Dananberg, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent cells: an emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017 Oct;16(10):718-735. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Guo, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, L, et al. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target. 2023;8(1):200. [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, K.; Sano, M. T Cell Immunosenescence in Aging, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Cells. 2021 Sep 15;10(9):2435. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, C.; Han, Y.; Gu, Z.; Sun, C. Immunosenescence, aging and successful aging. Front Immunol. 2022 Aug 2;13:942796. [CrossRef]

- Shimi, G.; Sohouli, M.H.; Ghorbani, A.; Shakery, A.; Zand, H. The interplay between obesity, immunosenescence, and insulin resistance. Immun Ageing. 2024 Feb 5;21(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Garcia, D.; Blomberg, B.B. B Cell Immunosenescence. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Oct 6;36:551-574. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J.V.; Moreno, D.; Garcia, A.H.; De Sanctis, J.B. Metabolic syndrome and asthma. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2014 Jan;8(1):60-6. [CrossRef]

- Kudlova, N.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Hajduch, M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 10;23(8):4168. [CrossRef]

- Valentino, T.R.; Chen, N.; Makhijani, P.; Khan, S.; Winer, S.; Revelo, X.S.; Winer, DA. The role of autoantibodies in bridging obesity, aging, and immunosenescence. Immun Ageing. 2024 Nov 30;21(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Q. Adipose Extracellular Vesicles: Messengers from and to Macrophages in Regulating Immunometabolic Homeostasis or Disorders. Front Immunol. 2021 May 24; 12:666344. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, H.Y.; Chen, M.; Xu, K.; Chen, B. The impact of obesity on adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021 Dec;78(23):7275-7288. [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, J.; Berg, V.; Vaittinen, M.; Impola, U.; Mustonen, A. M.; Männistö, V.; et al. Increased secretion of adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles is associated with adipose tissue inflammation and the mobilization of excess lipid in human obesity. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22(1), 623. [CrossRef]

- Rakib, A.; Kiran, S.; Mandal, M.; Singh, U. P. (). MicroRNAs: a crossroad that connects obesity to immunity and aging. Immunity & ageing 2022; 19(1), 64. [CrossRef]

- Mendivil-Alvarado, H.; Sosa-León, L.A.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H. Malnutrition and Biomarkers: A Journey through Extracellular Vesicles. Nutrients. 2022 Feb 27;14(5):1002. [CrossRef]

- Leocádio, P.C.L.; Oriá, R.B.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E.; Alvarez-Leite, J.I. Obesity: More Than an Inflammatory, an Infectious Disease? Front Immunol. 2020 Jan 14; 10:3092. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, G.; Liccardi, A.; Graziadio, C.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Colao, A Obesity and infectious diseases: pathophysiology and epidemiology of a double pandemic condition. Int J Obes 2022; 46, 449–465. [CrossRef]

- Cristancho, C.; Mogensen, K.M.; Robinson, M.K. Malnutrition in patients with obesity: An overview perspective. Nutr Clin Pract. 2024 Dec;39(6):1300-1316. [CrossRef]

- Crespo, F.I.; Mayora, S.J.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Martínez, W.Y.; Zabaleta-Lanz, M.E.; Toro, F.I.; Deibis, L.H.; García A.H. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Venezuelan Pediatric Patients-A Single Center Prospective Observational Study. Biomedicines. 2023 May 9;11(5):1409. [CrossRef]

- García, A.H.; Crespo, F.I.; Mayora, S.J.; Martinez, W.Y.; Belisario, I.; Medina, C.; De Sanctis, J.B. Role of Micronutrients in the Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pediatric Patients. Immuno 2024, 4, 211-225. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.; Luna, M.; Pereira, S. E.; Saboya, C. J.; Ramalho, A. Impairment of Vitamin D Nutritional Status and Metabolic Profile Are Associated with Worsening of Obesity According to the Edmonton Obesity Staging System. Intl J Mol Sci, 2022; 23(23), 14705. [CrossRef]

- Bennour, I.; Haroun, N.; Sicard, F.; Mounien, L.; Landrier, J.-F. Vitamin D and Obesity/Adiposity—A Brief Overview of Recent Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2049. [CrossRef]

- Keto, J.; Feuth, T.; Linna, M.; Saaresranta, T. Lower respiratory tract infections among newly diagnosed sleep apnea patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2023 Sep 8;23(1):332. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Yang, C.A.; Ojuri, V.; Buckley, K.; Bedi, B.; Musonge-Effoe, J.; Soibi-Harry, A.; La-hiri, C.D. Sex Differences in Metabolic Disorders of Aging and Obesity in People with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2024 Nov 21;22(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Cancelier, A.C.L.; Schuelter-Trevisol, F.; Trevisol, D.J.; Atkinson, R.L. Adenovirus 36 infection and obesity risk: current understanding and future therapeutic strategies. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Mar;17(2):143-152. [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.; Geerling, E.; Pinto, A.K.; Miraj, I.; Weger-Lucarelli, J. Immune response to arbovirus infection in obesity. Front Immunol. 2022 Nov 18; 13:968582. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jennings, J.; Gong, Y.; Sang, Y. Viral Infections and Interferons in the Development of Obesity. Biomolecules. 2019 Nov 12;9(11):726. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P.; Chan, K.R.; Rivino, L.; Yacoub, S. The association of obesity and severe dengue: possible pathophysiological mechanisms. J Infect. 2020 Jul;81(1):10-16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chiu, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Huang, C.H.; Wang, W.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin C.Y. Obesity as a clinical predictor for severe manifestation of dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Jul 31;23(1):502. [CrossRef]

- Molokwu, J. C.; Penaranda, E.; Lopez, D. S.; Dwivedi, A.; Dodoo, C.; & Shokar, N. Association of Metabolic Syndrome and Human Papillomavirus Infection in Men and Women Residing in the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention, 2017; 26(8), 1321–1327. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, Z. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Cervical Human Papillomavirus Incident and Persistent Infection. Medicine, 2016; 95(9), e2905. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.S.; Jun, B.G.; Yi, S.W. Impact of diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;28(4):773-789. [CrossRef]

- Markakis, K.; Tsachouridou, O.; Georgianou, E.; Pilalas, D.; Nanoudis, S.; Metallidis, S. Weight Gain in HIV Adults Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Life (Basel, Switzerland), 2024; 14(11), 1367. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, C.; Castillo, M.; Carrillo, K.; Tapia, C.V.; Valderrama, G.; Maquilón, C.; Toro-Ascuy, D.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Fuenzalida, L.F. Overnutrition as a risk factor for more serious respiratory viral infections in children: A retrospective study in hospitalized patients. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2023 Aug-Sep;70(7):476-483. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, M.; Shi, L.; Monick, M. M.; Hunninghake, G. W.; Look, D. C. Specific inhibition of type I interferon signal transduction by respiratory syncytial virus. American Journal of Respiratory Cell And Molecular Biology, 2004; 30(6), 893–900. [CrossRef]

- Mîndru, D. E.; Țarcă, E.; Adumitrăchioaiei, H.; Anton-Păduraru, D. T.; Ștreangă, V.; Frăsinariu, O. E.; Sidoreac, A.; Stoica, C.; Bernic, V.; Luca, A. C. Obesity as a Risk Factor for the Severity of COVID-19 in Pediatric Patients: Possible Mechanisms-A Narrative Review. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 2024; 11(10), 1203. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Hong, W.; Moon, Y. Obesity-compromised immunity in post-COVID-19 condition: a critical control point of chronicity. Front Immunol, 2024; 15, 1433531. [CrossRef]

- Miron, V. D.; Drăgănescu, A. C.; Pițigoi, D.; Aramă, V.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Săndulescu, O. The Impact of Obesity on the Host-Pathogen Interaction with Influenza Viruses - Novel Insights: Narrative Review. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targets and therapy, 2024; 17, 769–777. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; Huang, KC. Association between metabolic factors and chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jun 21;20(23):7213-6. [CrossRef]

- Hornung, F.; Rogal, J.; Loskill, P.; Löffler, B.; Deinhardt-Emmer, S. The Inflammatory Profile of Obesity and the Role on Pulmonary Bacterial and Viral Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 26;22(7):3456. [CrossRef]

- Hales, C.; Burnet, L.; Coombs, M.; Collins, A. M.; Ferreira, D. M. Obesity, leptin and host defence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: the case for more human research. European Respiratory Review, 2022; 231(165), 220055. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, H.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, L. Correlation between body mass index and gender-specific 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024 Oct 8;11:1462637. [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.J.; Rutala, W.A.; Samsa, G.P.; Santimaw, J.E.; Lemon, S.M. Obesity as a predictor of poor antibody response to hepatitis B plasma vaccine. JAMA. 1985 Dec 13;254(22):3187-9.

- Callahan, S.T.; Wolff, M.; Hill, H.R.; Edwards, K.M.; NIAID Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit (VTEU) Pandemic H1N1 Vaccine Study Group. Impact of body mass index on immunogenicity of pandemic H1N1 vaccine in children and adults. J Infect Dis. 2014 Oct 15;210(8):1270-4. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Mathew, S.M.; Giles, L.C.; Pena, A.S.; Barr, I.G.; Richmond, P.C.; Marshall, H.S. A Prospective Study Investigating the Impact of Obesity on the Immune Response to the Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine in Children and Adolescents. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Apr 29;10(5):699. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, P.A.; Paich, H.A.; Handy, J.; Karlsson, E.A.; Hudgens, M.G.; Sammon, A.B.; Holland, L.A.; Weir, S; Noah, T.L.; Beck, M.A. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes 2012. 36:1072–1077. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Kaur, B.P.; Seth, D.; Pansare, M.V.; Kamat, D.; McGrath, E, et al Can Obesity Alter the Immune Response to Childhood Vaccinations? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2019, Volume 143, Issue 2, AB299.

- Huang, J.; Kaur, B.; Farooqi, A.; Miah, T.; McGrath, E.; et al. Elevated Glycated Hemoglobin Is Associated with Reduced Antibody Responses to Vaccinations in Children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2020 Dec;33(4):193-198. [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Merikanto, I.; Delale, E. A.; Bjelajac, A.; Yordanova, J.; Chan, R. N. Y.; et al. Associations between obesity, a composite risk score for probable long COVID, and sleep problems in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated individuals. International journal of obesity 2024; (2005), 48(9), 1300–1306. [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Jiang, J.; Lin, B.; Liu, Q.; Lin, W.; Chen, G.; Wen, J. Antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccination in people with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2023 Jan;17(1): e13078. [CrossRef]

- Faizo, A.A.; Qashqari, F.S.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Barasheed, O.; Almashjary, M.N.; Alfelali, M.; Bawazir, A.A.; et al. A potential association between obesity and reduced effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine-induced neutralizing humoral immunity. J Med Virol. 2023 Jan;95(1): e28130. [CrossRef]

- Dumrisilp, T.; Wongpiyabovorn, J.; Buranapraditkun, S.; Tubjaroen, C.; Chaijitraruch, N.; Prachuapthunyachart, S.; Sintusek, P.; Chongsrisawat, V. Impact of Obesity and Being Overweight on the Immunogenicity to Live Attenuated Hepatitis A Vaccine in Children and Young Adults. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 6;9(2):130. [CrossRef]

- Soponkanabhorn, T.; Suratannon, N.; Buranapraditkun, S.; Tubjareon, C.; Prachuapthunyachart, S.; Eiamkulbutr, S.; Chongsrisawat, V. Cellular immune response to a single dose of live attenuated hepatitis a virus vaccine in obese children and adolescents. Heliyon. 2024 Aug 20;10(16):e36610. [CrossRef]

- Fonzo, M.; Nicolli, A.; Maso, S.; Carrer, L.; Trevisan, A.; Bertoncello, C. Body Mass Index and Antibody Persistence after Measles, Mumps, Rubella and Hepatitis B Vaccinations. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jul 20;10(7):1152. [CrossRef]

- Kara, Z.; Akçin, R.; Demir, A. N.; Dinç, H. Ö.; Taşkın, H. E.; Kocazeybek, B.; Yumuk, V. D. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in People with Severe Obesity. Obesity surgery, 2022, 32(9), 2987–2993. [CrossRef]

- Drożdżyńska, J.; Jakubowska, W.; Kemuś, M.; Krokowska, M.; Karpezo, K.; Wiśniewska, M.; Bogdański, P.; Skrypnik, D. SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Vaccines in People with Excessive Body Mass-A Narrative Review. Life (Basel, Switzerland), 2022; 12(10), 1617. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Romero, M.; Diaz, A.; Blomberg, B. B. Obesity accelerates age defects in B cells, and weight loss improves B cell function. Immunity & ageing: I & A, 2023; 20(1), 35. [CrossRef]

- García, A.; De Sanctis, J.B. An overview of adjuvant formulations and delivery systems. APMIS. 2014 Apr;122(4):257-67. [CrossRef]

- White, S.J.; Taylor, M.J.; Hurt, R.T.; Jensen, M.D.; Poland, G.A. Leptin-based adjuvants: an innovative approach to improve vaccine response. Vaccine. 2013 Mar 25;31(13):1666-72. [CrossRef]

- Ben Nasr, M.; Usuelli, V.; Dellepiane, S.; Seelam, A.J.; Fiorentino, T.V.; D'Addio, F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor is a T cell-negative costimulatory molecule. Cell Metab. 2024 Jun 4;36(6):1302-1319.e12. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J. V.; García, A. H.; De Sanctis, C. V.; Hajdúch, M.; De Sanctis, J. B. Autoimmunity and Immunodeficiency in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Prolonged COVID-19. Current Issues In Molecular Biology, 2022; 45(1), 33–50. [CrossRef]

- García, A. H.; De Sanctis, J. B. Exploring the Contrasts and Similarities of Dengue and SARS-CoV-2 Infections During the COVID-19 Era. Inter J Mol Sci, 2024; 25(21), 11624. [CrossRef]

| Adipokine | Pro-inflammatory | Anti-inflammatory | Reference |

| Adiponectin | No | Yes | [12,13] |

| Adipsin (complement factor-D) | No | Yes | [14,15] |

| Apelin | No | Yes | [16] |

| Chemerin | Yes | No | [17] |

| Leptin | Yes | Yes | [18,19] |

| Meteorin like (IL41) | No | Yes | [20,21] |

| Omentin-1 | No | Yes | [22] |

| Resistin | Yes | No | [23] |

| Vaspin | Yes | Yes | [24,25] |

| Visfatin | Yes | No | [26] |

| Effect | References | |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | Monocyte migration to adipose tissue | [27] |

| CCL5 | Monocyte migration to adipose tissue | [28] |

| CCL22 | Thermogenesis induction. | [29] |

| IL-6 | Local activation of immune cells. Metabolic dysregulation. | [30] |

| IFN | IFNα induces apoptosis in adipocytes. IFNβ regulates metabolism. IFNγ proinflammatory response, reduction of adipose tissue. IFNλ1 enhances inflammatory response. IFNτ reduces inflammatory response. |

[31] |

| TNFα | Activation of tissue immune cells. Metabolic dysregulation. | [32,33] |

| IL-1 and IL-RA | IL-1 α hypertrophy of white adipose tissue IL-1 β promotes adipogenesis in murine and human adipose-derived stem cells. IL-RA is upregulated in white adipose tissue, and high circulating levels in obesity |

[34,35,36,37] |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 | It plays a role in metabolic homeostasis and inflammatory response. Inhibition of the enzyme plus metformin induces a significant decrease in visceral adipose tissue. | [38] |

| Fibroblast growth factor 21 | Anti-inflammatory. | [39] |

| Retinol binding protein 4 | Induction of inflammatory response. Inhibition of insulin signaling. | [40] |

| Lipocalin-2 | Produced by white adipocytes. Increase adipose tissue. Involved in neutrophil chemoattraction | [41,42] |

| TGFβ | Involved in tissue fibrosis and insulin resistance. | [43] |

| Cell type | Effect | Reference |

| Neutrophils | Retain phagocytic activity, increase basal superoxide, and chemotaxis. Absolute neutrophil counts and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio may indicate adipose tissue inflammation. Relationship of microbiota with neutrophil infiltration in adipose tissue. |

[75,76,77] |

| Eosinophils | Eosinophils protect adipose tissue inflammation. | [78] |

| Mast cells | Mast cells are activated in human adipose tissue and localized preferentially in fibrosis depots. | [79] |

| Macrophages | In lean tissue M2 macrophages and M1 in inflammatory tissues. | [80] |

| iNKT cells | Present in lean adipose tissue can be activated by CD1 and can incorporate lipids, generating a local inflammatory response | [69,70,82] |

| NK | Present in adipose tissue. Tolerogenic response in adipose tissue? Different responses in gender. | [83,84] |

| Tγδ | Inhibit inflammatory response | [85] |

| B cells | Dysfunctional B cells in obese individuals. The lean adipose tissue contains B regulatory and B1 cells. The B1 produces IgM antibodies for primary innate immunity. B2 cells usually generate protective antibodies in lymphoid organs. However, they participate in local inflammation and promote insulin resistance after migrating to white adipose tissue. |

[86,87,88] |

| Th1 cells | Promote obesity-associated inflammation. | [87,89] |

| Th2 | Stabilize adipose tissue and induce M2 polarization. The decrease in Th2 cells in the tissue is due to increased local IFNγ and inflammation. | [87,90] |

| Th17 | Proinflammatory role. Related to IL-23 secretion in adipose tissue |

[91,92] |

| Th22 | IL-22 is produced by innate lymphocyte cells upon tissue inflammation. It is related to insulin resistance. | [93] |

| CD8 cells | Cytotoxic response. Adipose tissue inflammation. Tissue remodeling. | [94,95] |

| Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells | Secretes IL-17, inducing local tissue inflammation. | [96,97] |

| T follicular cells (TF). TFh Helper and TFreg Regulatory. | Modulate the response of B cells in adipose tissue. Impairment of TFregulatory cells is related to autoimmunity. | [98,99] |

| Follicular B cells | In adipose tissue, it induces inflammation depending on the cytokine milieu. Mesenchymal adipose stem cells induce expansion of IL-10-producing B cells—possible role in autoimmunity. |

[100] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Anti-inflammatory in the presence of Treg and Th2 milieu. Pro-inflammatory in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. | [101,102] |

| Virus | Adipose tissue involvement | IFN responses | Reference |

| Adenoviruses |

Yes |

Suppression. Chronic infection. Obesity-induced viral infection? | [135] |

| Arboviruses | Yes | Suppression. Chronic infection. | [136] |

| Herpesviridae | Yes | HSV-1 suppression through miRNA CMV-multiple antagonistic mechanisms |

[137] |

| Slow Virus (Prion) | Yes |

Inhibition of IFN signaling | [137] |

| Dengue | Yes | Inhibition of INF signaling | [138,139] |

| Papillomavirus | Yes | IFN signaling decreased | [140,141] |

| HCV | Yes | Antagonism of IFN signaling. Chronicity | [142] |

| HIV | Yes | Antagonism of IFN signaling. Chronicity | [143] |

| RSV | Yes | Virus inhibits IFN signaling | [144,145] |

| Coronavirus | Yes | IFN signaling is inhibited | [146,147] |

| Influenza | Yes | IFN signaling is inhibited | [148] |

| Hepatitis B virus | Yes | IFN response impaired | [149] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).