Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction on Evolution and Chromoagenesis

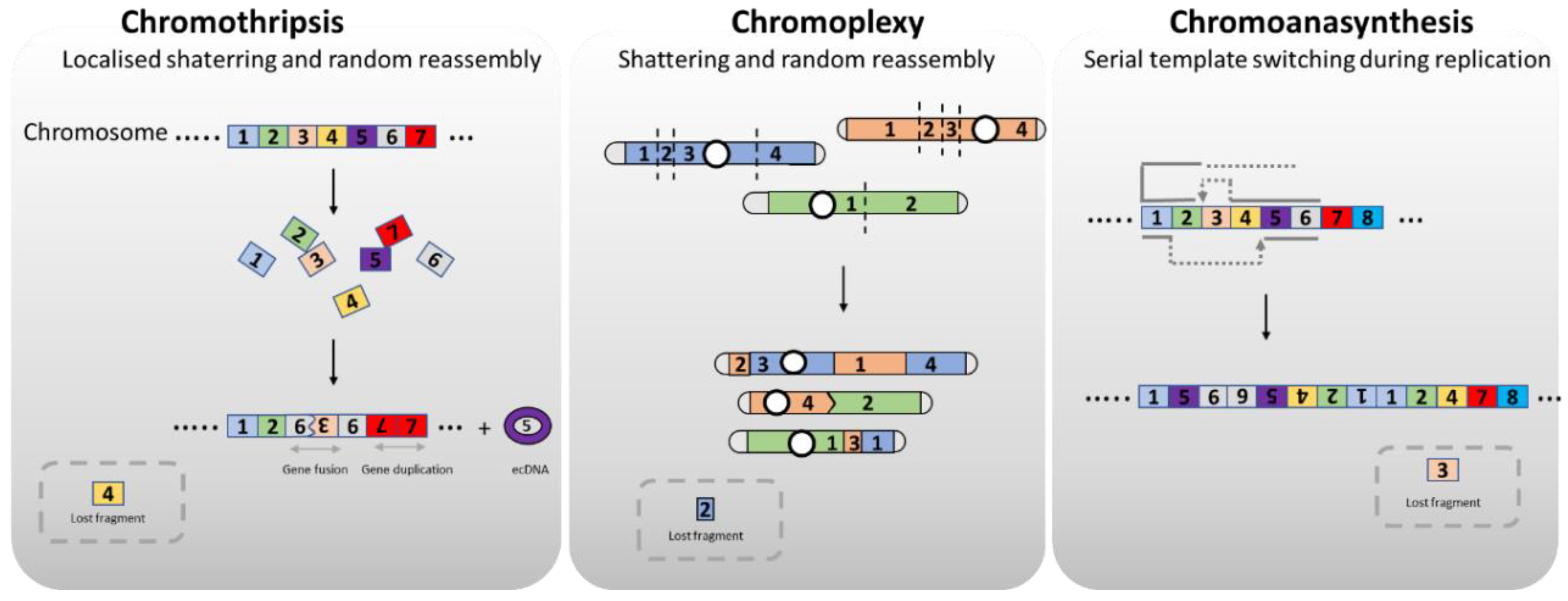

2. Chromoagenesis, a Chromosome Rebirth

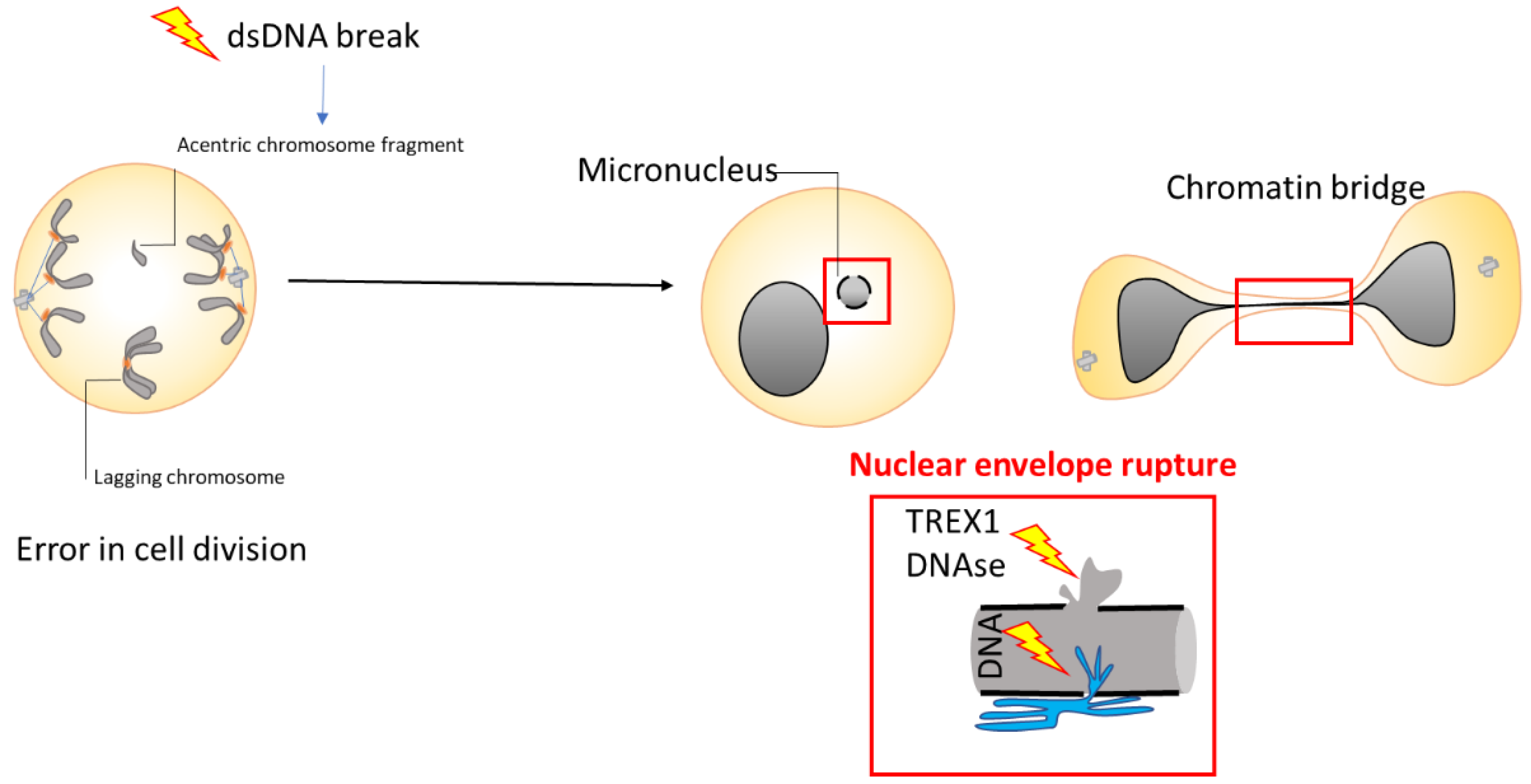

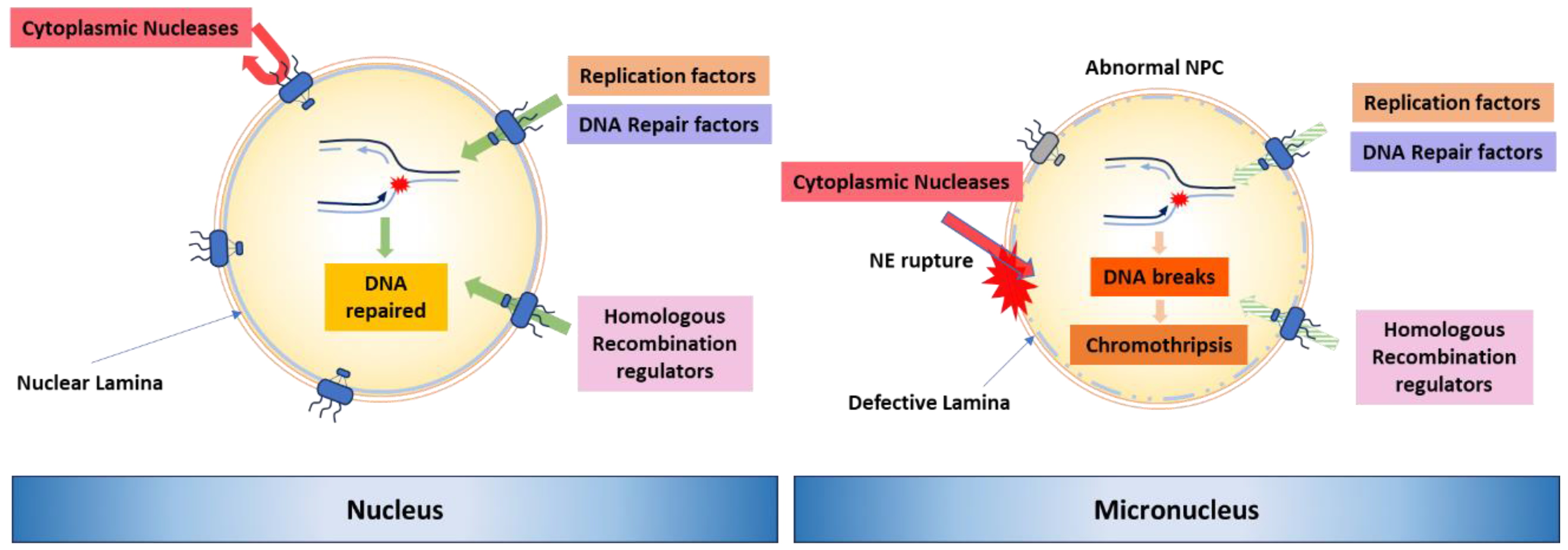

3. Molecular Mechanisms to Generate Genome Rearrangements, Source for Evolution

4. Chromosomal Instability and Macroevolution

5. Chromosomal Instability in Cancer

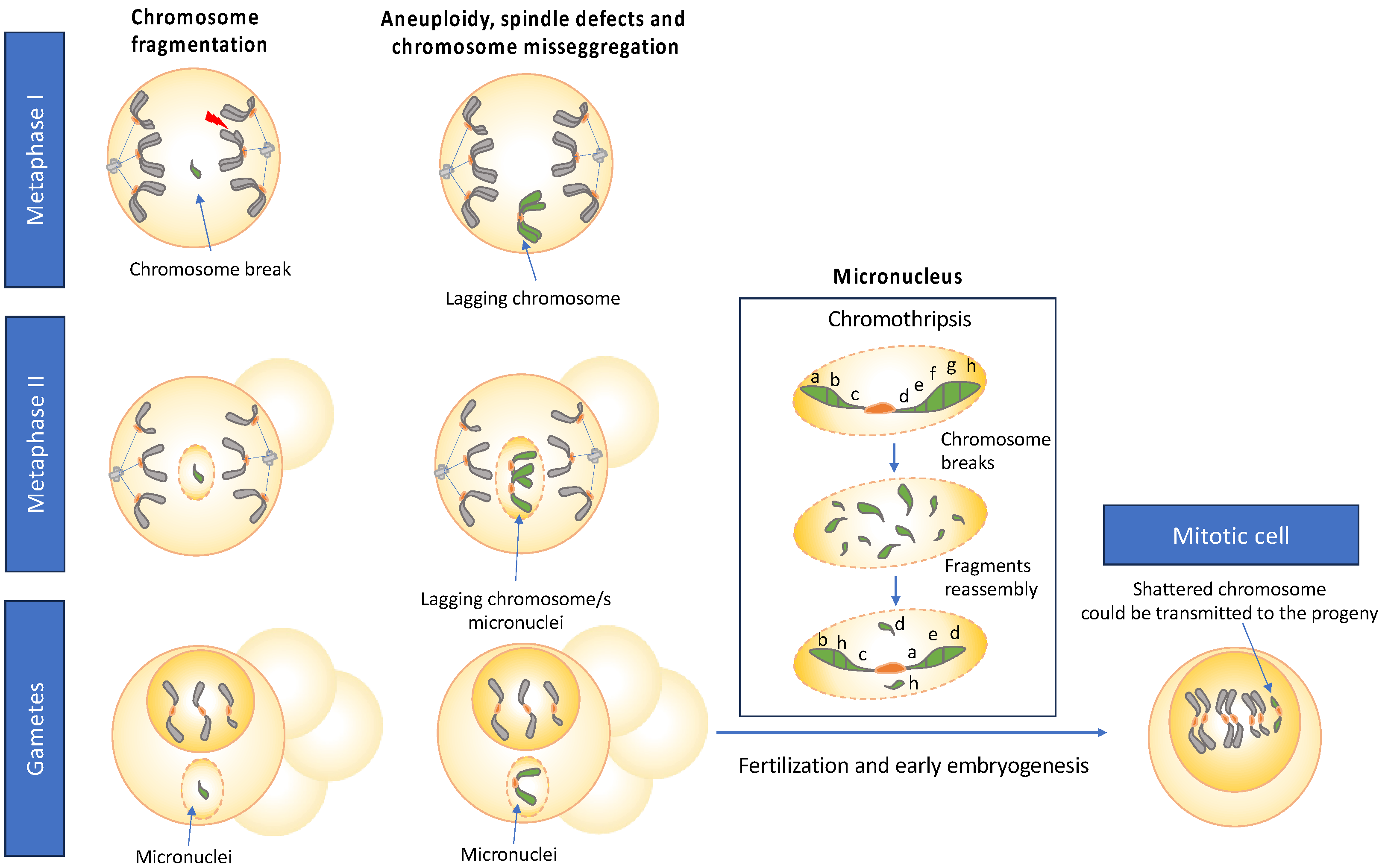

6. Mitotic and Meiotic Programs as Drivers for Genome Evolution

7. Rearrangements of Chromosomes During the Initial Stages of Development

8. Chromosomal Instability Processes in the Germ Cells

9. Gametogenesis as a Source of Chromoanagenesis

10. Meiotic Specific Processes as Drivers for Chromosomal Rearrangements

11. Concluding Remarks

References

- Brownstein CD, MacGuigan DJ, Kim D, Orr O, Yang L, David SR, Kreiser B, Near TJ (2024) The genomic signatures of evolutionary stasis. Evolution. [CrossRef]

- Gazo I, Franek R, Sindelka R, Lebeda I, Shivaramu S, Psenicka M, Steinbach C (2020) Ancient Sturgeons Possess Effective DNA Repair Mechanisms: Influence of Model Genotoxicants on Embryo Development of Sterlet, Acipenser ruthenus. Int J Mol Sci 22 (1). [CrossRef]

- Pazhenkova EA, Lukhtanov VA (2023) Chromosomal conservatism vs chromosomal megaevolution: enigma of karyotypic evolution in Lepidoptera. Chromosome Res 31 (2):16. [CrossRef]

- Mudd AB, Bredeson JV, Baum R, Hockemeyer D, Rokhsar DS (2020) Analysis of muntjac deer genome and chromatin architecture reveals rapid karyotype evolution. Commun Biol 3 (1):480. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y, Fan H, Zhou B, Hu Y, Fan G, Wang J, Zhou F, Nie W, Zhang C, Liu L, Zhong Z, Zhu W, Liu G, Lin Z, Liu C, Zhou J, Huang G, Li Z, Yu J, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhuo B, Zhang B, Chang J, Qian H, Peng Y, Chen X, Chen L, Li Z, Zhou Q, Wang W, Wei F (2021) Molecular mechanisms and topological consequences of drastic chromosomal rearrangements of muntjac deer. Nature Communications 12 (1):6858. [CrossRef]

- Baker RJ, Bickham JW (1980) Karyotypic Evolution in Bats: Evidence of Extensive and Conservative Chromosomal Evolution in Closely Related Taxa. Systematic Biology 29 (3):239-253. [CrossRef]

- Carbone L, Harris RA, Gnerre S, Veeramah KR, Lorente-Galdos B, Huddleston J, Meyer TJ, Herrero J, Roos C, Aken B, Anaclerio F, Archidiacono N, Baker C, Barrell D, Batzer MA, Beal K, Blancher A, Bohrson CL, Brameier M, Campbell MS, Capozzi O, Casola C, Chiatante G, Cree A, Damert A, de Jong PJ, Dumas L, Fernandez-Callejo M, Flicek P, Fuchs NV, Gut I, Gut M, Hahn MW, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Hillier LW, Hubley R, Ianc B, Izsvak Z, Jablonski NG, Johnstone LM, Karimpour-Fard A, Konkel MK, Kostka D, Lazar NH, Lee SL, Lewis LR, Liu Y, Locke DP, Mallick S, Mendez FL, Muffato M, Nazareth LV, Nevonen KA, O'Bleness M, Ochis C, Odom DT, Pollard KS, Quilez J, Reich D, Rocchi M, Schumann GG, Searle S, Sikela JM, Skollar G, Smit A, Sonmez K, ten Hallers B, Terhune E, Thomas GW, Ullmer B, Ventura M, Walker JA, Wall JD, Walter L, Ward MC, Wheelan SJ, Whelan CW, White S, Wilhelm LJ, Woerner AE, Yandell M, Zhu B, Hammer MF, Marques-Bonet T, Eichler EE, Fulton L, Fronick C, Muzny DM, Warren WC, Worley KC, Rogers J, Wilson RK, Gibbs RA (2014) Gibbon genome and the fast karyotype evolution of small apes. Nature 513 (7517):195-201. [CrossRef]

- Bell DM, Hamilton MJ, Edwards CW, Wiggins LE, MartÍnez RM, Strauss RE, Bradley RD, Baker RJ (2001) Patterns of Karyotypic Megaevolution in Reithrodontomys: Evidence From a Cytochrome-b Phylogenetic Hypothesis. Journal of Mammalogy 82 (1):81-91. [CrossRef]

- Vershinina AO, Lukhtanov VA (2017) Evolutionary mechanisms of runaway chromosome number change in Agrodiaetus butterflies. Sci Rep 7 (1):8199. [CrossRef]

- Van de Peer Y, Mizrachi E, Marchal K (2017) The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat Rev Genet 18 (7):411-424. [CrossRef]

- Comai L (2005) The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat Rev Genet 6 (11):836-846. [CrossRef]

- Krupina K, Goginashvili A, Cleveland DW (2024) Scrambling the genome in cancer: causes and consequences of complex chromosome rearrangements. Nat Rev Genet 25 (3):196-210. [CrossRef]

- Comaills V, Castellano-Pozo M (2023) Chromosomal Instability in Genome Evolution: From Cancer to Macroevolution. Biology (Basel) 12 (5). [CrossRef]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW (2012) Chromoanagenesis and cancer: mechanisms and consequences of localized, complex chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Med 18 (11):1630-1638. [CrossRef]

- Schuy J, Grochowski CM, Carvalho CMB, Lindstrand A (2022) Complex genomic rearrangements: an underestimated cause of rare diseases. Trends Genet 38 (11):1134-1146. [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Mendoza CJ, Morton CC (2019) The Iceberg under Water: Unexplored Complexity of Chromoanagenesis in Congenital Disorders. Am J Hum Genet 104 (4):565-577. [CrossRef]

- Pellestor F, Gatinois V (2020) Chromoanagenesis: a piece of the macroevolution scenario. Mol Cytogenet 13:3. [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Mathieu R, Krasovec M, Hebrard M, Yau S, Desgranges E, Martin J, Schackwitz W, Kuo A, Salin G, Donnadieu C, Desdevises Y, Sanchez-Ferandin S, Moreau H, Rivals E, Grigoriev IV, Grimsley N, Eyre-Walker A, Piganeau G (2017) Population genomics of picophytoplankton unveils novel chromosome hypervariability. Sci Adv 3 (7):e1700239. [CrossRef]

- Croll D, Zala M, McDonald BA (2013) Breakage-fusion-bridge cycles and large insertions contribute to the rapid evolution of accessory chromosomes in a fungal pathogen. PLoS Genet 9 (6):e1003567. [CrossRef]

- Burchardt P, Buddenhagen CE, Gaeta ML, Souza MD, Marques A, Vanzela ALL (2020) Holocentric Karyotype Evolution in Rhynchospora Is Marked by Intense Numerical, Structural, and Genome Size Changes. Front Plant Sci 11:536507. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Comai L, Henry IM (2023) Chromoanagenesis in plants: triggers, mechanisms, and potential impact. Trends Genet 39 (1):34-45. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Q, Meng Y, Wang P, Qin X, Cheng C, Zhou J, Yu X, Li J, Lou Q, Jahn M, Chen J (2021) Reconstruction of ancestral karyotype illuminates chromosome evolution in the genus Cucumis. Plant J 107 (4):1243-1259. [CrossRef]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, McLaren S, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Quail MA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, Carter NP, Morsberger LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Follows GA, Green AR, Flanagan AM, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Campbell PJ (2011) Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 144 (1):27-40. [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Ciriano I, Lee JJ, Xi R, Jain D, Jung YL, Yang L, Gordenin D, Klimczak LJ, Zhang CZ, Pellman DS, Group PSVW, Park PJ, Consortium P (2020) Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat Genet 52 (3):331-341. [CrossRef]

- Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D (2012) DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature 482 (7383):53-58.

- Zhang C-Z, Spektor A, Cornils H, Francis JM, Jackson EK, Liu S, Meyerson M, Pellman D (2015) Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature 522 (7555):179-184.

- Shoshani O, Brunner SF, Yaeger R, Ly P, Nechemia-Arbely Y, Kim DH, Fang R, Castillon GA, Yu M, Li JSZ, Sun Y, Ellisman MH, Ren B, Campbell PJ, Cleveland DW (2021) Chromothripsis drives the evolution of gene amplification in cancer. Nature 591 (7848):137-141. [CrossRef]

- Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, Park K, Kitabayashi N, MacDonald TY, Ghandi M, Van Allen E, Kryukov GV, Sboner A, Theurillat JP, Soong TD, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Tewari A, Beltran H, Onofrio RC, Boysen G, Guiducci C, Barbieri CE, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Saksena G, Voet D, Ramos AH, Winckler W, Cipicchio M, Ardlie K, Kantoff PW, Berger MF, Gabriel SB, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Elemento O, Getz G, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Garraway LA (2013) Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell 153 (3):666-677. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Erez A, Nagamani SC, Dhar SU, Kolodziejska KE, Dharmadhikari AV, Cooper ML, Wiszniewska J, Zhang F, Withers MA, Bacino CA, Campos-Acevedo LD, Delgado MR, Freedenberg D, Garnica A, Grebe TA, Hernandez-Almaguer D, Immken L, Lalani SR, McLean SD, Northrup H, Scaglia F, Strathearn L, Trapane P, Kang SH, Patel A, Cheung SW, Hastings PJ, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR, Bi W (2011) Chromosome catastrophes involve replication mechanisms generating complex genomic rearrangements. Cell 146 (6):889-903. [CrossRef]

- Baker TM, Waise S, Tarabichi M, Van Loo P (2024) Aneuploidy and complex genomic rearrangements in cancer evolution. Nat Cancer 5 (2):228-239. [CrossRef]

- Rosswog C, Bartenhagen C, Welte A, Kahlert Y, Hemstedt N, Lorenz W, Cartolano M, Ackermann S, Perner S, Vogel W, Altmuller J, Nurnberg P, Hertwig F, Gohring G, Lilienweiss E, Stutz AM, Korbel JO, Thomas RK, Peifer M, Fischer M (2021) Chromothripsis followed by circular recombination drives oncogene amplification in human cancer. Nat Genet 53 (12):1673-1685. [CrossRef]

- Umbreit NT, Zhang CZ, Lynch LD, Blaine LJ, Cheng AM, Tourdot R, Sun L, Almubarak HF, Judge K, Mitchell TJ, Spektor A, Pellman D (2020) Mechanisms generating cancer genome complexity from a single cell division error. Science 368 (6488). [CrossRef]

- Gauthier BR, Comaills V (2021) Nuclear Envelope Integrity in Health and Disease: Consequences on Genome Instability and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 22 (14). [CrossRef]

- Ly P, Brunner SF, Shoshani O, Kim DH, Lan W, Pyntikova T, Flanagan AM, Behjati S, Page DC, Campbell PJ (2019) Chromosome segregation errors generate a diverse spectrum of simple and complex genomic rearrangements. Nature genetics 51 (4):705-715.

- Vietri M, Schultz SW, Bellanger A, Jones CM, Petersen LI, Raiborg C, Skarpen E, Pedurupillay CRJ, Kjos I, Kip E, Timmer R, Jain A, Collas P, Knorr RL, Grellscheid SN, Kusumaatmaja H, Brech A, Micci F, Stenmark H, Campsteijn C (2020) Unrestrained ESCRT-III drives micronuclear catastrophe and chromosome fragmentation. Nat Cell Biol 22 (7):856-867. [CrossRef]

- Hatch EM, Fischer AH, Deerinck TJ, Hetzer MW (2013) Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei. Cell 154 (1):47-60.

- Liu S, Kwon M, Mannino M, Yang N, Renda F, Khodjakov A, Pellman D (2018) Nuclear envelope assembly defects link mitotic errors to chromothripsis. Nature 561 (7724):551-555.

- Krupina K, Goginashvili A, Cleveland DW (2021) Causes and consequences of micronuclei. Current opinion in cell biology 70:91-99.

- Vargas JD, Hatch EM, Anderson DJ, Hetzer MW (2012) Transient nuclear envelope rupturing during interphase in human cancer cells. Nucleus 3 (1):88-100.

- Joo YK, Black EM, Trier I, Haakma W, Zou L, Kabeche L (2023) ATR promotes clearance of damaged DNA and damaged cells by rupturing micronuclei. Mol Cell 83 (20):3642-3658 e3644. [CrossRef]

- Maciejowski J, Chatzipli A, Dananberg A, Chu K, Toufektchan E, Klimczak LJ, Gordenin DA, Campbell PJ, de Lange T (2020) APOBEC3-dependent kataegis and TREX1-driven chromothripsis during telomere crisis. Nature genetics 52 (9):884-890.

- Maciejowski J, Li Y, Bosco N, Campbell PJ, de Lange T (2015) Chromothripsis and Kataegis Induced by Telomere Crisis. Cell 163 (7):1641-1654. [CrossRef]

- Denais CM, Gilbert RM, Isermann P, McGregor AL, te Lindert M, Weigelin B, Davidson PM, Friedl P, Wolf K, Lammerding J (2016) Nuclear envelope rupture and repair during cancer cell migration. Science 352 (6283):353-358. [CrossRef]

- Comaills V, Kabeche L, Morris R, Buisson R, Yu M, Madden MW, LiCausi JA, Boukhali M, Tajima K, Pan S, Aceto N, Sil S, Zheng Y, Sundaresan T, Yae T, Jordan NV, Miyamoto DT, Ting DT, Ramaswamy S, Haas W, Zou L, Haber DA, Maheswaran S (2016) Genomic Instability Is Induced by Persistent Proliferation of Cells Undergoing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Cell Rep 17 (10):2632-2647. [CrossRef]

- Raab M, Gentili M, de Belly H, Thiam HR, Vargas P, Jimenez AJ, Lautenschlaeger F, Voituriez R, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Manel N, Piel M (2016) ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death. Science 352 (6283):359-362. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier BR, Lorenzo PI, Comaills V (2021) Physical Forces and Transient Nuclear Envelope Rupture during Metastasis: The Key for Success? Cancers (Basel) 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Weigelin B, den Boer AT, Wagena E, Broen K, Dolstra H, de Boer RJ, Figdor CG, Textor J, Friedl P (2021) Cytotoxic T cells are able to efficiently eliminate cancer cells by additive cytotoxicity. Nat Commun 12 (1):5217. [CrossRef]

- Dacus D, Stancic S, Pollina SR, Rifrogiate E, Palinski R, Wallace NA (2022) Beta human papillomavirus 8 E6 induces micronucleus formation and promotes chromothripsis. Journal of Virology 96 (19):e01015-01022.

- Li JSZ, Abbasi A, Kim DH, Lippman SM, Alexandrov LB, Cleveland DW (2023) Chromosomal fragile site breakage by EBV-encoded EBNA1 at clustered repeats. Nature 616 (7957):504-509.

- Leibowitz ML, Papathanasiou S, Doerfler PA, Blaine LJ, Sun L, Yao Y, Zhang CZ, Weiss MJ, Pellman D (2021) Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nature genetics. [CrossRef]

- Nader GPF, Aguera-Gonzalez S, Routet F, Gratia M, Maurin M, Cancila V, Cadart C, Palamidessi A, Ramos RN, San Roman M, Gentili M, Yamada A, Williart A, Lodillinsky C, Lagoutte E, Villard C, Viovy JL, Tripodo C, Galon J, Scita G, Manel N, Chavrier P, Piel M (2021) Compromised nuclear envelope integrity drives TREX1-dependent DNA damage and tumor cell invasion. Cell 184 (20):5230-5246 e5222. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Stokasimov E, Cui Y, Pellman D (2022) Breakage of cytoplasmic chromosomes by pathological DNA base excision repair. Nature 606 (7916):930-936. [CrossRef]

- Lieber MR (2010) The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annual review of biochemistry 79:181-211.

- McVey M, Lee SE (2008) MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends in Genetics 24 (11):529-538.

- Simsek D, Jasin M (2010) Alternative end-joining is suppressed by the canonical NHEJ component Xrcc4–ligase IV during chromosomal translocation formation. Nature structural & molecular biology 17 (4):410-416.

- Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR (2007) A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. cell 131 (7):1235-1247.

- Kloosterman WP, Guryev V, van Roosmalen M, Duran KJ, de Bruijn E, Bakker SCM, Letteboer T, van Nesselrooij B, Hochstenbach R, Poot M, Cuppen E (2011) Chromothripsis as a mechanism driving complex de novo structural rearrangements in the germline†. Human Molecular Genetics 20 (10):1916-1924. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Khajavi M, Connolly AM, Towne CF, Batish SD, Lupski JR (2009) The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nature genetics 41 (7):849-853.

- Gemble S, Wardenaar R, Keuper K, Srivastava N, Nano M, Mace AS, Tijhuis AE, Bernhard SV, Spierings DCJ, Simon A, Goundiam O, Hochegger H, Piel M, Foijer F, Storchova Z, Basto R (2022) Genetic instability from a single S phase after whole-genome duplication. Nature 604 (7904):146-151. [CrossRef]

- Vittoria MA, Quinton RJ, Ganem NJ (2023) Whole-genome doubling in tissues and tumors. Trends Genet 39 (12):954-967. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Chávez C, Benítez-Álvarez L, Martínez-Redondo GI, Álvarez-González L, Salces-Ortiz J, Eleftheriadi K, Escudero N, Guiglielmoni N, Flot J-F, Novo M, Ruiz-Herrera A, McLysaght A, Fernández R (2024) A punctuated burst of massive genomic rearrangements by chromosome shattering and the origin of non-marine annelids. bioRxiv:2024.2005.2016.594344. [CrossRef]

- Buschiazzo LM, Caraballo DA, Labaroni CA, Teta P, Rossi MS, Bidau CJ, Lanzone C (2022) Comprehensive cytogenetic analysis of the most chromosomally variable mammalian genus from South America: (Rodentia: Caviomorpha: Ctenomyidae). Mamm Biol 102 (5-6):1963-1979. [CrossRef]

- Buschiazzo LM, Caraballo DA, Calcena E, Longarzo ML, Labaroni CA, Ferro JM, Rossi MS, Bolzan AD, Lanzone C (2018) Integrative analysis of chromosome banding, telomere localization and molecular genetics in the highly variable Ctenomys of the Corrientes group (Rodentia; Ctenomyidae). Genetica 146 (4-5):403-414. [CrossRef]

- Caraballo DA, Abruzzese GA, Rossi MS (2012) Diversity of tuco-tucos (Ctenomys, Rodentia) in the Northeastern wetlands from Argentina: mitochondrial phylogeny and chromosomal evolution. Genetica 140 (4-6):125-136. [CrossRef]

- C. Oliveira LFA-T, L. Mori, S. A. Toledo-Filho (1992) Extensive chromosomal rearrangements and nuclear DNA content changes in the evolution of the armoured catfishes genus Corydoras (Pisces, Siluriformes, Callichthyidae). [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Lan H (2000) Rapid and parallel chromosomal number reductions in muntjac deer inferred from mitochondrial DNA phylogeny. Mol Biol Evol 17 (9):1326-1333. [CrossRef]

- Hipp AL (2007) Nonuniform processes of chromosome evolution in sedges (Carex: Cyperaceae). Evolution 61 (9):2175-2194. [CrossRef]

- Chung KS, Hipp AL, Roalson EH (2012) Chromosome number evolves independently of genome size in a clade with nonlocalized centromeres (Carex: Cyperaceae). Evolution 66 (9):2708-2722. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Wang Z, Zhang C, Hu J, Lu Y, Zhou H, Mei Y, Cong Y, Guo F, Wang Y, He K, Liu Y, Li F (2023) Unraveling the complex evolutionary history of lepidopteran chromosomes through ancestral chromosome reconstruction and novel chromosome nomenclature. BMC Biol 21 (1):265. [CrossRef]

- Scalabrin S, Magris G, Liva M, Vitulo N, Vidotto M, Scaglione D, Del Terra L, Ruosi MR, Navarini L, Pellegrino G, Berny Mier YTJC, Toniutti L, Suggi Liverani F, Cerutti M, Di Gaspero G, Morgante M (2024) A chromosome-scale assembly reveals chromosomal aberrations and exchanges generating genetic diversity in Coffea arabica germplasm. Nat Commun 15 (1):463. [CrossRef]

- Carbonell-Bejerano P, Royo C, Torres-Perez R, Grimplet J, Fernandez L, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Lijavetzky D, Baroja E, Martinez J, Garcia-Escudero E, Ibanez J, Martinez-Zapater JM (2017) Catastrophic Unbalanced Genome Rearrangements Cause Somatic Loss of Berry Color in Grapevine. Plant Physiol 175 (2):786-801. [CrossRef]

- Jennings RL, Griffin DK, O'Connor RE (2020) A new Approach for Accurate Detection of Chromosome Rearrangements That Affect Fertility in Cattle. Animals (Basel) 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kerruish DWM, Cormican P, Kenny EM, Kearns J, Colgan E, Boulton CA, Stelma SNE (2024) The origins of the Guinness stout yeast. Commun Biol 7 (1):68. [CrossRef]

- Tello J, Royo C, Baroja E, García-Escudero E, Martínez-Zapater JM, Carbonell-Bejerano P (2021) Reduced gamete viability associated to somatic genome rearrangements increases fruit set sensitivity to the environment in Tempranillo Blanco grapevine cultivar. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 290. [CrossRef]

- Tan EH, Henry IM, Ravi M, Bradnam KR, Mandakova T, Marimuthu MP, Korf I, Lysak MA, Comai L, Chan SW (2015) Catastrophic chromosomal restructuring during genome elimination in plants. Elife 4. [CrossRef]

- Guo WE, Comai L, Henry IM (2023) Chromoanagenesis in the asy1 meiotic mutant of Arabidopsis. G3-Genes Genom Genet 13 (2). [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Comai L, Henry IM (2021) Chromoanagenesis from radiation-induced genome damage in Populus. PLoS genetics 17 (8):e1009735.

- Liu J, Nannas NJ, Fu FF, Shi J, Aspinwall B, Parrott WA, Dawe RK (2019) Genome-Scale Sequence Disruption Following Biolistic Transformation in Rice and Maize. Plant Cell 31 (2):368-383. [CrossRef]

- Fossi M, Amundson K, Kuppu S, Britt A, Comai L (2019) Regeneration of Solanum tuberosum Plants from Protoplasts Induces Widespread Genome Instability. Plant Physiol 180 (1):78-86. [CrossRef]

- Itani OA, Flibotte S, Dumas KJ, Moerman DG, Hu PJ (2015) Chromoanasynthetic Genomic Rearrangement Identified in a N-Ethyl-N-Nitrosourea (ENU) Mutagenesis Screen in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 6 (2):351-356. [CrossRef]

- Meier B, Cooke SL, Weiss J, Bailly AP, Alexandrov LB, Marshall J, Raine K, Maddison M, Anderson E, Stratton MR, Gartner A, Campbell PJ (2014) C. elegans whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational signatures related to carcinogens and DNA repair deficiency. Genome Res 24 (10):1624-1636. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Yu L, Zhang S, Su X, Zhou X (2022) Extrachromosomal circular DNA: Current status and future prospects. Elife 11. [CrossRef]

- Notta F, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Lemire M, Li Y, Wilson GW, Connor AA, Denroche RE, Liang SB, Brown AM, Kim JC, Wang T, Simpson JT, Beck T, Borgida A, Buchner N, Chadwick D, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Dick JE, Heisler L, Hollingsworth MA, Ibrahimov E, Jang GH, Johns J, Jorgensen LG, Law C, Ludkovski O, Lungu I, Ng K, Pasternack D, Petersen GM, Shlush LI, Timms L, Tsao MS, Wilson JM, Yung CK, Zogopoulos G, Bartlett JM, Alexandrov LB, Real FX, Cleary SP, Roehrl MH, McPherson JD, Stein LD, Hudson TJ, Campbell PJ, Gallinger S (2016) A renewed model of pancreatic cancer evolution based on genomic rearrangement patterns. Nature 538 (7625):378-382. [CrossRef]

- Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhang CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH, Sougnez C, Gabriel SB, Hernandez B, Shen H, Laird PW, Getz G, Meyerson M, Beroukhim R (2013) Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet 45 (10):1134-1140. [CrossRef]

- Yates LR, Knappskog S, Wedge D, Farmery JHR, Gonzalez S, Martincorena I, Alexandrov LB, Van Loo P, Haugland HK, Lilleng PK, Gundem G, Gerstung M, Pappaemmanuil E, Gazinska P, Bhosle SG, Jones D, Raine K, Mudie L, Latimer C, Sawyer E, Desmedt C, Sotiriou C, Stratton MR, Sieuwerts AM, Lynch AG, Martens JW, Richardson AL, Tutt A, Lonning PE, Campbell PJ (2017) Genomic Evolution of Breast Cancer Metastasis and Relapse. Cancer Cell 32 (2):169-184 e167. [CrossRef]

- Stachler MD, Taylor-Weiner A, Peng S, McKenna A, Agoston AT, Odze RD, Davison JM, Nason KS, Loda M, Leshchiner I, Stewart C, Stojanov P, Seepo S, Lawrence MS, Ferrer-Torres D, Lin J, Chang AC, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Beer DG, Getz G, Carter SL, Bass AJ (2015) Paired exome analysis of Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 47 (9):1047-1055. [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Shih J, Hollern DP, Wang L, Bowlby R, Tickoo SK, Thorsson V, Mungall AJ, Newton Y, Hegde AM, Armenia J, Sanchez-Vega F, Pluta J, Pyle LC, Mehra R, Reuter VE, Godoy G, Jones J, Shelley CS, Feldman DR, Vidal DO, Lessel D, Kulis T, Carcano FM, Leraas KM, Lichtenberg TM, Brooks D, Cherniack AD, Cho J, Heiman DI, Kasaian K, Liu M, Noble MS, Xi L, Zhang H, Zhou W, ZenKlusen JC, Hutter CM, Felau I, Zhang J, Schultz N, Getz G, Meyerson M, Stuart JM, Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Akbani R, Wheeler DA, Laird PW, Nathanson KL, Cortessis VK, Hoadley KA (2018) Integrated Molecular Characterization of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Cell Rep 23 (11):3392-3406. [CrossRef]

- Dewhurst SM, McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Rowan AJ, Gronroos E, Endesfelder D, Joshi T, Mouradov D, Gibbs P, Ward RL, Hawkins NJ, Szallasi Z, Sieber OM, Swanton C (2014) Tolerance of whole-genome doubling propagates chromosomal instability and accelerates cancer genome evolution. Cancer Discov 4 (2):175-185. [CrossRef]

- Holland LZ, Ocampo Daza D (2018) A new look at an old question: when did the second whole genome duplication occur in vertebrate evolution? Genome Biol 19 (1):209. [CrossRef]

- Sacerdot C, Louis A, Bon C, Berthelot C, Roest Crollius H (2018) Chromosome evolution at the origin of the ancestral vertebrate genome. Genome Biol 19 (1):166. [CrossRef]

- Clark JW, Donoghue PCJ (2018) Whole-Genome Duplication and Plant Macroevolution. Trends Plant Sci 23 (10):933-945. [CrossRef]

- Steele CD, Abbasi A, Islam SMA, Bowes AL, Khandekar A, Haase K, Hames-Fathi S, Ajayi D, Verfaillie A, Dhami P, McLatchie A, Lechner M, Light N, Shlien A, Malkin D, Feber A, Proszek P, Lesluyes T, Mertens F, Flanagan AM, Tarabichi M, Van Loo P, Alexandrov LB, Pillay N (2022) Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature 606 (7916):984-991. [CrossRef]

- Consortium ITP-CAoWG (2020) Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 578 (7793):82-93. [CrossRef]

- Drews RM, Hernando B, Tarabichi M, Haase K, Lesluyes T, Smith PS, Morrill Gavarro L, Couturier DL, Liu L, Schneider M, Brenton JD, Van Loo P, Macintyre G, Markowetz F (2022) A pan-cancer compendium of chromosomal instability. Nature 606 (7916):976-983. [CrossRef]

- Shen MM (2013) Chromoplexy: a new category of complex rearrangements in the cancer genome. Cancer Cell 23 (5):567-569. [CrossRef]

- Voronina N, Wong JKL, Hubschmann D, Hlevnjak M, Uhrig S, Heilig CE, Horak P, Kreutzfeldt S, Mock A, Stenzinger A, Hutter B, Frohlich M, Brors B, Jahn A, Klink B, Gieldon L, Sieverling L, Feuerbach L, Chudasama P, Beck K, Kroiss M, Heining C, Mohrmann L, Fischer A, Schrock E, Glimm H, Zapatka M, Lichter P, Frohling S, Ernst A (2020) The landscape of chromothripsis across adult cancer types. Nat Commun 11 (1):2320. [CrossRef]

- Durante MA, Rodriguez DA, Kurtenbach S, Kuznetsov JN, Sanchez MI, Decatur CL, Snyder H, Feun LG, Livingstone AS, Harbour JW (2020) Single-cell analysis reveals new evolutionary complexity in uveal melanoma. Nat Commun 11 (1):496. [CrossRef]

- Lukow DA, Sausville EL, Suri P, Chunduri NK, Wieland A, Leu J, Smith JC, Girish V, Kumar AA, Kendall J, Wang Z, Storchova Z, Sheltzer JM (2021) Chromosomal instability accelerates the evolution of resistance to anti-cancer therapies. Dev Cell 56 (17):2427-2439 e2424. [CrossRef]

- Yan X, Mischel P, Chang H (2024) Extrachromosomal DNA in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 24 (4):261-273. [CrossRef]

- Davoli T, Uno H, Wooten EC, Elledge SJ (2017) Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science 355 (6322). [CrossRef]

- Bakhoum SF, Ngo B, Laughney AM, Cavallo JA, Murphy CJ, Ly P, Shah P, Sriram RK, Watkins TBK, Taunk NK, Duran M, Pauli C, Shaw C, Chadalavada K, Rajasekhar VK, Genovese G, Venkatesan S, Birkbak NJ, McGranahan N, Lundquist M, LaPlant Q, Healey JH, Elemento O, Chung CH, Lee NY, Imielenski M, Nanjangud G, Pe'er D, Cleveland DW, Powell SN, Lammerding J, Swanton C, Cantley LC (2018) Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. Nature 553 (7689):467-472. [CrossRef]

- Winick-Ng W, Kukalev A, Harabula I, Zea-Redondo L, Szabó D, Meijer M, Serebreni L, Zhang Y, Bianco S, Chiariello AM (2021) Cell-type specialization is encoded by specific chromatin topologies. Nature 599 (7886):684-691.

- Salari H, Di Stefano M, Jost D (2022) Spatial organization of chromosomes leads to heterogeneous chromatin motion and drives the liquid-or gel-like dynamical behavior of chromatin. Genome research 32 (1):28-43.

- Kim S, Peterson SE, Jasin M, Keeney S Mechanisms of germ line genome instability. In: Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2016. Elsevier, pp 177-187.

- Hattori A, Fukami M (2020) Established and novel mechanisms leading to de novo genomic rearrangements in the human germline. Cytogenetic and Genome Research 160 (4):167-176.

- Bhat P, Honson D, Guttman M (2021) Nuclear compartmentalization as a mechanism of quantitative control of gene expression. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 22 (10):653-670.

- Glaser J, Mundlos S (2022) 3D or not 3D: shaping the genome during development. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 14 (5):a040188.

- Akdemir KC, Le VT, Chandran S, Li Y, Verhaak RG, Beroukhim R, Campbell PJ, Chin L, Dixon JR, Futreal PA, Akdemir KC, Alvarez EG, Baez-Ortega A, Boutros PC, Bowtell DDL, Brors B, Burns KH, Campbell PJ, Chan K, Chen K, Cortés-Ciriano I, Dueso-Barroso A, Dunford AJ, Edwards PA, Estivill X, Etemadmoghadam D, Feuerbach L, Fink JL, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Garsed DW, Gerstein M, Gordenin DA, Haan D, Haber JE, Hess JM, Hutter B, Imielinski M, Jones DTW, Ju YS, Kazanov MD, Klimczak LJ, Koh Y, Korbel JO, Kumar K, Lee EA, Lee JJ-K, Li Y, Lynch AG, Macintyre G, Markowetz F, Martincorena I, Martinez-Fundichely A, Meyerson M, Miyano S, Nakagawa H, Navarro FCP, Ossowski S, Park PJ, Pearson JV, Puiggròs M, Rippe K, Roberts ND, Roberts SA, Rodriguez-Martin B, Schumacher SE, Scully R, Shackleton M, Sidiropoulos N, Sieverling L, Stewart C, Torrents D, Tubio JMC, Villasante I, Waddell N, Wala JA, Weischenfeldt J, Yang L, Yao X, Yoon S-S, Zamora J, Zhang C-Z, Aaltonen LA, Abascal F, Abeshouse A, Aburatani H, Adams DJ, Agrawal N, Ahn KS, Ahn S-M, Aikata H, Akbani R, Akdemir KC, Al-Ahmadie H, Al-Sedairy ST, Al-Shahrour F, Alawi M, Albert M, Aldape K, Alexandrov LB, Ally A, Alsop K, Alvarez EG, Amary F, Amin SB, Aminou B, Ammerpohl O, Anderson MJ, Ang Y, Antonello D, Anur P, Aparicio S, Appelbaum EL, Arai Y, Aretz A, Arihiro K, Ariizumi S-i, Armenia J, Arnould L, Asa S, Assenov Y, Atwal G, Aukema S, Auman JT, Aure MRR, Awadalla P, Aymerich M, Bader GD, Baez-Ortega A, Bailey MH, Bailey PJ, Balasundaram M, Balu S, Bandopadhayay P, Banks RE, Barbi S, Barbour AP, Barenboim J, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Barr H, Barrera E, Bartlett J, Bartolome J, Bassi C, Bathe OF, Baumhoer D, Bavi P, Baylin SB, Bazant W, Beardsmore D, Beck TA, Behjati S, Behren A, Niu B, Bell C, Beltran S, Benz C, Berchuck A, Bergmann AK, Bergstrom EN, Berman BP, Berney DM, Bernhart SH, Beroukhim R, Berrios M, Bersani S, Bertl J, Betancourt M, Bhandari V, Bhosle SG, Biankin AV, Bieg M, Bigner D, Binder H, Birney E, Birrer M, Biswas NK, Bjerkehagen B, Bodenheimer T, Boice L, Bonizzato G, De Bono JS, Boot A, Bootwalla MS, Borg A, Borkhardt A, Boroevich KA, Borozan I, Borst C, Bosenberg M, Bosio M, Boultwood J, Bourque G, Boutros PC, Bova GS, Bowen DT, Bowlby R, Bowtell DDL, Boyault S, Boyce R, Boyd J, Brazma A, Brennan P, Brewer DS, Brinkman AB, Bristow RG, Broaddus RR, Brock JE, Brock M, Broeks A, Brooks AN, Brooks D, Brors B, Brunak S, Bruxner TJC, Bruzos AL, Buchanan A, Buchhalter I, Buchholz C, Bullman S, Burke H, Burkhardt B, Burns KH, Busanovich J, Bustamante CD, Butler AP, Butte AJ, Byrne NJ, Børresen-Dale A-L, Caesar-Johnson SJ, Cafferkey A, Cahill D, Calabrese C, Caldas C, Calvo F, Camacho N, Campbell PJ, Campo E, Cantù C, Cao S, Carey TE, Carlevaro-Fita J, Carlsen R, Cataldo I, Cazzola M, Cebon J, Cerfolio R, Chadwick DE, Chakravarty D, Chalmers D, Chan CWY, Chan K, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Chandan VS, Chang DK, Chanock SJ, Chantrill LA, Chateigner A, Chatterjee N, Chayama K, Chen H-W, Chen J, Chen K, Chen Y, Chen Z, Cherniack AD, Chien J, Chiew Y-E, Chin S-F, Cho J, Cho S, Choi JK, Choi W, Chomienne C, Chong Z, Choo SP, Chou A, Christ AN, Christie EL, Chuah E, Cibulskis C, Cibulskis K, Cingarlini S, Clapham P, Claviez A, Cleary S, Cloonan N, Cmero M, Collins CC, Connor AA, Cooke SL, Cooper CS, Cope L, Corbo V, Cordes MG, Cordner SM, Cortés-Ciriano I, Covington K, Cowin PA, Group PSVW, Consortium P (2020) Disruption of chromatin folding domains by somatic genomic rearrangements in human cancer. Nature Genetics 52 (3):294-305. [CrossRef]

- Lupiáñez DG, Kraft K, Heinrich V, Krawitz P, Brancati F, Klopocki E, Horn D, Kayserili H, Opitz JM, Laxova R (2015) Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell 161 (5):1012-1025.

- Tanabe H, Müller S, Neusser M, von Hase J, Calcagno E, Cremer M, Solovei I, Cremer C, Cremer T (2002) Evolutionary conservation of chromosome territory arrangements in cell nuclei from higher primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (7):4424-4429.

- Guerrero RF, Kirkpatrick M (2014) Local adaptation and the evolution of chromosome fusions. Evolution 68 (10):2747-2756.

- Matveevsky S, Tretiakov A, Kashintsova A, Bakloushinskaya I, Kolomiets O (2020) Meiotic nuclear architecture in distinct mole vole hybrids with Robertsonian translocations: Chromosome chains, stretched centromeres, and distorted recombination. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21 (20):7630.

- Kneissig M, Keuper K, de Pagter MS, van Roosmalen MJ, Martin J, Otto H, Passerini V, Campos Sparr A, Renkens I, Kropveld F, Vasudevan A, Sheltzer JM, Kloosterman WP, Storchova Z (2019) Micronuclei-based model system reveals functional consequences of chromothripsis in human cells. Elife 8. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Comai L, Henry IM (2021) Chromoanagenesis from radiation-induced genome damage in Populus. PLoS Genet 17 (8):e1009735. [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou S, Markoulaki S, Blaine LJ, Leibowitz ML, Zhang CZ, Jaenisch R, Pellman D (2021) Whole chromosome loss and genomic instability in mouse embryos after CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Commun 12 (1):5855. [CrossRef]

- Roosen M, Odé Z, Bunt J, Kool M (2022) The oncogenic fusion landscape in pediatric CNS neoplasms. Acta Neuropathologica 143 (4):427-451.

- van Belzen IA, Cai C, van Tuil M, Badloe S, Strengman E, Janse A, Verwiel ET, van der Leest DF, Kester L, Molenaar JJ (2023) Systematic discovery of gene fusions in pediatric cancer by integrating RNA-seq and WGS. BMC cancer 23 (1):618.

- Dai X, Guo X (2021) Decoding and rejuvenating human ageing genomes: Lessons from mosaic chromosomal alterations. Ageing Res Rev 68:101342. [CrossRef]

- Vera-Rodriguez M, Chavez SL, Rubio C, Pera RAR, Simon C (2015) Prediction model for aneuploidy in early human embryo development revealed by single-cell analysis. Nature communications 6 (1):7601.

- Vanneste E, Voet T, Le Caignec C, Ampe M, Konings P, Melotte C, Debrock S, Amyere M, Vikkula M, Schuit F (2009) Chromosome instability is common in human cleavage-stage embryos. Nature medicine 15 (5):577.

- Tuck-Muller CM, Chen H, Martínez JE, Shen CC, Li S, Kusyk C, Batista DA, Bhatnagar YM, Dowling E, Wertelecki W (1995) Isodicentric Y chromosome: cytogenetic, molecular and clinical studies and review of the literature. Hum Genet 96 (1):119-129. [CrossRef]

- Chandley AC, Ambros P, McBeath S, Hargreave TB, Kilanowski F, Spowart G (1986) Short arm dicentric Y chromosome with associated statural defects in a sterile man. Hum Genet 73 (4):350-353. [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi A, Parma P, Iannuzzi L (2021) Chromosome Abnormalities and Fertility in Domestic Bovids: A Review. Animals (Basel) 11 (3). [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Breuss MW, Xu X, Antaki D, James KN, Stanley V, Ball LL, George RD, Wirth SA, Cao B, Nguyen A, McEvoy-Venneri J, Chai G, Nahas S, Van Der Kraan L, Ding Y, Sebat J, Gleeson JG (2021) Developmental and temporal characteristics of clonal sperm mosaicism. Cell 184 (18):4772-4783.e4715. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman-Aiden E, Van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO (2009) Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. science 326 (5950):289-293.

- Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, Sanborn AL, Machol I, Omer AD, Lander ES (2014) A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159 (7):1665-1680.

- Vara C, Paytuví-Gallart A, Cuartero Y, Le Dily F, Garcia F, Salvà-Castro J, Gómez HL, Julià E, Moutinho C, Aiese Cigliano R, Sanseverino W, Fornas O, Pendás AM, Heyn H, Waters PD, Marti-Renom MA, Ruiz-Herrera A (2019) Three-Dimensional Genomic Structure and Cohesin Occupancy Correlate with Transcriptional Activity during Spermatogenesis. Cell Rep 28 (2):352-367.e359. [CrossRef]

- Alavattam KG, Maezawa S, Sakashita A, Khoury H, Barski A, Kaplan N, Namekawa SH (2019) Attenuated chromatin compartmentalization in meiosis and its maturation in sperm development. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26 (3):175-184. [CrossRef]

- Ing-Simmons E, Rigau M, Vaquerizas JM (2022) Emerging mechanisms and dynamics of three-dimensional genome organisation at zygotic genome activation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 74:37-46. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh RP, Meyer BJ (2021) Spatial Organization of Chromatin: Emergence of Chromatin Structure During Development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 37:199-232. [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Bonet M, Benet J, Sun F, Navarro J, Abad C, Liehr T, Starke H, Greene C, Ko E, Martin RH (2005) Meiotic studies in two human reciprocal translocations and their association with spermatogenic failure. Hum Reprod 20 (3):683-688. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Carvalho CM, Hastings PJ, Lupski JR (2012) Mechanisms for recurrent and complex human genomic rearrangements. Curr Opin Genet Dev 22 (3):211-220. [CrossRef]

- Turner DJ, Miretti M, Rajan D, Fiegler H, Carter NP, Blayney ML, Beck S, Hurles ME (2008) Germline rates of de novo meiotic deletions and duplications causing several genomic disorders. Nat Genet 40 (1):90-95. [CrossRef]

- Bazykin AD (1969) HYPOTHETICAL MECHANISM OF SPECIATION. Evolution 23 (4):685-687. [CrossRef]

- Biesecker LG, Spinner NB (2013) A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease. Nat Rev Genet 14 (5):307-320. [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen B, Nazaryan-Petersen L, Sun W, Mehrjouy MM, Xie G, Chen W, Hjermind LE, Taschner PE, Tümer Z (2016) A germline chromothripsis event stably segregating in 11 individuals through three generations. Genet Med 18 (5):494-500. [CrossRef]

- Lindholm AK, Dyer KA, Firman RC, Fishman L, Forstmeier W, Holman L, Johannesson H, Knief U, Kokko H, Larracuente AM, Manser A, Montchamp-Moreau C, Petrosyan VG, Pomiankowski A, Presgraves DC, Safronova LD, Sutter A, Unckless RL, Verspoor RL, Wedell N, Wilkinson GS, Price TAR (2016) The Ecology and Evolutionary Dynamics of Meiotic Drive. Trends Ecol Evol 31 (4):315-326. [CrossRef]

- Pellestor F, Gatinois V, Puechberty J, Geneviève D, Lefort G (2014) Chromothripsis: potential origin in gametogenesis and preimplantation cell divisions. A review. Fertility and sterility 102 (6):1785-1796.

- Chiang C, Jacobsen JC, Ernst C, Hanscom C, Heilbut A, Blumenthal I, Mills RE, Kirby A, Lindgren AM, Rudiger SR, McLaughlan CJ, Bawden CS, Reid SJ, Faull RL, Snell RG, Hall IM, Shen Y, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Daly MJ, Lee C, Morton CC, MacDonald ME, Gusella JF, Talkowski ME (2012) Complex reorganization and predominant non-homologous repair following chromosomal breakage in karyotypically balanced germline rearrangements and transgenic integration. Nat Genet 44 (4):390-397, s391. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Sapienza C (2001) Nonrandom segregation during meiosis: the unfairness of females. Mammalian Genome 12 (5):331-339. [CrossRef]

- Eisfeldt J, Pettersson M, Petri A, Nilsson D, Feuk L, Lindstrand A (2021) Hybrid sequencing resolves two germline ultra-complex chromosomal rearrangements consisting of 137 breakpoint junctions in a single carrier. Hum Genet 140 (5):775-790. [CrossRef]

- Hurst LD, Ellegren H (1998) Sex biases in the mutation rate. Trends Genet 14 (11):446-452. [CrossRef]

- Capilla L, Garcia Caldés M, Ruiz-Herrera A (2016) Mammalian Meiotic Recombination: A Toolbox for Genome Evolution. Cytogenet Genome Res 150 (1):1-16. [CrossRef]

- Romanenko SA, Perelman PL, Trifonov VA, Graphodatsky AS (2012) Chromosomal evolution in Rodentia. Heredity (Edinb) 108 (1):4-16. [CrossRef]

- Scriven PN, Handyside AH, Ogilvie CM (1998) Chromosome translocations: segregation modes and strategies for preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Prenat Diagn 18 (13):1437-1449.

- Zhang S, Lei C, Wu J, Sun H, Zhou J, Zhu S, Wu J, Fu J, Sun Y, Lu D, Sun X, Zhang Y (2018) Analysis of segregation patterns of quadrivalent structures and the effect on genome stability during meiosis in reciprocal translocation carriers. Hum Reprod 33 (4):757-767. [CrossRef]

- Mandáková T, Pouch M, Brock JR, Al-Shehbaz IA, Lysak MA (2019) Origin and Evolution of Diploid and Allopolyploid Camelina Genomes Were Accompanied by Chromosome Shattering. Plant Cell 31 (11):2596-2612. [CrossRef]

- Hochstenbach R, van Binsbergen E, Engelen J, Nieuwint A, Polstra A, Poddighe P, Ruivenkamp C, Sikkema-Raddatz B, Smeets D, Poot M (2009) Array analysis and karyotyping: workflow consequences based on a retrospective study of 36,325 patients with idiopathic developmental delay in the Netherlands. Eur J Med Genet 52 (4):161-169. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov Yu F, Kolomiets OL, Lyapunova EA, Yanina I, Mazurova TF (1986) Synaptonemal complexes and chromosome chains in the rodent Ellobius talpinus heterozygous for ten Robertsonian translocations. Chromosoma 94 (2):94-102. [CrossRef]

- Volleth M, Heller KG, Yong HS, Müller S (2014) Karyotype evolution in the horseshoe bat Rhinolophus sedulus by whole-arm reciprocal translocation (WART). Cytogenet Genome Res 143 (4):241-250. [CrossRef]

- Nunes AC, Catalan J, Lopez J, Ramalhinho Mda G, Mathias Mda L, Britton-Davidian J (2011) Fertility assessment in hybrids between monobrachially homologous Rb races of the house mouse from the island of Madeira: implications for modes of chromosomal evolution. Heredity (Edinb) 106 (2):348-356. [CrossRef]

- Tapisso JT, Gabriel SI, Cerveira AM, Britton-Davidian J, Ganem G, Searle JB, Ramalhinho MDG, Mathias MDL (2020) Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Contact Zones Between Chromosomal Races of House Mice, Mus musculus domesticus, on Madeira Island. Genes (Basel) 11 (7). [CrossRef]

- Potter S, Bragg JG, Blom MP, Deakin JE, Kirkpatrick M, Eldridge MD, Moritz C (2017) Chromosomal Speciation in the Genomics Era: Disentangling Phylogenetic Evolution of Rock-wallabies. Front Genet 8:10. [CrossRef]

- Giménez MD, Förster DW, Jones EP, Jóhannesdóttir F, Gabriel SI, Panithanarak T, Scascitelli M, Merico V, Garagna S, Searle JB, Hauffe HC (2017) A Half-Century of Studies on a Chromosomal Hybrid Zone of the House Mouse. J Hered 108 (1):25-35. [CrossRef]

- Chandley AC, McBeath S, Speed RM, Yorston L, Hargreave TB (1987) Pericentric inversion in human chromosome 1 and the risk for male sterility. J Med Genet 24 (6):325-334. [CrossRef]

- León-Ortiz AM, Panier S, Sarek G, Vannier JB, Patel H, Campbell PJ, Boulton SJ (2018) A Distinct Class of Genome Rearrangements Driven by Heterologous Recombination. Mol Cell 69 (2):292-305.e296. [CrossRef]

- Vara C, Paytuví-Gallart A, Cuartero Y, Álvarez-González L, Marín-Gual L, Garcia F, Florit-Sabater B, Capilla L, Sanchéz-Guillén RA, Sarrate Z (2021) The impact of chromosomal fusions on 3D genome folding and recombination in the germ line. Nature communications 12 (1):1-17.

- Pochon G, Henry IM, Yang C, Lory N, Fernández-Jiménez N, Böwer F, Hu B, Carstens L, Tsai HT, Pradillo M, Comai L, Schnittger A (2023) The Arabidopsis Hop1 homolog ASY1 mediates cross-over assurance and interference. PNAS Nexus 2 (3):pgac302. [CrossRef]

- Veller C, Kleckner N, Nowak MA (2019) A rigorous measure of genome-wide genetic shuffling that takes into account crossover positions and Mendel's second law. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116 (5):1659-1668. [CrossRef]

- Lam I, Keeney S (2014) Mechanism and regulation of meiotic recombination initiation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7 (1):a016634. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli K, Oliveros W, Gerhardinger C, Andergassen D, Maass PG, Rinn JL, Melé M (2020) Cis and trans effects differentially contribute to the evolution of promoters and enhancers. Genome biology 21 (1):1-22.

- Pennisi E (2023) Stress responders. Science 381 (6660):825-829. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).