1. Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a chromosome instability syndrome affecting 1 to 5 individuals per 1,000,000 individuals. FA is also the most frequently inherited bone marrow failure syndrome and originates from the inheritance of pathogenic variants (PV) in one of any 22 genes (FANCA-FANCW) that operate in the FA/BRCA pathway, responsible for recognizing and repairing DNA interstrand cross-links (ICL), through homologous recombination, an error-free pathway of DNA repair [

1,

2]. In absence of a functional FA/BRCA pathway, the ICLs can be repaired by low-fidelity DNA repair pathways, such as the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or the microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathways [

3,

4] which rescue cell viability at the expense of increasing chromosome instability (CIN). The latter is a pathognomonic feature of FA, which allows its diagnosis due to the exquisite sensitivity of FA cells to ICLs inducing agents, like mitomycin C (MMC) and Diepoxybutane (DEB) [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8].

The FA clinical phenotype is highly heterogeneous affecting multiple organs and systems. The phenotype includes, developmental abnormalities that can be detected since birth and are present in 80-96% of patients [

9,

10]; bone marrow (BM) failure, which appears in over 86% of patients with FA and consists of aplastic BM accompanied by peripheral blood cytopenias of different degrees mild, moderate or severe; patients with FA will develop BM failure around 7 years of age [

10,

11]. Also, FA patients are prone to develop cancer, both hematologic and solid tumors, with a cumulative incidence by 40 years of age of 30-33% and 20-28%, respectively [

12,

13]. The relative risk for a patient with FA to develop cancer, with respect to the general population is 19X and rises post HSC transplant to 55X; specifically, 527X for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) and after transplant 933X; 582X for vulvar squamous cell carcinomas, after transplant 6298X; 213X for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and 5669X for myelodysplastic neoplasia (MDS). The risk for hematological cancer, MDS and AML, increases by the age of 10 years old, plateauing at 20-30 years old [

13,

14].

BM failure in FA has been proposed to be the consequence of damage accumulation in the DNA of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and hyperactivation of growth suppressing pathways, such as the TGFβ (Transforming growth factor β) and the p53/p21 pathways, thus resulting in critical reductions in the number of HSPCs [

15,

16]. Despite this harsh BM microenvironment, certain HSPCs thrive, probably due to the inherent CIN in FA, and the acquisition of chromosome abnormalities that allow temporary survival, although not in the long-term.

CIN, one of the hallmarks of cancer, is characterized by aneuploidy and structural chromosomal abnormalities (CA), and can be observed in the early stages of cancer in the general population [

17,

18,

19]. Importantly, CIN is a constant in FA patients, since zygote formation and embryonic development, it produces single cell genomic variation in the form of heterogeneous karyotypes and has the potential to produce across the body of patients with FA, diverse altered genomes with short-term survival and elevated level of cell death, leading to the loss of somatic and HSPS cells, [

20,

21] however, this karyotypic heterogeneity and its inherent proapoptotic tendency, might also be the foundation for the well-known appearance of clonal hematopoiesis and eventual progression to cancer in FA [

21,

22]. The latter might be the reason why up to 40% of children and young patients with FA show signs of clonal evolution in their BM, and 15 to 60%, will develop MDS or leukemia, mainly AML, at an early age [

2,

23].

Multiple studies have described, and confirmed, the involvement of clonal chromosome abnormalities (CCA) in the emergence of MDS or AML in patients with FA [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Most of these studies screened for common CCA using microarrays or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) directed to regions of interest in chromosomes 1q, 3q and 7q, since these are the most informative cytogenetic markers of clonal evolution towards MDS/AML [

23,

28,

29]. Cytogenetic analysis, however constantly misses or discards non-clonal chromosome aberrations (NCCA), as they are considered "background noise", specially in patients with CIN, as is the case for FA [

23].

Cancer evolution, however, is known to be a dynamic process, directed by large-scale chromosomal copy number variations that create karyotypic heterogeneity between the cells that compose a tissue, privileging the selection of the genomes with the greatest fitness [

17], eventually leading to the selection of clones with CCA that will orchestrate cancer development and evolution [

17,

30]. FA inherent CIN is expected to create large levels of NCCA, generating a BM with high karyotypic heterogeneity years before full-blown MDS or AML. In this sense, NCCA could precede the formation of complex genomes and stable CCAs eventually transitioning to cancer.

The aim of this study was to cytogenetically analyze the BM of a group of non-transplanted patients with FA, to investigate whether the multiple steps of karyotypic evolution towards cancer can be appreciated, in relation to the age of the patients and their hematological condition. We did not find an association between the complexity of the BM karyotype and the age of the patients or their hematological condition, suggesting that age and stage of bone marrow failure are not the only drivers of leukemogenesis in FA. However, inspecting the group of FA patients as a whole, revealed transitions from a karyotypically diverse population of BM cells with NCCA, to the presence of complex karyotypes, and emergence of CCA involving CA of indeterminate potential in patients with FA [

29] and CCA with the classic high risk chromosome alterations found in chromosomes 1, 3, and 7; the only two patients in the group who were identified with MDS presented with the classic alterations in chromosomes 3 and 7.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

We performed a transversal study including non-transplanted patients with a confirmed diagnosis of FA with the DEB chromosome breakage test. The samples analyzed corresponded to the first cytogenetic BM evaluation of each patient within the framework of the recommended annual follow-up in search for MDS/AML progression markers. All samples were processed at the Cytogenetics Laboratory of the National Institute of Pediatrics (Mexico) between 2015 and 2024. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all patients or their relatives gave written informed consent for genetic analyses under project number INP 2014/041 and 2020/012; clinical and demographic data were obtained from the patient’s medical records and from interviews conducted in the frame of the Fanconi Anemia Registry from Mexico (RAFMex) project INP 2020/053. These projects were approved by the institutional research and ethics committees at Instituto Nacional de Pediatría (México).

Age at diagnosis was calculated considering the date of positive DEB test. BMF severity at the time of cytogenetic study was classified according to Fanconi anemia guidelines for diagnosis and management [

31], using the hemogram data (free of transfusion) nearest to the cytogenetic study. The use of androgens was recorded irrespective of the length of treatment or if it was being taken at the time of sample collection. Transfusion dependency was considered when the patient could not maintain adequate blood counts without sequential transfusions at any timepoint.

2.2. Cytogenetics

Conventional karyotypes were performed on BM cells using the standard direct method. Briefly, 1-2 mL of heparinized BM samples were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator, cultured during 48 h in MarrowMax medium without cell division stimulant at 37°C, after which colcemid [10 μg/mL] was added for the final 2 h of culture. Harvesting, slides preparation and GTG banding were made according to the classic methodology [

32]. On average, 20 metaphase spreads were analyzed per patient and reported according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) [

33], less than 18 metaphases were analyzed in four patients with severe aplastic anemia due to hypocellular BM.

Chromosome abnormalities were classified as: a) NCCA, non-clonal chromosomal abnormality, both numerical and structural; b) Complex karyotype (CK), defined in this study as a cell with ≥3 independent cytogenetic abnormalities [

34]; c) CCA, clonal chromosomal abnormalities, when at least two cells bear the same chromosome gains or structural rearrangements (including deletions and duplications), or when at least three cells present with the same whole chromosome loss [

33]. CCA 1,3,7 refers to clonal abnormalities involving at least one of the known recurrent alterations: i.e. duplication of the long arm of chromosome 1 (commonly known as 1q+), duplication of the long arm of chromosome 3 (commonly known as 3q+), complete monosomy of chromosome 7 or deletion of the long arm of chromosome 7 (commonly known as -7/7q-), while CCA refers to clonal chromosome alterations in chromosomes other than 1q+,3q+ and -7/7q-. When aneuploidies of a whole chromosome were detected at a given metaphase, and to reduce potential technical errors, the periphery of such metaphase was analyzed with a 10x objective to increase the visibility margin by 10 fields and to detect whether the lost chromosome was located at the periphery of the metaphase, or whether the gained chromosome belonged to a nearby metaphase. Chromosome breaks and radial exchange figures were recorded during the screening but are not part of the analysis in this report.

2.3. Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in Prism (version 10.4.0). Normal distribution of the data was assessed with the Shapiro Wilk test. Data with normal distribution were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test for multiple comparisons. Comparisons between two groups were performed with the unpaired t test. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions between two groups. Pearson correlation test was used to probe correlation between age and frequency of chromosome abnormalities.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

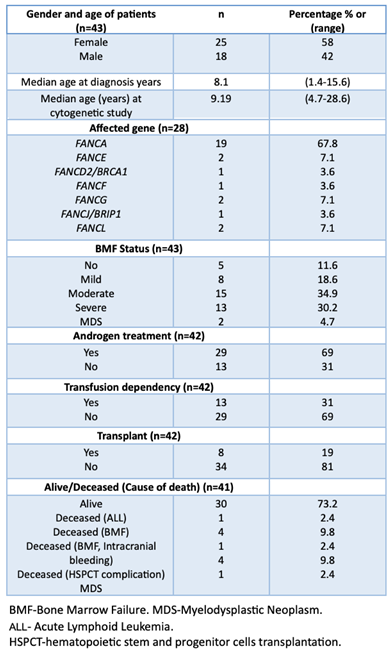

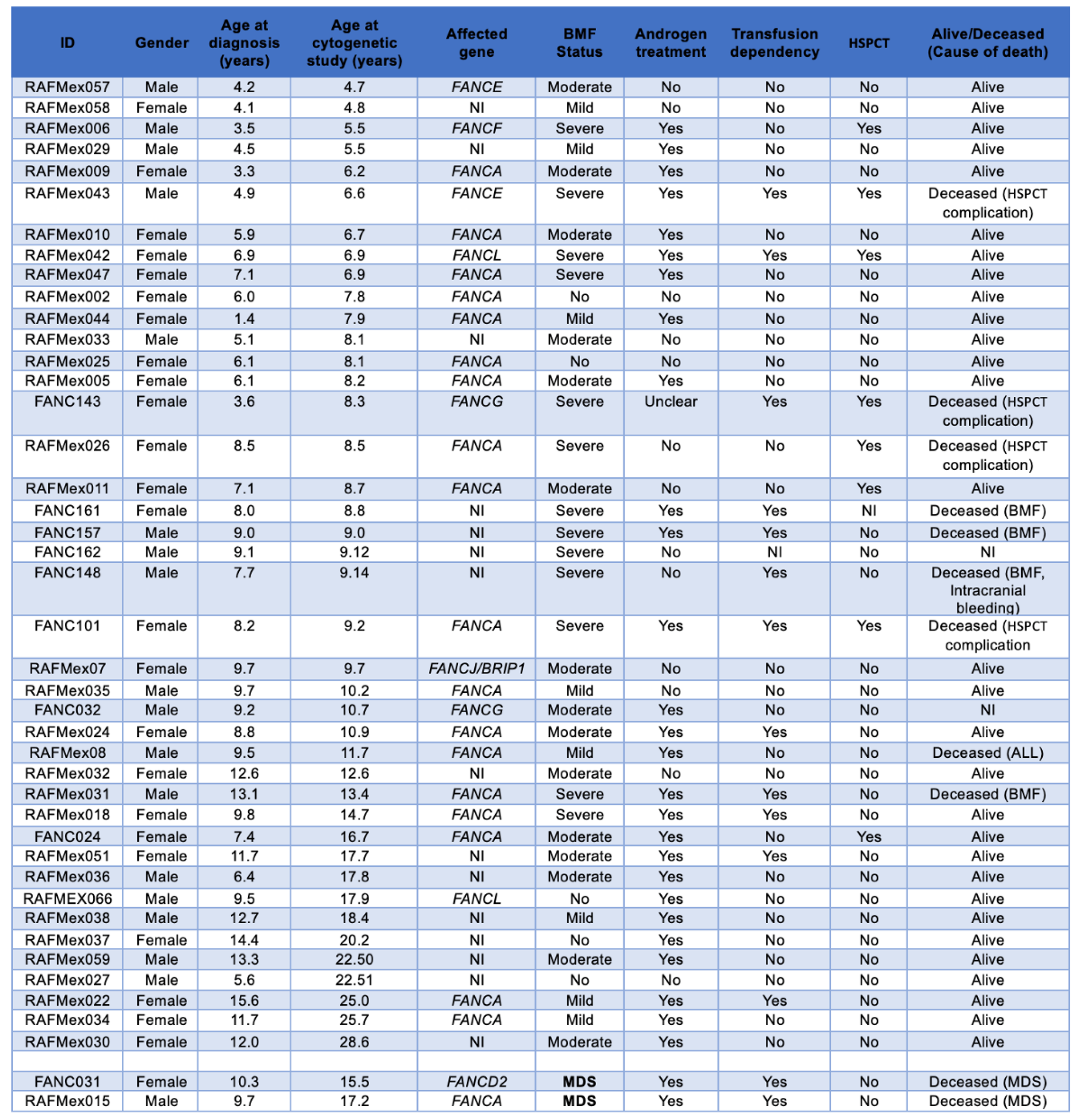

Samples from 50 non transplanted patients with a positive diagnosis of FA, were sent to the cytogenetics Laboratory at Instituto Nacional de Pediatría (Mexico) for routine annual follow-up between 2015 and 2024; six of them had insufficient material to perform cytogenetic analysis, one patient was excluded since the provided sample was obtained once antineoplastic treatment for AML was started. Appropriate cells, in quality and number, for cytogenetic analysis were obtained from 43 patients (Table S1); in two of them (FANC031 and RAFMex015) the concurrence of cytopenia and a monosomy of chromosome 7 clone allowed the diagnosis of MDS in accordance with International Consensus Classification criteria (CITAR PMID: 35767897). During the duration of this study, some of the patients had more than one cytogenetic analysis on more than one sample, only the first cytogenetic study was considered for the purposes of this report.

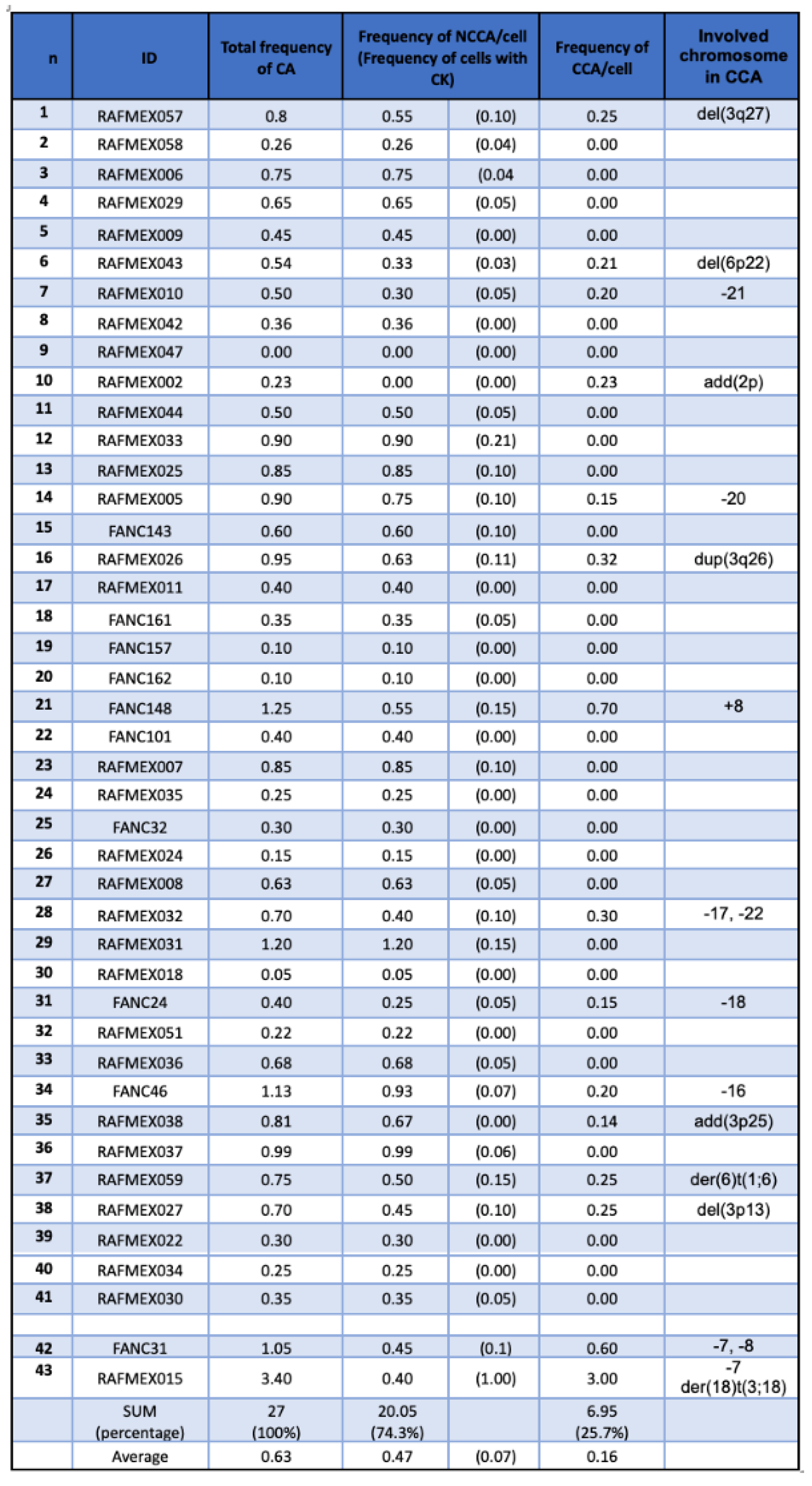

Median age at diagnosis was 8.1 (1.4-15.6) years old, and median age at the cytogenetic study was 9.14 (4.7-28.6) years old, with a female-male relationship 1.4:1. A summary of the population demographics is shown in

Table 1, and main clinical data are shown in

Table 2. Eleven patients died during the elapsed time between cytogenetic study and this report: due to BM failure or HSCT-related complications in eight patients, MDS in two patients and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in the remaining one.

3.2. BM Cytogenetics of Patients with FA

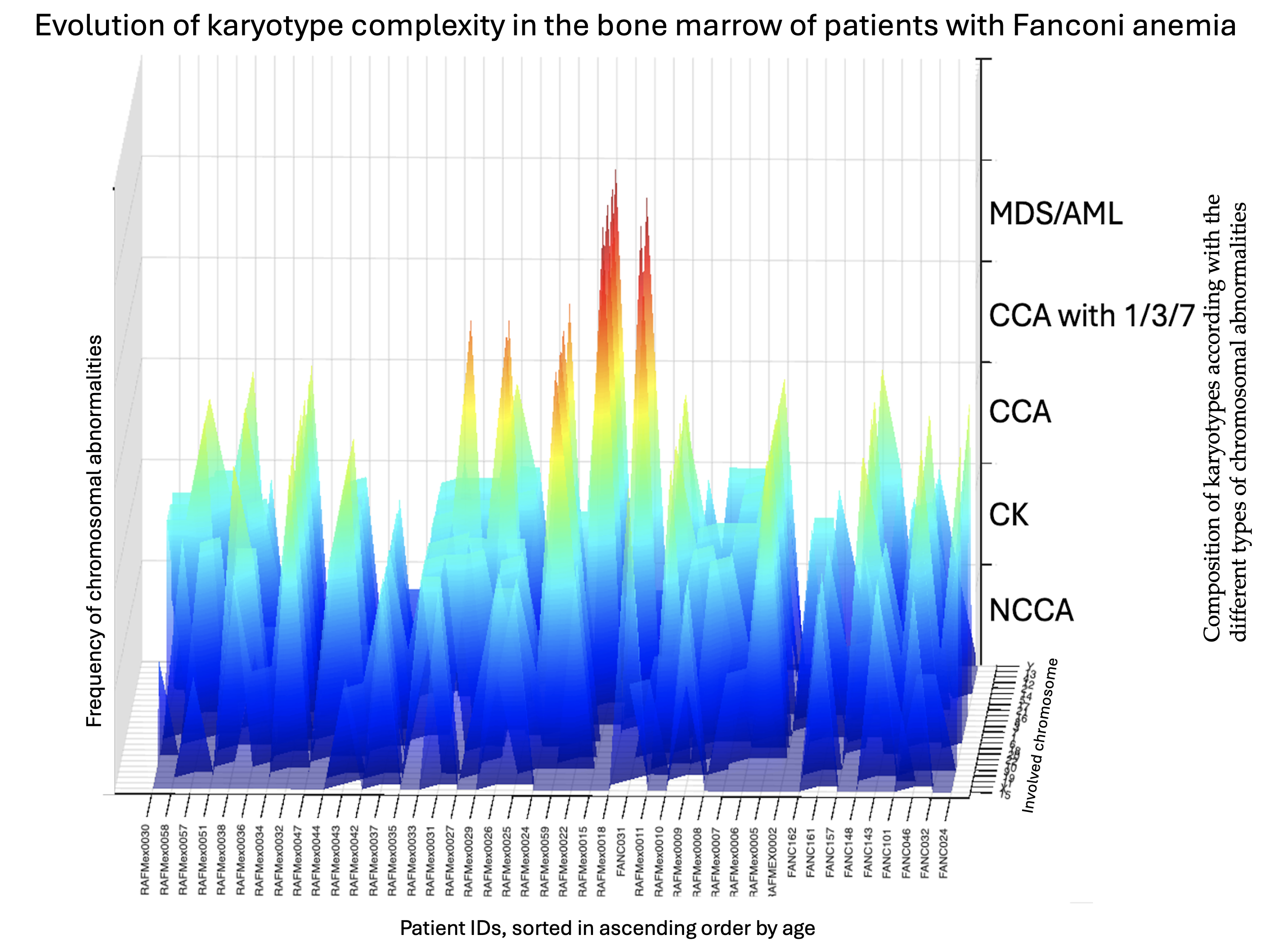

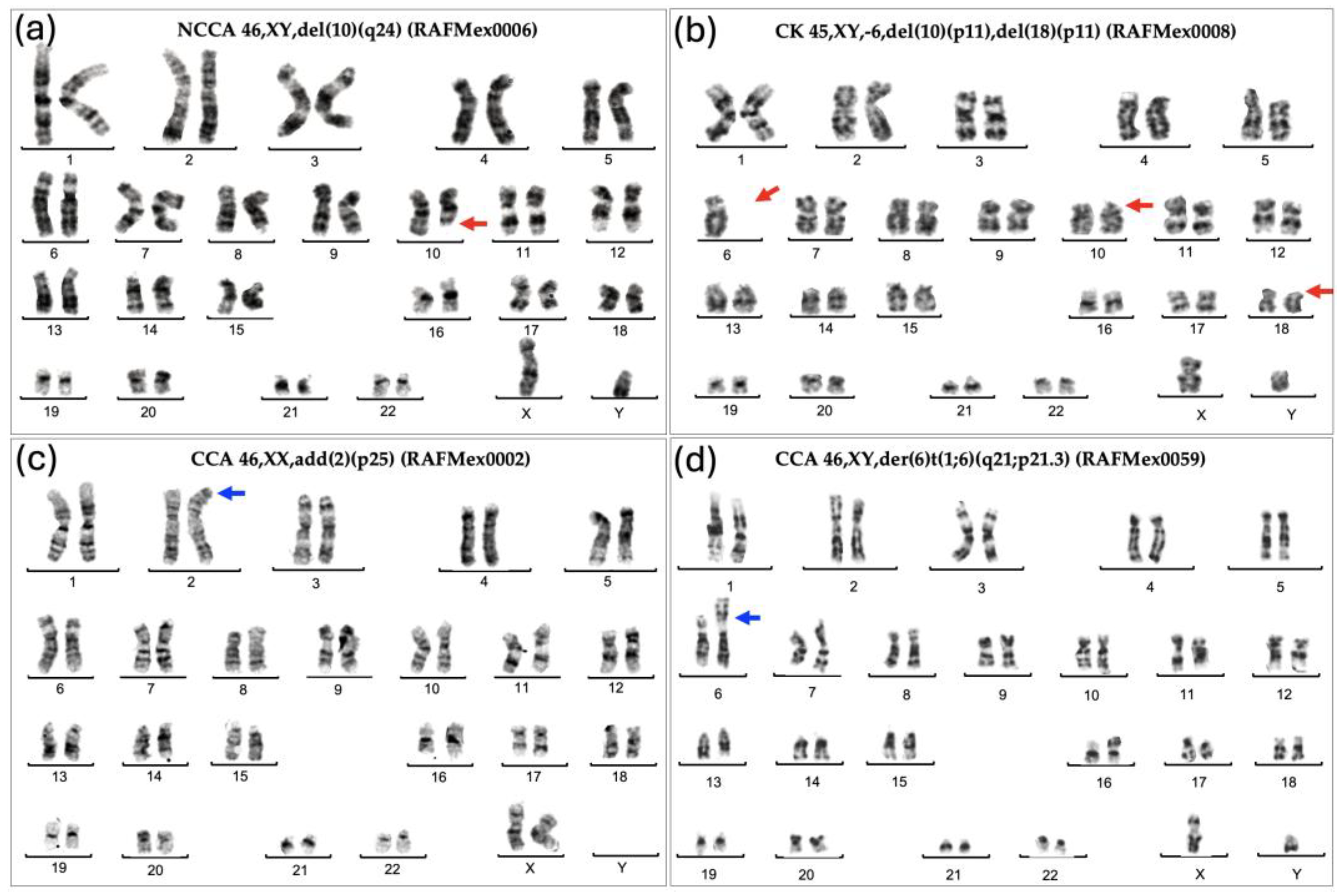

As expected for patients with FA, their BM showed enormous karyotypic heterogeneity, evidencing the underlying CIN. The cytogenetic analysis in the 43 included patients, showed that all but one patient displayed chromosomal abnormalities, that were classified in three types, NCCA, non recurrent CK, and CCA. Representative karyotypes per CA type are shown in

Figure 1.

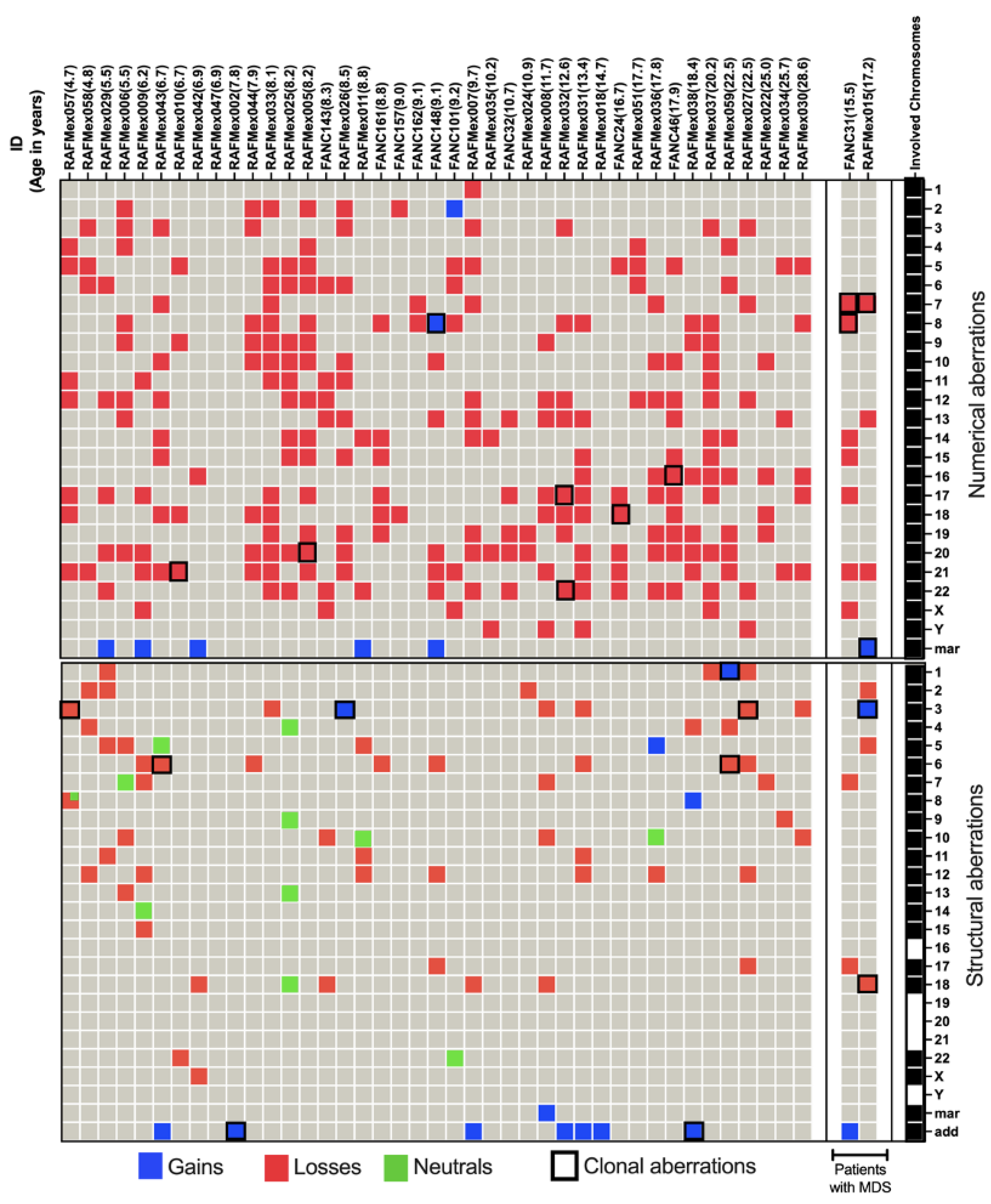

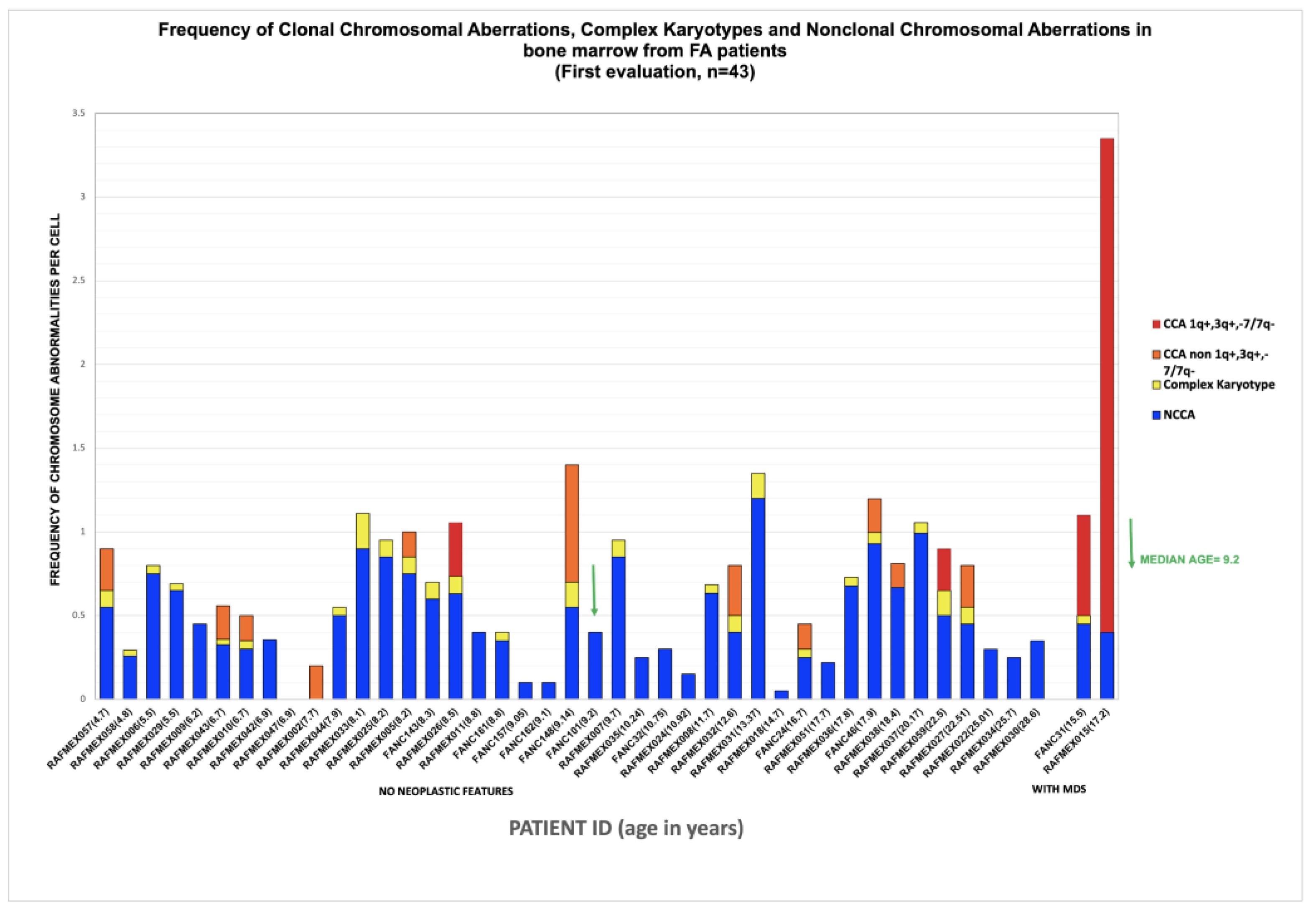

NCCA were observed in 41/43 patients; karyotypes were NCCA were the only findings occurred in 26/43 patients, the presence of only CCA was observed in a single patient; and the combination of both NCCA and CCA were observed in 15/43 patients. In addition, 25 patients presented with non recurrent CK. Among the 15 patients with CCA, eight had clones with aneuploidy for one complete chromosome, six had clones with structural chromosomal aberrations and one patient had clones with both types of chromosomal aberration (Figure 2). Chromosome losses were more commonly observed in comparison to chromosome gains. The chromosomes more frequently involved in any kind of CA were chromosomes 3, 7, 8 and 18, followed by chromosomes 6, 16 12, 17, 20 and 22; also, we found additional material (add), marker chromosomes (mar) and neutral aberrations like inversions and balanced translocations (Figure 3 and Table 3).

3.2.1. Non Clonal Chromosomal Abnormalities

Patients with inherent CIN, such as FA, are expected to have enormous karyotypic heterogeneity, this was evidenced in their BM where stochastic chromosomal alterations were found (

Table 3 and

Figure 2). All 24 human chromosomes were involved in these CA, numerical aberrations were the most common (

Figure 3).

NCCA were observed in the vast majority of FA patients, 95% (41/43), including non recurrent CK. NCCA, without evidence of any additional chromosomal clones were found in 26 patients. NCCA were the most prevalent type of CA, accounting for 74.6% of the total abnormalities observed, and included CK in 25/43 patients, which most of them were non-recurrent. Patient RAFMex015, was exceptional, since clonal and complex karyotypes were found in 100% of the analyzed cells, concurrent with an MDS diagnosis (Table 3 and Figure 2).

In most patients, NCCA were the most frequent CA, these were highly diverse and included numerical and structural alterations. Among the structural CA, 11/78 were neutral in that they did not appear to condition a loss or gain of chromosome information; most were inversions but there was also one translocation (

Figure 3, green cells).

3.2.2. Clonal Chromosomal Abnormalities (CCA)

CCA accounted for 25.4% of the total CA found in the 43 patients with FA (Table 3), they were found in 35% (15/43) among these the presence of CCA involving monosomy of chromosome 7 in two of these patients led to a MDS diagnosis. Within the 15 patients which presented with clonal chromosome abnormalities (WC), seven presented clones consiting of whole-chromosome aneuploidy, losses involving chromosomes 7, 8, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21 and 22; gains involving chromosome 8, and/or a marker chromosome. Seven patients had clones with structural CA in chromosomes 1, 3, 6 and 18, and one patient presented a clone with both numerical (chromosomes 7 and +mar) and structural (chromosomes 3 and 18) CA. Among 15 patients WC, 11 presented CCA involving autosomes other than 1,3 and 7, and in 4/15 patients WC, the clone involved the regions on chromosomes 1, 3 and 7 associated with the evolution towards hematological malignancy; one of them had a duplication 1q21-qter, due to a translocation t(1;6)(q21;p21.3). Patients WC, in addition to having cytogenetic clones, revealed a variety of NCCA: 3/15 had whole-chromosome aneuploidies, 11 had numerical and structural NCCA, and only one patient did not present NCCA (Figure 3 and Table 3).

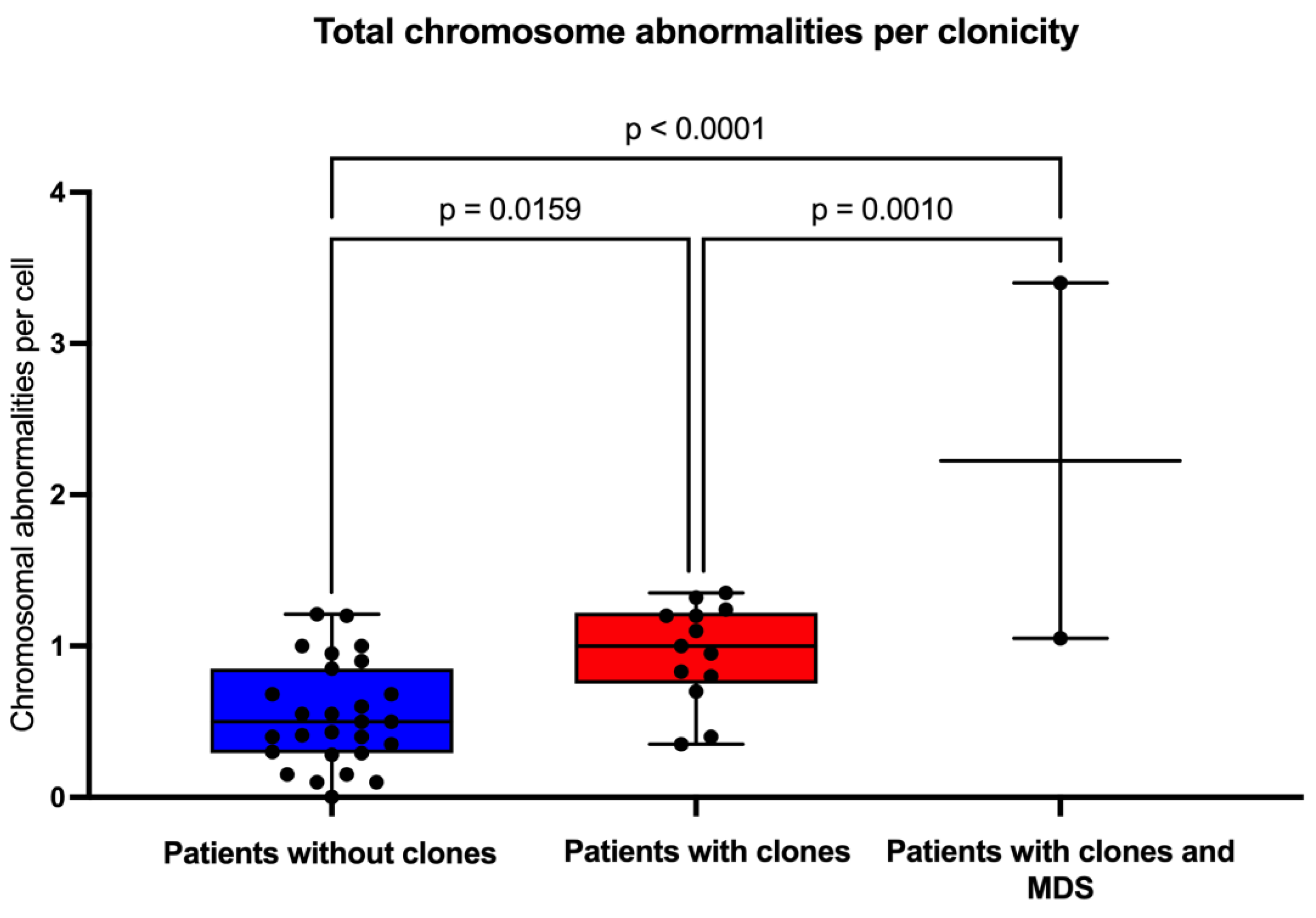

3.3. Clonicity and Chromosomal Damage

In this group of patients, we found that the average frequency of CCA (0.16) is only ~20% of the observed average frequency of NCCA (0.47) (

Table 3), in addition, it is evident that when the total frequency of ab/cell is higher, CCA appears in a patient (

Figure 4). In patients WC who have MDS, a large number of CA are observed in their BM, because the fittest clone is present in a large proportion (

Figure 1 and

Figure 4). In patients WC, CCA alterations coexist with NCCA, although the latter are generally the most common alteration. However, it should be noted that in the two patients who already present MDS, CCA prevail over NCCA (

Figure 2).

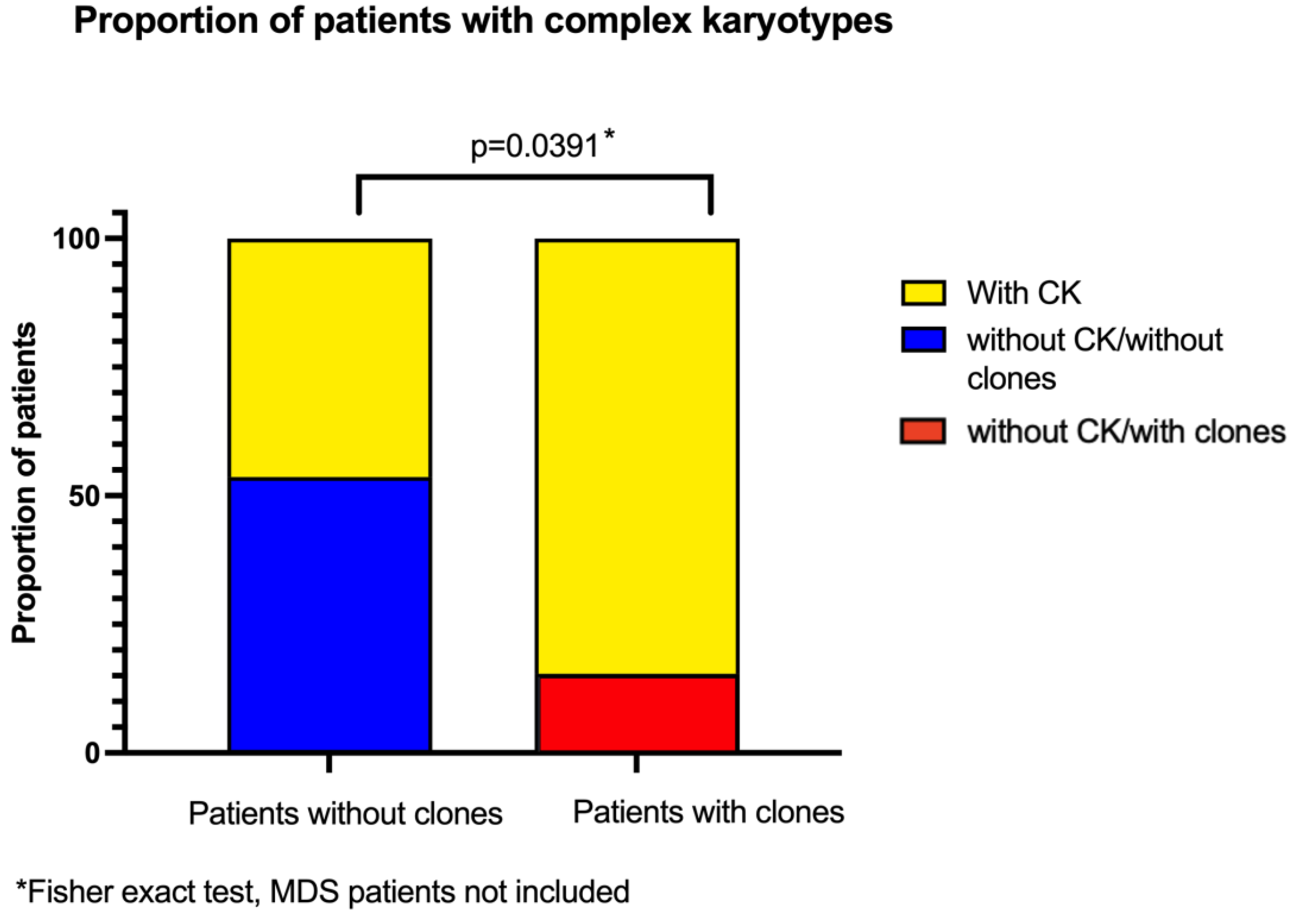

3.4. Complex Karyotypes and Clonicity

Several analyzed metaphases had more than one CA, we classified the patients that had at least one metaphase that had three or more CA as having a CK. Twenty five out of 43 patients had metaphases with these CK, which represent a greater complexity within the population of cells with NCCA. When comparing the frequency of CK in patients with and without clones, there is a higher proportion of patients with CK among those who have already developped clones, showcasing an increased complexity of the diverse karyotypes found in their BM (

Figure 5).

3.5. Chromosomal Damage and Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

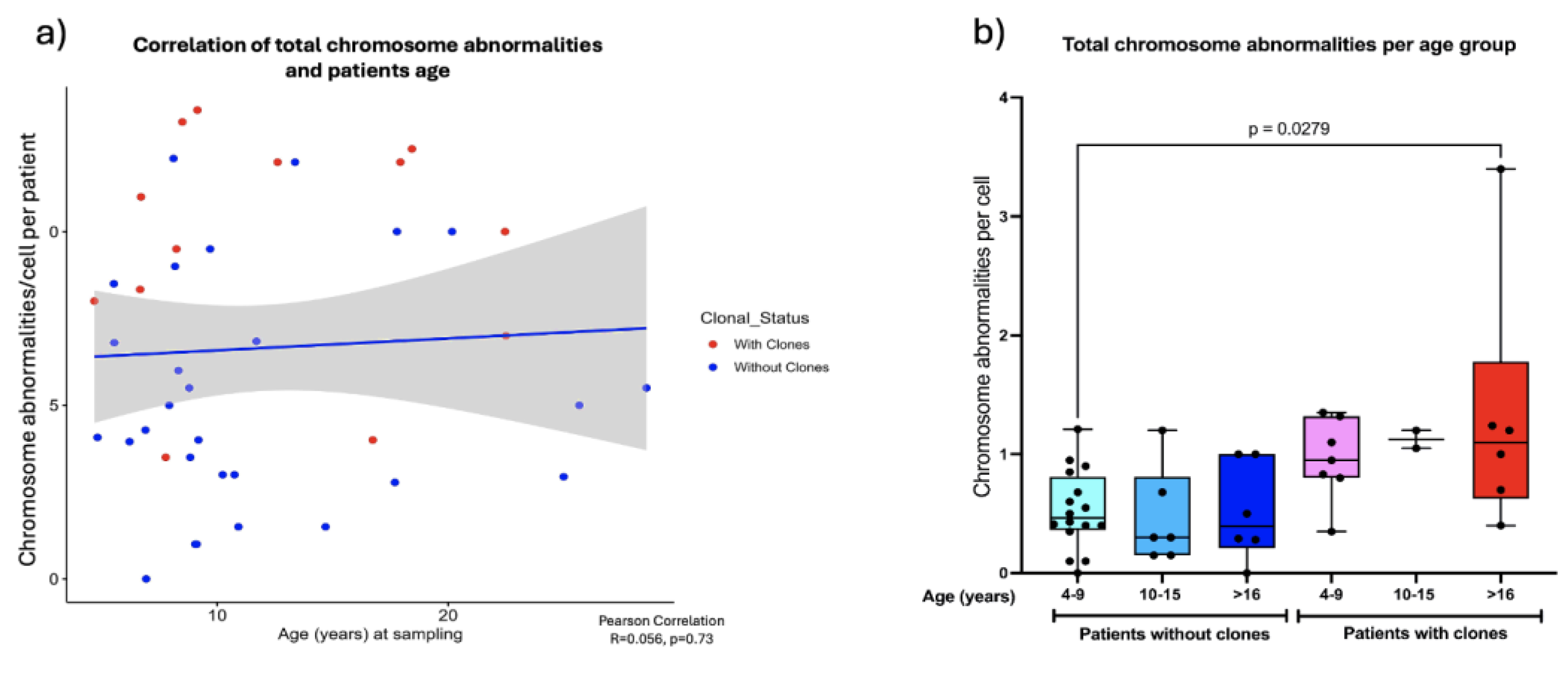

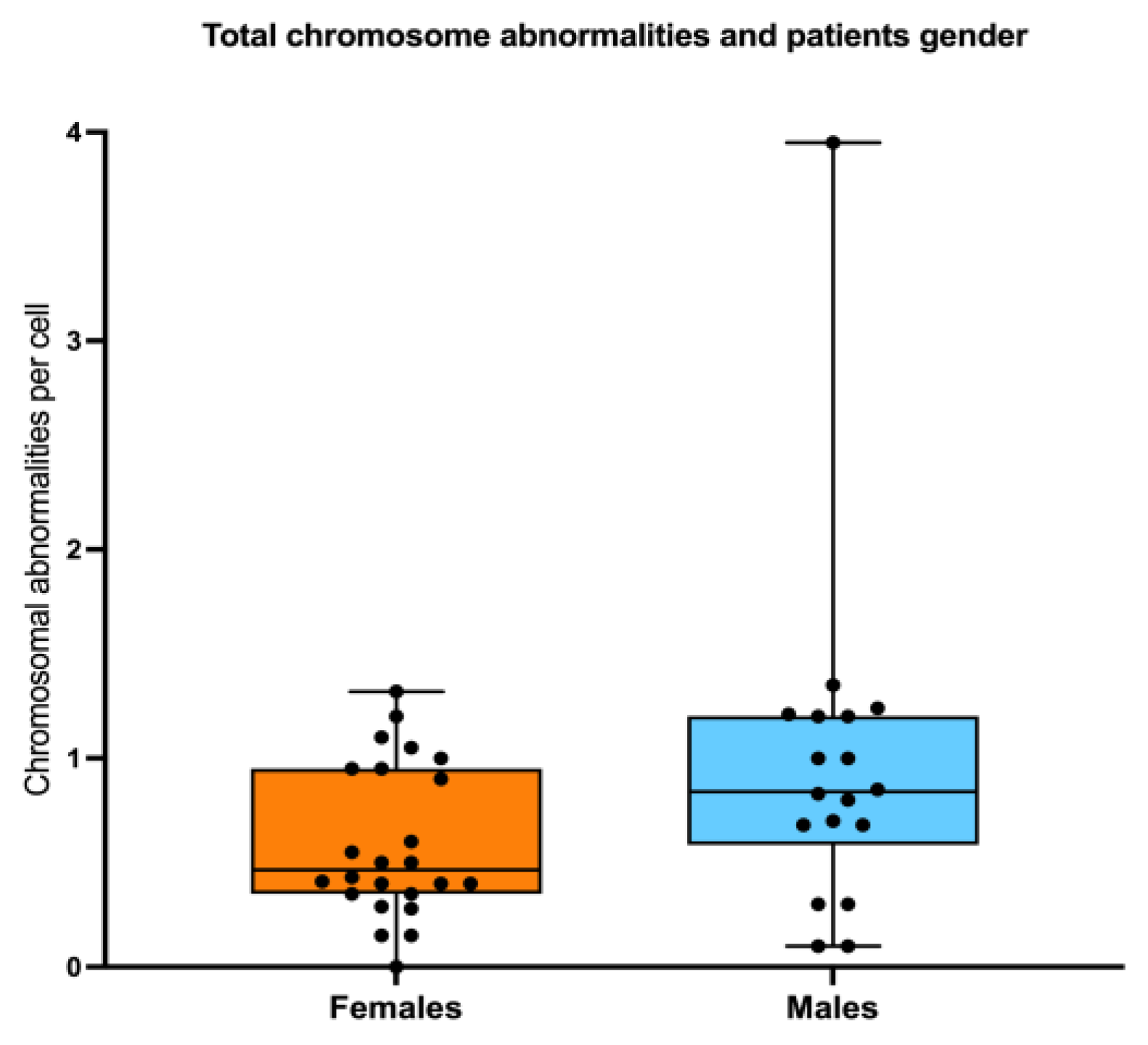

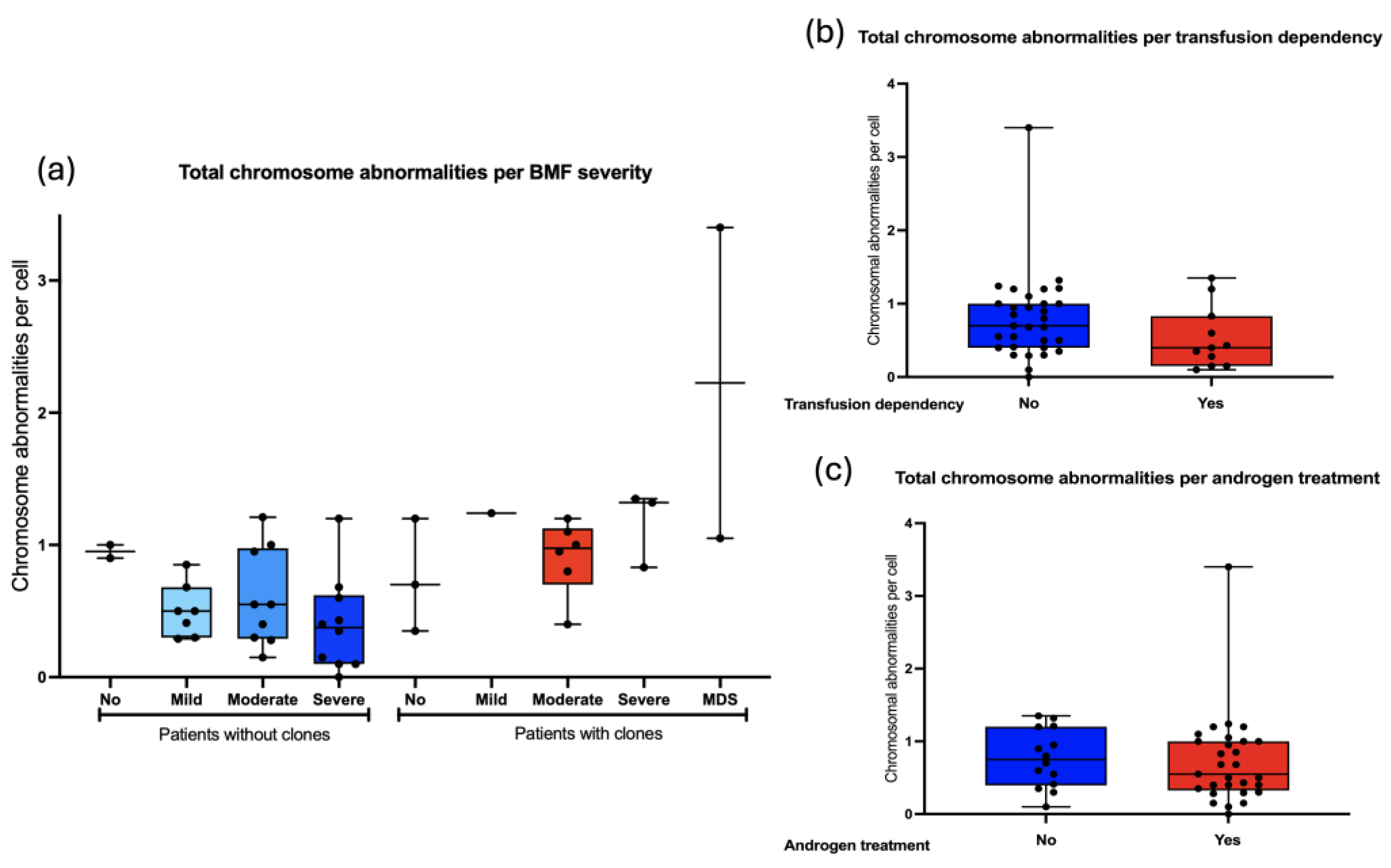

3.5.1. Chromosomal Abnormalities and the Age and Gender of Patients

Pearson correlation analysis revealed that as the patients grow older the total frequency of CA does not increase, (R=0.056, p=0.73) (

Figure 6a). However, when patients were sub-divided into three groups of age: 4 -9 years old, 10-15 years old and >16 years old, a significantly higher frequency of CA was observed between the older patients WC (excluding MDS patients) and the younger patients without clones (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test) (

Figure 6b), Finally, There were no significant differences in AC frequency when comparing males and females. (

Figure 7).

Finally, we search for an association between the frequency of chromosomal aberrations and the bone marrow failure severity: 5/43 did not have BMF, 28/43 had moderate or severe BMF. As a group, the patients with WC show slightly more CA than WOC, and although no statistical differences were found it would appear that in individuals WC, CA would increase as the BMF becomes more severe. (

Figure 8a). Other parameters regarding to the hematological status, including transfusion dependency and androgen treatment, did not influence the total frequency of CA observed in patients with FA. (

Figure 8b and 8c).

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a cytogenetic cross-sectional analysis of the BM of 43 patients with the chromosome instability and cancer predisposition syndrome FA. As anticipated, a high number of CA were observed in virtually all participants. NCCA were the most prevalent, reflecting an underlying karyotype heterogeneity caused by faulty DNA repair mechanisms in individuals with FA. CCAs, mostly abnormalities of indeterminate potential, were also observed, with high-risk CAs being detected in four patients, two of whom had MDS defining CAs. This comprehensive analysis of the type and frequency of CA in the BM of individuals with FA, stresses out the natural history of hematological cancer in FA, from heterogeneous NCCA towards CK, and finally CCA and cancer. This study complements the information on the genomic changes involved in the evolution towards hematological cancer, which has been extensively studied by other authors [

21,

22,

29], given that we analyzed the chromosomes of pre-leukemic BM and at the individual cell level, revealing the presence of NCCA in addition to CCA.

As shown in Figure 3, the observed NCCAs included both structural alterations and aneuploidies (gains and losses of whole chromosomes). Structural alterations included gains of chromosome material and chromosome deletions. Specifically, chromosome gains may arise from the joining of non-homologous chromosome segments through the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway, causing chromosome translocations. Additionally, the segregation of radial exchange figures during mitosis, could produce daughter cells harboring single derivative chromosomes (with the corresponding gain and/or loss of chromosome material). On the other hand, chromosome deletions, on the other hand, were six times more frequent than gains. Their origin could be chromosomal rearrangements, or non-repaired double-strand breaks (DSB) that reached mitosis, and whose broken segment was not retained in the same cell after exiting mitosis, leaving a deleted chromosome.

We saw an overrepresentation of loss-of-chromosome aneuploidies, raising the possibility of technical errors during the preparation of metaphase spreads, nonetheless given our strict scoring criteria during chromosome analysis (see methodology), we consider that most of these alterations are genuine chromosome numerical losses. In this context of genomic instability, we hypothesize that chromosome losses are related to the mis-segregation of structurally altered chromosomes that became incorporated into micronuclei and further shattered, as others have shown to occur with lagged chromosomes [

35].

Interestingly, we also identified neutral CA, i.e. balanced CA such as chromosome inversions and translocations. Traditionally, these alterations were thought to be less detrimental than deletions and duplications, but it is now recognized that they can have a significant impact in the cancer evolution, since the change in the 3D distribution pattern of genes and regulatory elements addresses is responsible for emerging network dynamics [

36]. Inversions are not commonly reported in previous cytogenetic studies of patients with FA, most likely because cytogenomic analysis using microarrays is usually preferred over GTG banded chromosomes. are not typically analyzed [

22]. These inversions could result from the presence of two DSBs in the same chromosome that were rejoined after a 180-degree rotation. Other mechanisms may also explain the presence of inversions, including chromothripsis-like rearrangements, but with fewer breakpoints than traditional chromothripsis, which usually involves extensive fragmentation and rearrangement of a single chromosome. It is known that an intact FA/BRCA pathway plays a crucial role in the micronucleus-related chromosome fragmentation that leads to chromothripsis, while a deficient FA/BRCA pathway generates significantly less chromosome fragmentation under similar conditions [

35]. This type of alterations evidenced here by G banding, may represent just the tip of the iceberg of more complex ACs, which deserve further study.

Of note, NCCAs in FA are quite variable from cell to cell, and this is probably due to multiple factors, including: first, a continuous generation of DSBs, that are incorrectly and not homogeneously rejoined due to the reliance of the FA cells on error-prone DNA repair pathways [

4]. Second, dividing cells harboring NCCAs will not parent chromosomally identical daughter cells, particularly when dicentric chromosomes and radial figures are present, as mitotic segregation will not equally distribute the CAs into the daughter cells [

2]. Third, NCCA might confer differential surviving capacities, therefore alterations incompatible with life will not thrive, while fitness providing CAs will persist, in a constant cycle of cell replacement and cell attrition. During this cycle of depletion and emergence of cells with NCCAs, new genome compositions in the tissue will arise, producing a unique combination of CAs that will benefit the survival of cells harboring stable karyotypes with CCA.

Cells carrying a specific CCA can be considered the evidence of a successful genome arrangement. However, this specific clone could also be transient, as the continuous production of CAs does not cease, leading to the emergence of CK, most of which are NCCA. Some CK may appear in cells that already contain a specific CCA, generating genomes that may either disappear or adapt, eventually evolving towards a clone with higher fitness. In a cell population exhibiting CIN, NCCAs will create dynamic karyotypic diversity. This heterogeneity of cells, with stochastic CA, eventually gives rise to CCA, which may be transient, creating a dynamic cycle of NCCA/CCA. The NCCA/CCA cycle establishes a macro evolutive phase that may continue until emergency of stable clones that encompasses a phase transition. One surviving genome with CCA carrying high-risk CAs emerge, such as clones with dup(1q), dup(3q), del(7q), and -7 and the accompanying NCCAs decrease (as in patients with MDS). Clonal expansion is characteristic for the microevolutionary phase [

37]. These specific karyotype alterations are known to facilitate the progression to cancer. The cells with these Cas will proliferate until they become a clone, thus completing the transition from NCCA to CCA. In patients with FA, the transition to cancer also involves specific genetic alterations such as RUNX1 and TP53, among others [

22].

Importantly, progression towards cancer, which typically takes a long time in DNA repair proficient individuals, is accelerated in patients with FA. In this work, through an in-depth cytogenetic analysis of the BM of patients with FA, we recapitulate macroevolution patterns previously described [

23,

30,

31], including an initial phase of high karyotypic heterogeneity leading to more stable "end products of evolution", i.e. CCA abnormalities that combine large-scale chromosomal changes with genetic mutations and copy number alterations, that will ultimately drive micro-evolution steps towards cancer.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we observed that the frequency of ACs was not associated with gender, bone marrow failure, or treatment. The frequency of NCCA and CCA increased with age; although no significant correlation was found, a significant difference was observed between older patients with CCA and younger patients without CCA.

In general, the preleukemic bone marrow of patients with FA exhibit significant basal karyotypic heterogeneity, evidenced by the widespread presence of NCCA. This karyotypic heterogeneity precedes the eventual appearance of CK and the selection of CCA-bearing cells that enhance adaptation, which may be transient until the appearance of a stable CCA. The NCCA/CCA cycle establishes a macroevolutionary phase that could continue until the emergence of stable clones, leading to a phase transition. A surviving CCA genome harboring high-risk ACs emerges, such as clones with dup(1q), dup(3q), del(7q), and -7, and the associated NCCAs decline. These observations fit the model of evolution towards cancer that comprises a first phase of macroevolution represented by NCCA and karyotypic heterogeneity, followed by the establishment of clones with CCA, which leads to microevolution and cancer.

These observations warrant a longitudinal follow-up study of patients with FA to determine the macro- and microevolutionary phases and to detect potential cytogenetic biomarkers that precede clonal hematopoiesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1. Data Base containing the Cytogenetics of 43 patients with FA. Complete data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.; S.S.; B.G.; methodology, S.F.; S.S.; formal analysis, S.F.; S.S.; B.G.; M.O.F.; A.R.; investigation, S.F.; S.S..; B.G.; P.R.; A.P; M.A.M.; B.M. resources, B.G.; A.M.; M.O.F.; B.M.; U.J.; L.T.; data curation, S.S.; B.G. writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; S.S.; B.G.; writing—review and editing, S.F.; S.S.; B.G.; A.R.; visualization, S.S.; B.G.; B.M; P.R.; A.R.; supervision, S.F.; S.S.; B.M.; U.J.; L.T.; B.G.; A.M.; project administration, S.F.; B.M.; funding acquisition, S.F.; B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM-PAPIIT, grant number IN205120; Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías, Grant number CF-2023-G-800; Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Recursos Fiscales, Projects 2020/012 and 2020/053. The APC was funded by XXX”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Pediatría (protocol code 2014/041 approved on July 14th, 2014, 2020/053 and 2020/012 approved on March 23rd, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rodríguez, A.; D’Andrea, A. Fanconi anemia pathway. Curr. Biol. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García-De-teresa, B.; Rodríguez, A.; Frias, S. Chromosome instability in fanconi anemia: From breaks to phenotypic consequences. Genes (Basel). 2020, 11, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Zambrano, C.; Yuste, M.; Frías, S.; García de Teresa, B.; Mendoza, L.; Azpeitia, E.; Rodríguez, A.; Torres, L. A Boolean network model of the double-strand break repair pathway choice. J. Theor. Biol. 2023, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.B.; Kram, R.E.; Lin, K.; Myers, C.L.; Sobeck, A. dependent on POL θ -mediated alternative end joining. 2023, 42.

- Auerbach, A.D. Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat. Res. - Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2009, 668, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, O.M.; Paredes, A.C.; Suarez-Obando, F.; Rojas, A. An update on Fanconi anemia: Clinical, cytogenetic and molecular approaches (review). Biomed. Reports 2021, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmer, C.; Sánchez, S.; Ramos, S.; Molina, B.; Frias, S.; Carnevale, A. DEB Test for Fanconi Anemia Detection in Patients with Atypical Phenotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merfort, L.W.; Lisboa, M. de O.; Cavalli, L.R.; Bonfim, C.M.S. Cytogenetics in Fanconi Anemia: The Importance of Follow-Up and the Search for New Biomarkers of Genomic Instability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Fiesco-Roa, M.O.; Giri, N.; McReynolds, L.J.; Best, A.F.; Alter, B.P. Genotype-phenotype associations in Fanconi anemia: A literature review. Blood Rev. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Altintas, B.; Giri, N.; McReynolds, L.J.; Best, A.; Alter, B.P. Genotype-phenotype and outcome associations in patients with Fanconi anemia: the National Cancer Institute cohort. Haematologica 2023, 108, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Risitano, A.M.; Marotta, S.; Calzone, R.; Grimaldi, F.; Zatterale, A. Twenty years of the Italian Fanconi Anemia Registry: Where we stand and what remains to be learned. Haematologica 2016, 101, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kutler, D.I.; Singh, B.; Satagopan, J.; Batish, S.D.; Berwick, M.; Giampietro, P.F.; Hanenberg, H.; Auerbach, A.D. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR). Blood 2003, 101, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, B.P. Fanconi anemia and the development of leukemia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2014, 27, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, B.P.; Giri, N.; Savage, S.A.; Rosenberg, P.S. Cancer in the national cancer institute inherited bone marrow failure syndrome cohort after fifteen years of follow-up. Haematologica 2018, 103, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccaldi, R.; Parmar, K.; Mouly, E.; Delord, M.; Kim, J.M.; Regairaz, M.; Pla, M.; Vasquez, N.; Zhang, Q.S.; Pondarre, C.; et al. Bone marrow failure in fanconi anemia is triggered by an exacerbated p53/p21 DNA damage response that impairs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Zhang, K.; Färkkilä, A.; Filiatrault, J.; Yang, C.; Velázquez, M.; Furutani, E.; Goldman, D.C.; García de Teresa, B.; Garza-Mayén, G.; et al. MYC Promotes Bone Marrow Stem Cell Dysfunction in Fanconi Anemia. Cell Stem Cell 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijhuis, A.E.; Foijer, F. Characterizing chromosomal instability-driven cancer evolution and cell fitness at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.Y.; Horne, S.D.; Stevens, J.B.; Liu, G.; Ying, A.Y.; Vanderhyden, B.; Krawetz, S.A.; Gorelick, R.; Heng, H.H.Q. Single cell heterogeneity: Why unstable genomes are incompatible with average profiles. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoli, T.; Xu, A.W.; Mengwasser, K.E.; Sack, L.M.; Yoon, J.C.; Park, P.J.; Elledge, S.J. XCumulative haploinsufficiency and triplosensitivity drive aneuploidy patterns and shape the cancer genome. Cell 2013, 155, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Stevens, J.B.; Horne, S.D.; Abdallah, B.Y.; Ye, K.J.; Bremer, S.W.; Ye, C.J.; Chen, D.J.; Heng, H.H. Genome chaos: Survival strategy during crisis. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioc, A.M.; Wagner, J.E.; MacMillan, M.L.; DeFor, T.; Hirsch, B. Diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome among a cohort of 119 patients with fanconi anemia: Morphologic and cytogenetic characteristics. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 133, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebert, M.; Gachet, S.; Leblanc, T.; Rousseau, A.; Bluteau, O.; Kim, R.; Ben Abdelali, R.; Sicre de Fontbrune, F.; Maillard, L.; Fedronie, C.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis driven by chromosome 1q/MDM4 trisomy defines a canonical route toward leukemia in Fanconi anemia. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 153–170.e9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Butturini, A.; Gale, R.P.; Verlander, P.C.; Adler-Brecher, B.; Gillio, A.P.; Auerbach, A.D. Hematologic abnormalities in Fanconi anemia: An International Fanconi Anemia Registry study. Blood 1994, 84, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berger, R.; Jonveaux, P. Clonal chromosome abnormalities in Fanconi anemia. Hematol. Cell Ther. 1996, 38, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quentin, S.; Cuccuini, W.; Ceccaldi, R.; Nibourel, O.; Pondarre, C.; Pagès, M.P.; Vasquez, N.; D’Enghien, C.D.; Larghero, J.; De Latour, R.P.; et al. Myelodysplasia and leukemia of fanconi anemia are associated with a specific pattern of genomic abnormalities that includes cryptic RUNX1/AML1 lesions. Blood 2011, 117, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.A.; Harris, R.E.; Davies, S.M.; Kim, M.O.; Mueller, R.; Lampkin, B.; Mo, J.; Myers, K.; Smolarek, T.A. Numerical chromosomal changes and risk of development of myelodysplastic syndrome-acute myeloid leukemia in patients with Fanconi anemia. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2010, 203, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lisker, R.; Gutiérrez, A.C. de Cytogenetic studies in Fanconi’s anemia. Description of a case with bone marrow clonal evolution. Clin. Genet. 1974, 5, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, H.; Huber, S.; Kühl, J.S.; Gerlach, A.; Ebell, W.; Neitzel, H. Clonal chromosomal aberrations in bone marrow cells of Fanconi anemia patients: Gains of the chromosomal segment 3q26q29 as an adverse risk factor. Blood 2003, 101, 3872–3874. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, Y.L.; Göhring, G.; Bawadi, R.; Cöktü, S.; Reimer, C.; Hoffmann, B.; Sänger, B.; Käfer, S.; Thol, F.; Erlacher, M.; et al. A novel classification of hematologic conditions in patients with fanconi anemia. Haematologica 2021, 106, 3000–3003. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome Chaos, Information Creation, and Cancer Emergence: Searching for New Frameworks on the 50th Anniversary of the “War on Cancer. ” Genes (Basel). 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanconi Anemia Research Fund Fanconi anemia clinical care Guidelines; Sroka, I., Frohnmayer, L., Van Ravenhorst, S., Wirkkula, L., Eds.; 5th ed.; Fanconi Anemia Research Fund: Oregon, 2020.

- Sánchez, S.; Reyes, P.; Barrera, M.A.M.; Mar-Tínez, A.P.; Frias, S. Fanconi anemia, Part 3. Cytogenetic monitoring in the bone marrow of patients with Fanconi anemia. Acta Pediatr. Mex. 2024, 45, 343–368. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan-Jordan J, Simons A, S. M. ISCN 2020: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2020, 160, 503. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Khac, F.; Bidet, A.; Daudignon, A.; Lafage-Pochitaloff, M.; Ameye, G.; Bilhou-Nabéra, C.; Chapiro, E.; Collonge-Rame, M.A.; Cuccuini, W.; Douet-Guilbert, N.; et al. The complex karyotype in hematological malignancies: a comprehensive overview by the Francophone Group of Hematological Cytogenetics (GFCH). Leukemia 2022, 36, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engel, J.L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Espejo Valle-Inclán, J.; Hu, Q.; Woldehawariat, K.S.; Sanders, M.A.; Smogorzewska, A.; Chen, J.; et al. The Fanconi anemia pathway induces chromothripsis and ecDNA-driven cancer drug resistance. Cell 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome chaos: Creating new genomic information essential for cancer macroevolution. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.C.; Editors, H.H.H. Cancer Cytogenetics and Cytogenomics; ISBN 9781071639450.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

.

.

.

.