Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

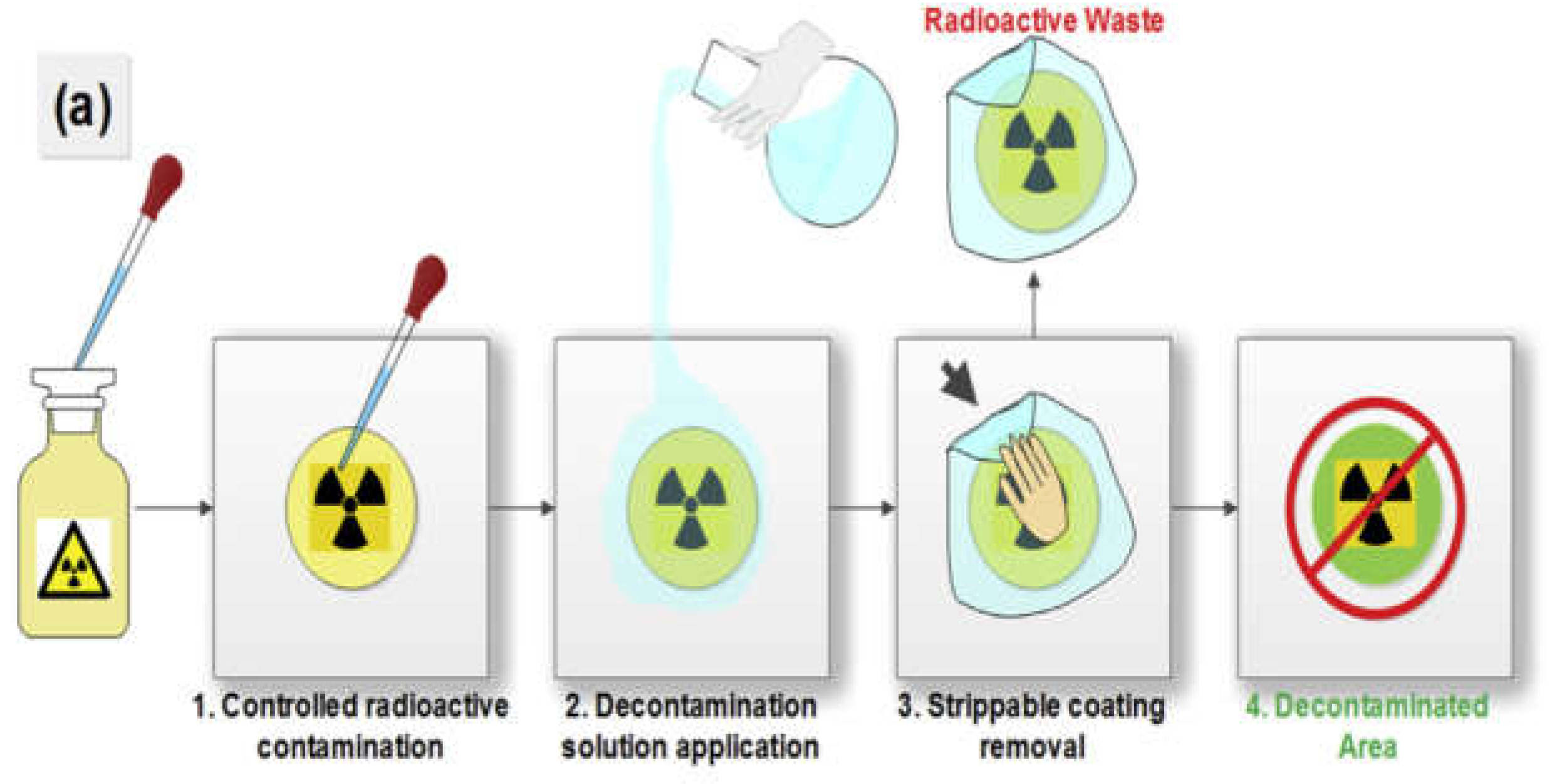

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Tools and Materials

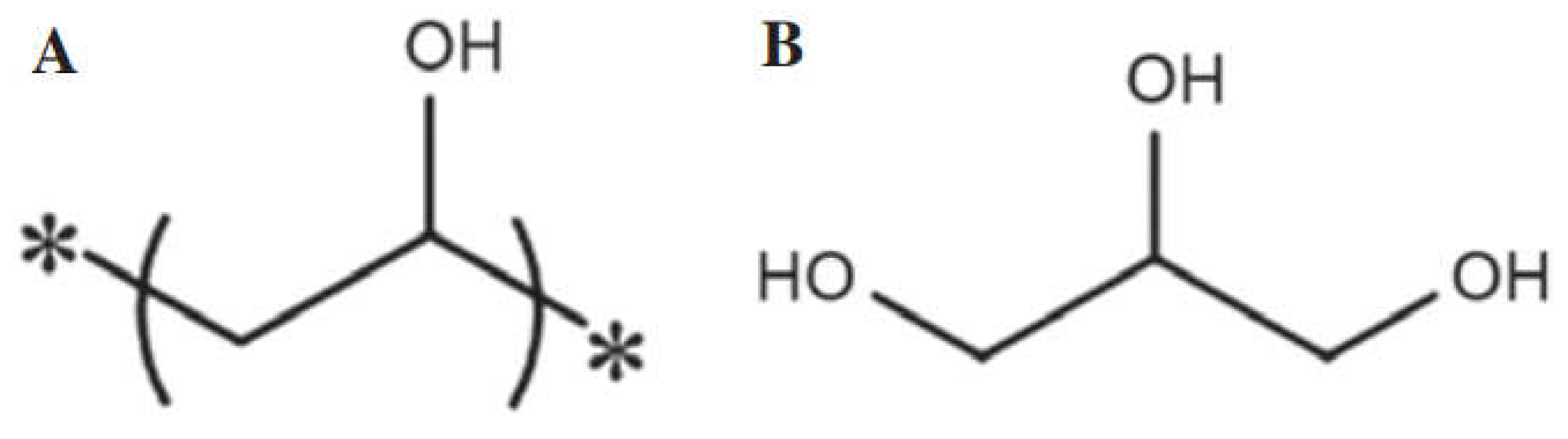

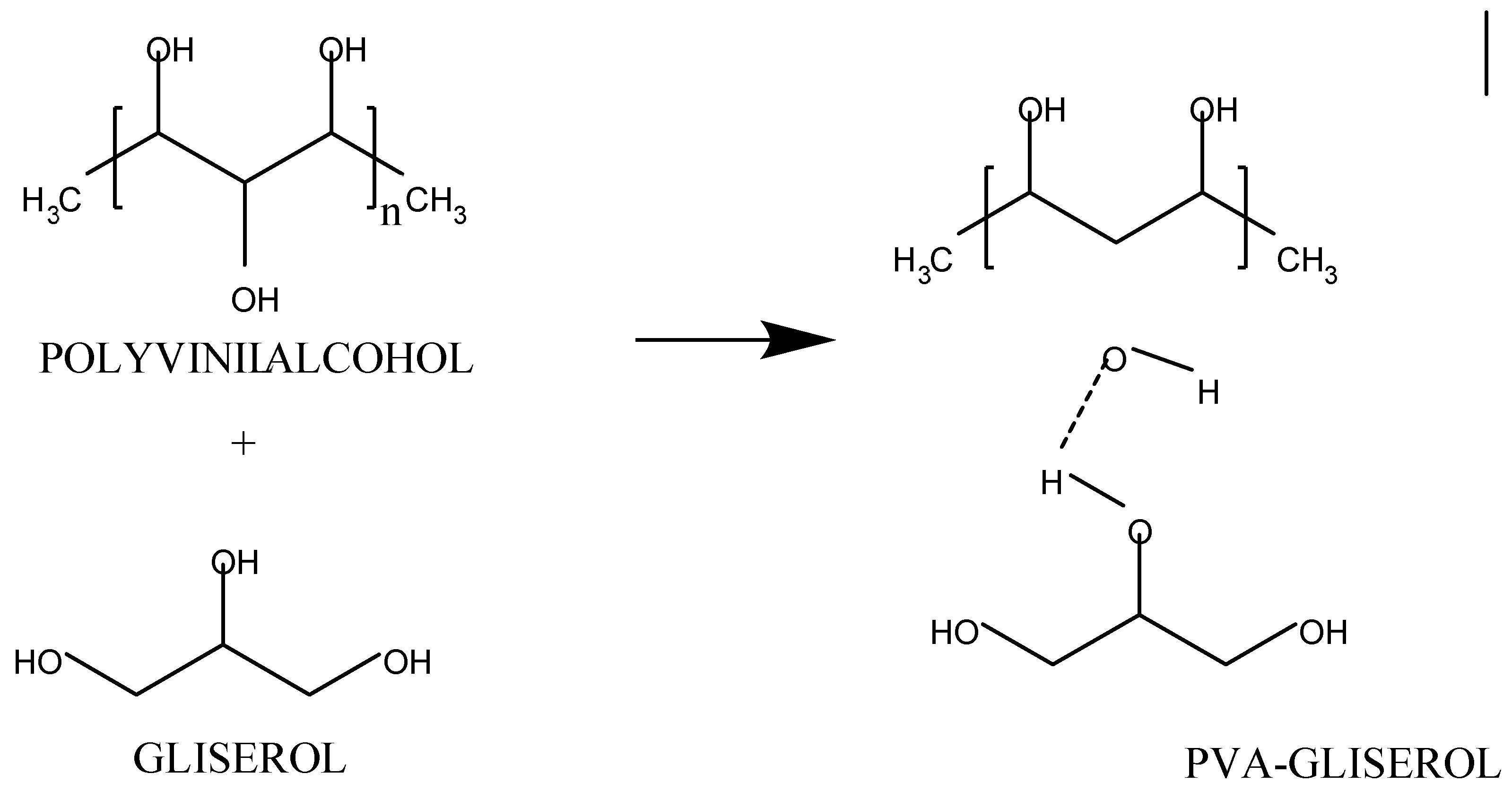

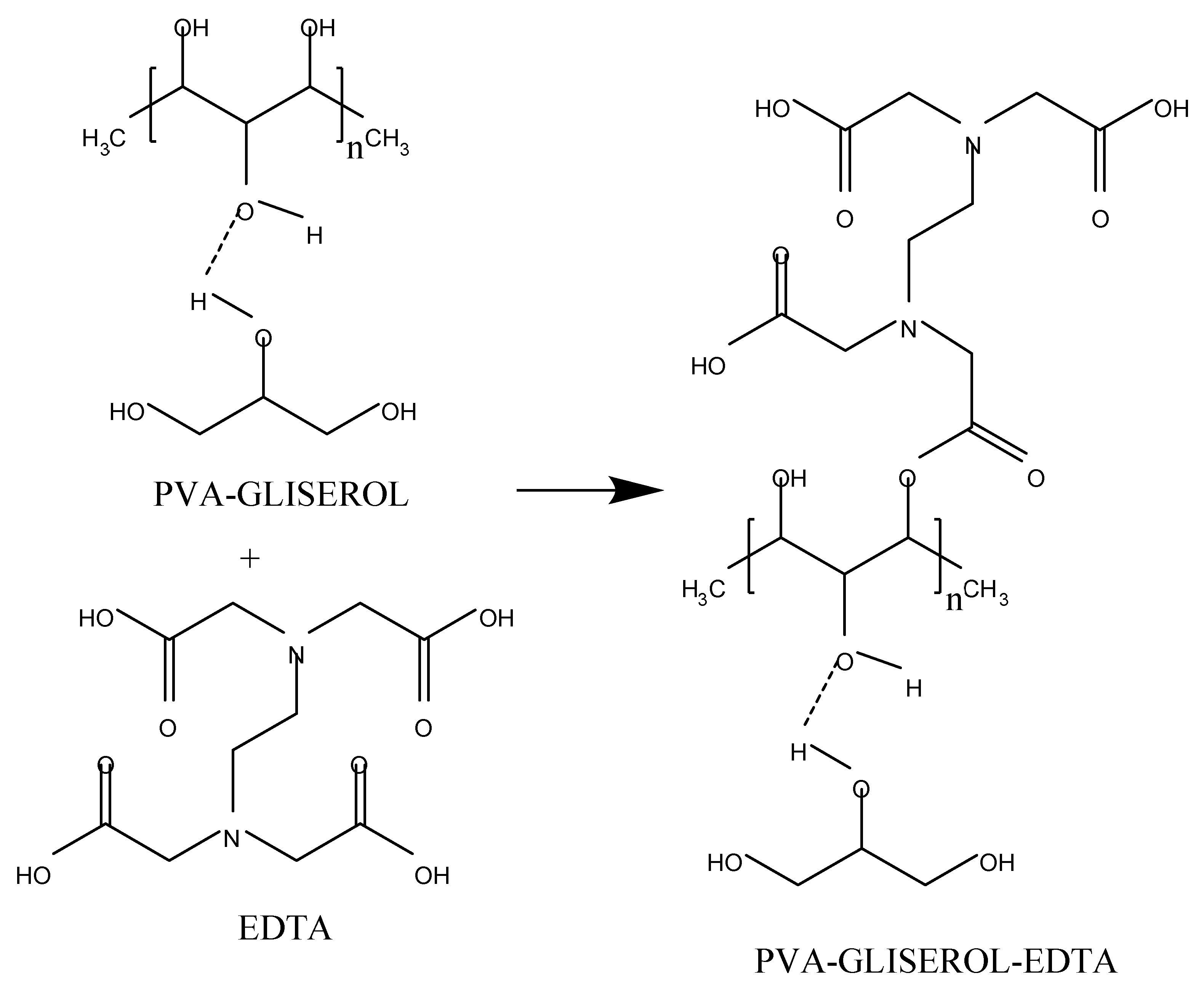

2.2. Making PVA Gel

2.3. Contaminated Material Creation

2.4. Decontamination Effectiveness Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Zhang H, Xi H, Lin X, Liang L, Li Z, Pan X, et al. Biodegradable antifreeze foam stabilized by lauryl alcohol for radioactive surface decontamination. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2022, 331, 3135–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume S, West G, Dobie G. A framework for capturing and representing the process to classify nuclear waste and informing where processes can be automated. Progress in Nuclear Energy. 2024, 170, 105133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Xiang Y, Su R, Hu B, Sun S, Liu Z. A method to obtain radioactivity of non-γ nuclides by 60Co based on Monte Carlo simulations. Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 2024.

- Hahm I, Kim D, Ryu H jin, Choi S. A multi-criteria decision-making process for selecting decontamination methods for radioactively contaminated metal components. Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 2023, 55, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttram C, Ervin P, Lunberg L, Marske S. Research Reactor Decommissioning Planning—It is Never Too Early to Start. Sydney 2003.

- Kuznetsov AY, Azovskov ME, Belousov S V, Vereshchagin II, Efremov AE, Khlebnikov S V. Dismantling and decontamination of large-sized radiation-contaminated equipment during Research Building B decommissioning at the Bochvar Institute site*. Nuclear Energy and Technology. 2019, 5, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Kim GH, Hwang D, Song JH, Im J, Lee J, Kang M, et al. Method for clearance of contaminated buildings in Korea research reactor 1 and 2. Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 2023, 55, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Global Status of Decommissioning of Nuclear Instalation [Internet]. Vienna; 2023 Mar. Available online: www.iaea.org/publications (accessed on day month year).

- Gurau D, Deju R. Radioactive decontamination technique used in decommissioning of nuclear facilities [Internet]. Article in Romanian Journal of Physics. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280920950 (accessed on day month year).

- Lee HY, Lee MH, Yang KT, An JY, Song JS. A Study on the Construction of Cutting Scenario for Kori Unit 1 Bio-shield considering ALARA. Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 2023, 55, 4181–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu S, He Y, Xie H, Ge Y, Lin Y, Yao Z, et al. A State-of-the-Art Review of Radioactive Decontamination Technologies: Facing the Upcoming Wave of Decommissioning and Dismantling of Nuclear Facilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross MT, Green TH, Adsley I. Characterisation of radioactive materials in redundant nuclear facilities: key issues for the decommissioning plan. In: Nuclear Decommissioning. Elsevier; 2012. p. 87–116.

- Badan Pengawas Tenaga Nuklir. Keputusan Kepala Badan Pengawas Tenaga Nuklir No. 500/IO/Ka-BAPETEN/29-V/2017 tentang Perpanjangan Izin Operasi Reaktor Triga 2000 Bandung. BAPETEN. Jakarta: BAPETEN; 2017.

- He Z, Li Y, Xiao Z, Jiang H, Zhou Y, Luo D. Synthesis and preparation of (acrylic copolymer) ternary system peelable sealing decontamination material. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Wang MJ. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions by Poly(vinyl alcohol) and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Composite Hydrogels Prepared by a Freeze-Thaw Method. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016, 4, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgormaa A, Lv C jiang, Li Y, Yang J, Yang J xing, Chen P, et al. Adsorption of Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solution by gel/PVA-modified super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Molecules. 2018, 23.

- Nagarkar R, Patel J. Acta Scientific Pharmaceutical Sciences (ISSN: 2581-5423) Polyvinyl Alcohol: A Comprehensive Study. 2019.

- Huang Y, Keller AA. EDTA functionalized magnetic nanoparticle sorbents for cadmium and lead contaminated water treatment. Water Res. 2015, 80, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Repo E, Meng Y, Wang X, Yin D, Sillanpää M. An EDTA-β-cyclodextrin material for the adsorption of rare earth elements and its application in preconcentration of rare earth elements in seawater. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 465, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Dai Z, Zhang W, Gao Q, Dai Y, Xia F, et al. EDTA-based adsorbents for the removal of metal ions in wastewater. Vol. 434, Coordination Chemistry Reviews. Elsevier B.V.; 2021.

- Zhao F, Repo E, Yin D, Meng Y, Jafari S, Sillanpää M. EDTA-Cross-Linked β-Cyclodextrin: An Environmentally Friendly Bifunctional Adsorbent for Simultaneous Adsorption of Metals and Cationic Dyes. Environ Sci Technol. 2015, 49, 10570–10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai Y, Che J, Yuan M, Shi X, Chen W, Yuan WE. Effect of glycerol on sustained insulin release from PVA hydrogels and its application in diabetes therapy. Exp Ther Med. 2016, 12, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulpea D, Rotariu T, Toader G, Pulpea GB, Neculae V, Teodorescu M. Decontamination of radioactive hazardous materials by using novel biodegradable strippable coatings and new generation complexing agents. Chemosphere. 2020, 258, 127227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan CM, Peppas NA. Structure and Morphology of Freeze/Thawed PVA Hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2000, 33, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin M, Hossin A, Haik Y. Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(vinyl alcohol) plasticized with glycerol. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011, 122, 3102–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis S, Varshney L. Studies on radiation synthesis of PVA/EDTA hydrogels. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2005, 74, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

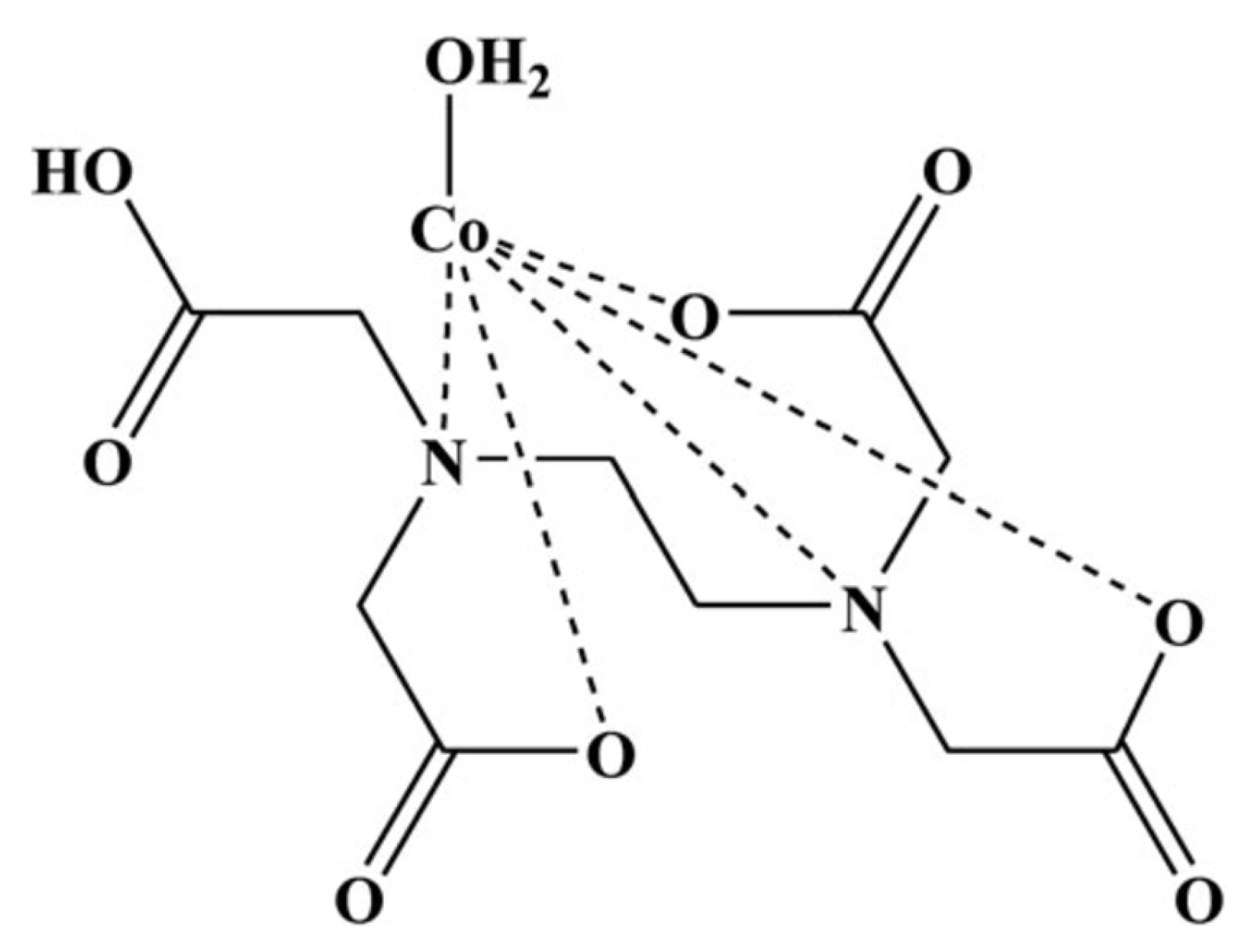

- Mudsainiyan RK, Chawla SK. Synthesis, Characterizations, Crystal Structure Determination of μ 6 Coordinated Complex of Co (III) with EDTA and Its Thermal Properties. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 2015, 606, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas BE, Radanović DJ. Coordination chemistry of hexadentate EDTA-type ligands with M(III) ions. Coord Chem Rev. 1993, 128, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau D, Deju R. The use of chemical gel for decontamination during decommissioning of nuclear facilities. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2015, 106, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D. Rethwisch DG. Materials science and engineering: an introduction. John Wiley; 2009. 721 p.

| Solution | Synthesis Process | Gel Formation | Dry Gel | Gel Peel | Final Observation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution A (5% w/v PVA) | Yes | No | No | No | The gel does not form |

| Solution B (10% w/v PVA) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Gel forms but is wet and cannot be peeled off |

| Solution C (15% w/v PVA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | It forms a gel, dries perfectly, and can be peeled off. |

| Solution D (20% w/v PVA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | It forms a gel, dries perfectly, and can be peeled off. |

| No. | Solution Code | % PVA | % EDTA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Solution 1 | 15% w/v | 0% w/v |

| 2 | Solution 2 | 15% w/v | 1% w/v |

| 3 | Solution 3 | 15% w/v | 2% w/v |

| 4 | Solution 4 | 15% w/v | 3% w/v |

| 5 | Solution 5 | 15% w/v | 5% w/v |

| No. | Contamination Media | Average Decontamination Effectiveness (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA Gel 15% w/v - EDTA 0% w/v | PVA Gel 15% w/v - EDTA 1% w/v | PVA Gel 15% w/v - EDTA 2% w/v | PVA Gel 15% w/v - EDTA 3% w/v | PVA Gel 15% w/v - EDTA 5% w/v | ||

| 1. | Ceramics | 82 | 88 | 95 | 78 | 53 |

| 2. | Glass | 95 | 93 | 98 | 80 | 89 |

| 3. | Metal Plate | 67 | 94 | 95 | 54 | 75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).