Clinical trial registration: ISRCTN 32761538

1. Introduction

The widespread use of herbs and medicinal plants in traditional medicine has garnered increasing recognition as a valuable resource for increasing wellness and reducing the onset of disease.

Camellia sinensis (tea) one of the most popular beverages worldwide , is desired not only for its taste and aroma but also for its wellness promoting properties, cultural significance, and diverse social appeal [

1]. Many studies have demonstrated that tea, as well as herbal tea blends, shows various health functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immuno-regulatory, anticancer, cardiovascular-protective, anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, and hepato-protective effects [

2].

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are diseases involving the circulatory system (heart, arteries, and veins), and includes heart conditions, hypertension, otherwise known as persistently high blood pressure, and narrowing of arteries as a result of deposition of fat, cholesterol, and other substances along the arterial walls, thus limiting the supply of blood to various part of the body and organs [

3].

CVDs remain a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the Western world. The ongoing search for factors that can reduce the prevalence of these conditions remains a prominent focus in research. Several epidemiologic and clinical studies [

4] have shown that high levels of total cholesterol, triacylglycerols, LDL cholesterol, and low levels of HDL cholesterol, are risk factors for CVD, among several others. Faecal microbial community changes are associated with numerous disease states, including CVD [

5]

Data suggest that green tea drinking has beneficial effects, which protects against CVD by improving blood lipid profiles [

4,

6,

7], amongst other things. Several studies have investigated the modulation effect of green tea on the gut microbiota in humans [

8,

9]. These findings appear to support the hypothesis that tea ingestion could favourably regulate the profile of the gut microbiome and help to offset dysbiosis triggered by obesity or high-fat diets. Further well-designed human trials are now required to build on provisional findings.

Tea infusions are often enriched with herbs and botanicals, usually selected and blended for a specific health effect and taste profile. Preliminary data from

Cassia species such as Senna (

Cassia acutifolia and Cassia angustifolia) indicate the potential to improve blood lipid profiles [

10] in rodent models and in vitro, however,

Cassia species are also known for their laxative effect [

11]. They contain anthraquinones such as sennosides which may be responsible for the purgative effect (Demirezer et al.

, 2011). Rhubarb also contains anthraquinones such as sennosides and possesses a milder laxative effect (Duval et al.

, 2016; Takayama et al.

, 2012). Rhubarb roots can be considered as waste products of rhubarb stem cultivation despite containing similar amounts of active ingredients as the stalk.

Although several trials have examined the effect of green tea on lipid profiles and gut microbiota in human cohorts, data on green tea with senna or rhubarb root remains limited. Therefore, the present clinical trial was carried out to investigate the effect of green tea containing senna or rhubarb root, with a green tea comparison, on lipid profiles and gut microbiota, as well as diet and BMI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

This was a double-blind, randomised, active controlled parallel human clinical trial (registered in the ISRCTNregistery (

https://www.isrctn.com/) under registry number ISRCTN32761538, approved by the Research Ethics Panel at Aberystwyth University. Subjects were recruited by the Well-being and Health Assessment Research Unit (WARU) at Aberystwyth University and the study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, where participants gave written informed consent. The pre-screening for the first volunteers started in May 2022 and the study was completed in May 2023. The trial was conducted at Canolfan Plas Y Sarn

, Trimsaran and the participants followed the intervention trial at home and came to the centre before and after the trial for measurements, blood collections, and questionaries.

Participants were recruited according to eligibility criteria. Inclusion Criteria included: consenting adults >18 years of age; commit to fasting capillary blood collection; commit to stool sampling collection; able to refrain from taking any over-the-counter medication or herbal supplements during the diet monitoring and experimental periods; able to prepare and consume the tea during the experimental days, after the last meal/snack of the day and not to consume anything afterward; fill in diet questionnaires and stool ranking; able to inform the researcher if any antibiotics or heavy alcohol is consumed over the intervention period. Exclusion Criteria included: serious health conditions that require daily long-term medications (including immunosuppressants); a history or current diabetes, lung issues, gut inflammation (Crohn’s, IBD), digestive disorders; diagnosed with a serious health condition within the last 12 months; pregnant or lactating; play sports at a high level (more than 7h/week or 1h/day); smoker; consume high dose of alcohol > 21 unit per week for men and > 14 units per week for women; food allergy /food intolerance/ eating disorder or are on a specially prescribed diet. If eligible, participants were allocated to three groups using computer-generated random number tables: senna herbal tea, rhubarb root herbal tea, and green tea. The study was double-blinded, so researchers and intervention participants were unaware of the tea allocation until intervention and analysis completion.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

Based on the information obtained from the research for LDL cholesterol (power of 80%, and a confidence interval of 95%) (Suliburska et al., 2012), the sample size was estimated to be 15-20 participants per group, accounting for predicted 10% drop-outs. The effect size was calculated post trial.

2.3. Study Design: Dose, and Type of Herbal Teas

Infusions were taken after the last meal/snack of the day (post 18:00 hours) daily, for 21 days and no food was consumed afterward.

Senna herbal bags (total weight 2.5g) contained the following ingredients: green tea 0.75g from Dartmoor Estate Tea, UK, senna leaves (

Cassia angustifolia Vahl) 1.2g, alongside cassia seeds, lotus leaf, fiveleaf gynostemma, honeysuckle flower and hawthorn fruit, all at <0.33g each. Rhubarb root herbal tea bags contained the same as the senna tea bags however 1.2g dried Stockbridge arrow root (

Rheum rhabarbarum) replaced the senna. Active control green tea bags contained 0.75g of green tea only. Tea/herbal tea bags were infused in 190ml of hot water (80-100◦C) by the participants at home and stirred clockwise 10 consecutive times to allow for optimal infusion and then allowed to brew for 5 minutes, before removal of the teabag and consumption of the infusion (infusions were standardized to 16.8 ± 2.5 ug/ml of green tea catechins,

Table 1 and Appendix 1).

2.4. Anthropometric Measures

Body weight (using SECA 799 Electronic Column Scales to the nearest 0.1 kg) and height was measured (using a Holtain Stadiometer to the nearest cm) to allow the BMI to be calculated and compared to ranges set out by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2006). Waist circumference (midway between the lower rib and the iliac crest on the midaxillary line) and hip (level of the widest circumference over the great trochanters) were taken to the nearest 0.1cm, using an ergonomic circumference measuring tape over bare skin, whenever possible. Triplicate measurements were made, and the mean was calculated, allowing the waist-to-hip ratio to be calculated and compared to published ranges (Hollmann et al., 1997, Park et al., 2015). All measurements were done in the morning, by the researcher after the participants had been fasting for at least 8 h.

2.5. Food Recall and Stool Consistency

Diet was assessed using Prime Diet Quality Score (PDQS) (Brennan et al., 2022), amended to account for vegetarian and vegan choices which assessed an individual’s diet and eating habits. Bristol stool scale (Chumpitazi et al., 2016) provided data concerning the consistency of the stool. Both questionaries were completed on the first and last day of the trial and were not researcher-led. All participants were requested to maintain their habitual physical activity. To evaluate compliance, participants were requested to note any missed teabags and to bring back the remaining teabags.

2.6. Collection, Preparation of Blood Samples and Analysis

Fasting bloods were collected by fingers being pricked using lancets and collected into BD Microtainer™ Tubes (600 μl) with Microgard™ Closure containing anticoagulant (Lithium heparin). Plasma was extracted by inversion and then centrifugation at 4000 xg for 20 minutes at 4o C. Plasma samples were analyzed using the Afinion AS100 (Abbott, 2014) lipid panel (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and non-HDL cholesterol).

Since participants had their lipid profiles measured before and after the intervention, these data were treated as paired measurements, and the dependency on participant identity was taken into account for statistical analysis. Age and BMI were included as covariates in the analysis to adjust for any potential effects related to these variables. Gender was not included as a covariate due to the highly unbalanced distribution of participants. As there was no prior information on the direction of the effect of the infusions (positive, negative, or neutral), we conducted tests for differences in lipid concentrations before and after the intervention.

To minimize Type I error inflation from multiple comparisons, we performed a repeated measures ANOVA using the base R stats package (R Core Team, 2013). The model included participant ID as a random effect, and age and BMI as continuous covariates. Fixed effects included time (before and after the intervention), treatment group (Green tea, rhubarb root, and senna infusion), and their interaction.

We analysed the six blood lipid measurements separately: total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, non-HDL cholesterol and HDL/LDL ratio.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted using the R package emmeans (Lenth, 2024) to calculate marginal means and estimate the differences in lipid concentrations resulting from the consumption of any experimental tea, regardless of type. We also tested for interaction effects to evaluate differences in lipid concentrations before and after the intervention for each infusion group.

2.7. Collection, Preparation of Stool Samples and Analysis

Faecal samples were collected and preserved in OMNIgene.GUT OM-200 (DNAgenotek) kits. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit. For library preparation, the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using specific primers as previously described (Kozich et al., 2013). Libraries were quality-checked and normalised using the Qubit HS DNA quantification kit before sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq platform at the Swansea University Medical School Sequencing Facility. Sequence processing was conducted with Mothur (version 1.44.1), clustering reads into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 3% dissimilarity threshold to analyse community structure. Taxonomic classification utilised the SILVA release 132 reference database, and sequences identified as chloroplast, eukaryotic, mitochondrial, or archaeal were filtered out to refine the dataset. Alpha diversity metrics—including observed OTUs (Sobs), Shannon evenness, and the inverse Simpson diversity index—were calculated in Mothur. Statistical analyses and graphical representations were completed in RStudio using the tidyverse (version 1.3.2), phyloseq (version 1.40.0), and vegan (version 2.6.2) packages. Alpha diversity comparisons were conducted with pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with Benjamini-Hochberg adjustments for multiple comparisons. To investigate correlations between bacterial genera and lipid levels (Cholesterol, LDL-Cholesterol, HDL-Cholesterol, triglycerides, non-HDL Cholesterol), genus-level linear regression analyses were conducted. Genera relative abundances were calculated, and their associations with lipid measurements were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation, adjusting p-values with the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Genera with significant correlations (adjusted p < 0.05) were further explored through linear regression to characterise these associations. Community-level (beta diversity) analyses used the Bray-Curtis distance metric. Differences in microbial composition between groups were assessed using adonis2 permutational multivariate analysis of variance with 100,000 permutations, accounting for confounding factors, including age and BMI, and interactions between sampling points (pre- and post-intervention). This enabled a robust assessment of community composition differences across intervention groups and time points. Data is available in NCBI BioProject as fastq files (PRJNA1182543).

3. Results and Discussion

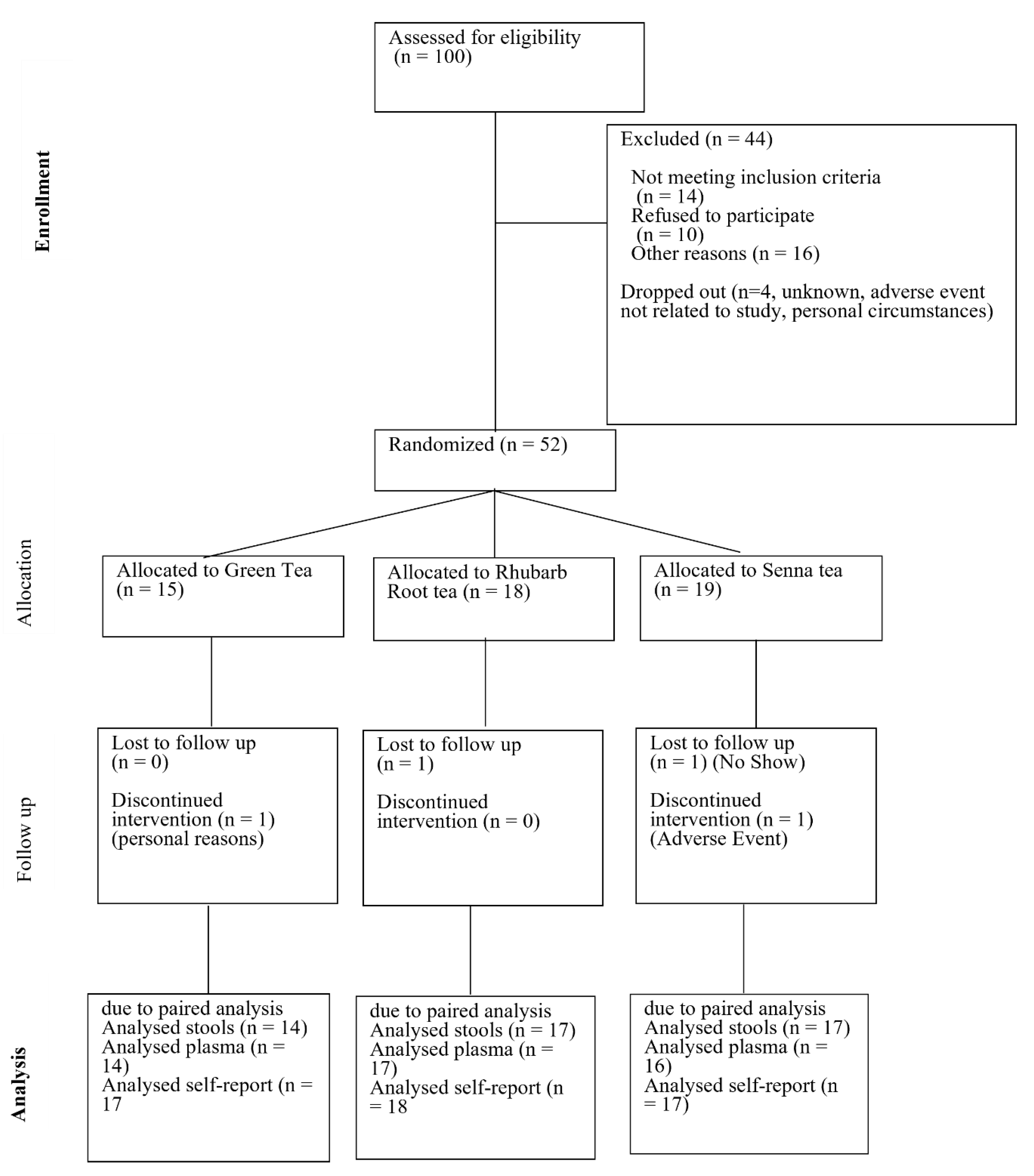

A total of 56 participants who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Four of the participants dropped out; therefore, 52 participants completed a 21-day period (

Figure 1 and

Table 2, 17 in the green tea group, 15, Rhubarb root 18 and senna group 18). The mean age and BMI of the participants were 52.86 ± 12.53 (years) and 29.90 ± 5.83 (kg/m

2), respectively. Based on the residual green tea in the packed sachets, participants had high adherence and compliance rate was over 98%, and no serious adverse events were associated with drinking the herbal tea. One participant reported an adverse event five days after the first intervention day, however there was no evidence of any reasonable causal relationship to the trial intervention. The participant feedback was recorded, and they chose to withdraw from the study, reporting full health two days later. Eight individuals reported that they had an increase in bowel movements, however none of these expressed this to be problematic, or a reason to stop participating.

The comparison between the diet score before and after the intervention showed no significant change between or within any of the trial arms (data not shown). A similar outcome was shown with the BMI and Waist/Hips ratio, no changes were observed (data not shown).

Because lipid profiles were measured before and after the intervention trial, the data are treated as repeated measurements, requiring consideration of sample dependence based on participant identity in the statistical analysis. Therefore, only the 47 participants who provided blood samples both before and after the trial were included in the analysis.

The analysis revealed that time had a highly significant effect on cholesterol levels (p = 0.0016), indicating a meaningful change in cholesterol over the course of the study. However, the interaction between treatment and time was not significant (p = 0.5891), suggesting that the effect of the treatments did not significantly differ over time. For individual group baseline to post-intervention comparisons, green tea showed a marginally significant change (p = 0.0587), suggesting a potential trend, but the evidence was not strong enough to draw firm conclusions. Rhubarb root tea demonstrated a significant change (p = 0.0102), indicating a meaningful reduction in cholesterol, while senna tea showed no significant change (p = 0.2474) from baseline to post-intervention.

Similarly, time had a highly significant effect on LDL-cholesterol concentrations (p = 0.0000), suggesting a meaningful change over time. However, the treatment x time interaction was not significant (p = 0.2910), indicating that the treatments did not have differing effects over time. For individual group baseline to post-intervention comparisons, green tea had a significant reduction in LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.0011), and rhubarb root tea showed a highly significant reduction (p = 0.0006). In contrast, senna tea showed no significant change in LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.0986). Age had a marginally significant effect on LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.0564), but this result was borderline significant, while BMI had no significant effect on LDL (p = 0.1903).

For non-HDL cholesterol, the results followed a similar pattern as LDL-cholesterol. Green tea and rhubarb root tea both showed significant reductions in non-HDL levels (p = 0.0219 and p = 0.0112, respectively). In contrast, senna tea showed no significant change in non-HDL cholesterol (p = 0.2042).

Finally, the analysis revealed that none of the treatments had a significant effect on triglyceride levels or HDL-cholesterol. For triglycerides, the p-values for green tea (p = 0.1920), rhubarb root tea (p = 0.2503), and senna tea (p = 0.7126) were all non-significant. Similarly, none of the treatments significantly affected HDL-cholesterol (green tea p = 0.7903, rhubarb root tea p = 0.6207, and senna tea p = 0.8958).

The rhubarb group showed a large effect in LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and the Chol/HDL ratio, all greater than -0.8. Additionally, the rhubarb group had sufficient statistical power (0.91517), while the green tea groups fell below the threshold for adequate power.

Table 3 and full data in Appendix 3 presents the mean differences in chemical concentrations between baseline and post-intervention for each group-chemical combination, along with the standard deviation of these differences.

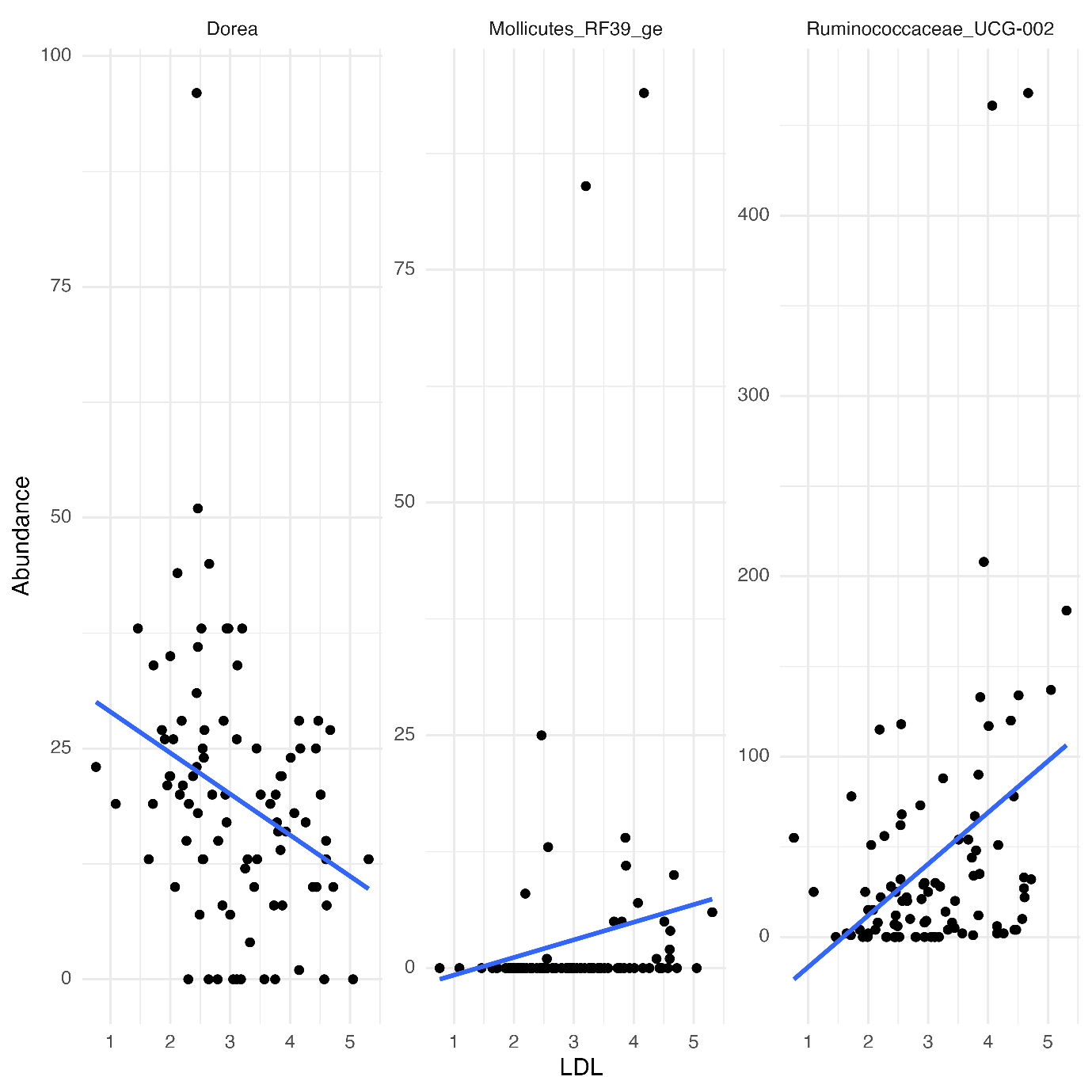

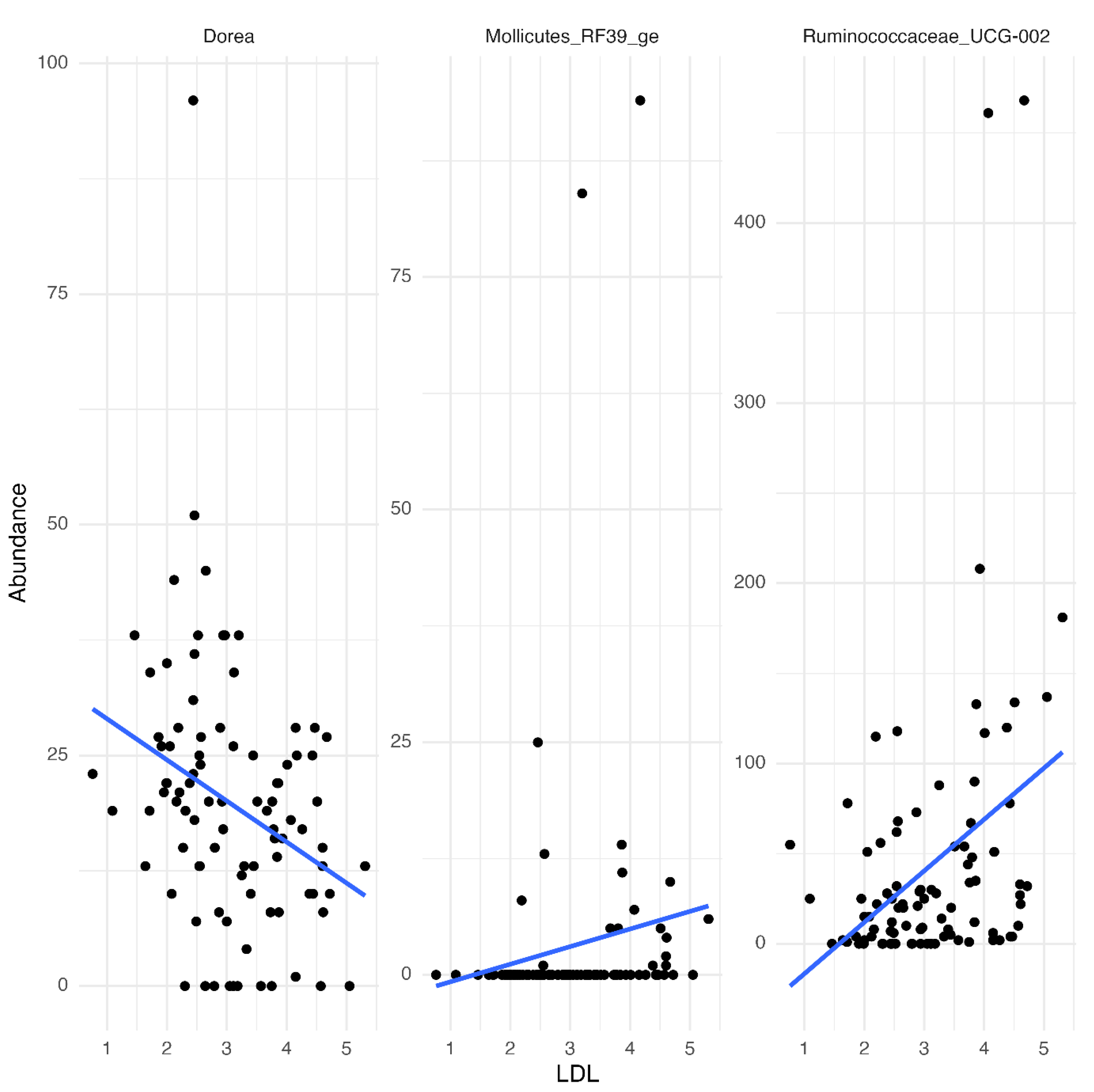

We assessed correlations between specific genera abundances and lipid profile components, focusing on LDL-cholesterol concentrations. Using linear modelling, we identified significant correlations (p.adjust < 0.05) between LDL-cholesterol levels and the abundance of several bacterial genera. Notably,

Dorea spp abundance was inversely associated with LDL-cholesterol, suggesting a potential protective effect or inverse relationship, as higher

Dorea abundance correlated with lower LDL-cholesterol concentrations. In contrast, positive correlations were observed between LDL-cholesterol concentrations and both

Mollicutes RF39ge and

Ruminococcaceae UCG-002, where higher abundances in these genera were associated with elevated LDL-cholesterol (

Figure 2).

Despite these genus-level correlations, community-level analyses using adonis2, accounting for potential confounding factors such as age or BMI and interactions between sample points, revealed no significant differences in overall microbial composition between pre- and post-intervention samples within any of the three tea groups, even with 100,000 permutations. This suggests that, while specific bacterial genera correlate with LDL-cholesterol changes, the broader microbial community structure remains stable across the intervention period, unaffected by these other confounding factors. Notably, no detrimental shifts in microbial composition were detected over the intervention period, suggesting that gut balance was preserved without any adverse impacts in this healthy human cohort.

4. Conclusions

In general, the study found that drinking a daily cup of rhubarb root herbal or green tea infusion for 21 days had positive effects on lipid profiles—especially on total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and non-HDL-cholesterol. No detrimental shifts occurred in microbial composition over the intervention period, suggesting that gut balance was preserved without any adverse impacts in this healthy human cohort. More studies are needed to fully elucidate these findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AJL and AWW.; methodology AJL and AWW.; software, TW and OMG ; formal analysis and investigation, AJL, AW, AWW. PMM, LL, MB and MDH.; writing—original draft preparation, AJL, MDH, GA and BVR; supervision, AJL and MB; funding acquisition, AJL All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Funded by Welsh Government Covid Recovery Challenge Funding, alongside Innovate UK Better Food for all (10068218), and BBSRC OIRC RIPEN Innovation Hub and Biofortification Hub.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Group of Aberystwyth University on the 11th of October 2022 by , reference number: 24336. The trial is registered in the ISRCTNregistery (

https://www.isrctn.com/) under registry number ISRCTN32761538.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available on request and in Appendix 2. Raw FASTQ files generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA and are accessible through the BioProject database under accession number PRJNA1182543. Any other raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aberystwyth University Dissertation students Naomi Edwards and Laura Taraszkowska for their assistance in conducting the human trial and for amending and testing the PDQS. We would like to also thank Tetrim Teas (Mari Arthur and Steffan Mcallister). Dartmoor Estate Tea (Jo Harper and Kathryn Bennet) and the wonderful trial participants in Trimsaran, Wales, UK

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

CVD, Cardiovascular disease; LDL, Low- Density Lipoprotein; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein; non-HDL, non-High-Density Lipoprotein

References

- Pan, S.-Y. , et al, Tea and tea drinking: China’s outstanding contributions to the mankind. Chinese Medicine 2022, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.-Y. , et al, Health Functions and Related Molecular Mechanisms of Tea Components: An Update Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adefegha, S.A., G. Oboh, and O.O. Oluokun, Chapter 11 - Food bioactives: the food image behind the curtain of health promotion and prevention against several degenerative diseases, in Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, R. Atta ur, Editor. 2022, Elsevier. 391-421.

- Coimbra, S. , et al, Green tea consumption improves plasma lipid profiles in adults. Nutrition Research 2006, 26, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M. L. Weeks, and S.L. Hazen, Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research 2020, 127, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R. , et al, Effect of green tea consumption on blood lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr J 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F. , et al, Effects of green tea on lipid metabolism in overweight or obese people: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2018, 62, 1601122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-C. -Y.Li, and L. Shen, Modulation effect of tea consumption on gut microbiota. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 104, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, T. and E. Derbyshire, Tea Compounds and the Gut Microbiome: Findings from Trials and Mechanistic Studies. Nutrients 2019, 11.

- Xu, L., et al., Exploring the therapeutic potential of Cassia species on metabolic syndrome: A comprehensive review. South African Journal of Botany 2024, 173, 112–136. [CrossRef]

- Thaker, K. , et al, Senna (Cassia angustifolia Vahl.): A comprehensive review of ethnopharmacology and phytochemistry. Pharmacological Research - Natural Products 2023, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).