1. Introduction

The study of geometric means of matrices has become increasingly important in various fields, including numerical linear algebra, differential equations, and signal processing. Positive definite matrices arise naturally in many applications, such as in the discretization of differential equations via methods like finite differences or finite elements. These methods produce matrix-sequences whose sizes increase as the mesh size becomes finer. An essential concept related to matrix-sequences is the asymptotic eigenvalue distribution in the Weyl sense and this has been a classical study; see e.g. [

17,

23,

40]. Since the publication of the seminal papers by Tyrtyshnikov in 1996 [

41] and Tilli in 1998 [

38,

39], there has been growing interest in this area, which eventually contributed to the development of the theory of Generalized Locally Toeplitz (GLT) sequences [

35,

36]. The increasing attention to this topic is not purely theoretical, as the asymptotic eigenvalue and singular value distributions have significant practical applications, particularly in the analysis of large-scale matrix computations especially in the context of the numerical approximations of systems of (fractional) partial differential equations ((F)PDEs); see e.g. the books and review papers [

7,

8,

20,

21,

22] and references therein. In fact, it is worth noticing that virtually any meaningful approximation technique of a (F)PDE leads to a GLT matrix-sequence, including finite differences, finite elements of any order, discontinuous Galerkin techniques, finite volumes, isogeometric analysis etc. More in detail, if we fix

positive integer numbers, then the set of

d-level

r-block GLT matrix-sequences forms a maximal *-algebra of matrix-sequences, isometrically equivalent to

d-variate

matrix-valued mesurable functions defined on

. Furthermore, a

d-level

r-block GLT sequence

is uniquely associated with a

matrix-valued Lebesgue-measurable function

, known as the GLT symbol, which is defined over the domain

. Notice that the set

can be replaced by any bounded Peano-Jordan measurable subset of

as occurring with the notion of reduced GLT *-algebras, see [

35][pp. 398-399, formula (59)] for the first occurrence with applications of approximated PDEs on general non-Cartesian domains in

d dimensions, [

36][Section 3.1.4] for the first formal proposal, and [

5] for an exhaustive treatment, containing both the *-algebra theoretical results and a number of applications. This symbol provides a powerful tool for analyzing the singular value and eigenvalue distributions when the matrices

are Hermitian and part of a matrix-sequence of increasing size. The notation

indicates that

is a GLT sequence with symbol

. Notably, the symbol of a GLT sequence is unique in the sense that if

and

, then

almost everywhere in

[

7,

8,

20,

21]. Furthermore, by the *-algebra structure,

and

implies that

, i.e., the matrix-sequence

is zero-distributed and the latter is very important for building explicit matrix-sequences approximating a GLT matrix-sequence and whose inversion is computationally cheap, in the context of preconditioning of large linear systems.

In certain physical applications, it is often necessary to represent the results of multiple experiments through a single average matrix

G, where the data is represented by a set of positive definite matrices

. The arithmetic mean

is not appropriate in these cases because it does not fulfill the requirement that the inverse of the mean should coincide with the average of the inverses

. This property, which is crucial in certain physical models is satisfied by the geometric mean. For positive real numbers

, the geometric mean is defined as

a concept that is extended to the case of matrices [

10,

26] in a nontrivial way, where the difficulty is of course the lack of commutativity. A well-known definition that satisfies desirable properties such as congruence invariance, permutation invariance, and consistency with the scalar geometric mean was proposed by ALM [

1]. They defined the geometric mean of two Hermitian positive definite (HPD) matrices as

We recall the definition of functions applied to diagonalizable matrices, which we frequently utilize throughout our work. Suppose

is diagonalizable, meaning

, where

is a diagonal matrix, and

f is a given function. In this case,

is defined as

, with

being a diagonal matrix whose diagonal entries are

, for

. In the case where

f is a multi-valued function, the same branch of

f must be chosen for any repeated eigenvalue.

If

then the ALM-mean is obtained through a recursive iteration process where at each step the geometric means of

k matrices are computed by reducing them to

matrices. However, a significant limitation of this method is its linear convergence leading to a high computational cost due to the large number of iterations required at each recursive step. As a result, the computation of the ALM-mean using this approach becomes quite expensive. However, despite the elegance of the ALM geometric mean for two matrices, it becomes computationally infeasible to extend this formula to more than two matrices [

14].

To overcome these limitations, the Karcher mean [

13], was introduced as a generalization of the geometric mean for more than two matrices. The Karcher mean of HPD matrices

is defined as the unique positive definite solution to the matrix equation:

as established by Moakher [

26, Proposition 3.4]. This equation can be equivalently expressed in other forms, such as

by utilizing the formula

, which holds for any invertible matrix

M and any matrix

K with real positive eigenvalues. This formulation arises from Riemannian geometry, where the space of positive definite matrices forms a Riemannian manifold with non-positive curvature. The Karcher mean represents the center of mass (or barycenter) on this manifold [

10]. In this manifold, the distance between two positive definite matrices

A and

B is defined as

where

denotes the Frobenius norm.

Several numerical methods have been proposed for solving the Karcher mean equation. Initially, fixed-point iteration methods were used, but these methods suffered from slow convergence, especially in cases where the matrices involved were poorly conditioned [

26]. Later, methods based on gradient descent in the Riemannian manifold were introduced. A common iteration scheme for approximating the Karcher mean is

where

is the approximation at the

v-th step, and the exponential and logarithmic functions are matrix operations. Although this method improves convergence, it can exhibit slow linear convergence in certain cases. The iteration with

or

and

, as considered in [

25,

26], can fail to converge for some matrices

. Furthermore, similar iterations have been proposed in [

3,

28], but without specific recommendations on choosing the initial value or step length. While an optimal

could theoretically be determined using a line search strategy, this approach is often computationally expensive. Heuristic strategies for selecting the step size, as discussed in [

18], may result in slow convergence in many cases.

To further enhance the convergence rate, the Richardson iteration method is employed. Indeed, the considered method improves the convergence by using a parameter

, which controls the step size in each iteration [

13]. More precisely, given

, the Richardson iteration is given by

Any solution of Eq. (

3) is a fixed point of the map

T in (

5). The iterative formula can also be rewritten as

provided that all the iterates

remain positive definite. Equation (

6) further demonstrates that if

is Hermitian, then

is also a Hermitian matrix.

The parameter plays a crucial role in controlling the step size of each iteration and choosing an optimal value of can significantly influence the convergence behavior of the iteration. If is small enough, the iteration is guaranteed to produce positive definite matrices and converge towards the solution. In particular, when the matrices commute, setting ensures at least quadratic convergence. More generally, the optimal value of can be determined based on the condition numbers of matrices , where G is the desired solution. The closer the eigenvalues of are to 1, the faster the convergence is. This analysis guarantees that if the initial guess is close enough to the solution and is positive definite, the sequence generated by the iteration remains well-defined and converges to the desired solution. However, if the initial iterate is not positive definite, adjusting the value of or modifying the iteration scheme may be necessary to ensure that all iterates remain positive.

Numerical experiments show that selecting appropriate initial guesses, such as the arithmetic mean

or the identity matrix

, can significantly affect the convergence rate. In particular, the cheap mean introduced in [

12] provides a practical initial approximation that leads to faster convergence in many cases.

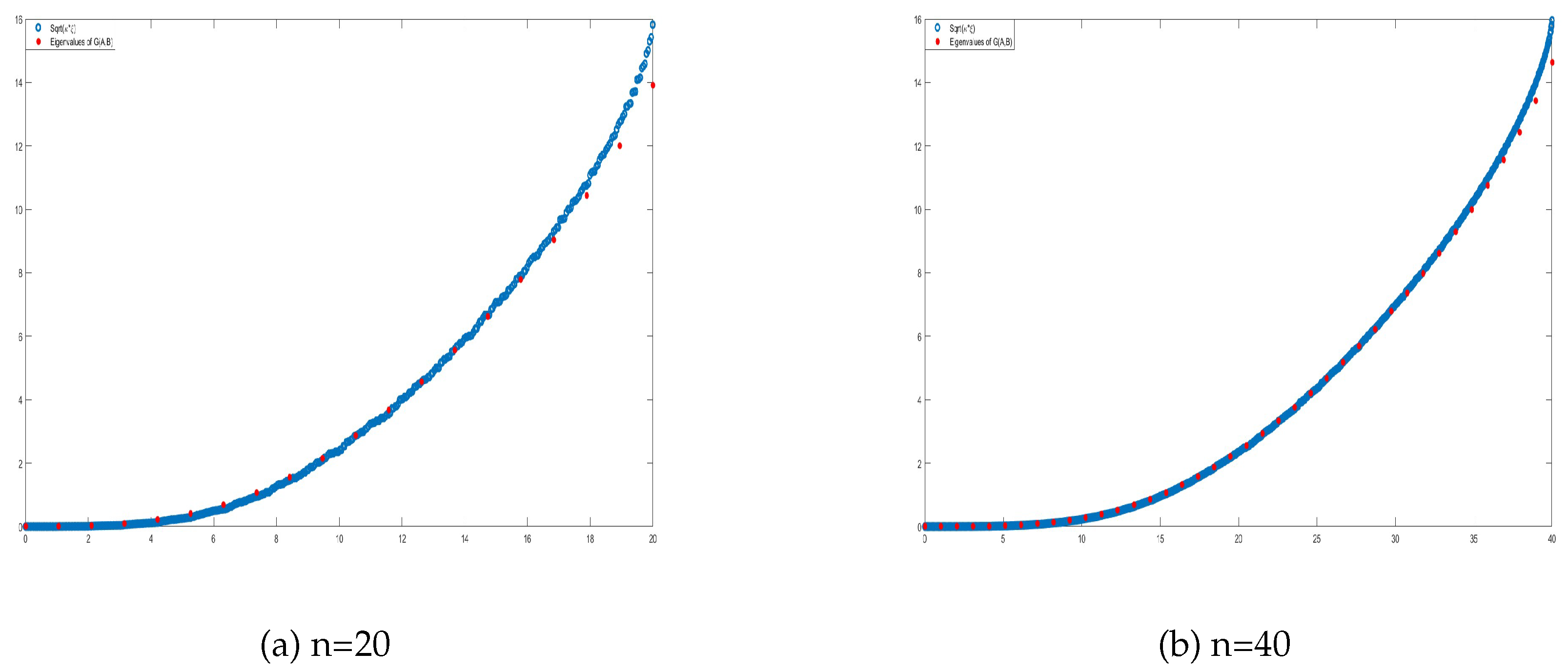

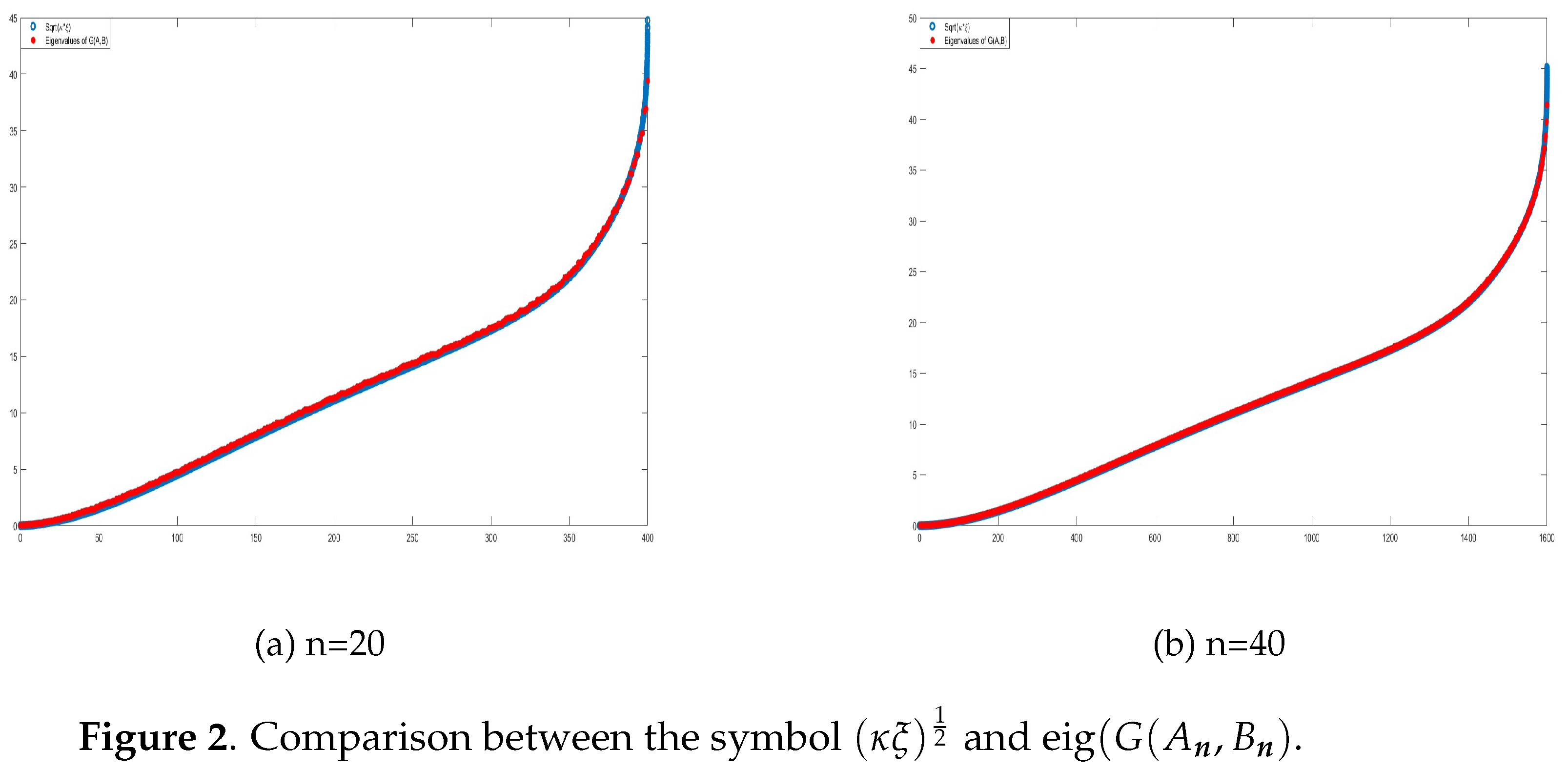

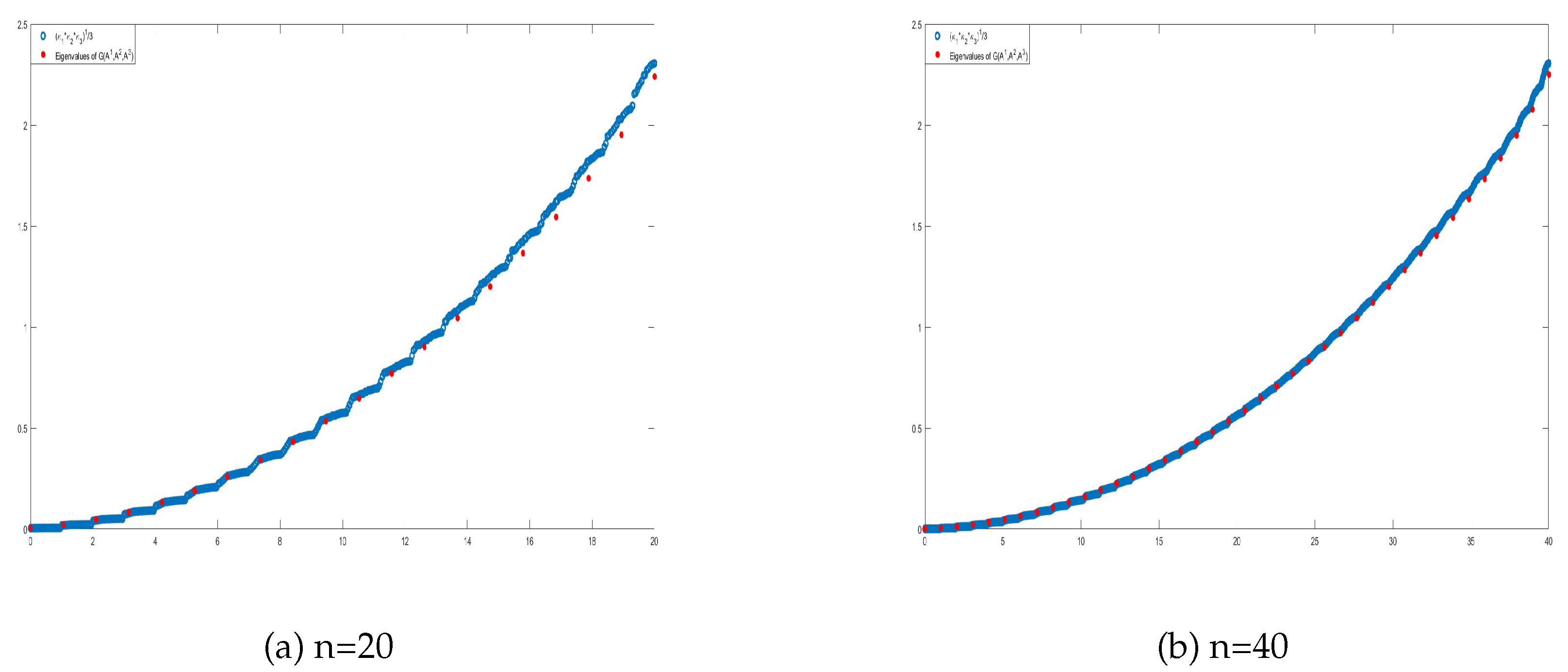

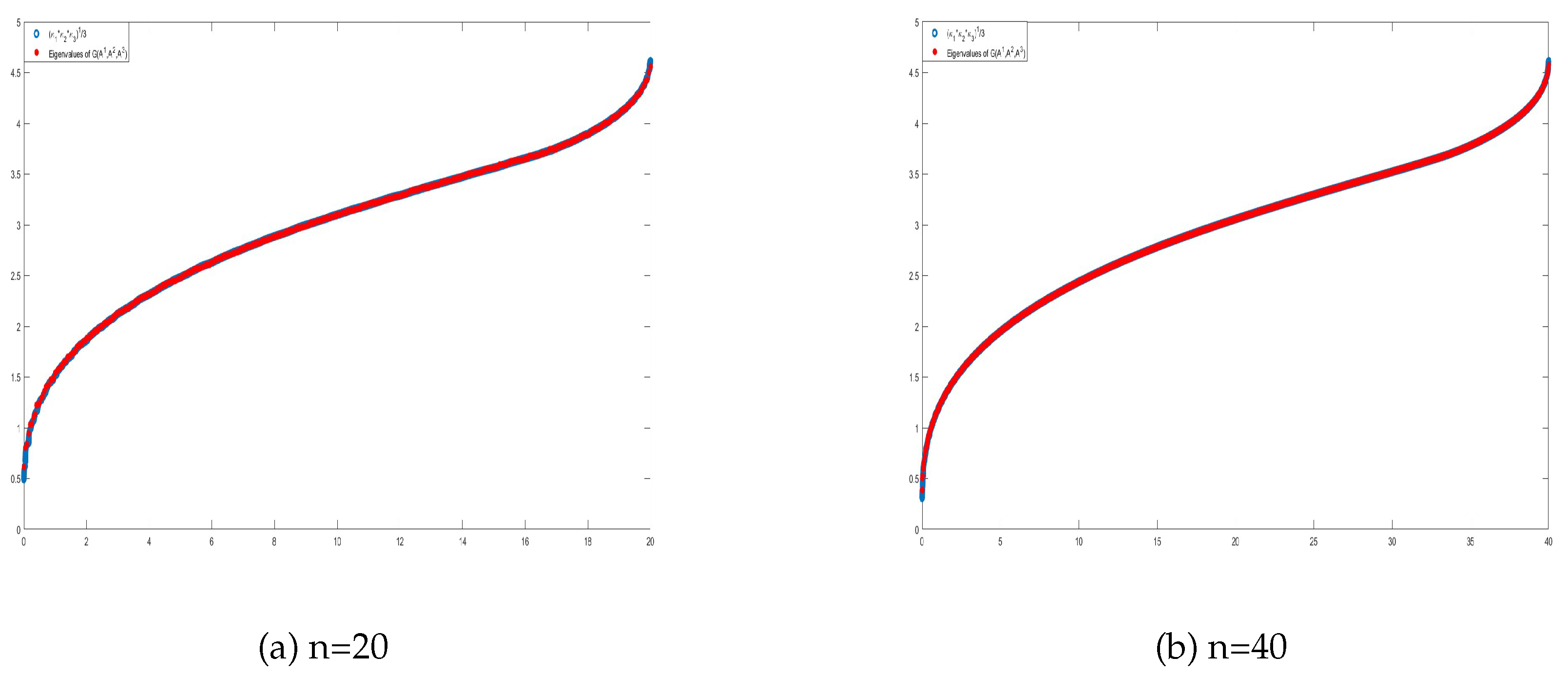

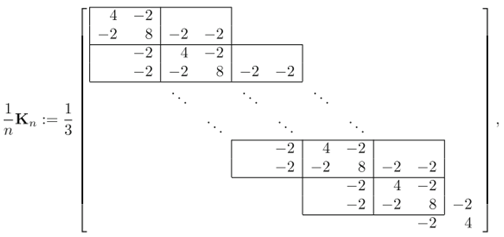

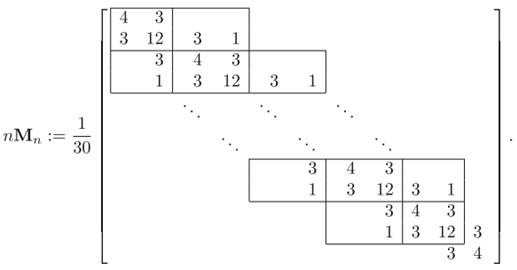

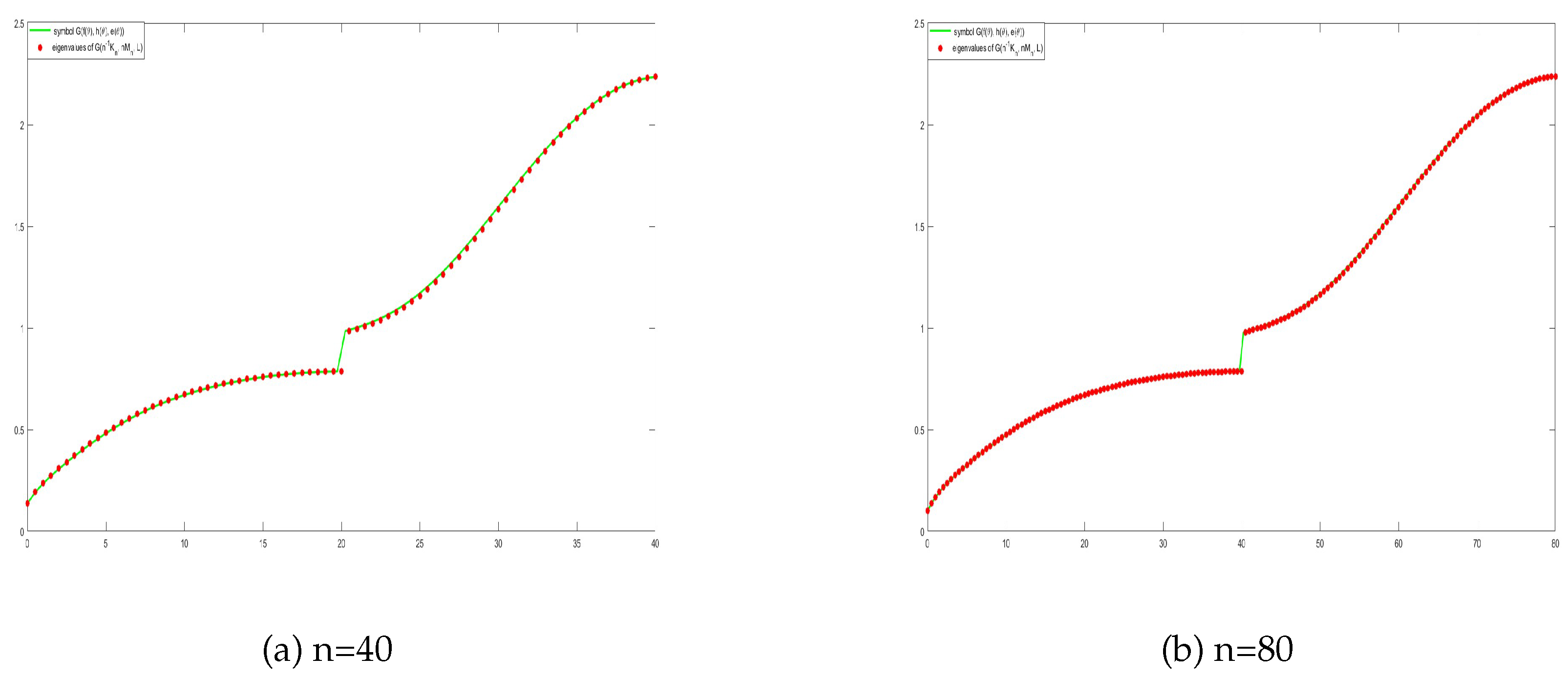

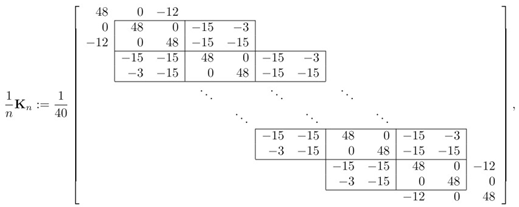

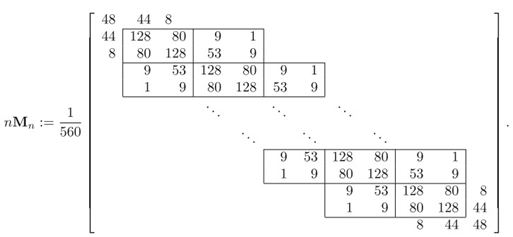

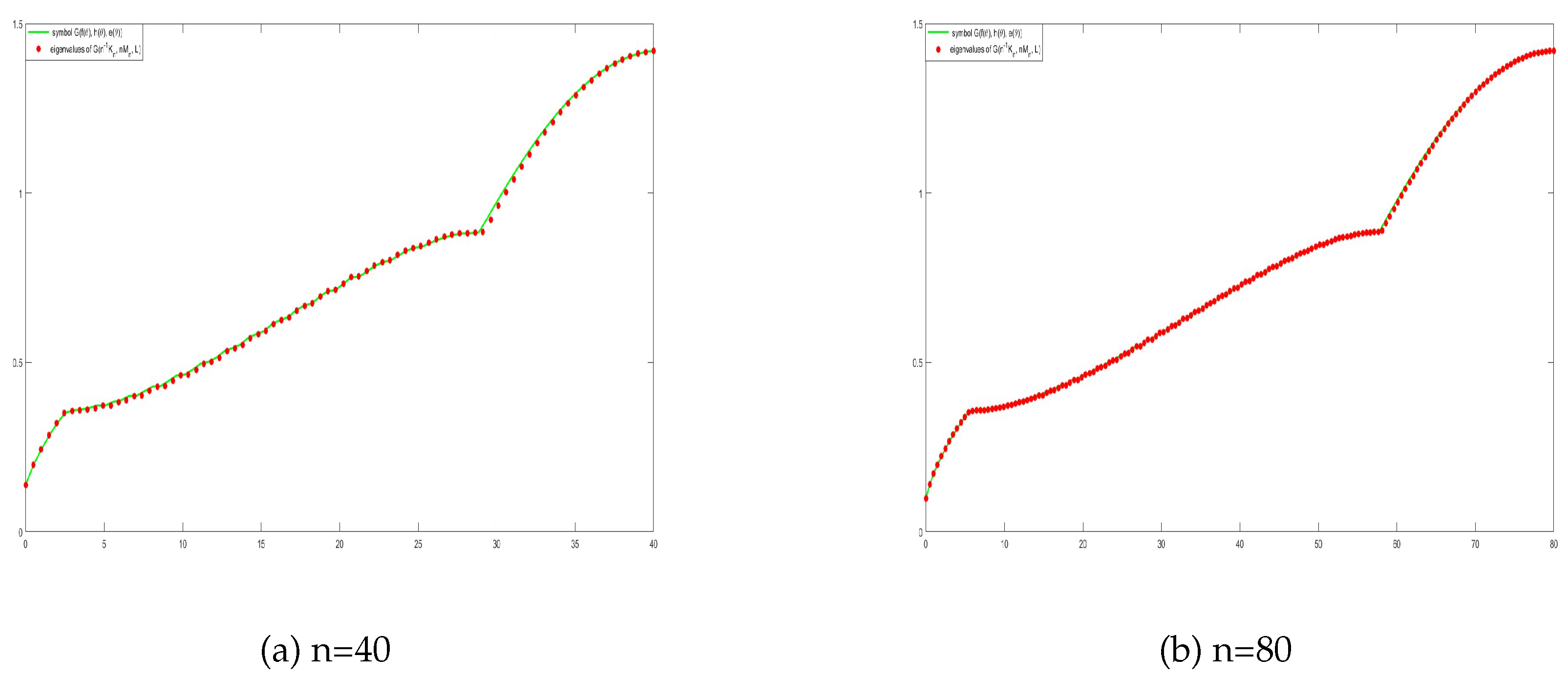

In our study, we consider the analysis of the Karcher mean to matrix-sequences, particularly those arising from the discretization of differential equations, which often form GLT sequences. Numerical results demonstrate that the geometric mean of not only two but more than two GLT matrix-sequences is itself a GLT matrix-sequence, with the symbol of the new sequence given by the geometric mean of the original symbols: the latter is formally proven in the case of two GLT matrix-sequences. Regarding the examples, we consider either scalar unilevel and multilevel GLT matrix-sequences or block GLT asymptotic structures, with special attention to cases stemming from the approximation by local methods of differential operators. By analyzing the spectral distribution of the geometric mean of these matrix-sequences, we provide new insights into the asymptotic behavior of large-scale matrix computations and their potential applications in numerical analysis.

This paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce notations, terminology, and preliminary results concerning Toeplitz and GLT structures, which are essential for the mathematical formulation of the problem and its technical solution. In

Section 3, we present the geometric mean of two matrices and the Karcher mean for more than two matrices, followed by a discussion of the iterative methods employed for their computation: the section contains the GLT theoretical results.

Section 4 contains numerical experiments that illustrate the (asymptotic) spectral behavior of the geometric mean for GLT matrix-sequences in both 1D and 2D settings and in both scalar and block cases. Finally, in

Section 5 we draw conclusions and we punt in evidence few open problems.

2. Preliminaries

In this introduction, we provide the necessary tools for performing the spectral analysis of the matrices involved, based on the theory of uni and multilevel block GLT matrix-sequences.

2.1. Matrices and Matrix-Sequences

Given a square matrix

, we denote by

its conjugate transpose and by

the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse of

A. Recall that

whenever

A is invertible. Regarding matrix norms

refers to the spectral norm and for

, the notation

stands for the Schatten

p-norm defined as the

p-norm of the vector of the singular values. Note that the Schatten

∞-norm, which is equal to the largest singular value coincides with the spectral norm

; the Schatten 1-norm since it is the sum of the singular values is often referred to as the trace-norm; and the Schatten 2-norm coincides with the Frobenius norm. Schatten

p-norms, as important special cases of unitarily invariant norms are treated in detail in a wonderful book by Bhatia [

9].

Finally, the expression matrix-sequence refers to any sequence of the form , where is a square matrix of size with strictly increasing so that as . A r-block matrix-sequence, or simply a matrix-sequence if r can be deduced from context is a special in which the size of is , with fixed and strictly increasing.

2.2. Multi-Index Notation

To effectively deal with multilevel structures it is necessary to use multi-indices, which are vectors of the form . The related notation is listed below

are vectors of all zeroes, ones, twos, etc.

means that for all . In general, relations between multi-indices are evaluated componentwise.

Operations between multi-indices, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, are also performed componentwise.

The multi-index interval

is the set

. We always assume that the elements in an interval

are ordered in the standard lexicographic manner

means that varies from to , always following the lexicographic ordering.

means that .

The product of all the components of is denoted as .

A multilevel matrix-sequence is a matrix-sequence such that n varies in some infinite subset of , is a multi-index in depending on n, and when . This is typical of many approximations of differential operators in d dimensions.

2.3. Singular Value and Eigenvalue Distributions of a Matrix-Sequence

Let be the Lebesgue measure in . Throughout this work, all terminology from measure theory (such as “measurable set,” “measurable function,” “almost everywhere”, etc.) always refers to the Lebesgue measure. Let (resp., ) be the space of continuous complex-valued functions with bounded support defined on (resp., ). If , the singular values and eigenvalues of A are denoted by and , respectively. The set of the eigenvalues (i.e., the spectrum) of A is denoted by .

Definition 1. (Singular value and eigenvalue distribution of a matrix-sequence). Let be a matrix-sequence, with of size , and let be a measurable function defined on a set D with .

In this case, the function ψ is referred to as the eigenvalue (or spectral) symbol of .

The same definition when the considered matrix-sequence shows a multilevel structure. In that case n is replaced by uniformly in and .

The informal meaning behind the spectral distribution definition is as follows: if

is continuous, then a suitable ordering of the eigenvalues

, assigned in correspondence with an equispaced grid on

D, reconstructs approximately the

r surfaces

,

. For example, in the simplest case where

and

,

, the eigenvalues of

are approximately equal — up to a few potential outliers — to

, where

If

and

,

, the eigenvalues of

are approximately equal — again up to a few potential outliers — to

, where

If the considered structure is two-level then the subscript is

and

.

Furthermore, for , a similar reasoning applies.

Finally we report an observation which is useful in the following derivations.

Remark 1. The relation and for all n imply that the range of f is a subset of the closure of S. In particular and positive definite for all n imply that f is nonnegative definite almost everywhere, simply nonnegative almost everywhere if . The same applies when a multilevel matrix-sequence is considered and similar statements hold when singular values are taken into account.

2.4. Approximating Classes of Sequences

In this subsection, we present the notion of the approximating class of sequences and a related key result.

Definition 2 (Approximating class of sequences).

Let be a matrix-sequence and let be a class of matrix-sequences, with and of size . We say that is an approximating class of sequences (a.c.s.) for if the following condition is met: for every j, there exists such that, for every ,

where , , and depend only on j, and

denotes that is an a.c.s. for .

The following theorem represents the expression of a related convergence theory and it is a powerful tool used, for example, in the construction of the GLT *-Algebra

Theorem 1. Let , , with , be matrix-sequences and let be measurable functions defined on a set D with positive and finite Lebesgue measure. Suppose that:

-

1.

for every j;

-

2.

;

-

3.

in measure.

Then

Moreover, if all the involved matrices are Hermitian, the first assumption is replaced by for every j, and the other two are left unchanged, then

We end this section by observing that the same definition can be given and corresponding results (with obvious changes) hold, when the involved matrix-sequences show a multilevel structure. In that case n is replaced by uniformly in , , .

2.5. Matrix-Sequences with Explicit or Hidden (Asymptotic) Structure

In this subsection, we introduce the three types of matrix structures that constitute the basic building blocks of the GLT *-algebras. To be more specific, for any

positive integers we consider the set of

d-level

r-block GLT matrix-sequences. For any

positive integers, the considered set forms a *-algebra of matrix-sequences, which is maximal and is isometrically equivalent to the maximal *-algebra of

-variate

matrix-valued measurable functions (with respect to the Lebesgue measure) defined canonically over

; see [

4,

7,

8,

19,

20,

21] and references therein.

The reduced version is essential when dealing with approximations of integro-differential operators (also in fractional versions) defined over general (non-Cartesian) domains. The idea was presented in [

35,

36] and it was exhaustively developed in [

5], where the GLT symbols are again measurable functions defined over

, with

Peano-Jordan measurable and contained in

. Als the reduced versions form maximal *-algebras isometrically equivalent to the corresponding maximal *-algebras of measurable functions. The considered GLT *-algebras represent rich examples of hidden (asymptotic) structures. Their building blocks are formed by two classes of explicit algebraic structures,

d-level

r-block Toeplitz and sampling diagonal matrix-sequences (see

Section 2.7 and

Section 2.8), plus the asymptotic structures given by the zero-distributed matrix-sequences; see

Section 2.6. It is worth noticing that the latter class plays the role of compact operators with respect to bounded linear operators and in fact they form a two-sided ideal of matrix-sequences with respect to any of the GLT *-algebras.

2.6. Zero-Distributed Sequences

Zero-distributed sequences are defined as matrix-sequences

such that

. Note that, for any

,

is equivalent to

, where

is the

zero matrix. The following theorem (see [

34] and [

20]), provides a useful characterization for detecting this type of sequence. We use the natural convention

.

Theorem 2. Let be a matrix-sequence, with of size . Then

if and only if with and as ;

if there exists such that as .

As in

Section 2.4, the same definition can be given and corresponding result (with obvious changes) holds, when the involved matrix-sequences show a multilevel structure. In that case

n is replaced by

uniformly in

.

2.7. Multilevel Block Toeplitz Matrices

Given

, a matrix of the form

with blocks

,

, is called multilevel block Toeplitz, or more precisely,

d-level

r-block Toeplitz matrix.

Given a matrix-valued function

belonging to

, the

-th Toeplitz matrix associated with

f is defined as

where

are the Fourier coefficients of

f, in which

i denotes the imaginary unit, the integrals are computed componentwise, and

. Equivalently,

can be expressed as

where ⊗ denotes the Kronecker tensor product between matrices and

is the matrix of order

m whose

entry equals 1 if

and zero otherwise.

is the family of (multilevel block) Toeplitz matrices associated with f, which is called the generating function.

2.8. Block Diagonal Sampling Matrices

Given

,

, and a function

, we define the multilevel block diagonal sampling matrix

as the block diagonal matrix

2.9. The *-Algebra of d-Level r-Block GLT Matrix-Sequences

Let be a fixed integer. A multilevel r-block GLT sequence, or simply a GLT sequence if we do not need to specify r, is a special multilevel r-block matrix-sequence equipped with a measurable function , , called symbol. The symbol is essentially unique, in the sense that if are two symbols of the same GLT sequence, then almost everywhere. We write to denote that is a GLT sequence with symbol .

It can be proven that the set of multilevel block GLT sequences is the *-algebra generated by the three classes of sequences defined in

Section 2.6,

Section 2.7,

Section 2.8: zero-distributed, multilevel block Toeplitz, and block diagonal sampling matrix-sequences. The GLT class satisfies several algebraic and topological properties that are treated in detail in [

7,

8,

20,

21]. Here, we focus on the main operative properties, listed below, that represent a complete characterization of GLT sequences, equivalent to the full constructive definition.

GLT Axioms

GLT 1. If then in the sense of Definition 1, with and . Moreover, if each is Hermitian, then , again in the sense of Definition 1 with .

-

GLT 2. We have

- -

if is in ;

- -

if is Riemann-integrable;

- -

if and only if .

-

GLT 3. If and , then:

- -

;

- -

for all ;

- -

;

- -

, provided that is invertible almost everywhere.

GLT 4. if and only if there exist such that and in measure.

-

GLT 5. If and , where

- -

every is Hermitian,

- -

for some constant C independent of n,

- -

,

then .

GLT 6. If and each is Hermitian, then for every continuous function .

Note that, by GLT 1, it is always possible to obtain the singular value distribution from the GLT symbol, while the eigenvalue distribution can only be deduced either if the involved matrices are Hermitian or the related matrix-sequence is quasi-Hermitian in the sense of GLT 5.

3. Geometric Mean of GLT Matrix-Sequences

This section discusses the geometric mean of positive definite matrices, starting with the well-established case of two matrices and then considering multiple matrices. In particular we give distribution results in the case of GLT matrix-sequences.

3.1. Means of Two Matrices

The geometric mean of two positive numbers

a and

b is simply

, a fact well-known from basic arithmetic. However, extending this concept to HPD matrices introduces a number of challenges, as matrix multiplication is not commutative. The question of how to define a geometric mean for matrices in a way that preserves key properties such as congruence invariance, consistency with scalars, and symmetry was solved by ALM [

1]. Their work presented an axiomatic approach to defining the geometric mean of two HPD matrices previously defined in Equation (

1). ALM formalized the geometric mean for matrices by establishing a set of ten essential properties, known as the ALM axioms. These axioms ensure the geometric mean behaves appropriately in the matrix setting. Here are three key properties:

1. Permutation invariance: for all .

2. Congruence invariance: for all and all invertible matrices .

3. Consistency with scalars: for all commuting (note that for all commuting because and is similar to the HPD matrix ).

When considering sequences of matrices, particularly in the framework of GLT sequences, the geometric mean operation is well-preserved under the structure of GLT sequences. If and we consider two scalar unilevel GLT matrix-sequences, that is, and , where are HPD matrices for every n, the matrix-sequence of their geometric mean also forms a scalar unilevel GLT matrix-sequence. The symbol of the resulting sequence is the geometric mean of the individual symbols and .

Theorem 3 ([

20], Theorem 10.2).

Let . Suppose and , where for every n. Assume that at least one between κ and ξ is nonzero almost everywhere. Then

and

The previous result is easily extended to the case of matrix-sequence resulting from the geometric mean of two block multilevel GLT matrix-sequences, thanks to powerful *-algebra structures of considered spaces described in

Section 2.9. Indeed the following two generalizations of Theorem 3 hold.

Theorem 4.

Let and . Suppose and , where for every multi-index . Assume that at least one between κ and ξ is nonzero almost everywhere. Then

and

Proof. Since both

and

are positive definite for every multi-index

, the matrix-sequence

is well defined according to formula (

1) since

is well defined for every multi-index

. According to the assumption, we start with the case where

is nonzero almost everywhere. Hence the matrix-sequence

is a GLT matrix-sequence with GLT symbol

by Axiom

GLT 3, part 3. Since the square root is continuous and well defined over positive definite matrices also the matrix-sequence

is a GLT matrix-sequence with GLT symbol

by virtue of Axiom

GLT 6.

Now using two times

GLT 3, part 2, we infer that

is a GLT matrix-sequence with GLT symbol

, where

is positive definite because of the Sylvester inertia law. Hence the square root of

is well defined and by exploiting again Axiom

GLT 6 we deduce that

is a GLT matrix-sequence with GLT symbol

. Finally, by exploiting Axiom

GLT 3, part 3, we have

is a GLT matrix-sequence with GLT symbol

and the application of

GLT 3, part 2, two time leads to the desired conclusion

where the latter and Axiom

GLT 3 imply

.

Finally the other case where

is nonzero almost everywhere has the very same proof since

is invariant under permutations and hence

so that the the same steps can be repeated by exchanging

and

. •

Theorem 5.

Let . Suppose and , where for every multi-index . Assume that at least one between the minimal eigenvalue of κ and the minimal eigenvalue of ξ is nonzero almost everywhere. Then

and

Furthermore whenever the GLT symbols κ and ξ commute.

Proof. The case of is already contained in Theorem 4, so we assume i.e. a true GLT block setting. The proof is in fact a repetition of that of the previous theorem with the only attention to GLT symbol part where the multiplication is noncommutative.

Since both

and

are positive definite for every multi-index

, the matrix-sequence

is well defined according to formula (

1) since

is well defined for every multi-index

. According to the assumption, we start with the case where

is invertible almost everywhere so that

by Axiom

GLT 3, part 3, and

thanks to Axiom

GLT 6.

Now using two times

GLT 3, part 2, we have

, where

is positive definite because of the Sylvester inertia law. Hence the square root of

is well defined and by exploiting again Axiom

GLT 6 we obtain

. Finally, by exploiting Axiom

GLT 3, part 3, on the matrix-sequence

and using

GLT 3, part 2, two times, we conclude

where the symbol

is exactly

. Furthermore, relation (

11) and Axiom

GLT 3 imply

where

, whenever

and

commute.

Finally the remaining case where

is invertible almost everywhere has the very same proof since

is invariant under permutations and hence

so that the the same steps can be repeated by exchanging

and

and by exchanging

and

. •

3.2. Mean of More Than Two Matrices

In this section, we describe the iterative method used to compute the Karcher mean for more than two HPD matrices. The Karcher mean is an extension of the geometric mean to more than two matrices and can be computed using an iterative method based on the Richardson-like iteration. As detailed earlier in the introduction (see Equation

6), the iteration updates the approximation at each step based on the logarithmic correction term. The step-size parameter

is dynamically computed during the iteration, ensuring that the process converges efficiently by accounting for the condition numbers of the matrices involved.

Specifically,

is given by

with

and

computed as

where

and

G is the current approximation of the Karcher mean.

The Richardson-like iteration can be implemented in different equivalent forms

Among these equivalent formulations, the first one, Equation (

15), is the most practical for implementation. It avoids matrix inversions, which can introduce numerical instabilities and increase computational complexity. While formulations Equation () and Equation () aim to reduce the number of matrix inversions, the final step requires inverting the result, which can lead to inaccuracies, especially for poorly conditioned matrices. Additionally, Equation () retains the simplicity of direct matrix operations without introducing unnecessary complications. A numerically more efficient approach uses Cholesky factorization to reduce the computational cost of forming matrix square roots at every step, enhancing efficiency as forming the Cholesky factor costs less than computing a full matrix square root [

24].

Suppose

is the Cholesky decomposition of

, where

is an upper triangular matrix. The iteration step can be rewritten as

In this formulation, the Cholesky factor

is updated at each iteration. The condition number of the Cholesky factor

in the spectral norm is the square root of the condition number of

, thus ensuring good numerical accuracy. For this heuristic to be effective, it is essential that

provides a good approximation of

G. Therefore, selecting

as the Cheap mean is critical. An adaptive version of this iteration has been proposed and implemented in the Matrix Means Toolbox [

11].

Of course the Richardson-like iteration is relevant for computing efficiently the Karcher mean: we also exploit its formal expression for theoretical purposes when dealing with sequences of matrices, particularly those involving GLT sequences. For the theory we come back at relation (

15) and we consider the associated iteration

with

given positive definite matrix. We know that

converges to the geometric mean of

as

tends to infinity for every fixed positive definite initial guess

.

Fix . Suppose now that the block multitivel sequence of matrices for are given, where are positive definite for every multi-index .

Due to the positive definiteness of the matrices and because of , from Axiom GLT 1 it follows that each is nonnegative definite almost everywhere (see Remark 1).

In this setting, it is conjectured that the sequence of Karcher means

forms a new GLT matrix-sequence whose symbol is the geometric mean of the individual symbols

, specifically

if all symbols commute and

in the general case. In order to attack the problem the initial guess matrix-sequence

must be of GLT type with nonnegative definite GLT symbol. In this way thanks to (

20) and using the GLT axioms in the way it is done in Theorem 5, we deduce easily that

is still a GLT matrix-sequence with symbol

converging to

.

Finally Theorem 1 and Axiom GLT 4 could be applied if we prove that if an a.c.s. for the limit sequence . This could be proven using Schatten estimates like those in the second item of Theorem 2, but at the moment this is not easy because the known convergence proofs for the Karcher iterations are all based on pointwise convergence.