1. Introduction

Cardiac surgery associated acute kidney injury (CSA-AKI) occurs in 5 to 50% of patients, resulting in prolonged hospital length of stay, high medical costs and poor outcome [

1]. Changes in plasma creatinine levels and urine output are used to define AKI with its most severe form requiring renal replacement therapy, in 5–13% of critically-ill patients [

2]. Poor performance in predicting the occurrence of AKI was obtained with a variety of serum and urinary biomarkers, such as neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP)), interleukin-18 (IL-18)), as well as tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 associated with insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (TIMP-2 × IGFBP-7) [

3]. Since CSA-AKI increases morbidity and mortality, research efforts are focused in prevention, personalized risk stratification of AKI and development of reno-protective interventions [

4].

Several predisposing factors of CSA-AKI have been identified, such as cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, nephrotoxic agents (i. e., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system, radiologic contrast media), and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and aortic clamp time [

5].

During cardiac surgery, multiple renal stressors are acting as a result of the intense neuro-endocrine and inflammatory response, ischemia-reperfusion injuries, non-pulsatile blood flow as well as exposure to artificial materials and homologous blood products.[

5] Besides low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS) and episode of hypoxemia, intrarenal vasoconstriction consequent to the release of endogenous mediators (i.e., thromboxane, endothelin, vasopressin, angiotensin II) and/or the administration of vasopressors further contribute to impair macro- and microvascular flow leading to ischemic glomerular and tubular injuries [

6].

In critically ill patients, renal vasoconstriction is an early manifestation of AKI.[

6] Using Doppler ultrasound, the renal resistive index (RRI) is computed as the ratio of the difference between maximum and minimum flow velocity to maximum flow velocity. This readily available parameter reflects the alteration in blood flow profile within the intrarenal arcuate and interlobar arteries. Elevated RRI is frequently reported in elderly patients, those with atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and rejection of renal allograft [

7].

In the current study, we measured renal arterial blood flow before surgery and upon admission in the intensive care unit (ICU) and we questioned whether determination of RRI could predict the development of AKI within the first five days after cardiac surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a prospective, observational, clinical study including adult patients (> 18 years) undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery at the University Hospital of Fort-de-France, in Martinique. The study was approved by the Committee on Health Research Ethics (Comité de protection des personnes, University of Bordeaux) and was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guidelines outlined in the declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed signed consent. Preoperative end-stage renal insufficiency (dialysis or hemofiltration) and poor abdominal echogenicity or no visualization of the renal vessels were considered exclusion criteria. Patients requiring extracorporeal life support for weaning from CPB were secondarily excluded due to the non-pulsatile flow pattern.

2.2. Clinical, Hemodynamic and Laboratory Variables

Demographic, clinical and surgical data were collected from the hospital electronic medical files. To evaluate the risk of postoperative AKI, the Cleveland score was computed based on preoperative information (gender, previous cardiac surgery, chronic obstructive lung disease, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction <35%, use of intraaortic balloon pump [IABP] and serum creatinine level).[

8] To assess the overall risk of perioperative mortality, the European System Operative Score Risk Evaluation score (EuroSCORE II) was calculated. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), central venous pressure, central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO

2) and hematocrit were measured after anaesthesia induction and at the end of surgery.

2.3. Perioperative Procedure

General anesthesia with intravenous administration of propofol, sufentanil and rocuronium was targeted to maintain bispectral index between 40 and 60 and MAP in a range of +/- 20% of preoperative values (and above 60 mmHg). For antibiotic prophylaxis, cefazoline was administered upon induction of anesthesia. Surgical procedures were conducted under cold blood cardioplegia and closed-circuit cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). After aortic unclamping and recovery of satisfactory spontaneous heart rate rhythm or pacing-stimulated heart rate, weaning from CPB was guided by transoesophageal echocardiography under optimal volume loading conditions.[

9] Inotropes (dobutamine, epinephrine) and noradrenaline infusion were initiated in the presence of new/worsening ventricular dysfunction and/or low MAP (< 70 mmHg) that was not responsive to fluid loading and optimization of heart rhythm. Conversely, the decision to withdraw inotropic support was taken if the hemodynamic condition improved steadily. Protective lung ventilation was applied and patients were extubated within the first 6h after admission in ICU. Transfusion of red blood cells was given to maintain hemoglobin levels above 70g/L.

2.4. Study Timeline

On the last weekday preceding surgery, a baseline ultrasound examination was performed, blood samples were taken, and demographic patient characteristics were obtained. The ultrasound examination was repeated within 1h upon arrival in the ICU under continuous sedation and mechanical ventilation. Serum creatinine was measured daily after surgery until the fifth postoperative day or until discharge in patients with AKI.

2.5. Ultrasound Examination and Measurements

Ultrasound examinations were performed by two independent well-trained sonographers who were not involved in patient care while the anesthesia and ICU physicians were blinded to the results of renal Doppler measurements. The same operator performed pre-and postoperative examination on the same patients placed on the supine position and using a CX-50 ultrasound machine with a curvilinear 5MHz pulsed-wave Doppler flow probe (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, Netherland). On each kidney, recordings with the best imaging quality were selected in the longitudinal axis. Pulsed wave Doppler curves in the interlobar or arcuate arteries were recorded with a sample volume of 2-4 mm, three measurements were performed on each kidney and then were averaged (

Figure 1). The perioperative change in RRI (dRRI) was computed as the ratio of the difference between preoperative and postoperative RRI to postoperative RRI (dRRI = [preoperative RRI – postoperative RRI]/preoperative RRI).

2.6. Study Endpoints

CSA-AKI was defined by the change in postoperative plasma creatinine relative to preoperative measurements, according to the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) classification (

Table 1).[

10] Plasma creatinine taken on the last weekday before surgery served as the baseline reference. Based on the maximum plasma creatinine within the first five postoperative days, CSA-AKI was further categorized into AKI severity levels: no injury (AKI-0), mild or stage 1 AKI (Risk, stage AKI-1), moderate or stage 2 AKI (AKI-2) and severe or stage 3 (AKI-3).

Use of vasoactive medication, durations of cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping as well as ICU and hospital stay were retrieved from the patient medical file. A LCOS was defined by impaired ventricular contractility despite appropriate volume loading that require the administration of at least 1 inotrope (dobutamine, epinephrine) over at least 6 hours.[

11]

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Given the exploratory nature of the study and scant data in the literature, it was not possible to formulate a hypothesis and perform a power analysis for sample size calculation. Due to the small number of patients, data from AKI-0 and AKI-1 were merged together as well as those from AKI-2 and AKI-3, to distinguish between mild or absent AKI and moderate to severe AKI.

Patient and clinical characteristics were compared using Student t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables when appropriate and the χ2 test for dichotomous variables.

To determine the discriminative values of the RRI (preoperative, postoperative and dRRI) and other potential predictors of CSA-AKI, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed. The area under the curve (AUC) was determined with the optimal cut-off for sensitivity and specificity using Youden’s J statistic. A backward stepwise multivariable regression analysis was computed to determine independent predictors of AKI, including significant variables as confounders with a maximum of n/10 variables. A multivariate model was identified applying a p-entry and removal of less than 0.05. Collinearity and interactions were tested and the Hoshmer-Lemeshow test was used to check goodness-of-fit of the model. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 23.0.6 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium;

https://www.medcalc.org; 2024).

3. Results

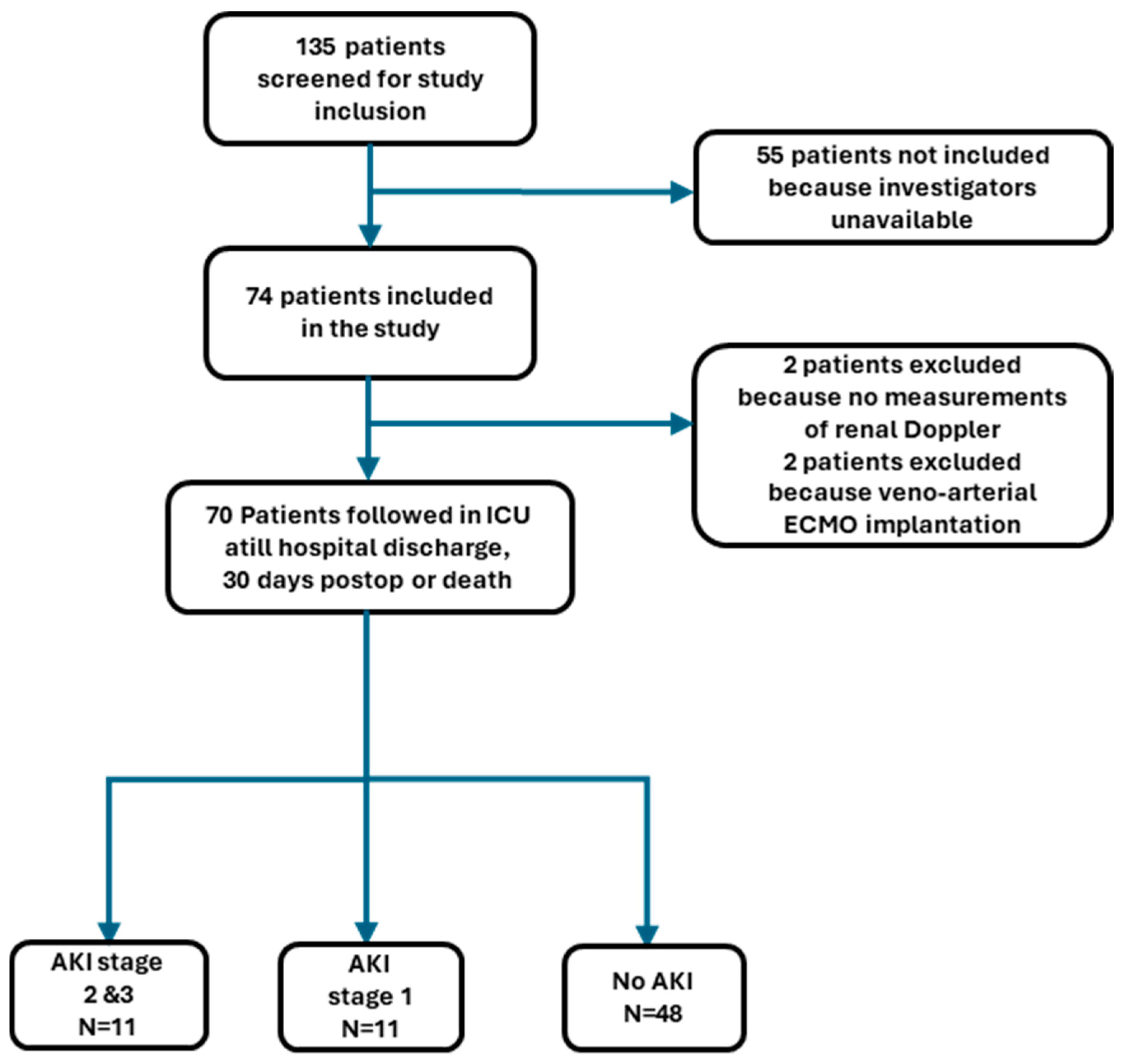

In this prospective study, 135 patients were screened, 74 were enrolled and 70 remained in the final analysis, 4 patients being secondarily excluded (

Figure 2).

Within the first 5 postoperative days, 22 patients developed AKI, of whom 11 developed stage 1 and 11 stage 2 or 3. Baseline characteristics and intraoperative data are displayed in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Compared with patients with no or mild CSA-AKI (AKI-0/1), those with moderate to severe CSA-AKI (AKI 2/3), were older, exhibited higher Cleveland score values, lower hematocrit levels and were more likely to receive blood transfusion and inotropic support after weaning from CPB. The type of surgery, duration of aortic clamping and intraoperative hemodynamic parameters did not differ between the 2 groups.

Postoperatively, LCOS developed in 3 and 2 patients with CSA-AKI-2/3 and CSA-AKI-0/1, respectively (27.3% vs 3.4%, P=0.045) The hospital length of stay was longer in patients with CSA-AKI-2/3 than in those with CSA-AKI-0/1 (28[15] days vs 10 [4,2] days, P = 0.016). Five patients with CSA-AKI-2/3 died within 30 days after surgery whereas all patients with CSA-AKI-0/1 survived until discharge or 30 days after surgery. Among surviving patients with AKI-2/3 at 30 days after surgery, 2 required renal replacement therapy.

Preoperative and postoperative RRI are illustrated in

Figure 3. Preoperative RRI did not differ between subjects with AKI-0/1 and those with AKI-2/3 (P=0.290). Compared with preoperative measurements, postoperative RRI increased by a mean of 10.9% in patients with AKI-2/3 (P=0.004), while it decreased by a mean of -5.3% in those with AKI-0/1 (P< 0.001).

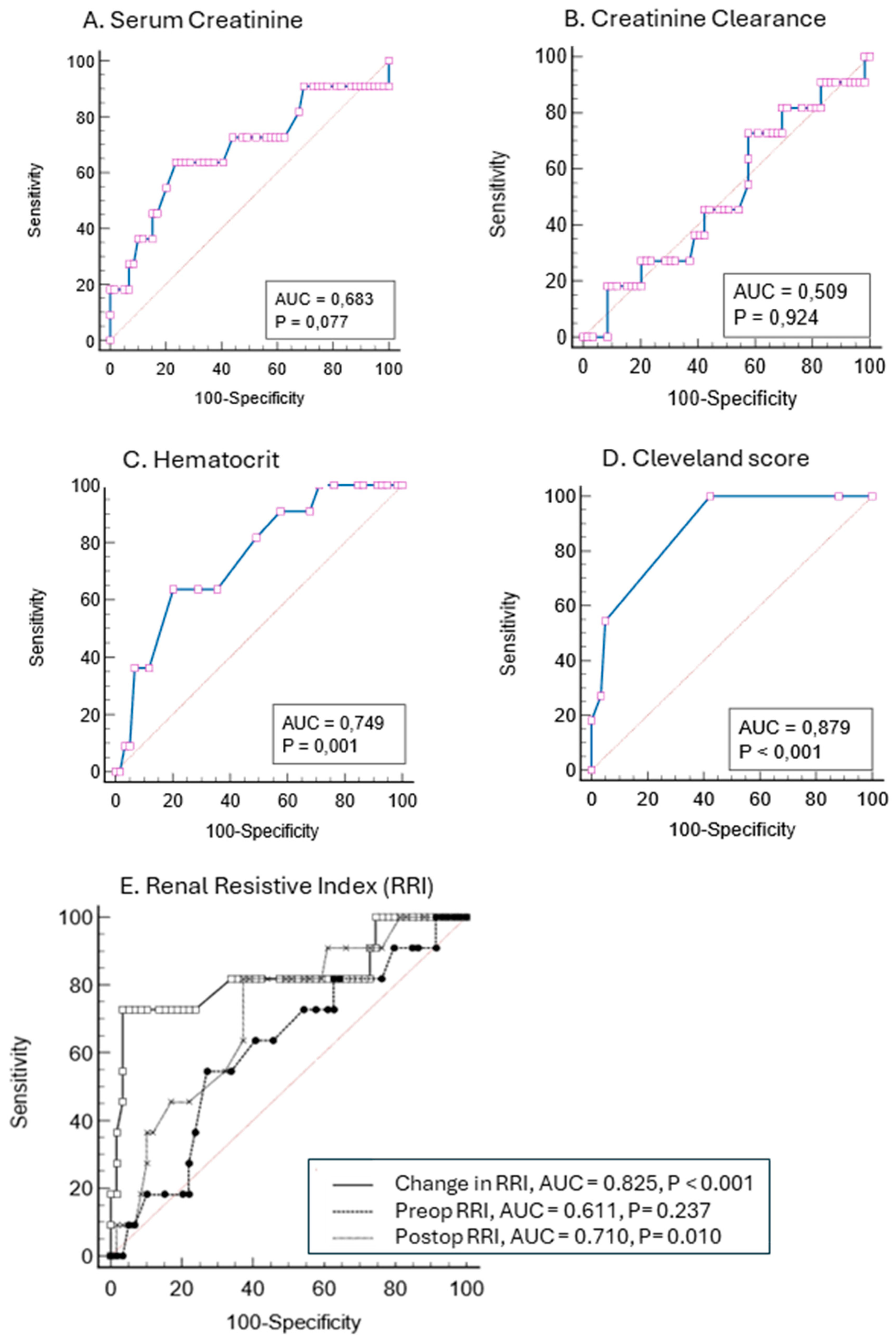

As shown in

Figure 4, the ROC-AUC of preoperative serum creatinine levels and creatinine clearance showed poor discrimination for predicting CSA-AKI-2/3 (AUC <0.7), hematocrit levels provided intermediate discrimination (AUC of 0.749) while the Cleveland score offered better discrimination with a ROC-AUC of 0.879 (sensitivity 100% and specificity 57%). The ROC-AUC of postoperative RRI to predict CSA-AKI-2/3 was 0.710 (sensitivity 81.8% and specificity 62.7%) with an optimal cut-off point for discrimination at 0.68. The ROC of the dRRI provided better discrimination with an AUC of 0.825 (sensitivity 72.7% and specificity 96.6%) and an optimal cut-off point at 9.4% (positive and negative prediction value of 80% and 95%, respectively).

The multivariate regression analysis yielded 3 independent predictors for AKI-2/3, the Cleveland score, dRRI and the need for combined inotropic support (

Table 4). This model has a ROC-AUC of 0.917 (95% CI 0.825-0.970).

4. Discussion

In this prospective, unblinded, observational pilot study, our data confirm the usefulness of the Cleveland score to predict CSA-AKI (stage 2 and 3) while the changes in perioperative Doppler-derived RRI were helpful to identify the ongoing process of CSA-AKI.

4.1. Relationship with Previous Studies

In agreement with previous reports,[

1] we found a 31.4% incidence of CSA-AKI, 50% being mild and transient (stage 1) and the other persisting till ICU discharge or death. The whole study population was considered at moderate risk of major perioperative complications owing to a mean EuroSCORE of 5.2 and a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus (44.3%) and heart failure (28.6%). The predominance of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity (79%) could represent an additional risk factor. Indeed, analysis of the US 2001-2020 National Inpatient Sample, demonstrated that black race was independently associated with the development of AKI after cardiac surgery.[

12]

Various simple tools have been proposed to identify and monitor patients at risk for AKI, namely serum creatinine and its derivative creatinine clearance that takes into account patient’s body weight, gender and age.[

4] However, plasma creatinine levels and estimated glomerular filtration have failed to predict CSA-AKI and, when used postoperatively, the diagnosis of kidney dysfunction usually lags by 24 to 48 hours the onset of renal insult.[

1] In contrast, a composite tool such as the Cleveland score that incorporates preoperative clinical and biological variables has been validated to accurately predict the advanced severe stage of AKI that necessitates renal replacement therapy after open-heart surgery.[

8] In the current study, the Cleveland score largely outperformed both preoperative serum creatinine and postoperative RRI whereas chronic treatments (i.e., inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system) and creatinine clearance derived from the Cockroft-Gault equation were unrelated to the development of CSA-AKI-2/3. Interestingly, preoperative anemia and LCOS were also associated with the development of AKI-2/3. After multivariate regression analysis, only the Cleveland score, dRRI and unstable hemodynamics remained independent risk factors of CSA-AKI-2/3.

Determination of RRI upon admission in the ICU was a moderate marker of AKI-2/3 with an ROC-AUC of 0.71 and an optimal cut-off value at 0.68 (sensitivity of 81.8% and specificity of 62.7%). A meta-analysis of 18 trials including 1656 patients, supports the contention that early postoperative Doppler-derived RRI may help to identify AKI in critically-ill patients admitted in the ICU, with better discrimination among patients undergoing surgical procedures than in those treated for sepsis (AUC of 0.88 vs 0.80, respectively).[

13] The median diagnostic cut-off for RRI varied between 0.68 and 0.74. In line with these data, another meta-analysis focusing on surgical patients (10 trials, N=911) indicated better performance of postoperative rather preoperative RRI measurements to predict AKI, particularly for the persistent forms.[

14] Although postoperative determination of RRIs convey more relevant information to identify CSA-AKI, large variations in ROC-AUCs (from 0.61 to 0.93) and cut-off values (from 0.68 to 0.85) are related to different patient populations, type of cardiac procedures as well as the prevalence and definition criteria of AKI (

Table 5).[

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]

Recently, preoperative determination of the renal functional reserve by calculating RRI after protein loading or abdominal compression has been shown effective in identifying patients prone to develop AKI after major surgery.[

23,

24]

4.2. Study Implications

In this study sample, perioperative RRI measurements demonstrated opposite changes in the 2 subgroups: RRI increasing by a mean 10.9% in CSA-AKI 2/3 and decreasing by a mean 5.3% in CSA-AKI 0/1 patients. The clinical relevance of dRRI measured in each surgical patient resides in its high negative predictive value suggesting that the risk of CSA-AKI is very low when dRRI is below 9.4%. The Doppler-derived RRIs integrate the combined effects of circulatory volume, intra-abdominal pressure, arterial and venous pressure as well as extrinsic and intrinsic renal regulation.[

25] Hence, the ability to maintain or decrease RRI postoperatively (CSA-AKI 0/1 group), reflects the physiological adaptive mechanisms involving myogenic autoregulation, tubulo-glomerular feedback and endogenous vasodilators (i.e., nitric oxide, adenosine, eicosanoids) that tend to preserve renal blood flow and mitigate neuroendocrine and inflammatory responses.[

6] Conversely, the increased dRRI (>9.3%) in patients with CSA-AKI 2/3, reflects the inability of the kidneys to adapt to the stressful events owing to preexisting poor renal functional reserve and/or the high burden of vasoconstrictive agents and ischemic/inflammatory insults.[

7]

5. Study Strengths and Limitations

The aim of this observational study was to question the impact of perioperative determination of RRI in AKI risk assessment. Other strengths include the prospective design and assessment of multiple additional baseline variables.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged, First, this single-centre study included a small sample of patients undergoing a variety of cardiac interventions. The lack of statistical power precluded the analysis of potential risk factors (i.e., duration of aortic clamping, treatment with inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system, advanced age, preexisting renal dysfunction) and to assess the added value of RRI. Secondly, we did not provide continuous hemodynamic data, although perioperative hypotension is a well-documented risk factor of CSA-AKI. Nevertheless, the higher incidence of LCOS in the CSA-AKI-2/3 group suggests unstable circulatory conditions among these patients that contribute to CSA-AKI. Thirdly, the Doppler-derived RRI determination is prone to operator-dependent error. Although intra-and interobserver variability was not determined, the two operators demonstrated a large experience with ultrasound measurements and previous studies indicated variability coefficients below 10%.[

16] Finally, as we did not reassess Doppler-derived RRI before hospital discharge, we were unable to detect reversible or persistent change in RRI in patients recovering or not from CSA-AKI.

6. Conclusions

Perioperative determination of the changes in Doppler-derived RRI is helpful to detect patients at risk of CSA-AKI. Our data indicate that postoperative increases in RRI are predictive of moderate-to-severe AKI.

Artificial intelligence, machine learning and bioinformatics should be used to screen large database of cardiac surgical patients and update the prediction model for AKI risk stratification. Future trials should also evaluate hemodynamic and pharmacologic goal-directed interventions to reverse elevated RRI and prevent the ongoing process of AKI.[

26]

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., N.D. and C.I.; methodology, R.B., N.D. and M.S.; software M.S., H.M. and M.L.; validation, M.S, N.D., C.I. and R.B.; formal analysis, M.S., H.M. and M.L..; investigation, M.S. N.D. and C.I; resources, C.I., N.D. and M.S.; data curation, M.S, N.D., C.I. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, ML; writing—review and editing, M.L., M.S. and H.M.; visualization, M.L., M.S., H.M., N.D. and C.I.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Comité de protection des personnes, University of Bordeaux, UB-2014-11).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients received detailed information and signed consent for the study was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vives, M.; Hernandez, A.; Parramon, F.; Estanyol, N.; Pardina, B.; Muñoz, A.; Alvarez, P.; Hernandez, C. Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery: Prevalence, Impact and Management Challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2019, 12, 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Stevens, P.E. Summary of KDIGO 2012 CKD Guideline: Behind the Scenes, Need for Guidance, and a Framework for Moving Forward. Kidney International 2014, 85, 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.-C.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chiou, T.T.-Y.; Shiao, C.-C.; Wu, C.-H.; Huang, C.-T.; Wang, T.-J.; Chen, J.-Y.; Liao, H.-W.; Chen, S.-Y.; et al. Comparative Accuracy of Biomarkers for the Prediction of Hospital-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care 2022, 26, 349. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.K.; Shaw, A.D.; Mythen, M.G.; Guzzi, L.; Reddy, V.S.; Crisafi, C.; Engelman, D.T. Adult Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Joint Consensus Report. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 2023, 37, 1579–1590. [CrossRef]

- Scurt, F.G.; Bose, K.; Mertens, P.R.; Chatzikyrkou, C.; Herzog, C. Cardiac Surgery–Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney360 2024, 5, 909–926. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Kurtcuoglu, V. Renal Blood Flow and Oxygenation. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2022, 474, 759–770. [CrossRef]

- Darabont, R.; Mihalcea, D.; Vinereanu, D. Current Insights into the Significance of the Renal Resistive Index in Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 1687. [CrossRef]

- Thakar, C.V.; Arrigain, S.; Worley, S.; Yared, J.-P.; Paganini, E.P. A Clinical Score to Predict Acute Renal Failure after Cardiac Surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005, 16, 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Licker, M.; Diaper, J.; Cartier, V.; Ellenberger, C.; Cikirikcioglu, M.; Kalangos, A.; Cassina, T.; Bendjelid, K. Clinical Review: Management of Weaning from Cardiopulmonary Bypass after Cardiac Surgery. Ann Card Anaesth 2012, 15, 206. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.A.; Jorge, S. The RIFLE and AKIN Classifications for Acute Kidney Injury: A Critical and Comprehensive Review. Clin Kidney J 2013, 6, 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Schoonen, A.; Van Klei, W.A.; Van Wolfswinkel, L.; Van Loon, K. Definitions of Low Cardiac Output Syndrome after Cardiac Surgery and Their Effect on the Incidence of Intraoperative LCOS: A Literature Review and Cohort Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 926957. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Ramphul, K.; Bawna, F.; Paray, N.B.; Dulay, M.S.; Dhaliwal, J.S.; Aggarwal, S.; Mactaggart, S.; Chennapragada, S.S.; Sombans, S.; et al. Trends in Mortality among the Geriatric Population Undergoing Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) and Potential Racial Disparities: A 20-Year Perspective via the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 2024, 21, 716–722. [CrossRef]

- Jianing, Z., Md; Ying, Z., Md; Xiaoming, L., Md; Qiuyang, L., Md, Phd; Yukun, L., Md, Phd Doppler-Based Renal Resistive Index for Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advanced Ultrasound in Diagnosis and Therapy 2021, 5, 183. [CrossRef]

- Bellos, I.; Pergialiotis, V.; Kontzoglou, K. Renal Resistive Index as Predictor of Acute Kidney Injury after Major Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Critical Care 2019, 50, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Bossard, G.; Bourgoin, P.; Corbeau, J.J.; Huntzinger, J.; Beydon, L. Early Detection of Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury by Doppler Renal Resistive Index in Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Br J Anaesth 2011, 107, 891–898. [CrossRef]

- Guinot, P.-G.; Bernard, E.; Abou Arab, O.; Badoux, L.; Diouf, M.; Zogheib, E.; Dupont, H. Doppler-Based Renal Resistive Index Can Assess Progression of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 2013, 27, 890–896. [CrossRef]

- Hertzberg, D.; Ceder, S.L.; Sartipy, U.; Lund, K.; Holzmann, M.J. Preoperative Renal Resistive Index Predicts Risk of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 2017, 31, 847–852. [CrossRef]

- Peillex, M.; Marchandot, B.; Bayer, S.; Prinz, E.; Matsushita, K.; Carmona, A.; Heger, J.; Trimaille, A.; Petit-Eisenmann, H.; Jesel, L.; et al. Bedside Renal Doppler Ultrasonography and Acute Kidney Injury after TAVR. JCM 2020, 9, 905. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, T.; Fan, Z. Prediction Efficiency of Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury in Acute Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection Patients with Renal Resistive Index and Semiquantitative Color Doppler. Cardiology Research and Practice 2019, 2019, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Regolisti, G.; Maggiore, U.; Cademartiri, C.; Belli, L.; Gherli, T.; Cabassi, A.; Morabito, S.; Castellano, G.; Gesualdo, L.; Fiaccadori, E. Renal Resistive Index by Transesophageal and Transparietal Echo-Doppler Imaging for the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Major Heart Surgery. J Nephrol 2017, 30, 243–253. [CrossRef]

- Sinning, J.-M.; Adenauer, V.; Scheer, A.-C.; Cachiguango, S.J.L.; Ghanem, A.; Hammerstingl, C.; Sedaghat, A.; Müller, C.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Grube, E.; et al. Doppler-Based Renal Resistance Index for the Detection of Acute Kidney Injury and the Non-Invasive Evaluation of Paravalvular Aortic Regurgitation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. EuroInterv 2014, 9, 1309–1316. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-B.; Qin, H.; Ma, W.-G.; Zhao, H.-L.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.-R.; Sun, L.-Z. Can Renal Resistive Index Predict Acute Kidney Injury After Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Repair? Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 104, 1583–1589. [CrossRef]

- Husain-Syed, F.; Ferrari, F.; Sharma, A.; Danesi, T.H.; Bezerra, P.; Lopez-Giacoman, S.; Samoni, S.; De Cal, M.; Corradi, V.; Virzì, G.M.; et al. Preoperative Renal Functional Reserve Predicts Risk of Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Operation. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2018, 105, 1094–1101. [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Samoni, S.; Muzzi, M.; Fabbri, S.; Husain-Syed, F.; Tofani, L.; Allinovi, M.; Paparella, L.; Spatafora, P.; Di Costanzo, R.; et al. Doppler-Derived Renal Functional Reserve in the Prediction of Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Robotic Surgery. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2024. [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Zhen, J.; Meng, Q.; Li, L.; Yan, J. Intrarenal Doppler Approaches in Hemodynamics: A Major Application in Critical Care. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 951307. [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, M.; Kunst, G.; Baker, E.; Weerapolchai, K.; Lumlertgul, N. Cardiac Surgery Associated AKI Prevention Strategies and Medical Treatment for CSA-AKI. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 5285. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Illustration of arterial flow measurement using Doppler pulse velocity to derive the renal resistive index.

Figure 1.

Illustration of arterial flow measurement using Doppler pulse velocity to derive the renal resistive index.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patient study selection. AKI, acute kidney injury; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit .

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patient study selection. AKI, acute kidney injury; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit .

Figure 3.

Renal Resistance Index determined before surgery (A) and at admission in Intensive Care Unit(B) in patients with no AKI or stage 1 AKI (■) and those with stage 2 or 3 AKI (■).

Figure 3.

Renal Resistance Index determined before surgery (A) and at admission in Intensive Care Unit(B) in patients with no AKI or stage 1 AKI (■) and those with stage 2 or 3 AKI (■).

Figure 4.

Prediction of postoperative stage 2 and 3 Acute Kidney Injury with Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) appears in cartouche with P value.

Figure 4.

Prediction of postoperative stage 2 and 3 Acute Kidney Injury with Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) appears in cartouche with P value.

Table 1.

Definition criteria of the RIFLE score.

Table 1.

Definition criteria of the RIFLE score.

| Stage |

Serum Creatinine ↑ or GFR ↓ |

Urine Output ↓ |

| RISK AKI -1 |

150-200% or > 25-50% |

< 0.5 ml/kg/min for 6 hours |

| Injury AKI-2 |

200-300% or > 50-75% |

< 0.5 ml/kg/min for 12 hours |

| Failure AKI-3 |

>300% or > 75% or > 4 mg/dl |

< 0.3 ml/kg/min for 24 hours or anuria > 12 hours |

| Loss |

Persistent AKI = Complete loss of renal function > 4 weeks |

| ESRD |

End-stage renal disease = Complete loss of renal function > 4 weeks |

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics. Data are expressed as number (percentage) and mean (standard deviation).

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics. Data are expressed as number (percentage) and mean (standard deviation).

| Characteristics |

All patients

N=70 |

AKI stage II-III

N=11 |

AKI stage 0-I

N=59 |

P-value |

| Age, years |

65 (11) |

72 (7) |

64 (12) |

0.045 |

| Woman |

21 (30) |

4 (36) |

17 (29) |

0.248 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2

|

25.4 (3.5) |

25.7 (3.5) |

25.3 (3.5) |

0.803 |

| Caucasian/Afro-caribbean /Other |

11/55/4 |

3/7/1 |

38/48/3 |

0.765 |

| Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

| EuroSCORE II |

5.2 (2.7) |

6.3 (2.7) |

4.7 (2.7) |

0.188 |

| Cleveland score |

2.7 (0.9) |

4.2(1.2) |

2.4 (0.7) |

0.003 |

| Hypertension, n |

45 (64.3) |

9 (81.8) |

36 (61.0) |

0.189 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n |

31 (44.3) |

6(54.5) |

25 (42.4) |

0.459 |

| Insulin-dependent |

12 (17.1) |

2(18.2) |

10 (16.9) |

0.876 |

| Non-insulin-dependent |

19 (27.1) |

4 (36.4) |

15 (25.4) |

0.343 |

| Coronary artery disease |

39 (55,7) |

7 (63.6) |

32 (54.2) |

0.567 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

7 (10.0) |

0 (0.0) |

7 (11.9) |

0.260 |

| Heart Failure |

20 (28.6) |

4 (36.4) |

16 (27.1) |

0.536 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n |

11 (15.7) |

2 (18.2) |

9 (15.3) |

0.807 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n |

14 (20.0) |

3 (27.3) |

11 (18.6) |

0.514 |

| Current smoking |

14 (20.0) |

2 (18.2) |

12 (20.3) |

0.870 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

5 (7.1) |

1 (9.1) |

4 (6.8) |

0.811 |

| Chronic alcohol consumption |

16 (22.9) |

2 (18.2) |

14 (23.7) |

0.689 |

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Beta-blockers |

45 (64.3) |

7 (63.6) |

38 (64.4) |

0.986 |

| Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin II Antagonists |

43 (61.4) |

7 (63.6) |

36 (61.0) |

0.9821 |

| Diuretics |

21 (30) |

4 (36.4) |

17 (28.8) |

0.618 |

| Statines |

39 (55.7) |

7 (63.6) |

32 (54.2) |

0.786 |

| Laboratory |

|

|

|

|

| Creatinine, mcg/ml |

95.5 (20.8) |

84.2 (124) |

97.6 (19.7) |

0.226 |

| Hematocrit,% |

38.3 (3.9) |

34.7 (3.3) |

38.9 (3.7) |

0.008 |

Table 3.

Surgical and perioperative data. Variables are presented as mean (SD), median (interquartile range) or number (percentage) as appropriate. CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; IABCP, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation; LCOS, low cardiac output syndrome.

Table 3.

Surgical and perioperative data. Variables are presented as mean (SD), median (interquartile range) or number (percentage) as appropriate. CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; IABCP, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation; LCOS, low cardiac output syndrome.

| Characteristics |

All

N=70 |

AKI stage II-III

N=11 |

AKI stage 0-I

N=59 |

P-value |

| Surgical characteristics |

|

|

|

|

| Emergency, n |

9 (12.9) |

2 (18.2) |

7 (18.2) |

0.986 |

| Re-operation, n |

3 (4.3) |

1 (9.1) |

2 (3.4) |

0.395 |

| Endocarditis, n |

3 (4.3) |

1 (9.1) |

2 (3.4) |

0.395 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery |

32 (45.5) |

5 (45.5) |

27 (45.8) |

0.985 |

| Valvular replacement/repair, n |

34 (48.6) |

6 (54.5) |

28 (47.5) |

0.876 |

| Combined surgery, n |

4 (5.7) |

0 (0.0) |

4 (6.8) |

0.377 |

| Ascending aorta, n |

3 (4.3) |

1 (9.1) |

2 (3.4) |

0.395 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Aortic clamping time, min |

94 (34) |

110 (31) |

91 (34) |

0.237 |

| CPB time, min |

142 (39) |

159 (44) |

139 (40) |

0.290 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Hemodynamics |

|

|

|

|

| Mean Arterial pressure, mmHg |

|

|

|

|

Before CPB

End of surgery |

97 (16)

80 (12) |

90 (14)

83 (11) |

99 (16)

80 (13) |

0.154

0.509 |

| Heart rate, beat/min |

|

|

|

|

Before CPB

End of surgery |

76 (16)

88 (15) |

83 (13)

94 (13) |

74 (17)

86 (15) |

0.109

0.188 |

| Central Venous Pressure, mmHg |

|

|

|

|

Before CPB

End of surgery |

7.8 (2.5)

10.6 (2.6) |

7.6 (2.9)

12.3 (1.3) |

7.8 (2.5)

10.3 (2.8) |

0.892

0.019 |

| Arterial lactate, mmole/L |

|

|

|

|

| End of surgery |

2.8 (1.0) |

3.6 (1,7) |

2.7 (0.8) |

0.183 |

| Circulatory support after CPB |

|

|

|

|

| IABCP, n |

4 (5.7) |

2 (18.2) |

2 (3.4) |

0.054 |

| Dobutamine, n |

24 (34.3) |

7 (63.6) |

17 (28.8) |

0.027 |

| Adrenaline, n |

5 (7,1) |

3 (27.3) |

2 (3.4) |

0.005 |

| Noradrenaline, n |

24 (34.3) |

5 (45.5) |

19 (32.2) |

0.398 |

| LCOS, n |

|

|

|

|

| Red blood cell transfusion |

|

|

|

|

| Patient, n |

11 (15.7) |

5 (45.5) |

6 (10.2) |

0.003 |

| Red blood cell, unit |

0 (0-4) |

1 (0-5) |

0 (0-4) |

0.111 |

Table 4.

Multivariate stepwise regression analysis for stage 2 and 3 Acute Kidney Injury. IABCP, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation.

Table 4.

Multivariate stepwise regression analysis for stage 2 and 3 Acute Kidney Injury. IABCP, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation.

| |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

P-value |

| Cleveland Score |

2.93 |

1.14-7.50 |

0.025 |

| Change in Renal Resistive Index |

1.13 |

1.02-1.25 |

0.016 |

| Need > or =2 inotropes or IABCP |

22.8 |

1.19-434.1 |

0.037 |

| Variables included |

Cleveland score, dRRI, need >2 inotropes/ABCP, hematocrit, age, creatinine clearance, transfusion |

| Variables removed |

hematocrit, age, creatinine clearance, transfusion |

| N |

70 |

| Hosmer Lemeshow |

6.819 (df=3, P=0.556) |

| Nagelkerke R2 |

0.616 |

Table 5.

Characteristics of studies testing the performance of renal resistive index (RRI) to predict Acute Kidney Injury after cardiac surgery. AKIN, acute kidney injury network; CABGS, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; dRRI, percentage change from preoperative to postoperative measure of renal resistive index; RIFLE, risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function and end-stage kidney failure; TAAD, acute type A aortic dissection; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; VR/Vr, valve replacement/valve repair.

Table 5.

Characteristics of studies testing the performance of renal resistive index (RRI) to predict Acute Kidney Injury after cardiac surgery. AKIN, acute kidney injury network; CABGS, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; dRRI, percentage change from preoperative to postoperative measure of renal resistive index; RIFLE, risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function and end-stage kidney failure; TAAD, acute type A aortic dissection; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; VR/Vr, valve replacement/valve repair.

Study

Year |

N |

Surgery |

Criteria AKI |

Prevalence AKI, % |

Mean age |

RRI measurement |

Cut-off |

AUC |

Se, % |

Sp, % |

Peillex

2020 [18] |

100 |

TAVI |

AKIN

Cystatin |

10

10 |

84 |

Preoperative

Postop day 1

Postop day 3 |

NA

0.79

NA |

NA

0.766

NA |

NA

80

NA |

NA

62

NA |

Sinning

2014 [21] |

132 |

TAVI

|

AKIN |

24.2 |

80 |

Preoperative

Postop 4h

Postop day 1-7 |

NA

0.85

NA |

NA

0.73

NA |

NA

58

NA |

NA

86

NA |

Wu

2017 [22] |

62 |

acute TAAD

|

AKIN |

65 |

47 |

Preoperative

Postop 6h

Postop day 1-3 |

NA

0.72

NA |

NA

0.918

NA |

NA

95

NA |

NA

72

NA |

| Regolisti [20] 2017 |

60 |

CABG VR/Vr |

AKIN |

38 |

69 |

Before incision

End of surgery

Postop 4h-day 1 |

NA

0.67

NA |

NA

0.710

NA |

NA

67

NA |

NA

64

NA |

| Guinot [16] 2013 |

82 |

CABG VR/Vr |

RIFLE |

26 |

72 |

Preoperative

Postop 0-2h

Postop 6h

Postop day 1 |

NA 0.73

NA

NA |

0.630

0.930

0.870

0.840 |

NA

93

NA

NA |

NA

88

NA

NA |

Bossard

2011 [15] |

65 |

CABG VR/Vr |

>30% sCreat

|

28 |

70 |

Postop 0-2h |

0.74 |

0.910 |

89 |

91 |

Hertzberg

2017 [17] |

96 |

Mixed |

AKIN |

28 |

69 |

Preoperative |

0.70 |

NA |

78 |

46 |

Quin

2017 [19] |

67 |

acute TAAD

|

AKIN |

31 |

46 |

Postop 6h |

0.72 |

0.855 |

91 |

71 |

Current study

2024 |

70 |

CABG VR/Vr |

RIFLE |

16

(AKI-2/3) |

65 |

Preoperative

Postop 0-2h

dRRI pre-post |

0.64

0.68

9.4 |

0.610

0.710

0.830 |

55

82

73 |

73

63

97 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).