1. Introduction

Societal aging is a global phenomenon, evident not only in Latvia but also in other countries worldwide, including those in Europe. For instance, South Korea, with the lowest fertility rates among OECD economies, is rapidly aging. By 2025, it is projected to become an ultra-aged society, where over 20% of the population will be 65 or older [

1]. Aging has become a serious socio-demographic problem in Latvia after the restoration of national independence in the early 1990s. The primary driver of this phenomenon is a sustained period of extremely low fertility rates, insufficient to maintain population replacement. Latvia is one of the countries where the population is aging the fastest [

2]. At the beginning of 2021, Latvia had 1,893,200 inhabitants, of which 393,698 were seniors aged 65 and over, making up 20.8% of the population. By contrast, 30 years ago in 1991, the proportion of senior citizens was nearly half as low at 11.8%, and in 2003, it had risen to 15.8%. Although Latvia's total population is decreasing, the number of elderly people is rising [

3]. As society ages, the number of people requiring social care services, both in the community and in social care institutions, is also increasing. For example, in Riga, the capital of Latvia, the number of long-term social care recipients was 2,236 in 2023, 2,196 in 2022, and 2,045 in 2021 [

4], indicating a steady rise in social care needs.

In Latvia, the Law on Social Services and Social Assistance states that only individuals whose care needs exceed what can be provided through home care, day care centers, or other community-based services are eligible for institutional social care due to the significant amount of care required. Additionally, the population's need for social care services is assessed using a standardized evaluation tool, uniformly applied across the country, and approved by government regulations. Therefore, only individuals with significant care needs are placed in social care institutions.

Many social care institutions in Latvia were built in the 1970s and 1980s as large facilities, housing between 100 and 300 clients. Today, it is recognized that high-quality social care benefits from environments that are closer to family settings. Therefore, from 2021 to 2027, funding from the European Social Fund and the Recovery and Resilience Mechanism is planned for constructing new social care facilities designed to provide a family-like environment [

5]. In Latvian social policy, the primary focus is on developing community-based social services. However, it is important to note that Latvia still has a significant legacy of institutional care, and the development of community-based services is progressing slowly [

6] This means that existing social care institutions will likely continue to play a crucial role in addressing the population's social care needs. Therefore, research is needed to explore how to enhance the quality of life within these institutions as well.

On the one hand, Latvia has specific requirements for long-term social care institutions [

7] that outline the main tasks to be performed and the conditions and amenities that must be provided to clients. Regarding service content, the requirements stipulate that social care institutions provide clients with round-the-clock supervision and individual support, assistance with self-care, maintenance or development of cognitive abilities, skill-building and movement activities, recreational activities, relaxation classes, informational and educational events, outdoor walks, and consultations with social work specialists. Additionally, social care institutions provide clients with clothing, supplies, hygiene products, and technical aids. They also ensure meals are provided at least four times a day. Government regulations set general requirements for the premises, equipment, and the ability for clients to see friends and loved ones. However, these requirements do not specify the standard of quality of life that should be ensured or how to align these requirements with the client’s personal views on quality of life.

To improve the quality of services in social care institutions, it is essential to understand clients' opinions. This ensures that, given limited resources, investments are targeted and aligned with the specific needs and preferences of the clients.

1.1. Social Care Provision and Needs Assessment System in Latvia

The social services system in Latvia is governed by the Law on Social Services and Social types: social care services, social rehabilitation services, and social work services. Additionally, the LSSSA distinguishes between two modes of provision for social care and social rehabilitation services [

8]: 1) at the individual's place of residence or nearby (also referred to as community-based or alternative social services, emphasizing their role as alternatives to institutional services), and 2) in long-term social care and rehabilitation institutions. Community-based services are characterized by the fact that clients typically do not need to change their place of residence to receive them. For example, home care services are provided directly at the client's residence, while day care centers offer services outside the residence but close by. In both cases, the client spends the night at home. However, service staff are available only during certain hours, not throughout the entire day. Institutional social services are characterized by round-the-clock staff availability and require clients to change their usual place of residence. Examples include long-term social care and social rehabilitation institutions for adults or children, social rehabilitation centers, crisis centers, and shelters [

9]. Social care services in institutions are associated with clients having greater needs for care and supervision.

In Latvia, social care services in an institution are provided only if the client's care needs exceed what can be accommodated through home care or day care services at their place of residence [

10]. According to

Section 1 and Section 18 of the LSSSA, a social care service consists of measures designed to meet the basic needs of individuals who face objective difficulties in self-care due to age or functional impairments. On the other hand, the purpose of providing social care services is to ensure that the quality of life is maintained for individuals who, due to age or functional disorders, are unable to manage it on their own. According to the LSSSA and Cabinet of Ministers regulations [

11], the municipal social service assesses residents' needs and abilities to determine the appropriate type of social care service for them.

Residents' needs for social care services are assessed according to the methodology outlined in Annexes 2 and 3 of the Cabinet of Ministers Regulation No. 138, 'Regulations on the Receipt of Social Services,' dated April 2, 2019. The decision to place a person in an institutional social care service is made based on an objective assessment of their care needs. This means that those selected for institutional care have significant and objective needs that exceed what can be provided by community-based care services. For example, in the municipality of Riga, 35 hours of home care per week is defined as the upper threshold; clients exceeding this amount are deemed eligible for placement in a social care institution [

12]. This indicates that only clients with the highest care needs are granted the right to receive services in a social care institution.

The social work specialist at the municipal social service assesses the objective nature of difficulties caused by age or functional disorders by identifying observable signs that confirm the client's limitations. They also obtain a doctor's opinion on the objective nature of these disorders. The requirement for an objective assessment ensures that the client's ability to influence the amount and nature of care provided according to their personal preferences is not a factor.

Section 4, Part 1 of the LSSSA stipulates that 'social services are provided only based on an assessment of a person's individual needs and resources by a social work specialist. Understanding this norm in conjunction with the purpose of social care services provision in the law leads to the conclusion that in Latvia, the assessment of a social work specialist is decisive. However, the client's own opinions about their needs are considered informative and only relevant if they align with objective information (such as the specialist's observations and opinions of other experts) and the established standard of basic care needs.

To determine the most suitable type of social care service for a client’s needs, the social work specialist assesses the person's physical and mental abilities and evaluates their level of care needs according to the Cabinet of Ministers' regulations. This assessment involves evaluating six specific abilities related to daily activities. The assessment involves rating each activity on a scale from '0' to '4'. A rating of '0' indicates complete dependence on others for the activity, requiring total assistance, while a rating of '4' signifies full independence in the activity, with no need for help from others. The groups of activities are: 1. Basic needs (food intake, food preparation, food procurement, performance of physiological functions); 2. Mobility (moving, dressing, mobility); 3. Self-awareness, cognitive abilities, and safety; 4. Behavior and social contacts; 5. Personal hygiene; 6. Help in the household. Assessment of the client's abilities is conducted at their place of residence under normal conditions. This includes observation and gathering information from the client and their relatives about the client's abilities and care needs. The social work specialist also considers the family doctor's instructions regarding the person's health, type of functional impairment, and written care recommendations. Based on this evaluation, the social work specialist provides a quantitative assessment that helps determine the type and duration of care required, forming the basis for deciding the most appropriate type of social care services.

Maintaining the quality of life is related to the care objective of substituting the usual activities a person was previously able to perform but can no longer manage due to age or functional disorders. Thus, the concept of quality of life within the regulatory framework should be understood in the context of the general goal of social services: enabling a person to live as independently as possible in their usual environment, maintain or regain personal responsibility for their life (principle of client self-determination), and receive help only for needs that cannot be met objectively or with the assistance of family members, society (volunteers, self-help groups, support persons), or technical aids and environmental adaptations. In the context of the goal of social services, maintaining the client's control and autonomy over their life is essential. This means that the quality of life is tied to ensuring that the support provided by social care services does not exceed what is necessary. Caregivers—both formal and informal—should not perform tasks for the client that the client can do themselves. Therefore, quality of life is not about providing as much support as possible, but about offering only the objectively necessary support. Excessive support can reduce a person's independence, which is contrary to the goal of maintaining their autonomy. It can be concluded that current regulatory enactments do not mandate that social care services must address clients' psychological needs, which are a crucial aspect of the concept of quality of life. One of the aims of this study is to highlight the importance of factors beyond direct care in enhancing the quality of life for clients receiving social care services in an institution.

1.2. Factors Influencing Quality of Life in Social Care Institutions

The concept of quality of life is broad and encompasses all aspects of life, but scientific literature has yet to reach a consensus on its exact dimensions and variety. There is also the view that, at least in the Western world, most people are familiar with the term 'quality of life' and have an intuitive understanding of what it entails [

13].

Quality of life is understood as a combination of multiple domains, including housing, health, education, income, crime, leisure, culture, and access to green spaces. Additionally, literature on quality of life distinguishes between objective and subjective aspects, recognizing the importance of individuals' satisfaction with these and other domains. These characteristics likely facilitate the interaction between scientific knowledge, measurement tools (such as indicators), and specific policy goals and interventions [

14]. However, it is clear that 'quality of life' means different things to different people and takes on various meanings depending on the context in which it is applied [

13]. This indicates that quality of life research should encompass both subjective assessments from individuals and the context and environment in which they live.

However, quality of life dimensions are generally associated with specific aspects of well-being. First, physical well-being relates to an individual's health and physical condition. Second, material well-being pertains to economic stability and access to resources. Third, interpersonal relationships involve social connections and support systems. Fourth, personal development and self-determination are concerned with the individual's ability to realize their potential and make independent decisions. Additionally, emotional well-being, social inclusion, and rights are crucial elements that contribute to the overall quality of life [

15]. It can be concluded that while the understanding of this concept varies among researchers and contexts, quality of life generally includes several essential components.

In research within a specific field, researchers often focus on a narrower aspect of quality of life. In the context of social care, assessing quality of life has a particular significance, as it pertains to individuals with substantial care needs who frequently require comprehensive and ongoing support. Thus, the perception of quality of life for these individuals is closely linked to the quality and appropriateness of the care services provided to meet their specific needs. In the context of social care services, the concept of quality of life takes on a specific meaning. It encompasses not only the individual's subjective feelings but also the objective living conditions affected by declines in physical and cognitive abilities. Additionally, it includes the care activities required to provide necessary support, which directly impacts the well-being of the clients.

Analyzing the quality of social care and quality of life separately, each concept appears distinct and understandable. Quality of life, as previously mentioned, encompasses physical well-being, material well-being, interpersonal relationships, personal development, self-determination, emotional well-being, social inclusion, and rights. In contrast, the quality of social care is assessed based on criteria such as the availability of care, professionalism, emotional support, individualized approach, and care efficiency. Each of these dimensions is crucial for a fulfilling life and overall well-being. It is evident that some aspects overlap between the concepts of quality of life and quality of social care, such as physical well-being, relationships, and self-determination, while other aspects are specific to the quality of social care. Factors determining quality of life and quality criteria for social care interact and influence each other. Each individual has unique values, standards, and life goals that affect their satisfaction with life. When entering a social care institution, where care is provided according to general standards for a specific number of clients, individuals often face challenges in adapting to new conditions.

The deterioration of functional abilities and the need to adapt to the living conditions of a social care institution often cause discomfort and difficulties. Individuals must adjust to new circumstances, which frequently involves relinquishing previous values and habits. This transition can be challenging and requires significant emotional and psychological resilience. Therefore, to effectively enhance the quality of life in a social care institution, it is essential to understand the factors influencing both quality of life and quality of social care in an integrated manner.

According to Linda S. Noelker, Ph.D., director of the Katz Policy Institute at the Benjamin Rose Institute, and Zev Harel, former professor and chair at Cleveland State University, distinguishing between 'quality of care' and 'quality of life' in social care institutions can make the challenge of measurement more manageable. This differentiation facilitates a clearer understanding and evaluation of each aspect, reflecting both the effectiveness of care delivery and the clients' life satisfaction and well-being. By focusing on specific quality aspects, targeted improvements can be made, enhancing the overall quality of life for residents of social care institutions [

16] Additionally, this approach allows for more precise identification of specific areas needing improvement, whether in health care, emotional well-being, or social support.

British researchers also emphasize that, while quality of care and quality of life are often interconnected, they are not interchangeable. A person's sense of well-being can surpass the quality of care they receive, and conversely, even with excellent care, individuals may still experience a low quality of life. In social care institutions, while quality of care is crucial, it is not the sole factor contributing to a fulfilling life. It is essential to acknowledge and respect the diverse cultural backgrounds and individual preferences of residents, including their personal and family definitions of a good quality of life [

17]. This highlights the need to examine the interrelationship between these two dimensions of quality.

In their book

Care-related Quality of Life in Old Age: Concepts, Models, and Empirical Findings, Marja Vaarama, Professor of Social Work and Social Gerontology at the University of Lapland, Richard Pieper, Professor at Bamberg University, and Andrew Sixsmith, Professor in the Department of Gerontology at Simon Fraser University, define the key criteria for quality of care. These criteria include the adequacy of care, continuity of care, and the professional competence and skills of care workers. Adequacy of care means that care must align with the client's individual needs and preferences to ensure the highest possible quality of life. Continuity of care ensures that clients receive consistent and stable support, which is crucial for their well-being. Professional competence and skills of care workers are essential to delivering care to the highest standards and quality [

18].

According to the findings of the aforementioned authors, certain aspects of social care quality extend beyond direct care activities and their outcomes. For instance, the quality of interaction between clients and care workers is crucial, as a positive relationship fosters trust and satisfaction with care, which enhances clients' subjective well-being and indirectly supports care workers' effectiveness. Additionally, client autonomy and control are vital for maintaining dignity and independence during care. Safety within the home is another critical factor, ensuring clients' physical well-being and sense of security. Healthcare, nursing, and social care outcomes are objective criteria that measure the effectiveness and quality of care. In contrast, satisfaction with care is a subjective indicator that reflects clients' personal experiences and opinions about the services received. Observing and applying both objective and subjective criteria in practice is essential for ensuring high-quality care services and enhancing clients' quality of life [

18].

To improve the satisfaction of individual needs and quality of life in institutional care, it is crucial to focus on preserving each client's identity and uniqueness. According to M. Vaarama, R. Pieper, and A. Sixsmith, factors such as gender, ethnicity, and cultural values play a key role in maintaining this identity. A living environment that caters to subjective needs, including the presence of personal items in the care facility, and addresses social-emotional, cultural, and organizational contexts, can greatly enhance a client's quality of life. Ensuring that this environment is customized to the individual needs and personal lifestyle of clients is also essential [

18].

From the above, it is clear that addressing the issue of quality of life and quality of care is complex, as it fundamentally shapes how care quality is conceived, ensured, evaluated, and regulated in social care institutions. Ensuring quality of life in such settings requires specific conditions and is influenced by clients' physical conditions and care needs. It is important to recognize that the clients' understanding of quality of life is significantly impacted by these factors.

Jennifer L. Johs-Artisensi, a professor in the Department of Management and Marketing at the University of Wisconsin and an associate professor at Bellarmine University, along with Kevin E. Hansen, Chief of the Department of Health and Aging Services Management, offer a valuable perspective on addressing the interrelationship between quality of life and quality of social care in institutional settings. In their recently published book, "

Quality of Life and Well-Being for Residents in Long-Term Care Communities: Perspectives on Policies and Practices" [

19], Jennifer L. Johs-Artisensi and Kevin E. Hansen identify key factors that long-term social care recipients recognize as impacting their quality of life within social care institutions. The factors influencing the quality of life identified by the authors are: 1) autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose; 2) relationships; 3) activities; 4) food and meals; 5) environment; and 6) quality of care. According to their classification, quality of care is just one of the factors contributing to the overall quality of life in a social care institution. This approach appears to bridge the gap between quality of life and quality of care by integrating both concepts within the context of long-term social care institutions.

Similar findings from research involving residents, families, and staff in care homes reveal that critical factors contributing to quality of life include security—to feel safe; belonging—to feel part of the community; continuity—to experience links and connections; purpose—to have goals to aspire to; achievement—to make progress towards these goals; and significance—to feel that you matter as a person. And these same factors apply not only to clients but also to staff [

17]. Employees must also feel safe, valued, and a sense of belonging, as this influences their relationship with clients and the quality of care they provide. Consequently, this impacts the quality of life of clients living in a social care institution. There are authors who acknowledge that residents' self-assessed quality of life is related to quality-of-care indicators, noting that changes in the quality of care provided can significantly affect their overall quality of life [

19]. Consequently, in evaluating the quality of life in a social care institution, the self-assessment of clients is essential. This approach ensures that the evaluation captures the clients' personal perspectives and priorities, reflecting their subjective experience and satisfaction with their living conditions and care.

One of the models of quality of life is the Patient-Preference Model, which differs from other models by explicitly incorporating weights that reflect the importance patients place on specific dimensions of their life. This model involves comparing different states and dimensions to establish a ranking based on their value or the patients' preferences for one state over another [

13]. Some authors argue that subjective methods are preferred over objective methods, particularly for planning and policy purposes, because they provide more valuable feedback and allow individuals to express their dissatisfaction with existing conditions. Subjective indicators offer critical insights into personal experiences and perceptions, which are essential for addressing community-based issues through a bottom-up approach. This perspective emphasizes the importance of capturing personal feedback to make informed improvements and adaptations in social care settings [

14].

The aim of this study is to convert the feedback obtained from clients into actionable proposals for enhancing the services provided by social care institutions. This research focuses on the Riga Municipality Social Care Center "Gailezers" and aims to extend the findings to similar social care institutions. Therefore, this research strategy is deemed the most suitable for planning the development and improvement of social services.

This means that evaluating the quality of life in a social care institution must prioritize client feedback to ensure a client-centered approach in enhancing the services. To achieve this, it is crucial to implement evaluation methods that provide clients with physical and cognitive support, such as clarifying questions before they choose a response. The authors of the study, who conducted self-assessments with long-term care clients, acknowledge that all participants required assistance, often of a more intensive nature, to maintain orientation, focus, comprehension, and to complete the questionnaire [

20]. Therefore, the structured interview method was also employed in this study. In this approach, questions were asked and, if needed, explained by employees of the social care institution who are not directly involved in performing care tasks.

2. Materials and methods

The research base is the Riga Social Care Center "Gailezers" (hereinafter - Center), which provides long-term social care services in a social care institution.

A total of 328 clients are receiving services at the Center. Due to limitations in the chosen research strategy and method, not all clients' opinions could be gathered, as the assessment required certain cognitive and physical abilities, including the ability to articulate feelings and opinions. During the research, 95 clients were interviewed using the structured interview method. Clients with dementia or signs of dementia, those with severe functional impairments who were sedentary, clients with hearing and speech impairments, those in the hospital, clients who were absent, and those who refused to participate were not included in the interviews.

A structured interview was conducted using a checklist of interview and observation questions adapted from Jennifer L. Johs-Artisensi and Kevin E. Hansen [

19]. This checklist was specifically designed for assessing six key domains of quality of life for clients residing in a long-term care facility. The interview questions were organized into six groups based on the factors determining the quality of life in a social care institution, as identified by these authors: 1) autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose; 2) relationships; 3) activities; 4) environment; 5) food and meals; and 6) quality of care.

2.1. Statistical Data Analysis

To assess quality of life factors, a Likert-type scale was employed in the questionnaire. Respondents indicated their level of agreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Composite scores were calculated by summing item responses within each factor, as well as all factors together (overall composite score). This resulting sum score was utilized as the dependent variable in subsequent statistical analyses to test the statistical hypothesis where independent variables were age, time spend in the Center, language of daily interaction, education, relatives and number of people in a room.

The data distribution was assessed by inspection of the normal Q-Q plot and with the Shapiro-Wilk test. For normally distributed data, mean values and standard deviations were reported. In contrast, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize non-normally distributed data. Nominal data were described by frequencies and percentages.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare composite scores between language of daily interaction and relatives. The Kruskal – Wallis H test was used to compare composite scores between number of people in the room and education levels. To test the association between age, time spent in the Center and composite scores of life factors, the Spearman’s rank correlation was used.

The linear regression analysis was conducted to test whether age, time spent in the Center, language of daily interaction, education, relatives, and number of people in the room are related to overall composite scores. To build the regression model, stepwise forward and backward regression methods were used. To select the best model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and adjusted R2 were used.

Statistical data analysis was performed with Jamovi (v.2.3). The results were considered statistically significant when the p value was < 0.05.

3. Results

The analysis revealed several significant findings that shed light on the assessment of factors influencing the quality of life in a social care institution, according to the clients' opinions.

Table 1 provides parameters according to which clients were analysed.

Approximately half of the respondents were Latvian speakers, while the other half primarily used Russian in their daily conversations. The average age of the interviewees was 75.5 years. Two-thirds of the clients had either secondary or technical secondary education, two-thirds lived in a room alone, while 26% of the clients shared their living space with a roommate.

The results of Cronbach’s alfa (overall = 0.95) indicate a strong internal consistency among the questions (

Table 2). This suggests that the modified interview questionnaire is effectively designed for use alongside the Likert scale, ensuring reliable measurement of client responses. However, when examining the assessment of different quality of life factors individually, the Cronbach’s alfa for the "Environment" factor falls below the threshold of 0.7.

The recalculated Likert scale ratings reveal that clients rate the "Relationship" factor the highest, while the "Environment" factor receives the lowest rating in the social care institution where they reside.

The customer ratings do not differ statistically significantly between those who have or do not have relatives (p > 0.05), nor between different levels of education (p > 0.05). No difference was observed in s length of stay in the Center (p > 0.05). The researchers found this result particularly surprising, especially regarding clients with and without relatives. There is a common perception among social care staff that clients with relatives tend to be more critical of living conditions in social care institutions. The survey results do not support this perception. However, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was found in the evaluations based on everyday language for criteria such as Autonomy, respect and sense of purpose, Relationships, and Quality of care (see

Table 3). Russian speakers rated these criteria higher than Latvian speakers. Judging by the effect size coefficient, the differences in the indicators for Autonomy, Respect and Sense of Purpose, Relationships, and Quality of Care are moderately large, with the coefficient ranging between 0.2 and 0.5. However, for the quality-of-life factors related to Activities, Environment, and Food and Meals, there are no significant differences between the evaluations of Latvian-speaking and Russian-speaking clients (p > 0.05).

In general, the overall difference indicates that there is a significant variation in quality-of-life assessments based on the client's language (p = 0.017, effect size = 0.5). On average, Latvian-speaking clients rate their overall quality of life lower (overall score = 170 ± 27.6) compared to those who use Russian (overall score = 183 ± 23.6) in their daily lives. Latvian speakers also exhibit a higher standard deviation in their assessments compared to Russian speakers. This indicates that Latvian speakers have more varied opinions, with a broader range of responses, whereas Russian speakers' opinions are more consistent and less extreme.

Table 4 shows data on the differences in ratings based on whether a client lives alone or shares a room with others. The p-value is below 0.05 for the Environment factor, Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose and Overall assessment. Clients living with roommates tend to rate the Environment factor, Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose and Overall quality of life lower than those living alone. This suggests that increased room occupancy is associated with more critical assessments of the environment, Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose and overall quality of life in the social care institution.

The final linear regression model was significant F(2,92) = 7.86, p < 0.001, adj R2 = 0.13, indicating approximately 13% of the variance in overall composite score is explained by the language of daily interaction and number of people in the room. Language significantly predicted overall composite score (β = 12.6, t = 2.50, p = 0.014). Russian speakers scored, on average, 12.6 points higher on the overall composite score than Latvian speakers (95% CI [2.6 - 22.7]). People in the room significantly predicted overall composite score (β = 15.7, t = 3.05, p = 0.003). People living alone in a room scored, on average, 15.7 points higher on the overall composite score than those who lived in a room with roommates (95% CI [5.5 – 25.9]).

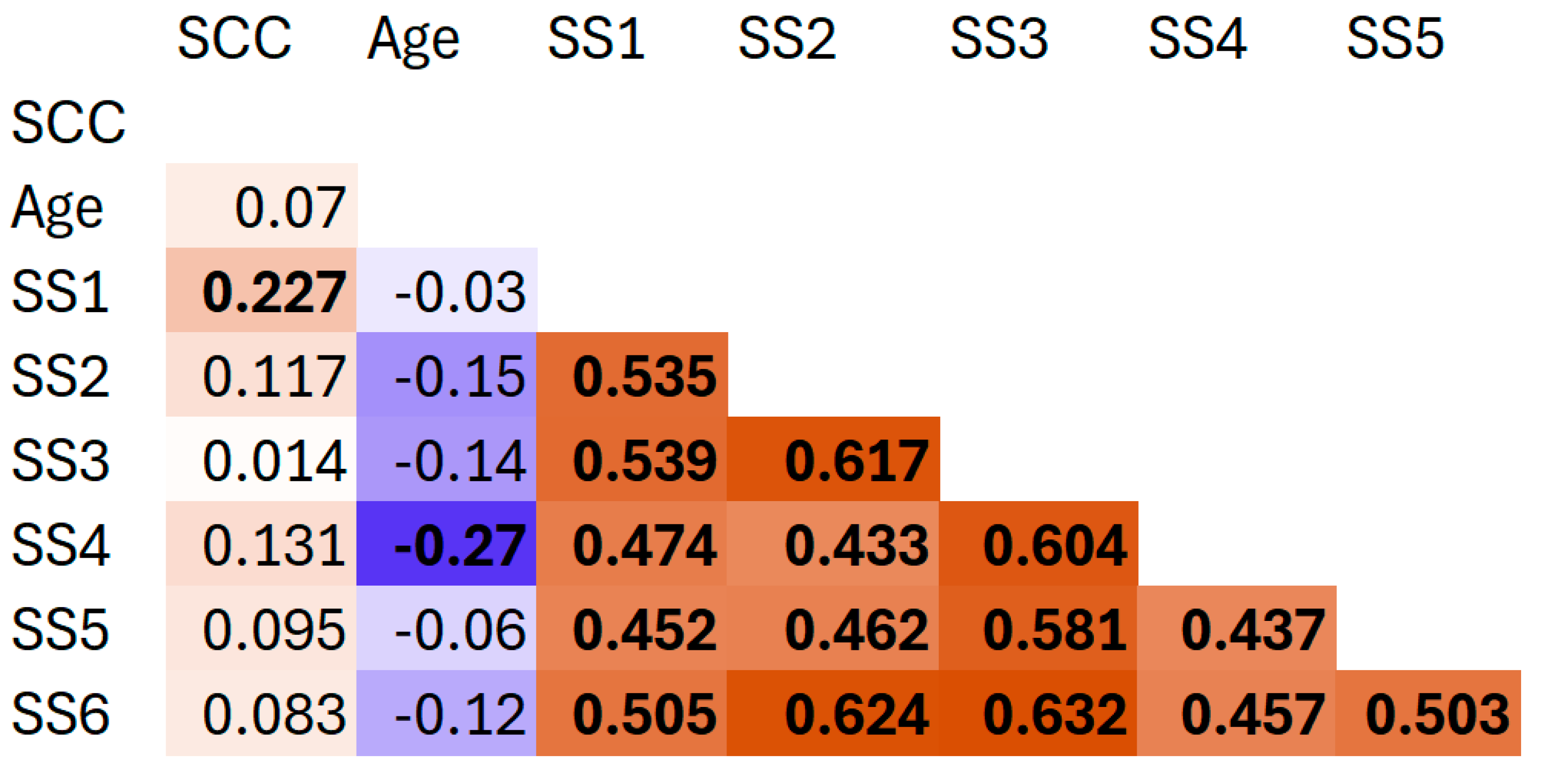

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix of quality-of-life factors and clients age and time spend in social care institution. Note: bold numbers indicate statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05); SSC - time spend in the social care center; SS1 - Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose; SS2 – Relationships; SS3 - Activities; SS4 – Environment; SS5 – Food and meals; SS6 - Quality of care.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix of quality-of-life factors and clients age and time spend in social care institution. Note: bold numbers indicate statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05); SSC - time spend in the social care center; SS1 - Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose; SS2 – Relationships; SS3 - Activities; SS4 – Environment; SS5 – Food and meals; SS6 - Quality of care.

The analysis shows that the more time a client spends in the Center, the higher the rating given to the Autonomy factor (rs = 0.227). Conversely, age correlates negatively with the Environment factor, meaning that older clients tend to rate the environment of the Center lower (rs = -0.270), indicating that the environment of the Center may be less suitable for the oldest clients.

The strongest correlations were found between SS2 – Relationships and SS3 – Activities (rs = 0.617), SS2 – Relationships and SS6 – Quality of care (rs = 0.624), SS3 – Activities and SS4 – Environment (rs = 0.604), and SS3 – Activities and SS6 – Quality of care (rs = 0.632).

Clients and employees of the Center were asked to rank the six key factors of quality of life, as identified by Jennifer L. Johs-Artisensi and Kevin E. Hansen [

19], in order of importance. The most crucial factor was assigned the number "1," while the least crucial was assigned the number "6." The results of this ranking are presented in

Table 5.

The results indicate that the ratings given by clients and employees are nearly identical. The primary distinction is that clients prioritize Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose as the most crucial factor affecting their quality of life in the social care institution, with Quality of care as the second most important factor. In contrast, employees rank Quality of care as the top priority, followed by Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose. Both clients and employees rank Relationships as third, Food and meals as fourth, and Environment as fifth, with Activities being considered of relatively lower priority. Consequently, Autonomy and Quality of care emerge as the most crucial factors for maintaining quality of life in a social care institution.

In addition to the overall statistical results, the researchers focused on identifying the specific individual questions from the structured interview that received the most critical evaluations from the clients. The purpose was to identify precisely which measures should be taken to address the most critically evaluated specific issues related to quality-of-life factors.

The lowest customer rating was given to question 4.4: "How often can you leave the facility on Center resident outings (excursions, etc.)?" This question was part of the Environmental factor group. The average rating given by customers was "3," indicating that outings occur "Sometimes (about 3 times a year)." The interquartile range was from 1 to 5, reflecting considerable variability in the responses. A similar situation was observed in question 5.2, which asked, "Do you feel that you have some choice about what food to eat at each meal?" This question, part of the Food and meals factor, received the second-lowest rating, indicating that clients felt they had limited choice regarding their meals. The third-lowest rating was given to question 6.2, "Do you think carers like their jobs?" which was part of the Quality of care factor. The lower rating for question 6.2 suggests that clients may perceive a lack of enthusiasm or job satisfaction among carers, which could impact their overall perception of the quality of care provided. This highlights the need for further investigation into staff morale and its effects on client satisfaction.

4. Discussion

Several key insights have emerged from the analysis of the clients' feedback, underscoring areas for improvement within the institution.

The findings that clients rate the "Relationship" factor highest and the "Environment" factor lowest in the social care institution suggest a clear distinction between the perceived importance of social connections and physical surroundings in shaping overall well-being. Additionally, data about evaluation of different quality of life factors environment evaluation shows the differences in ratings based on whether a client lives alone or shares a room with others. Clients living with roommates tend to rate the Environment factor, Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose and Overall quality of life lower than those living alone. This suggests that increased room occupancy is associated with more critical assessments of the environment, Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose and overall quality of life in the social care institution.

This is consistent with the results of another study conducted in Latvia in 2016 - researchers from the University of Latvia conducted a study in which the opinion of experts was ascertained through semi-structured interviews. During the interview, the social rehabilitator pointed out that the main challenge in long-term social care institutions is ability to provide elderly with single rooms in long-term institutions. Another issue that was highlighted was the size of the rooms, which should be bigger giving more space for its residents [

21]. This indicates that the environmental factor is one of those that should be given priority attention when improving the service of a social care institution.

The results also show a negative correlation between age and the Environment factor, indicating that older clients tend to rate the Center's environment lower, suggesting it may be less suitable for them. As age increases, clients' perceptions of the environment become more negative, implying that older clients may find the surroundings less accommodating or comfortable. This suggests that environmental factors play an increasingly significant role in the quality of life for older clients in social care institutions. Therefore, the appropriateness, comfort, aesthetics, and accessibility of the environment should be specifically assessed and tailored to meet the needs of older clients.

The client ratings show no statistically significant differences between those with or without relatives. This result was unexpected, especially regarding the presence of relatives, as it is commonly assumed by social care staff that clients with family connections are more likely to be critical of living conditions in social care institutions. However, the survey data do not support this assumption.

It is recommended that the Center's administration investigate the factors contributing to the more critical evaluations of Latvian-speaking clients and explore strategies to reduce room occupancy. A statistically significant difference was identified in the assessments of autonomy, respect and sense of purpose, relationships, and quality of care based on clients' everyday language, with Russian-speaking clients consistently rating these factors higher than Latvian speakers. This disparity suggests the need to examine potential underlying causes. Latvian speakers reported a lower overall quality of life, highlighting the importance of targeted interventions to address their specific concerns. Further research is necessary to explore whether these differences stem from cultural, psychological, staff communication practices, or other factors, to better understand and address the issue.

Discussion about what should be done to improve quality of life of clients of social care institution that cannot renovate, refurbish, or rearrange environment to be modern, family like and correspond to up-to-date understanding of decent care environment definitely should take into account correlations between different quality of life factors according to clients’ opinion. If, as noted, the environment is rated most critically by clients, then based on the correlations presented in the Results section, it can be assumed that expanding the range of activities could positively influence clients' perceptions of the Center's environment or help mitigate its shortcomings. Similarly, enhancing relationships could encourage greater participation in activities and improve clients' perceptions of the quality of care. Such insights provide a valuable direction for improving the content of the social care institution. This approach is particularly crucial in post-Soviet buildings, where physical environment improvements are often limited; thus, compensating for these limitations through content and relational enhancements becomes a viable strategy. It can also be inferred that improving clients' perception of the quality of care can be achieved by enhancing the quality of relationships, both among clients and between clients and caregivers. This provides the Center's administration with evidence-based guidance on where to focus their efforts for the most effective solutions. Such findings are particularly valuable in the context of limited resources.

Some client responses highlight issues that require immediate attention in the social care institution's service offerings, as indicated by the questions that received the most critical feedback. Clients' most critical comments suggested that their quality of life would improve with more opportunities to go outside the institution, even minor influence over meal content, and greater enthusiasm and engagement from caregivers in their work.

The attitudes of care staff and potential improvements are reflected in the assessments of clients and employees regarding the priority of various quality-of-life factors within the social care institution. Although the difference in opinions between clients and employees is not essential —clients prioritize autonomy, respect, and a sense of purpose as the most crucial factors affecting their quality of life, with quality of care ranked second—employees rank quality of care as their top priority, followed by autonomy, respect, and a sense of purpose. This suggests that, in situations where employees must choose between ensuring a client's autonomy and providing care, they may prioritize care activities over respecting the client's autonomy. It also underscores the significance of social policy in transitioning towards a service model that resembles a family environment, where small group settings and a focus on individualized care play crucial roles. It is evident that the Center's culture and the perspectives of both clients and employees are relatively aligned concerning what is most critical for ensuring quality of life in a social care institution. This consensus indicates that the organizational environment and culture support collective improvement, as there is substantial agreement between clients and care workers on the priority and relative importance of various quality of life factors within the institution. However, this also suggests that employees should receive training on the importance of Autonomy, respect, and sense of purpose, and learn how to enhance clients' opportunities to exercise these aspects.

5. Conclusions

The findings reveal that clients prioritize "Relationships" over the "Environment" when assessing their quality of life in social care institutions, highlighting a critical area for improvement. Additionally, room sharing correlates with more negative evaluations of autonomy, respect, sense of purpose, and overall quality of life, while older clients increasingly perceive the environment as less accommodating. The significant impact of room occupancy on quality of life, where clients living alone rated their overall experience more positively, suggests that privacy and personal space are critical determinants of well-being. The social care institution should consider strategies to increase the availability of single rooms or enhance shared living conditions, as reducing room occupancy could substantially improve client satisfaction with both the environment and their overall experience. The social care institution should prioritize environmental adaptations that cater to the older population to improve their quality of life and mitigate the dissatisfaction associated with aging in a care facility.

The absence of statistically significant differences in quality of life assessments based on clients’ relationships with relatives or their educational backgrounds challenges preconceived notions among social care staff. This outcome suggests that having relatives does not inherently lead to more critical assessments of living conditions, and thus, the focus should be on universally improving care standards, rather than assuming family presence influences client satisfaction.

The research findings indicate a significant disparity in quality of life assessments between Latvian-speaking and Russian-speaking clients, with the former consistently rating autonomy, respect, sense of purpose, relationships, and quality of care lower. This suggests an urgent need for the Center's administration to investigate the underlying factors contributing to these critical evaluations among Latvian-speaking clients and to consider strategies for reducing room occupancy. Targeted interventions should be developed to address the specific concerns of Latvian speakers, and further research is essential to explore the cultural, psychological, and communication factors that may influence these differences.

The research underscores the need to enhance clients' quality of life in social care institutions, especially in scenarios where physical renovations are not possible. Since clients critically assess the environment, enhancing the range of available activities may mitigate some of the shortcomings of the physical infrastructure. Moreover, improving relationships among clients and between clients and caregivers could foster greater engagement in activities, thereby improving overall perceptions of care. This finding indicates that a holistic approach—incorporating both relational and activity-based interventions—can compensate for environmental limitations and improve client well-being, particularly in post-Soviet buildings with limited potential for physical upgrades. Ultimately, focusing on these aspects provides the social care institution administration with evidence-based guidance to effectively address clients' needs within existing resource constraints.

Incorporating client preferences and feedback into service enhancements is crucial for fostering a more supportive and responsive care environment. The research findings reveal that clients highlight the need for immediate attention to address critical feedback regarding the social care institution's offerings. Specifically, clients express a desire for improved quality of life through increased opportunities for outdoor activities, greater input on meal content, and enhanced enthusiasm and engagement from caregivers. These findings suggest that relatively simple changes in care routines and staff attitudes could have a significant positive impact. By addressing these specific client concerns, the institution can improve satisfaction levels and foster a more supportive, client-centered care environment.

In conclusion, the findings reveal a noteworthy alignment between clients and care staff regarding the prioritization of quality-of-life factors within the social care institution, particularly emphasizing the importance of autonomy, respect, and a sense of purpose. While clients view these factors as crucial and employees prioritize quality of care, there is significant potential for improvement through staff training that balances care provision with the respect for client autonomy. This consensus highlights the need for a cultural shift within the organization towards a more family-like service model, promoting individualized care and small group settings to enhance the overall quality of life for clients.

Overall, this study provides clear evidence of the factors most significantly impacting the quality of life in social care institutions. Addressing the key issues identified—such as improving the environment, reducing room occupancy, and promoting autonomy—can lead to substantial improvements in client well-being. The findings offer valuable guidance for policymakers and administrators seeking to optimize care delivery in resource-limited settings, emphasizing the need for both infrastructural and relational improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.and M.M.; Methodology, M.M.; Formal Analysis, M.Z., A.B. and M.M.; Investigation, A.B.; Data Curation, A.B., M.M. and M.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.B, M.M. and M.Z..; Writing and Editing, A.B., M.M. and M.Z.; Project Administration, M.M. Funding Acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research receivedno external funding.

References

- Lee, H.-C.; Repkine, A. Determinants of Health Status and Life Satisfaction among Older South Koreans. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1124; Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111124 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Osis, J. Demogrāfiskās tendences un pieprasījums pēc aprūpes – izaicinājumi un risinājumi. Sociālais darbs Latvijā. [Demographic Trends and Demand for Care - Challenges and Solutions. Social Work in Latvia], 2024/2; pp.8-20.

- Report on the implementation of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing and its Regional Implementation Strategy (MIPAA/RIS) in Latvia 2018-2022, 2022; Available online: https://www.lm.gov.lv/lv/sabiedribas-novecosanas (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ilgstošās sociālās aprūpes un sociālās rehabilitācija pakalpojumi institūcijā. Sociālā sistēma un veselības aprūpe 2023. gadā; Rīgas valstspilsētas pašvaldības Labklājības departamenta gadagrāmata. [Long-term social care and social rehabilitation services in the institution. Social system and healthcare in 2023]; Riga State City local Government Welfare Department yearbook; Available online: http://ld.riga.lv/lv/par-departamentu/par-mums/labklajibas-departamenta-gadagramatas/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ģimeniskai Videi Pietuvināti Aprūpes Pakalpojumi Pensijas Vecuma Personām. Labklājības Ministrija. [Care services close to the family environment for persons of retirement age. Ministry of Welfare] 2024; Available online: https://www.lm.gov.lv/lv/gimeniskai-videi-pietuvinati-aprupes-pakalpojumi-pensijas-vecuma-personām (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ministru kabineta 2021. gada 28. aprīļa rīkojums Nr. 292. Par Latvijas Atveseļošanas un noturības mehānisma plānu 1004.punkts. [Cabinet Order No. 292 of 28 April 2021. On the Plan of the Latvian Recovery and Resilience Facility, Paragraph 1004]; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/322858 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ministru kabineta 2017. gada 13. jūnija noteikumi Nr. 338. Prasības sociālo pakalpojumu sniedzējiem. [Cabinet Regulation No. 338 of 13 June 2017. Requirements for Social Service Providers]; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/291788 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Sociālo pakalpojumu un sociālās palīdzības likums, 22.pants. [Law on Social Services and Social Assistance, Article 22]; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/68488-law-on-social-services-and-social-assistance (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Moors, M. Jaunu sociālo pakalpojumu attīstīšana. Sociālais Darbs Latvijā; Labklājības ministrija. [Development of new social services. Social work in Latvia; Ministry of Welfare], 2016/2; pp.41-45, Available online: https://www.lm.gov.lv/lv/media/7555/download?attachment (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Sociālo pakalpojumu un sociālās palīdzības likums, 28. pants; [Law on Social Services and Social Assistance, Article 28], Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/68488#p28 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ministru kabineta 2019. gada 2. aprīļa noteikumi Nr. 138. Noteikumi par sociālo pakalpojumu saņemšanu. [Regulations of the Cabinet of Ministers No. 138 of April 2, 2019. Regulations on the Receipt of Social Services], Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/305995 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Rīgas domes 2020. gada 6. marta saistošie noteikumi Nr. 3. Rīgas valstspilsētas pašvaldības sniegto sociālo pakalpojumu saņemšanas un samaksas kārtība 23. punkts. [Riga City Council Binding Regulation No. 3 of 6 March 2020. Procedures for The Receipt and Payment of Social Services Provided by the Riga State City Municipality, Paragraph 23], Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/313649#p23 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Fayers, P. M.; Machin, D. Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes, 2end ed.; Fayers, P. M., Machian D.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2007; p.4 (544).

- Martínez-Martín, J. A.; Mikkelsen, C. A.; Phillips, R. Handbook of Quality of life and Sustainability: Springer: 2021; (550).

- Kristapsone, S. Dzīves kvalitāte. Nacionālā enciklopēdija. [Quality of life. National Encyclopedia], Available online: https://enciklopedija.lv/skirklis/61290-dz%C4%ABves-kvalit%C4%81te- (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Linda, S.; Noelke Z.Harel. Linking quality of Long-Term Care and Quality of Life: Springer publishing Company, Inc. New York, NY, USA, 2000; p.164 (296).

- Tolson, D.; Dewar, B.; Jackson, G. A. Quality of Life and Care in the Nursing Home. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2014, 15(3); pp. 154–157, Available online https://doi-org.db.rsu.lv/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.023.

- Vaarama, M.; Pieper, R.; Sixsmith A. Care-related quality of life in old age concepts, models and empirical findings: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p.115, New York, NY, USA, 2008; (338).

- Johs-Artisensi, J. L.; Hansen, K. E. Quality of life and well-being for residents in long-term care communities: Perspectives on policies and practices: Springer International Publishing Springer. 2022, (195).

- Phillipson, L.; Towers, A.; Caiels, J.; Smith, L. Supporting the involvement of older adults with complex needs in evaluation of outcomes in long-term care at home programmes. Health Expectations 2022, 25(4); pp. 1453–1463. [CrossRef]

- Rezgale – Straidoma, E.; Rasnača, L. Long-term elderly care: quality assurance challenges for local governments. Research for Rural Development 2016, Annual 22nd International Scientific Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 18-20 May 2016. pp.203-209, Available online: https://llufb.llu.lv/conference/Research-for-Rural-evelopment/2016/LatviaResRuralDev_22nd_vol2.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).