Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

2.2. ANI and dDDH

2.3. PHB Genes Detection and Class Designation of PhaCs

3. Results

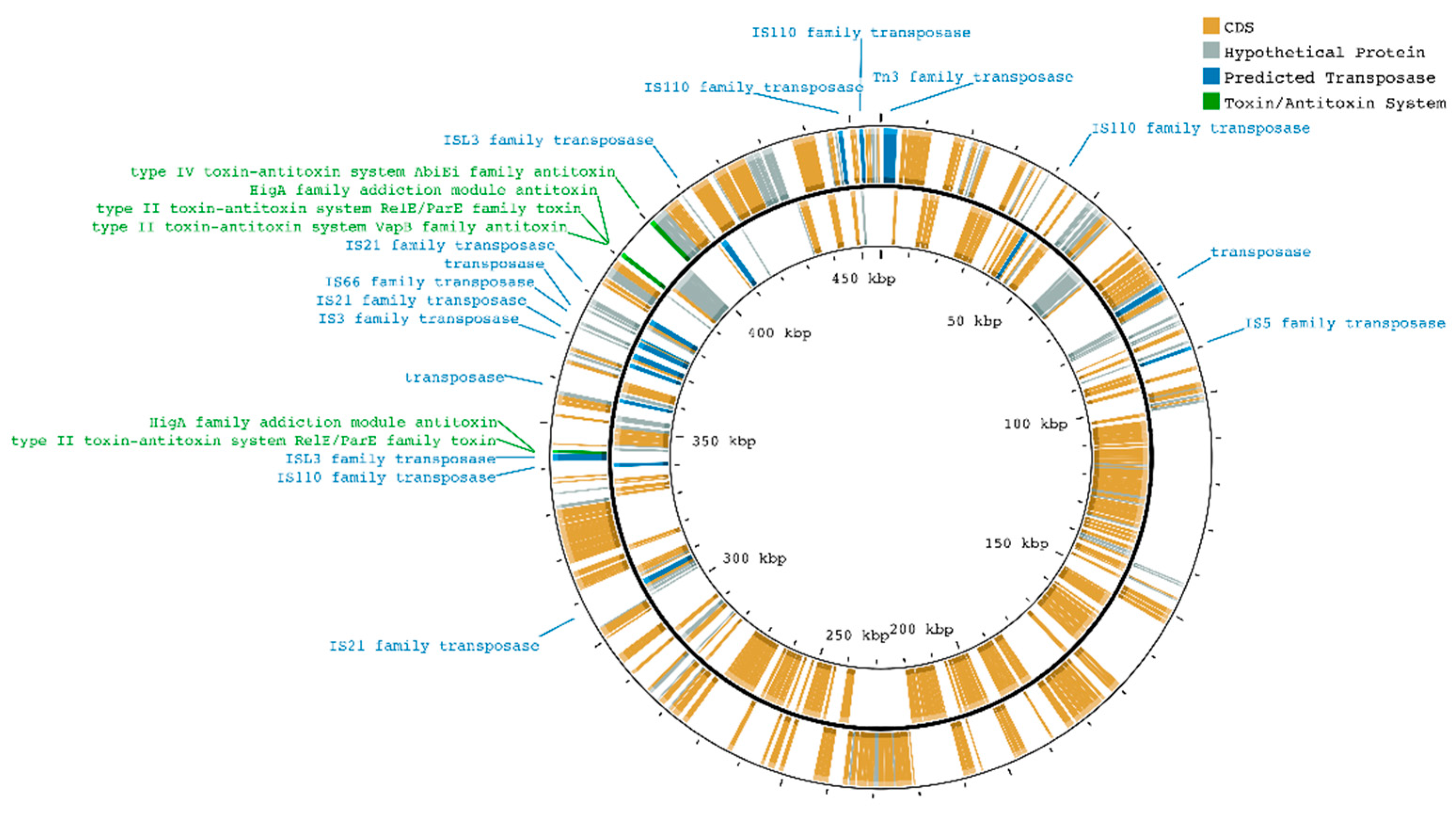

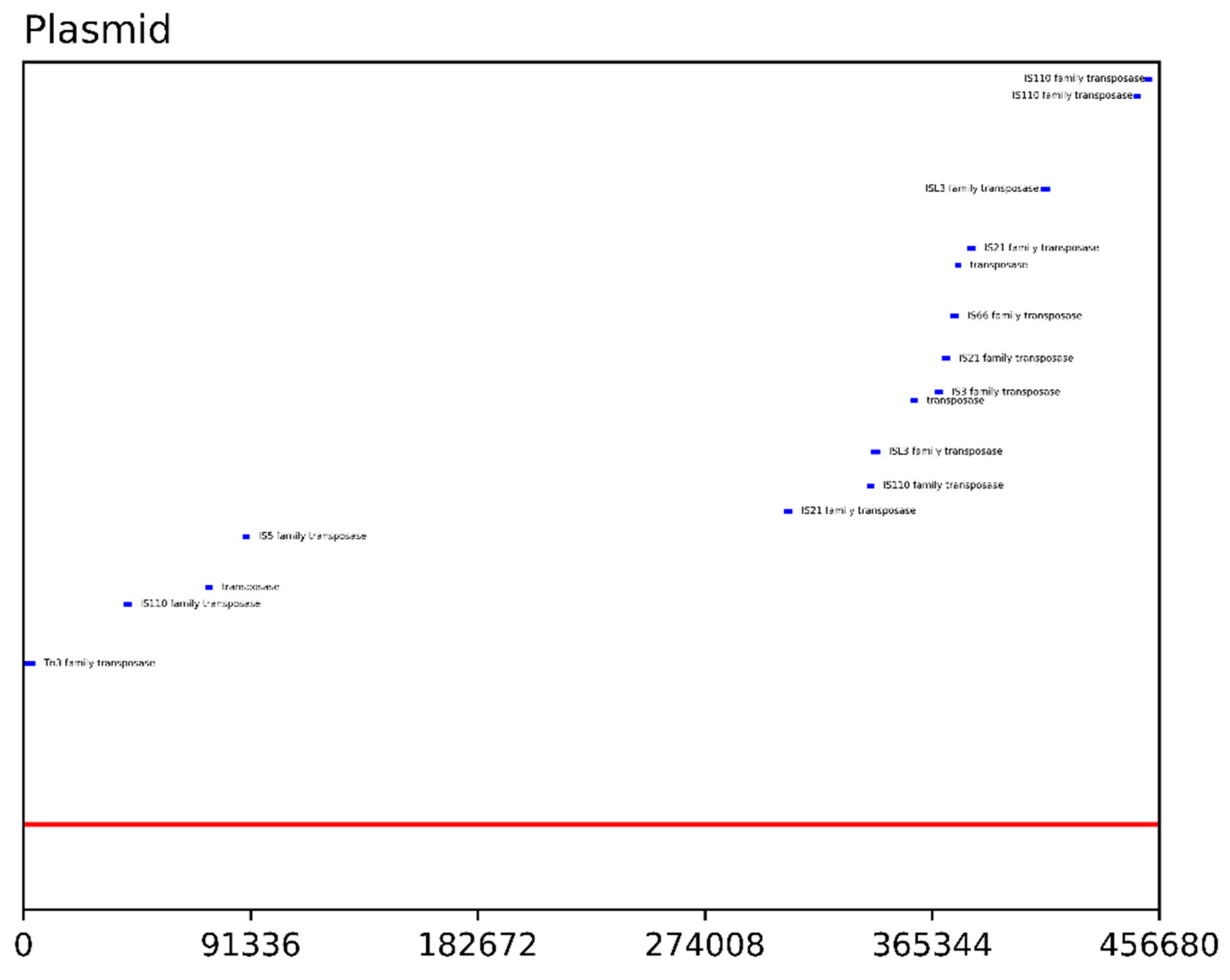

3.1. Genome Assembly of A. lata H1

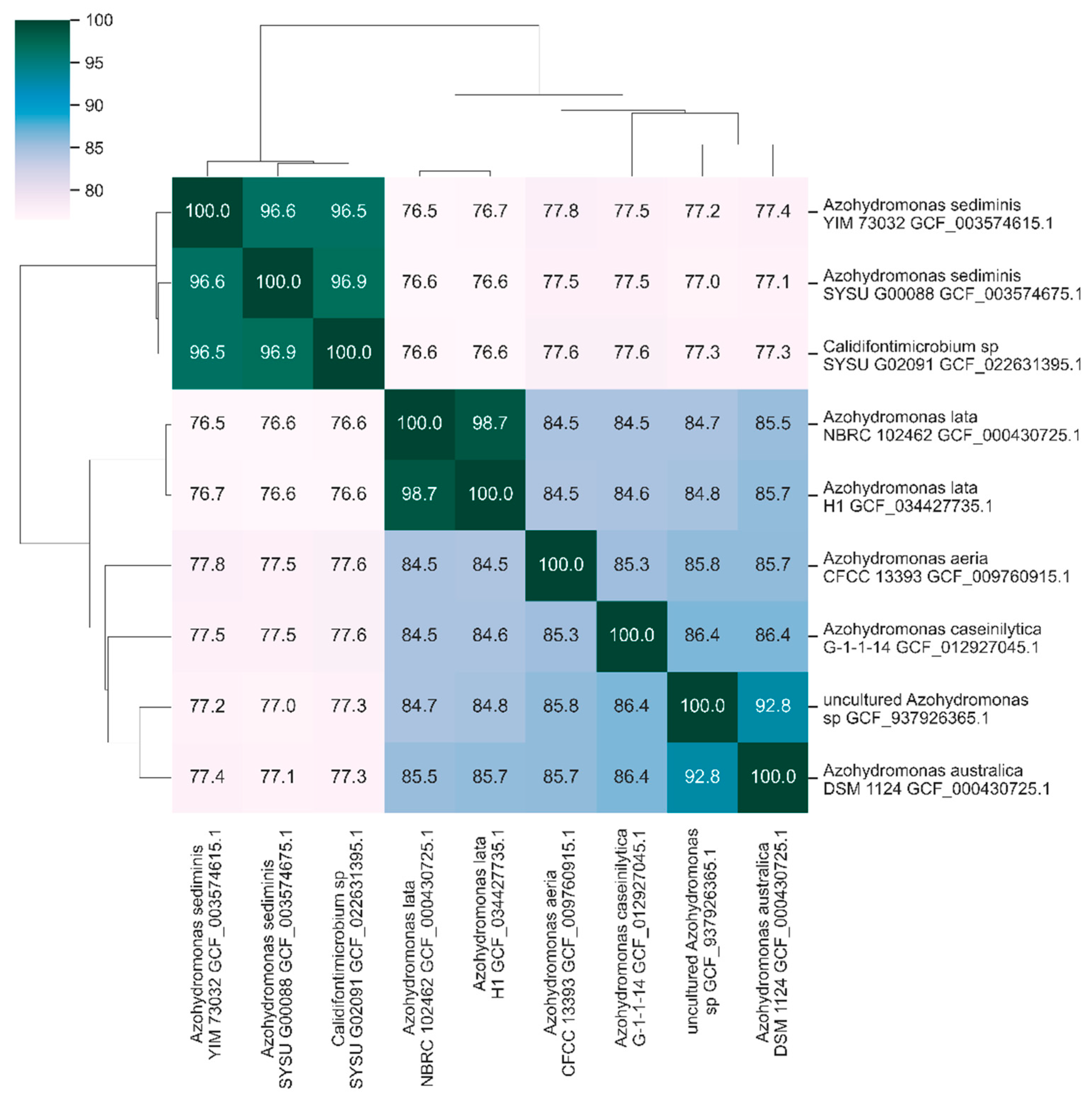

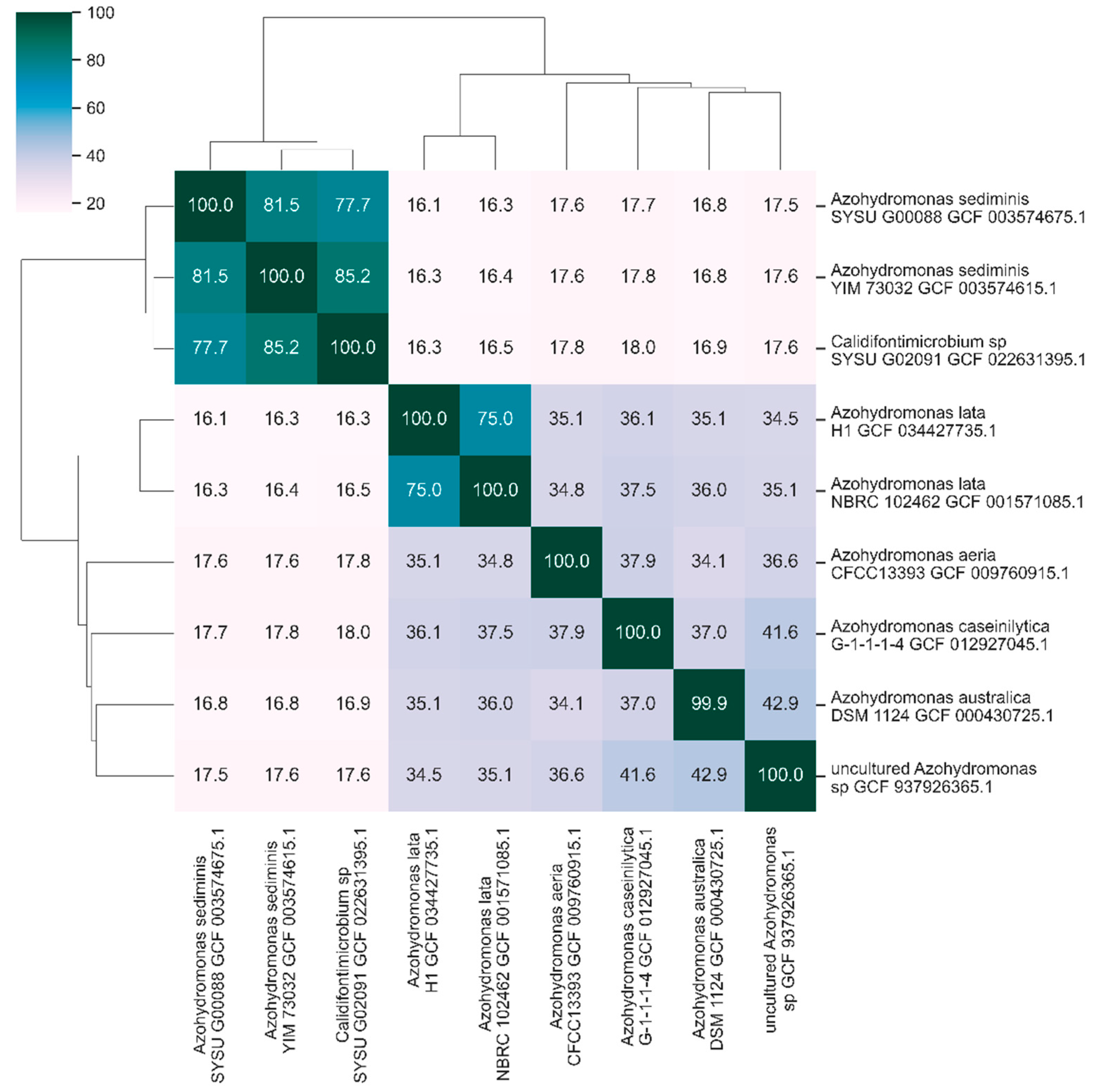

3.2. Nucleotide Identity Levels in the Genus Azohydromonas

3.3. CRISPR-Cas Systems

3.4. Resistance Proteins

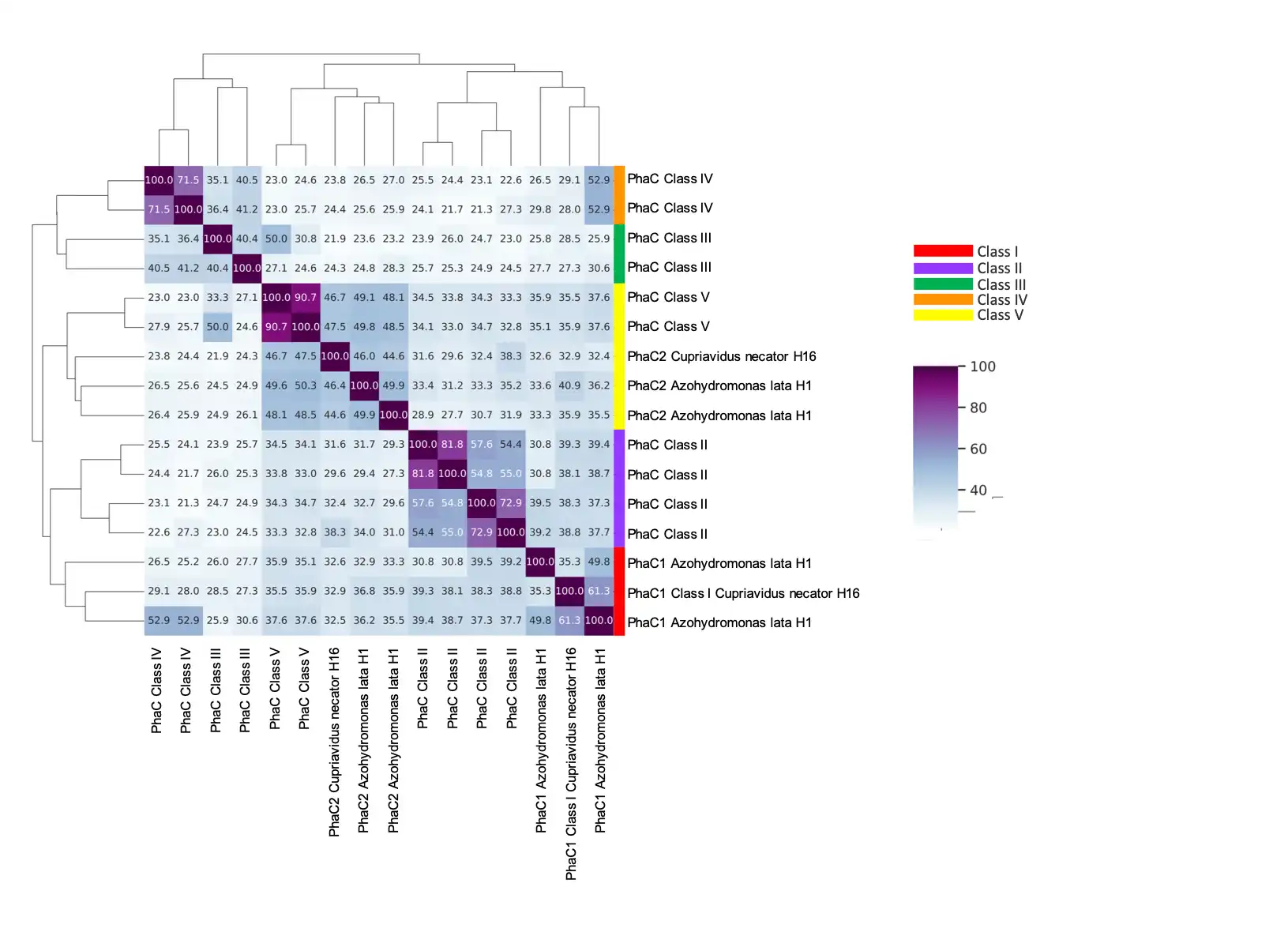

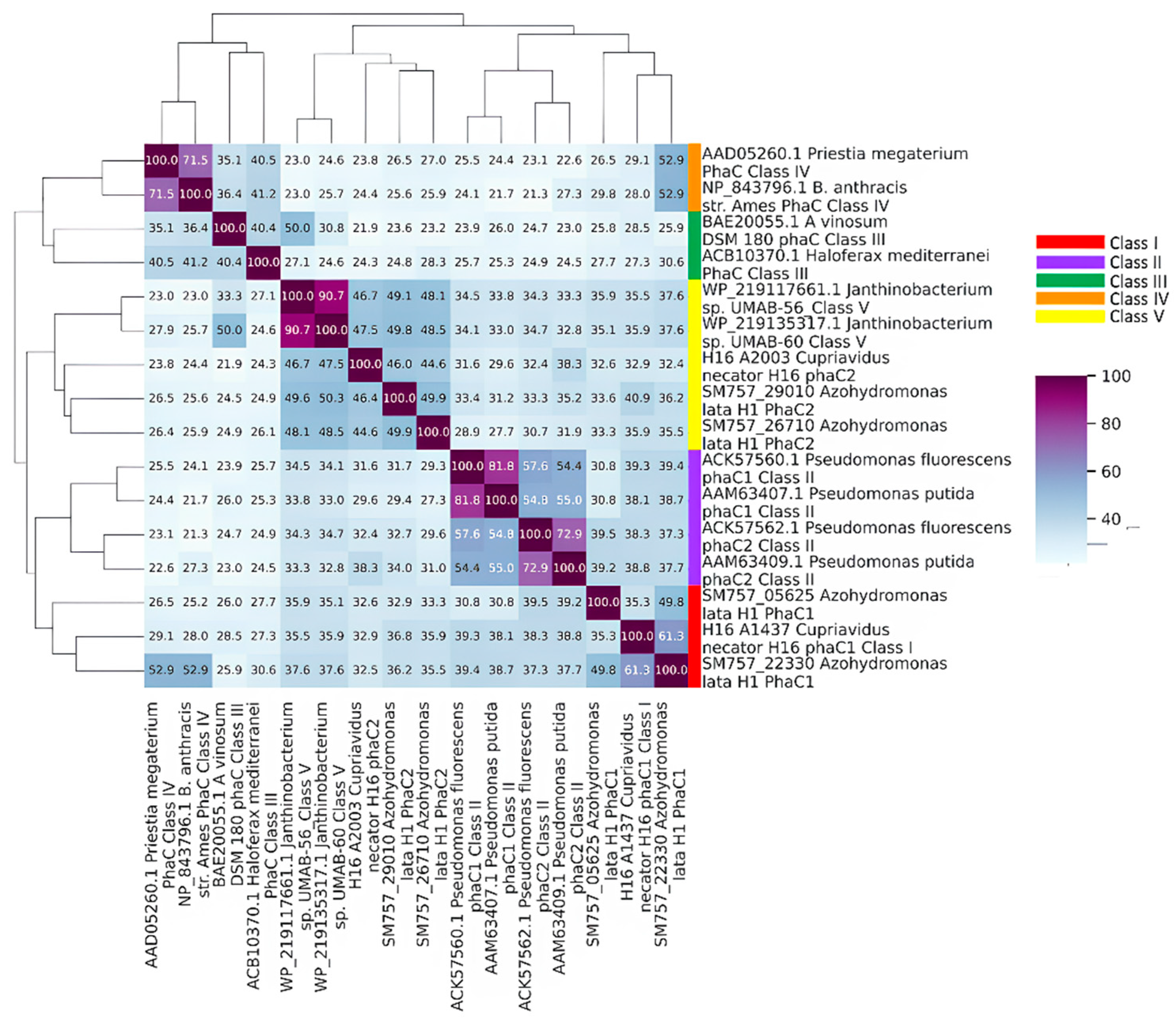

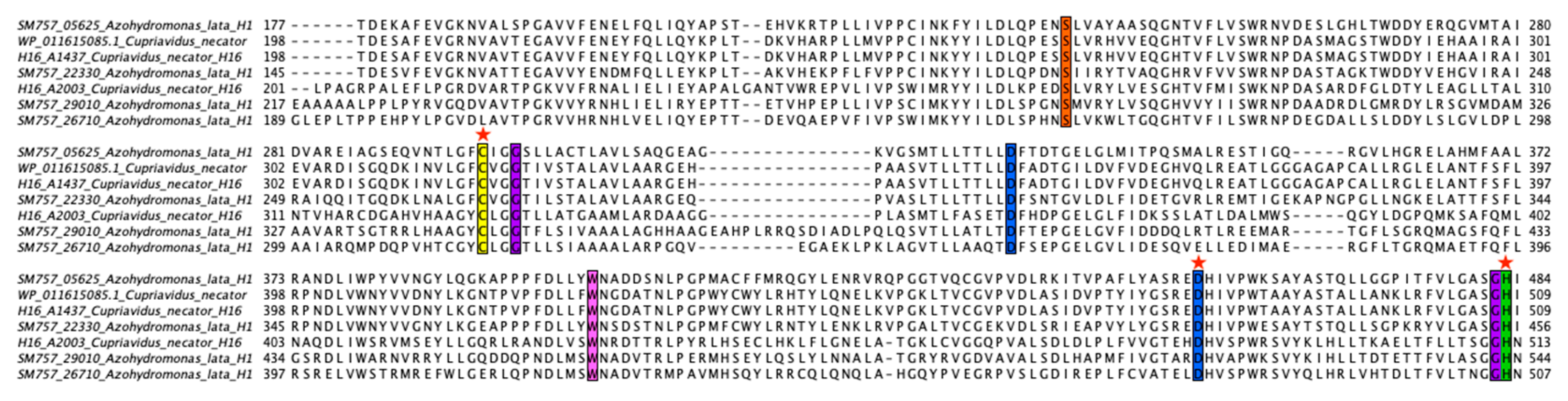

3.5. Annotation of PHB Related Genes

3.6. PhaCAB and Auxiliary Genes in the Azohydromonas Genus

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Priyadarshini, R.; Palanisami, T.; Pugazhendi, A.; Gnanamani, A.; Parthiba Karthikeyan, O. Editorial: Plastic to Bioplastic (P2BP): A Green Technology for Circular Bioeconomy. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 851045, . [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Newman, P. Plastics: are they part of the zero-waste agenda or the toxic-waste agenda? Sustainable Earth 2021, 4, . [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, P.; Bhave, M.; Webb, H.K. Solving the plastic dilemma: the fungal and bacterial biodegradability of polyurethanes. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 39, 122, . [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Dhiman, M.; Kansal, A.; Subudhi, S.P. Plastic waste management for sustainable environment: techniques and approaches. Waste Dispos Sustain Energy 2023, 1-18, . [CrossRef]

- Rosenboom, J.G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 7, 117-137, . [CrossRef]

- Madison, L.L.; Huisman, G.W. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1999, 63, 21-53, . [CrossRef]

- Obruca, S.; Dvorak, P.; Sedlacek, P.; Koller, M.; Sedlar, K.; Pernicova, I.; Safranek, D. Polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis by halophiles and thermophiles: towards sustainable production of microbial bioplastics. Biotechnol Adv 2022, 58, 107906, . [CrossRef]

- Obruca, S.; Sedlacek, P.; Slaninova, E.; Fritz, I.; Daffert, C.; Meixner, K.; Sedrlova, Z.; Koller, M. Novel unexpected functions of PHA granules. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 4795-4810, . [CrossRef]

- McAdam, B.; Brennan Fournet, M.; McDonald, P.; Mojicevic, M. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and Factors Impacting Its Chemical and Mechanical Characteristics. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Pena, C.; Castillo, T.; Garcia, A.; Millan, M.; Segura, D. Biotechnological strategies to improve production of microbial poly-(3-hydroxybutyrate): a review of recent research work. Microb Biotechnol 2014, 7, 278-293, . [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, F.; Steinbuchel, A. Ralstonia eutropha strain H16 as model organism for PHA metabolism and for biotechnological production of technically interesting biopolymers. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2009, 16, 91-108, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sharma-Shivappa, R.R.; Olson, J.W.; Khan, S.A. Upstream process optimization of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by Alcaligenes latus using two-stage batch and fed-batch fermentation strategies. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2012, 35, 1591-1602, . [CrossRef]

- Rehm, B.H. Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics. Biochem J 2003, 376, 15-33, . [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.K.P.; Foong, C.P.; Tan, H.T.; Lim, H.; Zain, N.A.; Tan, Y.C.; Hoh, C.C.; Sudesh, K. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase genes and PHA-associated gene clusters in Pseudomonas spp. and Janthinobacterium spp. isolated from Antarctica. J Biotechnol 2020, 313, 18-28, . [CrossRef]

- Brigham, C.J.; Reimer, E.N.; Rha, C.; Sinskey, A.J. Examination of PHB Depolymerases in Ralstonia eutropha: Further Elucidation of the Roles of Enzymes in PHB Homeostasis. AMB Express 2012, 2, 26, . [CrossRef]

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Marsch, R.; Perez-Guevara, F. Investigation on the Evolutionary Relation of Diverse Polyhydroxyalkanoate Gene Clusters in Betaproteobacteria. Journal of molecular evolution 2018, 86, 470-483, . [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wei, H.; Liu, X.; Yao, Z.; Xu, M.; Wei, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.Q. Structural Insights on PHA Binding Protein PhaP from Aeromonas hydrophila. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 39424, . [CrossRef]

- Little, G.T.; Ehsaan, M.; Arenas-Lopez, C.; Jawed, K.; Winzer, K.; Kovacs, K.; Minton, N.P. Complete Genome Sequence of Cupriavidus necator H16 (DSM 428). Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8, . [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, A.; Fricke, W.F.; Reinecke, F.; Kusian, B.; Liesegang, H.; Cramm, R.; Eitinger, T.; Ewering, C.; Potter, M.; Schwartz, E.; et al. Genome sequence of the bioplastic-producing “Knallgas” bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16. Nat Biotechnol 2006, 24, 1257-1262, . [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.; Houmiel, K.L.; Tran, M.; Mitsky, T.A.; Taylor, N.B.; Padgette, S.R.; Gruys, K.J. Multiple beta-ketothiolases mediate poly(beta-hydroxyalkanoate) copolymer synthesis in Ralstonia eutropha. J Bacteriol 1998, 180, 1979-1987, . [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.I.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, K. Cloning of the Alcaligenes latus polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis genes and use of these genes for enhanced production of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998, 64, 4897-4903, . [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114-2120, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kobert, K.; Flouri, T.; Stamatakis, A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 614-620, . [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of computational biology: a journal of computational molecular cell biology 2012, 19, 455-477, . [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6614-6624, . [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, W20-25, . [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Neron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W246-W251, . [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W484-W492, . [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Goker, M. TYGS and LPSN: a database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D801-D807, . [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Soding, J.; et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular systems biology 2011, 7, 539, . [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189-1191, . [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Iredell, J.R. The higBA-Type Toxin-Antitoxin System in IncC Plasmids Is a Mobilizable Ciprofloxacin-Inducible System. mSphere 2021, 6, e0042421, . [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhai, Y.; Wei, M.; Zheng, C.; Jiao, X. Toxin-antitoxin systems: Classification, biological roles, and applications. Microbiological research 2022, 264, 127159, . [CrossRef]

- Boss, L.; Gorniak, M.; Lewanczyk, A.; Morcinek-Orlowska, J.; Baranska, S.; Szalewska-Palasz, A. Identification of Three Type II Toxin-Antitoxin Systems in Model Bacterial Plant Pathogen Dickeya dadantii 3937. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, . [CrossRef]

- Hampton, H.G.; Jackson, S.A.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Vogel, A.I.M.; Dy, R.L.; Blower, T.R.; Fineran, P.C. AbiEi Binds Cooperatively to the Type IV abiE Toxin-Antitoxin Operator Via a Positively-Charged Surface and Causes DNA Bending and Negative Autoregulation. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 1141-1156, . [CrossRef]

- Mogro, E.G.; Cafiero, J.H.; Lozano, M.J.; Draghi, W.O. The phylogeny of the genus Azohydromonas supports its transfer to the family Comamonadaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2022, 72, . [CrossRef]

- Barco, R.A.; Garrity, G.M.; Scott, J.J.; Amend, J.P.; Nealson, K.H.; Emerson, D. A Genus Definition for Bacteria and Archaea Based on a Standard Genome Relatedness Index. mBio 2020, 11, . [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rossello-Mora, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 19126-19131, . [CrossRef]

- Devi, V.; Harjai, K.; Chhibber, S. CRISPR-Cas systems: role in cellular processes beyond adaptive immunity. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2022, 67, 837-850, . [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.H.; Ng, L.M.; Neoh, S.Z.; Kajitani, R.; Itoh, T.; Kajiwara, S.; Sudesh, K. Complete genome sequence of Aquitalea pelogenes USM4 (JCM19919), a polyhydroxyalkanoate producer. Arch Microbiol 2023, 205, 66, . [CrossRef]

- Zain, N.A.; Ng, L.M.; Foong, C.P.; Tai, Y.T.; Nanthini, J.; Sudesh, K. Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Producer, Jeongeupia sp. USM3 (JCM 19920) and Characterization of Its PHA Synthases. Curr Microbiol 2020, 77, 500-508, . [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.H.; Yokota, A. Reclassification of Alcaligenes latus strains IAM 12599T and IAM 12664 and Pseudomonas saccharophila as Azohydromonas lata gen. nov., comb. nov., Azohydromonas australica sp. nov. and Pelomonas saccharophila gen. nov., comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005, 55, 2419-2425, . [CrossRef]

| Feature | Chromosome(s) | Megaplasmid |

|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 7328099 | 456680 |

| G+C ratio (%) | 68.7 | 65.6 |

| Percentage coding | 88.24 | 81.41 |

| tRNA | 56 | 0 |

| rRNA 5S, 16S, 23S | 1, 3, 2 | 0 |

| Transposases | 33 | 16 |

| Total number of CDSs | 6537 | 408 |

| No. of CDSs with assigned function | 5633 | 300 |

| CDSs with unknown function | 904 | 108 |

| Transposase Family | Chromosome(s) | Plasmid |

|---|---|---|

| Tn3 | 2 | 1 |

| IS110 | 1 | 4 |

| transposase | 11 | 3 |

| IS5 | 1 | 1 |

| IS21 | 1 | 3 |

| ISL3 | 3 | 2 |

| IS3 | 1 | 1 |

| IS66 | 6 | 1 |

| IS630 | 7 | 0 |

| Locus Tag | Product |

|---|---|

| SM757_01580* | type II TA system RelE/ParE toxin |

| SM757_01585* | HigA addiction module antitoxin |

| SM757_01810** | type II TA system VapB antitoxin |

| SM757_01815** | type II TA system RelE/ParE toxin |

| SM757_01820** | HigA addiction module antitoxin |

| SM757_01845 | type IV TA system AbiEi antitoxin |

| * System II-A | |

| **System II-B | |

| Locus Tag | Accession of contig | Product |

|---|---|---|

| SM757_03450 | JAXOJX010000003.1 | chromate resistance protein |

| SM757_03465 | JAXOJX010000003.1 | chromate resistance protein |

| SM757_03785 | JAXOJX010000003.1 | cobalt-zinc-cadmium resistance protein |

| SM757_03940 | JAXOJX010000003.1 | ArsI/CadI family heavy metal resistance metalloenzyme |

| SM757_05070 | JAXOJX010000004.1 | chromate resistance protein |

| SM757_05525 | JAXOJX010000005.1 | TerB tellurite resistance protein |

| SM757_12920 | JAXOJX010000019.1 | glyoxalase/bleomycin resistance/dioxygenase protein |

| SM757_19280 | JAXOJX010000033.1 | TerB tellurite resistance protein |

| SM757_22515 | JAXOJX010000042.1 | organic hydroperoxide resistance protein |

| SM757_24300 | JAXOJX010000049.1 | TerB tellurite resistance protein |

| SM757_24860 | JAXOJX010000051.1 | TerB tellurite resistance protein |

|

ALH1 locus tag |

ORF length | CONTIG | ALH1 predicted function | ORTHOLOGOUS | ||

| Locus tag | Gene(s) | function | ||||

| SM757_22330 | 1611 | JAXOJX010000042* | class I poly(R)-hydroxyalkanoic acid synthase | H16_A1437 | phaC1 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) polymerase |

| SM757_05625 | 1752 | JAXOJX010000005 | class I poly(R)-hydroxyalkanoic acid synthase | H16_A1437 | phaC1 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) polymerase |

| SM757_29010 | 1884 | JAXOJX010000076 | poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate polymerase N-terminal domain-containing protein | H16_A2003 | phaC2 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) polymerase |

| SM757_26710 | 1767 | JAXOJX010000060 | alpha/beta fold hydrolase | H16_A2003 | phaC2 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) polymerase |

| SM757_22335 | 1179 | JAXOJX010000042* | acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_28485 | 1185 | JAXOJX010000072 | beta-ketothiolase BktB | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_00745 | 1185 | JAXOJX010000001 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_27765 | 1209 | JAXOJX010000067 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_19820 | 1179 | JAXOJX010000035 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_22610 | 1185 | JAXOJX010000043 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_24435 | 1215 | JAXOJX010000049 | 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_07035 | 1206 | JAXOJX010000007 | 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_09505 | 1206 | JAXOJX010000012 | 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_09155 | 1206 | JAXOJX010000011 | 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_01140 | 1176 | JAXOJX010000001 | thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_31645 | 1206 | JAXOJX010000098 | 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_19540 | 1203 | JAXOJX010000034 | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | H16_A1438 | phaA | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| SM757_22340 | 738 | JAXOJX010000042* | acetoacetyl-CoA reductase | H16_A1439; H16_A2002; H16_A2171 | phaB1; phaB2; phaB3 | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase |

| SM757_08215 | 750 | JAXOJX010000009 | 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase FabG | H16_A1439; H16_A2002; H16_A2171 | phaB1; phaB2; phaB3 | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase |

| SM757_31855 | 741 | JAXOJX010000100 | 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase FabG | H16_A1439; H16_A2002; H16_A2171 | phaB1; phaB2; phaB3 | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase |

| SM757_23050 | 747 | JAXOJX010000044 | 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase FabG | H16_A2002; H16_A2171 | phaB2; phaB3 | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase |

| SM757_08600 | 1344 | JAXOJX010000010 | polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase | H16_A1150; H16_A2862; H16_B0339; H16_B1014 | phaZ1; phaZ2; phaZ3; phaZ5 | intracellular poly(3-hydroxybutyrate |

| SM757_15980 | 1002 | JAXOJX010000025 | PHB depolymerase family esterase | H16_B2401 | phaZ7 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymeras |

| SM757_26695 | 2253 | JAXOJX010000060 | 3-hydroxybutyrate oligomer hydrolase protein | H16_A2251 | phaY1 | D-(-)-3-hydroxybutyrate hydrolase |

| SM757_23895 | 870 | JAXOJX010000047 | alpha/beta hydrolase | H16_A1335 | phaY2 | D-(-)-3-hydroxybutyrate hydrolase |

| SM757_26850 | 558 | JAXOJX010000062 | phasin family protein | H16_A1381 | phaP1 | Phasin (PHA-granule associated protein) |

| SM757_25825 | 594 | JAXOJX010000056 | polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis repressor PhaR | H16_A1440 | phaR | transcriptional regulator |

| Genus or Species (strain) | Identity (%) | Alignment length | Mismatches | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| australica (DMS1124) | 100.000 | 1611 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Uncultured Azohydromonas sp. | 94.727 | 1612 | 83 | 0.0 |

| aeria (CFCC 13393) | 91.646 | 1616 | 128 | 0.0 |

| lata (NBRC102462) | 90.627 | 1611 | 151 | 0.0 |

| lata (H1) | 90.503 | 1611 | 153 | 0.0 |

| caseinilytica (G-1-1-1-4) | 90.526 | 1615 | 145 | 0.0 |

| sediminis (SYSU G00080) | 80.455 | 1627 | 280 | 0.0 |

| Calidifontimicrobium sp (SYSU G02091) | 80.086 | 1627 | 286 | 0.0 |

| Genus or Species (strain) | Identity (%) | Alignment length | Mismatches | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| australica (DMS1124) | 100.00 | 337 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Uncultured Azohydromonas sp. | 96.777 | 1179 | 38 | 0.0 |

| caseinilytica (G-1-1-1-4) | 96.438 | 1179 | 42 | 0.0 |

| lata (NBRC 102462) | 92.881 | 1180 | 82 | 0.0 |

| lata (H1) | 92.373 | 1180 | 88 | 0.0 |

| sediminis (YIM 73032) | 84.338 | 1187 | 170 | 0.0 |

| sediminis (SYSU G00080) | 84.233 | 1186 | 173 | 0.0 |

| Calidifontimicrobium sp (SYSU G02091) | 83.825 | 1187 | 176 | 0.0 |

| aeria (CFCC 13393) | 80.086 | 128 | 16 | 0 |

| Genus or Species (strain; accession) | Identity (%) | Alignment length | Mismatches | E-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| caseinilytica (G-1-1-1-4) | 94.851 | 738 | 38 | 0.0 | ||

| aeria (CFCC13393; WP_157271469.1_7046) | 94,580 | 738 | 40 | 0.0 | ||

| australica (DSM 1124) | 94,309 | 738 | 42 | 0.0 | ||

| aeria (CFCC13393; WP_157272394.1_2294) | 94,038 | 738 | 44 | 0.0 | ||

| lata (H1) | 93.496 | 738 | 48 | 0.0 | ||

| lata (NBRC 102462) | 93.360 | 738 | 49 | 0.0 | ||

| Calidifontimicrobium sp (SYSU G02091) | 84.409 | 744 | 104 | 0.0 | ||

| sediminis (SYSU G00080) | 84.430 | 745 | 102 | 0.0 | ||

| sediminis (YIM 73032) | 84.161 | 745 | 104 | 0.0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).