Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. System Model

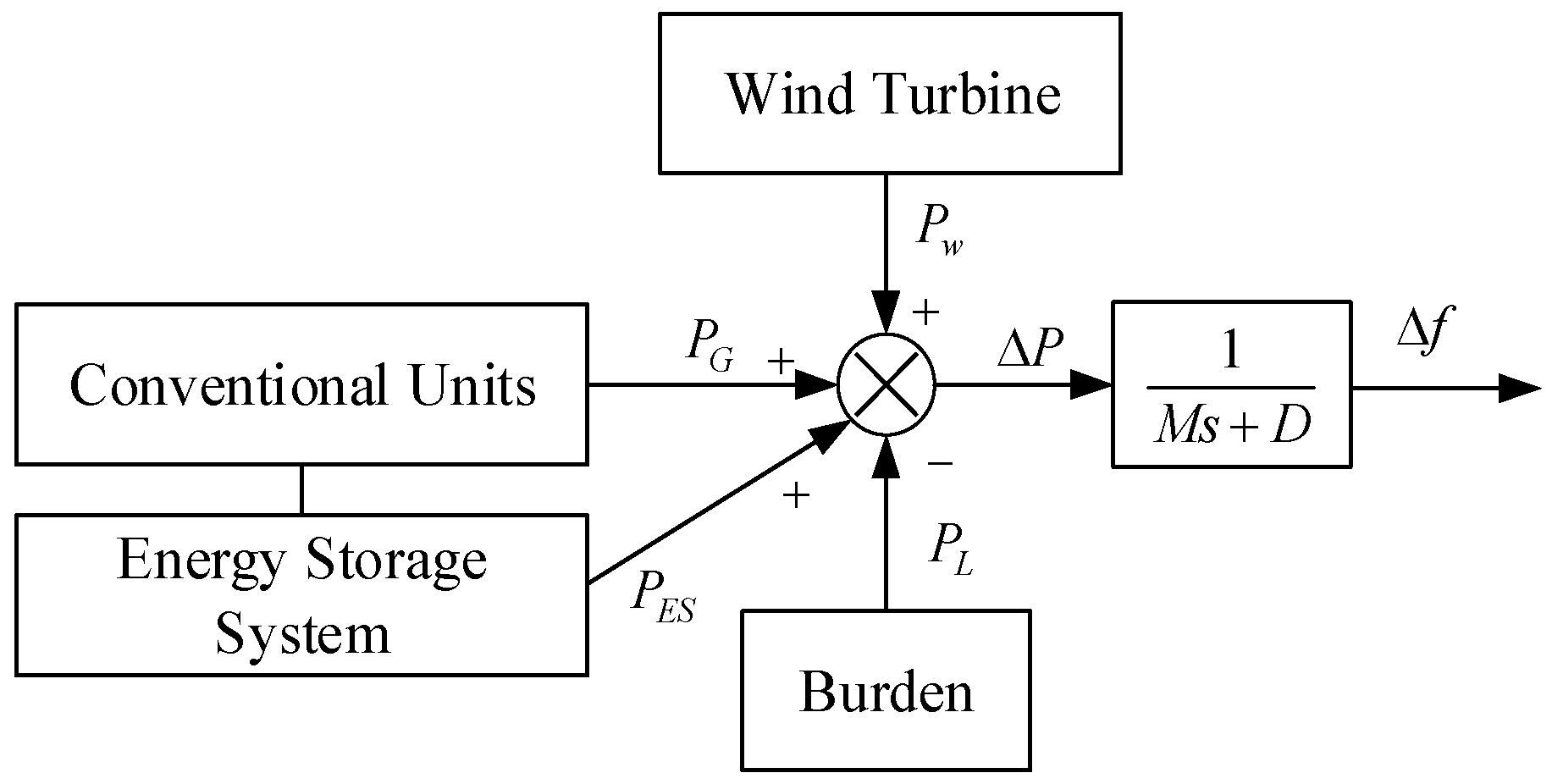

2.1. SystemFrequency Behaviour Model

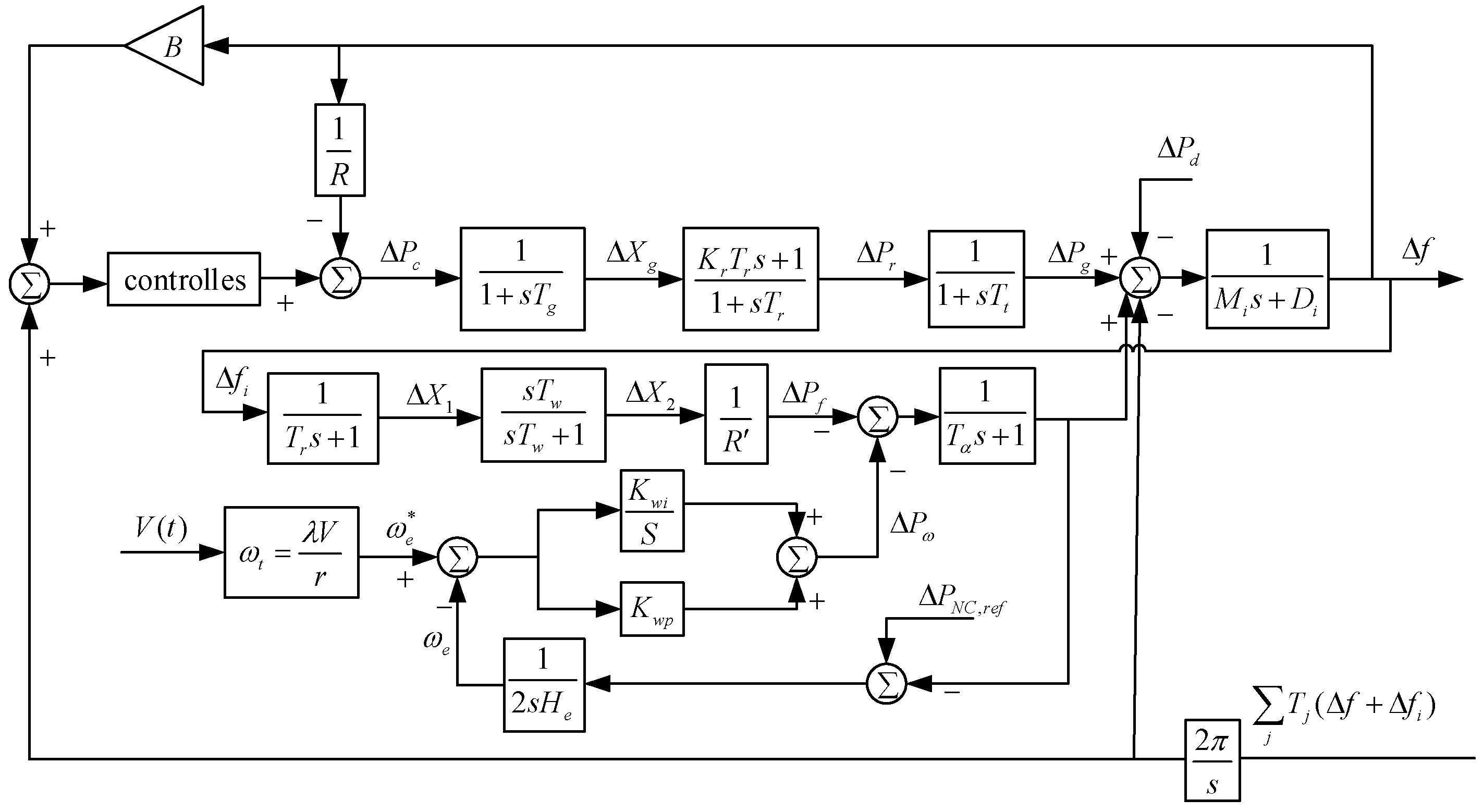

2.2. AGC Model Construction for Wind Power Participation

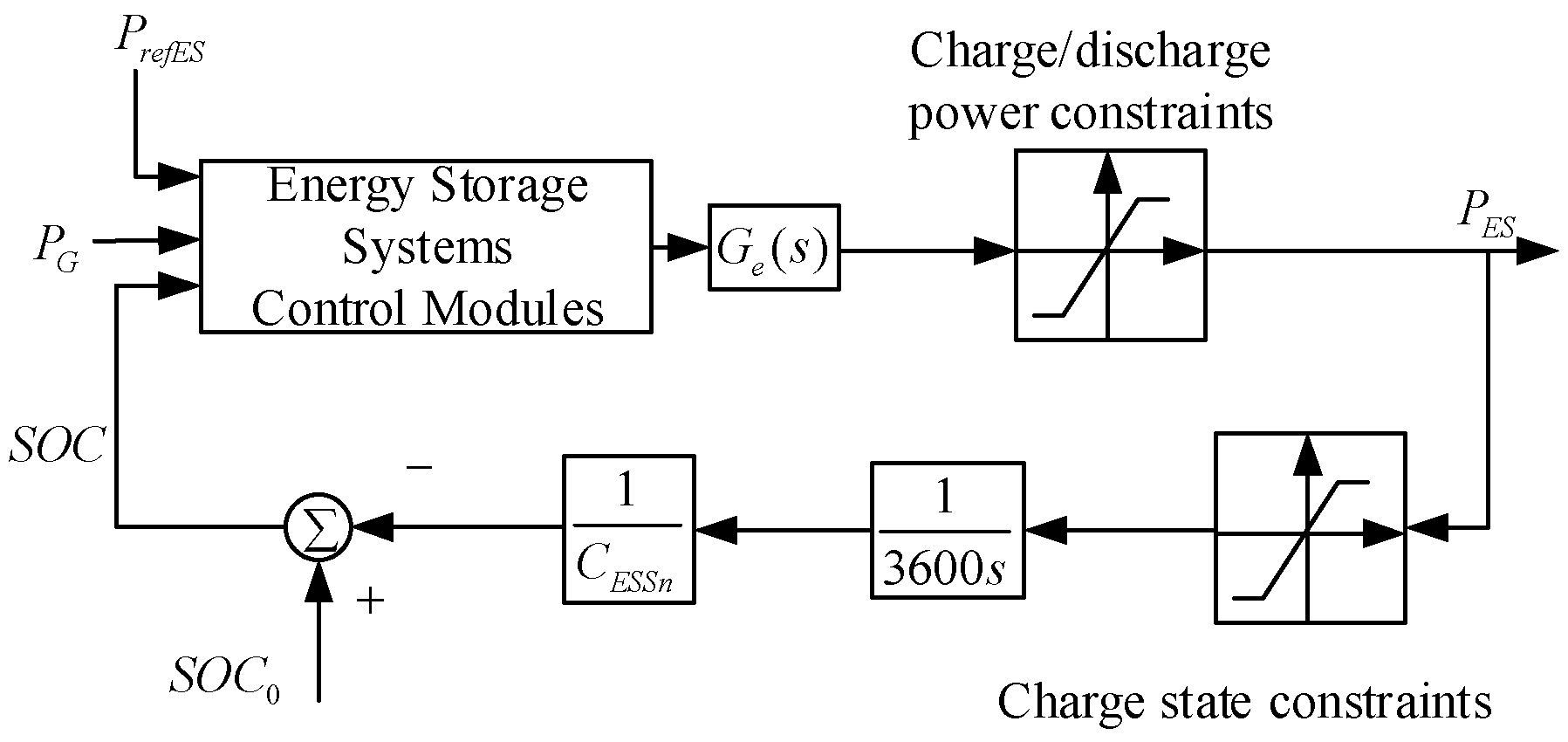

2.3. Battery Energy Storage System Participation in AGC Control Models

3. FM control strategy for wind power high penetration system considering energy storage SOC

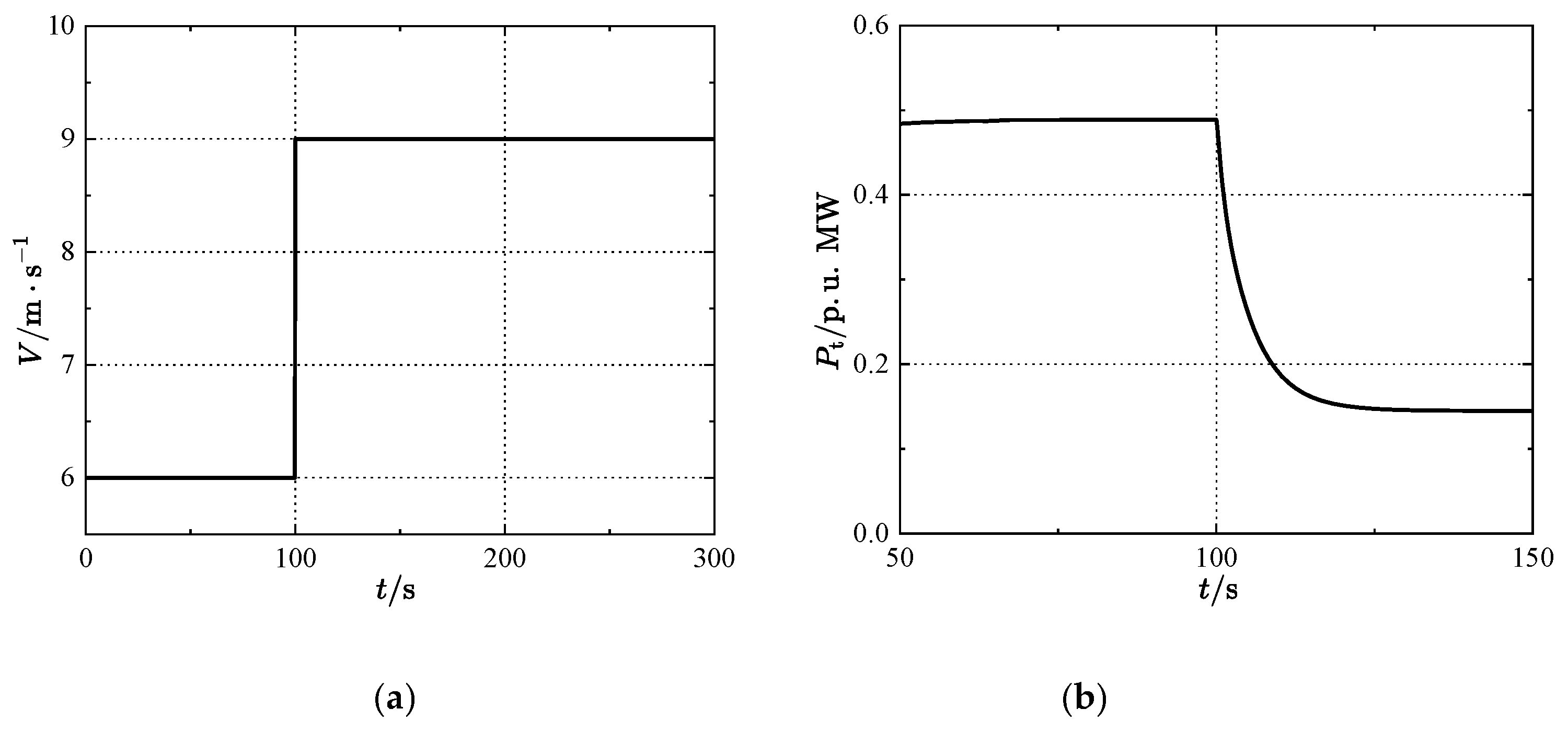

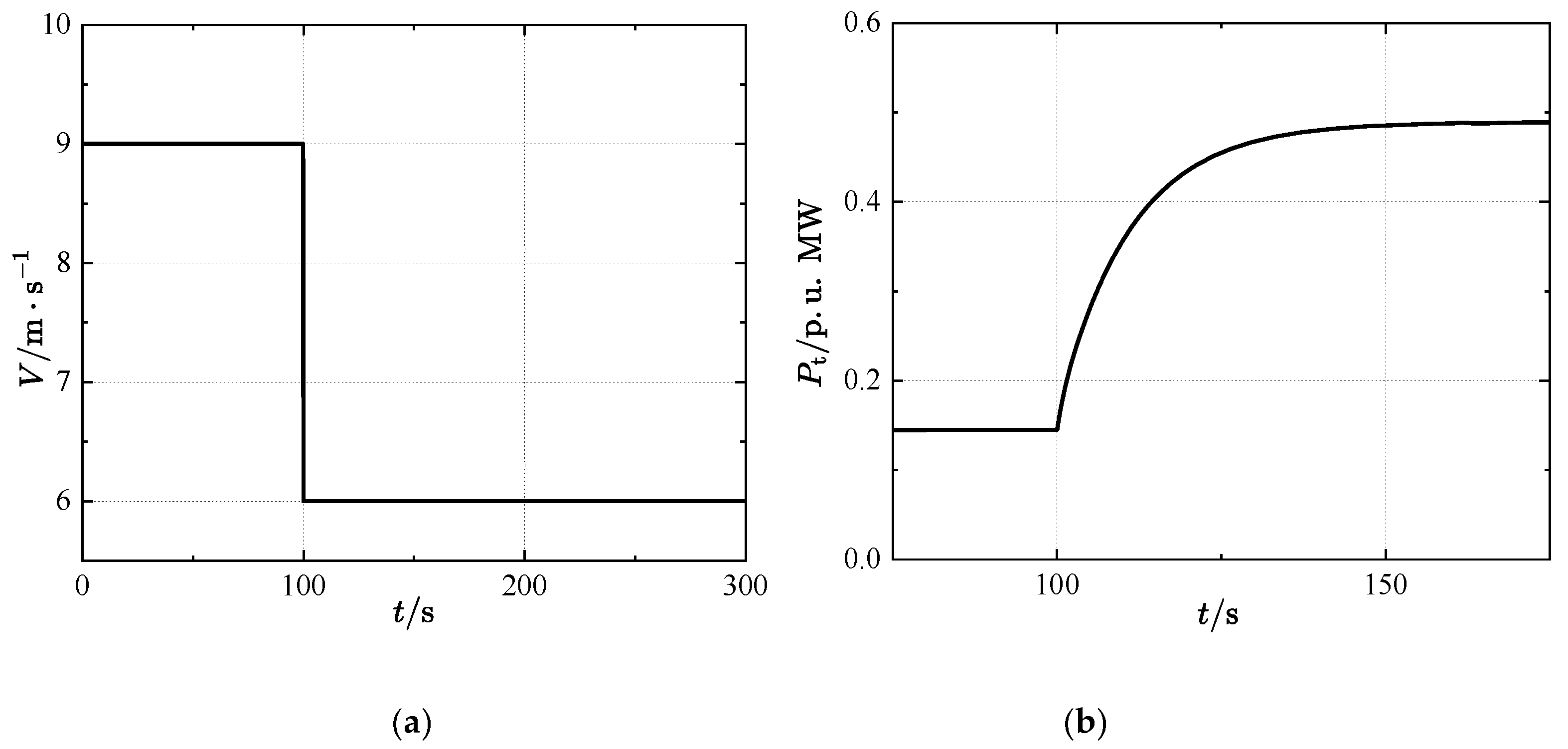

3.1. Effect of Wind Speed Variation on System Parameters

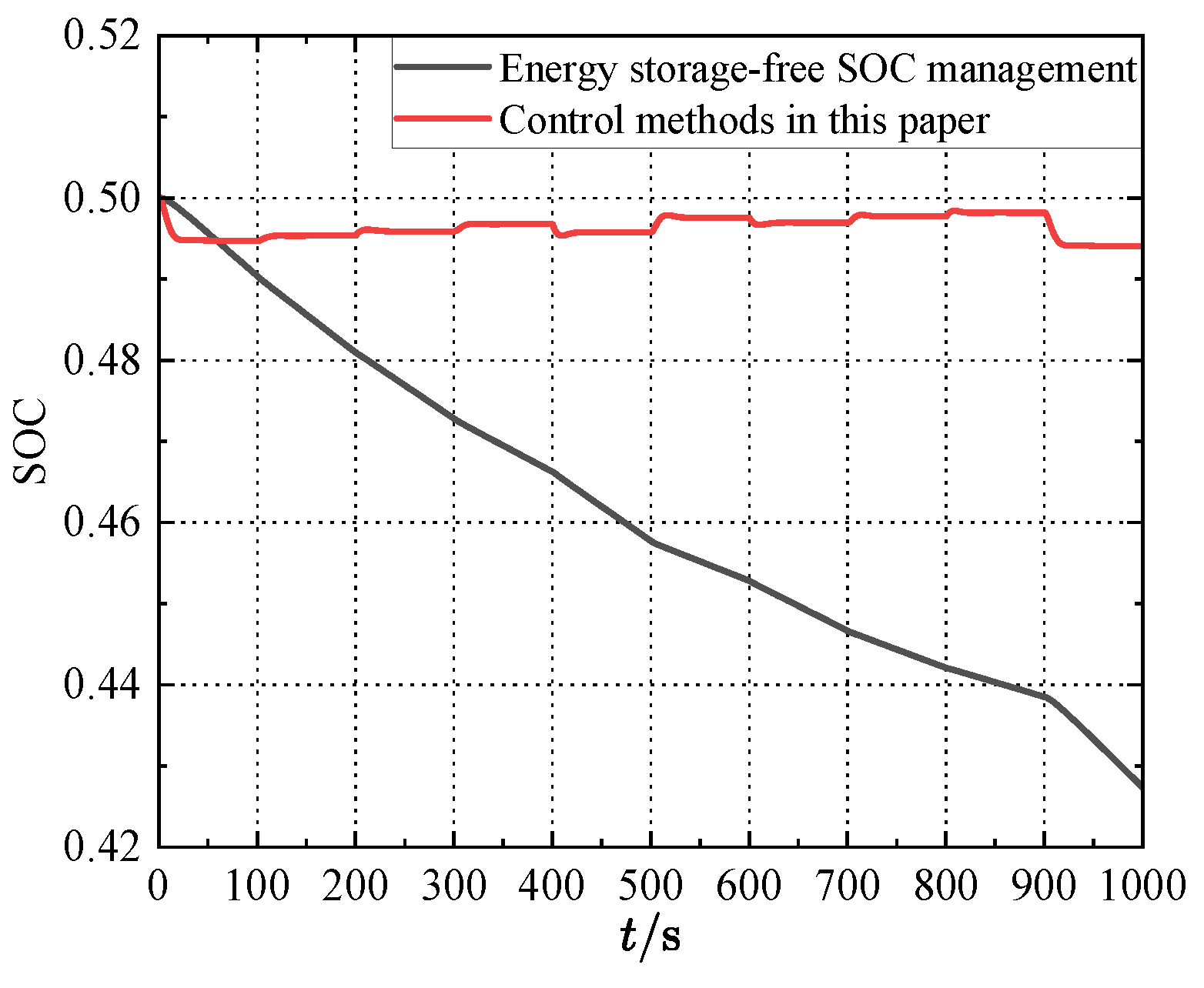

3.2. Energy Storage SOC Management

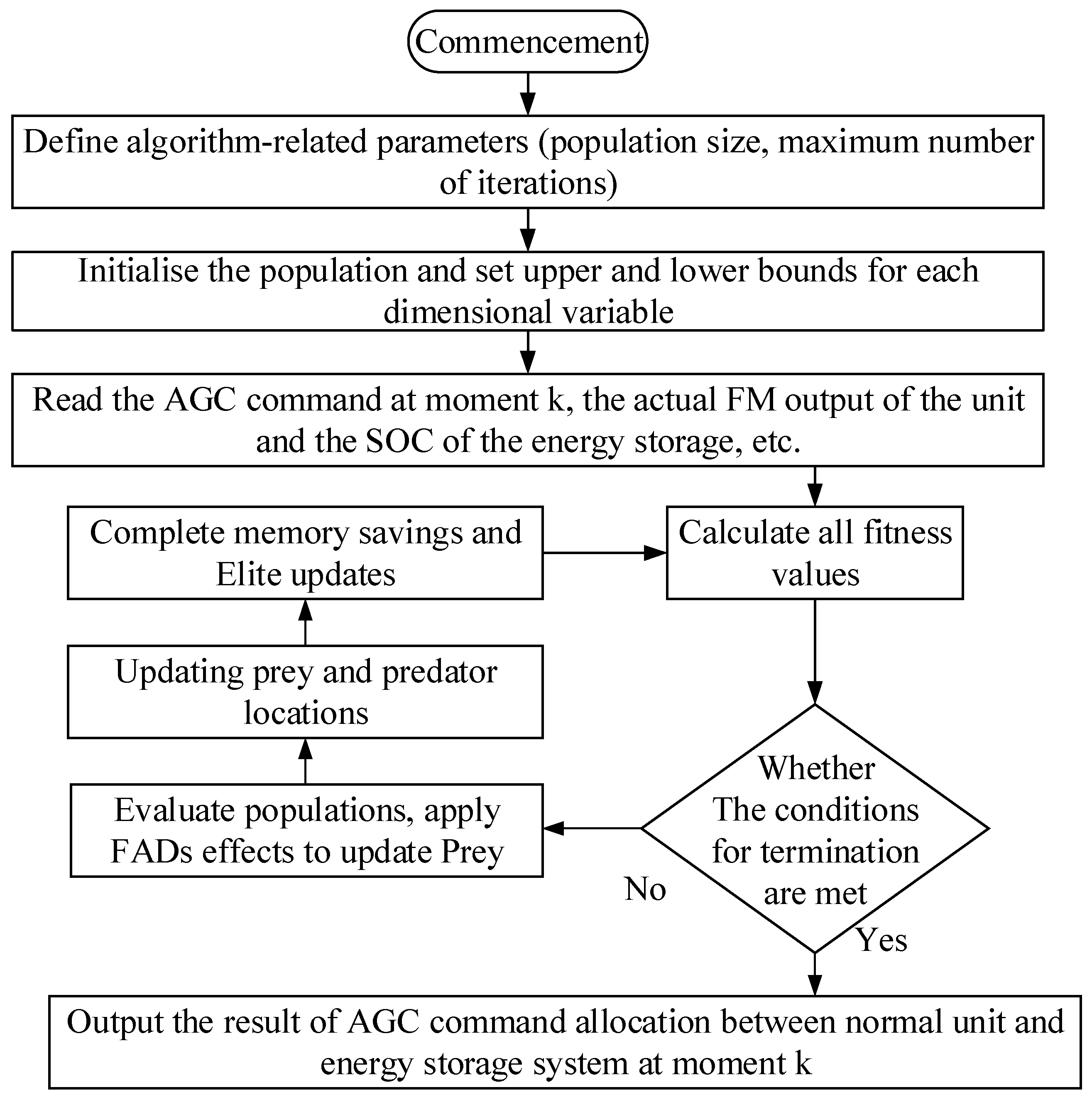

3.3. Real-time Optimisation of FM Control Process Based on Improved Marine Predator Algorithm

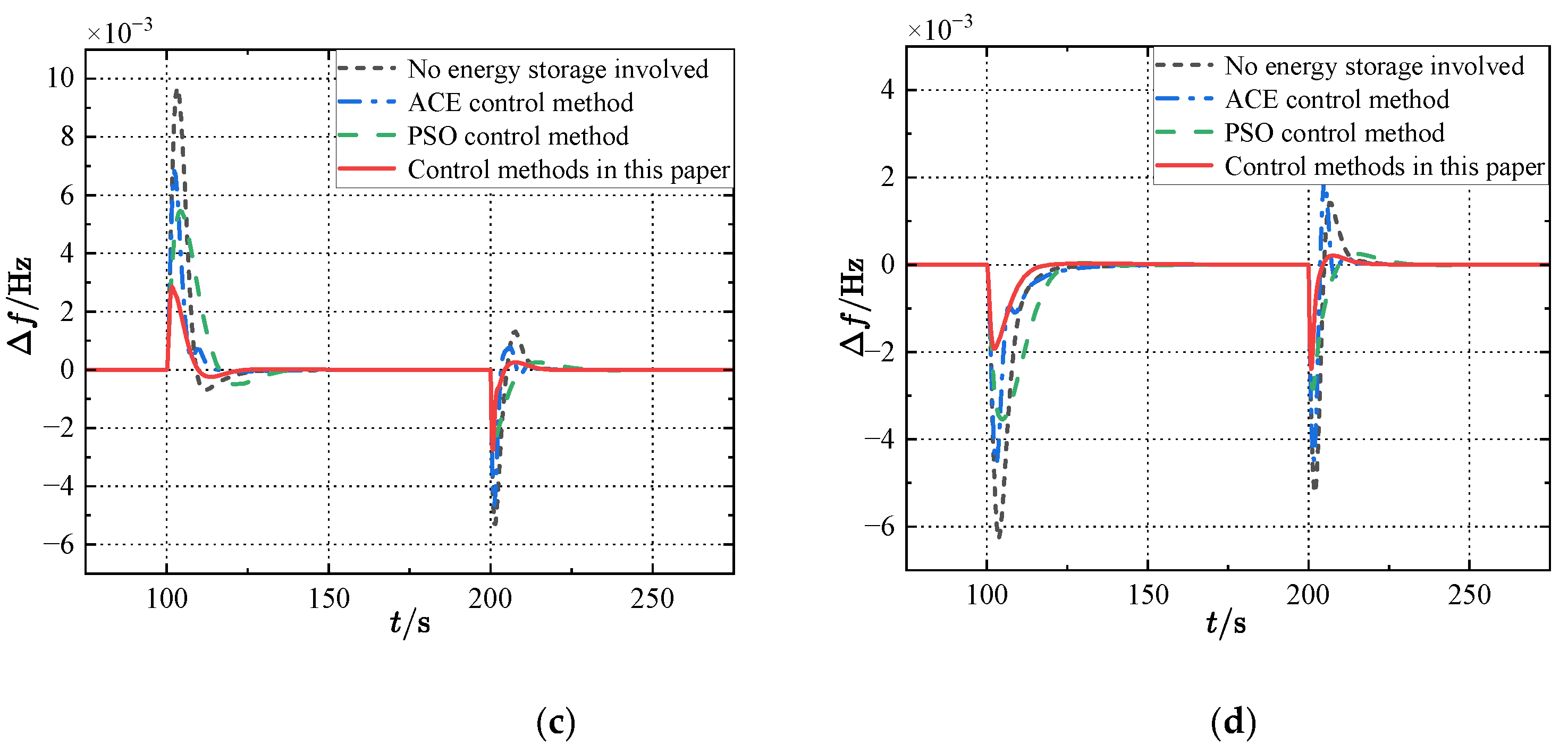

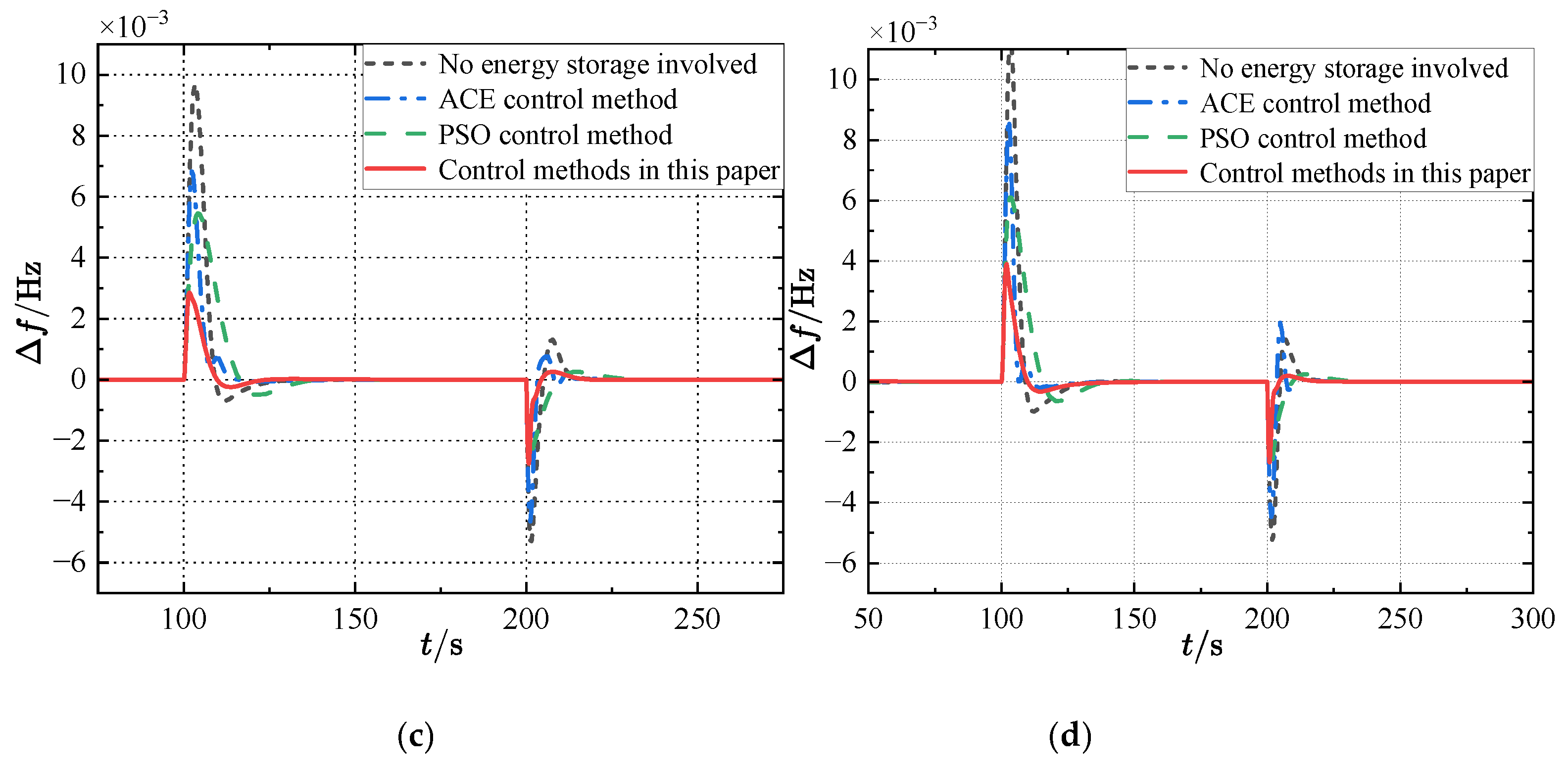

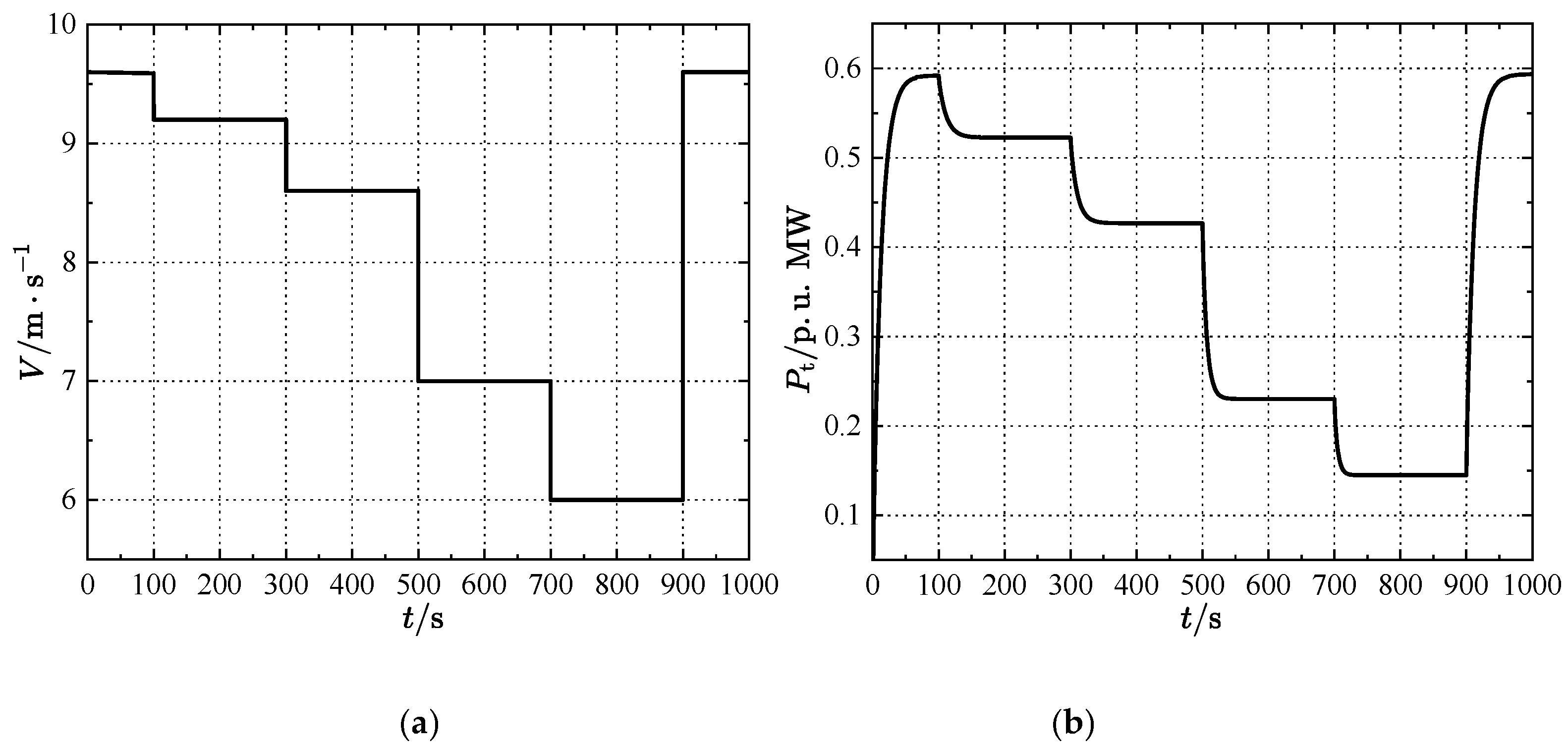

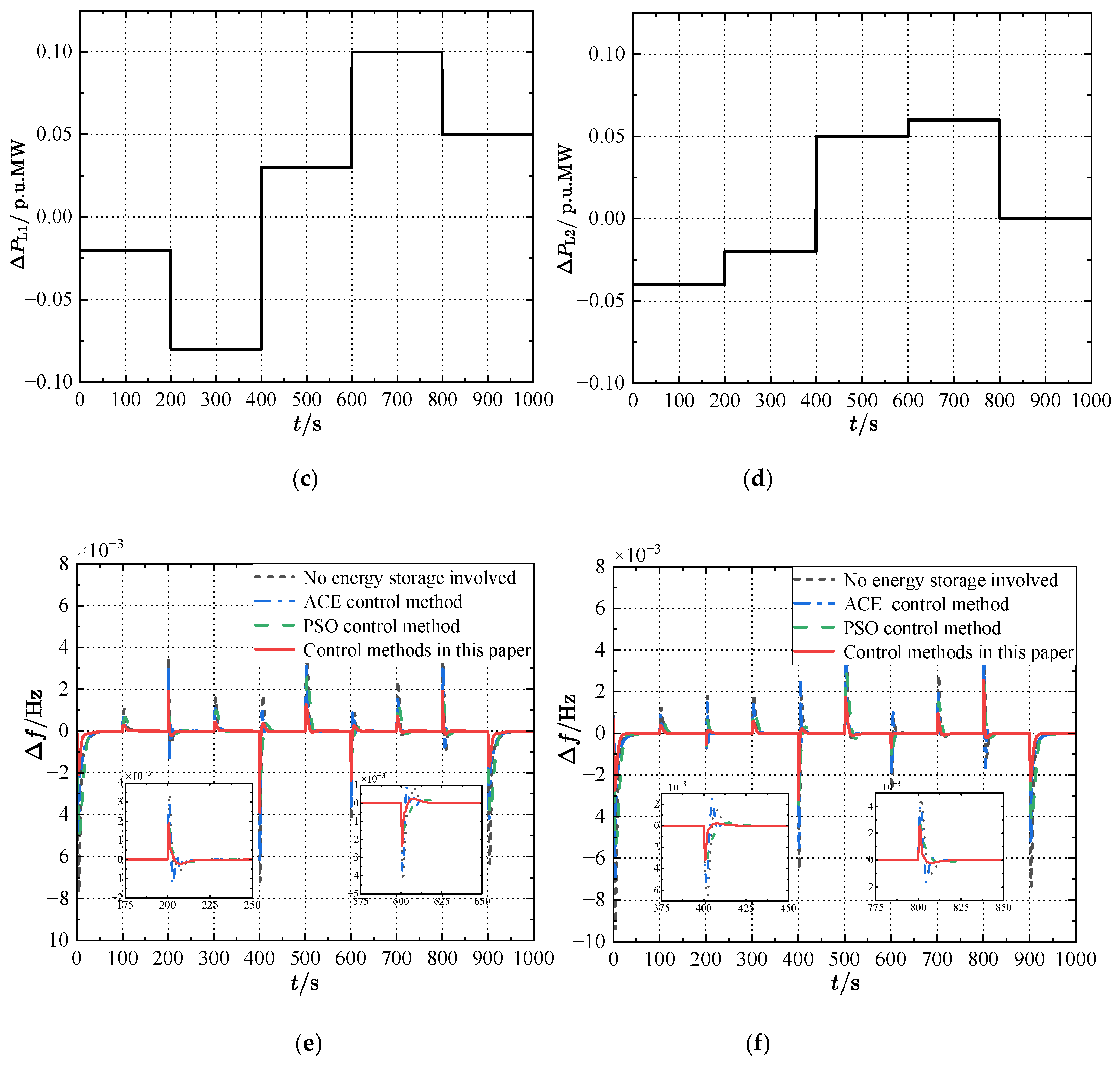

4. Simulation results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Δf | frequency deviation | Tw | turbine filter time constant |

| ΔP | deviation of the active power of the system | optimal rotational speed at the current wind speed | |

| D | damping coefficient of the system | Pt | output power of the wind generator |

| M | equivalent rotational inertia of the system | EB | rated capacity of the energy storage system |

| SOC | actual state of charge of the energy storage | He | turbine equivalent inertia time constant |

| PW | active power of wind units | Ta | turbine time constant |

| PES | active power of energy storage systems | PES | actual response power of the energy storage |

| PL | active power of load side | TG | governor time constant |

| rotational speed of the wind turbine at the current moment | PG | active power of thermal power units | |

| CP | performance coefficient of the wind turbine | SOC0 | initial state of charge of the energy storage |

| ratio of the rotor blade tip speed to the wind speed | TES | charge/discharge time constant of the energy storage system | |

| V(t) | real-time wind speed | PGN | rated output power of the genset |

| pitch angle of the paddle | PN | rated capacity of the wind turbine | |

| air density | wind power penetration rate | ||

| low-speed shaft rotational speed | f0 | initial frequency of the system | |

| r | radius of the wind turbine blades | f | rated frequency |

| ΔX2 | incremental frequency change of the wind turbine after the filter | J | rotational inertia of the wind turbine |

| falling rate coefficient | R | the generator modulation factor | |

|

KWP /KWI |

inherent PI controller parameters of the wind turbine | Hh | inherent inertia time constant of the thermal power unit |

| optimal rotational speed at the current wind speed | Pchm | the maximum charging power of the energy storage system | |

| Pcr max | the maximum power of the storage system during charging recovery | ΔX1 | incremental change in frequency of the turbine after the sensor |

| Vtotal | total investment cost of the BESS | ntotal | cycle life of the BESS |

| uch.t | BESS switches from discharging to charging state during t | udis.t | BESS switches from charging to discharging state during t |

References

- TANG Jian, SU Jiantao, YAO Yuge, et al. Technical analysis of power system frequency regulation by wind power for new power system[J].Thermal Power Generation,2022, 51(07: :1-8.

- LI Jianlin, NIU Meng, WANG Shangxing, et al.Operation and control analysis of 100 MW class battery energy storage station on grid side in Jiangsu power grid of China[J].Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2020, 44(2) :28-35.

- MEJÍA-GIRALDO D, VELÁSQUEZ-GOMEZ G, MUÑOZ GALEANO N, et al.A BESS sizing strategy for primary frequency regulation support of solar photovoltaic plants[J].Energies,2019, 12:317.

- WANG Ruifeng, GAO Lei, SHEN Jie, et al. Frequency regulation strategy with participation of variable-speed wind turbines for power system with high wind power penetration[J].Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2019,43(15) :101-108.

- XU Guoyi, HU Jiaxin, GUO Shufeng, et al. Improved frequency control strategy for over-speed wind turbines[J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2018, 42(8) :39-44.

- LI Yingying, WANG Delin, FAN Linyuan, et al. Variable Coefficient Control Strategy for Frequency Stability of DFIG Under Power-limited Operation[J]. Power System Technology, 2019, 43(8) :2910-2917. LIU Hongbo,PENG Xiaoyu, ZHANG Chong, et al. Overview of wind power participating in frequency regulation control strategy for power system[J].Electric Power Automation Equipment, 2021, 41(11) :81-92.

- Zhang Yuze. Correction of AGC Parameters with Large-scale Wind Power Integration Systems [J]. Electrical automation,2019,41(1):28-31.

- Li Shichun, Tang Hongyan, Liu Daobing, et al. Calculation of equivalent inertia time constant of power system with virtual inertial response of wind power [J]. Renewable Energy Resources,2018,36(10):1486-1491.

- TIAN Xinshou, WANG Weisheng, CHI Yongning et al. Variable Parameter Virtual Inertia Control Based on Effective Energy Storage of DFIG-based Wind Turbines [J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems,2015,39(5):20-26,33.

- GLOE, ARNE, JAUCH, CLEMENS, CRACIUN, BOGDAN, et al. Continuous provision of synthetic inertia with wind turbines: implications for the wind turbine and for the grid[J]. IET renewable power generation,2019,13(5):668-675.

- DING Dong, LIU Zongqi, YANG Shuili, et al. Battery energy storage aid automatic generation control for load frequency control based on fuzzy control [J]. Power System Protection and Control,2015,43(8):81-87.

- LI Xinran, DENG Tao, HUANG Jiyuan, et al. Battery Energy Storage Systems Self-adaptation Control Strategy in Fast Frequency Regulation [J]. High Voltage Engineering,2017,43(7):2362-2369.

- Li Xinran, Huang Jiyuan, Chen Yuanyang, et al. Battery Energy Storage Control Strategy in Secondary Frequency Regulation Considering Its Action Moment and Depth [J]. TRANSACTIONS OF CHINA ELECTROTECHNICAL SOCIETY,2017,32(12):224-233.

- A. Faramarzi, M. Heidarinejad, B. Stephens, and S. Mirjalili, ‘‘Equilibrium optimizer: A novel optimization algorithm,’’ Knowl.-Based Syst., vol. 191,Mar. 2020, Art. no. 105190.

- HU Zechun, XIA Rui, WU Linlin, et al. Joint Operation Optimization of Wind-Storage Union With Energy Storage Participating Frequency Regulation [J]. Power System Technology,2016,40(8):2251-2257.

- YANG Xiaoping, SONG Zhixiang, HU Yang, et al. Three-phase Power Flow Calculation for Medium-low Voltage Distribution Network Considering Control Equations of Distributed Generations [J]. Proceedings of the CSU-EPSA,2019,31(3):16-22.

- GUHA, DIPAYAN, ROY, PROVAS KUMAR, BANERJEE, SUBRATA. Load frequency control of interconnected power system using grey wolf optimization[J]. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation,2016,2797-115.

- Xilin Z, Zhenyu L, Bo F, Li H, Chaoshun L, et al. Research on the Predictive Optimal PID Plus Second Order Derivative Method for AGC of Power System with High Penetration of Photovoltaic and Wind Power[J]. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology, 2019, 14(3): 1075.0-1086.0.

- Yan Z, Guoqiang Y, Kaiming L, Hongxing W, Menglei G, Jianyong Z, et al. Improved Particle Swarm Optimization-based Thermal Power-energy Storage Combined AGC Frequency Regulation Control[J]. 2020 IEEE 3rd International Conference of Safe Production and Informatization (IICSPI), 2020.

- LI Ruo, LIXinran, TAN Zhuangxi, et al. Integrated Control Strategy Considering Energy Storage Battery Participating in Secondary Frequency Regulation [J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems,2018,42(8):74-82.

- HUANG Yawei, LI Xinran, HUANG Jiyuan, et al. Analysis of Control Methods for AGC with Battery Energy Storage System [J]. Proceedings of the CSU-EPSA,2017,29(3):83-89.

- Gaojun M, Qingqing C, Yukun S, Yufei R, Feng Z, Yao W, Ling S, et al. Energy Storage Auxiliary Frequency Modulation Control Strategy Considering Ace And Soc Of Energy Storage[J]. IEEE Access, 2021, 9: 26271-26277.

- LU Xiaojun, YI Jianwei, LI Yan Optimal Control Strategy of AGC With Participation of Energy Storage System Based on Multi-objective Mesh Adaptive Direct Search Algorithm [J]. Power System Technology,2019,43(6):2116-2124.

- JIN Lixin, ZHU Wu, HUA Yun-hao, et al. Optimal Control Strategy of Battery Energy Storage System Participating in AGC Based on Improved Beetle Antennae Search Algorithm [J]. Water Resources and Power,2021,39(7):206-210.

- Liang J J, Qin A K, Suganthan P N, et al. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions[J]. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation, 2006, 10(3): 281-295.

| Parameters | Region 1 | Region 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Mi | 10.5 | 10 |

| Di | 2.75 | 2.5 |

| Bi | 35 | 30 |

| Ri | 0.036 | 0.03 |

| Tri | 10 | 8 |

| Tgi | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| Kri | 0.25 | 0.2 |

| Tti | 0.2 | 0.15 |

| Tij | 0.0868 | 0.0867 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).