Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Receptors for the Immunoglobulin G Constant Fraction (FcγRs) are widely expressed in cells of the immune system. Complement-independent phagocytosis prompted FcγR research to show that the engagement of IgG immune complexes with FcγRs triggers a variety of cell host immune responses, such as phagocytosis, antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity, and NETosis, among others. However, variants of these receptors have been implicated in the development of and susceptibility to autoimmune diseases, such as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Currently, the knowledge of FcγR variants is a required field of antibody therapeutics, which includes the en-gineering of recombinant soluble human Fc gamma receptors, enhancing the inhibitory and blocking of the activating FcγRs function, vaccines, and organ transplantation. Importantly, recent interest in FcγRs is the Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE), a mechanism by which the pathogenesis of certain viral infections is enhanced. ADEs may be responsible for the severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, FcγRs have become a current research topic. Therefore, this review briefly describes some of the historical knowledge about the FcγR type I family in humans, including the structure, affinity, mechanism of ligand binding, FcγRs in diseases such as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), and the potential therapeutic approaches related to these receptors in SLE.

Keywords:

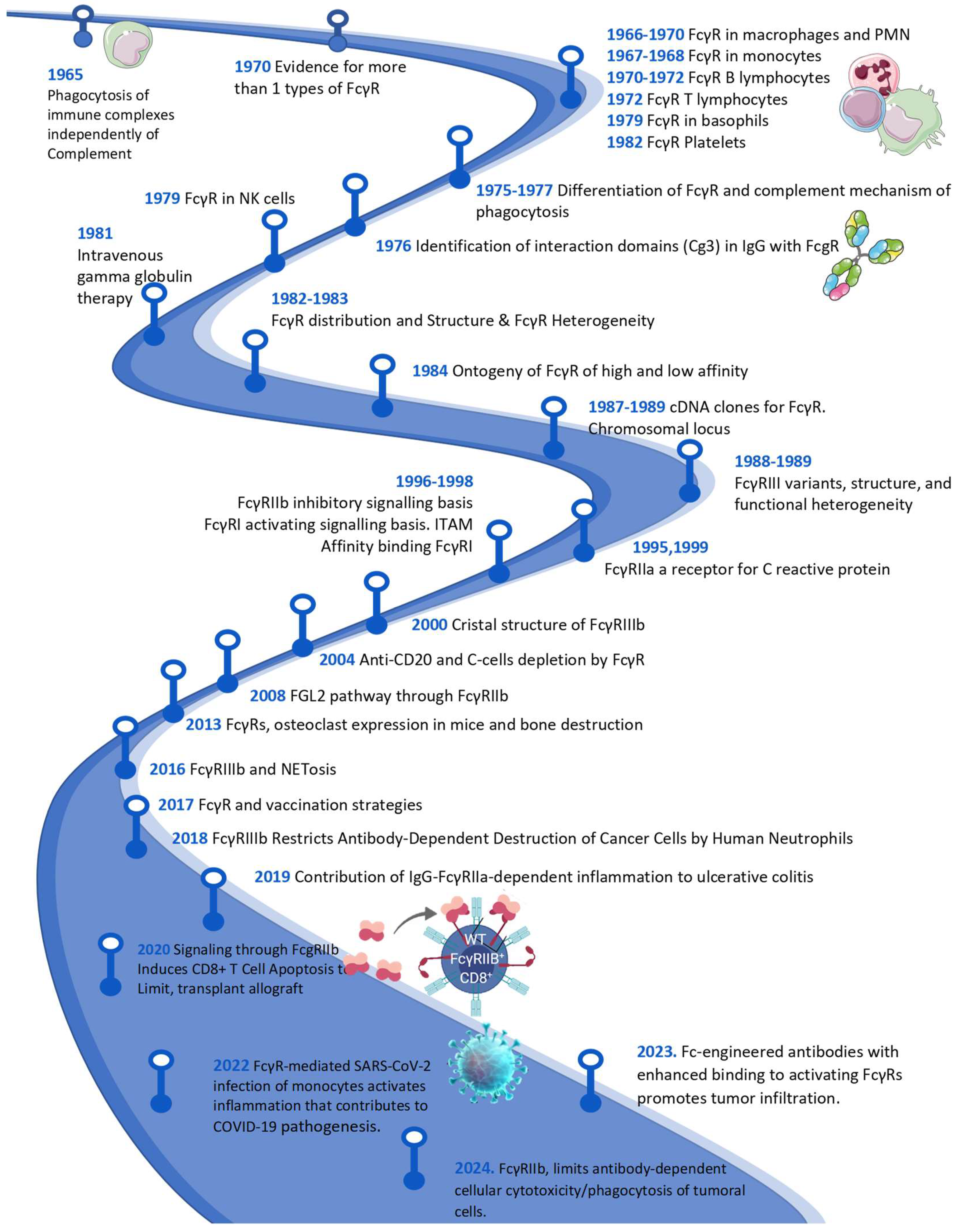

1. Introduction

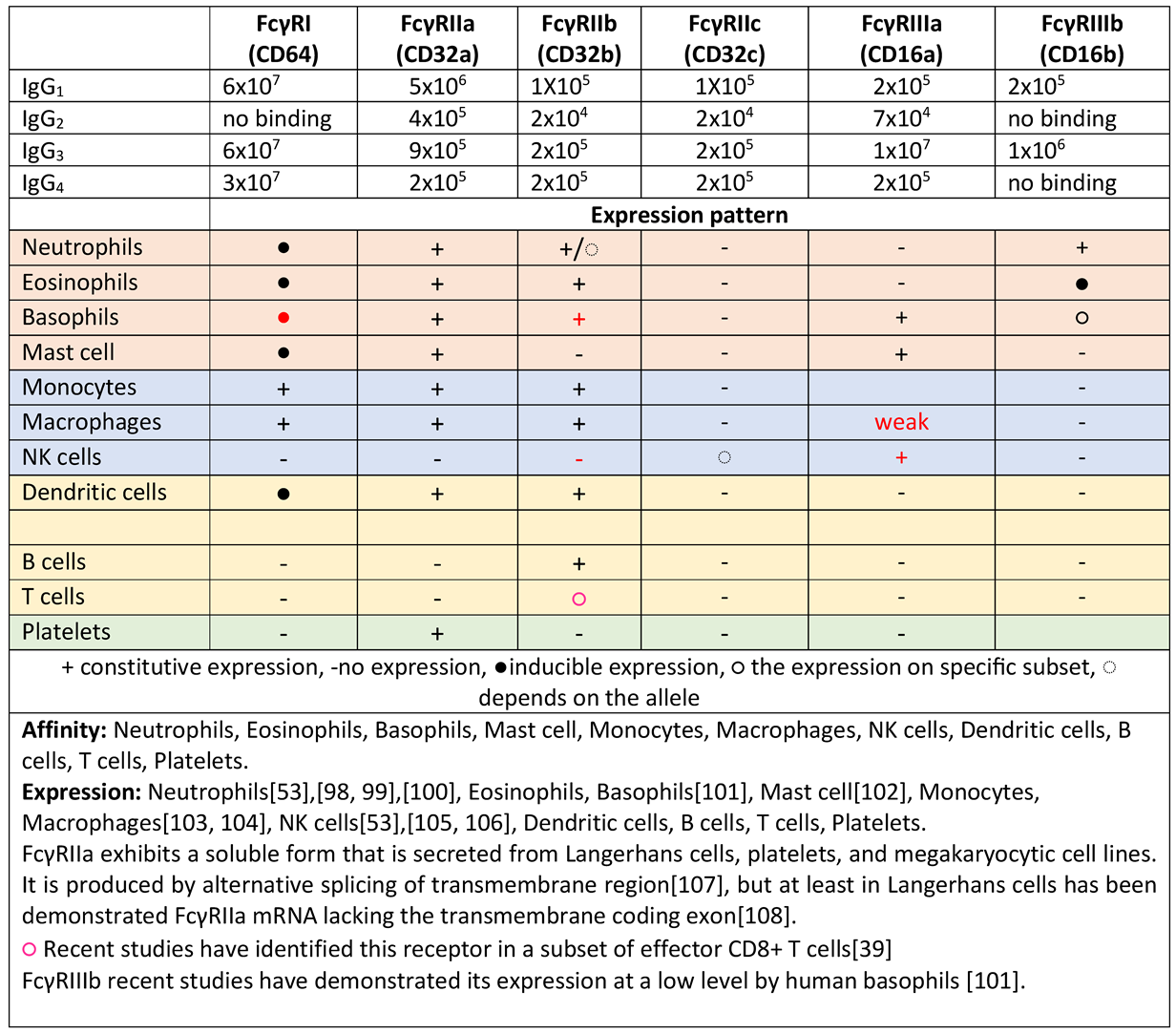

2. FcγRs Classification, Function, Variants & Role in SLE Pathology

1.1. FcγRI (CD64)

1.2. FcγRII (CD32)

1.2.1. FcγRIIa

1.2.2. FcγRIIb

1.3. FcγRIII

1.3.1. FcγRIIIa

1.3.2. FcγRIIIb

3. Ligand Binding

3.1. Immunological Functions of FcγRs

3.2. Phagocytosis

3.3. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity

3.4. NETosis

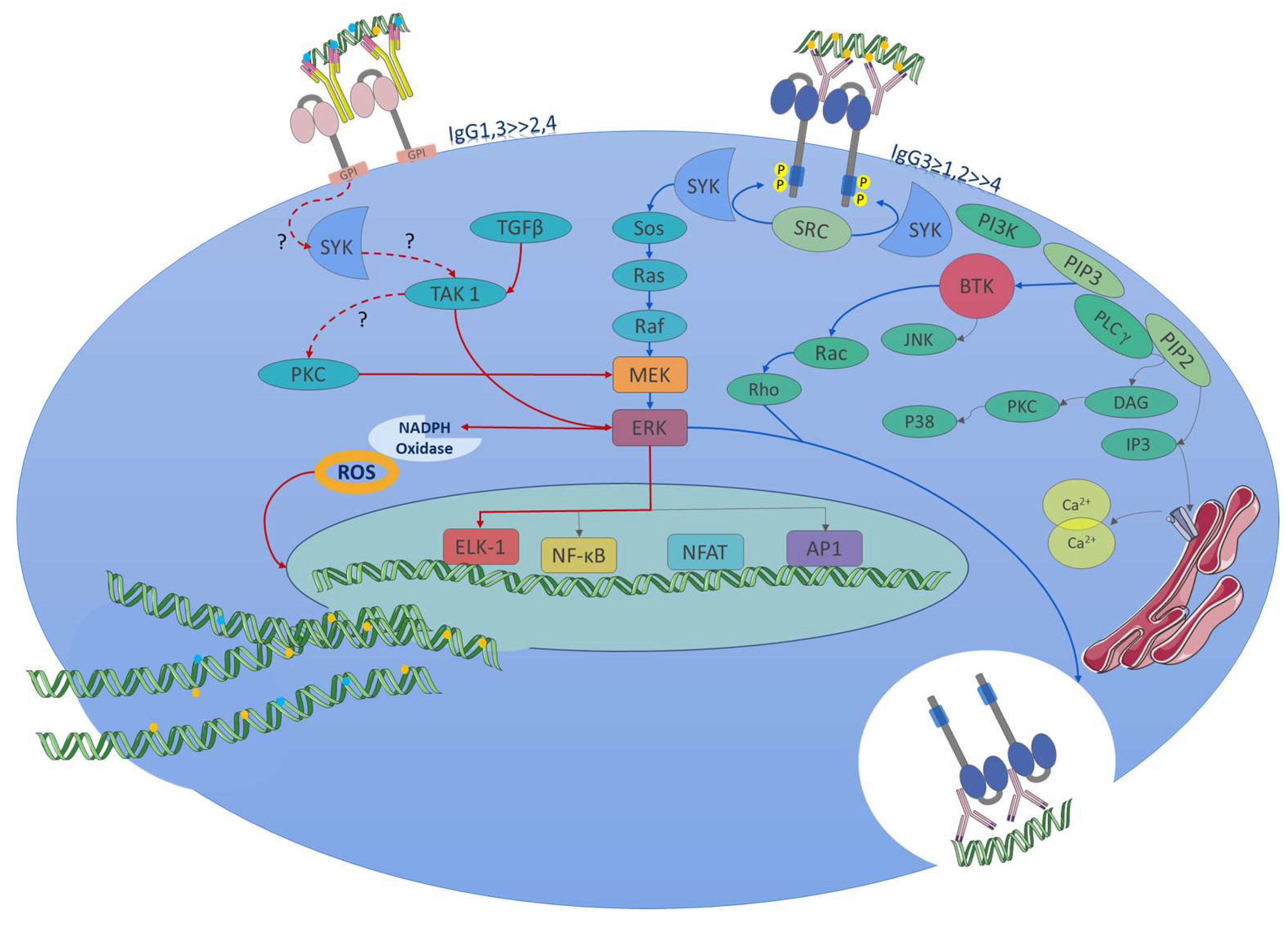

4. FcγR Signalling Pathways

4.1. Activating Signaling Pathway

4.2. Inhibitory Signaling Pathway

5. Roles in Non-Immune Cells

6. Functions in Disease

7. Therapeutic Approaches

7.1. FcγRs in the Mechanism of Action of Monoclonal Antibodies (mAb)

7.2. Organ Transplantation

7.3. Recombinant Soluble Human FcγRs

7.4. Antibody Therapeutics: Enhancing of Inhibitory Function & Blocking The Activating Function.

7.5. Antibody Therapeutics: Sialylation of Fc IgG to Generate Anti-Inflammatory Responses

7.6. Antibody Therapeutics: Vaccines & Potentiation of Immune Response

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

References

- Grundy, H.O. , et al., The polymorphic Fc gamma receptor II gene maps to human chromosome 1q. Immunogenetics 1989, 29, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzsch, E. , et al. , The human FCG1 gene encoding the high-affinity Fc gamma RI maps to chromosome 1q21. Immunogenetics 1993, 38, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S. , et al., Human high-affinity Fc gamma RI (CD64) gene mapped to chromosome 1q21.2-q21.3 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Hum Genet 1994, 93, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Peltz, G.; O Grundy, H.; Lebo, R.V.; Yssel, H.; Barsh, G.S.; Moore, K.W. Human Fc gamma RIII: cloning, expression, and identification of the chromosomal locus of two Fc receptors for IgG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989, 86, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, T.P. , et al., Assignment of three human high-affinity Fc gamma receptor I genes to chromosome 1, band q21.1. Immunogenetics 1993, 38, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleit, H.B.; Wright, S.D.; Durie, C.J.; E Valinsky, J.; Unkeless, J.C. Ontogeny of Fc receptors and complement receptor (CR3) during human myeloid differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G.T. Phagocytosis by human monocytes in red cells coated with Rh antibodies. Vox Sang 1965, 10, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berken, A.; Benacerraf, B. PROPERTIES OF ANTIBODIES CYTOPHILIC FOR MACROPHAGES. J. Exp. Med. 1966, 123, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoBuglio, A.F.; Cotran, R.S.; Jandl, J.H. Red Cells Coated with Immunoglobulin G: Binding and Sphering by Mononuclear Cells in Man. Science 1967, 158, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quie, P.G.; Messner, R.P.; Williams, R.C. PHAGOCYTOSIS IN SUBACUTE BACTERIAL ENDOCARDITIS. J. Exp. Med. 1968, 128, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, H.; Fudenberg, H. Receptor Sites of Human Monocytes for IgG. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1968, 34, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basten, A. , et al., A receptor for antibody on B lymphocytes. I. Method of detection and functional significance. J Exp Med 1972, 135, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basten, A. N.L. Warner, and T. Mandel, A receptor for antibody on B lymphocytes. II. Immunochemical and electron microscopy characteristics. J Exp Med 1972, 135, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, M.; Lüscher, E. Macrophage receptors for IgG aggregates. Exp. Cell Res. 1970, 59, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickler, H.B.; Kunkel, H.G. Interaction of aggregated -globulin with B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1972, 136, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, B. Different Roles of IgG and Complement Receptors in Phagocytosis by Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. J. Immunol. 1975, 115, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmeen, D.; Ellerson, J.R.; Dorrington, K.J.; Painter, R.H. The structure and function of immunoglobulin domains. IV. The distribution of some effector functions among the Cgamma2 and Cgamma3 homology regions of human immunoglobulin G1. J Immunol 1976, 116, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G. Differences in the Mode of Phagocytosis with Fc and C3 Receptors in Macrophages. Scand. J. Immunol. 1977, 6, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaka, T.; Sterk, A.; Ishizaka, K. Demonstration of Fcgamma receptors on human basophil granulocytes. J Immunol. 1979, 123, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Gresser, I.; Bandu, M.T.; Aguet, M.; Neauport-Sautes, C. Interferon enhances the expression of Fc gamma receptors. J. Immunol. 1980, 124, 2436–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleit, H.B.; Wright, S.D.; Unkeless, J.C. Human neutrophil Fc gamma receptor distribution and structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1982, 79, 3275–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, D.W., A. Narendran, and N.D. Hall, Heterogeneity of Fc gamma receptor expression on human cell lines. Immunol Lett 1983, 7, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengelin, S.; Stamenkovic, I.; Seed, B. Isolation of cDNAs for two distinct human Fc receptors by ligand affinity cloning. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanier, L.L.; Ruitenberg, J.J.; Phillips, J.H. Functional and biochemical analysis of CD16 antigen on natural killer cells and granulocytes. J. Immunol. 1988, 141, 3478–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, J.C.; Redecha, P.B.; E Salmon, J.; Kimberly, R.P. Human Fc gamma RIII (CD16). Isoforms with distinct allelic expression, extracellular domains, and membrane linkages on polymorphonuclear and natural killer cells. J. Immunol. 1989, 143, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scallon, B.J.; Scigliano, E.; Freedman, V.H.; Miedel, M.C.; Pan, Y.C.; Unkeless, J.C.; Kochan, J.P. A human immunoglobulin G receptor exists in both polypeptide-anchored and phosphatidylinositol-glycan-anchored forms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 5079–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.G.; Qiu, W.Q.; Luster, A.D.; Ravetch, J.V. Structure and expression of human IgG FcRII(CD32). Functional heterogeneity is encoded by the alternatively spliced products of multiple genes. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 170, 1369–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnell, L.L.; Mold, C.; A Volzer, M.; Burlingame, R.W.; Du Clos, T.W. C-reactive protein binds to Fc gamma RI in transfected COS cells. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 2185–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M. , et al., Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor Fc(gamma)RIIB. Nature 1996, 383, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulett, M.D. and P.M. Hogarth, The second and third extracellular domains of FcgammaRI (CD64) confer the unique high affinity binding of IgG2a. Mol Immunol 1998, 35, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, D. , et al., The major receptor for C-reactive protein on leukocytes is fcgamma receptor II. J Exp Med 1999, 190, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondermann, P. , et al., The 3.2-A crystal structure of the human IgG1 Fc fragment-Fc gammaRIII complex. Nature 2000, 406, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, J.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Oliver, J.A.; Ravetch, J.V.; Poe, J.C.; Haas, K.M.; Tedder, T.F. The Innate Mononuclear Phagocyte Network Depletes B Lymphocytes through Fc Receptor–dependent Mechanisms during Anti-CD20 Antibody Immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. , et al., The FGL2-FcgammaRIIB pathway: a novel mechanism leading to immunosuppression. Eur J Immunol 2008, 38, 3114–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeling, M.; Hillenhoff, U.; David, J.P.; Schett, G.; Tuckermann, J.; Lux, A.; Nimmerjahn, F. Inflammatory monocytes and Fcγ receptor IV on osteoclasts are critical for bone destruction during inflammatory arthritis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10729–10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, O.R.; Mora, N.; Cortes-Vieyra, R.; Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Differential Use of Human Neutrophil FcγReceptors for Inducing Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournazos, S.; Ravetch, J.V. Fcγ Receptor Function and the Design of Vaccination Strategies. Immunity 2017, 47, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Dopico, T.; Dennison, T.; Ferdinand, J.; Mathews, R.; Fleming, A.; Clift, D.; Stewart, B.J.; Jing, C.; Strongili, K.; I Labzin, L.; et al. Anti-commensal IgG Drives Intestinal Inflammation and Type 17 Immunity in Ulcerative Colitis. Immunity 2019, 50, 1099–1114.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.B.; Farley, C.R.; Ford, M.L.; Pinelli, D.F.; Adams, L.E.; Cragg, M.S.; Boss, J.M.; Scharer, C.D.; Fribourg, M.; Cravedi, P.; et al. Signaling through the Inhibitory Fc Receptor FcγRIIB Induces CD8+ T Cell Apoptosis to Limit T Cell Immunity. Immunity 2020, 52, 136–150.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, C. , et al., FcγR-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes activates inflammation. Nature 2022, 606, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, J.C. , et al., The antitumor activities of anti-CD47 antibodies require Fc-FcγR interactions. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 2051–2065.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, D.A.; Blanchard, L.; Leidner, R.S.; Jensen, S.M.; Meng, R.; Jones, A.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Bell, R.B.; Baez, M.; Marino, A.; et al. FcγRIIB Is an Immune Checkpoint Limiting the Activity of Treg-Targeting Antibodies in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2023, 12, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Shen, L.; Eicher, D.M.; Wewers, M.D.; Gill, J.K. Phagocytosis mediated by three distinct Fc gamma receptor classes on human leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1990, 171, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.; Heijnen, I.; Capel, P.; Park, S.; Ra, C.; Saito, T.; Verbeek, J.; van de Winkel, J. FcR gamma-chain is essential for both surface expression and function of human Fc gamma RI (CD64) in vivo. Blood 1996, 87, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillooly, D.J. and J.M. Allen, The human high affinity IgG receptor (Fc gamma RI) signals through the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the gamma chain of Fc epsilon RI. Biochem Soc Trans 1997, 25, 215s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tridandapani, S.; Siefker, K.; Carter, J.E.; Wewers, M.D.; Anderson, C.L.; Teillaud, J.-L. Regulated Expression and Inhibitory Function of FcγRIIb in Human Monocytic Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 5082–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.M. A.D. Schreiber, and E.J. Brown, Role for a glycan phosphoinositol anchor in Fc gamma receptor synergy. J Cell Biol 1997, 139, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Chu, J.; Zou, Z.; Hamacher, N.B.; Rixon, M.W.; Sun, P.D. Structure of FcγRI in complex with Fc reveals the importance of glycan recognition for high-affinity IgG binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, F. and J.V. Ravetch, Fcgamma receptors: old friends and new family members. Immunity 2006, 24, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulett, M.D. and P.M. Hogarth, Molecular basis of Fc receptor function. Adv Immunol 1994, 57, 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.M.; Seed, B. Isolation and Expression of Functional High-Affinity Fc Receptor Complementary DNAs. Science 1989, 243, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, S.G.; Trounstine, M.L.; Vaux, D.J.; Koch, T.; Martens, C.L.; Mellman, I.; Moore, K.W. Isolation and expression of cDNA clones encoding a human receptor for IgG (Fc gamma RII). J. Exp. Med. 1987, 166, 1668–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetch, J.V.; Perussia, B. Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII(CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. . J. Exp. Med. 1989, 170, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perussia, B. and J.V. Ravetch, Fc gamma RIII (CD16) on human macrophages is a functional product of the Fc gamma RIII-2 gene. Eur J Immunol 1991, 21, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Peltz, G.; Trounstine, M.L.; Moore, K.W. Cloned and expressed human Fc receptor for IgG mediates anti-CD3-dependent lymphoproliferation. J. Immunol. 1988, 141, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilliam, A.L.; Osman, N.; McKenzie, I.F.; Hogarth, P.M. Biochemical characterization of murine Fc gamma RI. Immunology 1993, 78, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hulett, M.D.; Osman, N.; McKenzie, I.F.; Hogarth, P.M. Chimeric Fc receptors identify functional domains of the murine high affinity receptor for IgG. J. Immunol. 1991, 147, 1863–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Ellsworth, J.L.; Hamacher, N.; Oak, S.W.; Sun, P.D. Crystal Structure of Fcγ Receptor I and Its Implication in High Affinity γ-Immunoglobulin Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 40608–40613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, L.; Tan, Z.; Wu, H.; Chen, F.; Huang, J.; Wang, P.; Hambly, B.D.; Bao, S.; Tao, K. CD64 plays a key role in diabetic wound healing. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1322256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, P.Y.; Kellner, E.S.; Paulus, M.; Switanek, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Sobel, E.S.; Segal, M.S.; Satoh, M.; et al. Monocyte surface expression of Fcγ receptor RI (CD64), a biomarker reflecting type-I interferon levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , et al., Increased expression of FcgammaRI/CD64 on circulating monocytes parallels ongoing inflammation and nephritis in lupus. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11, p R6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S. , et al., IgG-aggregates rapidly upregulate FcgRI expression at the surface of human neutrophils in a FcgRII-dependent fashion: A crucial role for FcgRI in the generation of reactive oxygen species. Faseb j 2020, 34, 15208–15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewarder, N. , et al., In vivo and in vitro specificity of protein tyrosine kinases for immunoglobulin G receptor (FcgammaRII) phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16, 4735–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsland, P.A. , et al., Structural basis for Fc gammaRIIa recognition of human IgG and formation of inflammatory signaling complexes. J Immunol 2011, 187, 3208–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Salmon, J.; Edberg, J.C.; Brogle, N.L.; Kimberly, R.P. Allelic polymorphisms of human Fc gamma receptor IIA and Fc gamma receptor IIIB. Independent mechanisms for differences in human phagocyte function. . J. Clin. Investig. 1992, 89, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Tsao, B.P. Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, J.d.S.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Silva, M.V.; Sales-Campos, H.; de Vito, F.B.; da Silva, D.A.A.; Naves, L.L.; Oliveira, C.J.F.; Rodrigues, D.B.R.; Rodrigues, V. Genetic variation of FcγRIIa induces higher uptake of Leishmania infantum and modulates cytokine production by adherent mononuclear cells in vitro. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1343602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashidharamurthy, R. et al., Dynamics of the Interaction of Human IgG Subtype Immune Complexes with Cells Expressing R and H Allelic Forms of a Low-Affinity Fc Receptor CD32A. J Immunol 2009, 183, 8216–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonegio, R.G. , et al., Lupus-Associated Immune Complexes Activate Human Neutrophils in an FcγRIIA-Dependent but TLR-Independent Response. The Journal of Immunology 2019, 202, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daëron, M. , et al., The same tyrosine-based inhibition motif, in the intracytoplasmic domain of Fc gamma RIIB, regulates negatively BCR-, TCR-, and FcR-dependent cell activation. Immunity 1995, 3, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, S.-J.; Li, W.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y. FcγRIIB mediates antigen-independent inhibition on human B lymphocytes through Btk and p38 MAPK. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , et al., A novel polymorphism in the Fcgamma receptor IIB (CD32B) transmembrane region alters receptor signaling. Arthritis Rheum 2003, 48, 3242–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyogoku, C. , et al., Fcgamma receptor gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: contribution of FCGR2B to genetic susceptibility. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floto, R.A. , et al., Loss of function of a lupus-associated FcgammaRIIb polymorphism through exclusion from lipid rafts. Nat Med 2005, 11, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, H. , et al., FcgammaRIIB Ile232Thr transmembrane polymorphism associated with human systemic lupus erythematosus decreases affinity to lipid rafts and attenuates inhibitory effects on B cell receptor signaling. Hum Mol Genet 2005, 14, 2881–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K. , et al., A promoter haplotype of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing FcgammaRIIb alters receptor expression and associates with autoimmunity. I. Regulatory FCGR2B polymorphisms and their association with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2004, 172, 7186–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K. , et al., A promoter haplotype of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing FcgammaRIIb alters receptor expression and associates with autoimmunity. II. Differential binding of GATA4 and Yin-Yang1 transcription factors and correlated receptor expression and function. J Immunol 2004, 172, 7192–7199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, K. , et al., A Promoter Haplotype of the Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Inhibitory Motif-Bearing FcγRIIb Alters Receptor Expression and Associates with Autoimmunity. I. Regulatory FCGR2B Polymorphisms and Their Association with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. The Journal of Immunology 2004, 172, 7186–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang-A-Sjoe, M.W.P.; Nagelkerke, S.Q.; Bultink, I.E.M.; Geissler, J.; Tanck, M.W.T.; Tacke, C.E.; Ellis, J.A.; Zenz, W.; Bijl, M.; Berden, J.H.; et al. Fc-gamma receptor polymorphisms differentially influence susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Rheumatology 2016, 55, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimifar, M.; Akbari, K.; ArefNezhad, R.; Fathi, F.; Ghasroldasht, M.M.; Motedayyen, H. Impacts of FcγRIIB and FcγRIIIA gene polymorphisms on systemic lupus erythematous disease activity index. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clatworthy, M.R.; Harford, S.K.; Mathews, R.J.; Smith, K.G.C. FcγRIIb inhibits immune complex-induced VEGF-A production and intranodal lymphangiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17971–17976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, S.; Ravetch, J.V. Spontaneous autoimmune disease in Fc(gamma)RIIB-deficient mice results from strain-specific epistasis. Immunity 2000, 13, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhunyakarnjanarat, T.; Makjaroen, J.; Saisorn, W.; Hirunsap, K.; Chiewchengchol, J.; Ritprajak, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Lupus exacerbation in ovalbumin-induced asthma in Fc gamma receptor IIb deficient mice, partly due to hyperfunction of dendritic cells. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunyakarnjanarat, T.; Udompornpitak, K.; Saisorn, W.; Chantraprapawat, B.; Visitchanakun, P.; Dang, C.P.; Issara-Amphorn, J.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Prominent Indomethacin-Induced Enteropathy in Fcgriib Defi-cient lupus Mice: An Impact of Macrophage Responses and Immune Deposition in Gut. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chancharoenthana, W. , et al., Enhanced lupus progression in alcohol-administered Fc gamma receptor-IIb-deficiency lupus mice, partly through leaky gut-induced inflammation. Immunol Cell Biol 2023, 101, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycki, A. Human neutrophils and eosinophils have structurally distinct Fc gamma receptors. . J. Immunol. 1984, 133, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Taeye, S.W. , et al., FcγR Binding and ADCC Activity of Human IgG Allotypes. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.L.; Kainz, A.; Hidalgo, L.G.; Eskandary, F.; Kozakowski, N.; Wahrmann, M.; Haslacher, H.; Oberbauer, R.; Heilos, A.; Spriewald, B.M.; et al. Functional Fc gamma receptor gene polymorphisms and donor-specific antibody-triggered microcirculation inflammation. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 2261–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, J.C. , et al., Genetic linkage and association of Fcgamma receptor IIIA (CD16A) on chromosome 1q23 with human systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46, 2132–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ptacek, T.S.; E Brown, E.; Edberg, J.C. Fcγ receptors: structure, function and role as genetic risk factors in SLE. Genes Immun. 2009, 10, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marois, L. , et al., Fc RIIIb Triggers Raft-dependent Calcium Influx in IgG-mediated Responses in Human Neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286, 3509–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, V.C.; Grecco, M.; Pereira, K.M.C.; Terzian, C.C.N.; Andrade, L.E.C.; Silva, N.P. Fc gamma receptor IIIb polymorphism and systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease susceptibility and identification of a novel FCGR3B*01 variant. Lupus 2016, 25, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatta, Y. , et al., Association of Fc gamma receptor IIIB, but not of Fc gamma receptor IIA and IIIA polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus in Japanese. Genes Immun 1999, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurlander, R.J.; Batker, J. The Binding of Human Immunoglobulin G1 Monomer and Small, Covalently Cross-Linked Polymers of Immunoglobulin G1 to Human Peripheral Blood Monocytes and Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1982, 69, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, R.P. and J. Jelinek, Receptors for human gamma G globulin on human neutrophils. J Clin Invest 1970, 49, 2165–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleit, H.B.; Wright, S.D.; Durie, C.J.; E Valinsky, J.; Unkeless, J.C. Ontogeny of Fc receptors and complement receptor (CR3) during human myeloid differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Guyre, P.M.; Fanger, M.W. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte function triggered through the high affinity Fc receptor for monomeric IgG. J. Immunol. 1987, 139, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Quayle, J.; Watson, F.; Bucknall, R.C.; Edwards, S.W. Neutrophils from the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis express the high affinity immunoglobulin G receptor, FcγRI (CD64): role of immune complexes and cytokines in induction of receptor expression. Immunology 1997, 91, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, S.; Venkiteswaran, K.; Anderson, M.; Sayed, U.; Zhu, C.; Selvaraj, P. Cell-specific, activation-dependent regulation of neutrophil CD32A ligand-binding function. Blood 2000, 95, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meknache, N.; Jönsson, F.; Laurent, J.; Guinnepain, M.-T.; Daëron, M. Human Basophils Express the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Low-Affinity IgG Receptor FcγRIIIB (CD16B). J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosaki, T.; Gander, I.; Wirthmueller, U.; Ravetch, J.V. The beta subunit of the Fc epsilon RI is associated with the Fc gamma RIII on mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 1992, 175, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haas, M.; Kleijer, M.; Minchinton, R.M.; Roos, D.; Borne, A.E.v.D. Soluble Fc gamma RIIIa is present in plasma and is derived from natural killer cells. J. Immunol. 1994, 152, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, L.L.; Phillips, J.H.; Testi, R. Membrane anchoring and spontaneous release of CD16 (FcR III) by natural killer cells and granulocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1989, 19, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gessner, J.E. , et al., Separate promoters from proximal and medial control regions contribute to the natural killer cell-specific transcription of the human FcgammaRIII-A (CD16-A) receptor gene. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 30755–30764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, A.R.; Weigel, C.; Scoville, S.D.; Chan, W.K.; Chatman, K.; Nemer, M.M.; Mao, C.; Young, K.A.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; et al. Epigenetic and Posttranscriptional Regulation of CD16 Expression during Human NK Cell Development. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, W.H.; Teillaud, J.L.; Bouchard, C.; Teillaud, C.; Astier, A.; Tartour, E.; Galon, J.; Mathiot, C.; Sautès, C. Soluble Fc gamma receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 1993, 54, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Salle, C. , et al., Release of soluble Fc gamma RII/CD32 molecules by human Langerhans cells: a subtle balance between shedding and secretion? J Invest Dermatol 1992, 99, 15s–17s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodman-Smith, K.B. , et al., C-reactive protein-mediated phagocytosis and phospholipase D signalling through the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin G (FcgammaRI). Immunology 2002, 107, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhns, P.; Iannascoli, B.; England, P.; Mancardi, D.A.; Fernandez, N.; Jorieux, S.; Daëron, M. Specificity and affinity of human Fcγ receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood 2009, 113, 3716–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaev, S. , et al., The structure of a human type III Fcgamma receptor in complex with Fc. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 16469–16477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, T. Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wines, B.D.; Powell, M.S.; Parren, P.W.H.I.; Barnes, N.; Hogarth, P.M. The IgG Fc Contains Distinct Fc Receptor (FcR) Binding Sites: The Leukocyte Receptors FcγRI and FcγRIIa Bind to a Region in the Fc Distinct from That Recognized by Neonatal FcR and Protein A. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 5313–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geuijen, K.P.M.; Oppers-Tiemissen, C.; Egging, D.F.; Simons, P.J.; Boon, L.; Schasfoort, R.B.M.; Eppink, M.H.M. Rapid screening of IgG quality attributes – effects on Fc receptor binding. FEBS Open Bio 2017, 7, 1557–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Marnell, L.L.; Marjon, K.D.; Mold, C.; Du Clos, T.W.; Sun, P.D. Structural recognition and functional activation of FcγR by innate pentraxins. Nature 2008, 456, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberman, R.B.; Djeu, J.Y.; Kay, H.D.; Ortaldo, J.R.; Riccardi, C.; Bonnard, G.D.; Holden, H.T.; Fagnani, R.; Santoni, A.; Puccetti, P. Natural Killer Cells: Characteristics and Regulation of Activity. Immunol. Rev. 1979, 44, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, S.; Rosse, W.; Kurlander, R. Characterization of the igg-fc receptor on human-platelets. Blood 1982, 60, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H. , et al., Characterization and function of T cell Fc gamma receptor. Immunol Rev 1981, 56, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I Connor, R.; Shen, L.; Fanger, M.W. Evaluation of the antibody-dependent cytotoxic capabilities of individual human monocytes. Role of Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII and the effects of cytokines at the single cell level. . J. Immunol. 1990, 145, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, R.F.; Fanger, M.W. Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII on monocytes and granulocytes are cytotoxic trigger molecules for tumor cells. J. Immunol. 1987, 139, 3536–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnault, A. , et al., Fcgamma receptor-mediated induction of dendritic cell maturation and major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen presentation after immune complex internalization. J Exp Med 1999, 189, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett-Torabi, E.; Fantone, J.C. Soluble and insoluble immune complexes activate human neutrophil NADPH oxidase by distinct Fc gamma receptor-specific mechanisms. J. Immunol. 1990, 145, 3026–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, M.; Krauel, K. Human platelet IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIA in immunity and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 13, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, J.C.; Kimberly, R.P. Modulation of Fc gamma and complement receptor function by the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored form of Fc gamma RIII. J. Immunol. 1994, 152, 5826–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, D.; Shen, X.; Chen, J. Neutrophil CD16b crosslinking induces lipid raft-mediated activation of SHP-2 and affects cytokine expression and retarded neutrophil apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 362, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers, L.W.; van Houdt, M.; Bruggeman, C.W.; Heineke, M.H.; Zhao, X.W.; van der Heijden, J.; Nagelkerke, S.Q.; Verkuijlen, P.J.J.H.; Geissler, J.; Lissenberg-Thunnissen, S.; et al. FcγRIIIb Restricts Antibody-Dependent Destruction of Cancer Cells by Human Neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, K.; Kobayashi, D.; Hatoyama, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Takayanagi, R.; Yamada, Y. Effects of FCGRIIIa -158V/F polymorphism on antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity of adalimumab. APMIS 2017, 125, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, O.R.; Rosales, C. Human neutrophil Fc gamma receptors: different buttons for different responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 114, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousert, E.; Toes, R.; Desai, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Take the Central Stage in Driving Autoimmune Responses. Cells 2020, 9, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, P.; Baldini, C.; Rocchi, V.; Bombardieri, S. Anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibodies. Autoimmunity 2005, 38, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, Y. Anti-double Stranded DNA Antibodies: Origin, Pathogenicity, and Targeted Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, S.; Pearse, R.N.; Kurosaki, T.; Ravetch, J.V. SHIP Modulates Immune Receptor Responses by Regulating Membrane Association of Btk. Immunity 1998, 8, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, O.R. , et al., Transforming Growth Factor-β-Activated Kinase 1 Is Required for Human FcγRIIIb-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arepally, G.M. , Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 2017, 129, 2864–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.R.; Chava, S.; Taatjes-Sommer, H.S.; Meagher, S.; Brummel-Ziedins, K.E.; Schneider, D.J. Variation in platelet expression of FcγRIIa after myocardial infarction. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2019, 48, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, J.; Leung, H.H.L.; Ahmadi, Z.; Yan, F.; Chong, J.J.H.; Passam, F.H.; Chong, B.H. Neutrophil activation and NETosis are the major drivers of thrombosis in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, A.E.; Roudbari, Z.; Alizadeh, A.; Sadeghi, B. Investigation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with integrating transcriptomics and genome wide association information. Gene 2019, 706, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioan-Facsinay, A. , et al., FcgammaRI (CD64) contributes substantially to severity of arthritis, hypersensitivity responses, and protection from bacterial infection. Immunity 2002, 16, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, B.Z.; Valdigem, G.; Coenen, M.J.; Zhernakova, A.; Franke, B.; Monsuur, A.; van Riel, P.L.; Barrera, P.; Radstake, T.R.; Roep, B.O.; et al. Association analysis of functional variants of the FcgRIIa and FcgRIIIa genes with type 1 diabetes, celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 2552–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, L.; el Bannoudi, H.; Jansen, D.T.S.L.; Kok, K.; Trynka, G.; Diogo, D.; Swertz, M.; Fransen, K.; Knevel, R.; Gutierrez-Achury, J.; et al. Association analysis of copy numbers of FC-gamma receptor genes for rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated phenotypes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 24, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sareneva, I. , et al., Linkage and association study of FcgammaR polymorphisms in celiac disease. Tissue Antigens 2009, 73, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigaki, K.; Sundgren, N.; Khera, A.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Mineo, C.; Shaul, P.W. Fcγ Receptors and Ligands and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbe, A.K.; Wang, W.; Goldberg, J.; Gallenberger, M.; Kim, K.; Carmichael, L.; Hess, D.; Mendonca, E.A.; Song, Y.; Hank, J.A.; et al. FCGR Polymorphisms Influence Response to IL2 in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfat, M.; Silverman, E.D.; Levy, D.M. Rituximab therapy has a rapid and durable response for refractory cytopenia in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2015, 24, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, K.R.; Kumar, A.; Keung, B.; DiCapua, D.B.; Grodinsky, E.; Patwa, H.S.; Stathopoulos, P.A.; Goldstein, J.M.; O’connor, K.C.; Nowak, R.J. Durability of the Rituximab Response in Acetylcholine Receptor Autoantibody–Positive Myasthenia Gravis. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelopoulos, M.; Andreadou, E.; Koutsis, G.; Koutoulidis, V.; Anagnostouli, M.; Katsika, P.; Evangelopoulos, D.; Evdokimidis, I.; Kilidireas, C. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders with rituximab using a maintenance treatment regimen and close CD19 B cell monitoring. A six-year follow-up. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 372, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Megía, M.; Casanova-Estruch, B.; Pérez-Miralles, F.; Ruiz-Ramos, J.; Alcalá-Vicente, C.; Poveda-Andrés, J. Clinical evaluation of rituximab treatment for neuromyelitis optica. Neurologia 2015, 30, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alldredge, B.D.; Jordan, A.D.; Imitola, J.; Racke, M.K. Safety and Efficacy of Rituximab: Experience of a Single Multiple Sclerosis Center. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 41, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, B.I.; El-Ayoubi, N.K.; Nicolas, J.; El Kouzi, Y.; Khoury, S.J.; Zeineddine, M.M. Safety and Efficacy of Rituximab in Multiple Sclerosis: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, V.; Joly, P. Rituximab in Pemphigus. Immunotherapy 2017, 10, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLillo, D.J.; Ravetch, J.V. Fc-Receptor Interactions Regulate Both Cytotoxic and Immunomodulatory Therapeutic Antibody Effector Functions. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clynes, R.A. , et al., Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med 2000, 6, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellsworth, J.L.; Maurer, M.; Harder, B.; Hamacher, N.; Lantry, M.; Lewis, K.B.; Rene, S.; Byrnes-Blake, K.; Underwood, S.; Waggie, K.S.; et al. Targeting Immune Complex-Mediated Hypersensitivity with Recombinant Soluble Human FcγRIA (CD64A). J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbach, P. , et al., High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin therapy of refractory, in particular idiopathic thrombocytopenia in childhood. Helv Paediatr Acta 1981, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mimoto, F. , et al., Engineered antibody Fc variant with selectively enhanced FcγRIIb binding over both FcγRIIa(R131) and FcγRIIa(H131). Protein Eng Des Sel 2013, 26, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosques, C.J.; Manning, A.M. Fc-gamma receptors: Attractive targets for autoimmune drug discovery searching for intelligent therapeutic designs. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mkaddem, S.; Benhamou, M.; Monteiro, R.C. Understanding Fc Receptor Involvement in Inflammatory Diseases: From Mechanisms to New Therapeutic Tools. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, Y.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Immunoglobulin G Resulting from Fc Sialylation. Science 2006, 313, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, M.; Arlen, P.M.; Tsang, K.Y. Potentiation of natural killer cells to overcome cancer resistance to NK cell-based therapy and to enhance antibody-based immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1275904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).