Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Risk of Bias Assessment

Results

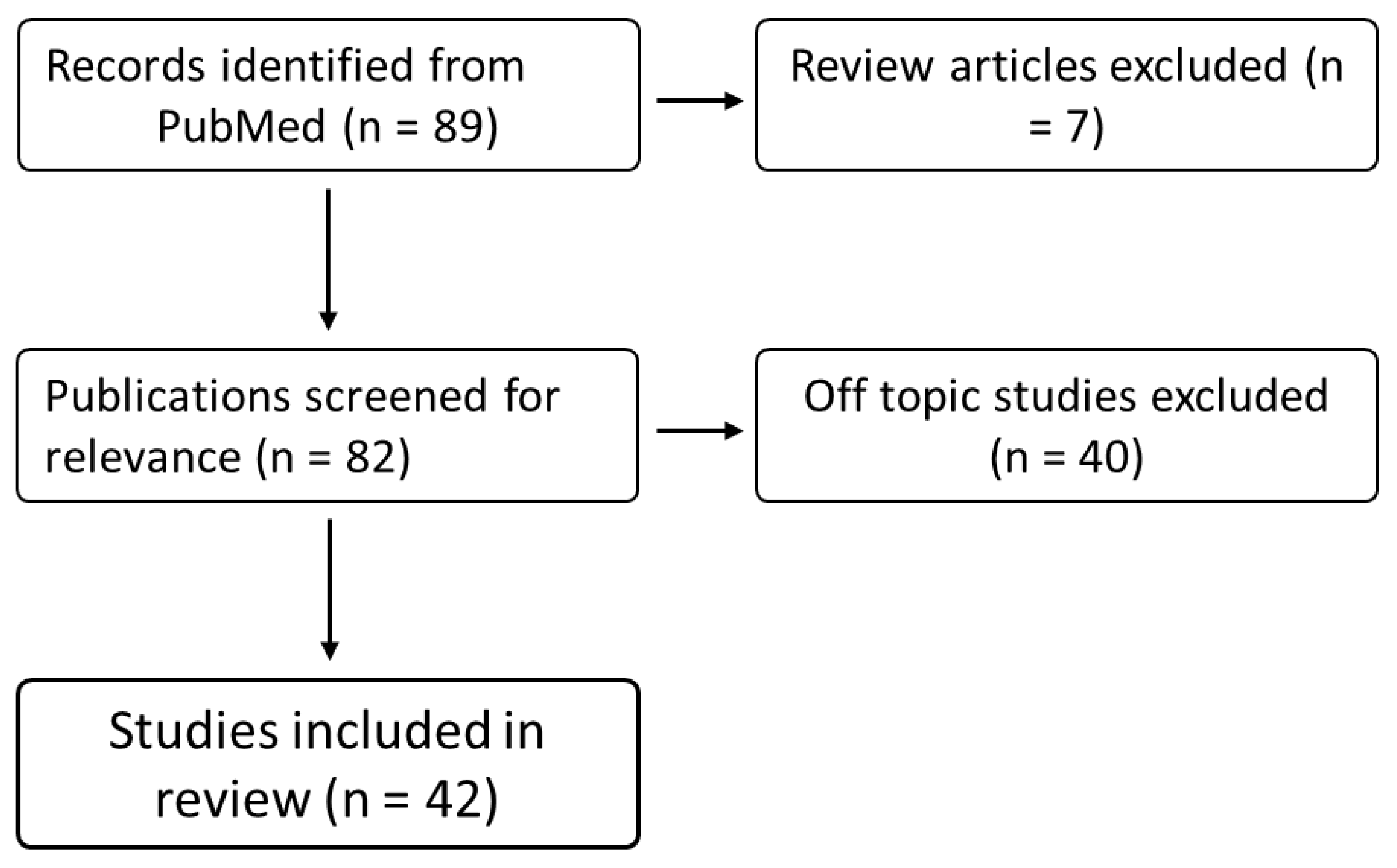

Study Selection

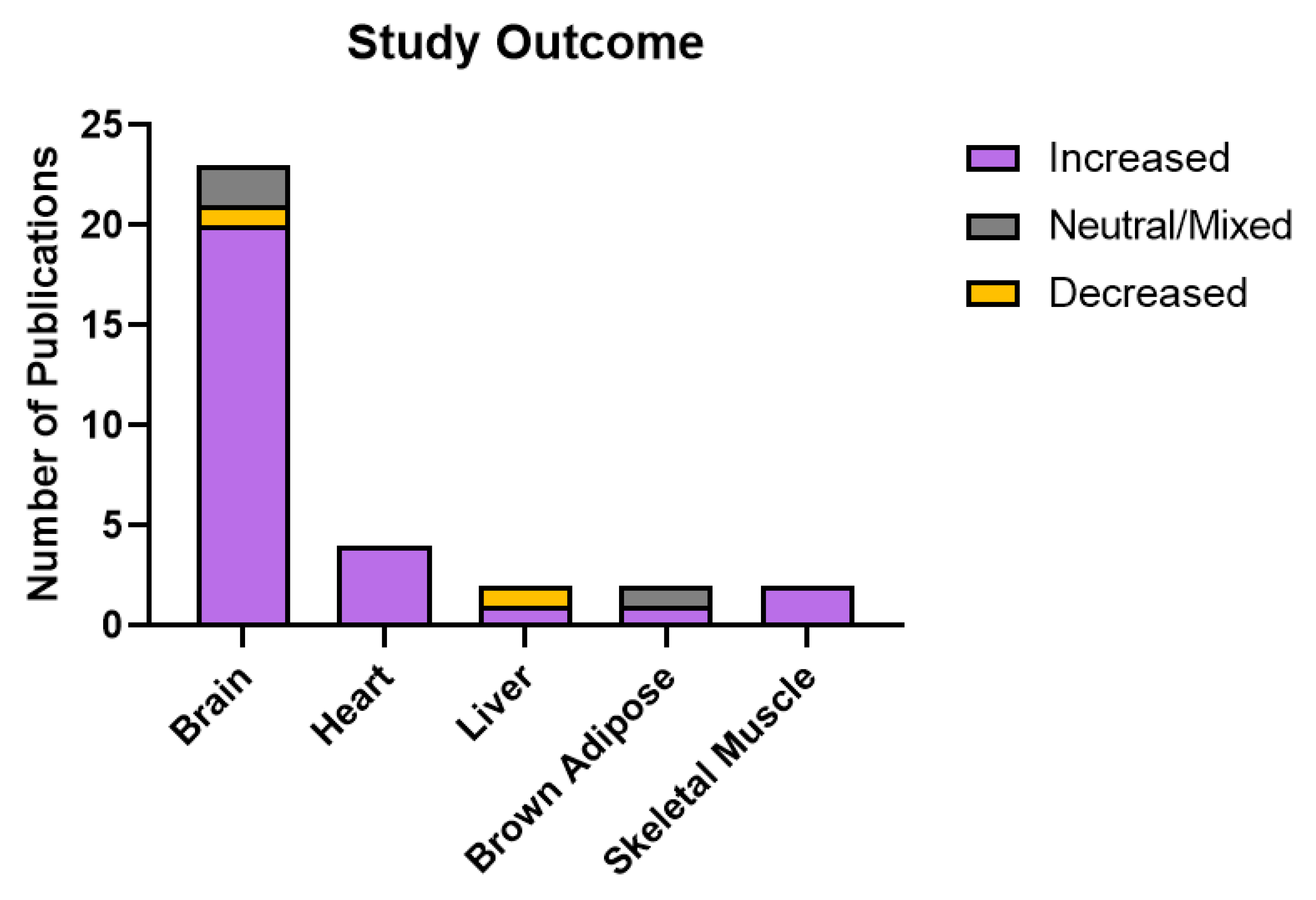

Study Outcomes Varied by Model

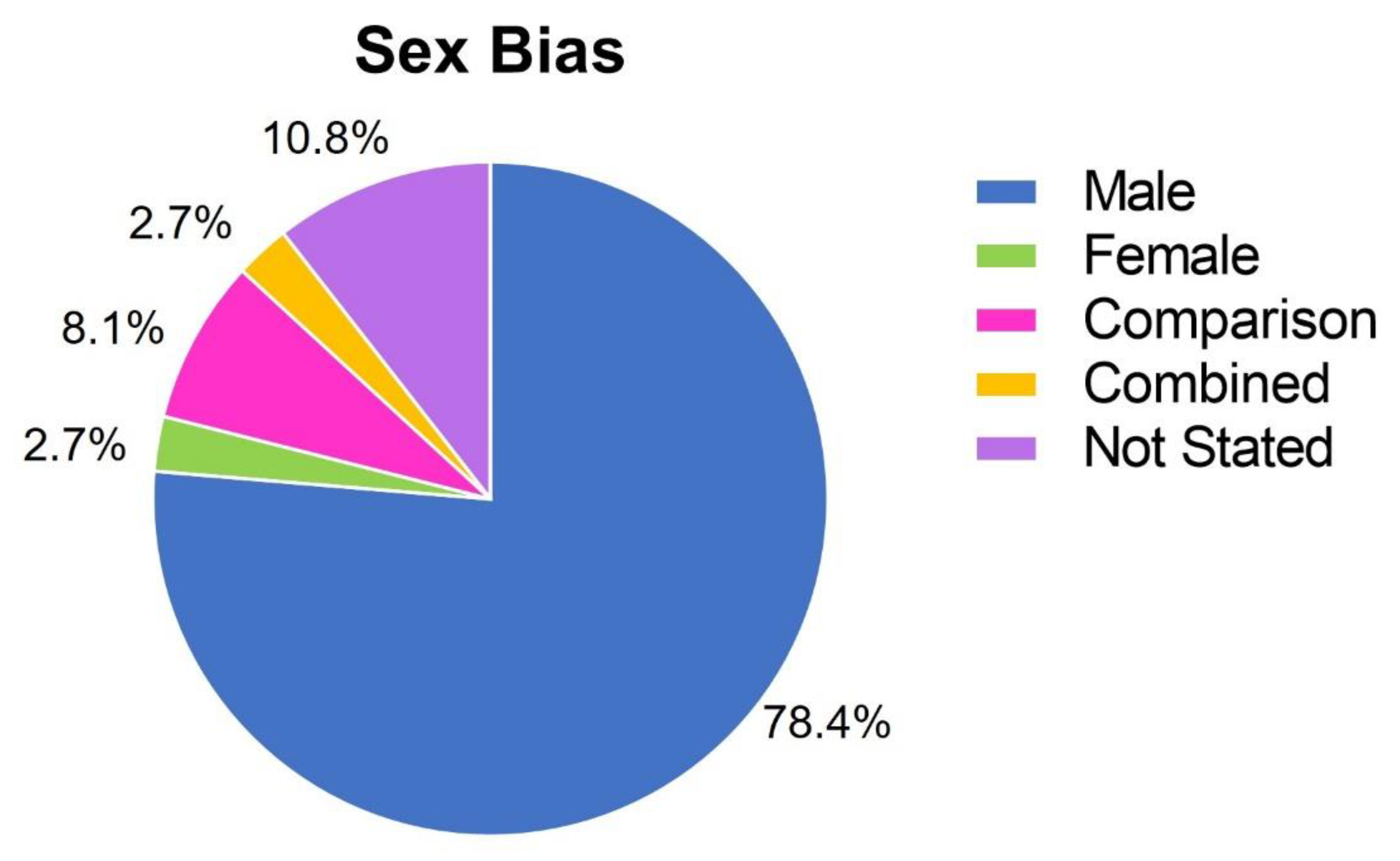

Publications Were Biased Towards Studying Males

SSRI Treatments in Isolated Mitochondria

Effects of SSRI Treatments on Cultured Cells

Paroxetine Treatments

Fluoxetine Treatments

Summarised Findings – Cells and Isolated Mitochondria

Summarised Findings – Animal Studies

Discussion

Animal Studies Were Most Relevant

Doses Were Variable

Non-SERT Related Effects of SSRIs

Sex Bias in the Literature

Author Contributions to the Field

Limitations

Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Razaq W, Kendall DA, Bates TE (2011) The effects of antidepressants on mitochondrial function in a model cell system and isolated mitochondria. Neurochem Res 36:327–338. [CrossRef]

- Adzic M, Lukic I, Mitic M, et al (2013) Brain region- and sex-specific modulation of mitochondrial glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation in fluoxetine treated stressed rats: Effects on energy metabolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38:2914–2924. [CrossRef]

- Adzic M, Mitic M, Radojcic M (2017) Mitochondrial estrogen receptors as a vulnerability factor of chronic stress and mediator of fluoxetine treatment in female and male rat hippocampus. Brain Res 1671:77–84. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian E, Eftekhari A, Fard JK, et al (2017) In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the mechanisms of citalopram-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch Pharm Res 40:1296–1313. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoairy R, Pedrini MT, Khan MI, et al (2017) Serotonin improves glucose metabolism by Serotonylation of the small GTPase Rab4 in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Diabetol Metab Syndr 9:1. [CrossRef]

- Arafat EA, Shabaan DA (2020) Fluoxetine ameliorates adult hippocampal injury in rats after early maternal separation. A biochemical, histological and immunohistochemical study. Biotech Histochem 95:55–68. [CrossRef]

- Bader M (2019) Serotonylation: Serotonin Signaling and Epigenetics. Front Mol Neurosci 12:288. [CrossRef]

- Bangasser DA, Cuarenta A (2021) Sex differences in anxiety and depression: circuits and mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bano S, Akhter S, Afridi MI (2004) Gender based response to fluoxetine hydrochloride medication in endogenous depression. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 14:161–165.

- Beery AK, Zucker I (2011) Sex Bias in Neuroscience and Biomedical Research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:565–572. [CrossRef]

- Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL (2009) The Expanded Biology of Serotonin. Annu Rev Med 60:355–366. [CrossRef]

- Braz GRF, da Silva AI, Silva SCA, et al (2020a) Chronic serotonin reuptake inhibition uncouples brown fat mitochondria and induces beiging/browning process of white fat in overfed rats. Life Sci 245:117307. [CrossRef]

- Braz GRF, Freitas CM, Nascimento L, et al (2016) Neonatal SSRI exposure improves mitochondrial function and antioxidant defense in rat heart. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41:362–369. [CrossRef]

- Braz GRF, Silva SC de A, Pedroza AA da S, et al (2020b) Fluoxetine administration in juvenile overfed rats improves hypothalamic mitochondrial respiration and REDOX status and induces mitochondrial biogenesis transcriptional expression. Eur J Pharmacol 881:173200. [CrossRef]

- Casarotto PC, Girych M, Fred SM, et al (2021) Antidepressant drugs act by directly binding to TRKB neurotrophin receptors. Cell 184:1299-1313.e19. [CrossRef]

- Charles E, Hammadi M, Kischel P, et al (2017) The antidepressant fluoxetine induces necrosis by energy depletion and mitochondrial calcium overload. Oncotarget 8:3181–3196. [CrossRef]

- Chen F, Danladi J, Ardalan M, et al (2018) A Critical Role of Mitochondria in BDNF-Associated Synaptic Plasticity After One-Week Vortioxetine Treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 21:603–615. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Owens GC, Crossin KL, Edelman DB (2007) Serotonin stimulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 36:472–483. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Margolis KJ, Gershon MD, et al (2012) Reduced serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) function causes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis independent of food intake. PloS One 7:e32511. [CrossRef]

- Coiro P, Pollak DD (2019) Sex and gender bias in the experimental neurosciences: the case of the maternal immune activation model. Transl Psychiatry 9:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Commons KG, Linnros SE (2019) Delayed Antidepressant Efficacy and the Desensitization Hypothesis. ACS Chem Neurosci 10:3048–3052. [CrossRef]

- da Silva AI, Braz GRF, Pedroza AA, et al (2015a) Fluoxetine induces lean phenotype in rat by increasing the brown/white adipose tissue ratio and UCP1 expression. J Bioenerg Biomembr 47:309–318. [CrossRef]

- da Silva AI, Braz GRF, Silva-Filho R, et al (2015b) Effect of fluoxetine treatment on mitochondrial bioenergetics in central and peripheral rat tissues. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab 40:565–574. [CrossRef]

- Daud FV, Murad N, Meneghini A, et al (2009) Fluoxetine effects on mitochondrial ultrastructure of right ventricle in rats exposed to cold stress. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 24:173–179. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira MR (2016) Fluoxetine and the mitochondria: A review of the toxicological aspects. Toxicol Lett 258:185–191. [CrossRef]

- Eid RS, Gobinath AR, Galea LAM (2019) Sex differences in depression: Insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Prog Neurobiol 176:86–102. [CrossRef]

- Emmerzaal TL, Jacobs L, Geenen B, et al (2021) Chronic fluoxetine or ketamine treatment differentially affects brain energy homeostasis which is not exacerbated in mice with trait suboptimal mitochondrial function. Eur J Neurosci 53:2986–3001. [CrossRef]

- Erb SJ, Schappi JM, Rasenick MM (2016) Antidepressants Accumulate in Lipid Rafts Independent of Monoamine Transporters to Modulate Redistribution of the G Protein, Gαs. J Biol Chem 291:19725–19733. [CrossRef]

- Fanibunda SE, Deb S, Maniyadath B, et al (2019) Serotonin regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and function in rodent cortical neurons via the 5-HT2A receptor and SIRT1-PGC-1 alpha axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:11028–11037. [CrossRef]

- Filipovic D, Costina V, Peric I, et al (2017) Chronic fluoxetine treatment directs energy metabolism towards the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation in rat hippocampal nonsynaptic mitochondria. Brain Res 1659:41–54. [CrossRef]

- Garabadu D, Ahmad A, Krishnamurthy S (2015) Risperidone Attenuates Modified Stress-Re-stress Paradigm-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis in Rats Exhibiting Post-traumatic Stress Disorder-Like Symptoms. J Mol Neurosci MN 56:299–312. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L (2003) The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:1002–1012. [CrossRef]

- Gerö D, Szoleczky P, Suzuki K, et al (2013) Cell-based screening identifies paroxetine as an inhibitor of diabetic endothelial dysfunction. Diabetes 62:953–964. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs WS, Collier JB, Morris M, et al (2018) 5-HT1F receptor regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and its loss potentiates acute kidney injury and impairs renal recovery. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315:F1119–F1128. [CrossRef]

- Głombik K, Stachowicz A, Trojan E, et al (2017) Evaluation of the effectiveness of chronic antidepressant drug treatments in the hippocampal mitochondria - A proteomic study in an animal model of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 78:51–60. [CrossRef]

- Haase J, Grudzinska-Goebel J, Muller HK, et al (2017) Serotonin Transporter Associated Protein Complexes Are Enriched in Synaptic Vesicle Proteins and Proteins Involved in Energy Metabolism and Ion Homeostasis. Acs Chem Neurosci 8:1101–1116. [CrossRef]

- Han YS, Lee CS (2009) Antidepressants reveal differential effect against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in differentiated PC12 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 604:36–44. [CrossRef]

- Hroudova J, Fisar Z (2010) Activities of respiratory chain complexes and citrate synthase influenced by pharmacologically different antidepressants and mood stabilizers. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 31:336–342.

- Jeong I, Yang JS, Hong YJ, et al (2017) Dapoxetine induces neuroprotective effects against glutamate-induced neuronal cell death by inhibiting calcium signaling and mitochondrial depolarization in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol 805:36–45. [CrossRef]

- Jeong J, Park M, Yoon JS, et al (2015) Requirement of AMPK activation for neuronal metabolic-enhancing effects of antidepressant paroxetine. Neuroreport 26:424–428. [CrossRef]

- Karson CN, Newton JE, Livingston R, et al (1993) Human brain fluoxetine concentrations. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 5:322–329. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy SH, Evans KR, Krüger S, et al (2001) Changes in regional brain glucose metabolism measured with positron emission tomography after paroxetine treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 158:899–905. [CrossRef]

- Khedr LH, Nassar NN, Rashed L, et al (2019) TLR4 signaling modulation of PGC1-α mediated mitochondrial biogenesis in the LPS-Chronic mild stress model: Effect of fluoxetine and pentoxiyfylline. Life Sci 239:116869. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Kumar A (2009) Possible role of sertraline against 3-nitropropionic acid induced behavioral, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunctions in rat brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33:100–108. [CrossRef]

- Kwatra M, Jangra A, Mishra M, et al (2016) Naringin and Sertraline Ameliorate Doxorubicin-Induced Behavioral Deficits Through Modulation of Serotonin Level and Mitochondrial Complexes Protection Pathway in Rat Hippocampus. Neurochem Res 41:2352–2366. [CrossRef]

- Lee CS, Kim YJ, Jang ER, et al (2010) Fluoxetine Induces Apoptosis in Ovarian Carcinoma Cell Line OVCAR-3 Through Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Activation of Nuclear Factor-κB. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 106:446–453. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Park A, Oh K-J, et al (2019) The Role of Adipose Tissue Mitochondria: Regulation of Mitochondrial Function for the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 20:4924. [CrossRef]

- LeGates TA, Kvarta MD, Thompson SM (2019) Sex differences in antidepressant efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology 44:140–154. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Couch L, Higuchi M, et al (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by sertraline, an antidepressant agent. Toxicol Sci 127:582–591. [CrossRef]

- Ludka FK, Dal-Cim T, Binder LB, et al (2017) Atorvastatin and Fluoxetine Prevent Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Evoked by Glutamate Toxicity in Hippocampal Slices. Mol Neurobiol 54:3149–3161. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães P, Alves G, Llerena A, Falcão A (2017) Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Fluoxetine, Norfluoxetine and Paroxetine: A New Tool Based on Microextraction by Packed Sorbent Coupled to Liquid Chromatography. J Anal Toxicol 41:631–638. [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi S, Sakagami H, Yabuki Y, et al (2015) Stimulation of Sigma-1 Receptor Ameliorates Depressive-like Behaviors in CaMKIV Null Mice. Mol Neurobiol 52:1210–1222. [CrossRef]

- Morrison SF, Madden CJ, Tupone D (2014) Central neural regulation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and energy expenditure. Cell Metab 19:741–756. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee J, Das MK, Yang ZY, Lew R (1998) Evaluation of the binding of the radiolabeled antidepressant drug, F-18-fluoxetine in the rodent brain: An in vitro and in vivo study. Nucl Med Biol 25:605–610. [CrossRef]

- Muma NA, Mi Z (2015) Serotonylation and Transamidation of Other Monoamines. ACS Chem Neurosci 6:961–969. [CrossRef]

- Naoi M, Riederer P, Maruyama W (2016) Modulation of monoamine oxidase (MAO) expression in neuropsychiatric disorders: genetic and environmental factors involved in type A MAO expression. J Neural Transm 123:91–106. [CrossRef]

- Ni W, Watts SW (2006) 5-Hydroxytryptamine in the Cardiovascular System: Focus on the Serotonin Transporter (sert). Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 33:575–583. [CrossRef]

- Overø KF (1982) Kinetics of citalopram in man; plasma levels in patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 6:311–318. [CrossRef]

- Peric I, Costina V, Stanisavljevic A, et al (2018) Proteomic characterization of hippocampus of chronically socially isolated rats treated with fluoxetine: Depression-like behaviour and fluoxetine mechanism of action. Neuropharmacology 135:268–283. [CrossRef]

- Reddy AP, Sawant N, Morton H, et al (2021) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram ameliorates cognitive decline and protects against amyloid beta-induced mitochondrial dynamics, biogenesis, autophagy, mitophagy and synaptic toxicities in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 30:789–810. [CrossRef]

- Scaini G, Santos PM, Benedet J, et al (2010) Evaluation of Krebs cycle enzymes in the brain of rats after chronic administration of antidepressants. Brain Res Bull 82:224–227. [CrossRef]

- Scholpa NE, Lynn MK, Corum D, et al (2018) 5-HT1F receptor-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Br J Pharmacol 175:348–358. [CrossRef]

- Shu X, Sun Y, Sun X, et al (2019) The effect of fluoxetine on astrocyte autophagy flux and injured mitochondria clearance in a mouse model of depression. Cell Death Dis 10:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Silva TLA, Braz GRF, Silva SC de A, et al (2018) Serotonin transporter inhibition during neonatal period induces sex-dependent effects on mitochondrial bioenergetics in the rat brainstem. Eur J Neurosci 48:1620–1634. [CrossRef]

- Simmons EC, Scholpa NE, Cleveland KH, Schnellmann RG (2019) 5-HT1F Receptor Agonist Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Promotes Recovery from Spinal Cord Injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. [CrossRef]

- Simões-Alves AC, Silva-Filho RC, Braz GRF, et al (2018) Neonatal treatment with fluoxetine improves mitochondrial respiration and reduces oxidative stress in liver of adult rats. J Cell Biochem 119:6555–6565. [CrossRef]

- Sonei N, Amiri S, Jafarian I, et al (2017) Mitochondrial dysfunction bridges negative affective disorders and cardiomyopathy in socially isolated rats: Pros and cons of fluoxetine. World J Biol Psychiatry 18:39–53. [CrossRef]

- Steiner JP, Bachani M, Wolfson-Stofko B, et al (2015) Interaction of Paroxetine with Mitochondrial Proteins Mediates Neuroprotection. Neurotherapeutics 12:200–216. [CrossRef]

- Tagashira H, Bhuiyan MS, Shioda N, Fukunaga K (2014) Fluvoxamine rescues mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and ATP production through σ(1)-receptor in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. Life Sci 95:89–100. [CrossRef]

- Tempio A, Niso M, Laera L, et al (2020) Mitochondrial Membranes of Human SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells Express Serotonin 5-HT7 Receptor. Int J Mol Sci 21:. [CrossRef]

- Thorne BN, Ellenbroek BA, Day DJ (2022a) Sex bias in the serotonin transporter knockout model: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorder research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 134:. [CrossRef]

- Thorne BN, Ellenbroek BA, Day DJ (2022b) The serotonin reuptake transporter modulates mitochondrial copy number and mitochondrial respiratory complex gene expression in the frontal cortex and cerebellum in a sexually dimorphic manner. J Neurosci Res 100:869–879. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al (2006) Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 163:28–40. [CrossRef]

- Tutakhail A, Nazari QA, Khabil S, et al (2019) Muscular and mitochondrial effects of long-term fluoxetine treatment in mice, combined with physical endurance exercise on treadmill. Life Sci 232:116508. [CrossRef]

- Valenti D, de Bari L, Vigli D, et al (2017) Stimulation of the brain serotonin receptor 7 rescues mitochondrial dysfunction in female mice from two models of Rett syndrome. Neuropharmacology 121:79–88. [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Clapier R, Moulin M, Piquereau J, et al (2017) Mitochondria: a central target for sex differences in pathologies. Clin Sci Lond 131:803–822. [CrossRef]

- Videbech P (2000) PET measurements of brain glucose metabolism and blood flow in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101:11–20. [CrossRef]

- Villa RF, Ferrari F, Bagini L, et al (2017) Mitochondrial energy metabolism of rat hippocampus after treatment with the antidepressants desipramine and fluoxetine. Neuropharmacology 121:30–38. [CrossRef]

- Villa RF, Ferrari F, Gorini A, et al (2016) Effect of desipramine and fluoxetine on energy metabolism of cerebral mitochondria. Neuroscience 330:326–334. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Zhang H, Xu H, et al (2016) 5-HTR3 and 5-HTR4 located on the mitochondrial membrane and functionally regulated mitochondrial functions. Sci Rep 6:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wen L, Jin Y, Li L, et al (2014) Exercise prevents raphe nucleus mitochondrial overactivity in a rat depression model. Physiol Behav 132:57–65. [CrossRef]

- Woitowich NC, Beery A, Woodruff T (2020) A 10-year follow-up study of sex inclusion in the biological sciences. eLife 9:e56344. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (2021) WHO model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021).

| Domain | Concern | Rationale for Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Concerns regarding specification of study eligibility criteria |

Year of publication, language | Scientific studies published outside of the date range or in languages other than English may have been missed. |

| Concerns regarding methods used to identify and/or select studies |

Database Search | It is possible that the database searched did not contain an exhaustive list of the published literature in this field. |

| Concerns regarding methods used to collect data and appraise studies |

Single author review | Studies were identified and reviewed twice by one author, and this may have resulted in bias and/or error. |

| Concerns regarding the synthesis and findings |

Primary study quality and bias; diversity of methods used in primary studies. | Primary studies were not classified based on methodological robustness – each study was equally weighted with regard to findings. Primary studies used a wide variety of methods to determine mitochondrial function |

| Model/Sex | Treatment | Findings | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pig brain mitochondria | 500 μM Citalopram | ↓ Citalopram inhibited complex I and II activity. | (Hroudova and Fisar 2010) |

| Rat heart mitochondria, CHOβ2SPAP cells | 10-50 μM Norfluoxetine | ↓ Norfluoxetine caused a decrease in MMP, complex I/II/III/IV activity and reduced O2 consumption. Effects were in cells and isolated mitochondria. | (Abdel-Razaq et al. 2011) |

| Primary rat hepatocytes; isolated liver mitochondria/Male | 12.5-100 μM Sertraline; 0.5 - 24 hours | ↓ Sertraline impaired complex I and ATP synthase but not other ETC complexes; uncoupled OXPHOS in mitochondria. Showed ATP depletion in cells. | (Li et al. 2012) |

| Rat primary hippocampal neuron cultures/ Male |

3 μM Fluoxetine | ↔ Treatment promoted anterograde axonal transport of mitochondria in hippocampal neurons. | (Chen et al. 2007) |

| PC12 Cells | 15 μM Fluoxetine, 24 hours | ↓ Fluoxetine had an additive effect with rotenone and MPP+ toxicity. Induced mitochondrial membrane permeability change and oxidative stress. Reduced cell viability. | (Han and Lee 2009) |

| OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 Cells | 15 μM Fluoxetine, 24 hours | ↓ Treatment induced activation of apoptotic proteins, cell death, ROS formation, loss of MMP, and cytochrome c release. | (Lee et al. 2010) |

| bEnd.3 and EA.hy926 Cells | 10 μM Paroxetine, 3 days | ↑ Paroxetine reduced hyperglycaemia-induced mitochondrial ROS formation, DNA damage, and protein oxidation without influencing electron transport or cellular bioenergetics. | (Gerö et al. 2013) |

| SK-N-MC Cells | 2-10 μM Paroxetine | ↑ Dose-dependent increase in mitochondrial biogenesis, mtDNA copy number, TFAM/PGC1a mRNA expression, ATP levels, and glucose uptake. | (Jeong et al. 2015) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rat, SERT Knockout mouse, human primary neuronal cultures; Sprague Dawley Rats | 0.01-10 μM Paroxetine/ Fluoxetine; 10 mg/kg, 10 or 28 days |

↑ SSRIs identified as protective against oxidative stress. Paroxetine and fluoxetine protected against Tat-induced neurotoxicity (paroxetine to a greater extent). Paroxetine stimulated proliferation of NPCs and generation of newborn neurons. Inhibited Ca2+-induced swelling in brain mitochondria. | (Steiner et al. 2015) |

| Jurkat and HeLa Cells; Patient PBMCs | 40 μM Fluoxetine | ↓ Decreased oxygen consumption, ATP content with fluoxetine treatment. | (Charles et al. 2017) |

| Rat primary hippocampal neuron cultures/Not Stated | 5 μM Dapoxetine, Fluoxetine, Citalopram | ↑ Dapoxetine treatment inhibited glutamate-induced Ca2+ increase, mitochondrial depolarisation, and cell death. Effects of citalopram and fluoxetine less pronounced. | (Jeong et al. 2017) |

| HT22 Cells | 20 μM Citalopram | ↑ Citalopram treatment enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy in HT22 cells. Treatment restored impaired mitochondrial dynamics in cells transfected with mutant APP. | (Reddy et al. 2021) |

| Model/Sex | Treatment | Findings | Study |

| Wistar rats/ Male |

0.75 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 40 days | *↑ Fluoxetine prevented mitochondrial cristolysis in the heart under cold stress. | (Daud et al. 2009) |

| Wistar rats/ Male |

5, 10 mg/kg Sertraline, 14 days | *↑ Sertraline normalised electron transport complex activity and oxidative stress in the brains of a rat model of Huntington’s Disease. | (Kumar and Kumar 2009) |

| Wistar rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Paroxetine, 15 days | ↑ Paroxetine treatment increased citrate synthase and succinate dehydrogenase activity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, but not the cerebellum. | (Scaini et al. 2010) |

| Wistar rats/Male and Female | 5 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↓↑ Males and females respond differently to fluoxetine treatment following chronic stress. ETC complex IV mRNA expression and activity were altered depending on sex, treatment, and brain region. | (Adzic et al. 2013) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats/Male | 5 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 18 days | *↓ Chronic unpredictable stress resulted in increased ATP production and antioxidant defence in the DRN. Changes were normalised by exercise and fluoxetine treatment. | (Wen et al. 2014) |

| ICR Mice/Wistar Rat primary cardiomyocyte cultures | 1 mg/kg Fluvoxamine, 4 weeks; 5 μM in culture | *↑ Fluvoxamine treatment rescued ATP production in the hearts of mice that had undergone transverse aortic constriction. A similar effect was seen in cultured rat primary cardiomyocytes, whereby fluvoxamine treatment rescued Ca2+ mobilisation and ATP production in cardiomyocytes treated with angiotensin II to promote hypertrophy. | (Tagashira et al. 2014) |

| CaMKIV Null Mice/Male | 2.5 mg/kg Fluvoxamine, 1 mg/kg Paroxetine, 14 days | *↑ Fluvoxamine normalised ATP production in the hippocampus of CaMKIV null mice. Suggested that these changes were attributed to the sigma-1 receptor rather than altered serotonergic signalling, as treatment with paroxetine, an SSRI lacking sigma-1 receptor affinity, did not show the same effects. | (Moriguchi et al. 2015) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, first 21 days of life | ↑ Increased O2 consumption and citrate synthase activity, reduced ROS production in skeletal muscle and hypothalamus with fluoxetine treatment at adulthood. | (da Silva et al. 2015b) |

| Charles Foster Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Paroxetine, 24 days | *↑ Paroxetine ameliorated stress-induced oxidative damage in the brain; no effect on OXPHOS. | (Garabadu et al. 2015) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, first 21 days of life | ↑ Fluoxetine increased mitochondrial respiration and proton leak increased expression of UCP1, decreased ROS production in brown adipose tissue at adulthood. | (da Silva et al. 2015a) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg fluoxetine, first 21 days of life | ↑ Neonatal fluoxetine treatment increased mitochondrial respiratory capacity and membrane potential and decreased ROS production in the heart at adulthood. | (Braz et al. 2016) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Enhanced complex IV activity in non-synaptic mitochondria and synaptic “heavy” mitochondria isolated from the FC of rats. | (Villa et al. 2016) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 5 mg/kg Sertraline | *↑ Combined sertraline and narinign treatment restored mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the hippocampus following doxorubicin exposure. | (Kwatra et al. 2016) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rat Hepatocytes/ Not Stated |

20 mg/kg in rats; 500 μM Citalopram in isolated hepatocytes | ↓ In vivo experiments showed that treatment caused oxidative damage in the liver, and in vitro experiments showed that this dose caused oxidative damage and collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential. | (Ahmadian et al. 2017) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Enhanced complex IV, succinate dehydrogenase, and glutamate dehydrogenase activity non-synaptic mitochondria isolated from the hippocampus of rats. | (Villa et al. 2017) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 7.5 mg/kg Fluoxetine | *↑ Treatment rescued decreased complex II activity in the brains and hearts of rats affected by social isolation stress. Oxidative damage, collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, and reduced ATP production were rescued in the brains only. | (Sonei et al. 2017) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 15 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Fluoxetine upregulated mitochondrial proteins related to OXPHOS and TCA cycle in the hippocampus. Upregulation of subunits for complexes I, II and III and ATP synthase. | (Filipovic et al. 2017) |

| Swiss Mice/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine (1 dose for acute, 7 days for chronic) | *↑ Chronic but not acute treatment was protective against oxidative stress and collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential due to glutamate excitotoxicity in the hippocampus. | (Ludka et al. 2017) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑↓ Proteomic study – upregulation and downregulation of a variety of proteins involved with mitochondrial dynamics, function, and maturation in the hippocampus with fluoxetine treatment. | (Głombik et al. 2017) |

| Wistar Rats/Male and Female | 5 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Fluoxetine treatment increased complex IV activity in the hippocampus of control males and stressed females. | (Adzic et al. 2017) |

| Sprague-Dawley Rats/Male | Vortioxetine 1.6 g/kg in food, Fluoxetine 160 mg/L in drinking water, 7 days | ↑ Vortioxetine treatment increased number of mitochondria in total neuropil and axon terminals in the hippocampus. No change with fluoxetine treatment. | (Chen et al. 2018) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 15 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | *↑ Fluoxetine treatment restored decreased expression of proteins involved with mitochondrial transport, Krebs cycle, and OXPHOS in the hippocampus following chronic stress. | (Peric et al. 2018) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, first 21 days of life | ↑ Increased oxygen consumption in the livers of fluoxetine treated animals at adulthood, reduced oxidative stress. Increased resistance to mPTP opening. | (Simões-Alves et al. 2018) |

| Wistar Rats/Male and Female | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Improved mitochondrial bioenergetics in the brainstem of fluoxetine treated males, improved antioxidant defence in the brainstem of treated females. | (Silva et al. 2018) |

| BALB/cJ Mice/Male | 18 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 6 weeks | ↑ Increased citrate synthase and complex IV activity and decreased ROS production in skeletal muscle in fluoxetine treated, exercising mice. | (Tutakhail et al. 2019) |

| C57/BL6J Mice/Male; primary cultured astrocytes | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 28 days; 10 μM in culture | *↑ Mitochondrial structure in the hippocampus disrupted following stress, restored with fluoxetine. Treatment also promoted mitophagy in primary astrocytes. | (Shu et al. 2019) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 30 days | *↑ Fluoxetine ameliorated reduced mtDNA copy number and mRNA expression of Ppargc1a, Tfam, Nrf1 in the hippocampus of stressed animals. | (Khedr et al. 2019) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑↓ Fluoxetine treatment (PND 39-59) resulted in increased oxygen consumption and decreased oxidative damage in brown adipose tissue of rats overfed as neonates. In normofed rats, oxygen consumption was also increased with fluoxetine treatment, but there was increased oxidative damage. | (Braz et al. 2020a) |

| Albino Rats/Male | 5 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 7 days | *↑ Fluoxetine ameliorated ultrastructural changes to mitochondria in the hippocampus of pups exposed to maternal separation stress. | (Arafat and Shabaan 2020) |

| Wistar Rats/Male | 10 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | ↑ Fluoxetine administration (PND 39-59) in rats overfed as neonates restored mitochondrial function, oxidative balance, and mitochondrial biogenesis in the hypothalamus. | (Braz et al. 2020b) |

| Ndufs4GT/GT Mice/Male | 15 mg/kg Fluoxetine, 21 days | *↓ Fluoxetine treatment reduced complex III and IV activity in the FC following chronic unpredictable stress. | (Emmerzaal et al. 2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).