1. Introduction

In aquaculture, some studies show that the use of butyric acid offers several possibilities, with results indicating an increase in growth, a reduction in stress, an enhancement of digestive capacity and function, and higher survival rates [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The bioavailability of butyric acid varies significantly depending on its form, as demonstrated by research across different contexts. Butyric acid is utilized in various forms, including salts, coated salts, and glycerides, each with distinct bioavailability and effectiveness profiles [

7].

Based on this, protected sodium butyrate (PSB) has been identified as a promising dietary supplement for

Penaeus vannamei, offering several health benefits, particularly in terms of modulating gut microbiota and enhancing immune responses. PSB's effect on

Penaeus vannamei, commonly known as white-leg shrimp, has been extensively studied, revealing its impact on growth performance, intestinal microbiota, immunological parameters, and survival rates. Research indicates that sodium butyrate supplementation in shrimp diets can enhance survival and productivity by modulating the immune system and reducing the concentration of pathogenic bacteria in the gut, thereby improving overall health and resistance to diseases such as

Vibrio alginolyticus [

8,

9].

Research has demonstrated that sodium butyrate has the potential to enhance intestinal health and morphology, which are essential for nutrient absorption and overall growth performance in aquatic species [

1,

3,

4,

6,

10,

11]. For example, dietary supplementation with sodium butyrate was found to mitigate growth reduction and enteritis in fish by promoting the activities of intestinal digestive enzymes, decreasing mucosal permeability, and attenuating the intestinal inflammatory response. These findings may also be applicable to shrimp species, such as

Penaeus vannamei [

12].

Sodium butyrate supplementation has been linked to enhanced feed efficiency and growth performance in shrimp. This is evident in a study conducted by [

13,

14], where shrimp fed diets fortified with sodium butyrate demonstrated increased final weight compared to control groups. Moreover, sodium butyrate has been shown to elevate the populations of beneficial lactic acid bacteria in the intestines, while having no impact on the counts of Vibrio spp. or total heterotrophic bacteria. These findings suggest that sodium butyrate plays a vital role in promoting a well-functioning gut microbiome, as highlighted in a study by [

15].

PSB has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of the immune system in Penaeus vannamei, thereby becoming a valuable tool for managing health in shrimp farming. However, it is important to note that the benefits of PSB are specific and distinct from those of other organic acid salts. While PSB offers advantages in terms of gut health and immune response, other salts may not yield the same level of benefit in these areas. An example of this can be seen in a study conducted by [

16], where the effects of different forms of artificially salinized water on zootechnical performance and bacterial counts in

Penaeus vannamei juveniles did not directly correlate to the specific benefits attributed to PSB. This highlights the unique role that PSB plays in aquaculture nutrition. In summary, PSB serves as a valuable dietary supplement for Penaeus vannamei, bolstering survival, growth, and health by specifically modulating the gut microbiota and enhancing immune responses. These benefits distinguish PSB from other organic acid salts, as demonstrated in studies by [

12,

15,

17,

18]. Furthermore, a study by [

11] investigating the effects of butyric acid on juvenile Pacific shrimp (

P. vannamei) revealed that dietary inclusion of butyric acid significantly improved survival rates during heat stress. Specifically, shrimp supplemented with 1.5% of this acid exhibited no mortality, indicating a protective effect against heat-induced stress. In addition, this supplementation led to improved immune responses, as evidenced by increased activities of alkaline phosphatase (AKP) and acid phosphatase (ACP), as well as enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD).

Contrastingly, research on various organic acids and their salts, such as benzoic acid, has demonstrated negative effects on the well-being of shrimp, indicating that not all organic additives have advantageous effects on

Penaeus vannamei [

19,

20]. This emphasizes the distinctiveness of sodium butyrate's beneficial role in shrimp aquaculture, setting it apart from other organic acid supplements. However, it is important to note that while sodium butyrate offers multiple advantages, its efficacy can vary based on the concentration utilized and the specific parameters of health or growth being assessed [

9]. In summary, sodium butyrate serves as a valuable dietary supplement for Penaeus vannamei, fostering improved survival, growth, and well-being by modulating the gut microbiota and enhancing immune responses, although its benefits are specific and divergent from other organic acid salts.

The aim was to evaluate the effect of three levels of buffer- PSB in the diet of Penaeus vannamei shrimp during the nursery, pre-grow, and grow-out phases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Local, and Experimental Design

The investigation is being undertaken at the Animal Sciences Department of the Federal University of Rural Semi-Arid Region (UFERSA), located in Mossoró, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. The water utilized for cultivation is derived from an artesian well characterized by low salinity levels, specifically 3 ppt.

The experimental design was structured as a completely randomized design. The study followed a completely randomized design, with treatments including four levels of PSB (54% sodium butyrate) (0, 2, 4, and 8 kg/t). The cohort of post-larvae (JH Pós-Larvas, Aracati, CE, Brazil | SPF larvae) was subjected to evaluation under three stressors: salinity, temperature, and nitrite lethal dose (DL70), to determine the quality of the larvae before their experimental stocking. PSB was supplied by Novation SL 2002 (Spain, Europe), which contains 54% sodium butyrate that is protected by a physical and chemical matrix composed of buffer salts.

After confirming the quality of post-larvae, the animals were acclimated in a 20m3 geomembrane tank for 19 days (PL11 to PL30, 10 PL/g). After the acclimatization and growth period of the post-larvae, the animals were weighed, the average weight was obtained, and batches were organized for experimental unit homogeneity. The initial weight of the post-larvae was 93.18 ± 1.617 mg. The initial mean length was 25.06 ± 0.414 mm.

2.2. Nursery Phase | Experimental Diets

To start the experimental diets in this period, the post-larvae (PL30) were housed in blue polypropylene tanks with a capacity of 500L (0.5m3), equipped with independent aeration and water supply systems. Each experimental unit contained a feeding tray (47.5cm in diameter, 8.7cm in height, in black color) installed in each experimental unit.

The diets used in this phase of the study were formulated with 37% Crude protein, 1.3% Fat, 0.3% Fiber, 1.4% Ash, 12.35% Fish Meal (FM)), supplemented with additives according to the description of the evaluated treatments and levels. The provided feed had particle sizes ranging from 600 to 800 μm (Exteex 500x, SP, Brazil). The treatments in Phase 1 were organized as follows crescent levels of PSB (0, 2, 4, and 8kg/t). The PSB was applied in the feed using 1% soybean oil as a diluent, ontop adjusted to the oil level of the diet, sprayed, and dry to use. Each treatment was replicated 4 times, except for the Control which was replicated 8 times with 160 shrimp/replicate.

2.3. Growth Phase | Experimental Diets

After the nursery phase, a total of 75 juveniles from each repetition per treatment from the Nursery Phase were captured, weighed, and transferred to hapas with nylon multifilament-coated PVC mesh net pens with a 5mm mesh size and a useful volume of 1m³, constituting the evaluated animals in Phase 2. The initial average weight was 792.59 ± 57.29 mg/shrimp.

The feeding will consist of pellets ranging from 1.5 to 2mm. The feed will be provided in feeding trays (47.5cm in diameter, 8.7cm in height, in black color) installed in each experimental unit. After 1 hour and 30 minutes, any remaining feed will be collected, dried, and weighed to adjust the feed conversion ratio (FCR). The diets were formulated according to the nutritional requirements of the evaluated animals,

Table 1. The PSB was applied to the feed using 1% soybean oil as a diluent. The levels evaluated in this phase were the same as in the nursery phase: 0, 2, 4, and 8 kg/ton of PSB.

2.4. Water Parameters

During the period of the shrimp experiment, various dietary regimens were administered while multiple aquatic parameters were systematically observed. These parameters comprised pH (Hydrogen Ion Concentration); conductivity (µS/cm); salinity (parts per million, ppm); temperature, documented in degrees Celsius (°C); dissolved oxygen (DO, mg/L); total dissolved solids (TDS, mg/L); ammonia, quantified in milligrams per liter (mg/L); and nitrite, similarly evaluated in milligrams per liter (mg/L), as delineated in

Table 2.

2.5. Performance Data

In the nursery phase, after 35 days, the animals were captured, counted, and weighed to determine live weight data (g/shrimp), weight gain (g/shrimp), feed intake (g/shrimp), and feed conversion ratio (g/g).

In the Growth phase, every two weeks, animals were captured from 20% of the initial biomass for weighing and obtaining the same productive performance parameters indicated for the nursery phase at the end of the 90-day cultivation period, all animals were collected, weighed, and counted to obtain performance data including survival data. Survival was obtained by calculating the difference between the beginning and end of the experimental period, recording any detected deaths, and weighing and counting the animals at the end. At the end of the experiment, 30 shrimp per treatment had their length measured and were individually weighed. The head and carapace were removed to obtain data on headless shrimp yield (Shrimp, %), and fillet yield (Meat, %).

2.6. Hematological Analysis

A total of 300 microliters of anticoagulant solution were added to the collection syringe. The ventral sinus was disinfected with 70% alcohol, and the shrimp was positioned with the ventral side facing up. 100 microliters of hemolymph were extracted from the area between the first abdominal segment and the cephalothorax. The hemolymph was thoroughly mixed with the anticoagulant and transferred to a labeled Eppendorf tube. The mixture was then stored in the refrigerator until counting could be done. Before counting, 20 microliters of rose Bengal were added to the sample and homogenized. After 20 minutes, the homogenized material was added to a clean Neubauer chamber until the counting area was adequately filled. Allowed for 2 minutes for the cells to settle before proceeding with the quantification of hemocytes.

The designated filled. The cells were allowed to settle for 2 minutes before hemocyte quantification. The counting area measured 1mm² with a height of 0.1 mm and was divided into 25 sub-areas. Five sub-areas were examined diagonally. The value obtained from the total of the 5 sub-areas was used in the following formula: number of cells / mL = number counted x 5 x dilution factor x 10,000. The dilution factor was calculated using the formula: (sampling volume + anticoagulant + dye) / sample volume. For this analysis, the dilution factor was determined as 4.2 = (100 μL + 300 μL + 20 μL) / 100 μL.

This fresh analysis was a methodological approach used to assess the health status of organisms and make preliminary diagnoses in both laboratory and field settings. The technique involved careful observation and dissection of shrimp to identify changes and pathogens in their organs and tissues. The sensitivity of this method depended on factors such as the technique itself, the level of infection, the characteristics of the parasites, the knowledge of the host organism, the transportation and preparation of samples, the use of appropriate equipment, and the expertise of the observers.

During each sampling event, five specimens were randomly collected at 7:00 am and kept in aerated conditions. The macroscopic analysis evaluated the morphology and pigmentation of the antennae, pleopods, and uropod. The microscopic analysis assessed the condition of various tissues including the gills, cephalothorax, epipodite, hepatopancreas, and intestinal tract. The severity of observed changes or injuries was categorized on a scale from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating no observable change and 4 indicating a high degree of alteration.

The specimen under examination was assessed in terms of the roughness of the antennae, body symmetry, and pigmentation of the appendages. Utilizing a precision scale, the weight of the individual was meticulously recorded. A syringe needle was employed to extract a sample of the hemolymph, which was subsequently alteration. The specimen was assessed for antennae roughness, body symmetry, and appendage pigmentation. The weight of the individual was recorded using a precision scale. Hemolymph was extracted using a syringe needle and placed on a microscope slide. A timed smear of the hemolymph was executed with a disposable needle until a bluish gelatinous consistency was achieved. The duration from the initiation of the smear to the point of gelatinization was documented as the hemolymph clotting time.

Cephalothorax assessment| A segment of the cephalothorax was excised from the area encompassing the gills performed until it achieved a bluish gelatinous consistency. The duration of the smear was documented as the hemolymph clotting time.

For the cephalothorax assessment, a segment of the cephalothorax including the gills was excised using sharp scissors. The specimen was examined under a microscope to evaluate characteristics such as melanization, necrosis, and calcium deposits.

In the gill assessment, a small fragment of the gill exoskeleton was placed on a slide for microscopic observation. The focus was on changes in the coloration of the gill filaments, including melanization, necrosis, and pale areas. The presence of protozoan species such as Zoothamnium sp., Epistylis sp., Acineta, Ascophris, and Bodo sp., as well as filamentous bacteria, fungi, bacterial clusters, melanization, and deformities, was investigated.

Assessment of the hepatopancreas | To assess the hepatopancreas, the carapace of the cephalothorax was excised to expose the organ. The coloration and dimensions of the hepatopancreas were scrutinized for signs of atrophy or hypertrophy. A sample was extracted using forceps for examination under a microscope, assessing the color, texture, melanization, and presence of tubular necrosis.

The epipodite was removed from the third pair of pereopods and placed on a slide for microscopic observation. Alterations such as melanization, necrosis, and pale areas were identified. The presence of protozoan organisms including Zoothamnium sp., Epistylis sp., Acineta, Ascophris, Bodo sp., filamentous bacteria, fungi, bacterial clusters, melanization, and deformities, was assessed.

In the assessment of the intestinal tract, a minor dorsal incision was made between the 5th and 6th somites. The tract was extracted from the region between the cephalothorax and the 1st somite and placed on a slide for microscopic examination. Changes such as hyperplasia, gregarines, cannibalism, saprophagia, and filamentous algae were identified.

2.7. Tissue Histology Data – Intestine and Hepatopancreas

For conventional light microscopy analyses, samples were collected from 15 shrimp per treatment and underwent standard histological processing at the Applied Animal Morphophysiology Laboratory of the Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido, following the methodology described by [

21]. Fragments measuring approximately 0.5cm were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde buffered with 0.1M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4 at 4°C. After dehydration and clearing, the material was immersed in histological paraffin (Synt®, granulated with a melting point of 58°C to 62°C). The fragments were immersed in two types of paraffin at 60°C, with overnight immersion in the first bath and one hour in the second to ensure complete impregnation of the material by paraffin. Subsequently, the fragments were embedded and labeled. The blocks were then cut into 5µ to 7µ sections using a microtome (LEICA RM 2125 RT®), collected on glass slides, and placed in an oven at 60°C for a maximum of six hours. The process continued with deparaffinization and rehydration, where the material was immersed in two baths of xylene for ten minutes, rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of alcohol (100%, 95%, and 70%), and running water for three minutes each. For staining, the slides were stained using Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) to highlight structures.

The material underwent analysis, wherein the most noteworthy images were captured through photomicrography under a light microscope (LEICA DM 500 HD) equipped with a camera (LEICA ICC50W). Histological slides were examined using a microscope with a micrometric eyepiece that was graduated in millimeters, and measurements were recorded in mm. Subsequently, the collected data were subjected to analysis to ascertain the disparities between the treatments, utilizing ImageJ -2 (1.54g, USA).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data was initially assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. After confirming these assumptions, the data underwent analysis of variance (ANOVA). Prior to conducting the statistical analysis, survival values (%) were transformed using the arcsine square root before conducting statistical analysis.

To compare the data between the nursery and grow-out phases, polynomial regression was applied to the PSB levels at the same time, while also considering time-dependent regressions for all treatments. To determine the most appropriate polynomial order for the model, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and coefficient of determination (R²) tests were utilized.

The data was analyzed using the statistical software R. Results were considered statistically significant with a P-value less than 0.05 for significant differences and a P-value less than 0.10 for trends.

3. Results

There was a linear effect with the dose increase in length (P=0.0041), weight per unit length (mg/mm, P=0.005), body weight (P=0.004), weight gain (P=0.004), final-to-initial live weight ratio (P=0.014), and survival (P<0.001), and improve feed conversion ratio (P=0.003) as shown in

Table 3. Additionally, there was a significant quadratic effect on final body weight (FBW, P=0.044 | FBW = 741.94 + 45.189x -3.9432x

2; R2=0.9386), and body weight gain (BWG, P=0.053 | BWG = 648.92 + 44.319x – 3.8288x

2; R2=0.9382), with a value based on the equation in 5.73 and 5.78 kg/t, respectively, of PSB in the diet.

As shown in

Table 4 the increase in the level of PBS significantly increased the weight gain and its uniformity, the length of the shrimp, and the body weight gain, and improved the feed conversion ratio, allowing a shrimp with a higher weight per unit of size, a higher final weight to initial weight ratio, and survival at the growth phase. These data show a result that allows us to recommend an optimal dose of PSB by BWG 6.94kg/t (BWG= 0.1208PSB² + 1.6761PSB + 10.644 | R²=0.98), and FCR 6.27kg/t (FCR= 0.0188 PSB² - 0.2358PSB + 1.7626 | R²=0.93).

In

Figure 1, the overall evolution of shrimp weight throughout the experiment is presented, both in line and bar modes, validating the cumulative effect that PSB promotes in the development of the animals.

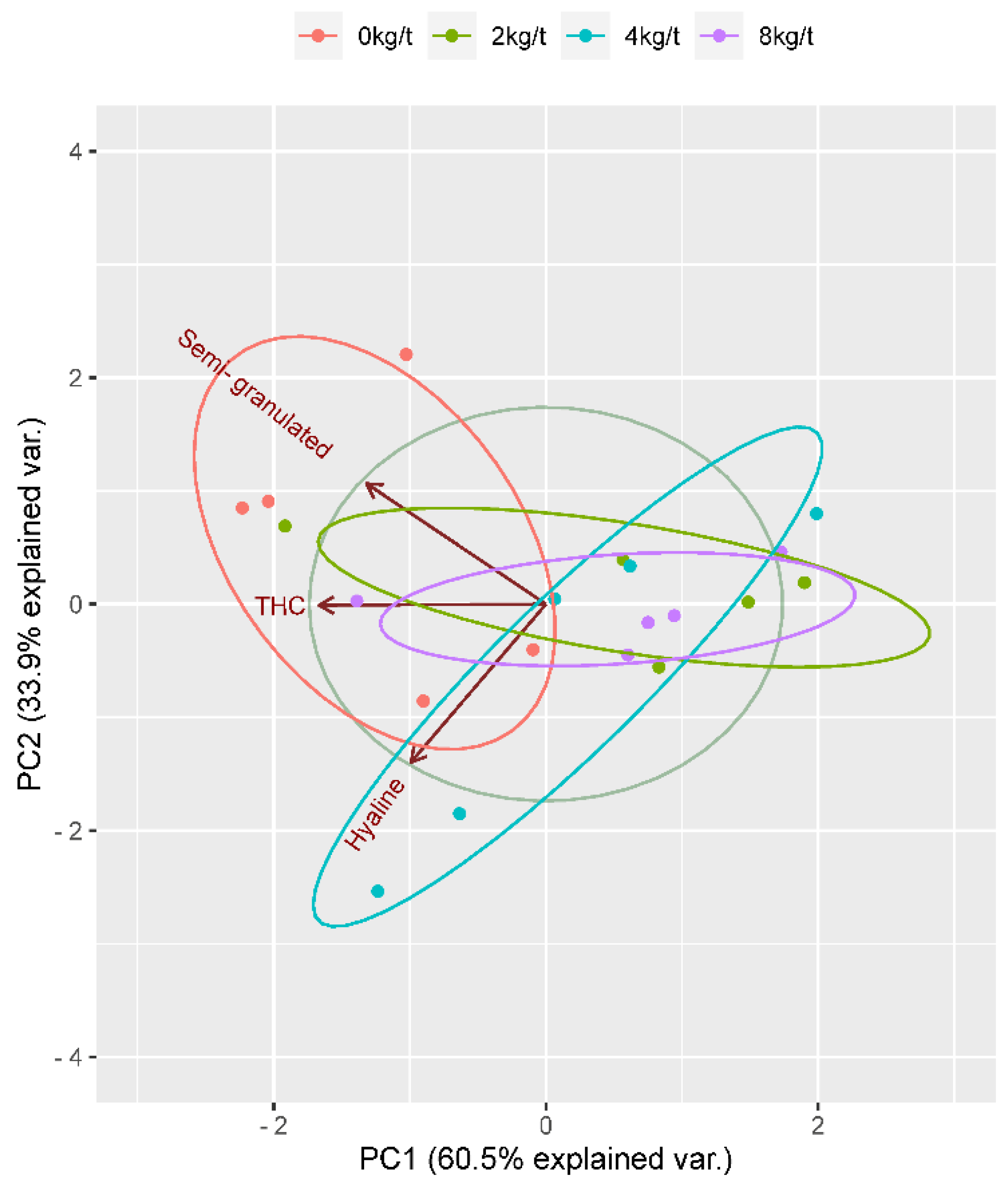

Table 5 presents cell types and total hemocyte count (THC) for shrimp on varying PSB diets. Granular cells function in immune response, while hyaline cells facilitate healing, revealing no dietary PSB impact. THC results mirrored those of granular cells, with decreased linear and quadratic influence (point: 6.00kg/t of PSB). PSB enhances the semi-granulated cells (P=0.0324, Linear and Quadratic, point: 5.2 kg/t of PSB). These cells exhibit dual characteristics and can differentiate into granular or hyaline types.

To visualize and understand the relationships between different variables, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot was made indicated by the axis’s labels PC1 and PC2,

Figure 4. The PC1 axis explains 60.5% of the variance, while the PC2 axis explains 33.9% of the variance. There are ellipses in different colors (red, green, blue, and purple), each representing different concentrations of substances (0kg/t, 2kg/t, 4kg/t, and 8kg/t respectively). And it is possible to see three labeled clusters: “semi-granulated” near the red ellipse; “THC” between red and green ellipses; “hyaline” near the blue ellipse.

PSB supplementation linearly increased the yield of shrimp (head-on) and the yield of shrimp fillet (head-on and shell-on),

Table 6. The improvement in yield shows that PSB allowed not only a higher final weight of the animals but also an important increase in meat production.

The PSB influenced the height of the villi and the other variables in a quadratic way with levels determined, Table 7. In this case, increased villus height indicates greater intestinal surface area, which can lead to improved nutrient absorption from the diet. In the table, villus height appears highest at 4 kg/t PSB and lowest at the control (0 kg/t PSB), with an optimal dose of 4.94 kg/t of PSB (Villus weight = 25.235 + 3.5406PSB – 0.3583PSB2; R2=0.6802).

Regarding width height, a wider villus base could provide more support for the villus structure and potentially more surface area for absorption, and the optimal dose of this was 4.16kg/t of PSB (Width height = 23.597 – 5.563PSB + 0.6676PSB2; R2=0.9949). A thicker lamina propria might indicate increased blood vessels supplying the intestine, based on supplementation of PSB in the diet. The lamina propria shows an optimal dose with 4.49kg/t of PSB (Lamina propria = 13.644 – 4.3351PSB + 0.4817PSB2; R2=0.9969). A higher H: W ratio typically indicates tall and slender villi, which may be more efficient for nutrient absorption compared to short and stubby villi. The table shows the H: W ratio is highest at 4 kg/t PSB, or specifically 4.49kg/t (Villus: width ratio = 13.644 – 4.3351PSB + 0.4817PSB2; R2=0.9969), potentially aligning with the highest villus height at this dose.

The observed influence of PSB on villus height, width, and lamina propria thickness suggests significant modulation of intestinal morphology, potentially impacting nutrient absorption efficiency,

Figure 3. Increased villus height, as seen at 4 kg/t PSB, implies a larger intestinal surface area, facilitating enhanced nutrient absorption from the diet. Similarly, wider villi bases, observed at 4.16 kg/t PSB, may provide additional structural support and surface area for absorption. The thicker lamina propria observed at 4.49 kg/t PSB suggests increased vascularization, potentially improving nutrient delivery to the intestine. The higher H: W ratio at 4 kg/t PSB indicates taller and slender villi, which are typically more efficient for nutrient absorption.

Figure 3.

Villus height (Height µm), width height (Width, µm), Lamina propria (LP, µm), and height: width ratio (HW) of shrimp intestine histomorphometry fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB) in a raincloud plot.

Figure 3.

Villus height (Height µm), width height (Width, µm), Lamina propria (LP, µm), and height: width ratio (HW) of shrimp intestine histomorphometry fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB) in a raincloud plot.

The intestine from the Control group, which did not receive any PSB, appears to have a less defined structure with irregular shapes,

Figure 4. So, at a lower dose of 2kg/t of PSB, the intestine appears more structured compared to the control group, and this could suggest that even at low levels, PSB has a noticeable effect on the intestinal structure. As the dose of PSB increases, the structure of the intestine appears to become more defined and well-structured. This suggests that PSB might be having a strengthening or modifying effect on the intestinal structure. The changes are most pronounced at the highest dose (8 kg/t), where the intestine shows a well-defined structure and multiple sections are visible.

The hepatopancreas in its control state is distinctly characterized by a remarkably dense aggregation of well-defined cellular structures, as illustrated in Figure 5, which provides a visual representation of this phenomenon. It is particularly interesting to note that the lipid reservoir exhibits no significant changes across the varying levels of PSB that are being evaluated, suggesting remarkable stability in this aspect despite alterations in cellular density. Conversely, when a higher dosage of 8kg/t is administered, there is a pronounced increase in cellular density that is concomitant with an elevation in glycogen storage specifically within the B cells, which is of considerable significance due to the critical role that glycogen plays in the overall energy metabolism of the organism. This glycogen, which can be swiftly converted to glucose in response to energy demands, enhances the shrimp's ability to tolerate unfavorable environmental conditions and underscores the multifaceted contributions of glycogen to a variety of metabolic processes, including the regulation of blood glucose levels as well as the maintenance of lipid and protein metabolism.

Figure 4.

Histological images of the intestines of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB). Stained with hematoxylin eosin.

Figure 4.

Histological images of the intestines of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB). Stained with hematoxylin eosin.

The supplementation of PSB seems to have influenced the thickening of the interstitial tissue, with a potential increase in phagocytosis. The thickening of this tissue could potentially enhance these exchanges, leading to improved cellular function and overall health. An increase in phagocytosis suggests an enhanced immune response, which could help the body better defend against infections and diseases. By potentially enhancing both the structure of interstitial tissue and the process of phagocytosis, PSB supplementation could contribute to improved cellular function and immune response.

Figure 7.

Histological images of the hepatopancreas of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB). Stained with hematoxylin eosin, 100µm and 20µm.

Figure 7.

Histological images of the hepatopancreas of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB). Stained with hematoxylin eosin, 100µm and 20µm.

4. Discussion

Documented a 9% increase in weight and a 3% enhancement in the survival rate of

Penaeus monodon when their diet was supplemented with sodium butyrate (at a concentration of 0.1%) encapsulated in vegetable oil [

22]. Utilized concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 2% sodium butyrate (salt, CH3CH2CH2COONa) in

Penaeus vannamei shrimp with an initial weight of 2.53 ± 0.03 g, maintained at a stocking density of 12 shrimp/m² [

2]. They observed an increase in live weight by the conclusion of the investigation in comparison to the control diet, with no significant differences noted among the tested concentrations. In terms of survival rates, a superior outcome was noted at the 2% sodium butyrate dosage relative to the control group. In a subsequent study, [

9] administered a dosage of 2 kg/t of sodium butyrate within a biofloc cultivation setting and did not observe any improvement in growth metrics; however, due to enhanced survival rates, they achieved greater overall productivity.

The utilization of organic acids, such as benzoic acid (BA), has been shown to adversely affect the growth and health of Penaeus vannamei, indicating that not all feed additives may confer benefits across different species or under varying environmental conditions [

20]. Furthermore, [

23] have investigated the microencapsulation of organic acids and their salts to enhance performance, digestive enzyme activity, immunity, and resistance to pathogens in shrimp, presenting a promising strategy to diminish reliance on antibiotics in shrimp aquaculture. In conclusion, the research highlights the diverse methodologies available for improving productivity in shrimp aquaculture. These methodologies encompass dietary modifications, feed additives, and environmental management strategies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The efficacy of these approaches is contingent upon the species of shrimp, the specific conditions of the aquaculture system, and the formulation of the diet or biofloc system.

The study conducted by [

6] involved the formulation of nine experimental diets featuring varying levels of fishmeal (FM) (45%, 30%, and 15%) and incremental levels of probiotic supplementation with PSB (0%, 0.3%, and 0.6%). These diets were administered to Pacific white shrimp in earthen outdoor ponds to evaluate growth performance, immune response, and resistance to stress and infection. The authors observed that shrimp fed diets with higher FM levels (30% vs. 45%) supplemented with PSB exhibited increased final weight and weight gain, suggesting that the incorporation of this product into shrimp diets can enhance growth performance. These findings align with our study, thereby validating the positive impact of PSB supplementation on the performance of vannamei shrimp; however, the efficacy of elevated supplementation levels is noteworthy. Specifically, the supplementation of 5.73 kg/t and 5.78 kg/t of PSB during the nursery phase yielded maximum final weight and weight gain, respectively. In the grow-out phase, supplementation levels of 6.94 kg/t and 6.27 kg/t promoted maximum weight gain and improved feed conversion, respectively.

Based on hematological evaluations, the semi-granulated PSB and THC demonstrated a significant impact on PSB levels within the dietary composition. The optimal concentrations were determined through equations elucidating the influence of these cellular components on shrimp, with dosages calculated at 5.2 and 6.0 kg/t, respectively. The variation observed in the outcomes arises from the broader spectrum of levels assessed in our investigation (2, 4, and 8 kg/t as opposed to solely 2 kg/t), suggesting that the effects of PSB are likely dose-dependent, with elevated concentrations yielding a more pronounced influence on hemolymph composition, particularly noted at the 4.0 kg/t level of PSB. It is plausible that PSB enhances and fortifies the intestinal barrier, thereby diminishing the translocation of deleterious pathogens into the hemolymph; however, its impact on overall immunological responses in shrimp remains somewhat ambiguous and may also be contingent upon dosage.

According to principal component analysis (PCA), the supplementation of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) revealed significant similarities among the clusters, with a marked divergence from the diet containing 0 kg/t of PSB. The vectors illustrate a reciprocal relationship between hyaline and semi-granulated cells; concurrently, they indicate that total hemocyte count (THC) maintains a balanced status concerning the observed outcomes. Consequently, THC is given greater emphasis in the assessment of shrimp hemolymph. In this context, PSB exerts a significant influence that is not captured by univariate analysis. The supplementation of PSB is pivotal in enhancing the parameters of shrimp hemolymph, thereby contributing to a more robust immune response and improved overall health in Penaeus vannamei.

Reported no significant differences associated with the inclusion of sodium butyrate in the diets of shrimp [

2]. In contrast, [

9] found that shrimp fed diets supplemented with sodium butyrate exhibited an increase in both total and granular hemocyte counts, as well as elevated levels of hyaline cells. The dietary incorporation of probiotics such as PSB resulted in enhanced immune parameters, including total hemocyte count, phenoloxidase activity, and lysozyme levels, all of which are vital for immune function in shrimp. These observations suggest that PSB supplementation may enhance the immune response in Pacific white shrimp [

6].

The evaluation of shrimp meat yield has been somewhat limited in previous studies; however, this metric is essential not only for assessing shrimp yield per unit area but also for evaluating survival rates. Consequently, the present study aimed to assess the yield of headless and shell-less shrimp. The results indicated a consistent increase in yield corresponding to varying levels of PSB supplementation. These findings suggest a potential positive influence of PSB on shrimp growth and meat yield, which may subsequently enhance productivity efficiency per unit area.

The structural enhancements observed within the intestinal system, particularly at elevated levels of PSB, can be attributed to the fortifying or modulating effects of PSB on intestinal architecture. The more distinct and well-organized morphology of the intestine at increased PSB concentrations, exemplified by 8 kg/t, indicates a gradual improvement in intestinal structure concomitant with augmented PSB supplementation. The disparity observed between the control cohort, which exhibited a less delineated intestinal architecture, and the groups receiving PSB supplementation underscores the potential of PSB to positively influence intestinal morphology, even at lower levels. This observation suggests that PSB supplementation may significantly impact intestinal structure, with more pronounced alterations becoming evident at higher concentrations.

Following the administration of a dosage of 2 kg/t, a marked reduction in cellular density is observable in the hepatopancreas, which may suggest potential cellular damage that becomes progressively more pronounced and escalates significantly upon increasing the dosage to 4 kg/t. A comprehensive analysis conducted by [

24] elucidates the critical role of cinnamaldehyde in enhancing growth performance and facilitating carbohydrate metabolism in shrimp, thereby indicating that dietary alterations can profoundly affect metabolic pathways and energy utilization efficiency within these organisms. In alignment with this premise, [

25] provide evidence demonstrating that dietary supplements, such as glycerol monolaurate, can substantially improve growth performance, lipid metabolism, and immune response mechanisms in shrimp; however, it is important to acknowledge that excessive levels of such supplements may precipitate adverse disruptions in the stability of intestinal microbiota. In a divergent viewpoint, [

26] clarify how infection by

Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei leads to the downregulation of lipid metabolism within the hepatopancreas, thereby highlighting the intrinsic susceptibility of shrimp to metabolic disturbances that may emerge under conditions of pathogenic stress. Collectively, these investigations emphasize the intricate and multifaceted interactions that exist between dietary interventions and the overall metabolic health of shrimp. While certain dietary supplements can significantly enhance cellular density and glycogen accumulation, thereby ameliorating energy metabolism and stress resilience, there are concomitant risks of cellular damage and metabolic imbalance that may arise at elevated dosages or in the context of pathogenic challenges. This underscores the critical necessity for the careful optimization of dietary strategies aimed at effectively bolstering the health and growth of shrimp populations.

Sodium butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid synthesized by gut microbiota, exerts multiple beneficial effects on the health of the hepatopancreas. It enhances lipid metabolism in hepatocytes, mitigates hepatic steatosis, and regulates the expression of genes associated with fatty acid oxidation [

27]. Furthermore, sodium butyrate inhibits aerobic glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, thereby inducing apoptosis and suppressing cellular proliferation, which indicates its potential as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of liver cancer [

16,

28]. Its preventive effects against inflammation and liver injuries further underscore its therapeutic potential for a range of liver conditions. Overall, sodium butyrate's capacity to modulate lipid metabolism, inhibit glycolysis, and regulate gene expression highlights its significance in promoting hepatopancreas health and addressing liver disorders effectively.

5. Conclusions

Supplementing PSB in the diets of Penaeus vannamei from post-larval to grow-out stages results in significant improvements in health, histological development, and overall performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N.V., A.V.B., A.L.T., M.A.S., B.S., and M.R.L.; methodology, D.N.V., A.V.B., A.L.T., M.A.S., B.S., M.R.L., M.F.O., and M.E.S.O.; software, M.R.L, and M.E.S.; validation, M.R.L, and M.E.S.;formal analysis, M.R.L, J.T.S., A.E.C., V.M.F.S., M.A.M.S., M.F.O., and M.E.S.; investigation, M.R.L, J.T.S., A.E.C., V.M.F.S., M.A.M.S., and M.E.S.; resources, M.R.L, and D.N.V.; data curation, M.R.L, D.N.V. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.S.O and M.R.L; writing—review and editing, M.E.S.O, B.S., M.S.A., D.N.V., and M.R.L.;visualization, M.R.L, D.N.V., J.S., B.S., M.A.S., A.V.B., and A.L.T; supervision, M.R.L., D.N.V., and B.S.; project administration, M.R.L., D.N.V., J.S., and B.S.; funding acquisition, M.R.L., D.N.V., A.V.B., B.S., and M.A.S.;.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

To the team of the Research Group on Technological Innovation and Precision Animal Production at UFERSA. To the collaborators from Vidara do Brasil, Novation, Deltavit, Optimal Technologies, and BioArtêmia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mine, S.; Boopathy, R. Effect of organic acids on shrimp pathogen, Vibrio harveyi. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.C.; Schleder, D.D.; Silva, F.N.V.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Seiffert, W.Q. Dietary supplementation with butyrate and polyhydroxybutyrate on the performance of Pacific white shrimp in biofloc systems. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2016a, 47, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, P.Y.C.; Liong, K.H.; Schoeters, E. Dietary encapsulated butyric acid (Butipearl™) and microemulsified carotenoids (Quantum GLO™ Y) on the growth, immune parameters, and their synergistic effect on pigmentation of hybrid catfish (Clarias macrocephalus × Clarias gariepinus). Fish. Aquac. J. 2017, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Soltanian, S.; Vazirzadeh, A.; Akhlaghi, M.; Morshedi, V.; Gholamhosseini, A.; Mozanzadeh, M.T. Dietary butyric acid improved growth, digestive enzyme activities, and humoral immune parameters in barramundi (Lates calcarifer). Aquac. Nutr. 2020, 26, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hany, M.R.; Abdel-Latif, M.; Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Dawood, A.O.; Menanteau-Ledouble, S.; El-Matbouli, M. Benefits of dietary butyric acid, sodium butyrate, and their protected forms in aquafeeds: A review. Aquac. Nutr. 2020, 26, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi, P.; Taheri Mirghaed, A.; Hosseini Shekarabi, S.P. Zootechnical performance, immune response, and resistance to hypoxia stress and Vibrio harveyi infection in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) fed different fishmeal diets with and without addition of sodium butyrate. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 26, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Kuśnirek, M.; Lipiński, K.; Antoszkiewicz, Z.; Matusevičius, P. Different forms of butyric acid in poultry nutrition – a review. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2024, 33, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado Corrêa, N.; Bolívar Ramírez, N.C.; Chamorro Legarda, E.; Sousa Rocha, J.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Vieira, F.N. Dietary supplementation with probiotic and butyrate in the shrimp nursery in biofloc. Bol. Inst. Pesca 2018, 44, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.C.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Bolívar, N.; Seiffert, W.Q. Butyrate and propionate improve the growth performance of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Res. 2016b, 47, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.C.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Bolívar, N.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Alves, J.G.F.; Nolasco-Soria, H. The effects of dietary supplementation with butyrate and polyhydroxybutyrate on the digestive capacity and intestinal morphology of Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 2016c, 49, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpwaga, A.Y.; Ray, G.W.; Yang, Q.; Kou, S.; Tan, B.; Wu, J.; Mao, M.; Ge, Z.-B.; Feng, L. Protective effects of butyric acid during heat stress on the survival, immune response, histopathology, and gene expression in the hepatopancreas of juvenile Pacific shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 150, 109610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Han, C.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, H. Dietary sodium butyrate improves intestinal health of triploid Oncorhynchus mykiss fed a low fish meal diet. Biology 2023, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.C.; Jatobá, A.; Schleder, D.D.; Vieira, F.N.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Seiffert, W.Q. Dietary supplementation with butyrate and polyhydroxybutyrate on the performance of Pacific white shrimp in biofloc systems. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2016d, 47, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.C.; Vieira, F.N.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; Bolívar, N.; Seiffert, W.Q. Butyrate and propionate improve the growth performance of Penaeus vannamei. Aquac. Res. 2016e, 47, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elham, A.; Saleh, N.E.; Abdelmeguid, N.E.; Barakat, K.M.; Abdel-Mohsen, H.H.; El-Bermawy, N.M. Sodium propionate as a dietary acidifier for European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fry: Immune competence, gut microbiome, and intestinal histology benefits. Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Qin, Y.; Song, T.; Wang, K.; Ye, J. Dietary sodium butyrate administration alleviates high soybean meal-induced growth retardation and enteritis of orange-spotted groupers (Epinephelus coioides). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1029397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Effects of sodium butyrate on protein metabolism and its related gene expression of triploid crucian carp (Carassius auratus tripl). Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 24, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.T.; Liang, H.; Li, J.; Deng, T.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. Health benefits of butyrate and its producing bacterium, Clostridium butyricum, on aquatic animals. Fish Shellfish Immunol. Rep. 2023, 5, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamis, J.O.; Tumbokon, B.L.M.; Caigoy, J.C.C.; Bunda, M.G.B.; Serrano, A.E. Effects of vinegars and sodium acetate on the growth performance of Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Isr. J. Aquac. Bamidgeh 2017, 69, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loya-Rodriguez, M.; Palacios-Gonzalez, D.A.; Lozano-Olvera, R.; Martínez-Rodríguez, I.; Puello-Cruz, A.C. Benzoic acid inclusion effects on health status and growth performance of juvenile Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). N. Am. J. Aquac. 2023, 85, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.M.C.; Rodrigues, C.J.; Behmer, O.A.; Freitas Neto, A.G. Manual de Técnicas para Histologia Normal e Patológica., 2nd ed.; Manole: Barueri, SP, Brazil, 2003; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nuez-Ortin, W.G. Gustor-aqua: An effective solution to optimize health status and nutrient utilization. Int. Aquafeed 2011, July–August, 18–20.

- Mohiuddin, A.; Chowdhury, K.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Bunod, J.-D.; Dong, X. Effects of microencapsulated organic acid and their salts on growth performance, immunity, and disease resistance of Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Sustainability 2021, 13, 47791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andri, H.; Setiawati, M.; Jusadi, D.; Suprayudi, M.A.; Ekasari, J.; Wahjuningrum, D. Evaluation of cinnamaldehyde administration to feed with different protein energy levels and ratios to Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). J. Akuakultur Indones. 2024, 23, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ding, Y.; Jing, F.; Chen, Z.; Su, C.; Pan, L. Effects of dietary glycerol monolaurate on growth and digestive performance, lipid metabolism, immune defense, and gut microbiota of shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 128, 109666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-J.; Chen, J.; Liao, G.-M.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, X.; Li, T.; Long, M.; Fan, X.-L.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Pan, G.; Zhou, Z. Down-regulation of lipid metabolism in the hepatopancreas of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) upon light and heavy infection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei: A comparative proteomic study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Venugopal, S.K.; Pisarello, M.J.; Gradilone, S.A. The role of gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acid butyrate in hepatobiliary diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 2023, 193, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Zhou, E.; Liu, C.; Wicks, H.; Yildiz, S.; Razack, F.; Ying, Z.; Kooijman, D.P.Y.; Heijink, M.; Kostidis, S.; Giera, M.; Sanders, I.M.J.G.; Kuijper, E.J.; Smits, W.K.; Willems van Dijk, K.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Wang, Y. Dietary butyrate ameliorates metabolic health associated with selective proliferation of gut Lachnospiraceae bacterium 28-4. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e166655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Evolution of the body weight of the shrimp from the nursery phase (PL30, 320 shrimp/m2, from PL30 to PL65 | 35 d) to the growth phase (75 shrimp/m2, from PL65 to PL145 | 80 d) of shrimp fed increasing levels of PSB, for 115 days in total. The area highlighted in gray on each trend line is the experimental effect, of the Tukey test.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the body weight of the shrimp from the nursery phase (PL30, 320 shrimp/m2, from PL30 to PL65 | 35 d) to the growth phase (75 shrimp/m2, from PL65 to PL145 | 80 d) of shrimp fed increasing levels of PSB, for 115 days in total. The area highlighted in gray on each trend line is the experimental effect, of the Tukey test.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot. Hemolymph from shrimp meat fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB), cells per mL of hemolymph from granular, hyaline, semi-granulated cells, and the total hemocyte count (THC).

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot. Hemolymph from shrimp meat fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB), cells per mL of hemolymph from granular, hyaline, semi-granulated cells, and the total hemocyte count (THC).

Table 1.

Dietary and nutritional composition of growth phase experimental diets for shrimp fed protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

Table 1.

Dietary and nutritional composition of growth phase experimental diets for shrimp fed protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

| Items. % |

0 |

PSB, kg/t |

| 2 |

4 |

8 |

| Soybean meal (45%CP) |

41.445 |

|

|

|

| Corn |

31.420 |

|

|

|

| Fish meal (51.18% CP) |

11.276 |

|

|

|

| Fish oil |

|

4.500 |

|

|

|

| Artemia biomass1 (50%CP) |

4.075 |

|

|

|

| Soy lecithin |

|

2.500 |

|

|

|

| Salt |

1.251 |

|

|

|

| Potassium |

1.200 |

|

|

|

| Premix* |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| Vitamin C |

0.500 |

|

|

|

| L-Lysine HCl |

|

0.3795 |

|

|

|

| DL-Methionine |

0.2575 |

|

|

|

| Adsorbent |

|

0.1000 |

|

|

|

| Binder |

|

0.0350 |

|

|

|

| Antioxidant |

|

0.0300 |

|

|

|

| Antifungal |

|

0.0300 |

|

|

|

| Control diet, % |

|

|

99.8 |

99.6 |

99.2 |

| PSB, % |

|

|

0.20 |

0.40 |

0.80 |

| Total |

|

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Humidity |

% |

10.237 |

|

|

|

| Dry matter |

% |

83.763 |

|

|

|

| Ash |

% |

7.513 |

|

|

|

| Total Digestible Nutrients |

% |

56.208 |

|

|

|

| Crude energy |

kcal/kg |

4200.0 |

|

|

|

| Crude protein |

% |

35.0 |

|

|

|

| Fiber |

% |

4.768 |

|

|

|

| ADF |

% |

6.983 |

|

|

|

| NDF |

% |

10.499 |

|

|

|

| Methionine |

% |

0.800 |

|

|

|

| Met+Cis |

% |

1.300 |

|

|

|

| Lysine |

% |

2.100 |

|

|

|

| Threonine |

% |

1.400 |

|

|

|

| Tryptophan |

% |

0.300 |

|

|

|

| Arginine |

% |

1.900 |

|

|

|

| Isoleucine |

% |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| Valine |

% |

1.610 |

|

|

|

| Fat |

% |

5.676 |

|

|

|

| Linoleic acid |

% |

1.260 |

|

|

|

| Linolenic acid |

% |

1.200 |

|

|

|

| Arachidonic acid |

% |

0.688 |

|

|

|

| Calcium |

% |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| Phosphorus |

% |

0.733 |

|

|

|

| Sodium |

% |

0.350 |

|

|

|

| Potassium |

% |

1.316 |

|

|

|

| Chloride |

% |

1.002 |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Water parameters during the nursey and growth phases of cultivation of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

Table 2.

Water parameters during the nursey and growth phases of cultivation of shrimp fed with protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

| Nursey phase |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment

(kg/t PSB)

|

pH |

Cond.

µS/cm |

Salin.

ppm |

Temp.

0C |

DO

mg/L |

TDS

mg/L |

Ammonia

mg/L |

Nitrite

mg/L |

| 0 |

8.01 |

4.41 |

2.74 |

29.71 |

6.73 |

2.21 |

0.025 |

0.04 |

| 2 |

8.24 |

4.41 |

2.42 |

29.43 |

7.00 |

2.21 |

0.010 |

0.02 |

| 4 |

8.24 |

4.43 |

2.43 |

29.18 |

7.00 |

2.22 |

0.010 |

0.04 |

| 8 |

8.10 |

4.42 |

2.42 |

29.85 |

7.35 |

2.21 |

0.000 |

0.02 |

| Growth phase |

Treatment

(kg/t PSB)

|

pH |

Cond. |

Salin. |

Temp. |

DO |

TDS |

Ammonia |

Nitrite |

| |

|

µS/cm |

ppm |

0C |

mg/L |

mg/L |

mg/L |

mg/L |

| 0 |

7.45 |

5.34 |

2.98 |

28.65 |

6.32 |

3.02 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| 2 |

7.52 |

5.67 |

2.87 |

28.78 |

6.44 |

3.15 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

| 4 |

7.83 |

5.38 |

2.90 |

28.56 |

6.49 |

3.16 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

| 8 |

7.59 |

5.44 |

2.92 |

28.73 |

6.38 |

3.32 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

Table 3.

Final length (FL, mm), length gain (LG), length-to-weight ratio (W/L, mg/mm), feed intake (FI, mg/shrimp), initial live weight of PL30 (IBW, mg), final body weight of PL65 (FBW, mg), body weight gain (BWG, mg/shrimp), feed conversion ratio (FCR, mg/mg), final weight-to-initial weight ratio (FBW/IBW), and survival (SURV, %) during the 35 days, from PL30 to PL65, of shrimp fed increasing levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

Table 3.

Final length (FL, mm), length gain (LG), length-to-weight ratio (W/L, mg/mm), feed intake (FI, mg/shrimp), initial live weight of PL30 (IBW, mg), final body weight of PL65 (FBW, mg), body weight gain (BWG, mg/shrimp), feed conversion ratio (FCR, mg/mg), final weight-to-initial weight ratio (FBW/IBW), and survival (SURV, %) during the 35 days, from PL30 to PL65, of shrimp fed increasing levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

| PSB (kg/t) |

FL |

LG |

W/L |

FI |

IBW |

FBW |

BWG |

FCR |

FBI/IBW |

SURV |

| 0 |

49.525b |

24.363b |

14.840b |

557.621 |

93.009 |

735.156b |

642.148b |

0.870a |

7.910c |

77.684b |

| 2 |

51.075a |

25.950ab |

16.323a |

531.646 |

94.365 |

834.653a |

740.288a |

0.721b |

8.853b |

87.795a |

| 4 |

51.513a |

26.288a |

16.418a |

539.886 |

94.638 |

846.031a |

751.394a |

0.720b |

8.946b |

87.942a |

| 8 |

51.550a |

26.775a |

16.563a |

538.563 |

92.673 |

853.354a |

760.681a |

0.708c |

9.259a |

89.415a |

| P value |

0.0386 |

0.0658 |

0.0017 |

0.6229 |

0.8539 |

0.0015 |

0.0018 |

0.0005 |

0.0184 |

<0.001 |

| SEM |

0.552 |

0.656 |

0.296 |

16.332 |

1.617 |

20.233 |

20.401 |

0.027 |

0.278 |

1.524 |

| Linear |

0.0041 |

0.0390 |

0.0050 |

0.5770 |

0.8110 |

0.0040 |

0.0040 |

0.0030 |

0.0140 |

<0.001 |

| Quadratic |

0.1230 |

0.2860 |

0.0620 |

0.4740 |

0.4050 |

0.0440 |

0.0530 |

0.0130 |

0.2840 |

0.0030 |

| C.V.(%) |

2.5000 |

5.9200 |

2.3500 |

6.4900 |

4.3400 |

3.8700 |

6.7100 |

7.7600 |

7.7900 |

3.8000 |

Table 4.

Body weight (BW, g/shrimp), weight uniformity (UNI, %), shrimp length (SL, mm), length uniformity (LU, %), feed intake (FI, g/shrimp), body weight gain (BWG, g/shrimp), feed conversion ratio (FCR, g/g), length-to-weight ratio (g/mm), final weight-to-initial weight ratio (FBW/IBW), and survival (SURV, %) during the 80 days of shrimp fed increasing levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB ).

Table 4.

Body weight (BW, g/shrimp), weight uniformity (UNI, %), shrimp length (SL, mm), length uniformity (LU, %), feed intake (FI, g/shrimp), body weight gain (BWG, g/shrimp), feed conversion ratio (FCR, g/g), length-to-weight ratio (g/mm), final weight-to-initial weight ratio (FBW/IBW), and survival (SURV, %) during the 80 days of shrimp fed increasing levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB ).

| PSB, kg/t |

BW |

UNI |

SL |

LU |

FI |

BWG |

FCR |

MMG |

FBW/IBW |

SURV |

| PSB | 0kg/t |

11.196c |

79.375b |

123.225b |

87.125 |

18.693 |

10.461c |

1.804a |

11.070a |

15.257b |

82.231b |

| PSB | 2kg/t |

14.836b |

83.250ab |

136.175a |

87.850 |

17.560 |

14.001b |

1.255b |

9.185b |

17.835ab |

86.626a |

| PSB | 4kg/t |

15.884ab |

85.250ab |

137.750a |

87.875 |

18.101 |

15.050ab |

1.204b |

8.674bc |

19.182a |

88.875a |

| PSB | 8kg/t |

17.239a |

86.500a |

138.150a |

88.125 |

17.470 |

16.385a |

1.067b |

8.015c |

20.207a |

89.410a |

| P value |

<0.001 |

0.0087 |

<0.001 |

0.6907 |

0.0642 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.0002 |

<0.001 |

| SEM |

0.3493 |

1.5172 |

1.5697 |

0.7129 |

0.3708 |

0.3503 |

0.07175 |

0.2651 |

0.6837 |

0.8499 |

| Linear |

<0.001 |

0.005 |

<0.001 |

0.383 |

0.08 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Quadratic |

<0.001 |

0.173 |

<0.001 |

0.665 |

0.502 |

<0.001 |

0.002 |

0.003 |

0.063 |

0.004 |

| C.V.(% |

5.31 |

3.92 |

2.55 |

0.762 |

4.38 |

5.64 |

10.75 |

5.90 |

8.33 |

2.12 |

Table 5.

Hemolymph from shrimp meat fed with different levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB), cells per mL of hemolymph from granular, hyaline, semi-granulated cells, and the total hemocyte count (THC).

Table 5.

Hemolymph from shrimp meat fed with different levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB), cells per mL of hemolymph from granular, hyaline, semi-granulated cells, and the total hemocyte count (THC).

| PSB |

Granular |

Hyaline |

Semi-granulated |

THC |

| PSB | 0kg/t |

2,10E+06

|

2,10E+06 |

2,86E+06a |

7,06E+06 |

| PSB | 2kg/t |

2,37E+06 |

1,51E+06 |

1,18E+06ab |

5,06E+06 |

| PSB | 4kg/t |

1,68E+06 |

2,44E+06 |

1,09E+06b |

5,21E+06 |

| PSB | 8kg/t |

1,68E+06 |

1,81E+06 |

1,26E+06ab |

4,75E+06 |

| P value |

0,687 |

0,5249 |

0,0324 |

0,1881 |

| SEM |

4,79E+05 |

4,50E+05 |

4,35E+05 |

7,78E+05 |

| Linear |

0.062 |

0.241 |

0.031 |

0.028 |

| Quadratic |

0.793 |

0.615 |

0.028 |

0.015 |

| C.V. |

54,72 |

51,24 |

60,94 |

31,55 |

Table 6.

The relative weight of the shrimp without head (Shrimp, %), and without all shells (Meat, %) of shrimp meat fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

Table 6.

The relative weight of the shrimp without head (Shrimp, %), and without all shells (Meat, %) of shrimp meat fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

| |

Shrimp, % |

Meat, % |

| PSB | 0kg/t |

59.33b |

47.99b |

| PSB | 2kg/t |

60.2443ab |

49.5901ab |

| PSB | 4kg/t |

61.4367a |

50.1384ab |

| PSB | 8kg/t |

61.7036a |

51.6821a |

| P value |

0.0011 |

0.0442 |

| SEM |

0.4616 |

0.9142 |

| Linear |

<0.001 |

0.006 |

| Quadratic |

0.134 |

0.652 |

| C.V. |

4.170 |

10.05 |

Table 8.

Shrimp intestine histomorphometry fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

Table 8.

Shrimp intestine histomorphometry fed with levels of protected sodium butyrate (PSB).

| |

Villus height,μm

|

Width height,μm

|

Lamina Propria |

H: W ratio |

| PSB | 0kg/t |

26.432b |

23.791a |

13.530a |

1.205c |

| PSB | 2kg/t |

27.690b |

14.623b |

7.205bc |

2.097b |

| PSB | 4kg/t |

36.059a |

12.415b |

3.783c |

2.997a |

| PSB | 8kg/t |

30.229ab |

21.755a |

9.831ab |

1.572bc |

| P value |

0.0143 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| SEM |

1.9744 |

1.368 |

0.935 |

0.180 |

| Linear |

0.129 |

0.912 |

0.89 |

0.27 |

| Quadratic |

0.024 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| C.V. |

32.76 |

41.27 |

61.46 |

40.75 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).