1. Introduction

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of deaths worldwide, with chronic respiratory diseases among those causing the highest rates of mortality and morbidity [

1,

2]. Patients with chronic respiratory diseases constantly experience a profound negative impact on their quality of life [

3,

4]. Additionally, the frequent necessity to attend multiple hospital consultations places a significant burden on work productivity and in healthcare systems [

3,

4,

5].

The cornerstone of respiratory disease management is the use of inhaled treatments, which enable a rapid and targeted delivery of drugs to the lungs while minimizing systemic exposure and potential side effects [

6,

7]. In fact, inhaled therapy is among the most frequently prescribed treatments, being the choice of the inhaler device considered just as important as selecting the most appropriate drug [

6]. However, this critical aspect is often overlooked or underestimated by healthcare professionals in both primary and secondary care [

6].

Despite the advancements in inhaler device technology, the "perfect inhaler" does not exist, with dry powdered inhalers (DPIs) and metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) remaining as the two most widely prescribed inhaler types [

8]. DPIs are typically associated with fewer critical errors and, due to their lower carbon footprint, are considered more eco-conscious devices [

9,

10]. Selecting the most appropriate inhaler, aligned with the patient’s ability to use it correctly and the inhaler reliability in delivering medication, significantly influences treatment adherence with prescribed timing, dosage, and frequency and, ultimately, impacts disease outcomes [

11,

12]. Inadequate inhaler use can result in suboptimal treatment, increased hospitalizations, and a reduced quality of life for patients [

12,

13]. Nevertheless, adherence to treatment remains a critical factor for ensuring the effectiveness of inhaler therapies [

12,

13]. The evaluation of inhaler technique and adherence, along with the assessment of disease outcomes and patient satisfaction, is essential to conclude if the inhaler is suitable for the patient and if it is promoting clinical benefits [

14].

Considering the relevance of these topics in real clinical practice, it is essential to collect real-world evidence on most commonly used inhalers, highlighting patterns of misuse, compliance, and adherence, alongside relevant clinical information. This evidence will be critical for the optimization of inhaler selection and usage and, ultimately contribute to improved clinical outcomes, reduce side effects, enhance patient adherence, and decrease the overall healthcare costs. In this study, we explore real-world evidence on the most prescribed inhalers for both ambulatory and hospitalized patients, focusing on their correct use and treatment adherence. Furthermore, the study investigates the patients who switch inhalers after hospitalization and the factors associated with this change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Overview

The AIRE project is a unicentric, observational, cross-sectional study conducted between March 2023 and March 2024. The study population consisted of hospitalized patients who were prescribed inhaled therapy during their hospitalization. The patient recruitment was prospective, and each week was consecutively included data of inpatients under inhaled therapy during hospitalization across different medical inpatient services. A cross-sectional review of treatments was performed every week using the electronic prescription program for hospital admission across various inpatient departments (internal medicine, pulmonology, geriatrics and others [cardiology, endocrinology

After patient selection, a single face-to-face visit was performed during the patient's hospitalization by nurses specialized in inhaled therapy education from the pulmonology service. The data collected were concurrent for clinical information (performed during the single visit) and retrospective for the assessment of patient history or tests performed in the previous year.

This study was designed to evaluate the suitability of inhaled therapy in hospitalized patients, both with and without a history of inhaler use prior to hospitalization, as well as their inhalation technique (critical inhaler errors), adherence to previously prescribed inhaled treatments and the frequency of inhaler changes after hospitalization, and the factors associated with these changes.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital of San Carlos (CI:23/069-O_M_NoSP). All participants signed an informed consent prior to the enrollment in the study, in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Spain's new Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights, effective since December 7, 2018.

2.2. Data Source and Patient Selection

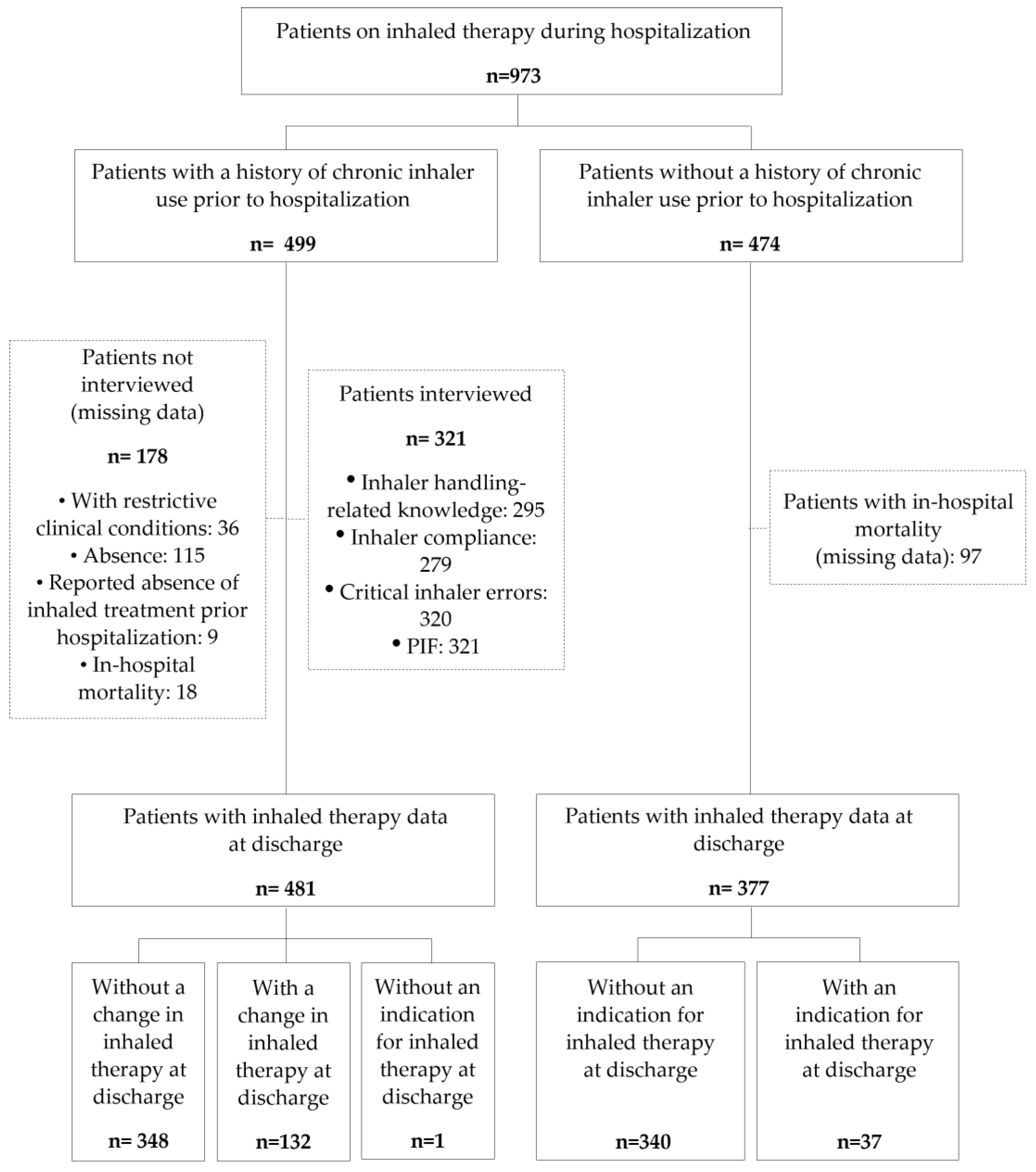

Hospitalized patients receiving inhaled pharmacotherapy (bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory drugs) were identified through their electronic prescription history during the weekly cross-sectional review of treatments at the Clinical Hospital of San Carlos (

Figure 1). The source of information on the prescription of inhaled therapies during hospitalization was the in-hospital e-prescribing program, FarmaTools

®.

2.3. Data and Clinical Variables Collected

Data regarding inhalers prescribed during the hospitalization period were collected from FarmaTools

®. Clinical information was provided by the Selene Plus

® program and the Horus

® Primary Care program, including comorbidities (Charlson index [

15]), current smoker status, history of hospitalizations, history of antibiotic/corticosteroid courses for respiratory diseases, cause of hospitalization, responsible inpatient service, and other relevant data (e.g., in-hospital mortality rate and 90-day post-discharge mortality rate).

For patients with a history of prior inhaler use, information on their at-home inhaled therapy before hospitalization (therapeutic class, inhaler type and number, posology, prescriber, trainer, and treatment duration) was collected from the Single Prescription Module (MUP) program, a tool that provides a unified and comprehensive pharmacotherapeutic history of the patient available in Madrid.

During a face-to-face visit conducted during the patient's hospitalization, additional data were collected, including details about compliance and inhalation technique (critical inhaler errors) with at-home inhaler treatment, assessed using the TAI questionnaire [

16], and measurement of maximum peak inspiratory flow (PIF, L/min). Maximum PIF was evaluated with the In-Check DIAL G16 device (Clement Clarke, UK), which simulates the internal resistance of a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) during inhalation. Participants were instructed to exhale fully to empty their lungs and then inhale as hard and fast as possible. Maximum peak PIF measurements were taken twice, being the highest value included in the analysis.

The patient-reported level of knowledge regarding inhaler management was assessed by asking, without any guidance from the interviewer, whether their understanding was 'good,' 'fair,' or 'poor.' The interview was conducted after the first week of hospitalization; if the patient was not present in the room after three attempts, they were considered absent.

To avoid altering routine clinical practice and to preserve the blinding of inhaled therapy assessments, the medical and nursing staff responsible for the patient's hospitalization were not informed.

2.4. Data Analysis

Qualitative variables are presented as frequency distributions, while quantitative variables are summarized using the mean and standard deviation (SD). For quantitative variables with an asymmetric distribution, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are reported. Quantitative variables showing an asymmetric distribution are summarized with the median and interquartile range (IQR). For the comparisons between the qualitative variables, the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was performed, as appropriate. For the comparisons of means between two independent groups, Student's t-test were performed if the variables followed a normal distribution, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for asymmetric variables. The comparisons of means across more than two independent groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test for asymmetric variables.

A binary logistic regression model was used to explore the association between changing device at discharge and the other independent variables. Missing data was not imputed. A significant value of 5% was accepted for all tests. Data processing and analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26 statistical.

4. Discussion

By using real-world data from a clinical audit conducted in, this study provides novel insights about inhaled therapy in hospitalized patients, focusing on their at-home inhaled therapy before, during, and after hospital discharge. Our analysis describes patient’s clinical characteristics, the level of patient’s knowledge about inhaler handling, critical inhaler errors, adherence, maximum PIF, and changes made to inhaler devices at discharge. Additionally, here we also explore the factors associated with inhaler changes at discharge.

In our cohort of patients, our main findings are that only less than a third of patients changed their prescribed inhaler device at hospital discharge, despite showed critical inhaler errors, reported a poor level of handling-related knowledge about its use, and exhibited low adherence to at-home inhaler treatment prior to hospitalization. This evidence highlights an important area for improvement in the use of inhalers among hospitalized patients with a high consumption of healthcare resources. Furthermore, our results point out the importance of evaluating patients' inhaled therapies, assessing their individual characteristics to match the device to their needs, and providing patient education and training about proper inhaler use.

Respiratory diseases are a major health problem and a major contributor to pharmaceutical expenditure, with inhaler prescriptions ranking among the highest in total drug costs [

17]. Despite the continuous innovations and the availability of numerous effective inhaled therapy options, inhaler misuse remains a significant challenge in managing chronic respiratory diseases, directly impacting disease outcomes[

14,

18]. Inhaled therapy is the cornerstone of respiratory disease management, however, the selection of the most appropriate inhaler and the assessment of its correct use is still ignored or underestimated by some healthcare professionals [

6,

7]. The 2021 EPOCONSUL audit of pulmonology practice revealed that inhalation technique was evaluated in less than half of the audited visits in patients treated in outpatient respiratory clinic [

19]. Clinical practice guidelines underline the relevance of assessing inhalation technique during follow-up and management of inhaled therapy. In addition, these guidelines recommend the prioritization of DPI devices over MDI, when possible, in patients with a PIF ≥30 L/min, due to their significant ease of use, lower frequency of critical inhaler errors, and reduced carbon footprint [

20,

21,

22].

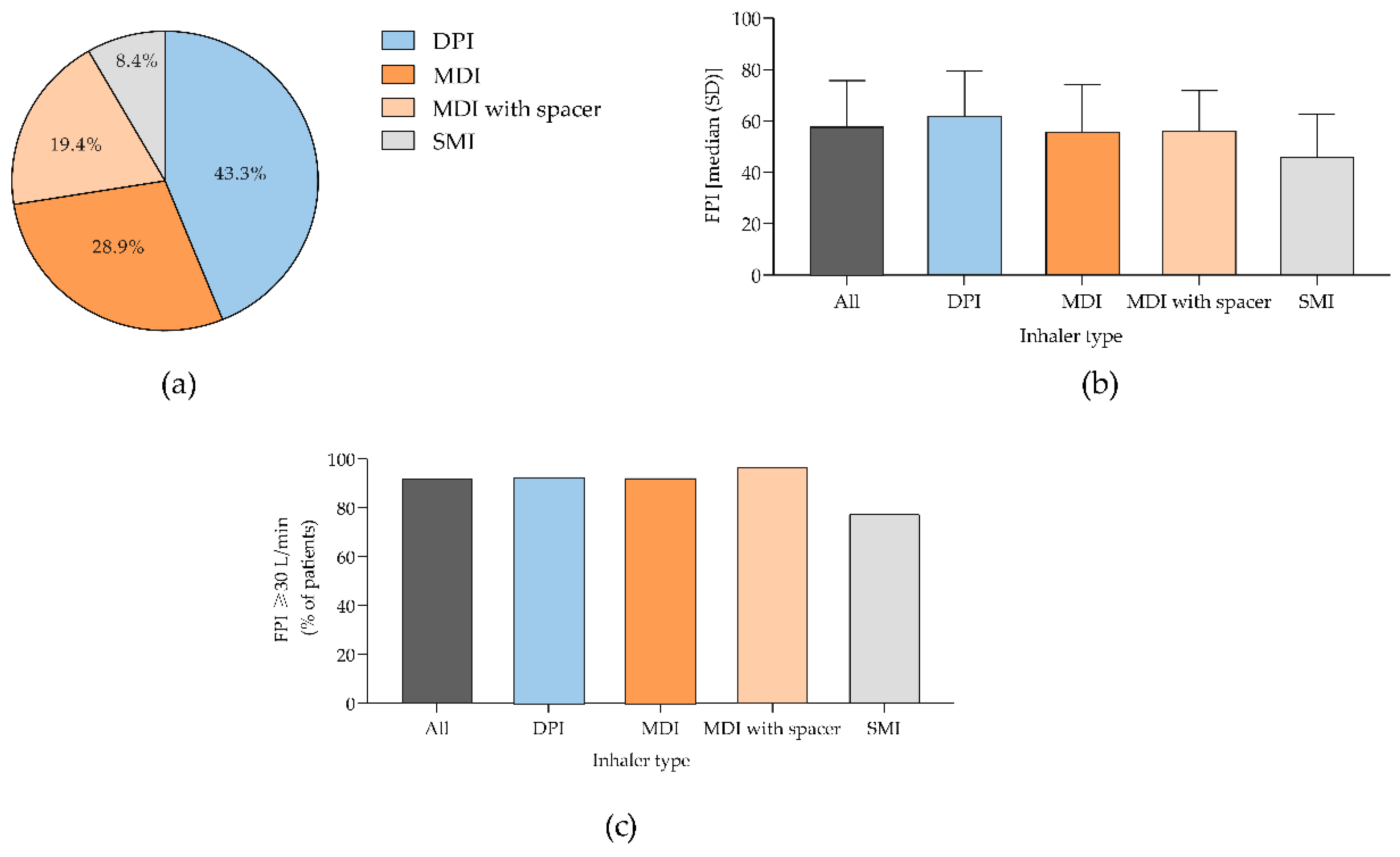

PIF is the maximum flow rate achieved during an inspiratory maneuver, being its evaluation an effective tool to help clinicians in selecting the most appropriate inhaler for each patient [

23,

24]. A maximum PIF of ≥30 L/min is considered to be sufficient for the effective use of most DPIs [

23]. So, patients with a PIF ≥30 L/min are theoretically more likely to benefit from using a DPI, as this flow rate is sufficient for effective aerosolization and drug delivery to the lungs [

23]. Studies have shown that the ability to generate a PIF of ≥30 L/min is independent of patient age or the severity of airway obstruction [

23]. In the selection of the most appropriate inhaler, the determination of PIF values may be a valuable tool to improve treatment outcomes [

25]. In our cohort, more than 90% of patients with a history of at-home inhaler use demonstrated a PIF ≥30 L/min, indicating they had adequate flow rates for optimal DPI performance. However, half of patients used an MDI with or without a space despite being a device associated with higher rates of misuse and with a significant carbon footprint [

10,

18]. Also, in the hospital setting, regardless of the history of inhaler use, the MDI with spacer chamber was the most commonly used device. In line, in clinical practice there is an increasing need for a more individualized inhaler selection to achieve optimal clinical outcomes. Routine PIF analysis can serve as a valuable and practical tool to guide this process, ensuring that the chosen inhaler is aligned with the patient’s needs and capabilities.

Personalized inhaler selection and continuous monitoring by healthcare professionals are essential. DPIs, in comparison to MDI, are generally associated with fewer critical errors due to their breath-actuated mechanism, which eliminates the need to coordinate actuation with inhalation [

10,

25,

26]. In patients with chronic use of inhaled therapy, critical inhaler errors are directly associated with poor disease outcomes, including increased use of MDI rescue medications, reduced quality of life, higher rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and greater dependence on oral steroids and antimicrobials [

14,

26,

27,

28,

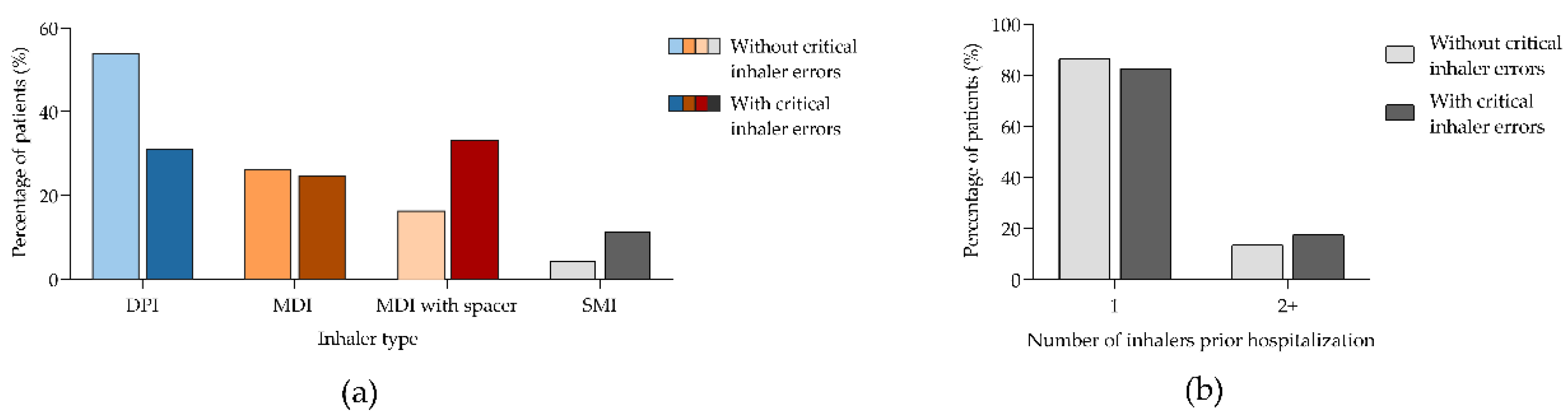

29]. In our cohort, we observed a high prevalence of critical inhaler errors, with one-third of patients demonstrating errors in inhaler handling. Our findings align with previous studies showing that inhalers are used incorrectly in 12–71% of cases [

18]. In fact, 38% of patients using MDIs demonstrated poor inhaler technique compared to 23% of those using DPIs [

12]. Moreover, patients using multiple types of inhalers are at a higher risk of critical errors. In contrast, the use of single and simple device inhalers, are often the best therapeutic option to minimize these errors and ensure the delivery of the drug dose during treatment [

30]. Interestingly, in our cohort nearly 90% of patients with good treatment adherence used only one device. A study also found that patients using multiple inhalers had a higher risk of exacerbations, as well as greater healthcare utilization and economic burden, compared to those using a single inhaler [

31]. Thus, the use of multiple inhalers is associated with lower compliance, and patient-reported confusion regarding their inhaled medication has been identified as an independent predictor of non-adherence to treatment [

32]. In our analysis, patients with critical inhaler errors were more likely to show poor inhaler compliance compared to those without critical errors (50.5% vs. 31%, respectively). Errors during this process can result in insufficient drug delivery to the lungs [

8].

Poor adherence and critical errors in inhaled therapies have previously been linked to an increased risk of rescue medication use and exacerbations, and higher mortality rates [

29]. The proper use of an inhaler device requires careful preparation and handling prior to inhalation, along with effective inhalation technique. Patient education and training are crucial to prevent critical errors in inhaler use, being a better knowledge of inhaler handling associated with fewer errors. In our real-world cohort, in patients with a higher burden of healthcare utilization and higher post-discharge mortality, we observed that more than 50% of patients with regular or poor knowledge had critical inhaler errors. However, a good knowledge of inhaler handling does not necessarily predict good compliance, as some patients may continue to misuse their inhalers despite proper training [

11]. In fact, while around 50% of patients in our study had good inhaler handling knowledge, more than 70% exhibited poor or intermediate compliance. The most common form of noncompliance was unconscious noncompliance, which aligns with previously reported evidence [

33]. Despite a good understanding of inhaler techniques, many patients still exhibit suboptimal adherence to prescribed therapy [

33]. Higher patient satisfaction with the inhaler, regardless of the medication received, correlates with better adherence [

27,

34,

35]. Shared decision-making during inhaler selection, in cooperation with patients, is the preferred approach to avoid critical inhaler errors, improve treatment compliance, and achieve optimal disease control [

18].

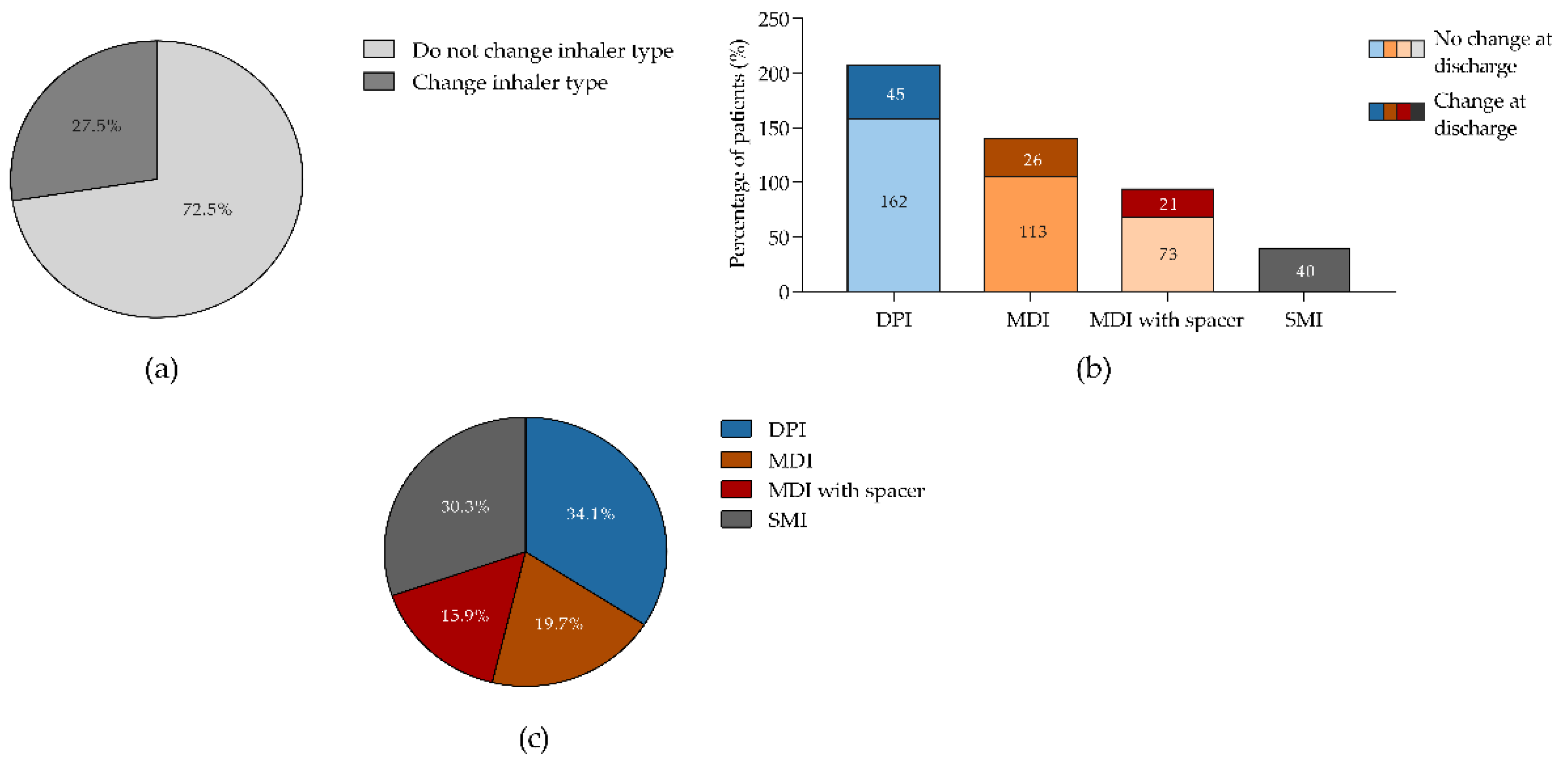

When evaluating device changes at discharge in patients on inhaled therapy prior to hospitalization, we found that only 27% of patients changed their inhaler type after hospitalization. This is interesting because a considerable percentage of patients made critical inhaler errors with their inhalers and used an MDI with a chamber, despite having a maximum PIF that would allow them to transition to a more user-friendly DPI. These results are even more remarkable if we consider that this population consisted of hospitalized patients with a high level of intervention due to their history of prior hospitalizations and a high risk of readmission and mortality. In COPD patient the 90 days following discharge is considered a period of relative instability, with an increased risk of hospital readmission or death [

36]. COPD has become one of the diseases with the highest rates of early readmission within 30 days, being one in five patients re-hospitalized within 30 days of discharge following an exacerbation admission [

37]. Approximately 50% of these readmissions could be avoided, as they often result from a fragmented healthcare system that provides inadequate discharge instructions, fails to educate patients about their therapy, and lacks effective communication with outpatient physicians responsible for follow-up care [

38].

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure to act when a patient does not achieve therapeutic objectives. These actions are not limited to initiating or intensifying therapy but also include evaluating potential aggravating factors, such as reviewing inhalation technique and assessing therapeutic adherence. Our analysis did not identify any significant association between patient characteristics, critical inhaler errors, handling-related knowledge, or maximum PIF values and changes in inhaler type. The only factor associated with a change was the type of therapy prescribed, being the double (LABA + ICS) or triple therapy (LAMA+LABA+ICS) associated with a higher likelihood of device change. The highest percentage of inhaler changes was observed among DPI users, although, more than half of the patients who made critical inhaler errors while using an MDI with a spacer did not have their inhaler type changed at discharge.

These findings suggest that clinicians possibly believe that the use of an inhalation chamber ensures a better drug delivery; although, our results show that these devices are often used with critical inhaler errors. Additionally, factors such as the patient's PIF, inhaler technique (critical inhaler errors and adherence), and the patient's level of knowledge about inhaler handling are frequently not considered in the decision to adjust treatment settings. This observation was highlighted by the results of the EPOCONSUL audit, which found that inhaled therapy is reviewed in less than half of follow-up visits [

19].

These data stress the importance of periodic review of inhaled therapies during follow-up, especially after hospitalization. In-hospital training interventions (e.g. systematic assessment of inhaler technique and PIF, combined with selection of an appropriate inhaler and provision of therapy education), are identified as a valuable strategy to improve the impact of hospitalization on relevant outcomes like readmission and mortality [

35]. Also, promoting nursing involvement in the assessment and education of inhaled therapy is a priority. This information provides an opportunity to implement interventions that will enhance the quality of care and outcomes in hospitalized patients under inhaled therapy.

The main strength of this study lies in its provision of novel information. However, several considerations must be taken into account to accurately interpret our results. The primary limitation, common to any real-life study, is the presence of missing values (data not available), regardless of the inclusion methodology and regular monitoring of the database. In our study, a number of patients could not be assessed for the interview measures due to repeated absences. Another important consideration is that PIF measurement was performed in patients hospitalized during an unstable phase, which may have led to an underestimation of the PIF, as studies show that PIF can decrease during exacerbations. Additionally, this is a single-center study, and therefore the results may not be representative of other populations. Despite these limitations, we believe the findings are consistent with those published on the use of inhaled therapy.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients included and evaluated in the AIRE study. PIF, peak inspiratory flow.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients included and evaluated in the AIRE study. PIF, peak inspiratory flow.

Figure 2.

Characterization of patient population according to the type of inhalator used prior hospitalization. (a) Percentage of patients; (b) Median absolute maximum PIF values and c) Percentage of patients with a maximum PIF ≥30 L/min. Panel (a) shows data from 499 patients from who 216, 144, 97 and 42 were using DPI, MDI, MDI with spacer and SMI prior hospitalization, respectively. Panel (b) and (c) shows data from 317 patients from whom 144, 81, 70 and 22 were using DPI, MDI, MDI with spacer and SMI prior hospitalization, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; PIF, peak inspiratory flow; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Figure 2.

Characterization of patient population according to the type of inhalator used prior hospitalization. (a) Percentage of patients; (b) Median absolute maximum PIF values and c) Percentage of patients with a maximum PIF ≥30 L/min. Panel (a) shows data from 499 patients from who 216, 144, 97 and 42 were using DPI, MDI, MDI with spacer and SMI prior hospitalization, respectively. Panel (b) and (c) shows data from 317 patients from whom 144, 81, 70 and 22 were using DPI, MDI, MDI with spacer and SMI prior hospitalization, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; PIF, peak inspiratory flow; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients according to performing inhaler critical errors or not. (a) By the type of inhaler used prior hospitalization; (b) By the number of inhalers used prior hospitalization. Panel (a) and (b) show data from 320 patients from whom 206 and 114 were performing or not critical inhaler errors, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients according to performing inhaler critical errors or not. (a) By the type of inhaler used prior hospitalization; (b) By the number of inhalers used prior hospitalization. Panel (a) and (b) show data from 320 patients from whom 206 and 114 were performing or not critical inhaler errors, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Figure 4.

Patients who changed inhalers after hospitalization. (a) Percentage of patients who changed or did not change their inhaler; (b) Percentage of patients who changed or did not change according to the type of inhaler used prior to hospitalization; (c) Frequency of device change at discharge according to the type of device used prior to hospitalization. Panel (a) and (b) shows data from 480 patients from who 132 and 348 change or not inhaler type after hospitalization, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Figure 4.

Patients who changed inhalers after hospitalization. (a) Percentage of patients who changed or did not change their inhaler; (b) Percentage of patients who changed or did not change according to the type of inhaler used prior to hospitalization; (c) Frequency of device change at discharge according to the type of device used prior to hospitalization. Panel (a) and (b) shows data from 480 patients from who 132 and 348 change or not inhaler type after hospitalization, respectively. DPI, dry powdered inhaler; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; SMI, soft mist inhaler. .

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographics and clinical characteristics according to the previous medical history inhaled therapy.

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographics and clinical characteristics according to the previous medical history inhaled therapy.

| |

|

With previous

history of inhaler use before

hospitalization |

Without previous history of inhaler use before

hospitalization |

| |

Patients included, n (%) |

499 (51.3) |

474 (48.7) |

| |

Age, median (SD) |

75.4 (12.4) |

79.2 (12.7) |

| |

Gender (men), n (%) |

243 (59.6) |

167 (49) |

| |

Current smoker, n (%) |

54 (10.8) |

25 (5.8) |

| |

Charlson index, median (SD)

Patients with Charlson index ≥2, n (%)

|

3 (1-4)

340 (67.9) |

2 (1-4)

301 (63.5) |

| |

Respiratory comorbidities, n (%)

Absence

COPD

Bronchiectasis

Asthma

Other |

66 (13.2)

268 (53.7)

40 (8)

89 (17.8)

36 (7.2) |

361 (76.2)

32 (6.8)

4 (0.8)

16 (3.4)

61 (12.9) |

| |

Number of hospitalizations in previous year, median (IQR)

Hospitalizations previous year ≥1, n (%)

|

2 (1-3)

388 (77.4) |

1 (0-2)

271 (57.2) |

| |

Antibiotic/corticosteroid courses in previous year, median (IQR)

Number of courses ≥2, n (%)

|

1 (0-3)

232 (46.5) |

0 (0-1)

103 (21.7) |

| |

Cause for therapy during admission, n (%)

COPD exacerbation

Asthma exacerbation

Bronchiectasis

Respiratory infection

Cardiac insufficiency |

205 (40.9)

17 (3.4)

10 (2)

218 (43.5)

43 (8.6) |

23 (4.9)

5 (1.1)

0

304 (64.1)

125 (26.4) |

| |

Inpatient service, n (%)

Internal medicine

Pulmonology

Geriatrics |

260 (52.1)

125 (25)

114 (22.8) |

279 (58.9)

35 (7.4)

160 (33.8) |

Inhaled therapy during hospitalization, n (%)

SABD

ICS+SABD

LAMA

LABA+LAMA

LABA+ICS

LABA+LAMA+ICS (single inhaler)

LABA+LAMA+ICS (multiple inhalers) |

246 (49.3)

96 (19.2)

30 (6)

17 (3.4)

35 (7)

66 (13.2)

9 (3.4) |

325 (68.6)

67 (14.1)

14 (3)

5 (1.1)

27 (5.7)

27 (5.7)

9 (1.9) |

Inhaler devices during hospitalization, n (%)

MDI (with spacer)

Nebulizer

MDI

DPI

SMI |

260 (51.9)

209 (41.7)

2 (0.4)

14 (2.8)

13 (2.6) |

219 (46.2)

248 (52.3)

1 (0.2)

1 (0.2)

5 (1.0) |

Mortality, n (%)

In-hospital

90 days |

18 (3.6)

108 (21.6) |

97 (20.5)

51 (10.8) |

Table 2.

Adherence to inhaled therapy prior hospitalization.

Table 2.

Adherence to inhaled therapy prior hospitalization.

| |

All

patients |

Patients using DPI |

Patients using MDI |

Patients

using MDI with spacer |

Patients using SMI |

| Patients included, n (%) |

279 (100) |

135 (48.4) |

68 (24.4) |

61 (21.9) |

15 (5.3) |

Inhaled therapy

compliance, n (%)

Poor

Intermediate

Good |

106 (38)

89 (31.9)

84 (30.1) |

51 (37.8)

47 (34.8)

37 (27.4) |

24 (35.3)

23 (33.8)

21 (30.9) |

23 (37.7)

16 (26.2)

22 (36.1) |

8 (53.3)

3 (20)

4 (26.7) |

Type of inhaler noncompliance, n (%)

Erratic

Deliberate

Unconscious |

165 (59.1)

35 (12.5)

266 (95.4) |

76 (56.3)

9 (6.6)

126 (93.3) |

43 (63.2)

7 (10.3)

66 (97.0) |

35 (57.4)

13 (21.3)

60 (98.3) |

11 (73.3)

6 (40)

14 (93.3) |

Table 3.

Patient compliance and knowledge regarding inhaler handling technique in patients with/without critical errors.

Table 3.

Patient compliance and knowledge regarding inhaler handling technique in patients with/without critical errors.

| |

Without critical inhaler errors |

With critical inhaler errors |

p-value |

| PIF, median (SD) |

60.8 (17.3) |

52.1 (17.8) |

<0.001 |

Inhaler compliance, n/N (%)

Poor

Intermediate

Good |

57/184 (31)

66/184 (35.9)

61/184 (33.2) |

46/91 (50.5)

22/91 (24.2)

23/91 (25.3) |

0.007 |

Inhaler handling-related knowledge, n/N (%)

Good

Regular or poor |

172/195 (88.2)

23/195 (11.8) |

49/99 (49.5)

50/99 (50.5) |

<0.001 |

Table 4.

Inhaled therapy prior hospitalization in patients with a maximum PIF <30 L/min or ≥30 L/min.

Table 4.

Inhaled therapy prior hospitalization in patients with a maximum PIF <30 L/min or ≥30 L/min.

| |

PIF ≥30 L/min |

PIF <30 L/min |

Inhaler device, n/N (%)

DPI

MDI

MDI with spacer

SMI

Unknown |

133/294 (45.2)

74/294 (25.2)

67/294 (22.8)

17/294 (6.8) 5.8

3/294 (1.0) |

11/27 (40.7)

7/27 (25.9)

3/27 (11.1)

5/27 (18.5)

1/27 (3.7) |

Number of inhalers, n/N (%)

1

2 |

252/294 (85.7)

42/294 (14.3) |

22/27 (81.5)

5/27 (18.5) |

| Treatment period, median (IQR) |

15 (7-40) |

25 (7-63) |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

96/294 (32.6) |

18/27 (66.7) |

Type of inhaler compliance, n/N (%)

Poor

Intermediate

Good |

98/253 (38.7)

84/253 (33.2)

71/253 (28.1) |

8/24 (33.3)

5/24 (20.8)

11/24 (45.8) |

Inhaler handling-related knowledge, n/N (%)

Good

Regular or poor |

212/272 (77.9)

60/272 (22.1) |

9/24 (37.5)

15/24 (62.5) |

Table 5.

Factors related patient's adherence to prescribed inhaler treatments.

Table 5.

Factors related patient's adherence to prescribed inhaler treatments.

| |

Good inhaler treatment

adherence |

Regular/poor

inhaler treatment adherence |

p-value |

Inhaler device, n/N (%)

DPI

MDI

MDI with spacer

SMI |

37/84 (44)

21/84 (25)

22/84 (26.2)

4/84 (4.8) |

98/195 (50.3)

47/195 (24.1)

39/195 (20)

11/195 (5.6) |

0.512 |

Number of inhalers, n/N (%)

1

2 |

74/84 (88.1)

10/84 (11.9) |

166/195 (8.1)

29/195 (14.9) |

0.052 |

Patients with maximum

PIF ≥30 L/min,

n/N (%)

|

70/84 (86.4) |

180 (93.8) |

0.868 |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

23/84 (27.4) |

68/195 (34.9) |

0.182 |

Inhaler handling-related knowledge, n/N (%)

Good

Regular or poor |

71/84 (84.5)

13/84 (15.5) |

146/193 (75.6)

47/193 (24.4) |

0.099 |

Table 6.

Factors associated with not changing inhaler type after hospitalisation.

Table 6.

Factors associated with not changing inhaler type after hospitalisation.

| |

OR |

95% CI |

p-value |

LAMA (ref)

LAMA+LABA

LABA+ICS

LABA+LAMA+ICS

|

1

0.876

0.391

0.369 |

-

0.422 – 1.817

0.182 – 0.838

0.178 – 0.764 |

-

0.722

0.016

0.007 |

| 1 single inhaler |

1.817 |

0.549 – 6.011 |

0.328 |

Table 7.

Patients with inhaler critical errors, PIF values and inhaler handling-related knowledge according to changing or not inhaler type after hospitalization.

Table 7.

Patients with inhaler critical errors, PIF values and inhaler handling-related knowledge according to changing or not inhaler type after hospitalization.

| |

Do not change inhaler type |

Change inhaler type |

| |

DPI prior

hospitalization

|

DPI prior hospitalization |

| |

|

Change to MDI |

Change

to MDI with spacer

|

Change to SMI |

| Patients included, n/N |

162/348 (46.6) |

35/45 (77.8) |

10/45 (22.2) |

0/45 (0) |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

28/110 (25.5) |

6/35 (22.2) |

1/10 (14.3) |

- |

| Patients with maximum PIF <30 L/min, n/N (%) |

10/160 (6.2) |

1/35 (3.7) |

0/10 |

- |

| Regular or poor inhaler handling-related knowledge, n (%) |

16/106 (15.1) |

4/35 (13.8) |

0/10 |

- |

| |

MDI prior

hospitalization

|

MDI prior hospitalization |

| |

|

Change to DPI |

Change

to MDI with spacer

|

Change to SMI |

| Patients included, n/N |

113/348 (32.5) |

14/26 (53.9) |

11/26 (42.3) |

1/26 (3.8) |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

22/64 (34.4) |

0 (0) |

4/11 (50) |

0 |

|

Patients with PIF <30 L/min, n/N (%)

|

5/63 (7.9) |

0 (0) |

1/11 (12.5) |

0 |

| Regular or poor inhaler handling-related knowledge, n (%) |

21/61 (34.4) |

1/14 (16.7) |

4/11 (50) |

1 (100) |

| |

MDI with spacer prior

hospitalization

|

MDI with spacer prior hospitalization |

| |

|

Change to DPI |

Change

to MDI

|

Change to SMI |

| Patients included, n/N |

73/348 (21.0) |

8/21 (38.1) |

13/21 (61.9) |

0/21 |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

29/54 (53.7) |

2/7 (28.6) |

6/9 (66.7) |

- |

|

Patients with PIF <30 L/min, n/N (%)

|

3/54 (5.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

- |

| Regular or poor inhaler handling-related knowledge, n (%) |

17/49 (34.7) |

1/6 (16.7) |

2/6 (33.3) |

- |

| |

SMI prior hospitalization |

SMI prior hospitalization |

| |

|

Change to DPI |

Change

to MDI

|

Change to MDI with spacer |

| Patients included, n/N |

- |

13/40 (32.5) |

6/40 (15.0) |

21/40 (52.5) |

| Patients with critical inhaler errors, n/N (%) |

- |

4/8 (50) |

1/3 (33.3) |

8/11 (72.7) |

|

Patients with PIF <30 L/min, n/N (%)

|

- |

1/8 (12.5) |

1/3 (33.3) |

3/11 (27.3) |

| Regular or poor inhaler handling-related knowledge, n (%) |

- |

3/8 (37.5) |

0 (0) |

4/7 (57.1) |