Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The main objective of the study was investigating the level of adoption and perception of irrigated wheat production in North Shewa Zone of Oromia Regional State. This study combined a qualitative and quantitative research approach with a descriptive research design and a cross-sectional survey type. Multi-stage sampling techniques were also used in the study to choose sample households. Both primary and secondary data were employed. Statistical Package for Social Science Version 20 was utilized to analyse the data using simple descriptive statistics. According to the study's findings, the majority of smallholder farmers expressed dissatisfaction with the extension services provided by DA. They also expressed disapproval of the availability of water sources for irrigated wheat production in the study area, as well as with access to credit services, necessary inputs, technical training on irrigated wheat, and irrigation facilities provided by the government. On the other hand, they confidently agreed that the government program encourages us to cultivate wheat under irrigation, and that the yields from this method are better than those from rainfed wheat. The finding of the study revealed that the overall level of adoption of irrigated wheat producers was low in the study area. In order to better align investments on irrigated wheat production, the study concludes that this new initiative knowledge should be useful through the development of a regular input supply system, the improvement of farmers' skills and knowledge, the development of modern schemes, the development of new disease-resistant varieties, and the strengthening of market linkage by experts, policymakers, researchers, and seed enterprises.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

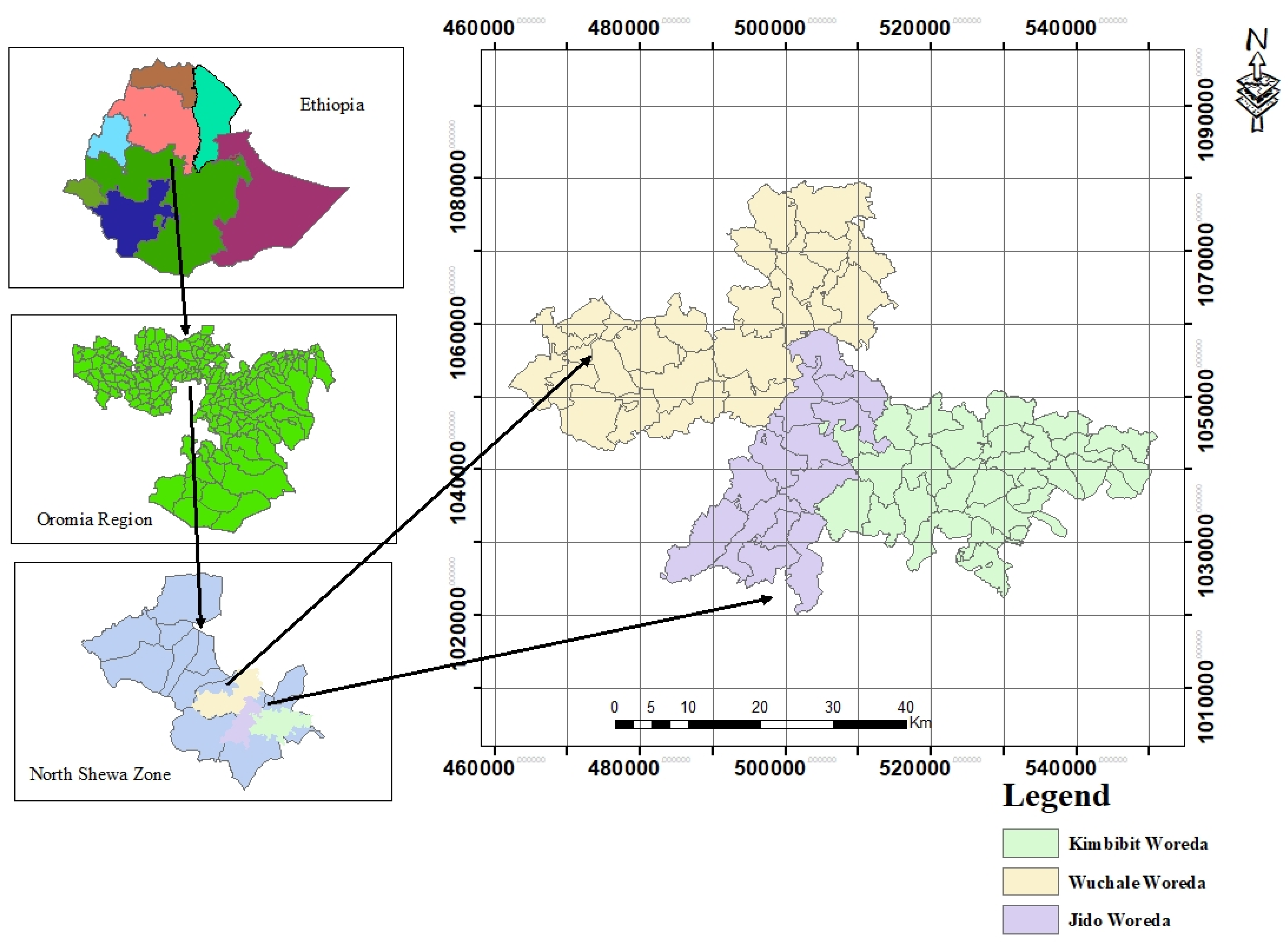

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Sampling Technique, Procedures and Sample Size Determination

2.4. Data Types, Source and Method of Data Collection

2.5. Method of Data Processing and Analysis

3. Result and Discussions

3.1. Perception of Farmers Towards Irrigated Wheat Production

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev |

| Irrigated wheat production was most effective than rainfed | 3.2891 | 1.43703 |

| There were satisfaction on access to extension service given by DA | 2.6719 | 1.51809 |

| There was access to credit services in the area | 2.3281 | 1.42218 |

| There was access to necessary inputs(for irrigation wheat production) | 1.9297 | 1.18421 |

| Positive perception of technology on the irrigated wheat production | 3.3281 | 1.44766 |

| There was access technical training on irrigated wheat | 3.1927 | 1.50520 |

| There was access to irrigation facilities from government | 2.3125 | 1.32312 |

| There was scarcity of water source for irrigated wheat production | 3.9141 | 1.36744 |

| Government initiative motivate me to produce irrigated wheat | 3.4505 | 1.52015 |

| The capacity of wheat yields is good than rainfed | 3.1927 | 1.45043 |

3.2. Farm Household Level of Adoption of Irrigated Wheat Production

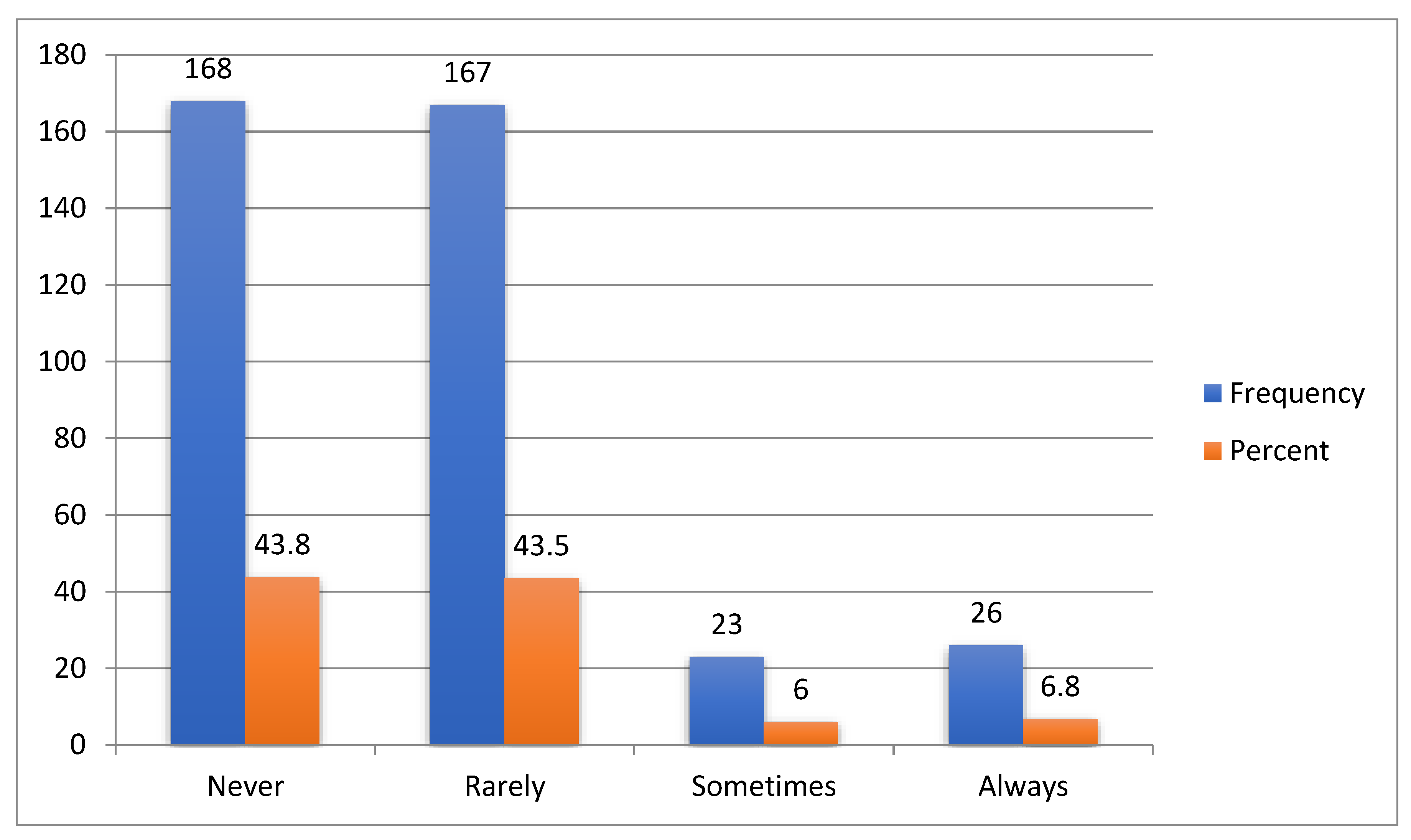

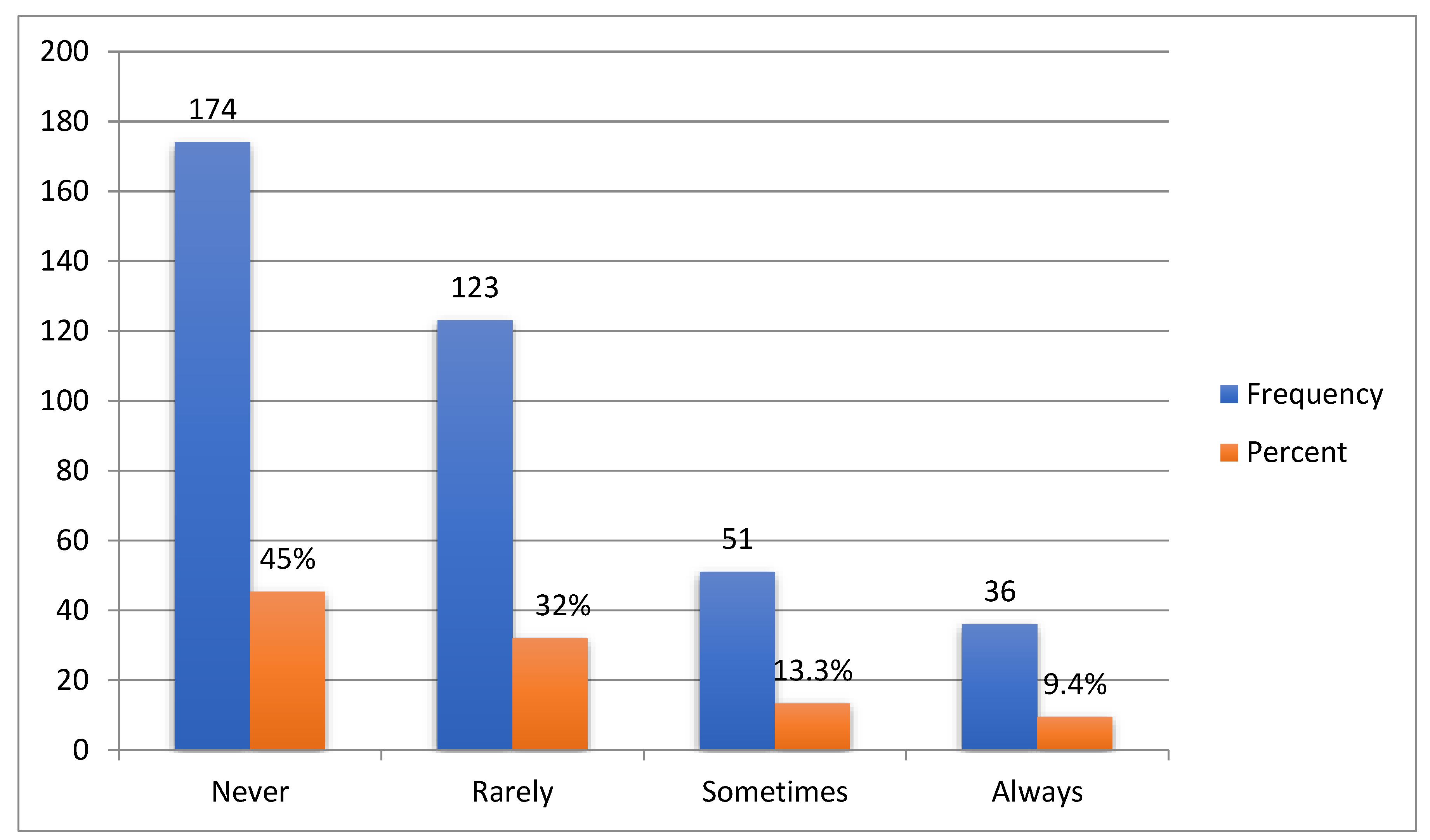

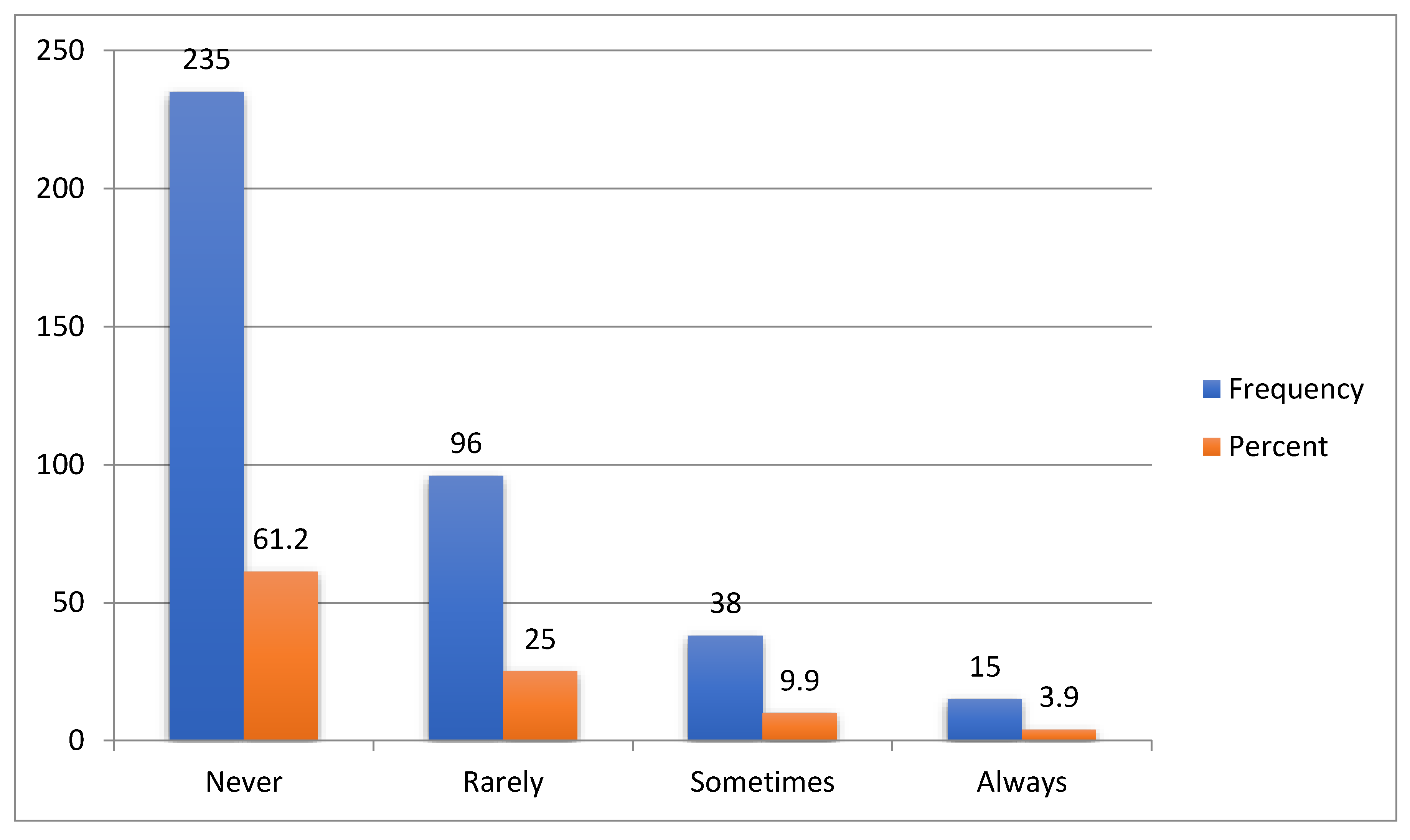

3.2.1. Field Preparation: Prepare the Land to Fine Beds and Channels

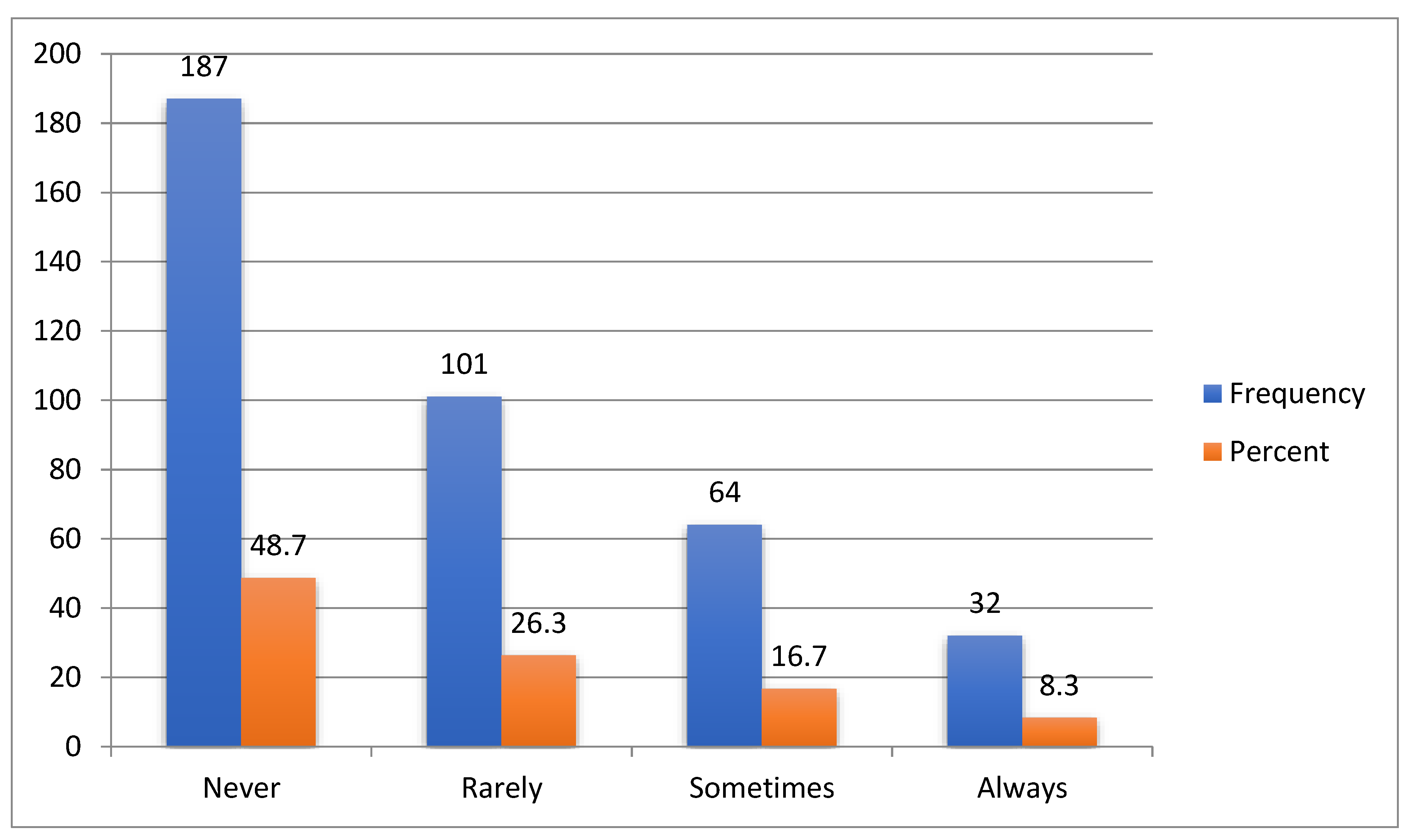

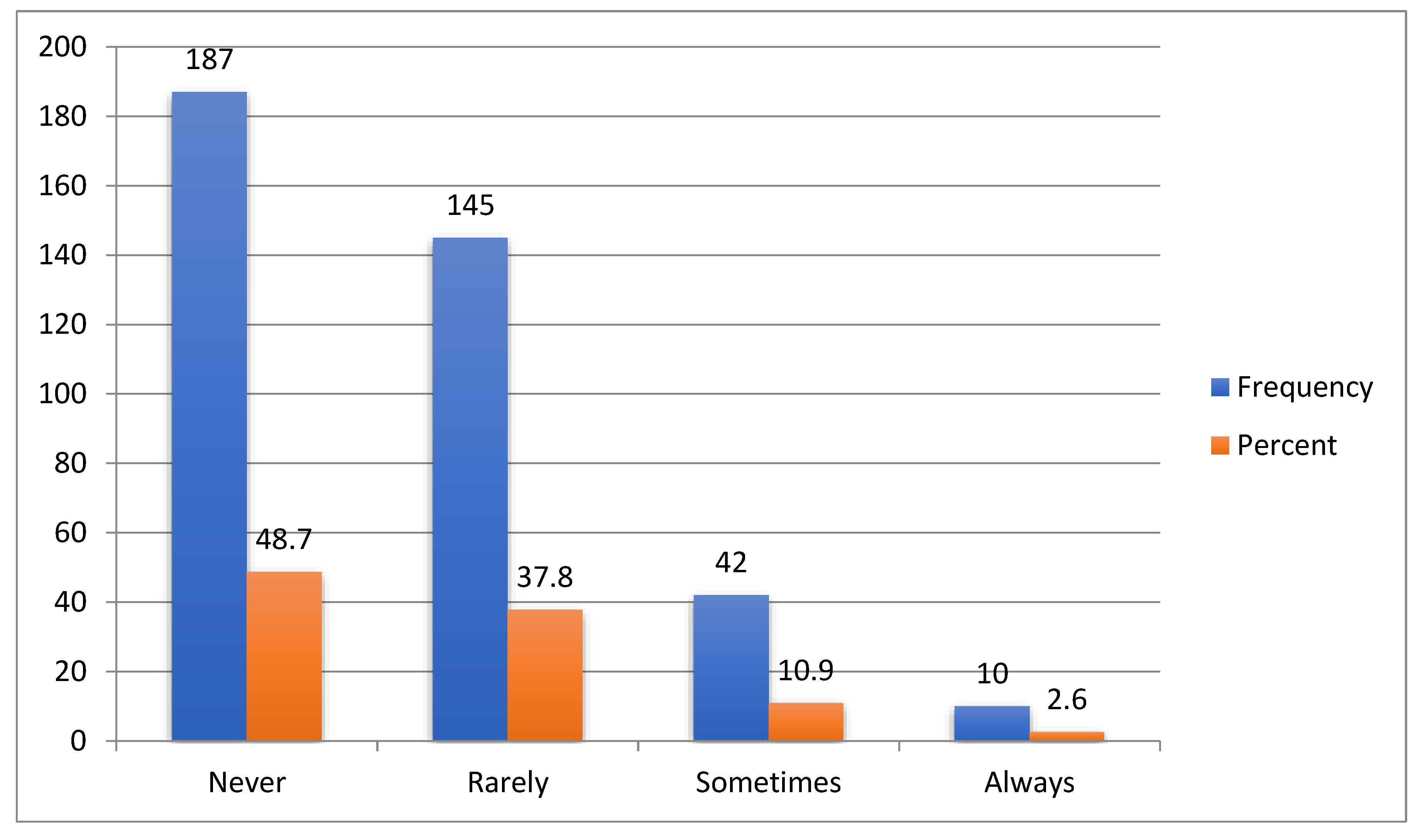

3.2.2. Beds and Channel Preparation and Clearing

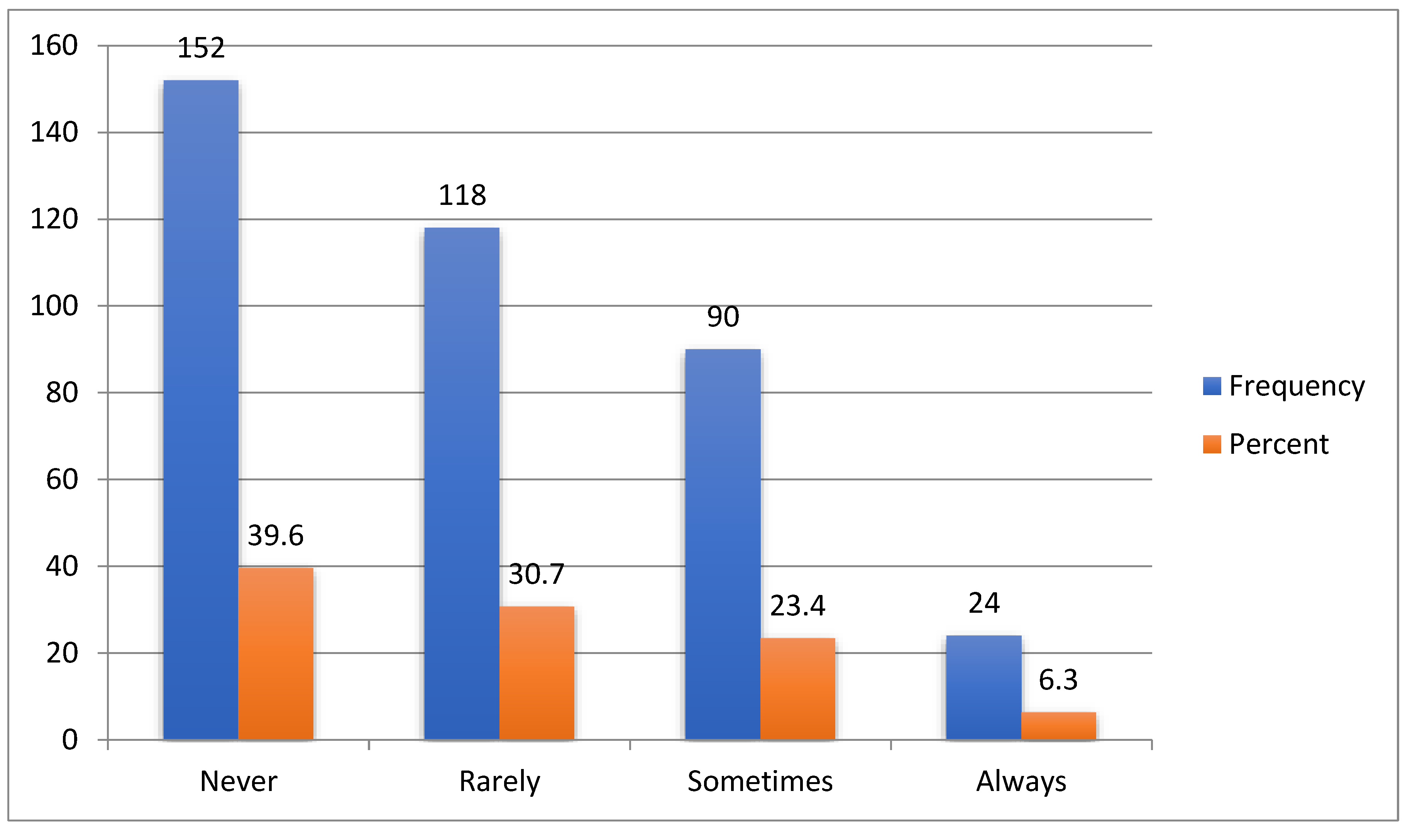

3.2.3. Use of High Yielding Varieties of Wheat Seeds

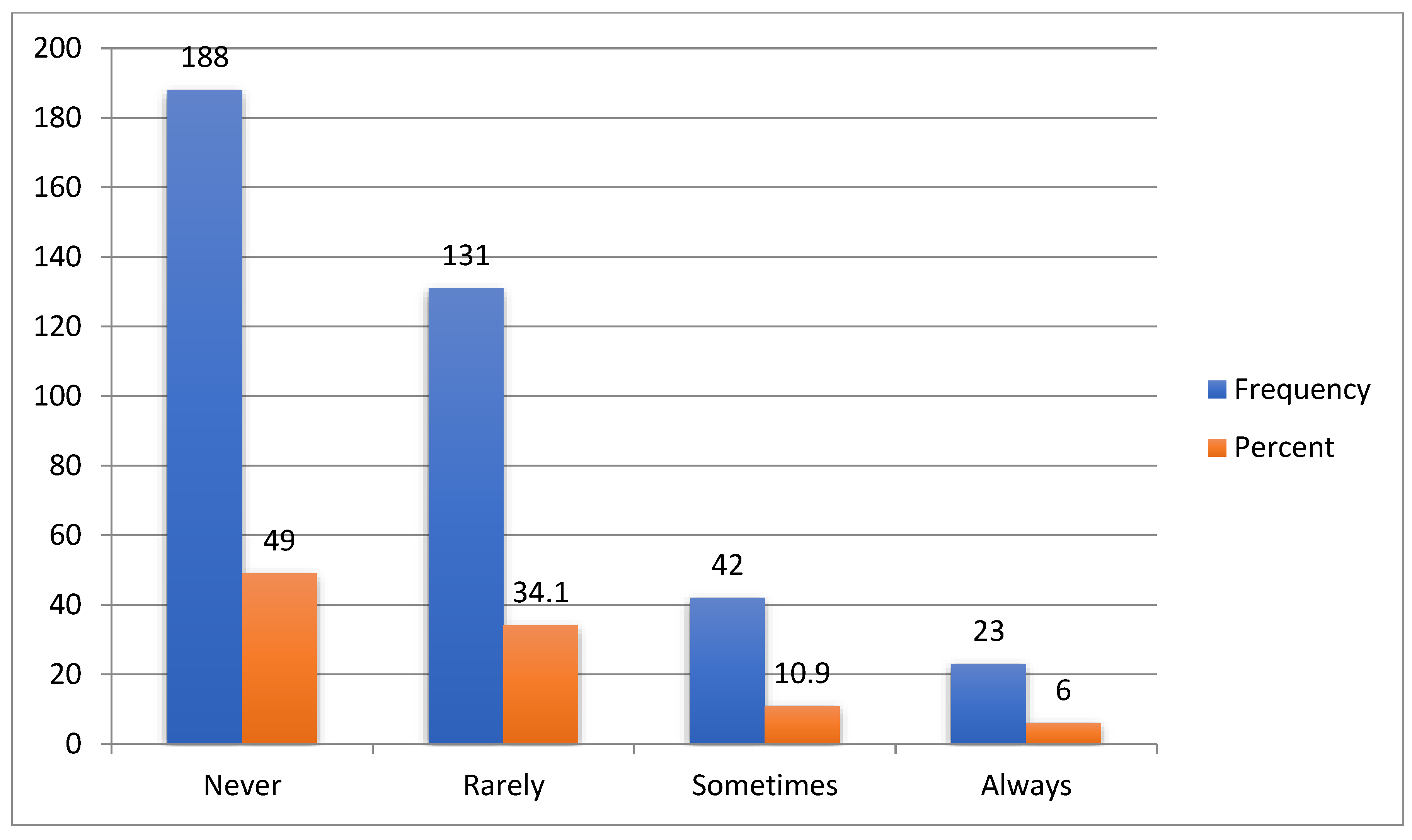

3.2.4. Right Time of Sowing

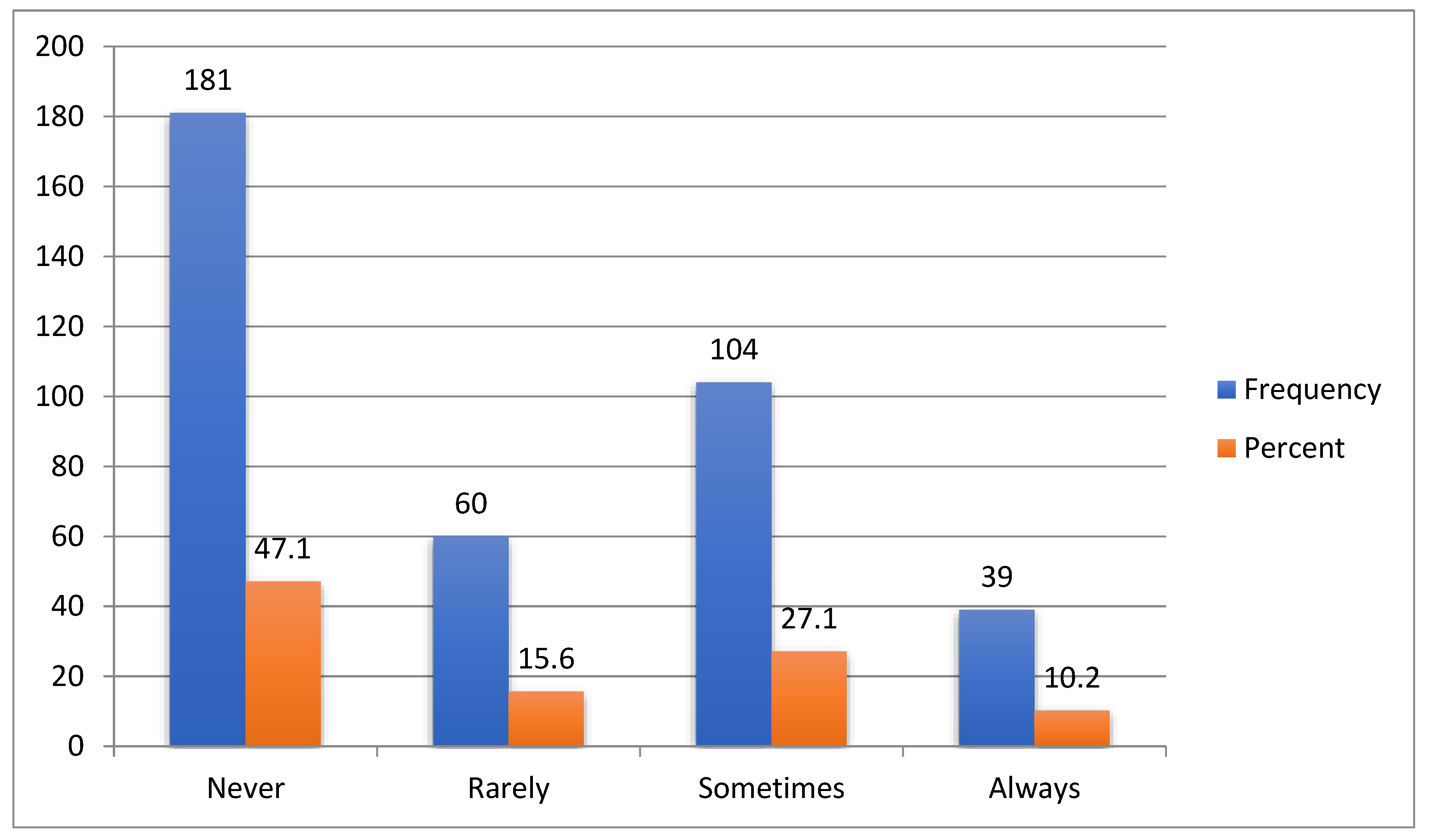

3.2.5. Use of Row Planting Technology

3.2.6. Right Time of Watering

3.2.7. Organic Manure and Fertilizer Application

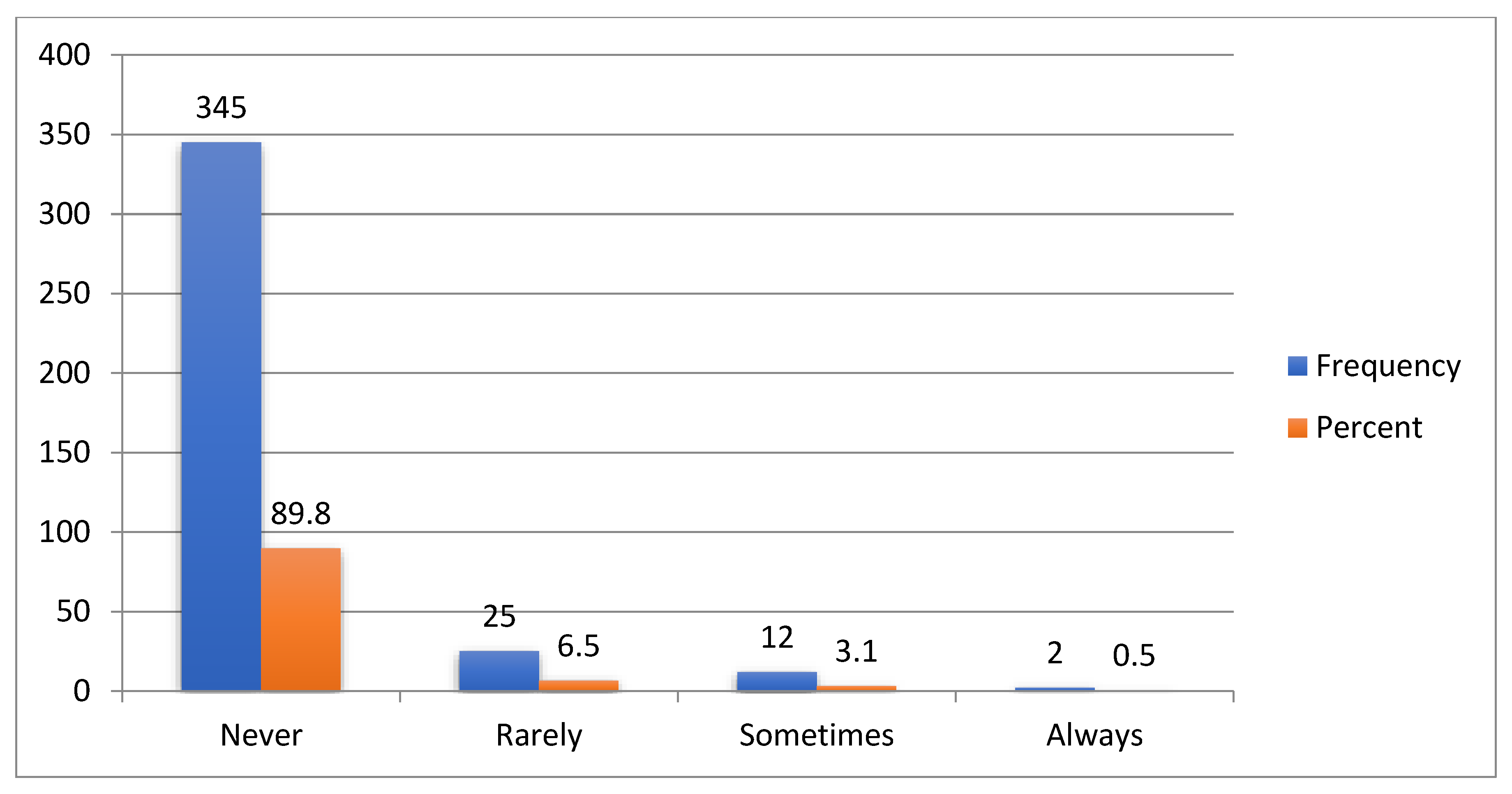

3.2.8. Seed Treatment

3.2.9. Soil Treatment

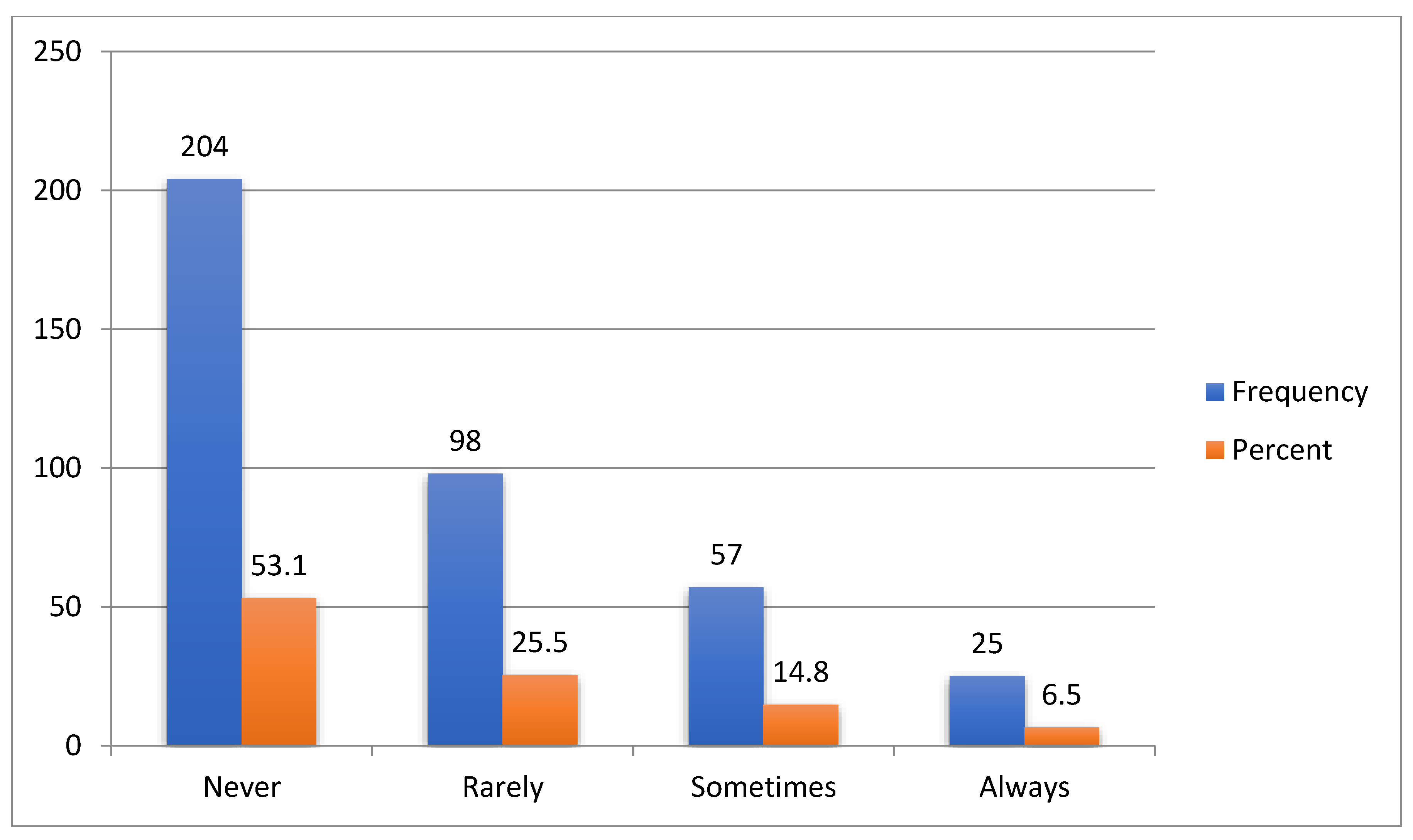

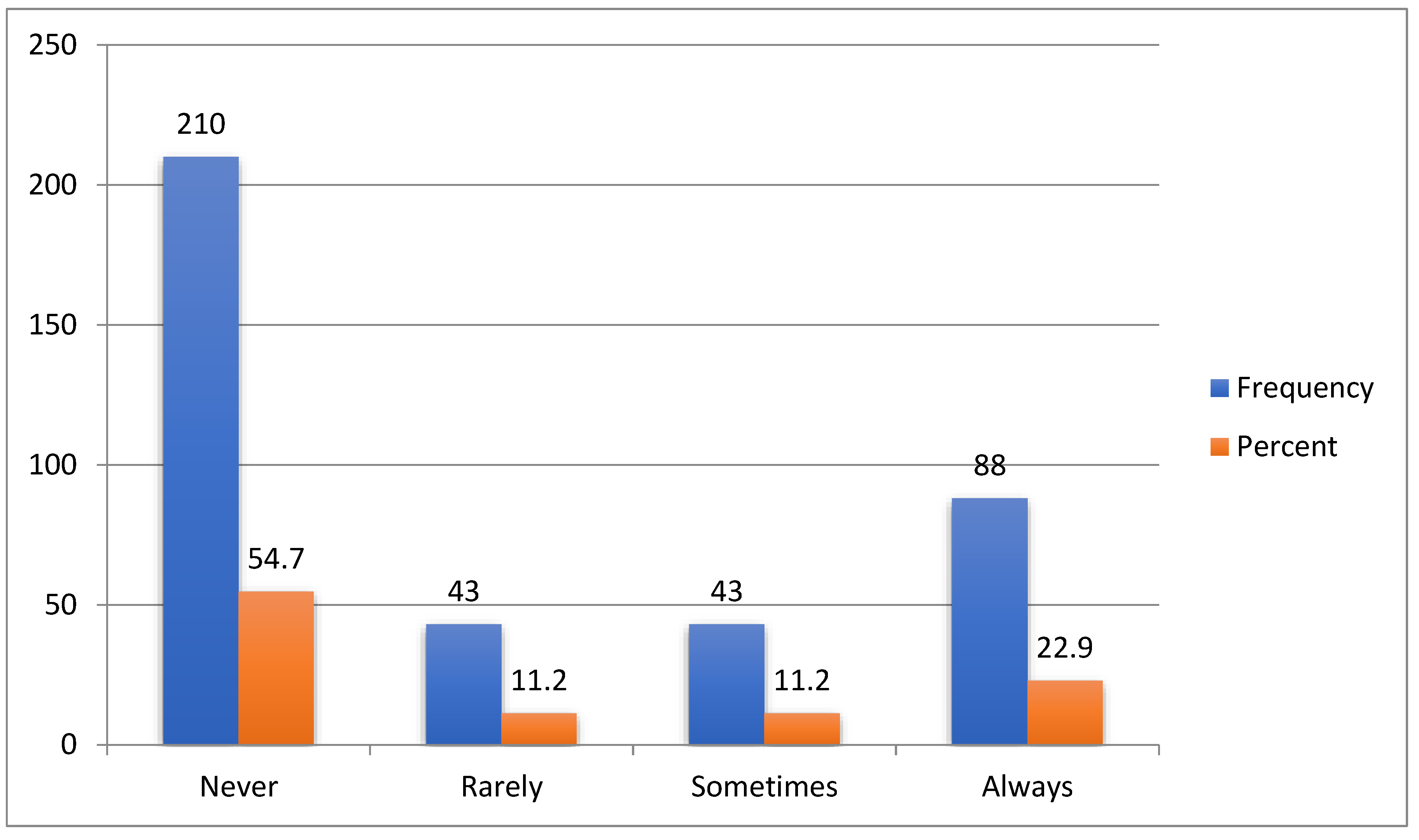

3.2.10. Weed Management

3.2.11. Right Time of Harvesting and Storage

| Irrigated wheat production technology practices | N | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Field preparation: Prepare the land to fine beds and channels | 384 | .29 | .323 |

| beds and channels | 384 | .25 | .280 |

| Use of high yielding varieties of wheat seeds | 384 | .28 | .326 |

| Right time of sowing | 384 | .32 | .311 |

| Use of row planting technology | 384 | .24 | .292 |

| Right time of watering | 384 | .19 | .273 |

| Organic manure and fertilizer application | 384 | .22 | .256 |

| Seed treatment | 384 | .19 | .272 |

| Soil treatment | 384 | .33 | .356 |

| Weed management | 384 | .34 | .4183 |

| Right time of Harvesting and Storage | 384 | .25 | .311 |

| AD.LEVEL | 384 | .2634 | .15121 |

4. Conclusion and Recommendation

References

- Abate, D., 2018. Review on market chain analysis of wheat in Ethiopia. The International Journal of Business Management and Technology, 2(6), pp.94-105.

- Abera, W., Tamene, L., Tesfaye, K., Jiménez, D., Dorado, H., Erkossa, T., ... & Ramirez-Villegas, J. (2022). A data-mining approach for developing site-specific fertilizer response functions across the wheat-growing environments in Ethiopia. Experimental Agriculture, 58, e9. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, V. O. (2023). A Review on Primary Sources of Data and Secondary Sources of Data.

- Alemu, T. (2024). Wheat Production and Consumption Trends and Prospects in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 34(1), 1-15.

- Alemu, Y., & Tolossa, D. (2022). Livelihood impacts of large-scale agricultural investments using empirical evidence from shashamane rural district of oromia region, Ethiopia. Sustainability, 14(15), 9082. [CrossRef]

- Asrat, D., Anteneh, A., Adem, M., & Berhanie, Z. (2022). Impact of Awash irrigation on the welfare of smallholder farmers in Eastern Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2024722. [CrossRef]

- Atinafu, A., Lejebo, M., & Alemu, A. (2022). Adoption of improved wheat production technology in Gorche district, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 11(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C. B., Reardon, T., Swinnen, J., & Zilberman, D. (2022). Agri-food value chain revolutions in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(4), 1316-1377. [CrossRef]

- Bekele Gemechu, B. G., Amha Besufekad, A. B., & Abate Mekuriaw, A. M. (2019). Performance evaluation of improved bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties and production technologies in Central High Lands of Ethiopia.

- Belay, F. Baye D., & Bezabeh, E. (2019). Impact of improved wheat technology package Adoption on productivity in Ethiopia. Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 9(1), 76-85.

- Bentley, J. Donovan, K. Sonder, F. Baudron, J.M. Lewis, et al., Near-to long-term measures to stabilize global wheat supplies and food security, Nature Food 3 (7) (2022) 483–486. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2021). The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Agricultural Sample Survey 2020/21 (2013 E.C.).

- CSA, Agricultural sample survey 2020/21(2013 E.C.) (september – December, 2020). Report on farm management practices (private peasant holdings, meher season), THE Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa (2020) 534.

- Damianus, A., Ranay, F., Magallanes, T., & Encarnacion, M. (2022). The effect of corporate governance on the individual work performance of employees. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478), 11, 82-98. [CrossRef]

- Dessie, A. B., Abate, T. M., & Mekie, T. M. (2018). Factors affecting market outlet choice of wheat producers in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 7, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Devlet, A. (2021). Modern agriculture and challenges. Frontiers in Life Sciences and Related Technologies, 2(1), 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Effa, K., Fana, D. M., Nigussie, M., Geleti, D., Abebe, N., Dechassa, N., ... & Berisso, F. E. (2023). The irrigated wheat initiative of Ethiopia: a new paradigm emulating Asia’s green revolution in Africa. Environment, Development and sustainability, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Endalew B, Anteneh A, Tasie K. (2022). Technical Efficiency of Teff Production Among Smallholder Farmers: Beta Regression Approach. Eur J Dev Res., 34(2):1076-1096. [CrossRef]

- Endalew, B., Aynalem, M., Assefa, F., & Ayalew, Z. (2020). Determinants of wheat commercialization among smallholder farmers in Debre Elias Woreda, Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2020(1), 2195823. [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O., Jaleta, M., Mottaleb, K. A., Sonder, K., Donovan, J., & Braun, H. J. (2022). Global trends in wheat production, consumption and trade. In Wheat improvement: food security in a changing climate (pp. 47-66). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- FAO. 2017. FAOSTAT FAO, Rome, available at: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed August 2021).

- Faostat, (2020). Database of Agricultural Production, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2020. Available from: http://faostat.fao.org/ default.aspx.

- FAOSTAT. (2022). Food Outlook – Biannual Report on Global Food Markets. Food Outlook, November 2022. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T., Ammar, K., Monasterio, I. O., Monjardino, M., Singh, R., & Verhulst, N. (2022). Sixty years of irrigated wheat yield increase in the Yaqui Valley of Mexico: Past drivers, prospects and sustainability. Field Crops Research, 283, 108528. [CrossRef]

- GAIN. (2021). Ethiopia grain and food manual report. Ethiopia Grain Trade Enterprise.

- Galvao, A. R., Mascarenhas, C., Marques, C. S., Braga, V., & Ferreira, M. (2020). Mentoring entrepreneurship in a rural territory–A qualitative exploration of an entrepreneurship program for rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 314-324. [CrossRef]

- Game, A. T., & Korecha, D. (2015). Recent changes in rainfall, temperature and number of rainy days over Northern Oromia Zone, Ethiopia. Science Discovery, 3(6), 62-70. [CrossRef]

- Gebreegziabher, W., Dilnesaw, Z., Hailu, T., Tadesse, M., & Berhe, M. (2018). Adaptation and Promotion of Irrigated Wheat Genotypes at Tendahoo Sugar Factory, Afar Regional State of Ethiopia. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci, 5(10), 70-83.

- Gebremariam, T. K., & Ying, S. (2022). The foreign direct investment-Export performance nexus: An ARDL based empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2009089. [CrossRef]

- Geleta, T., Debele, T., Gemechu, B., Kaske, K., Kifle, T., & Homma, S. (2024). National Wheat Seed Roadmap for Ethiopia. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383908118.

- Hassen, J. M., & Borana, F. R. (2024). Determining Irrigation Frequency and Water Amount for Irrigated Wheat Production in Amibara, Afar Region, Ethiopia. [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M. Jaleta, K. Tesfaye, C. Yirga, H. Beyene, et al., Ethiopia’s transforming wheat landscape: tracking variety use through DNA fingerprinting, Sci. Rep. 10 (1) (2020) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Isinika, A., Mlay, G., Mdoe, N., Boniface, G., & Saha, A. (2022). Is Agricultural commercialisation sufficient for poverty reduction? Lessons from rice commercialisation in Kilombero, Tanzania.

- Jambo, Y., Alemu, A., & Tasew, W. (2021). Impact of small-scale irrigation on household food security: evidence from Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 10, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Kifle T, Ayal DY, Mulugeta M. (2022). Factors influencing farmers adoption of climate smart agriculture to respond climate variability in Siyadebrina Wayu District, Central highland of Ethiopia. Climate Services, 26:100290. [CrossRef]

- Krupnik TJ, Schulthess U, Ahmed ZU, McDonald AJ. (2017). Sustainable crop intensification through surface water irrigation in Bangladesh? A geospatial assessment of landscape-scale production potential. Land use policy, 60(2017):206–222. [CrossRef]

- Mengistu DD, Degaga DT, Tsehay AS. (2021). Analyzing the contribution of crop diversification in improving household food security among wheat dominated rural households in Sinana District, Bale Zone, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Milkias, D. and Muleta, G., (2021). International Journal of Agriculture and Biosciences. Int J Agri Biosci, 10(2), pp.94-100.

- Minot, N., Warner, J., Lemma, S., Kasa, L., Gashaw, A., & Rashid, S. (2019). The wheat supply chain in Ethiopia: Patterns, trends, and policy options. Gates Open Res, 3(174), 174. [CrossRef]

- Nakawuka P, Langan S, Schmitter P, Barron J. (2018). A review of trends, constraints and opportunities of smallholder irrigation in East Africa. Global Food Security, 17(11):196 212.

- Nardi, P.M., 2018. Doing survey research: A guide to quantitative methods. Routledge.

- Noort MWJ, Renzetti S, Linderhof V, du Rand GE, Marx-Pienaar NJMM, de Kock HL, Magano N, Taylor JRN. (2022). Towards Sustainable Shifts to Healthy Diets and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa with Climate-Resilient Crops in Bread-Type Products: A Food System Analysis. Foods, 11(2):135. [CrossRef]

- NSHZAO (North Shawa Zone Agricultural office), (2022). Socio-economic data of North Shawa Zone, Fiche Salale. Unpublished data.

- NSHZFEDO (North Shawa Zone Finance and Economic Development Office), (2022). Socio-economic profile of North Shawa Zone, Fiche Salale. Unpublished material.

- Ozkan B, Dube AK, Reed MR. (2022). Role of Agricultural Extension in Building Climate Resilience of Food Security in Ethiopia. In: Food Security & Climate-Smart Food System, Cham: Springer International Publishing: 219-239.

- Regasa MS, Nones M, Adeba D. (2021). A Review on Land Use and Land Cover Change in Ethiopian Basins. Land, 10(6):585. [CrossRef]

- Senbeta, A. F., & Worku, W. (2023). Ethiopia’s wheat production pathways to self-sufficiency through land area expansion, irrigation advance, and yield gap closure. Heliyon.

- Shikur, Z. H. (2020). Agricultural policies, agricultural production and rural households’ welfare in Ethiopia. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(1), 50. [CrossRef]

- Shumeta, Z. (2024). National Wheat Seed Roadmap For Ethiopia.

- Tadesse, W., Bishaw, Z., & Assefa, S. (2018). Wheat production and breeding in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and opportunities in the face of climate change. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 11(5), 696-715.

- Tiruye, A. E., Asres Belay, S., Schmitter, P., Tegegne, D., Zimale, F. A., & Tilahun, S. A. (2022). Yield, water productivity and nutrient balances under different water management technologies of irrigated wheat in Ethiopia. PLoS Water, 1(12), e0000060. [CrossRef]

- USDA, (2022). Ethiopia Wheat Area, Yield and Production, Foreign Agriculture Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 2022.

- Viana, C. M., Freire, D., Abrantes, P., Rocha, J., & Pereira, P. (2022). Agricultural land systems importance for supporting food security and sustainable development goals: A systematic review. Science of the total environment, 806, 150718. [CrossRef]

- Vichea, S. (2005). Key factors affecting the performance of foreign direct investment in Cambodia (Doctoral dissertation, Doctoral dissertation, a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Masters of Business Administrations, university of the Tai chamber of commerce).

- Wondim, G.B., Kedir, A. and Musema, R., (2020). Adoption of irrigated wheat varieties among agro-pastoralists; the case of Fentale District, Upper Awash Valley of Northeastern Ethiopia. African Journal of Agriculture and Food Security ISSN, 8(12), pp.001-010.

- Wordofa MG, Hassen JY, Endris GS, Aweke CS, Moges DK, Rorisa DT. (2021). Adoption of improved agricultural technology and its impact on household income: a propensity score matching estimation in eastern Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Zegeye MB, Fikrie AH, Asefa AB. (2022). Impact of agricultural technology adoption on wheat productivity: Evidence from North Shewa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1). 2101223. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).