1. Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly transmissible RNA virus responsible for the pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [

1]. First emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, this respiratory virus is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets [

2]. The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been attributed to person-to-person contact, the inconsistent use of face masks, inadequate sanitary measures, and limited access to vaccines in many regions [

1].

Due to the significant genetic variability and widespread transmission, multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants have emerged, leading to distinct epidemics that have occurred concurrently or successively [

3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes these variants into three main groups: Variants of Concern (VOCs), Variants of Interest (VOIs), and Variant Under Monitoring (VUMs) [

4]. These classifications are based on factors such as genetic mutations, transmissibility, disease severity, and ability to evade immune response elicited by current vaccines, convalescent plasma treatments, or the use of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies [

1].

The dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 variants across the globe underscores the importance of understanding both local and global transmission patterns. Such insights are crucial for informing public health policies. While genomic surveillance has been widely implemented globally, the accumulation of SARS-CoV-2 genomic data in West sub-Saharan Africa, including Guinea, has been slow [

5]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, several variants exhibited extensive genomic mutations compared to the original Wuhan-01 strain, leading to increased viral infectivity and potential immune escape in humans [

3]. Although the pandemic has been ongoing for more than three years, our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants has improved significantly. The clinical and genetic information gathered during this time has been invaluable to global public health [

6].

Viral evolution occurs through the gradual accumulation of mutations over generations, adapting to host environments. However, in some cases, a cluster of mutations can appear simultaneously, resulting in a sudden jump in viral evolution [

7]. Omicron, the most divergent VOC to date, exemplifies this phenomenon. It has spread rapidly and unpredictably, reminiscent of the Delta variant’s outbreak that emerged in India in 2021 [

8,

9,

10]. Most VOCs and VOIs including Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, Eta, Iota, Kappa, and Lambda were first identified across multiple countries in 2020, while the Mu and Omicron variants were detected in 2021 [

1]. It is important to note that while viruses constantly evolve, not all mutations result in increased transmissibility or severity. Understanding the mutation patterns of SARS-CoV-2 is crucial for developing effective vaccines and treatments for COVID-19 [

11].

In Guinea, as in many sub-Saharan African countries, four main waves of COVID-19 epidemics have been observed, with a cumulative total of 38 572 confirmed cases and 468 deaths (Worldometers.info). The first COVID-19 case in Guinea was identified on 12 March 2020 in a traveler from Europe [

12]. The origin of this index case was linked to the traveler’s history. Still, the probable origins of the subsequent VOCs or VOIs that circulated during the pandemic remain unexplored.

Data on the origins of these variants or their evolution based on genomic data in Guinea are very limited. This study aimed to fill this gap by performing bioinformatics, phylogenetic, and phylogeographic analyses on large genomic sequences obtained from the international GISAID database. We described the genetic diversity, evolution, and origin of SARS-CoV-2 VOCs circulating in Guinea during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data collection

This was an analysis of genomic data of SARS CoV-2 from GISAID between March 2020 and December 2023. To perform the phylogenetic and phylogeography analysis on all variants of concern (VOC) and variants of interest (VOI) identified in Guinea during the active COVID-19 pandemic, we retrieved and downloaded as background data from GISAID the sequences compiled for each lineage (Alpha (B.1.1.7), Delta (B.1.617.2), Eta (B.1.525), and Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1, and XBB}) by Emma Hodcroft and collaborators on [

https://covariants.org/]. Each dataset (Guinea sequences representing the query and global sequences representing the background) includes outgroup sequences from earlier lineages that previously circulated. All sequences were downloaded on December 17th, 2023. All sequences generated in Guinea were selected and merged with the background data. We included all Guinea sequences in our analysis, irrespective of the laboratory of origin or the sequencing platform used.

2.2. Phylogeography reconstruction

For each dataset, we retrieved background sequences that reflected the sampling period of each VOC (first and last sampling date) in Guinea. We then aligned the background sequences against Guinean sequences using Nextalign v2.14.0. The aligned sequences were visualized and edited using a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor suitable for large datasets [

13]. To minimize ambiguities, we masked 100 to 150 base pairs from the beginning and the end of each sequence.

Maximum likelihood trees for each alignment were inferred in IQ-TREE multicore version 2.2.6 COVID-edition using the Ultrafast model selection [

14]. All trees were inferred with a general time reversible (GTR) model of nucleotide substitution, using empirical base frequencies (+F), a proportional of invariable sites (+I), and a discrete Gamma model with default 4 rate categories (G4).

Time-scaled phylogenetic trees based on sampling dates were then generated using 7.0 x 10-4 nucleotide substitutions per site per year, with a standard deviation of 3.5 x 10-4 using Treetime version 0.11.2 as defined in [

15]. We performed molecular clock testing before the final tree building and all outliers that deviated more than three interquartile ranges from the root-to-tip regression were removed

For a phylogenetic representation of the variants, we subsampled each dataset using augur subsampling including a maximum of 500 sequences, and all the sequences from Guinea were retained [

16]. All steps of the analysis were repeated to produce a timescale phylogenetic.

2.3. Analysis of Introduction of VOI and VOC variants in Guinea

The “mugration model” was fitted to each of the time tree topologies in Treetime by mapping the country and division (regions of the country) location of sampled sequences to the external tips of trees. For the division level, we only mapped for Guinea sequences N=1017 (sequences with complete metadata). The “mugration model” treats locations as discrete traits that evolve through the phylogeny [

15]. It allows us to estimate the number of viral transmission events for each VOC between our query sequences and the background sequences. The estimated number was carried out using a Python script developed and implemented by Eduan Wilkinson and collaborators [

5].

All data analytics were performed using a custom bash script and R scripts and, visualization using “ggplot” and “ggmap” libraries in RStudio 4.4.1.

2.4. Mutations Diversity Analysis

For this analysis, we filtered and retrieved from GISAID, all the complete genomes (genomes with more than 29000 nucleotides) and excluded the low coverage (> 95%) corresponding to N=644 sequences from Guinea. Sequences were uploaded into Nextclade to analyze the mutations that were occurring among the different strains [

17]. We then download the output file that contains the summarized results of the analysis, such as clades, mutations, and quality control metrics for statistics analysis. Statistical package dplyr and tidyr in R were used to summarise and group variants by gene and amino acid mutation; we then converted all amino acid mutations below a frequency of 50 to other amino acid mutations.

3. Results

3.1. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Distribution

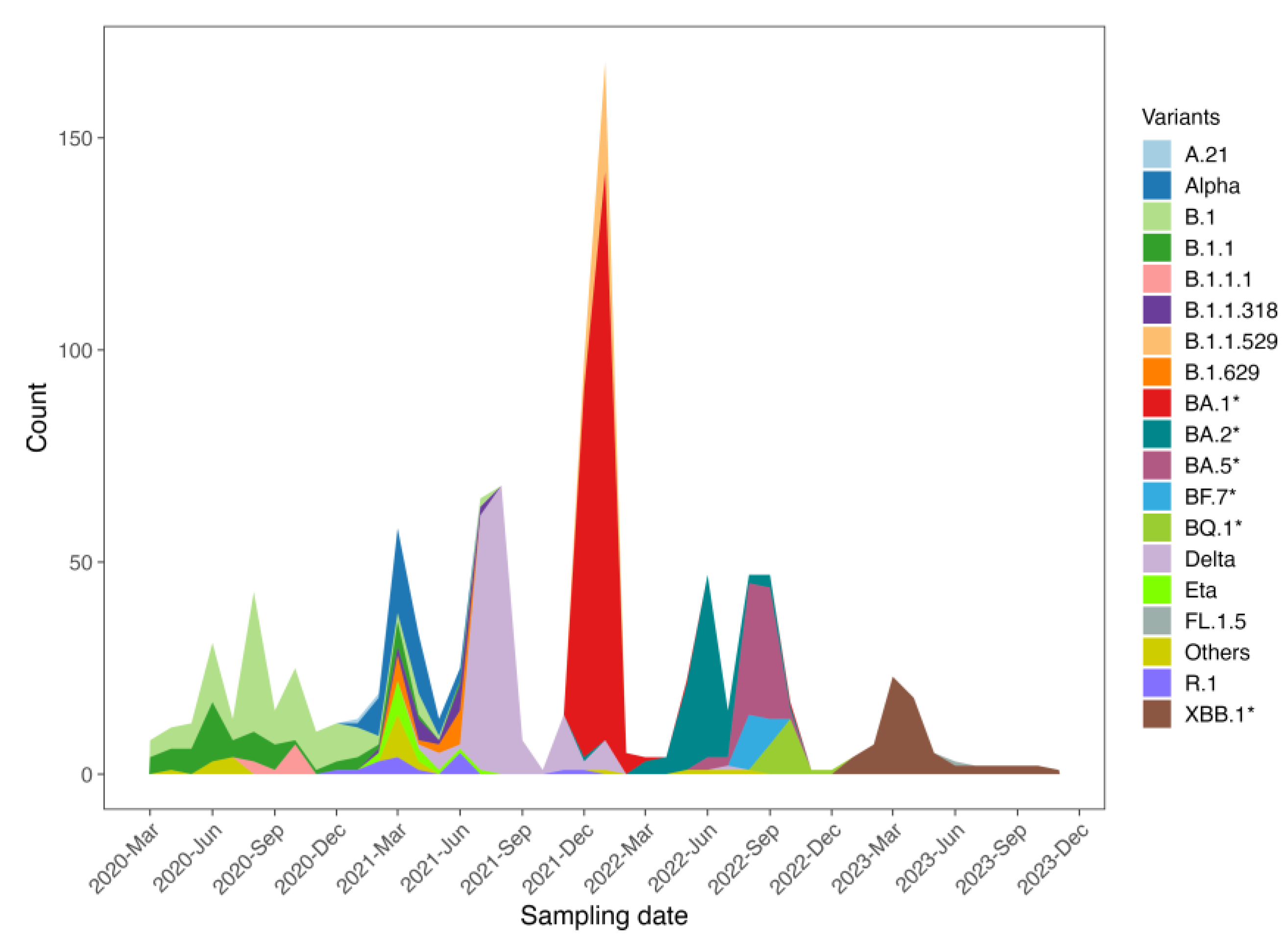

A total of 1038 SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences were shared on the GISAID database from Guinea. According to the WHO classification based on their importance, 72% of these sequences correspond to variants of concern (VOCs), and 28% were variants of interest (VOIs), variants under surveillance (VUM), and others. Across all SARS-CoV-2 genomes, the Omicron variant and its sub-lineages were mostly represented (69.4%), followed by Delta (B.1.617.2) 21,9%, Alpha (B.1.1.7) 6,6% and Eta (B.1.525) 2,1%.

Different waves of the virus circulation were noted in Guinea, reflecting a temporal evolution characterized by distinct periods of variant predominance. The initial waves were associated with the first cases and the circulation of the ancestral B.1 and B.1.1 lineages, observed from the start of the epidemic in March 2020 until early 2021. During the first half of 2021, co-circulation of multiple lineages was noted, with the Alpha variant being the most predominant. The third wave was marked by the dominance of the Delta variant, which prevailed until the end of 2021. In December 2021, the first cases of the Omicron variant were detected, initiating a new wave dominated by the BA.1 sub-lineage. From March 2022 to the end of 2023, successive waves of Omicron sub-lineages, including BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1, and XBB.1, were observed. These sub-lineages led to smaller epidemic waves, reflecting a complex evolutionary and epidemiological dynamic (

Figure 1).

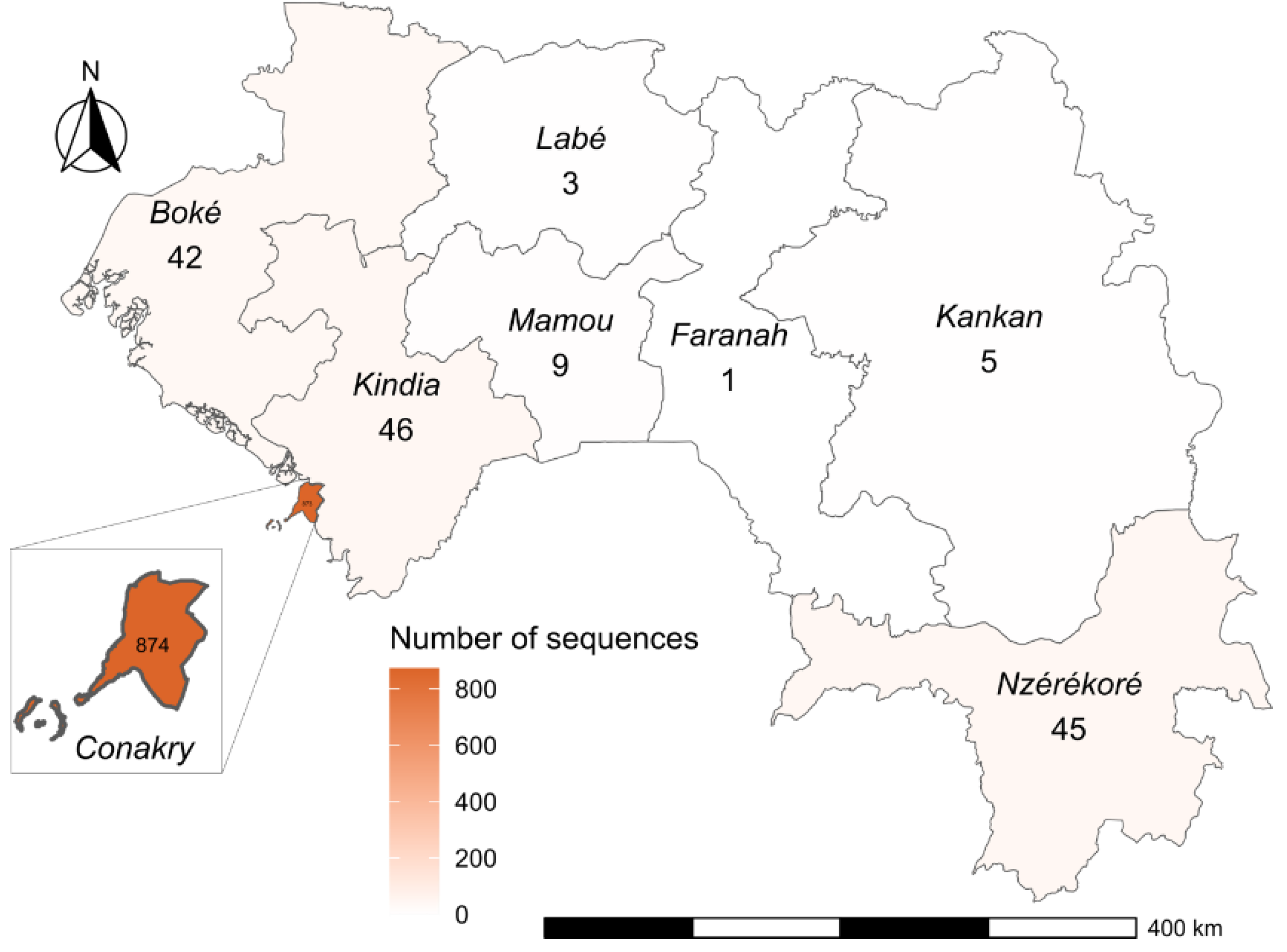

Geographically, Guinea is subdivided into 8 administrative regions. Of the total sequences generated, 84% (874/1038) were generated from isolates collected in Conakry, the capital city of the country with the presence of many of the administrative departments and the international airport. For our study period, genomic surveillance also covered the prefectures of Kindia 4,4% (46/1038), Nzérékoré 4,3% (45/1038), Boké 3,9% (42/1038), Mamou 0,9% (9/1038), Kankan 0,5% (5/1038) and Labé 0,3% (3/1038) (

Figure 2).

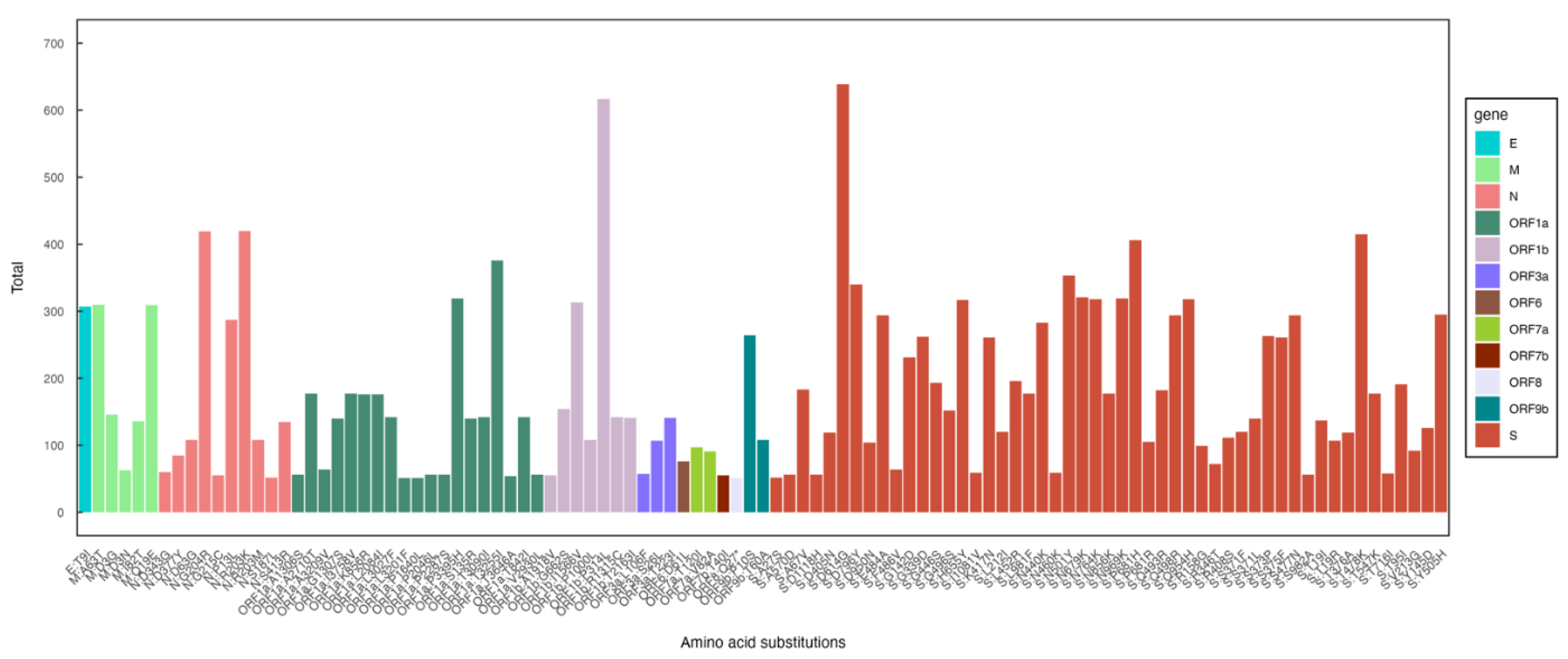

3.2. Mutational Analysis

Our analysis showed that, as observed by others, most mutations were localized in the spike protein (S) region, followed by ORF1a and nucleocapsid (N). The most common mutations were D614G, P314L, P681H, T478K, and N501Y (

Figure 3).

3.3. Origins of Variants of Concern Circulating in Guinea

We carried out a phylogeographic analysis on all the variants of concern (VOCs) that have circulated in Guinea to predict the probable origin of the different variants and the dates of introduction of these strains in the country. The variants analyzed were Alpha (B.1.1.7), Delta (B.1.617.2), Eta (B.1.525), and Omicron (BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1, and XBB) and sublineages. The datasets curated are, for Alpha (2 975 genomes including 50 from Guinea), Delta (3 729 genomes including 108 from Guinea), Eta (3 502 genomes including 26 from Guinea), BA.1, and sublineages (2 303 genomes including 173 from Guinea), BA.2 and sublineages (2 934 genomes including 32 from Guinea), BA.5 (1750 genomes including 44 from Guinea), BQ.1 and sublineages (1 729 genomes including 108 from Guinea) and XBB.1 and sublineages (2 404 genomes including 106 from Guinea).

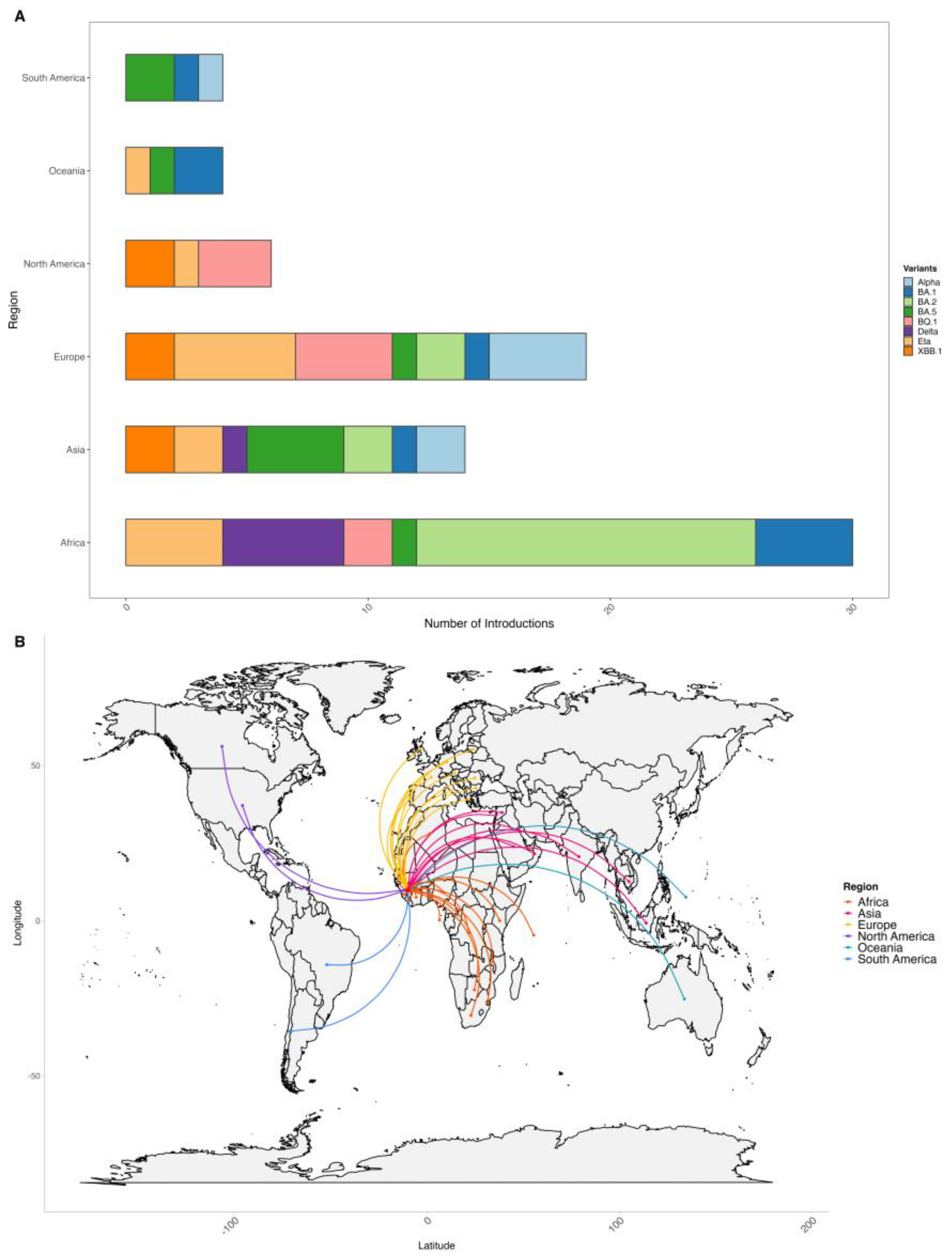

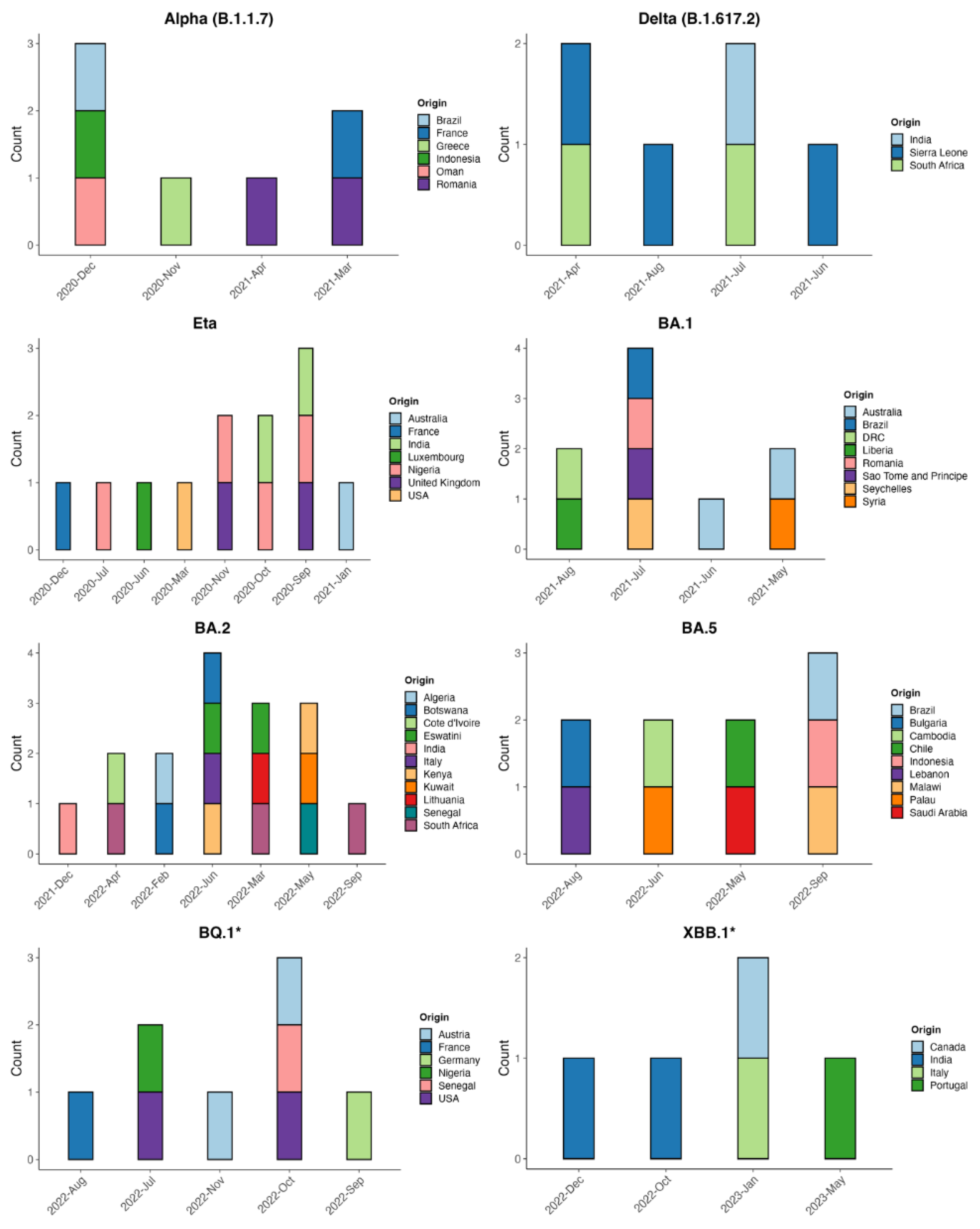

We inferred a total of 75 introductions of SARS-CoV-2 variants into Guinea, with the majority originating from African and European countries, accounting for 40% and 25,3%, followed by introductions from Asia at 18,6% (

Figure 4).

For the Alpha variant that emerged in the United Kingdom, we identified seven introductions into Guinea between November 2020 and April 2021; the first importation was from Greece in Europe, followed by Indonesia from Asia. For the Delta variant, 6 introductions were inferred between April 2021 and August 2021, including 5 introductions from an African country, including three (03) from Sierra Leone, which borders Guinea. For Eta lineage, 12 introduction events were inferred between March 2020 and January 2021; the majority 4/12 were from Nigeria; the first introduction was from the USA. Regarding the Omicron variant with its sub-lineages BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1* XBB.1.5*, we have inferred a cumulative of 47 introductions in Guinea; the majority were for BA.2, 16/47 (between December 2021 and September 2022) originating from India, Côte d’Ivoire, Algeria, Botswana and others country; followed by BA.1 (between May 2021 and August 2021) with first introductions from Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo and BA.5 (between May 2022 and September 2022) both accounted for 9/47. Variants BQ.1 8/47 were imported between November 2021 and January 2022 from France, Nigeria, USA, Austria, Senegal, Germany, and XBB.1 between October 2022 and May 2023 from India, Canada, Italy and Portugal (

Figure 5).

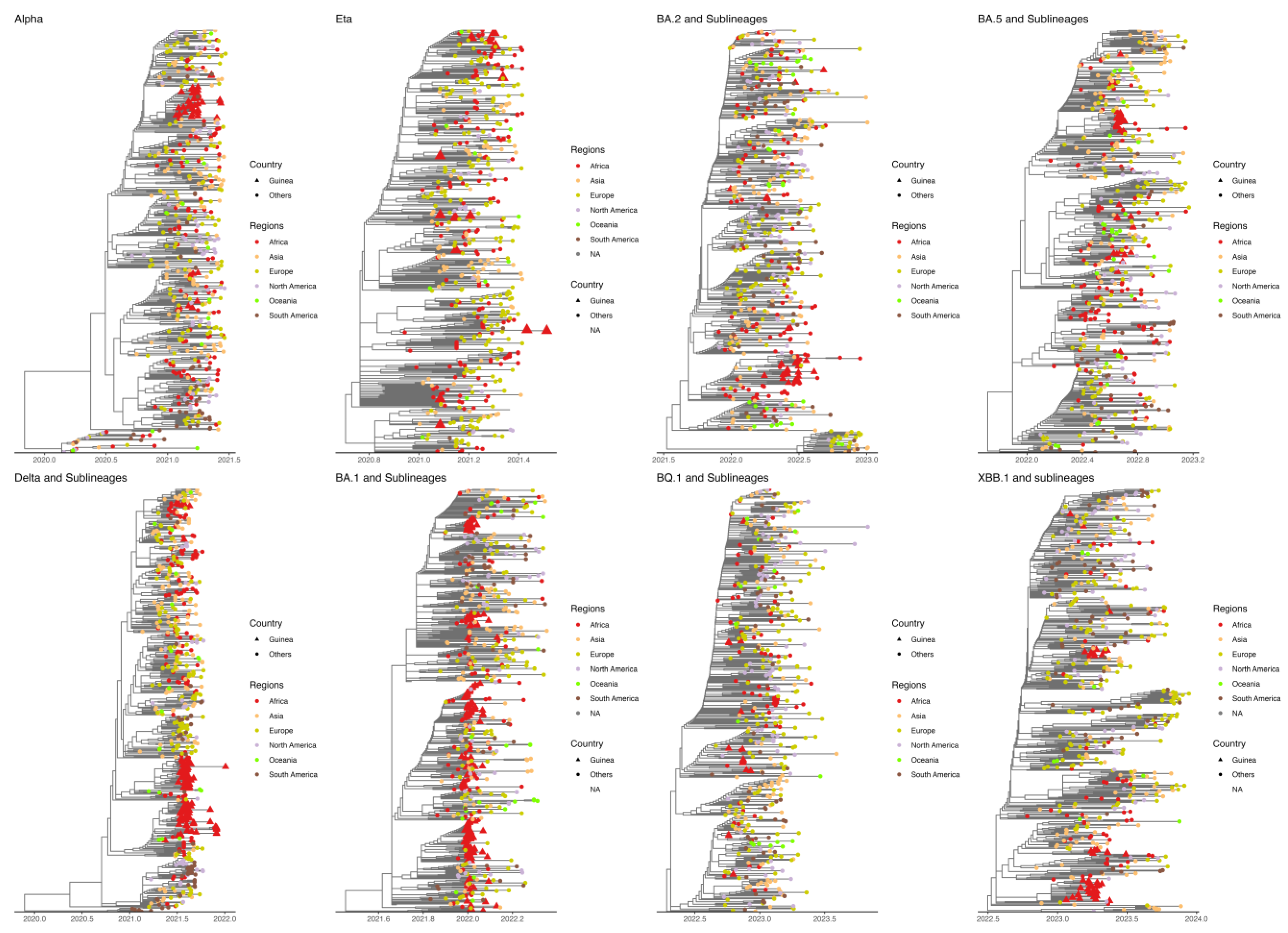

Our phylogenetic analysis revealed two distinct patterns for the different variants. We identified dense clusters as well as some scattered sequences for the Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants (BA.1, BA.5, and XBB.1) and their sub-lineages. In contrast, for the Eta variant and Omicron sub-lineages BA.2 and BQ.1, we observed a significant dispersion of sequences throughout the phylogenetic trees. These results support the hypothesis that, in the first case, a single introduction facilitated the rapid local spread of these variants, with a few additional distinct introductions. The second case suggests multiple introductions, possibly accompanied by rapid viral evolution (

Figure 6).

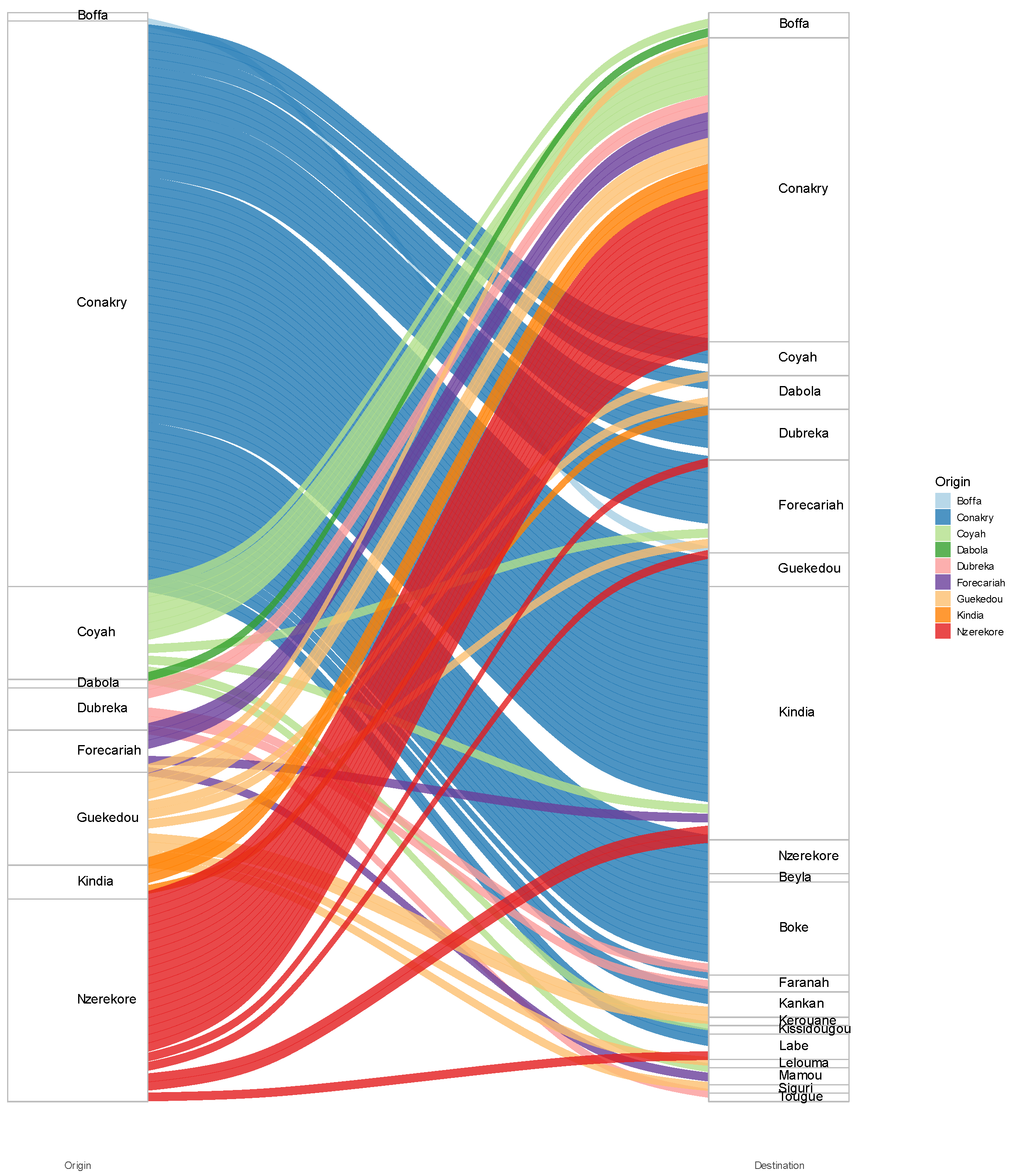

The majority of inter-regional introductions within Guinea originated from Conakry, accounting for 67 out of 129 cases (51,9%), followed by Nzérékoré with 24 cases (18,6%), and Coyah and Gueckedou, each contributing 11 cases (8,5%). The first introduction of SARS-CoV-2 was inferred to have reached Conakry from an unidentified source. Subsequent migration movements were observed from Conakry to Coyah (and vice-versa), as well as from Conakry to Gueckedou, Dubreka, and Boffa. Cases were also exported from Nzérékoré to other regions of the country, including Conakry, Kindia, Gueckedou, Forékaria, and Labé (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Guinea, like all other countries, experienced multiple waves of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The first confirmed case in Guinea, detected in March 2020 via PCR test from a European traveler’s sample, prompted health authorities to swiftly implement preventive measures to curb the spread of the virus. Laboratories across the country were equipped with molecular diagnostic tools to enhance the detection of suspected cases. In the initial stages of the pandemic, Guinea lacked local sequencing capacity, which limited its ability to monitor the genetic evolution of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. As a result, the first viral genomes were sequenced abroad in collaboration with partner laboratories. This international cooperation allowed for the initial characterization of the strains circulating in the country.

A year after the pandemic began, Guinea successfully developed its local sequencing capacities, due to the establishment of genomic surveillance networks, including the Afroscreen network, a French response program against COVID-19 to strengthen monitoring of the evolution of variants in 13 African countries [

18]. This marked a significant advance in the country's ability to monitor and respond to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. The implementation of local sequencing has enabled a more comprehensive understanding of the viral strains present within the country, contributing to global efforts to track the spatio-temporal evolution of SARS-CoV-2.

In this study, we investigated the genetic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating in Guinea by analysing viral sequences shared in public databases. Between March 2020 and December 2023, Guinea experienced four major epidemic waves, each marked by the circulation of distinct strains or variants.

The first strains identified in March 2020 belonged to the B.1 and B.1.1 lineages, which were classified under Clades 20A and 20B, according to the Nextstrain classification. These early strains evolved into various sub-lineages, which persisted from 2020 through the first quarter of 2021. In January 2021, Guinea recorded its first cases of Variants of Concern (VOCs), including B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.525 (Eta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta), all falling within Clade 20I. These VOCs were first detected in Guinea between January and May 2021, contributing to the second and third waves of the pandemic in the country [

12,

19].

In December 2021, the Omicron variant (BA.1, Clade 21K) was identified in Guinea, marking the beginning of the final major wave of the epidemic. The Omicron variant, along with its rapidly evolving sub-lineages, became the dominant strain and persisted throughout the remainder of the pandemic, up until December 2023, as reflected in sequences shared in public databases.

The majority of SARS-CoV-2 genomes were derived from positive samples collected in Conakry, the capital city of Guinea. The presence of the country’s largest international airport in Conakry implies significant international and subregional air traffic, which contributed to the early and continuous introduction of new variants. The limited representation of genomic data from other prefectures is in part due to the lack of sequencing capacity in laboratories outside of Conakry. Also, at the beginning of the pandemic, epidemiological surveillance and diagnostic laboratory capacities were established in the capital, leaving other regions underrepresented to participate in genomic surveillance efforts. This centralization of resources further explains why most sequences originated from Conakry, limiting our understanding of the spread and diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in other areas of the country.

In our analysis, we identified the key mutations present in SARS-CoV-2 genomes from Guinea, focusing on those primarily associated with the diversity of circulating variants. The most frequently observed mutation was D614G, which has been extensively reported in numerous studies as the dominant mutation throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, appearing in most SARS-CoV-2 lineages [

20]. This mutation, first identified early in the pandemic, is known to enhance viral replication in human lung epithelial cells and primary respiratory tissues by increasing virion infectivity and stability [

21,

22].

The second most frequent mutation observed was P681H, one of the eight mutations identified in the spike protein of the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7), which emerged at the end of 2020. This mutation is believed to improve Furin cleavage, thereby facilitating viral entry into host cells [

23]. Additionally, the N501Y mutation, which was also detected in our data, is associated with increased transmissibility of the Alpha variant [

24].

Another notable mutation, T478K, was identified with high frequency and is characteristic of the Delta variant (B.1.617.2). This mutation has been described as unique to Delta in early sequence analyses, contributing to its enhanced spread and impact during the pandemic [

25].

SARS-CoV-2 variants were introduced into Guinea through international and subregional transmission, with individuals traveling from infected countries importing new strains. In addition to these imported cases, there was significant local spread of the virus. A migration analysis revealed that most introductions came from African countries, followed by Europe and Asia.

Similarly, in the neighboring country Côte d’Ivoire, research indicated that many introductions originated from other subregional countries, highlighting the impact of regional transmission [

26]. Our analysis indicates that 25,3% of cases in Guinea were introduced from Europe. Wilkinson et al., in their study, observed that 64% of detectable viral introductions in Africa originated from Europe, underscoring the strong epidemiological connection between Europe and Africa [

5].

Within Africa, the most notable introductions were the Eta variant from Nigeria and Delta variant from Sierra Leone, a neighboring country. For the Alpha and Delta variants, local transmission was significant, likely influenced by the closure of borders and the suspension of international flights. Additionally, containment measures implemented during this period may have further contributed to limiting international introductions while amplifying local spread.

A significant migratory flow has been observed in local Guinea, demonstrating that despite the health measures put in place to limit the circulation of the virus in Conakry, it has not prevented its export to other regions of the country. In addition, a significant number of exports from the Nzérékoré region to other regions, including Conakry. This could be explained by the potential introduction to Nzérékoré from countries bordering the region. The region borders three countries: Cote d'Ivoire, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

To our knowledge, this study is the first in Guinea to explore the diversity and evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern within the country. While it successfully highlights the similarities, origins of strains circulating in Guinea, and the migratory flow between different regions, it also has certain limitations. Specifically, the reference sequences selected may not fully represent the West African sub-region or other areas due to the disproportionately higher number of sequences generated by developed countries with more extensive sequencing resources. This limitation may restrict the scope of our conclusions regarding the regional and international dynamics of virus spread.

5. Conclusions

This analysis of a large dataset of SARS-CoV-2 sequences, including high-quality genomes produced in Guinea during the COVID-19 pandemic, has provided valuable insights into the distribution of variants and mutations circulating in the country. The genetic diversity observed in Guinea closely mirrors patterns seen in many other countries worldwide. Our findings revealed multiple introductions of Variants of Concern (VOCs) into Guinea, directly associated with the various epidemic peaks observed, underscoring the significant impact of intercontinental travel on the spread of the virus.

As the importation analysis has some limitations due to the low representation of sequences from certain African countries, particularly from the West African sub-region, this underscores the need to strengthen genomic surveillance and ensure that it covers samples from across the country and for future epidemics. Expanding surveillance efforts will increase the detection of viral mutations and improve the overall understanding of outbreaks, highlighting the critical role of sequencing in epidemic control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.C.G, K.J.J.O.K, M.J.M, H.D, A.K.S, A.K.K, C.G.H, N.F, N.V, E.G, A.A, E.D, M.P, A.T and AKK; Supervision, MJM, M.P, A.T, and A.K.K; Visualization, T.A.C.G; Writing – original draft, T.A.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Agence Française de Développement through the AFROSCREEN project (grant agreement CZZ3209), coordinated by ANRS | Maladies infectieuses émergentes in partnership with Institut Pasteur and IRD.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Nextstrain project, the GISAID database, and all labs that contributed SARS-CoV-2 sequence data; We would additionally like to thank members from the AFROSCREEN Consortium (

https://www.afroscreen.org/en/network/) for their work and support on genomic surveillance in Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Flores-Vega VR, Monroy-Molina JV, Jiménez-Hernández LE, Torres AG, Santos-Preciado JI, Rosales-Reyes R. SARS-CoV-2: Evolution and Emergence of New Viral Variants. Viruses 2022, 14, 653. [CrossRef]

- Si Y, Wu W, Xue X, Sun X, Qin Y, Li Y, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15990. [CrossRef]

- Colson P, Fournier P-E, Chaudet H, Delerce J, Giraud-Gatineau A, Houhamdi L, et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants From 24,181 Patients Exemplifies the Role of Globalization and Zoonosis in Pandemics. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 786233. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants n.d. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed , 2024). 16 September.

- Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, Tegally H, San JE, Lessells R, Cuadros D, et al. A year of genomic surveillance reveals how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic unfolded in Africa. Science 2021, 374, 423–431. [CrossRef]

- Rahman S, Hossain MJ, Nahar Z, Shahriar M, Bhuiyan MA, Islam MR. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Subvariants: Challenges and Opportunities in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic. Environ Health Insights 2022, 16, 11786302221129396. [CrossRef]

- Lauring AS, Frydman J, Andino R. The role of mutational robustness in RNA virus evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013, 11, 327–336. [CrossRef]

- Manjunath R, Gaonkar SL, Saleh EAM, Husain K. A comprehensive review on Covid-19 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 103372. [CrossRef]

- Farahat RA, Baklola M, Umar TP. Omicron B.1.1.529 subvariant: Brief evidence and future prospects. Ann Med Surg 2012 2022, 83, 104808. [CrossRef]

- Farahat RA, Abdelaal A, Umar TP, El-Sakka AA, Benmelouka AY, Albakri K, et al. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants: current situation and future trends. Infez Med 2022, 30, 480–494. [CrossRef]

- Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, Tegally H, Scheepers C, Althaus CL, et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 2022, 603, 679–686. [CrossRef]

- Grayo S, Troupin C, Diagne MM, Sagno H, Ellis I, Doukouré B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Circulation, Guinea, March 2020–July 2021. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 457–460. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [CrossRef]

- Sagulenko P, Puller V, Neher RA. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol 2018, 4, vex042. [CrossRef]

- Huddleston J, Hadfield J, Sibley TR, Lee J, Fay K, Ilcisin M, et al. Augur: a bioinformatics toolkit for phylogenetic analyses of human pathogens. J Open Source Softw 2021, 6, 2906. [CrossRef]

- Aksamentov I, Roemer C, Hodcroft EB, Neher RA. Nextclade: clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. J Open Source Softw 2021, 6, 3773. [CrossRef]

- AFROSCREEN : Renforcement des capacités de séquençage en Afrique n.d. https://www.afroscreen.org/ (accessed , 2024). 26 September.

- Sow MS, Togo J, Simons LM, Diallo ST, Magassouba ML, Keita MB, et al. Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 in Guinea, West Africa. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0299082. [CrossRef]

- Yurkovetskiy L, Wang X, Pascal KE, Tomkins-Tinch C, Nyalile TP, Wang Y, et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Variant. Cell 2020, 183, 739–751.e8. [CrossRef]

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell 2020, 182, 812–827.e19. [CrossRef]

- Plante JA, Liu Y, Liu J, Xia H, Johnson BA, Lokugamage KG, et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature 2021, 592, 116–121. [CrossRef]

- Lubinski B, Fernandes MHV, Frazier L, Tang T, Daniel S, Diel DG, et al. Functional evaluation of the P681H mutation on the proteolytic activation the SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 (Alpha) spike. bioRxiv 2021, 2021.04.06.438731. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liu J, Plante KS, Plante JA, Xie X, Zhang X, et al. The N501Y spike substitution enhances SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nature 2022, 602, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature 2021, 596, 276–280. [CrossRef]

- Anoh EA, Wayoro O, Monemo P, Belarbi E, Sachse A, Wilkinson E, et al. Subregional origins of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants during the second pandemic wave in Côte d’Ivoire. Virus Genes 2023, 59, 370–376. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Trends in prevalence of major variants circulating in Guinea from March 2020 to December 2024. The Y-axis shows the distribution (n = 1 038) of various variants including VOCs across the various months (X-axis) while the lineages are represented by different colors.

Figure 1.

Trends in prevalence of major variants circulating in Guinea from March 2020 to December 2024. The Y-axis shows the distribution (n = 1 038) of various variants including VOCs across the various months (X-axis) while the lineages are represented by different colors.

Figure 2.

Map showing the sampled regions (n = 1 038) and the color scheme showing the number of sequences generated from samples collected in each region.

Figure 2.

Map showing the sampled regions (n = 1 038) and the color scheme showing the number of sequences generated from samples collected in each region.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of amino acid substitutions across all the SARS-CoV-2 proteins in all high-quality genomes that were submitted to GISAID for Guinea (N=644/1038). The mutations are sorted and colored per gene.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of amino acid substitutions across all the SARS-CoV-2 proteins in all high-quality genomes that were submitted to GISAID for Guinea (N=644/1038). The mutations are sorted and colored per gene.

Figure 4.

(A) Number of importation events by world regions of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1, XBB.1} and sublineages) into Guinea from March 2020 to December 2023. (B) Geographical distribution of the importations.

Figure 4.

(A) Number of importation events by world regions of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1, XBB.1} and sublineages) into Guinea from March 2020 to December 2023. (B) Geographical distribution of the importations.

Figure 5.

Number and origin of importation events of the different SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1 and XBB.1.5} and sublineages) into Guinea between March 2020 and December 2023.

Figure 5.

Number and origin of importation events of the different SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1 and XBB.1.5} and sublineages) into Guinea between March 2020 and December 2023.

Figure 6.

Timescale phylogeny of SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1 and XBB.1.5} and sublineages). 500 sequences were subsampled from a global dataset to maximize genetic distances while retaining all genomes from Guinea. The branches are scaled in decimal time, and sampling dates are capped on each lineage’s last sampling date, the latest sampling month in Guinea in this study.

Figure 6.

Timescale phylogeny of SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Alpha, Eta, Delta, Omicron {BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1 and XBB.1.5} and sublineages). 500 sequences were subsampled from a global dataset to maximize genetic distances while retaining all genomes from Guinea. The branches are scaled in decimal time, and sampling dates are capped on each lineage’s last sampling date, the latest sampling month in Guinea in this study.

Figure 7.

Number of SARS-CoV-2 imports and exports into and out of various regions in Guinea.

Figure 7.

Number of SARS-CoV-2 imports and exports into and out of various regions in Guinea.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).