1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Normal wound healing is a complex and well-organized process which involves cell migration, cell proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition. However, chronic illnesses such as diabetes can lead to the dysregulation of cellular and molecular signals during this process [

1].

Skin and soft tissue infections are common chronic complications of diabetes and may represent a risk factor for lower limb amputation in diabetic patients [

2]. Foot infections are particularly prevalent among individuals with diabetes, ranging from superficial paronychia to deep infections involving the bones [

3]. Staphylococcus aureus and beta-haemolytic streptococci are the most prevalent pathogens in mild to moderate infections that are left untreated, while severe and persistent infections are often polymicrobial [

2].

A plantar diabetic foot abscess can be caused by various factors, such as neglecting nail hygiene, trauma and mal perforans, among others. It manifests as a tender mass, with symptoms including swelling, warmth, redness, and pain [

4].

The treatment requires multiple surgical debridements of the infected tissue. In some cases, this approach may involve amputation of the segment at various levels. The debridement of necrotic or infected tissue must be performed with maximum preservation of healthy surrounding structures

[5]. Following the resolution of the infectious process, patients are often left with complex soft tissue defects. Reconstructive surgery is challenging in these patients due to the delayed wound healing. In addition to classic surgical methods, new therapeutic options to stimulate wound healing are being studied [

6].

The use of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is thought to be beneficial for these patients. PRP injection is a common procedure in aesthetic and plastic surgery. The product is easily obtainable and its injection is minimally invasive. Platelets secrete several growth factors that interact with the local environment to promote cell differentiation and proliferation, resulting in re-epithelization and angiogenesis

[7].

This paper presents a case report on this potential regenerative treatment in the diabetic foot.

2. Case Presentation

58 years old male patient presented with pain and swelling of the left foot, associated with fever and elevated inflammatory markers. At admission, surgical debridement with minimally invasive incisions was performed. Empiric antibiotic therapy was initiated, without microbial cultures.

After 2 days of hospitalization, the patient was referred to the plastic surgery department. The patient underwent a more aggressive second surgical debridement, which revealed a deep midfoot plantar abscess affecting the first, second and third intermetatarsal spaces. The result was a 10 x 5 cm dorsal defect and a 3 x 3 cm plantar wound with a communicating cavity. Wound culture specimen was obtained. Negative pressure wound therapy was initiated and maintained for 5 days.

Figure 1.

Wound appearance (dorsal view) after 5 days postoperative.

Figure 1.

Wound appearance (dorsal view) after 5 days postoperative.

During the hospitalisation, the general status of the patient started deteriorating, with poor peripheral blood oxygenation and episodes of high blood pressure.

Patient accused orthopnoea and fatigability

Respiratory and cardiological evaluations were performed, which established a presumptive diagnosis of acute respiratory failure due to either pneumonia or cardiac failure. Chest X-ray and CT scans were performed. During the first CT scan, the patient suffered a respiratory arrest and was therefore mechanically ventilated and admitted in the ICU.

For 14 days, the patient received intensive medical care, together with wound management through local dressings.

The lesion had a favorable evolution under systemic therapy (antibiotics, analgesics and parenteral nutrition) and local daily irrigation with antiseptic solutions and wet to dry dressings.

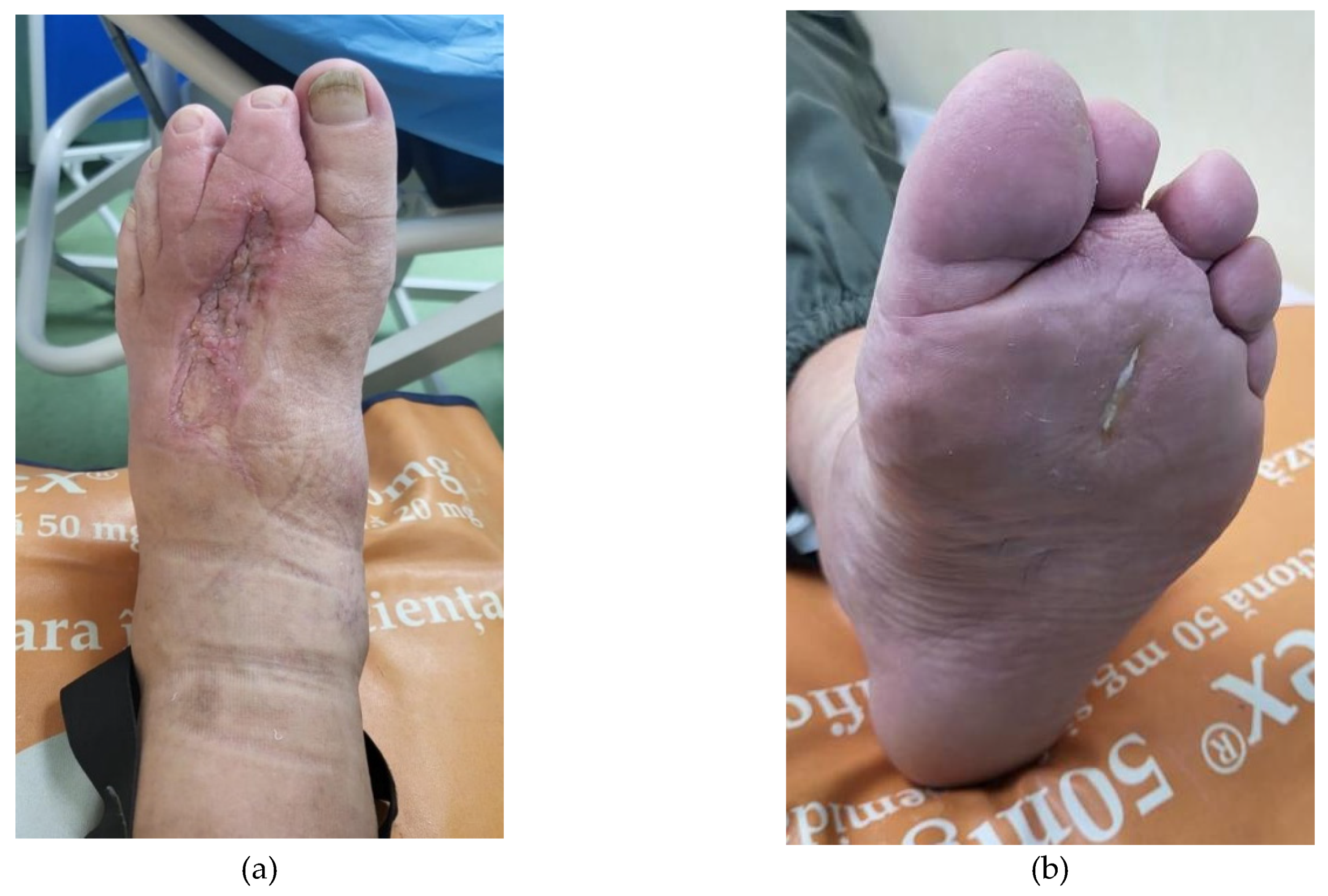

Figure 2.

Appearance of the wound (a.dorsal and b.plantar aspect) after 25 days postoperative.

Figure 2.

Appearance of the wound (a.dorsal and b.plantar aspect) after 25 days postoperative.

When the status of the patient was stable, we proceeded to cover the dorsal foot defect with a split thickness skin graft.

Figure 3.

Clinical appearance after skin grafting.

Figure 3.

Clinical appearance after skin grafting.

At 2 days after skin grafting (4 weeks from the hospitalization), 20 ml of venous blood was collected in special vacutainers. PRP was obtained after centrifugation of the specimen at 3500 rot/min for 10 min. 10 ml of the product was injected into the plantar wound and around and under the skin graft.

Postoperatively, we performed classic dressings of the wound (paraffine impregnated gauze).

Complete postoperative healing was achieved at 30 days.

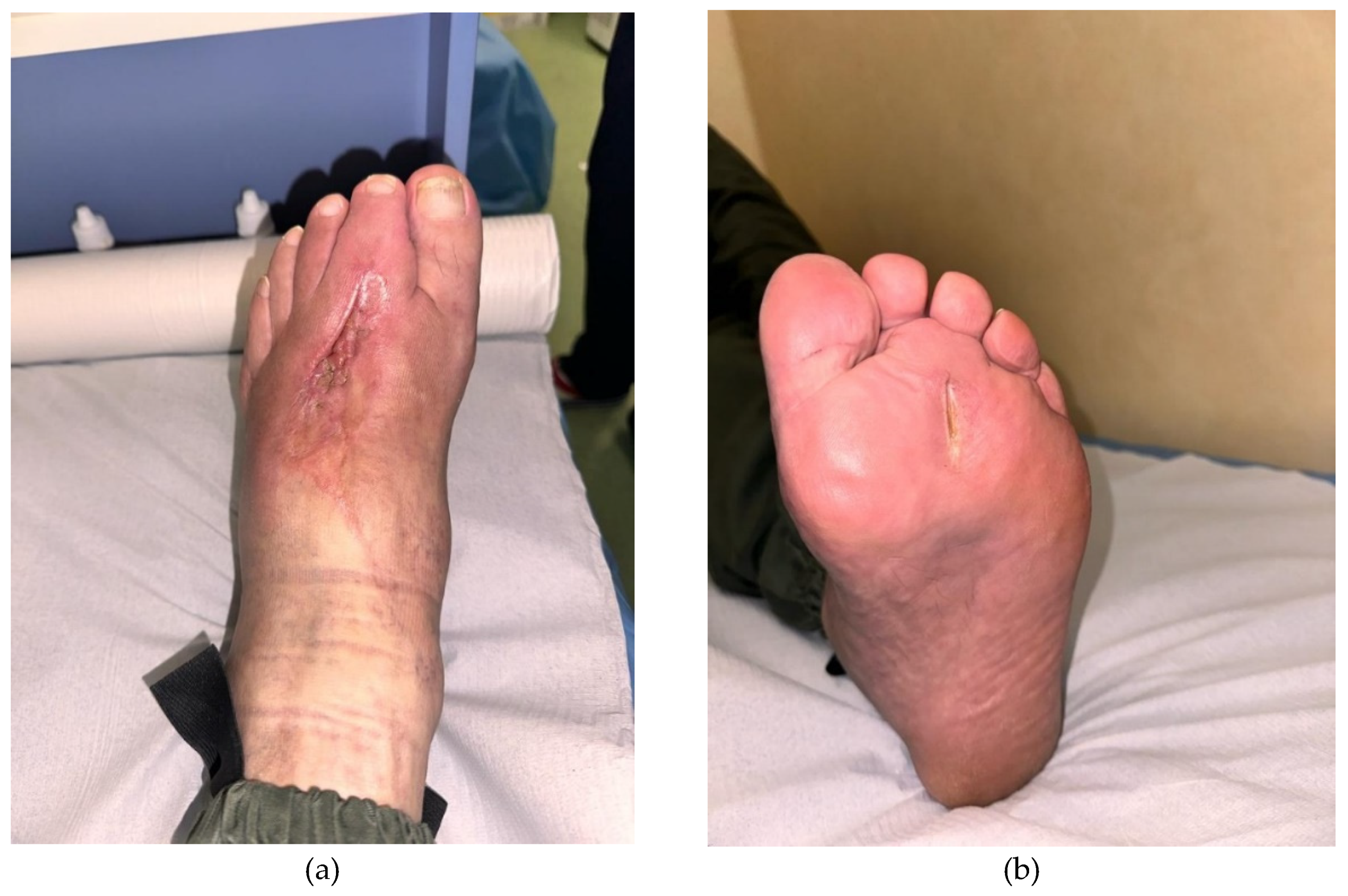

Figure 4.

Local apperance (a.dorsal and b.plantar view) 30 days after the first session of PRP (we performed another session of PRP).

Figure 4.

Local apperance (a.dorsal and b.plantar view) 30 days after the first session of PRP (we performed another session of PRP).

Figure 5.

Aspect ( a.dorsal and b.plantar view) after 2 weeks from the second session of PRP.

Figure 5.

Aspect ( a.dorsal and b.plantar view) after 2 weeks from the second session of PRP.

3. Discussion

There is ongoing research on the potential therapeutic effects of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in the management of diabetic foot complications

[7]. It's crucial to consider that not all studies demonstrate unequivocal benefits, and the optimal protocols for PRP application (concentration, frequency, application method) are still subjected to debate

[8]. While some studies suggest positive outcomes and accelerated wound healing with PRP

[7], results have been controversial

[9]. The effectiveness of PRP may depend on various factors, including the patient's particular status and history, the type of wound, and the PRP preparation method

[7].

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is a concentrated platelet product obtained from the patient's own blood. Platelets contain various growth factors and cytokines that play a crucial role in tissue repair and regeneration [

8]. The concept behind using PRP for the treatment of the diabetic foot is to use these regenerative properties to improve wound healing and reduce complications associated with diabetes [

10].

Diabetes can lead to poor peripheral blood flow and impaired wound healing. PRP may be applied topically or injected into the wound to stimulate tissue regeneration and accelerate the healing process. PRP has been studied for its potential to promote angiogenesis – the formation of new blood vessels –, which could improve blood supply to the affected areas [

11].

Chronic inflammation is another common issue in diabetic patients. PRP contains anti-inflammatory cytokines that may help modulate the inflammatory response and create a more favorable environment for healing. PRP has also been explored for its potential to reduce pain associated with diabetic neuropathy, a common complication of diabetes affecting the nerves

[12].

It's important to mention that, while there is some promising evidence supporting the use of PRP in diabetic foot care, the research is still in its early stages, and more large-scale, well-controlled clinical trials are needed to clearly establish its efficacy and safety.

4. Conclusions

Overall, the case report and discussion contribute to the understanding of regenerative treatments in diabetic foot care.

PRP can be easily injected around wound edges or applied as a dressing, making it a relatively non-invasive adjunct to surgery. This minimizes trauma to already vulnerable tissues and provides localized healing benefits without additional extensive surgical procedures. In limb-sparing surgeries, this can contribute to better mobility and overall limb function post-recovery, enhancing the quality of life for patients.

We acknowledge that more large-scale, well-controlled clinical trials are needed to establish the efficacy and safety of PRP conclusively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, S.-M.R.; supervision, R.-D.S.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Baron JM, Glatz M, Proksch E. Optimal Support of Wound Healing: New Insights. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):593-600. Epub 2020 Jan 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA. 2023 Jul 3;330(1):62-75. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lipsky BA, Senneville É, Abbas ZG, Aragón-Sánchez J, Diggle M, Embil JM, Kono S, Lavery LA, Malone M, van Asten SA, Urbančič-Rovan V, Peters EJG; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF). Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of foot infection in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020 Mar;36 Suppl 1:e3280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters EJ, Lipsky BA. Diagnosis and management of infection in the diabetic foot. Med Clin North Am. 2013; 97: 911-946.

- Tardivo JP, Serrano R, Zimmermann LM, et al. Is surgical debridement necessary in the diabetic foot treated with photodynamic therapy? Diabet Foot Ankle. 2017; 8:1373552.Chu Y, Wang C, Zhang J, et al. Can we stop antibiotic therapy when signs and symptoms have resolved in diabetic foot infection patients? Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015; 14: 277-283.

- Li X, Wen S, Dong M, Yuan Y, Gong M, Wang C, Yuan X, Jin J, Zhou M, Zhou L. The Metabolic Characteristics of Patients at the Risk for Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Comparative Study of Diabetic Patients with and without Diabetic Foot. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023 Oct 17;16:3197-3211. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meznerics FA, Fehérvári P, Dembrovszky F, Kovács KD, Kemény LV, Csupor D, Hegyi P, Bánvölgyi A. Platelet-Rich Plasma in Chronic Wound Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J Clin Med. 2022 Dec 19;11(24):7532. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abd El-Mabood E.A., Ali H.E. Platelet-rich plasma versus conventional dressing: Does this really affect diabetic foot wound-healing outcomes? Egypt. J. Surg. 2018;37:16–26. [CrossRef]

- Qu W., Wang Z., Hunt C., Morrow A.S., Urtecho M., Amin M., Shah S., Hasan B., Abd-Rabu R., Ashmore Z., et al. The effectiveness and safety of platelet-rich plasma for chronic wounds: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021;96:2407–2417. [CrossRef]

- Anitua E., Aguirre J.J., Algorta J., Ayerdi E., Cabezas A.I., Orive G., Andia I. Effectiveness of autologous preparation rich in growth factors for the treatment of chronic cutaneous ulcers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2008;84:415–421. [CrossRef]

- Yang L., Gao L., Lv Y., Wang J. Autologous platelet-rich gel for lower-extremity ischemic ulcers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017;10:13796–13801.

- Amato B., Farina M.A., Campisi S., Ciliberti M., di Donna V., Florio A., Grasso A., Miranda R., Pompeo F., Farina E., et al. Cgf treatment of leg ulcers: A randomized controlled trial. Open Med. 2020;14:959–967. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).