3. Results and discussion

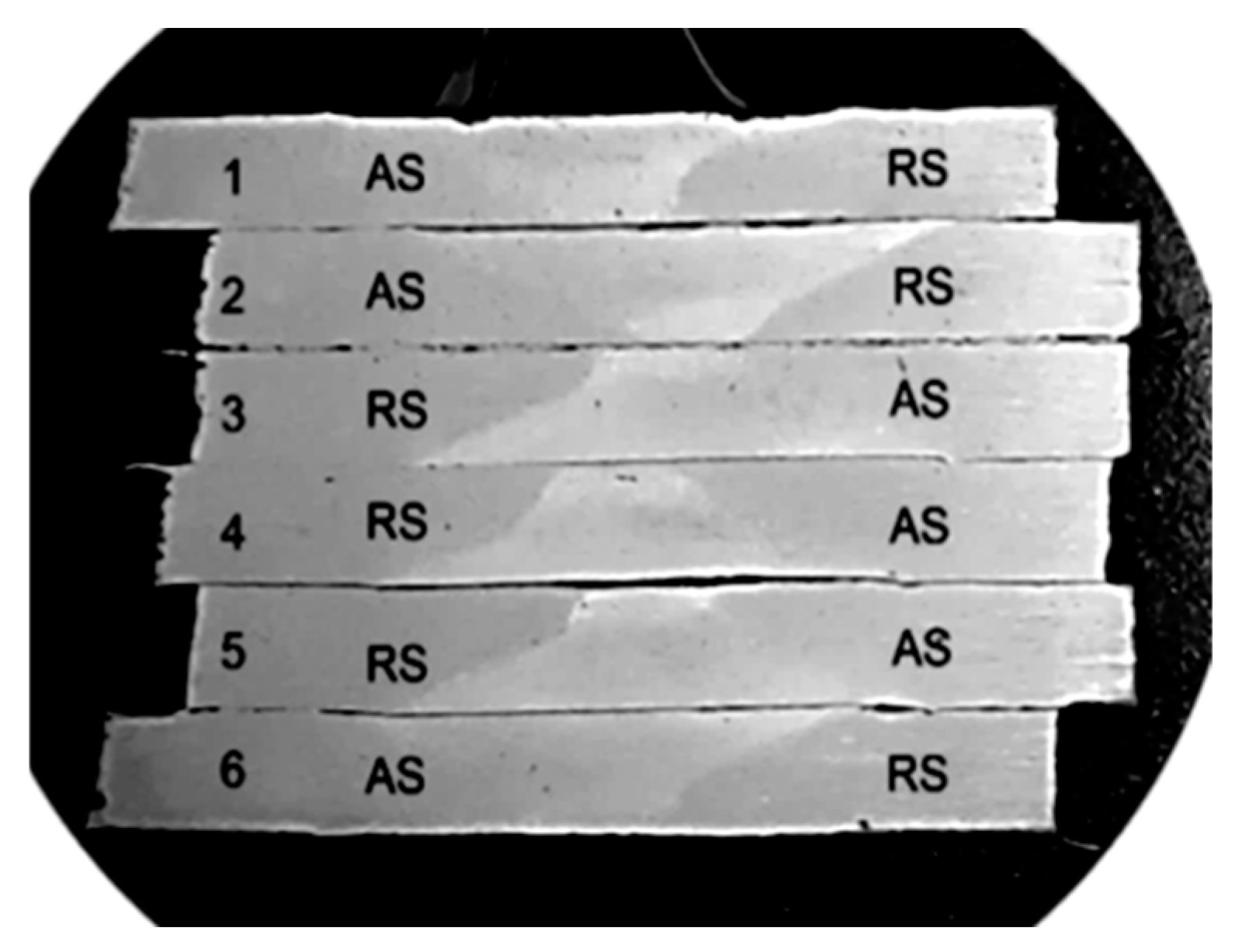

In the optical evaluation of the macrostructure of six samples produced at various linear welding speeds (see

Figure 3), it was observed that all exhibited a characteristic asymmetrical weld profile typical of Friction Stir Welding, featuring advancing (AS) and retreating (RS) sides. Each sample displayed a area marked by significant plastic deformation, free from any cavities. The width of the welds measures approximately 10-15 mm.

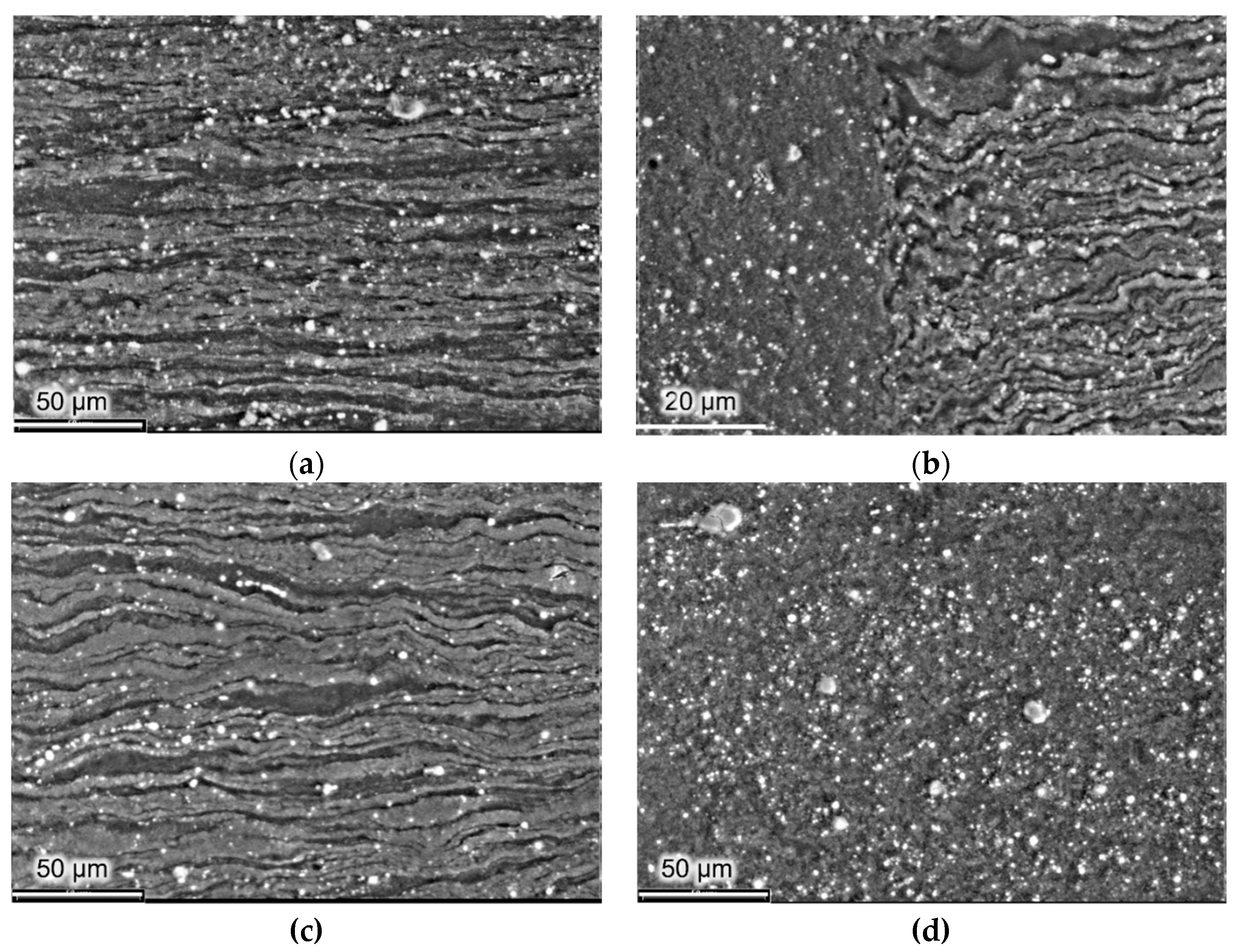

Thermodynamic processes during welding on the retreating side (RS) form a clear boundary between the thermo-mechanical affected zone (TMAZ) that contains the core of the weld (

Figure 4a) and the base metal. The primary magnesium alloy within the Mg-Al-Zn system exhibits a rolled structure characterized by elongated grains (refer to

Figure 4b). Within the thermo-mechanically affected zone (TMAZ) on the advancing side (AS), there are horizontal diffusion bands resulting from the initial rotational movement of the friction stir welding (FSW) tool, displaying a microstructure akin to that of the base metal (see

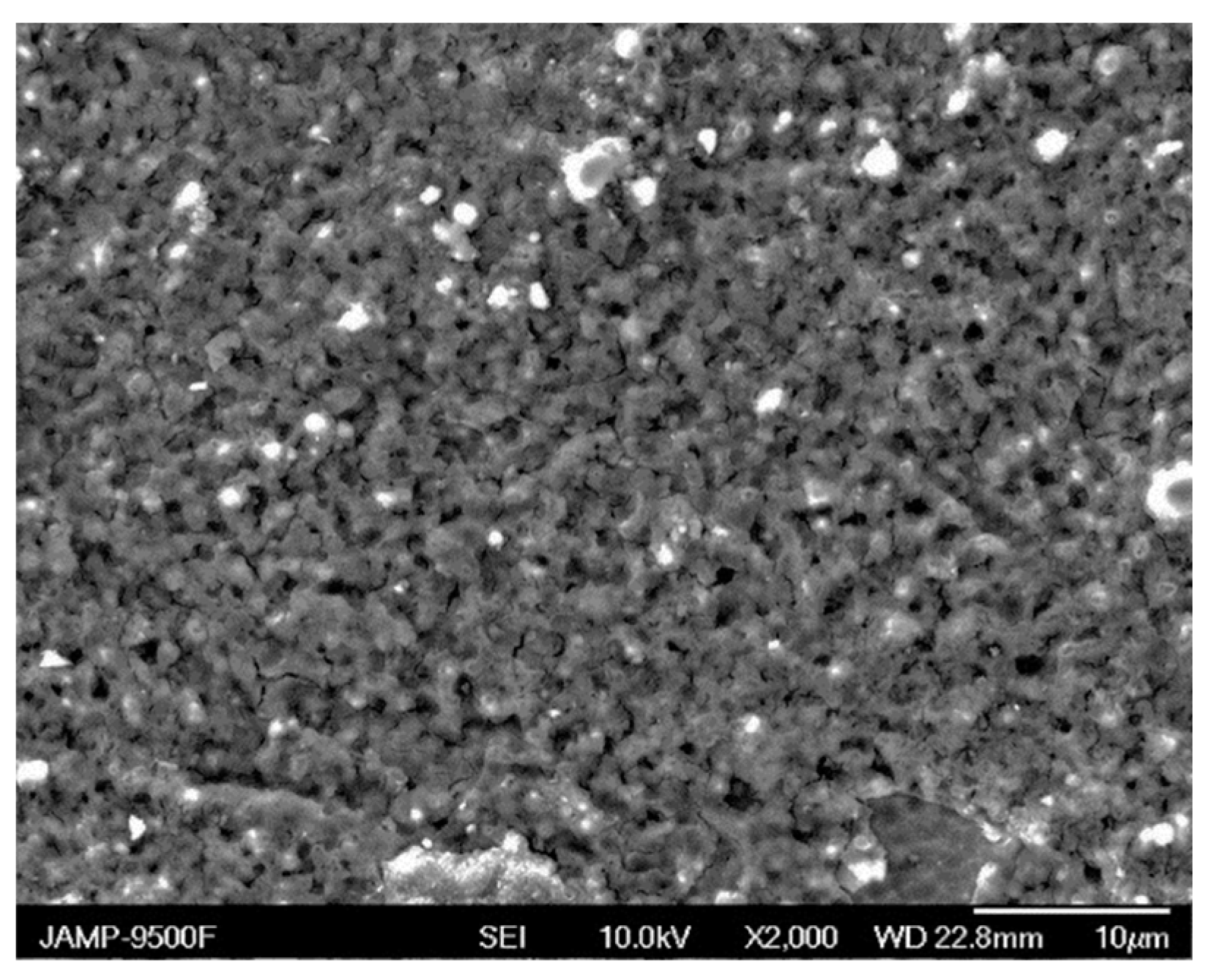

Figure 4c). The increase in the plasticity of the weld material, attributed to heating during the twisting deformation process, causes both the stretching and compression of the grain boundaries. This phenomenon subsequently prompts localized extrusion and recrystallization, ultimately leading to the formation of finely grounded grains ranging from 1 to 10 μm in size (

Figure 4b and

Figure 5).

It is well known that in the temperature range of 550...640 °C in the chemical system Mg-Al-Zn, in which processes of intensive plastic deformation have occurred, the formation of phases enriched with magnesium and aluminum is possible. Significant mobility of atoms at such a temperature allows growth of grains with sizes from 50 nm to 500 nm due to the simultaneous action of diffusion and recrystallization processes.

These recrystallization processes during the mixing of zones with high and low temperature occurs with an in-crease in dislocations density at grain and subgrain boundaries. Lomer-Cottrell junction are created, effectively hindering the movement of dislocations. This occurs due to the development of barriers as a result of their intersecting, which subsequently reduces the formation of new dislocations. Therefore, the more challenging it becomes for dislocations to migrate within the material, the higher the level of strain hardening that occurs. Usually, the formation of a quality highly crushed structure during FSW occurs with the participation of several mechanisms at the same time, and the result depends on the welding conditions, the chemical composition of the material and other factors.

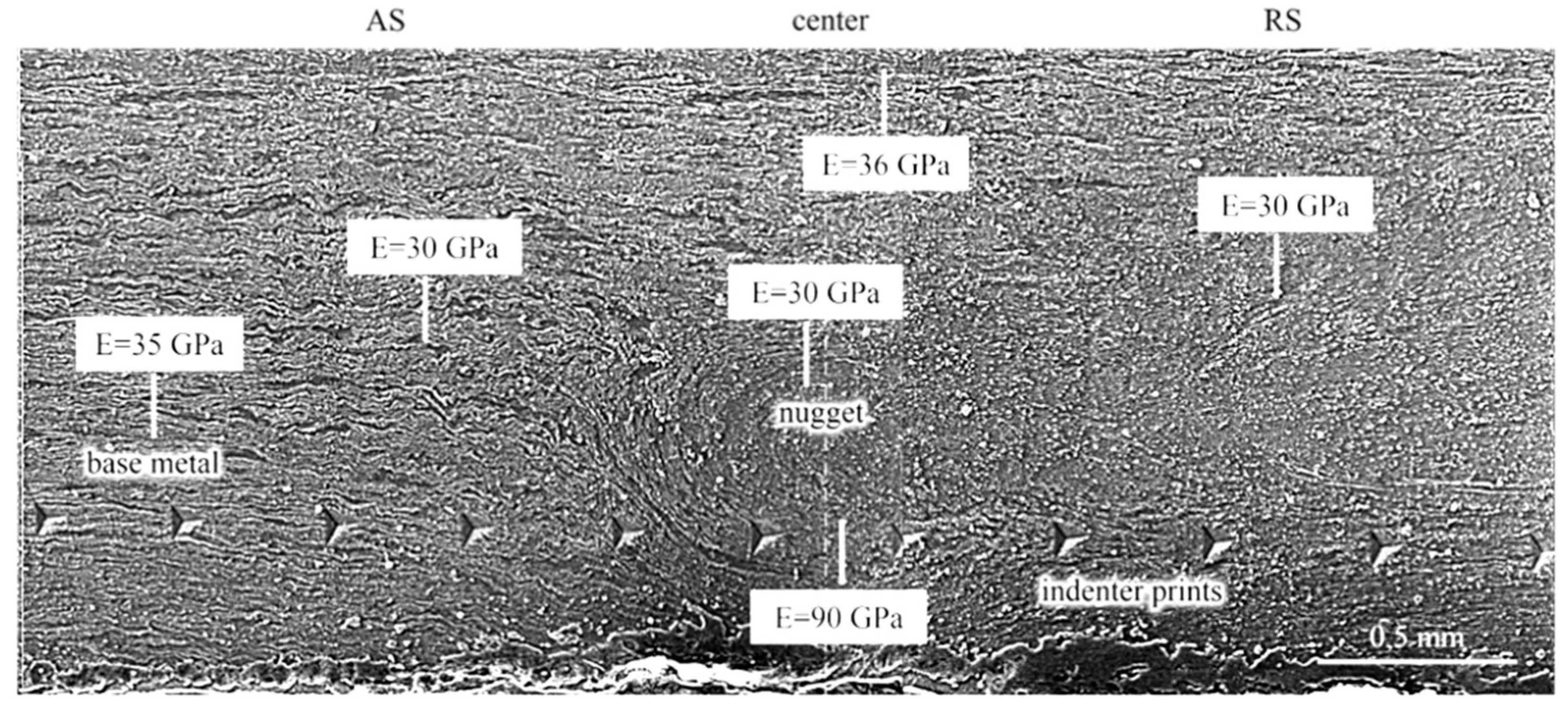

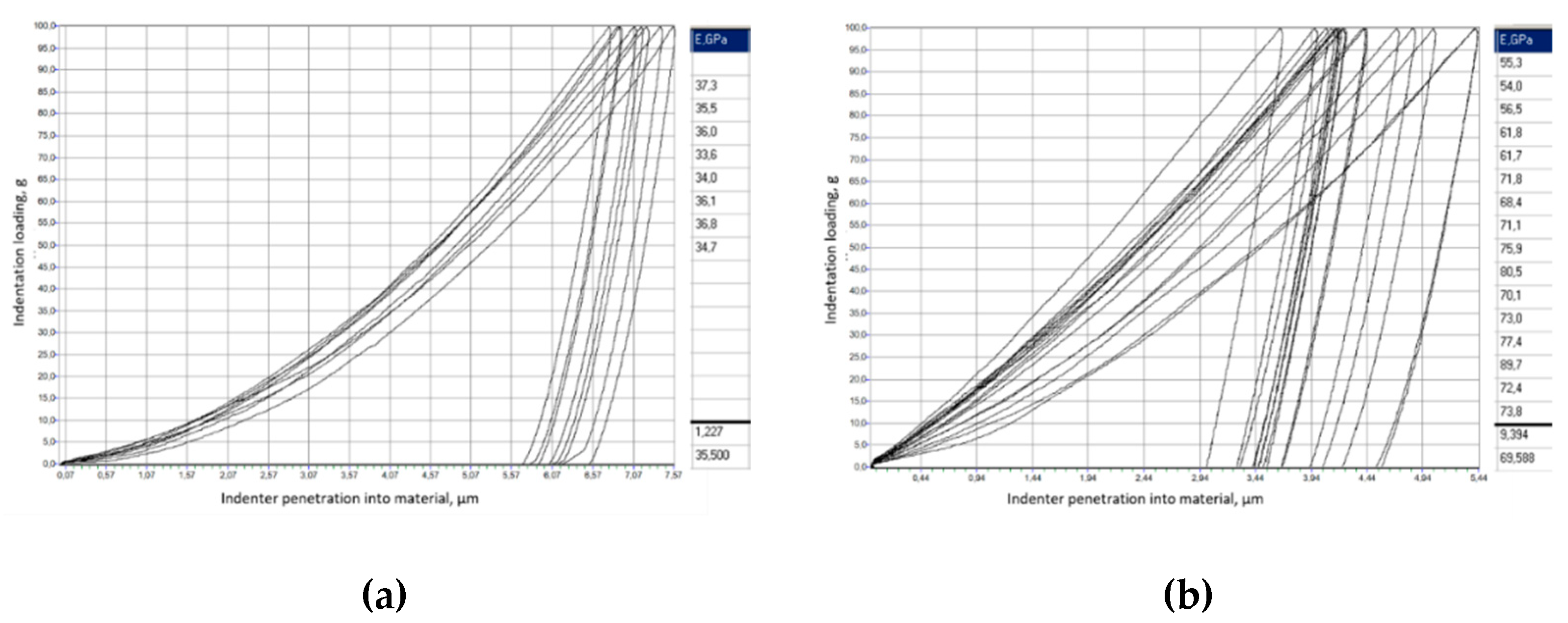

The modulus of elasticity (E) was assessed for five distinct varieties of FSW weld textures, namely the base metal, TMAZ, top, bottom, and core center (

Figure 6). In the central part of the core E=30 GPa, the zone contains an ellipsoidal structure and textures drawn from pressing and rotating the tool at the top and bottom sections of the joint. For the top part of the weld E=36 GPa. At the bottom of the core at a distance of 50-150 μm along the lower edge of the sample, the highest value of E=90 GPa was determined. That is, an increase in elasticity by 2–3 times compared to the base metal E= 35 GPa. For the TMAZ zone, the modulus of elasticity E=30 GPa. A comparison of the shape and depth of the indentation diagrams shows a more plastic state of the base metal (

Figure 7a), and in the central area beneath the center of transverse section there is an increased elastic response of the material surface (

Figure 7b). The penetration depth of the indenter into the base material measures 7.57 μm, with a depth of 5.44 μm observed in the core area situated below the midpoint of the cross-section. This pronounced variation in the textures of the zones within the FSW joints leads to a considerable elastic-deformed state in the thin metal. As a result, the traditional fracture statistics are influenced by the TMAZ zone during tensile strength testing. Consequently, it is generally advisable to conduct an additional heat treatment, which can normalize the material’s condition by approximately 10%. [

9].

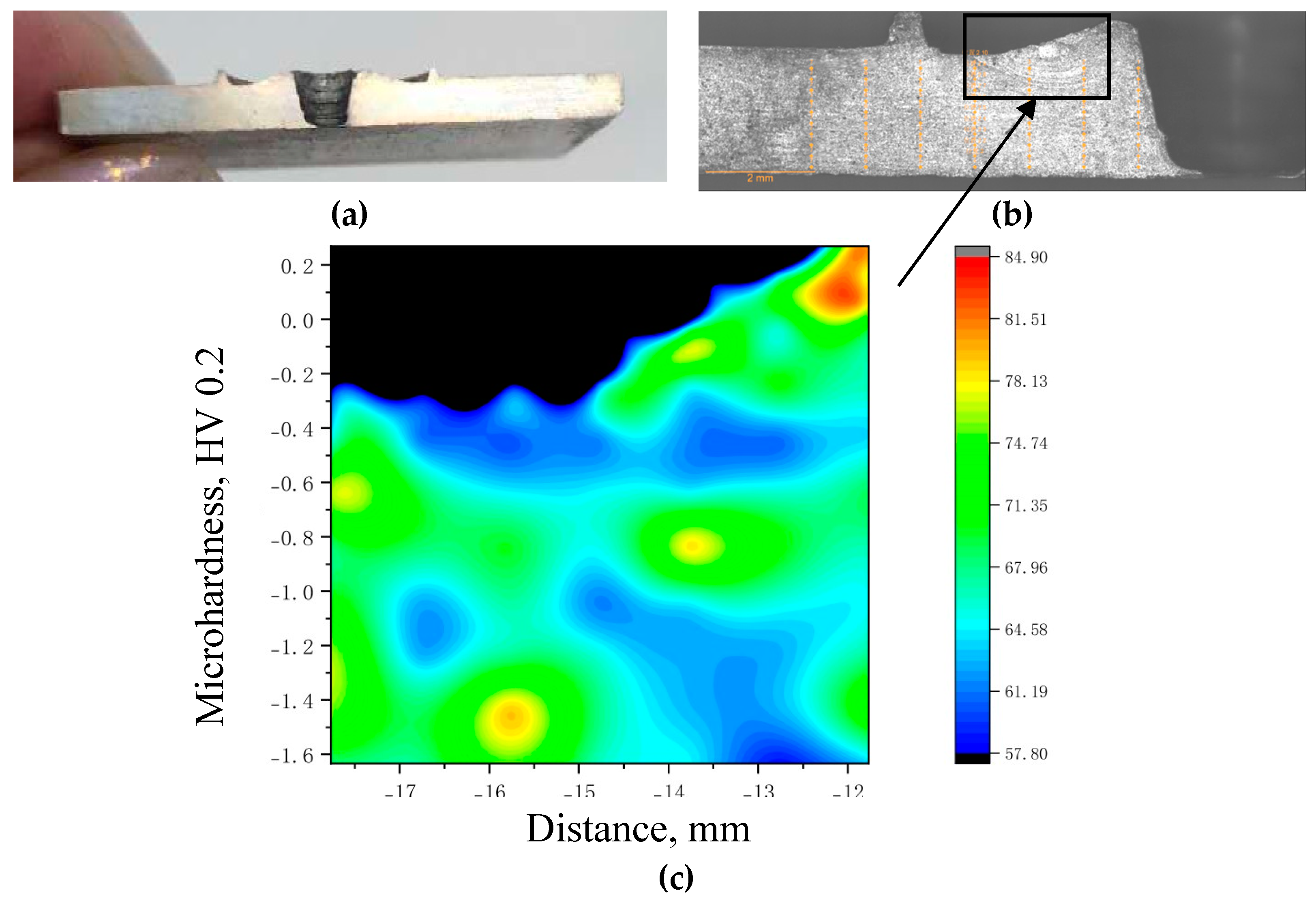

The hardness distribution study, carried out in the direction transverse to the end face of the plate (

Figure 8a), was carried out from the right and left sections of the hole that is raised after the pin tool is immersed (black section in the middle of the sample). The photo clearly shows the ridges formed by the pressure of the shoulder (

Figure 8b) of the pin tool.

The study was conducted on both sides of the sample in order to determine the characteristics of the hardness distribution at the entry of the pin tool (AS) into the metal, and at the exit (RS) from it. The distribution of micro hardness analysis points on the left side is shown in

Figure 8b.

Comparison of the distribution map of micro hardness НV0.2 with the microstructure of the HAZ sample in the welding zone shows a non-uniform distribution of micro hardness over the surface. The hardness changes almost twice – from 57.8 НV0.2 to 84.9 НV0.2. It was found that the areas with the lowest hardness from 57 to 64 НV0.2 correspond to the areas where “vortices” of plasticized metal are formed, that is, when the metal behaves like a hyperelastic-plastic material (Mooney-Rivlin model). The highest hardness level of 80…85 НV0.2 is observed in the TMAZ zone.

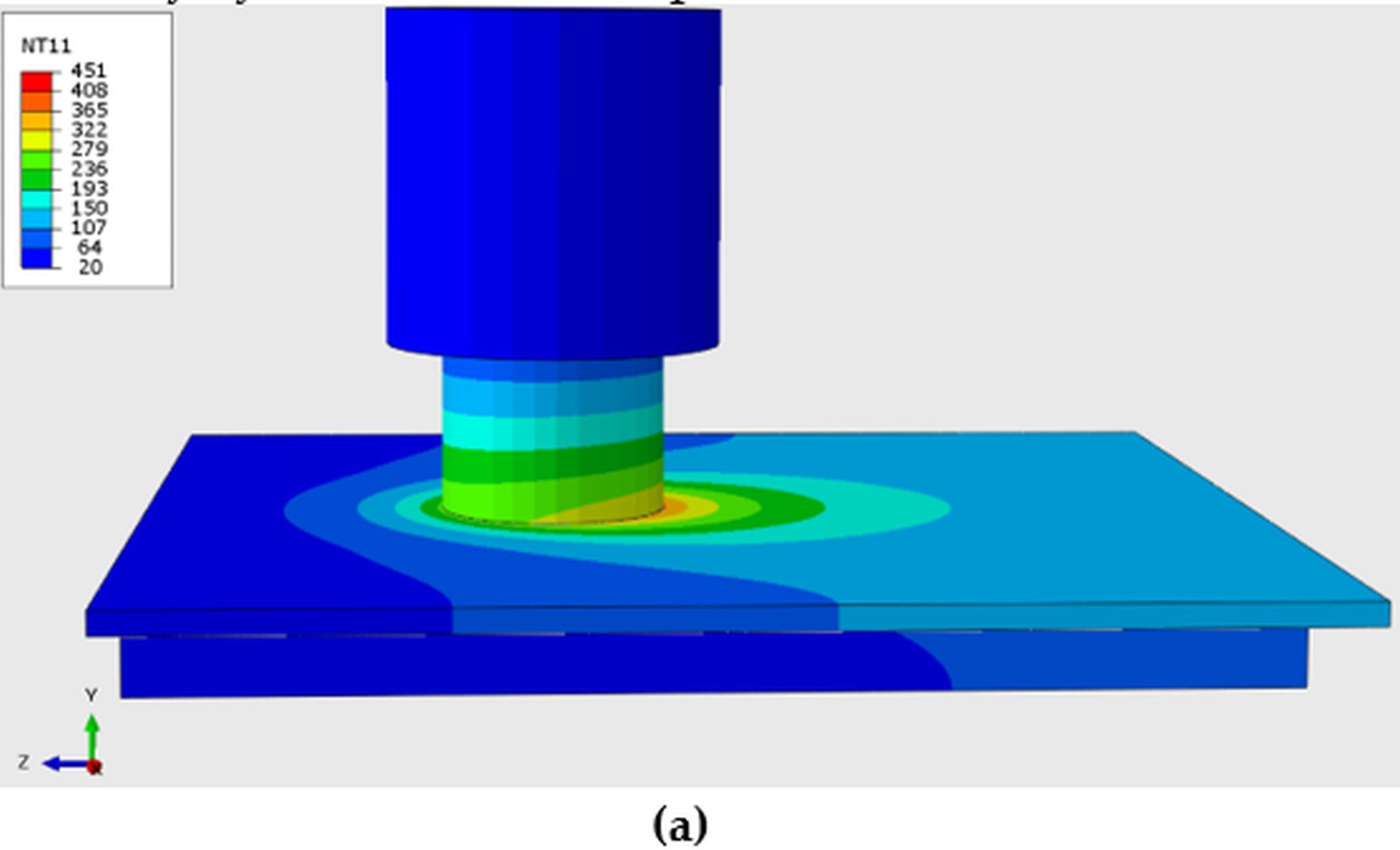

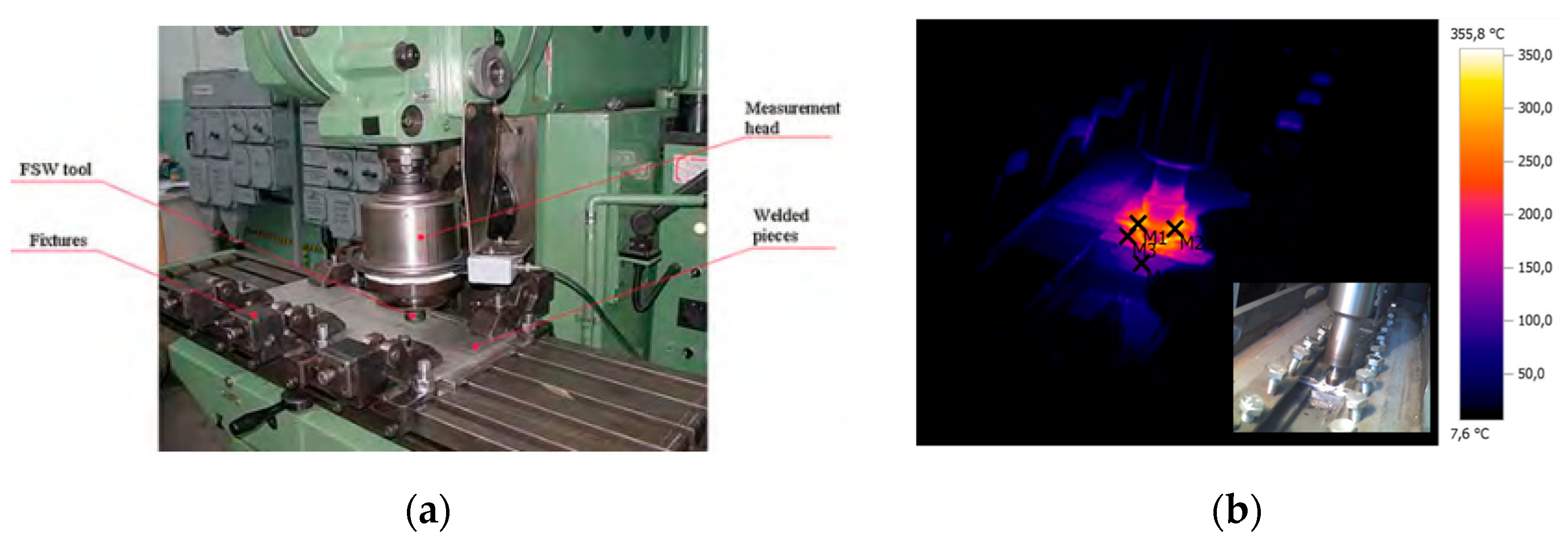

Based on the infrared image obtained from the welding process using the thermal imager (

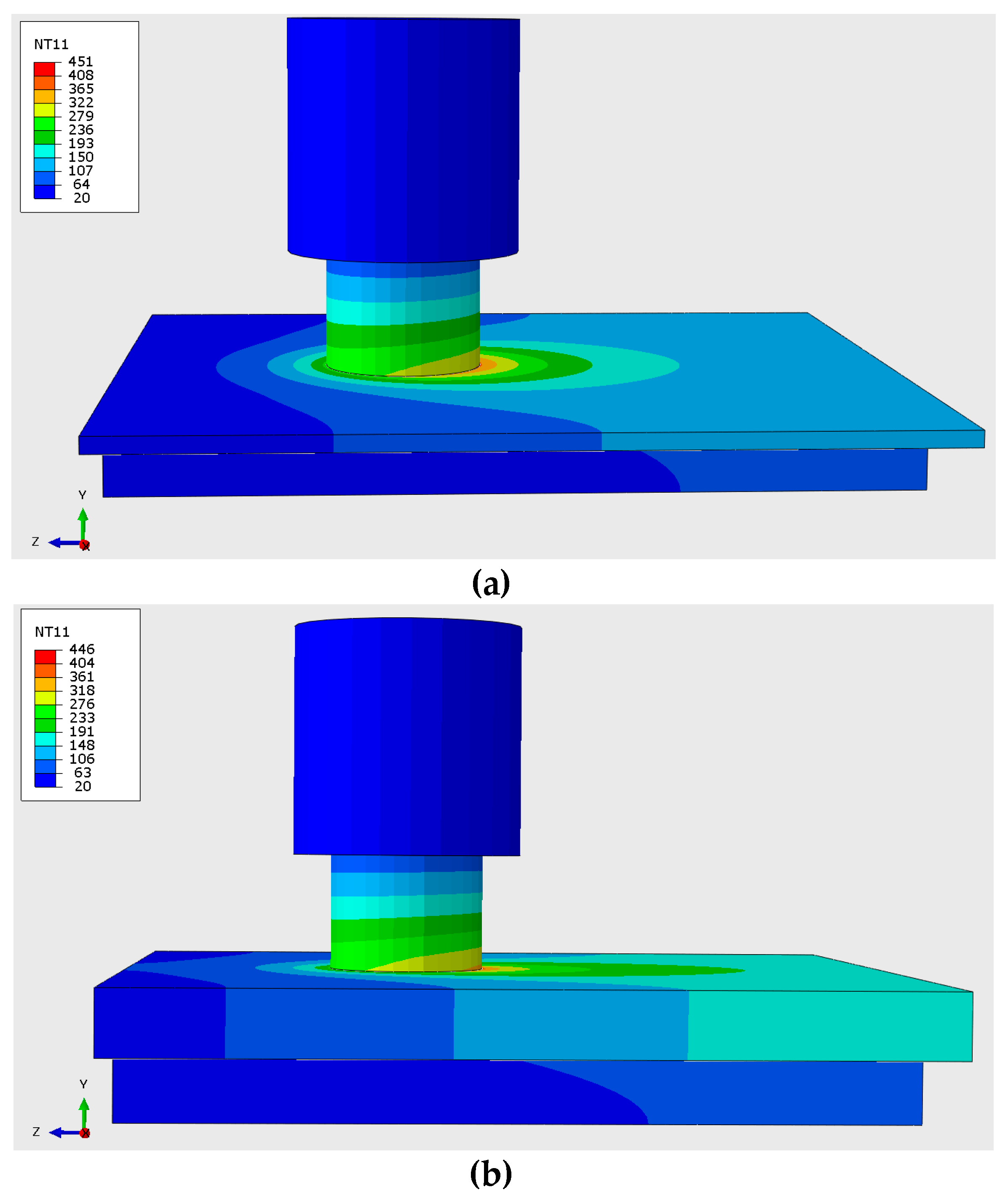

Figure 2), it has been roughly assessed that the temperature of the external surface of the magnesium alloy and the tool during the welding operation does not exceed 355.8°C. The model of the temperature fields with the specified welding parameters (

Figure 9) shows a similar temperature at a small distance from the point of contact of the cylindrical FSW tool with the metal. Following the operation of the FSW, the temperature registers at 410°C. Within the weld core region, where a consolidated microstructure emerges and elasticity is enhanced by a factor of 2-3, the temperature reaches 500°C.

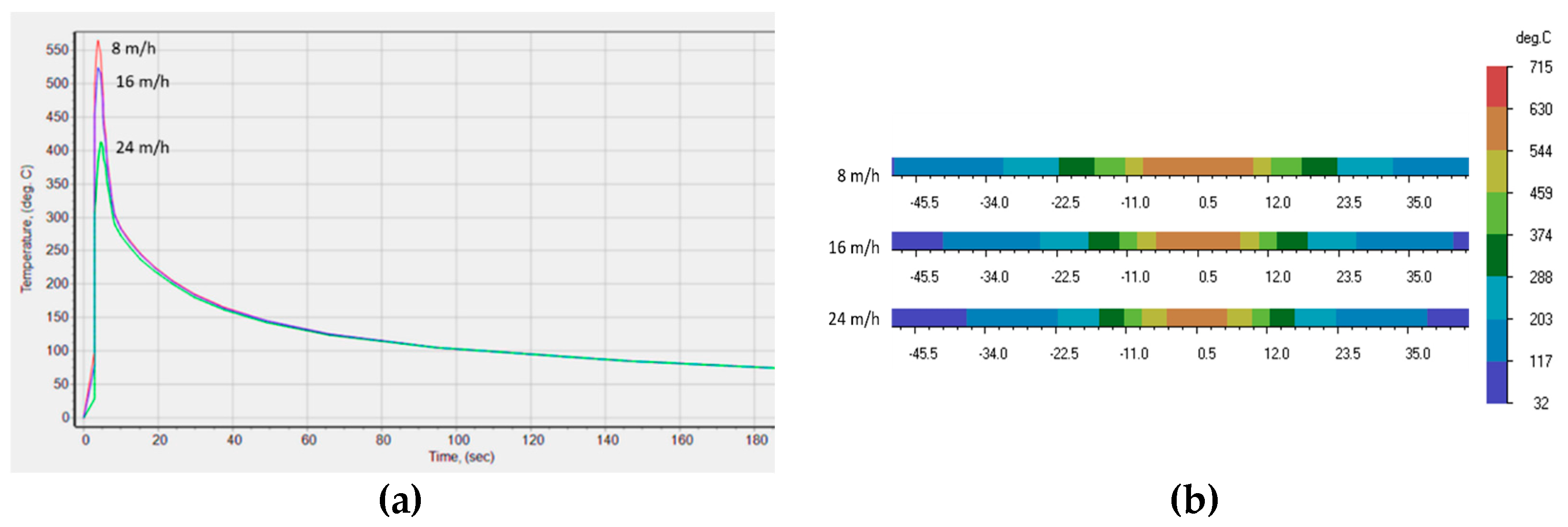

Thermal cycles during FSW and the distribution of maximum temperatures along the volume of the plates depending on the welding speed were plotted by the results of the finite element analysis. The maximum temperature of the thermal cycle (

Figure 10a) is approximately 600°C, and when the linear welding speed is increased above 16 m/h, it changes to 450°C. That is, the maximum temperature in the contact zone of the tool with the material of the plates is mainly deter-mined by the rotational speed and by the pressing force of the tool against the plates. The width of the temperature fields in the joint zone (

Figure 10b) is 8 mm, 6 mm, and 4 mm, with increasing linear speeds step by step from 8 m/h to 24 m/h respectively.

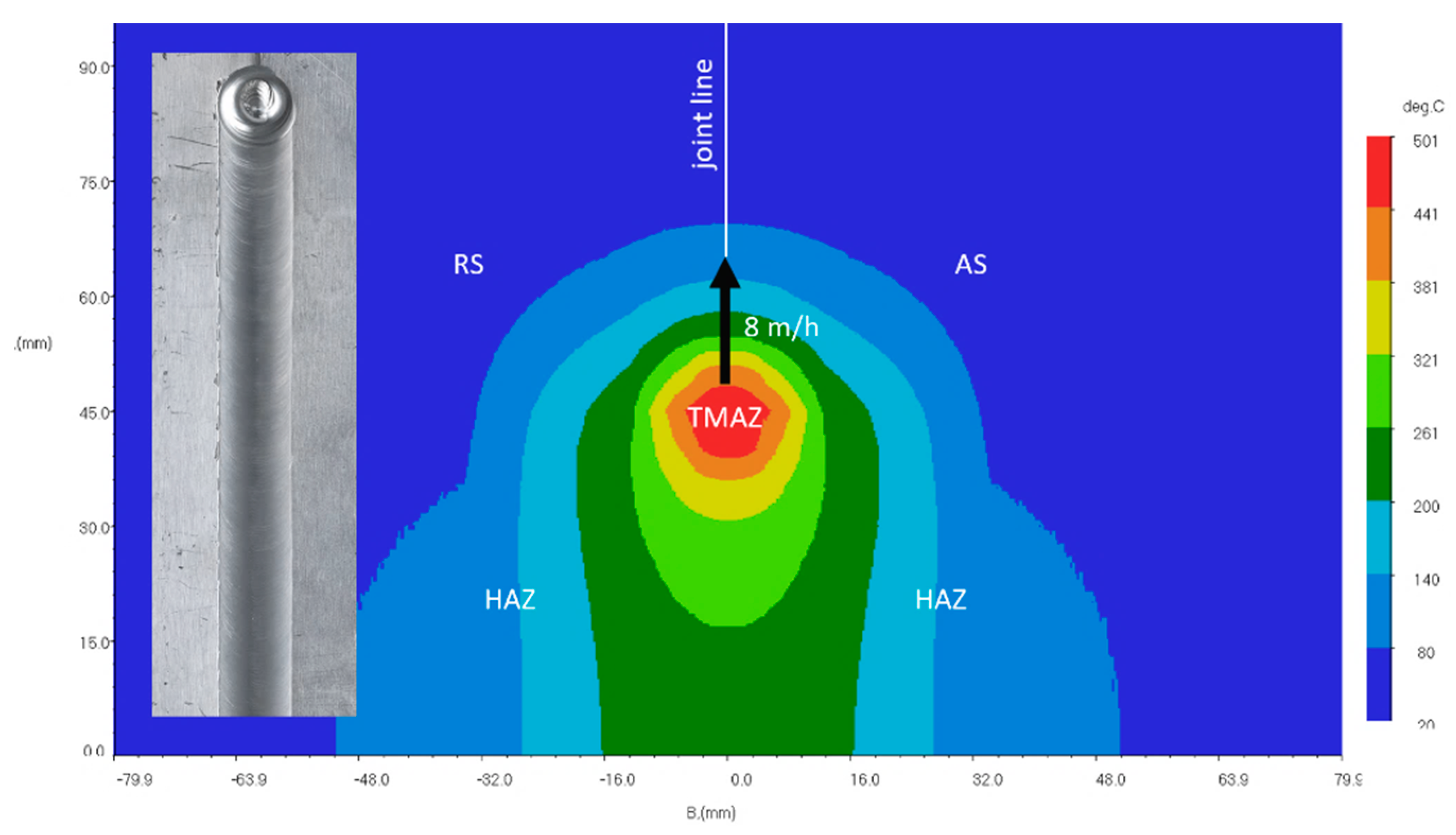

The width of the weld of experimentally obtained samples of FSW joints at a linear welding speed of 8 m/h is approximately 10 mm (

Figure 11) is represented in the calculation data by a similar.

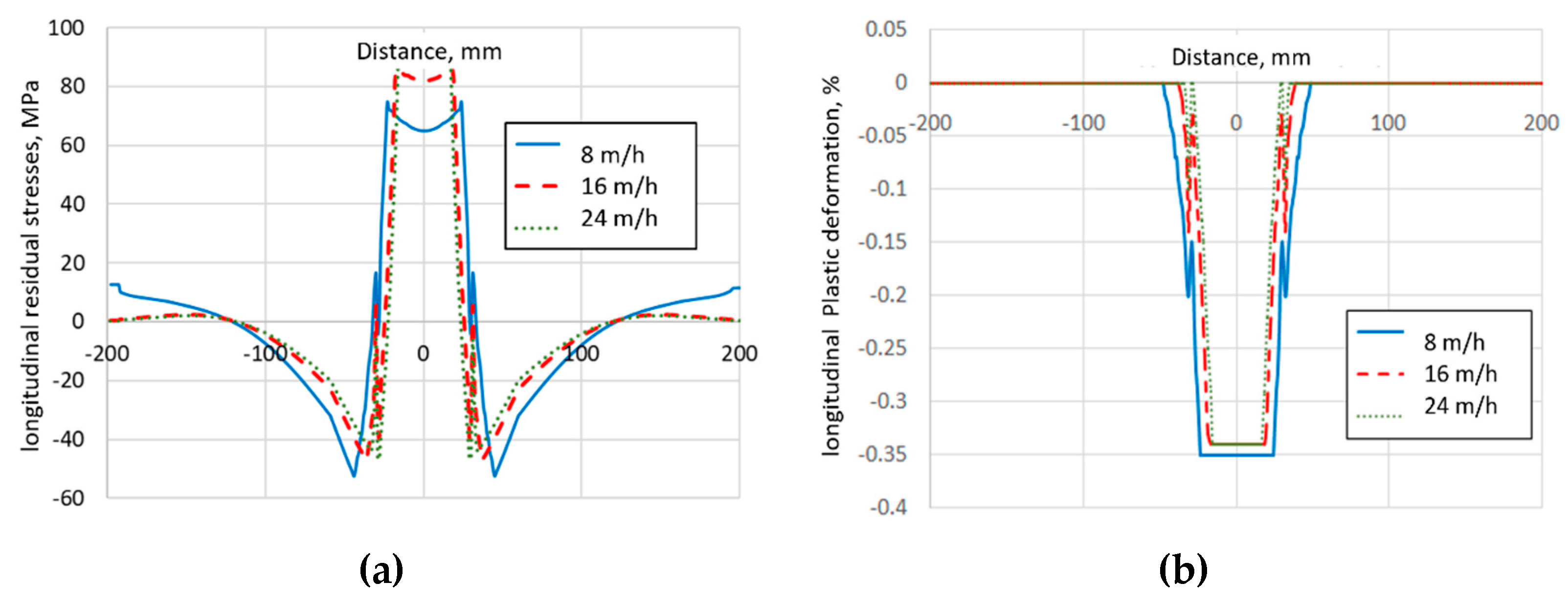

Calculations of the maximum residual tensile stresses showed that they reach the yield point of the material of 140 MPa. The level of the maximum calculated residual plastic shrinkage deformations is relatively low, up to - 0.35% (

Figure 12b). When the linear speed of welding is increased, the maximum residual tensile stresses increase by 10…15%, which is associated with an increase in the temperature gradient during welding. It was also established that residual plastic deformations (longitudinal) have a slight decrease in level with an increase in the linear speed of welding.

The calculations showed that despite the rather significant deviations of the maximum temperatures (24% and 47%, respectively) for different options for taking into account heat dissipation in the tool and the backing plate, the distributions of residual stresses change to a lesser extent. Thus, for the maximum value of tensile stresses, the longitudinal residual stresses when taking into account heat dissipation increase by 5% and 7%, respectively (

Figure 12a), and the transverse ones decrease by 11% and 18%. For the width of the tensile stress zone, the longitudinal residual stresses when taking into account heat dissipation narrow by 17% and 21%, respectively, and the transverse ones almost do not change.

As for the distributions of residual plastic deformations in the butt joint of 2 mm thick magnesium alloy plates (

Figure 12b), the maximum value of the residual longitudinal plastic deformations, taking into account the heat dissipation, increases by 3%, and their width narrows by 18% and 29%, respectively. At the same time, the transverse residual plastic deformations, at the maximum value of the tensile stresses, decrease by 2 and 4 times, respectively, and their width narrows by 1.13 and 1.2 times, respectively.

Thus, taking into account heat dissipation in the working tool and substrate when modeling welding thermal cycles, as well as residual welding deformations and stresses, is important for thin sheets (e.g., 2 mm thick), that can have a substantial impact on the precision of the computed outcomes. In the case of thick sheets (8 mm thick), taking into account heat dissipation in the welding process of magnesium alloys does not lead to a significant increase in the accuracy of the results.