1. Introduction

Soil is a vital component of the natural environment, providing essential services such as biomass production, water filtration, and serving as a habitat for countless organisms [

1,

2]. However, rapid industrialization since the 20

th century has led to significant soil degradation due to the release of harmful pollutants, particularly petroleum hydrocarbons (PHs) and heavy metals [

3,

4]. These contaminants pose serious threats to both ecosystems and human health [

4,

5].

PHs are persistent organic pollutants derived from petroleum-based activities, known for their stability and long-term presence in the soil [

6,

7]. Similarly, heavy metals are toxic and mutagenic, with long-lasting impacts on the environment [

8]. These pollutants frequently co-occur in contaminated sites due to overlapping anthropogenic sources, complicating the remediation process [

9,

10]. The interactions of PHs and heavy metals with soil components can affect their bioavailability, reactivity, and toxicity, leading to unpredictable remediation outcomes [

4,

10,

11]. Compared to single-pollutant remediation, the restoration of multi-polluted soils presents unique challenges. The competition between pollutants for binding sites on soil particles, their impact on soil biota, and their complex interactions all contribute to the difficulty of remediating soils contaminated by both PHs and heavy metals [

4]. Conventional remediation methods, while effective, often involve high costs and can result in further soil disruption [

10].

Phytoremediation has emerged as a promising alternative for restoring multi-polluted soils due to its environmental friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and ability to utilize plants’ natural abilities to degrade, absorb, or stabilize pollutants [

12,

13]. This technology leverages the synergy between plants and soil microorganisms, offering a sustainable solution for contaminated soil restoration. While phytoremediation has been extensively studied for single pollutants like PHs or heavy metals, research on its application to multi-polluted soils is limited [

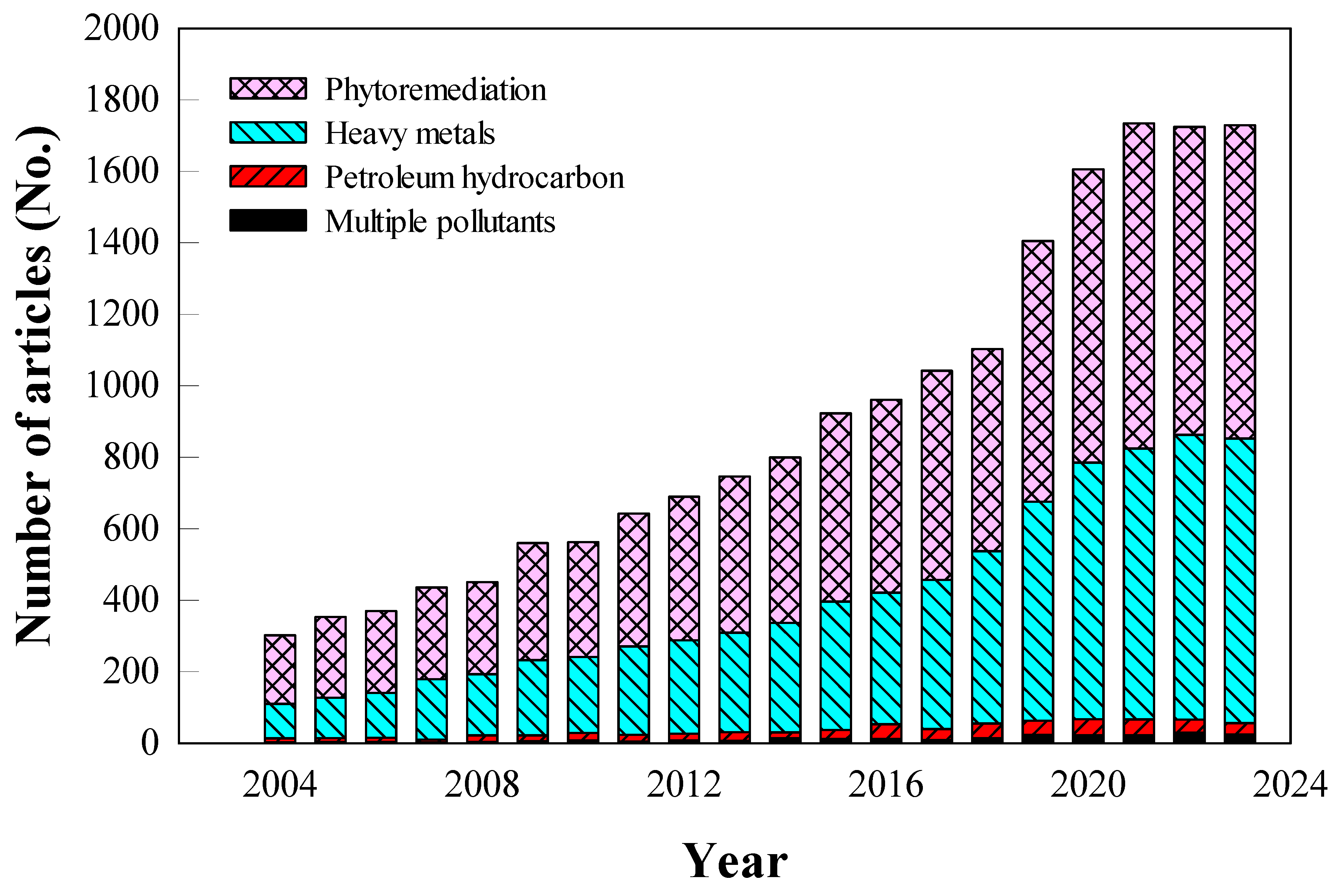

4]. Although interest in phytoremediation has steadily increased over the past twenty years, most research has concentrated on soils contaminated with heavy metals (

Figure 1), leaving the study of multi-pollutant scenarios insufficient. As multi-polluted sites become more prevalent, a deeper understanding of the interactions between PHs and heavy metals and their behavior in soil is essential for advancing phytoremediation techniques.

Recent advances in phytoremediation strategies for multi-polluted soils are explored in this review, addressing the challenges posed by the co-occurrence of PHs and heavy metals. Key phytoremediation mechanisms, challenges, and emerging strategies for enhancing efficiency are examined.

2. Methodology

This review was conducted through a comprehensive analysis of literature on phytoremediation in multi-polluted soils. The research focused on four key areas: (1) the interactions and coo-occurrence of petroleum hydrocarbons (PHs) and heavy metals in contaminated soils, (2) key phytoremediation mechanisms, (3) challenges in remediating multi-polluted soils, and (4) emerging strategies for enhancing phytoremediation.

Data collection was carried out using databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. Search terms included “soil pollution + PHs + heavy metals”, “phytoremediation + PHs + heavy metals” and “enhancement + phytoremediation”. Studies were selected based on their relevance to multi-polluted soils, publication year, methodological rigor, and comprehensiveness. The selection process aimed to ensure a diverse and up-to-date representation of current phytoremediation research.

3. Soil Contamination by Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals

Rapid industrial development has led to the widespread release of various contaminants into soils, particularly PHs and heavy metals [

4,

11]. These pollutants are known for their persistence and harmful effects on ecosystems and human health. PHs, primarily generated through petroleum-based anthropogenic activities, are highly stable and can persist in soil for long periods [

6]. Due to their hydrophobic nature, PHs tend to bind to soil particles, reducing their bioavailability but also extending their environmental persistence [

14]. Heavy metals, such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), and zinc (Zn), are significant environmental pollutants due to their toxicity and mutagenic properties [

8]. Unlike organic pollutants, heavy metals do not degrade over time, making them a long-term challenge for soil remediation [

4,

11].

When these two types of pollutants co-occur, they often interact in complex ways that complicate remediation efforts. For example, interactions between PHs and heavy metals in the soil can alter their speciation, reactivity, and bioavailability [

4]. These interactions can affect the efficiency of remediation processes by changing pollutant mobility, adsorption-desorption dynamics, and the biological activity of soil organisms [

11]. Moreover, PHs and heavy metals compete for sorption sites on soil particles, which further influences their environmental behavior [

4]. Given the complexity of their interactions, soils contaminated by both PHs and heavy metals require a multifaceted remediation approach tailored to the specific contaminants and soil conditions present [

4,

10].

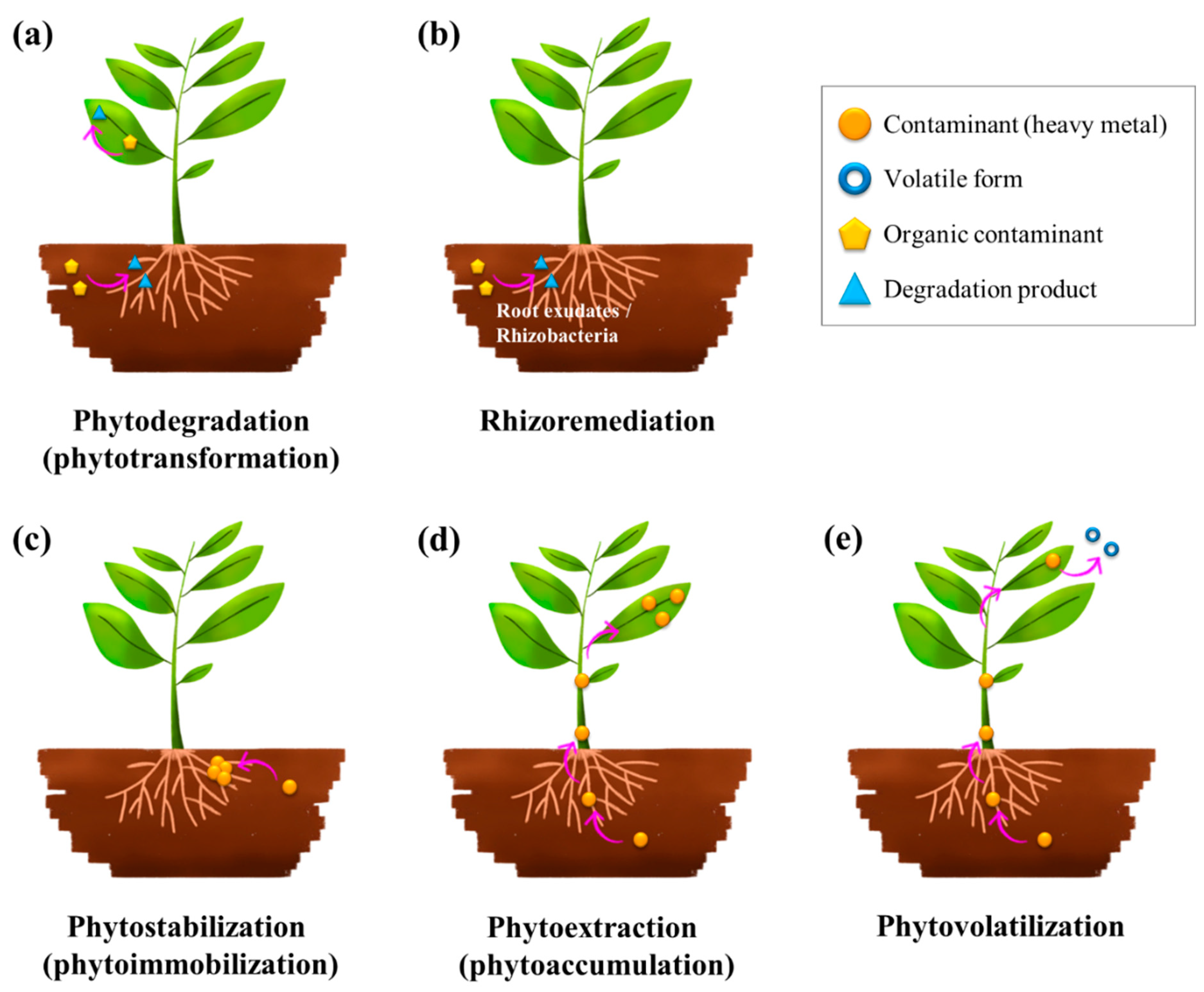

4. Phytoremediation as a Sustainable Solution

Phytoremediation is an emerging, eco-friendly technology that leverages the natural capabilities of plants to remove stabilize, degrade, or sequester pollutants from contaminated soils [

6,

12,

15]. Compared to traditional physical and chemical methods, phytoremediation is cost-effective, less disruptive to the environment, and sustainable [

16]. Various mechanisms underlie phytoremediation, and these mechanisms depend on the plant species, type of contaminant, and soil conditions [

12,

13]. Below, the main type of phytoremediation are described in detail (

Figure 2).

4.1. Phytodegradation

Phytodegradation, also known as phytotransformation, involves the uptake and subsequent breakdown of organic pollutants by plants through enzymatic processes (

Figure 2a). [

17,

18]. Plants secrete enzymes such as dehalogenase, oxygenase, and peroxidase, which break down complex organic pollutants, including PHs, into simpler and less toxic compounds [

6,

19]. These enzymes catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions that transform pollutants within plant tissues or the rhizosphere (the soil region near plant roots). Phytodegradation has been shown to be effective in degrading of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and pesticides [

19]. For instance, Etim (2012) reported that enzymes such as peroxidases in plants like

Populus species can effectively degrade organic pollutants in contaminated soils. Phytodegradation is advantageous as it can function effectively in soils with low microbial populations, allowing plants to tackle higher pollutant concentrations that might be toxic to microorganisms. However, a limitation is that the metabolic by-products formed inside plant tissues can sometimes be difficult to trace, making it challenging to assess complete degradation [

6].

4.2. Rhizoremediation

Rhizoremediation, also known as rhizodegradation, is a form of phytoremediation that relies on the synergistic interactions between plant roots and rhizosphere microorganisms to degrade pollutants (

Figure 2b) [

6,

20]. In this process, plant roots release exudates (organic acids, amino acids, and sugars) that stimulate microbial growth and activity in the rhizosphere [

20,

21]. These microbes, in turn, play a critical role in degrading organic contaminants like PHs [

22]. Grasses such as

Festuca arundinacea (tall fescue) and legumes like

Glycine max (soybean) have been found to enhance microbial degradation of PHs in the rhizosphere [

21]. These plant support diverse microbial communities that can break down complex hydrocarbons. The advantage of rhizoremediation is that it enhances the natural breakdown of pollutants in the soil through microbial activity, making it particularly effective for PHs-contaminated soils. However, the process can be slow and may require additional nutrient inputs to support both plant and microbial growth [

6].

4.3. Phytostabilization

Phytostabilization, also known as phytoimmobilization, is the process by which plants immobilize contaminants in the soil, thereby preventing their migration to groundwater or air (

Figure 2c) [

19,

23]. This mechanism is particularly effective for heavy metals and other inorganic pollutants. Instead of removing the contaminants from the soil, plants restrict their movement by adsorbing them onto root surfaces or precipitating them in less bioavailable forms within the rhizosphere [

6]. Plants like

Vetiveria zizanioides (vetiver grass) and

Populus species have been used to stabilize heavy metals such as lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) in contaminated soils, preventing these metals from leaching into groundwater or becoming airborne [

23]. The key benefit of phytostabilization is its ability to reduce the risk of contaminant migration without significantly altering the soil’s structure or composition. However, this method does not remove the pollutants, so long-term monitoring is necessary to ensure that the contaminants remain immobilized effectiveness (Awa and Hadibarata, 2020).

4.4. Phytoextraction

Phytoextraction, also known as phytoaccumulation, involves the uptake of contaminants from the soil by plant roots and their subsequent translocation to the above-ground parts of the plant (shoots and leaves) (

Figure 2d) [

20,

24]. Once the pollutants, typically heavy metals, accumulate in the plant tissues, the plants are harvested and removed from the site, thus reducing the overall contamination level in the soil. Hyperaccumulator plants such as

Brassica juncea (Indian mustard) and

Helianthus annuus (sunflower) are often used for phytoextraction due to their ability to accumulate high levels of metals [

20]. Over time, repeated planting and harvesting of these plants can significantly reduce metal concentrations in contaminated soils [

15]. Phytoextraction is particularly useful for sites contaminated with heavy metals, as it offers a permanent solution by removing the metals from the soil. However, the process is slow, and plants used in phytoextraction may require several growing seasons to achieve meaningful pollutant removal. Additionally, proper disposal or treatment of the harvested plant biomass is necessary to prevent secondary contamination [

17].

4.5. Phytovolatilization

Phytovolatilization involves the uptake of contaminants from the soil or water, their conversion into volatile forms within the plant, and their subsequent release into the atmosphere through transpiration (

Figure 2e) [

15,

17]. This mechanism is effective for certain volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as well as some heavy metals that can be transformed into gaseous form, such as mercury (Hg), selenium (Se), and arsenic (As). Certain species of poplar trees (

Populus) have been found to take up selenium (Se) and release it as a volatile form (dimethyl selenide) through their leaves [

20]. Phytovolatilization is advantageous because it allows pollutants to be removed from the soil and released into the atmosphere in less toxic forms. However, this method may pose risks if the volatilized forms of the pollutants redeposit in the environment or cause secondary contamination [

6].

5. Challenges in Phytoremediation of Multi-Polluted Soils

The remediation of soils contaminated by multiple pollutants, such as PHs and heavy metals, presents significant challenges due to the complex interactions between these contaminants. Unlike soils contaminated by a single pollutant, multi-polluted soils involve a range of unpredictable physicochemical and biological processes that complicate remediation efforts [

4,

11]. Below are some of the key challenges associated with phytoremediation in multi-polluted soils.

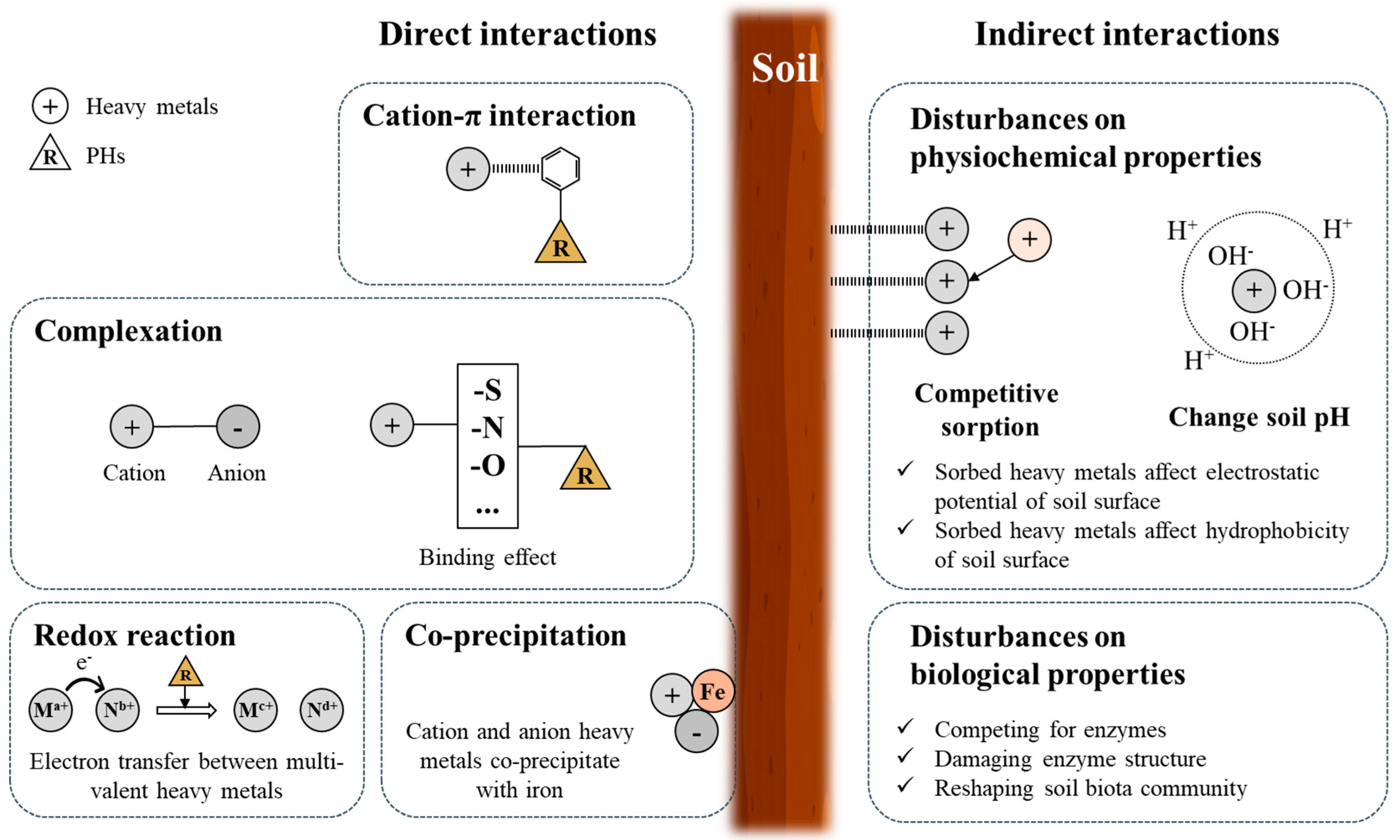

5.1. Chemical Interactions Between Pollutants

In multi-polluted soils, complex interactions between PHs and heavy metals significantly affect their bioavailability, reactivity, and toxicity, complicating remediation efforts [

4].

Figure 3 illustrates key mechanisms of these chemical interactions, including cation-π interactions, complexation, redox reactions, and co-precipitation.

Cation-π interactions are particularly common in soils contaminated with both heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Cationic heavy metals such as Cu, Pb, and Zn can adsorb onto soil particles and create additional sorption sites for PAHs, enhancing their binding and persistence in the soil [

4]. For example, studies have shown that Cu and Zn increase the sorption of PAHs in soils by facilitating cation-π interactions, ultimately reducing PAH mobility [

25,

26].

Complexation, another crucial mechanism, occurs when PHs and heavy metals bind together, forming stable complexes that alter their environmental behavior [

4]. Pollutants such as cadmium (Cd) and arsenic (As) often co-exist with PHs, forming cross-linking agents that reduce the mobility of both contaminants [

4,

27]. Jiang et al. (2013) observed that Cd and As form complexes with goethite in multi-polluted soils, reducing their bioavailability and environmental risk.

Redox reactions also play a key role in soils contaminated with both heavy metals and PHs. The presence of organic pollutants can alter the redox state of metals, influencing their mobility [

4]. For example, organic matter can promote the reduction of metals like chromium (Cr) from toxic Cr(VI) to less harmful Cr(III), making remediation more effective [

4].

Finally, co-precipitation occurs when cationic and anionic metals precipitate together, further immobilizing contaminants. This is especially relevant in iron-rich soils where pollutants such as Cd and As(V) co-precipitate, limiting their leaching into groundwater [

27].

Chemical interactions between PHs and heavy metals in multi-polluted soils create significant challenges for remediation. These interactions not only increase the persistence of pollutants in the soil but also complicate the efficiency of phytoremediation strategies by altering their mobility and bioavailability. Effective remediation must account for these complex interactions to tailor approaches that consider site-specific conditions.

5.2. Disruption of Soil Biota

Soil microorganisms are critical to the success of phytoremediation, particularly in the breakdown of organic pollutants. However, the presence of heavy metals can inhibit microbial activity, disrupt microbial community structures, and interfere with enzymatic pathways essential for the degradation of pollutant [

28]. For instance, heavy metals like Cd and Pb are known to interfere with microbial enzymes, making it harder for microbes to break down hydrocarbons effectively [

10].

In multi-polluted soils, the co-existence of PHs and heavy metals can lead to further disruptions in biological processes. Microorganisms that would typically degrade organic pollutants may experience reduce efficiency due to heavy metal toxicity. Additionally, some metals can directly damage microbial cells or inhibit the production of enzymes necessary for bioremediation [

4].

Microbial community structure is also affected by pollutant co-existence. For example, in soils contaminated with PHs and heavy metals, microbial diversity and abundance often decline, reducing the resilience of soil ecosystems [

4]. This reduction in microbial activity hampers the overall phytoremediation process, making it slower and less effective [

4].

The presence of heavy metals in multi-polluted soils poses a significant challenge to microbial health and activity, thereby undermining one of the key components of successful phytoremediation. Future strategies must focus on enhancing microbial resilience and employing bioaugmentation techniques to restore microbial communities in contaminated soils.

5.3. Unpredictable Pollutant Behavior

Compared to singular pollution sources, the remediation of multiple pollutants such as PHs and heavy metals is highly unpredictable and complex [

9,

10]. Complexes formed by chemical reactions between PHs and heavy metals can alter their physico-chemical properties, affecting their bioavailability [

11]. Furthermore, the kinetics of adsorption and desorption of pollutants are influenced by their competition for binding sites on soil particles, which can alter their transport characteristics within the soil [

11]. Additionally, the coexistence of pollutants affects the metabolites (such as enzymes, biosurfactants, and organic acids) secreted by plants or soil microorganisms, as well as the biological processes of soil biota [

11]. These changes in biological processes can impact the remediation efficiency of other pollutants. Due to the significantly different physicochemical properties of PHs and heavy metals, remediating soil contaminated with both types of pollutants is highly unpredictable [

4,

10]. Furthermore, remediation may sometimes require external chemicals and additional costs or could alter the soil’s physicochemical properties [

4,

10].

The unpredictable behavior of pollutants in multi-polluted soils highlights the complexity of remediating such environments. These unpredictable dynamics require adaptive remediation strategies that can respond to varying conditions and pollutant interactions.

5.4. Environmental and Economic Considerations

Phytoremediation is generally considered an eco-friendly and cost-effective solution for contaminated soils. However, when applied to multi-polluted soils, the process can be slow, often requiring extensive time and resources to achieve meaningful remediation [

20]. Large-scale applications can become economically unfeasible, particularly for highly polluted industrial sites where quick remediation is essential.

For instance, phytoremediation through phytoextraction requires multiple plant growth cycles to accumulate heavy metals, while phytostabilization demands long-term monitoring to ensure that immobilized contaminants remain stable in the soil [

20]. Additionally, disposal or treatment of contaminated plant biomass adds to the operational costs of remediation projects. The economic burden is compounded when external inputs such as fertilizers or soil amendments are needed to support plant growth and enhance pollutant bioavailability [

12]. In some cases, additional costs arise from the need to address secondary contamination risks, such as volatilized pollutants or leaching from immobilized metals.

While phytoremediation offers a sustainable solution for multi-polluted soils, its slow pace and resource-intensive nature pose significant economic challenges. Achieving cost-effective and environmentally sustainable remediation will require integrating phytoremediation with other complementary methods and investing in long-term site management.

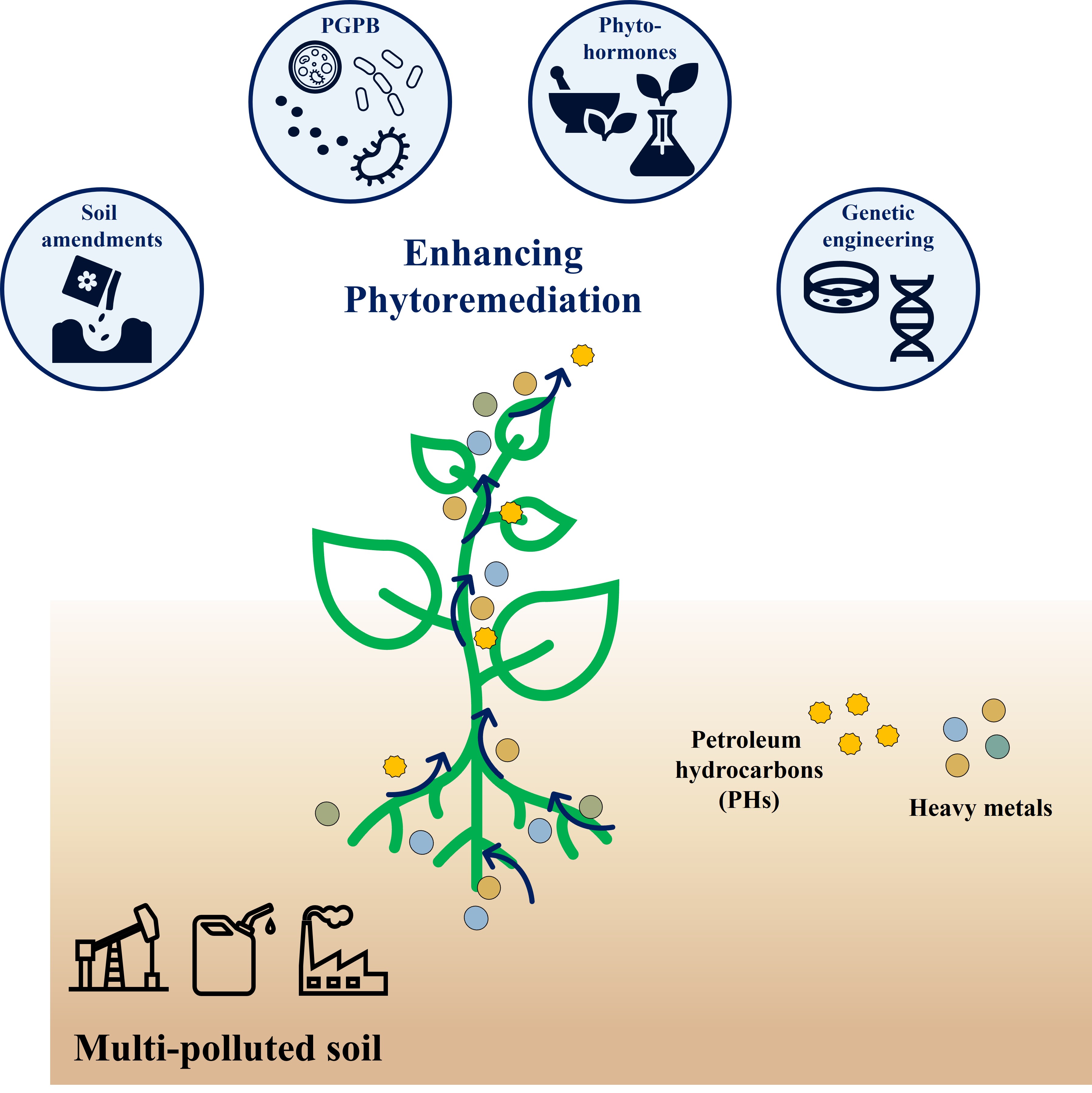

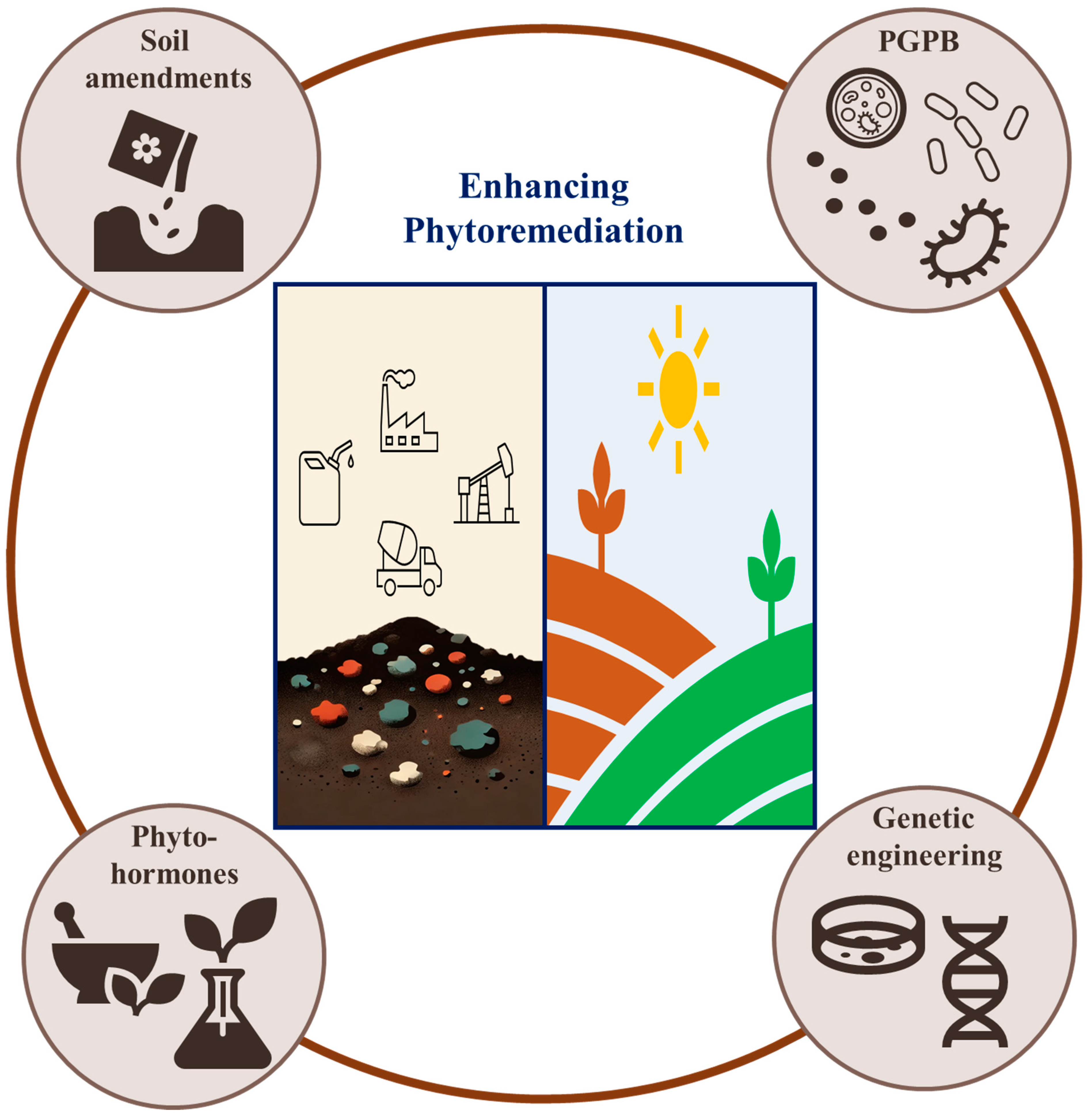

6. Strategies for Enhancing Phytoremediation

Enhancing the efficiency of phytoremediation in multi-polluted soils requires innovative strategies that improve the bioavailability of pollutants, strengthen plant-microbe interactions, and increase the overall resilience of plants. Several approaches have been developed to address the challenges associated with multi-pollutant environments, including the use of soil amendments, phytohormones, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), and genetic engineering (

Figure 4). These strategies aim to optimize the remediation process and achieve faster, more sustainable results.

6.1. Soil Amendments

Soil amendments play a crucial role in enhancing phytoremediation by modifying the physical, chemical, and biological properties of contaminated soils. These amendments can improve plant growth, boost microbial activity, and increase pollutant bioavailability, ultimately making phytoremediation more effective [

12,

13]. Soil amendments can be broadly categorized into two types: environmental functional materials (EFMS) and chemical reagents.

6.1.1. Environmental Functional Materials (EFMs)

EFMs, including biochar, woodchips, sawdust, and agricultural by products, show significant potential for enhancing phytoremediation [

13,

29,

30]. Researchers widely study biochar, produced from organic residues through pyrolysis, for its ability to improve soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability pyrolysis (Al-Wabel et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2020). Its porous structure supports plant growth and provides a habitat for beneficial microorganisms, while its large surface area and high CEC can enhance the bioavailability of heavy metals and organic pollutants [

12,

13]. Research has demonstrated that biochar amendments improve the removal efficiency of both heavy metals and PHs. For instance, the application of biochar in soils contaminated with Zn, PB, and Cd enhanced the uptake of these metals by

Z. mays (maize) and

M. sativa (alfalfa) (Al-Wabel et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2022a; Rashid et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020). Additionally, biochar improves microbial diversity and boosts soil enzyme activities, which are crucial for the degradation of organic pollutants.

Other EFMs such as woodchips, husks, and sawdust can also be used to enhance phytoremediation by improving soil porosity, field capacity, and organic matter content [

13,

34]. For example, sawdust has been shown to significantly increase the biodegradation rate of PHs in contaminated soils [

35]. These materials act as bulking agents, facilitating large-scale remediation efforts by supporting microbial growth and pollutant bioavailability.

6.1.2. Chemical Reagents

Chemical reagents used to enhance phytoremediation include both organic and inorganic fertilizers, as well as chelating agents [

13]. Organic fertilizers, derived from animal manure or plant residues, supply essential nutrients to plants, promoting overall biomass growth and enhancing the phytoremediation process [

33,

36]. Phosphorus fertilizers address nutrient deficiencies and stimulate root development, further enhancing plant tolerance to stress caused by pollutants [

13].

Chelating agents, such as EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) are particularly effective in enhancing the uptake of heavy metals by plants. EDTA forms complexes with metals, increasing their solubility and availability for plant absorption [

37,

38]. Studies have shown that the addition of EDTA significantly improves the efficiency of phytoextraction, facilitating the removal of heavy metals from contaminated soils [

38]. However, care must be taken to prevent the excessive mobility of metals, which can lead to groundwater contamination.

Soil amendments, whether through EFMs or chemical reagents, offer promising ways to enhance phytoremediation by improving soil conditions, promoting plant growth, and increasing pollutant bioavailability. Their effectiveness, however, depends on careful consideration of site-specific conditions and pollutant types.

6.2. Phytohormones

Phytohormones play a pivotal role in regulating plant growth and their responses to abiotic stresses such as soil contamination [

39]. Low concentrations of phytohormones, such as 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCD), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellins (GA), and abscisic acid (ABA) have been shown to significantly enhance plant resilience, making them valuable in phytoremediation strategies [

39].

ACCD hydrolyzes 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carbosylate (ACC), a precursor of stress ethylene, into α-ketobutyrate and ammonia, thereby mitigating ethylene-induced stress in plants [

40]. IAA, an auxin hormone, promotes root elongation and shoot growth, helping plants to cope with the toxicity of heavy metals and organic pollutants [

12]. Ga, on the other hand, reduce oxidative stress in plants by regulating antioxidant metabolism, improving their ability to survive and thrive in contaminated soils. ABA is critical for regulating water use efficiency and stress responses, ensuring that plants maintain growth under adverse conditions [

12]. Strategically applying these phytohormones to contaminated soils can accelerate plant establishment and improve the overall efficiency of phytoremediation.

Phytohormones offer an effective way to enhance plant resilience and performance in contaminated soils. By modulating plant growth and stress tolerance, they can significantly improve the outcomes of phytoremediation efforts.

6.3. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB)

Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) are beneficial microorganisms found in the rhizosphere that enhance plant growth and contribute to pollutant degradation [

40,

41]. PGPB assist phytoremediation through various mechanisms, including nitrogen fixation, nutrient solubilization, and the production of growth-stimulating compounds, such as ACCD and IAA [

40,

41].

Certain PGPB species, such as

Bacillus,

Pseudomonas, and

Acinetobacter, are particularly effective in degrading PHs by producing biosurfactants that increase the solubility and bioavailability of hydrophobic pollutants [

3,

42]. These substances enhance the solubilization and dispersion of hydrophobic pollutants, increasing their availability for microbial degradation or plant uptake [

3]. While bacteria cannot directly degrade heavy metals, they impact the fate of these pollutants through various mechanisms [

40]. For example, some PGPB produce chelating agents like siderophores, which bind to heavy metals, thereby reducing their mobility and improving their uptake by plants [

40]. Additionally, PGPB can facilitate phosphate solubilization and induce redox changes in the soil, further influencing the bioavailability and uptake of heavy metals by plants [

40]. Consequently, inoculating soil with PGPB holds significant promise for enhancing both plant biomass yield and pollutant bioavailability, offering a synergistic approach to phytoremediation [

41]. By harnessing the capabilities of these beneficial bacteria, phytoremediation efforts can be optimized to more effectively address soil contamination challenges.

Genus

Bacillus,

Pseudomonas,

Enterobacter, and

Klebsiella, are prominent PGPB that have been widely studied for their beneficial traits [

8]. However, research specifically addressing the enhancement of phytoremediation in soils contaminated with both PHs and heavy metals through PGPB inoculation is relatively scarce.

Table 1 summarizes previous studies on this topic. Cao et al. (2022) demonstrated that inoculating a microbial consortium of

Bacillus and

Sphingobacterium into alfalfa (

M. sativa) and black nightshade (

S. nigrum) grown in soil contaminated with PAHs and heavy metals (Zn, Pb, and Cd) improved both soil enzyme activities and bacterial diversity, leading to enhanced removal of PAHs and Cd. Similarly,

Bacillus sp. KSB7 was inoculated into Kochia (

Brassica scoparia) in soil polluted with PAHs and heavy metals (Pb, Zn, Cu, and Cr), exhibiting plant growth promotion, metal tolerance, and PAHs degradation capabilities (Song et al., 2022a). Franchi et al. (2016) showed that a bacterial consortium consisting of

Bacillus,

Ralstonia,

Microbacterium,

Curtobacterium, and

Pimelobacter, enhanced the phytoremediation of hydrocarbons, Cu, and Ni in mustard greens (

Brassica juncea). This inoculation led to increased seed germination, improved heavy metal uptake, and a higher removal rate of hydrocarbons. Chen et al. (2017) and Zhang et al. (2020) found that

Klebsiella pneumoniae significantly promoted the growth of triangular club-rush (

Scirpus triqueter) by producing ACCD and IAA, which increased pyrene degradation and Ni bioavailability. In another study,

Novosphingobium sp. CuT1 was inoculated into tall fescue (

F. arundinacea) in soil contaminated with diesel, Cu, and Pb. This inoculation enhanced plant biomass and Cu bioavailability by producing ACCD, IAA, and siderophores (Lee et al., 2023c).

Pseudomonas species are notable for their ability to promote plant growth and assist in the remediation of both PHs and heavy metals. They enhance phytoremediation by producing beneficial enzymes such as ACCD, IAA, and urease, which support plant growth and pollutant degradation (Agnello et al., 2016a; Choden et al., 2021a; Shi et al., 2023a).

PGPB offer a synergistic solution to enhancing phytoremediation by supporting both plant growth and pollutant treatment. Their ability to degrade PHs and increase heavy metal bioavailability makes them indispensable in complex pollution scenarios.

6.4. Genetic Engineering

While PGPB have shown significant promise in enhancing plant growth and pollutant degradation, genetic engineering offers a more targeted approach to address the complex challenges posed by multi-polluted soils. Genetic engineering (genoremediation) has emerged as a powerful tool to improve the efficiency of phytoremediation by modifying plants and microorganisms to better tolerate and detoxify pollutants [

51]. Genetic modifications can involve the creation of genetically engineered microorganisms (GEMs) designed to enhance phytoremediation [

52] or the introduction of functional genes from microorganisms into plants [

39]. Through the introduction of specific functional genes, genetic engineering can improve the efficiency of pollutant uptake, transformation, and removal. Below, the key mechanisms of genetic engineering in the context of phytoremediation are discussed (

Table 2).

6.4.1. Enhancing Metal Resistance and Detoxification

One of the main goals of genetic engineering in phytoremediation is to enhance the resistance and detoxification capacity of organisms exposed to heavy metals. Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) can be engineered to include genes that confer metal resistance, allowing them to better tolerate high levels of toxic metals. For example, the

pbr operon from

Ralstonia metallidurans has been successfully cloned into

E. coli, conferring lead (Pb) resistance. The

pbr operon includes several key genes (

pbrT,

pbrA,

pbrC, and

pbrD), which are responsible for reducing the toxicity of Pb in the hist microorganism [

53]. Similarly, genes such as

cadA and

copM, which confer resistance to cadmium (Cd) and copper (Cu) respectively, have been introduced into various bacterial strains to enhance their detoxification capabilities [

54,

55]. Microorganisms can also be engineered to include genes that transform highly toxic heavy metals into less harmful forms [

56]. For instance, Khoshniyat (2018) isolated the mercuric reductase gene (

merA) from

K. pneumoniae and inserted it into

E. coli, facilitating Hg resistance. Satyapal et al. (2023) isolated the arsenite oxidase gene (

aoxB) from

Pseudomonas sp. strain AK9 and confirmed that recombinant

E. coli exhibited enhanced resistance to arsenic toxicity.

Building on these advancements, a significant application of genetic engineering in phytoremediation involves the introduction of the

merA gene from

Staphylococcus aureus into plant species such as

Populus species [

59]. This modification enhances the plants’ tolerance to ionic mercury (Hg

2+) and facilitates its conversion to elemental mercury (Hg

0), a less hazardous form [

59]. This approach highlights the potential of genoremediatoin to expand the range of pollutants that can be effectively managed through enhanced phytoremediation techniques. By leveraging the unique capabilities of engineered genes, researchers can further improve the efficiency of plants in detoxifying heavy metals, thereby contributing to more sustainable environmental remediation strategies.

6.4.2. Enhancing Metal Uptake and Transport

Genetic modifications can also enhance the uptake and translocation of heavy metals. One approach is to engineer plants to overexpress genes involved in the production of metal-binding proteins or peptides, such as metallothioneins (MTs) and phytochelatins (PCs).

Metallothioneins (MTs) are key components for heavy metal transformation. MTs are proteins that bind to heavy metals and significantly improve metal uptake. Deng et al. (2003) showed that co-expressing MTs with a Ni transport system in

E. coli increased Ni uptake capacity sixfold compared to the unmodified host. De Oliveira et al. (2020) transformed

Saccharomyces cerevisiae with the PtMT2b gene encoding MTs, achieving more than a fivefold increase in Cd uptake. To improve metal uptake and transfer in plants, genetic engineering can enhance the synthesis of metal chelators or transporters. For instance, the introduction of

Pisum sativum MT gene into

Arabidopsis thaliana has led to increased Cu accumulation [

62]. Similarly, phytochelatins (PCs) play a crucial role in metal detoxification and accumulation [

39]. PCs are synthesized in response to toxic metals and form coordination bonds with these metals, facilitating their detoxification or accumulation [

39]. The expression of PC synthase genes, such as AtPCS1, in transgenic plants has been shown to increase the detoxification and accumulation of As and Cd in species like

Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) and

Brassica juncea (mustard green) [

63,

64]. Additionally, overexpression of various PC synthesis enzymes in

B. juncea (mustard green) has been shown to increase the extraction of metals, such as Cu, Pb, Cd, Cr, and Zn, compared to wild-type plants [

65].

6.4.3. Degradation of Organic Pollutants

For the remediation of organic pollutants, the genetic modification of microorganisms to include genes for hydrocarbon degradation is critical. Genes such as

alkB, which encodes alkane monooxygenase, and CYP153, which encodes soluble cytochrome P450 enzymes, are often incorporated into GEMs to enhance the breakdown of PHs [

16]. Research has shown improved hydrocarbon degradation by isolating

alkB or

CYP153 genes from well-known hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, such as

Alcanivorax [

66,

67],

Rhodococcus [

68,

69], and

Pseudomonas [

70]. In addition to modifying microorganisms, enhancing phytoremediation in plants has also been successful. For instance, incorporating the CYP105A1 gene from

Streptomyces into

N. tabacum (tobacco) has led to significant improvements in phytoremediation compared to wild-type plants [

71].

6.4.4. Reducing Stress in Plants

Stress ethylene, produced in response to environmental stressors like heavy metal contamination, can inhibit plant growth and reduce phytoremediation efficiency. Genetic engineering has been used to reduce ethylene levels by introducing the

acdS gene, which encodes ACCD, an enzyme that breaks down the ethylene precursor ACC [

72]. By reducing ethylene production, plants can better tolerate stress, maintain higher growth rates, and improve root development in contaminated environments. This genetic modification has been applied to various plant species, resulting in enhanced phytoremediation performance in multi-polluted soils.

Genetic engineering offers targeted solutions for enhancing phytoremediation by focusing on specific mechanisms, such as metal resistance, pollutant degradation, and stress tolerance. These engineered organisms hold great promise in overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional phytoremediation, especially in the context of complex, multi-polluted environments.

7. Future Prospects

Phytoremediation continues to evolve as a promising and eco-friendly approach to addressing soil contamination. However, the complexity of multi-polluted soils, especially those containing both PHs and heavy metals, requires further research to enhance remediation efficiency. Combining biological products with soil amendments can significantly enhance the phytoremediation process, making it a promising avenue for addressing multi-polluted environments [

73]. There is a need to refine soil amendment techniques and plant species selection to improve pollutant uptake and detoxification, particularly in areas affected by PHs and heavy metals.

Advancements in genetic engineering and plant selection are expected to further boost phytoremediation efficiency. Improving metal uptake mechanisms in plants through genetic modification and optimizing microbial interactions could enhance the ability of plants to tolerate and accumulate pollutants in heavily contaminated soils [

74]. Integrating these strategies with modern biotechnology, such as the use of hyperaccumulator species and bioengineered microorganisms, will be essential to expanding the scope of phytoremediation for complex pollutants.

Moreover, studies have shown that phytoindicators, combined with biomass accumulation and organic amendments, can significantly reduce soil toxicity and improve remediation outcomes [

75]. Future research should focus on identifying the most effective plant species and optimizing organic amendment techniques to further increase pollutant removal and soil restoration.

Furthermore, while most phytoremediation efforts have focused on terrestrial ecosystems, there is growing interest in exploring its potential application in a broader range of environments. For example, adapting phytoremediation techniques to waterlogged areas or contaminated wetlands can expand its reach to ecosystems that are currently difficult to restore. Developing plant species that thrive in diverse environmental conditions—such as those that can tolerate varying moisture levels—will be crucial for broadening the scope of phytoremediation beyond traditional land-based applications [

76]. These efforts could provide innovative solutions for ecosystems that face unique challenges beyond the capacity of conventional methods.

8. Conclusions

Phytoremediation offers a sustainable and cost-effective approach to addressing soil contamination, particularly in environments impacted by both PHs and heavy metals. This review has outlined the key mechanisms involved in phytoremediation, the challenges posed by multi-polluted soils, and emerging strategies to improve its efficiency. Although significant advancements have been made in understanding the interactions between pollutants, plants, and soil microorganisms, challenges such as unpredictable pollutant behavior and disruptions to soil biota persist. To address these issues, future efforts should prioritize enhancing plant resilience through genetic engineering, optimizing pollutant uptake, and improving plant-microbe interactions. The integration of biological products with soil amendments, as well as the application of advanced biotechnological interventions, shows great potential for enhancing pollutant removal and accelerating soil restoration. Ultimately, the success of phytoremediation in practical applications hinges on interdisciplinary collaboration, continued innovation, and a commitment to field-based research. By embracing new technologies and refining existing strategies, phytoremediation can play a pivotal role in mitigating the pressing issue of soil contamination in the future.

Author contribution

Yun-Yeong Lee: Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Kyung-Suk Cho: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. Jeonghee Yun: Visualization, Validation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government, the Ministry of Science, and ICT (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C2006615 & RS2023-00217228).

Data availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Blum, W.E.H. Functions of soil for society and the environment. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2005, 4, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, S.; Khan, I.; Meng, K.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, C. A review on remediation technologies for dense metals polluted soil. Cent Asian J Environ Sci Technol Innov 2020, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.G.S.; de Almeida, F.C.G.; da Rocha e Silva, N.M.P.; Casazza, A.A.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Soil bioremediation: overview of technologies and trends. Energies 2020, 13, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Dai, Z.; Ma, B.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Xu, J. Environmental interactions and remediation strategies for co-occurring pollutants in soil-A review. Earth Critical Zone 2024, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghlimi, M.; Baghdad, B.; Hadi, H. El; Bouabdli, A. Phytoremediation mechanisms of heavy metal contaminated soils: A review. Open J Ecol 2015, 5, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossai, I.C.; Ahmed, A.; Hassan, A.; Hamid, F.S. Remediation of soil and water contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbon: A review. Environ Technol Innov 2020, 17, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajabbasi, M.A. Importance of soil physical characteristics for petroleum hydrocarbons phytoremediation: a review. Afr J Environ Sci Tech 2016, 10, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, S.R.; Karthik, C.; Kadirvelu, K.; Arulselvi, P.I.; Shanmugasundaram, T.; Bruno, B.; Rajkumar, M. Understanding the molecular mechanisms for the enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metals through plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: A review. J Environ Manage 2020, 254, 109779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Song, X.; Ding, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Z. Bioremediation of PAHs and heavy metals co-contaminated soils: Challenges and enhancement strategies. Environ Pollut 2022, 295, 118686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirakkara, R.A.; Cameselle, C.; Reddy, K.R. Assessing the applicability of phytoremediation of soils with mixed organic and heavy metal contaminants. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2016, 15, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Zeng, G.; Wu, H.; Zhang, C.; Liang, J.; Dai, J.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, W.; Wan, J.; Xy, P.; et al. Co-occurrence and interactions of pollutants, and their impacts on soil remediation—A review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 2017, 47, 1528–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhuo, R. Recent advances in phyto-combined remediation of heavy metal pollution in soil. Biotechnol Adv 2024, 72, 108337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aghajani Delavar, M. Techno-economic analysis of phytoremediation: A strategic rethinking. Sci Total Environ 2023, 902, 165949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, F.U.; Ejaz, M.; Cheema, S.A.; Khan, M.I.; Zhao, B.; Liqun, C.; Salim, M.A.; Naveed, M.; Khan, N.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; et al. Phytotoxicity of petroleum hydrocarbons: Sources, impacts and remediation strategies. Environ Res 2021, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, V.S.; Sharma, A.; Srivastav, A.L.; Rani, L. Phytoremediation of toxic metals present in soil and water environment: A critical review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 44835–44860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, F.; Hijri, M.; St-Arnaud, M. Overview of approaches to improve rhizoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils. Appl Microbiol 2021, 1, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.E. Phytoremediation and its mechanisms: A review. Int J Environ Bioenergy 2012, 2, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, S.G.; Branch, B.; Seghatoleslami, M.J. Phytoremediation: A teview. Adv Agric Biol 2021, 1, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Dai, M.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Tan, X.; Peng, C.; Ali, I.; Naz, I. A critical review on the phytoremediation of heavy metals from environment: Performance and challenges. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, S.H.; Hadibarata, T. Removal of heavy metals in contaminated soil by phytoremediation mechanism: A review. Water Air Soil Pollut 2020, 231, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Kiran, N.S.; Romanholo Ferreira, L.F.; Yadav, K.K.; Mulla, S.I. New insights into the bioremediation of petroleum contaminants: A systematic review. Chemosphere 2023, 326, 138391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, I.; Puschenreiter, M.; Gerhard, S.; Schöftner, P.; Yousaf, S.; Wang, A.; Syed, J.H.; Reichenauer, T.G. Rhizoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils: Improvement opportunities and field applications. Environ Exp Bot 2018, 147, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekta, P.; Modi, N.R. A review of phytoremediation. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2018, 7, 1485–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Li, J.; Xie, H.; Yu, C. Review on remediation technologies of soil contaminated by heavy metals. Procedia Environ Sci 2012, 16, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W.; Cao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xian, Q. The effects of Cu-phenanthrene co-contamination on adsorption-desorption behaviors of phenanthrene in soils. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Li, L.Y.; Grace, J.R. Effect of organic matter and selected heavy metals on sorption of acenaphthene, fluorene and fluoranthene onto various clays and clay minerals. Environ Earth Sci 2018, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lv, J.; Luo, L.; Yang, K.; Lin, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S. Arsenate and cadmium co-adsorption and co-precipitation on goethite. J Hazard Mater 2013, 262, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yang, J.; Lou, L.; Zhu, L. Solubilization properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by saponin, a plant-derived biosurfactant. Environ Pollut 2011, 159, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Usman, A.R.A.; El-Naggar, A.H.; Aly, A.A.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Elmaghraby, S.; Al-Omran, A. Conocarpus biochar as a soil amendment for reducing heavy metal availability and uptake by maize plants. Saudi J Biol Sci 2015, 22, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciandaro, G.; Macci, C.; Peruzzi, E.; Ceccanti, B.; Doni, S. Organic matter-microorganism-plant in soil bioremediation: A synergic approach. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2013, 12, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Cui, X.; Xie, M.; Zhao, R.; Xu, L.; Ni, S.; Cui, Z. Amendments and bioaugmentation enhanced phytoremediation and micro-ecology for PAHs and heavy metals co-contaminated soils. J Hazard Mater 2022, 426, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y. Immobilization and accumulation by maize grown in a multiple-metal-contaminated soil and their potential for safe crop production. Toxics 2020, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.S.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Song, Y.; Ahmed, R.; Rehman, A.; Arif, M.; Irshad, S.; Cheema, A.I. Efficacy of rice husk biochar and compost amendments on the translocation, bioavailability, and heavy metals speciation in contaminated soil: Role of free radical production in maize (Zea mays L.). J Clean Prod 2022, 330, 129805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedt, M.; Schäffer, A.; Smith, K.E.C.; Nabel, M.; Roß-Nickoll, M.; van Dongen, J.T. Comparing straw, compost, and biochar regarding their suitability as agricultural soil amendments to affect soil structure, nutrient leaching, microbial communities, and the fate of pesticides. Sci Total Environ 2021, 751, 141607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwankwegu, A.S.; Onwosi, C.O.; Orji, M.U.; Anaukwu, C.G.; Okafor, U.C.; Azi, F.; Martins, P.E. Reclamation of DPK hydrocarbon polluted agricultural soil using a selected bulking agent. J Environ Manage 2016, 172, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruley, J.A.; Amoding, A.; Tumuhairwe, J.B.; Basamba, T.A.; Opolot, E.; Oryem-Origa, H. Enhancing the phytoremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils in the sudd wetlands, South Sudan, using organic manure. Appl Environ Soil Sci 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, B.; Kádár, I.; Bíró, B.; Rajkai-Végh, K.; Ragályi, P.; Rékási, M.; Márton, L. Phytoremediation: enhanced cadmium (Cd) accumulation by organic manuring, EDTA and microbial inoculants (Azotobacter sp., Pseudomonas sp.) in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.). Acta Agron Hung 2011, 59, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xi, M.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X.; Bai, Z.; Huang, Y. Effects of IDSA, EDDS and EDTA on heavy metals accumulation in hydroponically grown maize (Zea mays L.). J Hazard Mater 2010, 181, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Shinde, A.; Aeron, V.; Verma, A.; Arif, N.S. Genetic engineering of plants for phytoremediation: Advances and challenges. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol 2023, 32, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Heng, S.; Munis, M.F.H.; Fahad, S.; Yang, X. Phytoremediation of heavy metals assisted by plant growth promoting (PGP) bacteria: A review. Environ Exp Bot 2015, 117, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.R.A.; Yin, Q.; Oliveira, R.S.; Silva, E.F.; Novo, L.A.B. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils: Current knowledge and future directions. Sci Total Environ 2022, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, E.; Avcı, T. Screening and molecular identification of biosurfactant/bioemulsifier producing bacteria from crude oil contaminated soils samples. Biologia 2023, 78, 2179–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Niu, X.; Zhou, B.; Xiao, Y.; Zou, H. Application of biochar-immobilized Bacillus sp. KSB7 to enhance the phytoremediation of PAHs and heavy metals in a coking plant. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, E.; Agazzi, G.; Rolli, E.; Borin, S.; Marasco, R.; Chiaberge, S.; Conte, A.; Filtri, P.; Pedron, F.; Rosellini, I.; et al. Exploiting hydrocarbon-degrading indigenous bacteria for bioremediation and phytoremediation of a multicontaminated soil. Chem Eng Technol 2016, 39, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, L.; Hu, X. Phytoremediation effect of Scirpus triqueter inoculated plant-growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) on different fractions of pyrene and Ni in co-contaminated soils. J Hazard Mater 2017, 325, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Su, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y. Effect of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria on phytoremediation efficiency of Scirpus triqueter in pyrene-Ni co-contaminated soils. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, Y.Y.; Cho, K.S. Effect of Novosphingobium Sp. CuT1 inoculation on the rhizoremediation of heavy metal- and diesel-contaminated soil planted with tall fescue. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 16612–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, A.C.; Bagard, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Esposito, G.; Huguenot, D. Comparative bioremediation of heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons co-contaminated soil by natural attenuation, phytoremediation, bioaugmentation and bioaugmentation-assisted phytoremediation. Sci Total Environ 2016, 563, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choden, D.; Pokethitiyook, P.; Poolpak, T.; Kruatrachue, M. Phytoremediation of soil co-contaminated with zinc and crude oil using Ocimum gratissimum (L.) in association with Pseudomonas putida MU02. Int J Phytoremediation 2021, 23, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Hu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, W.; Chen, Y. Pseudomonas aeruginosa improved the phytoremediation efficiency of ryegrass on nonylphenol-cadmium co-contaminated soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 28247–28258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Das, A.; Das, S.; Bhatawadekar, V.; Pandey, P.; Choure, K.; Damare, S.; Pandey, P. Petroleum hydrocarbon catabolic pathways as targets for metabolic engineering strategies for enhanced bioremediation of crude-oil-contaminated environments. Fermentation 2023, 9, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bano, A.; Singh, S.P.; Sharma, S.; Xia, C.; Nadda, A.K.; Lam, S.S.; Tong, Y.W. Engineered microbes as effective tools for the remediation of polyaromatic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borremans, B.; Hobman, J.L.; Provoost, A.; Brown, N.L.; Van Der Lelie, D. Cloning and functional analysis of the pbr lead resistance determinant of Ralstonia metallidurans CH34. J Bacteriol 2001, 183, 5651–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittins, J.R. Cloning of a copper resistance gene cluster from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by recombineering recovery. FEBS Lett 2015, 589, 1872–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.P.; Silver, S. A second gene in the Staphylococcus aureus cadA cadmium resistance determinant of plasmid p1258. J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 7636–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, F.; Yi, S.; Ge, F. Genetically engineered microbial remediation of soils co-contaminated by heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Advances and ecological risk assessment. J Environ Manage 2021, 296, 113185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshniyat, P. Isolation and cloning of mercuric reductase gene (merA) from mercury-resistant bacteria. Biol J Microorganism, 2018, 7, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Satyapal, G.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.S.; Prashant; Ranjan, R.K.; Kumar, K.; Jha, A.K.; Singh, N.P.; Haque, R.; et al. Cloning and functional characterization of arsenite oxidase (aoxB) gene associated with arsenic transformation in Pseudomonas sp. strain AK9. Gene 2023, 850, 146926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Bin; He, J.; Polle, A.; Rennenberg, H. Heavy metal accumulation and signal transduction in herbaceous and woody plants: Paving the way for enhancing phytoremediation efficiency. Biotechnol Adv 2016, 34, 1131–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Li, Q.B.; Lu, Y.H.; Sun, D.H.; Huang, Y.L.; Chen, X.R. Bioaccumulation of nickel from aqueous solutions by genetically engineered Escherichia coli. Water Res 2003, 37, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, V.H.; Ullah, I.; Dunwell, J.M.; Tibbett, M. Bioremediation potential of Cd by transgenic yeast expressing a metallothionein gene from Populus trichocarpa. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 202, 110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K.M.; Gatehouse, J.A.; Lindsay, W.P.; Shi, J.; Tommey, A.M.; Robinson, N.J. Expression of the pea metallothionein-like gene PsMTA in Escherichia coli and Arabidopsis thaliana and analysis of trace metal ion accumulation: implications for PsMTA function. Plant Molecular Biology 1992, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, P.; Zanella, L.; Proia, A.; De Paolis, A.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M.M.; Sanit Di Toppi, L.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. Cadmium tolerance and phytochelatin content of Arabidopsis seedlings over-expressing the phytochelatin synthase gene AtPCS1. J Exp Bot 2011, 62, 5509–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasic, K.; Korban, S.S. Transgenic Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) plants expressing an Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase (AtPCS1) exhibit enhanced As and Cd tolerance. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 64, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, S.; D’Souza, S.F. Prospects of genetic engineering of plants for phytoremediation of toxic metals. Biotechnol Adv 2005, 23, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, N.; Sumisa, F.; Shindo, K.; Kabumoto, H.; Arisawa, A.; Ikenaga, H.; Misawa, N. Comparison of two vectors for functional expression of a bacterial cytochrome P450 gene in Escherichia coli using CYP153 genes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2009, 73, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, A.; Baik, S.H.; Syutsubo, K.; Misawa, N.; Smits, T.H.M.; Van Beilen, J.B.; Harayama, S. Cloning and functional analysis of alkB genes in Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2. Environ Microbiol 2004, 6, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodate, M.; Kubota, M.; Misawa, N. Functional expression system for cytochrome P450 genes using the reductase domain of self-sufficient P450RhF from Rhodococcus sp. NCIMB 9784. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2006, 71, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, L.G.; Smits, T.H.M.; Labbé, D.; Witholt, B.; Greer, C.W.; Van Beilen, J.B. Gene cloning and characterization of multiple alkane hydroxylase systems in Rhodococcus strains Q15 and NRRL B-16531. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 5933–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kanany, F.N.; Othman, R.M. Cloning and expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkB gene in E. coli. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2020, 14, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Aleti, G.; Naidu, R.; Puschenreiter, M.; Mahmood, Q.; Rahman, M.M.; Wang, F.; Shaheen, S.; Syed, J.H.; Reichenauer, T.G. Microbe and plant assisted-remediation of organic xenobiotics and its enhancement by genetically modified organisms and recombinant technology: A review. Sci Total Environ 2018, 628–629, 1582–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, Z.; Yu, M.; Gruber, M.; Glick, B.R.; Zhou, R.; Hegedus, D.D. Inoculation of soil with plant growth promoting bacteria producing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase or expression of the corresponding acdS gene in transgenic plants increases salinity tolerance in Camelina sativa. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekuzarova, S.A.; Burdzieva, O.G.; Arkhireeva, I.G.; Dzobelova, L. V. Soil degradation and remediation. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng 2020, 913, 052054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils: recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. In Bioremediation for environmental sustainability; Saxena, G., Kumar, V., Shah, M.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bekuzarova, S.A.; Khatsaeva, F.M.; Tebieva, D.I.; Bekmurzov, A.D.; Kebalova, L.A.; Gobeev, M.A. Soil toxicity reduction by phytoindicators. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng 2021, 677, 042100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Masoodi, T.H.; Pala, N.A.; Murtaza, S.; Mugloo, J.A.; Sofi, P.A.; Zaman, M.U.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. Phytoremediation prospects for restoration of contamination in the natural ecosystems. Water 2023, 15, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommey, A.M.; Shi, J.; Lindsay, W.P.; Urwin, P.E.; Robinson, N.J. Expression of the pea gene PsMTA in E. coli metal-binding properties of the expressed protein. FEBS Letters 1991, 292, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).