It is well-known that mathematical modeling of physical phenomena represents an alternative approach, often advantageous in terms of time and resources, compared to experimental methods for studying complex systems. These problems, modeled through PDEs, depend on the input dataset, such as material physical properties, boundary conditions, and source terms. In many engineering applications, the correct boundary conditions that suit a target interior solution are found by a

try and fail approach with high computational costs. On the other hand, the optimal control approach aims to determine these parameters by minimizing a cost function that represents some target condition of the system [

1].

The use of optimal control theory requires the introduction of the inverse problem. The direct solution of the inverse problem, which allows rapid achievement of the goal and innovative solutions to the problem, can be carried out with the variational formulation of partial differential equations [

2]. With respect to direct simulations, the resolution of an optimal control problem requires solving the optimality system formed by state, adjoint, and control coupled systems. For this reason, several specialized codes in solving specific physics cannot implement directly the optimality control, although using a well-validated code would greatly increase the reliability of the optimization. The solution could be to keep this standalone code for solving the specialized physics and another one for the remaining part of the optimality system. The validated code, which solves for the state system, takes data from the control equation. For that reason, the two codes must be coupled.

In this paper, we present a simple temperature optimization achieved by coupling our in-house FEMuS code with the widely adopted OpenFOAM code. This coupling is facilitated through the use of the open-source MED and MEDCoupling libraries. The coupling is performed using MED libraries and ad=hoc routines added in the FEMuS and OpenFOAM codes [

3,

4]. Regarding optimal control problems involving different physics (FSI, turbulence modeling, boundary control with fractional operators, etc.) the interested reader can consult [

5,

6,

7] for details on the FEMuS code and [

8,

9] for the OpenFOAM code.

We demonstrate the accuracy, robustness, and performance of the proposed approach with an example targeting different objectives with distributed and boundary control for each case. In the first scenario, the control parameter corresponds to a volumetric heat source. In the second scenario, depending on whether the control is located, it can either be the wall temperature (Dirichlet type) or a heat flux (Neumann type). The paper is organized as follows. First, we describe the optimal control problem with distributed or boundary controls. After that, we recall the coupling algorithm between the employed CFD codes and the MED library as a supervisor. Finally, we present the numerical results obtained with the coupled and uncoupled algorithm in order to draw some conclusions.

1. Optimal Control Problem

The finite-volume framework, of which OpenFOAM is a prime example, is traditionally well-suited for flow applications of any kind. On the other hand, optimal control theory stems from the finite element framework and leverages many concepts that are naturally evaluated in that approach. In this section, we introduce the variational formulation of the optimal control problem to better understand what components are required for the implementation of an objective-oriented framework such as the one we display later in the paper. Each type of control is described considering the final equation system to be solved, and then the minimization algorithm is enforced by using a standard conjugate gradient method.

We recall some standard notation of functional spaces [

10]. Let

be a domain

, with

, or its boundary

, or a part of it. Also, let

be the standard Sobolev space of order

s. Naturally, we have

. We now consider a cost function, or functional, in the following form

where

is a generic

state variable subject to the control,

is the

target,

u is the

control parameter and

represents a penalty coefficient. With the latter parameter, the regularization term can increase or decrease the penalization by different weights on the functional. We underline that regularization terms that involve the derivative of the control variable are not considered in this paper. Naturally, the first term in (

1) represents the objective term or objective functional.

The control is performed on a steady-state temperature distribution without the convective term. Therefore, considering the gradient operator ∇ and the Laplacian operator

, the state equation to be satisfied by the temperature

is

where

represents the outward normal unit vector to the considered boundary,

is the thermal diffusivity,

Q the volumetric source term, and

and

are two suitable functions defined on

and

, respectively. The boundary

is split into two parts:

and

, with Neumann and Dirichlet boundary conditions applied. All the constraints of the problem are expressed in the

Lagrangian, an auxiliary function defined as

where

is the

Lagrangian multiplier or, in this case, the

adjoint temperature. Naturally, we denote by

the dot product.

For each type of control, the system of equations to be solved is derived, considering the state, the adjoint, and the control equation.

1.1. Distributed Control

The distributed control parameter is a volumetric heat source

Q. Therefore, the functional is written as

The adjoint problem is derived from the variational differentiation of the Lagrangian over the state variable. Thus, the equation for the adjoint temperature reads

where

is the Heaviside function that is equal to one only in the target region

. The adjoint equation is identical to the state formulation since we only consider the Laplacian operator. The right-hand side term is different from zero only in the target regions, as indicated by the Heaviside function.

The optimal control problem can be formulated as finding the minimum of the functional (

4), condition for which the variables are considered optimal. We denote the optimal solution with an overline. Thus the optimal control

must satisfy the Euler equation

where naturally

represents the Fréchet derivative of the functional

computed along the direction given by the control

Q. Thus, deriving the functional with respect to the control parameter

Q we obtain the following optimal control equation

The optimal control parameter

follows exactly the optimal adjoint temperature

with an opposite sign and scaled by the parameter

.

Although the Euler equation provides a definition of the optimal control variable, it is not sufficient for the numerical solution of the problem since it shows the behavior of the optimal solution of the optimization problem without any information on how to reach it. For most of the methods, the knowledge of the functional gradient is sufficient to calculate the direction for the functional minimization. For this reason, we consider the functional gradient

1.2. Neumann and Dirichlet Boundary Controls

For the Dirichlet boundary control, the control parameter is the imposed wall temperature

. Therefore, the state problem becomes

where

is the controlled boundary. Note that for the Dirichlet boundary case,

can be interpreted as the union of

and

. The functional is rewritten as

where the regularization term is calculated again in

. Note that, considering the temperature variable

, its boundary value should be theoretically sought in the fractional space

. On the other hand, since the computation of fractional operators is not straightforward, we assume to compute the regularization term considering a standard

-norm. In this way, we expand the solution space for the control variable, considering less regularized solutions.

Similarly to the distributed control, the adjoint problem and the control equation are obtained through the differentiation of the Lagrangian functional. Therefore, we have the system for the adjoint variable

Again, writing explicitly the Euler equation, it is possible to find an optimal control definition for the problem as

and the resulting functional gradient can be written as

For the Neumann boundary control, the control parameter is the heat flux

H imposed at the wall. Therefore, the state problem and the functional are redefined as follows.

where naturally now we have that

. Therefore, the functional reads as

Again, from the Lagrangian, the adjoint problem and the control equation can be derived and the adjoint system reads

From the Euler equation, the optimal control expression results

and the functional gradient becomes

1.3. Conjugate Gradient Method and Numerical Solution

To solve the stated problems numerically, we employ the

conjugate gradient (CG) method [

11]. This minimization technique belongs to the

gradient descent family, along with the more common

steepest gradient. These techniques are used for unconstrained optimization, where the control variable

q is sought in the entire control space

. The CG method approximates the optimal control

through a sequence

such that, given a solution

at the

n-th step, the solution at the following step is calculated using the formula

where the direction

is computed as

The parameter

is obtained such that the directions

and

are conjugate with respect to the Hessian matrix

, satisfying

and where

is constant, i.e. for a quadratic functional, we obtain the following expressions for

In order to make the computation easier, the formula (

22) can be rewritten with the

Fletcher-Reeves expression [

12]

that has been implemented in our numerical algorithm.

In (

23) bold symbols have been used for scalar variables. Nevertheless, for the conjugate gradient method, the vectors must be interpreted as numeric vectors, i.e., the collection of the variable values on the degrees of freedom of the computational grid. Therefore,

represents the numeric vector that contains this value for each node, or a suitable numeric vector of values based on the specific discretization technique adopted for the system.

The numerical algorithm used for the minimization problem can be described in a number of steps. Initially, the vectors of the state variable , the adjoint variable , and the control variable are initialized, along with the functional and the auxiliary variable , which represents the functional gradient at the previous iteration. For the first iteration of the time loop, the descent direction is initialized as the anti-gradient direction, similarly to the steepest gradient method.

After that, the time loop starts and the variables , , and the functional are updated. Naturally, the time loop must be interpreted as an iteration loop since our system is considered to be stationary. At this point, if the convergence conditions are not satisfied, the new search direction is found calculating the current functional and the parameter . Otherwise, if the convergence is reached, the while loop is terminated, and the number of iterations and the value of the functional are collected.

Algorithm 1 illustrates only the mathematical aspects of the application since the coupling algorithm between the codes is shown in the next section. Therefore, this scheme does not take into account which code solves a specific numerical field but shows the logical order to find the numerical solution considering the necessary steps of the minimization procedure.

|

Algorithm 1 - Optimal Control

|

- 1:

proceduremain() |

|

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

|

|

- 9:

while not stop do - 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

if convergence then - 15:

stop - 16:

end if - 17:

- 18:

- 19:

- 20:

- 21:

- 22:

end while - 23:

end procedure |

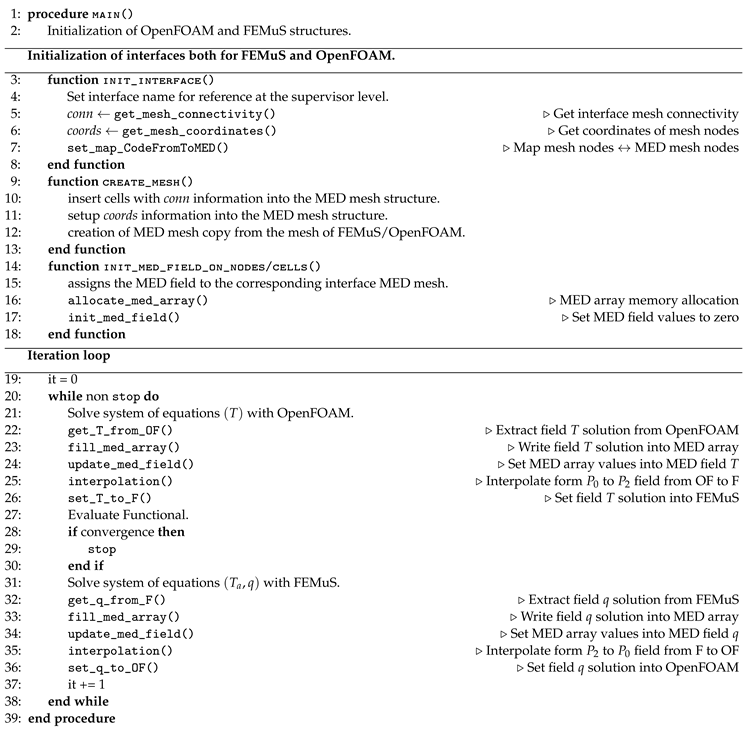

2. Coupling Algorithm

In this section, we briefly recall the algorithm for code coupling employed in this work, where an optimal control problem has been implemented considering two different numerical codes. The codes used in this work are FEMuS [

13] and OpenFOAM [

14], while the coupling interface has been built to exploit the MEDCoupling library [

15]. While the first two codes are used to manage CFD problems, the MEDCoupling library is a module of the SALOME platform that is developed by CEA (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives) and EDF (Électricité de France) to share data at the memory level, avoiding the use of external files. The interested reader can consult [

3] and reference therein for more details on the use of the library for coupling CFD codes.

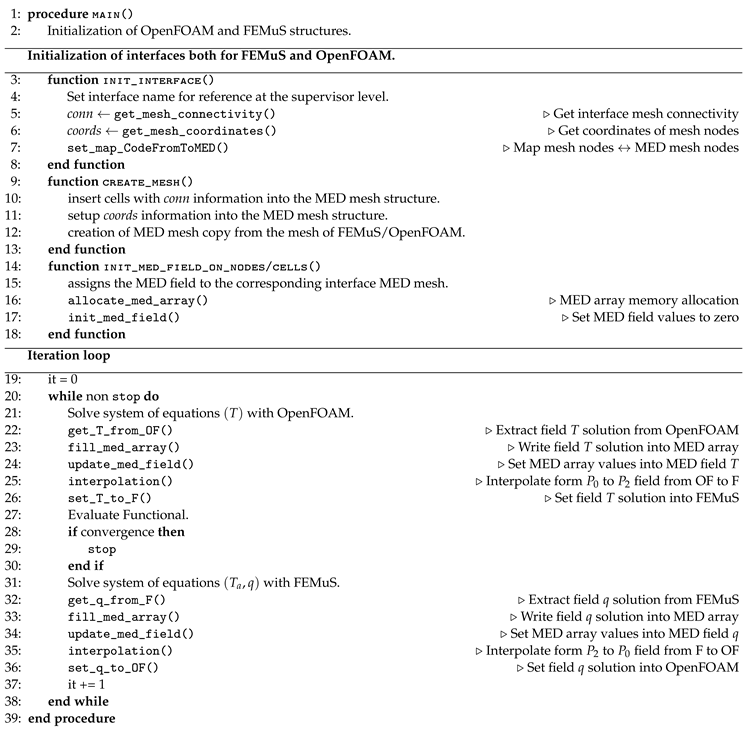

Having in mind the mathematical setting of an optimal control problem as explained in

Section 1, we briefly recall the coupling procedure between OpenFOAM and FEMuS in the optimal control context. The main idea presented in this work is to solve the state equation for the temperature field with OpenFOAM and the adjoint equation and the control

q with FEMuS. Data transfer between state and adjoint variables is achieved through a class interface based on specific MEDCoupling functions. Specifically, following the equations described in

Section 1, the state equation requires the evaluation of the control parameter

q solved by FEMuS. In particular, for a distributed control,

q is exchanged as a volumetric source for the temperature equation in OpenFOAM, while for the boundary control,

q is transferred as a boundary condition. For the purpose of this specific paper, we added the possibility to exchange a normal gradient boundary condition from FEMus to OpenFOAM, as requested by the Neumann boundary control formulation in (

14). A schematic representation of the coupling algorithm is presented in

Figure 1, where

and

denote the Dirichlet and Neumann boundaries, respectively.

We remark that, in the coupling between a finite volume and a finite element mesh, the interpolation between the two computational grids assumes a pivotal role. Therefore, for the temperature field T solved in OpenFOAM, we exploit a interpolation towards FEMuS, where with we denote the polynomial of order th that approximates a numerical field. On the other hand, having solved q after the conjugate gradient step, we apply a interpolation from FEMuS to OpenFOAM, in order to set the control q as the volumetric source/boundary condition for T.

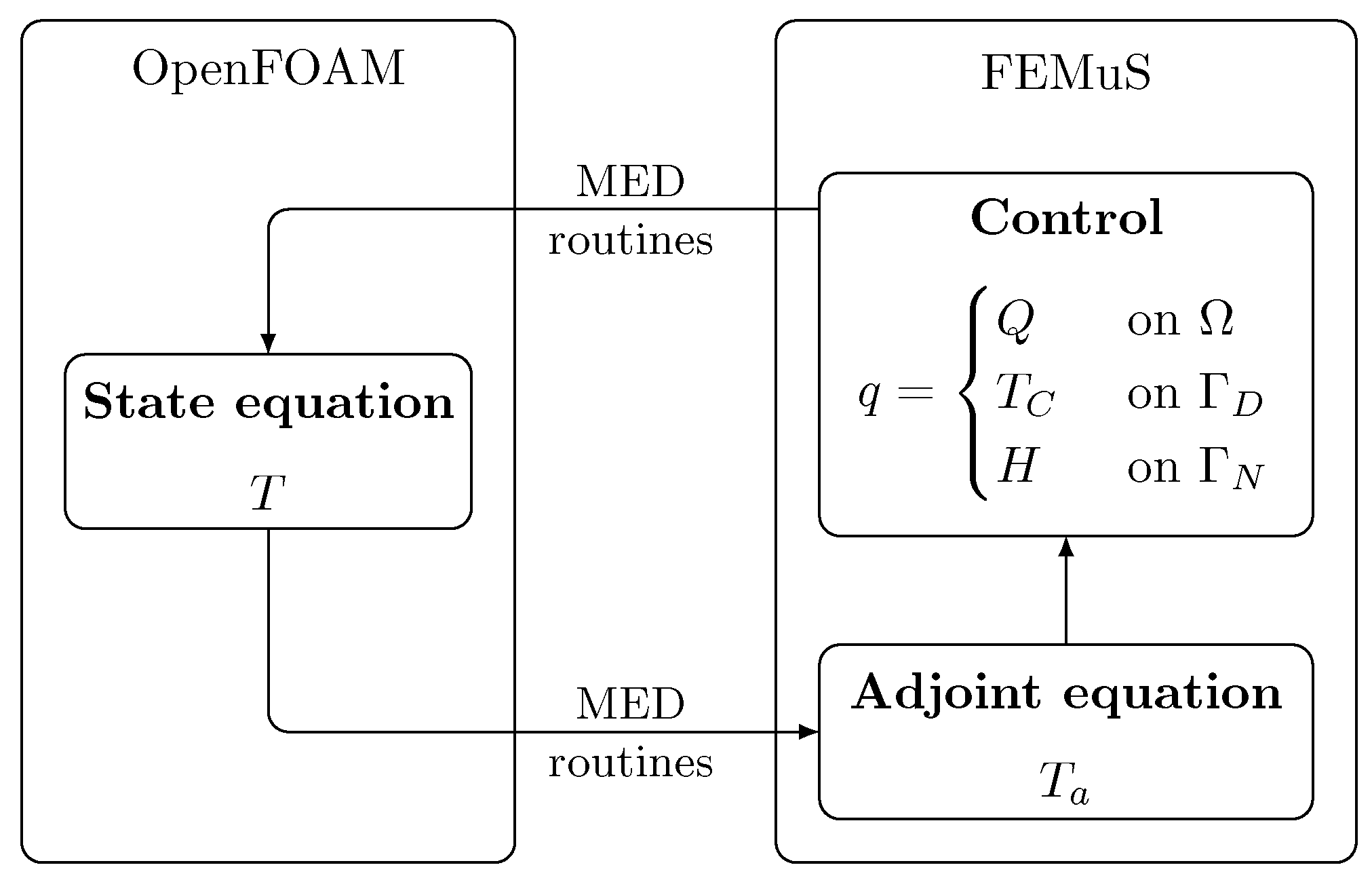

In Algorithm 2 we have reported a schematic overview of the coupling algorithm between FEMuS and OpenFOAM, including the routines employed. A brief description of each routine is reported on the right. The interested reader can find details in[

3].

The coupling algorithm can also be divided into two main steps. The first collects the routines useful for the initialization of the interface between the two codes. Then, we have the iteration loop with the data transfer between the two codes, including the convergence criterion. Regarding the first block, the information related to both meshes is taken into account with the routine init_interface(). In fact, a MED mesh copy for each mesh is built knowing the connectivity map and the coordinate point set (create_mesh()). After that, MED fields for all relevant variables in the exchange can be built on top of the MED meshes. Each field is populated by the source code to prepare the transfer to the target code. This step can be done considering a cell/node-wise initialization depending on the source field type.

The first step of the iteration loop is to solve the state variable

T in OpenFOAM and then extract its values. After that, these values, centered on cells, are interpolated into the biquadratic finite element mesh of FEMuS (

) and then stored in the corresponding data structure of the latter code. With this information, after the functional is evaluated, a convergence check is performed. Subsequently, the FEMuS code is equipped with all the information to solve its set of equations, i.e. the adjoint variable

and the control

q. The finite element solutions of these numerical fields are then interpolated from biquadratic FEM elements to piecewise value (

) in order to transfer these data into the OpenFOAM data structure. Naturally, only the control

q is transferred, using the routine

set_q_to_OF().

|

Algorithm 2 - Code Coupling

|

|

3. Numerical Results

In this section, we present some numerical results that outline the mathematical framework and numerical implementation described above. Specifically, we compare an optimal temperature control problem solved with two strategies. The first approach, which serves as a benchmark case, shows the results of the uncoupled case, i.e. only the FEMuS code is employed. The second approach exploits the coupling between FEMuS and OpenFOAM through the external library MEDCoupling for data transfer, as explained in

Section 2.

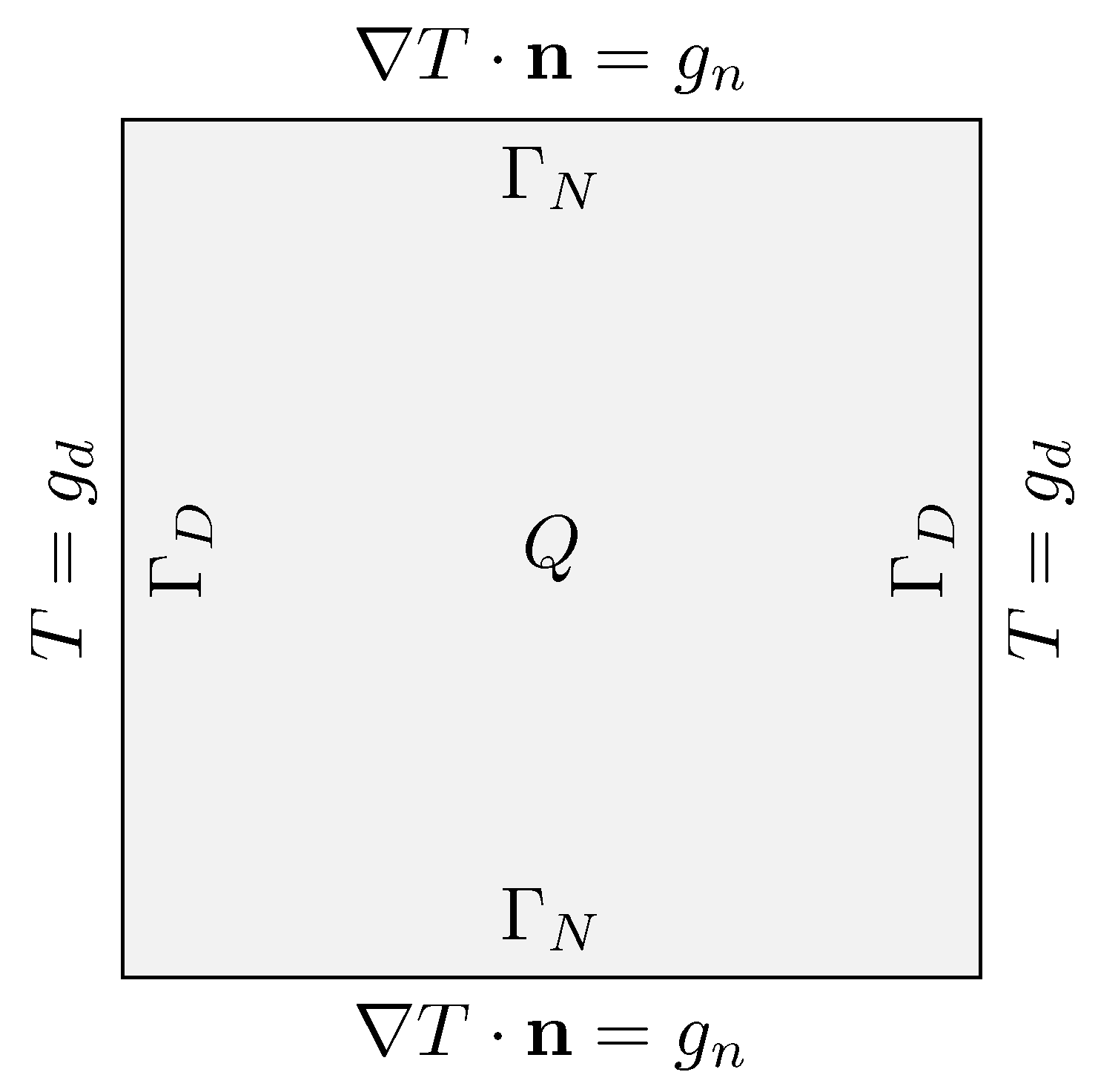

In both cases, we consider a square cavity as the problem domain, where a Poisson equation, i.e., the transport equation for the temperature field, is treated as the state equation and

and

represent boundaries with Dirichlet and Neumann conditions, respectively. The problem domain with the boundary conditions is reported in

Figure 3. In particular, the steady-state case with a null convective term has been implemented and solved, leading to a Laplacian term equal to a right-hand side term in the form

The source field Q and the boundary conditions are described according to the different types of optimal control approach in the following sections. The boundary conditions are considered constant in and , respectively. Boundary-type controls, which involve boundary conditions, are still initialized with or , so at each step, we impose at the boundary (or ) plus (or H), where the control variable is initialized to zero.

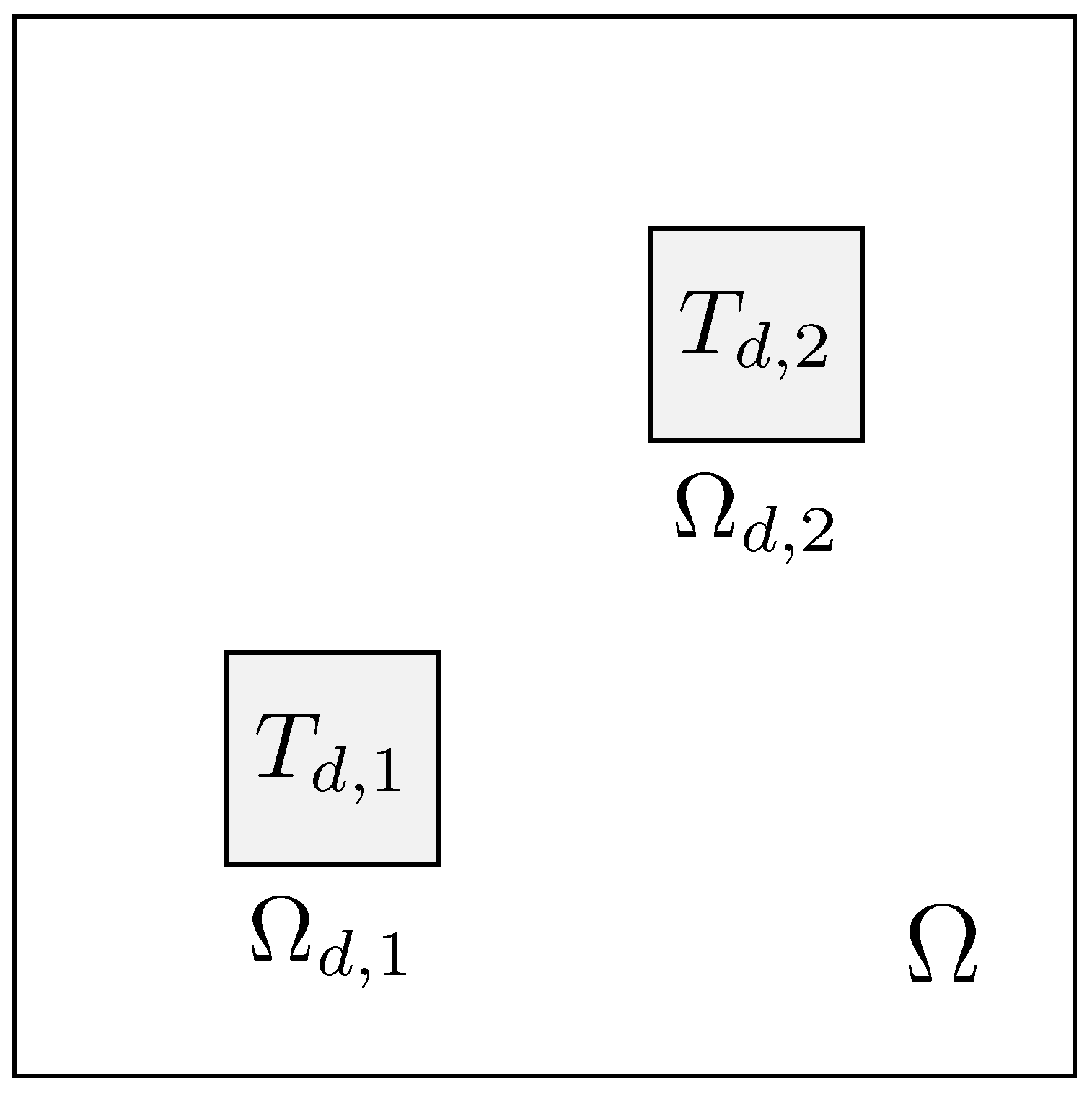

The objective functional, which relates the state variable

T with the desired temperature

, remains the same for each type of control. In particular, we have

where

is made up of two square subregions of the domain

. In

Figure 4, a schematic representation of the domain is depicted, where we have

, with

m. In addition, for the target regions, we have

and

with targets

and/or

, respectively.

For each simulation, we have considered .

Regarding the controlled regions, for each simulation, the regularization term is assumed to be solved on

. Therefore, the considered functional is

We recall that in the case of boundary control, the second integral on the right-hand side of (

26) has a meaning only on the controlled portion of the domain, which is a portion of

, thus on the Dirichlet boundaries or on the Neumann ones.

Moreover, for each type of control, the results obtained with the coupled and uncoupled algorithms have been compared. In particular, we have considered the same

,

, and the same criterion for the convergence. Specifically, considering the average functional of 10 iterations

at the iteration

i, the convergence has been obtained by

where

has been set equal to

. The average functional

has been used instead of

to avoid false exits due to local plateaus encountered during oscillations in conjugate gradient descent.

A dimensionless formulation for the optimal control system is proposed to better show results with different dimensions or physical constants. Thus, the dimensionless state variable

T, the dimensionless adjoint variable

and the dimensionless control

q are introduced as

where

. Therefore, in our case,

tends to

or 1 inside the controlled regions

and

, respectively. Similarly, the space coordinates

are adimensionalized via the the square domain side

L in

. In order for the optimal control system to remain coherent during the transition to these dimensionless variables, also the regularization factor

must be considered. Specifically, the following dimensionless transformations apply to the three types of control

In the following results, for the sake of simplicity, the parameter

will always be presented with its dimensional value, i.e., the value used in the simulations. However, its dimensionless value can be derived using formulas (

29), with

and

.

As mentioned in

Section 2, one of the main issues related to the coupling of different codes is the interpolation of the numerical fields between two different computational grids. Therefore, it is important to take into account this aspect when we compare the numerical results between an uncoupled and a coupled algorithm. If we consider the temperature field obtained through the interpolation between the finite volume and the finite element grid, thus into FEMuS data structures, we should rewrite the functional in the case of the coupled algorithm. Therefore, considering the interpolator

we have

where the control

is obtained from the adjoint equation computed with the interpolated temperature, i.e.

It is easy to understand that we have two different effects from the interpolation routine on the system of equations. The first interpolation acts directly on the functional, since we compute, in the FEM grid, the distance from the target temperature considering directly the interpolated temperature. The second interpolation, which indirectly arises from the control

, is evaluated considering a different equation for the adjoint variable. In fact, the effect of the interpolation can be seen on the right-hand side of (

31), even if the Laplacian operator on the left-hand side acts as a smoother function, thus the error coming from the interpolation is lower. Naturally, we should also consider the interpolation error coming from the data transfer in the opposite direction, i.e. from FEMuS to OpenFOAM.

Regarding the computational grids employed for the coupling algorithm, we set to have the same number of degrees of freedom between the two codes. For this reason, to clarify the notation when the size of a grid is built with even numbers, e.g., , we refer to the finite element grid, where these numbers represent the elements’ number . As a result, the corresponding FV grid size is represented by odd numbers, such as . Indeed, we recall that, considering biquadratic elements for finite element grids, its degrees of freedom are equal to when considering a square domain with a structured quadrilateral mesh.

3.1. Distributed Control

In this section, we report the numerical results related to the distributed control, with both numerical methods, i.e. the coupled and uncoupled algorithm. We recall that for the distributed case, the control q acts as the volumetric source on the right-hand side of the temperature equation, i.e., Q. Regarding the boundary conditions, we have homogeneous Dirichlet and Neumann boundary conditions on and , respectively.

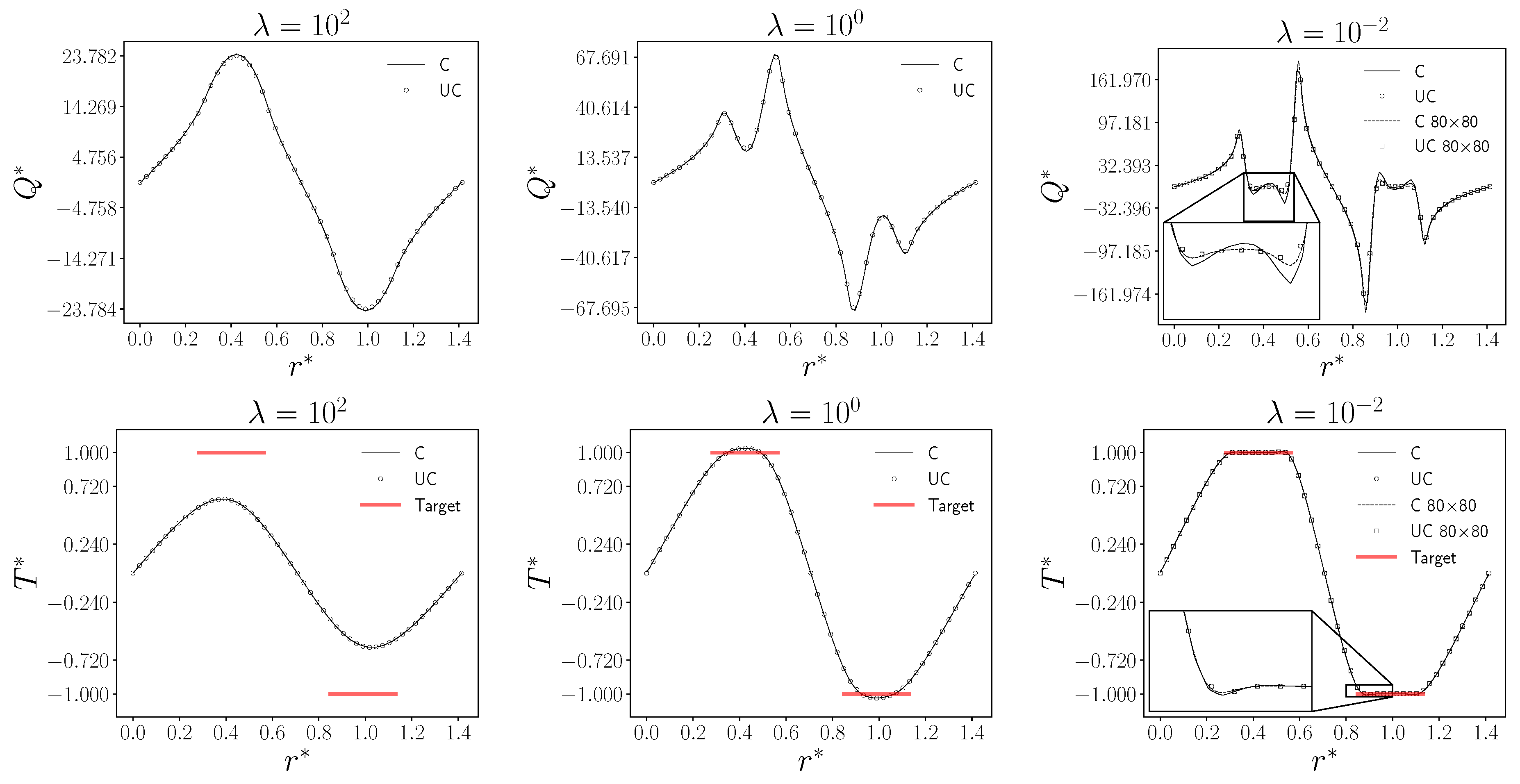

In

Figure 5 the control

and the non-dimensional state variable

are reported considering different values of the parameter

, from

to

. In particular, the plots show the variables as a function of the dimensionless length

, which corresponds to the diagonal of the domain (from the lower left corner to the upper right corner), with a value ranging from 0 to

. The coordinate

allows us to evaluate the state and the control variable in both controlled regions. In the following, we denote by

UC the uncoupled results (circular marker), while with the label

C the coupled codes results (solid line). The target value

is represented with the solid line (red).

In

Figure 5 we show the different behavior of the control parameter

Q with different values of

and the corresponding effect on the state variable in the controlled regions. As

decreases, the control

becomes less smooth and produces a sharp behavior near the controlled regions, as expected. In fact, the case with

represents the less regularized solution, with corresponding temperatures in the controlled region very close to the target value. Otherwise, with a

the control

has a low effect on the state variable that cannot reach the target value in the controlled regions.

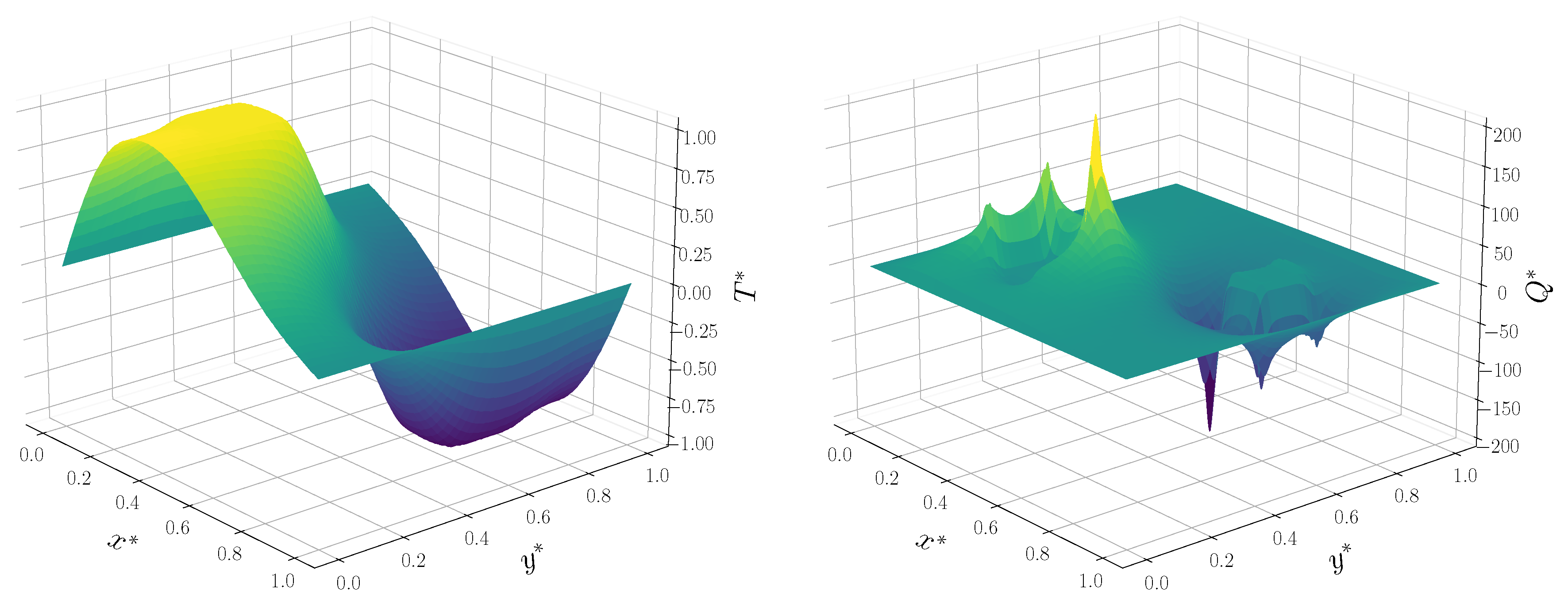

In

Figure 6, a surface plot of the non-dimensional temperature and the non-dimensional control over the whole domain is reported. Specifically, we display only the case with the lowest

, considering a

finite element grid. The symmetric behavior of these variables is shown. Moreover, a sharp trend of

is present near the target regions, where several peaks can be observed. Regarding the temperature field, as expected, two plateaus are present in the target regions, with opposite values close to 1 and

.

Table 1 reports the functional value and the number of iterations for the three different cases previously presented. the table lets us understand better the numerical results depicted in

Figure 5. Indeed, for different

cases, the first column represents the minimum of the functional, while the second column reports the number of iterations needed to reach the convergence condition. The first row reports the results for the coupled case, while the second row represents the uncoupled scenario. We recall that these results refer to a computational FEM grid with

elements and a corresponding

grid for the FVM to have the same number of degrees of freedom. Regarding

, with larger

values, we get a good match for both algorithms, while a larger difference can be noted for the lowest value of

.

For , we observe some discrepancies between coupled and uncoupled results. This phenomenon can be explained by considering the errors introduced during field interpolation and data transferred from one code to the other. As the optimal state is approaching, the distance of the state from the desired temperature decreases, making the interpolation error on T, at first negligible, increasingly important. This interpolation error limits the achievement of the real optimum state since we are not able to obtain a sufficiently accurate control.

The interpolation error can be improved by increasing the number of degrees of freedom. In fact, in

Figure 5 on the right, we have also reported the same case of

obtained with a refined grid, with a dashed line for the coupled case and with square markers for the uncoupled one. For the uncoupled case, small differences can be noticed because the simulation has already found its optimum, but in the coupled approach, improvement can be obtained to stir

Q very close to the uncoupled results. These conclusions can be drawn from

Table 1, where the distance between the two minima decreases considering the refined solution. In addition, the relative errors between the functional minimum increase by decreasing the value of

, going from 1 to

. However, the latter value corresponding to the lowest

can be improved until around

with a refined grid.

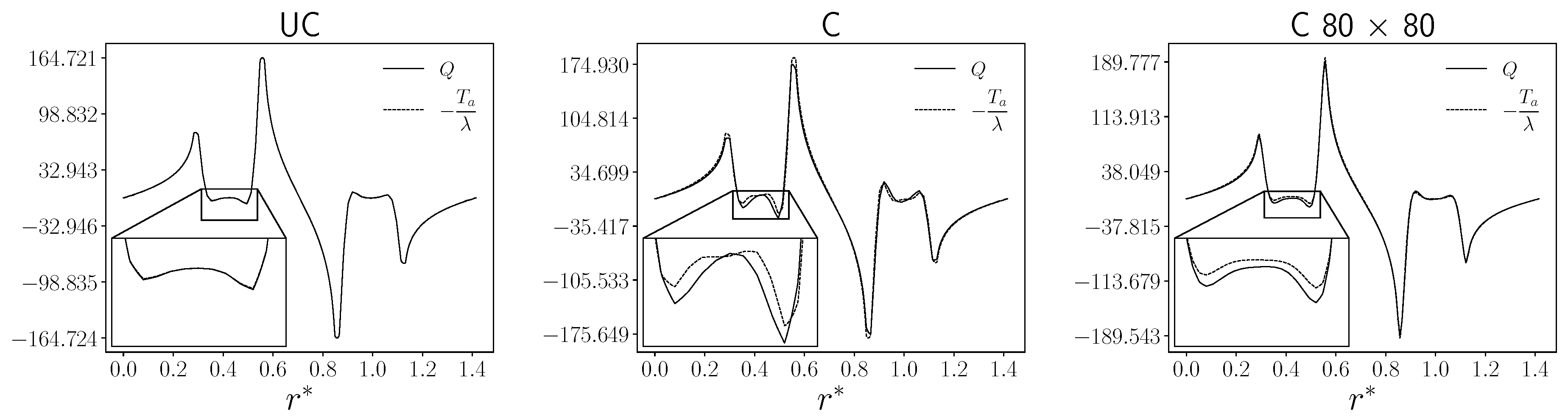

A measure of the quality of the optimization convergence can be obtained using the Euler expression defined in (

7). In

Figure 7 we compare the obtained control

Q with its analytic optimal expression

. We can notice that, for the uncoupled approach, there is a perfect agreement between the two lines, while some differences are present for the coupled case. As said before, we obtain better results considering the refined coupled approach, which is shown on the right. This analysis reflects the considerations made earlier about the functional minimum and validates the accuracy of the uncoupled simulation, which is used as a reference case.

The number of iterations is different between the two algorithms. Actually, this is true considering the first two values of where the coupled case needs more iterations to satisfy the convergence condition. For example, considering , we have an increase of almost one order of magnitude for the coupled case. However, this difference decreases when decreases since for the most controlled case, i.e., , the number of iterations is similar. In the last column, we report for the lowest the results for a refined case. Refining the grid, we notice that we reach a lower functional value while the number of iterations increases.

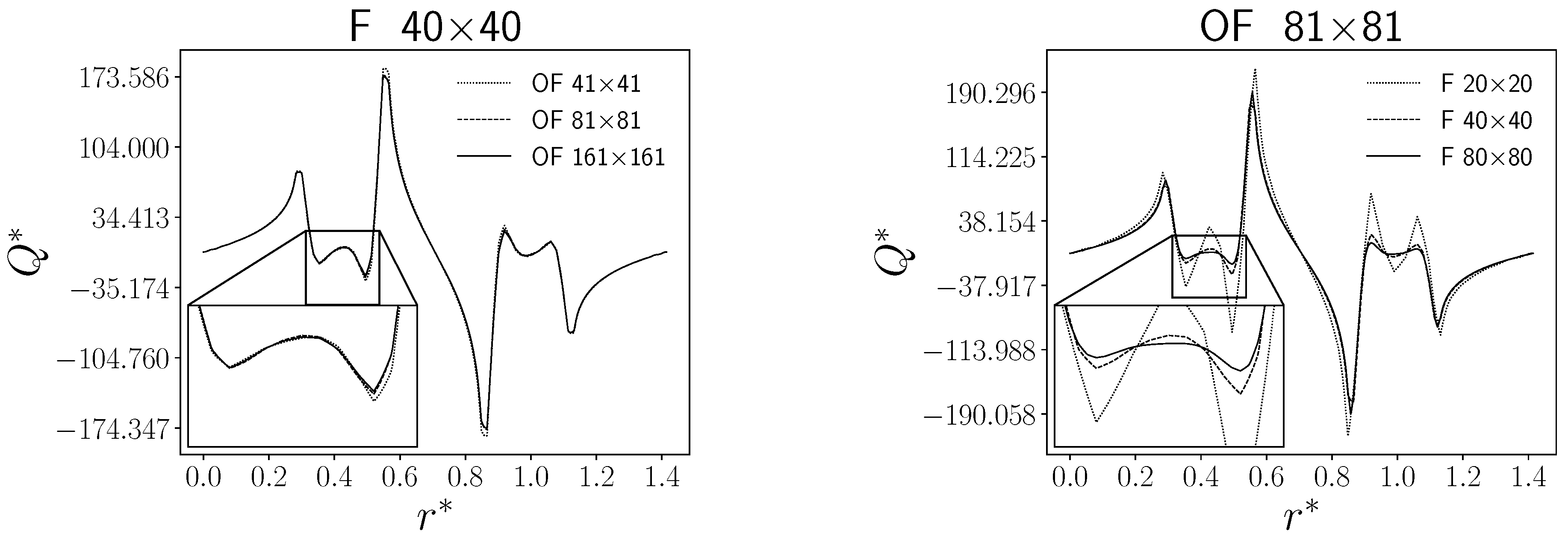

For the distributed case, we also investigate the influence of the difference between the degrees of freedom of the two meshes. This comparison aims to evaluate the impact of the MED-interpolating function on the overall behavior of the algorithm, especially for the shape of the control

. Therefore, we consider three different grids of the FVM code (OpenFOAM), by fixing the FEM computational grid with the same degree of freedom as the intermediate FVM grid. On the other hand, the same simulations have been performed considering a fixed FVM grid and varying the FEM one. The results have been reported in

Figure 8, where

F denotes the FEMuS grid and

OF the OpenFOAM grid. For these results, we have considered only the case with

, and the control

is reported as a function of the dimensionless diagonal coordinate

.

From

Figure 8, one can see the difference in the control

as a function of the computational grids. On the left, the change of the FVM grid seems to have a small influence on the solution of the equation systems. On the right side, the situation is different when considering the coarsest FEM grid, while for finer grids, the results are comparable with the picture on the left.

We deduce that, at least for this application, the OpenFOAM grid has much less influence compared to the FEMuS grid on the shape of the control. The interpolation error occurs when the projected field no longer provides a good approximation of the original one, i.e. when the target grid is not fine enough. Reconfirming the observations made earlier, this shows that the error occurs when the temperature field is projected from the grid to the of the FEMuS grid, so when the interpolation control is not sufficiently detailed the error becomes significant.

In

Table 2, we can confirm the effectiveness of grid refinement in the two codes: we have a much greater impact on the minimum of the functional by varying the FEMuS mesh compared to varying the OpenFOAM mesh. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the minimum number of iterations corresponds to the case where the two meshes have the same degrees of freedom.

3.2. Boundary Control

In this section, we report the boundary control cases, for two types of boundary conditions, Dirichlet and Neumann. The volumetric source of the state equation is equal to zero, leading to a Poisson equation for T. The boundary conditions correspond to the control q separately for the Dirichlet and the Neumann case, where the uncontrolled pair of boundaries stay homogeneous.

3.2.1. Dirichlet Boundary Control

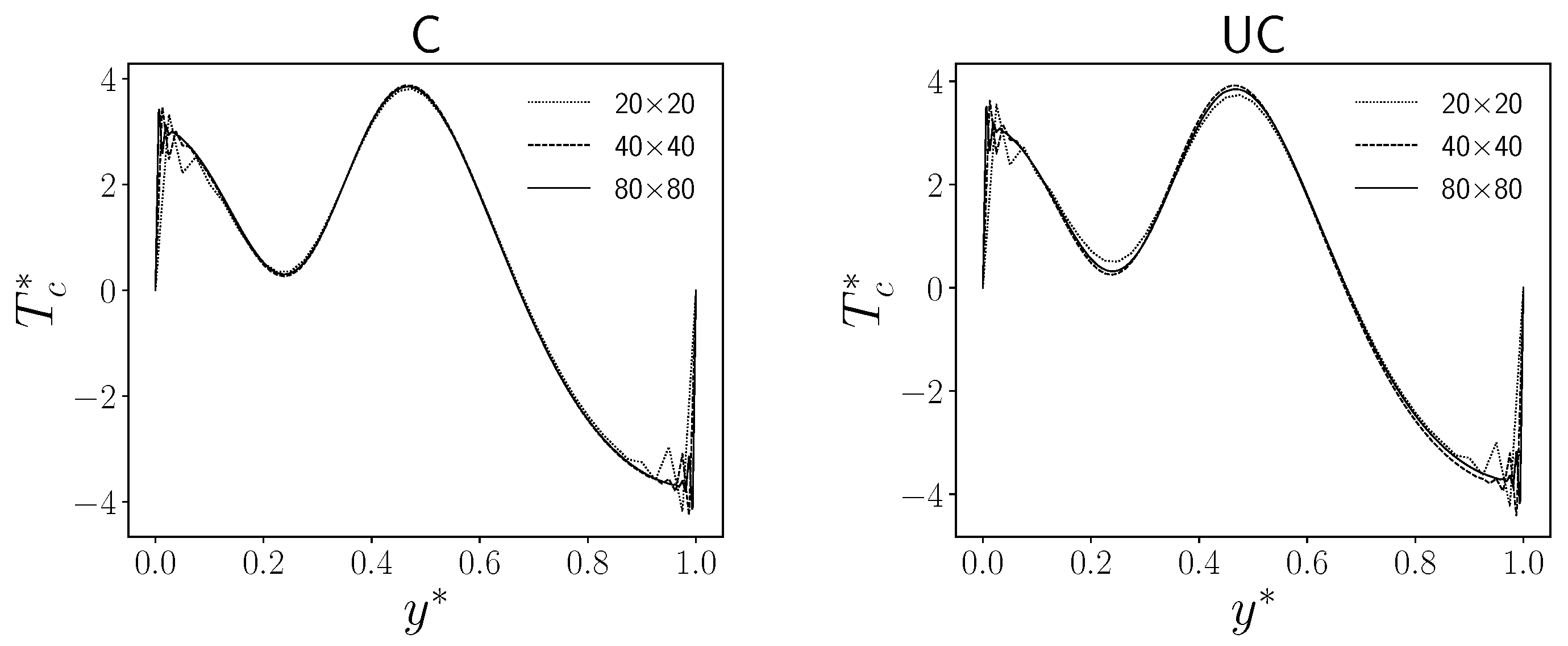

For the Dirichlet boundary control, we have also performed a standard grid convergence test to verify the goodness of the numerical results. In

Figure 9, on the left, the state variable

in the controlled domain, that is, the control parameter

q (

), which is imposed as a boundary condition, is reported. Since the simulation is symmetric with respect to the

y axes, we report only one boundary.

From

Figure 9, a good grid convergence can be seen for both algorithms, confirming the reliability of the numerical approach. In fact, the finest grid presents a solution that tends to be smooth also close to the boundary of the control region. The boundary of

, corresponding to the corner nodes of the domain, is the most problematic region due to

q being set to zero there.

In

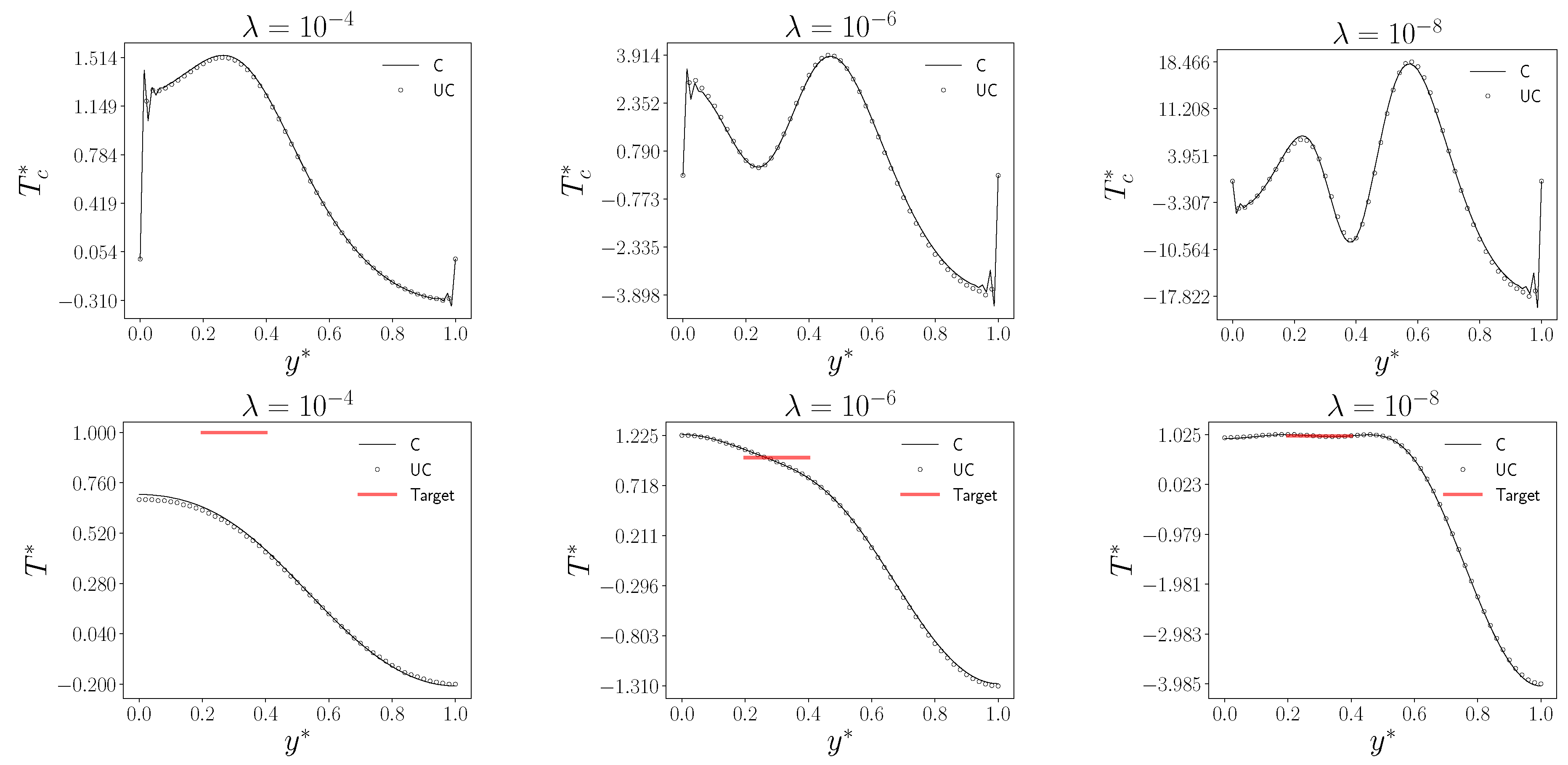

Figure 10, the control

and the state variable

have been reported for the Dirichlet boundary control for three values of

equal to

and

. The notation adopted in the graphs is the same of the distributed case. Since the results are symmetric with respect to the line

, the control is reported only for the left boundary, while for the state variable, the plot has been made considering the match with the target region

.

We can draw similar conclusions to those in the distributed case. Specifically, a good match with the temperature target value can be obtained with a low value of , which corresponds to the less regular trend of the control . For this case, it can be noticed a flat behavior of very close to 1, i.e. the red line, in correspondence with the controlled region . The distance with the target region is higher considering the case with , while with , the temperature is able to only intersect without reproducing its constant value in the entire region.

In

Table 3, the functional minimum and the number of iterations are reported for the Dirichlet boundary control. We can observe a better behavior of the coupled code with respect to the uncoupled case on both the minimum reached and the number of iterations. In any case, the differences between the two cases are minimal.

3.2.2. Neumann Boundary Control

We present now the numerical results obtained with the Neumann boundary control, following (

17). In this case, three values of

have been used to test the influence of the control

H on the state equation. In

Figure 11, the numerical results for the Neumann boundary control are reported with the considered

. Due to symmetry, we report only one of the two boundaries (the bottom one) for the control

H.

Similar comments of the previous cases are true for the Neumann boundary control as well. A good agreement between the state variable and the target temperature can be obtained only with small values of

since, for higher values of this parameter, the control

does not sufficiently influence the temperature

. This consideration is graphically represented in

Figure 11, where the variables are plotted as a function of the distance between the red line and the solutions for

. For low values of

, the major difference is present near the target region, whereas for the uncoupled control,

seems to be more flat with respect to the coupled result. Once again, we have reported the same case of

obtained with a refined grid, with a dashed line for the coupled case and with square markers for the uncoupled one. Similarly, as in the distributed case, we can observe that the coupled and uncoupled results become similar as the grid becomes finer. On the other hand, these differences do not influence the state temperature

, which is in perfect agreement with the desired value for both algorithms. Small differences can be noticed for

(far from the target region), where the uncoupled algorithm

reaches a lower value.

In

Table 4, the functional minimum value and the number of iterations for both algorithms are reported. For the lower case of

, which is the last column on the right, the results on a refined grid are also investigated. In this case, the number of iterations increases both in the coupled and in the uncoupled codes, decreasing the value of

. For high values of

, the functional minimum is similar in both algorithms, while the coupled case presents a higher number of iterations. A slightly different

can be seen for the lowest value of

. The case with

shows the same pattern as the distributed case above. For finer grids on the coupled code, we obtain a lower minimum of the functional with a higher number of iterations, while in the uncoupled case, the number of iterations decreases. With refined meshes, the difference between the values of the functional minimum decreases, confirming the improvement of the results considering finer computational grids. This similarity can be justified considering the fact that both distributed and Neumann cases share the same control expression based on the adjoint temperature. In fact, this behavior is not present in the Dirichlet control since the gradient of the adjoint temperature is used as the control parameter.

4. Conclusions

In this work, an optimal control problem has been presented considering the steady-state heat equation with a vanishing convective term. Specifically, the minimization problem has been solved with the adjoint equation, while the control parameter is handled with a standard conjugate gradient technique.

Moreover, we have compared the simulation results considering also a numerical code coupling between the finite element FEMuS code and the finite volume code OpenFOAM. In particular, while the state equation has been solved in OpenFOAM, the adjoint and the control are solved in FEMuS. The data transfer has been managed by the external library MEDCoupling, which is able to take the state variable T from OpenFOAM for the FEMuS adjoint equation. The inverse path is followed by the control variable Q, obtained from FEMuS and transferred to OpenFOAM as the RHS (distributed control) or as a boundary condition (boundary control).

The numerical results obtained with the coupling framework are compared with the ones resulting from the standalone FEMuS solution. For the three types of control problems, a good agreement between the numerical solutions of the two algorithms has been obtained. Regarding the interpolation error, some differences can be seen considering low values of since, for these cases, the result of the grid interpolation of T affects the control q, which is very sharp.

Extension to other systems of equations, from Navier-Stokes to turbulence modeling, will be studied in future work, with the purpose of searching boundary data that optimize multiphysics problems already validated in open-source codes such as OpenFOAM.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manzoni, A.; Quarteroni, A.; Salsa, S. Optimal control of partial differential equations; Springer, 2021.

- Gunzburger, M.D. Perspectives in flow control and optimization; SIAM, 2002.

- Barbi, G.; Cervone, A.; Giangolini, F.; Manservisi, S.; Sirotti, L. Numerical Coupling between a FEM Code and the FVM Code OpenFOAM Using the MED Library. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 3744. [CrossRef]

- Da Vià, R. Development of a computational platform for the simulation of low Prandtl number turbulent flows. PhD thesis, University of Bologna, 2019.

- Chirco, L. On the optimal control of steady fluid structure interaction systems. PhD thesis, University of Bologna, 2020.

- Giovacchini, V. Development of a numerical platform for the modeling and optimal control of liquid metal flows. PhD thesis, University of Bologna, 2022.

- Chierici, A. Mathematical and Numerical Models for Boundary Optimal Control Problems Applied to Fluid-Structure Interaction. PhD thesis, University of Bologna, 2021.

- Othmer, C. A continuous adjoint formulation for the computation of topological and surface sensitivities of ducted flows. International journal for numerical methods in fluids 2008, 58, 861–877. [CrossRef]

- Önder, A.; Meyers, J. Optimal control of a transitional jet using a continuous adjoint method. Computers & Fluids 2016, 126, 12–24.

- Adams, R.A.; Fournier, J.J. Sobolev spaces; Elsevier, 2003.

- Nazareth, J.L. Conjugate gradient method. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2009, 1, 348–353. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Reeves, C.M. Function minimization by conjugate gradients. The computer journal 1964, 7, 149–154. [CrossRef]

- Barbi, G.; Bornia, G.; Cerroni, D.; Cervone, A.; Chierici, A.; Chirco, L.; Viá, R.; Giovacchini, V.; Manservisi, S.; Scardovelli, R.; et al. FEMuS-Platform: A numerical platform for multiscale and multiphysics code coupling. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computational Methods for Coupled Problems in Science and Engineering, COUPLED PROBLEMS 2021. International Center for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 2021, pp. 1–12.

- Jasak, H. OpenFOAM: Open source CFD in research and industry. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2009, 1, 89–94.

- Ribes, A.; Caremoli, C. Salome platform component model for numerical simulation. In Proceedings of the 31st annual international computer software and applications conference (COMPSAC 2007). IEEE, 2007, Vol. 2, pp. 553–564.

Figure 1.

Coupled algorithm diagram.

Figure 1.

Coupled algorithm diagram.

Figure 2.

Coupled algorithm diagram.

Figure 2.

Coupled algorithm diagram.

Figure 3.

Temperature problem on the cavity.

Figure 3.

Temperature problem on the cavity.

Figure 4.

Domain problem with the target regions and .

Figure 4.

Domain problem with the target regions and .

Figure 5.

From left to right, control Q (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional diagonal , for a grid. On the right, the case with a grid is also reported.

Figure 5.

From left to right, control Q (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional diagonal , for a grid. On the right, the case with a grid is also reported.

Figure 6.

Dimensionless temperature (on the left) and (on the right).

Figure 6.

Dimensionless temperature (on the left) and (on the right).

Figure 7.

Optimal control Q and its analytic expression at the optimum state. Uncoupled case at the left, coupled case in the middle and the refined coupled case on the right.

Figure 7.

Optimal control Q and its analytic expression at the optimum state. Uncoupled case at the left, coupled case in the middle and the refined coupled case on the right.

Figure 8.

Control Q for different combinations of degrees of freedom between the two codes as a function of . On the left the FEM grid (F) is fixed, on the right the FVM grid (OF) is fixed.

Figure 8.

Control Q for different combinations of degrees of freedom between the two codes as a function of . On the left the FEM grid (F) is fixed, on the right the FVM grid (OF) is fixed.

Figure 9.

Grid convergence for the Dirichlet boundary control for for the coupled (left) and uncoupled (right) case. Non-dimensional temperature on the left controlled boundary for three different grid sizes.

Figure 9.

Grid convergence for the Dirichlet boundary control for for the coupled (left) and uncoupled (right) case. Non-dimensional temperature on the left controlled boundary for three different grid sizes.

Figure 10.

From left to right, control (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional coordinate respectively on the left wall for the control (at ) and in the middle of the target region 1 for the state variable (), for a grid.

Figure 10.

From left to right, control (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional coordinate respectively on the left wall for the control (at ) and in the middle of the target region 1 for the state variable (), for a grid.

Figure 11.

From left to right, control (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional coordinate respectively on the lower wall for (at ) and in the middle of the target region 1 for (), for a grid. For the case the results for a grid are also reported.

Figure 11.

From left to right, control (top) and temperature (bottom) for different as a function of the non-dimensional coordinate respectively on the lower wall for (at ) and in the middle of the target region 1 for (), for a grid. For the case the results for a grid are also reported.

Table 1.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the distributed control with both algorithms. In the last column, for the lowest value, the results for the refined grid are also reported.

Table 1.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the distributed control with both algorithms. In the last column, for the lowest value, the results for the refined grid are also reported.

|

|

|

(refined) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| UC |

|

6 |

|

4 |

|

|

Table 2.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the case varying the grid ratio of the two codes. In the first row, the FEMuS mesh is kept fixed (case A: F 40×40) and the OpenFOAM mesh is varied. In the second row, the opposite situation is reported (case B: OF 81×81).

Table 2.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the case varying the grid ratio of the two codes. In the first row, the FEMuS mesh is kept fixed (case A: F 40×40) and the OpenFOAM mesh is varied. In the second row, the opposite situation is reported (case B: OF 81×81).

| |

OF 41×41 |

OF 81×81 |

OF 161×161 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A |

3.30 |

4.4 |

3.24 |

2.1 |

3.22 |

2.9 |

| |

F 20×20 |

F 40×40 |

F 80×80 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B |

4.47 |

6.2 |

3.24 |

2.1 |

3.04 |

3.0 |

Table 3.

Minimum functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the Dirichlet boundary control with both algorithms for a grid.

Table 3.

Minimum functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the Dirichlet boundary control with both algorithms for a grid.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C |

|

9 |

|

5 |

|

|

| UC |

|

5 |

|

13 |

|

|

Table 4.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the Neumann boundary control with both algorithms for a grid. In the last column, for the lowest value, the results for the refined grid are also reported.

Table 4.

Minimum of the functional and number of iterations for the different cases of the Neumann boundary control with both algorithms for a grid. In the last column, for the lowest value, the results for the refined grid are also reported.

|

|

|

(refined) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| UC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).