3.1. Influence of the Lattice core on the Observed Wrinkle Length

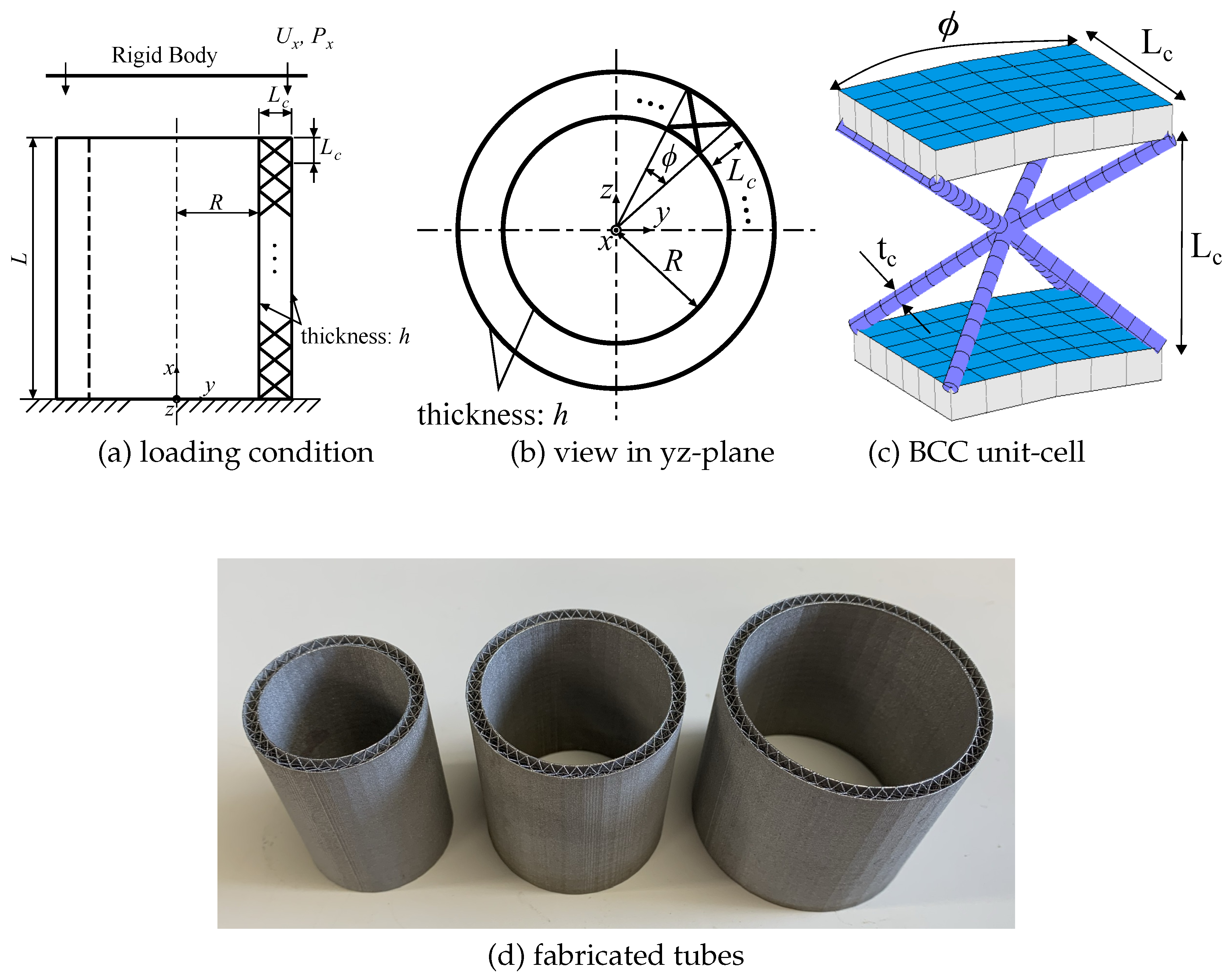

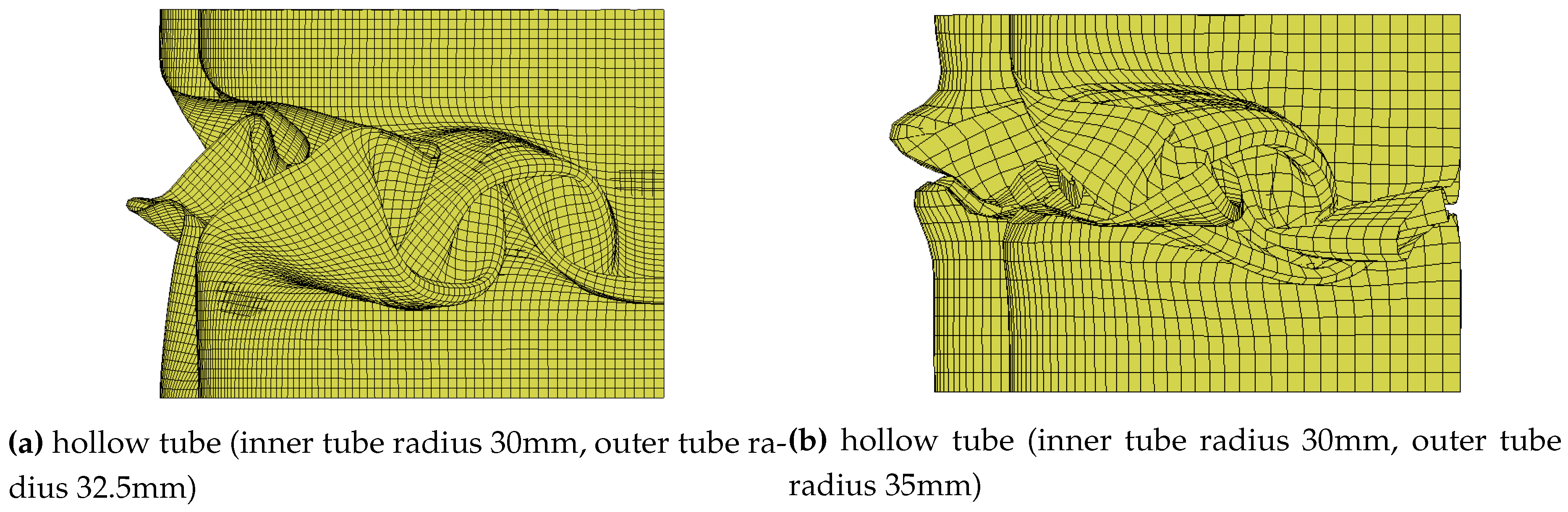

In this section, the influence of the lattice core sandwiched between the two tubes on the axial crushing behaviour of the cylindrical sandwich structure is discussed. Prior to this, we have also investigated the compressive response of thin-walled hollow tubes that consist of inner and outer circular tubes without a lattice core, and have evaluated the initial peak load

and the average load

and subsequently compared these values with analytical results in order to verify the effectiveness of our numerical simulation, as well as to clarify the role of the lattice core in the energy absorption process. Many papers have been published regarding the axial compressive response of thin-walled circular tubes, and some analytical equations have been proposed for estimating the initial peak load

and the average load

. Here, the peak load,

, corresponds to the initiation of local plastic bending near the fixed end. Also, the average load,

, is determined from the mean value of the compressive load up to the point at which half of the tube is crushed, namely,

For example, Chen et al. [

3] predicted the initial peak load

for a circular tube using an FE analysis, and showed that

can be written as:

Here, the parameters

and

depend on the material properties and tube geometry, and are given by:

Also, Wierzbicki [

35] proposed an empirical equation for the average load Pave as:

Table 2 shows the values of the peak load,

, and the average load,

, for two kinds of hollow tube under axial compression obtained by our FE analyses. Table 2 also includes the predictions derived from Eqs.(3) and (5). In the table, the numbers following the character R represent the radius values of the inner and outer tubes. For example, the model (

+

) consists of two tubes, in which the radius of the inner tube is 30mm, and that for the outer tube is 32.5mm. Regarding the predictions of the loads

and

, since each structure is composed of two tubes, two sets of

and

values can be calculated from the predictions (Eqs.(3) and (5)). We have summed them up and present the values in Table 2. It can be seen in Table 2 that their predictions agree reasonably well with the FE results, regardless of the combinations of tube radius

R.

Table 2.

Comparison of peak and average loads and obtained by FEM analysis and previously-proposed equations

Table 2.

Comparison of peak and average loads and obtained by FEM analysis and previously-proposed equations

| model |

[kN] |

[kN] |

| |

FEM |

Eq.(3) |

relative error[%] |

FEM |

Eq.(5) |

relative error[%] |

|

R30+R32.5 |

80.3 |

82.7 |

3.0 |

16.6 |

16.4 |

0.8 |

|

R30+R35 |

86.3 |

86.0 |

0.3 |

17.9 |

16.6 |

7.7 |

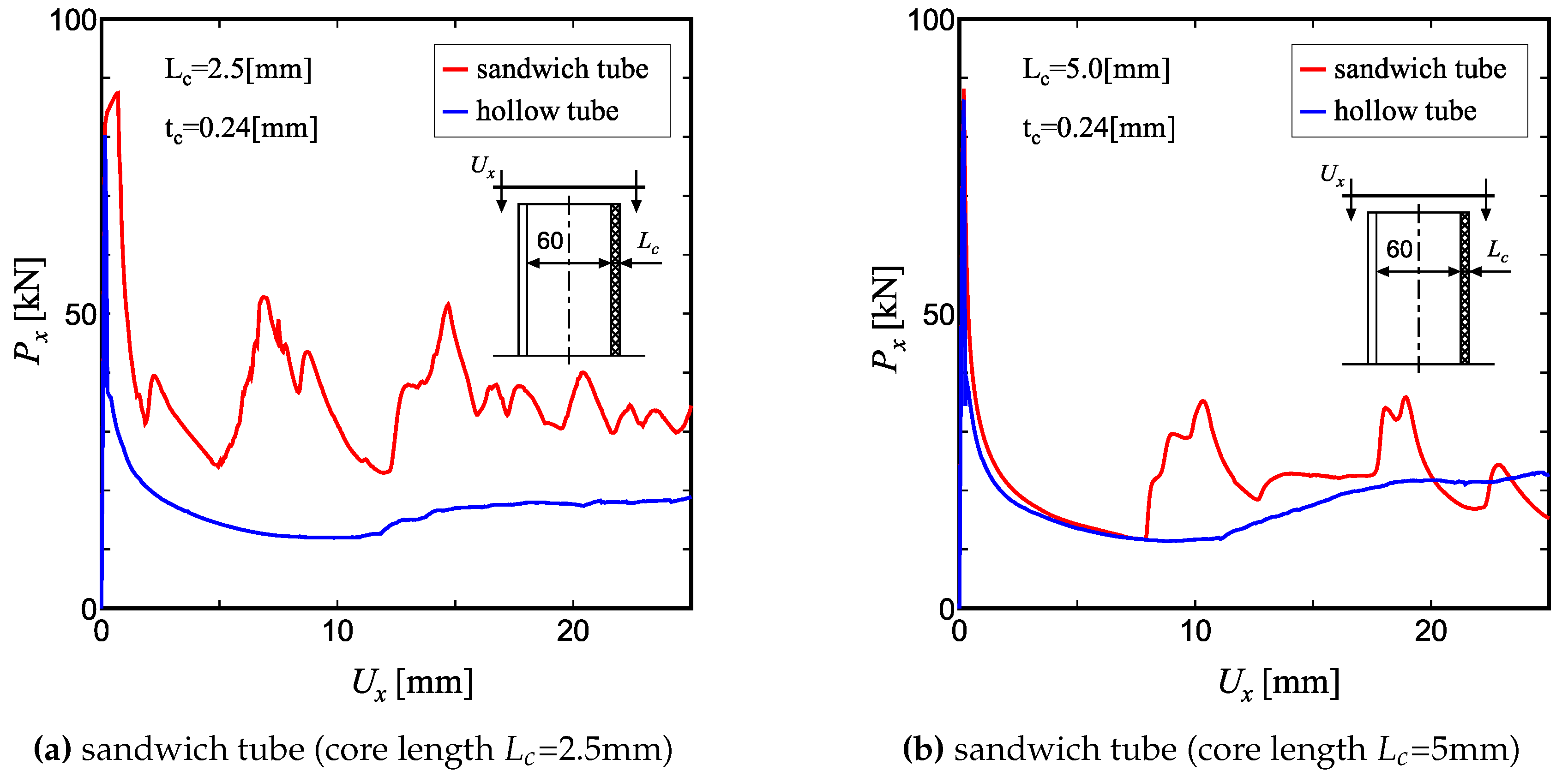

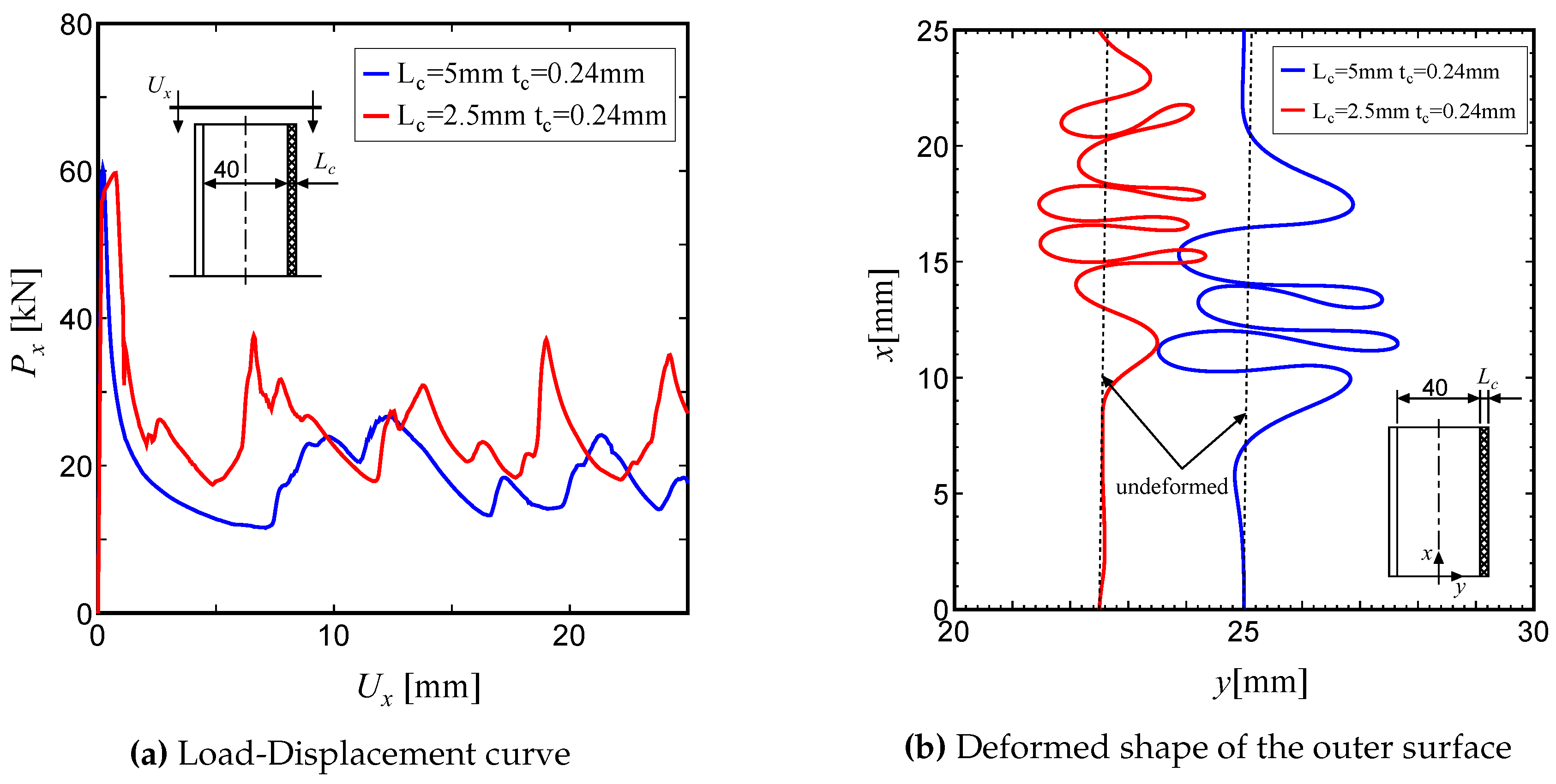

Figures 2 (a) and (b) show the variation of the axial compression load

for circular tubes with and without lattice cores. The results for the tubes with lattice cores are denoted by red curves, and those without lattice cores are shown by blue curves. Here, the inner diameter of the tube was set to a common value (60mm) for all tubes, and two values of outer diameter were employed in the FE model. The lattice core was introduced between the inner and outer shells. Here, two kinds of lattice core length, with

=2.5mm and 5.0mm were selected, and their contributions to the compressive load are discussed. These figures show how the lattice core affects the compressive load-carrying capacity, and also demonstrate that a finer lattice core is more effective for improving properties. It can be seen from these figures that the lattice core does not affect the initial peak load, but enhances the average load following the peak load. This is due to the fact that since the lattice core is softer than the surrounding cylindrical shell, the failure behaviour up to the peak load is independent of core geometry. It does, however, improve the folding behaviour of the wrinkles. As a result, the fluctuating load behaviour is enhanced and the load-carrying capacity is improved. This is especially the case when the core thickness

=2.5mm, where the contribution becomes significant.

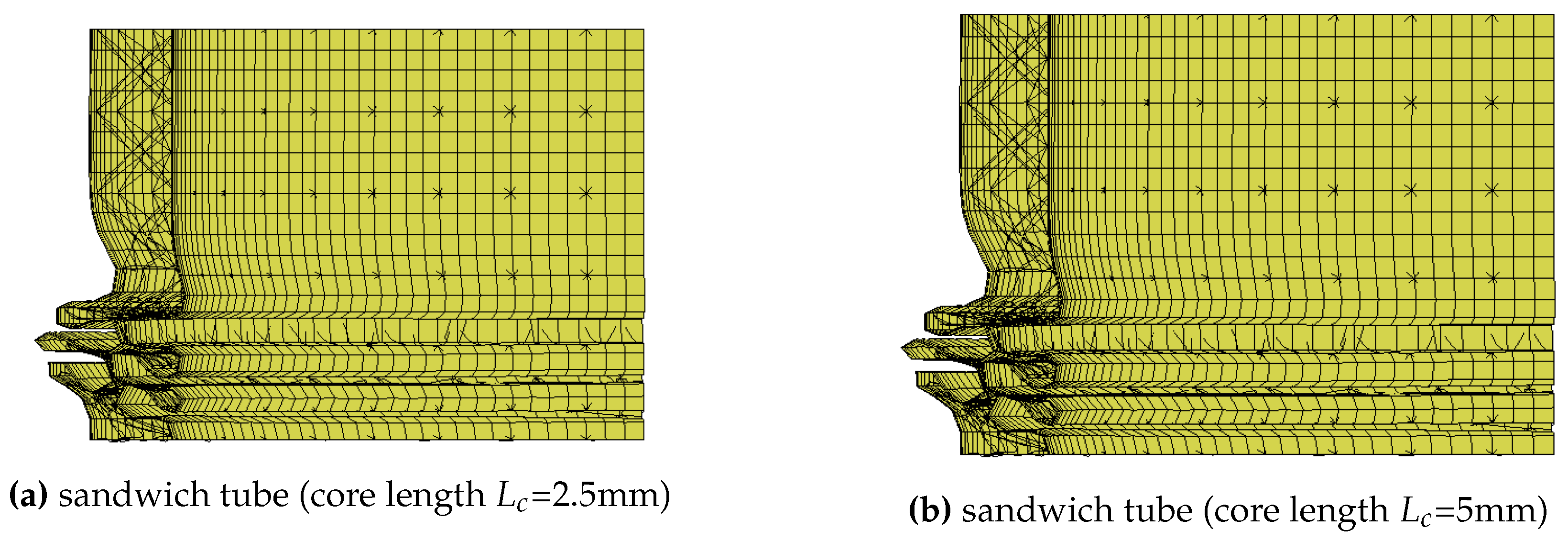

Figure 3(a) and (b) compare the deformed shapes of tubes based on different core sizes (

=2.5mm and 5.0mm) subjected to an axial displacement

=0.5. For comparison, the deformed shapes of a double tube without a lattice core is also shown in

Figure 4(a) and (b). It is evident from these figures that the wrinkle folding distance during crushing is reduced by inserting the lattice core, and the deformation behaviour during crushing is axisymmetric.

Figure 2.

Comparison of compressive load-displacement curve for a hollow tube and a sandwich tube

Figure 2.

Comparison of compressive load-displacement curve for a hollow tube and a sandwich tube

In the following, we will discuss the effect of varying the lattice core geometry on the observed wrinkle length. Here, the following equation is used to estimate the relative density of the lattice core:

This equation can be readily derived by considering the volume ratio of the lattice strands in a cubic-shaped lattice core (see

Figure 1(c)).

Figure 5(a) shows a comparison of the compressive load versus deflection curve and

Figure 5(b) shows the deformed shape when the displacement

=0.5 for lattice sandwich tubes based on two different core sizes

but having the same strand diameter

=0.24mm. Also,

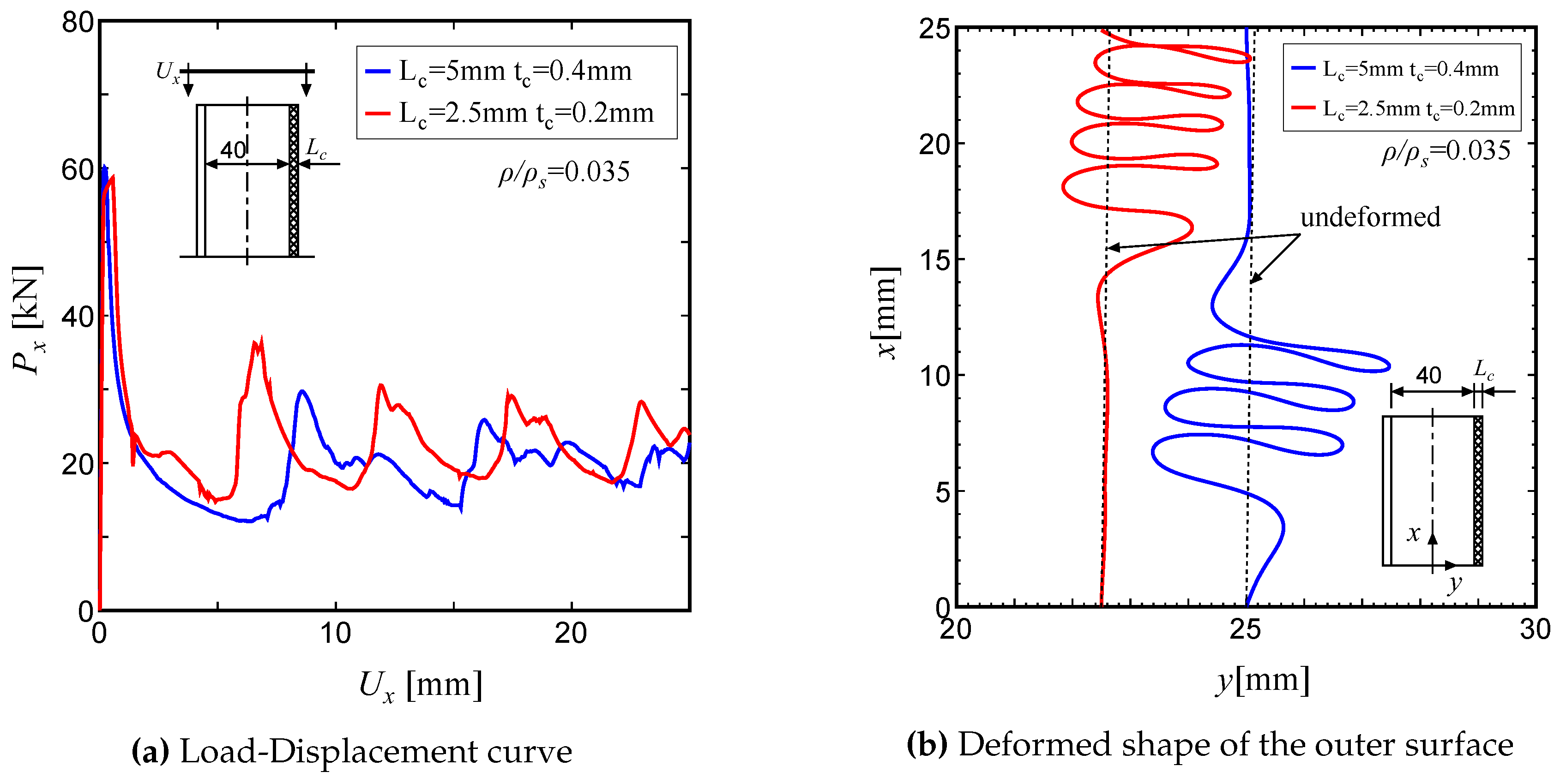

Figure 6(a) and (b) show similar results for lattice tubes based on the same relative density, that is

=0.035. Here, in order to make it easier to observe the folding patterns, the deformed shapes shown in

Figure 5(b) and 6(b), correspond to the outline of the the outer surface of the tube. The index x in

Figure 5(b) and

Figure 6(b) represents the axial coordinate and the index y represents the radial coordinate of the cylinder. As can be seen in

Figure 5(b) and

Figure 6(b), the wrinkle length is strongly dependent on the lattice core length

, with the wrinkle for

=2.5mm being shorter than that for

=5.0mm. This clearly indicates that a shorter wrinkle length is associated with a higher energy absorption capacity.

3.2. Evaluation of Energy Absorption Performance via the Maximum Crush Displacement

and the Average Load )

The total amount of energy absorbed by the lattice tubes during axial compression,

W, can be calculated by multiplying the maximum displacement

, and the average load

, as shown in Equation (

7)

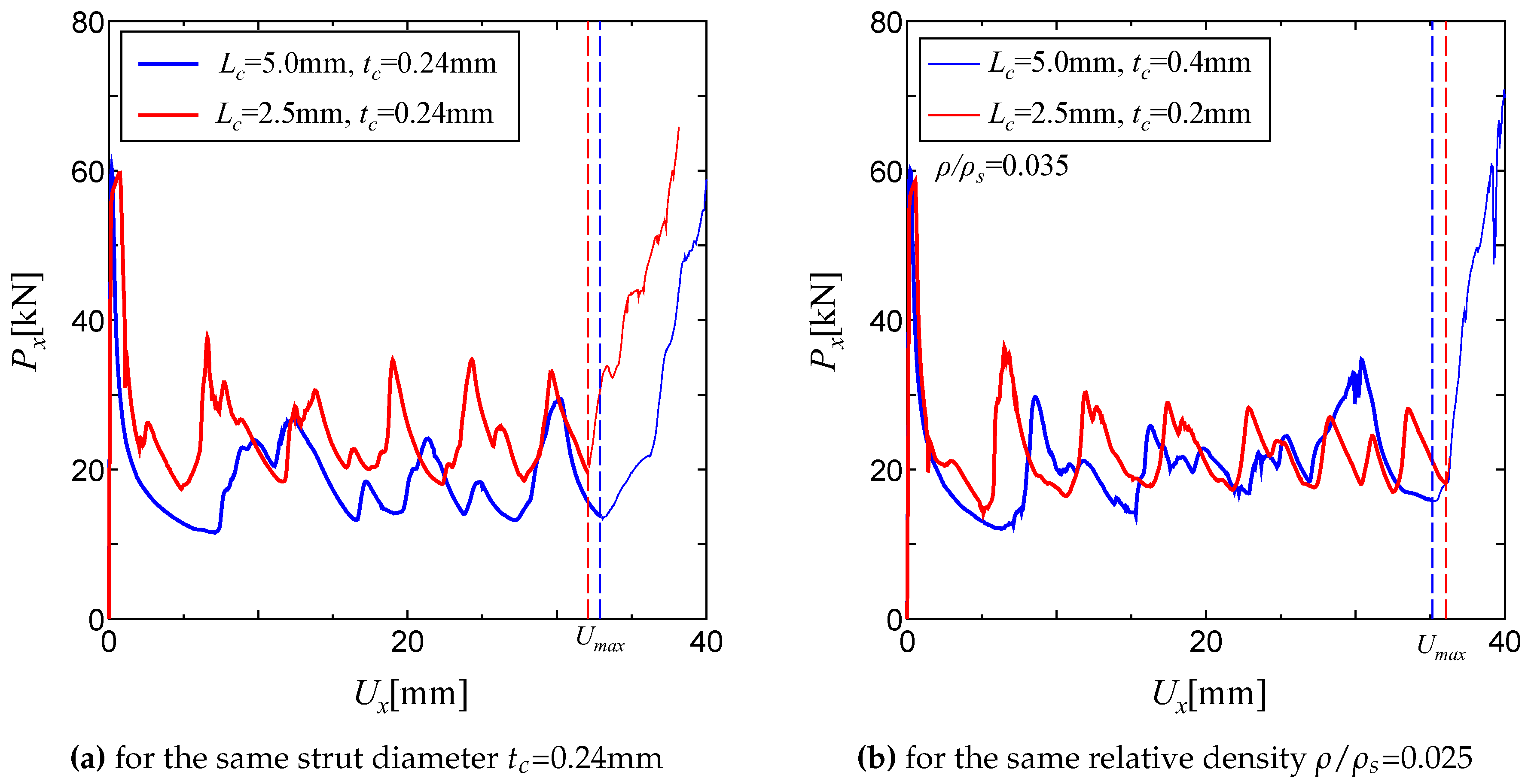

Figures 7(a) and (b) show the load-displacement traces until the load increases dramatically for sandwich tubes with

=2.5 mm and 5.0 mm. Here, the maximum displacement

is defined as the axial displacement at the point where the load suddenly increases, and is shown by the dashed lines in

Figure 7(a) and

Figure 7(b).

Figure 7(a) shows the results for the same strand diameter

=0.24mm, Also,

Figure 7(b) shows the results for the same relative density

=0.035. It can be seen from

Figure 7(a) that the difference in the maximum displacement

, due to the difference in the core length

, is negligible for the same strand diameter

. Similarly, it can be seen in

Figure 7(b) that the difference in

due to changes in the core length

is also negligible for the same relative density of core

. Therefore, it can be concluded that the core length

has little influence on the maximum displacement

during crushing.

Table 3 shows the ratio of the maximum displacement

and the average load

during crushing and the absorbed energy

W of the model used in

Figure 7(a) and (b) for cases of

=2.5mm and

=5.0mm. In the table,

,

and

represent the maximum displacement, the average load and the absorbed energy for

=2.5mm, and

,

and

shows those for

=5.0mm. It can be seen from this table that the ratio of absorbed energy

is always greater than 1, regardless of the strand diameter

and the relative density

. Therefore, it can be concluded that the sandwich tube with the core of

=2.5mm, which has a smaller cell size, offers superior crushing characteristics to that based on a larger cell size of

=5.0 mm.

Table 3.

Comparisons of maximum deflection , average load and absorbed energy W for the lattice sandwich tubes

Table 3.

Comparisons of maximum deflection , average load and absorbed energy W for the lattice sandwich tubes

|

[mm] |

[mm] |

[mm] |

[kN] |

W[Nm] |

/

|

/

|

/

|

| 2.5 |

0.24 |

32.1 |

25.2 |

809 |

0.97 |

1.34 |

1.30 |

| 5.0 |

0.24 |

33.1 |

18.8 |

622 |

| 2.5 |

0.2 |

36.1 |

22.6 |

815 |

1.02 |

1.09 |

1.11 |

| 5.0 |

0.4 |

35.4 |

20.8 |

737 |

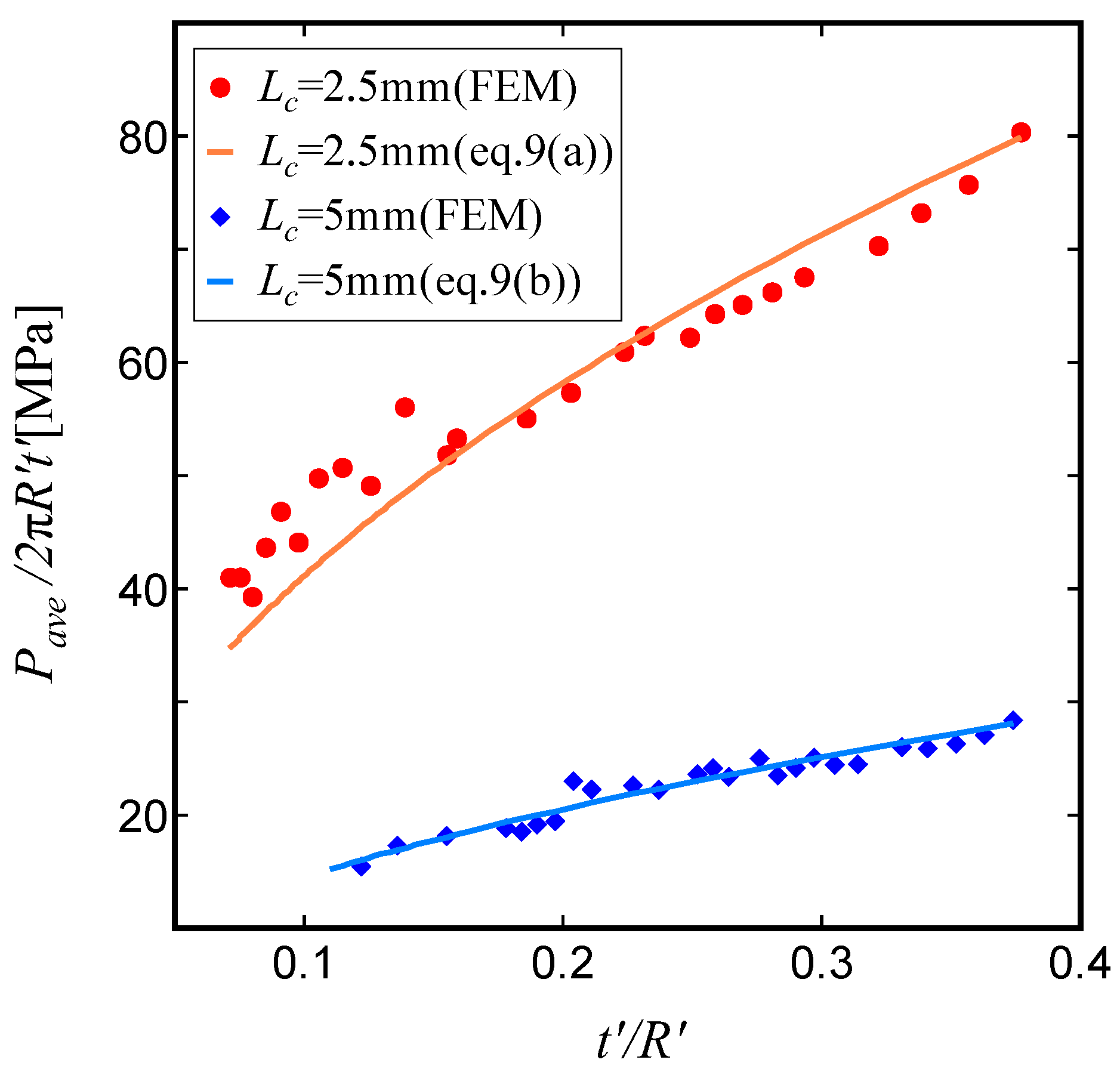

Figure 8 shows the variation of the average stress

obtained from the FE analysis with tube relative thickness

. In addition, the average stress is calculated by considering the cross-sectional area of the sandwich tube. Here, the parameters

and

in the figure represent the equivalent thickness and radius of the sandwich tube, and they are defined as follows:

In

Figure 8, two values of core length,

=2.5mm and 5.0mm, were selected, where the strand diameter

was set to a constant value (0.22mm), and only the tube radius

R was varied. It can be seen from this figure that for each length

, the average stress increases as the wall thickness ratio

increases. This trend is particularly appearent for tubes with a small core length

=2.5mm.

In addition, it is clear that the results for

=2.5mm are always higher than those for

=5.0mm, which is due to the decreased equivalent thickness associated with larger values of

. In other words, as the core length

becomes small, the distance between the inner and outer tubes decreases, giving a higher relative density

for the same strand diameter

. In contrast, when the core length

is large, the density

decreases for the same strand diameter

. As a result, the contribution to the equivalent tube thickness decreases for larger values of

. As can be seen in

Figure 8, the average stress is proportional to

, which is similar to that observed for a continuum single tube. Curve fits calculated using the least squares method are represented by the blue and red curves in

Figure 8, which are based on the following equation:

Here. the parameter

C is a constant that depends on the lattice core length

, and is derived from the curve fitting based on the FE data. For example,

C=5.6 for

=2.5mm and

C=2.0 for

=5.0mm.

3.3. Relationship Between Deformation Mode and Energy Absorption W

In this section, the relationship between the observed deformation modes (axisymmetric and non-axisymmetric) of the sandwich tube and the associated energy absorption

W is discussed.

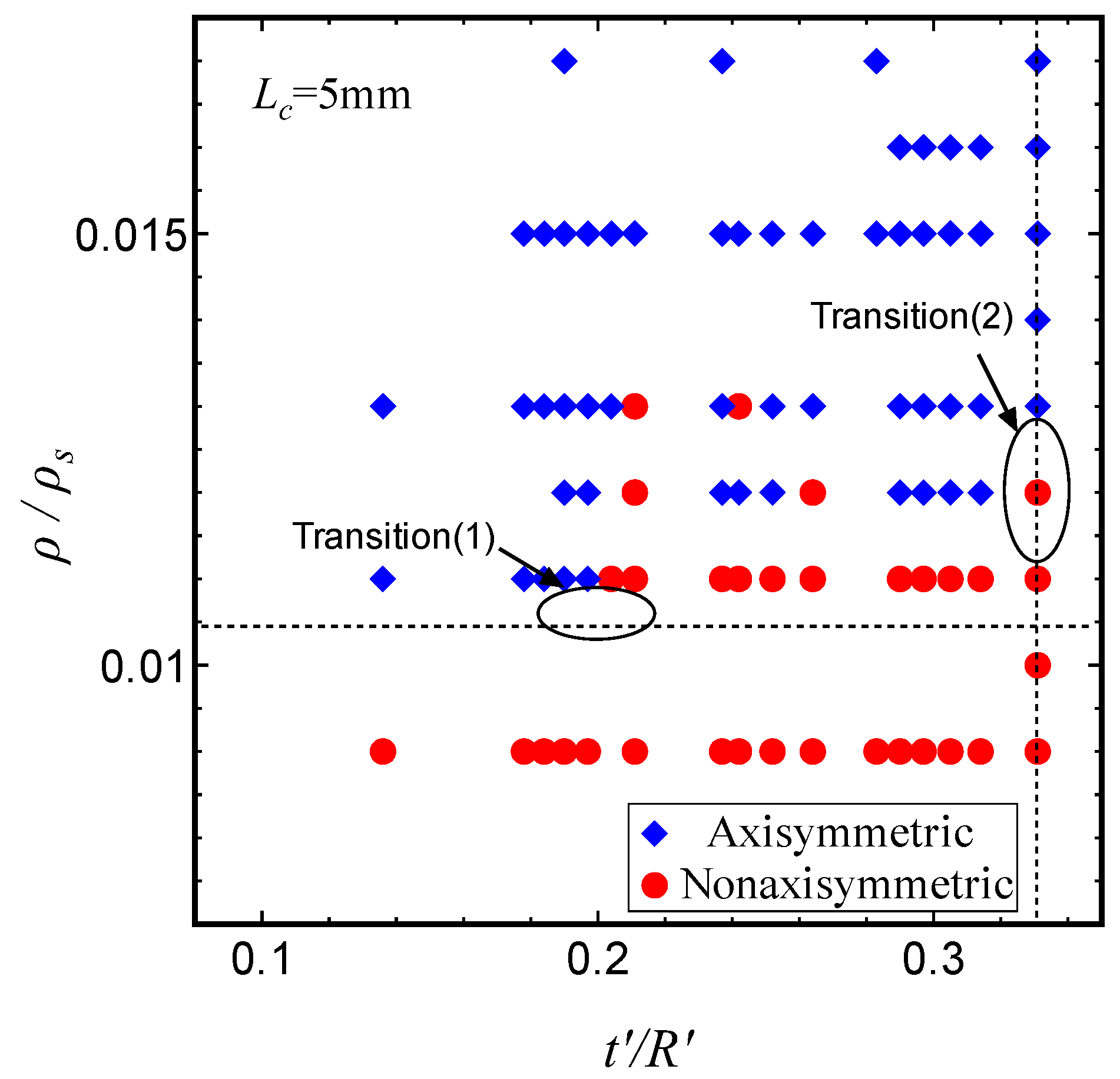

Figure 9 shows the deformation modes (axisymmetric and non-axisymmetric) identified in a sandwich tube with a lattice core length of

=5.0mm when the tube was crushed to half of its length, classified by the tube thickness ratio

and the relative density of the lattice core

. The range of dimensions for the sandwich tube in the deformation mode map are

mm and

mm. It can be confirmed from this figure that smaller values of the thickness ratio

result in the larger values of relative density

of the lattice core, increasing the likelihood of axisymmetric deformation during crushing.

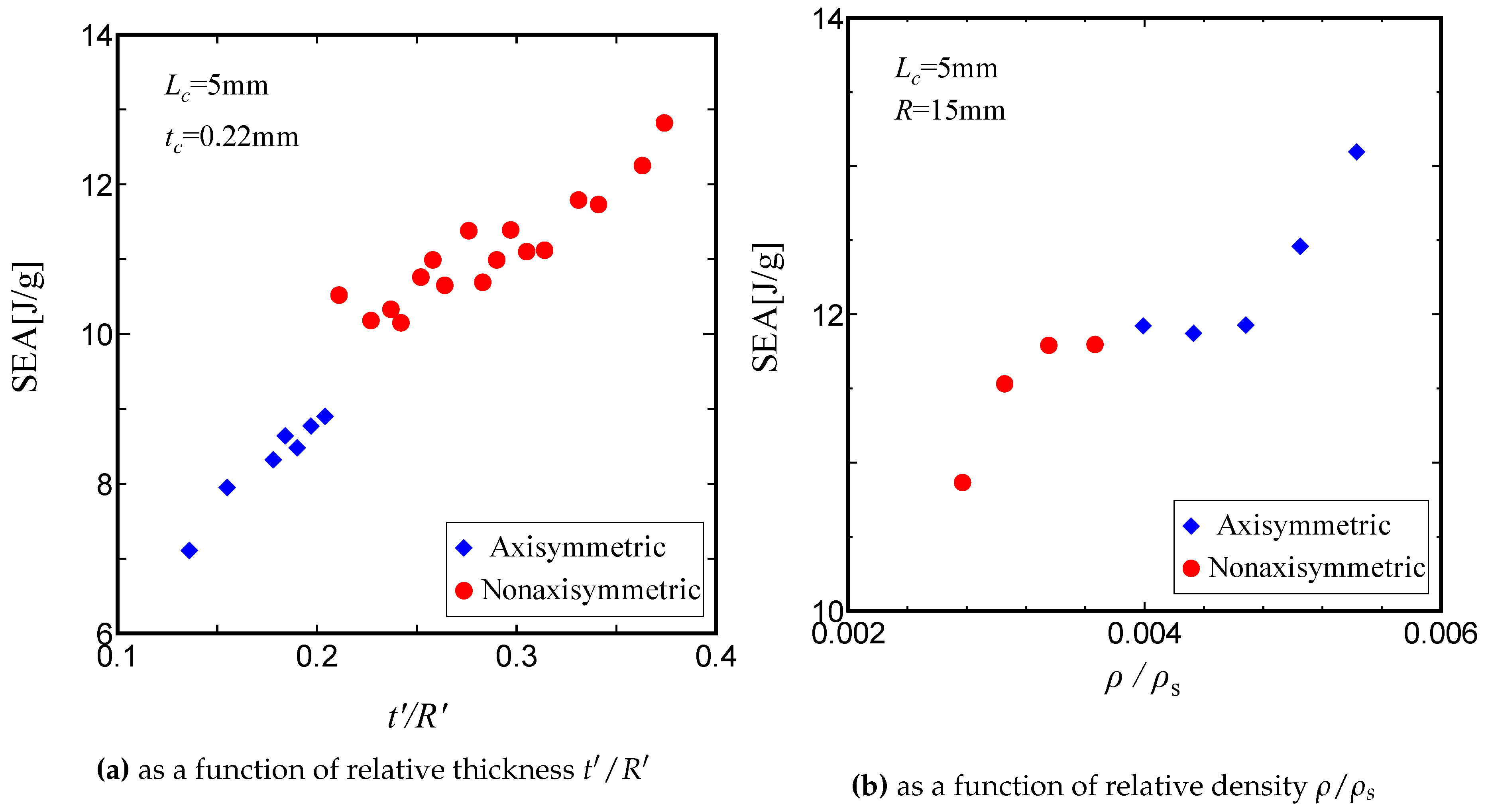

Figure 10(a) shows the variation of the Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) with thickness ratio

, where the relative density

is held constant. Here, the red symbols in the figure correspond to the results under non-axisymmetric deformation, and the blue symbols show those linked to axisymmetric deformation. It is clear that as the relative wall thickness

increases, the deformation behaviour changes from axisymmetric to non-axisymmetric deformation (depicted by Transition(1) in

Figure 9). It can be seen from this figure that the SEA value increases as the wall thickness

increases, and increases rapidly near the point where the deformation behaviour switches from axisymmetric to non-axisymmetric. In other words, for a sandwich tube with a lattice core with a given relative density, increasing the wall thickness

results in an enhanced energy absorption per unit mass (SEA). However, since the wrinkle length for a non-axisymmetric deformation pattern is greater than that for axisymmetric deformation, there are more undeformed parts in the tube. Clearly, a non-axisymmetric deformation mode is an undesirable deformation response.

Figure 10(b) shows the variation of SEA with the relative density

for a constant the wall thickness

(depicted by Transition(2) in

Figure 9). As can be seen in

Figure 10(b), the SEA increases as the relative density

increases, and the deformation mode shifts from non-axisymmetric deformation to axisymmetric deformation.

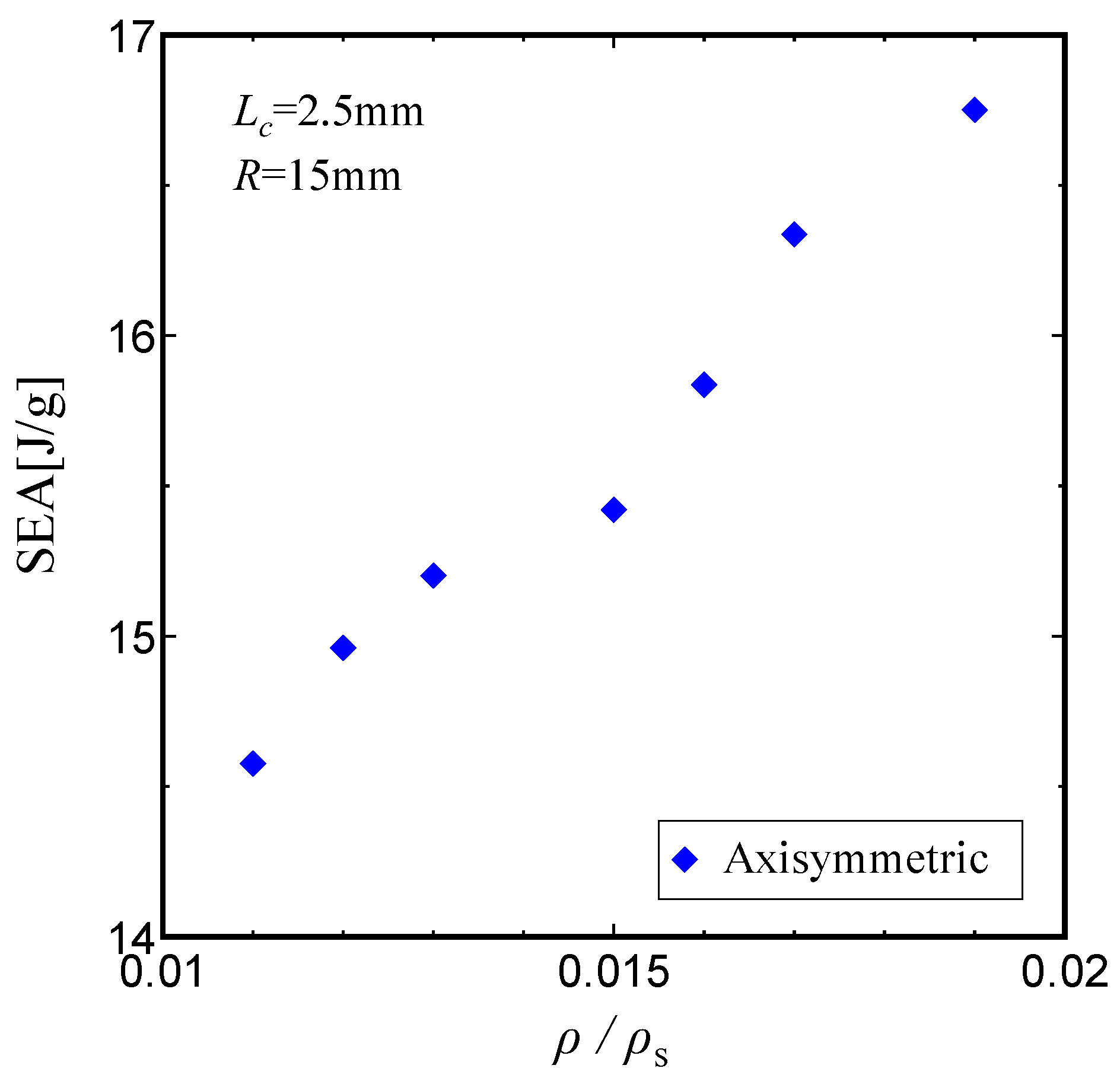

Figure 11 shows the variation of SEA as the strand diameter

is varied from 0.2 to 0.3 mm, for a constant core length

=2.5mm and tube radius

R=15mm. As was the case in

Figure 10(b), the SEA increases as the relative density of the core

increases. This evidence suggests that designers can enhance the specific energy absorption (SEA) by inserting a lattice core between two thin-walled circular tubes. Designers can determine the appropriate lattice unit size by considering the maximum tube weight, tube radius and the requirements for specific absorbed energy.

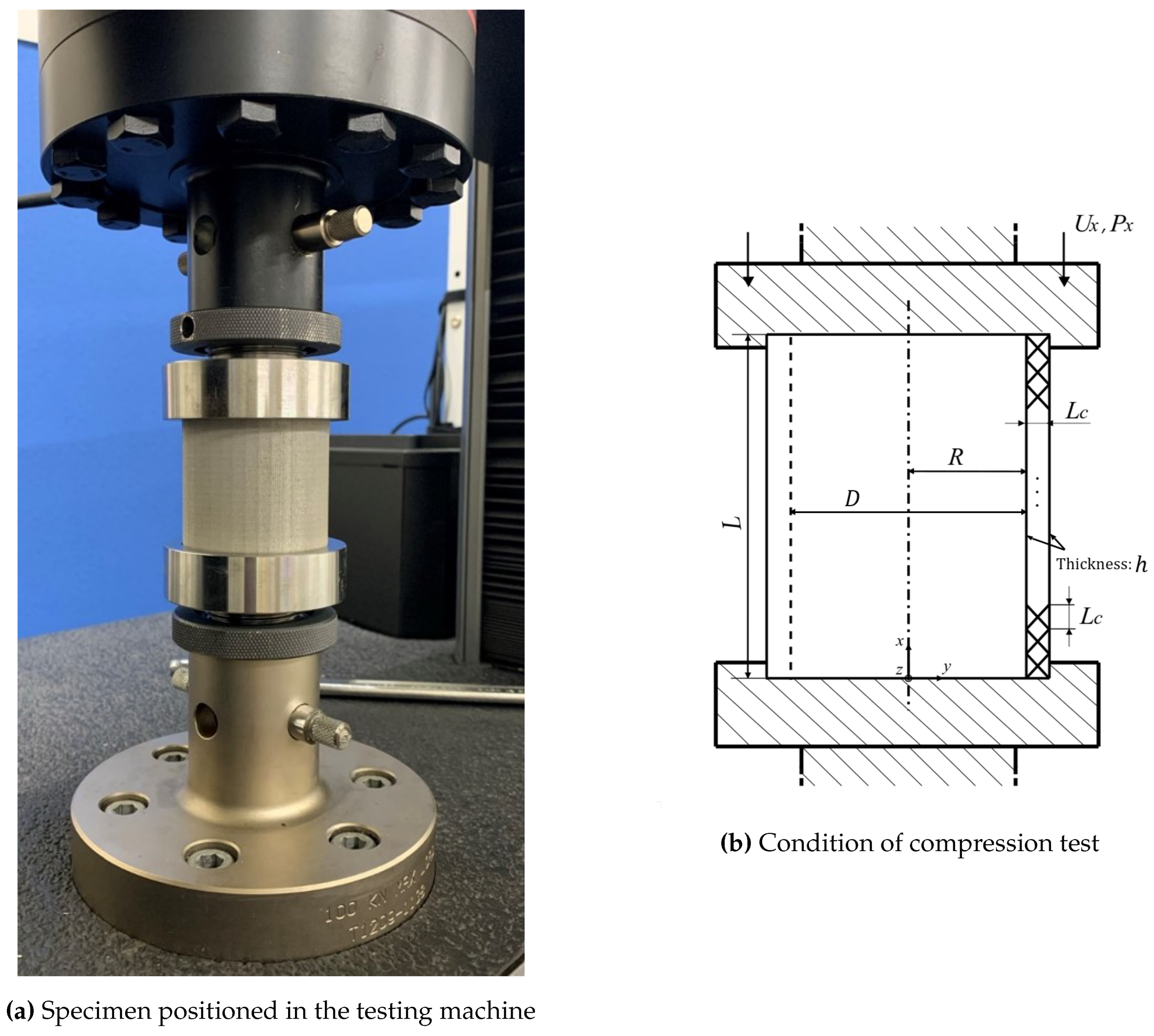

3.4. Comparison with Experimental Results

In this section, the results of axial compression tests on lattice sandwich tubes fabricated using a metal 3D printer (ProX 300, 3D Systems), and the prediction of the FE analysis are compared and discussed. Firstly, we explain the experimental conditions for the axial compression tests. A part of the cylindrical specimen manufactured in the metal 3D printer is shown in

Figure 12. The test machine used in this study is an INSTRON 5982. Both ends of the cylindrical specimen were fixed firmly. A photograph of the compression test is shown in

Figure 13(a) and a schematic diagram is shown in

Figure 13(b). The test specimens used in this experiment were based on SUS630, and the dimensions of the specimens (Shapes A∼F) are shown in Table 4. The number of samples was one each for the thin-walled cylinders and three each for the sandwich tubes (depicted by Samples 1,2,3). The effects of the inner tube diameter

D and the strand diameter

on loading performance and compression behaviour were investigated. The experimental conditions were quasi-static compression at a crosshead speed of

m/s. The maximum displacement was set to

=30mm, but for comparison with the analytical results, only values up to

=25mm will be considered.

Table 4.

Summary of the geometrical parameters of the specimens for compression testing

Table 4.

Summary of the geometrical parameters of the specimens for compression testing

| Specimen |

L[mm] |

D[mm] |

h[mm] |

[mm] |

[mm] |

coretype |

| A |

50 |

35 |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

| B |

45 |

| C |

55 |

| D |

30 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

BCC |

| E |

40 |

| F |

50 |

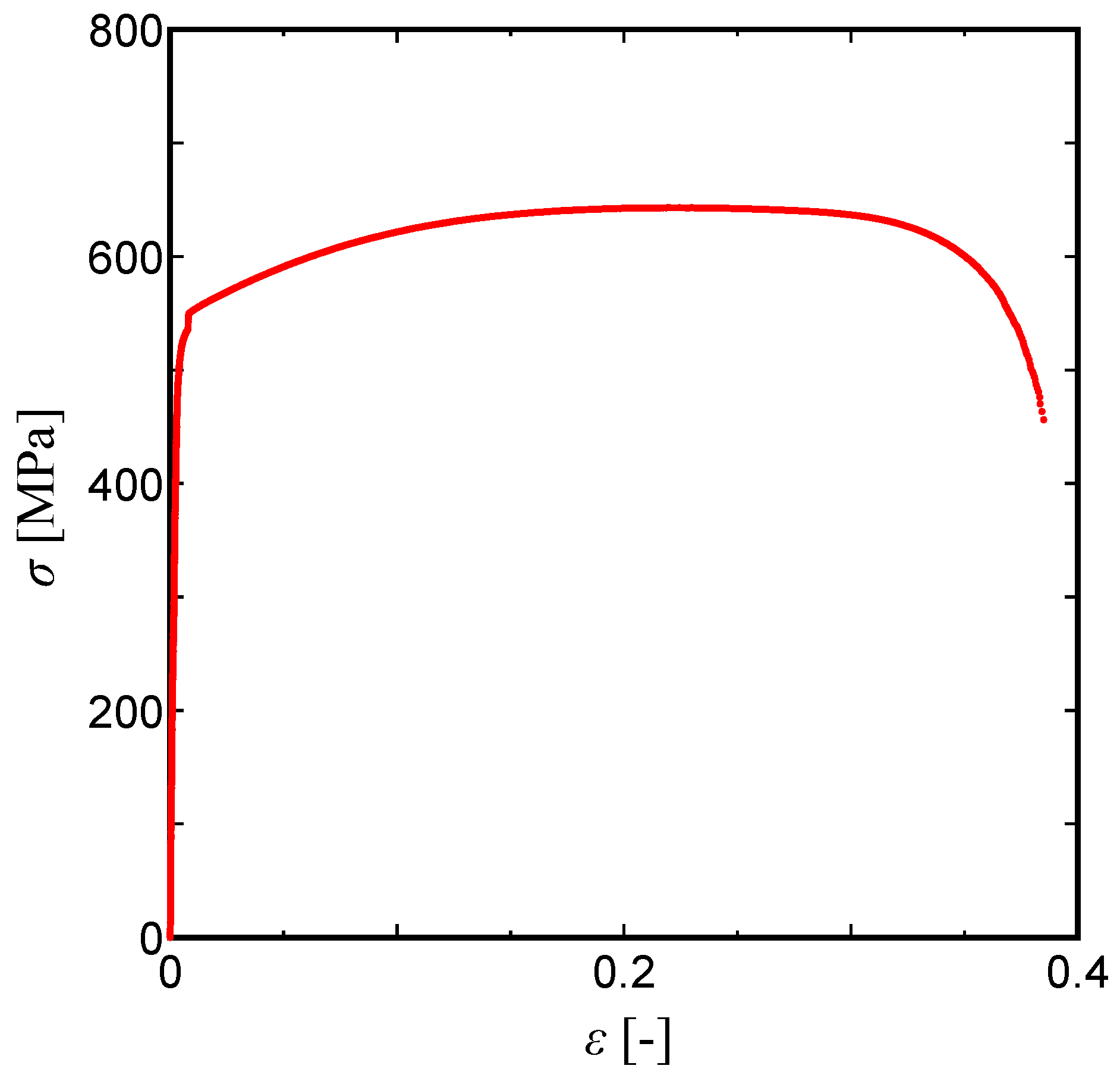

The material properties for the FE analysis are based on tensile tests on SUS630 as shown in

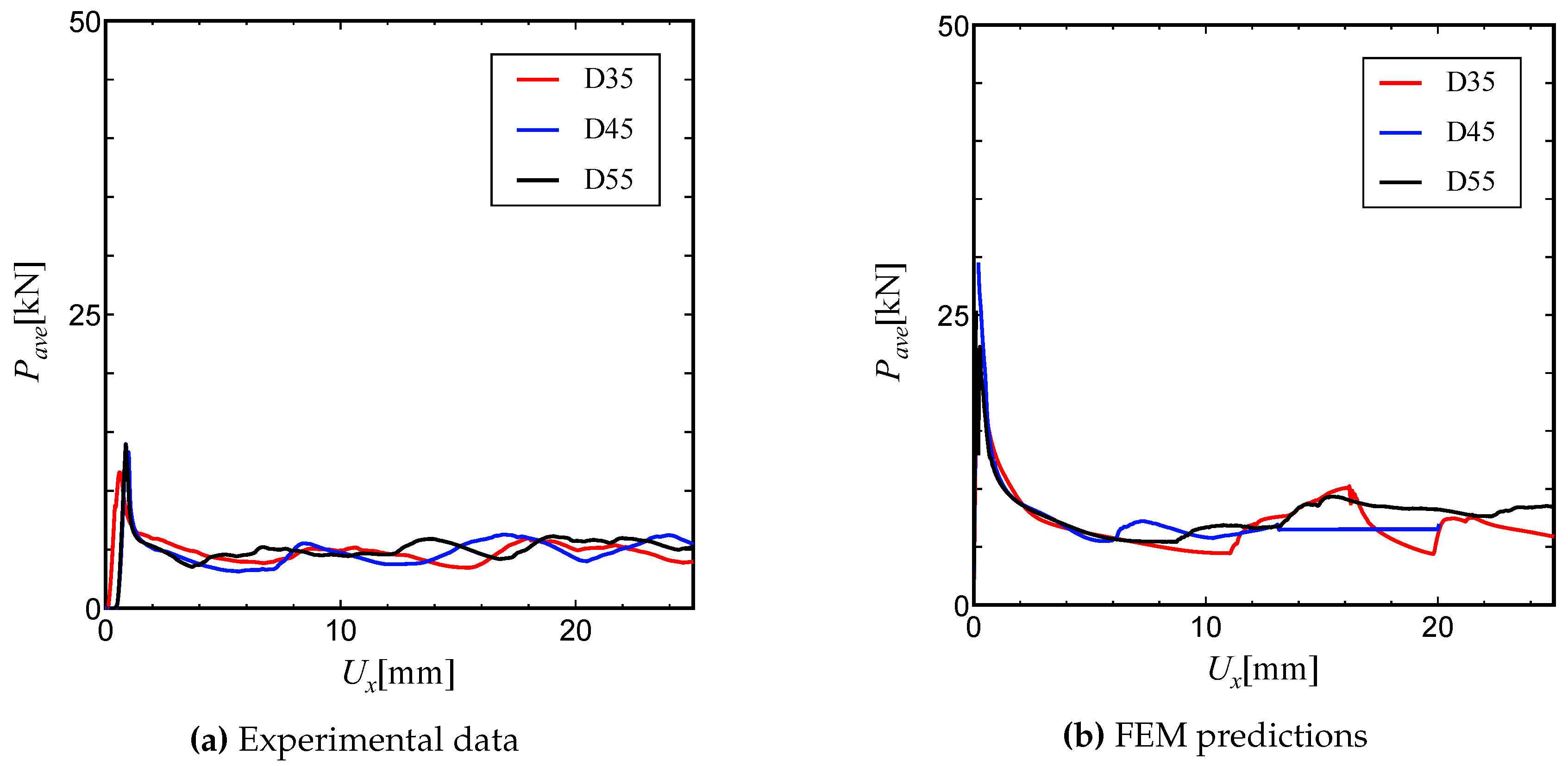

Figure 14. The load-displacement diagrams for the thin-walled single tubes with tube diameters

D=35mm (Shape A), 45mm (Shape B) and 55mm (Shape C) are shown in

Figure 15(a) and

Figure 15(b).

The peak load and average load for each model are given in Table 5. The ratio in the table represents the ratio of the experimental value to the numerical analysis value.

Table 5.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing on the thin-walled tubes

Table 5.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing on the thin-walled tubes

| Specimen |

D[mm] |

[kN] |

[kN] |

| FEM |

Experiment |

EXP/FEM |

FEM |

Experiment |

EXP/FEM |

| A |

35 |

23.146 |

11.630 |

0.51 |

7.195 |

4.825 |

0.68 |

| B |

45 |

29.795 |

14.658 |

0.49 |

7.273 |

4.741 |

0.65 |

| C |

55 |

35.408 |

14.092 |

0.40 |

7.850 |

5.023 |

0.64 |

By considering the compression tests and the FE data, it was found that the experimental load values, especially the peak load

, were smaller than those predicted by the FE analysis. The reason for this discrepancy can be explained by the occurrence of an undesirable rotation near the fixed ends of the tubes. Also, the degree of the parallelization of the specimen edges cannot be guaranteed with a high degree of accuracy for specimens manufactured using additive manufacturing. As a result, the direction of the compression load could be inclined, and a part of the cylindrical end may deform and buckle prematurely. Thus, the initial shape of the experimental load-displacement curve is lower than that obtained from the FE analysis, and the peak load

is smaller than the FE predictions. The similar tendency has also been observed and discussed for a torsional crushing behaviour of foam-filled thin-walled square columns by W. Chen et al. [

36].

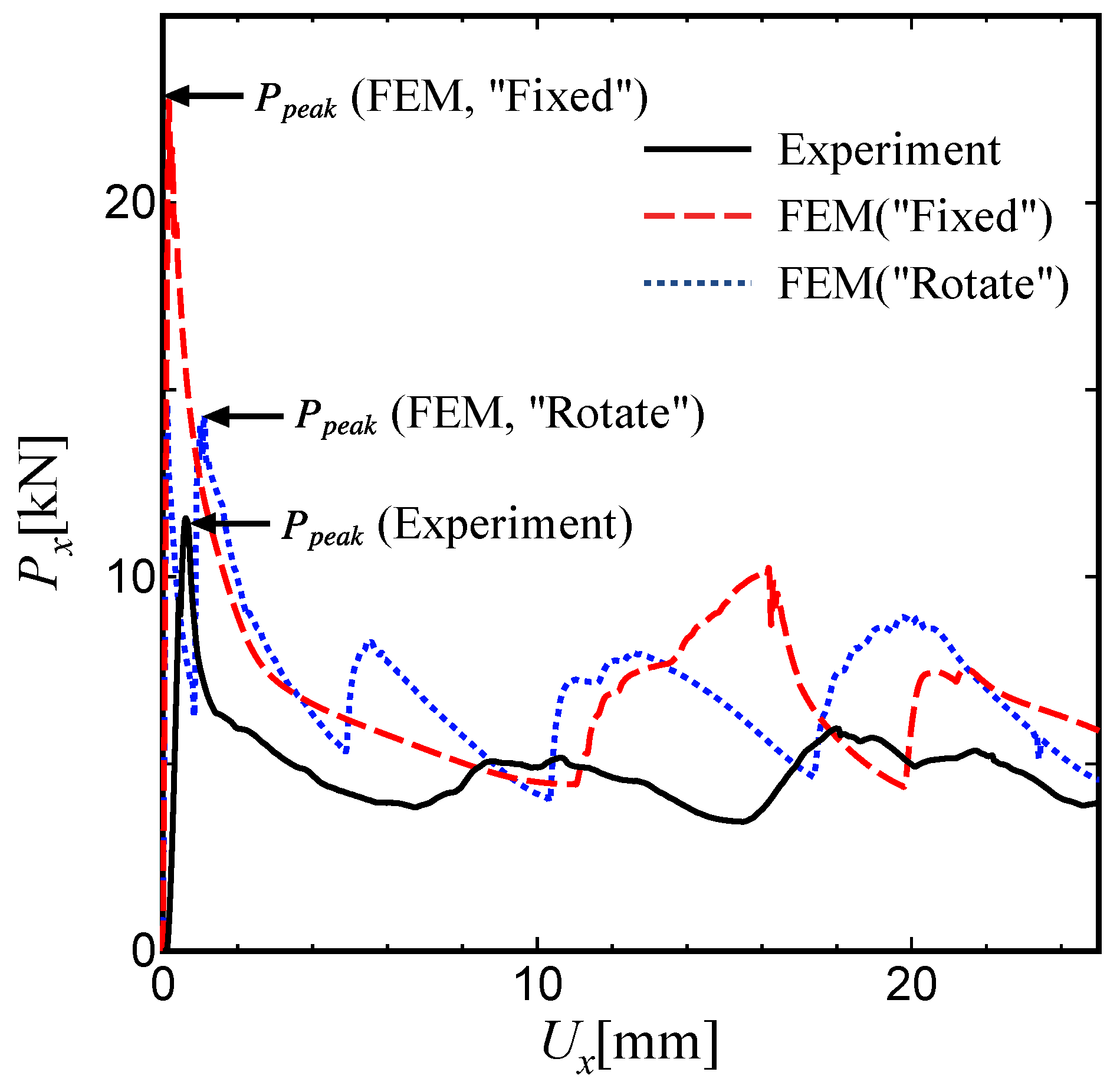

Figure 16 shows the comparisons of the load-displacement curve for a single tube (Shape A) under different boundary conditions for the nodes on both tube edges. In the figure,“Fixed” represents that all rotational movements around x-, y- and z-directions as well as parallel movements along all directions are constrained for the nodes on both sides. Also, “Rotate” represents that the rotational movements are only allowed. Since in the experimental machine, there is a carved groove on each touched surface to interfere parallel movement of the specimen, the latter boundary condition is closer to the actual experiment. As can be found from the figure that the calculated peak load under the “Rotate” condition is almost coincident with experimental result.

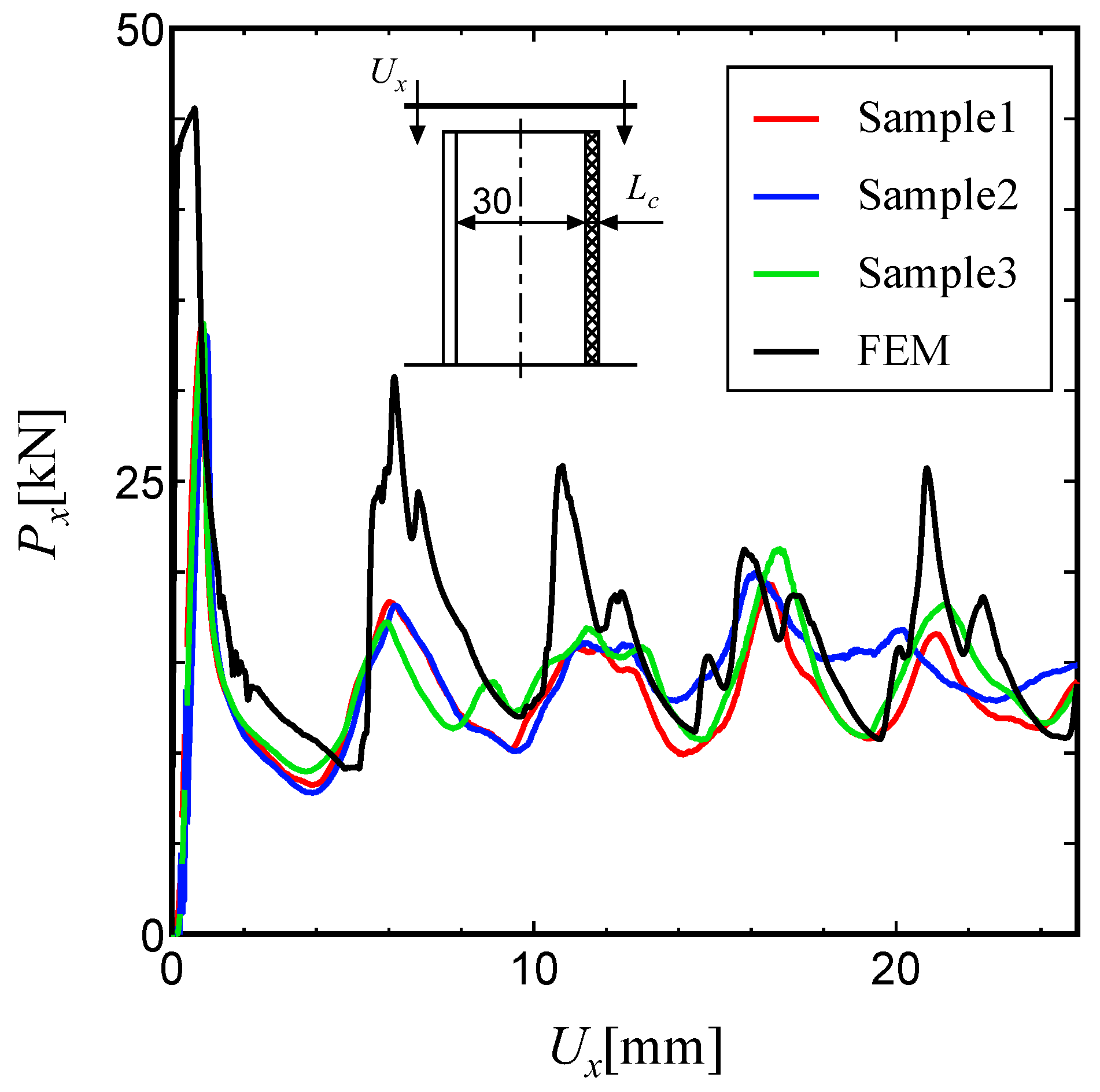

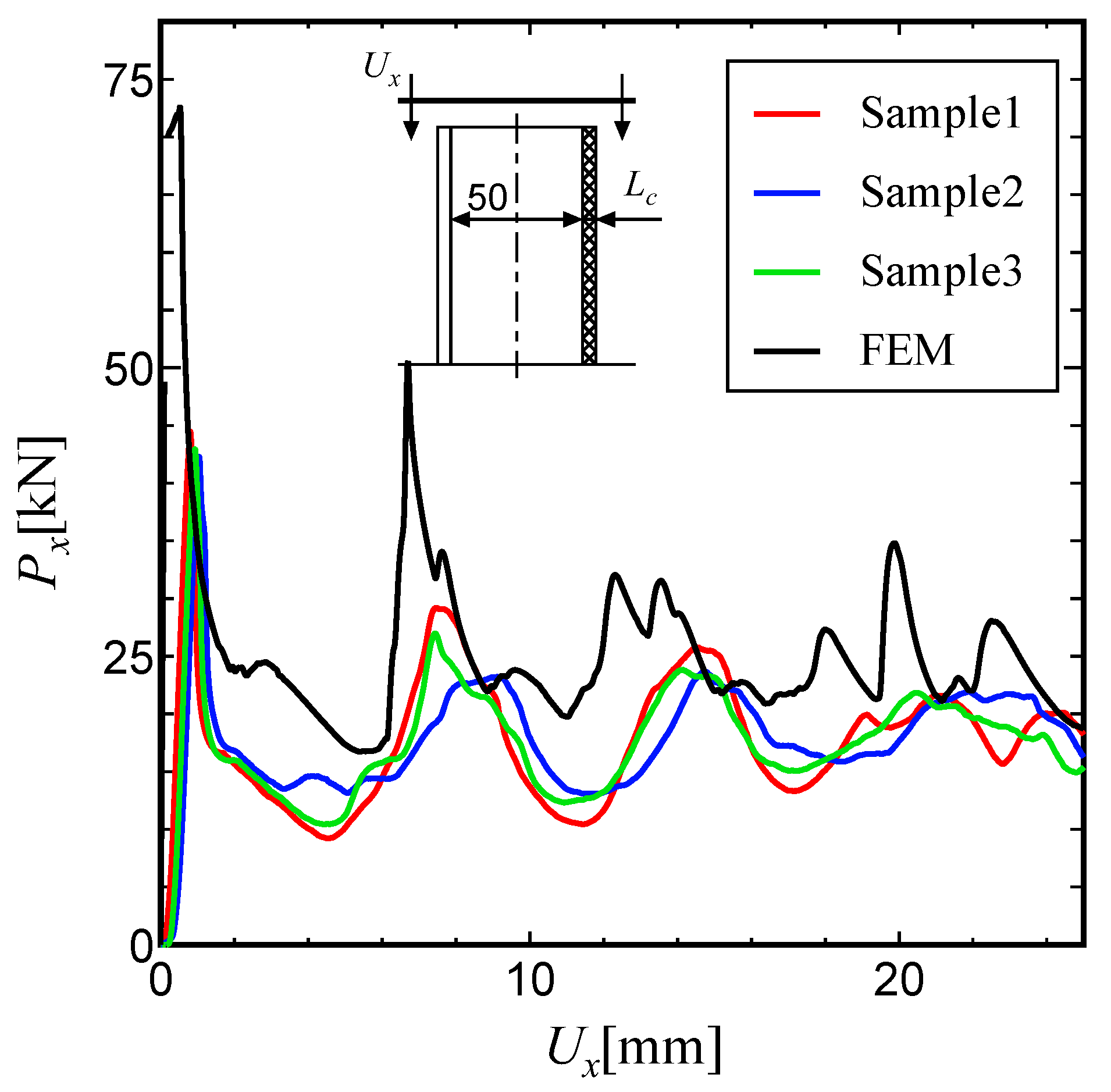

Here, the results of the compression tests and the numerical analysis are compared for a sandwich tube with a BCC lattice core, an inner tube diameter

D=30mm and a strut diameter

=0.2mm (Shape D). The load-displacement traces for both models are shown in

Figure 17, and the peak load

and the average load

values for each model are given in Table 6. The ratio

in the table represents the ratio between the experimental value and the average value from the numerical analysis.

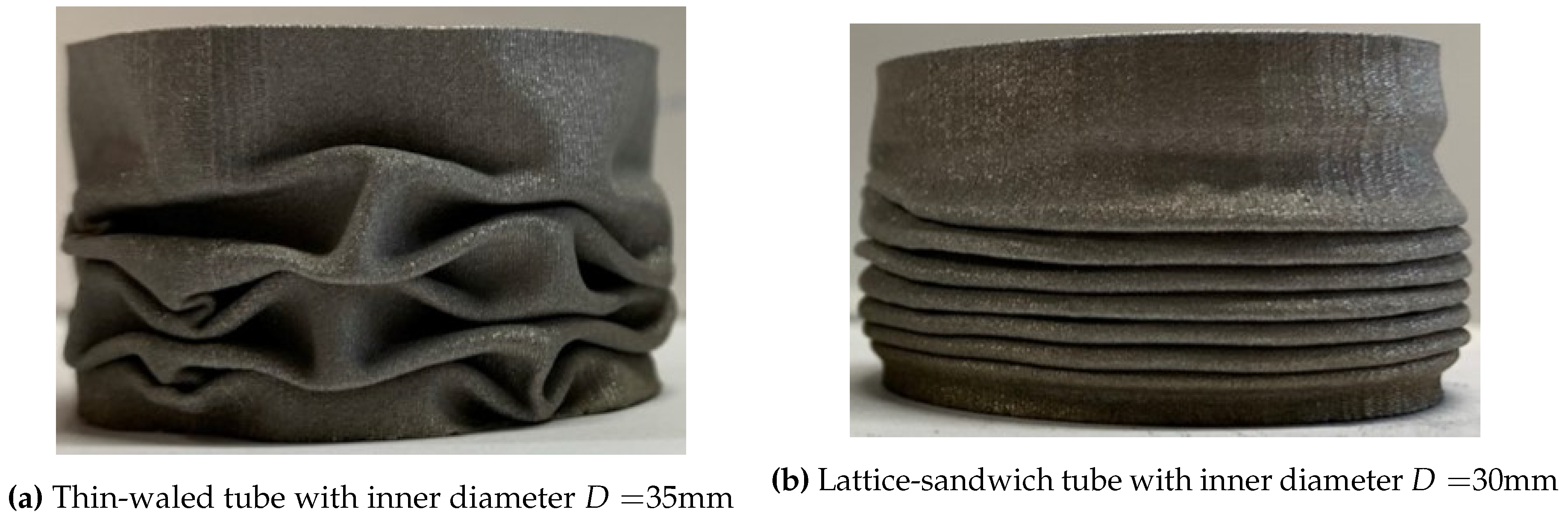

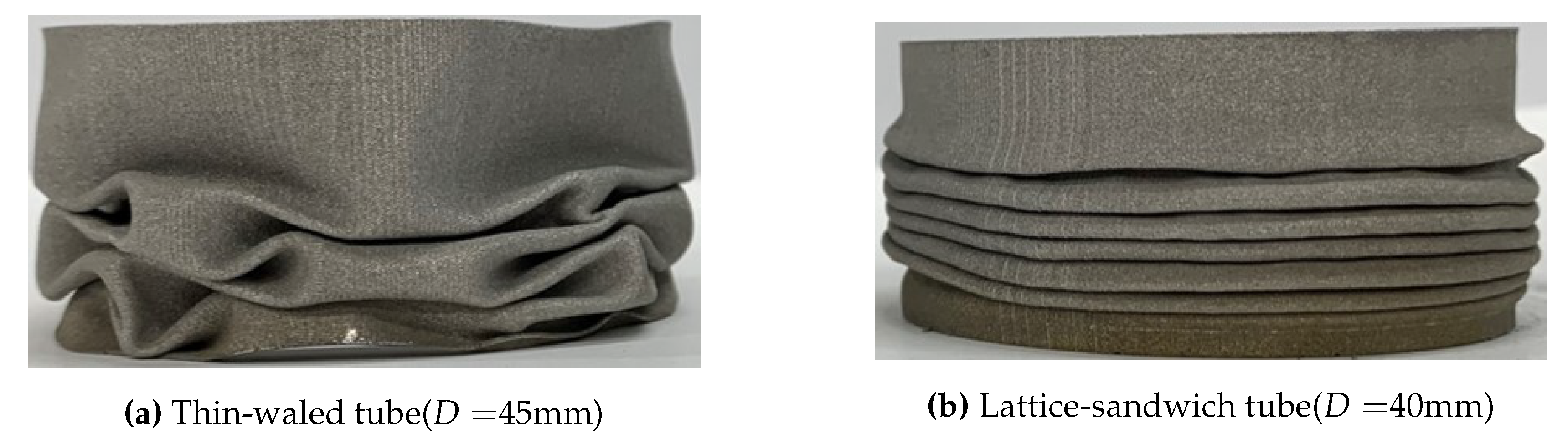

Figure 18 shows specimens following compression testing on two cylindrical shapes with equal outer tube diameters, a thin-walled single tube with

D=35mm (Shape A) and a lattice sandwich tube with

D=30mm (Shape D).

Table 6.

Comparison of the and values with numerical data from an FE analysis following experimental compression testing for a lattice sandwich tube with inner diameter D =30mm (Specimen shape D).

Table 6.

Comparison of the and values with numerical data from an FE analysis following experimental compression testing for a lattice sandwich tube with inner diameter D =30mm (Specimen shape D).

| Specimen D |

[kN] |

[kN] |

|

D=30mm, =0.2mm |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

| Sample1 |

|

33.771 |

|

|

13.226 |

|

| Sample2 |

45.471 |

33.073 |

0.74 |

16.727 |

14.039 |

0.82 |

| Sample3 |

|

33.677 |

|

|

13.984 |

|

In the following, the results of the experimental tests and the numerical analyses are compared for a sandwich tube with a BCC lattice core with an inner tube diameter

D=40mm and a strut diameter

=0.2mm (Shape E). The load-displacement diagrams for both models are shown in

Figure 19, and the peak load

and the average load

for each model are shown in Table 7.

Figure 20 shows two samples with equal outer tube diameters after compression testing.

Figure 20(a) shows a thin-walled single tube with

D=45mm (Shape B) and

Figure 20(b) shows a lattice-sandwiched tube with

D=40mm (Shape E).

Table 7.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing (D=40mm, Specimen shape E)

Table 7.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing (D=40mm, Specimen shape E)

| Specimen E |

[kN] |

[kN] |

|

D=40mm, =0.2mm |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

| Sample1 |

|

39.503 |

|

|

15.798 |

|

| Sample2 |

59.320 |

37.878 |

0.64 |

21.075 |

15.581 |

0.76 |

| Sample3 |

|

37327 |

|

|

16503 |

|

Next, the results of compression tests and the numerical analysis are compared for a sandwich tube with a BCC lattice core with an inner tube diameter

D=50mm and strut diameter

=0.2mm (Shape F). The load displacement traces for both models are shown in

Figure 21, and the peak load

and the average load

values for each model are shown in Table 8. Photographs of specimens after compression testing on two cylindrical samples with equal outer tube diameters, a thin-walled single tube for which

D=55mm (Shape C) and a lattice sandwich tube for which

D=50mm (Shape F) are shown in

Figure 22.

Table 8.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing (D =50mm, Specimen shape F)

Table 8.

Comparison of the experimental and predicted values of and following compression testing (D =50mm, Specimen shape F)

| Specimen F |

[kN] |

[kN] |

|

D=50mm, =0.2mm |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

FEM |

EXP |

EXP/FEM |

| Sample1 |

|

44.594 |

|

|

17.805 |

|

| Sample2 |

72.903 |

42.285 |

0.59 |

25982 |

17927 |

0.68 |

| Sample3 |

|

42.947 |

|

|

17.584 |

|

From these results, it can be seen that the deformation behaviour of the tube under axial compression testing can be controlled in an axisymmetric mode by introducing a lattice core, and that the load increased and decreased due to the generation of wrinkles during compression. In the case of the sandwich tubes, there is an error between the experimental load values and the predicted values, but the cause of this error is considered to be the same as in the case of thin-walled single cylinders.

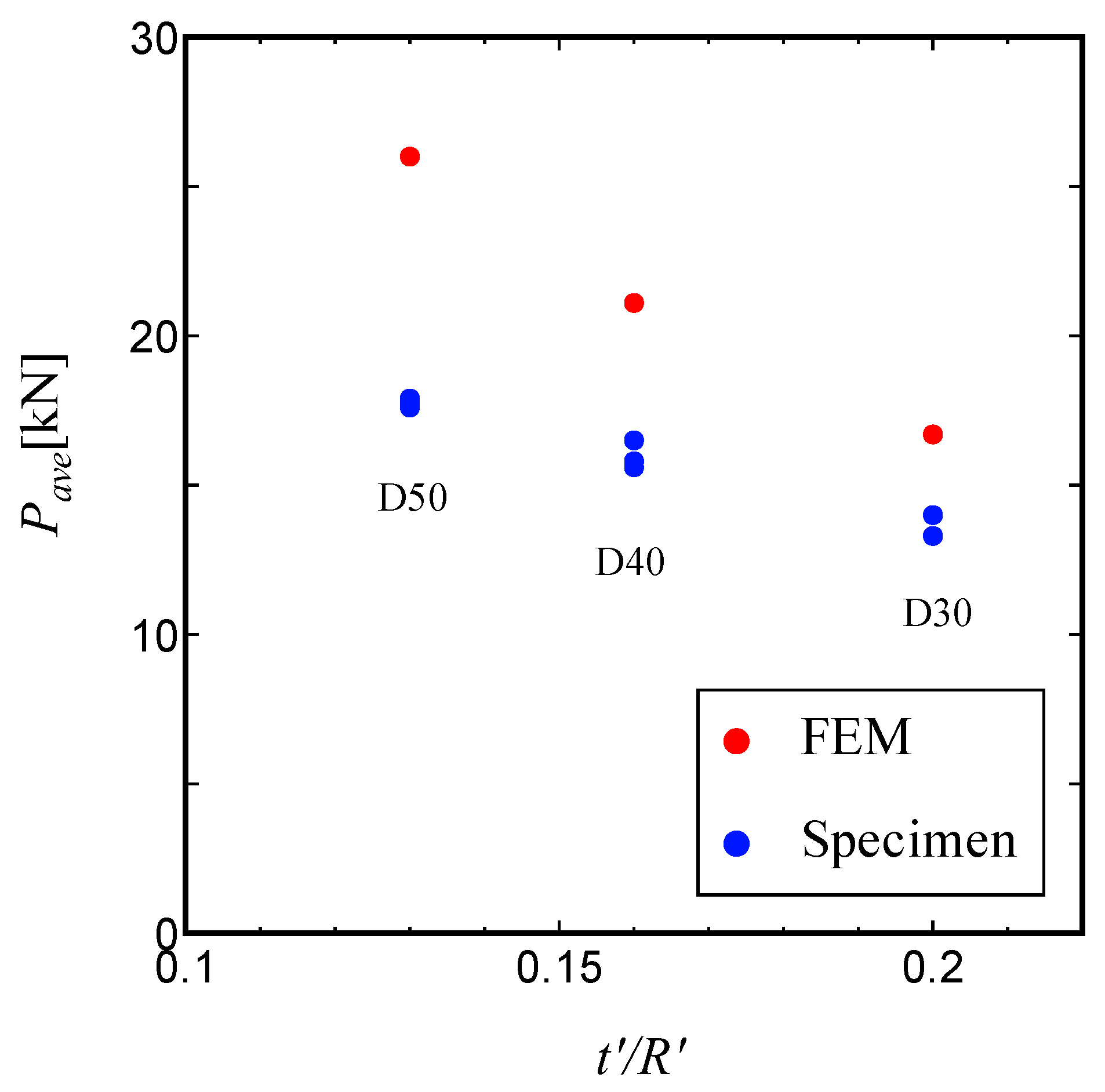

Figure 23 shows the variation of Pave with the wall thickness ratio

for lattice cylinders with values of D equal to 30, 40 and 50mm. Included in the figure are both the experimental data and the numerical predictions. As a result, as the cylindrical wall thickness ratio

decreases, i.e., as the inner tube diameter

D increases, the average load

becomes larger. It has also been shown that the trends in the load values during the compression tests and the numerical analysis are similar.