1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) originate from neuroendocrine cells and represent a diverse group of solid tumors. They are most frequently found in the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system, with less common occurrences in the genitourinary system [

1,

2]. These tumors are challenging to diagnose due to their heterogeneity and often indolent nature. Biochemical diagnostics for NETs include both non-specific and specific markers. Serum chromogranin A is a widely used non-specific marker, while specific markers such as serotonin and 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) are essential for detecting certain types of NETs [

3]. The selection of these markers depends largely on the type and location of the suspected tumor, which aids in tailoring the diagnostic approach [

3,

4]. The field of NET diagnostics and treatment is evolving, with ongoing research focusing on identifying new predictive markers [

5]. These studies aim to enhance early detection, improve prognostic evaluations, and tailor treatments more effectively. Despite advancements, the complexity and variability of NETs necessitate continuous exploration of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to better manage this challenging group of tumors. According to the eighth edition of the AJCC/UICC (American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control) recommendations, the ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) guidelines and the 2022 WHO (World Health Organization) classification, NETs are defined as NET G1 (Ki-67 <3%), NET G2 (Ki-67 3–20%), NET G3 (Ki-67 >20%, usually between 21–55%) and NEC (neuroendocrine carcinoma, Ki-67 usually > 55%) (i.e., low-differentiated carcinomas with a highly aggressive clinical course) [

6,

7,

8]. Based on the 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors, bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (BPNETs) are categorized into four groups: typical carcinoids (neuroendocrine tumors grade 1), atypical carcinoids (neuroendocrine tumors grade 2), large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and small cell carcinomas [

9].

The study involve evaluating the concentration in serum of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (SFRP3), and segment polarity protein dishevelled homolog 1 (DVL1) in patients with NETs.

LRP6, a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, exhibits a distinctive structure that enables its multifaceted roles as both a co-receptor in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and a receptor for ligand-mediated endocytosis [

10,

11,

12]. Recent studies have highlighted its significance in metabolic regulation, particularly within nutrient-sensing pathways [

13,

14]. The Wnt signaling pathway, essential for regulating gene expression, cell proliferation, and migration during embryonic development and tumorigenesis, involves the binding of Wnt protein ligands to receptors of the FZD family [

15,

16,

17]. This pathway is categorized into canonical and non-canonical signaling branches [

13]. Canonical Wnt signaling is mediated by the FZD and LRP5/6 receptors, while non-canonical signaling involves FZD receptors and other co-receptors, influencing downstream Wnt/planar cell polarity, Wnt/receptor tyrosine kinase, and Wnt/calcium pathways [

18,

19]. In canonical Wnt signaling, the binding of Wnt proteins (e.g., Wnt1 or Wnt3) to their receptors, including the FZD family and LRP5/6, initiates a cascade leading to the phosphorylation of the adaptor protein Dishevelled [

10,

18]. This phosphorylation promotes DVL's interaction with Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway, thereby modulating the pathway's activity [

20,

21].

SFRP3 modulates the Wnt signaling pathway through direct interaction with Wnt proteins. These proteins are crucial in regulating cell growth and differentiation in specific cell types, including the maturation of chondrocytes and the development of long bones [

22]. LRP6 acts as a co-receptor essential for the activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Together with Wnt and FZD proteins, LRP6 forms a complex that facilitates signal transduction. These proteins exhibit both paracrine and endocrine effects [

15,

23,

24,

25].

The DVL1 proteins could play a crucial role in the signal transduction pathways activated by various Wnt proteins [

26]. They are involved in both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways by binding to the cytoplasmic C-terminus of FZD family proteins and transmitting signals to downstream effectors. Additionally, DVL1 promotes the internalization and degradation of FZD proteins following Wnt signaling [

18,

27,

28,

29].

These three proteins are integral components of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, which is crucial in regulating cellular metabolism [

10,

18]. Thus, analyzing the concentrations of these proteins in the blood serum of patients with NETs is well justified. According to available data, this study is among the few that evaluate LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1 in NET patients. However, no previous studies have used ELISA tests for this analysis.

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the serum concentrations of LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1 between patients with neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and healthy individuals, and to correlate these findings with selected demographic, clinico-pathological, and biochemical characteristics. Additionally, we analyzed and compared the concentrations of these proteins in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) and bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (BP-NETs), correlating these results with their respective characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

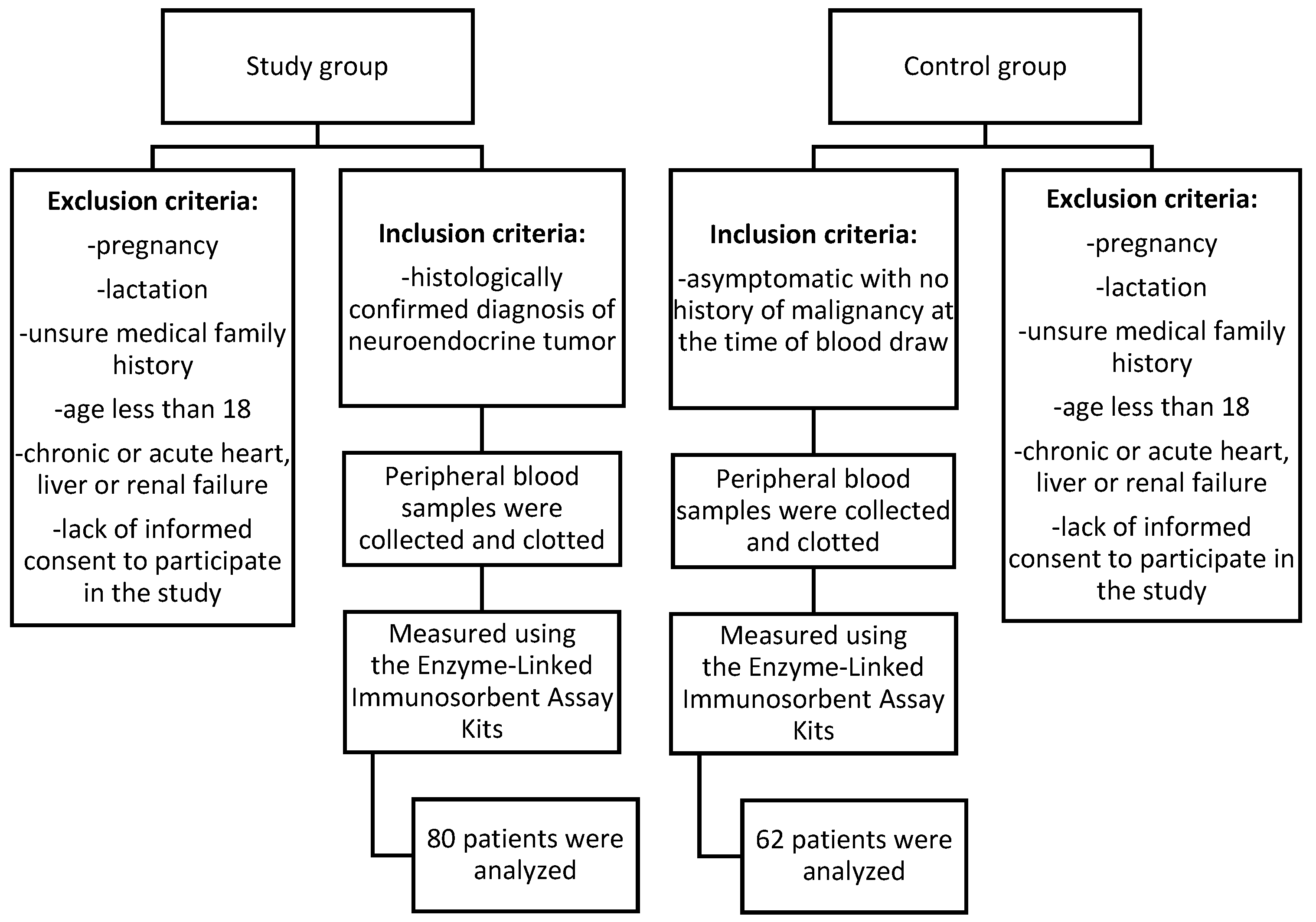

Patients for this study were recruited from the Department of Endocrinology and Neuroendocrine Tumors, Department of Pathophysiology and Endocrinology at the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland. The main inclusion criteria for both the study and control groups were being aged 18 or older and providing signed consent to participate, with the study group specifically including individuals with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor, not undergoing chemotherapy and control group including healthy volunteers with no history of malignancy at the time of blood draw. Details are presented in

Table 1. All patients from study group underwent core needle biopsy or histopathological examination after surgery. In each case, the diagnosis was verified during hospitalization to ensure accuracy. This aligns with the recommendation for biopsy confirmation as highlighted in studies [

30,

31]. Patients were newly diagnosed and had not undergone any prior treatment. The only procedures performed were core needle biopsies or surgical interventions for diagnostic purposes. After reviewing medical records, information on patients' neuroendocrine markers, including chromogranin A, serotonin, and 5-HIAA, was gathered.

Histological confirmation of NETs was performed by experienced pathologists according to the WHO 2019 [

32] classification for GEPNETs and the WHO 2015 [

9] classification for BPNETs, with tissue specimens analyzed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry.

The extent of the disease was assessed using anatomical imaging methods, including Computed Tomography (CT) and/or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), along with functional imaging such as [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for well-differentiated NETs and [18F]FDG PET/CT for G2/G3 NETs. All imaging studies were evaluated by specialists in radiology or nuclear medicine. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy were utilized for assessing gastroenteropancreatic (GNETs) and rectal neuroendocrine tumors (RNETs).

2.2. Funding Statement and Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia (20 September 2022 No. PCN/CBN/0052/KB1/24/II/22).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients included in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients included in the study.

2.3. Study Design

Peripheral blood samples were collected into S-Monovette tubes with a clotting activator (Sarstedt, Germany). To obtain serum, the blood was centrifuged for 15 minutes at 3500 rpm, and the serum was subsequently stored at -80°C for further analysis. Serum concentrations of LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1 were assessed using ELISA, following the procedures described by the manufacturers. The analytical procedure adhered to the manufacturer's guidelines as outlined in the technological manuals provided with the kits.

All ELISA tests were performed at the Department of Medical and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Zabrze, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland. To determine the concentrations of the tested samples, a standard curve was prepared using the standards provided with the kits. All standards and serum samples were run in duplicate, with serum samples diluted as specified by the instructions (2x for LRP6, undiluted for SFRP3, and 2x for DVL1). The ELISA plates were read using a Bio-Tek µQuant Universal Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek, USA) at a primary wavelength of 450 nm. Data analysis was conducted using KCJunior Software (Bio-Tek, USA), and absorbance values were converted to concentrations in ng/ml for all three proteins measured.

The assays used were from Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd., China, with product numbers EH1124 for LRP6, EH8604 for SFRP3, and EH1769 for DVL1. The minimum detectable doses were 0.188 ng/ml for LRP6, 0.094 ng/ml for SFRP3, and 0.094 ng/ml for DVL1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Qualitative data are expressed as percentages. For quantitative data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. Normally distributed data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (M±SD). For non-normally distributed data, medians with interquartile ranges (Me (Q

1-Q

3)) are provided. Comparisons between variables were made using the Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. The Spearman correlation coefficient was utilized to evaluate the relationships between variables. To compare the levels of the analyzed parameters between the BP-NET and GEP-NET groups, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed. In these analyses, BP-NET is considered as positive and GEP-NET is considered as negative. In the ROC curve analysis, the cut-off point was determined by analyzing the Youden index (J) values. It was calculated according to the following formula: J = sensitivity + specificity – 1. The Youden index can take values from 0 to 1. The most optimal point is characterized by the highest J value and is located closest to the upper, left part of the graph. A significance threshold of 0.05 was set for all tests, which were conducted as two-sided. Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica software (TIBCO Software Inc. (2017). Statistica (data analysis software system), version 13.

http://statistica.io).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic of Study Groups

The study included 142 participants in total. Among them, 56% (N=80) were in the study group, consisting of patients with NETs. The remaining 44% of participants (N=62) formed the control group and were healthy individuals with no history of malignancy at the time of blood collection. In the study group, 20% of patients were diagnosed with BP-NET, whereas 80% were diagnosed with GEP-NET. Additional details can be found in

Table 1.

There was no significant difference in age (p=0.083) or BMI (p=0.385) between the study and control groups. Additionally, sex distribution did not differ significantly between the groups (p=0.343). No significant associations were found for hypertension (p=0.205) or smoking status (p=0.911). However, a significant correlation was observed for diabetes (p<0.05). Details are presented in

Table 2.

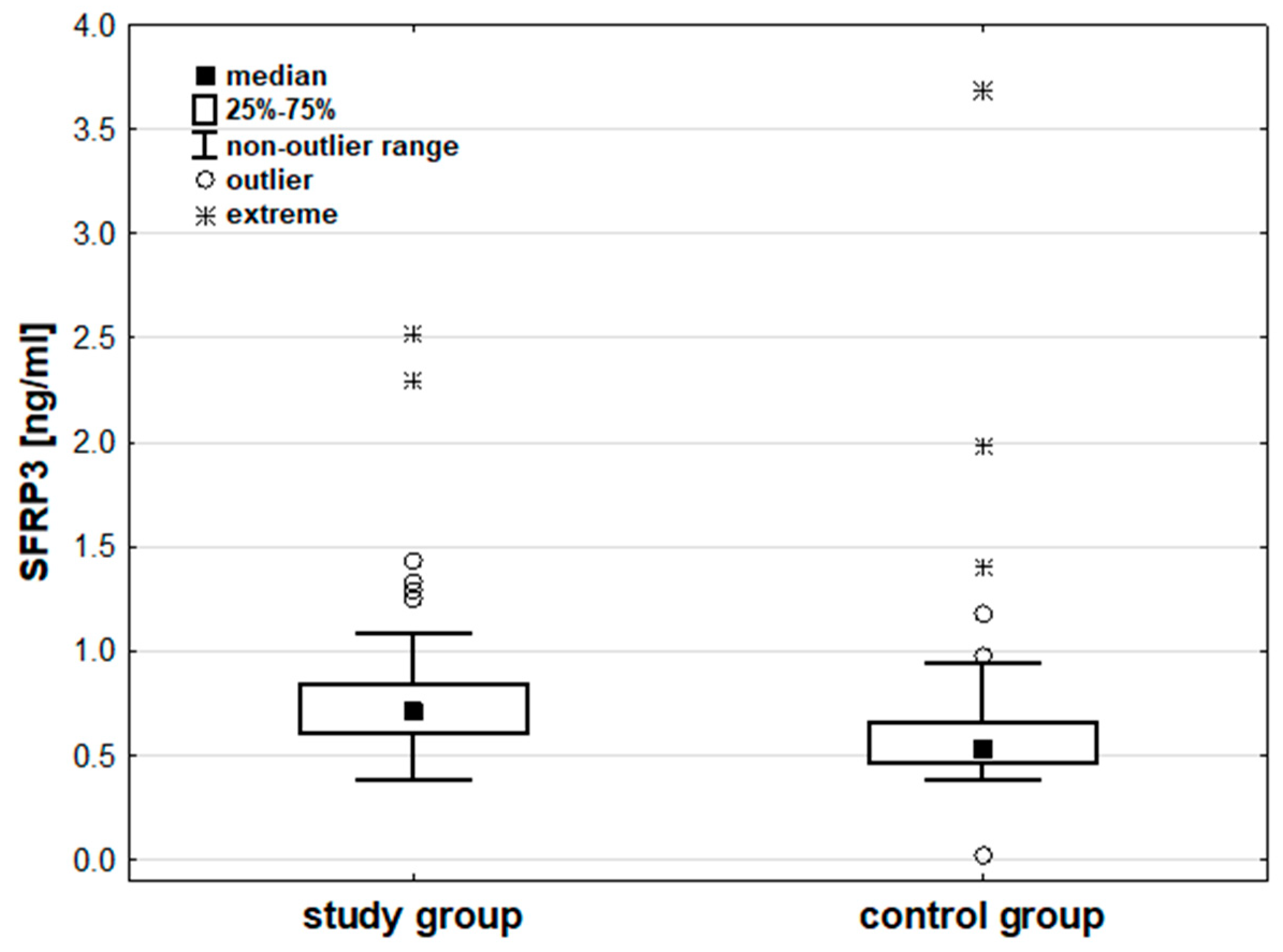

Analysis of the measured parameter concentrations indicated no significant differences in LRP6 (p=0.486) and DVL1 (p=0.058) concentrations between the groups. SFRP3 concentrations were significantly higher in the study group than in the control group (p<0.001). Additional details can be found in

Table 3 and

Figure 2. Details are also presented in

Table S1 in the supplementary materials.

No significant differences were found between protein concentrations and age, BMI, Ki-67, or clinical stage for LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1. However, a significant negative correlation was observed between DVL1 and age in the control group (p<0.01), as well as between LRP6 and Ki-67 in the study group. Details are shown in

Table 4. Additionally, no significant differences were found between protein concentrations and other parameters such as sex, histological grade, metastasis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis, or bone metastasis.

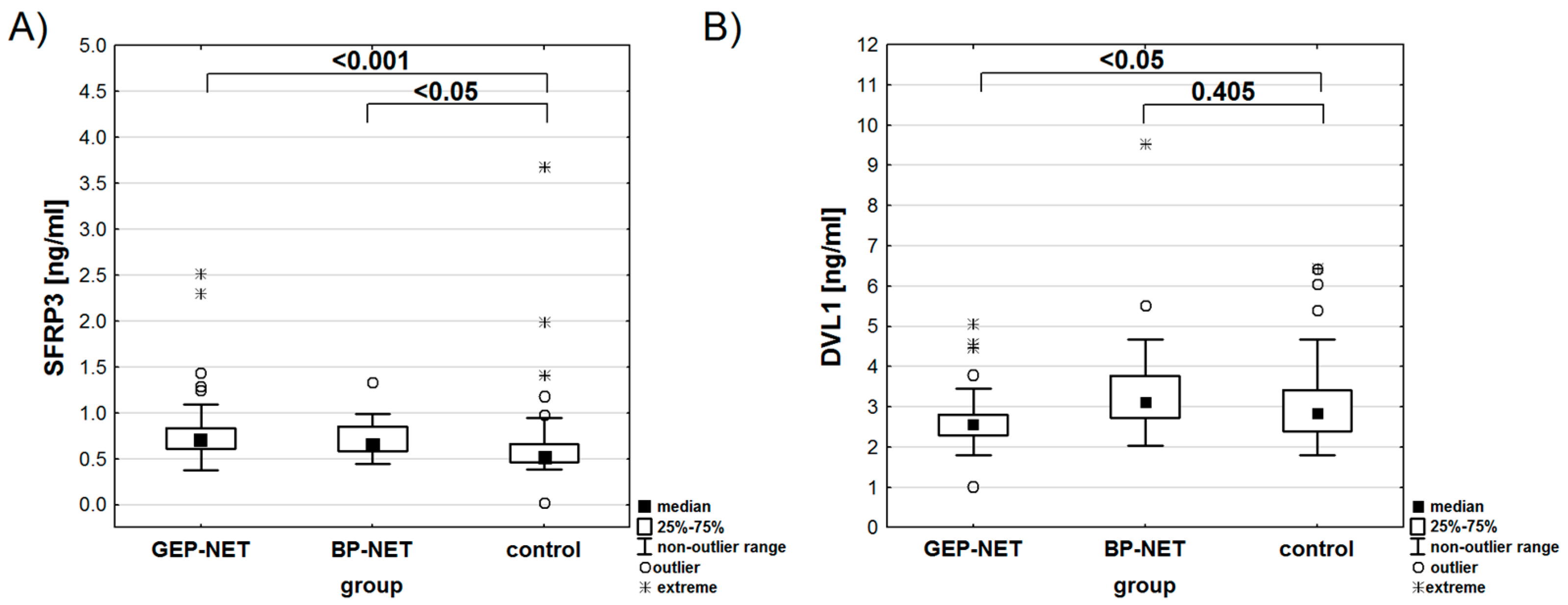

The analysis showed no significant differences in LRP6 (p=0.373) or SFRP3 (p=0.601) concentrations based on the location of the primary tumor. However, DVL1 concentrations varied significantly (p<0.01). The highest concentration of SFRP3 was observed in the BP-NET and GEP-NET groups, with statistically significant differences compared to the control group (

Table 5,

Figure 3A). In contrast, the concentration of DVL1 reached its highest levels in the BP-NET group, while the GEP-NET group and the control did not show any statistical differences (

Figure 3B). An analysis of the area under the ROC curve was performed for the diseased patients. For DVL1, the area under the ROC curve was significantly greater than 0.5 (p<0.001), with a cutoff point qualifying patients into the BP-NET group at 2.83 ng/ml (

Figure 4). For SFRP3 and LRP6, the areas under the ROC curves did not statistically differ from the value of 0.5 (p=0.609 and p=0.396, respectively).

When examining specific primary tumor sites (lung, pancreas, small intestine, duodenum, stomach, rectum), there were no significant differences in LRP6 (p=0.333) and SFRP3 (p=0.154) concentrations, but DVL1 results showed significant variation (p<0.01). Further comparisons revealed significant differences between the pancreas and lung (p<0.05) and between the small intestine and lung (p<0.05).

There was no significant correlation between LRP6 or SFRP3 concentrations and the concentrations of chromogranin A, serotonin, or 5-HIAA. Notably, DVL1 showed a negative correlation with chromogranin A (p<0.001) and weak negative correlations with serotonin (p<0.05) and 5-HIAA (p<0.05). Further details are provided in

Table 6. Additionally, protein concentrations did not correlate with glucose, TCH, or TG concentrations.

In comparing the concentrations of LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1 between smokers (study group N=9) and non-smokers (control group N=12), no statistically significant differences were found (LRP6: z=0.618, p=0.537; SFRP3: z=1.866, p=0.187; DVL1: z=1.325, p=0.185). Moreover, analysis of the relationships between these protein concentrations revealed no significant correlations between SFRP3 and LRP6 (ρ=0.146, p=0.203) or between SFRP3 and DVL1 (ρ=0.020, p=0.857). However, there was a weak positive correlation between LRP6 and DVL1 (ρ=0.284, p<0.05).

4. Discussion

The rising incidence of NETs poses a significant medical challenge, as advanced stages remain incurable and often fatal [

33,

34,

35]. Despite extensive research, effective treatments are limited. NETs typically originate in the gastroenteropancreatic system and lungs [

36]. Treatment for inoperable or advanced NETs depends on factors such as tumor site, grade, extent of metastasis, hormonal activity, and genetic characteristics [

37,

38]. Although there have been advancements in understanding NET genetics and the introduction of targeted therapies, new systemic treatments for advanced NETs are still critically needed [

39,

40].

A recent in vitro study explored targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway as a novel therapeutic approach for NETs, highlighting its crucial role in regulating tumor cell growth and invasion [

11,

18,

41,

42]. The menin protein, encoded by the MEN1 gene, negatively regulates β-catenin, underscoring the pathway's importance in NET biology [

43]. The Wnt signaling pathway, essential for gene expression, cell proliferation, and migration during development and cancer, involves 19 Wnt ligands and 10 FZD receptors [

11,

44,

45]. This pathway is divided into canonical and non-canonical categories: canonical signaling involves Wnt proteins binding to FZD receptors and LRP5/6, leading to β-catenin accumulation and gene expression [

11,

46], while non-canonical signaling, not involving β-catenin, activates pathways like Wnt/planar cell polarity, Wnt/receptor tyrosine kinase, and Wnt/calcium, influencing various cellular processes through ligands such as Wnt5a/b and Wnt11 [

11,

47,

48,

49].

Our results indicate no statistically significant differences in LRP6 concentrations between the study and control groups. Currently, no studies investigate the concentration of LRP6 in patients with NETs or in animal models. Existing research on LRP6 is limited to studies involving epithelial cancers, such as colorectal, liver, breast, and pancreatic cancers, often using immunohistochemical tests or bioinformatic analysis [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. The lack of statistically significant differences in LRP6 concentrations, combined with limited research, underscores the need for further studies to understand its role in neuroendocrine tumors. This knowledge gap presents an opportunity for future investigations to provide deeper insights into its potential significance.

Our study also explored potential relationships between protein concentrations and various demographic and clinical factors. In the study group of NETpatients, we observed a significant negative correlation between LRP6 concentrations and the Ki-67 index (p<0.05). The Ki-67 index, a marker of cell proliferation, suggests that lower LRP6 concentrations in tumors with higher Ki-67 indices may indicate that reduced LRP6 concentration is associated with more aggressive, rapidly proliferating tumors. While detailed studies on LRP6 in NETs are lacking, findings from other cancers suggest that LRP6 overexpression may contribute to tumor aggressiveness [

53,

55]. For example, in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), dysregulated pathways, involving LRP6, are associated with tumor growth and progression [

56]. This relationship could be crucial for understanding LRP6’s role in tumor growth and progression, potentially making it a target for therapeutic intervention in highly proliferative NETs [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

The results of our analyses for SFRP3 revealed significant differences between the study and control groups (p<0.001). In-depth comparisons indicated that, both the GEP-NET and BP-NET groups differed from the control group. The BP-NET and GEP-NET groups showed the highest SFRP3 concentrations, with statistically significant differences compared to the control group. Comparing the BP-NET and GEP-NET groups with each other did not yield any significant conclusions. This result suggests a potential role for SFRP3 in the NET development or progression. There are no studies on SFRP3 concentration in NET patients or animal models using immunoenzymatic methods. SFRP3 functions as an inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, crucial for cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [

62]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), SFRP3 overexpression has been shown to inhibit tumor growth by inactivating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [

63]. This leads to reduced cell proliferation and increased differentiation [

64]. Additionally, in rhabdomyosarcoma, particularly the alveolar subtype, the suppression of SFRP3 has been found to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis [

64,

65]. This highlights SFRP3's role in supporting tumorigenesis by modulating the Wnt signaling pathway. Targeting SFRP3 could therefore be a potential therapeutic strategy in cancers where Wnt signaling is dysregulated [

63,

64,

65]. While specific studies directly linking SFRP3 and neuroendocrine tumor proliferation are limited, mechanisms observed in other cancer types suggest that SFRP3 likely influences neuroendocrine tumor growth through similar pathways [

62]. Understanding the role of SFRP3 in these processes could provide insights into new therapeutic approaches for managing highly proliferative neuroendocrine tumors.

DVL1 concentrations varied significantly (p<0.01), with higher concentrations observed in BP-NETs compared to GEP-NETs. For DVL1, only the GEP-NET group had lower concentrations compared to healthy individuals. In this case, the ROC curve analysis enabled the determination of a cutoff point between the GEP-NET and BP-NET groups, demonstrating differences in concentrations between these groups. DVL1 is another critical component of the Wnt signaling pathway in BP-NETs, and its elevated concentration in serum could indicate abnormal activation of this pathway. Such dysregulation may contribute to tumor progression and suggest that the Wnt pathway is functioning in a disrupted manner, potentially influencing cell proliferation and metastasis in NETs. When examining specific primary tumor sites, including the lung, pancreas, small intestine, duodenum, stomach, and rectum, our analysis revealed significant variation in DVL1 concentrations (p<0.01). This indicates that DVL1 concentration is not uniform across different types of neuroendocrine tumors and may reflect the unique biological characteristics of tumors originating in different organs [

66]. Further comparisons between these sites provided more detailed insights. For instance, DVL1 concentrations were significantly different between pancreatic and lung NETs (p<0.05), suggesting that the molecular mechanisms involving DVL1 in pancreatic NETs might differ from those in lung NETs. Similarly, significant differences were observed between small intestine NETs and lung NETs (p<0.05), pointing to distinct regulatory pathways that influence DVL1 concentration. There are currently no studies on the concentration of DVL1 in patients with neuroendocrine tumors, nor have any been conducted using animal models to explore this connection. However, DVL1 has been studied in other types of cancers, suggesting its potential role in cancer biology and signaling pathways, which might be relevant for future investigations in NETs [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]. The variations in DVL1 concentrations across different primary tumor sites could have important implications for understanding the pathophysiology of NETs. For example, the elevated DVL1 concentrations in pancreatic NETs compared to lung NETs might indicate a higher degree of Wnt signaling pathway activation in pancreatic tumors. This could contribute to differences in tumor behavior, such as growth rate, metastatic potential, and response to therapy [

37,

72,

73]. Moreover, these findings highlight the potential of DVL1 as a protein for distinguishing between NETs of different origins. By identifying specific patterns of DVL1 concentration, clinicians could improve the accuracy of NET diagnosis and potentially tailor treatments based on the tumor's primary site [

27,

37,

74].

The significant variation in DVL1 concentrations across different primary tumor sites underscores the complexity of neuroendocrine tumors and the need for a nuanced approach to their study and treatment [

75]. Analyses of DVL1 revealed a moderate negative correlation with chromogranin A (CgA), a well-known marker for NETs (p<0.001). This suggests that as DVL1 concentrations increase, CgA concentrations tend to decrease, highlighting a complex interplay between these molecules. Additionally, weak negative correlations were also found between DVL1 and serotonin (p<0.05) and between DVL1 and 5-HIAA (p<0.05), indicating potential links between Wnt signaling and neuroendocrine function. While no significant associations with age, Ki-67, or clinical stage were found overall, a significant negative correlation between DVL1 and age (p<0.01) was observed in the control group, indicating a possible age-related decline in DVL1 concentration. These findings enhance our understanding of NET molecular diversity and suggest new therapeutic strategies.

These results provide a solid foundation for future research. Further studies should aim to elucidate the precise mechanisms by which SFRP3 and DVL1 contribute to neuroendocrine tumorigenesis. Additionally, investigating these pathways could reveal novel therapeutic targets, ultimately improving patient outcomes. The data presented in this study represent an important step toward a deeper understanding of the molecular underpinnings of neuroendocrine tumors and pave the way for more effective clinical interventions.

5. Conclusions

The study highlights the critical role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the development and progression of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). In conclusion, this study underscores the significant involvement of SFRP3 and DVL1 in the development and progression of neuroendocrine tumors. The elevated serum concentrations of SFRP3 in NET patients, along with the higher DVL1 levels in BP-NETs compared to GEP-NETs, suggest these proteins may play crucial roles in tumor biology. The observed correlations with clinical markers such as chromogranin A, serotonin, and Ki-67 further emphasize their potential relevance. Moreover, the lack of extensive research on these proteins in NETs underscores the need for further studies to elucidate their precise roles. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes. Overall, this research provides a valuable foundation for advancing the molecular understanding of NETs.

6. Advantages of the Study

According to the available data, this is one of the few studies evaluating serum LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1 in NET patients.

7. Limitations of the Study

This study has certain limitations. Notably, no information on patient survival was available, so this data could not be included in the analyses. However, these issues will be addressed in future research. Considering the aim of the study and the fact that the correlations pertain to only one group, and since the purpose of the work is not to predict outcomes between the study and control groups, the authors opted not to perform logistic regression. Instead, Spearman's rank correlation was used to assess the relationships between continuous variables.The study aims to verify the concentrations of IGF-1R, ERK2, and EGFR and to highlight differences in these parameters among patients from the BP-NET and GEP-NET groups as well as a control group of healthy individuals. Due to the limited number of patients in each group, the study does not aim to validate the analyzed parameters.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Description statistics of LRP6, SFRP3, and DVL1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D. and J.K.S.; methodology, R.D. and J.K.S.; software, R.D., E.C. and J.K.S.; validation, R.D., J.S., E.C. and J.K.S.; formal analysis, R.D. and J.K.S.; investigation, R.D.; resources, R.D., J.S. and J.K.S.; data curation, R.D. and J.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.; vis-ualization, R.D. and E.C.; supervision, J.K.S.; project administration, R.D. and J.K.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by a grant from the Medical University of Silesia (BNW-1-032/N/3/O and PCN-1-014/N/1/I).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia (20 September 2022 No. PCN/CBN/0052/KB1/24/II/22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this research are available upon request from corresponding author, d200793@365.sum.edu.pl.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Beata Kos-Kudła Head of the Department of Endocrinology and Neuroendocrine Tumors, Department of Pathophysiology and Endocrinology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Zabrze, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice for enabling the collection of material for study group and Ms. Kinga Wołkowska-Pokrywa, PhD for help with the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander ES, Ziv E. Neuroendocrine Tumors: Genomics and Molecular Biomarkers with a Focus on Metastatic Disease. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Apr 12;15(8):2249. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghișan-Gălățeanu AA, Ilieșiu A, Lambrescu IM, Țăpoi DA. The Complex Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Spectrum of Neuroendocrine Tumors-An Overview of the Latest Classifications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 11;24(2):1418. [CrossRef]

- Sansone A, Lauretta R, Vottari S, Chiefari A, Barnabei A, Romanelli F, Appetecchia M. Specific and Non-Specific Biomarkers in Neuroendocrine Gastroenteropancreatic Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Aug 4;11(8):1113. [CrossRef]

- Gut P, Czarnywojtek A, Fischbach J, Bączyk M, Ziemnicka K, Wrotkowska E, Gryczyńska M, Ruchała M. Chromogranin A - unspecific neuroendocrine marker. Clinical utility and potential diagnostic pitfalls. Arch Med Sci. 2016 Feb 1;12(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Franchina M, Cavalcoli F, Falco O, La Milia M, Elvevi A, Massironi S. Biochemical Markers for Neuroendocrine Tumors: Traditional Circulating Markers and Recent Development-A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Jun 18;14(12):1289. [CrossRef]

- Foltyn W, Malczewska A, Bednarczuk T, Bolanowski M, Chmielik E, Gisterek I, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Junik R, Kajdaniuk D, Kowalska A, et al. Update of the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guidelines for Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (Recommended by the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumours). Endokrynol. Pol. 2022, 73, 387–454. [CrossRef]

- Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning EP, Sundin A, Perren A,, Berruti A. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 844–860. [CrossRef]

- WHO Classifications of Tumours Online. Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/welcome/ (accessed on 10.11.2024).

- Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Brambilla E, Cooper WA, Dacic S, Jain D, Kerr KM, Lantuejoul S, Noguchi M, Papotti M, Rekhtman N, Scagliotti G, van Schil P, Sholl L, Yatabe Y, Yoshida A, Travis WD. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2022 Mar;17(3):362-387. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald BT, Semenov MV, Huang H, He X. Dissecting molecular differences between Wnt coreceptors LRP5 and LRP6. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23537. [CrossRef]

- Jin XF, Spoettl G, Maurer J, Nölting S, Auernhammer CJ. Inhibition of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroendocrine Tumors in vitro: Antitumoral Effects. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Feb 4;12(2):345. [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal Prada ET, Auernhammer CJ. Targeted therapy of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: preclinical strategies and future targets. Endocr Connect. 2018 Jan;7(1):R1-R25. [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei AF, Abu-Elmagd M. LRP6 Receptor Plays Essential Functions in Development and Human Diseases. Genes (Basel). 2022 Jan 10;13(1):120. [CrossRef]

- Jeong W, Kim S, Lee U, Zhong ZA, Savitsky M, Kwon H, Kim J, Lee T, Cho JW, Williams BO, Katanaev VL, Jho EH. LDL receptor-related protein LRP6 senses nutrient levels and regulates Hippo signaling. EMBO Rep. 2020 Sep 3;21(9):e50103. [CrossRef]

- Ng LF, Kaur P, Bunnag N, Suresh J, Sung ICH, Tan QH, Gruber J, Tolwinski NS. WNT Signaling in Disease. Cells. 2019 Aug 3;8(8):826. [CrossRef]

- Azbazdar Y, Karabicici M, Erdal E, Ozhan G. Regulation of Wnt Signaling Pathways at the Plasma Membrane and Their Misregulation in Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Jan 21;9:631623. [CrossRef]

- Koni M, Pinnarò V, Brizzi MF. The Wnt Signalling Pathway: A Tailored Target in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Oct 18;21(20):7697. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald BT, He X. Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012 Dec 1;4(12):a007880. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Shu G, Yin G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Jan 3;7(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Shah K, Kazi JU. Phosphorylation-Dependent Regulation of WNT/Beta-Catenin Signaling. Front Oncol. 2022 Mar 14;12:858782. [CrossRef]

- Yu M, Qin K, Fan J, Zhao G, Zhao P, Zeng W, Chen C, Wang A, Wang Y, Zhong J, Zhu Y, Wagstaff W, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Ho S, Lee MJ, Strelzow J, Reid RR, He TC. The evolving roles of Wnt signaling in stem cell proliferation and differentiation, the development of human diseases, and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dis. 2023 Jul 22;11(3):101026. [CrossRef]

- Oichi T, Otsuru S, Usami Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Iwamoto M. Wnt signaling in chondroprogenitors during long bone development and growth. Bone. 2020 Aug;137:115368. [CrossRef]

- Ng LF, Kaur P, Bunnag N, Suresh J, Sung ICH, Tan QH, Gruber J, Tolwinski NS. WNT Signaling in Disease. Cells. 2019 Aug 3;8(8):826. [CrossRef]

- Grainger S, Willert K. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling and control. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2018 Sep;10(5):e1422. Epub 2018 Mar 30. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Chen J, Liu Y. LRP5 and LRP6 in Wnt Signaling: Similarity and Divergence. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 May 6;9:670960. [CrossRef]

- Pruller J, Figeac N, Zammit PS. DVL1 and DVL3 require nuclear localisation to regulate proliferation in human myoblasts. Sci Rep. 2022 May 19;12(1):8388. [CrossRef]

- Carr HS, Zuo Y, Frost JA. The Wnt pathway protein Dvl1 targets somatostatin receptor 2 for lysosome-dependent degradation. J Biol Chem. 2023 May;299(5):104645. [CrossRef]

- Zeng H, Lu B, Zamponi R, Yang Z, Wetzel K, Loureiro J, Mohammadi S, Beibel M, Bergling S, Reece-Hoyes J, Russ C, Roma G, Tchorz JS, Capodieci P, Cong F. mTORC1 signaling suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling through DVL-dependent regulation of Wnt receptor FZD level. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Oct 30;115(44):E10362-E10369. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009 Jul;17(1):9-26. [CrossRef]

- Melita G, Pallio S, Tortora A, Crinò SF, Macrì A, Dionigi G. Diagnostic and Interventional Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. J Clin Med. 2021 Jun 15;10(12):2638. [CrossRef]

- Tacelli M, Bina N, Crinò SF, Facciorusso A, Celsa C, Vanni AS, Fantin A, Antonini F, Falconi M, Monica F, Capurso G, Arcidiacono PG, Barresi L; of the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists and Endoscopists. Reliability of grading preoperative pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors on EUS specimens: a systematic review with meta-analysis of aggregate and individual data. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Dec;96(6):898-908.e23. [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, I.D.; Odze, R.D.; Klimstra, D.; Paradis, V.; Rugge, M.; Schirmacher, P.; Washington, K.M.; Carneiro, F.; Cree, I.A. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020, 76(2), 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015 Feb 15;121(4):589-97. [CrossRef]

- Rossi RE, Ciafardini C, Sciola V, Conte D, Massironi S. Chromogranin A in the Follow-up of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Is It Really Game Over? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2018 Nov/Dec;47(10):1249-1255. [CrossRef]

- Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, Shih T, Yao JC. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Oct 1;3(10):1335-1342. [CrossRef]

- Evangelou G, Vamvakaris I, Papafili A, Anagnostakis M, Peppa M. Lung NETs and GEPNETs: One Cancer with Different Origins or Two Distinct Cancers? Cancers (Basel). 2024 Mar 17;16(6):1177. [CrossRef]

- Tsoli M, Chatzellis E, Koumarianou A, Kolomodi D, Kaltsas G. Current best practice in the management of neuroendocrine tumors. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Oct 31;10:2042018818804698. [CrossRef]

- Sultana Q, Kar J, Verma A, Sanghvi S, Kaka N, Patel N, Sethi Y, Chopra H, Kamal MA, Greig NH. A Comprehensive Review on Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Presentation, Pathophysiology and Management. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug 5;12(15):5138. [CrossRef]

- La Salvia A, Espinosa-Olarte P, Riesco-Martinez MDC, Anton-Pascual B, Garcia-Carbonero R. Targeted Cancer Therapy: What's New in the Field of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms? Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr 3;13(7):1701. [CrossRef]

- Zhang XB, Fan YB, Jing R, Getu MA, Chen WY, Zhang W, Dong HX, Dakal TC, Hayat A, Cai HJ, Ashrafizadeh M, Abd El-Aty AM, Hacimuftuoglu A, Liu P, Li TF, Sethi G, Ahn KS, Ertas YN, Chen MJ, Ji JS, Ma L, Gong P. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: current development, challenges, and clinical perspectives. Mil Med Res. 2024 Jun 4;11(1):35. [CrossRef]

- Doo DW, Meza-Perez S, Londoño AI, Goldsberry WN, Katre AA, Boone JD, Moore DJ, Hudson CT, Betella I, McCaw TR, Gangrade A, Bao R, Luke JJ, Yang ES, Birrer MJ, Starenki D, Cooper SJ, Buchsbaum DJ, Norian LA, Randall TD, Arend RC. Inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway enhances antitumor immunity in ovarian cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020 Apr 14;12:1758835920913798.

- Choudhary S, Singh MK, Kashyap S, Seth R, Singh L. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Pediatric Tumors: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Children (Basel). 2024 Jun 7;11(6):700. [CrossRef]

- Frost M, Lines KE, Thakker RV. Current and emerging therapies for PNETs in patients with or without MEN1. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 Apr;14(4):216-227. [CrossRef]

- Benoit YD, Guezguez B, Boyd AL, Bhatia M. Molecular pathways: epigenetic modulation of Wnt-glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling to target human cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 Nov 1;20(21):5372-8. [CrossRef]

- Katoh M, Katoh M. Molecular genetics and targeted therapy of WNT-related human diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2017 Sep;40(3):587-606. [CrossRef]

- Katoh M. Canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in cancer stem cells and their niches: Cellular heterogeneity, omics reprogramming, targeted therapy and tumor plasticity (Review). Int J Oncol. 2017 Nov;51(5):1357-1369. [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Sánchez MA, Robles-Flores M. WNT Signaling in Stem Cells: A Look into the Non-Canonical Pathway. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024 Jan;20(1):52-66. [CrossRef]

- Chae WJ, Bothwell ALM. Canonical and Non-Canonical Wnt Signaling in Immune Cells. Trends Immunol. 2018 Oct;39(10):830-847. [CrossRef]

- Čada Š, Bryja V. Local Wnt signalling in the asymmetric migrating vertebrate cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022 May;125:26-36. [CrossRef]

- Shishido A, Miyo M, Oishi K, Nishiyama N, Wu M, Yamamoto H, Kouda S, Wu X, Shibata S, Yokoyama Y, Yamamoto H. The Relationship between LRP6 and Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Colorectal and Esophageal Cancer. Life (Basel). 2023 Feb 23;13(3):615. [CrossRef]

- Rismani E, Fazeli MS, Mahmoodzadeh H, Movassagh A, Azami S, Karimipoor M, Teimoori-Toolabi L. Pattern of LRP6 gene expression in tumoral tissues of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2017;19(2):151-159. [CrossRef]

- Tung EK, Wong BY, Yau TO, Ng IO. Upregulation of the Wnt co-receptor LRP6 promotes hepatocarcinogenesis and enhances cell invasion. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36565. [CrossRef]

- Liu CC, Prior J, Piwnica-Worms D, Bu G. LRP6 overexpression defines a class of breast cancer subtype and is a target for therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Mar 16;107(11):5136-41. [CrossRef]

- Garg B, Giri B, Majumder K, Dudeja V, Banerjee S, Saluja A. Modulation of post-translational modifications in β-catenin and LRP6 inhibits Wnt signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017 Mar 1;388:64-72. [CrossRef]

- Xue W, Zhu B, Zhao K, Huang Q, Luo H, Shou Y, Huang Z, Guo H. Targeting LRP6: A new strategy for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2024 Jun;204:107200. [CrossRef]

- Saleh Z, Moccia MC, Ladd Z, Joneja U, Li Y, Spitz F, Hong YK, Gao T. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Signaling Pathways and Epigenetic Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jan 22;25(2):1331. [CrossRef]

- Hu A, Sun L, Lin H, Liao Y, Yang H, Mao Y. Harnessing innate immune pathways for therapeutic advancement in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Mar 25;9(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Jeong W, Jho EH. Regulation of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein LRP6 and Its Association With Disease: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling and Beyond. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Sep 13;9:714330. [CrossRef]

- Guo Q, Jin Y, Chen X, Ye X, Shen X, Lin M, Zeng C, Zhou T, Zhang J. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Mar 4;9(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Raisch J, Côté-Biron A, Rivard N. A Role for the WNT Co-Receptor LRP6 in Pathogenesis and Therapy of Epithelial Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Aug 13;11(8):1162. [CrossRef]

- Bilic J, Huang YL, Davidson G, Zimmermann T, Cruciat CM, Bienz M, Niehrs C. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2007 Jun 15;316(5831):1619-22. [CrossRef]

- Kephart JJ, Tiller RG, Crose LE, Slemmons KK, Chen PH, Hinson AR, Bentley RC, Chi JT, Linardic CM. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 3 (SFRP3) Is Required for Tumorigenesis of PAX3-FOXO1-Positive Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Nov 1;21(21):4868-80. [CrossRef]

- Fang L, Gao C, Bai RX, Wang HF, Du SY. Overexpressed sFRP3 exerts an inhibitory effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via inactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021 Aug;28(7-8):875-891. [CrossRef]

- Deldar Abad Paskeh M, Mirzaei S, Ashrafizadeh M, Zarrabi A, Sethi G. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling as a Driver of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression: An Emphasis on Molecular Pathways. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021 Nov 25;8:1415-1444. [CrossRef]

- Pal A, Chiu HY, Taneja R. Genetics, epigenetics and redox homeostasis in rhabdomyosarcoma: Emerging targets and therapeutics. Redox Biol. 2019 Jul;25:101124. [CrossRef]

- Mei J, Yang X, Xia D, Zhou W, Gu D, Wang H, Liu C. Systematic summarization of the expression profiles and prognostic roles of the dishevelled gene family in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020 Sep;8(9):e1384. [CrossRef]

- Zeng B, Li Y, Feng Y, Lu M, Yuan H, Yi Z, Wu Y, Xiang T, Li H, Ren G. Downregulated miR-1247-5p associates with poor prognosis and facilitates tumor cell growth via DVL1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018 Oct 20;505(1):302-308. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Yang ZQ, Wang Y, Miao Y, Liu Y, Dai SD, Han Y, Wang EH. Dishevelled-1 and dishevelled-3 affect cell invasion mainly through canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathway, respectively, and associate with poor prognosis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2010 Aug;49(8):760-70. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Li C, Chen X, Zhou Y, Yin B, Ni R, Zhang Y, Liu J. Overexpression of dishevelled 2 is involved in tumor metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017 Dec;19(12):1507-1517. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Tian Y, Du J, Hu Z, Yang L, Liu J, Gu L. Dvl2-dependent activation of Daam1 and RhoA regulates Wnt5a-induced breast cancer cell migration. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37823. [CrossRef]

- Ram Makena M, Gatla H, Verlekar D, Sukhavasi S, K Pandey M, C Pramanik K. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: The Culprit in Pancreatic Carcinogenesis and Therapeutic Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 30;20(17):4242. [CrossRef]

- Alsaggar M, Yao Q, Cai H, Liu D. Differential growth and responsiveness to cancer therapy of tumor cells in different environments. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2016 Feb;33(2):115-24. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Yang Z, Liu W, Zhu W, Yin L, Han Z, Xian Y, Wen J, Tang H, Lin X, Yang Y, Wang J, Zhang K. Disheveled3 enhanced EMT and cancer stem-like cells properties via Wnt/β-catenin/c-Myc/SOX2 pathway in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 2023 May 5;21(1):302. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez RA, Cass AS, Das S, Low SW, Mehrad M, Rickman OB, Scherer PM, Thomas KE, Gillaspie EA. A multidisciplinary approach to the work up and management of pulmonary carcinoid tumors and DIPNECH: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022 Dec;11(12):2567-2587. [CrossRef]

- Eads JR, Halfdanarson TR, Asmis T, Bellizzi AM, Bergsland EK, Dasari A, El-Haddad G, Frumovitz M, Meyer J, Mittra E, Myrehaug S, Nakakura E, Raj N, Soares HP, Untch B, Vijayvergia N, Chan JA. Expert Consensus Practice Recommendations of the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society for the management of high grade gastroenteropancreatic and gynecologic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2023 Jul 11;30(8):e220206. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).