1. Introduction

The past decade has witnessed the transformative impact of artificial intelligence (AI) combined with aerial imagery across various sectors, with the transportation industry standing out as a prominent beneficiary (1, 2). This development has unlocked new potentials for timely design, maintenance, infrastructure management, and the promotion of sustainable transportation systems (3, 4). This development, consequently improving route optimizations and traffic management systems leading to reduced fuel consumptions and improved air quality and subsequently making cycling and walking safer in the environment (5). Recently, the encouragement of bicycle and pedestrian lanes usage across the United States has increased remarkably, driven by a growing recognition of their health, environmental, and mobility benefits (6, 7). Unfortunately, the U.S. has not been particularly outstanding in terms of pedestrian and cyclist usage, partly due to safety concerns and more. A multimodal survey conducted by researchers in (8) highlighted that more than 50% of a sample group agreed that cycling from one place to another within their neighborhood was dangerous. Many urban areas have experienced higher rates of cycling crashes, particularly among lower-income populations, who often rely on bicycles as a primary means of transportation due to economic constraints (6, 7). While urban areas face heightened risks due to inadequate cycling infrastructure, high traffic volumes, and insufficient safety measures (9), rural areas, however, frequently struggle with the development and maintenance of adequate lane infrastructure due to limited financial resources and geographic isolation although have lower traffic densities (10, 11). This lack of resources often results in poorly maintained or absent pedestrian and bicycle pathways, further compromising safety (12).

The recent push for enhanced bicycle and pedestrian lanes aims to address these disparities by improving infrastructure quality and safety measures, thereby fostering a safer and more inclusive environment for all cyclists and pedestrians. This includes investing in protected bike and pedestrian lanes, pedestrian crossings, and traffic calming measures, which are critical for reducing crash rates and encouraging the adoption of non-motorized transportation options across both urban and rural landscapes. It is therefore critical to spatially identify positions of bicycle and pedestrian lanes to enhance various traffic safety studies.

Several Departments of Transportation (DOTs) have made roadway safety a top priority, since the HSM was introduced in 2010, by meeting the safety manual’s standards for roadway geometric data collection (13). However, gathering this data manually across extensive roadway networks poses substantial challenges for many state and local transportation agencies, which need accurate, current data for effective planning, maintenance, design, and infrastructure rehabilitation (14). To overcome these obstacles, DOTs have adopted a range of Roadway Characteristics Inventory (RCI) methods for geometric data collection, such as static terrestrial laser scanning, mobile and airborne LiDAR, satellite imagery, GIS/GPS mapping, photo and video logging and direct field surveys (13). Each of these methods offers specific pros and cons related to cost, accuracy, data quality, labor intensity, storage requirements, time investment, and crew safety. Direct field observations remain common for DOTs and highway agencies when collecting roadway data (14), yet these traditional methods can be slow, hazardous, and impractical under harsh weather conditions. A particular challenge lies in inspecting and maintaining pavement markings, which typically have a service life of only 0.5 to 3 years (15). Road inspectors are often required to perform frequent, manual inspections to monitor these markings, a task that is both labor-intensive and potentially unsafe.

To address these issues, it has become critical to identify alternative approaches that are more efficient for roadway geometric data collection. Recently, researchers have increasingly turned to advanced technologies like computer vision and image processing (13). Satellite and aerial imagery, specifically, have gained popularity as effective tools for gathering geospatial data (13). Images from satellites and aircrafts can be rapidly processed to generate RCI data, providing a timely and detailed view of roadway conditions (16-18).

One example of the most promising aerial imagery and deep learning applications in transportation is the creation of transportation infrastructure inventories (3). State and local agencies have successfully employed these technologies to rapidly assess the condition of extensive road networks, thereby contributing significantly to the enhancement of pedestrian and cyclist safety. There is a pressing need to investigate more efficient alternative methods for gathering roadway geometry data. For example, using SSDs, researchers analyzed aerial imagery captured by drones in real-time to identify and classify road surface defects for instance potholes, cracks, and wear (19). Another study (18) utilized a deep learning algorithm to identify school zones, contributing to safer commuting. This automated approach not only facilitates proactive maintenance by reducing the need for labor-intensive manual inspections but also enables quicker responses to infrastructure deterioration. When models are well-trained, they can notably enhance output accuracy, and it is advantageous economically since this technique requires least to no field costs. While a challenge lies in identifying and extracting small or obscure objects, the recent development in machine learning has mitigated this constraint. Researchers have delved into novel and emerging technologies for the acquisition of roadway inventory data, including computer vision and image processing methods. A critical area of application is the optimization of traffic flow and congestion management (20, 21). By applying deep learning algorithms to aerial imagery, traffic patterns, bottlenecks, and other essential movement insights of people and vehicles can be identified. These developments allow traffic authorities to dynamically adjust traffic signal timings and deploy responsive measures to alleviate congestion. As a result, overall traffic efficiency improves, and both emissions and travel time are reduced (20, 21).

RCI data includes essential roadway elements like pedestrian and bicycle lanes, which are crucial for supporting traffic safety and operations for both state and local transportation agencies. Positioned along roadsides, these markings define specific lanes for pedestrians and cyclists, facilitating traffic flow and ensuring proper positioning, as highlighted in a USDOT study (22). Recognizing this importance, many DOTs have shown a growing interest in using automated methods to detect and evaluate lane markings (23). However, despite their role in enhancing roadway efficiency and reducing crashes, there is currently no comprehensive geospatial inventory of these features across Florida’s state and locally managed roadways. As such, developing new, efficient, and rapid data collection methods is critical. For DOTs, this information is invaluable, supporting objectives like locating faded or outdated markings, comparing the alignment of pedestrian and bicycle lanes with school zones, crosswalks, and turning lanes. Accordingly, crash trends within these areas and intersections can also be analyzed.

To the authors' knowledge, no prior research has created a comprehensive, statewide or county-level inventory of pedestrian and bicycle lanes using high-resolution aerial images and AI-based techniques. This study aims to address this gap by introducing automated tools that leverage deep learning-based object detection models to detect and extract these key roadway elements. Specifically, the study develops a framework based on Multi-task Road Extractor (MTRE) and You Only Look Once (YOLO) models, designed to detect and extract pedestrian and bicycle lane markings from high-resolution aerial images. Primarily, the objective is to create advanced object detection and image processing algorithms to locate and map pedestrian and bicycle lanes across rural counties in Florida using the obtained high-resolution aerial images. Specifically, the research will focus on:

- (a)

developing YOLO and MTRE object detection models,

- (b)

evaluating the performance of the models with ground truth data, and

- (c)

applying the detection models to aerial images to locate and map an inventory of pedestrian and bicycle lanes on Florida’s public roadways.

This initiative is significantly important to USDOT and various transportation agencies for a number of reasons. It plays a key role in improving infrastructure management by enabling the identification of aging or obscured bicycle markings, which are vital for maintaining safe and efficient transportation networks. Furthermore, the ability to automatically extract roadway geometry data that can be easily integrated with crash data and traffic information offers valuable insights to roadway users and policymakers, facilitating better decision-making and enhancing overall transportation safety.

2. Literature Review

Research focused on using artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to extract Roadway Characteristics Inventory (RCI) data, especially concerning pavement markings have significantly increased recently. The influence of deep learning has expanded outside of computer vision into areas like Natural Language Processing (NLP) and generative models (24, 25). The ongoing advancements in deep learning methodologies keep it at the forefront of addressing increasingly complex and varied tasks, thereby advancing machine learning capabilities across different fields. AI approaches, particularly those involving detection models, are crucial for extracting roadway information from remotely sensed data. For instance, several studies have employed aerial imagery and YOLO to identify roadway features (3, 26, 27).

Recent advancements in autonomous driving research have also integrated sensor technology, computer vision methods, and AI techniques to identify pavement markings for vehicle navigation (28-32). Significant improvements in processing and interpreting aerial imagery have been achieved through advancements in CNNs and Single Shot Detectors (SSDs) (33). These models excel in object detection, classification, instance segmentation, and feature extraction tasks. By automating complex analyses, deep learning reduces the need for extensive human labor, thus making the assessment and management of RCI for pedestrians and cyclists timelier and more accurate. Although a lot of study has been done on the use of LiDAR to collect RCI data, this approach has limitations, including high equipment cost, complex and lengthy data processing periods. For example, a study (14) used LiDAR-enabled high-performance computers and precision navigation to create inventories of different roadway components. Other studies have also employed Mobile Terrestrial Laser Scanning (MTLS) to gather information from highway inventory (16). Given the critical importance of pedestrian and bicycle lanes for sustainable mobility and the numerous opportunities that deep learning offers through aerial imagery, this study aims to utilize object detection models to classify and identify cycling and pedestrian lanes in Florida. This approach not only addresses local needs but also offers a globally applicable method for enhancing walking and cycling infrastructure.

Previous research has largely focused on conventional methods for roadway data collection, which often result in long collection times, traffic disruptions, and risks to field crews. In contrast, less attention has been given to advanced technologies like deep learning, object detection and computer vision for capturing roadway geometry elements from high-resolution aerial images. These newer technologies offer advanced solutions by allowing roadway features to be identified from aerial imagery, thereby reducing the need for time-consuming field surveys. This approach not only speeds up data collection but also improves crew safety by minimizing traffic exposure, provides easily accessible data, and enables quick assessment of roadway features over large areas. It is also important to mention that choosing the most effective object detection model involves more than just standardized image collection criteria (34).

2.1. Applying Deep Learning and Computer Vision to Extract Roadway Geometry Features

Human efforts to identify, classify, and quantify features rely heavily on the expertise and experience of specialists. Machine learning aims to mimic this process by using algorithms to process various inputs, make predictions or estimates, and then interpret these as decisions (35). Despite its remarkable advancements, machine learning has not yet achieved the human brain’s level of capability on a one-to-one scale (36, 37). However, it can perform certain tasks that may be challenging for human experts. For more complex problems that traditional machine learning methods cannot address, neural networks—models with many interconnected layers—are employed. This approach, known as deep learning, has multiple layers in the network hierarchy (38-40). Deep learning excels in making refined predictions and estimates by capturing complex, non-linear relationships. It utilizes mathematical techniques, such as the chain rule in differentiation, to backpropagate errors and adjust neuron weights during training (41, 42). Deep learning is a powerful subset of machine learning which achieves superior performance on intricate tasks.

A pivotal moment in deep learning's evolution occurred in 2012 during the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) (43, 44). The deep convolutional neural network AlexNet demonstrated groundbreaking performance, significantly outperforming traditional methods. This success highlighted the exceptional ability of deep learning models, specifically CNNs, in managing complex visual data. AlexNet’s architecture, notable for its depth and multiple convolutional layers, showcased how deep learning could effectively handle and interpret large and intricate image datasets, marking a major advancement in computer vision (45). Building on AlexNet’s foundations, further developments in CNNs and other deep learning techniques, such as SSDs and more advanced network architectures, have continued to enhance our ability to process and interpret visual information (46, 47). CNNs have become the preferred models for many tasks, including object detection, instance segmentation, classification and feature extraction (46, 47). These models automate complex analyses, significantly reducing the need for extensive human labor and improving the efficiency and accuracy of applications such as assessing and managing RCI for pedestrians and cyclists.

Transportation professionals are increasingly recognizing the value of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) as powerful tools in advanced computer vision and deep learning (48). These methods have demonstrated effectiveness in rapidly recognizing, detecting, and mapping roadway features across large areas without human involvement. Recent advancements in CNNs have underscored their strength in object detection, with notable progress from region-based CNNs (R-CNN) to Fast R-CNN (49) and, ultimately, Faster R-CNN (50). The CNN process begins by calculating features from region proposals that indicate possible object locations, while Faster R-CNN optimizes this by introducing a Region Proposal Network (RPN) to enhance detection performance further.

Studies have applied CNNs across various transportation contexts. For instance, CNNs have been used to recognize roadway geometry and detect lane markings in inverse perspective-mapped images (30). Another study utilized CNNs to identify, measure, and map geometric attributes of concealed road cracks via ground-penetrating radar (51). Additionally, CNNs have extracted roadway features from remotely sensed images (52), and this approach is used in applications like enabling autonomous vehicles to identify objects and infrastructure in real time. In a study using Google Maps photogrammetric data, CNNs were employed to detect pavement marking defects on roads, achieving an accuracy of 30% using R-CNN to identify defects such as misalignment, ghost markings, fading, and cracks (15). Further comparisons of machine learning models have shown that Faster R-CNN outperforms Aggregate Channel Features (ACF) in vehicle detection and tracking (53). In other research, ground-level images were analyzed using ROI-wise reverse reweighting combined with multi-layer pooling operations in Faster R-CNN to detect road markers, achieving a 69.95% detection accuracy by focusing on multi-layered features (54). Another study introduced a hybrid local multiple CNN-SVM system (LM-CNN-SVM) using Caltech-101 and Caltech pedestrian datasets for object and pedestrian detection (55). This system divided full images into local regions for CNNs to learn feature characteristics, which were then processed by multiple support vector machines (SVMs) using empirical and structural risk reduction. This hybrid model, integrating a CNN architecture with AlexNet and SVM outputs, yielded an accuracy range between 89.80% and 92.80%.

2.2. Obtaining Roadway Geometry Data through Aerial Imagery Techniques

Aerial imagery offers significant advantages over traditional ground-based survey methods, such as total stations, Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), dash cams, and mobile laser scanning (56). Firstly, aerial imagery can be quickly obtained due to availability of fully automated image processing methods. Additionally, it provides a broader and more comprehensive view of a study area. Unlike ground-based methods, which often capture data from limited vantage points and prone to blind spots or incomplete coverage, aerial imagery can cover extensive geographic regions in a single pass (2). This extensive coverage allows for the simultaneous assessment of various infrastructural elements, including road networks, pedestrian walkways, and surrounding landscapes, which would otherwise require multiple ground-based surveys (57). Furthermore, aerial surveys mitigate many logistical challenges associated with ground-based methods, such as accessing remote or hazardous locations, thus reducing risks to survey crews and minimizing traffic disruptions. Road markings are highly suitable for extraction from images due to their reflective properties. In one study (58), researchers applied a CNN-based semantic segmentation technique to detect highway markers from aerial images. This approach introduced a new process for handling high-resolution images by integrating a discrete wavelet transform (DWT) with a fully convolutional neural network (FCNN). By utilizing high-frequency information, the DWT-FCNN combination improved lane detection accuracy. Another study (59) developed an algorithm to identify and locate road markings using pixel extraction from images taken by vehicle-mounted cameras. This method used a median local threshold (MLT) filtering technique to isolate marking pixels, followed by a recognition algorithm that classified the markings based on shape and size. The system achieved an average true positive rate of 84% for detected markings.

Aerial imagery significantly improves efficiency and data accuracy compared to traditional ground-based techniques. Ground-based surveys, such as those using total stations and GNSS, often involve lengthy setup times, precise alignment requirements, and manual data collection, making them time-consuming and labor-intensive (3, 56). While dash cams and mobile laser scanning offer advanced capabilities, they still depend on vehicle mobility and can be affected by obstructions, traffic conditions, and varying light levels (60). In contrast, aerial imagery, captured by drones or aircraft equipped with high-resolution cameras, can swiftly cover large areas with consistent accuracy, unaffected by terrestrial obstructions. This makes aerial imagery the most suitable technology for capturing geographic information within a given timeframe (61). Advanced processing techniques, such as stereo-photogrammetry and orthorectification, convert these images into precise geospatial datasets, allowing for accurate measurement and analysis of surface features (62). Compared to most publicly available satellite imagery, modern aerial imagery provides detailed geospatial datasets due to its near sub-decimeter resolution (63, 64). This high level of detail facilitates a more accurate assessment of infrastructure conditions, land use patterns, and potential safety hazards, thereby offering timelier information for informed decision-making and planning (65, 66).

In one study (14), researchers used a two-meter resolution aerial imagery and six-inch accuracy LiDAR data to collect and store roadway data in ASCII text files format. They used ArcView to integrate height data into LiDAR point shapefiles and transformed these points into Triangular Irregular Networks (TIN). The analysis involved merging the aerial photographs with LiDAR boundaries to create a cohesive dataset. Another study (67) introduced a deep learning algorithm using 3D pavement profiles collected via laser scanning, to automate the identification and extraction of road markings, reaching a 90.8% detection accurac. This method used a step-shaped operator to locate potential edges of pavement markings, followed by a CNN that combined geometric properties with convolutional data for accurate extraction. Additionally, in study (68), computer vision techniques were applied to assess pavement conditions and extract markings from camera images. Videos captured from a vehicle’s forward-facing perspective were preprocessed, and a hybrid detector using color and gradient attributes was used to locate markings. These were then identified through image segmentation and classified as edge lines, dividers, barriers, or continuity lines based on their properties. In this study, image processing techniques, along with YOLO and MTRE models, will be applied to extract pedestrian and bicycle lane features from high-resolution aerial images, focusing specifically on Leon County, Florida.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, no research has yet explored the creation of a comprehensive inventory of pedestrian and bicycle lane markings on a county- or state-wide scale using integrated image processing and AI techniques with very high-resolution aerial images. This study aims to address this gap by developing automated methods for identifying these markings on a large scale from high-resolution images. Specifically, the research will focus on developing AI models based on MTRE and YOLO methodologies.

3. Study area

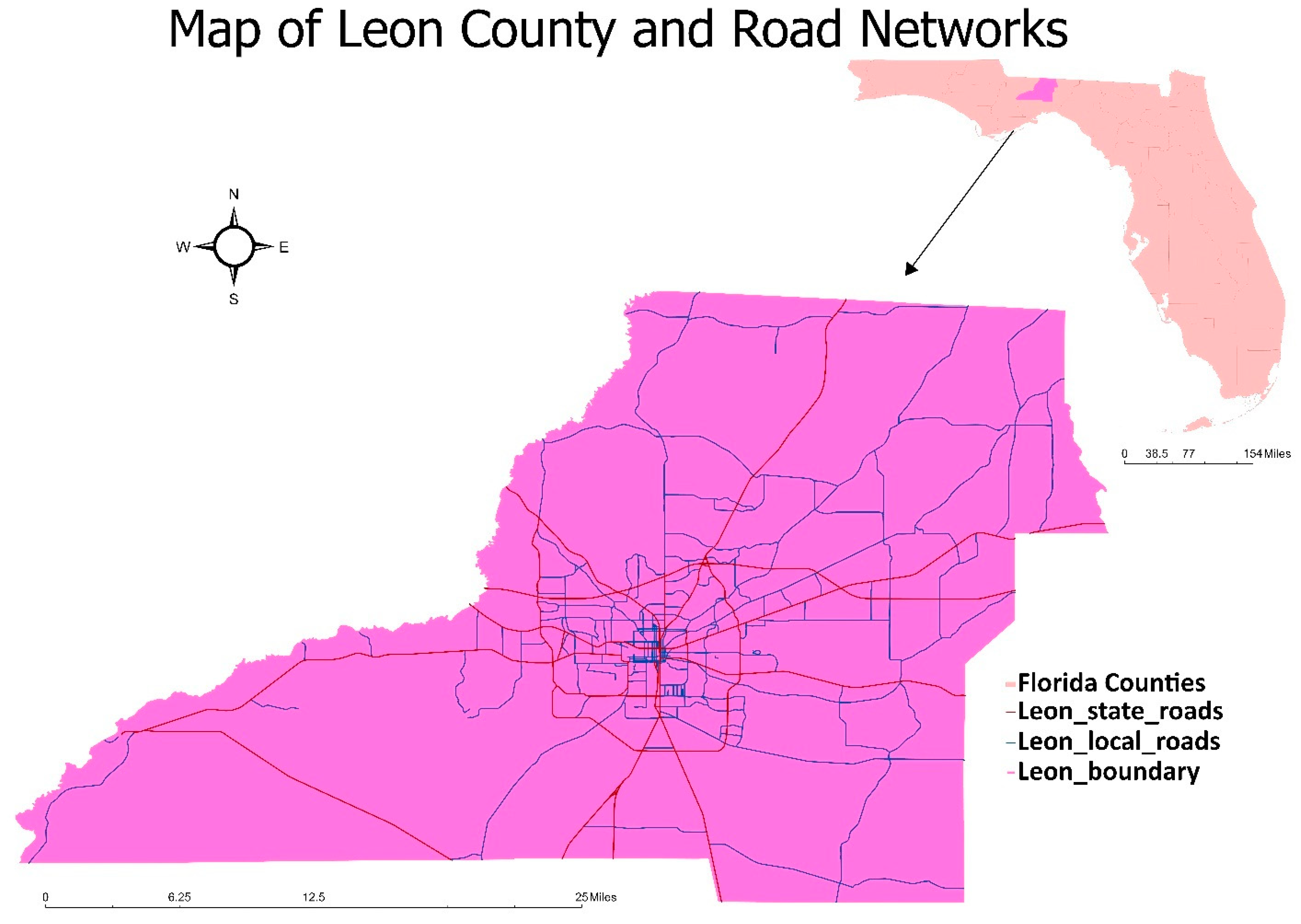

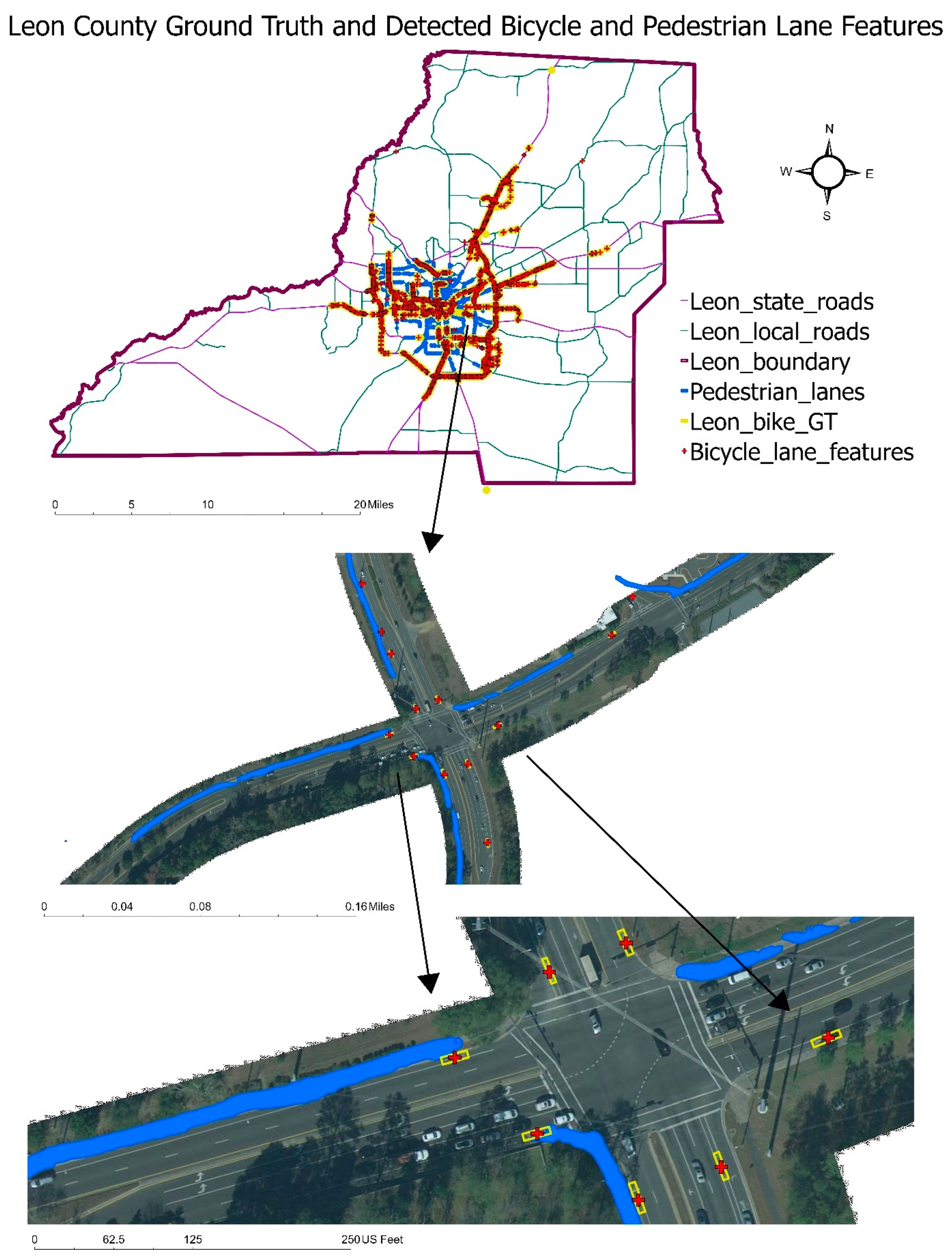

The study area for bicycle and pedestrian lanes detection is Leon County, Florida (

Figure 1). The population of the residents in Leon County is 292,198. It is home to the City of Tallahassee, the capital city of Florida, with a total size of 668 square miles

(69). Leon County shares boundaries with other Florida counties such Gadsden, Wakulla, Liberty, and Jefferson as well as Georgia's Grady and Thomas counties. Leon county was considered because of the variation of its roadway infrastructure development. The developed models' performances were validated using ground truth data collected from Leon County.

4. Materials and methodology

The choice of methodology for collecting roadway inventory data depends on several factors, such as the time required for collection of data, reduction, and processing, as well as the associated costs and demands for accuracy, safety, and data storage. This study focuses on developing single-class object detection models using YOLO and MTRE. The goal is to automatically detect and compile a geocoded inventory of bicycle and pedestrian lanes from high-resolution aerial images across counties in Florida.

4.1. Data Description

This study aims to detect bicycle and pedestrian lanes on roadways managed by state, county, and city agencies, excluding interstate highways. According to the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) classification, state highway system roads are categorized as "ON system roadways," while roads under county and city jurisdiction are designated as "OFF system roadways" or local roads. The methodology integrates centerline data from shapefiles of both local and state-managed roads, leveraging this information to enhance lane detection. While FDOT’s GIS database provides key geometric data points for mobility and safety analysis, it does not include the specific locations of bicycle and pedestrian lanes on local roads. To address this gap, this research applies an advanced object detection model to inventory bicycle and pedestrian lane markings, with an initial focus on Leon County, Florida.

The detection algorithm utilizes high-resolution aerial imagery and state-of-the-art advancements in computer vision and object detection. The objective is to automate the identification of bicycle lane markings and segment pedestrian lanes based on their reflectance properties, offering a practical solution for transportation agencies. Aerial imagery for the study was sourced from the Florida Aerial Photo Look-Up System (APLUS), maintained by FDOT’s Surveying and Mapping Office. Images from Sarasota (2017), Hillsborough (2017), Gilchrist (2019), Gulf (2019), Leon (2018), and Miami-Dade (2017) counties were analyzed. With resolutions ranging from 0.25 feet to 1.5 feet, these images provided sufficient detail for accurate detection of pedestrian and bicycle lanes. The majority of the images had a resolution of 0.5 feet per pixel, with dimensions of 5000x5000 and a 3-band (RGB) format, although specific resolutions varied by county. The imagery was supplied in MrSID format, enabling GIS projection onto maps and facilitating spatial analysis. State and local roadway shapefiles from FDOT’s GIS database further enriched the dataset used in the detection algorithm. Notably, the model’s resolution requirement allows it to process any imagery that meets or exceeds the specified resolution threshold. This integration of aerial imagery and GIS data ensures a robust framework for identifying bicycle and pedestrian lanes and addressing a critical data gap for transportation agencies.

4.2. Pre-processing

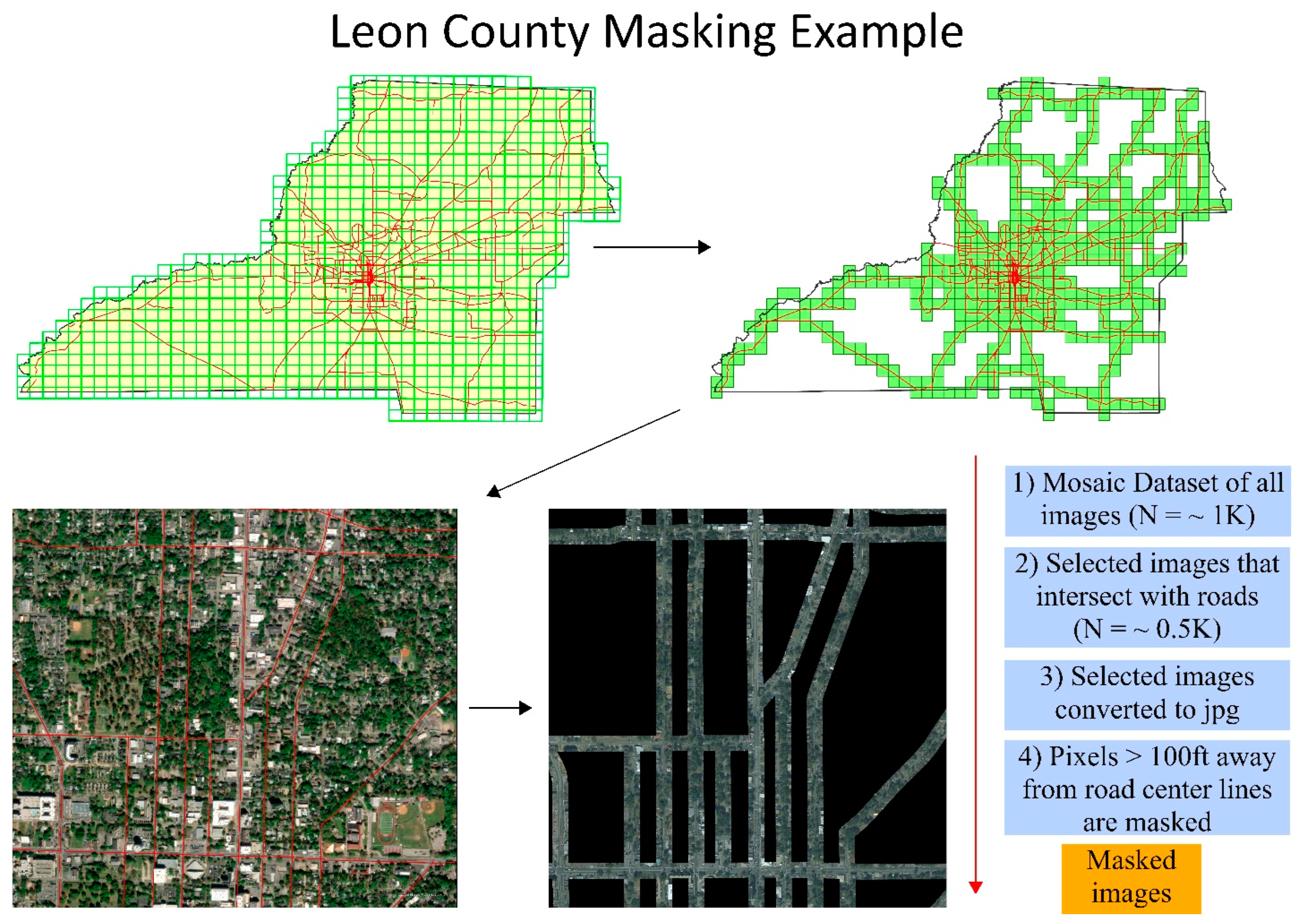

Preprocessing is a crucial step in managing large datasets and meeting the complex demands of object recognition. The process begins by filtering out images that do not intersect with roadway centerlines and masking regions outside a designated buffer zone. Specifically, objects located more than 100 feet from state and local roadways are excluded (

Figure 2). This step reduces the dataset size and narrows the analysis to relevant areas. A buffer is first applied to the roadway shapefile, generating overlapping polygons that act as reference zones for cropping intersecting regions in the aerial images. Pixels lying outside this buffer are masked, producing cropped images with fewer pixels for streamlined analysis. These cropped images are then mosaiced into a single raster file to facilitate data management.

The workflow involves importing aerial imagery from selected counties into a mosaic dataset within ArcGIS Pro. These geocoded images are organized and visualized in the mosaic database, enabling intersections with vector data to identify specific image tiles by location. From this dataset, only images intersecting roadway centerlines are extracted for further processing. An automated masking tool, developed using ArcGIS Pro’s ModelBuilder, applies a 100-foot buffer around the roadway centerlines and processes each image systematically. The masked outputs are saved as JPG files, optimized for the subsequent object detection phase. These final exported images undergo additional preparation for model training and detection tasks, ensuring compatibility with advanced recognition algorithms.

4.3. Data Preparation for Model Training and Evaluation

High-resolution image data is essential for effectively training deep learning models to detect various features. The image preparation process involves identifying features, extracting training data, and generating labels. Considerable time and effort were devoted to creating a robust training dataset, as model performance largely depends on the quality, quantity, and diversity of this data. Also, significant effort went into model training, which involved testing various parameters to determine the most effective ones.

In the initial phase, single-class object detection models were developed to identify bicycle and pedestrian lanes specifically. The training data consisted of “bicycle” and “pedestrian” classes, annotated by rectangular bounding boxes around the respective features (

Table 1). For YOLO and MTRE models, a total of 8,628 bicycle features and 8,766 pedestrian features were manually labeled on aerial images from Miami-Dade, Sarasota, Hillsborough, Gulf, and Gilchrist counties using ArcGIS Pro’s Deep Learning Toolbox. To enhance data diversity, augmentation techniques like rotation were applied, rotating training data at various angles (e.g., 90 degrees) to help the model identify features in different orientations. Ultimately, 26,728 image chips with 32,852 bicycle features and 18,792 image chips with 32,023 pedestrian features were collected for training detection model. Metadata for the labels, including information such as image chip size, object classes, and bounding box dimensions, was stored in XML files. Bicycle and pedestrian data were formatted according to the Pascal Visual Objects and Classified Tiles standards, respectively. To facilitate compatibility with YOLOv5, a custom function was developed to convert the bicycle model metadata. This function recalculated the bounding box center coordinates, width, and height to align with the YOLOv5 format requirements. The bounding box coordinates were normalized according to the image dimensions, maintaining accuracy relative to the input image. The original metadata in Pascal Visual Objects format was converted to YOLOv5 format before final training. High-resolution aerial images from selected Florida counties, with tile sizes ranging from 5,000x5,000 to 10,000x10,000 square feet, served as the input mosaic data.

4.4. YOLOv5 and MTRE Detection Models

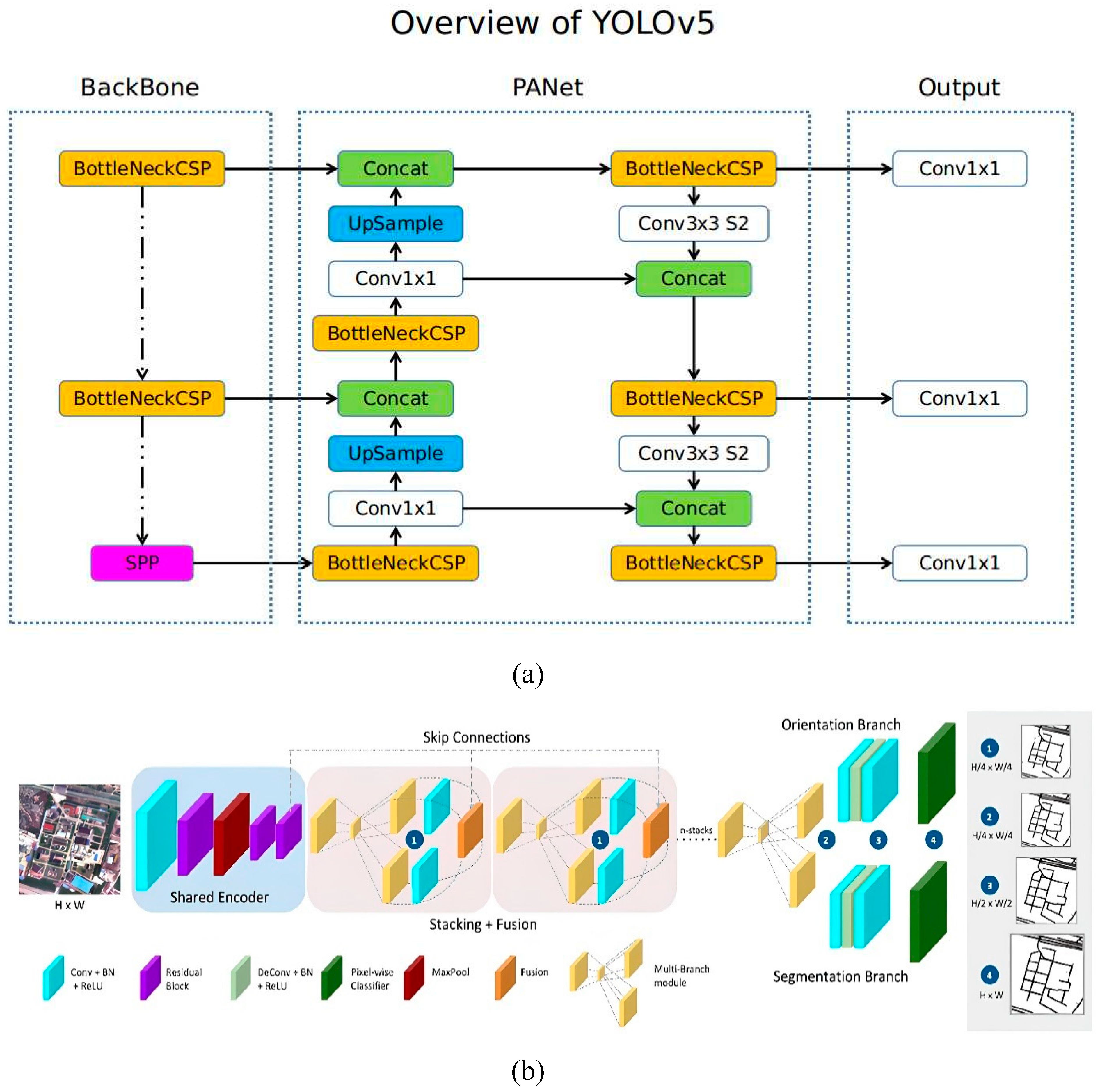

The You Only Look Once (YOLO) model is widely used for its remarkable speed and efficiency in real-time object detection, making it a popular choice over models like R-CNN and Faster R-CNN. Unlike these architectures, which first classify image regions before identifying objects, YOLO processes the entire image in a single network evaluation. This streamlined approach enables YOLO to be significantly faster, outperforming R-CNN and Faster R-CNN by factors of 1,000 and 100, respectively (70). Since its introduction in 2016 (71), YOLO has undergone continuous improvement across multiple versions. YOLOv2 (72) and YOLOv3 incorporated multi-scale predictions to enhance detection capabilities. More recent iterations, YOLOv4 (2020) and YOLOv5 (2022), have further advanced both speed and accuracy, cementing YOLO’s status as a leading tool in object detection (73, 74). The YOLOv5 architecture is composed of three main components: the backbone (CSP-Darknet), the neck (Path Aggregation Network, or PANet), and the head (output layer). YOLOv5’s backbone uses a Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) network—an improved version of YOLOv3’s Darknet-53 backbone—which achieves higher accuracy and processing speed (74). Its backbone and 6x6 convolution structure increase the model's efficiency, allowing the feature extractor to outperform previous YOLO versions and other models in terms of speed and precision (75, 76). YOLOv5 achieves a level of accuracy and speed that is double that of ResNet152 (70). The model incorporates multiple pooling and convolution layers, enabling feature extraction at different levels using CSP and Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) to detect varied object sizes within an image (77).

YOLOv5’s design reduces computational complexity significantly through its BottleneckCSP structure, which optimizes inference speed, and SPP, which extracts features across different image regions to create three-scale feature maps that improve detection quality. The model’s neck, a series of layers between the input and output, uses Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) and PAN structures. FPN passes high-level semantic features to lower feature maps, while PAN conveys accurate localization features to higher feature maps. This multi-scale detection process culminates in the output head, which generates target predictions across three distinct feature map sizes

(77).

Figure 4a illustrates YOLOv5’s architecture, showing how the model applies a 1x1 detection kernel on feature maps at three scales within the network.

In addition to YOLOv5, the MTRE framework, based on a CNN architecture, supports two configurations: LinkNet and Hourglass. For this study, the MTRE model’s Hourglass architecture with a ResNet50 backbone was utilized

(78). The framework consists of three main components: the shared encoder, the stacking and fusion block, and the prediction heads (

Figure 4b). The stacking and fusion block progressively combines segmentation and orientation predictions, while the prediction heads include separate branches for each task. By integrating intermediate predictions at smaller scales, the Hourglass architecture enhances information flow between tasks, ultimately improving segmentation and orientation accuracy across the model.

Figure 4.

The network architecture for (a) YOLOv5, adapted from (74) and MTRE, adapted from (78).

Figure 4.

The network architecture for (a) YOLOv5, adapted from (74) and MTRE, adapted from (78).

4.5. Bicycle and Pedestrian Lane Detectors

The adjustable parameters and hyperparameters in the object detection model include factors like batch size, training-test data split, epochs, input image dimensions, learning rate, anchor box sizes and ratios. The evaluation metrics were visualized using training loss, validation loss, precision, F1, confidence and recall graphs, and confusion matrices. Validation loss and mean average precision (mAP) were computed using a validation dataset that represented 15% of the total input data. The learning rate controls how quickly the model adapts during training, balancing convergence speed with detection precision.

In this study, learning rates of 3.0e-4 and 8.3e-4 were chosen for the YOLO and MTRE models, respectively, to achieve optimal performance. Batch size, which determines the number of samples processed per iteration, was set to 64 for training the bicycle lane model to ensure efficient processing. However, due to memory limitations, a batch size of 20 was used for the pedestrian lane model. Larger batch sizes enable faster computation but demand more memory, while smaller batch sizes add randomness, potentially improving generalization to new data. Anchor boxes, which define the size, shape, and position of detected objects, were initialized with four sizes for training the YOLO model. The number of epochs, representing the total passes through the entire training dataset, was fixed at 100 for this study. For data partitioning, 70% of the input dataset was allocated for training, while the remaining 30% was split between validation (15%) and testing (15%) to assess the model’s performance. Metrics such as precision, F1, accuracy, and recall were computed using the test set after training. The data split ratio was adjusted based on dataset size; for datasets exceeding 10,000 samples, allocating 20–30% for validation provided a sufficient randomized sample for robust evaluation. Predictions were deemed valid if there was at least 50% overlap between the detection and label bounding boxes. Precision and recall metrics were calculated to quantify detection accuracy relative to both the ground truth labels and all predicted outputs. During YOLO model training, binary cross-entropy loss was used for classification, replacing mean square error. This allowed the use of logistic regression for predicting object confidence and class labels, reducing computational overhead while improving performance. In YOLOv5, the total loss function integrated class loss, object confidence loss, and box location loss, enhancing the model’s efficiency and detection capabilities

(70, 74):

where the overall

function is composed of three main components: classification loss,

, the object confidence loss,

, the location or box loss,

. These components are weighted by factors

,

,

respectively which balance the contribution of each loss type to the overall model optimization. The grid size, denoted by

, represents the division of the input image into

grid cells while

indicates the number of bounding boxes predicted per each grid cell. The probability of an object belonging to a specific category is represented by

, and

refers to the probability of a classification error. Key geometric terms include

, which is the diagonal distance of the smallest enclosing area that contains both the predicted box and the ground truth box, and

the confidence score for a prediction. The term

represents the intersection between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box. The intersection over union ,

measures the overlap between these two boxes, providing a critical evaluation metric for localization accuracy. Additional parameters include

, which calculates the Euclidean distance between the centroids of the predicted and ground truth boxes.

denote the center points of the predicted and ground truth boxes, respectively. The aspect ratio consistency is evaluated using

, which considers the target and predicted aspect ratios,

and

. The positive trade-off parameter

helps balance the competing objectives within the loss function. Lastly,

is a weight that penalizes classification errors in grid cells without objects.

The loss function for MTRE model is the sum of the segmentation loss and orientation loss

(78):

where

is the total loss,

is the segmentation loss,

is the orientation loss.

is the scale, and

is the number of bins in the orientation. Let

be a labeled sample from the dataset,

represent the prediction function of the model, and

and

are refined predictions for the roads and orientation respectively.

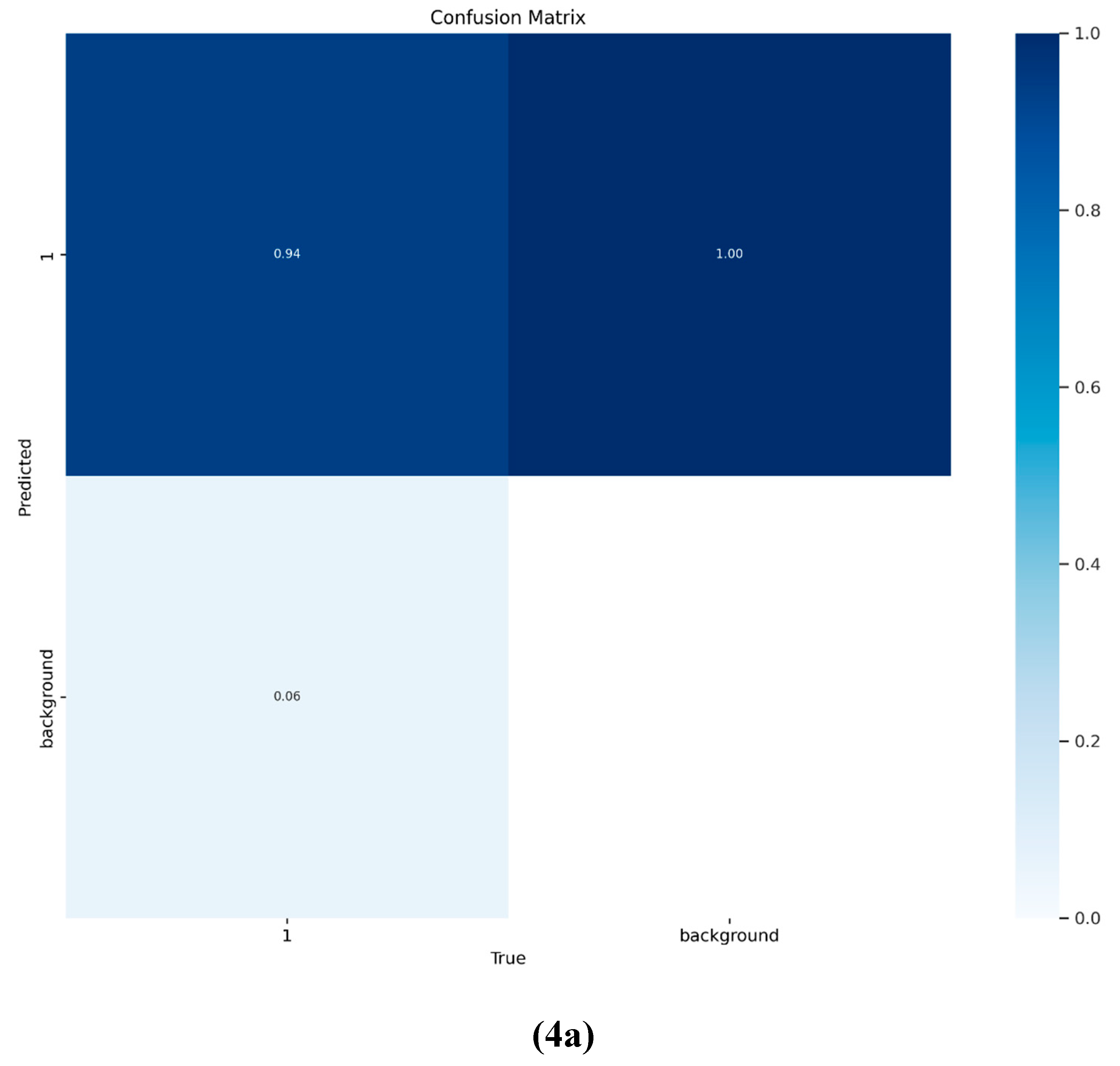

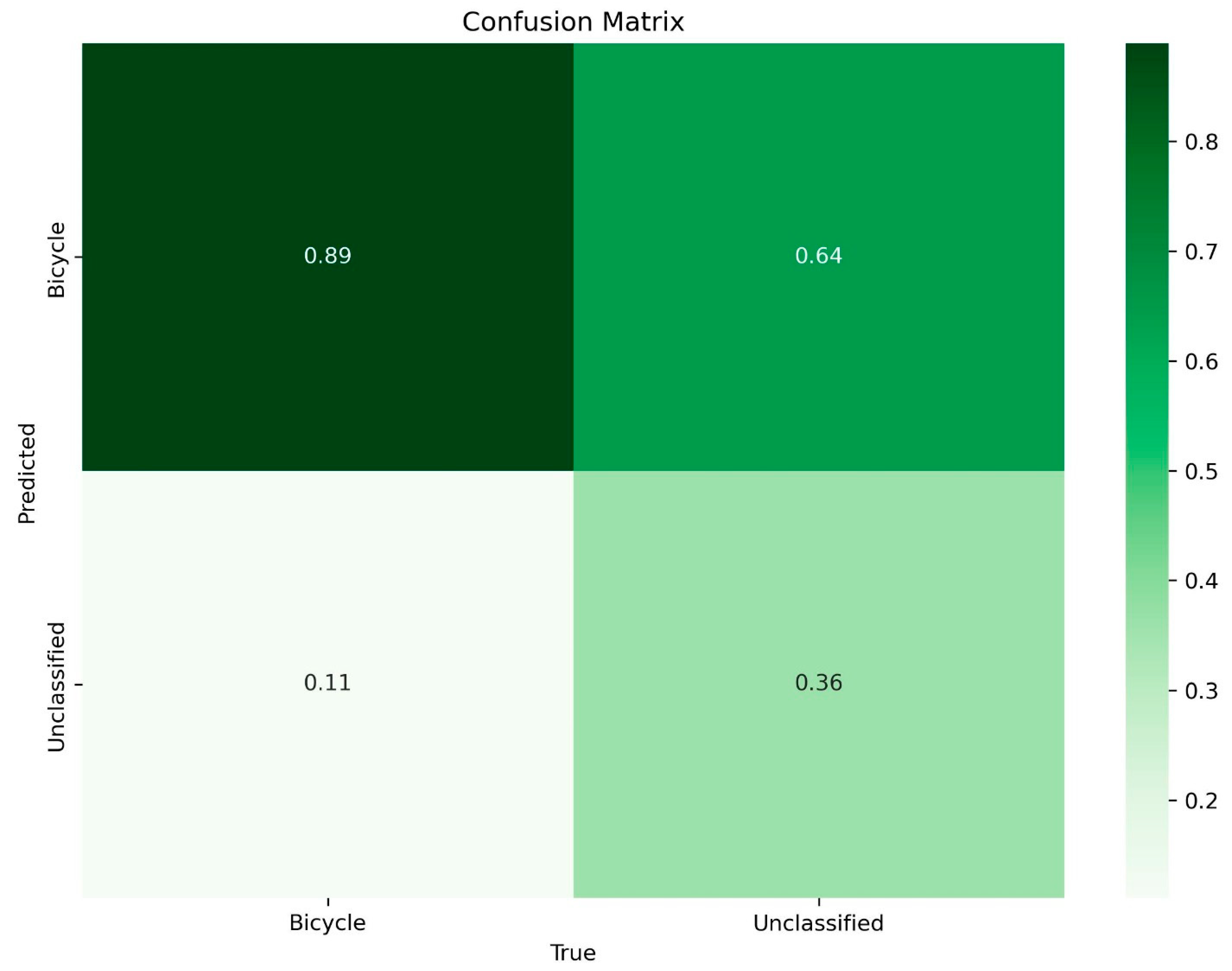

Following the training process, the model's performance was evaluated. For the YOLO model, metrics such as precision-recall, confusion matrix, , validation and training loss, and F1-confidence were used. The MTRE model was assessed using metrics including IoU, accuracy, dice/F1 score, and training and validation loss. The confusion matrix provided insights into the model's true positive rate and misclassification rate. Notably, the diagonal of the matrix showed a high rate of true positive predictions for the bicycle feature class (

Figure 4a). A distinct background class was also observed, representing areas where no objects were detected. This accounted for regions in the dataset with no identifiable features, and the model exhibited very few unclassified features overall.

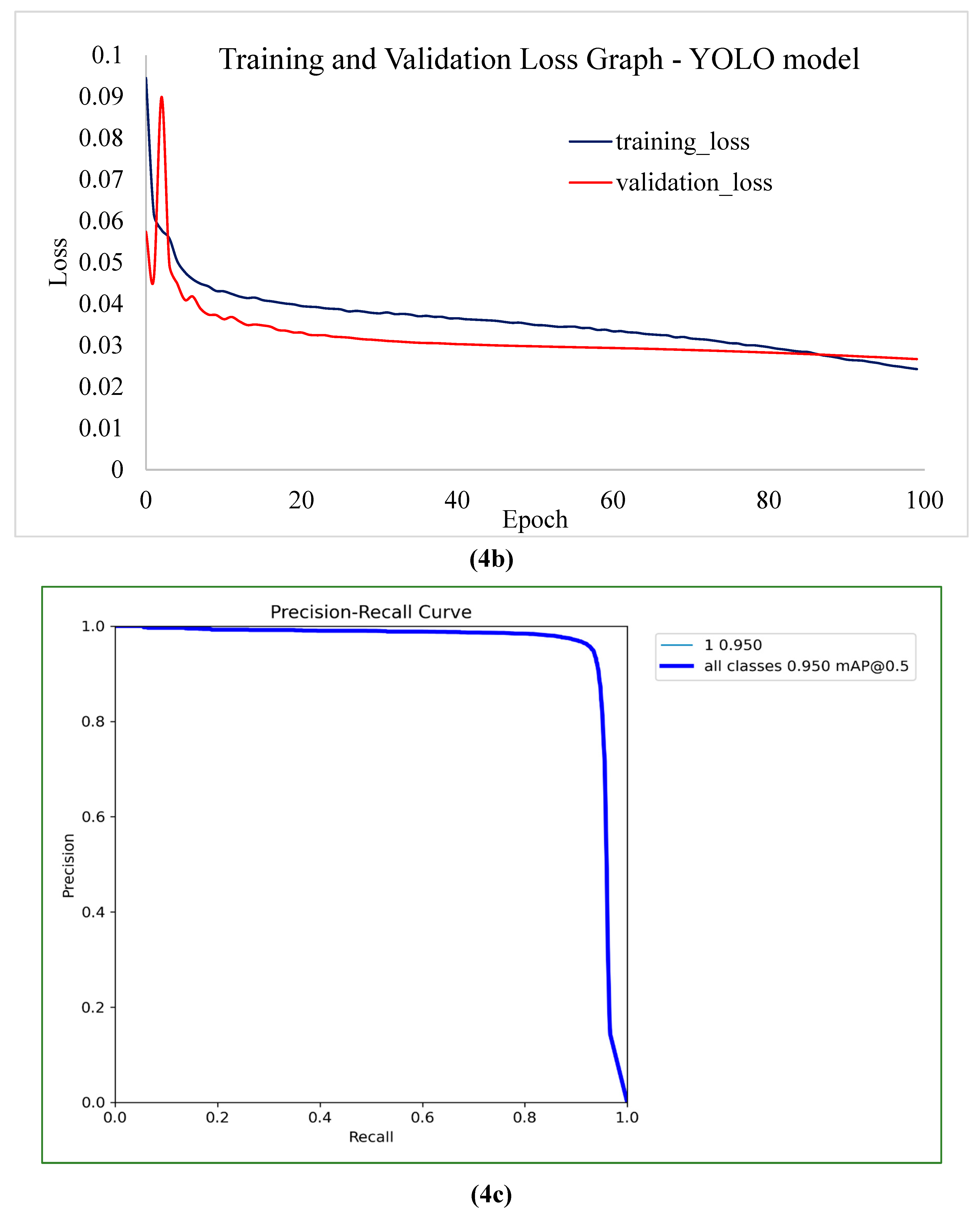

Figure 4b illustrates the training-validation loss curve for the YOLO model. Training loss measured the model’s fit to the training data, while validation loss indicated its performance on the validation dataset. A high loss suggested greater errors, whereas a low loss reflected better accuracy and lesser errors. Throughout the training process, the YOLO model demonstrated a minimal difference between training and validation loss. Initially, training loss was slightly higher, but by the end of the process, validation loss marginally surpassed training loss. This trend indicates that the YOLO model is highly accurate, performing slightly better on the training data than the validation set. The precision-recall curve for the YOLO model, shown in

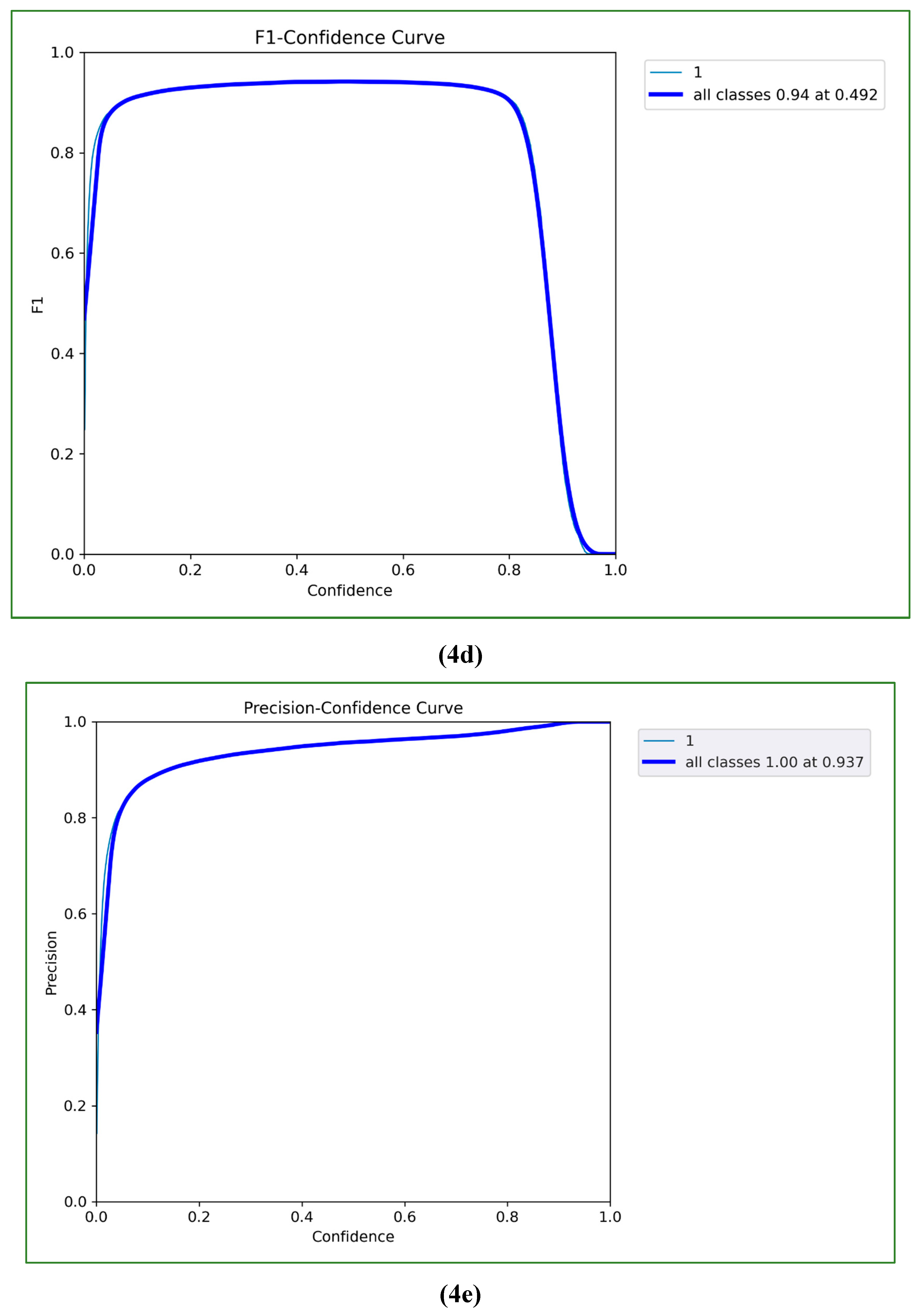

Figure 4c, highlights its sensitivity in identifying true positives and its ability to predict positive values accurately. A robust classifier exhibits high precision and recall across the curve. The YOLO model achieved a precision of 0.958 and a recall of 0.927, indicating strong performance. The F1 score, calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, serves as a critical metric for evaluating model effectiveness. Higher F1 scores correspond to better performance. From the F1-confidence curve (

Figure 4d), the YOLO model performed exceptionally well, achieving an F1-score between 0.90 and 0.97 when the confidence threshold ranged from 0.05 to 0.8. An optimal threshold of 0.49 yielded an F1 value of 0.94 for the bicycle class. The precision-confidence curve, depicted in

Figure 4e, revealed that precision steadily increased with higher confidence thresholds. Even at a confidence level of 0.2, the model demonstrated strong precision, peaking at an ideal precision value of 0.94. Overall, the developed YOLO model achieved an accuracy of 0.950, showcasing its high precision and reliable performance in detecting bicycle features.

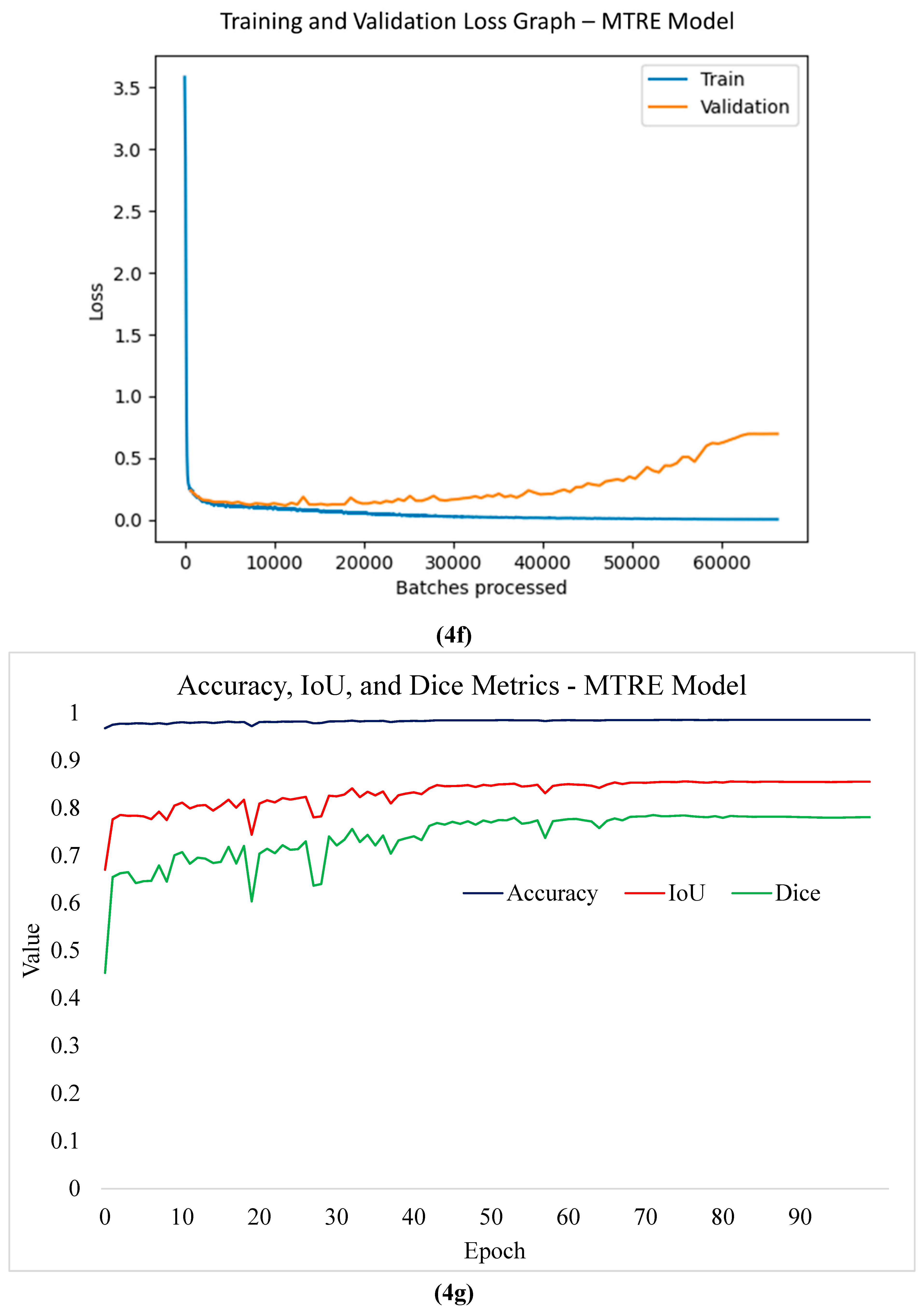

The train-validation loss for the MTRE model is shown in

Figure 4f. It can be observed from the graph that the validation data was higher that the training data, indicating better performance with training data. The IoU metric is the area of intersection divided by the area of the union. This measures the ratio of how much of the predicted area that falls within the ground truth area and the union of the two. On the other hand, the dice coefficient is two times the intersection between the prediction and ground truth areas divided by the sum of the prediction and ground truth areas. In segmentation tasks, the dice is also referred to as the F1 value. The value is 1 when there is a 100% overlap and 0 when there is a 0% overlap between the prediction area and ground truth area. The IoU of the MTRE model is 0.856, the dice is 0.781 whereas the accuracy is 0.985.

Figure 4g shows a graph of the accuracy, IoU, and the dice coefficients. Therefore, we can conclude that the developed bicycle feature and pedestrian lane detectors performs quite well.

4.6. Mapping Bicycle and Pedestrian Lanes

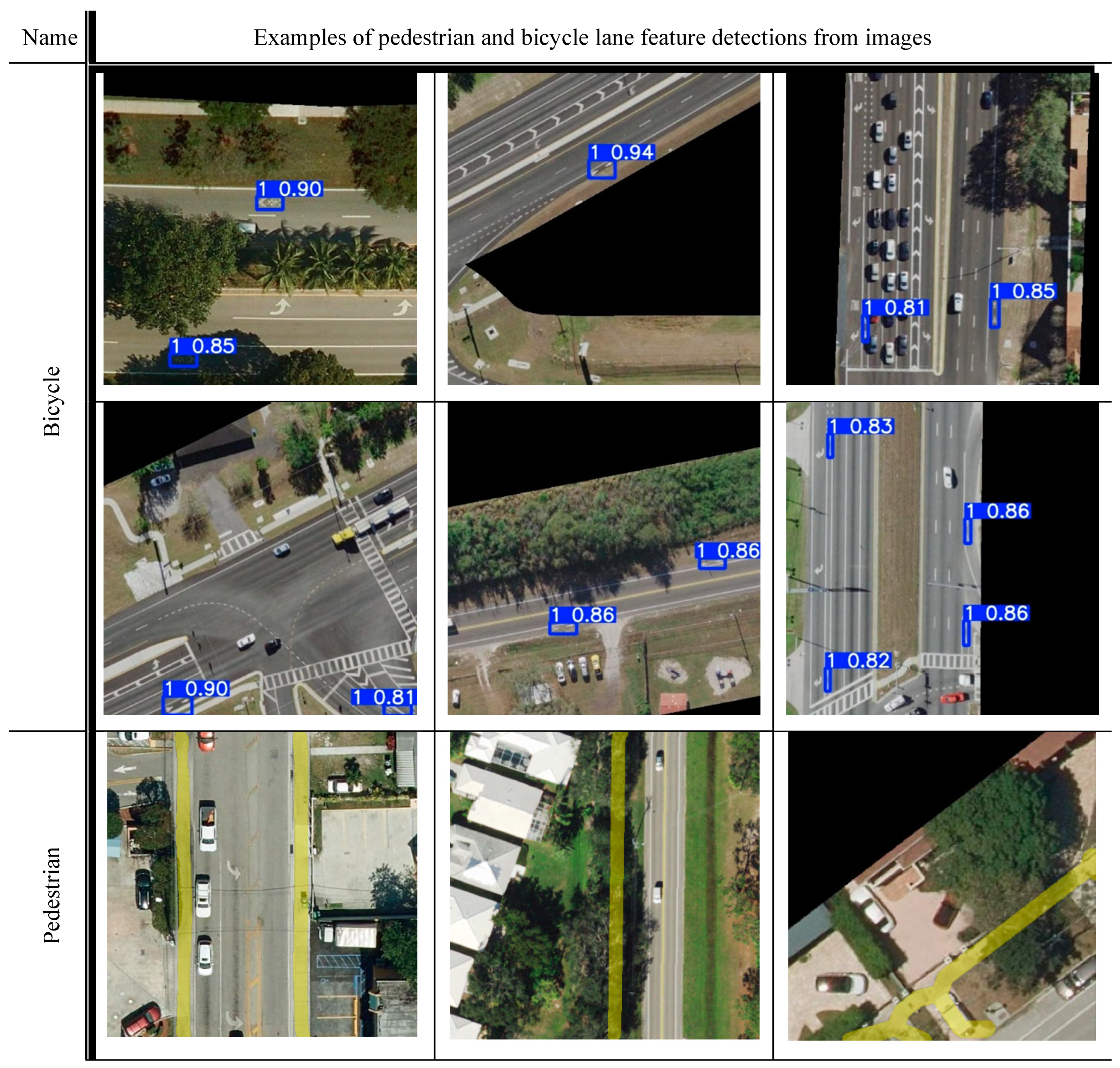

The bicycle and pedestrian lane detectors were initially tested on individual images.

Figure 5 shows the YOLO detector accurately identifying bicycle lane features with bounding boxes based on the confidence score, while also segmenting pedestrian lanes within the images. A confidence threshold of 0.1 was set to ensure the detection of all features, including those with very low confidence scores. While this approach enhances the model's ability to identify faint or partially visible features, thereby improving recall and reducing missed detections, it comes with trade-offs. Lowering the detection threshold increases the likelihood of false positives, which can negatively impact precision. Additionally, it raises computational demands and prolongs detection time by introducing irrelevant features or noise into the analysis. To avoid duplicate detections, overlapping bounding boxes with more than 10% overlap were minimized. The detectors were trained on sub-images with a resolution of 512 x 512 pixels at 0.5 feet per pixel. Using large images for object detection is impractical due to the high computational cost. To facilitate detection, the images were divided into tiles measuring 512 x 512 pixels or smaller, enabling the model to process each tile individually. The resulting detection labels, along with their corresponding coordinates, were subsequently transformed into shapefiles for visualization and advanced analysis within ArcGIS.

Figure 4.

Developed YOLOv5 bicycle feature model (a) confusion matrix, (b) training and validation loss curve - YOLO model (c) precision and recall graph, (d) F1 confidence graph, (e) precision and confidence graph, (f) training and validation loss graph - MTRE model, and (g) accuracy, IoU, and dice metrics graph – MTRE model.

Figure 4.

Developed YOLOv5 bicycle feature model (a) confusion matrix, (b) training and validation loss curve - YOLO model (c) precision and recall graph, (d) F1 confidence graph, (e) precision and confidence graph, (f) training and validation loss graph - MTRE model, and (g) accuracy, IoU, and dice metrics graph – MTRE model.

Since the detectors performed well on individual images, the detection and mapping process was scaled to the county level. For this process, each input image was processed iteratively through the detector. For the YOLO model, an output shapefile containing all detected features within a county was generated after processing all images, while the MTRE model produced a segmented raster of pedestrian lanes. The detection confidence scores were included in the output files, which were subsequently used to map bicycle and pedestrian lane features. The models were shown to effectively detect features from images with resolutions ranging from 1.5 feet down to 0.25 feet per pixel. However, they have not yet been tested on images with resolutions lower than those provided by the Florida APLUS system. Observations revealed occasional false detections by the models, which are addressed in the results discussion.

4.7. Post-processing

Following the application of the YOLO and MTRE models to the aerial imagery from Leon County, a total of 1,702 bicycle features and 1,391 pedestrian lane detections were identified. During post-processing, overlapping detections caused by the proximity of image tiles were eliminated. Features on state and local roadways were further classified into groups based on the specific analytical goals. Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) was employed to resolve duplicate detections, retaining only those with the highest confidence levels while removing any detections with over 10% overlap and lower confidence scores. To facilitate further analysis, the identified bicycle features were converted from polygon shapefiles to point shapefiles.

5. Results and discussions

The performance of the models was evaluated during training using precision, recall, IoU, and F1 scores. Subsequently, Leon County was selected as the case study area for collecting GT data and assessing the models’ performance in terms of completeness, correctness, quality, and F1 score. The GT dataset, comprising bicycle features and pedestrian lanes on Leon County roadways, served as a proof of concept. After detection, 1,702 bicycle features and 1,391 pedestrian lane features were observed. A visual inspection followed, during which 1,561 visible bicycle feature markings and 1,091 pedestrian lane polygons were identified in the GT dataset using masked images as the reference background. The evaluation involved direct comparisons of individual features detected in the aerial images.

Figure 6 illustrates the GT dataset alongside the detected pedestrian and bicycle lane markings in Leon County. For this case study, the YOLO model identified bicycle lane markers with a minimum confidence threshold of 10%. Bicycle lane markers (M) detected on local roads in Leon County were selected for analysis. A similar location-based methodology was applied to the GT dataset. The model’s performance was assessed by comparing detected points within the polygons and vice versa across confidence thresholds of 90%, 75%, 50%, 25%, and 10% (

Table 2). A confusion matrix provided a visual representation of the model’s accuracy compared to the GT dataset (

Figure 7).

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the proposed models’ predictions by comparing them against the GT dataset. Separate evaluations were conducted for bicycle and pedestrian detections, analyzing the models’ precision (correctness) and recall (completeness). The F1 score, calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, was used as the primary evaluation metric. This measure is particularly effective for imbalanced datasets, where the cost of missing actual objects is higher than misclassifying background regions as objects.

Finally, the YOLO model’s performance was assessed using completeness (recall), correctness (precision), quality (IoU), and F1 score. These evaluation metrics, originally applied in highway extraction studies (79, 80), are now standard for performance assessment in related object detection models (81, 82). Specific criteria were applied to calculate these metrics, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model's effectiveness:

- i.

GT: Number of bicycle feature polygons (Ground Truth),

- ii.

M: Number of Model detected bicycle feature points

- iii.

False Negative (FN): Number of GT bicycle feature polygons without M bicycle feature points,

- iv.

False Positive (FP): Number of M bicycle feature points not found within GT bicycle feature polygons,

- v.

-

True Positive (TP): Number of M bicycle feature points within GT bicycle feature polygons,

Performance evaluation metrics:

Completeness =, true detection rate among GT bicycle feature (recall)

Correctness =, true detection rate among M bicycle feature (precision)

Quality =, True detection among M bicycle feature plus the undetected GT bicycle feature (Intersection over Union: IoU).

The analysis revealed that the automated pedestrian lane detection and mapping model successfully identified and mapped 73% of pedestrian lanes with an average precision of 72% and an F1 score of 62%. Conversely, the bicycle feature detection model demonstrated a detection rate of 58% at a confidence level of 75%, achieving a precision of 99% and an F1 score of 74%. When the confidence threshold was lowered to 25%, the model detected approximately 82% of bicycle features, with a precision of 89% and an F1 score of 85%.

Improved accuracy at lower confidence thresholds is attributed to higher recall rates, which allow for increased detections. Observations indicated that features such as occluded bicycle markings—obstructed by vehicles, trees, or shadows—or those with faded markings typically had lower confidence scores. Lowering the confidence threshold incorporates these detections into the results, thereby increasing the total number of identified features. This process tends to introduce more true positives, while maintaining or reducing false positives and false negatives. Consequently, as the number of true positives rises with decreasing confidence, the model’s accuracy improves, since accuracy depends on the proportion of true positives relative to the total detections.

Bicycle feature detections were categorized by varying confidence levels, as detailed in

Table 2. The extracted roadway geometry data holds potential for integration with crash and traffic datasets, particularly at intersections, to inform policymakers and roadway users. This data can support a range of applications, such as identifying worn or invisible markings, comparing bicycle feature locations with other geometric elements like crosswalks and school zones, and analyzing crash patterns in these areas.

6. Conclusions and future work

This research investigates the use of computer vision techniques to extract roadway geometry, with a particular emphasis on bicycle and pedestrian lanes in Florida as a proof of concept. By harnessing the capabilities of computer vision, this method offers a modern alternative to traditional manual inventory processes, which are typically time-consuming and susceptible to human error. The developed system demonstrates the ability to automatically and accurately identify bicycle markings and pedestrian lanes from high-resolution imagery. By eliminating the need for manual inventory, the system not only improves the accuracy of roadway geometry data but also offers significant cost savings for stakeholders by reducing errors associated with manual data entry.

The implications of this approach extend beyond just cost and efficiency. For transportation agencies, the ability to extract and analyze roadway data from imagery offers numerous advantages. It can help identify outdated or obscured markings, which are critical for maintaining safety and regulatory compliance. Furthermore, the system allows for the comparison of geometric features, such as the alignment of turning lanes with crosswalks and school zones, providing agencies with insights into areas that may require redesign or safety improvements. The data can also be used in crash analysis, helping to identify patterns or hazards near these features, contributing to better-informed safety interventions.

The study highlights several limitations and provides suggestions for future research. One significant challenge is the difficulty in detecting feature markings on roadways obscured by tree canopies in aerial imagery. Moving forward, the proposed models could be incorporated into comprehensive roadway geometry inventory frameworks, including the Highway Safety Manual (HSM) and the Model Inventory of Roadway Elements (MIRE). By doing so, it could play a key role in ensuring that datasets are updated to reflect the current state of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. This would enable transportation agencies to more effectively manage roadway assets, enhance safety, and improve planning and operational decisions. Future research will aim to enhance the model's functionality by enabling the detection and extraction of additional continuous roadway features, such as guardrails, shoulders, and medians. Furthermore, efforts will be made to combine the identified bicycle and pedestrian lanes with crash statistics, traffic data, and demographic information to facilitate a more comprehensive analysis.

Author Contributions

The following authors confirm contribution to the paper with regards to Study conception and design: Richard Boadu Antwi, Prince Lartey Lawson, Kimollo Michael, Eren Erman Ozguven, Ren Moses, Maxim A. Dulebenets and Thobias Sando; Data collection: Richard Boadu Antwi, Prince Lartey Lawson, Eren Erman Ozguven, Kimollo Michael; Analysis and interpretation of results: Richard Boadu Antwi, Prince Lartey Lawson, Ren Moses, Thobias Sando; Manuscript preparation: Richard Boadu Antwi, Prince Lartey Lawson, Eren Erman Ozguven and Maxim A. Dulebenets. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Rural, Equitable and Accessible Transportation (REAT) Center, a Tier-1 University Transportation Center (UTC) funded by the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT), through the agreement number 69A3552348321. The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof.

References

- Dean, J. (2022). A Golden Decade of Deep Learning: Computing Systems & Applications. Daedalus, 151(2), 58–74. [CrossRef]

- Gui, S., Song, S., Qin, R., & Tang, Y. (2024). Remote Sensing Object Detection in the Deep Learning Era—A Review. Remote Sensing, 16(2), 327. [CrossRef]

- Antwi, R., Kimollo, M., Takyi, S. Y., Ozguven, E., Sando, T., Moses, R., & Dulebenets, M. (2024). Turning Features Detection from Aerial Images: Model Development and Application on Florida’s Public Roadways. Smart Cities, 7(3), 1414–1440. [CrossRef]

- Unlocking the Promise of AI in Transportation—ARTBA. (n.d.). Https://Www.Artba.Org/. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://www.artba.org/news/unlocking-the-promise-of-ai-in-transportation/.

- Laurel, C. T. U. 11301 S. R., & Md 20708 888.522.7486. (n.d.). Moving Towards a More Sustainable Future Using AI | Capitol Technology University. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://www.captechu.edu/blog/moving-towards-more-sustainable-future-using-ai.

- USDOT. (2015). Pedestrian and Bicyclist Road Safety Assessments—Summary Report. U.S. Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590.

- Why US Cities Are Investing in Safer, More-Connected Cycling Infrastructure | Urban Institute. (2022, February 2). https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/why-us-cities-are-investing-safer-more-connected-cycling-infrastructure.

- IPSOS. (2022). Global Advisor-Cycling Across the World-2022. IPSOS. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk.

- Bicycle Safety | NHTSA. (n.d.). [Text]. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://www.nhtsa.gov/book/countermeasures-that-work/bicycle-safety.

- Laird, J., Page, M., & Shen, S. (2013). The value of dedicated cyclist and pedestrian infrastructure on rural roads. Transport Policy, 29, 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh, E. C., Jarvandi, S., Franck, K. L., & Elizer, A. (2023). A Community Profile of Walking and Cycling for Exercise or Transportation in a Rural County in the Southeastern United States. Health Promotion Practice, 24(1_suppl), 46S-55S. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D. (2017, Autumn). Getting Around Town | FHWA. FHWA-HRT-18-001, 81(3). https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/autumn-2017/getting-around-town.

- Jalayer, M., Zhou, H., Gong, J., Hu, S., & Grinter, M. (2014). A comprehensive assessment of highway inventory data collection methods. In Journal of the Transportation Research Forum (Vol. 53, No. 1424-2016-117955, pp. 73-92). [CrossRef]

- Shamayleh, H., & Khattak, A. (2003). Utilization of LiDAR technology for highway inventory. In Proceedings of the 2003 Mid-Continent Transportation Research Symposium, Ames, Iowa.

- Alzraiee, H., Leal Ruiz, A., & Sprotte, R. (2021). Detecting of pavement marking defects using faster R-CNN. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 35(4), 04021035. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Zhou, H., Gordon, C., & Jalayer, M. (2012). Mobile terrestrial laser scanning for highway inventory data collection. In Computing in Civil Engineering (2012) (pp. 545-552). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Jalayer, M., Gong, J., Hu, S., & Grinter, M. (2013). Investigation of methods and approaches for collecting and recording highway inventory data. FHWA-ICT-13-022.

- Antwi, R. B., Takyi, S., Karaer, A., Ozguven, E. E., Moses, R., Dulebenets, M. A., & Sando, T. (2023). Detecting School Zones on Florida’s Public Roadways Using Aerial Images and Artificial Intelligence (AI2). Transportation Research Record, 03611981231185771. [CrossRef]

- Katsamenis, I., Bakalos, N., Protopapadakis, E., Karolou, E. E., Kopsiaftis, G., & Voulodimos, A. (2023). Real time road defect monitoring from UAV visual data sources. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, 603–609. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S. M., Bahmanyar, R., Henry, C., & Kurz, F. (2020). EAGLE: Large-scale Vehicle Detection Dataset in Real-World Scenarios using Aerial Imagery (arXiv:2007.06124). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.06124.

- Kraus, M., Azimi, S. M., Ercelik, E., Bahmanyar, R., Reinartz, P., & Knoll, A. (2021). AerialMPTNet: Multi-Pedestrian Tracking in Aerial Imagery Using Temporal and Graphical Features. 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2454–2461. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, P. J., Park, E. S., & Andersen, C. K. (2009). Benefits of pavement markings: A renewed perspective based on recent and ongoing research. Transportation research record, 2107(1), 59-68.

- Cho, Y., Kabassi, K., Pyeon, J. H., Choi, K., Wang, C., & Norton, T. (2013). Effectiveness study of methods for removing temporary pavement markings in roadway construction zones. Journal of construction engineering and management, 139(3), 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Young, T., Hazarika, D., Poria, S., & Cambria, E. (2018). Recent Trends in Deep Learning Based Natural Language Processing (arXiv:1708.02709). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.02709.

- Bousmina, A., Selmi, M., Ben Rhaiem, M. A., & Farah, I. R. (2023). A Hybrid Approach Based on GAN and CNN-LSTM for Aerial Activity Recognition. Remote Sensing, 15(14), 3626. [CrossRef]

- Antwi, R. B., Takyi, S., Karaer, A., Ozguven, E. E., Kimollo, M., Moses, R., ... & Sando, T. (2024). Automated GIS-Based Framework for Detecting Crosswalk Changes from Bi-Temporal High-Resolution Aerial Images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.09731.

- Antwi, R. B., Takyi, S., Kimollo, M., Karaer, A., Ozguven, E. E., Moses, R., Dulebenets, M. A., & Sando, T. (2024). Computer Vision-Based Model for Detecting Turning Lane Features on Florida’s Public Roadways from Aerial Images. Transportation Planning and Technology, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Luo, H., Yang, W., Yu, L., & Li, W. (2020). Structure-aware network for lane marker extraction with dynamic vision sensor. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.06204.

- Lee, S., Kim, J., Shin Yoon, J., Shin, S., Bailo, O., Kim, N., ... & So Kweon, I. (2017). Vpgnet: Vanishing point guided network for lane and road marking detection and recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (pp. 1947-1955). [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Mei, X., Prokhorov, D., & Tao, D. (2016). Deep neural network for structural prediction and lane detection in traffic scene. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 28(3), 690-703. [CrossRef]

- He, B., Ai, R., Yan, Y., & Lang, X. (2016). Accurate and robust lane detection based on dual-view convolutional neutral network. In 2016 IEEE intelligent vehicles symposium (IV) (pp. 1041-1046). IEEE.

- Huval, B., Wang, T., Tandon, S., Kiske, J., Song, W., Pazhayampallil, J., ... & Ng, A. Y. (2015). An empirical evaluation of deep learning on highway driving. arXiv preprint arXiv:1504.01716.

- Azimi, S. (2022). Infrastructure and Traffic Monitoring in Aerial Imagery Using Deep Learning Methods.

- Campbell, A., Both, A., & Sun, Q. C. (2019). Detecting and mapping traffic signs from Google Street View images using deep learning and GIS. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 77, 101350. [CrossRef]

- Machine learning: Everything you need to know. (n.d.). ISO. Retrieved July 3, 2024, from https://www.iso.org/artificial-intelligence/machine-learning.

- Tan, C. (2018, February 15). Human-centered Machine Learning: A Machine-in-the-loop Approach. Medium. https://medium.com/@ChenhaoTan/human-centered-machine-learning-a-machine-in-the-loop-approach-ed024db34fe7.

- Goldman, B. (2023, November 10). Can AI ever best human brain’s intellectual capability? Stanford Medicine Magazine. https://stanmed.stanford.edu/experts-weigh-ai-vs-human-brain/.

- What is Deep Learning? (n.d.). NVIDIA Data Science Glossary. Retrieved July 3, 2024, from https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/glossary/deep-learning/.

- What Is Deep Learning? | IBM. (2024, June 17). https://www.ibm.com/topics/deep-learning.

- Mahapatra, S. (2019, January 22). Why Deep Learning over Traditional Machine Learning? Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/why-deep-learning-is-needed-over-traditional-machine-learning-1b6a99177063.

- Cristina, S. (2021, August 13). The Chain Rule of Calculus for Univariate and Multivariate Functions. MachineLearningMastery.Com. https://machinelearningmastery.com/the-chain-rule-of-calculus-for-univariate-and-multivariate-functions/.

- Venugopal, P. (2023, October 15). The Chain Rule of Calculus: The Backbone of Deep Learning Backpropagation. Medium. https://medium.com/@ppuneeth73/the-chain-rule-of-calculus-the-backbone-of-deep-learning-backpropagation-9d35affc05e7.

-

AlexNet and ImageNet: The Birth of Deep Learning | Pinecone. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2024, from https://www.pinecone.io/learn/series/image-search/imagenet/.

- Shi, Z. (2021). Chapter 7—Learning. In Z. Shi (Ed.), Intelligence Science (pp. 267–330). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 25. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2012/hash/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Abstract.html.

- Wu, Y., & Li, J. (2023). YOLOv4 with Deformable-Embedding-Transformer Feature Extractor for Exact Object Detection in Aerial Imagery. Sensors, 23(5), 2522. [CrossRef]

- He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2018). Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2961–2969. http://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06870.

- Aghdam, H. H., Heravi, E. J., & Puig, D. (2016). A practical approach for detection and classification of traffic signs using convolutional neural networks. Robotics and autonomous systems, 84, 97-112. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. (2015). Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (pp. 1440-1448).

- Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R., & Sun, J. (2015). Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 28. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z., Gao, J., & Zhang, H. (2017). Recognition, location, measurement, and 3D reconstruction of concealed cracks using convolutional neural networks. Construction and Building Materials, 146, 775-787. [CrossRef]

- Panboonyuen, T., Jitkajornwanich, K., Lawawirojwong, S., Srestasathiern, P., & Vateekul, P. (2017). Road segmentation of remotely-sensed images using deep convolutional neural networks with landscape metrics and conditional random fields. Remote Sensing, 9(7), 680. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. J., Park, H. C., Ham, S. W., Kho, S. Y., & Kim, D. K. (2019). Extracting vehicle trajectories using unmanned aerial vehicles in congested traffic conditions. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2019 . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yuan, Y., & Wang, Q. (2018). ROI-wise Reverse Reweighting Network for Road Marking Detection. In BMVC (p. 219).

- Uçar, A., Demir, Y., & Güzeliş, C. (2017). Object recognition and detection with deep learning for autonomous driving applications. Simulation, 93(9), 759-769. [CrossRef]

- Perello, A. (2023, April 13). Uncovering The CompetitiveAdvantages of Aerial Surveying. GIM Magazine. https://www.gim-international.com/content/article/uncovering-the-competitive-advantages-of-aerial-surveying.

- Azimi, S. M., Henry, C., Sommer, L., Schumann, A., & Vig, E. (2019). SkyScapes Fine-Grained Semantic Understanding of Aerial Scenes. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 7392–7402. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S. M., Fischer, P., Körner, M., & Reinartz, P. (2018). Aerial LaneNet: Lane-marking semantic segmentation in aerial imagery using wavelet-enhanced cost-sensitive symmetric fully convolutional neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 57(5), 2920-2938. [CrossRef]

- Foucher, P., Sebsadji, Y., Tarel, J. P., Charbonnier, P., & Nicolle, P. (2011, October). Detection and recognition of urban road markings using images. In 2011 14th international IEEE conference on intelligent transportation systems (ITSC) (pp. 1747-1752). IEEE.

- Dadashova, B., Dobrovolny, C. S., & Tabesh, M. (2021). Detecting Pavement Distresses Using Crowdsourced Dashcam Camera Images (Final Report TTITTI-Student – 07). Safe-D National UTC.

- Ziulu, V. (2024). Leveraging Imagery Data in Evaluations Applications of Remote-Sensing and Streetscape Imagery Analysis. World Bank Publications.

- Wolf, P. R., Dewitt, B. A., & Wilkinson, B. E. (2014). Elementary Methods of Planimetric Mapping for GIS. In Elements of Photogrammetry with Applications in GIS (4th Edition). McGraw-Hill Education. https://www.accessengineeringlibrary.com/content/book/9780071761123/chapter/chapter9.

- Agrafiotis, P., & Georgopoulos, A. (2015). COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF VERY HIGH RESOLUTION SATELLITE AND AERIAL ORTHOIMAGERY. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XL-3/W2, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E. (2020, August 17). AERIAL VS. SATELLITE IMAGES: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE? JR Resolutions. https://jrresolutions.com/aerial-vs-satellite-images-whats-the-difference/.

- Gao, S., Chen, Y., Cui, N., & Qin, W. (2024). Enhancing object detection in low-resolution images via frequency domain learning. Array, 22, 100342. [CrossRef]

- Shermeyer, J., & Van Etten, A. (2019). The Effects of Super-Resolution on Object Detection Performance in Satellite Imagery. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 1432–1441. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Xu, X., Lin, H., Gui, R., Cao, M., & He, L. (2019). Automatic road-marking detection and measurement from laser-scanning 3D profile data. Automation in Construction, 108, 102957. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Wang, J., Wu, P., Shou, W., Wang, X., & Chen, M. (2021). Vision-based pavement marking detection and condition assessment—A case study. Applied Sciences, 11(7), 3152. [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau (US Census). (2020). Population Estimates. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/leoncountyflorida. Accessed June. 20, 2023.

- Redmon, J., & Farhadi, A. (2018). Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767.

- Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. (2016). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 779-788).

- Redmon, J., & Farhadi, A. (2017). YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 7263-7271).

- Bochkovskiy, A., Wang, C. Y., & Liao, H. Y. M. (2020). Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934.

- Jocher, G. (2020). YOLOv5 by ultralytics. Released date, 5-29. Https://Github. Com/Ultralytics/Yolov5. 2020.

- Wang, C. Y., Liao, H. Y. M., Wu, Y. H., Chen, P. Y., Hsieh, J. W., & Yeh, I. H. (2020). CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops (pp. 390-391).

- Liu, K., Tang, H., He, S., Yu, Q., Xiong, Y., & Wang, N. (2021, January). Performance validation of YOLO variants for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on bioinformatics and intelligent computing (pp. 239-243).

- Horvat, M., & Gledec, G. (2022, September). A comparative study of YOLOv5 models performance for image localization and classification. In 33rd Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems (CECIIS) (p. 349).

- Batra, A., Singh, S., Pang, G., Basu, S., Jawahar, C. V., & Paluri, M. (2019). Improved road connectivity by joint learning of orientation and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 10385-10393).

- Wiedemann, C., Heipke, C., Mayer, H., & Jamet, O. (1998). Empirical evaluation of automatically extracted road axes. Empirical evaluation techniques in computer vision, 12, 172-187.

- Wiedemann, C., & Ebner, H. (2000). Automatic completion and evaluation of road networks. International Archives of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 33(B3/2; PART 3), 979-986.

- Sun, K., Zhang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Roads and intersections extraction from high-resolution remote sensing imagery based on tensor voting under big data environment. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dai, J., Wang, Y., Li, W., & Zuo, Y. (2020). Automatic method for extraction of complex road intersection points from high-resolution remote sensing images based on fuzzy inference. IEEE Access, 8, 39212-39224. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).