1. Introduction

In the continually advancing field of computing, parallel and distributed systems have become critical for meeting the escalating demands for computational power, scalability, and efficient resource utilization. Rapid progress in interconnection networks, packaging technologies, system integration, and computational architectures has significantly enhanced the performance of these systems, enabling them to manage large-scale, complex workloads more effectively [

1]. By facilitating the concurrent execution of tasks across multiple processors and nodes, parallel and distributed computing plays a pivotal role in addressing contemporary computational challenges, including big data analytics, artificial intelligence, real-time simulations, and cloud-based services.

The significance of parallel and distributed systems lies in their ability to optimize computational performance and their potential to drive innovation across a wide spectrum of industries. These systems underpin advancements in high-performance computing (HPC), scientific research, and critical infrastructure, making them essential for modern technological progress. However, as the complexity of these systems grows, so do the challenges—including issues related to scalability, security, energy efficiency, fault tolerance, and the integration of diverse and heterogeneous resources. Managing these challenges is critical for the continued evolution and effectiveness of parallel and distributed computing.

Despite the numerous types of parallel and distributed systems proposed in recent decades, there is, to our knowledge, a lack of comprehensive reviews that systematically address their development or discuss future challenges and directions. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this gap by providing an overview of the evolution of parallel and distributed systems, emphasizing their relationships and differences. It further explores emerging trends in these systems, examines their key challenges, and outlines potential future research directions in this rapidly advancing field.

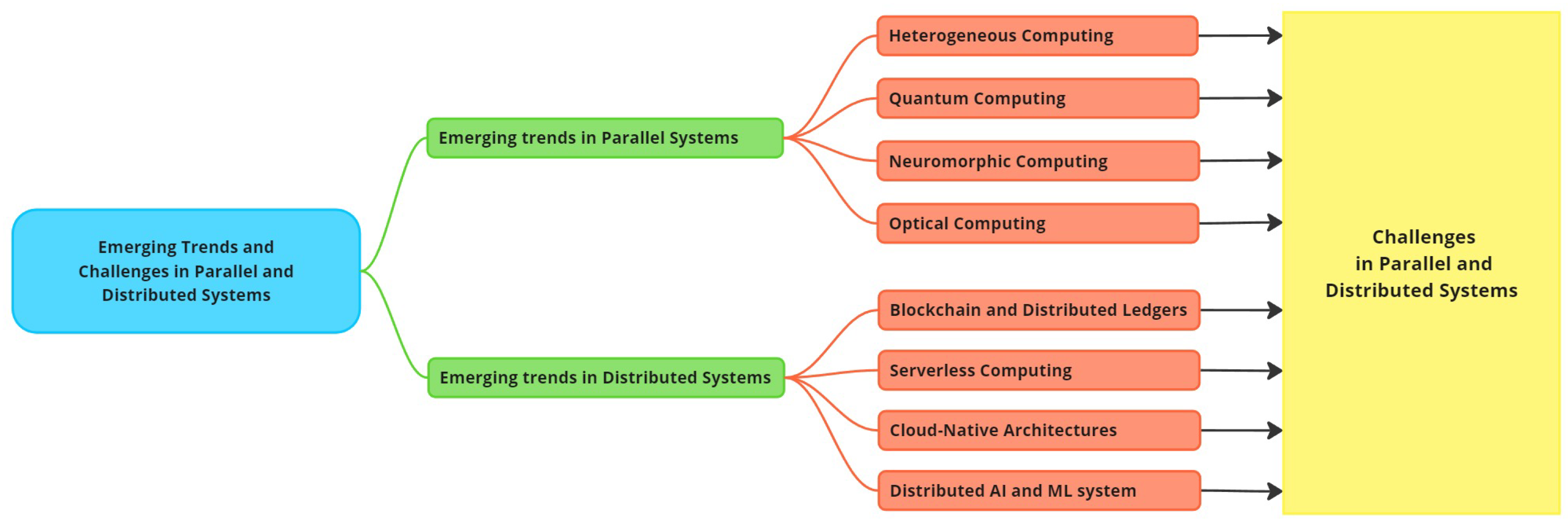

Figure 1 illustrates the organization of the paper and highlights the relationships among its sections. Specifically,

Section 2 provides an overview of parallel and distributed systems, including definitions, development, interrelationship, and key differences.

Section 3 delves into emerging trends in parallel systems, focusing on four key areas: heterogeneous computing, quantum computing, neuromorphic computing, and optical computing.

Section 4 explores the emerging trends in distributed systems, covering topics such as blockchain and distributed ledgers, serverless computing, cloud-native architectures, and distributed AI and machine learning systems.

Section 5 discusses key challenges facing parallel and distributed systems while

Section 6 outlines potential future research directions. Finally,

Section 7 concludes this paper.

2. Overview of Parallel and Distributed Systems

This section defines parallel and distributed systems, introduces various categories and common architectures, and explores their relationships and key differences. This foundational understanding sets the stage for a deeper examination of their historical context, key concepts, and terminologies.

2.1. Parallel Systems

Parallel systems are computational architectures designed to perform multiple operations simultaneously by dividing tasks into smaller sub-tasks, executed concurrently across multiple processors or cores within a single machine or a closely connected cluster [

2]. The primary goal of parallel systems is to reduce computation time and increase performance efficiency by leveraging the simultaneous processing capabilities of multiple processing units. These systems are commonly employed in applications requiring high computational power, such as scientific simulations, image processing, and large-scale data analysis [

3]. Key features of parallel systems include concurrency, coordination among processors, and efficient utilization of shared resources.

Traditional parallel systems can be categorized into three main types:

Shared Memory Systems, where multiple processors share a common memory space, allowing for direct communication through shared variables—examples include multi-core processors and symmetric multiprocessors (SMP);

Distributed Memory Systems, in which each processor has its own private memory and communicates with others by passing messages—examples include cluster computing and massively parallel processing (MPP) systems; and

Hybrid Systems, which combine shared and distributed memory approaches, often seen in modern supercomputers and high-performance computing clusters to leverage the advantages of both architectures. Common architectures include

Central Processing Units (CPUs), found in everyday devices like laptops and smartphones, enabling parallel task execution to improve performance and efficiency;

General-Purpose Graphics Processing Units (GPGPUs), used in gaming, scientific simulations, and AI applications to perform massive parallel computations;

Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs), custom-designed hardware optimized for specific applications such as cryptocurrency mining and specialized AI algorithms, providing high performance and energy efficiency; and

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), which are reconfigurable silicon devices that can be electrically programmed to implement various digital circuits or systems [

4], commonly used in scientific research, aerospace, and defense.

The origins of parallel computing can be traced back to the late 1950s with the advent of vector processors and early supercomputers like the IBM Stretch [

5] and the CDC 6600 [

6]. Significant advancements occurred in the 1980s with the introduction of massively parallel processing (MPP) systems [

7], including the Connection Machine [

8] and the Cray series [

9]. These systems utilized thousands of processors to perform simultaneous computations, paving the way for modern parallel architectures. In the 1990s and 2000s, the development of multi-core processors [

10] and general-purpose graphics processing units (GPGPUs) [

11] revolutionized parallel computing by making it more accessible and efficient. The rise of machine learning, big data, and deep learning advancements led to a surge in demand for high-performance parallel processing hardware. However, traditional parallel hardware began to show limitations in providing the necessary processing capacity for AI training. Challenges such as insufficient interconnection bandwidth between cores and processors, and the "memory wall" problem—where memory bandwidth cannot keep up with processing speed—became critical bottlenecks. To address these challenges, scientists and engineers have been developing innovative parallel computing systems tailored for AI and other demanding applications. In this paper, we focus on four emerging trends in parallel systems: heterogeneous computing, quantum computing, neuromorphic computing, and optical computing, which will be discussed in detail in

Section 3.

2.2. Distributed Systems

Distributed systems are computational architectures where multiple autonomous computing nodes, often geographically separated, collaborate to achieve a common objective [

12]. These nodes communicate and coordinate their actions by passing messages over a network [

13]. Distributed systems emphasize fault tolerance, scalability, and resource sharing, making them essential for various applications, including cloud computing, distributed databases, and blockchain networks. Key features of distributed systems include the ability to handle node failures gracefully, scale out by adding more nodes, and efficiently manage distributed resources.

Distributed systems can be categorized into several types: Client-Server Systems, where clients request services and resources from centralized servers—examples include web applications and enterprise software; Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Systems, in which nodes act as both clients and servers, sharing resources directly without centralized control—examples include file-sharing networks and blockchain platforms; Cloud Computing Systems, which provide scalable and flexible resources over the Internet—examples include Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Platform (GCP); and Edge Computing Systems, which process data near the source of generation to reduce latency and bandwidth usage—examples include Internet of Things (IoT) devices and real-time analytics systems. Common architectures in distributed systems include the Client-Server Model, used in web services where web browsers (clients) communicate with web servers to fetch and display content; Cloud Infrastructure, utilized for on-demand resource provisioning, hosting applications, and data storage, as seen in platforms like AWS and GCP; and IoT Networks, which connect various smart devices, enabling them to communicate and perform tasks collaboratively in real-time.

The concept of distributed systems emerged in the 1970s with the development of ARPANET, the precursor to the modern Internet [

14]. Early distributed systems focused on resource sharing and remote access to computational power. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the growth of distributed databases [

15] and the client-server model [

16], which became fundamental in enterprise computing. The 2000s marked the rise of cloud computing and big data, epitomizing the distributed system paradigm by providing scalable, on-demand computing resources over the Internet [

17]. Technologies like Hadoop and MapReduce [

18] enhanced the capability to process large datasets in a distributed manner. More recently, edge computing [

19] and the IoT [

20] have extended the reach of distributed systems to the periphery of networks, enabling real-time processing and decision-making at the edge. The development of digital cryptocurrencies and advancements in AI have further propelled the growth of distributed systems. In this paper, we focus on emerging trends such as blockchain and distributed ledgers, serverless computing, cloud-native architectures, and distributed AI and machine learning systems, which will be explored in

Section 4.

2.3. Relationship and Difference Between Parallel and Distributed Systems

Parallel and distributed systems are integral to modern computing, each contributing to efficiently executing large-scale and complex tasks. While they serve distinct purposes, their relationship is characterized by complementary roles and overlapping functionalities. Parallel systems are designed to maximize computational speed within a single machine or tightly coupled cluster [

21]. By dividing a large task into smaller sub-tasks and processing them simultaneously across multiple processors, parallel systems achieve significant reductions in computation time. This makes them ideal for high-performance computing applications like scientific simulations and real-time data processing. Distributed systems, on the other hand, are engineered to leverage multiple autonomous nodes that collaborate over a network to achieve a common goal. This architecture prioritizes scalability, fault tolerance, and resource sharing, making distributed systems suitable for applications that require robust, scalable, and reliable infrastructure, such as cloud computing and distributed databases.

In some scenarios, parallel and distributed systems can overlap, creating hybrid systems that combine the strengths of both architectures. For instance, a distributed system might employ parallel processing within individual nodes to further enhance performance. Conversely, a parallel system might distribute tasks across closely connected clusters, incorporating distributed computing elements. Both parallel and distributed systems aim to improve computational efficiency and handle large-scale problems, but they do so with different focuses and methods. The primary distinction between parallel and distributed systems lies in their architecture and operational focus:

Architecture: Parallel systems use multiple processors or cores within a single machine or a closely connected cluster to perform concurrent computations [

2]. Distributed systems, on the other hand, involve multiple independent machines that communicate over a network [

13].

Coordination and Communication: In parallel systems, communication between processors is typically fast and direct due to their close proximity. Distributed systems require communication over potentially large distances, often leading to higher latency and the need for sophisticated communication protocols.

Scalability and Fault Tolerance: Distributed systems are designed to scale out by adding more nodes and are built with fault tolerance in mind [

22], allowing them to continue functioning even if some nodes fail. Parallel systems focus on scaling up by adding more processors to a single machine [

23], with fault tolerance often a secondary consideration.

Resource Sharing: Distributed systems emphasize resource sharing and collaboration among independent nodes, each potentially equipped with its own local resources, such as distributed memory. Parallel systems concentrate resources within a single system, focusing on components like cache systems to enhance computational power.

Understanding the relationship and differences between parallel and distributed systems is crucial for engineers, researchers, and students as they explore the diverse applications and challenges within these fields. Both systems play vital roles in advancing computational capabilities and addressing the demands of modern technology.

3. Emerging Trends in Parallel Systems

The development of parallel systems has primarily followed two main directions: enhancing existing computing architectures and creating new parallel architectures to adapt to new applications, such as machine learning. Industry leaders like Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA exemplify this trend by producing new products based on advanced architectures annually, targeting general tasks, servers, AI training, etc. The rapid development of deep learning has spurred the proposal of many innovative architectures, such as near-memory computing architecture, heterogeneous computing architecture, quantum computing architecture, neuromorphic computing architecture, and optical computing architecture, aimed at overcoming the memory wall of traditional Von Neumann architecture [

24]. In response to the increasing volumes of processing data and advancements in artificial intelligence, we explore the emerging trends in parallel systems across four key areas: heterogeneous computing, quantum computing, neuromorphic computing, and optical computing.

3.1. Heterogeneous Computing

Heterogeneous computing integrates different types of processors and specialized computing units to work together, leveraging their unique strengths to enhance overall system performance and efficiency. As new architectures are proposed and technological advancements continue, heterogeneous computing continues to evolve. To explore the emerging trend of heterogeneous computing within parallel systems, we first examine the evolution of computing and then focus on advanced ultra-heterogeneous computing. Specifically, we discuss the software and hardware architectures that support ultra-heterogeneous computing and provide an outlook on its future developments.

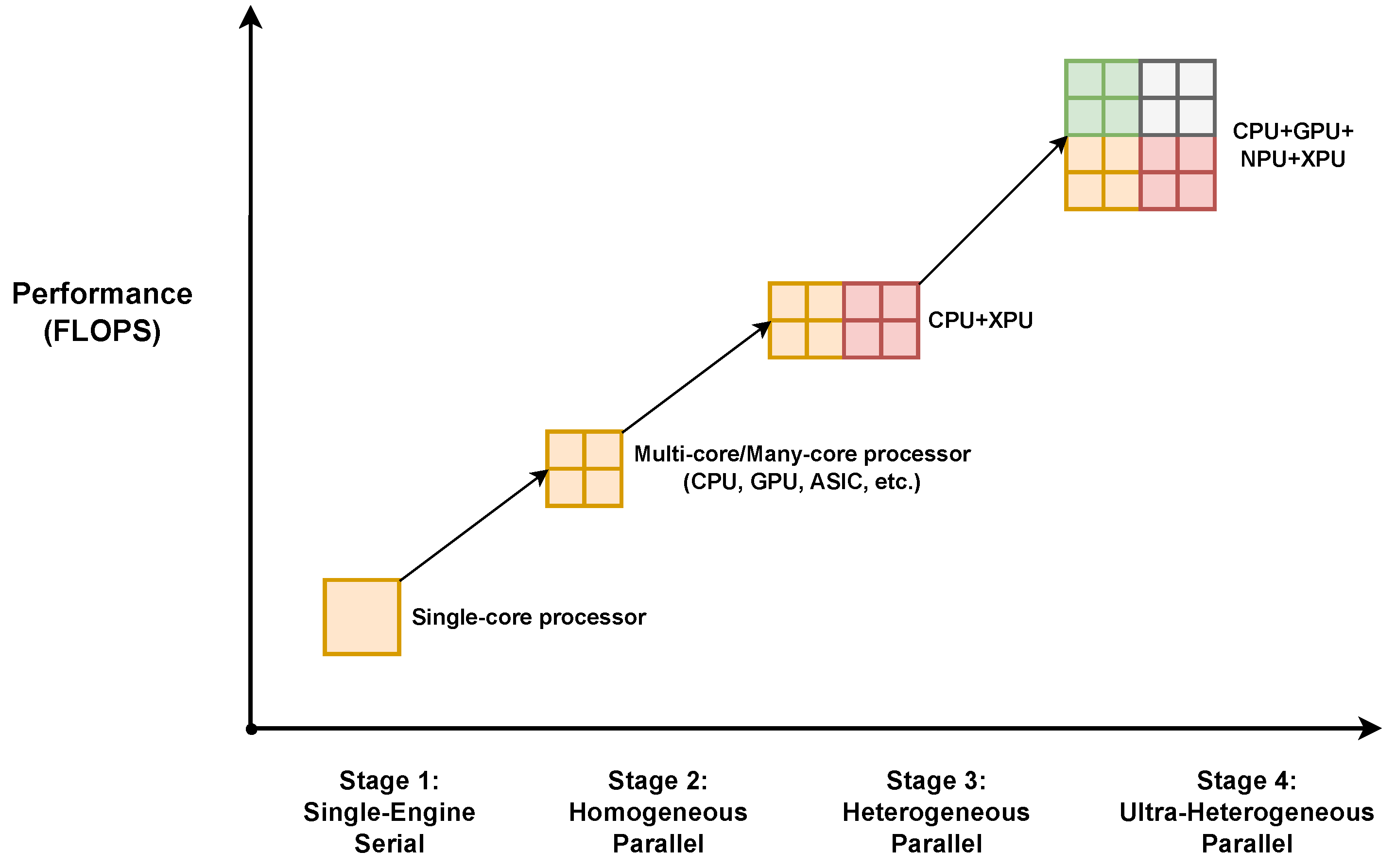

Figure 2 illustrates the various stages of computing eras, beginning with single-engine serial processing, followed by homogeneous computing, then heterogeneous computing, and finally ultra-heterogeneous computing. The evolution of heterogeneous computing can be described in four stages. In the first stage, a single processor handles all computational tasks sequentially, limiting performance to the capabilities of a single processing unit. As the demand for higher performance grew, this led to the second stage, which marked the introduction of homogeneous parallel processing. Here, multiple cores of the same type, such as multi-core CPUs or application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), work together to perform tasks in parallel. This approach improves performance by distributing workloads across several identical processors. However, the need to optimize different types of tasks more effectively pushed the transition to the third stage: heterogeneous computing. In this stage, two types of processors, such as CPUs and GPUs, are combined to handle various computational tasks more effectively, with each processor type optimized for specific operations, thereby enhancing overall efficiency. Finally, as applications became more complex and diverse, the necessity to maximize computational efficiency and performance led to the final stage: ultra-heterogeneous computing. This stage integrates more than three types of processing units, such as CPUs, GPUs, NPUs, and DPUs, leveraging the strengths of diverse processing architectures tailored to specific tasks.

With the development of technology, we are entering the early stages of ultra-heterogeneous computing, which promises higher performance than in previous eras. However, it relies on the support of both software and hardware.

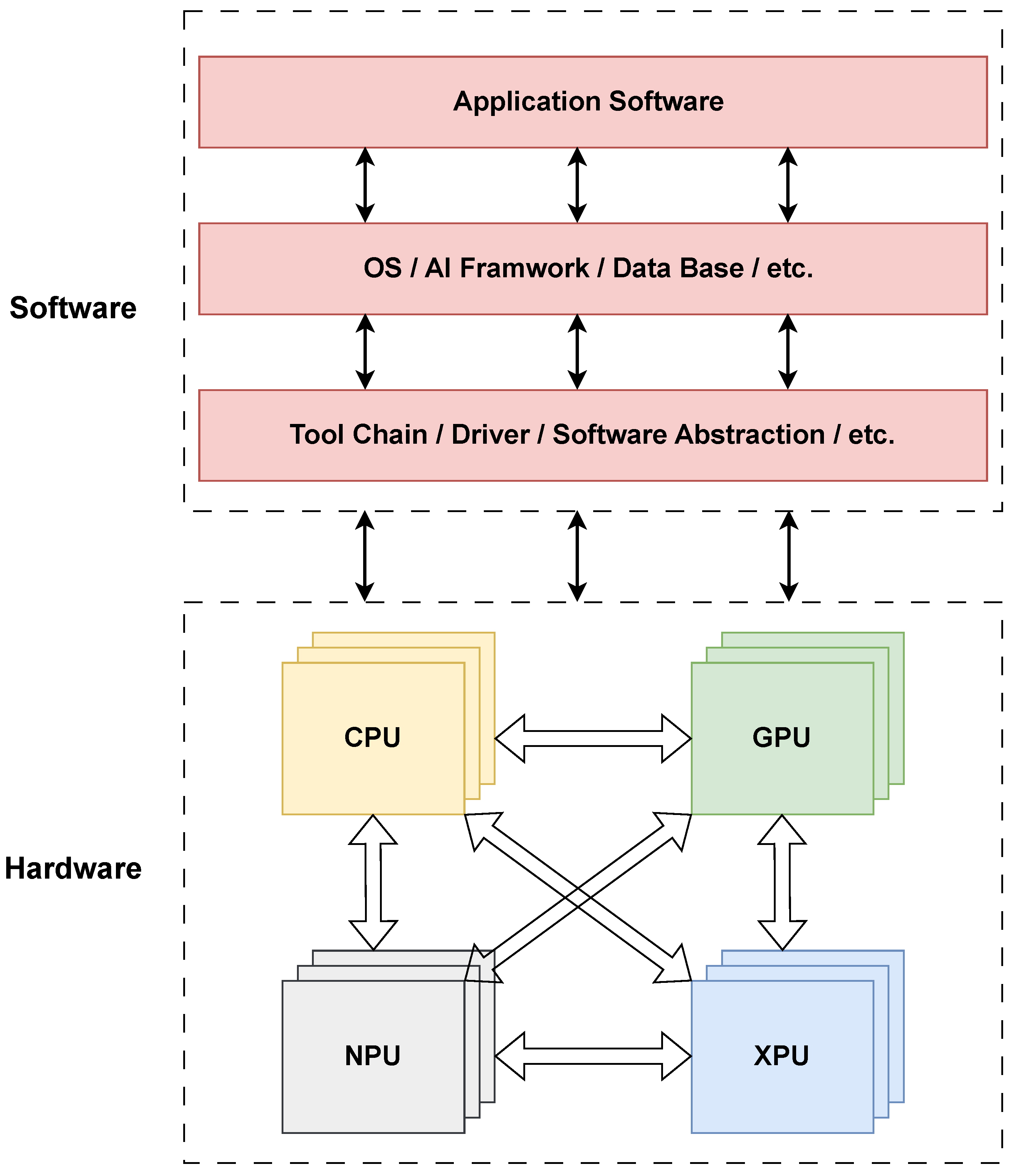

Figure 3 illustrates the software and hardware layers of ultra-heterogeneous computing. The software layer is responsible for effectively managing and optimizing diverse processing units. Software frameworks must support seamless communication and coordination between different types of processors, allowing tasks to be dynamically assigned to the most suitable processing unit. This involves developing sophisticated schedulers, resource managers, and communication protocols that can handle the complexities of ultra-heterogeneous environments. Additionally, programming models and languages (e.g., CUDA, OpenCL, OpenMP, MPI, etc.) must evolve to provide abstractions that simplify the development of applications for ultra-heterogeneous systems, enabling developers to leverage the full potential of diverse computing resources without needing to manage low-level hardware details.

The hardware architectures for ultra-heterogeneous computing integrate multiple processing units into a cohesive system. This involves designing interconnects that provide high-bandwidth, low-latency communication between CPUs, GPUs, NPUs, DPUs, and other specialized processors. Memory architectures must also evolve to support efficient data sharing and movement between different processing units, minimizing bottlenecks and maximizing throughput. Innovations in chip design, such as 3D stacking and advanced co-packaging technologies, play a crucial role in enabling ultra-heterogeneous systems by allowing different types of processors to be placed in close proximity, reducing communication delays and improving overall system performance.

The future of ultra-heterogeneous computing is promising, with potential applications spanning various fields, including artificial intelligence, scientific computing, and real-time data processing. As the demand for more powerful and efficient computing systems grows, ultra-heterogeneous architectures will likely become increasingly prevalent. Advances in software and hardware will drive this evolution, enabling the development of systems that can seamlessly integrate a wide range of processing units to deliver unparalleled performance and efficiency.

3.2. Quantum Computing

Quantum computing represents a significant departure from classical computing paradigms, utilizing the principles of quantum mechanics to perform computations. Quantum computing research began in the 1980s [

25]. Although its initial development was slow due to technological barriers, it has accelerated rapidly in recent decades with the scaling up of qubit numbers in superconducting systems [

26]. To explore the emerging trends in quantum computing, we start by discussing quantum computers and their applications, followed by an explanation of the different types of qubits and their development trends. Finally, we conclude with an overview of the current state and future prospects of quantum computing.

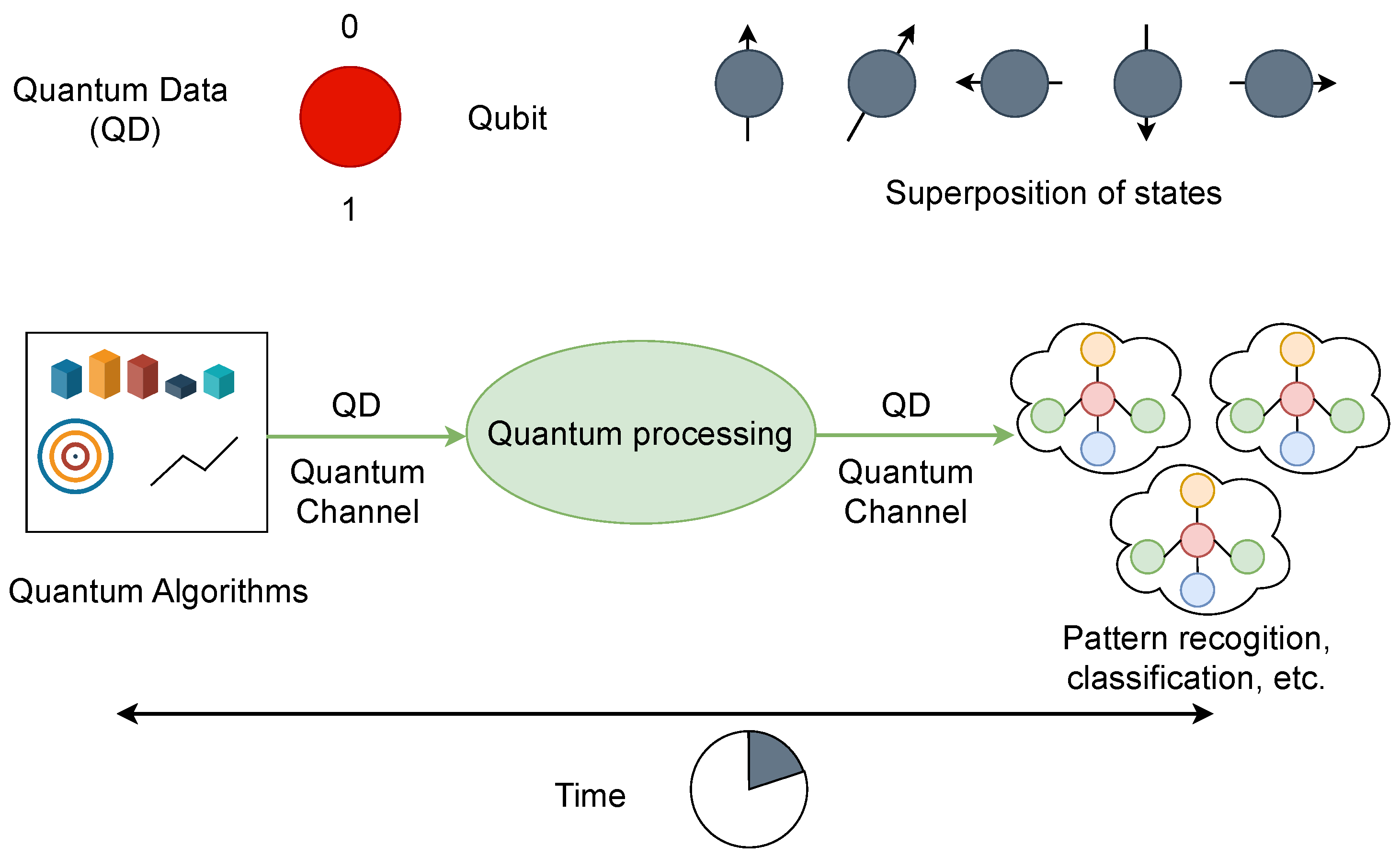

Quantum computers leverage qubits, which can exist in multiple states simultaneously (superposition) and be entangled with one another, allowing for potentially exponential increases in computational power for certain types of problems [

27]. Quantum gates are designed to manipulate the coefficients of basis states, enabling the performance of general functions akin to logic gates in traditional computing systems [

28]. Quantum algorithms are specifically designed to run on quantum computers, exploiting the principles of superposition, entanglement, and quantum interference to execute certain computations more efficiently than classical computers [

29]. Building on the unique properties of qubits, quantum computing holds promise for solving complex problems currently intractable for classical computers, such as large-scale optimization, cryptography, and the simulation of quantum physical systems [

30]. Major technology companies and research institutions invest heavily in quantum computing research, aiming to develop practical quantum computers and efficient quantum algorithms.

There are various physical systems to realize qubits, each offering distinct advantages and contributing to the overall progress in quantum computing. Superconducting qubits utilize superconducting circuits and are among the most mature technologies in this domain [

26]. Silicon qubits are based on semiconductor technology similar to classical computer chips [

31], offering compatibility with existing fabrication techniques. Trapped-ion qubits use ions trapped in electromagnetic fields and manipulated with lasers [

32], known for their high fidelity. Neutral atom qubits employ neutral atoms trapped in optical lattices [

33], facilitating scalable quantum computing. Diamond-based qubits utilize nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamonds [

34], which can be manipulated at room temperature, while photonic qubits use photons to encode quantum information [

35], providing advantages in communication due to their speed and low loss.

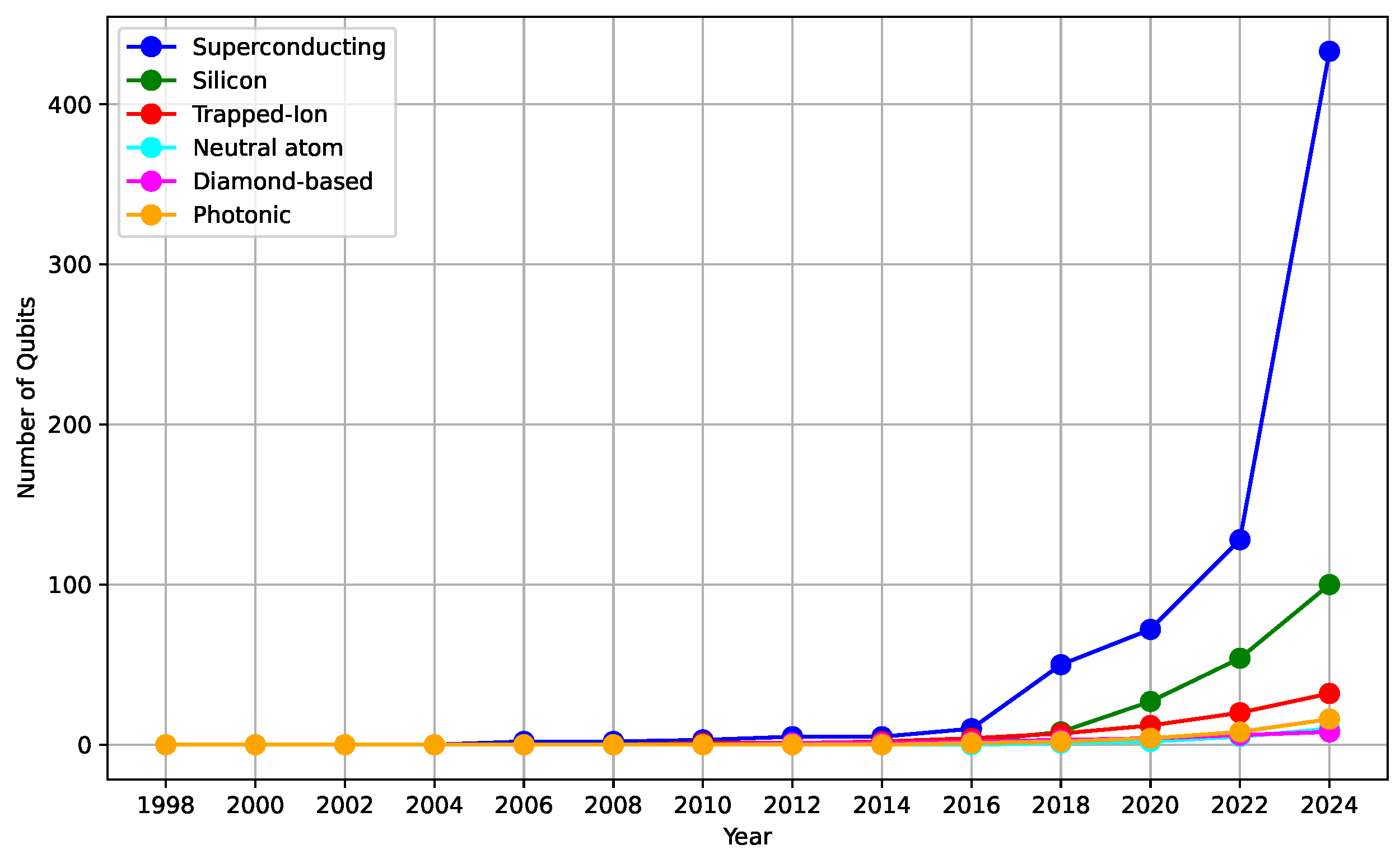

The current state of quantum computing demonstrates a promising trajectory, with continuous advancements in qubit technology and quantum algorithms. The number of qubits in quantum processors has been steadily increasing, as depicted in

Figure 4, highlighting the growth in qubit numbers over recent years across different technologies. IBM’s roadmap indicates plans to scale its Flamingo systems to 1000 qubits by 2027 and deliver quantum-centric supercomputers with 1000s logical qubits in 2030 and beyond [

36]. This trend underscores the potential of quantum computing to revolutionize various fields by providing computational power far beyond the reach of classical systems.

One promising field is quantum machine learning (QML), which combines quantum computing and machine learning. As research and development in this area progress, the practical applications of quantum computing are expected to expand, addressing the growing demand for more powerful and efficient computing solutions.

Figure 5 provides a clear view of quantum computing with machine learning for modern applications such as classification, pattern recognition, autonomous driving, etc. The figure illustrates the flow of quantum data through quantum processing and quantum algorithms, highlighting key components such as qubits and quantum channels and the application of quantum algorithms in tasks like pattern recognition and classification.

In conclusion, quantum computing represents one of the most transformative trends in the evolving landscape of parallel systems. By harnessing the unique properties of quantum mechanics, quantum computing stands poised to address some of the most challenging computational problems, complementing other emerging technologies in parallel systems.

3.3. Neuromorphic Computing

Neuromorphic computing is a class of brain-inspired computing architectures which, at a certain level of abstraction, simulate the biological computations of the brain. This approach enhances the efficiency of compatible computational tasks and achieves computational delays and energy consumption with biological computation. The term ’neuromorphic’ was introduced by Carver Mead in the late 1980s [

37,

38], referring to mixed analogue-digital implementations of brain-inspired computing. Over time, as technology evolved, it came to encompass a wider range of brain-inspired hardware implementations. Specifically, unlike the von Neumann architecture’s CPU-memory separation and synchronous clocking, neuromorphic computing utilizes neurons and synapses, the fundamental components, to integrate computation and memory. It employs an event-driven approach based on asynchronous event-based spikes, which is more efficient for the brain-like sparse and massive parallel computing, significantly reducing energy consumption. At the algorithmic level, the brain-inspired Spike Neural Network (SNN) serves as an essential algorithm deployed on neuromorphic hardware, efficiently completing machine learning tasks [

39,

40] and other operations [

41,

42]. Recent advancements in VLSI technology and artificial intelligence have propelled neuromorphic computing towards large-scale development [

43]. This section will introduce the developments in neuromorphic computing from both hardware and algorithmic perspectives and discuss future trends.

IBM TrueNorth is based on distributed digital neural models designed to address cognitive tasks in real time [

44]. Its chip contains 4096 neurosynaptic cores, each core featuring 256 neurons, with each neuron having 256 synaptic connections. On one hand, the intra-chip network integrates 1 million programmable neurons and 256 million trainable synapses; on the other hand, the inter-chip interface supports seamless multi-chip communication of arbitrary size, facilitating parallel computation. By using offline learning, various common algorithms such as convolutional networks, restricted Boltzmann machines, hidden Markov models, and multimodal classification have been mapped to TrueNorth, achieving good results in real-time multi-object detection and classification tasks with milliwatt-level energy consumption.

Neurogrid, a tree-structured neuromorphic computing architecture, fully considers neural features such as the axonal arbor, synapse, dendritic tree, and ion channels to maximize synaptic connections [

45]. Neurogrid uses analogue signals to save energy and a tree structure to maximize throughput, allowing it to simulate 1 million neurons and billions of synaptic connections with only 16 neurocores and a power consumption of only 3 watts. Neurogrid’s hardware is suitable for real-time simulation, while its software can be used for interactive visualization.

As one of the neuromorphic computing platforms contributing to the European Union Flagship Human Brain Project (HBP), SpiNNaker is a parallel computation architecture with a million cores [

46]. Each SpiNNaker node has 18 cores, connected by a system network-on-chip. Nodes select one neural core to act as the monitor processor, assigned an operating system support role, while the other 16 cores support application roles, with the 18th core reserved as a fault-tolerance spare. Nodes communicate through a router to complete parallel data exchange. SpiNNaker can be used as an interface with AER sensors and for integration with robotic platforms.

Intel’s Loihi is a neuromorphic research processor supporting multi-scale SNNs, achieving performance comparable to mainstream computing architectures [

47,

48]. Loihi features a maximum of 128,000 neurons per chip with 128 million synapses. Its uniqueness lies in its highly configurable synaptic memory with variable weight precision and support for a wide range of plasticity rules, and graded reward spikes that facilitate learning. Loihi has been evaluated in various applications, such as adaptive robot arm control, visual-tactile sensory perception, modelling diffusion processes for scientific computing applications, and solving hard optimization problems like railway scheduling. Loihi2 [

49], as a new generation of neuromorphic computing and an upgrade of Loihi, is equipped with generalized event-based messaging, greater neuron model programmability, enhanced learning capabilities, numerous capacity optimizations to improve resource density, and faster circuit speeds. Importantly, besides the features from Loihi1, Loihi2 has shared synapses for convolution, which is ideal for deep convolutional neural networks.

Spike Neural Networks (SNNs) are an essential algorithmic component of neuromorphic computing. To accomplish a task, we must consider how to define a tailored SNN and deploy it on hardware [

38]. From a training perspective, algorithms can be categorized into online learning and offline learning. The offline-learning approach first deploys the SNN on neuromorphic hardware and then uses the plasticity features to approximate backpropagation. This is a real-time method for optimizing hardware simulation of plasticity. Offline learning involves training an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) on a CPU or GPU based on specific tasks and data, then converting the ANN to an equivalent SNN and deploying it on neuromorphic hardware. As a key to training algorithms, various studies have analyzed backpropagation.

An Energy-Efficient Backpropagation approach successfully implemented backpropagation on TrueNorth hardware [

40]. Importantly, this method treats spikes and discrete synapses as continuous probabilities, allowing the trained network to map to neuromorphic hardware through probability sampling. This training method achieved 99.42% accuracy on the MNIST dataset with only 0.268 mJ per image. Furthermore, backpropagation through time (BPTT) has been implemented on neuromorphic datasets, providing a training method for recurrent structures on neuromorphic platforms [

50]. Benefiting from these training optimizations, SNNs in neuromorphic computing have been applied in various machine learning tasks such as Simultaneous Velocity and Texture Classification [

51], Real-time Facial Expression Recognition [

52], and EMG Gesture Classification [

53]. Similarly, they have been used in neuroscience research [

54,

55]. SNN-based neuromorphic computing is also utilized in non-machine learning tasks. Benefiting from the neuromorphic vertex-edge structure, graph theory problems can be mapped onto the hardware [

42,

56,

57]. Additionally, it has been applied to solving NP-complete problems [

58].

Despite the proven feasibility of neuromorphic computing in many tasks, it remains largely experimental. In today’s landscape of energy-consuming AI driven by GPU clusters, bringing neuromorphic computing out of the lab and achieving performance equal to or better than GPU-based AI with low energy consumption is a significant trend. Standardized hardware protocols and community-maintained software will be crucial. From a neuroscience research perspective, given that neuromorphic essentially simulates brain structures to various extents, simulating neural mechanisms based on this could provide new insights into brain function. Neuromorphic computing has a close-loop relationship with both AI and neuroscience, drawing inspiration from and serving both fields, tightly linking their development and advancing our understanding of intelligence.

3.4. Optical Computing

Optical computing leverages the properties of light to perform parallel computations, offering the potential to significantly surpass the speed and efficiency of electronic computing [

59]. Research in optical computing dates back to the early 1960s [

60]. Over the years, the primary focus of optical computing has been on integrating optical components for communication within computer systems or incorporating optical functions due to the rapid advancements in electronics [

60]. The optical computing elements are still developing and have not matured to date. Due to the boom of AI and the shortcomings of traditional electrical computer architecture, the adaptation and exploration of optical computing, especially in AI, have rapidly grown in recent years. To explore the emerging trends in optical computing, we first examine the different categories of optical computing systems and then discuss the potential and outlook of optical computing on artificial intelligence.

Optical computing systems can be categorized into analogue, digital, and hybrid optical computing systems (OCS). Analogue optical computing systems (AOCS) utilize the continuous nature of light to perform computations, leveraging properties such as intensity, phase, and wavelength to represent and process data. This enables high precision and real-time processing capabilities, making AOCS suitable for signal processing and image recognition applications. On the other hand, digital optical computing systems (DOCS) operate on binary principles similar to traditional electronic computers, where light is used to represent binary data (0s and 1s) and perform logical operations through optical gates. DOCS can achieve exceptionally high-speed processing and parallelism, ideal for tasks requiring rapid data computation. Hybrid optical computing systems (HOCS) combine the strengths of both analogue and digital approaches, integrating continuous and discrete data representations to optimize performance across a broader range of applications. By leveraging the unique advantages of light, such as its speed and bandwidth, these hybrid systems can enhance computational efficiency and open new frontiers in fields such as telecommunications, artificial intelligence, and scientific simulations. The feature comparison of these three systems is summarized in

Table 1.

Optical computing leverages optical components such as microring resonators (MRRs) and Mach–Zehnder interferometers (MZIs) to design essential elements in optical computing systems like logic gates, switches, storage devices, routers, and photonic integrated circuits. The development of these components has been pivotal in advancing the field, allowing for the creation of more sophisticated and efficient optical computing systems. Initially, research focused on the fundamental properties of light and how it could be manipulated for computation. Over time, advancements in materials science and nanofabrication have enabled the miniaturization and integration of optical components, leading to the development of compact and powerful photonic circuits.

Current applications of optical computing span various domains, including telecommunications, where optical components enhance data transmission speeds and capacity. In artificial intelligence, optical neural networks are being explored for their potential to perform complex computations at speeds unattainable by traditional electronic systems. Researchers are also investigating optical computing in scientific simulations, where the high-speed processing capabilities can significantly accelerate the analysis of large datasets. As this paper focuses on the emerging trends in optical computing, we recommend readers to read the review paper [

60] for the current status of optical computing, the review paper [

61] for Analog Optical Computing for AI, the review paper for neural network accelerator with optical computing and communication [

62], and the book [

63] for fundamentals of optical computing.

In summary, the evolution of optical computing systems has been marked by significant advancements in optical component technology and a growing interest in their applications across various fields. As research progresses, the potential of optical computing to transform industries and drive innovation remains immense.

4. Emerging Trends in Distributed Systems

In the rapidly evolving landscape of computing, distributed systems have become integral to handling the scale, complexity, and diversity of modern applications. By leveraging multiple interconnected computing resources, distributed systems provide scalable, resilient, and efficient solutions that traditional centralized systems cannot offer. As data volumes grow exponentially and applications demand real-time processing and decision-making, innovative approaches in distributed computing are essential. This section explores the emerging trends in distributed systems, focusing on four key areas: blockchain and distributed ledgers, serverless computing, cloud-native architectures, and distributed artificial intelligence and machine learning systems. These advancements are redefining how data is managed, processed, and secured across various industries, enabling new possibilities while addressing critical scalability, efficiency, security, and privacy challenges.

4.1. Blockchain and Distributed Ledgers

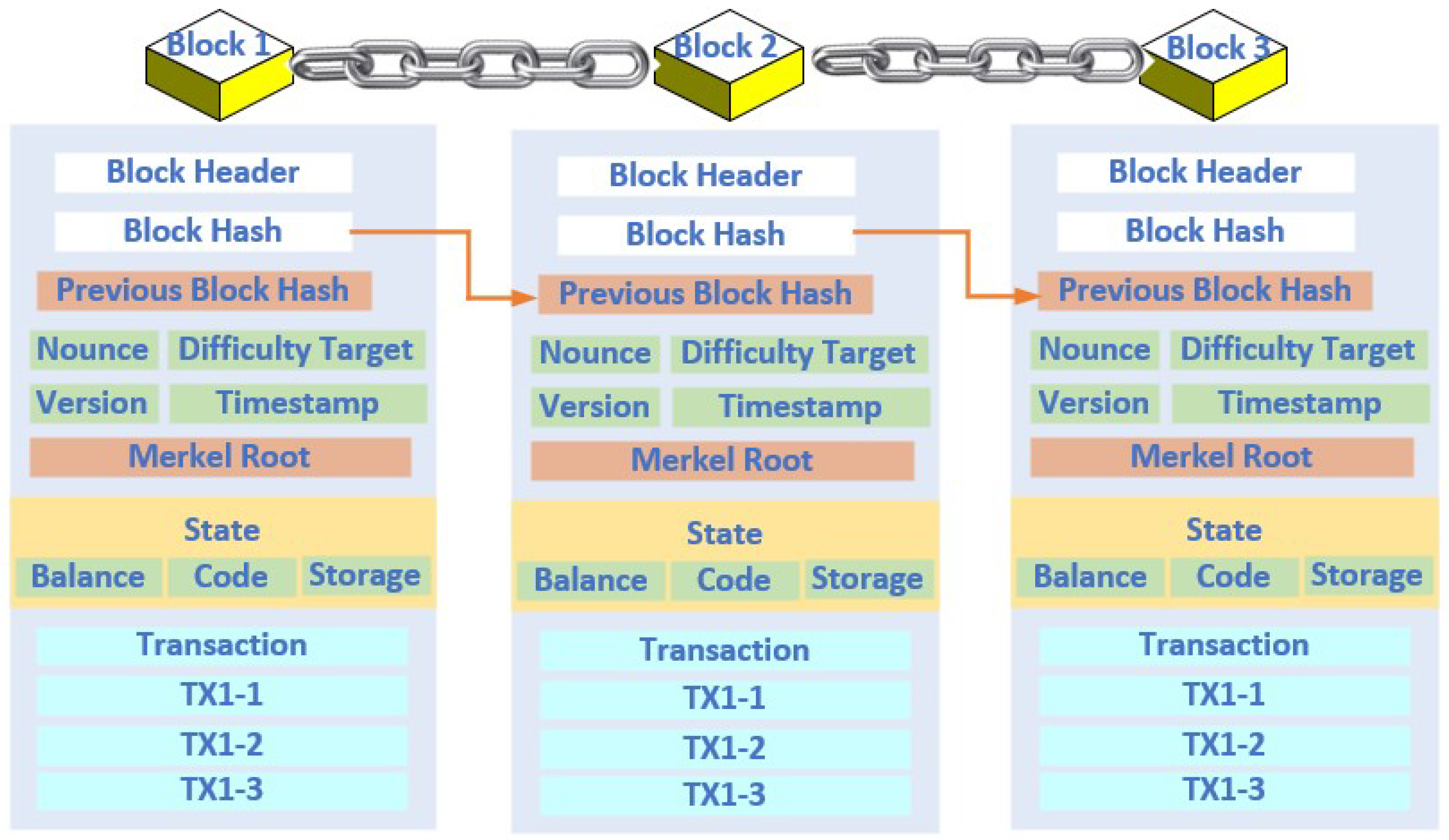

The concept of the blockchain was first coined by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 after the failure of the global financial system in 2007 [

64]. Though he didn’t formally define the blockchain, he demonstrated the blockchain concept for electronic cash (called Bitcoin) transfers where no central authority is needed to prevent double-spending. The successful transaction of Bitcoin took place in 2009 by transferring 10 BTC (BitCoin) to his friend Hal Finney. Satoshi uses a peer-to-peer network to timestamp transactions through a hash-based proof-of-work chain, which acts as an unchangeable record unless the proof-of-work is redone. However, the concept of Blockchain is fundamentally based on three elements: i) blind signature, a cryptographic concept proposed by David Chaum in 1989 for automation of payment [

65]; ii) timestamped documents which secure digital documents by stamping the documents with the date [

66]; and iii) a reusable proof-of-work (RPoW) [

67]. Therefore, researchers formally defined the blockchain as a meta-technology which combines several computing techniques [

68]. However, the most widely adopted definition of blockchain is a distributed digital ledger technology with a ledger of transactions, or blocks, that form a systematic, linear chain of all transactions ever made. Blockchain presents time-stamped and immutable blocks of highly encrypted and anonymised data not owned or mediated by any specific person or groups [

69,

70]. A block in a blockchain is primarily identified by its block header hash or block hash, a cryptographic hash made by hashing the block header twice through the SHA256 algorithm. In addition, a block can also be identified by the block height, which is its position in the blockchain or the number of blocks preceding it in the blockchain. The Merkle tree offers a secure and efficient way to create a digital fingerprint for the complete set of transactions. A blockchain structure is shown in

Figure 6, where blocks are connected through their respective hash code.

Distributed ledger technology (DLT) is the underlying generalised concept that makes the blockchain work in a distributed platform. The concept of DLT evolved from “The Byzantine General Problems” described by Lamport et al. in [

71] to evaluate the strategy on how computer systems must handle conflicting information in an adversarial environment. Consensus protocols, like Proof of Work and Proof of Stake, allow participants to achieve a shared view of the ledger without intermediaries. Additionally, cryptographic techniques, such as the Schnorr Signature Scheme and Merkle Tree, enhance data integrity and trust within blockchain frameworks, reinforcing secure data verification processes. A distributed ledger is a digital record maintained across a network of machines, known as nodes, with any updates being reflected simultaneously for all participants and authenticated through cryptographic signature [

72,

73]. Beyond cryptocurrencies, blockchain’s applications span sectors from supply chain management and healthcare to smart cities. For example, in smart cities, storing critical data—such as video footage from vehicle-mounted cameras—on immutable ledgers enhances traceability and authenticity. Such applications underscore blockchain’s ability to provide secure, tamper-resistant solutions in areas where reducing reliance on intermediaries and ensuring data privacy is essential. These examples highlight blockchain’s versatility in addressing complex data integrity and transparency requirements across industries [

74]. This system provides a transparent and verifiable record of transactions. These features make it applicable across different industries, including eHealth [

75,

76], the intellectual property [

77,

78], education, digital identity, finance [

79,

80,

81], supply chain [

82,

83,

84], IoT [

85,

86,

87], etc.

Modern healthcare, alternatively healthcare 5.0, is fundamentally based on interoperability to provide patient-centred care by incorporating smart and predictive systems. In this regard, blockchain’s anonymity and Immutability features make it unparalleled when considering secure information sharing among different healthcare providers. Numerous frameworks such as MeDShare [

88], Medblock [

89], HealthBlock [

90], BLOSOM [

91] have been studied in recent days to secure the patient’s healthcare record. In [

75] proposes an interoperable blockchain-based framework, BCIF-EHR, for better cooperation among different blockchain-based healthcare entities, allowing the sharing and integration of EHRs smoothly while maintaining the privacy and security of patients’ data. However, a decentralised authentication and access control mechanism should be developed for BCIF-EHR so that only an authorised person or organisation can access shared data. To address this issue, TrustHealth proposed in [

76] leverages blockchain and a trusted execution environment and designs a secure database that ensures the confidentiality and integrity of electronic health records. It further incorporates a secure session key generation protocol to establish secure communication channels between healthcare providers and the trusted executed environment.

4.2. Serverless Computing

Serverless computing evolves from cloud computing in that the developer does not have to manage infrastructure because the server is abstracted, and a developer-only deals with application functionality. In this model, code is deployed in discrete bits called functions by the developers, invoked on specific events that reduce the cost and complexity of managing full-time servers drastically [

92,

93]. Resources such as AWS Lambda [

94], cloud providers provide dynamic allocation of resources only when the code is executed. This attains scalability with efficiency and engenders a pricing model based on "pay-as-you-go" logic-one is charged only for the resources actually used [

95].

Scalability with serverless computing is optimised in that applications scale up and down with workloads automatically; it is almost completely automated, relieving users from the need to configure or look after servers. Key benefits of this architecture include cost reduction and fast deployment; hence it suits web applications [

96], IoT [

97]. or any kind of data processing [

98]. While serverless makes it a lot easier to develop, it then opens up new challenges with latency and state management. The strategies that aimed at improving the performance of the functions themselves, and how they communicate to each other, therefore, played an important role in ensuring smooth operation at scale [

99].

However, as serverless computing keeps maturing, it has fostered a host of new state-of-the-art frameworks that allow significant enhancement of flexibility and compatibility in serverless environments across data centres, quite evident in state-of-the-art frameworks like ServerlessOS [

100]. As a result, all in all, serverless computing holds immense promises for scalable and cost-effective solutions and hence is a tool worth considering in businesses that strive for cloud operation optimisation [

101] and by developers who want to concentrate on the application logic rather than its infrastructure management [

102].

Serverless computing introduces the Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) model, freeing developers from server management and leaving cloud providers responsible for resource allocation, scaling, and maintenance. This paradigm allows applications to scale dynamically to meet fluctuating demand. As [

103] explains, FaaS is ideal for unpredictable workloads, charging only for the compute resources used per function invocation. This model shifts developers’ approach to design, favouring simplicity and scalability over complexity. The serverless model brings significant benefits, including reduced operational costs, automatic scaling, and faster time-to-market [

104]. However, limitations like cold start latency, vendor lock-in, and restrictions on long-running processes can affect its suitability for certain use cases, particularly those requiring continuous high performance [

105]. Careful consideration of these factors is essential when evaluating FaaS to ensure performance needs align with serverless capabilities.

Serverless computing, while beneficial in many respects, comes with its own set of drawbacks. A prominent issue is the latency associated with initialising functions, often called "cold starts," which can hinder performance in latency-sensitive applications. Strategies to mitigate this latency typically involve adjusting container sizes and function granularity to achieve an optimal balance [

106]. Additionally, serverless platforms work effectively for stateless, event-driven tasks, but they struggle with complex, state-dependent workloads that require significant code restructuring, potentially leading to increased operational expenses [

107]. Moreover, although serverless architectures are capable of scaling elastically, their resource management capabilities remain limited, making them less suitable for high-throughput, sustained workload scenarios [

108].

Another concern is that serverless frameworks are not ideally suited for edge computing or IoT environments, where low-latency processing is crucial. The traditional cloud-based serverless model does not easily integrate with resource-limited edge devices, reducing deployment versatility in these contexts [

109]. Financially, serverless pricing models can also become unexpectedly costly for high-frequency applications, often making them less economical compared to traditional cloud setups with dedicated resources [

110]. Finally, issues related to security and the isolation of functions pose challenges when handling sensitive data or complex workflows within serverless environments [

111].

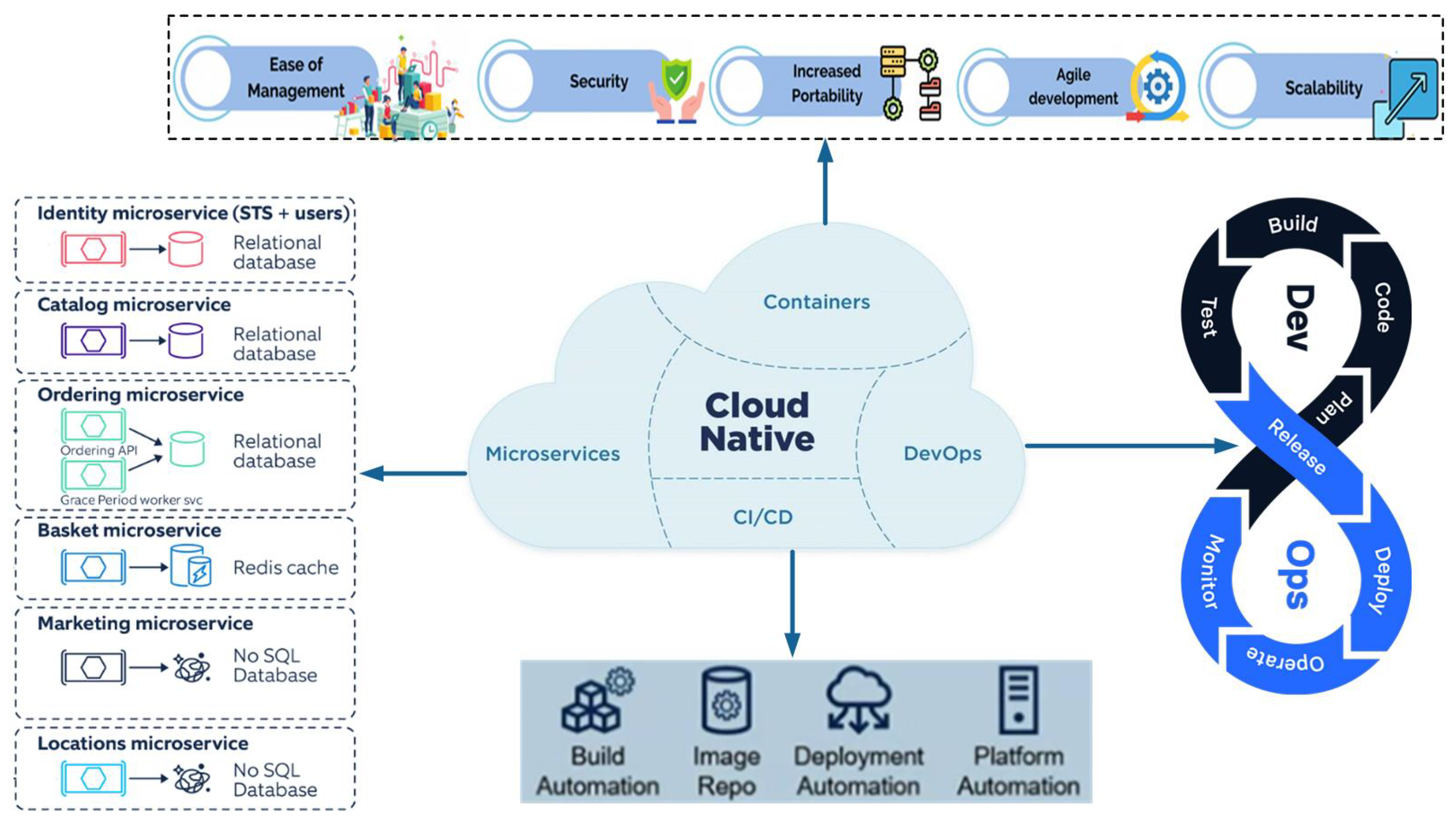

4.3. Cloud-Native Architectures

Cloud-native architecture is an advanced cloud computing approach designed to optimise cloud application performance by utilising microservices, containerisation, and continuous integration/continuous delivery (as shown in

Figure 7) [

112,

113]. Containers, which provide lightweight, isolated environments for microservices, enable consistency across development, testing, and production environments. Widely used tools like Docker and Kubernetes have become standards in container orchestration, easing the management and scaling of microservices in a distributed cloud environment and streamlining development pipelines for faster, more flexible deployments [

114]. Cloud-native applications are modular, unlike traditional monolithic structures where each component is to be managed, scaled, and updated independently. Moreover, it is effective in highly dynamic environments where rapid iteration and resilient deployment are essential for applications needing continuous scalability [

115,

116,

117]. Cloud-native architecture is core to Industry 4.0, where real-time data processing across IoT and edge devices matters most. These architectures realise smooth integration in distributed systems, hence managing large-scale, latency-sensitive data efficiently [

118]. One of the prominent design elements of cloud-native designs is the multi-cloud and distributed cloud models that, for instance, enable the deployment of applications across multiple cloud providers [

119]. This will increase availability and avoid vendor lock-in, giving flexibility and resilience to the enterprises by utilising unique services across cloud platforms [

120].

Moreover, cloud-native architectures increasingly leverage Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) environments, simplifying infrastructure management and providing essential scaling services [

121]. This is in line with cloud federation strategies that are going to improve the interoperability between providers, enabling smooth migration and management of services between heterogeneous cloud systems [

122]. Finally, a streamlined architecture is guaranteed via Infrastructure as Code solutions since it automates cloud resource provision, allowing cloud-native applications to be deployed and scaled efficiently and securely [

123]. These architectures improve scalability and resilience since microservices can be individually scaled based on workload needs, enhancing fault tolerance and resource utilisation [

124]. Orchestration tools, like Kubernetes, allow cloud-native applications to handle increasing user demand with minimal downtime through sophisticated scaling and load balancing. However, monitoring, inter-service communication, and security concerns remain, which require robust management frameworks and security protocols to maintain system stability [

125].

4.4. Distributed AI and Machine Learning System

Distributed AI and machine learning systems are the backbone for scalable training and deployment of complex models across decentralised networks [

126]. Unlike the centralised approach, this architecture allows the computation to be distributed among different nodes, reducing the latency in training and efficiently processing large datasets [

127]. This ML approach can optimise the learning and AI inference, particularly for resource-constrained devices such as IoT or edge computing devices used in real-time applications [

128]. It aligns with the principles of federated learning, which allow for collaborative model training without the need to share raw data, thus preserving data privacy and reducing bandwidth demands [

129]. By leveraging intelligent agents in a distributed environment, these systems can significantly reduce model training time while maintaining robust fault tolerance [

130]. Moreover, distributed learning algorithms applied in different application areas such as 6G [

131], smart grid systems [

132] illustrate how these methods can optimise resource usage and enable real-time decision-making with minimal latency. The advanced variants, like AutoDAL, provide automatic tuning of hyperparameters, extending back to a distributed learning framework. It solves the scalability and efficiency problems related to large-scale data analyses, as noted by [

133].

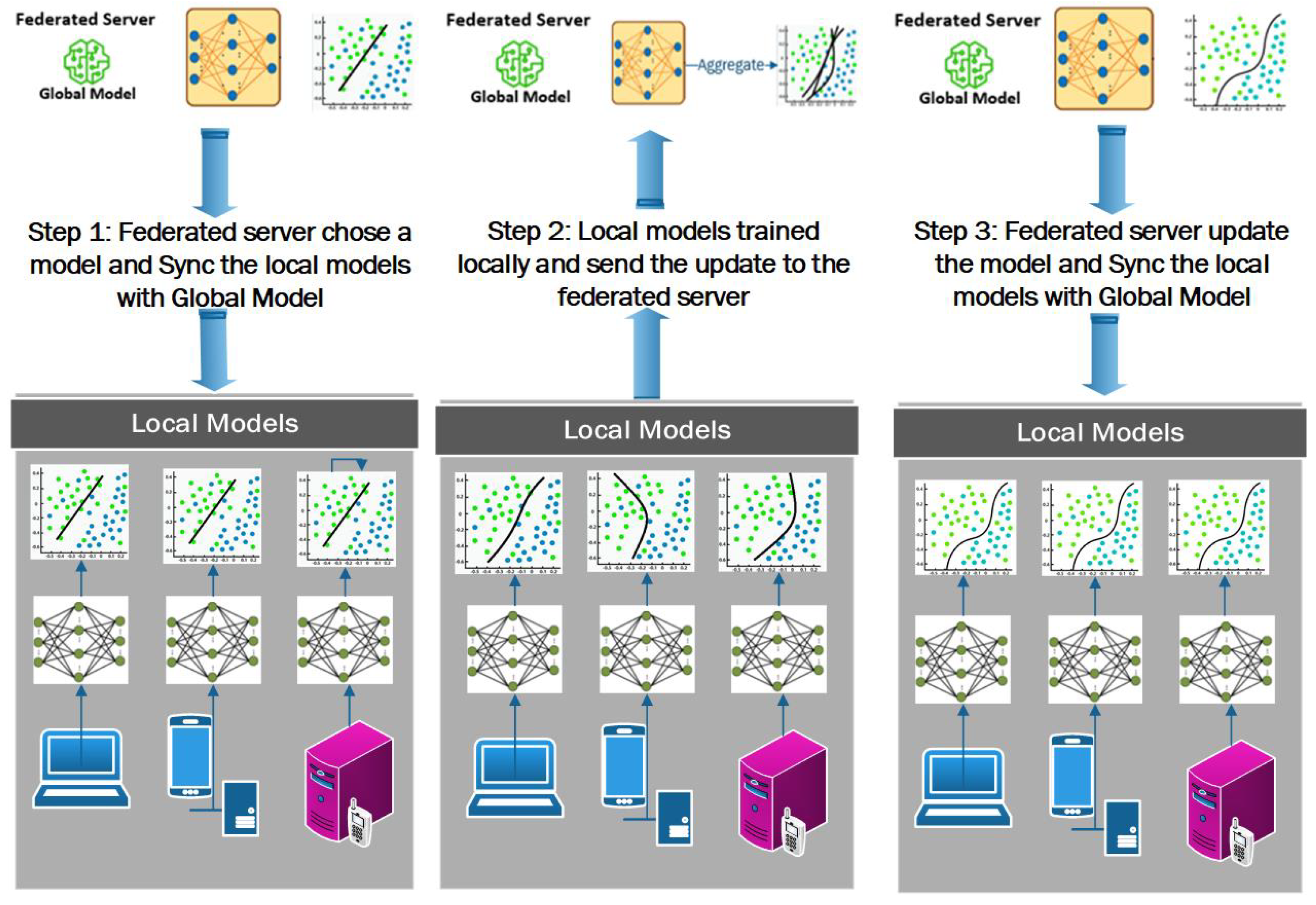

Federated learning is an emerging area in distributed AI, allowing model training across decentralised devices or servers without centralising raw data. This approach improves privacy and reduces data transfer costs, with models trained locally on edge devices and only shared parameters sent back to central servers, as shown in

Figure 8 [

134]. Federated learning is especially valuable in applications with strict privacy requirements, such as healthcare and finance, where regulatory constraints limit centralised data storage [

135]. This trend underscores the need to balance privacy with machine learning accuracy in sensitive domains.

Distributed training systems enable simultaneous model training across multiple nodes, speeding up the development of complex AI models. Techniques like data parallelism and model parallelism optimise resource usage, which is crucial for large-scale training in fields like natural language processing and computer vision with high computational needs [

136]. This decentralised approach makes scalable, efficient machine learning more attainable, reducing dependence on vast, centralised infrastructures and enabling more adaptable, resource-efficient training configurations [

137].

Distributed training algorithms offer powerful methods for processing large datasets and handling extensive computational workloads, yet they come with considerable challenges. A primary hurdle is a substantial communication overhead [

138] that arises when coordinating model updates across multiple nodes, which can hamper training efficiency. Bandwidth constraints and network latency [

139] further complicate synchronisation efforts, especially within decentralised systems where nodes vary in computational capacity and network reliability. Thus, there is a critical need for adaptive algorithms in distributed training frameworks that can maximise the efficiency of computational resources in these distributed environments [

140]. Advanced strategies such as Asynchronous Stochastic Gradient Descent (ASGD) [

141,

142] and adaptive update algorithms have been proposed to address these challenges. While these approaches reduce network congestion by allowing nodes to operate independently and asynchronously, they still struggle to maintain model accuracy due to inconsistent parameter updates across nodes [

143]. In decentralised training scenarios with limited bandwidth, such adaptive algorithms can be especially valuable by reducing synchronisation delays. Another key issue in distributed training involves managing data heterogeneity and maintaining data privacy. In many real-world settings, data across nodes is often non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed). This leads to skewed model updates that can affect training effectiveness, as seen in applications like edge devices and IoT networks [

144]. Techniques such as adaptive loss functions and dynamic weighting of local models have been introduced to support model convergence despite data imbalances, mitigating the impact of non-uniform data on overall performance [

145]. Additionally, adaptive resource allocation frameworks that adjust computation and communication parameters based on workload and node capabilities are essential in industrial applications where real-time responses are required [

146].

In summary, distributed systems aim to improve scalability, efficiency, and security, focusing on blockchain, serverless computing, cloud-native architectures, and distributed AI. These advancements enhance data privacy and resource efficiency, which are crucial for sectors like healthcare and finance. Collectively, these trends signify a shift in distributed system design to meet the complex demands of modern industries.

5. Challenges in Parallel and Distributed Systems

Parallel and distributed systems have revolutionized the way computational tasks are performed, enabling the handling of complex and large-scale applications. However, these systems face several challenges that can hinder their efficiency and effectiveness. This section delves into the key challenges in parallel and distributed systems, including scalability and performance, security and privacy, fault tolerance and reliability, interoperability and standardization, and energy efficiency.

5.1. Scalability and Performance

Achieving scalability while maintaining high performance is one of the foremost challenges in parallel and distributed systems. As the number of processors or nodes increases, bottlenecks can arise due to limitations in communication bandwidth, synchronization overhead, and resource contention [

147]. These issues can significantly degrade system performance, negating the benefits of adding more computational resources.

To address these challenges, several solutions have been proposed. Optimizing communication protocols [

148] reduces latency and improves data transfer rates between nodes. Implementing dynamic resource allocation [

149] ensures efficient allocation of computational resources based on workload demands, while adaptive scheduling algorithms [

150] dynamically adjust task scheduling to balance the load across processors. Additionally, replacing traditional electrical interconnects with optical interconnects [

151] or utilizing optical wireless communication [

152] offers higher bandwidth and lower latency, alleviating communication bottlenecks. These advancements help distribute workloads more evenly and enhance overall performance and scalability.

5.2. Security and Privacy

Security and privacy are paramount concerns in distributed environments where data and resources are shared across multiple nodes [

153]. Threats such as unauthorized access, data breaches, and malicious attacks can compromise the integrity and confidentiality of the system. Distributed systems are particularly vulnerable due to their open and interconnected nature, which can be exploited by attackers.

To safeguard against these threats, implementing robust data protection techniques is essential. Encryption methods, secure communication protocols, and authentication mechanisms can help protect data in transit and at rest [

154]. Additionally, adopting comprehensive security frameworks and adhering to best practices in cybersecurity can mitigate risks. Regular security assessments and updates are necessary to address emerging vulnerabilities and ensure compliance with privacy regulations.

5.3. Fault Tolerance and Reliability

Fault tolerance and reliability are critical in ensuring that parallel and distributed systems continue to operate correctly even in the presence of component failures [

155]. Hardware malfunctions, network issues, or software errors can lead to system downtime or data loss, which is unacceptable in mission-critical applications.

To enhance fault tolerance, error detection and recovery mechanisms must be integrated into the system architecture. Techniques such as redundancy, checkpointing, and replication can help the system recover from failures without significant disruption [

156]. Implementing self-healing algorithms that automatically detect and rectify faults can further improve system reliability. Ensuring robustness in system design minimizes the impact of failures and maintains consistent performance.

5.4. Interoperability and Standardization

In heterogeneous environments where diverse systems and technologies coexist, interoperability becomes a significant challenge [

157]. Orchestrating operations across different platforms, protocols, and interfaces requires careful coordination. Without standardization, integrating new components or scaling the system can lead to incompatibilities and increased complexity.

To facilitate seamless communication and collaboration among disparate systems, the adoption of standardized protocols and interfaces is essential [

158]. Embracing industry standards and open architectures can promote interoperability and ease integration efforts. Middleware solutions and APIs that abstract underlying differences can also aid in integrating heterogeneous components. Standardization efforts contribute to reducing development costs and fostering innovation through collaborative ecosystems.

5.5. Energy Efficiency

As parallel and distributed systems scale up, power consumption becomes a growing concern [

159]. High energy usage not only increases operational costs but also has environmental implications due to the carbon footprint associated with large data centres and computing clusters.

Implementing green computing practices is crucial to address energy efficiency challenges. This includes designing energy-efficient hardware, optimizing software to reduce computational overhead, and utilizing energy-aware scheduling algorithms [

160]. Techniques such as dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS) and power management protocols can help reduce power consumption without compromising performance. Emphasizing sustainability in system design contributes to long-term operational viability and environmental responsibility.

6. Future Directions

Building on the challenges outlined in this paper, it is evident that significant advancements are still needed to overcome scalability, energy efficiency, and security limitations in parallel and distributed systems. As these systems evolve, several emerging technologies and research areas show promise for addressing current obstacles and driving innovation. This section discusses the future directions of each class of parallel and distributed systems.

Heterogeneous computing As we move towards ultra-heterogeneous architectures, the focus shifts to developing intelligent scheduling algorithms that dynamically distribute workloads to the most appropriate processors, enhancing both performance and energy efficiency. Future research should prioritize advancing software frameworks that enable seamless communication between processors, as well as refining programming models like CUDA and OpenCL to simplify development. At the hardware level, the creation of high-bandwidth, low-latency interconnects and evolving memory architectures will be essential to support efficient data sharing. Innovations such as 3D stacking and co-packaging will further enhance performance by reducing communication delays between processors. Applications of ultra-heterogeneous systems will span AI, scientific computing, and real-time processing, driving unparalleled performance. As these architectures evolve, they will address current scalability challenges, becoming key enablers of future high-performance parallel systems.

Quantum Computing As quantum technologies rapidly advance, the development of qubits, such as superconducting, silicon-based, trapped-ion, and photonic qubits, will be central to driving quantum computing forward. Each qubit type offers unique advantages, contributing to a broad array of applications, including cryptography, optimization, and quantum system simulations. Future research should focus on improving qubit fidelity and scalability to enable the creation of practical quantum processors capable of handling thousands of qubits. The design of quantum algorithms that exploit superposition, entanglement, and interference will be critical for optimizing the performance of quantum computers in parallel systems. Hybrid quantum-classical architectures are also expected to emerge, integrating quantum processors as specialized units alongside classical systems to solve specific tasks more efficiently. A key area of growth is QML, which combines quantum computing with machine learning techniques to accelerate data processing in areas such as classification, pattern recognition, and autonomous systems. As research continues, quantum computing will complement other emerging technologies, significantly enhancing the capabilities of future parallel systems.

Neuromorphic Computing Inspired by the brain’s architecture, neuromorphic computing is rapidly emerging as a promising solution for achieving energy-efficient, event-driven processing, particularly in AI and machine learning tasks. Future research should focus on enhancing the scalability and programmability of neuromorphic hardware to enable larger, more complex systems capable of handling AI and machine learning tasks with improved efficiency. Developing Spike Neural Networks (SNNs) as the foundational algorithms for neuromorphic systems also requires further exploration, particularly in backpropagation and online learning to improve their adaptability and performance. Importantly, a key challenge is moving neuromorphic systems from experimental platforms to real-world applications, especially in AI, where they could complement or outperform current GPU-based architectures in energy efficiency. Developing standardized hardware protocols and community-maintained software frameworks will be also critical. Furthermore, neuromorphic computing’s close ties to neuroscience also offer exciting potential for advancing our understanding of brain function and refining AI models based on biological principles.

Optical computing As the demand for faster and more sustainable computing systems grows, optical computing is increasingly being applied in fields such as AI and telecommunications. Future research should focus on advancing photonic integrated circuits and improving core components like MRRs and MZIs to enhance the scalability of optical systems. The development of HOCS, which combines analogue and digital optical techniques, will be crucial for unlocking new AI-driven applications, such as neural networks and adaptive optics, where optical computing can significantly boost computational speed. In parallel, optical interconnects will play a pivotal role in improving data transmission within parallel computing systems. By replacing traditional electrical interconnects with optical ones, data can be transmitted at much higher speeds with lower latency, which is especially important for large-scale systems like data centres and supercomputers. Research should explore energy-efficient, low-latency optical interconnects to reduce bottlenecks in data transfer, particularly in high-performance computing environments. Moreover, optical neural networks offer a promising avenue for enabling AI systems to perform complex computations at speeds unattainable by traditional electronics. The focus on miniaturization techniques and materials science advancements will further drive the integration of optical systems into practical applications. As optical computing technologies mature, they are poised to revolutionize industries like telecommunications, AI, and scientific simulations, delivering unprecedented computational power and efficiency.

Blockchain and Distributed Ledgers Blockchain and DLTs present a decentralized, tamper-resistant way to ensure security and transparency in distributed systems. These technologies can be instrumental in enabling trustless, decentralized distributed systems for applications such as cloud computing, IoT, and supply chain management. Future research efforts should aim to improve the scalability of blockchain systems and develop lightweight consensus mechanisms like proof-of-stake, which can handle high transaction volumes without compromising security. Another area of exploration is the development of blockchain frameworks tailored for specific distributed computing applications, such as distributed file systems or decentralized cloud services.

Serverless Computing Serverless computing, which abstracts away infrastructure management and allows developers to focus purely on code execution, is emerging as a key paradigm in distributed systems. Serverless architectures can automatically scale based on demand, making them ideal for distributed applications with highly variable workloads. As serverless technologies evolve, future research should focus on improving the latency and scalability of serverless frameworks, particularly for HPC and real-time distributed systems. Additionally, exploring fine-grained resource management and serverless orchestration for parallel tasks distributed across multiple nodes will be critical for achieving more efficient and responsive distributed systems. The integration with AI/ML workflows and provision in a multi-cloud environment is essential to improve resource optimization while keeping the clod start delay as low as possible.

Cloud-Native Architectures Cloud-native architectures, which leverage the full potential of cloud environments for distributed computing, will continue to evolve to provide auto-scaling, fault tolerance, and resilient microservice-based applications. The next phase of cloud-native development will focus on improving the coordination and orchestration of microservices in distributed systems while maintaining data consistency across geographically dispersed cloud resources. Future research can also focus on improving containerization technologies like Kubernetes for more efficient resource allocation and fault-tolerant designs in distributed environments. Additionally, future research will be necessary to enhance sustainability through energy-efficient container scheduling and lifecycle management.

Distributed AI and Machine Learning Distributed AI and machine learning will be integral to the future of distributed systems, enabling real-time data processing, decision-making, and model training across multiple nodes. As AI and ML workloads become increasingly distributed, key challenges such as model synchronization, data transmission latency, and computational overhead need to be addressed. Future research should focus on developing efficient distributed learning frameworks, such as federated learning, that minimize the need for centralized data processing while ensuring model consistency across distributed nodes. Additionally, there is significant potential in exploring edge AI frameworks that can perform AI processing closer to data sources, thereby reducing latency and bandwidth usage.

7. Conclusions

This paper has provided a comprehensive overview of parallel and distributed systems, emphasizing their pivotal role in meeting the escalating computational demands of modern applications. By exploring their interrelationships and key distinctions, we established a foundation for understanding the emerging trends shaping their evolution. In the domain of parallel systems, we analyzed four emerging paradigms: heterogeneous computing, quantum computing, neuromorphic computing, and optical computing. In the sphere of distributed systems, we examined several emerging trends: blockchain and distributed ledgers, serverless computing, cloud-native architectures, and distributed AI and machine learning systems. Additionally, we discussed the challenges that persist in these systems, including scalability limitations, security and privacy concerns, fault tolerance, interoperability issues, and energy efficiency demands. Addressing these challenges is crucial for the continued evolution and broader adoption of parallel and distributed systems.

Future research should focus on advancing software frameworks, developing innovative hardware architectures, optimizing communication protocols, and designing efficient algorithms. By embracing these emerging trends and proactively tackling associated challenges, we can develop more powerful, efficient, and adaptable computing systems. Such advancements will drive innovation across various sectors, contribute to scientific and technological progress, and meet the complex demands of the future computational landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.; methodology, F.D.; validation, F.D., M. A. H., and Y. W.; investigation, F.D., M. A. H., and Y. W.; resources, F.D.; data curation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.; writing—review and editing, F.D., M. A. H., and Y. W.; visualization, F.D. and M. A. H.; funding acquisition, F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the editors and the Electronics Journal for their valuable support. We are also deeply grateful to the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive feedback, which have greatly enhanced the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, A.; Palesi, M.; Kim, J.; Pande, P.P. Chip and Package-Scale Interconnects for General-Purpose, Domain-Specific and Quantum Computing Systems-Overview, Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockney, R.W.; Jesshope, C.R. Hockney, R.W.; Jesshope, C.R. Parallel Computers 2: architecture, programming and algorithms; CRC Press, 2019.

- Navarro, C.A.; Hitschfeld-Kahler, N.; Mateu, L. A survey on parallel computing and its applications in data-parallel problems using GPU architectures. Communications in Computational Physics 2014, 15, 285–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Marrakchi, Z.; Mehrez, H.; Farooq, U.; Marrakchi, Z.; Mehrez, H. FPGA architectures: An overview. Tree-Based Heterogeneous FPGA Architectures: Application Specific Exploration and Optimization 2012, 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Halsted, D. The origins of the architectural metaphor in computing: design and technology at IBM, 1957–1964. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 2018, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawan, M.P.; Patle, B.; Cholake, V.; Pardeshi, S. Parallel Computer Architectural Schemes. International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology 2012, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Batcher. Design of a massively parallel processor. IEEE Transactions on Computers 1980, 100, 836–840. [Google Scholar]

- Leiserson, C.E.; Abuhamdeh, Z.S.; Douglas, D.C.; Feynman, C.R.; Ganmukhi, M.N.; Hill, J.V.; Hillis, D.; Kuszmaul, B.C.; St. Pierre, M.A.; Wells, D.S.; et al. The network architecture of the Connection Machine CM-5. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the fourth annual ACM symposium on Parallel algorithms and architectures, 1992, pp. 272–285.

- Alverson, B.; Froese, E.; Kaplan, L.; Roweth, D. Cray XC series network. Cray Inc., White Paper WP-Aries01-1112 2012.

- Keckler, S.W.; Hofstee, H.P.; Olukotun, K. Multicore processors and systems; Springer, 2009.

- McClanahan, C. History and evolution of gpu architecture. A Survey Paper 2010, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kshemkalyani, A.D.; Singhal, M. Distributed computing: principles, algorithms, and systems; Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Ali, M.F.; Khan, R.Z. Distributed computing: An overview. International Journal of Advanced Networking and Applications 2015, 7, 2630. [Google Scholar]

- Paloque-Bergès, C.; Schafer, V. Arpanet (1969–2019). Internet Histories 2019, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifati, A.; Chrysanthis, P.K.; Ouksel, A.M.; Sattler, K.U. Distributed databases and peer-to-peer databases: past and present. ACM SIGMOD Record 2008, 37, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwatosin, H.S. Client-server model. IOSR Journal of Computer Engineering 2014, 16, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Luo, Z.; Du, Y.; Guo, L. Cloud computing: An overview. In Proceedings of the Cloud Computing: First International Conference, CloudCom 2009, Beijing, China, December 1-4, 2009. Proceedings 1. Springer, 2009, pp. 626–631.

- Dittrich, J.; Quiané-Ruiz, J.A. Efficient big data processing in Hadoop MapReduce. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 2012, 5, 2014–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Meng, G.; Sun, Q. An overview on edge computing research. IEEE access 2020, 8, 85714–85728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madakam, S.; Ramaswamy, R.; Tripathi, S. Internet of Things (IoT): A literature review. Journal of Computer and Communications 2015, 3, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosta, S.H. Parallel processing and parallel algorithms: theory and computation; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Burns, B. Designing distributed systems: patterns and paradigms for scalable, reliable services; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2018.

- Parhami, B. Introduction to parallel processing: algorithms and architectures; Vol. 1, Springer Science & Business Media, 1999.

- Santoro, G.; Turvani, G.; Graziano, M. New logic-in-memory paradigms: An architectural and technological perspective. Micromachines 2019, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Grumbling, E. Quantum computing: progress and prospects 2019.

- Huang, H.L.; Wu, D.; Fan, D.; Zhu, X. Superconducting quantum computing: a review. Science China Information Sciences 2020, 63, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zolanvari, M.; Jain, R. A survey of important issues in quantum computing and communications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 1059–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Radtke, T.; Fritzsche, S. Simulation of n-qubit quantum systems. I. Quantum registers and quantum gates. Computer Physics Communications 2005, 173, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M. Quantum computer algorithms. PhD thesis, University of Oxford. 1999., 1999.

- Nofer, M.; Bauer, K.; Hinz, O.; van der Aalst, W.; Weinhardt, C. Quantum Computing. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2023, 65, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Zalba, M.; De Franceschi, S.; Charbon, E.; Meunier, T.; Vinet, M.; Dzurak, A. Scaling silicon-based quantum computing using CMOS technology. Nature Electronics 2021, 4, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, V.; Ballance, C.; Thirumalai, K.; Stephenson, L.; Ballance, T.; Steane, A.; Lucas, D. Fast quantum logic gates with trapped-ion qubits. Nature 2018, 555, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, T.; Song, Y.; Scott, J.; Poole, C.; Phuttitarn, L.; Jooya, K.; Eichler, P.; Jiang, X.; Marra, A.; Grinkemeyer, B.; et al. Multi-qubit entanglement and algorithms on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 2022, 604, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Lukin, M.D. Quantum optics with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Quantum Optics and Nanophotonics 2015, 229–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lukens, J.M.; Lougovski, P. Frequency-encoded photonic qubits for scalable quantum information processing. Optica 2017, 4, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- of Cyberspace Studies xiaxueping@ cac. gov. cn, C.A. World Information Technology Development. In Proceedings of the World Internet Development Report 2022: Blue Book for World Internet Conference. Springer, 2023, pp. 83–108.

- Mead, C. Neuromorphic electronic systems. Proceedings of the IEEE 1990, 78, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]