Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

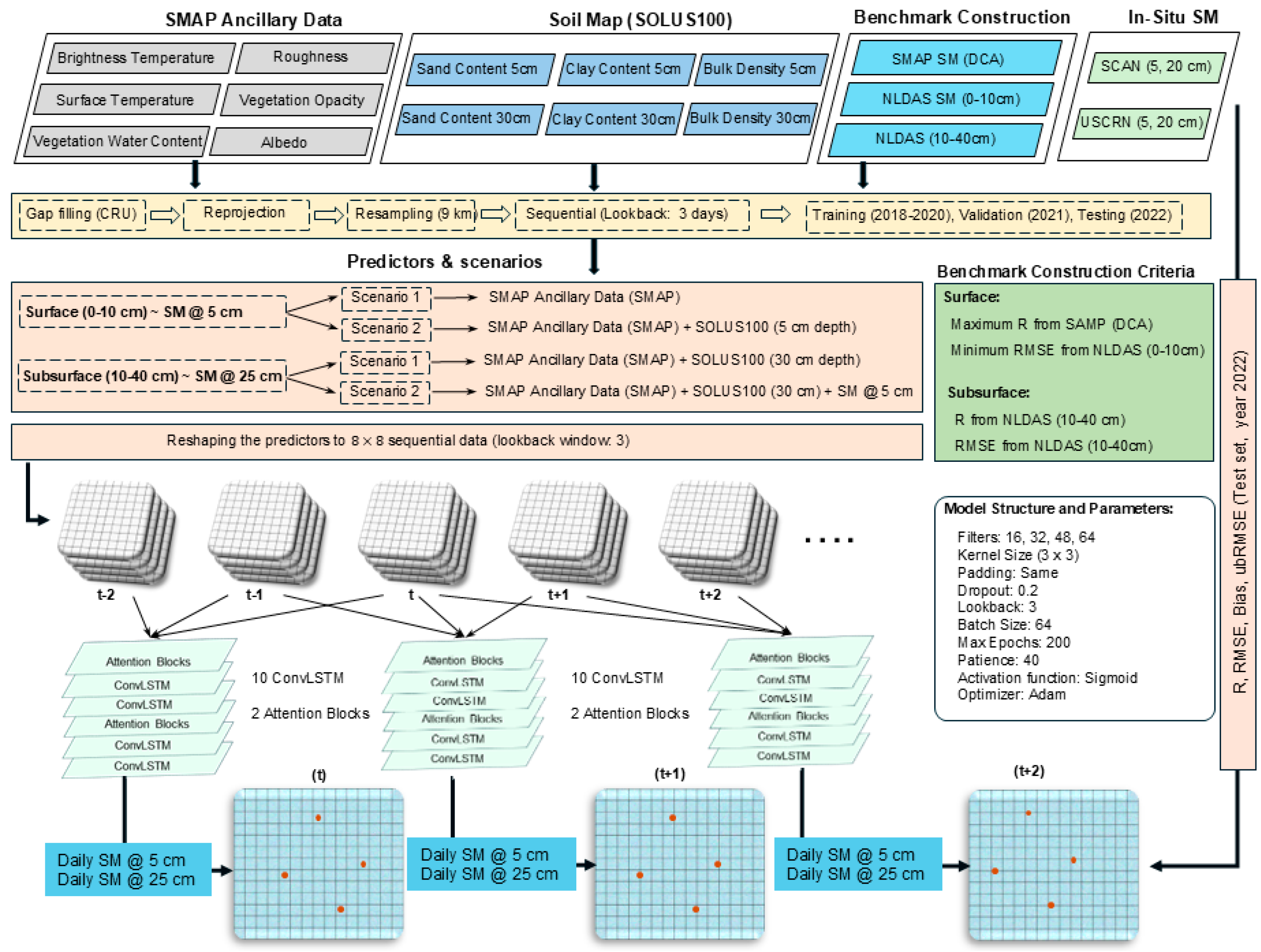

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SMAP Data and SOLUS100 Maps

2.2. Producing Benchmark Soil Moisture Data

2.3. Model Input Scenarios

2.4. ConvLSTM Model Architecture and Development

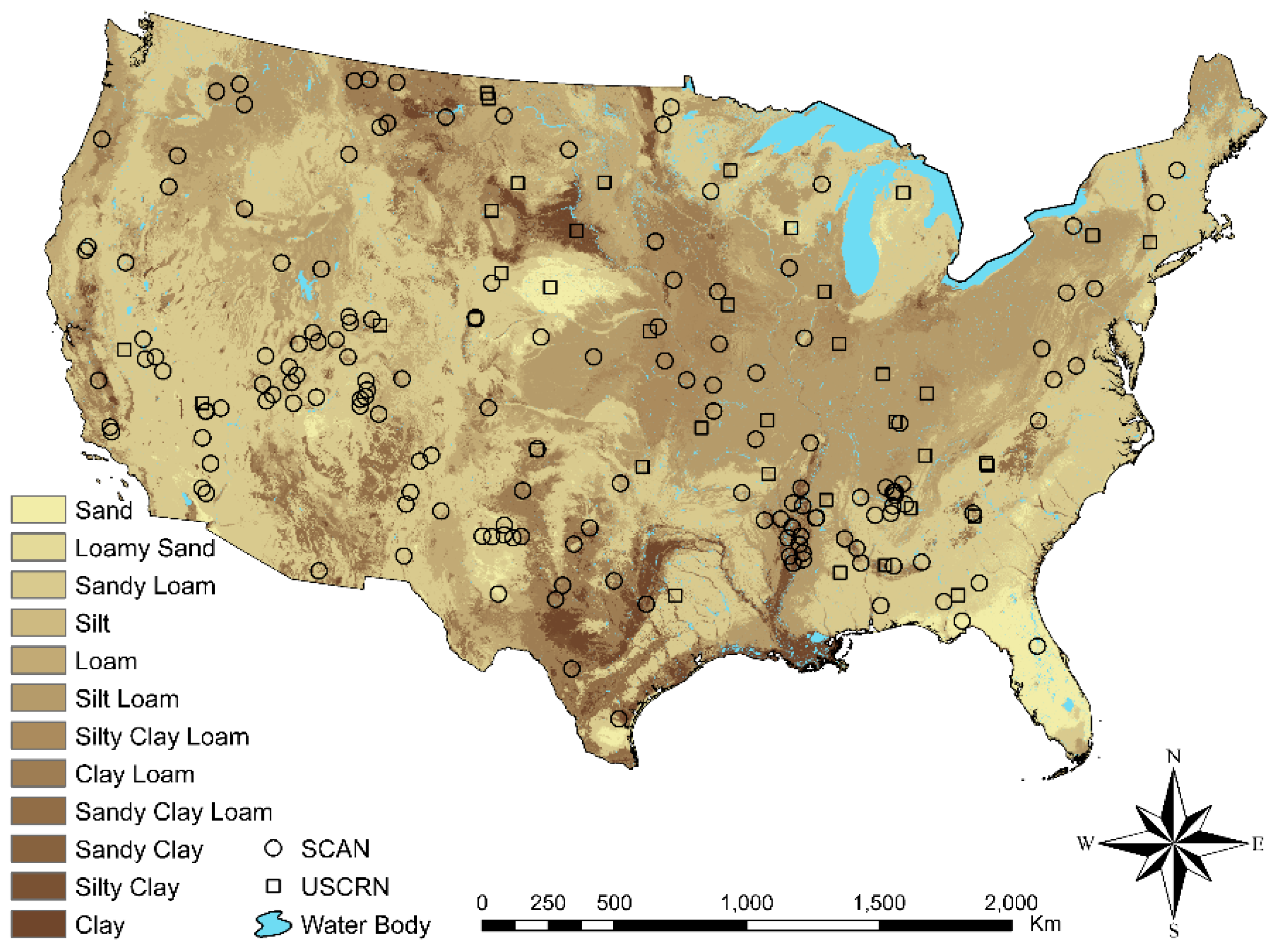

2.6. In Situ SM and Model Validation

3. Results and Discussion

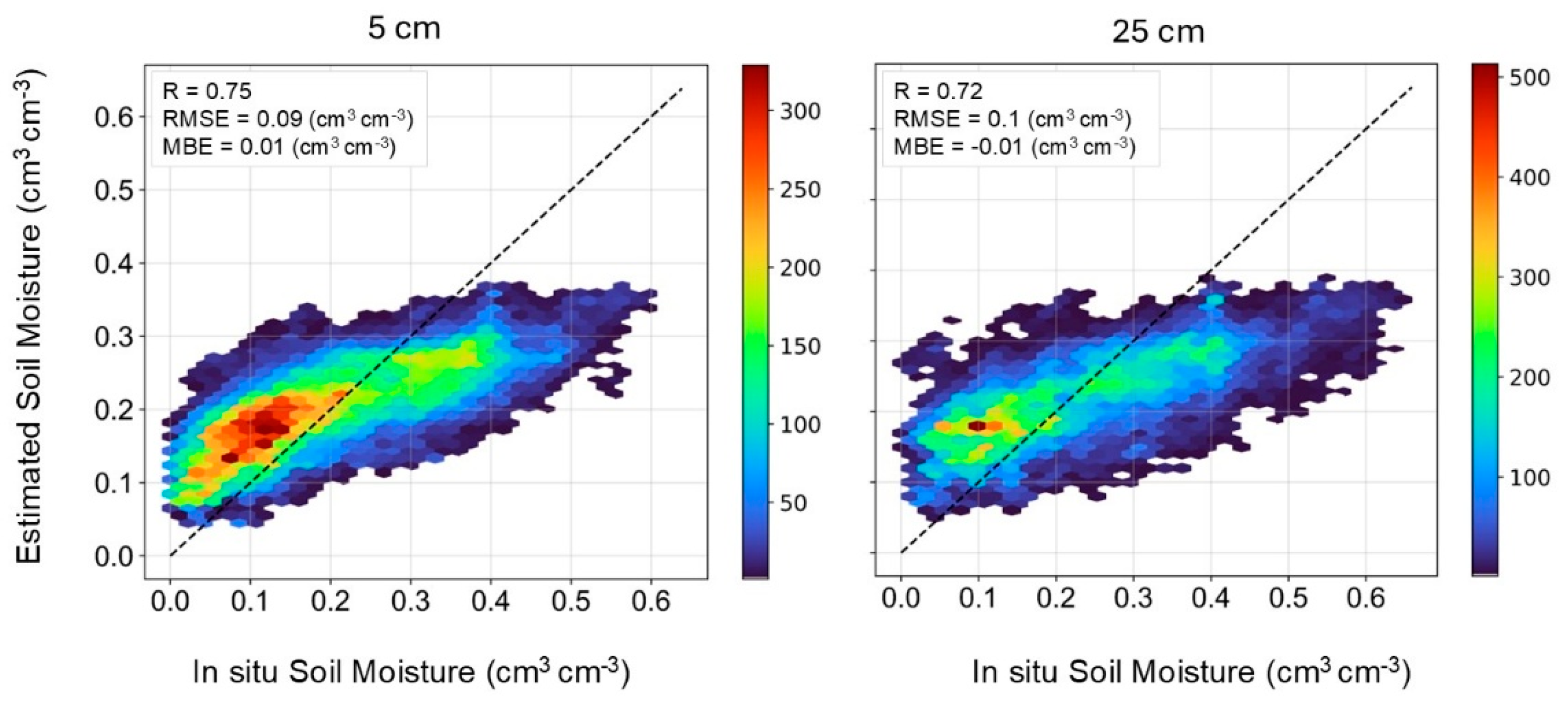

3.1. Surface and Subsurface SM Estimations with ConvLSTM

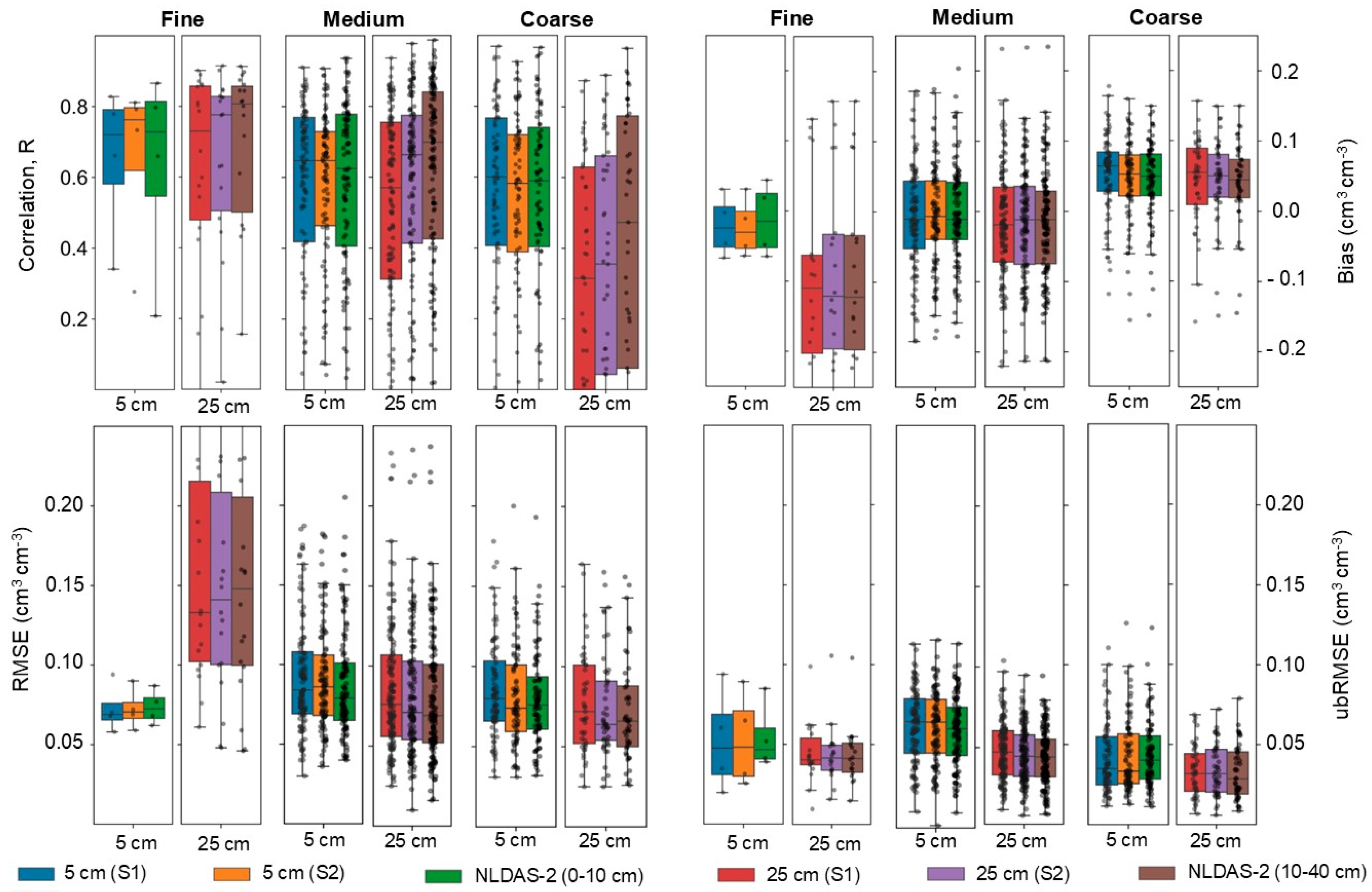

3.2. Effects of Soil Texture on Soil Moisture Estimation

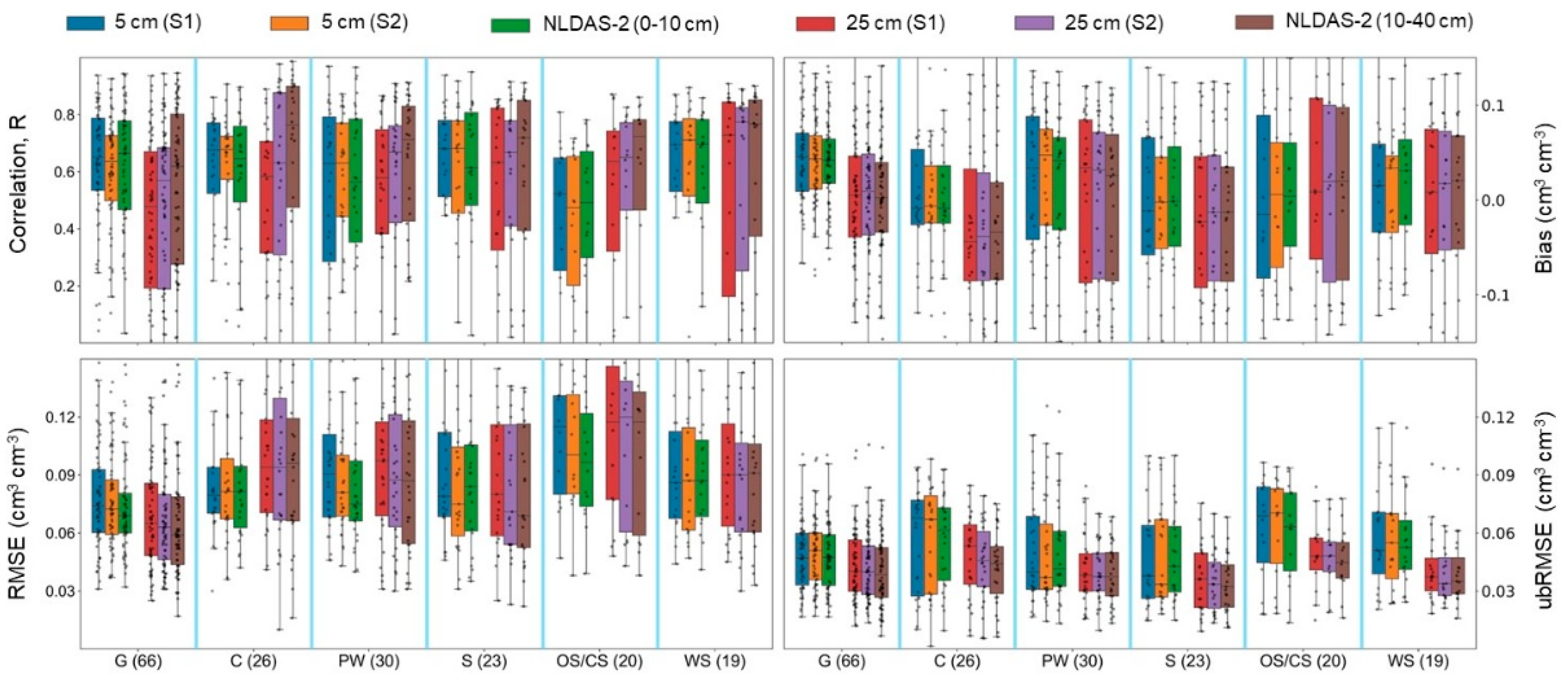

3.3. Effects of Land Cover Types on Soil Moisture Estimation

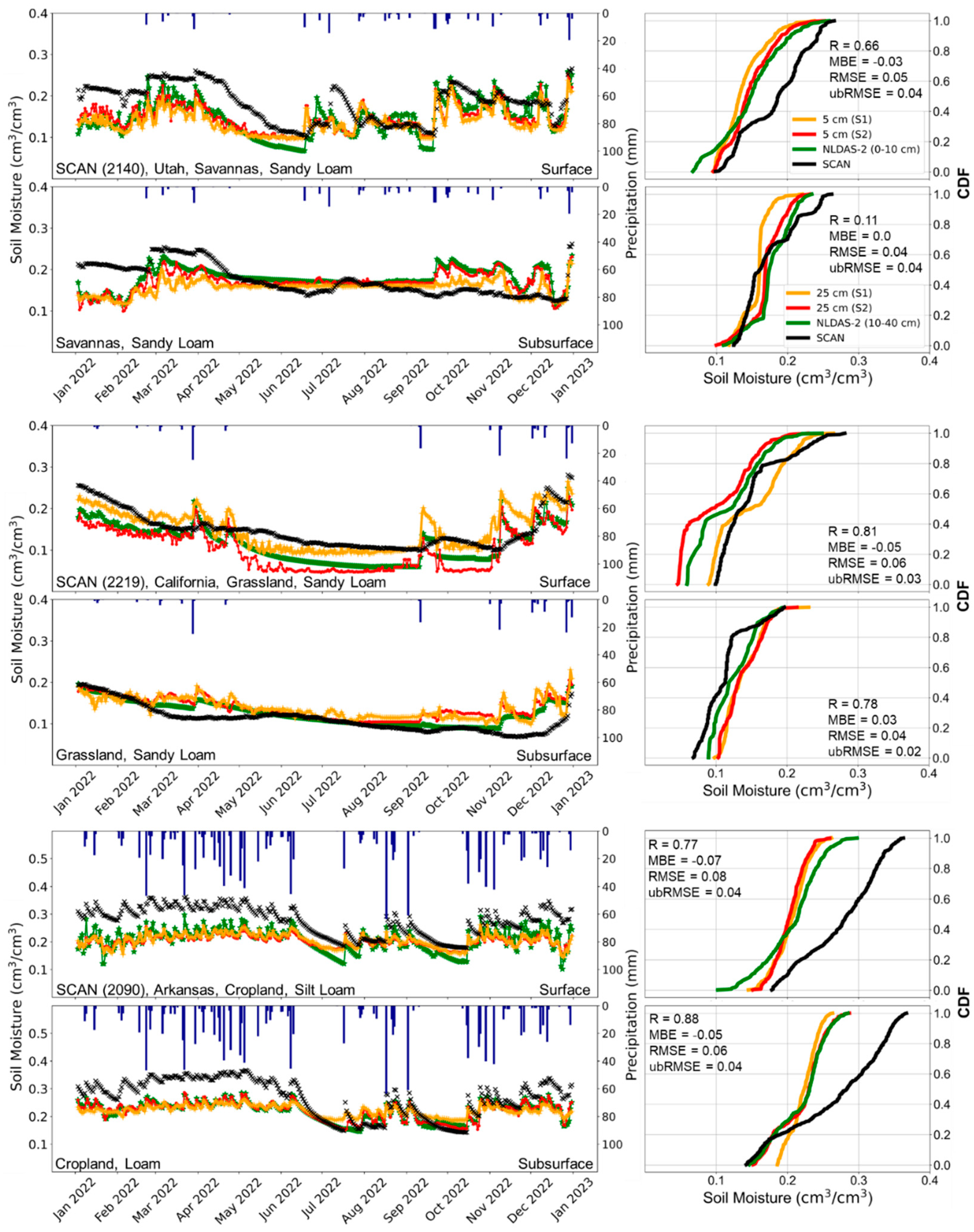

3.4. Spatiotemporal Validation of Soil Moisture Estimates

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vereecken, H.; Schnepf, A.; Hopmans, J.W.; Javaux, M.; Or, D.; Roose, T.; Vanderborght, J.; Young, M.H.; Amelung, W.; Aitkenhead, M. Modeling Soil Processes: Review, Key Challenges, and New Perspectives. Vadose zone journal 2016, 15, vzj2015-09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Sadeghi, M.; Jones, S.B.; Montzka, C.; Vereecken, H.; Tuller, M. Ground, Proximal, and Satellite Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture. Reviews of Geophysics 2019, 57, 530–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, B.; Srinivasan, R. Development and Evaluation of Soil Moisture Deficit Index (SMDI) and Evapotranspiration Deficit Index (ETDI) for Agricultural Drought Monitoring. Agric For Meteorol 2005, 133, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbiato, D.; Borga, M.; Degli Esposti, S.; Gaume, E.; Anquetin, S. Flash Flood Warning Based on Rainfall Thresholds and Soil Moisture Conditions: An Assessment for Gauged and Ungauged Basins. J Hydrol (Amst) 2008, 362, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.D.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; Guo, Z.; Bonan, G.; Chan, E.; Cox, P.; Gordon, C.T.; Kanae, S.; Kowalczyk, E.; Lawrence, D. Regions of Strong Coupling between Soil Moisture and Precipitation. Science (1979) 2004, 305, 1138–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.A.; Wagner, W.; Hohensinn, R.; Hahn, S.; Paulik, C.; Xaver, A.; Gruber, A.; Drusch, M.; Mecklenburg, S.; Van Oevelen, P. The International Soil Moisture Network: A Data Hosting Facility for Global in Situ Soil Moisture Measurements. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2011, 15, 1675–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T. An Overview of the” Triangle Method” for Estimating Surface Evapotranspiration and Soil Moisture from Satellite Imagery. Sensors 2007, 7, 1612–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.-G.; Liu, Y.-R.; Zhou, F. Estimation of Soil Moisture Using Trapezoidal Relationship between Remotely Sensed Land Surface Temperature and Vegetation Index. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2011, 15, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafian, S.; Maas, S.J. Index of Soil Moisture Using Raw Landsat Image Digital Count Data in Texas High Plains. Remote Sens (Basel) 2015, 7, 2352–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, S.; Jalilvand, E.; Tajrishy, M. A Method to Estimate Surface Soil Moisture and Map the Irrigated Cropland Area Using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.S.; Clarke, T.R.; Inoue, Y.; Vidal, A. Estimating Crop Water Deficit Using the Relation between Surface-Air Temperature and Spectral Vegetation Index. Remote Sens Environ 1994, 49, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Babaeian, E.; Tuller, M.; Jones, S.B. The Optical Trapezoid Model: A Novel Approach to Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture Applied to Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Observations. Remote Sens Environ 2017, 198, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Tuller, M. The Feasibility of Remotely Sensed Near-Infrared Reflectance for Soil Moisture Estimation for Agricultural Water Management. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Z.-L. Sensitivity Study of Soil Moisture on the Temporal Evolution of Surface Temperature over Bare Surfaces. Int J Remote Sens 2013, 34, 3314–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F.T. Microwave Remote Sensing, Active and Passive. Microwave Remote Sensing Fundamentals and Radiometry 1981, 1, 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mironov, V.L.; Kosolapova, L.G.; Fomin, S. V Physically and Mineralogically Based Spectroscopic Dielectric Model for Moist Soils. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2009, 47, 2059–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entekhabi, D.; Njoku, E.G.; O’neill, P.E.; Kellogg, K.H.; Crow, W.T.; Edelstein, W.N.; Entin, J.K.; Goodman, S.D.; Jackson, T.J.; Johnson, J. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Mission. Proceedings of the IEEE 2010, 98, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-H.; Jagdhuber, T.; Colliander, A.; Lee, J.; Berg, A.; Cosh, M.; Kim, S.-B.; Kim, Y.; Wulfmeyer, V. Parameterization of Vegetation Scattering Albedo in the Tau-Omega Model for Soil Moisture Retrieval on Croplands. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Fan, L.; Frappart, F.; Yueh, S.H.; Colliander, A.; Ebtehaj, A.; Gao, L.; Fernandez-Moran, R.; Liu, X. A New SMAP Soil Moisture and Vegetation Optical Depth Product (SMAP-IB): Algorithm, Assessment and Inter-Comparison. Remote Sens Environ 2022, 271, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, E.G.; Jackson, T.J.; Lakshmi, V.; Chan, T.K.; Nghiem, S. V Soil Moisture Retrieval from AMSR-E. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and remote sensing 2003, 41, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ebtehaj, A.; Chaubell, M.J.; Sadeghi, M.; Li, X.; Wigneron, J.-P. Reappraisal of SMAP Inversion Algorithms for Soil Moisture and Vegetation Optical Depth. Remote Sens Environ 2021, 264, 112627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.K.; Bindlish, R.; O’Neill, P.E.; Njoku, E.; Jackson, T.; Colliander, A.; Chen, F.; Burgin, M.; Dunbar, S.; Piepmeier, J. Assessment of the SMAP Passive Soil Moisture Product. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2016, 54, 4994–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, P.; Bindlish, R.; Chan, S.; Njoku, E.; Jackson, T. Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document. Level 2 & 3 Soil Moisture (Passive) Data Products. 2018.

- Chan, S.K.; Bindlish, R.; O’Neill, P.; Jackson, T.; Njoku, E.; Dunbar, S.; Chaubell, J.; Piepmeier, J.; Yueh, S.; Entekhabi, D.; et al. Development and Assessment of the SMAP Enhanced Passive Soil Moisture Product. Remote Sens Environ 2018, 204, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , Li, L., Whiting, M., Chen, F., Sun, Z., Song, K., & Wang, Q. Convolutional neural network model for soil moisture prediction and its transferability analysis based on laboratory Vis-NIR spectral data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2021,104, 102550.

- Dorigo, W.; Wagner, W.; Albergel, C.; Albrecht, F.; Balsamo, G.; Brocca, L.; Chung, D.; Ertl, M.; Forkel, M.; Gruber, A. ESA CCI Soil Moisture for Improved Earth System Understanding: State-of-the Art and Future Directions. Remote Sens Environ 2017, 203, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichle, R.H.; Liu, Q.; Koster, R.D.; Crow, W.T.; De Lannoy, G.J.M.; Kimball, J.S.; Ardizzone, J. V; Bosch, D.; Colliander, A.; Cosh, M. Version 4 of the SMAP Level--4 Soil Moisture Algorithm and Data Product. J Adv Model Earth Syst 2019, 11, 3106–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Mitchell, K.; Ek, M.; Sheffield, J.; Cosgrove, B.; Wood, E.; Luo, L.; Alonge, C.; Wei, H.; Meng, J. Continental--scale Water and Energy Flux Analysis and Validation for the North American Land Data Assimilation System Project Phase 2 (NLDAS--2): 1. Intercomparison and Application of Model Products. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, G.; Beljaars, A.; Scipal, K.; Viterbo, P.; van den Hurk, B.; Hirschi, M.; Betts, A.K. A Revised Hydrology for the ECMWF Model: Verification from Field Site to Terrestrial Water Storage and Impact in the Integrated Forecast System. J Hydrometeorol 2009, 10, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ek, M.B.; Wu, Y.; Ford, T.; Quiring, S.M. Comparison of NLDAS-2 Simulated and NASMD Observed Daily Soil Moisture. Part I: Comparison and Analysis. J Hydrometeorol 2015, 16, 1962–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, E.; Reichle, R.H.; Colliander, A.; Cosh, M.H.; Smith, L. Validation of Remotely Sensed and Modeled Soil Moisture at Forested and Unforested NEON Sites. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Y.-A.; Liu, S.-F.; Wang, W.-J. Retrieving Soil Moisture from Simulated Brightness Temperatures by a Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2001, 39, 1662–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa, J.; Reichle, R.H.; Liu, Q.; Alemohammad, S.H.; Gentine, P.; Aida, K.; Asanuma, J.; Bircher, S.; Caldwell, T.; Colliander, A. Estimating Surface Soil Moisture from SMAP Observations Using a Neural Network Technique. Remote Sens Environ 2018, 204, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, P.; Moradkhani, H.; Gavahi, K.; Kumar, S.; Hain, C.; Zhan, X.; Duan, Q.; Peters-Lidard, C.; Karimiziarani, S. High-Resolution SMAP Satellite Soil Moisture Product: Exploring the Opportunities. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 2021, 102, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, L.; Mishra, A.K. Multi-Layer High-Resolution Soil Moisture Estimation Using Machine Learning over the United States. Remote Sens Environ 2021, 266, 112706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.M.; Colwell, I.; Chew, C.; Lowe, S.; Shah, R. A Deep-Learning Approach to Soil Moisture Estimation with GNSS-R. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Li, X.; Fu, P.; Cosh, M.H.; Letu, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, N. Surface Soil Moisture from Combined Active and Passive Microwave Observations: Integrating ASCAT and SMAP Observations Based on Machine Learning Approaches. Remote Sens Environ 2024, 308, 114197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Chaubell, M.J.; Ebtehaj, A.; Shen, L.; Wigneron, J.-P. A Deep Neural Network Based SMAP Soil Moisture Product. Remote Sens Environ 2022, 277, 113059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.D.; Guo, Z.; Yang, R.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; Mitchell, K.; Puma, M.J. On the Nature of Soil Moisture in Land Surface Models. J Clim 2009, 22, 4322–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhangzhong, L.; Xue, X. Research on Soil Moisture Prediction Model Based on Deep Learning. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0214508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, S.; Sharma, A.; Sahu, S.S. Soil Moisture Prediction Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 Second International Conference on Inventive Communication and Computational Technologies (ICICCT); IEEE; 2018; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.-Y.; Wong, W.-K.; Woo, W. Convolutional LSTM Network: A Machine Learning Approach for Precipitation Nowcasting. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional Neural Networks: An Overview and Application in Radiology. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation MIT-Press.

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, D.; Xie, S.; Xu, J. ConvLSTM Network-Based Rainfall Nowcasting Method with Combined Reflectance and Radar-Retrieved Wind Field as Inputs. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Pan, B.; Wang, H.; Hsu, K.; Sorooshian, S. Improving Monsoon Precipitation Prediction Using Combined Convolutional and Long Short Term Memory Neural Network. Water (Basel) 2019, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Paheding, S.; Siddique, N.; Devabhaktuni, V.K.; Tuller, M. Short-and Mid-Term Forecasts of Actual Evapotranspiration with Deep Learning. J Hydrol (Amst) 2022, 612, 128078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, N.; Jia, X.; Guo, L.; Qiu, R.; Shao, M. Estimating Crop Evapotranspiration of Wheat-Maize Rotation System Using Hybrid Convolutional Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Network with Grey Wolf Algorithm in Chinese Loess Plateau Region. Agric Water Manag 2024, 301, 108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moishin, M.; Deo, R.C.; Prasad, R.; Raj, N.; Abdulla, S. Designing Deep-Based Learning Flood Forecast Model with ConvLSTM Hybrid Algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50982–50993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, A.; Moazam, H.M.Z.H.; Mortazavizadeh, F.; Ranjbar, V.; Mirzaei, M.; Mortezavi, S.; Ng, J.L.; Dehghani, A. Comparative Evaluation of LSTM, CNN, and ConvLSTM for Hourly Short-Term Streamflow Forecasting Using Deep Learning Approaches. Ecol Inform 2023, 75, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Paheding, S.; Siddique, N.; Devabhaktuni, V.K.; Tuller, M. Estimation of Root Zone Soil Moisture from Ground and Remotely Sensed Soil Information with Multisensor Data Fusion and Automated Machine Learning. Remote Sens Environ 2021, 260, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Environmental Soil Physics: Fundamentals, Applications, and Environmental Considerations; Elsevier Science, 2014; ISBN 0080544150.

- Colliander, A. , Reichle, R. H., Crow, W. T., Cosh, M. H., Chen, F., Chan, S., Das, N. N., Bindlish, R., Chaubell, J., Kim, S., Liu, Q., O’Neill, P. E., Dunbar, R. S., Dang, L. B., Kimball, J. S., Jackson, T. J., Al-Jassar, H. K., Asanuma, J., Bhattacharya, B. K., … Yueh, S. H. (2022). Validation of Soil Moisture Data Products from NASA SMAP Mission. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 15, 364–392. [CrossRef]

- Nauman, T.W.; Kienast--Brown, S.; Roecker, S.M.; Brungard, C.; White, D.; Philippe, J.; Thompson, J.A. Soil Landscapes of the United States (SOLUS): Developing Predictive Soil Property Maps of the Conterminous United States Using Hybrid Training Sets. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sheffield, J.; Ek, M.B.; Dong, J.; Chaney, N.; Wei, H.; Meng, J.; Wood, E.F. Evaluation of Multi-Model Simulated Soil Moisture in NLDAS-2. J Hydrol (Amst) 2014, 512, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Fan, L.; Xie, Z.; Gao, L.; Xing, Z.; Ma, H.; Boudah, A.; Zhou, H. Assessment of Five SMAP Soil Moisture Products Using ISMN Ground-Based Measurements over Varied Environmental Conditions. J Hydrol (Amst) 2023, 619, 129325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.G. The Accuracy of Digital Elevation Models Interpolated to Higher Resolutions. Int J Remote Sens 2000, 21, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, M.; Eltayeb, M.; Lessmann, S.; Rudolph, M. Modeling Irregular Time Series with Continuous Recurrent Units. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning; PMLR; 2022; pp. 19388–19405. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, P.; Faroughi, S.A. A Multihead LSTM Technique for Prognostic Prediction of Soil Moisture. Geoderma 2023, 433, 116452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03167, arXiv:1502.03167 2015.

- Cui, H.; Yuwen, C.; Jiang, L.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y. Multiscale Attention Guided U-Net Architecture for Cardiac Segmentation in Short-Axis MRI Images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2021, 206, 106142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jun, F.; Cheng, Z. Spatio-Temporal Attention LSTM Model for Flood Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Internet of Things (IThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, 2019, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData); IEEE; pp. 458–465.

- Vaswani, A. Attention Is All You Need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, G.L.; Cosh, M.H.; Jackson, T.J. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Soil Climate Analysis Network (SCAN). J Atmos Ocean Technol 2007, 24, 2073–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; Palecki, M.A.; Baker, C.B.; Collins, W.G.; Lawrimore, J.H.; Leeper, R.D.; Hall, M.E.; Kochendorfer, J.; Meyers, T.P.; Wilson, T. US Climate Reference Network Soil Moisture and Temperature Observations. J Hydrometeorol 2013, 14, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulla-Menashe, D.; Gray, J.M.; Abercrombie, S.P.; Friedl, M.A. Hierarchical Mapping of Annual Global Land Cover 2001 to Present: The MODIS Collection 6 Land Cover Product. Remote Sens Environ 2019, 222, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, K.E.; Rawls, W.J. Soil Water Characteristic Estimates by Texture and Organic Matter for Hydrologic Solutions. Soil science society of America Journal 2006, 70, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.; Mohanty, B.P. Physical Controls of Near--surface Soil Moisture across Varying Spatial Scales in an Agricultural Landscape during SMEX02. Water Resour Res 2010, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gaines, R.A.; Frankenstein, S. USCS and the USDA Soil Classification System: Development of a Mapping Scheme. 2015.

- Zhao, L.; Yang, K.; He, J.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, D. Potential of Mapping Global Soil Texture Type from SMAP Soil Moisture Product: A Pilot Study. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land-cover type | Model | SCAN | USCRN | |||||||

| R | RMSE | Bias | unRMSE | R | RMSE | Bias | unRMSE | |||

| (-) | cm3 cm-3 | (-) | cm3 cm-3 | |||||||

| Grasslands | DCA | 0.63 | 0.070 | 0.008 | 0.057 | 0.69 | 0.079 | -0.02 | 0.050 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.65 | 0.073 | 0.031 | 0.053 | 0.60 | 0.070 | 0.014 | 0.049 | ||

| Croplands | DCA | 0.55 | 0.094 | -0.01 | 0.069 | 0.68 | 0.093 | -0.06 | 0.056 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.54 | 0.092 | -0.01 | 0.066 | 0.54 | 0.078 | -0.04 | 0.065 | ||

| Permanent Wetlands | DCA | 0.64 | 0.077 | 0.011 | 0.056 | 0.66 | 0.116 | 0.019 | 0.051 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.60 | 0.081 | 0.022 | 0.050 | 0.59 | 0.091 | -0.01 | 0.055 | ||

| Woody Savannas | DCA | 0.62 | 0.111 | 0.076 | 0.064 | 0.72 | 0.104 | 0.051 | 0.049 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.58 | 0.089 | 0.021 | 0.062 | 0.53 | 0.078 | 0.004 | 0.050 | ||

| Savannas | DCA | 0.66 | 0.085 | 0.020 | 0.054 | 0.78 | 0.098 | 0.069 | 0.045 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.64 | 0.086 | 0.017 | 0.053 | 0.65 | 0.078 | 0.015 | 0.044 | ||

| Open and Closed Shrubland | DCA | 0.61 | 0.126 | 0.090 | 0.056 | 0.69 | 0.095 | 0.034 | 0.042 | |

| NLDAS-2 | 0.57 | 0.098 | 0.014 | 0.054 | 0.50 | 0.071 | -0.02 | 0.050 | ||

| R: Pearson correlation; RMSE: Root mean squared error; Bias: Mean bias error; unRMSE: Unbiased RMSE | ||||||||||

| Soil Layer (cm) | Scenarios | Predictors | SMAP SM (DCA) | NLDAS-2 SM | ||

| RMSE | R | RMSE | R | |||

| Surface (5 cm) |

1 | SMAP ancillary data | * | * | ||

| 2 | SMAP ancillary data, SLOUS* | * | * | |||

| Subsurface (25 cm) |

1 | SMAP ancillary data, SOLUS** | * | * | ||

| 2 | SMAP ancillary data, SOLUS**, SM @ 5 cm | * | * | |||

| SOLUS*: Sand, Silt, Clay and Bulk density maps at surface soil layer (5 cm) SOLUS**: Sand, Silt, Clay and Bulk density maps at subsurface soil layer (25 cm) SM @ 5 cm: Estimated soil moisture at depth 5 cm. | ||||||

| Soil Depth (cm) | Scenario* | R | RMSE (cm3 cm-3) |

Bias (cm3 cm-3) |

ubRMSE (cm3 cm-3) |

| 0 – 10 cm | 1 | 0.54 | 0.089 | 0.017 | 0.053 |

| 2 | 0.54 | 0.086 | 0.016 | 0.053 | |

| 10 – 40 cm | 1 | 0.45 | 0.090 | -0.01 | 0.043 |

| 2 | 0.51 | 0.086 | -0.008 | 0.041 | |

| *Scenario 1: SMAP ancillary data; Scenario 2: SMAP ancillary data and SOLUS100 maps. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).