1. Introduction

Phage therapy is one of the promising approaches to the treatment of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Strathdee SA et al., 2023; Cui L et al., 2024). This approach is especially relevant due to the wide spread of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains. However, natural phages can have low lytic activity against the target infectious strain. The design of synthetic phages based on natural bacteriophages opens up new possibilities for phage therapy. A targeted combination of genetic elements can lead to the control of specificity and other characteristics of the phage (Dunne M et al., 2021).

The success of the rational design of therapeutic bacteriophages depends on several factors. First, this requires effective methods of editing and assembling phage genomes. Currently, a number of such methods have been developed, including transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning in yeast (also known as gap repair cloning), the assembly of phage genomes by the Gibson method, and various recombination methods inside bacterial host cells like bacteriophage recombining of electroporated DNA (BRED) (Marinelli LJ et al., 2008; Gibson DG et al., 2008; Ando H et al., 2015). Using these approaches, it has been successfully demonstrated that bacteriophages can be redirected from one bacterium to another both within the genus and between genera (Ando H et al., 2015; Latka A et al., 2021). Second, predictable phage design requires detailed knowledge of the mechanisms of phage infection and replication, as well as the structural organization of the virion. Modern structural methods, such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microcopy, provide detailed structures of both individual proteins and whole virions; however, such methods are time-consuming, whereas the variety of phages is enormous. The deficiency of structural data can be partially compensated using AI-based structure prediction methods such as AlphaFold 2, AlphaFold 3, and similar methods (Abramson J et al., 2024; Krishna R et al., 2024). As for understanding the mechanisms of infection, many details have been revealed last years. However, most of these experiments have been carried out on popular laboratory phages T4, T7, and lambda (Leiman PG et al., 2004; Cuervo A et al., 2019; Chen W et al., 2021). Furthermore, annotated phage genomes often contain many genes whose functions are unknown, indicating an incomplete understanding of phage biology.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a type of pathogenic bacterium that has developed resistance to many different types of antibiotics. This bacterium has been included in the World Health Organization’s ESKAPE group of pathogens due to its resistance and ability to cause serious infections. Therefore, the creation of therapeutic phages against K. pneumoniae is an important task. Klebsiella cells are surrounded by a protective polysaccharide capsule and more than 80 different capsule serotypes have been identified (Patro LPP et al., 2020). To date, several studies have been published on the construction of synthetic phages that infect Klebsiella (Ando H et al., 2015; Shen J et al., 2018; Latka A et al., 2021; Meile S et al., 2023; Wang C et al., 2024). This study was focused on two K. pneumoniae lytic phages KP192 and KP195 with podovirus morphology (GenBank id: NC_047968.1 and NC_047970.1, respectively). These phages belong to the Przondovirus genus, show 83% intergenomic similarity, and infect K. pneumoniae strains with different capsule serotypes. In this study, the role of the phage scaffold (the main part of the synthetic phage genome, excluding the transplanted genes) was investigated. For this purpose, several variants of synthetic phages were constructed based on the KP192 and KP195 genomes with the swapped genes encoding tail spike proteins. The exchange of the tail spike proteins that are responsible for recognition and degradation of capsular polysaccharide resulted in a switch in the host specificity of synthetic phages. In addition, significant changes in the reproduction efficiency of the resulting phages and the efficiency of Klebsiella lysis were also observed.

2. Methods

2.1. Phages, Bacterial and Yeast Strains

Two Klebsiella phages “KP32_isolate 192” and “KP32_isolate 195” (hereinafter KP192 and KP195, GenBank id: NC_047968 and NC_047970, respectively) from the Collection of Extremophilic Microorganisms and Type Cultures (CEMTC) of the Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine SB RAS, Novosibirsk, were used in this study. E. coli TOP10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and yeast strain BY4741 (ATCC 4040002) were also used. K. pneumoniae strains of capsular K-type K37 (strain 2274, also referred to as strain A), K-type K2 (strains 2291 (strain B), 2573 (strain C) and 3533 (strain D)) and K-type K64 (strain 2337, also referred to as strain E) were also used. The K-types for these strains were determined previously using wzi gene sequencing (GenBank id’s: MN371474, MN371475, MN371483, MN371512 and MN371476, respectively) (Morozova V et al., 2019).

2.2. Culturing Conditions

Klebsiella and E. coli were grown at 37°C on LB agar plates or in liquid LB medium with agitation (180 rpm). Liquid cultures of S. cerevisiae were grown at 27−30°C and agitation (180 rpm) in rich YPD medium or selective YNB-Leu medium (0.67% Yeast Nitrogen Base with ammonium sulfate (BD), 2% dextrose, 0.069% CSM-Leu (MP bio)); yeast colonies were grown on YNB-Leu agar plates at room temperature.

2.3. Preparation of PCR Products for Assembly of Phage Genomes

Overlapping DNA fragments of phage genomes were PCR-amplified using oligonucleotide pairs (

Table S1) and Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A small drop (0.1−0.2 ul) of bacteriophage solution was used as a matrix. The vector fragment was amplified from the yeast centromeric plasmid pRSII-415 (Addgene #35454) using primers pRSII415_192/5_genome_dir and pRSII415_192/5_genome_rev (

Table S1). All the fragments were purified using GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and quantified using Nanodrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.4. Phage Genome Assembly in Yeast

Transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning in yeast was used for genome assembly (Larionov V et al., 1996; Gibson DG et al., 2008; Jaschke PR et al., 2012). Competent yeast cells of strain BY4741 were prepared for this purpose (Gietz D et al., 1992; Gietz RD, 2014). All phage genome fragments (300 ng each) along with the vector fragment (300 ng) were mixed with transformation mixture (240 ul 50% PEG-3350, 36 ul 1M lithium acetate, 25 ul of denatured salmon sperm DNA (2 mg/ml)) in a total volume of 360 ul. Approximately 108 fresh competent yeast cells were added to the mixture and mixed. Cell suspension was incubated at 42°C for 30−60 min. Yeast cells were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30s, pellet was resuspended in 200 ul of sterile water. Yeast colonies were selected on YNB-Leu agar plates at room temperature for 3−4 days.

2.5. Yeast Colony Screening

Yeast colonies were screened by PCR in several steps. At the first step, the presence of a junction between the pt9 genome fragment and the vector part was confirmed using primers KP192/5_40225_dir and pRSII415_screening_rev (

Table S2). The presence of a junction between fragments pt4 and pt5 was then confirmed for positive clones using primers pt5_dir and pt4_rev. Finally, the presence of a junction between fragments pt1 and pt2 was confirmed using primers pt2_dir and pt1_rev. Those clones for which all three PCRs were positive were considered positive.

2.6. Isolation of a Yeast Centromeric Plasmid Containing the Bacteriophage Genome

Several positive colonies were transferred into YNB-Leu medium and grown at 30°C and 180 rpm until an optical density until the optical density OD600 reaches 6−9. Total yeast DNA containing pRS plasmid bearing the phage genome was extracted from yeast cells as previously described (Ando H et al., 2015; Latka A et al., 2021).

2.7. Phage Genome “Rebooting”

One Shot TOP10 electrocompetent E. coli cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for transformation as an initial phage propagation host. 50 ul of electrocompetent cells were mixed in a cuvette with 3 µl of a yeast DNA sample containing the phage genome. The cells were transformed in a 2 mm gap electroporation cuvette by applying an exponential pulse of 2500 V (capacitance discharge circuit parameters were 25 uF and 200 Ohm, time constant was 5 msec). Cells were mixed with SOC medium and incubated at 37C for 1−4 hours with agitation at 180 rpm. Cells were lysed by addition of 50 ul of chloroform followed by shaking using Vortex-Genie 2 mixer (Scientific Industries). Cleared lysate was mixed with 0.5 ml of overnight or exponential Klebsiella cells and 4 ml of molten soft agar and poured onto LB agar plates. Following incubation at 37 °C for 3−16 hours, phage plaques were observed.

2.8. Verification of Genome Assembly Accuracy and Genome Sequencing

The correct assembly of synthetic phages was confirmed in several ways. First, four pairs of phage-specific primers (

Table S2) were used for PCR validation of the resulting phage samples or yeast DNA (in cases where phage genomes could not be “rebooted”). Using these primers, it was shown that all the resulting phages were chimeric: they contained the scaffold from one phage and the tailspike proteins from another phage.

Next, a region of the genome of approximately 700 bp in size, including the region of the junction of the pt7 and pt8_tsp fragments of phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP192_tspA195, as well as the junction of the pt7+8A and pt8B fragments of phages 195_tspN195AB192 and 192_tspN192A195, was sequenced according to Sanger method. Sequencing revealed the presence of one substitution in the non-coding region of one of the clones of KP195_tspAB192 phage, all other sequences were as expected. Finally, whole genome sequencing was performed for one of the KP192ctrl phage clones using Illumina MiSeq. Three missense mutations and one silent mutation were found across 40635 bases. These mutations did not interfere with phage replication.

2.9. Phage Propagation and Purification

Phages KP192 and KP195_tspAB192 were propagated by infecting 50 mL of an exponentially growing culture of K. pneumoniae strain A (optical density OD600 = 0.4−0.7) at a multiplicity of infection (MOIinf, i.e., the ratio of phage to bacterium, calculated based on infectious titer of the phage sample) of 0.01 (one PFU of phage per 100 cells). Phages KP195_tspN195AB192 and KP195 were propagated using K. pneumoniae strains B or E, respectively (phage KP195_tspN195AB192 was unable to lyse strain A). The infected cultures were incubated with shaking at 37°C until the bacterial lysis occurred. Phages were purified from cleared lysate by polyethylene glycol-6000 (PEG-6000) precipitation, as described previously (Sambrook J, 2001; Carroll-Portillo A et al., 2021). Phage pellet was dissolved in 800 ul of SM buffer (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.05% NaN3) and stored at +4°C.

2.10. Determination of Infectious Titer of Phage Samples

Two types of phage titers were used in this study: infectious titer and pseudo-physical titer. To determine infectious titer, appropriate indicator strain (K. pneumoniae strain A, B, C or D) was grown at 37°C and 180 rpm agitation until OD600 reaches 0.5 – 0.6. The culture (0.5 ml) was mixed with 4 ml of molten soft agar and poured onto LB-agar plates. Phage samples were diluted 10-fold in LB medium ranging from 10-1 to 10-8 dilution. Aliquots (6 ul) were applied to the plates. Following overnight incubation at 37 °C, phage plaques were counted. To exclude day-to-day variability, phage samples KP192, KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192 were analyzed simultaneously. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The data was processed using Microsoft Excel 2010.

2.11. Determination of Pseudo-Physical Titer (TiterPP) of Phage Samples

In this study, the equalization (or matching) of phage samples by phage particle concentration was based on the fact that the majority of phage structural proteins has a fixed copy number. Therefore, protein electrophoresis followed by densitometry was used to compare phage concentrations. Arbitrary units called “protein concentration-linked units” (PCLU) were introduced for convenience throughout the study. Thus, one PCLU of any phage is the amount of phage that contains the same amount of major capsid protein as 1 PFU of the reference sample of KP192 phage, the infectious titer of which was measured according to locally standardized protocol. In addition, a pseudo-physical phage titer (titer

PP), measured in PCLU/ml, was introduced. To determine the pseudo-physical titer of the phage, two-fold dilutions of the test sample were analyzed by SDS-PAGE together with a reference sample containing 3 × 10

8 PFU of PEG-purified KP192 phage. The infectious titer of the reference sample was determined beforehand using

K. pneumoniae strain A (in triplicate). The same reference sample was used throughout the study. The gel (12% w/v) was stained using Coomassie G-250 (

Figure S1). Densitometric analysis of bands corresponding to the major capsid protein (MW = 37 kDa, 415 copies per virion in case of T7 phage (Kemp P et al., 2005; Guo F et al., 2014)) was performed using Image-Lab 6.0 software (Bio-Rad). The diluted sample that most closely matched the intensity of the major capsid protein band of the reference sample, was used to determine the pseudo-physical titer of the test phage sample using the following equation:

where OD

test is the integrated density of the major capsid protein band of diluted sample, OD

reference is the same parameter of reference sample, DF – dilution factor ( e.g. 8). The error rate of this method is 20−30% due to the inaccuracy of gel densitometry.

It is worth noting that in the case where strain A is infected with phage KP192, one PFU is equivalent to one PCLU by definition. For other phages, PFU may differ from PCLU due to differences in the efficiency of plating: 1 PFUphage + strain is equivalent to ( 1 PCLU × rEOPphage + strain), where rEOP is the relative efficiency of plating of the given phage using the given strain.

Method validation is described in the Supplementary methods section.

2.12. Efficiency of Plating Determination

The plaque formation efficiency (efficiency of plating, EOP) of phage KP192, determined using a locally standardized protocol on strain A, was chosen as a reference. The relative efficiency of platin (rEOP) of the test phage on any test strain was calculated using the equation:

where titer

inf is the infectious titer of the test and reference samples, and titer

PP is pseudo-physical titer for these samples. In case of infection of strain A using KP192 phage, rEOP = 1.

Since the multiplicity of infection value is based on the phage titer value, two types of MOI are related by the equation:

where MOI

inf and MOI

PP are MOI values based on infectious or pseudo-physical titers, respectively.

2.13. Bacterial Killing Assay

K. pneumoniae strain A or B was cultivated at 37°C and agitation at 180 rpm until OD600 reaches 0.5. Test phage (108 PCLU) was added to 5 ml of cells (109 CFU) at MOIPP = 0.1. Following 30 min of adsorption at 37°C, the cells were incubated at 37°C and shaking at 180 rpm. Starting from the moment of mixing, samples were taken every hour and the number of viable cells was analyzed by titration on LB agar followed by colony counting. All phages were analyzed simultaneously to minimize day-to-day variability. The experiments were performed in triplicate for each Klebsiella strain. The results were not averaged, since differences in the onset of lysis resulted in a large deviation of results.

2.14. Determination of Phage Adsorption Efficiency

Adsorption strain (

K. pneumoniae strain A or B) was cultivated at 37°C until OD

600 reaches 0.2. Indicator strain was grown similarly until OD

600 reaches 0.5. Strain A was used as indicator in case of KP192 phage, while strain B was used for KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN

195AB192 phages due to the differences in efficiency of plating. Test phages (5 × 10

6 PCLU in 10 ul aliquot) were mixed with 100 ul of adsorption strain suspension (10

7 CFU) at MOI

PP = 0.5 (according to Ando H et al., 2015) or 100 ul of LB medium (control experiment). Following incubation at 37°C for 7 min, all samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30s to settle down cells with adsorbed phages. 50 ul of supernatant was mixed with 350 ul of PBS containing 20 ul of chloroform. Following centrifugation at 12,000 g for 1min, supernatants were 10-fold diluted in LB medium. 100 ul of each dilution was mixed with 500 ul of indicator strain (exponential-growth phase, OD

600 = 0.4 – 0.6) and 3.5 ml of molten soft agar, then poured onto LB-agar plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 3−16 h, phage plaques were counted and adsorption efficiency was calculated according to the following equation:

where N

control – number of plaques on control plate, N

free – number of plaques on experimental plate formed by non-adsorbed phage particles.

The experiments were performed in triplicate for each tested adsorption strain. Mean value and SD were calculated. This method allows determination of adsorption efficiency for infectious phage particles only.

2.15. One-Step Growth Curves Determination

Test strain (

K. pneumoniae strain A or B) was cultivated at 37°C to OD

600 = 0.5. Test phage (3.5 × 10

6 PCLU in 700 ul aliquot) were mixed with 700 ul of test strain suspension (1.8 × 10

8 CFU) at MOI

PP = 1/50. Following incubation at 37°C for 5 min (based on the kinetics of adsorption and lysis determined for the phages under study), cells were centrifuged at 8,000 g for 2 min to remove free phages. The pellet was resuspended in 700 ul of LB medium, and a fraction of it was transferred to incubation flask containing 10 ml of LB medium. The fraction size depended on the efficiency of plating and was selected experimentally, based on the desired number of 30–70 plaques per plate on the “5 min” plate. To determine the number of infected cells, 100 ul of cell suspension from the incubation flask was immediately mixed with 500 ul of indicator strain and 3.5 ml of molten soft agar, and then poured onto LB-agar plate. Aliquots of the cell suspension were taken from the flask and kept on ice. Following centrifugation at 12,000 g for 1 min at 4 C, aliquots were analyzed in the same way as the aliquot used for “5 min” plate. Dilutions of samples were selected experimentally based on the desired number of 30–70 plaques per 9 cm plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 3-16 h, phage plaques were counted and burst size was calculated according to the following equation:

where N

progeny is the number of plaques on plate corresponding to temporary plateau on growth curve, and N

inf. cells is the number of plaques formed by infected cells (“5 min”-marked plate).

2.16. Protein Structure Modelling and Visualization

The 3D structures of the tspA192 and tspA195 tailspike proteins, as well as homotrimers of the N-terminal fragments of these proteins, were predicted with high fidelity using ColabFold 1.5.4 (an implementation of AlphaFold 2 hosted at

https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb). Analysis of the interface between N-terminal domains and the gatekeeper and nozzle proteins was performed using a cryo-EM model of the tail of the closely related phage Kp9 (pdb id 7Y1C) using UCSF Chimera v 1.13.1. Amino acid sequence alignment of N-terminal domains of tailspike proteins was performed using BioEdit 7.2.5.

2.17. Bioinformatic Analysis of Differences Between KP192 and KP195 Genomes

3. Results

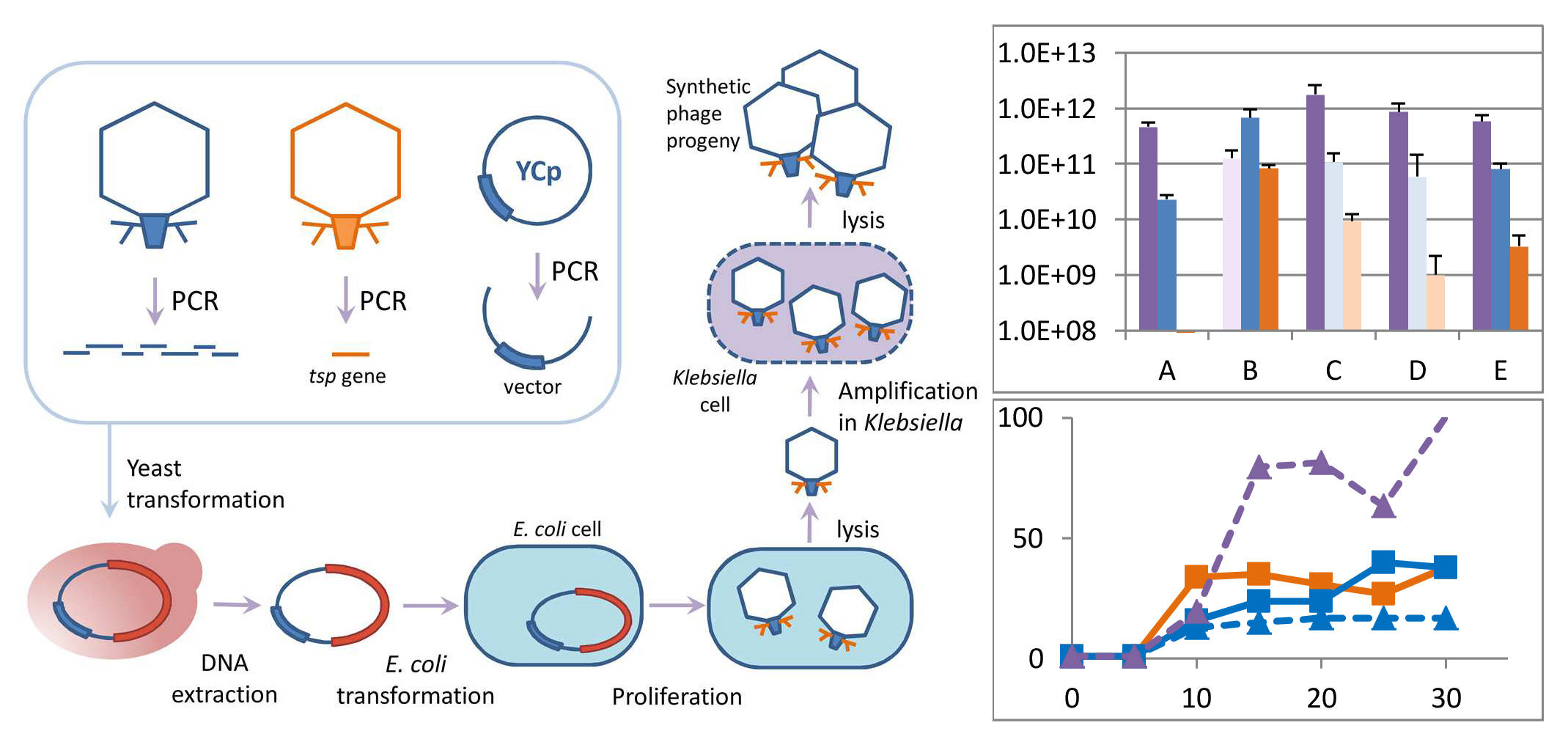

3.1. Study Design

Two

Klebsiella phages “KP32_isolate 192” and “KP32_isolate 195” (GenBank id: NC_047968 and NC_047970, respectively) from the Collection of Extremophilic Microorganisms and Type Cultures (CEMTC) of the Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine SB RAS, Novosibirsk, were used in this study. Both phages (hereinafter KP192 and KP195) have podovirus morphotype and are members of the

Przondovirus genus. The genomes of KP192 and KP195 phages are similar, but not identical: intergenomic similarity is 83% for complete genomes and 90% for genomes excluding the tail spike protein genes. The KP192 genome contains two genes encoding tail spike proteins designated as

tspA192 and

tspB192. The protein encoded by the

tspA192 gene forms homotrimers and contains the T7gp17-like N-terminal adapter domain that promotes the insertion of the tail spike into the tail of the phage. The tail spikes directly attached to the phage tail are named “tail spikes A” in this study. The protein encoded by the

tspB192 gene also forms homotrimeric tail spikes, and the N-terminal part of this protein provides attachment to the T4gp10-like branching domain of the tail spikes A (Latka A et al., 2019}. This type of tail spikes is referred to as “tail spikes B” in this article. KP195 contain only one gene

tspA195 encoding tail spike A protein tspA195. Capsular specificities of the proteins tspA192, tspB192 and tspA195 are as follows: K37, K2 and K64, respectively. Accordingly, KP192 infects

K. pneumoniae strains with capsule types (K-types) K37 and K2, whereas KP195 infects strains with K64 capsule type (

Figure 1). The KP192 phage does not infect strains sensitive to the KP195 phage, and vice versa.

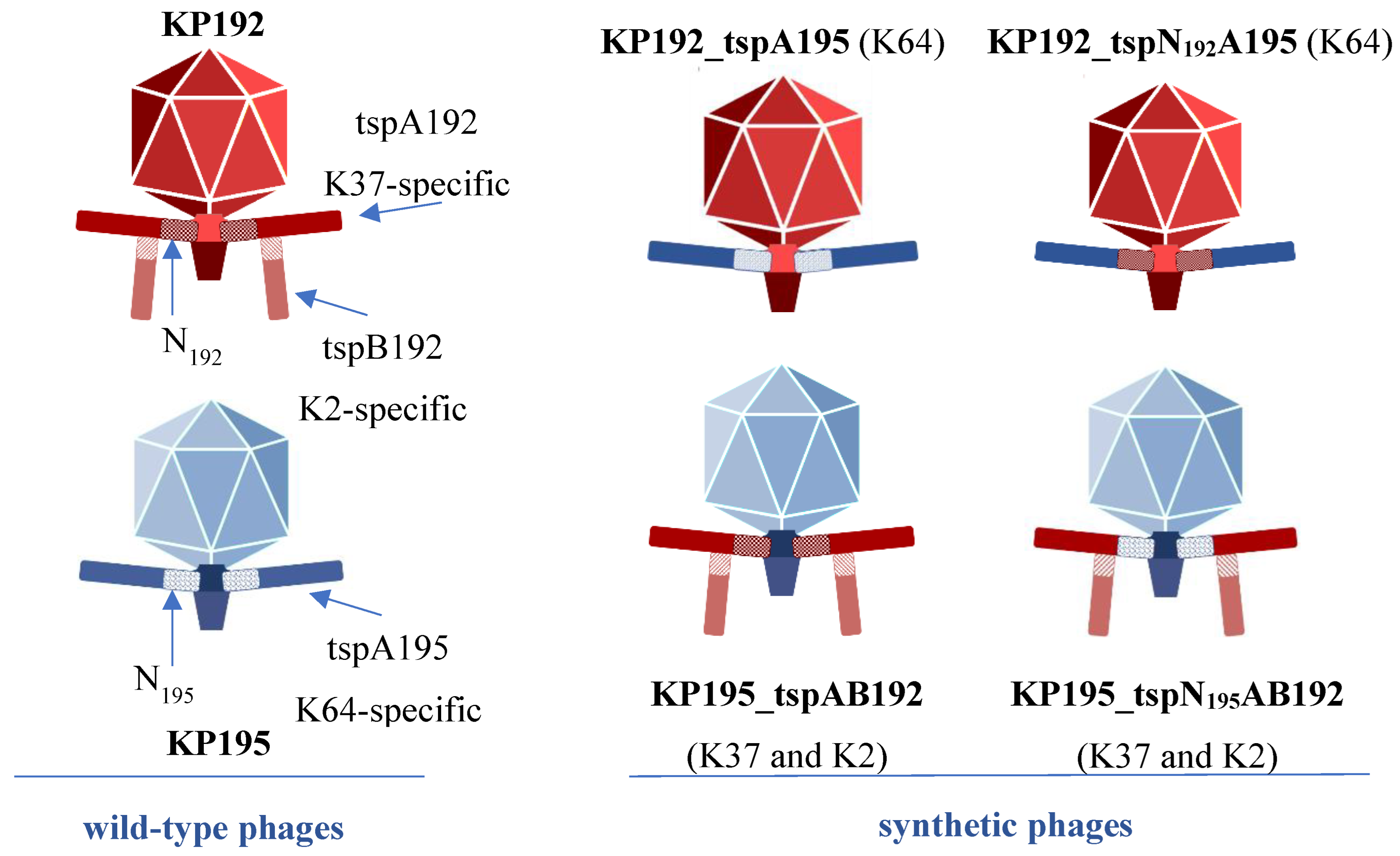

In order to study the impact of phage scaffold selection on the properties of synthetic phages, KP195_tspAB192 and KP192_tspA195 phage genomes with swapped tsp genes were designed (

Figure 1). During the morphogenesis of the tails of these chimeric phages, it is necessary that the N-terminal domains of the tspA192 and tspA195 proteins (hereinafter N

192 and N

195, respectively) can freely integrate into the tail of the “non-native” phage. At the same time, the sequences of these domains differ significantly (

Figure 2A) with an amino acid identity of ~69%, which may cause a mismatch between them and the adjacent tail proteins (gatekeeper protein and nozzle protein). This, in turn, may reduce the efficiency of tail assembly or cause or degradation of assembled tails within mature phage particles. To study the influence of the N-terminal domain sequence of the tail spike protein A on phage properties, synthetic phages KP195_tspN

195AB192 and KP192_tspNA195 were also designed. In phage KP195chAB192, the

tspA195 gene was replaced by the gene encoding the chimeric protein tspN

195A192, containing 149 N-terminal residues from tspA195 and the rest from tspA192, along with

tspB192 gene. Similarly, the synthetic phage KP192_tspN

192A195 was designed. In its genome, a pair of

tspA192 and

tspB192 genes was replaced by the gene of the chimeric protein tspN

192A195, which combines 149 N-terminal residues from tspA192 and the rest from tspA195 (

Figure 1).

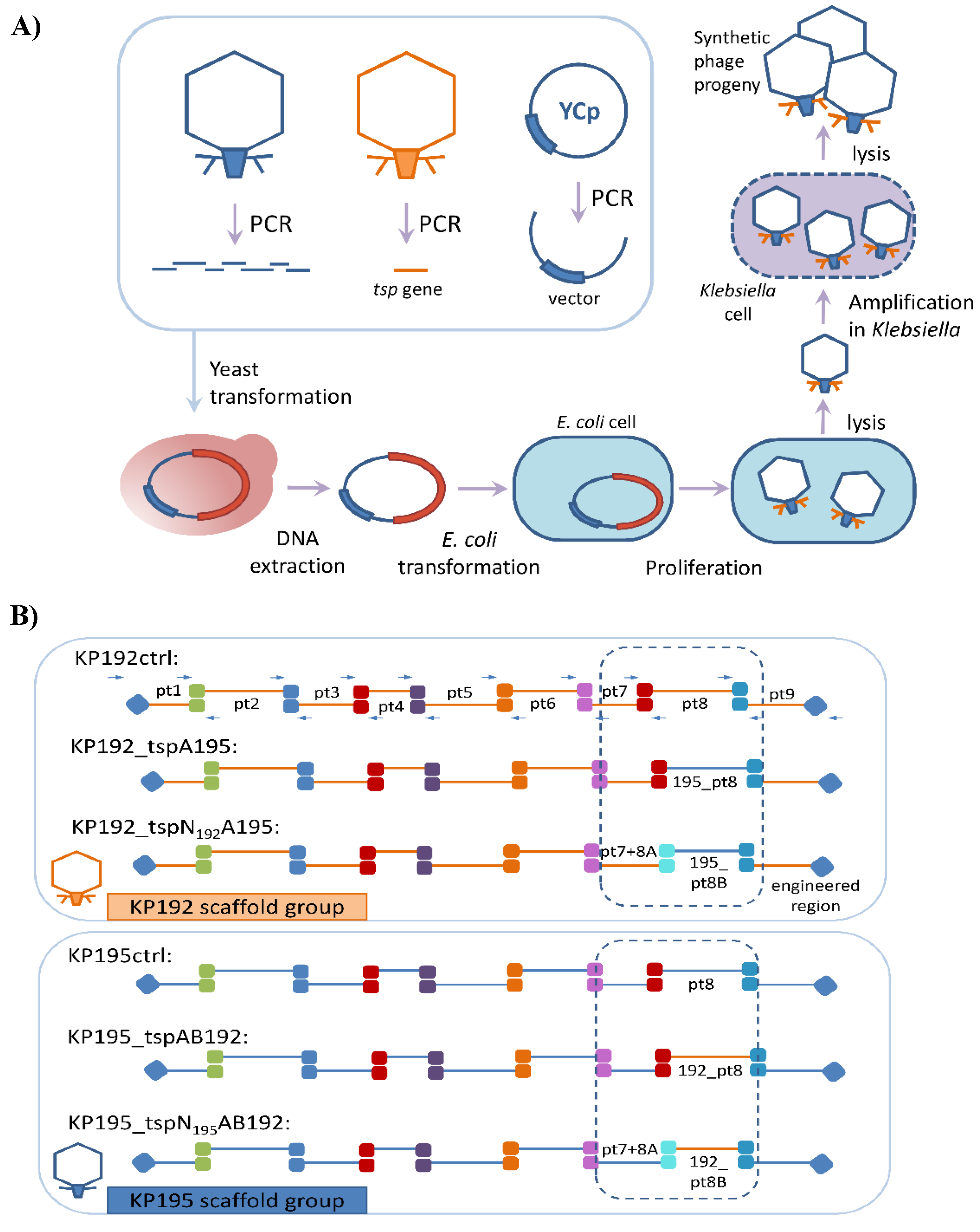

DNA fragments required for genome assembly were produced using PCR. The genomes of all synthetic phages were assembled by transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning in

S. cerevisiae (Larionov V et al., 1996; Gibson DG et al., 2008; Jaschke PR et al., 2012) (

Figure 3). The constructed genomes were used to obtain infectious phage particles and then, the resulting synthetic phages were characterized.

3.2. Assembly of Synthetic Phage Genomes

The genomes of synthetic phages were assembled from overlapping PCR fragments in yeast using yeast centromeric plasmid pRSII415, similar to the previously described method (Ando H et al., 2015; Latka A et al., 2021; Pires D et al., 2021). For convenient assembly, all phage genomes were divided into nine fragments of 3−6 kbp in relatively conservative areas. A detailed diagram of the phage assembly is shown in

Figure 3B. The genomes of the parental phages KP192 and KP195 were assembled similarly to confirm that the level of mutations during assembly does not prevent the production of viable phages. These control phages were designated KP192ctrl and KP195ctrl.

Following yeast transformation, individual colonies were screened using PCR. Yeast centromeric plasmid DNA containing the phage genome was isolated from the biomass of positive clones.

3.3. “Rebooting” of Klebsiella Phage Genomes

Since K. pneumoniae strains often demonstrate low electrocompetence (Fournet-Fayard S et al., 1995), virions of synthetic phages were obtained by transformation of E. coli as an intermediate host (Ando H et al., 2015). Strains of the Klebsiella and Escherichia genera belong to the same family Enterobacteriaceae and their genomes contain similar regulatory regions. Therefore, Klebsiella RNA-polymerase promoters are recognized in E. coli, which ensures the expression of the Klebsiella phage genes, synthesis of phage proteins and assembly of phage particles. However, these phage particles cannot infect E. coli cells for subsequent reproduction. So, the resulting extract of E. coli cells containing phage particles was mixed with cells of the corresponding K. pneumoniae strain and the formation of phage plaques on bacterial lawn was observed. Klebsiella pneumoniae CEMTC 2274 (host strain for KP192, K-type K37, hereinafter “strain 2274” or “strain A”) was used in case of phages KP195_tspAB192, KP195_tspN195AB192, or KP192ctrl. K. pneumoniae CEMTC 2337 (host strain for KP195, K-type K64, hereinafter “strain 2337” or “strain E”) was used in case of phages KP192_tspA195, KP192_tspN192A195 or KP195ctrl.

“Rebooting” of the genomes of control synthetic phages KP192ctrl and KP195ctrl resulted in the formation of multiple plaques, while the morphology of plaques formed by control and wild-type phages was the same. This indicates the high efficiency of assembling and “rebooting” the genomes of synthetic phages. At the same time, “rebooting” the genomes of synthetic phages with swapped tailspike proteins led to the formation of a significantly smaller number of plaques (

Figure 4). Surprisingly, the KP195_tspN

195AB192 phage genome could only be rebooted using strain CEMTC 2291 (K-type K2, hereinafter “strain 2291” or “strain B”), but not strain A (propagation host for KP192, K-type K37). The genome of phage KP192_tspN

192A195 could not be rebooted at all. Phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN

195AB192 were amplified in liquid culture using strains A and B, respectively. However, phage KP192_tspA195 did not lyse liquid culture of strain E and for this reason was not used in further experiments.

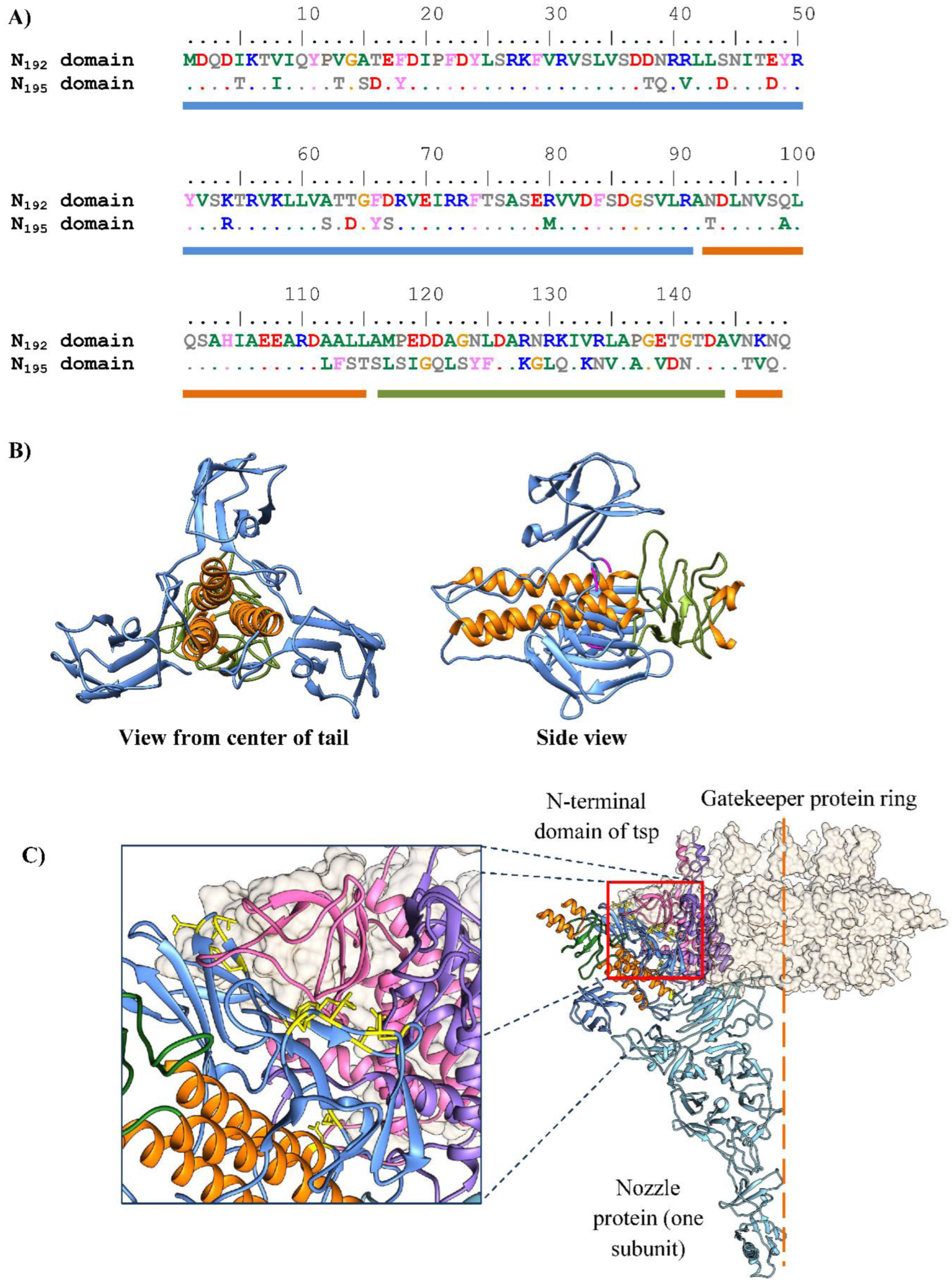

3.4. Infectious Properties of Phages KP192, KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192

Next, some properties of the synthetic phages, such as efficiency of plating (EOP), efficiency of adsorption on cells and efficiency of lysis, were investigated. The rate of adsorption of phages on cells, and hence the fraction of adsorbed phages, depend on the concentration of phage particles (physical titer) (Abedon ST, 2023). Therefore, in order to correctly compare different phage samples, it is necessary to take the same number of infectious phage particles into the experiment. In this study, the equalization (or matching) of phage samples by phage particle concentration was based on the fact that the majority of phage structural proteins has a fixed copy number. Therefore, protein electrophoresis followed by densitometry was used to compare phage concentrations. Arbitrary units called “protein concentration-linked units” (PCLU) were introduced for convenience throughout the study (see Methods). In addition, a pseudo-physical phage titer (titerPP), measured in PCLU/ml, was introduced. If samples of different phages have the same titerPP, then their physical titer is also the same, even if it is unknown. This is the basis for standardization of experimental conditions in this study.

First, end-point productivity of phages was compared by determining titer

PP for PEG-precipitated samples of KP192, KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN

195AB192 phages. The titer values were close: 4.6 × 10

11, 1.5 × 10

11 and 2.3 × 10

11 PCLU/ml, respectively. The efficiency of plating of the phages was studied on strains A and B (K37 and K2 capsular types, respectively), as well as two KP192 phage-sensitive K2 strains of

K. pneumoniae CEMTC 2573 and 3533 (hereinafter “strain C” and “strain D”, respectively). For this purpose, infectious titers of phage samples having the same pseudo-physical titer were determined, and their plating efficiency relative to that of phage KP192 on strain A (relative efficiency of plating, rEOP) was calculated (

Figure 5A,B). In addition, the size and morphology of plaques were examined (

Figure 5C).

Wild-type phage KP192 was found to efficiently form plaques (rEOP ≥ 1) using strains A, C, and D, with plaques of medium size formed. However, phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192 formed small or microscopic plaques on the same strains, and the efficiency of plating was 1−5 orders of magnitude lower. In contrast, strain B was poorly suited for the propagation of phage KP192, which formed numerous microscopic plaques without a halo. At the same time, it was well infected by synthetic phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192, forming plaques with a large halo. Therefore, strain B and the group of strains A, C, D differed greatly in susceptibility to the studied phages.

It is worth noting that in the case of strain A, the plaque formation efficiency of phage KP195_tspN195AB192 was 4 orders of magnitude lower than that of phage KP195_tspAB192. At the same time, these phages are identical except for the N-terminal domain of the tailspike A. The same EOP difference was shown for all the studied clones of these phages, which indicates a reliable influence of this domain on the reproduction efficiency of these phages.

Next, the ability of phages to inhibit the growth of

Klebsiella in liquid culture was investigated (

Figure 5D). Only strains A and B were investigated because these strains cover the range of phage KP192 specificity (K-types K37 and K2), and the plaque formation efficiency of the studied phages diffed most on these strains. As before, the same physical amount of phages was taken into assay. In the case of strain A it was found that the efficiency of killing of planktonic bacteria was in good agreement with the EOP and plaque morphology, as expected. In the case of phage KP192 infecting strain B − similarly. Surprisingly, phage KP195_tspN

195AB192 significantly outperformed phage KP195_tspAB192 in lysis efficiency of liquid culture of strain B, despite a tenfold lower plaque formation efficiency on the lawn formed by this strain.

To explain the observed results, the adsorption efficiency of the phages on the cells of strains A and B was determined. According to the results (

Figure 5E), the infective virions of phages KP192 and KP195_tspAB192 were adsorbed with the same efficiency on both strain A and strain B. Therefore, the difference in the reproduction efficiency of these phages on these strains was not caused by lowered adsorption efficiency due to defects in the folding of tailspike proteins or during tail assembly process. Most likely, it was caused by differences in other stages of the phage life cycle.

Infectious virions of phage KP195_tspN195AB192 were adsorbed on strain B as efficiently as other phages, but they were adsorbed less efficiently on strain A (70% adsorption versus 90% adsorption for other phages). Moreover, phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192 differed from each other only in the N-terminal domain of tailspike protein A. Hence, the N-terminal domain of protein tspA192 (K37 capsular specificity) either: (i) increases the affinity of this protein to the K37 capsular polysaccharide, or (ii) increases the affinity of this protein to some other surface component that was present on strain A but absent on strain B.

Finally, one step growth curves were determined for the studied phages (

Figure 5F). It was shown that the latent period for all phages was about 10 min. Therefore, the observed differences in the reproduction efficiency of the phages were not due to a lysis delay. However, the number of infective virions in phage progeny (burst size) varied substantially from 17 to 80 phages per cell and correlated with the lytic properties of the phages (

Figure 5D).

Based on the obtained results, several conclusions can be made. First, some unidentified features of the KP195 scaffold resulted in a decrease in the reproduction efficiency of the synthetic phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192 on strains A, C and D compared to phage KP192, while on strain B these phages reproduced with high efficiency. At the same time, some features of the KP192 scaffold resulted in a decrease in the reproduction efficiency of phage KP192 on strain B. Second, differences in the N-terminal domain of tailspikes A significantly affected the reproduction efficiency of the studied phages. In this case, the N192 domain was more favorable in the case of strain A, since it at least increased the efficiency of phage adsorption on cells. In contrast, in the case of strain B, the N195 domain was more favorable, although in this case the increase in phage replication efficiency was not associated with the phage adsorption. Therefore, the N-terminal domain of tailspikes A of Przondovirus phages can influence phage replication efficiency using different mechanisms.

3.5. Analysis of Differences Between the Genomes of Phages KP192 and KP195 That Potentially Affect the Efficiency of Reproduction

Phages KP192 and KP195_tspAB192 differ from each other in the efficiency of reproduction on several strains of

K. pneumoniae. At the same time, they contain the same genes

tspA192 and

tspB192, but a different set of other genes. To explain the observed differences in the properties of the phages, the genomes of phages KP192 and KP195, as well as the amino acid sequences of orthologous proteins, were compared (

Figure 6,

Table 1).

Conserved proteins (portal protein, large and small subunits of terminase) differ insignificantly, within 3−7%. At the same time, the differences between some proteins are approximately 20%, which can be significant. For example, protein kinases of phages KP192 and KP195 differ by 19%, and the differences are localized within two regions of these proteins. The orthologous enzyme of T7 phage deactivates some enzymes, including the host RNA polymerase, and at the same time activates RNase III. So, it can be assumed that protein kinases of KP192 and KP195 phages perform similar role. In this case, the differences in the amino acid sequence of these proteins may be associated with differences in the target proteins. Accordingly, in one group of Klebsiella strains, such an inhibitor/activator can be effective, while in another group of strains, the target proteins may be absent or have a different sequence. Ultimately, this may lead to an inefficient switch of the host cell’s enzymatic machinery to the synthesis of phage mRNA.

Similarly, the dGTPase inhibitors of phages KP192 and KP195 differ by 34%. However, the dGTPase gene is highly conserved among different strains of K. pneumoniae. So it is unlikely that the difference in reproduction efficiency between phages KP192 and KP195_tspAB192 is caused by differences in this gene. The fusion proteins of phages KP192 and KP195 differ by 23%. Although genes for similar proteins have been found in the genomes of many phages, it has not been possible to determine the role of this protein from published studies. A blast search showed that the sequence of the N-terminal region of this protein varies greatly even among closely related Przondovirus phages. Finally, some genes are completely absent in the KP192 genome. To conclude, this analysis did not reveal the key component responsible for the difference observed in reproduction efficiency between phages KP192 and KP195_tspAB192. It is likely that the observed differences may be associated with bacterial anti-phage defense systems.

4. Discussion

In order to successfully engineer phages against a target bacterium, many factors should be considered. Selection of suitable phage receptor-binding proteins is necessary, since these proteins ensure the binding of the phage to the bacterial receptor and the degradation of the protective layer of the bacterium (reviewed in Lenneman BR et al., 2021; Dunne M et al., 2021). However, replacement of receptor-binding proteins is sometimes insufficient to produce viable phages (Ando H et al., 2015; Latka A et al., 2021). In this study, the following questions were addressed: (a) criteria for selection of the genomic scaffold for the engineering of a synthetic phage; (b) the additional genes (other than tailspike/tail fiber genes) that can also be crucial when designing synthetic phages; (c) the importance of the appropriate sequence of the N-terminal anchoring domain of the tail spikes A.

In this study, two Klebsiella phages from the Przondovirus genus were chosen as model phages. Importantly, these phages, KP192 and KP195, were specific to K. pneumoniae strains A (CEMTC 2274) and E (CEMTC 2337), respectively, belonging to different capsular K-types. The exchange of the tsp genes between KP192 and KP195 indicated that the resulting phages can propagate only in strains that are recognized by the phage tail spike proteins. So, the presence of appropriate tsp protein is necessary for successful reproduction of the phage in the Klebsiella strain. This result is consistent with previous studies (Ando H et al., 2015; Latka A et al., 2021).

However, the reproduction efficiency of synthetic phages with the same tsp genes but a different scaffold differed significantly. This was reflected in the efficiency of plating and bacteria lysis efficiency. Thus, the parental phages KP192 and KP195 and their synthetic analogs KP192ctrl and KP195ctrl propagated more efficiently on the majority of tested strains of suitable K-types than synthetic phages with swapped tsp genes. The only exception was strain B (CEMTC 2291, K2-type), in which synthetic phages KP195_tspAB192 and KP195_tspN195AB192 reproduced more efficiently than the parental phage KP192. This indicates the important role of some genes located in the genomic scaffold. Similar result was described previously for the synthetic phage RCIP0035∆rbpIII::rbp0046 (Wang C et al., 2024). Therefore, the selection of scaffold for a synthetic phage is important and the use of a proper one can increase lytic activity of the phage.

In addition, the influence of the N-terminal domain of tail spikes A on the properties of synthetic phages was investigated. Previously, N-terminal domains of some tsp proteins have been combined with the “enzymatic” part of another tsp proteins for some Klebsiella phages. However, no N-terminal sequence dependent changes in properties of recombinant proteins or synthetic phages have been reported (Latka A et al., 2021). In our study, differences in the sequence of the first 149 amino acid residues of tailspikes A significantly affected the properties of synthetic phages. The advantage of one or another variant of the N-terminal domain was strain-specific: in the case of strain A, the N192 domain provided higher adsorption efficiency of the KP195_tspAB192 phage, thereby accelerating its replication compared to the KP195_tspN195AB192 phage. However, the 1.5-fold difference in the adsorption efficiency of these phages on strain A does not agree well with the observed 103 – 104-fold difference in plating efficiency. Therefore, we propose that the N192 domain somehow (directly or indirectly) enhances the efficiency of K37-type capsular polysaccharide hydrolysis, while the N195 domain is unable to do so.

On the contrary, domain N192 provided lower burst size of phage in case of strain B, which resulted in more moderate efficiency of Klebsiella planktonic culture lysis by phage KP195_tspAB192, without decreasing plaque formation efficiency. Molecular mechanism of this phenomenon is not entirely clear. Probably, some mismatches between N192 domain and tail proteins of phage KP195 resulted in decreased efficiency and rate of assembly of phage tails. Consequently, at the moment of lysis there were fewer mature virions in the cell, which affected observed burst size. Thus, it was shown that N-terminal domain of tailspike A proteins of przondoviruses can influence efficiency of phage reproduction using different mechanisms.

Since a decrease in the efficiency of reproduction can significantly affect the therapeutic properties of the phage, it is necessary to select a recipient phage with a proper genomic scaffold that would ensure effective propagation of the synthetic phage in target strains. The sequence of tsp proteins per se may not be sufficient for a design of phages with predictable properties, and other factors affecting the efficiency of phage reproduction should be considered. The KP192 and KP195 phages substantially differ in a number of genes, including genes that encode the nozzle protein, presumably involved in binding to the secondary receptor, and the gatekeeper protein, which can exhibit depolymerase activity in some Klebsiella phages (Pyra A et al., 2017; Brzozowska E et al., 2017). However, differences in the efficiency of reproduction of the parental phages KP192 and KP195 and synthetic phages with swapped tsp proteins may also be associated with a set of anti-phage defense systems present in the used K. pneumoniae strains. It is not yet clear which factors are important for the effective reproduction of a phage in a certain target bacterium. Further accumulation of experimental data and its comprehensive analysis are required to identify these factors. This, in turn, would help to transform the design of artificial bacteriophages from being the mixture of art and science into a technology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.B., N.V.T. and V.V.M; investigation, I.K.B., E.E.M., O.M.K., A.V.M and T.A.U.; resources, N.V.T. and I.K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.B. and N.V.T.; writing—review and editing, I.K.B., N.V.T. and V.V.M.; visualization, I.K.B.; supervision, N.V.T., project administration, I.K.B.; funding acquisition, I.K.B.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-24-00553.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Valeriya A. Fedorets for assistance in DNA sequencing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abedon ST. Bacteriophage Adsorption: Likelihood of Virion Encounter with Bacteria and Other Factors Affecting Rates. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Apr 7;12(4):723. [CrossRef]

- Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R, Green T, Pritzel A, Ronneberger O, Willmore L, Ballard AJ, Bambrick J, Bodenstein SW, Evans DA, Hung CC, O’Neill M, Reiman D, Tunyasuvunakool K, Wu Z, Žemgulytė A, Arvaniti E, Beattie C, Bertolli O, Bridgland A, Cherepanov A, Congreve M, Cowen-Rivers AI, Cowie A, Figurnov M, Fuchs FB, Gladman H, Jain R, Khan YA, Low CMR, Perlin K, Potapenko A, Savy P, Singh S, Stecula A, Thillaisundaram A, Tong C, Yakneen S, Zhong ED, Zielinski M, Žídek A, Bapst V, Kohli P, Jaderberg M, Hassabis D, Jumper JM. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 2024 Jun;630(8016):493-500. [CrossRef]

- Ando H, Lemire S, Pires DP, Lu TK. Engineering Modular Viral Scaffolds for Targeted Bacterial Population Editing. Cell Syst. 2015 Sep 23;1(3):187-196. [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska E, Pyra A, Pawlik K, Janik M, Górska S, Urbańska N, Drulis-Kawa Z, Gamian A. Hydrolytic activity determination of Tail Tubular Protein A of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophages towards saccharide substrates. Sci Rep. 2017 Dec 22;7(1):18048. [CrossRef]

- Carroll-Portillo A, Coffman CN, Varga MG, Alcock J, Singh SB, Lin HC. Standard Bacteriophage Purification Procedures Cause Loss in Numbers and Activity. Viruses. 2021 Feb 20;13(2):328. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Xiao H, Wang L, Wang X, Tan Z, Han Z, Li X, Yang F, Liu Z, Song J, Liu H, Cheng L. Structural changes in bacteriophage T7 upon receptor-induced genome ejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Sep 14;118(37):e2102003118. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo A, Fàbrega-Ferrer M, Machón C, Conesa JJ, Fernández FJ, Pérez-Luque R, Pérez-Ruiz M, Pous J, Vega MC, Carrascosa JL, Coll M. Structures of T7 bacteriophage portal and tail suggest a viral DNA retention and ejection mechanism. Nat Commun. 2019 Aug 20;10(1):3746. [CrossRef]

- Cui L, Watanabe S, Miyanaga K, Kiga K, Sasahara T, Aiba Y, Tan XE, Veeranarayanan S, Thitiananpakorn K, Nguyen HM, Wannigama DL. A Comprehensive Review on Phage Therapy and Phage-Based Drug Development. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024 Sep 11;13(9):870. [CrossRef]

- Dunne M, Prokhorov NS, Loessner MJ, Leiman PG. Reprogramming bacteriophage host range: design principles and strategies for engineering receptor binding proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021 Apr;68:272-281. [CrossRef]

- Dunne M, Prokhorov NS, Loessner MJ, Leiman PG. Reprogramming bacteriophage host range: design principles and strategies for engineering receptor binding proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021 Apr;68:272-281. [CrossRef]

- Fournet-Fayard S, Joly B, Forestier C. Transformation of wild type Klebsiella pneumoniae with plasmid DNA by electroporation.Journal of Microbiological Methods 1995 November; 24(1):49-54. [CrossRef]

- Gibson DG, Benders GA, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Denisova EA, Baden-Tillson H, Zaveri J, Stockwell TB, Brownley A, Thomas DW, Algire MA, Merryman C, Young L, Noskov VN, Glass JI, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO. Complete chemical synthesis, assembly, and cloning of a Mycoplasma genitalium genome. Science. 2008 Feb 29;319(5867):1215-20. [CrossRef]

- Gietz D, St Jean A, Woods RA, Schiestl RH. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Mar 25;20(6):1425. [CrossRef]

- Gietz RD. Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1163:33-44. [CrossRef]

- Guo F, Liu Z, Fang PA, Zhang Q, Wright ET, Wu W, Zhang C, Vago F, Ren Y, Jakana J, Chiu W, Serwer P, Jiang W. Capsid expansion mechanism of bacteriophage T7 revealed by multistate atomic models derived from cryo-EM reconstructions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Oct 28;111(43):E4606-14. [CrossRef]

- Jaschke PR, Lieberman EK, Rodriguez J, Sierra A, Endy D. A fully decompressed synthetic bacteriophage øX174 genome assembled and archived in yeast. Virology. 2012 Dec 20;434(2):278-84. [CrossRef]

- Kemp P, Garcia LR, Molineux IJ. Changes in bacteriophage T7 virion structure at the initiation of infection. Virology. 2005 Sep 30;340(2):307-17. [CrossRef]

- Krishna R, Wang J, Ahern W, Sturmfels P, Venkatesh P, Kalvet I, Lee GR, Morey-Burrows FS, Anishchenko I, Humphreys IR, McHugh R, Vafeados D, Li X, Sutherland GA, Hitchcock A, Hunter CN, Kang A, Brackenbrough E, Bera AK, Baek M, DiMaio F, Baker D. Generalized biomolecular modeling and design with RoseTTAFold All-Atom. Science. 2024 Apr 19;384(6693):eadl2528. [CrossRef]

- Larionov V, Kouprina N, Graves J, Resnick MA. Highly selective isolation of human DNAs from rodent-human hybrid cells as circular yeast artificial chromosomes by transformation-associated recombination cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93(24):13925-30. [CrossRef]

- Latka A, Leiman PG, Drulis-Kawa Z, Briers Y. Modeling the Architecture of Depolymerase-Containing Receptor Binding Proteins in Klebsiella Phages. Front Microbiol. 2019 Nov 15;10:2649. [CrossRef]

- Latka A, Lemire S, Grimon D, Dams D, Maciejewska B, Lu T, Drulis-Kawa Z, Briers Y. Engineering the Modular Receptor-Binding Proteins of Klebsiella Phages Switches Their Capsule Serotype Specificity. mBio. 2021 May 4;12(3):e00455-21. [CrossRef]

- Leiman PG, Chipman PR, Kostyuchenko VA, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rossmann MG. Three-dimensional rearrangement of proteins in the tail of bacteriophage T4 on infection of its host. Cell. 2004 Aug 20;118(4):419-29. [CrossRef]

- Lenneman BR, Fernbach J, Loessner MJ, Lu TK, Kilcher S. Enhancing phage therapy through synthetic biology and genome engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021 Apr;68:151-159. [CrossRef]

- Marinelli LJ, Piuri M, Swigonová Z, Balachandran A, Oldfield LM, van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. BRED: a simple and powerful tool for constructing mutant and recombinant bacteriophage genomes. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3957. [CrossRef]

- Meile S, Du J, Staubli S, Grossmann S, Koliwer-Brandl H, Piffaretti P, Leitner L, Matter CI, Baggenstos J, Hunold L, Milek S, Guebeli C, Kozomara-Hocke M, Neumeier V, Botteon A, Klumpp J, Marschall J, McCallin S, Zbinden R, Kessler TM, Loessner MJ, Dunne M, Kilcher S. Engineered reporter phages for detection of Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, and Klebsiella in urine. Nat Commun. 2023 Jul 20;14(1):4336. [CrossRef]

- Moraru C, Varsani A, Kropinski AM. VIRIDIC-A Novel Tool to Calculate the Intergenomic Similarities of Prokaryote-Infecting Viruses. Viruses. 2020 Nov 6;12(11):1268. [CrossRef]

- Morozova V, Babkin I, Kozlova Y, Baykov I, Bokovaya O, Tikunov A, Ushakova T, Bardasheva A, Ryabchikova E, Zelentsova E, Tikunova N. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Klebsiella pneumoniae N4-like Bacteriophage KP8. Viruses. 2019 Dec 2;11(12):1115. [CrossRef]

- Patro LPP, Sudhakar KU, Rathinavelan T. K-PAM: a unified platform to distinguish Klebsiella species K- and O-antigen types, model antigen structures and identify hypervirulent strains. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 7;10(1):16732. [CrossRef]

- Pyra A, Brzozowska E, Pawlik K, Gamian A, Dauter M, Dauter Z. Tail tubular protein A: a dual-function tail protein of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophage KP32. Sci Rep. 2017 May 22;7(1):2223. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 187–303.

- Shen J, Zhou J, Chen GQ, Xiu ZL. Efficient Genome Engineering of a Virulent Klebsiella Bacteriophage Using CRISPR-Cas9. J Virol. 2018 Aug 16;92(17):e00534-18. [CrossRef]

- Strathdee SA, Hatfull GF, Mutalik VK, Schooley RT. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell. 2023 Jan 5;186(1):17-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Wang S, Jing S, Zeng Y, Yang L, Mu Y, Ding Z, Song Y, Sun Y, Zhang G, Wei D, Li M, Ma Y, Zhou H, Wu L, Feng J. Data-Driven Engineering of Phages with Tunable Capsule Tropism for Klebsiella pneumoniae. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Sep;11(33):e2309972. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).