1. Introduction

Maxillary sinus pathosis is a frequently described imaging finding, even in asymptomatic individuals [

1]. Mucosal thickening is the most common alteration [

2,

3,

4,

5], with a prevalence ranging from 23.7% [

6] in young patients to up to 74.3% in dentate elders [

7]. Although definitions may vary among authors, it is accepted that a normal, healthy sinus presents no mucosal thickening, or only mild thickening (<2mm) with an uniform and flat characteristic [

8] and that mucosal thickening > 6mm indicates mucosal pathology [

9].

Rhinosinusitis is the main cause of mucosal thickening in symptomatic individuals [

1,

10]. However, the cause of mucosal thickening among asymptomatic patients is still unclear [

1], being allergic problems the possible culprits [

11]. Since both rhinosinusitis and allergic conditions usually present as bilateral alterations, Otolaryngologists recognize that whenever unilateral mucosal thickening or sinus opacification is found, or when a case of chronic rhinosinusitis does not respond to antibiotics, patients must be referred to a Dentist and a dental cause must be sought [

12,

13].

In fact, Odontogenic sinusitis (OS) is a long-time known condition, but frequently underdiagnosed and still lacking a detailed and broadly accepted definition [

14]. Although recently published papers have thoroughly reviewed this topic [

15,

16] and retrospective studies estimated that more than 70% of the cases of unilateral maxillary sinusitis have odontogenic etiology [

17,

18], OS has been briefly described in the current guidelines for rhinosinusisits, such as the EPOS (European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps) [

19].

Regardless of the lack of consensus, based on the current knowledge, OS can be defined as: “predominantly unilateral sinus opacification and sinus symptoms related to a history of dental disease or dental treatment on the upper jaw (at the same side) in temporal relation to the symptoms onset and CT findings” [

20].

The biological rationale supporting the possible etiological role of odontogenic infections in the development of MT (mucosal thickening) and OS is based on the well described anatomical proximity of the apexes of maxillary premolars and molars to the maxillary sinus floor [

10,

21]. Often, the roots of maxillary teeth may disrupt the contours of the sinus floor [

10] leaving only the mucoperiosteum separating the apexes from the sinus [

21]. Such close relation allows the inflammatory exudate from periapical or periodontal infection to erode through the bone and drain into the sinus, causing OS [

21] or, in milder cases, let the bacterial/inflammatory challenges stimulate a response from the sinus membrane, leading to MT [

22].

Three-dimensional imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT), are the most accurate imaging exams to assess the spatial relationship between teeth and the maxillary sinus, detect the presence of sinus alterations and their possible causes, and allow the Dentist to prevent iatrogenic events leading to oroantral communication or the impingement of dental materials or roots within the sinus [

1,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, an European Society of Endodontology (ESE) joint position statement from 2019 pointed that CBCT must not be used routinely for endodontic diagnosis or screening purposes [

29], and thus, Specialists and GPs must request CT and/or CBCT only in specific clinical situations, such as when OS is suspected [

29].

Anatomically, first and second molars are the teeth most closely related to the maxillary sinus floor, [

23,

25,

30], being the palatal root of the first molar more prone to be related to MT and OS since it penetrates the sinus in 34.2% of the cases [

30].

Even though the concept of OS is established and well accepted by both Medical and Dental literature (5,10,14,21,31,32), there is still some controversy among studies regarding the main cause of the maxillary diseases of dental origin. Severe periodontal bone loss [

1,

11,

31,

32] and chronic apical periodontitis [

3,

4,

10,

23,

32,

33] are the dental conditions most frequently associated to maxillary sinus pathosis. However, some of these studies failed to find such association between endodontic lesions and sinusal pathosis [

1,

31].

Several other conditions have been cited as being the leading cause of MT and/or OS, such as: periapical abscess [

32]; peri-implantitis [

34]; oro-antral fistula [

35]; dento-alveolar surgery [

18,

36]; overextension of endodontic material [

34]; and dental implant related complications [

36].

Identifying the dental causes of MT and OS is extremely important because such conditions do not respond to the conventional therapy used to treat rhinosinusitis [

10], frequently leading to recalcitrant disease [

14] and unsuccessful or unnecessary sinus surgery [

23,

38]. Besides that, maxillary sinus infections can evolve into potentially serious conditions, such as, orbital and intracranial abscess [

39,

40,

41].

The proper diagnosis and treatment of OS frequently requires the collaboration between the Otolaryngologist and the Dentist [

14,

17]. The dental cause should be removed previously [

34] or concomitant with endoscopic sinus surgery [

14], and in some cases dental treatment alone is enough to resolve OS [

16,

38].

Despite the recognition of MT and OS as frequently found conditions, affecting up to 90% of the patients with periapical and/or periodontal bone loss, and corresponding to about 40% of the cases of unilateral sinus disease [

42], there are some controversies, yet to be cleared, regarding the role of chronic apical periodontitis on the etiology of MT and OS.

Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between chronic apical periodontitis (CAP), MT and maxillary sinus opacification, using CBCT, in a population of asymptomatic individuals referred for dental treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

Study sample: The Study was approved by the Research ethics committee of the Health Sciences Center of Estácio de Sá University (protocol number 50594215.8.0000.5284). A total of 130 posterior maxilla CBCTs, obtained between August 2014 and July 2015, from patients referred to a private radiology clinic (ODT Digital diagnostics, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), were randomly selected and screened by a previously trained specialist in both Endodontics and Radiology for the presence of images suggestive of chronic apical periodontitis (primary or secondary) in at least 1 posterior teeth (premolars and/or molars). For screening purposes, apical periodontitis was defined based on the criteria proposed by Bornstein et al. (2012) [

43] that defines CAP as a hypodense image, twice the width of the periodontal ligament space, closely associated to the apex. All images were acquired with PreXion Elite 3D (PreXion, Inc, San Mateo, CA, USA) using a field of view of 8x8cm and operating at 4.0mA, 90kV, 0.1-0.15mm voxel size, and 37-second acquisition time in high resolution. Then, images were reconstructed in high resolution, with 0.5mm thin slices. A total of 100 exams from patients without previous diagnosis of rhinosinusitis were included in the study and were further analyzed using an open access software for medical images viewing (InVesalius 3.0, Centro de Tecnologia da Informação Renato Archer, Campinas, SP, Brazil) and a 20-inches LCD screen. Exclusion criteria was the presence of metal artifacts impairing the adequate visualization of the posterior maxilla and whole maxillary sinus; the presence of images suggesting non-odontogenic sinus pathologies, such as solid tumors; the presence of foreign bodies inside the sinus; and evidence of sinus lifting, orthognathic surgery or corrective surgeries for the treatment of maxillofacial complex fractures.

Selection of the slices, analysis of the anatomic relationship between teeth and maxillary sinus, and assessment of sinus alterations:

After the whole tomographic volume was analyzed in sagittal and coronal views, the sagittal slice that allowed the clearest visualization of the relationship between the apex and the maxillary sinus floor was selected and the linear distance between the 2 structures measured (

Figure 1). The width of the sinus membrane was measured, whenever it was apparent, in the areas immediately adjacent to each tooth. The parameters set by Nurbakhsh et al. (2011) [

44], that considered as normal, cases with up to 1mm thick membrane; mucositis when the membrane width was up to 3.54mm; and images suggestive of sinusitis in cases above 3.54mm were used as references to categorize the condition of each membrane studied (

Figure 2). Besides that, the maxillary sinus condition was assessed using the LUND-MACKAY SCORE [

45], in which, the maxillary sinus can be grouped in 3 categories according to the opacification detected on an image, being 0=completely clean sinus; 1=partial opacification; 2=complete opacification. The Lund-Mackay score was used because it is a simple score, that requires virtually no previous training and is frequently used by Otolaryngologists. [

51].

Evaluation of Dental Parameters

The distance between the most apical part of the periapical lesion of each apex to the maxillary sinus floor cortical bone was measured, and teeth divided in 5 categories: 0=absent; 1=apical periodontitis lesion not touching the sinus floor cortical bone; 2=apical periodontitis lesion in contact with the intact cortical bone; 3=apical periodontitis lesion in contact with the sinus membrane, with eroded cortical wall; 4=teeth without apical periodontitis. (

Figure 3) Additionally, the presence of endodontic treatment was registered, and a subdivision made: 0=teeth without endodontic treatment and no image suggesting apical periodontitis; 1= teeth without endodontic treatment and image suggesting apical periodontitis; 2= teeth with endodontic treatment and no image suggesting apical periodontitis; 3= teeth with endodontic treatment and image suggesting apical periodontitis.

All the CBCTs were evaluated by the same, previously calibrated, investigator (TMC) with excellent intraoperator agreement. Age and gender of the patients were also obtained from the files.

Statistics

Data were tabulated, and descriptive statistics presented: the distances from the apex of each root to the maxillary sinus floor cortical bone; the sinus membrane thickness in the area above each root; the prevalence of maxillary sinuses with images suggesting health, mucositis or sinusitis; the prevalence of each Lund-McKay score; and the prevalence of teeth with images suggesting apical periodontitis. The association between apical periodontitis and maxillary sinus alterations was investigated using a logistic regression model that included gender, age, distance and spatial relationship between apical periodontitis lesion and maxillary sinus; and membrane thickness). Chi-squared distribution was used to compare frequencies.

3. Results

One hundred CBCTs were assessed, being 76 unilateral and 24 bilateral images. A total of 124 maxillary sinuses presenting at least 1 adjacent tooth with a hypodense image, suggestive of PAC, were included in the study.

Mean age of the patients was 54.6 years old (range: 17-86 years old) and 62% of the patients were female. Figure 4 shows the mean distance (range) from the apex to the maxillary floor cortical bone for each group of teeth.

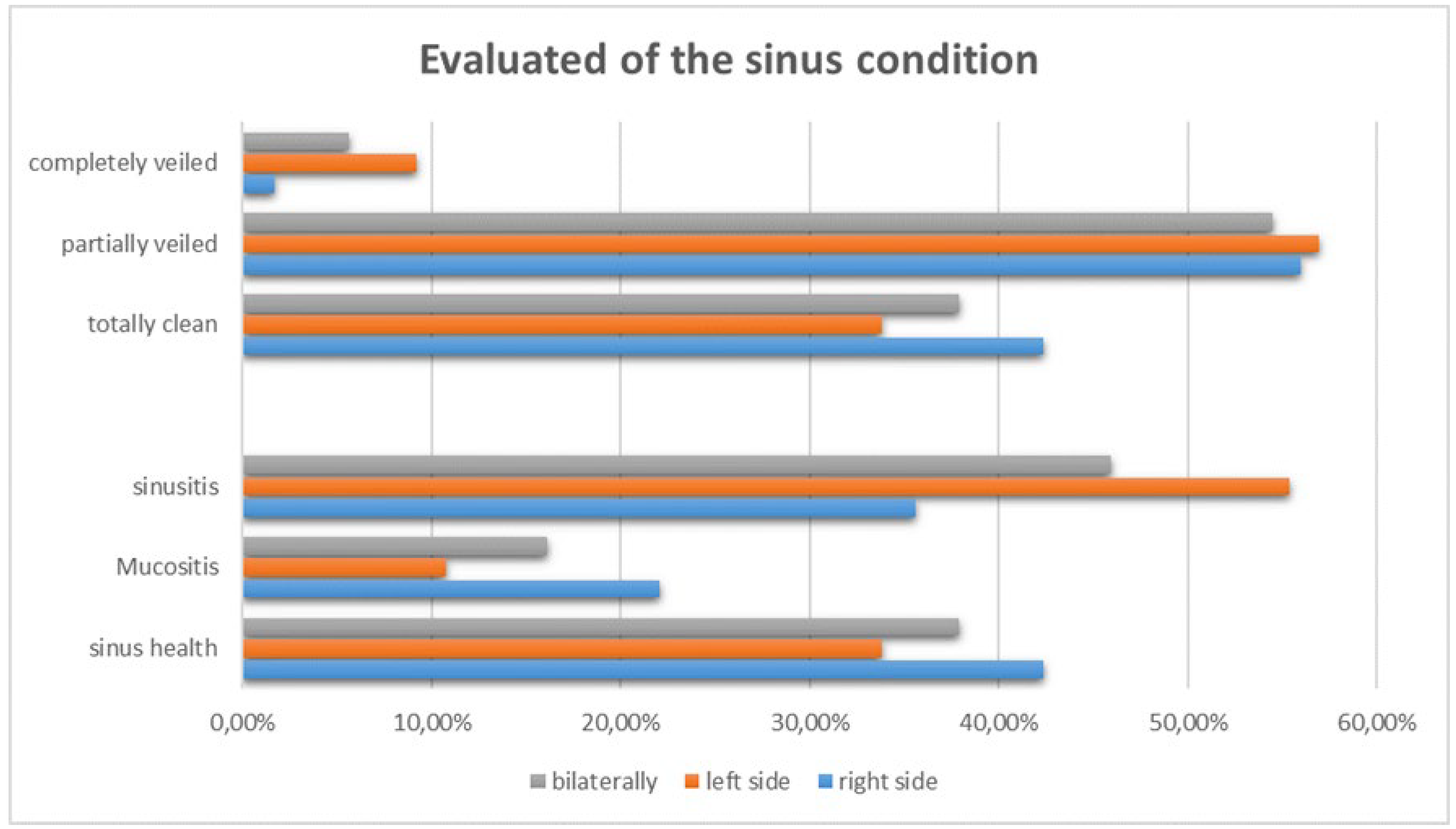

Regarding the maxillary sinus membrane thickness, in the right side, 22.03% and 35.59% of the sinuses presented images suggesting mucositis and sinusitis respectively. In the left side, 10.76% of the cases presented images suggesting mucositis, and 55.38% suggesting sinusitis.

When the whole sample was included, 16.12% and 45.96% of the sinuses presented images suggesting mucositis and sinusitis respectively, while when only the teeth with images suggesting apical periodontitis were evaluated, the prevalence of mucositis was 13.69% and of sinusitis 41.92%, with no significant differences between both groups (p>0.05).

However, when the analysis was done separately for each group, according to the relationship between the apical periodontitis and the sinus, it was observed that in the groups in which the lesion was closer to the sinus, the prevalence of mucosal thickening and sinusitis was higher.

For teeth with lesion not touching the sinus floor, there was a prevalence of 7.25% of mucositis and 9.67% of sinusitis, while in the group with lesions touching the preserved cortical floor bone the prevalence of mucositis was 4.03% but sinusitis was higher (20.16%) (p<0.01). In the group where the lesion was close to the eroded cortical wall, there were 2.41% of mucositis and 12.09% of sinusitis. (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

In the present study, a higher frequency of female patients was observed (62%), in agreement with the findings of LITTLE et al. (2018) [

46]; NUNES et al. (2016) [

47] and TROELTZSCH et al. (2015) [

18]. The average age of the sample evaluated was 54.6 years, like observed in the work of TROELTZSCH et al. (2015) [

18]. These results are consistent with the prevalence of AP described in the literature (FREDRIKSSON et al., 2017) [

48].

The maxillary sinus is an anatomical structure localized between the nasal cavity and the oral cavity, favoring greater vulnerability to the invasion of microorganisms (MEHRA & MURAD, 2004) [

21]. The roots of the premolars and molars are located below the floor of the maxillary sinus, however the greatest anatomical proximity to the maxillary sinus was described in the roots of the second upper molar, with an average distance of 1.97mm from the root apex to the floor of the sinus. Such relation is similar to the results described by MEHRA & MURAD (2004) [

21]; BROOK (2006) [

29] and MAILLET et al. (2011) [

23].

It is noteworthy that in the present study, a large range was observed for each root, highlighting the importance of individualized assessment for the diagnosis, planning and execution of endodontic treatments as well as surgical procedures performed adjacent to the floor of the sinus. In the study by MAILLET et al. (2011) [

23], molars were 11 times more likely to be associated with odontogenic sinusitis than premolars. This data agrees with the findings of the present study, suggesting that second molars should be approached endodontically in a more cautious manner to prevent overflow of filling material or irrigation solution into the maxillary sinus. In this study, bilateral first and second premolars showed a higher frequency of healthy periradicular regions. Furthermore, the premolars did not present lesions in close contact with the maxillary sinus. This last finding is basically due to its anatomical position further away from the cortical bone of the maxillary sinus (MEHRA & MURAD, 2004) [

21].

In agreement with current literature [

24,

49,

50], the high percentage of periradicular lesions can be attributed to the sensitivity of the imaging technique used, since CBCT is a three-dimensional examination that minimizes the limitations of the conventional radiographic technique. normally used in the maintenance of endodontic treatments. The images suggestive of periradicular lesions observed in this study associated with endodontically treated teeth cannot be classified into secondary or persistent periradicular lesions, or even repair, because this is a cross-sectional study. Additionally, in this study, the quality of the endodontic treatment performed was not evaluated.

Of all the images observed, 18.93% were located below the cortex of the floor of the maxillary sinus; 12.25% were in close contact with the cortex of the floor of the maxillary sinus, that was still intact; and at a lower prevalence, 4.36% of images suggestive of periradicular lesion with discontinuity of the maxillary sinus cortex were observed. The findings of this study can be compared to literature reports by BROOK (2006) [

29] and MAILLET et al. (2011) [

23], which associate the low incidence of odontogenic sinusitis, even with the high frequency of dental infections, due to the thickness of the cortical bones that constitute an effective barrier to the penetration of odontogenic infections.

To analyze the thickness of the sinus membrane and its possible relationship with sinus diseases, the measurements proposed by NURBAKHSH et al. (2011) [

44] were used. Therefore, in the sample included in the study, we observed a high prevalence of images in which the sinus membrane was thickened, being 16.12% compatible with mucositis and 45.96% compatible with sinusitis.

The relationship between the periradicular lesion and the cortical bone of the floor of the maxillary sinus, triggering possible sinus alterations/pathology, is directly related to its spatial location. In this matter, the results of our study showed that the smaller the distance between the image suggestive of periradicular lesion and the cortical bone of the floor of the maxillary sinus, the more expressive were the changes in the adjacent maxillary sinuses. When only the dental elements that presented an image suggestive of a periradicular lesion were evaluated, the prevalence of an image suggestive of mucositis was 13.69% and of an image suggestive of sinusitis was 41.92%, with no statistical difference in the total sample regarding the groups with lesion and the general prevalence (p>0.05 for both).

Comparing the findings of the present study with those described by NURBAKHSH et al. (2011) [

44], in which only elements with apical periodontitis were evaluated, a lower prevalence of cases of thickening, suggestive of mucositis was observed in our sample (13.69% versus 56%).

However, when evaluating teeth with lesions, considering the relationship between the periradicular lesion and the maxillary sinus, it was observed that in cases where the lesion was in closer contact with the maxillary sinus, there was greater thickening of the sinus membrane, with an image suggestive of sinusitis. Another interesting finding was the fact that, when evaluating only cases in which the sinus membrane measured 10mm or more (n=28 maxillary sinuses or 22.58% of cases), it was observed that in 92.85% of these cases (28 sinuses) there was at least 1 tooth with an associated periradicular lesion.

Of this total, 19 maxillary sinuses (67.85% of the total number of sinuses with extensive veiling) were associated with the presence of teeth in which lesions reached the cortical of the maxillary sinus. It is noteworthy that in only 2 cases where there was a large thickening of the sinus membrane, there was no periradicular lesion associated.

Still regarding mucous thickening, the literature reports that thickening of the sinus membrane is almost 10 times more common in individuals with periradicular lesions, with the main cause being endodontic or periodontal infection of the posterior teeth of the maxilla [

15]. However, a study by PHOTHIKHUN et al. (2012) [

1] found no association between periapical lesions and endodontic treatment and mucosal thickening, suggesting that periodontal bone loss alone could play the role in the etiology of odontogenic sinusitis.These results differ from studies by VALO et al. (2010) [

32] and BORNSTEIN et al. (2012) [

43] who observed that roots with periradicular lesions tend to have thicker sinus membranes adjacent to them when compared to roots without periapical pathology. BORNSTEIN et al. (2012) [

43] found in their study that in the group that presented periradicular lesions, the thickening of the sinus membrane was statistically greater in relation to the group that did not present a periradicular lesion. Therefore, it was concluded that conditions that violate the integrity of the maxillary sinus bone and the sinus membrane considerably increase the risk of odontogenic sinusitis. The authors also observed that the thickening most frequently found was of the flat and shallow type.

In the present study, the presence of a periradicular lesion itself was not associated with occlusion of the maxillary sinus (p=0.748). However, when evaluating the relationship between the proximity of the lesion to the maxillary sinus and the presence of veiling, it was observed that in cases where the lesion was in contact with the cortical bone of the maxillary sinus, there was a significant association between the exposition and mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinus (p=0.012). Such results are in agreement with the findings by HOSKISON et al. (2012) [

33] that found odontogenic sinusitis arising from upper posterior teeth that have a minimum or no distance to the cortex of the adjacent maxillary sinus.

5. Conclusions

The present study failed to find an association between the mere presence of periradicular lesion itself and changes in the sinus membrane or sinus pathologies, probably due to the great variability between the distances observed between the periapex and the maxillary sinus. However, the results suggest that AP in close proximity with the sinus may lead to repercussions as a result of the infectious process of dental origin. In summary, when the infection or the inflammatory tissue associated with it is located within the sinus or closely related to the maxillary sinus, the prevalence of sinus mucosa thickening/sinus pathology is greater.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, T.C. and F.V.; methodology, T.C. and F.V.; software, R.V.P; validation, T.C., M.M.A. and V.R.F.; formal analysis, L.G.; investigation, T.C.; resources, J.C.L.J..; data curation, T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C. and F.V.; writing—review and editing, T.C., F.V. and L.G. ; supervision, L.G..; project administration, F.V.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Study was approved by the Research ethics committee of the Health Sciences Center of Estácio de Sá University (protocol number 50594215.8.0000.5284) on December 10th 2015.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. By the time of the acquisition of the tomographic data, patients signed an informed consent allowing the use of the images for research and didactic purposes.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the radiology team at ODT radiology for the acquisition of the images and access to the database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Phothikhun S, Suphanantachat S, Chuenchompoonut V, Nisapakultorn K. Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Evidence of the Association Between Periodontal Bone Loss and Mucosal Thickening of the Maxillary Sinus. J Periodontol. 2012 May;83(5):557–64. [CrossRef]

- Schneider AC, Bragger U, Sendi P, Caversaccio MD, Buser D, Bornstein MM. Characteristics and Dimensions of the Sinus Membrane in Patients Referred for Single-Implant Treatment in the Posterior Maxilla: A Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2020 Aug 19];28(2):587–96. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=08822786&AN=86217694&h=kIJ9v9tFXs%2FvIdK7K00x51uU6bZLmsUO6o%2BOK4r7JHqiJWnZC%2Bfd4QyVEtH7A4pF7lksMZ%2BUYAj971Y6sWcQbg%3D%3D&crl=c.

- Shanbhag S, Karnik P, Shirke P, Shanbhag V. Association between periapical lesions and maxillary sinus mucosal thickening: A retrospective cone-beam computed tomographic study. J Endod [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2020 Aug 19];39(7):853–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0099239913003221. [CrossRef]

- Nunes CABCM, Guedes OA, Alencar AHG, Peters OA, Estrela CRA, Estrela C. Evaluation of Periapical Lesions and Their Association with Maxillary Sinus Abnormalities on Cone-beam Computed Tomographic Images. J Endod [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Aug 19];42(1):42–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2015.09.014. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui F, Smith R V., Yom SS, Beitler JJ, Busse PM, Cooper JS, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® nasal cavity and paranasal sinus cancers. Head Neck. 2017 Mar 1;39(3):407–18. [CrossRef]

- Pazera P, Bornstein MM, Pazera A, Sendi P, Katsaros C. Incidental maxillary sinus findings in orthodontic patients: A radiographic analysis using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). Orthod Craniofacial Res. 2011 Feb;14(1):17–24. [CrossRef]

- Mathew AL, Sholapurkar AA, Pai KM. Maxillary sinus findings in the elderly: A panoramic radiographic study. J Contemp Dent Pract [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2020 Aug 19];10(6):41–8. Available from: http://www.thejcdp.com/journal/. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams JJ, Glassberg RM. Dental disease: a frequently unrecognized cause of maxillary sinus abnormalities? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(5):1219–23.

- Savolainen S, Eskelin M, Jousimies-Somer H, Ylikoski J. Radiological findings in the maxillary sinuses of symptomless young men. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117(sup529):153–7. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson M. Rhinosinusitis in oral medicine and dentistry. Vol. 59, Australian dental journal. 2014. p. 289–95. [CrossRef]

- Chen HJ, Chen H Sen, Chang YL, Huang YC. Complete unilateral maxillary sinus opacity in computed tomography. J Formos Med Assoc [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2020 Aug 19];109(10):709–15. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929664610601155.

- Longhini AB, Branstetter BF, Ferguson BJ. Otolaryngologists’ perceptions of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2012 Sep;122(9):1910–4. [CrossRef]

- Pokorny A, Tataryn R. Clinical and radiologic findings in a case series of maxillary sinusitis of dental origin. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013 Dec;3(12):973–9. [CrossRef]

- Patel NA, Ferguson BJ. Odontogenic sinusitis: an ancient but under-appreciated cause of maxillary sinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;20(1):24–8.

- Vidal F, Coutinho TM, Carvalho Ferreira D de, Souza RC de, Gonçalves LS. Odontogenic sinusitis: a comprehensive review. Vol. 75, Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2017. p. 623–33. [CrossRef]

- Simuntis R, Kubilius R, Vaitkus S. Odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: a review. Stomatologija. 2014;16(2):39–43.

- Matsumoto Y, Ikeda T, Yokoi H, Kohno N. Association between odontogenic infections and unilateral sinus opacification. Auris Nasus Larynx [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Aug 19];42(4):288–93. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0385814615000048. [CrossRef]

- Troeltzsch M, Pache C, Troeltzsch M, Kaeppler G, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S, et al. Etiology and clinical characteristics of symptomatic unilateral maxillary sinusitis: A review of 174 cases. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Aug 19];43(8):1522–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1010518215002474. [CrossRef]

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, Hellings PW, Kern R, Reitsma S, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020;58(Supplement 29):1–464.

- Ly D, Hellgren J. Is dental evaluation considered in unilateral maxillary sinusitis? A retrospective case series. Acta Odontol Scand [Internet]. 2018 Nov 17 [cited 2020 Aug 19];76(8):600–4. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iode20. [CrossRef]

- Mehra P, Murad H. Maxillary sinus disease of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37(2):347–64. [CrossRef]

- Maloney PL, Doku HC. Maxillary sinusitis of odontogenic origin. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor). 1968;34(11):591.

- Maillet M, Bowles WR, McClanahan SL, John MT, Ahmad M. Cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of maxillary sinusitis. J Endod [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2020 Aug 19];37(6):753–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0099239911002524. [CrossRef]

- Kruse C, Spin-Neto R, Wenzel A, Kirkevang LL. Cone beam computed tomography and periapical lesions: A systematic review analysing studies on diagnostic efficacy by a hierarchical model. Vol. 48, International Endodontic Journal. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2015. p. 815–28. [CrossRef]

- Shahbazian M, Vandewoude C, Wyatt J, Jacobs R. Comparative assessment of periapical radiography and CBCT imaging for radiodiagnostics in the posterior maxilla. Odontology. 2015;103(1):97–104. [CrossRef]

- Campello A, Gonçalves L, Guedes F, Marques F. Cone-beam computed tomography versus digital periapical radiography in the detection of artificially created periapical lesions: A pilot study of the diagnostic accuracy of endodontists using both techniques. Imaging Sci Dent. 2017 Mar;47(1):25-31. [CrossRef]

- Patel S, Brown J, Semper M, Abella F, Mannocci F. European society of endodontology position statement: use of cone beam computed tomoraphy in endodontics. Int Endod J. 2019. 52:1675-1678.

- de Lima CO, Devito KL, Baraky Vasconcelos LR, Prado M do, Campos CN. Correlation between Endodontic Infection and Periodontal Disease and Their Association with Chronic Sinusitis: A Clinical-tomographic Study. J Endod [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Aug 19];43(12):1978–83. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2017.08.014. [CrossRef]

- Brook I. Sinusitis of odontogenic origin. Vol. 135, Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2006. p. 349–55.

- Ok E, Güngör E, Colak M, Altunsoy M, Nur BG, Ağlarci OS. Evaluation of the relationship between the maxillary posterior teeth and the sinus floor using cone-beam computed tomography. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014. 36:907-914. [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi M, Pozve NJ, Khorrami L. Using cone beam computed tomography to detect the relationship between the periodontal bone loss and mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinus. Dent Res J (Isfahan) [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Aug 19];11(4):495–501. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc4163829/.

- Vallo J, Suominen-Taipale L, Huumonen S, Soikkonen K, Norblad A. Prevalence of mucosal abnormalities of the maxillary sinus and their relationship to dental disease in panoramic radiography: results from the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontology. 2010;109(3): e80–7. [CrossRef]

- Hoskison E, Daniel M, Rowson JE, Jones NS. Evidence of an increase in the incidence of odontogenic sinusitis over the last decade in the UK. J Laryngol Otol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 19];126(1):43–6. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51657360. [CrossRef]

- Costa F, Emanuelli E, Robiony M, Zerman N, Polini F, Politi M. Endoscopic Surgical Treatment of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis of Dental Origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2020 Aug 19];65(2):223–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278239106013991. [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi F, Esmaeelinejad M, Safai P. Etiologies and treatments of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: A systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 17, Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2015 [cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc4706849/.

- Lee KC, Lee SJ. Clinical features and treatments of odontogenic sinusitis. Yonsei Med J. 2010 Nov;51(6):932–7. [CrossRef]

- Badarne O, Koudstaal MJ, van Elswijk JF, Wolvius EB. Odontogenic maxillary sinusitis based on overextension of root canal filling material. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 19];119(10):480–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23126175.

- Longhini AB, Branstetter BF, Ferguson BJ. Unrecognized odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: A cause of endoscopic sinus surgery failure. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010 Jul;24(4):296–300. [CrossRef]

- Akhaddar A, Elasri F, Elouennass M, Mahi M, Elomari N, Elmostarchid B, et al. Orbital abscess associated with sinusitis from odontogenic origin. Intern Med [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2020 Aug 19];49(5):523–4. Available from: http://www.naika.or.jp/imindex.html. [CrossRef]

- Hoxworth JM, Glastonbury CM. Orbital and intracranial complications of acute sinusitis [Internet]. Vol. 20, Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2010 [cited 2020 Aug 19]. p. 511–26. Available from: https://www.neuroimaging.theclinics.com/article/S1052-5149(10)00076-6/abstract.

- Martines F, Salvago P, Ferrara S, Mucia M, Gambino A, Sireci F. Parietal subdural empyema as complication of acute odontogenic sinusitis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014 Aug 21;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Vestin Fredriksson M, Öhman A, Flygare L, Tano K. When Maxillary Sinusitis Does Not Heal: Findings on CBCT Scans of the Sinuses with a Particular Focus on the Occurrence of Odontogenic Causes of Maxillary Sinusitis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017 Dec;2(6):442–6.

- Bornstein MM, Wasmer J, Sendi P, Janner SFM, Buser D, Von Arx T. Characteristics and dimensions of the Schneiderian membrane and apical bone in maxillary molars referred for apical surgery: a comparative radiographic analysis using limited cone beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2012;38(1):51–7. [CrossRef]

- Nurbakhsh B, Friedman S, Kulkarni G V, Basrani B, Lam E. Resolution of maxillary sinus mucositis after endodontic treatment of maxillary teeth with apical periodontitis: a cone-beam computed tomography pilot study. J Endod. 2011;37(11):1504–11. [CrossRef]

- Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993; 31:183.

- Little RE, Long CM, Loehrl TA, Poetker DM. Odontogenic sinusitis: a review of the current literature. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018. 3:110-114. [CrossRef]

- Nunes CA, Guedes OA, Alencar AH, Peters OA, Estrela CR, Estrela C. Evaluation of periapical lesions and their association with maxillary sinus abnormalities on cone-beam computed tomographic images. J Endod. 2016. 42:42-46. [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson MV, Öhman A, Flygare L, Tano K. When maxillary sinusitis does not heal: findings on cbct scans of the sinuses with a particular focus on the occurrence of odontogenic causes of maxillary sinusitis? Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017. 2:442-446.

- Lima AD, Benetti F, Ferreira LL, Dezan-Júnior E, Gomes-Filho JE, Cintra LTA. Endodontic applications of cone-beam computed tomography. BJSCR. 2014. 6:30-39.

- Ponce JB, Guimarães BM, Pinto LC, NIshiyama CK, Almeida ALPF. Tamanho do voxel no diagnóstico tomográfico em endodontia. Salusvita. 2014. 33:257-267.

- Hopkins C, Browne JP, Slack R, Lund V, Brown P. The Lund-Mackay staging system for chronic rhinosinisitis: how is it used and what does it predict? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007. 137: 555-561.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).