Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

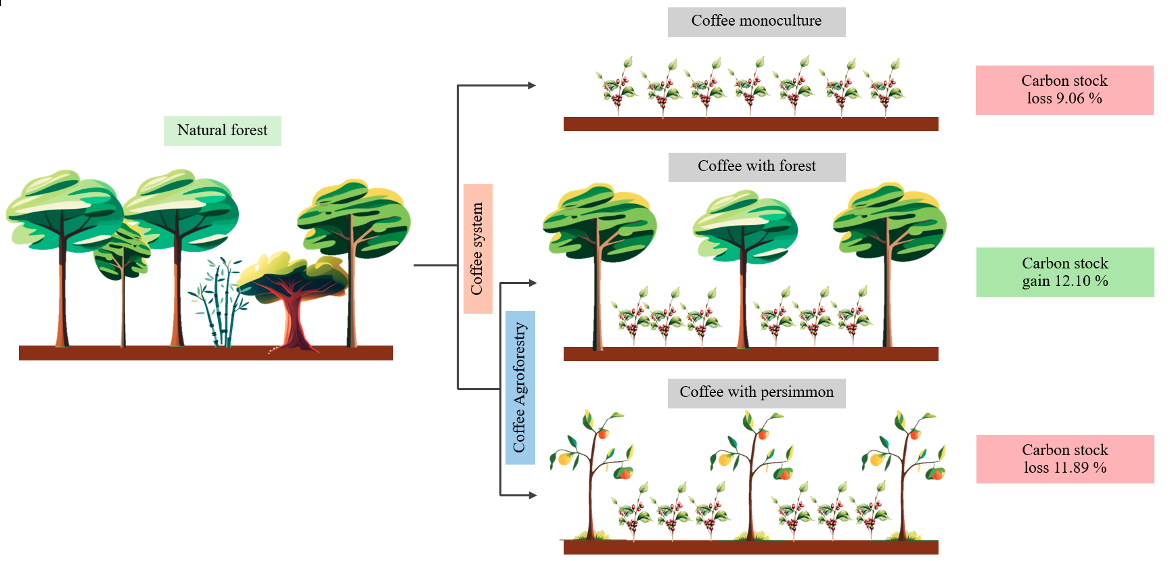

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

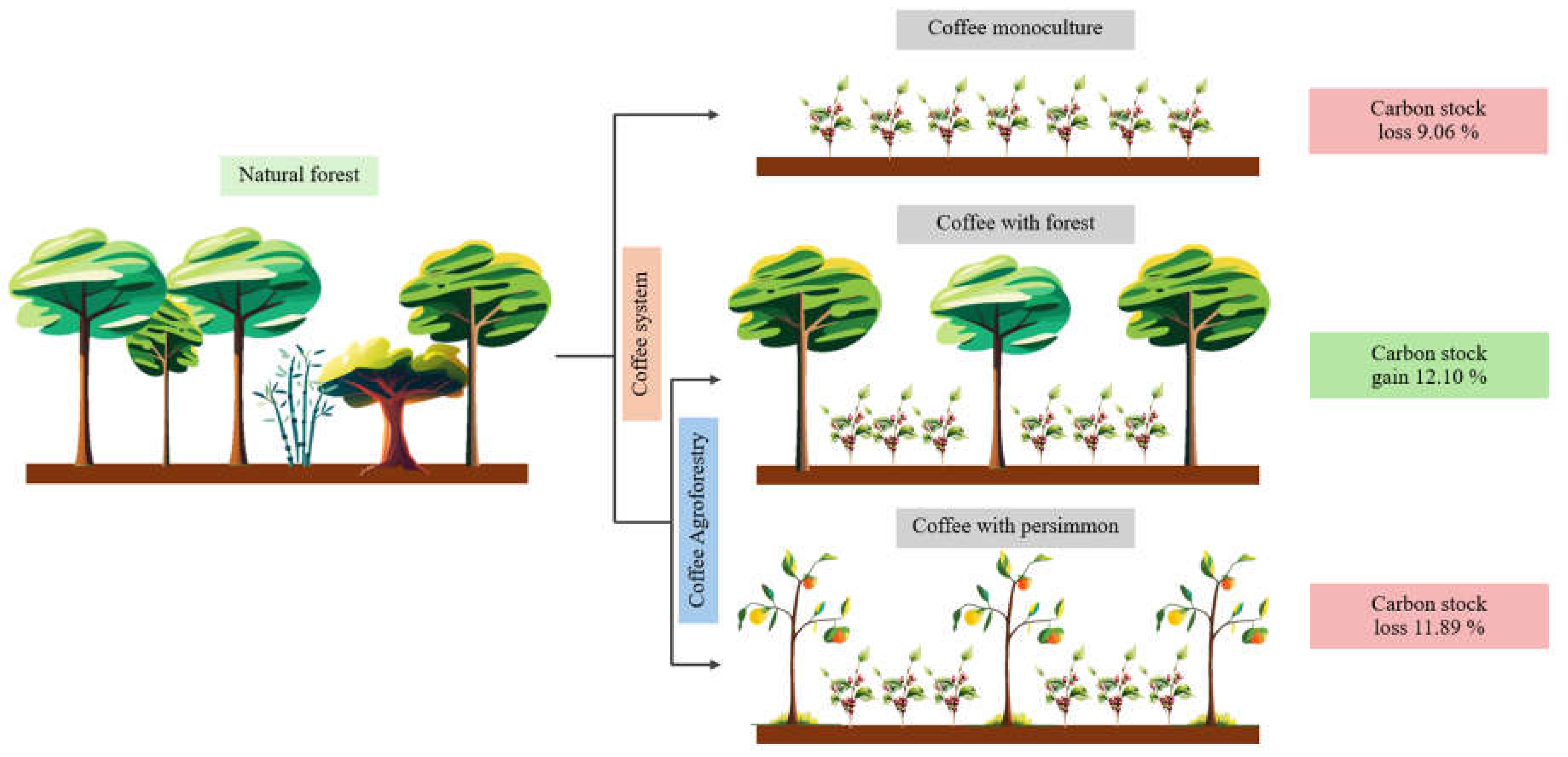

2.1. Study Area

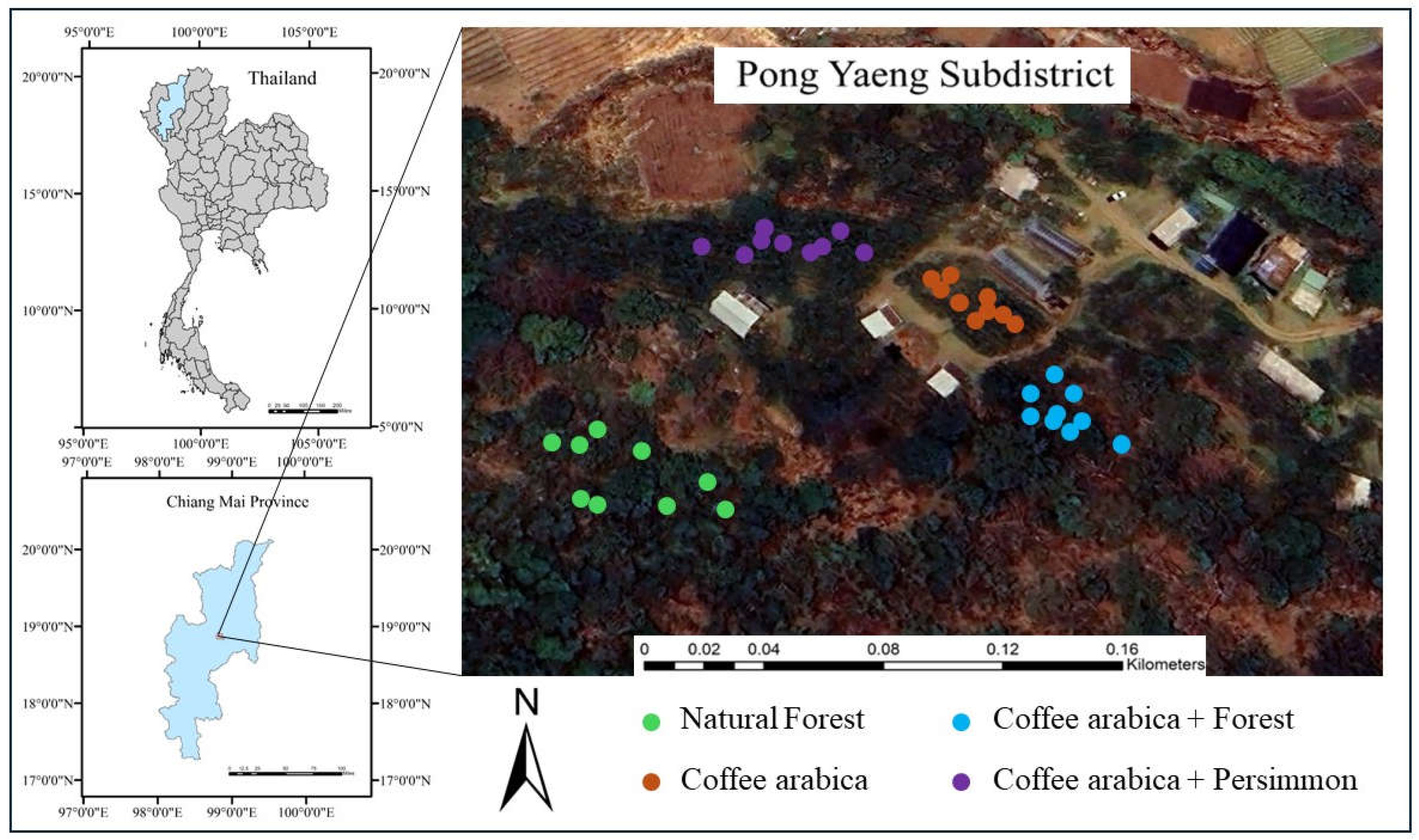

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Soil Physicochemical and Microbial Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Result

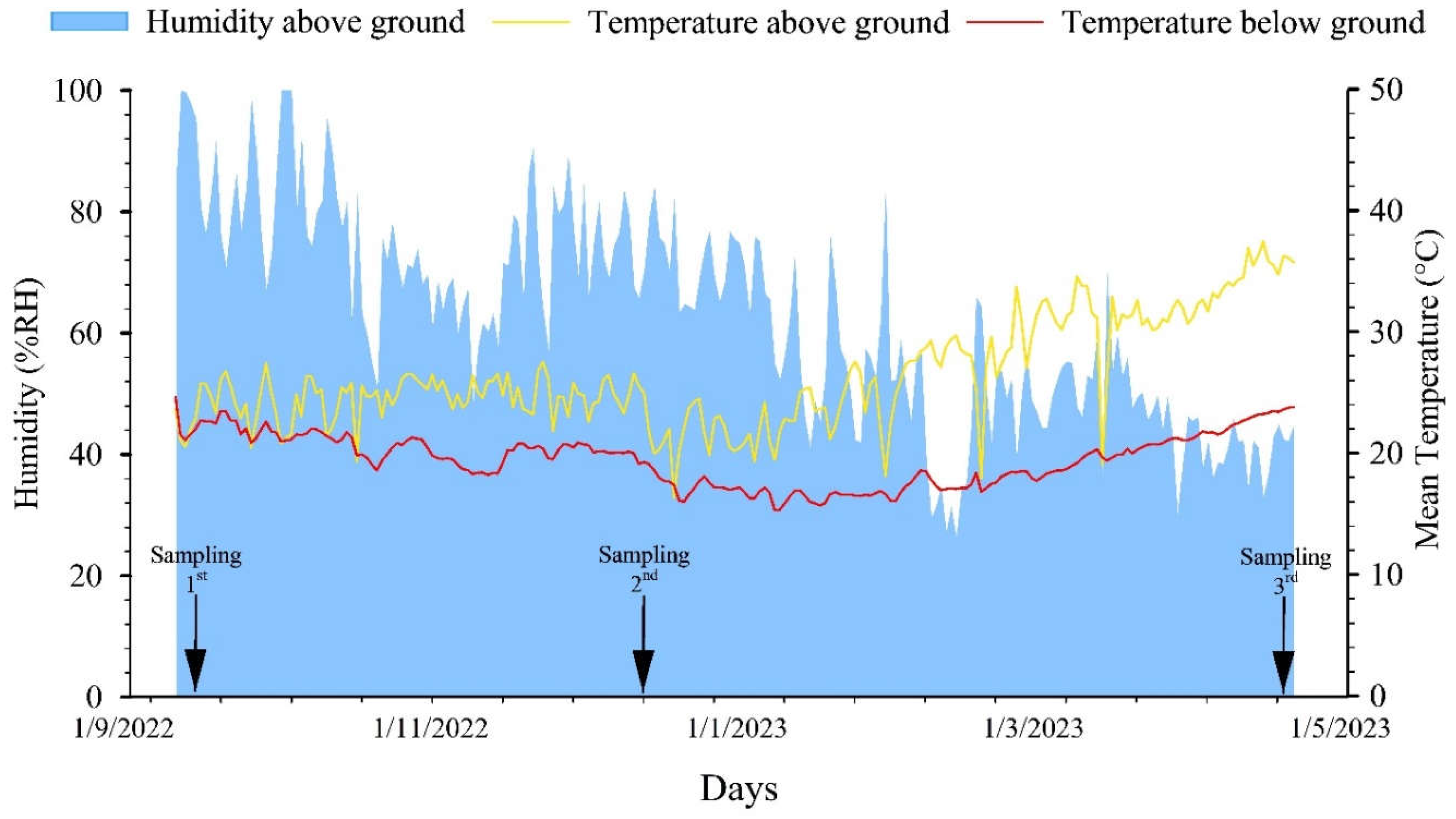

3.1. Soil Physical and Chemical Characteristics Before Experiment

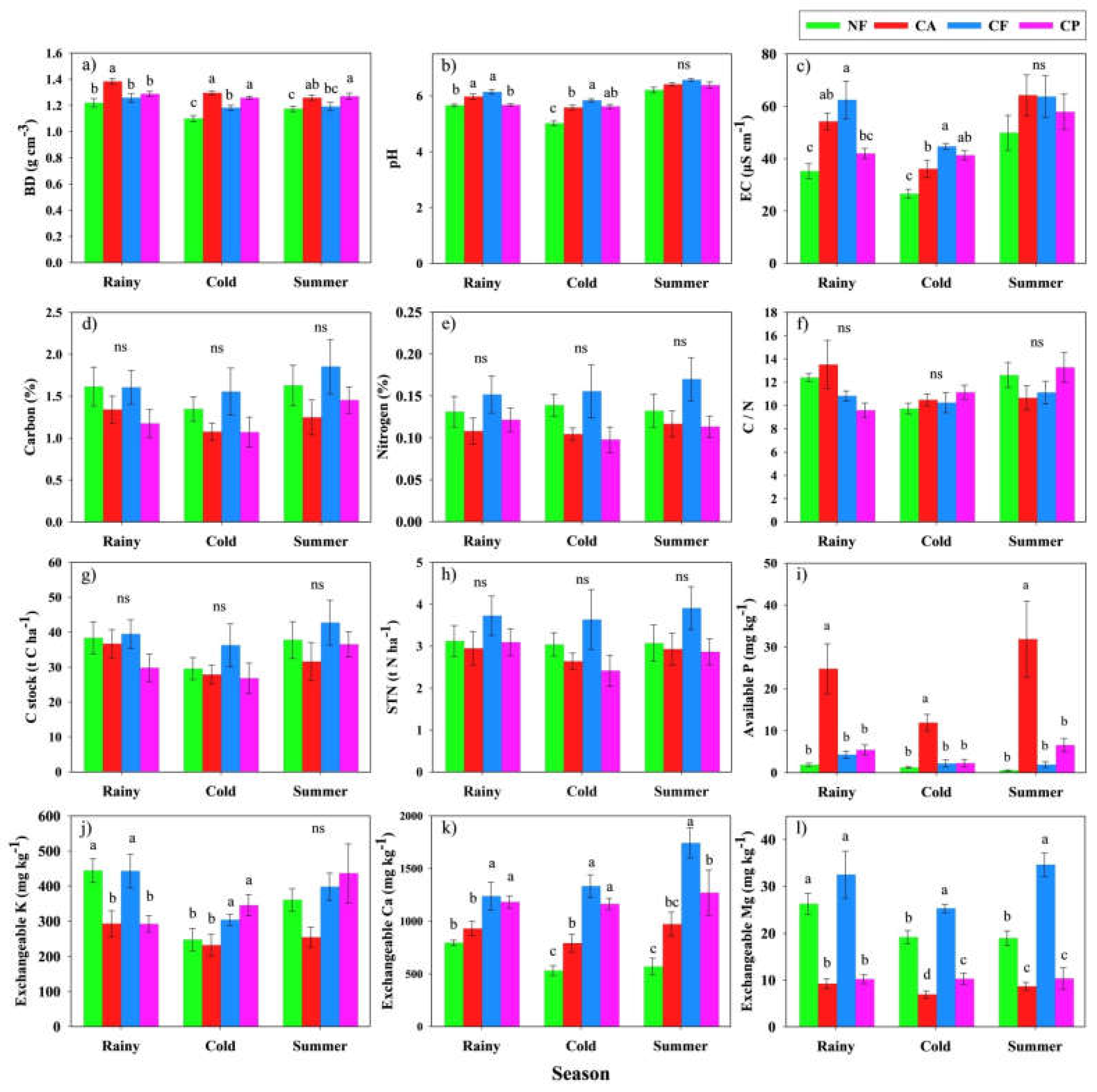

3.2. Changes in Soil Characteristics across the Different Land Uses and Seasons

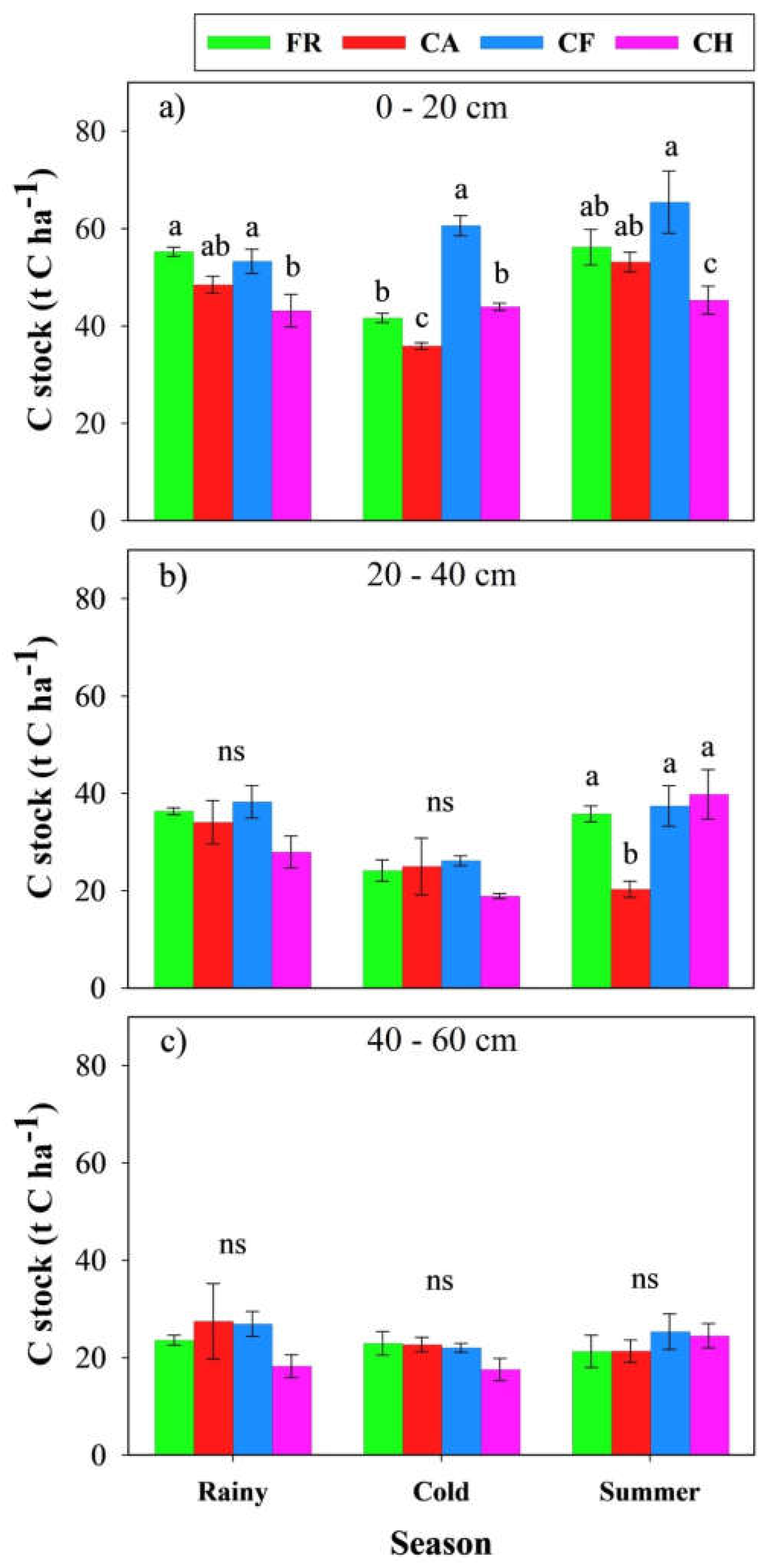

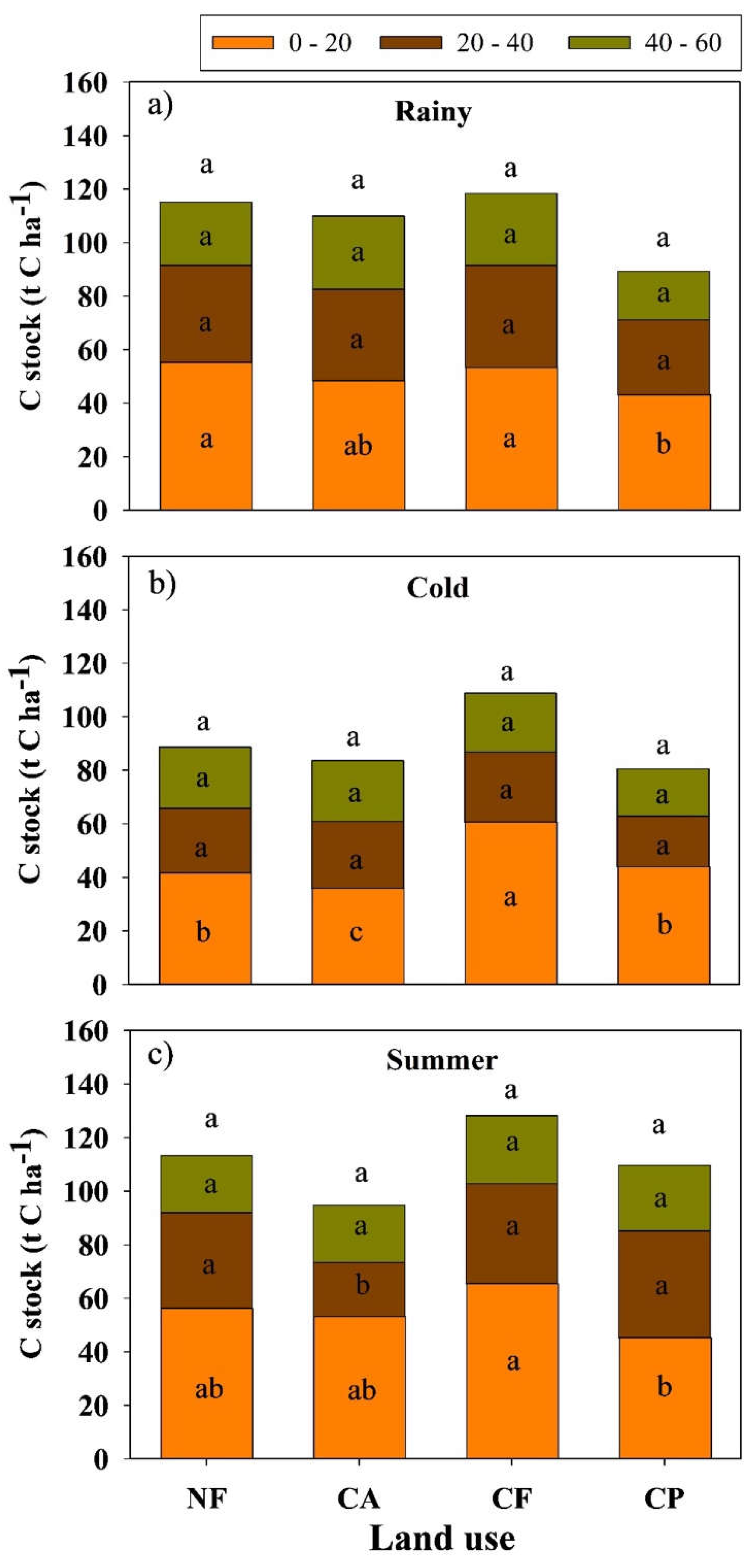

3.3. Impacts of Coffee Agroforestry Systems on Soil Carbon Stock

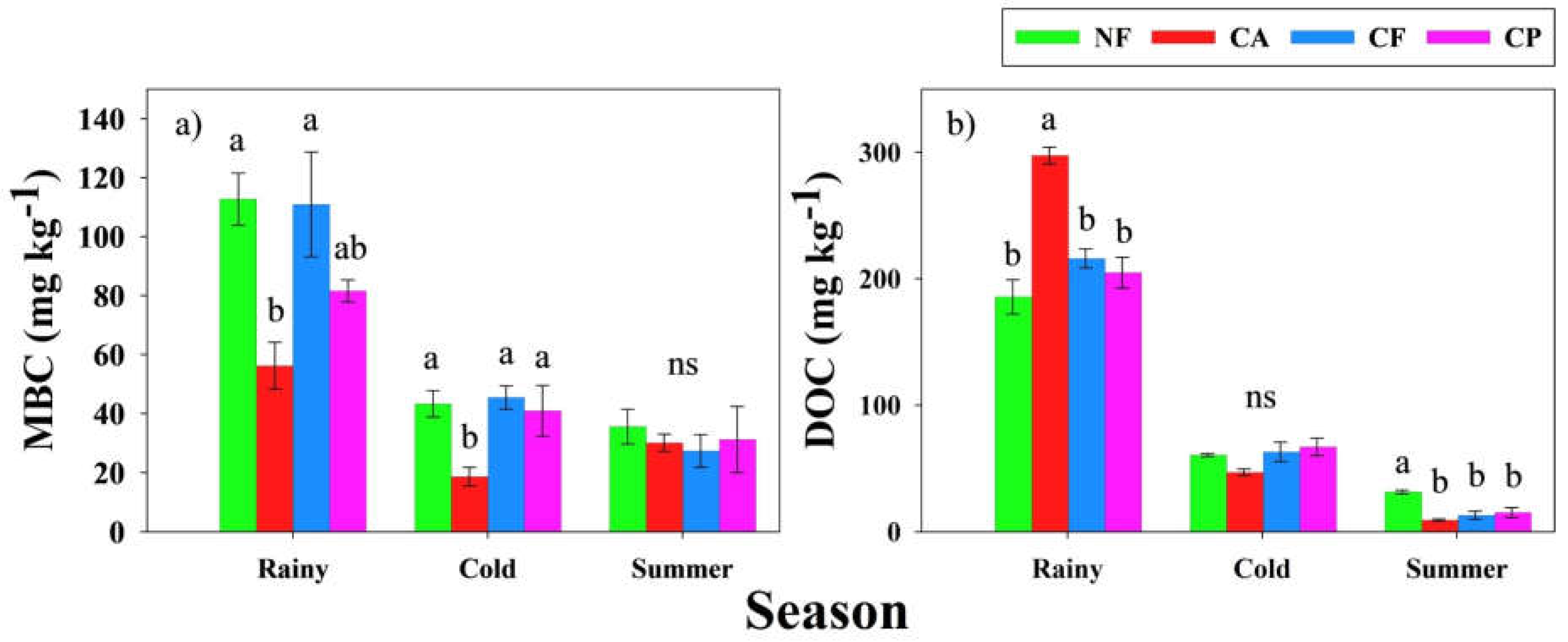

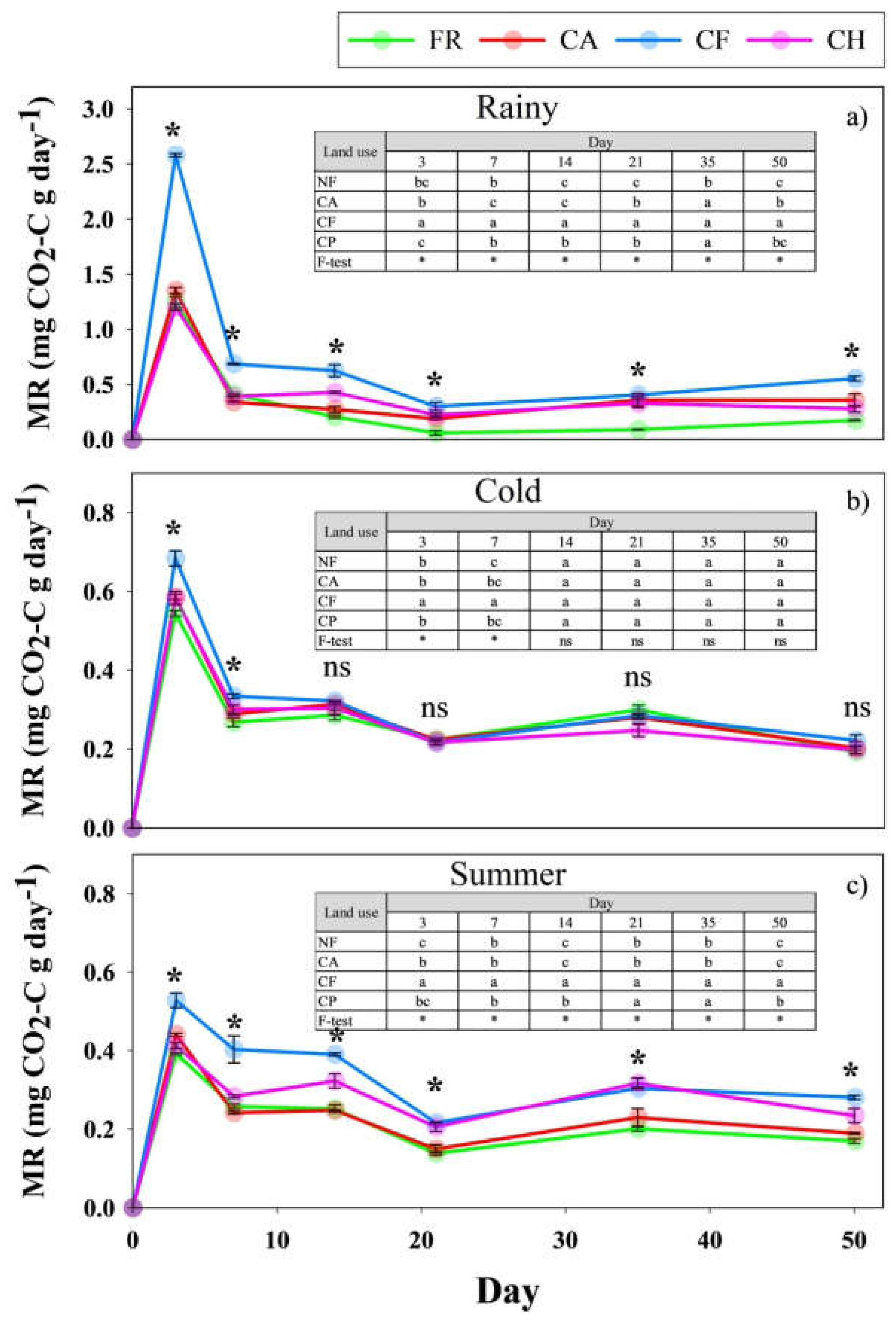

3.4. Impacts of Coffee Agroforestry Systems on Microbial Activity

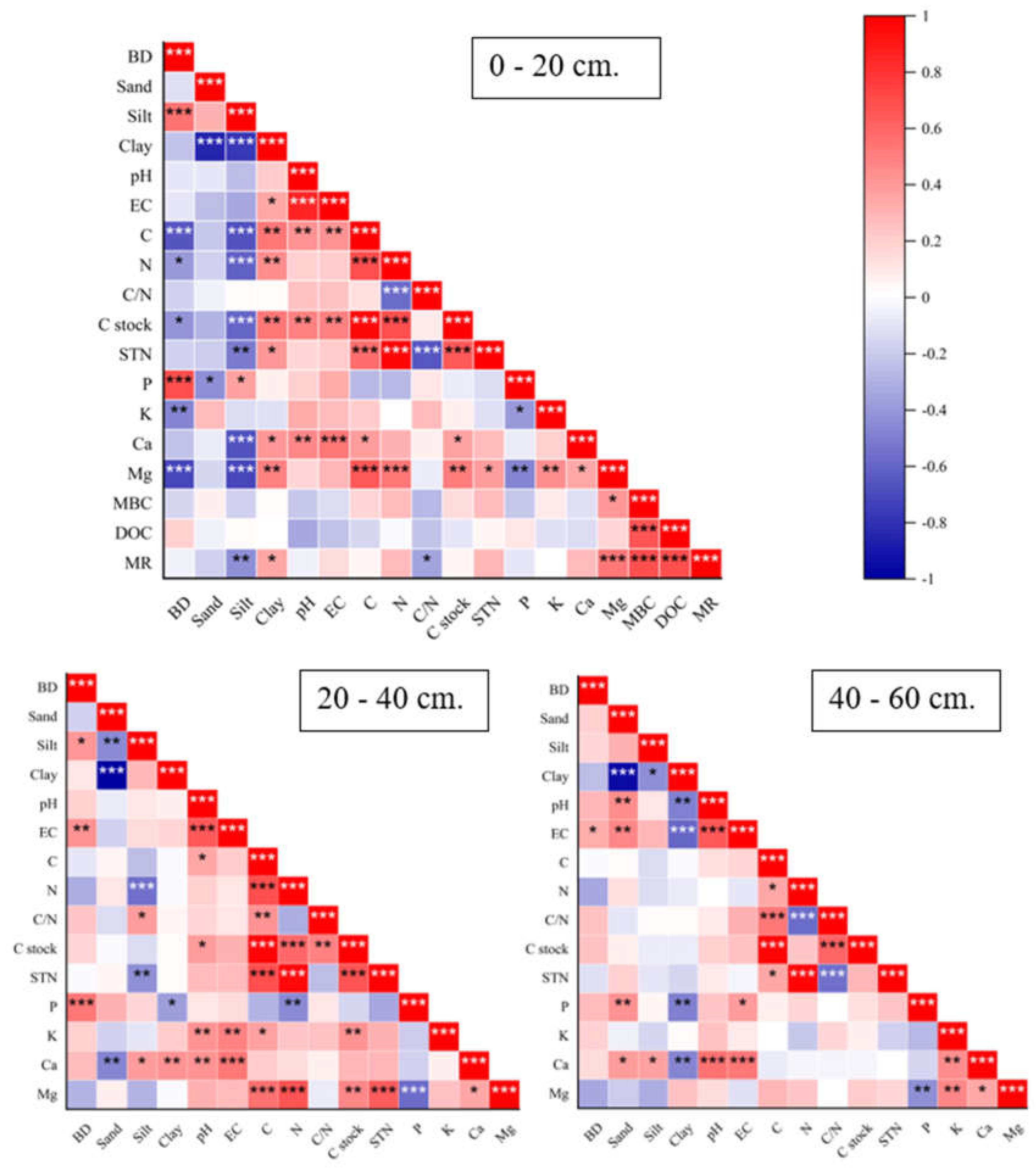

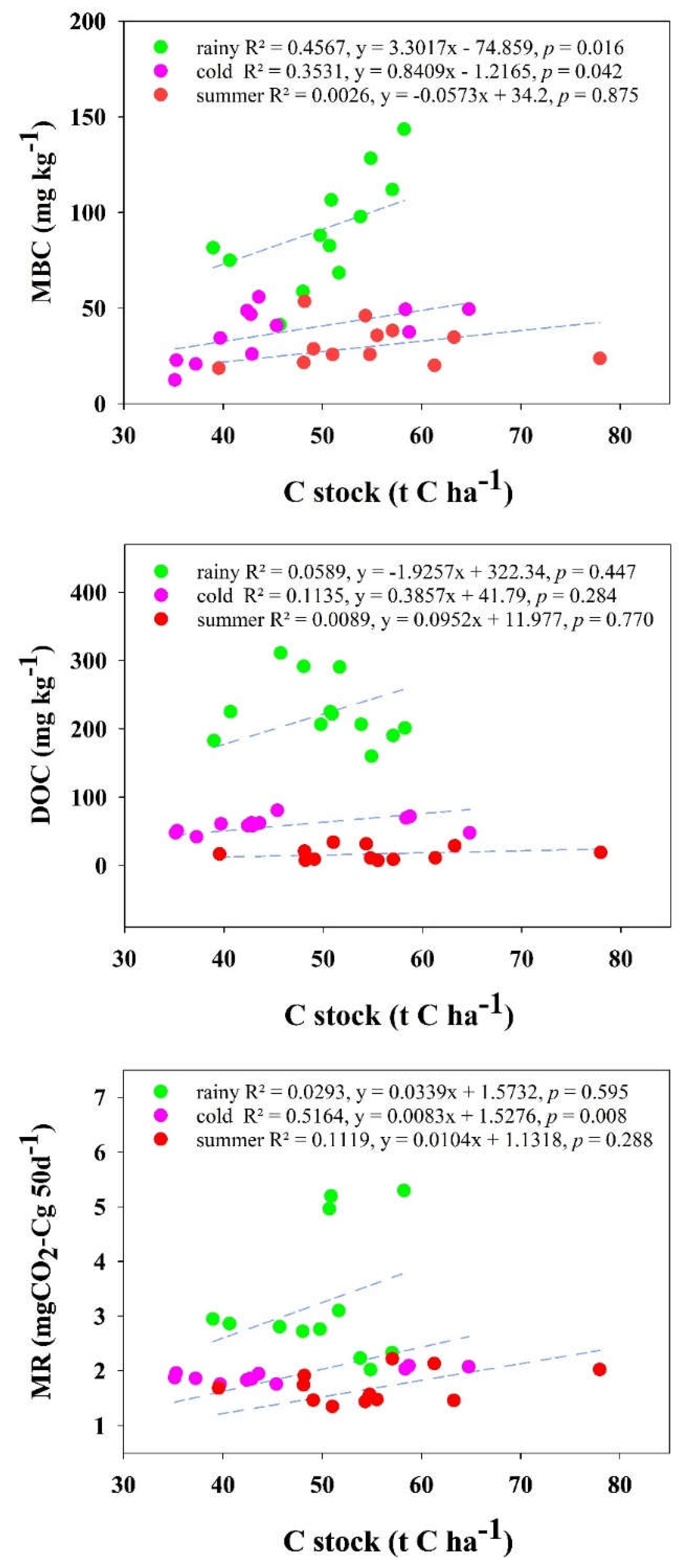

3.5. Relationships of Soil Parameters Through Linear Regression Correlation and Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Physical and Chemical Characteristics

4.2. Soil Carbon Stock Across Different Land Use Types

4.3. Soil Microbial Respiration and Microbial Biomass Carbon

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adiyah, F., Csorba, Á., Dawoe, E., Ocansey, C. M., Asamoah, E., Szegi, T., Fuchs, M., & Michéli, E. (2023a). Soil organic carbon changes under selected agroforestry cocoa systems in Ghana. Geoderma Regional, 35. [CrossRef]

- Angkasith, P. (2002). Coffee production status and potential of organic Arabica coffee in Thailand. AU Journal of Technology, 5(3).

- Aquino, B. F., & Hanson, R. G. (1984). Soil phosphorus supplying capacity evaluated by plant removal and available phosphorus extraction. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 48(5), 1091–1096.

- Arun Jyoti, N., Lal, R., & Das, A. K. (2015). Ethnopedology and soil quality of bamboo (Bambusa sp.) based agroforestry system. Science of the Total Environment, 521–522, 372–379. [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N., Kongsurakan, P., Solomon, L. W., & Sereenonchai, S. (2024). Fire Impacts on Soil Properties and Implications for Sustainability in Rotational Shifting Cultivation: A Review. Agriculture, 14(9), 1660.

- Bania, J. K., Sileshi, G. W., Nath, A. J., Paramesh, V., & Das, A. K. (2024). Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon and macronutrients in the deep soil across a chronosequence of tea agroforestry. Catena, 236. [CrossRef]

- Castro, J., Fernández-Ondoño, E., Rodríguez, C., Lallena, A. M., Sierra, M., & Aguilar, J. (2008). Effects of different olive-grove management systems on the organic carbon and nitrogen content of the soil in Jaén (Spain). Soil and Tillage Research, 98(1), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Chase, P., & Singh, O. P. (2014). Soil nutrients and fertility in three traditional land use systems of Khonoma, Nagaland, India. Resources and Environment, 4(4), 181–189.

- Chen, C., Liu, W., Jiang, X., & Wu, J. (2017). Effects of rubber-based agroforestry systems on soil aggregation and associated soil organic carbon: Implications for land use. Geoderma, 299, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro-Domínguez, N., Palma, J. H. N., Paulo, J. A., Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A., & Mosquera-Losada, M. R. (2022). Assessment of soil carbon storage in three land use types of a semi-arid ecosystem in South Portugal. Catena, 213. [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A. J. (2005). Soil organic carbon sequestration and agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in the southeastern USA. Soil and Tillage Research, 83(1 SPEC. ISS.), 120–147. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M., Nakamura, S., Fonseca, A. da C. L., Nasukawa, H., Ibraimo, M. M., Naruo, K., Kobayashi, K., & Oya, T. (2017). Evaluation of the Mehlich 3 reagent as an extractant for cations and available phosphorus for soils in Mozambique. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 48(12), 1462–1472.

- Gee, G. W., & Or, D. (2002). 2.4 Particle-size analysis. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 4 Physical Methods, 5, 255–293.

- Grüneberg, E., Ziche, D., & Wellbrock, N. (2014). Organic carbon stocks and sequestration rates of forest soils in Germany. Global Change Biology, 20(8), 2644–2662. [CrossRef]

- Guillot, E., Hinsinger, P., Dufour, L., Roy, J., & Bertrand, I. (2019). With or without trees: Resistance and resilience of soil microbial communities to drought and heat stress in a Mediterranean agroforestry system. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 129, 122–135. [CrossRef]

- Heimsch, L., Huusko, K., Karhu, K., Mganga, K. Z., Kalu, S., & Kulmala, L. (2023). Effects of a tree row on greenhouse gas fluxes, growing conditions and soil microbial communities on an oat field in Southern Finland. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 352. [CrossRef]

- Hergoualc’h, K., Blanchart, E., Skiba, U., Hénault, C., & Harmand, J. M. (2012). Changes in carbon stock and greenhouse gas balance in a coffee (Coffea arabica) monoculture versus an agroforestry system with Inga densiflora, in Costa Rica. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 148, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C., Araujo, P. I., Hess, L. J. T., Vivanco, L., Kaye, J., & Austin, A. T. (2023). Metal cation concentrations improve understanding of controls on soil organic carbon across a precipitation by vegetation gradient in the Patagonian Andes. Geoderma, 440. [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, M., Selvi, D., Thiyageshwari, S., Srinivasarao, C., Kalaiselvi, T., Lourdusamy, K., Kumaraperumal, R., & Allan, V. (2023). Soil Carbon Dynamics Under Different Ecosystems of Ooty Region in the Western Ghats Biodiversity Hotspot of India. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 23(1), 1374–1385. [CrossRef]

- Jinger, D., Kakade, V., Bhatnagar, P. R., Paramesh, V., Dinesh, D., Singh, G., N, N. K., Kaushal, R., Singhal, V., Rathore, A. C., Tomar, J. M. S., Singh, C., Yadav, L. P., Jat, R. A., Kaledhonkar, M. J., & Madhu, M. (2024). Enhancing productivity and sustainability of ravine lands through horti-silviculture and soil moisture conservation: A pathway to land degradation neutrality. Journal of Environmental Management, 364. [CrossRef]

- Kamolrattanakul, K., Tungkananuruk, K., Rungratanaubon, T., & Sillberg, C. V. (2022). Analytical Approach to Deforestation Effect on Climate Change Using Metadata in Thailand. EnvironmentAsia, 15(1).

- Kamthonkiat, D., Thanyapraneedkul, J., Nuengjumnong, N., Ninsawat, S., Unapumnuk, K., & Vu, T. T. (2021). Identifying priority air pollution management areas during the burning season in Nan Province, Northern Thailand. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(4), 5865–5884.

- Karunaratne, S., Asanopoulos, C., Jin, H., Baldock, J., Searle, R., Macdonald, B., & Macdonald, L. M. (2024). Estimating the attainable soil organic carbon deficit in the soil fine fraction to inform feasible storage targets and de-risk carbon farming decisions. Soil Research , 62(2). [CrossRef]

- Klute, A. (1986). Part 1. Physical and mineralogical methods. Methods of Soil Analysis.

- Leifeld, J., Siebert, S., & Kögel-Knabner, I. (2002). Changes in the chemical composition of soil organic matter after application of compost. European Journal of Soil Science, 53(2), 299–309.

- Lilavanichakul, A. (2020). The economic impact of Arabica coffee farmers’ participation in geographical indication in northern Highland of Thailand. Journal of Rural Problems, 56(3), 124–131.

- Llorente, M., & Turrión, M. B. (2010). Microbiological parameters as indicators of soil organic carbon dynamics in relation to different land use management. European Journal of Forest Research, 129(1), 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K., & Lal, R. (2005). The depth distribution of soil organic carbon in relation to land use and management and the potential of carbon sequestration in subsoil horizons. Advances in Agronomy, 88, 35–66.

- Lori, M., Armengot, L., Schneider, M., Schneidewind, U., Bodenhausen, N., Mäder, P., & Krause, H. M. (2022). Organic management enhances soil quality and drives microbial community diversity in cocoa production systems. Science of the Total Environment, 834. [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V. P., Zhai, P., Pirani, S. L., Connors, C., Péan, S., Berger, N., Caud, Y., Chen, L., Goldfarb, M. I., & Scheel Monteiro, P. M. (2021). Ipcc, 2021: Summary for policymakers. in: Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. contribution of working group i to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change.

- Mehta, H., Rathore, A. C., Tomar, J. M. S., Mandal, D., Kumar, P., Kumar, S., Sharma, S. K., Kaushal, R., Singh, C., Chaturvedi, O. P., & Madhu, M. (2024). Minor millets based agroforestry of multipurpose tree species of Bhimal (Grewia optiva Drummond J.R. ex Burret) and Mulberry (Morus alba L.) for resource conservation and production in north western Himalayas – 10-year study. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 359. [CrossRef]

- Melero, S., López-Garrido, R., Murillo, J. M., & Moreno, F. (2009). Conservation tillage: Short- and long-term effects on soil carbon fractions and enzymatic activities under Mediterranean conditions. Soil and Tillage Research, 104(2), 292–298. [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M. J., Li, G., Nazir, M. M., Zulfiqar, F., Siddique, K. H. M., Iqbal, B., & Du, D. (2024). Harnessing soil carbon sequestration to address climate change challenges in agriculture. In Soil and Tillage Research (Vol. 237). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Negash, M., Kaseva, J., & Kahiluoto, H. (2022). Determinants of carbon and nitrogen sequestration in multistrata agroforestry. Science of the Total Environment, 851. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D. W., & Sommers, L. E. (1982). Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 9, 539–579.

- Niether, W., Schneidewind, U., Fuchs, M., Schneider, M., & Armengot, L. (2019). Below- and aboveground production in cocoa monocultures and agroforestry systems. Science of the Total Environment, 657, 558–567. [CrossRef]

- Noponen, M. R. A., Healey, J. R., Soto, G., & Haggar, J. P. (2013). Sink or source-The potential of coffee agroforestry systems to sequester atmospheric CO2 into soil organic carbon. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 175, 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Noppakoonwong, U., Khomarwut, C., Hanthewee, M., Jarintorn, S., Hassarungsee, S., Meesook, S., Daoruang, C., Naka, P., Lertwatanakiat, S., & Satayawut, K. (2014). Research and development of Arabica coffee in Thailand. Proc. 25th International Conference on Coffee Science (ASIC), 8–13.

- Oscar Kisaka, M., Shisanya, C., Cournac, L., Raphael Manlay, J., Gitari, H., & Muriuki, J. (2023a). Integrating no-tillage with agroforestry augments soil quality indicators in Kenya’s dry-land agroecosystems. Soil and Tillage Research, 227. [CrossRef]

- Oscar Kisaka, M., Shisanya, C., Cournac, L., Raphael Manlay, J., Gitari, H., & Muriuki, J. (2023b). Integrating no-tillage with agroforestry augments soil quality indicators in Kenya’s dry-land agroecosystems. Soil and Tillage Research, 227. [CrossRef]

- Parras-Alcántara, L., & Lozano-García, B. (2014). Conventional tillage versus organic farming in relation to soil organic carbon stock in olive groves in Mediterranean rangelands (southern Spain). Solid Earth, 5(1), 299–311. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B. R., Udawatta, R. P., & Anderson, S. H. (2011). Agroforestry and grass buffer effects on soil quality parameters for grazed pasture and row-crop systems. Applied Soil Ecology, 48(2), 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Peech, N. (1965). Hydrogen ion activity. P 914-926. Methods of Soil Analysis. American Society of Agronomy. Madison. Wisconsin.

- Primo, A. A., Araújo Neto, R. A. de, Zeferino, L. B., Fernandes, F. É. P., Araújo Filho, J. A. de, Cerri, C. E. P., & Oliveira, T. S. de. (2023). Slash and burn management and permanent or rotation agroforestry systems: A comparative study for C sequestration by century model simulation. Journal of Environmental Management, 336. [CrossRef]

- Reis dos Santos Bastos, T., Anjos Bittencourt Barreto-Garcia, P., de Carvalho Mendes, I., Henrique Marques Monroe, P., & Ferreira de Carvalho, F. (2023). Response of soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity in coffee-based agroforestry systems in a high-altitude tropical climate region of Brazil. Catena, 230. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, S. G. (1970). The gravimetric method of soil moisture determination Part IA study of equipment, and methodological problems. Journal of Hydrology, 11(3), 258–273.

- Rhoades, J. D. (1996). Salinity: Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods, 5, 417–435.

- Rivest, D., Lorente, M., Olivier, A., & Messier, C. (2013). Soil biochemical properties and microbial resilience in agroforestry systems: Effects on wheat growth under controlled drought and flooding conditions. Science of the Total Environment, 463–464, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L., Suárez, J. C., Rodriguez, W., Artunduaga, K. J., & Lavelle, P. (2021). Agroforestry systems impact soil macroaggregation and enhance carbon storage in Colombian deforested Amazonia. Geoderma, 384. [CrossRef]

- Saikhammoon, R., Sungkaew, S., Thinkampaeng, S., Phumphuang, W., Kamyo, T., & Marod, D. (2023). Forest Restoration in an Abandoned Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest in the Mae Klong Watershed, Western Thailand: 10.32526/ennrj/21/20230121. Environment and Natural Resources Journal, 21(5), 443–457.

- Singh, A., Choudhury, B. U., Balusamy, A., & Sahoo, U. K. (2024). Restoring the inventory of biomass and soil carbon in abandoned croplands: An agroforestry system approach in India’s eastern Himalayas. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 362. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A., Hosseini, S. M., Massah Bavani, A. R., Jafari, M., & Francaviglia, R. (2019). Influence of land use and land cover change on soil organic carbon and microbial activity in the forests of northern Iran. Catena, 177, 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Souza, H. N. de, de Goede, R. G. M., Brussaard, L., Cardoso, I. M., Duarte, E. M. G., Fernandes, R. B. A., Gomes, L. C., & Pulleman, M. M. (2012). Protective shade, tree diversity and soil properties in coffee agroforestry systems in the Atlantic Rainforest biome. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 146(1), 179–196. [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, J. P., J.J.A. Bianchi, F., Luiz Locatelli, J., Rizzo, R., Eduarda Bispo de Resende, M., Ramos Ballester, M. V., Cerri, C. E. P., Bernardi, A. C. C., & Creamer, R. E. (2023). Increasing complexity of agroforestry systems benefits nutrient cycling and mineral-associated organic carbon storage, in south-eastern Brazil. Geoderma, 440. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A., Zhang, Y., Huang, J., Hu, J., Paustian, K., & Hartemink, A. E. (2024). Rates of soil organic carbon change in cultivated and afforested sandy soils. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 360. [CrossRef]

- Tippayachan, H. (2006). The Determination of Cabon Loss by Soil Erosion and Sediment Transport Processes in Mea Thang Watershed, Rong Kwang District, Phrae Province. Mahidol University.

- Tumwebaze, S. B., & Byakagaba, P. (2016). Soil organic carbon stocks under coffee agroforestry systems and coffee monoculture in Uganda. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 216, 188–193. [CrossRef]

- Usman, A. R. A., Kuzyakov, Y., & Stahr, K. (2004). Dynamics of organic C mineralization and the mobile fraction of heavy metals in a calcareous soil incubated with organic wastes. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 158, 401–418.

- Vance, E. D., Brookes, P. C., & Jenkinson, D. S. (1987). An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 19(6), 703–707.

- Verma, T., Bhardwaj, D. R., Sharma, U., Sharma, P., Kumar, D., & Kumar, A. (2023). Agroforestry systems in the mid-hills of the north-western Himalaya: A sustainable pathway to improved soil health and climate resilience. Journal of Environmental Management, 348. [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte, A. B., Soria, R., Rodríguez-Berbel, N., Zema, D. A., Lucas-Borja, M. E., Ortega, R., & Miralles, I. (2024). Short-term evaluation of soil physical, chemical and biochemical properties in an abandoned cropland treated with different soil organic amendments under semiarid conditions. Journal of Environmental Management, 349. [CrossRef]

- Wani, O. A., Kumar, S. S., Hussain, N., Wani, A. I. A., Babu, S., Alam, P., Rashid, M., Popescu, S. M., & Mansoor, S. (2023). Multi-scale processes influencing global carbon storage and land-carbon-climate nexus: A critical review. In Pedosphere (Vol. 33, Issue 2, pp. 250–267). Soil Science Society of China. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Zeng, H., Zhao, F., Chen, C., Liu, W., Yang, B., & Zhang, W. (2020). Recognizing the role of plant species composition in the modification of soil nutrients and water in rubber agroforestry systems. Science of the Total Environment, 723. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C., Li, P., & Feng, Z. (2023). Agricultural expansion and forest retreat in Mainland Southeast Asia since the late 1980s. Land Degradation & Development, 34(17), 5606–5621.

- Zhou, S., Li, P., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Factors influencing and changes in the organic carbon pattern on slope surfaces induced by soil erosion. Soil and Tillage Research, 238. [CrossRef]

- Zipei, L., Qi, S., Ndzana, G. M., Lijun, C., Yuqi, C., sheng, L., & Lichao, W. (2024). Dynamic of Organic Matter, Nutrient Cycling, and PH in Soil Aggregate Particle Sizes Under Long-Term Cultivation of Camellia Oleifera. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 24(2), 2599–2606. [CrossRef]

|

Land use × Depth |

Physical characteristics | Chemical characteristics | ||||||||||||

| BD | Sand | Silt | Clay | pH | EC | C | N | C/N | Available | Exchangeable | ||||

| P | K | Ca | Mg | |||||||||||

| g cm-3 | % | % | % | μS cm-1 | % | % | mg kg-1 | mg kg-1 | mg kg-1 | mg kg-1 | ||||

| FR 0 – 20 | 1.11 | 44.67 | 27.33 | 28.00 | 5.76 | 49.82 | 2.29 | 0.19 | 12.68 | 1.92 | 461 | 760 | 26.61 | |

| FR 20 – 40 | 1.15 | 50.67 | 24.67 | 24.67 | 5.73 | 34.31 | 1.39 | 0.13 | 10.79 | 1.22 | 327 | 616 | 20.67 | |

| FR 40 – 60 | 1.23 | 36.00 | 16.67 | 47.33 | 5.39 | 27.55 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 11.26 | 0.49 | 301 | 520 | 17.05 | |

| CA 0 – 20 | 1.30 | 40.00 | 28.67 | 31.33 | 5.95 | 64.73 | 1.76 | 0.15 | 12.15 | 43.14 | 251 | 1116 | 10.59 | |

| CA 20 – 40 | 1.33 | 50.00 | 26.00 | 24.00 | 5.95 | 44.63 | 0.99 | 0.09 | 10.87 | 20.73 | 274 | 801 | 7.03 | |

| CA 40 – 60 | 1.31 | 46.00 | 22.67 | 31.33 | 6.07 | 45.18 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 11.63 | 4.67 | 255 | 779 | 7.13 | |

| CF 0 – 20 | 1.12 | 41.33 | 20.67 | 38.00 | 6.12 | 76.38 | 2.68 | 0.25 | 11.36 | 5.97 | 380 | 1889 | 37.91 | |

| CF 20 – 40 | 1.24 | 44.00 | 26.00 | 30.00 | 6.22 | 52.62 | 1.36 | 0.13 | 10.29 | 1.55 | 341 | 1293 | 28.56 | |

| CF 40 – 60 | 1.27 | 44.00 | 21.33 | 34.67 | 6.21 | 41.82 | 0.97 | 0.09 | 10.52 | 1.00 | 385 | 1128 | 25.85 | |

| CP 0 – 20 | 1.22 | 50.00 | 28.00 | 22.00 | 5.92 | 55.95 | 1.81 | 0.16 | 11.68 | 8.93 | 417 | 1430 | 15.29 | |

| CP 20 – 40 | 1.28 | 38.67 | 26.67 | 34.67 | 5.92 | 43.99 | 1.12 | 0.10 | 12.05 | 4.45 | 338 | 1151 | 8.83 | |

| CP 40 – 60 | 1.32 | 43.33 | 28.67 | 35.33 | 5.84 | 41.23 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 10.25 | 0.88 | 319 | 1031 | 6.63 | |

| P values | 0.013 | 0 | 0.112 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.530 | 0 | 0 | 0.890 | 0 | 0.358 | 0.094 | 0.403 | |

| CV | * | 6.24 | 16.14 | 9.14 | 7.66 | 30.37 | 19.43 | 23.88 | 27.72 | 82.71 | 37.75 | 26.07 | 31.24 | |

| Depth (cm) |

Carbon Stock (t C ha-1) |

Carbon Stock (t C ha-1) |

Δ Carbon Stock (t C ha-1) |

Change Loss |

% Change |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF | CA | |||||

| 0 – 20 | 51.03 ± 2.61 | 45.83 ± 2.70 | -5.20 ± 1.14 | - | 10.18 | 0.002 |

| 20 – 40 | 32.06 ± 2.15 | 26.44 ± 2.97 | -5.62 ± 3.60 | - | 17.53 | 0.157 |

| 40 – 60 | 22.59 ± 1.27 | 23.83 ± 2.55 | 1.24 ± 3.04 | + | 5.48 | 0.694 |

| 0 – 60 | 105.68 ± 4.49 | 96.10 ± 5.56 | -9.58 ± 4.64 | - | 9.06 | 0.073 |

| NF | CF | |||||

| 0 – 20 | 51.03 ± 2.61 | 59.78 ± 2.72 | 8.75 ± 4.10 | + | 17.15 | 0.065 |

| 20 – 40 | 32.06 ± 2.15 | 33.93 ± 2.50 | 1.87 ± 1.37 | + | 5.84 | 0.208 |

| 40 – 60 | 22.59 ± 1.27 | 24.76 ± 1.50 | 2.16 ± 1.37 | + | 9.57 | 0.153 |

| 0 – 60 | 105.68 ± 4.49 | 118.47 ± 3.73 | 12.79 ± 3.15 | + | 12.10 | 0.004 |

| NF | CP | |||||

| 0 – 20 | 51.03 ± 2.61 | 44.13 ± 1.33 | -6.90 ± 2.68 | - | 13.51 | 0.033 |

| 20 – 40 | 32.06 ± 2.15 | 28.88 ± 3.56 | -3.18 ± 2.89 | - | 9.92 | 0.304 |

| 40 – 60 | 22.59 ± 1.27 | 20.11 ± 1.62 | -2.49 ± 2.26 | - | 11.02 | 0.304 |

| 0 – 60 | 105.68 ± 4.49 | 93.12 ± 5.25 | -12.56 ± 5.09 | - | 11.89 | 0.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).