Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Biopolymers tend to form fibrils that self-assemble into open network structures. While permanently crosslinked flexible polymers are relatively well understood, structure--property relationships of open networks and pseudo-gels formed by bundles of biopolymers are still controversial. Here we employ a generic coarse-grained bead-spring chain model incorporating semiflexibility and cohesive nonbonded interactions, that forms physical instead of chemical crosslinks. For flexible chains, the cohesive forces lead to the formation of a droplet phase while, at the same concentration, stiffer chains form bundles that self-assemble into percolated networks. From comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations we find that the reversible crosslinks allow for permanent relaxation processes. However, the associated reorganization of the filamentous network is severely hindered, leading to aging of its topology. Based on morphometric analyses, the ultra-slow coarsening in these systems is proven to be self-similar, which implies a number of scaling relations between structural quantities as the networks age. The percolated structures are characterized by different dynamic regimes of slow, anomalous diffusion with highly non-Gaussian displacements. Relaxation dynamics is found to become extremely slow already on moderate length scales and further slowing down as coarsening proceeds. Using a minimal model supported by observations on filament rupture and rearrangement, our study helps to shed light on various interrelated structural and dynamical aspects of coarsening nonergodic systems relevant for fibrous networks, pseudo-gels, and physical fibrillar gels.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

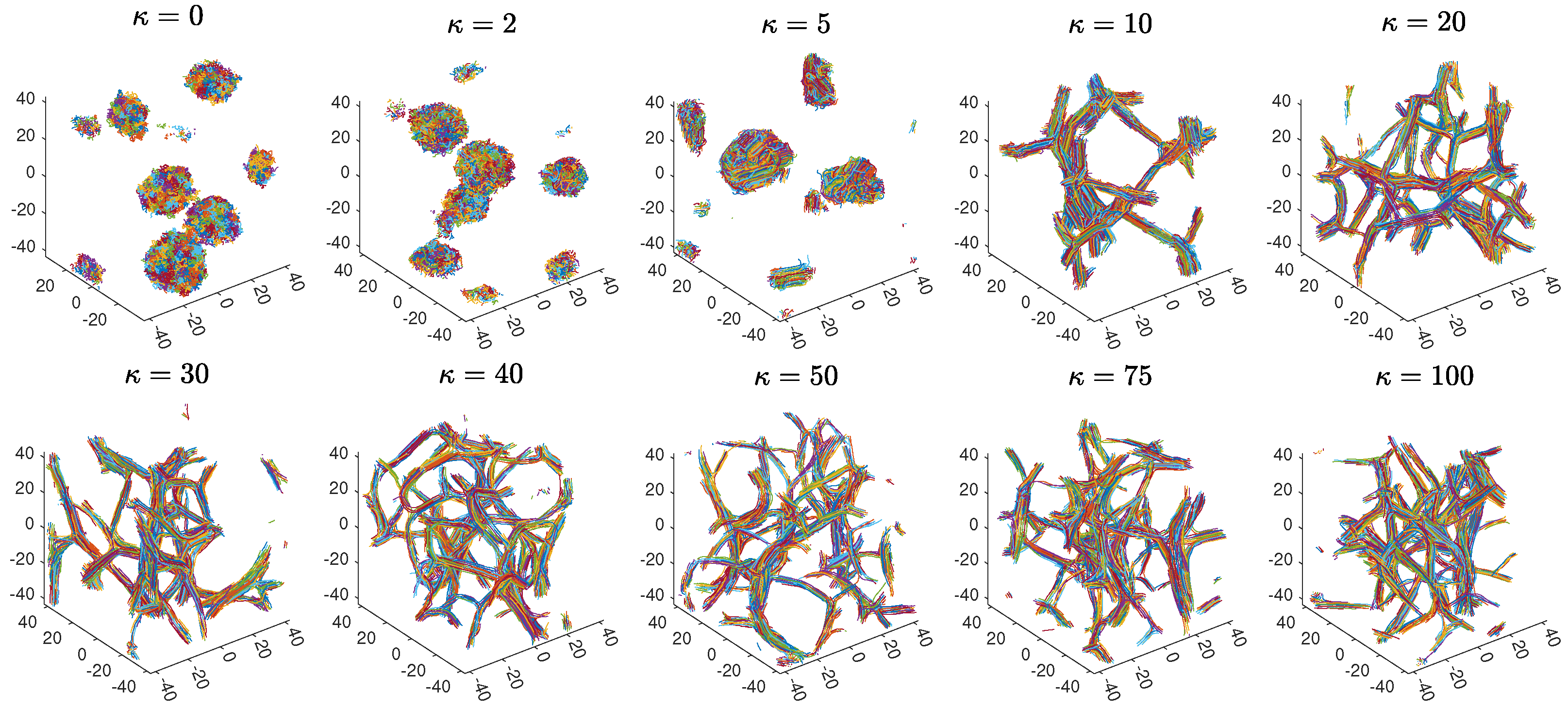

2.1. Initial Observations

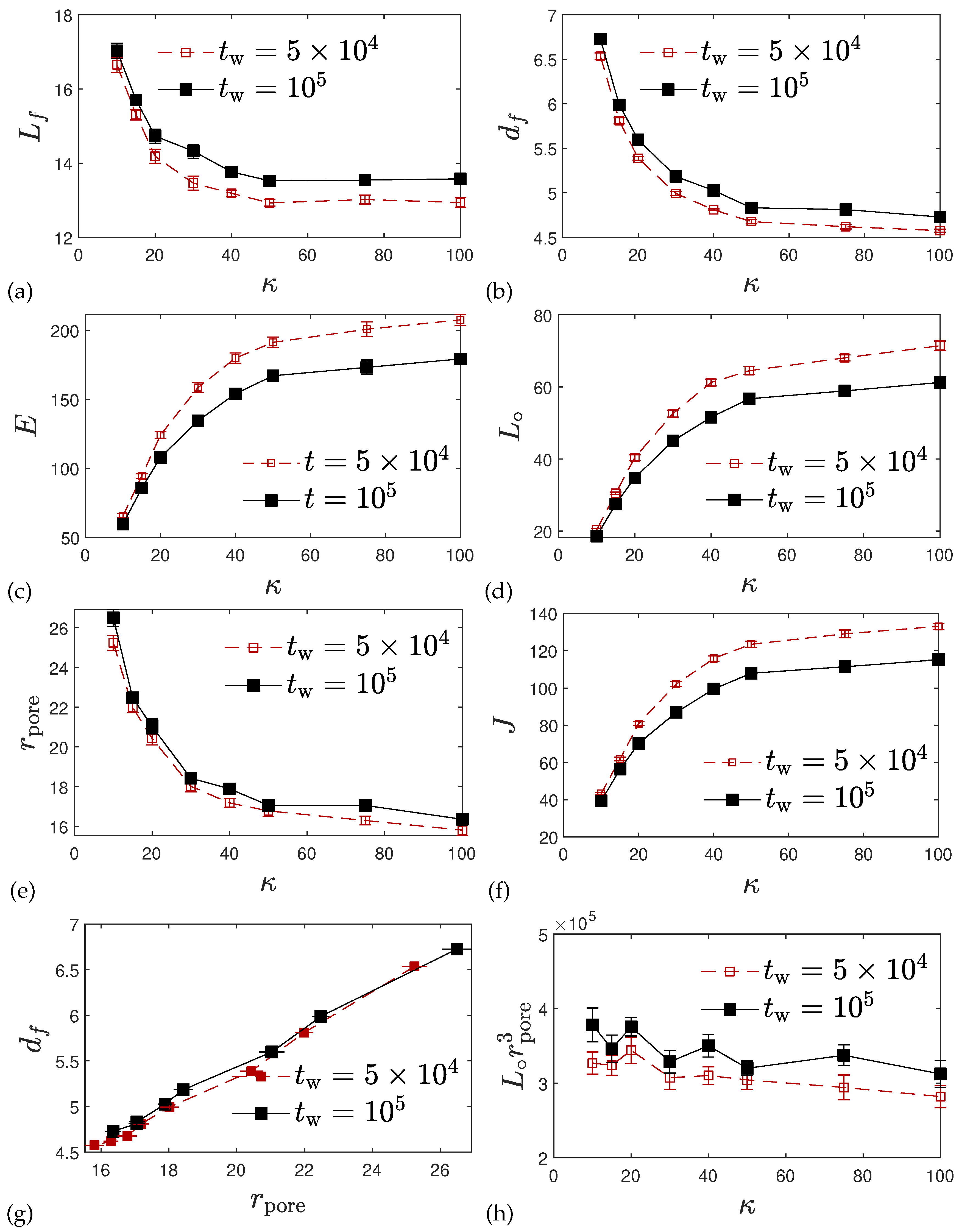

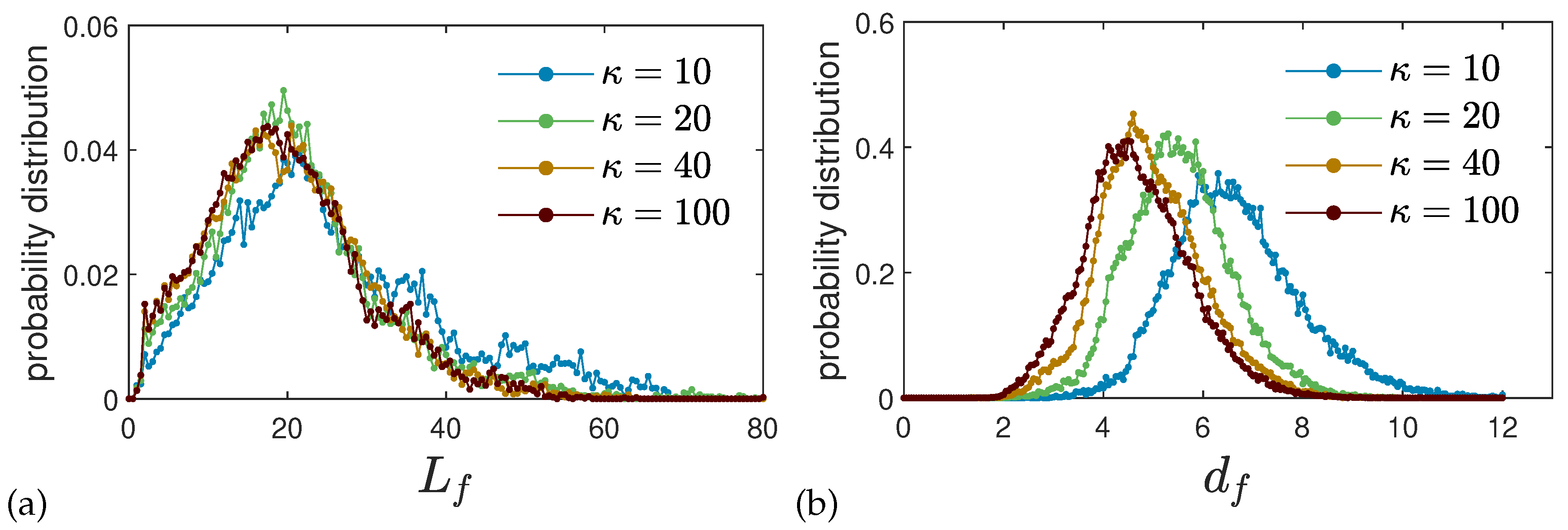

2.2. Structure Analysis and Static Properties

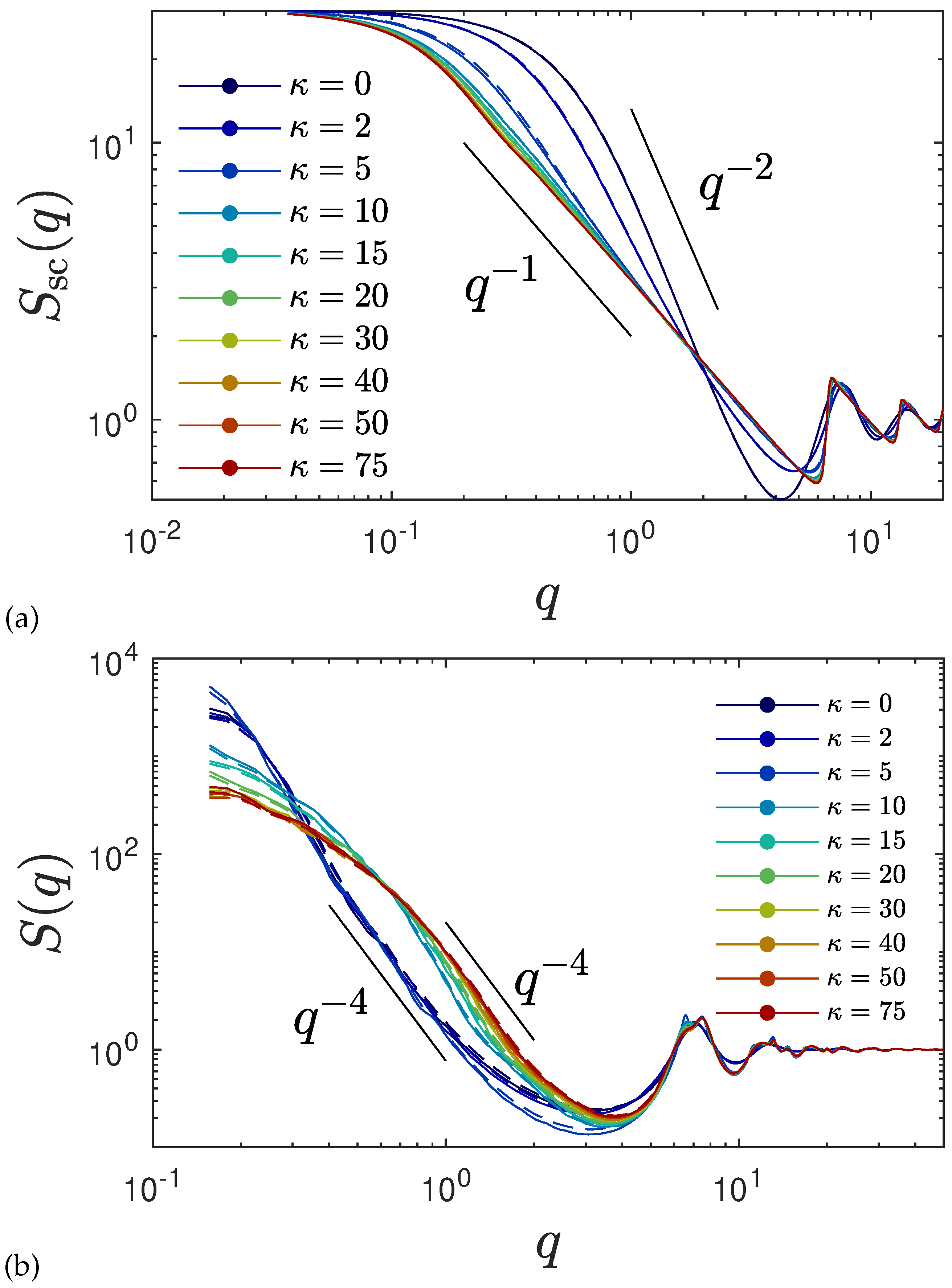

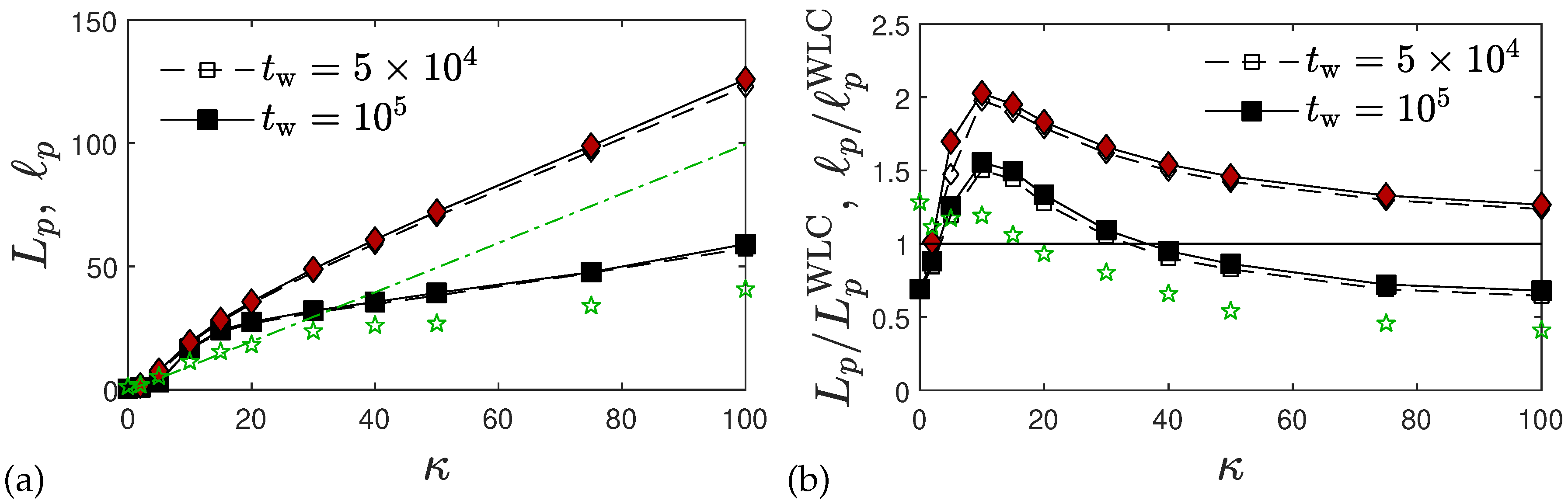

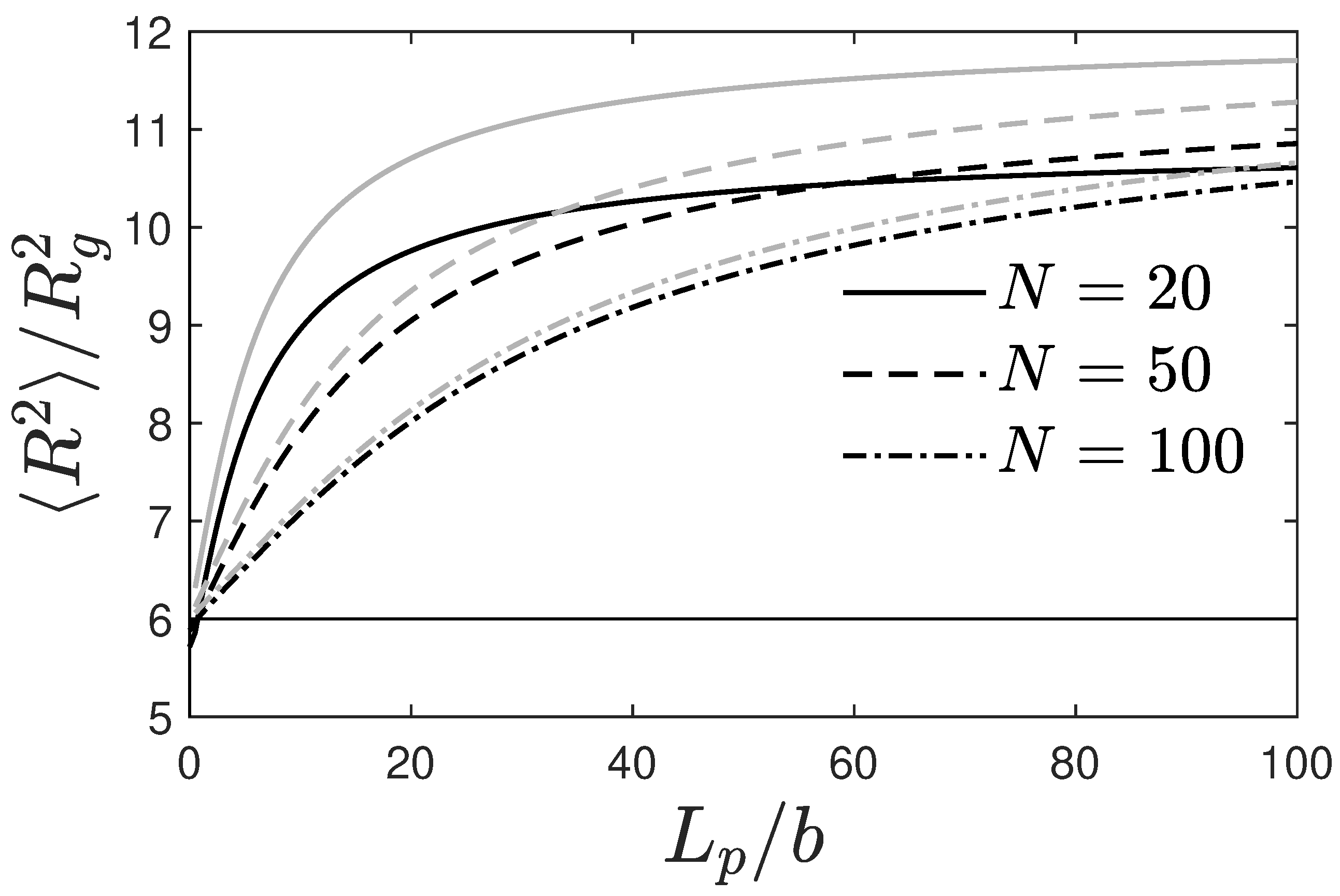

2.2.1. Single Chain Structure Factors and Persistence Lengths

2.2.2. Structure Factor

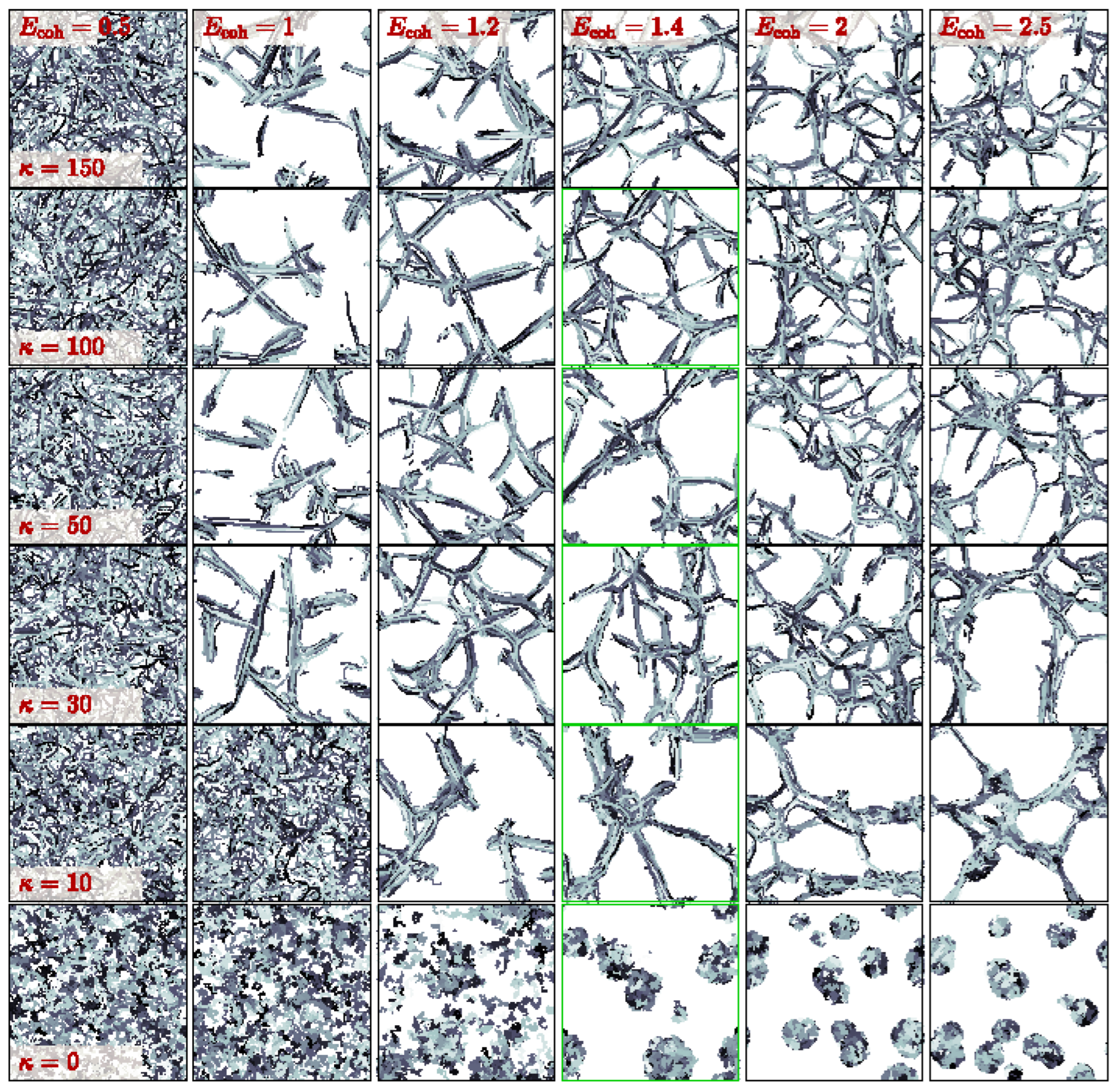

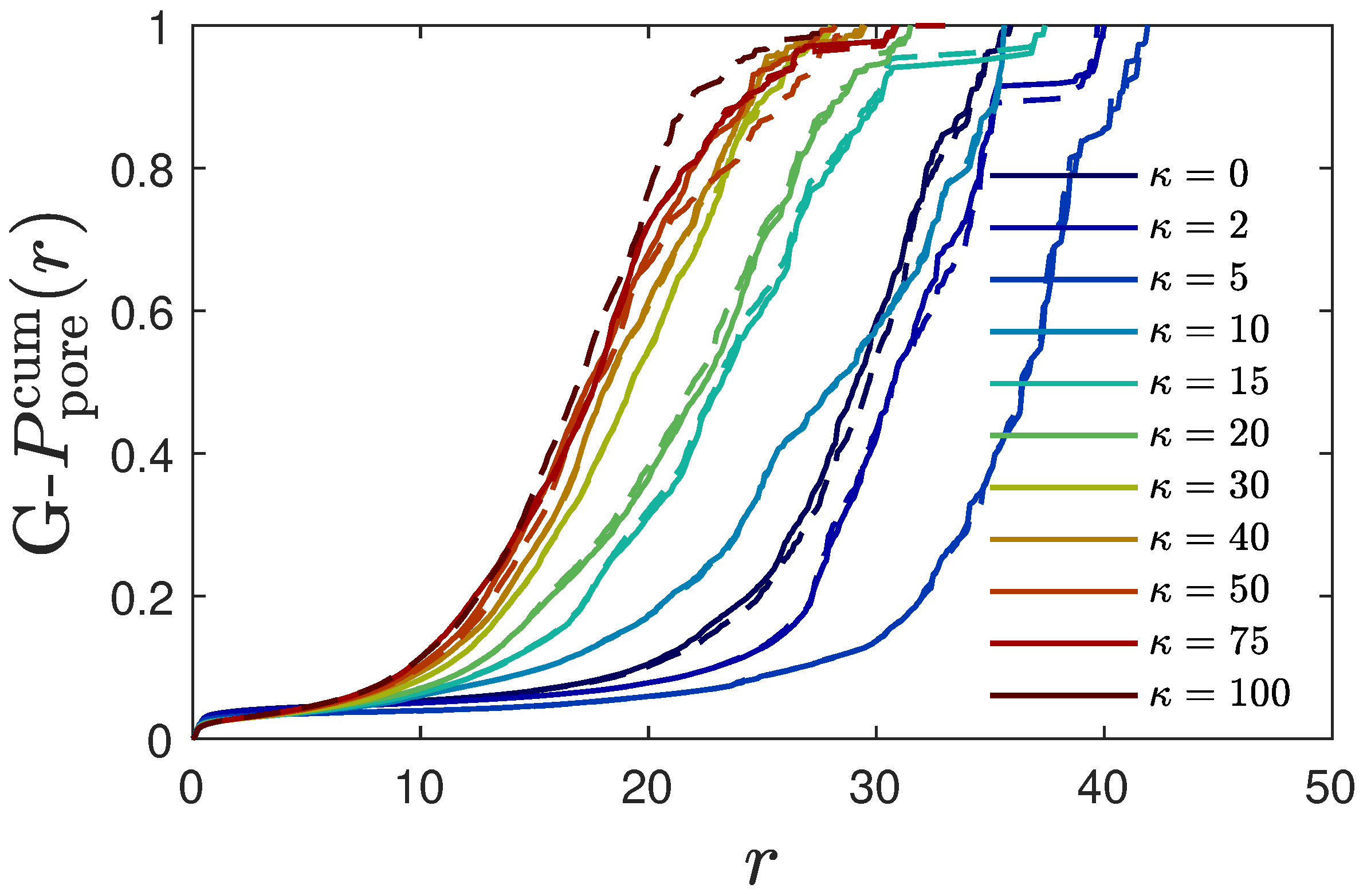

2.2.3. Real Space Structural Analysis

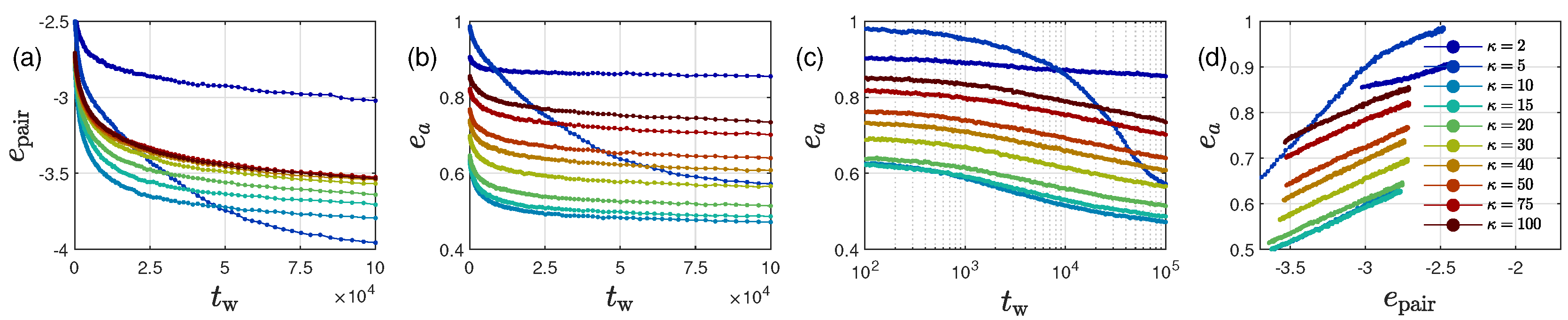

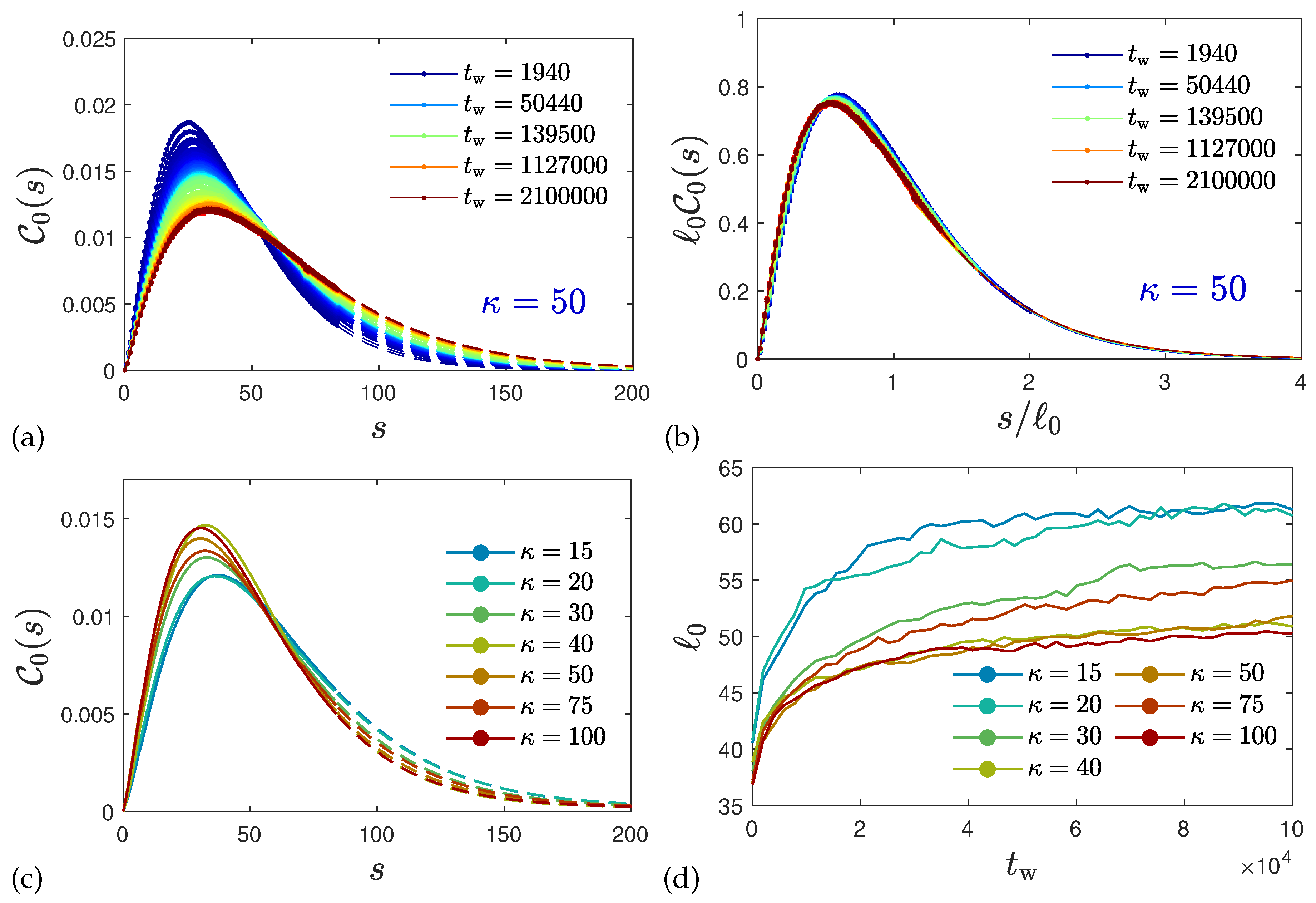

2.3. Ultra-Slow Coarsening and Self-Similarity

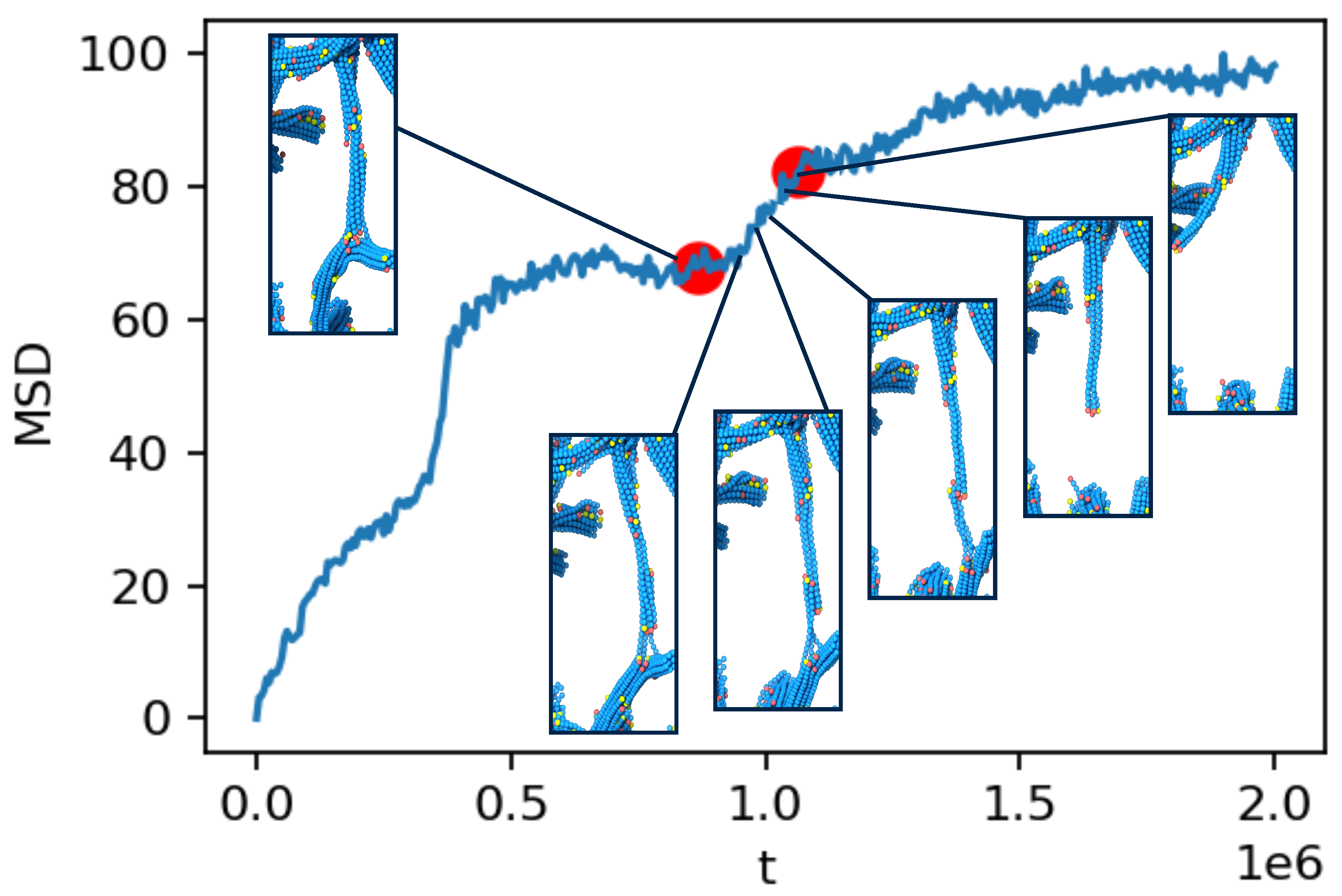

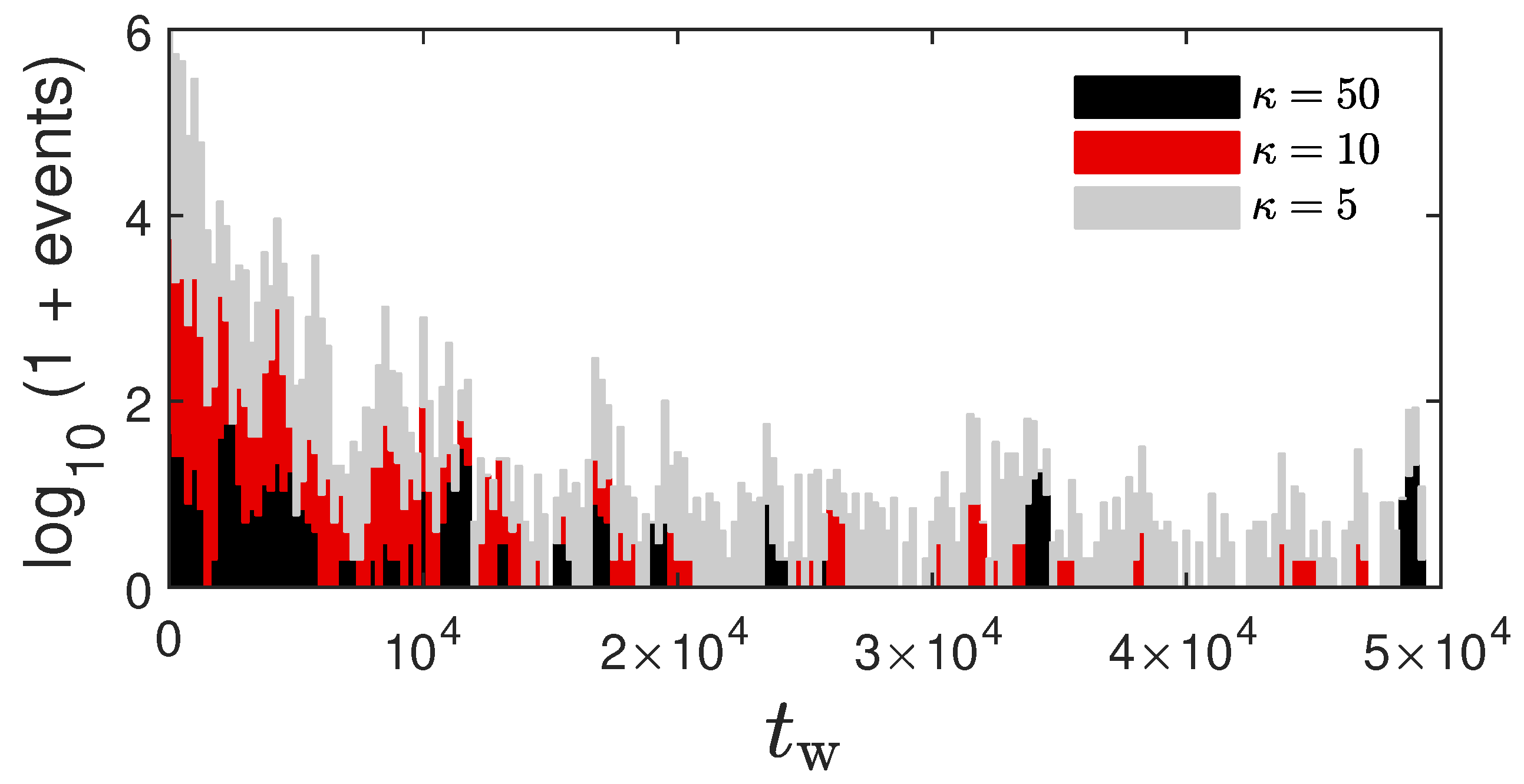

2.4. Coarsening Mechanism

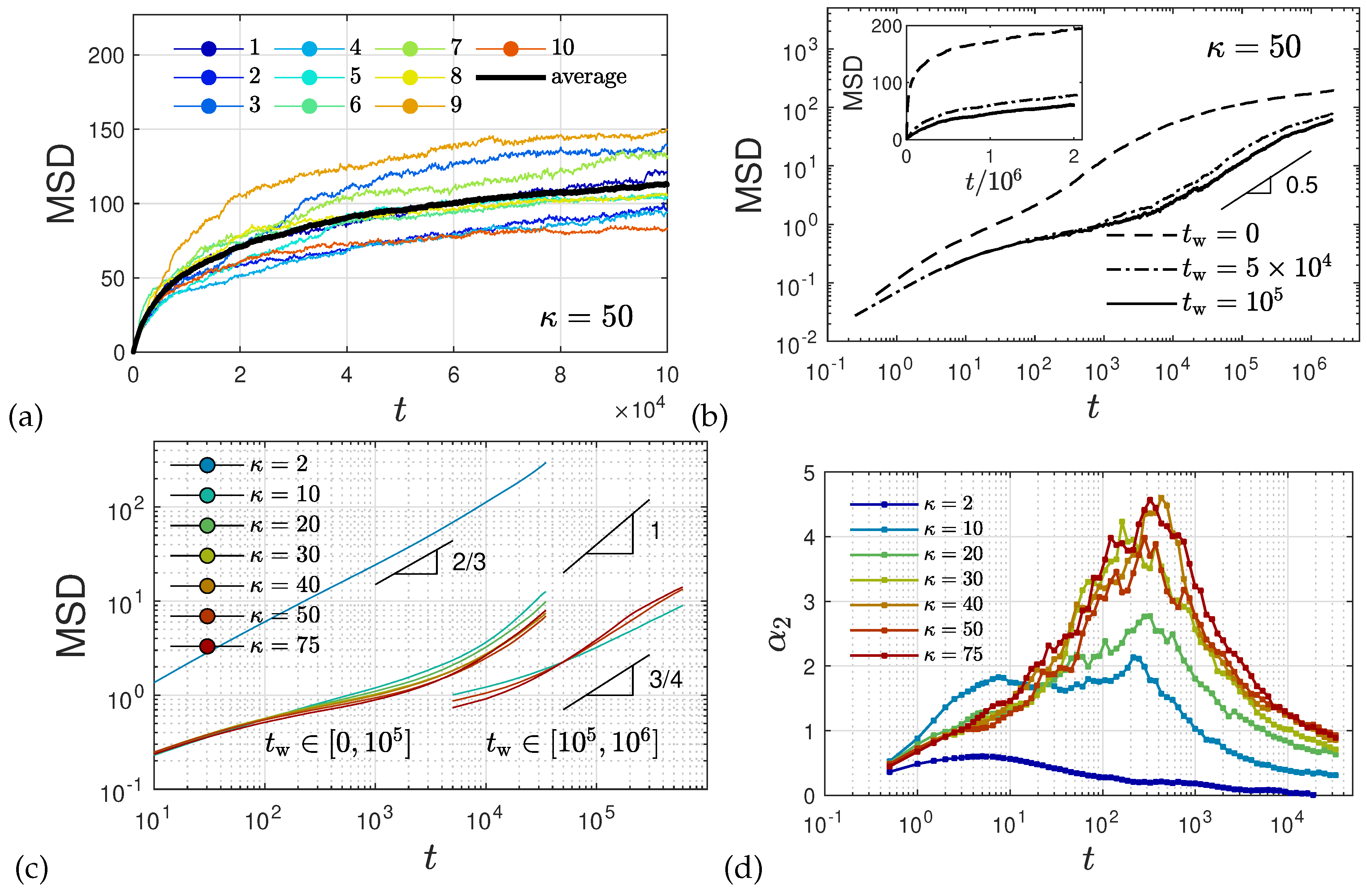

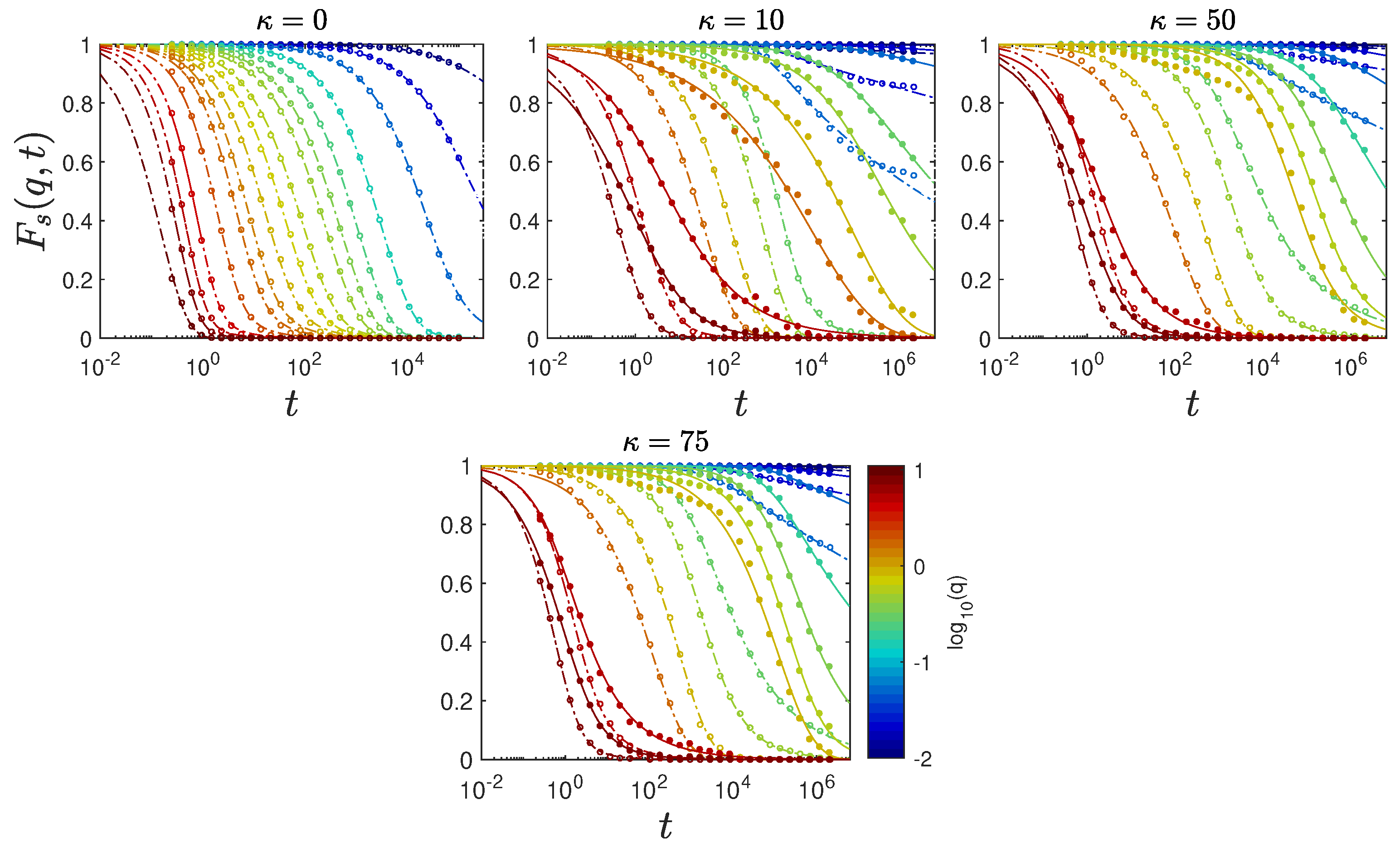

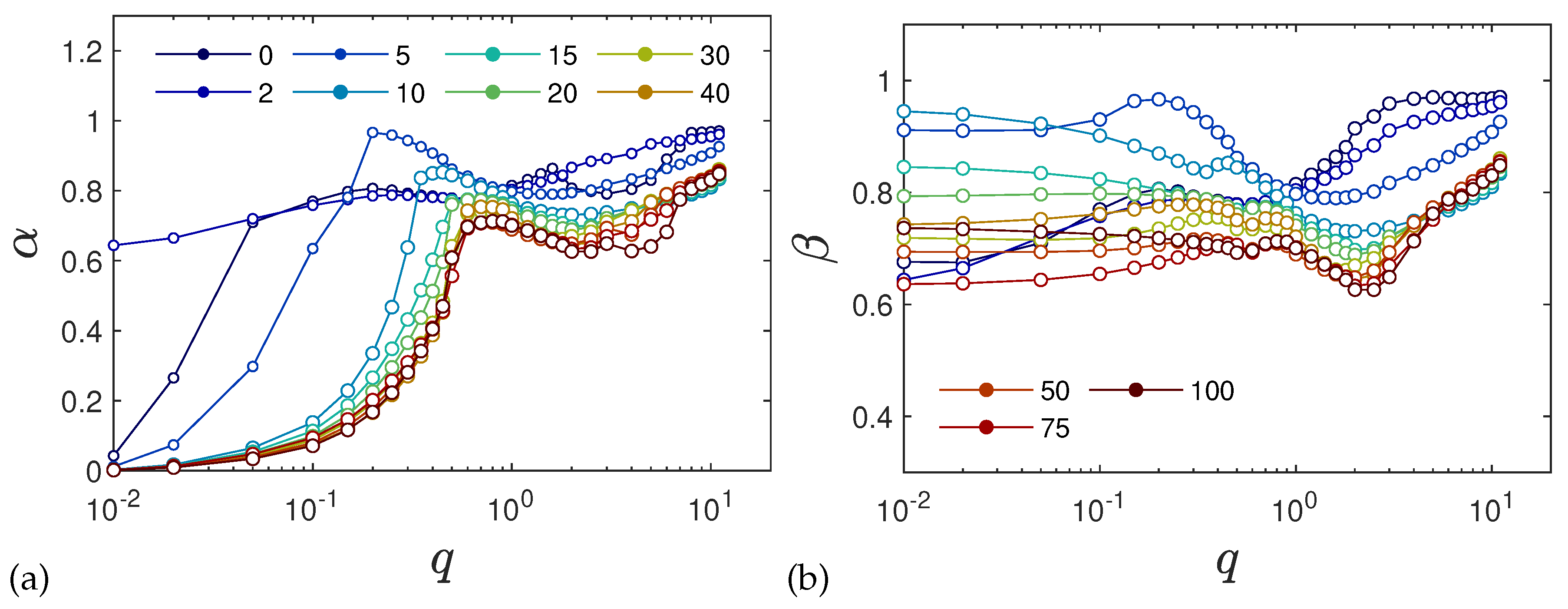

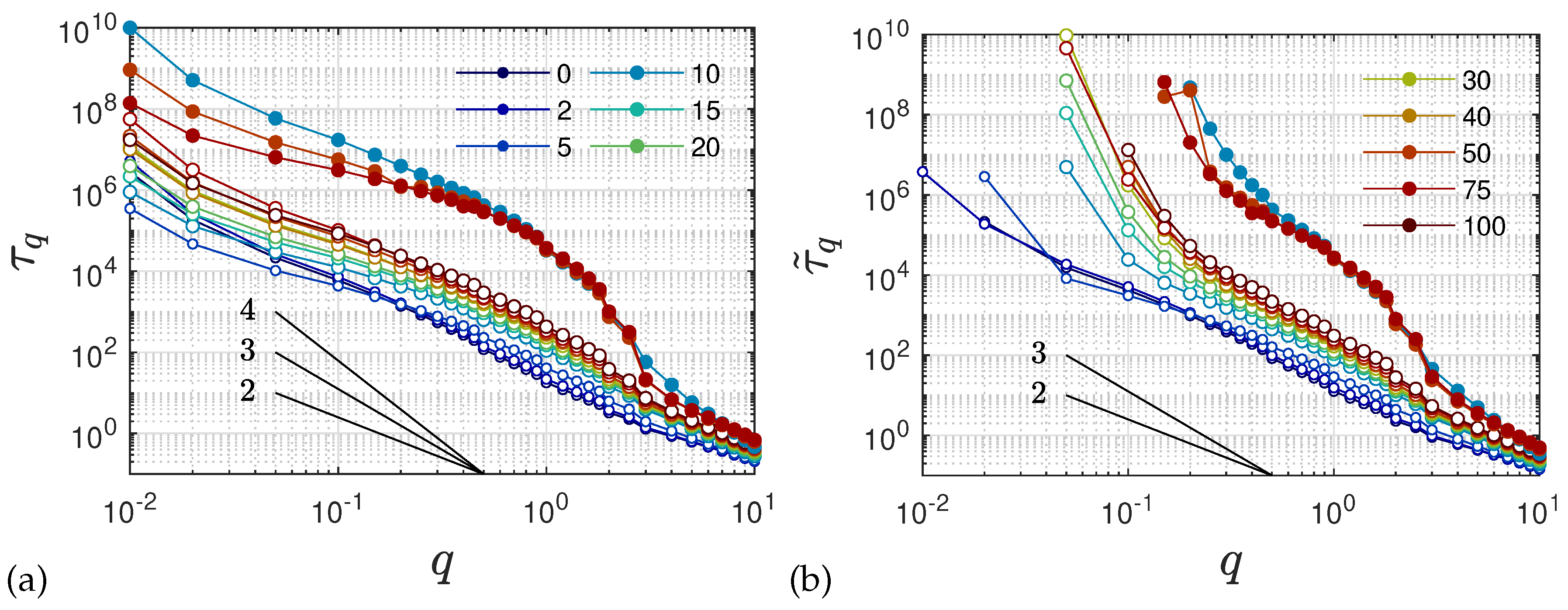

2.5. Anomalous Diffusion and Relaxational Dynamics

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

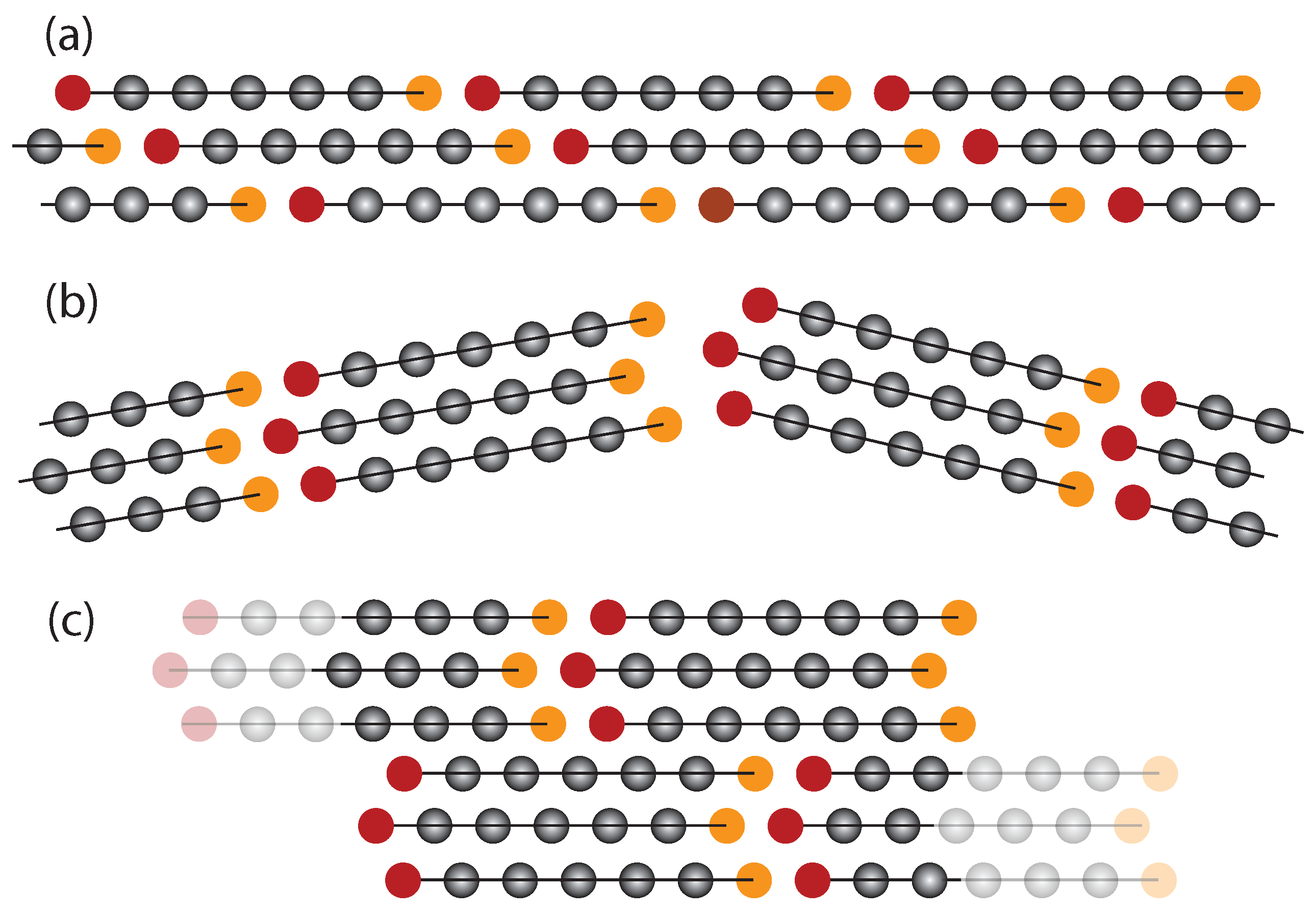

4.1. Coarse-Grained Simulation Model

4.1.1. Model Equations and Parameters

4.1.2. Preparation of Model Systems

4.2. Static Structure Factors

4.3. Effective Persistence Lengths

4.4. Intermediate Scattering Function

4.5. Network Analysis Algorithms

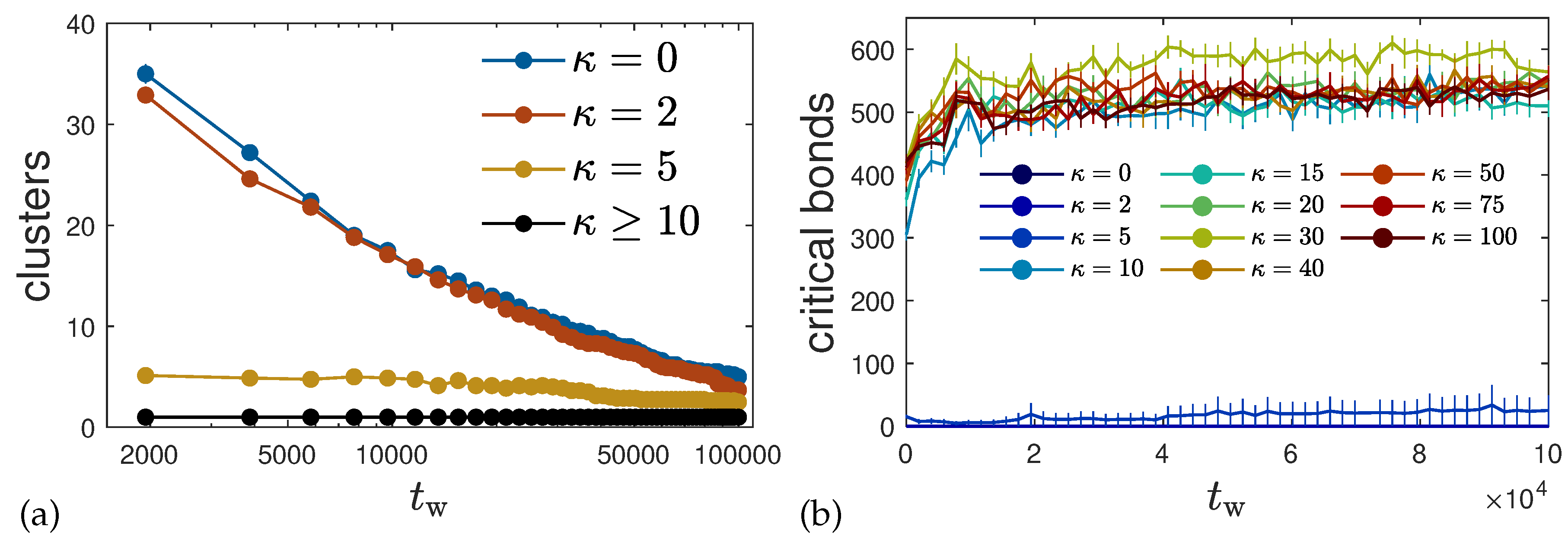

4.5.1. Clusters and Critical Bonds

4.5.2. Skeleton

4.5.3. Edges, Loops, and Functionalities

4.5.4. Filament Diameters and Volumes

4.5.5. Pore Size Distribution

4.5.6. Chord Lengths and Polymer Surface Areas

4.6. Self-Similar Coarsening

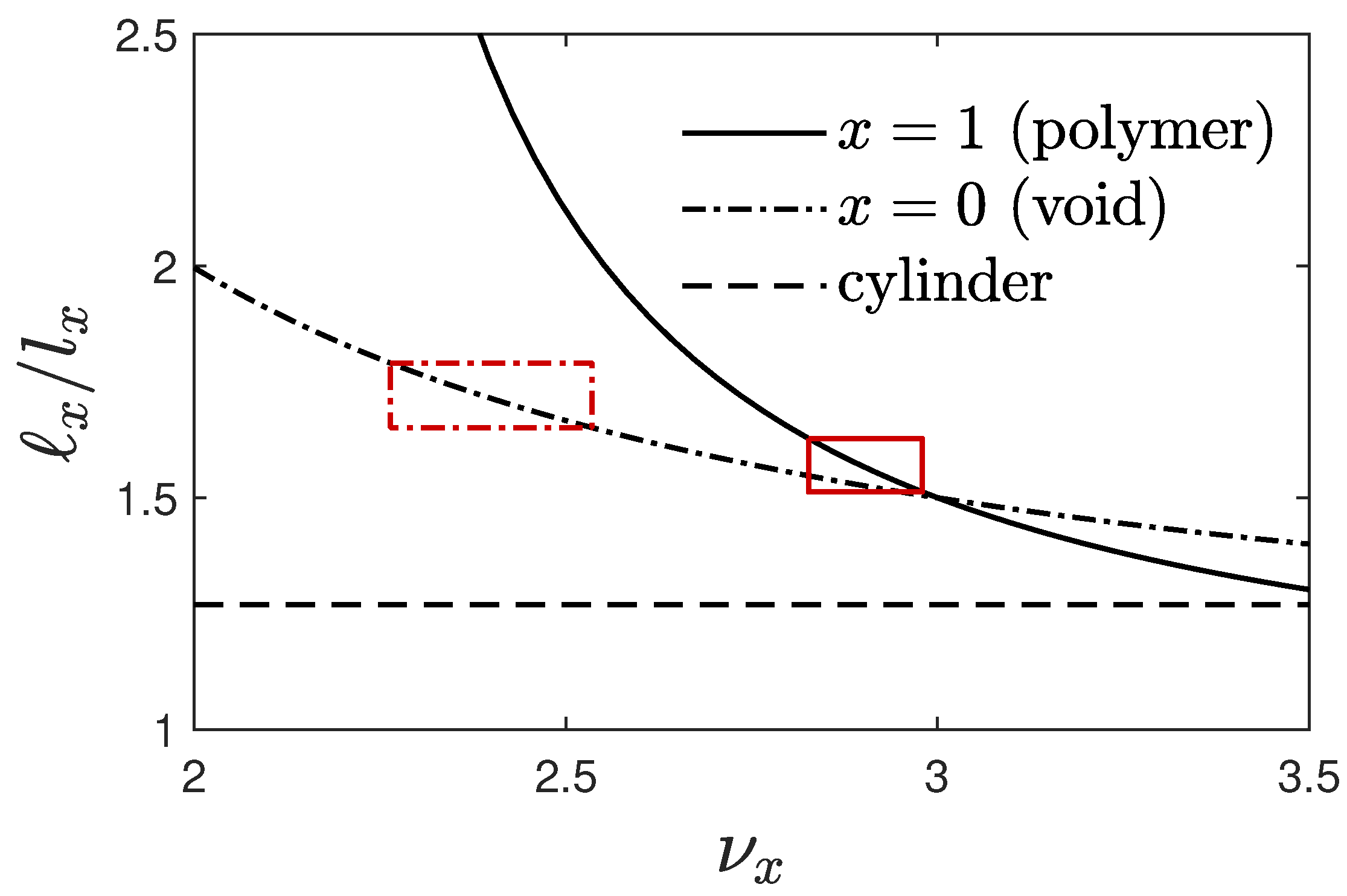

4.6.1. Minimal Model

4.6.2. Logarithmic Fits

4.6.3. Self-Similar and

4.6.4. Scaling Relations During Coarsening

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Usuelli, M.; Cao, Y.; Bagnani, M.; Handschin, S.; Nystrom, G.; Mezzenga, R. Probing the structure of filamentous nonergodic gels by dynamic light scattering. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 5950–5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnauß, J.; Händler, T.; Käs, J. Semiflexible Biopolymers in Bundled Arrangements. Polymers 2016, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohyama, K.; Miller, W.G. Network structure in gels of rod-like polypeptides. Nature 1981, 289, 813–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augst, A.D.; Kong, H.J.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate Hydrogels as Biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 2006, 6, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, S.R.; Douglas, J.F. The conundrum of gel formation by molecular nanofibers, wormlike micelles, and filamentous proteins: gelation without cross-links? Soft Matter 2012, 8, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, A.S.G.; Vahabi, M.; Licup, A.J.; Sharma, A.; Galie, P.A.; MacKintosh, F.C.; Janmey, P.A. Uncoupling shear and uniaxial elastic moduli of semiflexible biopolymer networks: compression-softening and stretch-stiffening. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcari, M.; Axelrod, R.; Adamcik, J.; Handschin, S.; Sánchez-Ferrer, A.; Mezzenga, R.; Nyström, G. Structure–property relationships of cellulose nanofibril hydro- and aerogels and their building blocks. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 11638–11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picu, R.C. Mechanics of random fiber networks—a review. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Terentjev, E. Theory of Semiflexible Filaments and Networks. Polymers 2017, 9, 52–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilman, A.G.; Safran, S.A. Thermodynamics and structure of self-assembled networks. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 051107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, M.L.; Liberman, L.; Ertem, S.P.; Edmund, J.; Bates, F.S.; Lodge, T.P. Methyl cellulose solutions and gels: fibril formation and gelation properties. Progr. Polym. Sci. 2021, 112, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, M.; Tanaka, H. Power-law coarsening in network-forming phase separation governed by mechanical relaxation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Tateno, M.; Tanaka, H. Mechanical slowing down of network-forming phase separation of polymer solutions. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 18025–18036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, V.; Kumar, S.K. Gelation in semiflexible polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 174902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Lara, F.; Douglas, J. Fiber Network Formation in Semi-Flexible Polymer Solutions: An Exploratory Computational Study. Gels 2018, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupper, N.; Rabin, Y.; Rosenbluh, M. Multiple Stages in the Aging of a Physical Polymer Gel. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3983–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, P.; Berthier, L. Ultra-long-range dynamic correlations in a microscopic model for aging gels. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 060601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, M.; Giacomazza, D.; Newman, J.; Martorana, V.; San Biagio, P.L. Amyloid Gels: Precocious Appearance of Elastic Properties during the Formation of an Insulin Fibrillar Network. Langmuir 2010, 26, 1424–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore, R.; Siviello, C.; Larobina, D. Elastic and Dynamic Heterogeneity in Aging Alginate Gels. Polymers 2021, 13, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broedersz, C.P.; MacKintosh, F.C. Modeling semiflexible polymer networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 995–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, J.R.; McAllister, J.W.; Wasbrough, M.; Sammler, R.L.; Bates, F.S.; Lodge, T.P. Fibrillar Structure in Aqueous Methylcellulose Solutions and Gels. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 9760–9771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, S.; Schmidt, P.W.; Bates, F.S.; Lodge, T.P. Effect of Poly(ethylene glycol) Grafting Density on Methylcellulose Fibril Formation. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 9413–9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ramesh, R.; Jha, P.K.; Larson, R.G. A Systematic Coarse-Grained Model for Methylcellulose Polymers: Spontaneous Ring Formation at Elevated Temperature. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 1490–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Collins, A.M.; Jayaraman, A. Understanding Self-Assembly and Molecular Packing in Methylcellulose Aqueous Solutions Using Multiscale Modeling and Simulations. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, P.W.; Morozova, S.; Owens, P.M.; Adden, R.; Li, Y.; Bates, F.S.; Lodge, T.P. Molecular Weight Dependence of Methylcellulose Fibrillar Networks. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7767–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.W.; Morozova, S.; Ertem, S.P.; Coughlin, M.L.; Davidovich, I.; Talmon, Y.; Reineke, T.M.; Bates, F.S.; Lodge, T.P. Internal Structure of Methylcellulose Fibrils. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.L.P.; Behrens, M.A.; Pedersen, J.S.; Erlacher, K.; Otzen, D.; Pedersen, J.S. A SAXS study of glucagon fibrillation. J. Molec. Biol. 2009, 387, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, J.S.; Schurtenberger, P. Scattering functions of semiflexible polymers with and without excluded volume effects. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 7602–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Zhang, X. Scattering and Gaussian Fluctuation Theory for Semiflexible Polymers. Polymers 2016, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkarderis, L.; Van De Ven, T.G.M. Mesh size analysis of cellulose nanofibril hydrogels using solute exclusion and PFG-NMR spectroscopy. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 9201–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, V.; Raccosta, S.; Giacomazza, D.; Ditta, L.A.; Noto, R.; San Biagio, P.L.; Manno, M. Amyloid jams: Mechanical and dynamical properties of an amyloid fibrillar network. Biophys. Chem. 2019, 253, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Yao, H.; Olsen, B.D. Bridging dynamic regimes of segmental relaxation and center-of-mass diffusion in associative protein hydrogels. Physical Review Research 2020, 2, 043369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehandzhiyski, A.Y.; Zozoulenko, I. A Review of Cellulose Coarse-Grained Models and Their Applications. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strodel, B. Amyloid aggregation simulations: challenges, advances and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 67, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, K.; Grest, G.S. Dynamics of entangled linear polymer melts - A molecular dynamics simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5057–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M.; Ben-Shaul, A. On the presence of loops in linear self-assembling systems. Cah. Rheol. 1997, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Micro/mesoscopic approaches to the ring formation in linear wormlike micellar systems. Macromol. Symp. 1998, 133, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, R.; Kolb, A.; Müller-Plathe, F. Local chain ordering inamorphous polymer melts: Influence of chain stiffness. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Kröger, M.; Hecht, I.; Rabin, Y. Filamentous networks in phase-separating two-dimensional gels. Europhys. Lett. 2007, 77, 58007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midya, J.; Egorov, S.A.; Binder, K.; Nikoubashman, A. Phase behavior of flexible and semiflexible polymers in solvents of varying quality. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 034902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierenberg, J.; Marenz, M.; Janke, W. Dilute Semiflexible Polymers with Attraction: Collapse, Folding and Aggregation. Polymers 2016, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcangeli, T.; Skrbic, T.; Azote, S.; Marcato, D.; Rosa, A.; Banavar, J.R.; Piazza, R.; Maritan, A.; Giacometti, A. Phase Behavior and Self-Assembly of Semiflexible Polymers in Poor-Solvent Solutions. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 8940–8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picu, R.C.; Sengab, A. Structural evolution and stability of non-crosslinked fiber networks with inter-fiber adhesion. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 2254–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; DeBenedictis, E.P.; Keten, S. Cohesive and adhesive properties of crosslinked semiflexible biopolymer networks. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 3807–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBenedictis, E.P.; Zhang, Y.; Keten, S. Structure and Mechanics of Bundled Semiflexible Polymer Networks. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 6123–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüngel, A. Polymer Chains and Networks: Statistical Foundations and Computer Simulations; Oxford University Press, U.K., 2005.

- Groot, R.D. Mesoscale simulation of semiflexible chains. II. Evolution dynamics and stability of fiber bundle networks. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 224904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depta, P.N.; Gurikov, P.; Schroeter, B.; Forgács, A.; Kalmár, J.; Paul, G.; Marchese, L.; Heinrich, S.; Dosta, M. DEM-Based Approach for the Modeling of Gelation and Its Application to Alginate. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 2022, 62, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Liang, D.; Harden, J.L.; Leheny, R.L. Slow dynamics, aging, and glassy rheology in soft and living matter. Solid State Commun. 2006, 139, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, S.C.; Leporini, D.; Puosi, F. Structure and Mechanical Properties of a Porous Polymer Material via Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Polymers 2023, 15, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieleg, O.; Kayser, J.; Brambilla, G.; Cipelletti, L.; Bausch, A.R. Slow dynamics and internal stress relaxation in bundled cytoskeletal networks. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testard, V.; Berthier, L.; Kob, W. Intermittent dynamics and logarithmic domain growth during the spinodal decomposition of a glass-forming liquid. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 164502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tateno, M.; Tanaka, H. Distinct elastic properties and their origins in glasses and gels. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccariello, S.; Brumberger, J. On the Porod law. J. Appl. Cryst. 1988, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Galmarini, S.; Kröger, M. Energy formulation for infinite structures: order parameter for percolation, critical bonds and power-law scaling of contact-based transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 196101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelb, L.D.; Gubbins, K. Pore Size Distributions in Porous Glasses: A Computer Simulation Study. Langmuir 1999, 15, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masubuchi, Y. Phantom chain simulations for fracture of end-linking networks. Polymer 2024, 297, 126880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, S.; Lu, B.; Rubinstein, J. Nearest-neighbor distribution functions in many-body systems. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 41, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M.; Agrawal, S.; Galmarini, S. Generalized geometric pore size distribution code GPSD-3D for periodic systems composed of monodisperse spheres. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2024, 301, 109212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, W. Particle and particle systems characterization: small-angle scattering (SAS) applications; CRC Press, 2013.

- Gelb, L.D.; Gubbins, K. Characterization of porous glasses: Simulation models, adsorption isotherms, and the Brunauer- Emmett- Teller analysis method. Langmuir 1998, 14, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, G. Intraneuronal Neurofibrillary Tangles Isolated from Alzheimer’Disease Affected Brains Visualized by Vertical Platinum-Carbon Replication for TEM. Microscopy and Microanalysis 1997, 3, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuelli, M.; Germerdonk, T.; Cao, Y.; Peydayesh, M.; Bagnani, M.; Handschin, S.; Nyström, G.; Mezzenga, R. Polysaccharide-reinforced amyloid fibril hydrogels and aerogels. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 12534–12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Modelling Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.W.; Mazenko, G.F.; Valls, O.T. Classes for growth kinetics problems at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 9481–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubelski, A.; Sokolov, I.M.; Klafter, J. Nonergodicity mimics inhomogeneity in single particle tracking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 250602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikoubashman, A.; Milchev, A.; Binder, K. Dynamics of single semiflexible polymers in dilute solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 234903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.; Frey, E. Disentangling entanglements in biopolymer solutions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heussinger, C.; Schüller, F.; Frey, E. Statics and dynamics of the wormlike bundle model. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2010, 81, 021904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.S.; Douglas, J.F.; Freed, K.F. Influence of Cohesive Energy on Relaxation in a Model Glass-Forming Polymer Melt. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 8355–8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Vargas, S.; Rovigatti, L.; Sciortino, F. Connectivity, dynamics, and structure in a tetrahedral network liquid. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Hoy, R.S. Effect of chain stiffness and temperature on the dynamics and microstructure of crystallizable bead-spring polymer melts. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 052502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, P.; Hurtado, P.I.; Berthier, L.; Kob, W. Relaxation dynamics in a transient network fluid with competing gel and glass phases. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142, 174503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kob, W.; Barrat, J.L. Fluctuations, response and aging dynamics in a simple glass-forming liquid out of equilibrium. Eur. Phys. J. B 2000, 13, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kob, W.; Barrat, J.L. Aging Effects in a Lennard-Jones Glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4581–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. On some properties of the Mittag-Leffler function Eα(−tα). Discr. Contin. Dyn. Syst. B 2013, 19, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Kroy, K.; Frey, E. Dynamic scattering from solutions of semiflexible polymers. Phys. Rev. E 1997, 55, 3092–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S.; Hendrickson, B. A new parallel method for molecular dynamics simulation of macromolecular systems. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, H.R. Kinetic theory and rheology of dilute suspensions of finitely extendible dumbbells. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundamen. 1972, 11, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Simple, admissible, and accurate approximants of the inverse Langevin and Brillouin functions, relevant for strong polymer deformations and flows. J. Non-Newt. Fluid Mech. 2015, 223, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismantel, O.; Galata, A.A.; Sadeghi, M.; Kröger, A.; Kröger, M. Efficient generation of self-avoiding, semiflexible rotational isomeric chain ensembles in bulk, in confined geometries, and on surfaces. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 270, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hamada, Y.; Taniguchi, T. Multiscale simulations for polymer melt spinning process using Kremer–Grest CG model and continuous fluid mechanics model. J. Non-Newt. Fluid Mech. 2024, 325, 105195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Benoît, H.; Benoît, H. Polymers and Neutron Scattering; Oxford science publications, Clarendon Press, New York, 1996.

- des Cloizeaux, J. Form Factor of an Infinite Kratky-Porod Chain. Macromolecules 1973, 6, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Norisuye, T. Scattering function for wormlike chains with finite thickness. J. Polym. Sci. B 2004, 42, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spakowitz, A.J.; Wang, Z.G. Exact Results for a Semiflexible Polymer Chain in an Aligning Field. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 5814–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spakowitz, A.J. Semiflexible Polymers: Fundamental Theory and Applications in DNA Packaging. PhD thesis, California Institute of Technology, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Rosa, A.; Everaers, R. The radial distribution function of worm-like chains. Eur. Phys. J. E 2010, 32, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratky, O.; Porod, G. Röntgenuntersuchung gelöster fadenmoleküle. Recueil des travaux chimiques des pays-bas 1949, 68, 1106–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Megen, W.; Mortensen, T.C.; Williams, S.R.; Müller, J. Measurement of the self-intermediate scattering function of suspensions of hard spherical particles near the glass transition. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 58, 6073–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, K.; Horzela, A.; Penson, K.A. Non-Debye Relaxations: The Ups and Downs of the Stretched Exponential vs. Mittag–Leffler’s Matchings. Fractal and Fractional 2021, 5, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimperlein, M.; Schmiedeberg, M. Structural and dynamical properties of dilute gel networks in colloid–polymer mixtures. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 244903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmannsberger, P.; Kerschnitzki, M.; Repp, F.; Wagermaier, W.; Weinkamer, R.; Fratzl, P. The small world of osteocytes: connectomics of the lacuno-canalicular network in bone. New J. Phys. 2017, 19, 073019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K.; Araki, T. Formation dynamics of branching structure in the slippery DLCA model. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 234901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, R.J. Dots and Lines; Kent State University Press, United States, 1976.

- Berge, C. Cyclomatic number, The Theory of Graphs; Courier Dover Publications, 2001; p. 27–30.

- Tomadakis, M.M.; Robertson, T.J. Pore size distribution, survival probability, and relaxation time in random and ordered arrays of fibers. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, A.E. The Physics of Flow Through Porous Media; University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada, 1957; p. 7.

- Liu, Y.S.; Yi, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, G.Q.; Paul, J.C. Surface area estimation of digitized 3D objects using quasi-Monte Carlo methods. Pattern Recognition 2010, 43, 3900–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions; Dover Publ., New York, 1970.

- Levitz, P.; Tchoubar, D. Disordered porous solids: from chord distributions to small angle scattering. J. Phys. I 1992, 2, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommes, C.J.; Jiao, Y.; Roberts, A.P.; Jeulin, D. Chord-length distributions cannot generally be obtained from small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 2020, 53, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).