1. Introduction

Oncological conditions are of significant basic and clinical interest, as they rank among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [

1]. In Chile and globally, cancer is the primary cause of death, with colorectal cancer (CRC) being one of the three most prevalent types [

1,

2]. In CRC patients, pain is a debilitating symptom that profoundly impacts both patients and their families [

3,

4]. In advanced stages, pain prevalence exceeds 70% [

3]. Oncological pain is chronic and, as of 2022, is recognized as a disease in its own right, requiring long-term management [

5]. Additionally, patients may experience acute pain episodes, such as incidental pain (predictable pain triggered by specific actions), breakthrough pain (sudden onset), or analgesic gap pain (end-of-dose failure).

Oncological pain is classified by type—nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed [

6]—and may result from the cancer itself and/or the antineoplastic treatment employed. Another critical classification, essential for selecting treatment and monitoring pharmacotherapeutic outcomes, is pain intensity. The most commonly used tool is the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the most severe pain the patient has experienced) [

7].

A 2022 systematic review reported that moderate-to-severe oncological pain affects up to 30.6% of cancer patients [

8]. The pharmacotherapeutic management of such pain typically involves opioid medications combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen for both initiation and maintenance therapy [

9]. Opioid medications are included in the WHO’s list of essential medicines for pain management and palliative care [

10]. However, patient’s responses to opioids vary widely: some achieve optimal pain relief, while others experience adverse effects, lack efficacy, or develop opioid dependency syndrome [

11,

12]. A personalized approach is crucial for optimizing opioid use in terms of efficacy and safety.

Pharmacogenetics, a key tool in personalized medicine, aims to predict individual variability in drug response by analysing a patient’s genetic profile. This involves identifying allelic variants that may affect proteins involved in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [

13]. Studies in animal models and twins have shown that genetic factors account for 30–76% of the interindividual variability in opioid requirements [

14]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) currently recommends the study of pharmacogenetic biomarkers for codeine and tramadol use [

15]. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines [

16] for opioids and genes such as

CYP2D6, OPRM1, and

COMT provide dosage recommendations guided by the patient’s genetic profile. However, these guidelines have limited applicability and do not cover interventions or diseases not explicitly addressed.

Available clinical evidence supports the role of pharmacogenetic analyses in pain management. Polymorphisms in genes such as OPRM1 (mu-opioid receptor) and OPRD1 (delta-opioid receptor) are associated with altered therapeutic responses, and polymorphisms in OPRD1 particularly linked to opioid safety outcomes. These genes influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of opioids, with evidence primarily focused on tramadol, codeine, buprenorphine, fentanyl, morphine, and oxycodone.

Based on this background, this study hypothesizes that polymorphism in OPRM1 and OPRD1 influence the response to opioids, thereby conditioning their therapeutic effectiveness, and toxicity in patients with advanced-stage colorectal cancer.

2. Results

2.1. Population

Data from 69 patients with colorectal cancer were analyzed (

Table 1). Among these, 58% (40) were male, with a median age of 64 (IQR 30-90) years. Stage IV cancer was diagnosed in 39.1% (27) of the patients, with 77.8% (21) of these cases exhibiting primary metastases in the liver. Over 65% of the patients reported experiencing pain, primarily visceral and localized in the abdominal region.

Of the 69 patients, 28 (40.6%) used at least one type of opioid, with a median of 2 opioids per patient (IQR 1–5). A total of 62 opioids (38.3%) were observed out of 162 medications prescribed for pain management, which also included NSAIDs, paracetamol, anticonvulsants, among others. The most frequently used opioids were tramadol (18 (29.0%)), morphine and fentanyl (16 cases each, 25.8%), buprenorphine (6 (9.7%)), methadone (4 (6.5%)), and codeine (2 (3.2%)). Additionally, 10 (35.7%) of these patients required at least one opioid rotation, with a median of 2 opioid rotations per patient (IQR 1–4), accounting for a total of 20 rotations. Hospitalization data were available for 57 (82.6%) patients, of whom 43 (81.1%) had at least one, with a median of 5 hospitalizations. Among these, 26 (67.4%) patients experienced at least one pain-related hospitalization, with a median of 2 hospitalizations.

A total of 28 patients used opioids, with 18 of them experiencing 42 ADRs, resulting in an average prevalence of 2.3 ADRs per patient. The most frequent ADRs were nausea (n=11, 26.2%), constipation (n=8, 19.0%), and vomiting (n=6, 14.3%). Causality analysis revealed that 25 ADR (59.5%) were deemed probable, while 17 ADRs (40.5%) were classified as possible.

2.2. Genotypic and Allele Frequencies

The genotype distribution analysis (

Table 2) revealed that for the rs1799971 variant on the

OPRM1 gene, the most frequent genotype was A/A (n = 30), followed by A/G (n = 13). Similarly, for the rs510769 variant of the same gene, the C/C genotype was predominant (n = 20) with C/T (n = 17). In the case of

OPRD1 (rs2236861), the G/G genotype was most common (n = 24), with A/G (n = 18).

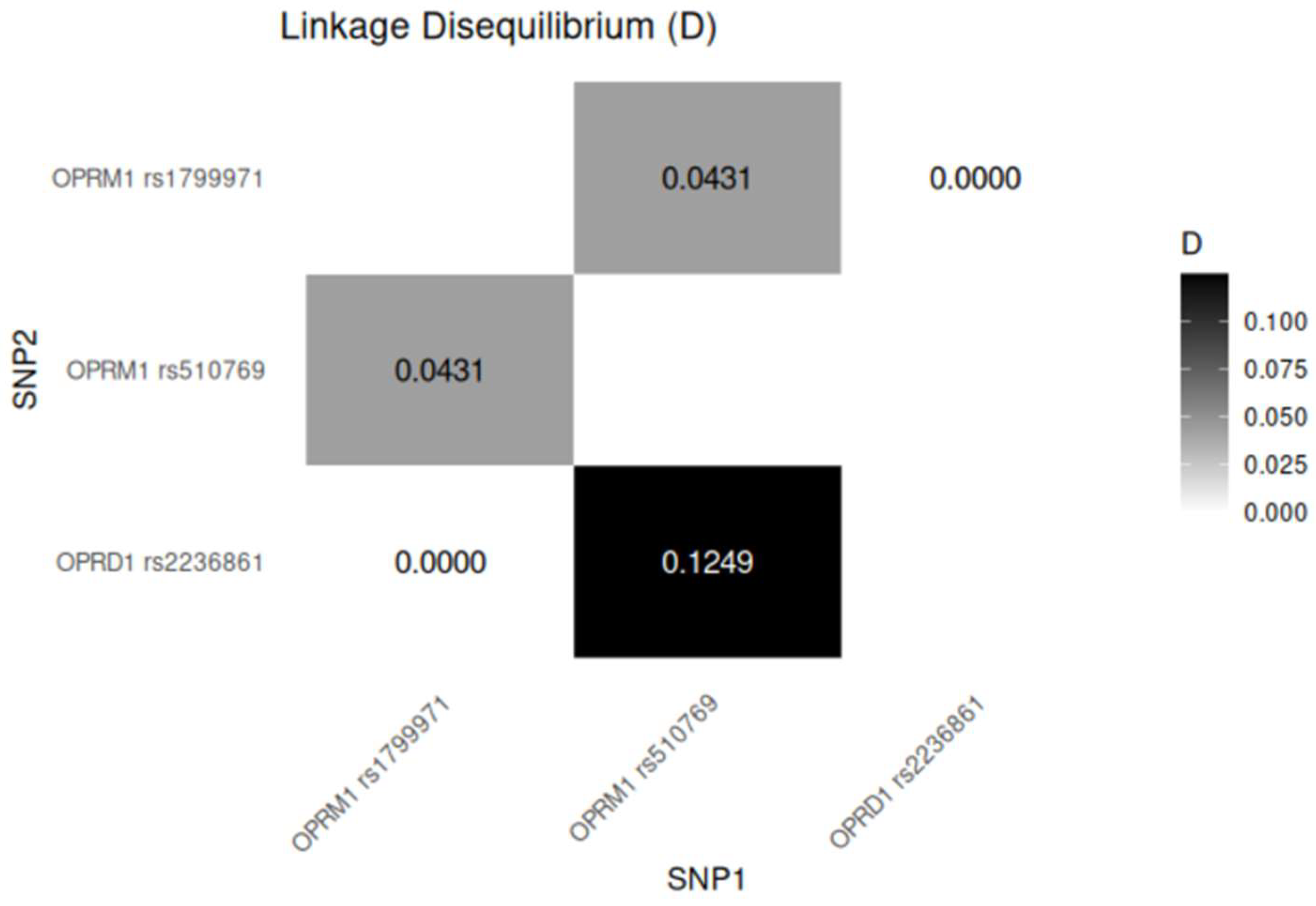

2.3. Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

There is a strong linkage disequilibrium between the OPRM1 variants, which are physically close to each other, with rs1799971 and rs510769 separated by approximately 8609 base pairs (bp) on chromosome 6. Additionally, the OPRM1 rs1799971 and OPRD1 rs2236861 variants, located on different chromosomes, may also exhibit functional linkage. Both results are statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium for variants of OPRM1 and OPRD1. *p value < 0.05 is considered significant.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium for variants of OPRM1 and OPRD1. *p value < 0.05 is considered significant.

2.4. Association Analysis

2.4.1. Association of Genotypes with ADR and Pain

The association between genotypes of the OPRM1 and OPRD1 genes with ADR and the presence of pain was analyzed. For ADR, the OPRM1 gene polymorphisms rs1799971 and rs510769 did not show statistically significant associations (p = 0.05935, and p = 0.3114, respectively). However, a significant association was observed with OPRD1 rs2236861 (χ² = 6.3333, p = 0.04214), suggesting that this variant may contribute to the occurrence of ADR. Regarding the presence of pain, a significant association was found between the A/A genotype of OPRM1 rs1799971 and the occurrence of pain (p = 0.007955), suggesting a potential influence on pain perception. This analysis included all patients, regardless of opioid use, and compared individuals reporting pain versus those without pain. In contrast, OPRM1 rs510769 (p = 0.7386) and OPRD1 rs2236861 (p = 0.8911) were not significantly associated with pain.

2.4.2. Association of Alleles Frequencies and Pain

An allelic frequency distribution of specific polymorphisms in

OPRD1 and

OPRM1 genes, comparing individuals with and without the presence of pain was performed. A highly significant difference in allelic frequencies was observed across all analyzed polymorphisms (chi-squared test, p < 2

-16). The G allele of

OPRD1 (rs2236861), A allele of OPRM1 (rs1799971) and the C allele of

OPRM1 (rs510769) were more frequent in individuals experiencing pain (see

Figure S1).

In addition, the allele frequency distributions for individuals with and without ADR were also analyzed. Highly significant differences were observed for all analyzed polymorphisms (chi-squared test, p < 2

-16). For

OPRM1 (rs1799971), the A allele was more frequent in individuals with ADR. Similarly, for

OPRM1 (rs510769), the C allele was significantly associated with ADR. Finally, for

OPRD1 (rs2236861), the G allele was substantially overrepresented in individuals with ADR compared to the A allele in those without ADR (see

Figure S2).

2.4.3. Logistic Regression Models for ADR and Pain

The association between the genotypes of the

OPRM1 and

OPRD1 genes and the occurrence of ADR was assessed using several logistic regression models. However, no statistically significant associations were identified between the evaluated genotypes and ADR risk (

Table S1). Similarly, logistic regression models were used to assess the association between the genotypes of

OPRM1 and

OPRD1 and the presence of pain. Again, the analysis did not reveal statistically significant associations between the genotypes and pain presence (

Table S2).

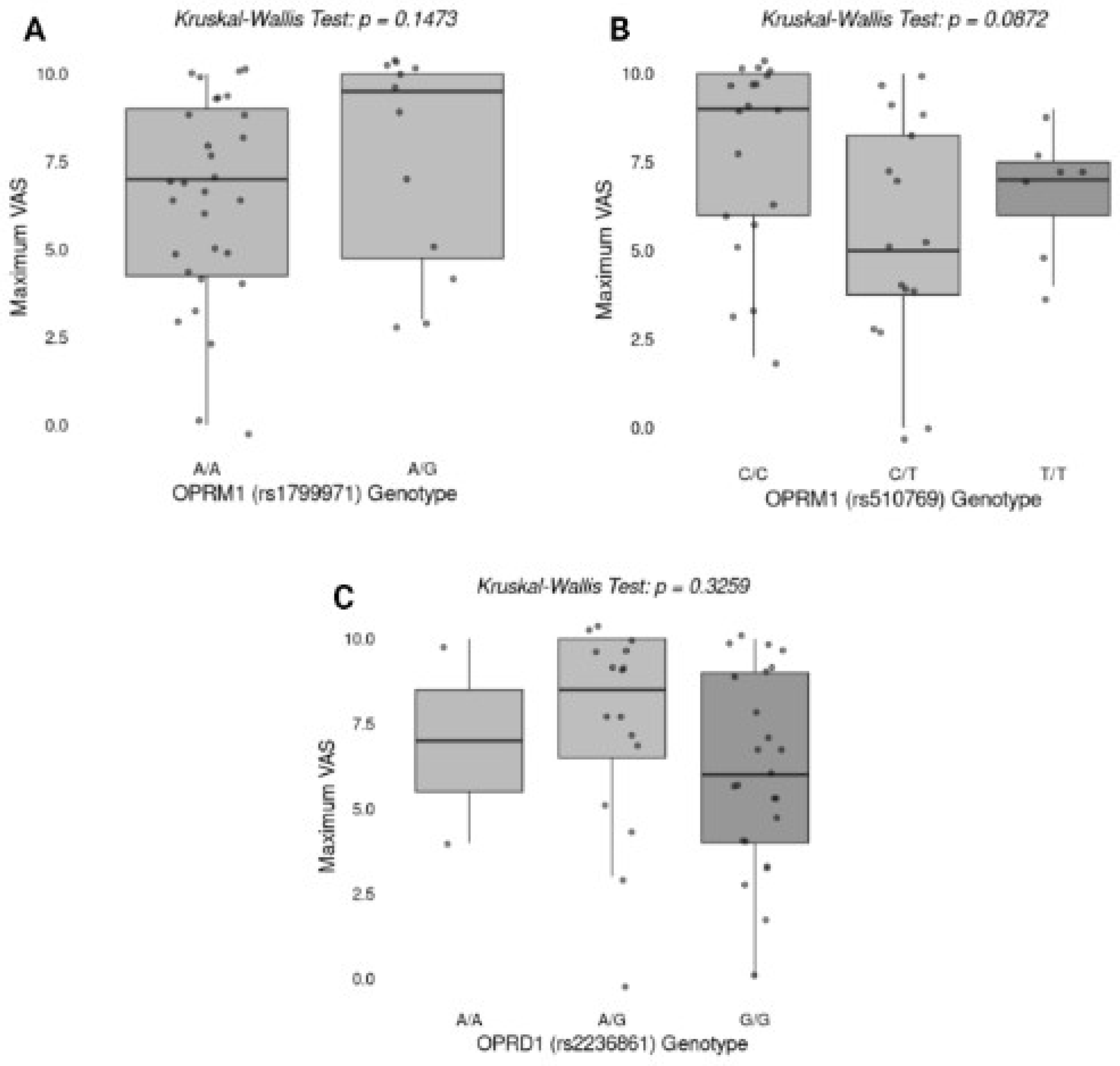

2.4.4. Association Between Genotypes and Effectiveness of Pain Relief

Figure 2 illustrates the association between specific genotypes of

OPRM1 (rs1799971, rs510769) and

OPRD1 (rs2236861) and the maximum Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for pain. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to evaluate differences in maximum VAS scores among different genotypes. No statistically significant differences were found for

OPRM1 rs1799971 (p = 0.1473),

OPRM1 rs510769 (p = 0.0872), or

OPRD1 rs2236861 (p = 0.3259).

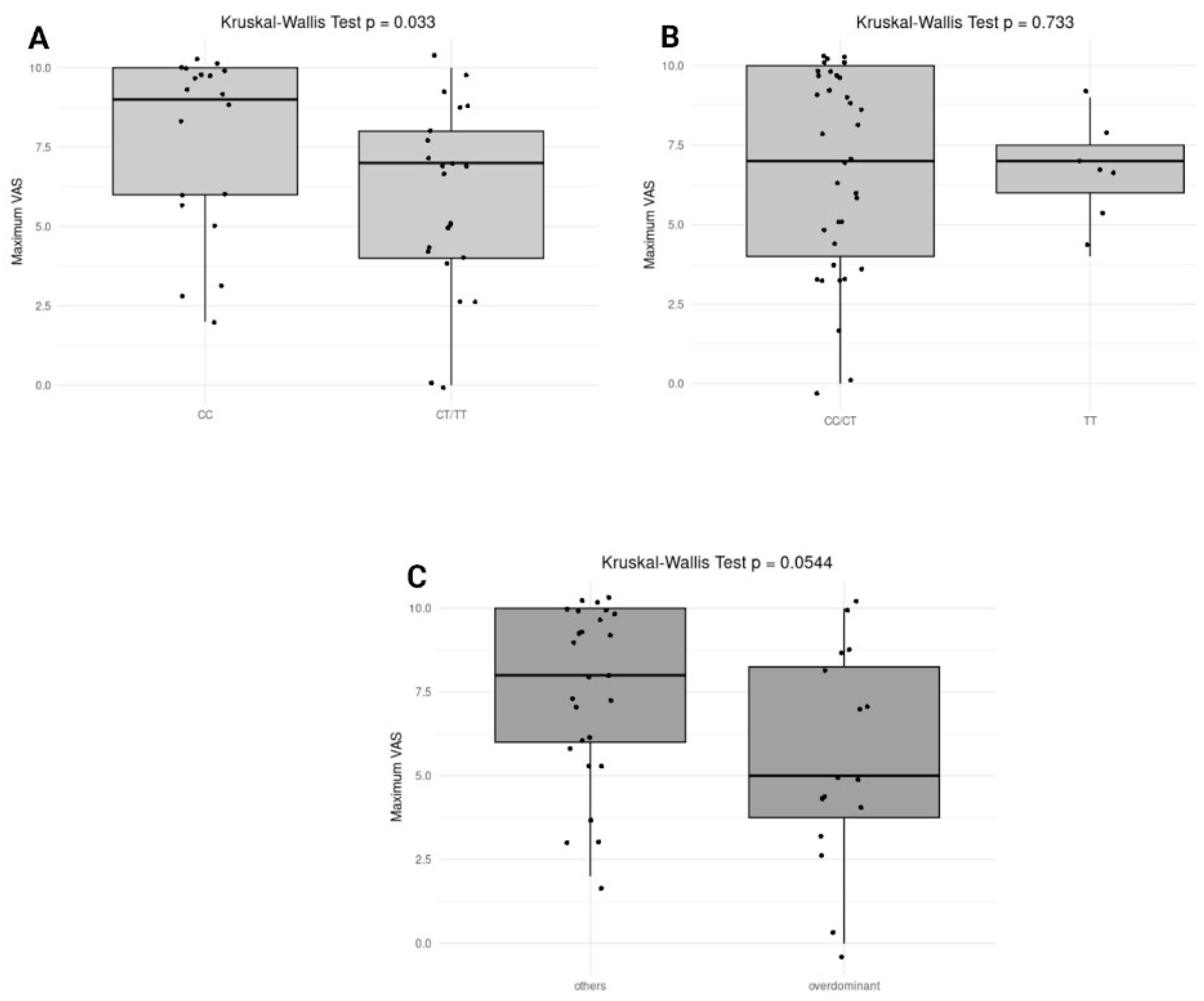

2.4.5. Association of Genotypes with Pain Severity and ADR

Different genetic models (dominant, recessive, and overdominant) were applied for genes OPRM1 (rs510769) and OPRD1 (rs2236861) to evaluate their influence on ADR. Across all genetic models tested for both genes, no significant associations were found. Specifically, the dominant model for OPRD1 showed a p-value of 0.2628, while other models showed even less notable differences in their respective comparisons. The association between pain severity and genetic variants did not reveal any significant associations between the genetic variants and maximum VAS. The closest to significance was the overdominant model of OPRD1, with a p-value of 0.1575.

The association between

OPRM1 (rs510769) and

OPRD1 (rs2236861) genotypes and pain severity was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test across different genetic inheritance models, as shown in

Figure 3. In the dominant model for

OPRM1 (rs510769), a significant difference was observed with a p-value of 0.033, indicating that individuals carrying the CT or TT genotype might experience lower maximum pain levels compared to those with the CC genotype. In contrast, the recessive model (CC/CT vs. TT) did not show a significant association (p = 0.733), suggesting no difference in maximum pain levels between TT carriers and the combined CC/CT group (

Figure 3B). The overdominant model (CC/TT vs. CT) showed a trend toward significance (p = 0.0544), indicating a potential difference in pain severity for individuals with the CT genotype compared to those with CC or TT genotypes (

Figure 3C). On the other hand, no significant associations were observed for

OPRD1 (rs2236861) genotypes across any of the inheritance models, suggesting that this variant may not influence pain severity in the analyzed cohort.

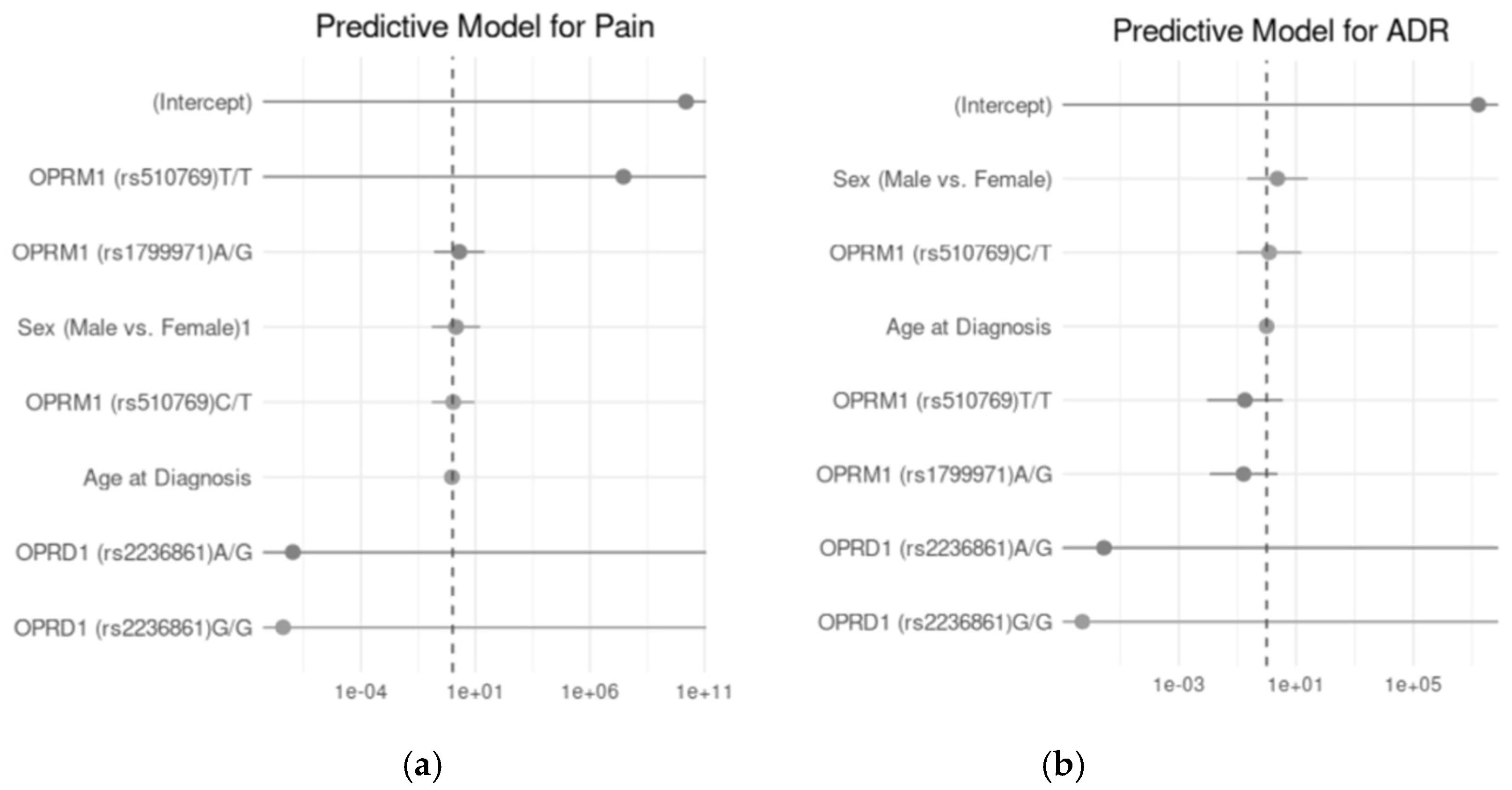

2.4.6. Association Genotypes with Pain Severity and Number of ADR Under Different Inheritance Models

Figure 4 illustrates the predictive models for pain and ADR using logistic regression analyses. The odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals are presented for the key predictors, including genetic polymorphisms and demographic factors, for each outcome. In A, the predictive model for pain shows the relationship between

OPRM1 (rs510769, rs1799971) and

OPRD1 (rs2236861) genotypes, along with demographic factors such as sex and age at diagnosis, in predicting pain occurrence. Although none of the genotypes or demographic factors demonstrated a statistically significant association with the likelihood of pain. B, depicts the predictive model for ADR, where similar predictors were analyzed to assess their impact on ADR incidence. Again, no statistically significant predictors were identified.

3. Discussion

The demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort align with existing literature on colorectal cancer patients, particularly regarding the high prevalence of pain and opioid use. Notably, 66.7% of patients reported pain, primarily visceral and localized in the abdomen, with opioids being a common therapeutic strategy. These findings emphasize the burden of pain in advanced cancer stages and highlight the need for effective pain management tailored to individual patient profiles. The median age of 64 years is consistent with global trends in colorectal cancer epidemiology [GLOBOCAN Gut 2023], and the predominance of male patients (58%) warrants further investigation into potential sex-related differences in pain perception.

This study explored the genetic variability in opioid receptor genes (

OPRM1 and

OPRD1) and their association with pain and adverse drug reactions (ADR) in colorectal cancer patients in a Latin American Mestizo sample (Chileans). While certain significant associations were identified, others underscore the complexity of genetic influence on opioid response and pain management. Our study revealed significant differences in genotypic and allelic frequencies across the polymorphisms analyzed, particularly in the

OPRM1 (rs1799971) and

OPRD1 (rs2236861) genes. The A/A genotype of

OPRM1 (rs1799971) was predominant, with a high frequency of the A allele, consistent with global [

17] and Latin American studies for this variant [

18].

The significant association of the G allele of

OPRD1 (rs2236861) with ADR suggests a potential pharmacogenomic marker for opioid tolerance or side effects. This aligns with prior research suggesting a role for the

OPRD1 gene in modulating opioid efficacy and side effects. However, most research on

OPRD1 has focused on opioid addiction [19; 20]. For example, Beer et al. reported significant associations between

OPRD1 variants and opioid addiction [

19]. These findings fall outside the scope of our study, which focuses on ADR and pain severity in cancer patients. This highlights the need for further research to investigate the impact of

OPRD1 variants on opioid response in the context of cancer-related pain.

The association of the A/A genotype of

OPRM1 (rs1799971) with the presence of pain reinforces the hypothesis that this variant may influence pain sensitivity and opioid response. This result appears to diverge from the findings of Yu et al., whose meta-analysis concluded that carriers of the G allele (AG+GG) required higher opioid doses for effective cancer pain management compared to AA homozygotes [

21]. Several factors could contribute to this discrepancy. First, population-specific genetic variations may play a crucial role, as the meta-analysis by Yu et al. noted that the association between the G allele and increased opioid requirements was particularly significant among Asian patients. In contrast, no statistically significant correlation was observed in Caucasian populations. Our study, conducted in a Latin American cohort, may reflect genetic differences that influence the analgesic response differently from Asian or Caucasian groups.

Additionally, differences in pain assessment methodologies and clinical settings might account for these contrasting results. The Yu et al. study primarily focused on opioid dose requirements for pain management, whereas our study assessed the presence of pain itself. This variation in endpoints—opioid consumption versus pain perception—could lead to differing interpretations of the OPRM1 polymorphism’s role.

Further analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of different inheritance models (dominant, recessive, and overdominant) on the association of OPRM1 and OPRD1 polymorphisms with pain and ADR outcomes. The observed association between the OPRM1 (rs510769) polymorphism and pain severity, particularly under the dominant inheritance model, aligns with existing literature on the role of OPRM1 variants in pain perception and opioid response. While specific studies on rs510769 are limited, research on other OPRM1 polymorphisms, such as A118G (rs1799971), has demonstrated significant effects on opioid receptor function and individual variability in pain sensitivity. For instance, a study by Zhang et al. reported that the A118G variant influences opioid receptor binding and is associated with altered pain thresholds [22]. In our study, however, we did not observe all three genotype categories for the rs1799971 polymorphism, as the G/G genotype was absent. As a result, we were unable to perform inheritance model analyses for this variant. Although our study did not find significant associations for the OPRD1 (rs2236861) polymorphism, previous research has indicated that other OPRD1 variants may play a role in pain modulation and opioid efficacy. Taken together, these findings highlight the significance of accounting for genetic variability in opioid receptor genes when assessing approaches to pain management.

Although the predictive models for pain and ADR did not identify statistically significant predictors, the trends observed for certain genotypes (e.g., OPRD1 rs2236861 and ADR) highlight the complexity of pain and ADR in clinical settings. The lack of significance may stem from the limited sample size, underscoring the need for larger studies to validate these findings. Nonetheless, the observed trends provide a rationale for incorporating pharmacogenomic testing into clinical practice to optimize pain management and minimize ADR, especially in high-risk populations.

This study highlights the relevance of pharmacogenomics in colorectal cancer pain management and ADR prediction in a Latin American cohort. The findings underscore the importance of considering population-specific genetic variability when interpreting pharmacogenomic data. However, the limited sample size and lack of longitudinal follow-up constrain the generalizability of our results. Future studies should aim to include larger multiethnic cohorts, particularly from European populations, to validate our findings and facilitate the implementation of personalized medicine approaches.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

A cohort of 69 genomic DNA samples was obtained from patients aged 18 years or older, recruited from the National Cancer Institute (INC) and the Clinical Hospital of the University of Chile (HCUCH). All patients were diagnosed with stage III or IV colorectal cancer. This study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Clinical Research Center (CEIC-CEC) (register number 002146, 04/16/2024). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

4.2. Sample and Clinical Data Collection

Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples or peripheral blood, depending on availability. Samples and clinical data were obtained in collaboration with the Biobank of Tissues and Fluids at the University of Chile (BTUCH). The Biobank managed all sample collection, storage, and clinical data management aspects. Clinical data were extracted from patient’s hospital medical records and organized using the REDCap data collection system. All samples were processed and stored following standardized protocols.

4.3. Genomic DNA Extraction Procedure

DNA extraction from FFPE samples was performed using the Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, freshly cut tissue sections (10–20 µm thick) with a tumor cell content of 50–80% were deparaffinized and lysed using proteinase K. After centrifugation, DNA was precipitated while RNA remained in the supernatant. For peripheral blood samples (12–15 mL), genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit in accordance with standard protocols. DNA quality and quantity were assessed using the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio measured with a DeNovix DS-11 spectrophotometer, complemented by agarose gel electrophoresis to ensure DNA integrity.

4.4. Genotyping

Genotyping was conducted using real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) with TaqMan® probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a Stratagene Mx3000p Real-Time PCR System (Agilent Technologies).

4.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudioTM and the SNPStats web tool. Descriptive analyses were performed to summarize sociodemographic and clinical variables, including sex, age, opioid usage, and other relevant factors. Continuous data were described using central tendency and dispersion measures, while categorical data were presented as frequency tables and graphs. Associations between genotypes and outcomes, such as adverse drug reactions (ADR) and pain presence, were evaluated using the chi-squared test, while differences in maximum pain intensity (VAS scores) across genotypes were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to predict ADR or pain presence based on genotypes and demographic factors. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between polymorphisms in OPRM1 and OPRD1 genes was also analyzed to explore potential functional relationships between variants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Association of alleles frequencies and pain; Figure S2: Association of alleles frequencies and ADR; Table S1: Logistic regression model for ADR; Table S2: Logistic regression model for pain.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, L.A.Q., N.M.V. and C.G-C.; methodology, C.G-C and L.C.; software, C.G-C. and M.F.M.; validation, L.A.Q. and C.G-C.; formal analysis, C.G-C. and N.A.; investigation, C.G-C, L.C., B.T. and N.V.; resources, L.Q.; data curation, C.G, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G-C.; writing—review and editing, C.G-C, L.A.Q. and M.F.M.; supervision, L.A.Q. and O.B.; project administration, L.A.Q. and N.M.V.; funding acquisition, L.A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fondecyt ANID, grant number 1211948.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Clinical Research Center (CEIC-CEC) (register number 002146, 04/16/2024)). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results will be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Latin American Society of Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine (SOLFAGEM) by sponsoring this article and to the cancer patients from the “Instituto Nacional del Cáncer” and “University of Chile Clinical hospital” for their altruistic collaboration in pursuit of the common welfare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Cancer Observatory, GLOBOCAN 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas – Chile. Anuario de estadísticas vitales, 2019. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/nacimientos-matrimonios-y-defunciones/publicaciones-y-anuarios/anuario-de-estad%C3%ADsticas-vitales-2019.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Zielińska, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Makaro, A.; Sałaga, M.; Fichna, J. Management of pain in colorectal cancer patients. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 157, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, J.; Dibble, S.L.; Dodd, M.J.; Miaskowski, C. Mood states of oncology outpatients: does pain make a difference? J. Pain Symptom Manage. 1995, 10(2), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades, Undécima Revisión (CIE-11). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 11 June 2024).Nijs, J.; Leysen, L.; Adriaenssens, N.; et al. Pain following cancer treatment: guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive and central sensitization pain. Acta Oncol. 2016, 55 (6), 659–663. [CrossRef]

- Vicente Herrero, M.T.; Delgado Bueno, S.; Bandrés Moyá, F.; et al. Valoración del dolor. revisión comparativa de escalas y cuestionarios. Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor. 2018; 25, 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, R.A.H.; Brom, L.; Theunissen, M.; et al. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer 2022: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2023, 15(3), 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241550390 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325771/WHO-MVP-EMP-IAU-2019.06-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Pergolizzi, J.V., Jr.; Magnusson, P.; Christo, P.J.; et al. Opioid therapy in cancer patients and survivors at risk of addiction, misuse or complex dependency. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 691720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlin, J.S.; Khodyakov, D.; Arnold, R.; et al. Expert panel consensus on management of advanced cancer–related pain in individuals with opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4(12), e2139968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiñones, L.; Roco, A.; Cayún, J.P.; et al. Clinical applications of pharmacogenomics. Rev. Med. Chile 2017, 145(4), 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, E.E.; Lariviere, W.R.; Belfer, I. Genetic basis of pain variability: recent advances. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/science-and-research-drugs/table-pharmacogenomic-biomarkers-drug-labeling (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. CPIC® Guideline for Opioids and CYP2D6, OPRM1, and COMT. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/guideline-for-codeine-and-cyp2d6/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Hwang, I. C.; Park, J.-Y.; Myung, S.-K.; Ahn, H. Y.; Fukuda, K.; Liao, Q. OPRM1 A118G Gene Variant and Postoperative Opioid Requirement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, R.; Hohl, D. M.; Glesmann, L. A.; Catanesi, C. Diferenciación de los genes OPRM1 y COMT en poblaciones de la provincia de Chaco. RUNA, archivo para las ciencias del hombre 2022, 43, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, B.; Erb, G.; Glück, T.; et al. Genetic Variants in GAL and OPRD1 Contribute to Opioid Addiction. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013, 13, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. C.; Lynskey, M. T.; Heath, A. C.; Wray, N.; Agrawal, A.; Shand, F. L.; Henders, A. K.; Wallace, L.; Todorov, A. A.; Schrage, A. J.; Madden, P. A. F.; Degenhardt, L.; Martin, N. G.; Montgomery, G. W. Association of OPRD1 Polymorphisms with Heroin Dependence in a Large Case-Control Series. Addiction Biology 2014, 19, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wen, L.; Shen, X.; Zhang, H. Effects of the OPRM1 A118G Polymorphism (Rs1799971) on Opioid Analgesia in Cancer Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Pain. 2019, 35, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Johnson, A. D.; Papp, A. C.; Sadée, W. Allelic Expression Imbalance of Human Mu Opioid Receptor (OPRM1) Caused by Variant A118G*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 32618–32624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).