1. Introduction

The central goal of contemporary schools is to enable continuous improvement of teaching and learning and reduce achievement gaps among students from diverse backgrounds (Goldring, 2009). The success of schools in realizing this goal primarily depends on two key components of the educational system: teachers and school leaders (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020; Spillane et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2022).

Although teaching is a rewarding job from several aspects, teachers need emotional support so that they can emotionally recharge themselves to keep dealing with the diverse needs of students (Richards, 2020). Research in the educational psychology field has shown that teachers' emotional well-being is one of the most significant factors that influence their teaching performance (Chang, 2013; Xiyun et al 2022). A particular line of investigation in the school psychology field has focused on teacher self-efficacy as a significant affective variable because it is closely linked to instructional effectiveness and improved student outcomes (Klassen and Tze, 2014; Karakose et al., 2024a). These studies found significant associations between teacher self-efficacy and other affective domains of teaching such as higher levels of job satisfaction (Buric´ and Kim, 2021; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2014), commitment (Lu et al., 2016; Waweru et al., 2021), work engagement (Han and Wang, 2021; Wang et al., 2022), resilience (Heng and Chu, 2023) and lower levels of stress and burnout (Greenier et al., 2021; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2017; Zee and Koomen, 2016). Therefore, teachers with stronger self-efficacy are more capable of putting individual value and effort into achieving educational goals (Tzovla and Kedraka, 2023), demonstrating stronger dedication to their profession, deriving better enjoyment from cultivating students’ learning, building better relationships with students and showing less frustration and exhaustion in the face of difficult situations (Goddard and Kim, 2018; Hen and Chu, 2023; Lazarides et al., 2020). As a possible determinant of teachers’ will to have stronger bonds with students and employ improved instruction, teacher self-efficacy is closely linked to greater student outcomes (Xie et al, 2022; Zee and Koomen, 2016). Therefore, identifying factors that could enhance or decrease teachers’ self-efficacy has become crucially important (Alanoğlu, 2022; Barni et al., 2019).

Studies on school effectiveness and improvement have, on the other hand, drawn attention to the role of principal leadership behavior in enhancing student outcomes (Bellibaş and Liu, 2017; Hitt and Tucker, 2016). These studies which investigated a variety of leadership models evidenced that effective principal leadership behavior had much to do with facilitating the teaching/learning practice at school (Gurr et al., 2007; Heck and Hallinger, 2009; Liu and Hallinger, 2018; Pietsch and Tulowitzki, 2017). In their two successive studies synthesizing the results of aggregated principal leadership behavior research, Leithwood et al. (2008, 2020) stated that ‘principal leadership behavior is second only to classroom teaching as an influence on pupil learning’ (Leithwood et al., 2008, p. 28), and ‘school leaders improve teaching and learning indirectly and most powerfully through their influence on staff motivation, ability and working condition’ (Leithwood et al., 2020, p. 6). As underlined by Bossert (1988) in the growing stage of principal leadership behavior-student outcomes research, school principals contributed significantly to improving student outcomes through defining the vision and goals of the school, creating a learning-friendly climate, and strategically allocating resources. More recently, Pietsch et al. (2023) noted that principal leadership behavior not only have direct effects on student outcomes but also exerts indirect effects through their influence on teacher emotions, beliefs, and practice as much as their influence on school climate and organization.

This prior evidence that principal leadership behavior matters in facilitating student outcomes through their influence on both people and processes has cultivated research interest in how principal leadership behavior could influence teachers’ beliefs and practices (Liu et al., 2021). As people ‘who influence and mobilize others in the pursuit of a goal’ (Hitt and Tucker, 2016; p. 3), improved student outcomes in the current case, school principals are considered to have a vital role in supporting teachers' self-efficacy through several mechanisms such as communicating a strong vision, modelling the way, providing individual support, building a climate of trust, and facilitating collaborative efforts to attain educational goals (Robinson et al., 2008; Xie et al, 2022). Despite the initial debates over which leadership model served best to this end in the educational leadership literature, three leadership models have stood out: instructional leadership, transformational leadership, and distributed/shared leadership. These leadership models were even merged under the name of ‘Leadership for Learning’ (Ahn et al., 2021; Boyce and Bowers, 2018; Hallinger, 2011), considering that the influence of leadership on teacher and student outcomes does not only happen through their engagement with classroom instruction but also through ‘bundles of activities exercised by a person or group of persons’ (Leithwood, 2012, p. 5) to establish a better environment for teaching and learning.

Although research from educational psychology and leadership research have contributed to our understanding of the role of teacher self-efficacy and principal leadership behavior in facilitating student outcomes, their results considered separately offer little guidance for policy and practice. Understanding the complex relationships between these variables requires a more holistic and comprehensive analysis. In addition, as the influence of leadership on student outcomes can occur indirectly over teacher-level variables (Dutta and Sahney, 2022; Hallinger et al., 2020; Robinson et al., 2008), and teacher self-efficacy is considered one of the strongest variables through which leadership can influence student outcomes (Ross and Gray, 2006), investigation into their empirical relationship can culminate better insights. In this respect, the current study aims to test the fit of the hypothesized relationships between principal leadership behavior (i.e., instructional, transformational, and distributed leadership), teacher self-efficacy, and student outcomes by the cumulative analysis of findings presented by prior research from a variety of contexts

1.1. Conceptual Background and Hypothesis Building

1.1.1. Principal Leadership Behavior

Leadership is defined as ‘the exercise of influence on organizational members and diverse stakeholders toward the identification and achievement of the organization’s vision and goals’ (Leithwood, 2012; p. 3). In the educational leadership field, this influence was mostly attributed to the school principal, and earlier research on school effectiveness tended to focus on the instructional leadership roles of the principal as the most significant means of facilitating student outcomes (Robinson et al., 2008). However, empirical evidence which suggests that principal leadership behavior is multifaceted and too complex to be practiced by a single person has directed investigations to a more holistic understanding of leadership practice at schools. As a result, investigations to understand which leadership model had a stronger influence on school outcomes have incrementally given way to more integrated views of leadership with an emphasis on the multiple leadership roles of the school principal and the relational influence process that accrues from the interaction and collaboration of the school community (Gurr, 2016; Karakose and Tülübaş, 2024). This line of research associated school outcomes with three particular leadership models: instructional leadership, transformational leadership and distributed leadership (Daniëls et al., 2019; Hallinger, 2011; Wu and Shen, 2022). The current analysis was also grounded on these three models of leadership due to their closer association with teacher and student outcomes.

Early research into school effectiveness, which is often measured over average achievement of students (Burušić et al., 2016), focused on the roles of the principal that were directly related to instruction and curriculum development with the assumption that principals could facilitate student outcomes mostly by these means (Dutta and Sahney, 2022; Hallinger et al., 2020). Principals practice instructional leadership by creating a supportive learning environment, defining the vision and goals of the school clearly, aligning the curriculum, conveying higher expectations, and monitoring and supervising instruction (Zhan et al., 2023). All of these processes eventually contribute to the improvement of student outcomes (Walker and Hallinger, 2015).

Instructional leadership is one of the most frequently studied leadership models in the field (Hallinger et al., 2020; Karakose et al., 2024b). These studies revealed that principal instructional leadership was positively correlated with several student and teacher-level variables (Pietsch et al., 2023), and its direct influence on student outcomes was greater compared to other leadership models (Robinson et al., 2008). Considering this prior evidence, we hypothesize that;

H1. Instructional leadership has a positive direct influence on student outcomes.

Transformational leadership was borrowed from the general organization leadership field and developed into a principal leadership behavior model which promotes school change through facilitating teachers’ ability and will to seek continuous improvement (Berkovich, 2018; Hallinger, 2011). Hence, transformational leadership aims to empower teachers as individual and collective change agents in the incessant pursuit of higher purposes that could leverage school effectiveness (Gılıç et al., 2024; Leithwood and Sun, 2012). Unlike instructional leadership, which has a focus on improving instructional quality, transformational leadership aims to create a strong culture of change to better respond to the incessant transformation of expectations from schools (Leithwood et al., 2004).

Transformational leaders prioritize the goals and needs of the school community ahead of their own and exert this understanding into the school culture by establishing such norms, emphasizing individual strengths and supporting their further improvement, promoting collaboration, being tolerant of diversity and promoting risk-taking (Anderson, 2017). By these means, transformational leadership has a strong potential to improve student outcomes and school effectiveness (Kouzes and Keams, 2013; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006; Mwovei, 2023; Robinson et al., 2008). Building on this perspective, we hypothesize that;

H2. Transformational leadership has a positive direct influence on student outcomes.

Prior studies on principal leadership behavior unveiled that leadership in schools was best enacted with a simultaneous practice of a variety of leadership tasks listed for different leadership models. For instance, in their seminal study, Marks and Printy (2003) found that principals who practiced instructional and transformational leadership simultaneously facilitated student outcomes better. In addition to this integrated view of leadership, they also suggested that instructional leadership was mostly a shared endeavor in effective schools. As subsequent studies continued to support these iterations, leadership has come to be viewed as a more interactive, reciprocal and collaborative process in which the whole school community engage in improving school effectiveness (Kwan, 2020; Marsh et al., 2014)

In recent years, educational scholars have begun to define principal leadership behavior as a shared and collaborative practice, assuming school principals have the responsibility to develop the collective leadership capacity at school, to find ways to involve teachers in decision-making and to support their continuous growth (Hitt and Tucker, 2016). According to the distributed leadership perspective, principal leadership behavior is best enacted through interactions among the principal, teachers, and the school context (Gronn, 2002; Spillane et al., 2001). This perspective offers a more holistic interpretation of principal leadership behavior beyond the sum of its parts, defining ‘leadership as less the property of individuals and more as the contextualized outcome of interactive, rather than unidirectional, causal process’ (Gronn 2002, p. 444). Research has already established positive correlations between distributed leadership and school improvement, and suggested that principal leadership behavior could leverage student outcomes when enacted as a distributed and shared practice (Amels et al., 2021; Bellibaş et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2016). Predicating on this early evidence, we hypothesize that;

H3. Distributed leadership has a positive direct influence on student outcomes.

1.1.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

Teacher self-efficacy is a psychological variable referring to teachers’ judgments and beliefs about their personal abilities to organize the necessary actions to perform their job roles as well as their expectancy to realize the desired outcomes with their actions (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2007; Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Wang, 2022). Bandura (1977) grounded his theory of self-efficacy on social cognitive theory and postulated that self-efficacy beliefs influence people’s actions, emotional status, cognitive processes and thinking patterns (Bandura, 1982, 1997). As teacher self-efficacy provides the foundation for teacher motivation, well-being, and feeling of accomplishment (Daing and Mustapha, 2022; Papadakis et al., 2024), it is considered to be a significant factor in improving student outcomes (Calik et al., 2012; Goddard et al., 2000; Klassen and Tze, 2014; Wang, 2022).

Bandura (1997) listed four factors that essentially influence self-efficacy: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and physiological and affective states. Prior evidence from both the educational psychology and leadership field has indicated that principal leadership behavior could influence teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs by all four means. Mastery experiences refer to teachers’ prior success in attaining educational goals while vicarious experiences refer to their observation of others’ success in achieving tasks (Bandura, 1997). Numerous studies have shown that principal instructional leadership promotes teachers’ confidence in teaching and improves their efficacy in crafting higher quality instruction and employing better classroom management through employing closer supervision, mentoring and role modeling, offering support in the case of challenging teaching experiences (Bellibaş and Liu, 2017; Calik et al., 2012; Duyar et al., 2013; Hallinger et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Sumuati and Niemted, 2020).

Similarly, transformational leadership can enhance teachers' self-efficacy through responding to the individual needs of teachers, enhancing their capacity to tackle with continuous change, defining a strong vision and goals and building a culture of collaboration and trust which support teachers pursuing these goals (Kaya and Kocyigit, 2023). Thus, transformational school leaders are likely to create a positive environment which could provide teachers with the social and affective support that they need to attain instructional goals (Aldridge and Fraser, 2016; Ker et al., 2022; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2019; Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2007). Transformational leadership is also conducive to teachers’ becoming more open to change and ready to take responsibility for entailing risks, which supports teachers’ sense of self-efficacy (Barni et al., 2019; Djigic et al., 2014). Therefore, transformational leadership can help teachers retain their confidence in helping students learn and keep at working with students who are relatively more challenging, have lower motivation or have difficulty in learning (Caprara et al., 2006; Gratacós et al., 2023; Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Yada et al., 2022).

As for distributed leadership, it is closely linked with individual and organizational capacity building (Hallinger, 2011) and this aspect of distributed leadership could be the key lever for people to carry on pursuing higher expectations and goals (Fullan, 2001). For instance, Cai et al. (2023) found that distributed leadership create higher levels of trust at school, which in turn enhances teachers’ self-efficacy. Results of other studies also evidenced that distributed leadership is a strong predictor of teacher self-efficacy (Katıtaş et al., 2022; Sun and Xia, 2018; Zheng et al., 2019).

Literature also lends support for the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between principal leadership behavior and student outcomes. For instance, Ross and Gray (2006) provided early evidence that teacher self-efficacy could be a powerful means of school leaders’ improving student outcomes. Similarly, Bush et al. (2018) underlined that there is growing evidence of the mediating effect of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between principal leadership behavior and improved student outcomes. In a more recent study, Leithwood et al. (2020) suggested that teacher self-efficacy could provide the emotional path from principal leadership behavior to student outcomes.

Predicating on this evidence on the close relation of principal leadership behavior, teacher self-efficacy, and student outcomes, we hypothesize that;

H4. Teacher self-efficacy mediates the relationship between instructional leadership and student outcomes.

H5. Teacher self-efficacy mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and student outcomes.

H6. Teacher self-efficacy mediates the relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes.

1.1.3. The Hypothesized Model

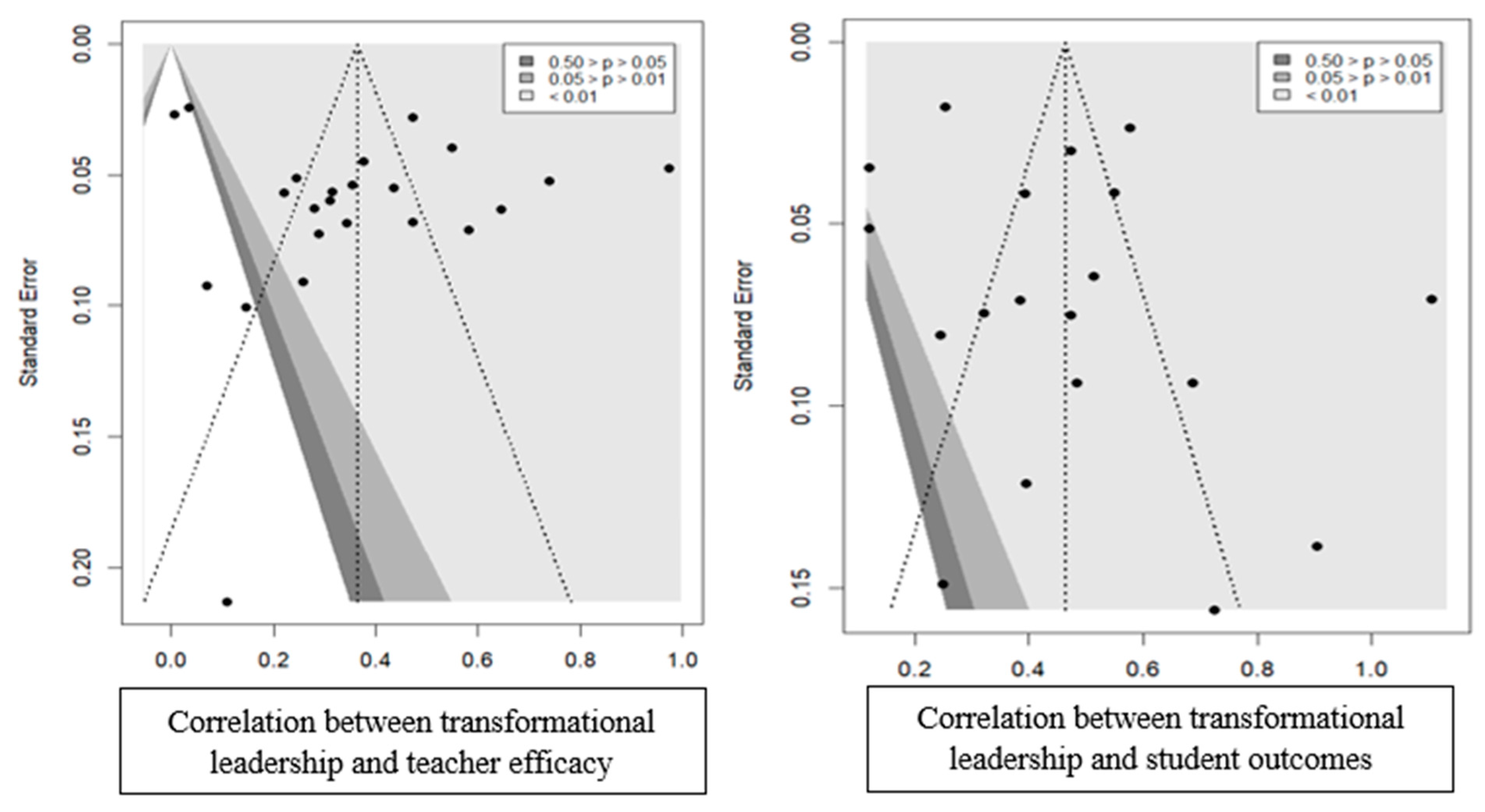

Using the six hypotheses we built over prior evidence from the literature, we developed the hypothesized model in

Figure 1, which we later tested using a meta-analytic structural equation modelling (MASEM).

2. Method

The theoretical model of the current study including principal leadership behavior, teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes were tested using meta-analytic structural equating modeling (MASEM). MASEM is a novel statistical method for testing causal relationships among variables in a theoretical model using the correlations and multiple regressions gathered from prior studies on the particular variables involved in the model (Jeyeraj and Dwivedi, 2020).

2.1. Data Collection and Extraction

The current study employs a systematic review methodology (meta-analytic structural equation modeling) in which the correlation values reported in prior studies on variables in the theoretical model are used to calculate overall estimates. Data for the study was collected from Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and other databases such as Google Scholar, ERIC, and Proquest, and the data extraction process followed the guidelines in the 2020 edition of the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses).

Data search was conducted on 11 February, 2024 using keywords such as “teacher self-efficacy”, “principal leadership behavior”, “instructional leadership”, “transformational leadership”, “distributed leadership”, “shared leadership”, “collective leadership”, “student outcomes”, “student achievement”, and “student growth”. These keywords were selected in accordance with the variables included in the theoretical model of the current study.

2.2. Study Evaluation and Selection

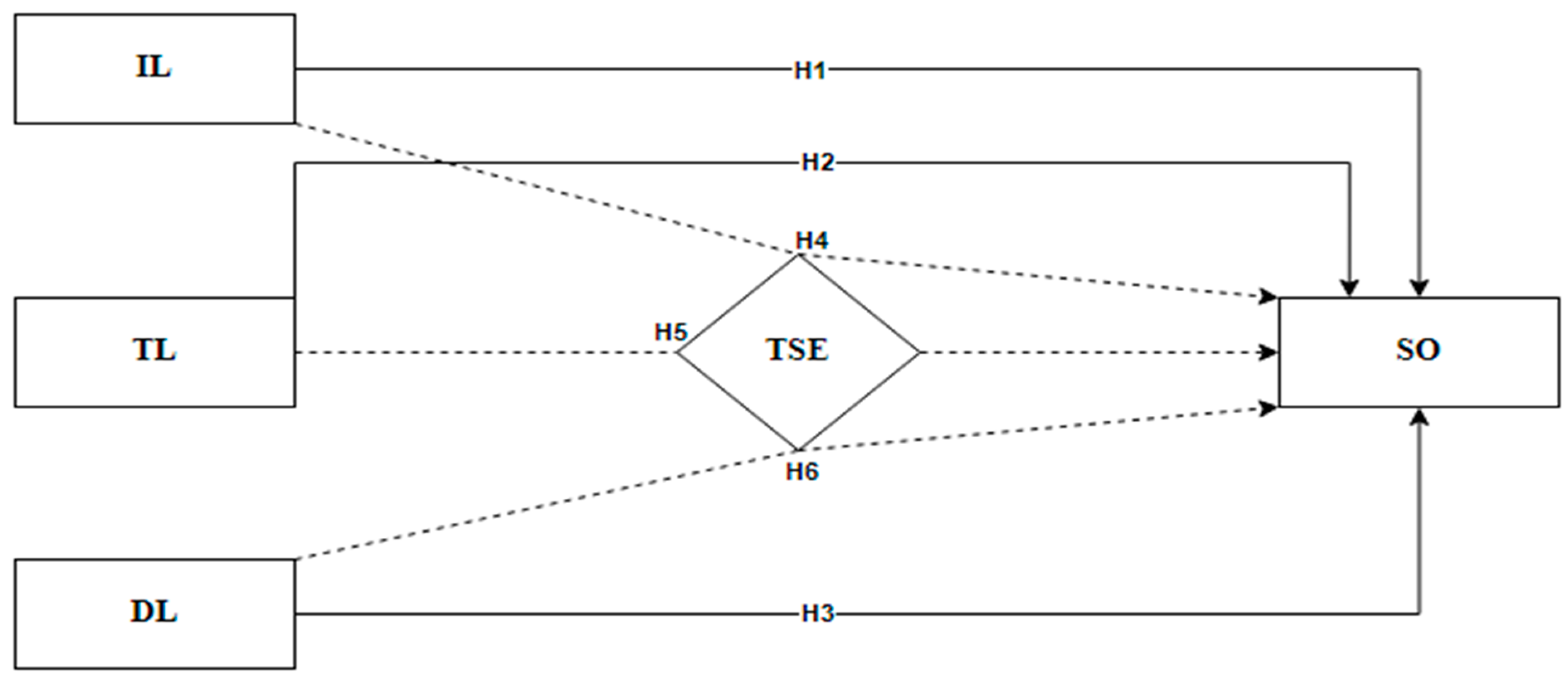

The list of studies yielded by the initial search on the databases were first analyzed to clear out the duplicates using the R software program. Next, the titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened in light of our predefined inclusion / exclusion criteria reported in

Table 1.

The initial evaluation of studies was conducted by two independent reviewers focusing on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the methodological quality of the studies (e.g., clearly-defined research purpose, congruence between the purpose, methodology and statistical analysis employed). Next, reviewers had a discussion session to reach to an agreement on the inclusion/exclusion of studies. When they could not reach any consensus, two other reviewers were also consulted before making a final decision. The data evaluation/selection process is reported in

Figure 2, which is prepared in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Detailed information about the full list of documents included in meta-analysis is provided as Supplementary material.

Our search of the databases returned a total of 744 documents in total: 297 documents from WoS, 318 from Scopus, and 129 from other sources (e.g., ERIC, Google Scholar, Proquest etc.). After identifying the duplicates using the R programming software, a total of 388 documents were left to screen for eligibility (after removing the 356 duplicates). Among these documents, we needed to exclude 298 documents for various reasons: 88 of them were out of scope, 119 for employing a review or qualitative methodology or being a conceptual paper, and 91 for not providing eligible data for MASEM analysis (e.g. the correlation coefficients). Consequently, values from a total of 90 documents (57 articles and 33 dissertations) were included in the MASEM analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

We began data analysis by correcting the correlation coefficients obtained from the studies using Fisher’s Z because correlation values greater than ±0.25 could show a non-normal distribution (Cooper, 2017, p.173). Next, we calculated the overall effect sizes of the corrected correlation values using the random effects model. These overall effect sizes were then converted back to Pearson’s r to be able to be interpreted according to Gignac and Szodorai’s (2016) scale, which interpreted correlation coefficients up to 0.1 as ‘small’, values up to 0.2 ‘medium’, 0.3 and higher as ‘large’.

In the second stage of the analysis, we evaluated the existence and magnitude of variance between the effect sizes using the heterogeneity test. We evaluated the existence of heterogeneity according to the significance of the test results where significant results (p<.05) indicated that the effect size varied significantly. We evaluated the size of the variance by calculating the I2 index which, according to Higgins et al. (2003), shows a ‘low’ level of variance up to 25%, ‘medium’ up to 50%, and ‘high’ up to 75%.

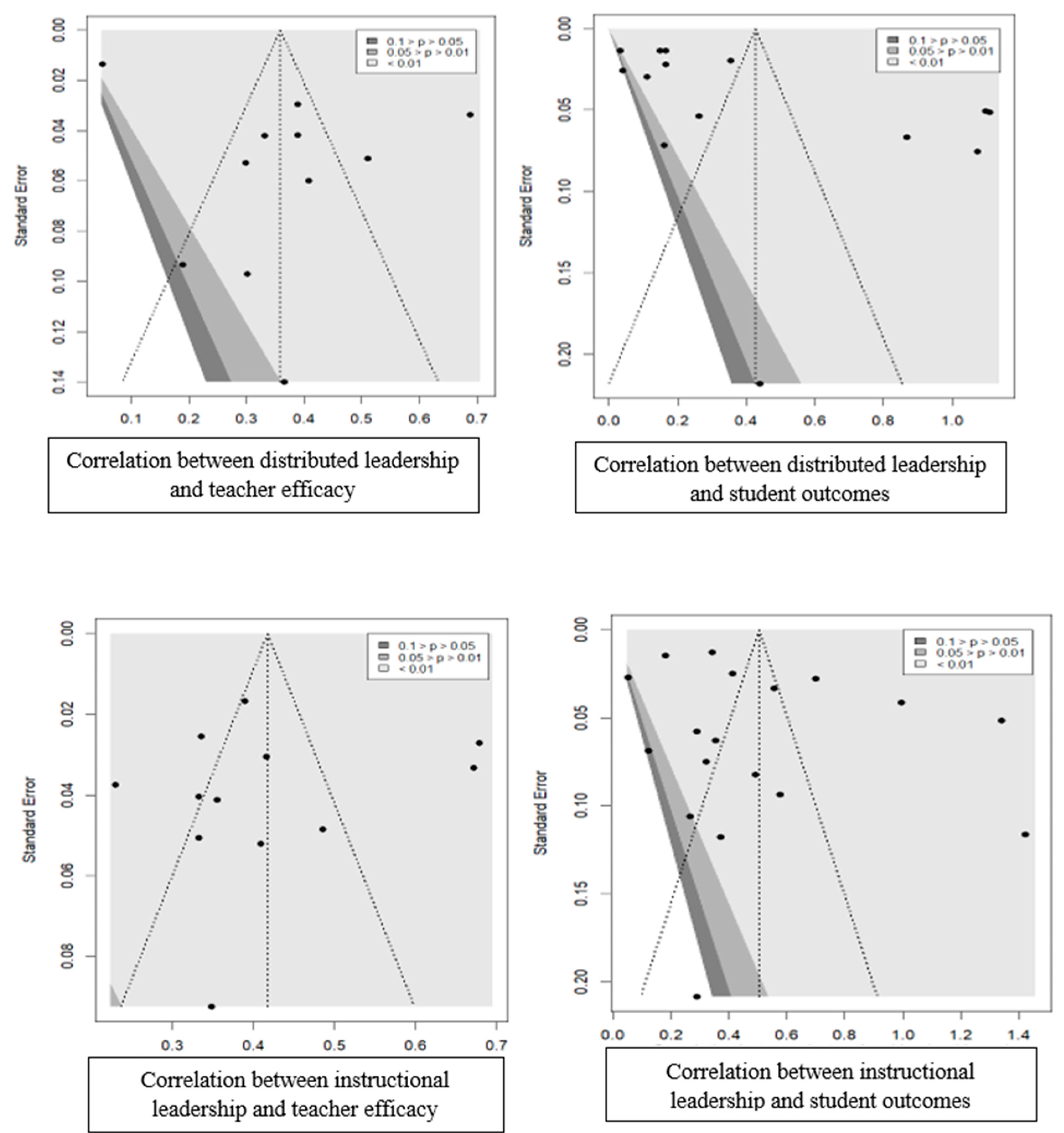

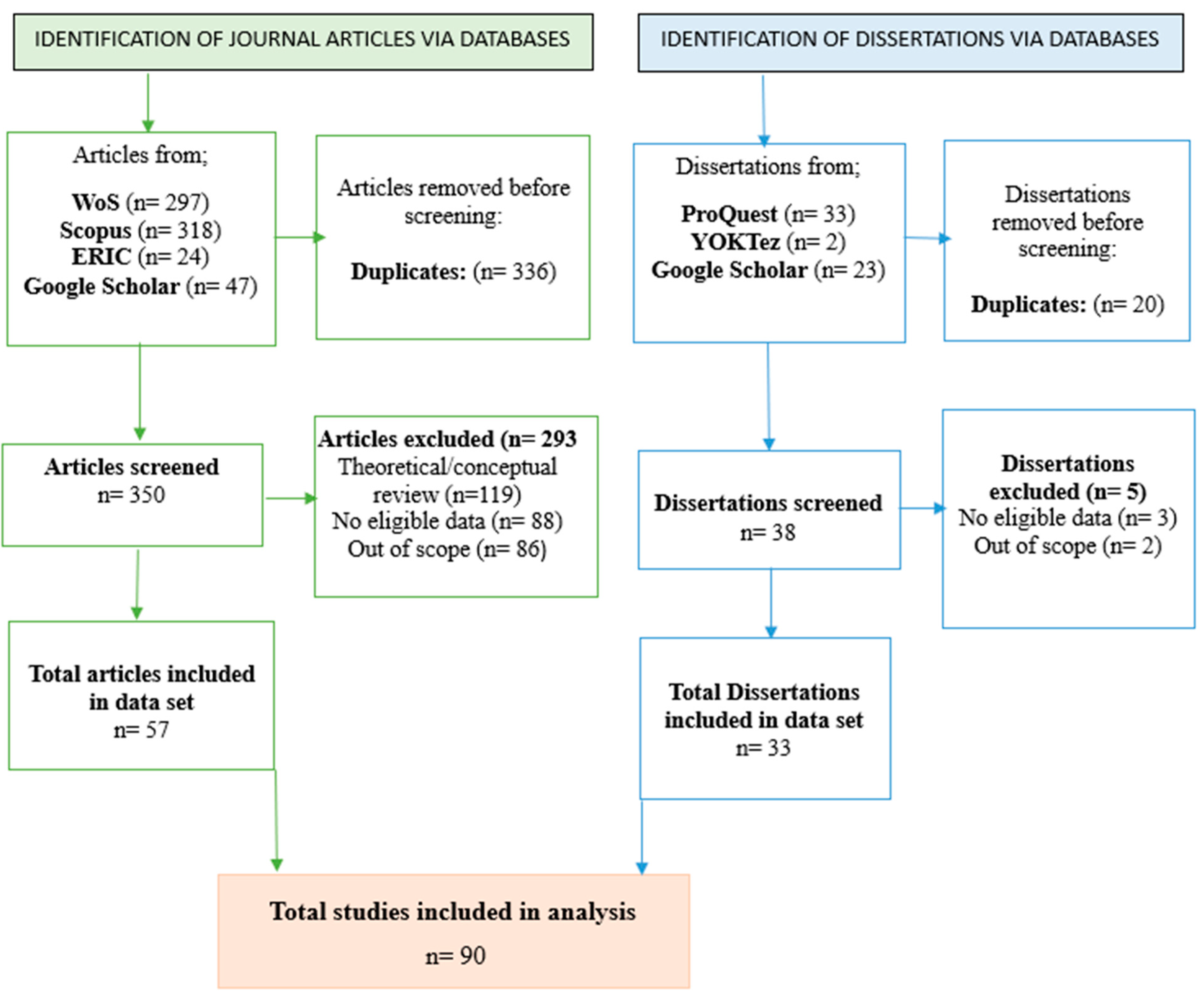

We also evaluated the risk of publication bias by producing contour funnel plots. The almost symmetrical distribution of results in the funnel plot indicated a low risk of publication bias. When this distribution is asymmetrical, whether it is significant is evaluated using regression (Egger et al., 1997) and rank correlation (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994) test results. All of these analyses were performed using the R platform using the meta package (Schwarzer, 2024).

For mediation analysis, on the other hand, we used two-staged structural equation modeling (TSSEM) developed by Cheung (2015a). During this analysis, we first formed a covariance matrix using the random effects model, which was next used to test the mediation models’ goodness of fit. As the models in the current study were saturated, we could not calculate the model-data fit indices but used ‘the estimation-based confidence intervals method’ (Jak, 2015; p.51) to test the significance of indirect effects of principal leadership behavior on student outcomes through teacher self-efficacy. At this stage, we also tested the moderating effects of school level, publication type, and continental context of the studies using the one-stage meta-analytic structural equation modeling (OSMASEM) (Jak and Cheung, 2020). For all these analyses, we used the metaSEM package (Cheung, 2015b), the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) and R codes written by Schutte et al. (2021).

3. Results

3.1. Overall Effect Size Between Leadership Style, Teacher Efficacy and Student Outcomes

The overall effect sizes calculated according to the random effects model for the relationship of Instructional leadership (IL), Transformational leadership (TL) and Distributed Leadership (DL) with teacher self-efficacy (TSE) and student outcomes (SO) are given in

Table 2.

The results in

Table 2 show that all three leadership models influence teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes significantly. The effect of instructional leadership on both teacher self-efficacy (r=0.396, 95% [0.325, 0.460]; p<.05) and student outcomes (r=0.466, 95%[0.315, 0.593]; p<.05) was large. Similarly, the effect of transformational leadership on teacher self-efficacy (r=0.349, 95% [0.261, 0.431]; p<.05) and student outcomes (r=0.434, 95%[0.338, 0.521]; p<.05) were both large. Distributed leadership was also found to have a large, positive effect on both teacher self-efficacy (r=0.344, 95%[0.249, 0.433]; p<.05) and student outcomes (r=0.404, 95%[0.249, 0.433]; p<.05).

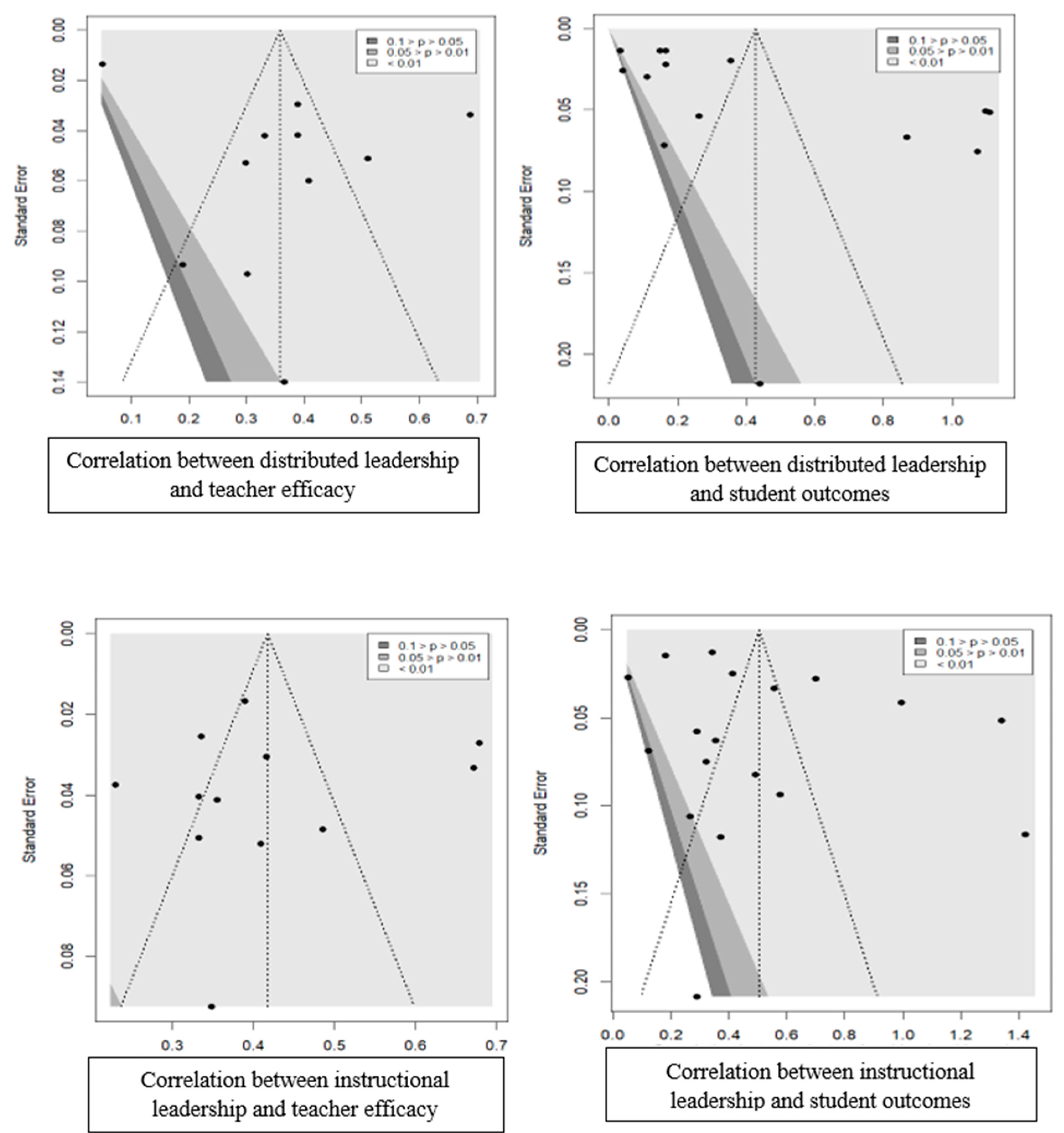

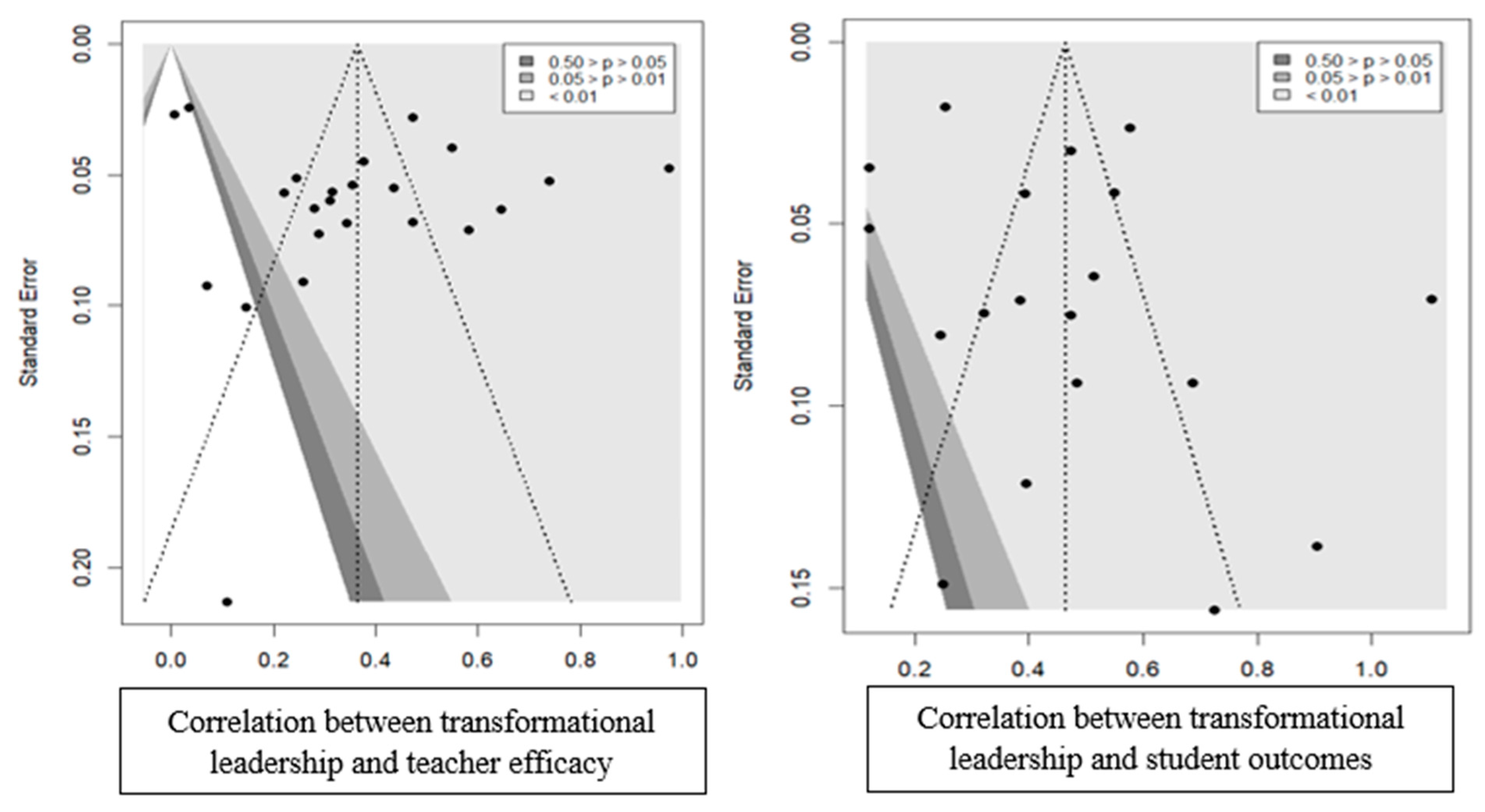

The heterogeneity test revealed a significantly large heterogeneity for all these relationships (p<.05). The funnel plot (see

Appendix A) analysis via Egger’s regression test and rank correlation tests indicated that the effect of publication bias was not significant for the calculated overall effect sizes.

3.2. Mediating Effect of Teacher Efficacy in the Relationship Between Instructional Leadership and Student Outcomes

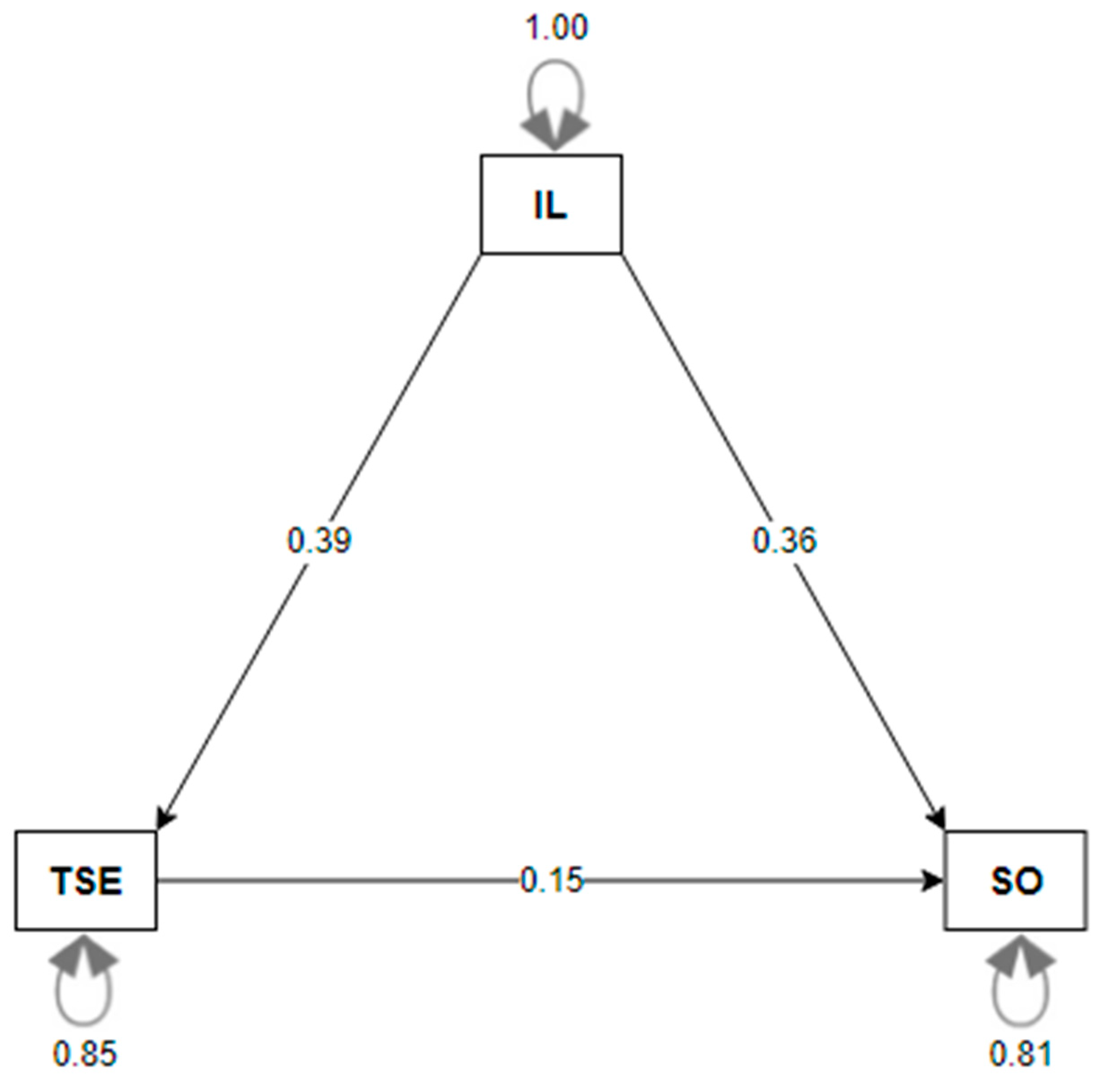

The correlation matrices created using the correlation coefficients from our dataset to test the mediating role of teacher efficacy in the relationship between instructional leadership and students' outcomes were found to be heterogeneous (χ(52)= 1355.415, p<.001). Accordingly, we used the random effects model to combine these correlation matrices in the first stage of MASEM. Next, we tested the fit of this mediation model using the overall correlation matrix calculated in the first stage. The path diagram of the model is demonstrated in

Figure 3.

The mediation model in

Figure 3 was saturated with 0 degrees of freedom. Therefore, no fit index was calculated. The path coefficient (direct effect) between instructional leadership and student outcomes was calculated as 0.357, 95% [0.224, 0.490], between instructional leadership and teacher self-efficacy as 0.389, 95% [0.328 0.450] and between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes as 0.153, 95% [0.049, 0.253]. According to these results, instructional leadership explains 15% of the variance in teacher self-efficacy. The direct and indirect effects of instructional leadership through teacher self-efficacy explain 19% of the variance in student outcomes. The indirect effect of instructional leadership on student outcomes was 0.060, 95%[0.020, 0.099]. These results evidence that teacher self-efficacy acts as a partial mediator in the relationship between instructional leadership and student outcomes. The due analysis to test whether there was a significant difference between direct and indirect effects indicated that the direct effect of instructional leadership on student outcomes was significantly larger than its indirect effect (χ(2)= 8.776, p<0.5).

At this stage, a moderator analysis was also conducted to test whether the school level, the publication type, and the continental context acted as categorical moderators in the relationship of instructional leadership with both teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes. The results showed that none of these categorical variables moderated these relationships significantly (p<0.5).

3.3. Mediating Effect of Teacher Efficacy in the Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Student Outcomes

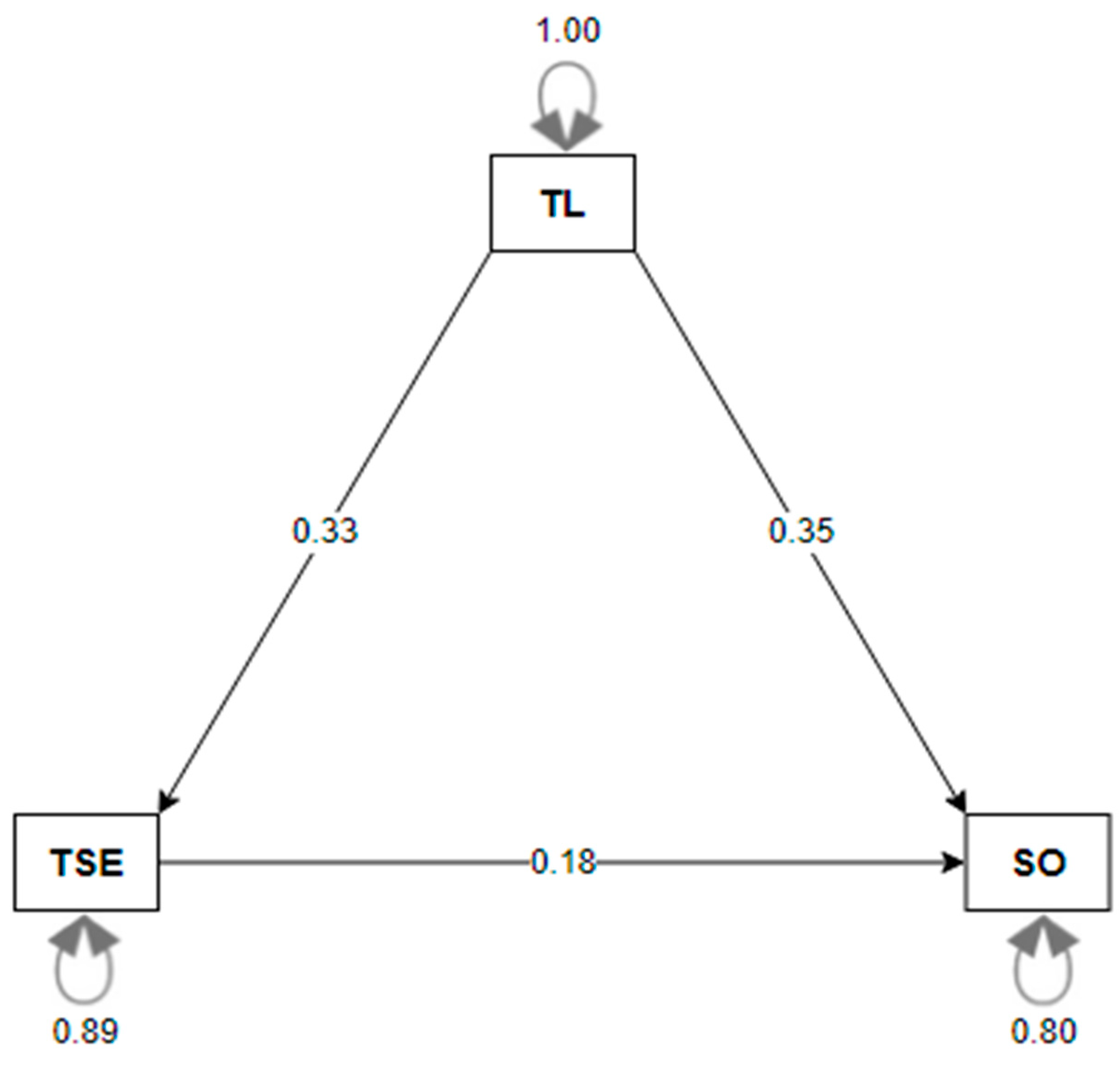

The correlation matrices created from the correlation coefficients to test the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between transformational leadership and student outcomes were found to be heterogeneous (χ(52)= 1321.884, p<.001). Accordingly, the random effects model was used to combine the correlation coefficients in the first stage of MASEM. Next, the overall correlation matrix calculated in the first stage was used to test the model’s goodness of fit. The relevant path graphic is demonstrated in

Figure 4.

Because the mediation model was saturated with 0 degrees of freedom, no fit index was calculated. The path coefficient (direct effect) between transformational leadership and student outcomes was calculated as 0.350, 95% [0.253, 0.445], between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy as 0.333, 95% [0.256 0.410] and between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes as 0.184, 95% [0.089, 0.276]. According to our results, transformational leadership explains 11% of the variance in teacher self-efficacy while the direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership explain 20% of the variance in student outcomes. The indirect effect of transformational leadership on student outcomes through teacher self-efficacy was 0.061, 95%[0.031, 0.095]. As the indirect effect is significant at the 95% confidence interval (p<.05), we can state that teacher self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and student outcomes. The analysis of whether there was a significant difference between the direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on student outcomes revealed that the direct effect of transformational leadership on student outcomes was significantly higher than its indirect effect (χ(2)= 1.453, p<0.5).

The moderating effect of the school level, the publication type and the continental context on the relationship of transformational leadership with teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes was also tested. The results showed that school level was a significant moderator on the relationship between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy (p= 0.015). To determine which school levels caused this difference, we conducted pairwise comparisons, whose results are presented in

Table 3.

The results of pairwise comparisons in

Table 3 show a significant difference (p <.05) between higher education and primary education Accordingly, we can state that the path coefficient between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy was found to be significantly higher in higher education context compared to those found in primary education context. However, school level was not a significant moderator in the relationship between transformational leadership and student outcomes (p>.05). The moderating effect of other categorical moderators (e.g., publication type and the continental context) was also not significant for the relationship of transformational leadership with both teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes (p>.05).

3.4. Mediating Effect of Teacher Efficacy in the Relationship Between Distributed Leadership and Student Outcomes

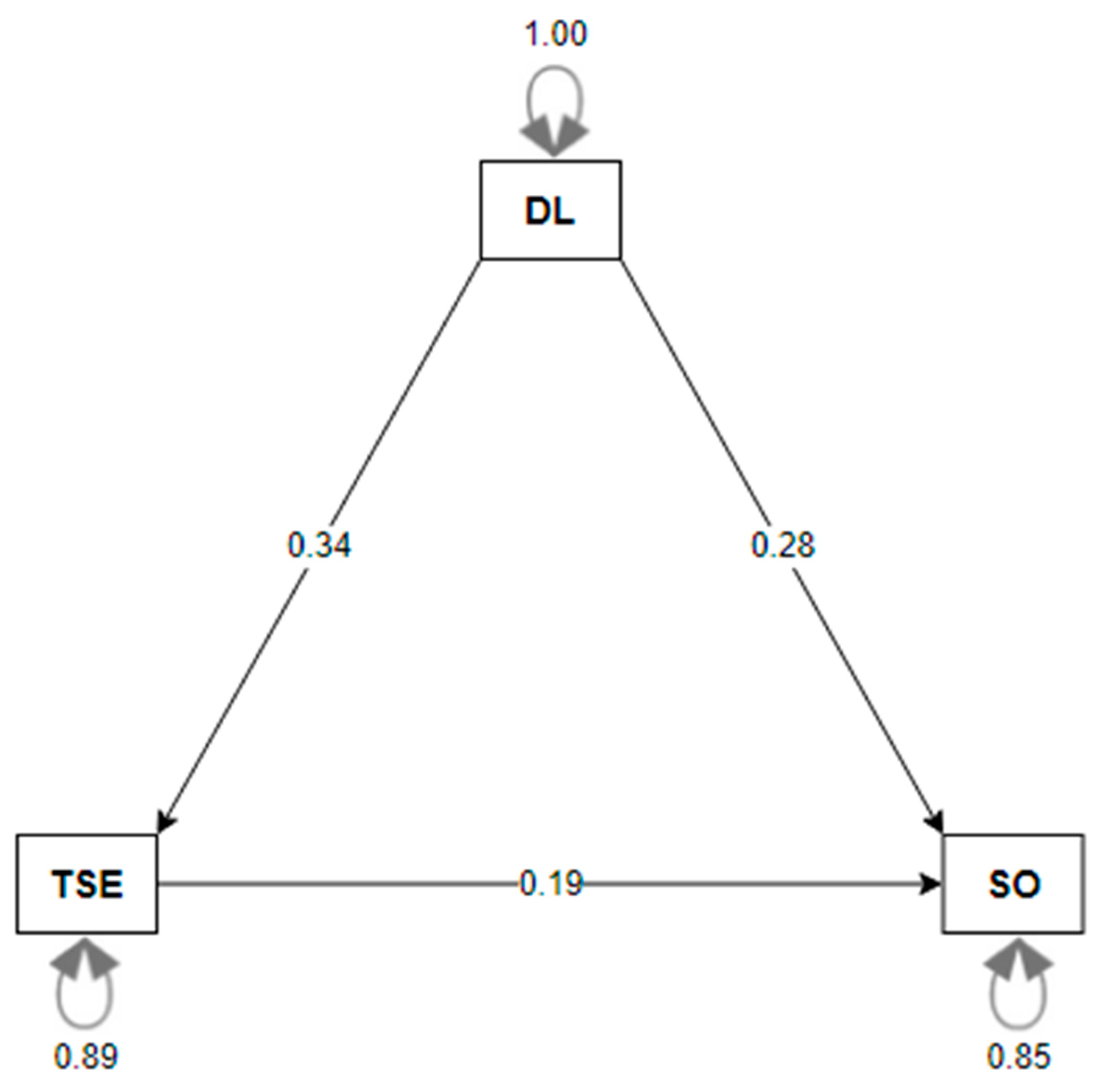

We tested the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes, we again created correlation matrices using the correlation coefficients from our dataset. As the correlation matrices were determined to be heterogeneous, it was determined that these matrices were heterogeneous (χ(46)=1507.852, p<.001), during the MASEM analysis, we first combined the correlation matrices using the random effects model, and then used this overall correlation matrix to test the model’s goodness of fit. The path graph of the model is presented in

Figure 5.

The mediation model was saturated with 0 degrees of freedom, so we did not calculate any fit index. The path coefficient (direct effect) between distributed leadership and student outcomes was calculated as 0.284, 95% [0.109, 0.459], between distributed leadership and teacher self-efficacy as 0.337, 95% [0.249, 0.425], and between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes as 0.186, 95% [0.073, 0.293]. Distributed leadership was found to explain 11% of the variance in teacher self-efficacy while the direct and indirect effect of distributed leadership explained 15% of the variance in student outcomes. The indirect effect of distributed leadership on student outcomes through teacher self-efficacy was 0.098, 95%[0.070, 0.128], and as the indirect effect was significant at the 95% confidence interval (p<.05), we can state that teacher self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes The variance analysis (ANOVA) performed to determine whether there was a significant difference between the direct and indirect effects of distributed leadership on student outcomes showed that its direct effect was greater than its indirect effect (χ(2)=4.455, p<0.5).

The results of the moderator analysis testing the effect of school level, the publication type, and the continental context showed that the school level was not a significant moderator on the relationship of distributed leadership with teacher self-efficacy (p=0.623) and student outcomes (p=0.056). was not a significant moderator. The continental context was not found to be a significant moderator on the distributed leadership and teacher self-efficacy relationship (p=0.056) while it was found to significantly moderate the relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes (p=0.030). According to these results, the effect of distributed leadership on student outcomes varies significantly across continents. The pairwise comparisons of the path coefficients calculated for different continents showed that studies from the American context reported significantly higher path coefficients between distributed leadership and student outcomes as compared to those from the Asian context (p<.05). The results are presented in

Table 4.

The publication type was also found to be a significant moderator on the DL-student outcomes relationship (p<.05) while it did not moderate the DL-teacher self-efficacy relationship significantly (p>.05). The path coefficients related to the moderation role of publication type in DL-student outcomes presented in

Table 5 indicates that the path coefficients between DL and student outcomes are significantly higher than that of dissertations (p<.05).

The fact that the path coefficients between DL and student outcomes are significantly higher than that of dissertations may indicate publication bias.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between principal behaviors and student outcomes. The study particularly focused on three models of leadership behaviors which also make up the Leadership for Learning framework, to investigate the direct and indirect effect of principal leadership behaviors on student outcomes using accumulated data from the literature. With this purpose, we first identified the overall effect size of the principal behavior-student outcomes relationship. We then tested the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in this relationship using meta-analytic structural equation modelling. We also conducted a moderator analysis to assess whether path coefficients between principal leadership behavior, student outcomes, and teacher self-efficacy differed significantly according to the type of study (article vs. dissertation), school type (from primary to higher education), and the continental context. The results indicated significant relationships between the variables, suggesting important implications for research and practice.

The overall analysis of the data revealed a significant, positive, and large effect of principal leadership behavior on both student outcomes and teacher self-efficacy, which is consistent with the results of numerous prior studies (Dutta and Sahney, 2016; Leithwood et al., 2019, 2020; Hitt and Tucker, 2016; Tan, 2020). Similarly, the analysis yielded significant, positive, and large effects of all three models of leadership behaviors, i.e., instructional, transformational, and distributed, on both student outcomes and teacher self-efficacy. These results support the previous iterations which assume that successful principal leadership can be achieved through the integrated practice of these leadership models in accordance with the contextual demands and needs (Leithwood and Sun, 2012; Marks and Printy, 2003). However, this does not refer to practicing a particular model of leadership in a particular context (e.g., the situational view of leadership) but points to the true mix of leadership practice that could serve the complex and interwoven needs of schools (Day et al., 2016; Drysdale and Gurr, 2011).

In support of these claims, our study also indicated that all three models of leadership behaviors had a greater direct effect on student outcomes than their indirect effect over teacher self-efficacy. Although contrary to Robinson et al.’s (2008) earlier finding that the effect of instructional leadership on student outcomes was three or four times higher than that of transformational leadership, several other research lend support to our findings from several aspects. For one thing, some studies showed that transformational leadership was a necessary condition for the effective practice of instructional leadership (Bellibaş et al., 2021; Kwan, 2020; Marks and Printy, 2003). For the other, transformational leadership aims to foster the capacity and commitment of the school community to attain educational goals and cultivate the school culture for improved school performance (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006). Transformational leadership also improves school organizational conditions by enhancing the relationship between teachers, students, and the school environment (Griffith, 2004; Shatzer et al., 2014). Therefore, transformational leadership has a strong potential to alter actual classroom practices which subsequently enhance student performance. As classified by Robinson et al. (2008), instructional leadership serves to creating ‘a learning climate free of disruption, a system of clear teaching objectives, and high teacher expectations for students’ (p. 638), while transformational leadership targets the holistic development of the school through building ‘a common vision, …developing [school] capacity to work collaboratively to overcome challenges’ (p. 639). From this perspective, our results indicate that both leadership models have the potential to improve student outcomes, but through different means and practices. Therefore, our results challenge Robinson et al.’s (2008) claim that one does not need ‘transformational leadership theory to study and develop this [e. i. the improved student outcomes] aspect of leadership’ (p. 663). On the other hand, the results lend support for Leithwood et al.’s (2010) opinion that principal leadership behavior in the current age of constant educational reforms require transformational abilities in addition to instructional leadership.

The same explanation can go for the distributed leadership-student outcomes relationship. As distributed leadership refers to the collective enactment of leadership as a function of school rather than a property of an individual (Gronn, 2002), it is not ‘something ‘done’ by an individual ‘to’ others, or a set of individual actions through which people contribute to a group or organization, …[but] a group activity that works through and within relationships, rather than individual action (Bennett et al., 2003, p. 3). As a collective school functioning, distributed leadership is expected to have a close relationship with improved student outcomes (Harris, 2013) because as teachers become more engaged with the core technologies of the school such as teacher professional development, curriculum development, coordination and management, collaboration for school improvement, and providing professional contributions to classroom instruction (York-Barr and Duke, 2004), they are likely to perform better to improve student outcomes (Tan et al., 2020)

The analysis of the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes has shown that teacher self-efficacy had a moderate direct effect on student outcomes. In the current case, the effect of principal leadership behavior on student outcomes was found to be higher than teacher self-efficacy. In fact, literature regarding the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes is rather contradictory; while some studies report a positive relationship (Bates, 2023; Gulistan et al., 2017; Perera and John, 2020), some report negative (Zee et al., 2018) or no relationship (Dale et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2012) between these variables. One reason for this difference could be the data used to assess student outcomes, which could be both academic and non-academic, and belong to different class levels or lessons. Therefore, as suggested by Zee et al. (2018), conceptualizing and measuring teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes at various levels could provide deeper insights into these inconsistent results. Zee and Koomen (2016), on the other hand, suggest that this inconsistency could be resulting from the reciprocal causal relationship between these two variables, and the fact that both variables are influenced by the interaction of numerous factors could yield lower levels of relationship. For instance, some research suggests that some variables such as teacher work engagement (Wang, 2022), attitude towards the teaching profession (Tella, 2008), teacher pedagogical knowledge (Fox, 2014) or teacher trust (Zhu et al., 2020) could influence the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and student outcomes.

The analysis of the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relationship between principal leadership behaviors and student outcomes has revealed that teacher self-efficacy acted as a partial mediator in the relationship between all three models of leadership and student outcomes. Accordingly, instructional leadership was found to affect student outcomes both directly and indirectly through enhancing teacher self-efficacy, but the indirect effect was found to be low. The indirect effect of instructional leadership explained 19% of the variance in student outcomes. Our results also indicated that the direct effect of instructional leadership on student outcomes was significantly higher than its indirect effect. In the literature, most studies found a direct effect between instructional leadership and student outcomes while noting its indirect effect as well (Hansen and Làrudsóttir, 2015; Leithwood et al., 2004; Robinson et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2020). On the other hand, more recent studies supported our finding that instructional leadership affected student outcomes both directly and indirectly through supporting teacher self-efficacy but with a higher direct effect (Akgöz, 2024).

Similar to the results for the effect of instructional leadership on student outcomes, both transformational and distributed leadership were also found to have a greater direct effect on student outcomes than their indirect effects on teacher self-efficacy. This might be due to the strong capacity-building nature of these leadership models, targeting the development and involvement of the whole school community in the achievement of the vision and goals of the school (Day et al., 2016; Hallinger, 2003; Printy and Liu, 2021). From this perspective, transformational leaders seem to not only enhance teachers’ self-efficacy but also motivate students to pursue higher expectations (Eliophotou Menon and Lefteri, 2021; Liu, 2018). This might even be achieved through improving student satisfaction (Hassan and Yau, 2013). Contrary to some research evidencing the indirect effect of transformational leadership on student outcomes (Leithwood and Sun, 2012; Marks and Printy, 2003; Robinson et al., 2008; Shatzer et al., 2014), some studies support our findings indicating that transformational leadership can both have direct and indirect effects on student outcomes (Chin et al., 2007; Dale et al., 2011).

In the same vein, involving teachers in decision-making and assuming collective responsibility for improvement and leadership to teachers, the distributed practice of leadership in schools could have a closer relationship with improved classroom instruction and collective efforts of both teachers and students to attain educational goals. Several studies have also provided evidence that distributed/shared forms of principal leadership behavior have a positive relationship with improved school outcomes, and distributed leadership can have a direct positive influence on classroom instruction and student outcomes (Braun et al. 2021; Copland, 2003; Li and Liu, 2022; Tian et al., 2016), in support of the current study’s results.

The moderator analysis, on the other hand, yielded contradictory results. For the relationship between instructional leadership and student outcomes, neither the type of the study nor the school level was found to be significant moderators. Similarly, the continental context of the studies also did not moderate their relationship. However, for the relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes, the continental context of the studies was found to be a significant moderator. Accordingly, results from Asian studies differed significantly from the European ones, indicating a stronger relationship between distributed leadership and student outcomes in the European context as compared to the Asian context. Distributed leadership eliminates the focus on hierarchical positions and calls for a more cohesive and collaborative practice at school. Thus, the responsibility of school management and administration is also shared among the whole school community (Spillane et al., 2004). These two diverse views regarding the center of authority at school might be reflecting the national culture. Indeed, in Asian cultures, which are defined as vertical-collectivist cultures, the positional authority of the leader is significant for the followers who demonstrate stronger acceptance and respect for the authority. In European cultures, which are mostly horizontal-individualistic, how a leader interacts with the followers and how s/he serves their personal needs and expectations could be a stronger determinant of their acceptance of the leader’s influence and authority (Farh et al., 2007; Triandis, 1995; Zhang and Zhu, 2008). This might explain our finding that distributed leadership was much more closely related to improved student outcomes in the European context.

Another significant moderator of the distributed leadership-student outcomes relationship was the type of publication. The results showed that the path coefficients of articles were significantly higher than those of dissertations, which might indicate a publication bias. This might imply that studies that did not find a significant relationship or found a negative relationship between these two variables were less likely to be published as compared to those that found a significant positive relationship (Card, 2012, p.257).

As for transformational leadership, the school level was found to moderate the relationship between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy. Accordingly, the results showed a significant difference between the results of studies from primary school and higher education context, indicating that transformational leadership was more closely related to teacher self-efficacy in higher education context as compared to primary school context. In the literature, it is often stated that instructional leadership served the needs of primary school better while transformational leadership contributed to the development of more complex organizations involving much variety of sources and practices (Hallinger, 2003). From this perspective, the higher influence of transformational leadership on teacher efficacy could have resulted from this aspect of transformational leadership, which has a stronger potential to cater for the higher needs of the followers. As for the distributed leadership, data we could access for the analysis did not provide any results for the higher education context, and thus this moderator analysis could not be performed for distributed leadership-teacher efficacy relationship.

4.1. Limitations

The major limitation of the study was related to the limitations of the existing literature on the relationships between research variables. As the current study used data gathered from these existing studies, values for the relationship between some variables were more limited in number compared to the others. This imbalance between the number of studies on instructional, transformational and distributed leadership could have influenced our results. Therefore, the current study could be replicated as studies investigating the relationships between principal leadership behavior, teacher efficacy and student outcomes grow in number in the literature. This would also allow the comparison of results to shed better light on their complex relationship.

5. Conclusion

The results of the current study suggest significant implications for research and practice. First and foremost, our results lend additional support to ‘Leadership for Learning’ theory by revealing strong direct effect of instructional, transformational, and distributed leadership behaviors on student outcomes, which indicates a close relationship of these principal behaviors with students’ learning. These behaviors were also found to be significant in facilitating teachers’ self-efficacy. These results call for further studies on the role of principal leadership behavior in both teacher psychological states and attitudes, and student outcomes to build a more comprehensive understanding particularly into the integrated investigation of principal leadership behaviors. In addition, our finding suggests that improvement in student outcomes and school effectiveness is likely to be higher with an integrated practice of leadership rather than focusing on a single leadership model. This also provides significant support for the opinion that principal leadership behavior is multifaceted and attempts to define the best model of leadership that can elevate school effectiveness appears to be pointless.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., T.T. SK; methodology, T.K. and SK.; software, T.K. and S.K..; validation, T.K., T.T., S.P., S.K. A.K.; formal analysis, T.K. and S.K.; investigation, S.P., T.K., T.T., S.K. M.Ö., A.K.; resources, T.K., T.T., M.Ö., S.K., A.K.; data curation, T.K., T.T., M.Ö., A.K writing—original draft preparation, T.K., T.T., M.Ö., A. K.; writing—review and editing, T.K., T.T., M.Ö., A. K. and S.P.; visualization, T.K., S.K.; supervision, T.K. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used are publicly available; no identifying information was collected or included. All the data used in this research were accessed through the WoS/Scopus database(s), and other sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Funnel Plots for Each Pairwise Meta-Analysis

References

- Ahn, J., Bowers, A.J., & Welton, A.D. (2021). Leadership for learning as an organization-wide practice: evidence on its multilevel structure and implications for educational leadership practice and research. International Journal of Leadership in Education. [CrossRef]

- Akgöz, E. E. (2024). Mixed method examination of the relationship between the academic achievement of secondary school students and the instructional leadership behaviors of the school principal, teacher autonomy and teacher self-efficacy. Doctoral Dissertation, Gazi University, Ankara, Türkiye.

- Alanoglu, M. (2022). The role of instructional leadership in increasing teacher self-efficacy: a meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(2), 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2016). Teachers’ Views of Their School Climate and Its Relationship with Teacher Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction. Learning Environments Research, 19, 291-307. [CrossRef]

- Amels, J., Krüger, M. L., Suhre, C. J., & van Veen, K. (2021). The relationship between primary school leaders’ utilization of distributed leadership and teachers’ capacity to change. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(5), 732-749. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. (2017). Transformational leadership in education: A review of existing literature. International Social Science Review, 93(1), 1-13. http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol93/iss1/4.

- Bahamondes-Rosado, M. E., Cerdá-Suárez, L. M., Dodero Ortiz de Zevallos, G. F., & Espinosa-Cristia, J. F. (2023). Technostress at work during the COVID-19 lockdown phase (2020–2021): a systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1173425. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman.

- Barni, D., Danioni, F., & Benevene, P. (2019). Teachers’ self-efficacy: The role of personal values and motivations for teaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 465388. [CrossRef]

- Bates, W. L. (2023). Relationship Between Teacher Self Efficacy and Teacher Behaviors and Academic Achievement (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University).

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S., & Liu, Y. (2021). Does school leadership matter for teachers’ classroom practice? The influence of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on instructional quality. School effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(3), 387-412. [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., & Liu, Y. (2017). Multilevel analysis of the relationship between principals' perceived practices of instructional leadership and teachers' self-efficacy perceptions. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(1), 49-69. [CrossRef]

- Bennett N, Wise C, Woods PA and Harvey JA, (2003) Distributed leadership: a review of literature. Nottingham: NCSL.

- Berkovich, I. (2018). Will it sink or will it float: Putting three common conceptions about principals’ transformational leadership to the test. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46(6), 888-907. [CrossRef]

- Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088–1101. [CrossRef]

- Bossert, S. T. (1988). Chapter 6: Cooperative activities in the classroom. Review of Research in Education, 15(1), 225-250. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J., & Bowers, A. J. (2018). Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(2). [CrossRef]

- Braun, D., Billups, F. D., Gable, R. K., LaCroix, K., & Mullen, B. (2021). Improving equitable student outcomes: A Transformational and collaborative leadership development approach. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 5(1). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1308514.

- Burić, I., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Job satisfaction predicts teacher self-efficacy and the association is invariant: Examinations using TALIS 2018 data and longitudinal Croatian data. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103406. [CrossRef]

- Burušić, J., Babarović, T., & Velić, M. Š. (2016). School effectiveness: An overview of conceptual, methodological and empirical foundations. In Alfirević, N., Burušić, J., Pavičić, J., & Relja, R. (Eds.) School effectiveness and educational management: Towards a south-eastern Europe research and public policy agenda (pp. 5-26). Palgrave.

- Bush, T., Abdul Hamid, S., Ng, A., & Kaparou, M. (2018). School leadership theories and the Malaysia education blueprint: Findings from a systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(7), 1245-1265. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Liu, P., Tang, R., & Bo, Y. (2023). Distributed leadership and teacher work engagement: The mediating role of teacher efficacy and the moderating role of interpersonal trust. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(3), 383-397. [CrossRef]

- Calik, T., Sezgin, F., Kavgaci, H., & Cagatay Kilinc, A. (2012). Examination of relationships between instructional leadership of school principals and self-efficacy of teachers and collective teacher efficacy. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(4), 2498-2504. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1002859.

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers' self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students' academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473-490. [CrossRef]

- Card, N. A. (2012). Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research. Guilford Press. https://www.routledge.com/Applied-Meta-Analysis-for-Social-Science-Research/Card/p/book/9781462525003.

- Chang, M. L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: Appraisal, regulation and coping. Motivation and Emotion, 37, 799-817. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. W.-L. (2015a). Meta-analysis: a structural equation modeling approach. John Wiley&Sons.

- Cheung, M. W.-L. (2015b). MetaSEM: An R package for meta-analysis using structural equation modeling. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. W. L., & Hong, R. Y. (2017). Applications of meta-analytic structural equation modelling in health psychology: Examples, issues, and recommendations. Health Psychology Review, 11(3), 265-279. [CrossRef]

- Chin, J. M. C. (2007). Meta-analysis of transformational school leadership effects on school outcomes in Taiwan and the USA. Asia Pacific Education Review, 8(2), 166-177. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. (2017). Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach. SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Copland, M. (2003). Leadership of inquiry: building & sustaining capacity for school improvement. Educational Evaluation & Policy Analysis, 25(4), 375-395. http://doi.org/10.3102/01623737025004375.

- Dale, A., Phillips, R., & Sianjina, R. R. (2011, April). Influences of instructional leadership, transformational leadership and the mediating effects of self-efficacy on student achievement. In The 6th international conference of the American institute of higher education (Vol. 4, pp. 91-100).

- Daniëls E, Hondeghem A and Dochy F (2019) A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educational Research Review 27, 110-125. [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97-140. [CrossRef]

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: how successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221-258. [CrossRef]

- Djigić, G., Stojiljković, S., & Dosković, M. (2014). Basic personality dimensions and teachers’ self-efficacy. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 593-602. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, V., & Sahney, S. (2022). Relation of principal instructional leadership, school climate, teacher job performance and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(2), 148-166. [CrossRef]

- Duyar, I., Gumus, S., & Bellibas, M.S. (2013). Multilevel analysis of teacher work attitudes: The influence of principal leadership and teacher collaboration. International Journal of Educational Management, 27(7), 700-719. [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, L., & Gurr, D. (2011). Theory and practice of successful school leadership in Australia. School Leadership & Management, 31(4), 355-368. [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis was detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 629–634. [CrossRef]

- Eliophotou Menon, M., & Lefteri, A. (2021). The link between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy. Education, 142(1), 42-52.

- Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionalist. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 715–729. [CrossRef]

- Fox, A. M. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy, content and pedagogical knowledge, and their relationship to student achievement in Algebra I. Dissertation, The College of William and Mary. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-ydcq-tw12.

- Fullan, M. (2001). Leading in a culture of change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. [CrossRef]

- Giliç, F., Kanadli, S., Gündüz, Y., & Yusuf, I. (2024). The mediating role of job satisfaction between leadership and organizational performance and the moderating effect of educational context. Educational Process: International Journal, 13(2), 52-71. [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Hoy, A. W. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 479-507. [CrossRef]

- Goddard, Y., and Kim, M. (2018). Examining connections between teacher perceptions of collaboration, differentiated instruction, and teacher efficacy. Teachers College Record 120, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Goldring, E., Porter, A., Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., & Cravens, X. (2009). Assessing learning-centered leadership: Connections to research, professional standards, and current practices. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(1), 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Gratacós, G., Mena, J., & Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2023). The complexity thinking approach: beginning teacher resilience and perceived self-efficacy as determining variables in the induction phase. European Journal of Teacher Education, 46(2), 331-348.

- Greenier, V., Derakhshan, A., and Fathi, J. (2021). Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: a case of British and Iranian English language teachers. System 97:102446. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J. (2004). Relation of principal transformational leadership to school staff job satisfaction, staff turnover, and school performance. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(3), 333-356. [CrossRef]

- Gulistan, M., Athar Hussain, M., & Mushtaq, M. (2017). Relationship between Mathematics Teachers' Self Efficacy and Students' Academic Achievement at Secondary Level. Bulletin of education and research, 39(3), 171-182. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1210137.

- Gurr, D., Drysdale, L., & Mulford, B. (2007). Instructional leadership in three Australian schools. International Studies in Educational Administration (Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration & Management (CCEAM)) 35(3), 20-29.

- Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly 13(4), 423-451. [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D. (2016). A model of successful school leadership from the international successful school principalship project. In Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & Pollock, K. (Eds.). How school leaders contribute to student success: The four paths framework (pp. 15-30). Springer.

- Hallinger, P. (2003) Leading Educational Change: reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3), 329-352. [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2), 125-142. [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2020). 'Are principals instructional leaders yet?'A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics, 122(3), 1629-1650. [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Hosseingholizadeh, R., Hashemi, N., & Kouhsari, M. (2018). Do beliefs make a difference? Exploring how principal self-efficacy and instructional leadership impact teacher efficacy and commitment in Iran. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(5), 800-819. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., and Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers' self-efficacy, work engagement, and reflection. Frontiers in Psycholpgy. 12:763234. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B., & Lárusdóttir, S. H. (2015). Instructional leadership in compulsory schools in Iceland and the role of school principals. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(5), 583–603. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z., & Yau, S. (2013). Transformational leadership practices and student satisfaction in an educational setting in Malaysia. International Journal of Accounting, and Business Management, 1(1), 102-111.

- Heck, R.H., & Hallinger, P. (2009). Distributed leadership in schools: Does system policy make a difference?. In: Harris A (ed) Distributed Leadership. Springer, pp. 101-120. [CrossRef]

- Heng, Q., & Chu, L. (2023). Self-efficacy, reflection, and resilience as predictors of work engagement among English teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1160681. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. [CrossRef]

- Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531-569. [CrossRef]

- Jack, S. (2015). Meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Springer. https://www.suzannejak.nl/MASEM_SJak.pdf.

- Jak, S., & Cheung, M. W.-L. (2020). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling with moderating effects on SEM parameters. Psychological Methods, 25(4), 430–455. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Meta-analysis in information systems research: Review and recommendations. International Journal of Information Management, 55. [CrossRef]

- Karadag, E. (2020). The effect of educational leadership on students’ achievement: A cross-cultural meta-analysis research on studies between 2008 and 2018. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21(1), 49-64. [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Kardas, A., Kanadlı, S., Tülübaş, T., & Yildirim, B. (2024a). How collective efficacy mediates the association between principal instructional leadership and teacher self-efficacy: findings from a meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM) study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 85. [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Leithwood, K., & Tülübaş, T. (2024b). The intellectual evolution of educational leadership research: a combined bibliometric and thematic analysis using SciMAT. Education Sciences, 14(4), 429. [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., & Tülübas, T. (2024). School leadership and management in the age of artificial intelligence (AI): recent developments and future prospects. Educational Process International Journal, 13(1), 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Katıtaş, S., Yıldız, S., & Doğan, S. (2022). The effect of shared leadership on job satisfaction: the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy. Educational Studies, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M., & Koçyigit, M. (2023). The relationship between transformational leadership and teacher self-efficacy in terms of national culture. Educational Process: International Journal, 12(1), 36-52. [CrossRef]

- Ker, H. W., Lee, Y. H., & Ho, S. M. (2022). The Impact of Work Environment and Teacher Attributes on Teacher Job Satisfaction. Educational Process: International Journal, 11(1), 28-39. [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59-76. [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, S. & Keams, D. (2013). Leadership practice in secondary schools inventory: facilitator’ guide. London. OUP.

- Kwan, P. (2020). Is transformational leadership theory passé? Revisiting the integrative effect of instructional leadership and transformational leadership on student outcomes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(2), 321-349. [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R., Watt, H. M., & Richardson, P. W. (2020). Teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy, perceived classroom management and teaching contexts from beginning until mid-career. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101346.Learn. Instr. 69:101346. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2012). Ontario Leadership Framework with a discussion of the leadership foundations. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Institute for Education Leadership, OISE.

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27-42. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management, 40(1), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201-227. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Seashore, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Review of research: How leadership influences student learning. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/2035/CAREIReviewofResearchHowLeadershipInfluences.pdf?sequence=1.

- Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly 48(3), 387-423. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Patten, S., & Jantzi, D. (2010). Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(5), 671-706. [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & McCullough, C. (2019). How school districts influence student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(5), 519-539. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Liu, Y. (2022). An integrated model of principal transformational leadership and teacher leadership that is related to teacher self-efficacy and student academic performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 42(4), 661-678. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. (2018). Transformational leadership research in China (2005–2015). Chinese Education & Society, 51(5), 372-409. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Bellibas, M.S. & Gümüş, S. (2021). The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 430-453. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. M., Chen, N. Q., Xu, L., Chen, Y. X., and Wu, J. (2016). A survey of contemporary college students’ emotional intelligence in China. Journal of Psychology Science 39, 1302–1309. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Hallinger, P. (2018). Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-efficacy, and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(4), 501-528. [CrossRef]

- Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 370-397. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S., Waniganayake, M., & Gibson, I. W. (2014). Scaffolding leadership for learning in school education: Insights from a factor analysis of research conducted in Australian independent schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(4), 474-490. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336-341. [CrossRef]

- Mwove, P. N., Mwania, J. M., & Kasivu, G. M. (2023). The extent to which principals’ use of transactional leadership style influences students’ academic performance in public secondary schools in Kenya. International Journal of Management Studies and Social Science Research, 5(3), 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ: Systematic Reviews, 10, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, S., Gözüm, A.İ.C., Kaya, Ü.Ü., Kalogiannakis, M., Karaköse, T. (2024). Examining the validity and reliability of the teacher self-efficacy scale in the use of ICT at home for preschool distance education (TSES-ICT-PDE) among Greek preschool teachers: a comparative study with Turkey. In: Papadakis, S. (eds) IoT, AI, and ICT for Educational Applications. EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Perera, H. N., & John, J. E. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching math: Relations with teacher and student outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101842. [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, M., Aydin, B., & Gümüş, S. (2023). Putting the instructional leadership–student achievement relation in context: a meta-analytical big data study across cultures and time. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, . [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, M. & Tulowitzki, P. (2017). Disentangling school leadership and its ties to instructional practices–an empirical comparison of various leadership styles. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(4), 629-649. [CrossRef]

- Printy, S., & Liu, Y. (2021). Distributed leadership globally: The interactive nature of principal and teacher leadership in 32 countries. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(2), 290-325. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (4.1.2) [Computer software]. https://www.R-project.

- Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 700–712. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. C. (2022). Exploring emotions in language teaching. RELC Journal, 53(1), 225-239. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635-674. [CrossRef]

- Ross, J. A., & Gray, P. (2006). Transformational leadership and teacher commitment to organizational values: The mediating effects of collective teacher efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 179-199. [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Shatzer, R. H., Caldarella, P., Hallam, P. R., & Brown, B. L. (2014). Comparing the effects of instructional and transformational leadership on student achievement: Implications for practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(4), 445-459. [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N. S., Keng, S.-L., & Cheung, M. W.-L. (2021). Emotional intelligence mediates the connection between mindfulness and gratitude: a meta-analytic structural equation modeling study. Mindfulness, 12(11), 2613–2623. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, G. (2024). meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis (7.0-0) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/index.html.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611-627. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports 114, 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Motivated for teaching? Associations with school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education 67, 152–160. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2019). Teacher self-efficacy and collective teacher efficacy: relations with perceived job resources and job demands, feeling of belonging, and teacher engagement. Creative Education, 10(7), 1400-1424. [CrossRef]

- Smuati, S.& Niemted, W. (2020). The impact of instructional leadership on Indonesian elementary teacher efficacy. Ilkogretim Online, 19(4), 2335-2346. [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3-34. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., & Leithwood, K. (2012). Transformational school leadership effects on student achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 11(4), 418-451. [CrossRef]

- Sun, A., & Xia, J. (2018). Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. International Journal of Educational Research, . [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Y., Gao, L., & Shi, M. (2020). Second-order meta-analysis: Synthesising the evidence on associations between school leadership and different school outcomes. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership. 86-97. [CrossRef]

- Tella, A. (2008). Teacher variables as predictors of academic achievement of primary school pupils mathematics. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 1(1), 16-33.